Abstract

This study examined whether distress in relation to attenuated psychotic symptoms (DAPS) is associated with clinical outcomes in an ultra-high risk (UHR) for psychosis sample. We also investigated whether DAPS is associated with cognitive style (attributional style and cognitive biases) and whether amount of psychosocial treatment provided is associated with reduction in DAPS. The study was a secondary analysis of the “Neurapro” clinical trial of omega-3 fatty acids. Three hundred and four UHR patients were recruited across 10 early intervention services. Data from baseline assessment, regular assessments over 12 months, and medium term follow-up (mean = 3.4 years) were used for analysis. Findings indicated: a positive association between DAPS assessed over time and transition to psychosis; a significant positive association between baseline and longitudinal DAPS and transdiagnostic clinical and functional outcomes; a significant positive association between baseline and longitudinal DAPS and nonremission of UHR status. There was no relationship between severity of DAPS and cognitive style. A greater amount of psychosocial treatment (cognitive-behavioral case management) was associated with an increase in DAPS scores. The study indicates that UHR patients who are more distressed by their attenuated psychotic symptoms are more likely to have a poorer clinical trajectory transdiagnostically. Assessment of DAPS may therefore function as a useful marker of risk for a range of poor outcomes. The findings underline the value of repeated assessment of variables and incorporation of dynamic change into predictive modeling. More research is required into mechanisms driving distress associated with symptoms and the possible bidirectional relationship between symptom severity and associated distress.

Keywords: ultra-high risk, subjective distress, attenuated psychotic symptoms, transdiagnostic, cognitive biases

Introduction

Approximately one-third of individuals who meet ultra-high risk (UHR) for psychosis criteria, based on a combination of trait and state risk factors,1 progress to psychotic disorder within 1–3 years following initial clinical presentation.2–4 A substantial body of work has attempted to identify predictive variables and to generate prediction models in this clinical population to enhance risk stratification.5 Psychosis risk stratification would facilitate etiological and preventive treatment research. In addition to the onset of psychotic disorder (transition), nonremission of UHR status, nonpsychotic clinical outcomes, and functional outcomes have also emerged as important outcomes of interest and treatment targets.6–11

The role of subjective distress in relation to attenuated psychotic symptoms (DAPS) has been a comparatively neglected area of focus in this predictive modeling. This issue is particularly relevant given that the great majority (80%–90%) of UHR patients meet the UHR criteria on the basis of attenuated psychotic symptoms.4,12 Rapado-Castro et al13 reported that the sources of clinical distress are varied in this clinical population, with clinicians reporting the main sources of clinical distress for their patients were social and functioning difficulties, depressive symptoms, and attenuated psychotic symptoms. Approximately 60% of this sample of 73 UHR patients reported their attenuated psychotic symptoms to be distressing. Intensity of distress associated with attenuated psychotic symptoms, as well as distress associated with anxiety symptoms and substance use, predicted transition to psychosis. A possible reason for increased distress associated with attenuated psychotic symptoms may be an individual’s beliefs, appraisals, or reactions to their unusual experiences (cognitive style), which may also impact on transition risk.14–17 Consistent with this, Stowkowy et al18 reported that UHR patients who later transitioned to psychosis reported less control over their unusual experiences at study entry (eg, more likely to agree with statements such as “My experiences frighten me,” “I find it difficult to cope”). However, a contrasting finding was reported by Power et al,19 who reported no association between higher levels of distress associated with attenuated psychotic symptoms in a UHR sample (self-rated rather than clinician-rated, n = 70) and transition to psychosis.

Reasons for help-seeking among UHR patients might be taken as a proxy for sources of clinical distress in this clinical population. Falkenberg et al20 reported that affective symptoms (depression and/or anxiety) were the most commonly reported reasons for help-seeking (47% of participants), followed by attenuated psychotic symptoms (39.8%), with no association between subjective complaints at presentation and transition to psychosis. Similar rates of reason for referral to a UHR service were reported by Rice et al.21 However, in contrast, they reported a positive association between being referred exclusively due to attenuated psychotic symptoms and subsequent transition to psychosis.

The issue of subjective distress has also received some attention in general population samples. Several studies have indicated that specific subtypes of psychotic experiences may be more associated with distress than others. Yung et al22 reported that “bizarre experiences,” “persecutory ideas,” and “perceptual abnormalities” were associated with distress, depression, and poor functioning, whereas “magical thinking” was not. Armando et al23 reported an association between “bizarre experiences” and “persecutory ideas” and distress, depression, and poor functioning; a weaker relationship was found between “perceptual abnormalities” and “grandiosity” and the same variables. Recently, Legge et al24 reported a genetic analysis of risk for psychotic experiences in a general population sample from the UK Biobank. They found that the presence of distress associated with psychotic experiences strengthened genetic associations not only with schizophrenia but with a range of psychiatric disorders, including bipolar disorder, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, major depressive disorder, and autism spectrum disorder. This suggests that some of the genetic contribution identified by the authors may not be associated with the psychotic experiences per se but rather with susceptibility to distress or dysfunction caused by these and other psychiatric symptoms.25

The current study builds on this previous work by examining the clinical relevance of subjective DAPS in a large UHR sample. Our main research question was:

1. Is DAPS associated with clinical outcomes (ie, transition to psychosis, nonremission of UHR status, symptom severity, and psychosocial functioning)?

