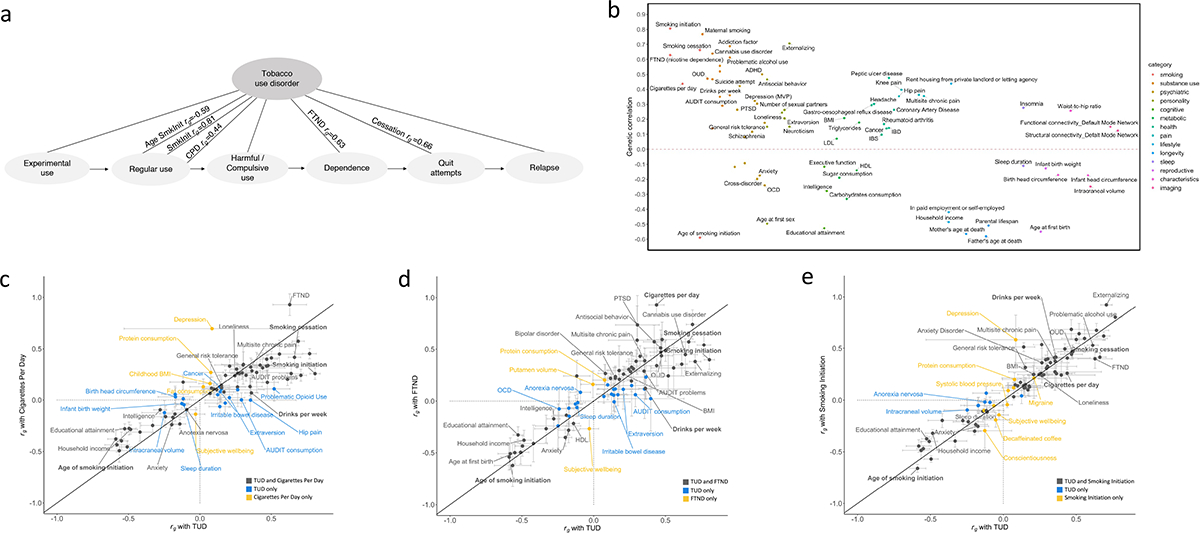

Figure 5. FDR-significant genetic correlations between TUD-EUR and 113 complex traits, including smoking and related phenotypes (b).

(a) TUD consists of multiple components, progressing from experimental use to regular use, compulsive use, cessation, and relapse. Therefore, high genetic correlations (rg) are to be expected between the age of smoking initiation (AgeSmkInit), smoking initiation (SmkInit), cigarettes per day (CPD), smoking cessation (SmkCess)13, nicotine dependence measured using the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND)27, and tobacco use disorder (see Supplementary Table 31 for full results). (b) Genetic correlations with an extended list of traits from publicly available GWAS. Traits with positive rg values are plotted above the line; traits with negative rg values below the line. All rgs are significant using a 5% FDR correction for multiple testing. (c-e) Systematic comparison of significant genetic correlation estimates between TUD and SmkInit (c), CPD (d) and FTND (e) reveal overlapping (black dots) and trait-specific (blue and yellow dots) relations between TUD and these other smoking phenotypes. rg estimates were generally higher for TUD than CPD - even with a smaller sample size (TUD, N=495,005; CPD, N=784,353) - and FTND. On the contrary, rg’s were generally smaller for TUD than SmkInit, possibly because of the larger sample for SmkInit (N=3,383,199) than TUD. Overall, these results indicate that these smoking behaviors, including SmkInit, CPD, FTND, and TUD, represent both unique and interrelated polygenic influences, which are complementary to those associated with other complex behaviors and disorders at the genetic level.