In addition, we were interested in whether:

2. DAPS is associated with cognitive style, specifically attributional style and cognitive biases;

3. there is an association between amount of psychosocial treatment provided and reduction in DAPS.

Question 1 was approached in both a static and dynamic (ie, time-varying) manner. That is, the association was examined in terms of baseline DAPS (study entry) as well as the longitudinal measurements of DAPS. Question 2 was examined using baseline data only because attributional style and cognitive biases were only assessed at baseline in this cohort. Question 3 was approached longitudinally (change over time).

Given the limited previous research related to DAPS, particularly in UHR samples, and the mixed findings to date, the analysis was approached as hypothesis generating rather than hypothesis testing.

Method

Participants

Three hundred and four help-seeking individuals were recruited from ten international treatment centers across Australia (Melbourne, Sydney), Austria (Vienna), Denmark (Copenhagen), Germany (Jena), Hong Kong (Pokfulam), Singapore, Switzerland (Basel, Zurich), and The Netherlands (Amsterdam). Participants met UHR criteria and were aged between 13 and 39 years (mean age = 19.12, SD = 4.55), with approximately equal numbers of males and females (165 [54%] females). Written informed consent was obtained from participants, with parental or guardian consent for minors.

The study was a secondary analysis of the Neurapro trial of omega-3 fatty acids in UHR patients (see26–28 for full details). In this trial, no significant differences in demographic characteristics, clinical or functional outcomes were observed between the experimental and control groups at baseline, 12-month follow-up,27 or at medium term follow-up (mean = 3.4 years).28 Therefore, treatment groups were combined for joint analysis in this secondary analysis, as previously conducted with this dataset.9,29–31 All participants received comprehensive psychosocial intervention (cognitive-behavioral case management [CBCM]), 20% used antidepressants and 10% used antipsychotic medication over the follow-up period. Omega-3 fatty acid supplementation or placebo was provided for up to 6 months.

Measures

DAPS

The Comprehensive Assessment of At-Risk Mental States (CAARMS32) was used to assess DAPS. This was measured using a continuous scale from 0 (not at all distressed) to 100 (extremely distressed). Two summary DAPS scores were calculated using the distress scores on the 4 attenuated positive psychotic symptom (APS) items measured by the CAARMS (Unusual Thought Content [UTC], Non-Bizarre Ideas [NBI], Perceptual Abnormalities [PA], and Disorganised Speech [DS]): the mean distress score of the 4 APS items and the maximum distress score of the 4 APS items. DAPS was assessed at baseline, monthly from baseline to months 6, 9, 12, and at medium term follow-up.

Transition to Psychosis

Measured using the CAARMS, as per previous research.27 If the participant was lost to follow-up, state medical records were consulted to determine if the person had been diagnosed with a psychotic disorder by a mental health service.

Nonremission of UHR Status

All cases who did not meet transition criteria or UHR remission criteria33 were categorized as nonremitted cases. UHR remission criteria consist of:

For each of the 3 positive symptoms UTC, NBI, and PA, either the severity or the frequency score needs to be <3 and

for the positive symptom DS, the severity score needs to be <4 or the frequency score needs to be <3 and

there is an improvement of at least 5 points in Social and Occupational Functioning Scale (SOFAS) compared with baseline or the SOFAS score is at least 70.

General Psychopathology

The total score on the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS34).

Depression.

Measured using the Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS35).

Negative Symptoms.

Measured using the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS36).

Manic Symptoms.

Measured using the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS37).

Anxiety Symptoms.

Measured using the BPRS Anxiety scale.

Psychopathology measures were administered at baseline, monthly from baseline to months 6, 9, 12, and at medium term follow-up.

Functional Outcomes.

Functional outcomes were measured using the SOFAS,38 the Global Functioning (social and role) scales,39 and the Assessment of Quality of Life (AQoL)-8D40 scale. Frequency of assessment: SOFAS—baseline, months 3, 6, 9, 12, and medium term follow-up; Global Functioning—baseline, months 3–6, 12, and medium term follow-up; AQoL-8D—baseline, months 6, 12, and medium term follow-up.

Attributional Style and Cognitive Biases.

This was measured using the Internal, Personal and Situational Attributions Questionnaire (IPSAQ41) at baseline. The IPSAQ provides 3 attributional style scores (internal, personal, and situational attributions) in response to positive and negative situations. These 6 subscale scores can be used to derive 2 overall cognitive bias scores: externalizing bias (a self-serving bias of blaming oneself less for negative events than for positive events) and personalizing bias (a tendency to make personal rather than situational external attributions for negative events).

Amount of Psychosocial Treatment.

This was operationalized as the total number of CBCM sessions provided to the participant during the trial.

All measures were administered via research interview, apart from the number of CBCM sessions provided, which was extracted from research files. All recruitment sites used the same assessment battery. The instruments that were not already available in the local language went through a rigorous process of translation and back-translation.26

Statistical analyses

Research Question 1.

DAPS and transition risk: Cox regression was used to analyze the association between baseline DAPS and transition risk. Joint modeling42,43 was used to analyze the association between longitudinal DAPS (ie, DAPS over time) and transition risk.

DAPS and symptomatology and functioning: General linear modeling was used to investigate the association between baseline DAPS and outcomes at months 6 and 12. Linear mixed-effects modeling was used to analyze the association between longitudinal DAPS values and longitudinal symptom and functional outcomes. Each outcome (symptoms and functioning) was treated as the dependent variable, DAPS as a fixed effect and time as both a fixed effect and a random effect.

DAPS and nonremission: Logistic regression was used to analyze the association between baseline DAPS and nonremission of UHR status at follow-up time points. The association between longitudinal DAPS and longitudinal UHR status was investigated using generalized linear mixed-effects modeling (GLMM) with DAPS as a fixed effect and time as both a fixed effect and a random effect.

Research Questions 2 (DAPS and Cognitive Style) and 3 (Reduction in DAPS and Amount of Psychosocial Treatment).

Pearson correlation was used for these 2 sets of analyses.

Results

Research Question 1

The Relationship Between DAPS and Transition to Psychosis.

The baseline (Cox regression) and longitudinal (joint modeling) relationship between DAPS and transition to psychosis is summarized in table 1. A significant association was found between DAPS and transition risk when the longitudinal distress values were considered but not when the baseline values alone were used. The hazard ratio corresponds to the ratio of transition risk (in terms of hazard rate) associated with a 1-point increase in distress score (0–100). The hazard ratios for the longitudinal values suggest that, at a particular time point, higher distress was associated with higher transition risk at that time point.

Table 1.

Association Between DAPS and Risk of Transition to Psychosis

| P-Value | Hazard Ratio (HR) | 95% CI for HR | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Limit | Upper Limit | ||||

| Mean distress | Baseline | .875 | 1.00 | 0.98 | 1.01 |

| Longitudinal | .001 | 1.04 | 1.02 | 1.07 | |

| Maximum distress | Baseline | .472 | 1.00 | 0.98 | 1.01 |

| Longitudinal | .003 | 1.03 | 1.01 | 1.04 |

Note: CI, confidence intervals; DAPS, distress in relation to attenuated psychotic symptoms; Mean distress, mean distress score of the 4 CAARMS positive attenuated psychotic symptoms; Maximum distress, maximum distress score of the 4 CAARMS positive attenuated psychotic symptoms; Hazard ratio, the ratio of transition risk (in terms of hazard rate) associated with a 1-point increase in distress score (0–100).

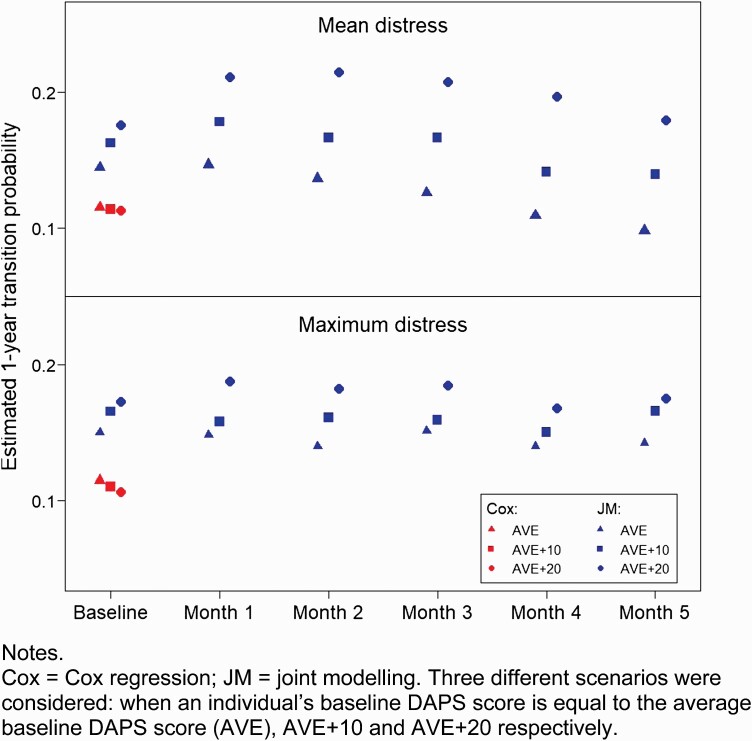

Figure 1 shows the estimated probabilities of transition at the 1-year follow-up point. The 3 red plotting symbols correspond to transition probabilities estimated by using the Cox regression models which utilized baseline DAPS scores alone. Three different scenarios were considered: when an individual’s baseline DAPS score is equal to the average baseline DAPS score (AVE), AVE + 10, and AVE + 20, respectively. These 3 values were input into the Cox model to compute the corresponding estimated transition probabilities, which are displayed in figure 1. It can be seen that, for both mean distress and maximum distress, there is little difference between the estimated transition probabilities in the 3 scenarios. This means that, even when there are substantial differences in distress score (differences of 10–20 points), the resulting transition risk is about the same, consistent with the Cox regression results (table 1) showing no significant association between baseline DAPS and transition risk. The longitudinal analysis (joint modeling) shows a different picture. The same 3 scenarios of baseline DAPS scores were considered, and in addition the DAPS trajectory was taken to follow the average slope (as obtained in the joint model concerned) in the estimation of transition probability for the different follow-up time points. For illustration, only baseline and months 1–5 are shown. Figure 1 shows that the transition probabilities from joint modeling exhibit much larger differences between the 3 scenarios, reflecting the result that there was a significant association between DAPS and transition when longitudinal data were used (table 1).

Fig. 1.

Association between mean/maximum DAPS score and 1-year transition risk using baseline and longitudinal values. Note: Cox, Cox regression; JM, joint modeling. Three different scenarios were considered: when an individual’s baseline DAPS score is equal to the average baseline DAPS score (AVE), AVE + 10 and AVE + 20, respectively.

The Relationship Between DAPS and Clinical and Functional Outcomes.

The results of this analysis are shown in table 2 (mean DAPS) and Supplementary table 1 (maximum DAPS). The results indicate that there was significant association between DAPS and each of the outcomes. Specifically, higher baseline DAPS was associated with worse outcome scores at months 6 and 12. Also, the results for the longitudinal analysis suggest that, at a particular time point, higher distress was associated with worse outcome scores.

Table 2.

Association Between Mean DAPS and Clinical and Functional Outcomes

| Baseline DAPS and Month 6 Outcomes | Baseline DAPS and Month 12 Outcomes | Longitudinal DAPS and Longitudinal Outcomes | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | SE | P-Value | n | Coefficient | SE | P-Value | n | Coefficient | SE | P-Value | n | |

| SOFAS | −0.340 | 0.052 | <.001 | 238 | −0.417 | 0.070 | <.001 | 207 | −0.293 | 0.017 | <.001 | 297 |

| GF Social | −0.030 | 0.004 | <.001 | 238 | −0.035 | 0.006 | <.001 | 209 | −0.017 | 0.001 | <.001 | 295 |

| GF Role | −0.022 | 0.006 | <.001 | 237 | −0.033 | 0.007 | <.001 | 209 | −0.018 | 0.002 | <.001 | 295 |

| AQOL | −0.488 | 0.052 | <.001 | 205 | −0.509 | 0.063 | <.001 | 183 | −0.262 | 0.018 | <.001 | 280 |

| BPRS | 0.313 | 0.024 | <.001 | 236 | 0.305 | 0.025 | <.001 | 205 | 0.220 | 0.007 | <.001 | 296 |

| SANS | 0.274 | 0.040 | <.001 | 237 | 0.316 | 0.048 | <.001 | 205 | 0.177 | 0.010 | <.001 | 296 |

| MADRS | 0.280 | 0.028 | <.001 | 238 | 0.335 | 0.034 | <.001 | 210 | 0.199 | 0.008 | <.001 | 304 |

| YMRS | 0.067 | 0.009 | <.001 | 237 | 0.064 | 0.009 | <.001 | 204 | 0.029 | 0.003 | <.001 | 295 |

| BPRS Anxiety | 0.047 | 0.005 | <.001 | 237 | 0.052 | 0.006 | <.001 | 209 | 0.024 | 0.001 | <.001 | 296 |

Note: Coefficient, coefficient of distress in the model concerned, indicating the average amount of change in the outcome for a unit change in the DAPS score. Its sign indicates the direction of the association between DAPS and outcome; DAPS, distress in relation to attenuated psychotic symptoms; SOFAS, Social and Occupational Functioning Score; GF Social, Global Functioning Social Scale; GF Role, Global Functioning Role Scale; AQOL, Assessment of Quality of Life-8D Scale; BPRS, Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale; SANS, Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms; MADRS, Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale; YMRS, Young Mania Rating Scale; BPRS Anxiety, Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale—Anxiety Scale.

The Relationship Between DAPS and Nonremission of UHR Status.

Supplementary table 2 shows the percentage of cases with UHR status at various follow-up time points. Table 3 shows the relationship between baseline DAPS and UHR status at months 6 and 12 and also the GLMM analysis of the association between the longitudinal DAPS scores and longitudinal values of UHR status. A significant association was found between baseline maximum DAPS score and month 12 UHR status. However, the association was far stronger in the longitudinal analysis, which found that, at a particular time point, higher DAPS score was significantly associated with higher likelihood of being UHR positive.

Table 3.

Association Between DAPS Score and UHR Status at Baseline and Longitudinally

| Baseline Distress and Month 6 UHR Status | Baseline Distress and Month 12 UHR Status | Longitudinal Distress and Longitudinal UHR Status | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P-Value | OR | 95% CI of the OR Lower Limit | 95% CI of the OR Upper Limit | n | P-Value | OR | 95% CI of the OR Lower Limit | 95% CI of the OR Upper Limit | n | P-Value | OR | 95% CI of the OR Lower Limit | 95% CI of the OR Upper Limit | n | |

| Mean distress | .157 | 1.01 | 1.00 | 1.02 | 234 | .058 | 1.01 | 1.00 | 1.03 | 205 | <.001 | 1.19 | 1.16 | 1.22 | 303 |

| Max distress | .172 | 1.01 | 1.00 | 1.02 | 234 | .029 | 1.01 | 1.00 | 1.03 | 205 | <.001 | 1.07 | 1.06 | 1.08 | 303 |

Note: CI, confidence intervals; UHR status, whether the participant still fulfills UHR criteria; OR, odds ratio. The odds ratios correspond to a unit difference in DAPS score (0–100).

Research Question 2: The Relationship Between DAPS and Cognitive Style (Attributional Style and Cognitive Biases)

The results of this analysis are presented in Supplementary table 3. There were low (nonsignificant) correlations between DAPS and attributional style and cognitive biases, as measured using the IPSAQ.

Research Question 3: The Relationship Between DAPS and Amount of Psychosocial Treatment Provided

Table 4 shows a small positive correlation between number of CBCM sessions provided and change in DAPS level. As change was computed as month 12 minus baseline, a positive change corresponds to an increase in DAPS level by month 12. The small positive correlations indicate that a higher number of CBCM sessions was mildly associated with a larger increase in DAPS score.

Table 4.

Partial Correlation Between Number of CBCM Sessions by Month 12 and Change in DAPS Score From Baseline to Month 12 After Adjusting for Baseline DAPS Score

| Change (m12 Minus Baseline) | Partial Correlation | P-Value | n |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean distress | 0.24 | <.001 | 206 |

| Max distress | 0.18 | .009 | 206 |

Discussion

In this report we examined the clinical significance of distress associated with attenuated psychotic symptoms (DAPS) in UHR patients. In summary, the findings indicate: a positive association between DAPS assessed over time and transition to psychosis (longitudinal analysis); a significant association between baseline and longitudinal DAPS and clinical and functional outcomes; a significant association between baseline and longitudinal DAPS (particularly the latter) and nonremission of UHR status. In addition, the findings indicate no relationship between severity of DAPS and cognitive style (attributional style and cognitive biases) and an association between a higher number of CBCM sessions provided and a larger increase in DAPS scores over 12 months.

These findings have a number of important implications. Distress associated with attenuated psychotic symptoms, when measured over time, may be a useful marker of risk for transitioning to psychotic disorder in this clinical population. Coupled with the association between DAPS severity and nonremission of UHR status, this suggests that DAPS over time may function as a signal that preventative treatment may need to be intensified. The issue of causality cannot be determined from the current data: while it may be that higher levels of DAPS may contribute to increased symptomology over time, it is also possible that persistent or increasing symptomatology may impact on associated subjective distress, or that they are both expressions of a third factor. Regardless of this issue, it is clear from the findings that DAPS is not psychosis specific in its relevance—it was associated with a broad range of transdiagnostic symptomatology and compromised functioning both at baseline and longitudinally. This suggests that DAPS may possibly indicate severity of a “general psychopathology” (P) dimension44,45 and risk for stage progression across transdiagnostic clinical stages.46–48

The fact that the association between DAPS and transition risk was apparent in longitudinal assessments but not at baseline and that the association with nonremission of UHR status was much stronger longitudinally than at baseline assessment underlines the value of repeating assessments over time and examining dynamic associations between variables of interest in psychopathology research.43,49–51 It shows the importance of persistence or increase in distress as a relevant clinical marker. It also highlights the inherent limitations of risk calculators based purely on information available at clinic/study entry52–54—such an approach will miss the risk associated with the longitudinal evolution of psychopathology and related contextual factors.

The mechanisms associated with DAPS are not clear at this stage and warrant further investigation. Apart from possible biological or neurocognitive factors, which were not the focus here, the psychological processes of appraisals or attributional processes do not seem to play a role based on the current data. However, we note that the measure used in the current study, the IPSAQ, is directed toward assessing attributions, beliefs, or reactions to situations (eg, “a friend thinks you are stupid”) rather than to anomalous subjective experiences, such as perceptual disturbances, delusional mood, disorganized thinking, and so on. Future investigations should use a measure that directly measures such appraisals, such as the Appraisals of Anomalous Experiences Interview (AANEX),55 in order to unpick the psychological mechanisms that may be at play. Such work could interrogate the directionality of the relationship between DAPS and psychological attribution/beliefs—this relationship may in fact be bidirectional rather than unidirectional. For example, appraising an anomalous experience to be dangerous or a sign of impending madness might certainly increase distress associated with the symptom. However, the nature of the symptom itself (and associated distress) might also have an impact on appraisals or beliefs about attenuated psychotic symptoms. For example, a sudden onset, unpredictable perceptual abnormality may inherently be more distressing than a perceptual abnormality for which the person can reliably predict the context and triggers; the former scenario may lead the person to view their symptoms as uncontrollable whereas the latter may prompt a greater sense of control and manageability (ie, the phenomenology of the symptom impacting appraisals/beliefs).

The positive association between a greater number of CBCM sessions and a larger increase in DAPS score over 12 months was most likely due to more CBCM sessions being required and provided to patients who were more distressed by their attenuated psychotic symptoms (an “indication bias” 56). This is consistent with our previous analysis of this dataset that found, somewhat counterintuitively, that a higher number of CBCM sessions, more assessment of symptoms, and greater therapeutic focus on attenuated psychotic symptoms predicted an overall increase in attenuated psychotic symptoms.29 However, it cannot be entirely discounted that cognitive-behavior therapy that focuses on and explores attenuated psychotic symptoms may increase associated distress,57,58 at least over a 12-month time frame, a possibility that requires further direct examination.

Several strengths and limitations should be noted. This is the largest sample to date to examine the issue of the clinical relevance of DAPS in UHR patients, with a substantial (mean = 3.4 years) follow-up period. Therefore, the findings can be considered to be more robust than previous reports on this issue. A limitation is the danger of tautological logic and the possibility that the measurement of variables lack criterion validity. That is, being more distressed by psychotic symptoms may be considered to be part of the definition of reaching threshold for determination of psychosis transition. An examination of the CAARMS instrument, used to determine transition in the current sample, indicates that this is the case for the PA scale of the CAARMS but not for the other APS scales (ie, the description of higher severity ratings of perceptual abnormalities includes “being more distressed” by the experience). This consideration may apply to the analysis of transition risk, but not to the other analyses reported.

Conclusion

The current study indicates that UHR patients who are more distressed by their attenuated psychotic symptoms, at study entry and over time, are more likely to have a poorer clinical trajectory transdiagnostically. Assessing DAPS may therefore function as a useful marker of risk, both for nonremission/worsening of psychotic symptoms and for a range of other poor clinical outcomes. The analysis underlines the value of dynamic assessment of variables for incorporation into predictive modeling. Further attention should be paid to treatments that specifically target DAPS, including the possible value of “third wave” psychotherapies,59,60 and the mechanisms driving distress associated with symptoms, including the possible bidirectional relationship between symptom severity and associated distress.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

Dr McGorry reported receiving grant funding from National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression and unrestricted research funding from AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, Janssen-Cilag, Pfizer, and Novartis, as well as honoraria for educational activities with AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, Janssen-Cilag, Pfizer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Roche, and the Lundbeck Institute. Drs Nelson, Hickie, Yung, and Amminger have received National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) funding. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Funding

The Neurapro study was supported by the Stanley Medical Research Institute (07TGF-1102), the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC; grant 566529) and the Colonial Foundation.

References

- 1. Yung AR, McGorry PD, McFarlane CA, Jackson HJ, Patton GC, Rakkar A. Monitoring and care of young people at incipient risk of psychosis. Schizophr Bull. 1996;22(2):283–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fusar-Poli P, Bonoldi I, Yung AR, et al. . Predicting psychosis: meta-analysis of transition outcomes in individuals at high clinical risk. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(3):220–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nelson B, Yuen HP, Wood SJ, et al. . Long-term follow-up of a group at ultra high risk (“prodromal”) for psychosis: the PACE 400 study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(8):793–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fusar-Poli P, Borgwardt S, Bechdolf A, et al. . The psychosis high-risk state: a comprehensive state-of-the-art review. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(1):107–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Addington J, Farris M, Stowkowy J, Santesteban-Echarri O, Metzak P, Kalathil MS. Predictors of transition to psychosis in individuals at clinical high risk. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2019;21(6):39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Beck K, Andreou C, Studerus E, et al. . Clinical and functional long-term outcome of patients at clinical high risk (CHR) for psychosis without transition to psychosis: a systematic review. Schizophr Res. 2019;210:39–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cropley VL, Lin A, Nelson B, et al. . Baseline grey matter volume of non-transitioned “ultra high risk” for psychosis individuals with and without attenuated psychotic symptoms at long-term follow-up. Schizophr Res. 2016;173(3): 152–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. de Wit S, Schothorst PF, Oranje B, Ziermans TB, Durston S, Kahn RS. Adolescents at ultra-high risk for psychosis: long-term outcome of individuals who recover from their at-risk state. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2014;24(6):865–873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Polari A, Lavoie S, Yuen HP, et al. . Clinical trajectories in the ultra-high risk for psychosis population. Schizophr Res. 2018;197:550–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lin A, Wood SJ, Nelson B, Beavan A, McGorry P, Yung AR. Outcomes of nontransitioned cases in a sample at ultra-high risk for psychosis. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(3):249–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yung AR, Nelson B, Thompson A, Wood SJ. The psychosis threshold in Ultra High Risk (prodromal) research: is it valid? Schizophr Res. 2010;120(1–3):1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fusar-Poli P, Cappucciati M, Borgwardt S, et al. . Heterogeneity of psychosis risk within individuals at clinical high risk: a meta-analytical stratification. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73(2):113–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rapado-Castro M, McGorry PD, Yung A, Calvo A, Nelson B. Sources of clinical distress in young people at ultra high risk of psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2015;165(1):15–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Peters E, Ward T, Jackson M, et al. . Clinical relevance of appraisals of persistent psychotic experiences in people with and without a need for care: an experimental study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2017;4(12):927–936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Morrison AP. The interpretation of intrusions in psychosis: an integrative cognitive approach to hallucinations and delusions. Behav Cogn Psychother. 2001;29:257–276. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bentall RP, Kinderman P, Kaney S. The self, attributional processes and abnormal beliefs: towards a model of persecutory delusions. Behav Res Ther. 1994;32(3):331–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Morrison AP, Bentall RP, French P, et al. . Randomised controlled trial of early detection and cognitive therapy for preventing transition to psychosis in high-risk individuals: study design and interim analysis of transition rate and psychological risk factors. Br J Psychiatry. 2002;181(suppl 43):s78–s84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Stowkowy J, Perkins DO, Woods SW, Nyman K, Addington J. Personal beliefs about experiences in those at clinical high risk for psychosis. Behav Cogn Psychother. 2015;43(6):669–675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Power L, Polari AR, Yung AR, McGorry PD, Nelson B. Distress in relation to attenuated psychotic symptoms in the ultra-high-risk population is not associated with increased risk of psychotic disorder. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2016;10(3):258–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Falkenberg I, Valmaggia L, Byrnes M, et al. . Why are help-seeking subjects at ultra-high risk for psychosis help-seeking? Psychiatry Res. 2015;228(3):808–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rice S, Polari A, Thompson A, Hartmann J, McGorry P, Nelson B. Does reason for referral to an ultra-high risk clinic predict transition to psychosis? Early Interv Psychiatry. 2019;13(2):318–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Yung AR, Nelson B, Baker K, Buckby JA, Baksheev G, Cosgrave EM. Psychotic-like experiences in a community sample of adolescents: implications for the continuum model of psychosis and prediction of schizophrenia. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2009;43(2):118–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Armando M, Nelson B, Yung AR, et al. . Psychotic-like experiences and correlation with distress and depressive symptoms in a community sample of adolescents and young adults. Schizophr Res. 2010;119(1–3):258–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Legge SE, Jones HJ, Kendall KM, et al. . Association of genetic liability to psychotic experiences with neuropsychotic disorders and traits. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76(12):1256–1265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Powers ARIII. Psychotic experiences in the general population: symptom specificity and the role of distress and dysfunction. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76(12):1228–1229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Markulev C, McGorry PD, Nelson B, et al. . NEURAPRO-E study protocol: a multicentre randomized controlled trial of omega-3 fatty acids and cognitive-behavioural case management for patients at ultra high risk of schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2017;11(5):418–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. McGorry PD, Nelson B, Markulev C, et al. . Effect of ω-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in young people at ultrahigh risk for psychotic disorders: the NEURAPRO randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(1):19–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nelson B, Amminger GP, Yuen HP, et al. . NEURAPRO: a multi-centre RCT of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids versus placebo in young people at ultra-high risk of psychotic disorders—medium-term follow-up and clinical course. NPJ Schizophr. 2018;4(1):11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hartmann JA, McGorry PD, Schmidt SJ, et al. . Opening the black box of cognitive-behavioural case management in clients with ultra-high risk for psychosis. Psychother Psychosom. 2017;86(5):292–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Berger M, Nelson B, Markulev C, et al. . Relationship between polyunsaturated fatty acids and psychopathology in the NEURAPRO clinical trial. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hartmann JA, Schmidt SJ, McGorry PD, et al. . Trajectories of symptom severity and functioning over a three-year period in a psychosis high-risk sample: a secondary analysis of the Neurapro trial. Behav Res Ther. 2020;124:103527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Yung AR, Yuen HP, McGorry PD, et al. . Mapping the onset of psychosis: the Comprehensive Assessment of At-Risk Mental States. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2005;39(11–12):964–971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Nelson B, Amminger GP, Yuen HP, et al. . Staged treatment in early psychosis: a sequential multiple assignment randomised trial of interventions for ultra high risk of psychosis patients. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2018;12(3):292–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Overall J, Gorham D. The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Psychol Rep. 1962;10:799–812. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Montgomery SA, Asberg M. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br J Psychiatry. 1979;134:382–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Andreasen NC. The Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS). Iowa City: The University of Iowa; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Young RC, Biggs JT, Ziegler VE, Meyer DA. A rating scale for mania: reliability, validity and sensitivity. Br J Psychiatry. 1978;133:429–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Goldman HH, Skodol AE, Lave TR. Revising axis V for DSM-IV: a review of measures of social functioning. Am J Psychiatry. 1992;149(9):1148–1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Cornblatt BA, Auther AM, Niendam T, et al. . Preliminary findings for two new measures of social and role functioning in the prodromal phase of schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2007;33(3):688–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Richardson J, Iezzi A, Khan MA, Maxwell A. Validity and reliability of the Assessment of Quality of Life (AQoL)-8D multi-attribute utility instrument. Patient. 2014;7(1):85–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kinderman P, Bentall R. A new measure of causal locus: the Internal, Personal and Situational Attributions Questionnaire. Pers Individ Differ. 1996;20(2):261–264. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Rizopoulos D. Joint Models for Longitudinal and Time-to-Event Data: With Applications in R. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Yuen HP, Mackinnon A, Nelson B. A new method for analysing transition to psychosis: joint modelling of time-to-event outcome with time-dependent predictors. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2018;27(1):1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Caspi A, Houts RM, Belsky DW, et al. . The p factor: one general psychopathology factor in the structure of psychiatric disorders? Clin Psychol Sci. 2014;2(2):119–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Caspi A, Moffitt TE. All for one and one for all: mental disorders in one dimension. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(9):831–844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hazan H, Spelman T, Amminger GP, et al. . The prognostic significance of attenuated psychotic symptoms in help-seeking youth. Schizophr Res. 2020;215:277–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Iorfino F, Scott EM, Carpenter JS, et al. . Clinical stage transitions in persons aged 12 to 25 years presenting to early intervention mental health services with anxiety, mood, and psychotic disorders. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76(11):1167–1175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Shah JL, Scott J, McGorry PD, et al. ; International Working Group on Transdiagnostic Clinical Staging in Youth Mental Health . Transdiagnostic clinical staging in youth mental health: a first international consensus statement. World Psychiatry. 2020;19(2):233–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Nelson B, McGorry PD, Wichers M, Wigman JTW, Hartmann JA. Moving from static to dynamic models of the onset of mental disorder: a review. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(5):528–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Yuen HP, Mackinnon A, Hartmann J, et al. . Dynamic prediction of transition to psychosis using joint modelling. Schizophr Res. 2018;202:333–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Studerus E, Beck K, Fusar-Poli P, Riecher-Rossler A. Development and validation of a dynamic risk prediction model to forecast psychosis onset in patients at clinical high risk. Schizophr Bull. 2020;46(2):252–260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Cannon TD, Yu C, Addington J, et al. . An individualized risk calculator for research in prodromal psychosis. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(10):980–988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Fusar-Poli P, Rutigliano G, Stahl D, et al. . Development and validation of a clinically based risk calculator for the transdiagnostic prediction of psychosis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(5):493–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Zhang T, Xu L, Tang Y, et al. . Prediction of psychosis in prodrome: development and validation of a simple, personalized risk calculator. Psychol Med. 2019;49(12):1990–1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Brett CM, Peters EP, Johns LC, Tabraham P, Valmaggia LR, McGuire P. Appraisals of Anomalous Experiences Interview (AANEX): a multidimensional measure of psychological responses to anomalies associated with psychosis. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 2007;51:s23–s30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Faillie JL. Indication bias or protopathic bias? Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2015;80(4):779–780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Berk M, Parker G. The elephant on the couch: side-effects of psychotherapy. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2009;43(9):787–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Nelson B, Sass LA, Skodlar B. The phenomenological model of psychotic vulnerability and its possible implications for psychological interventions in the ultra-high risk (‘prodromal’) population. Psychopathology. 2009;42(5): 283–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Hickey T, Nelson B, Meadows G. Application of a mindfulness and compassion-based approach to the at risk mental state. Clin Psychol. 2017;21:104–115. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Hickey T, Pen Name E, Nelson B, Meadows G. Mindfulness and compassion for youth with psychotic symptoms: a description of a group program and a consumer’s experience. Psychosis. 2019;11(4):342–349. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.