Abstract

Background

Exosomes are the smallest extracellular vesicles (30–150 nm) secreted by all cell types, including synovial fluid. However, because biological fluids are complex, heterogeneous, and contain contaminants, their isolation is difficult and time-consuming. Furthermore, the pathophysiology of osteoarthritis (OA) involves exosomes carrying complex components that cause macrophages to release chemokines and proinflammatory cytokines. This narrative review aims to provide in-depth insights into exosome biology, isolation techniques, role in OA pathophysiology, and potential role in future OA therapeutics.

Methods

A literature search was conducted using PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science databases for studies involving exosomes in the osteoarthritis using keywords "Exosomes" and "Osteoarthritis". Relevant articles in the last 15 years involving both human and animal models were included. Studies involving exosomes in other inflammatory diseases were excluded.

Results

Despite some progress, conventional techniques for isolating exosomes remain laborious and difficult, requiring intricate and time-consuming procedures across various body fluids and sample origins. Moreover, exosomes are involved in various physiological processes associated with OA, like cartilage calcification, degradation of osteoarthritic joints, and inflammation.

Conclusion

The process of achieving standardization, integration, and high throughput of exosome isolation equipment is challenging and time-consuming. The integration of various methodologies can be employed to effectively address specific issues by leveraging their complementary benefits. Exosomes have the potential to effectively repair damaged cartilage OA, reduce inflammation, and maintain a balance between the formation and breakdown of cartilage matrix, therefore showing promise as a therapeutic option for OA.

Keywords: Biomarkers, Cartilage, Exosomes, Inflammation, Isolation techniques, Joint diseases, Macrophages, Osteoarthritis, Pathophysiology, Therapeutics

Introduction

Exosomes are a subset of small, membranous extracellular vesicles of about 40–150 nm encompassing molecules including proteins, DNAs, and RNAs. They are primarily created by the breakdown of lysosomal particles that are discharged into the extracellular matrix after the fusion of outer membrane and cell membrane [1]. Exosomes are secreted by almost all types of cells and they are naturally found in various body fluids, such as blood, saliva, cerebrospinal fluid, urine, and synovial fluid [2–5]. Furthermore, they play a key role in intercellular communication, whose cargos or components depend on their cell of origin [6]. Because of their minimal invasiveness, there is a growing interest in studying the role of exosomes as potential biomarkers in disease diagnosis and prognosis [7].

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a type of degenerative disease caused by multiple factors, such as obesity, strain, joint deformities, and trauma. It mostly affects the mid-aged or elderly population [8]. The hallmarks of OA include degenerated cartilage, osteocyte formation, angiogenesis, and synovial inflammation. The notable symptoms of OA include joint pain, joint stiffness, and joint swelling. The pathophysiology of OA is complex and remains unclear. However, OA has been reported to be linked to metabolic diseases, trauma, and weight gain [9]. At present, the traditional treatment options for OA are pain killers, intraarticular agent injection, and physical therapy. Though these approaches provide only temporary relief, surgical intervention like total knee replacement, remains a permanent solution [10]. However, the future long-term rehabilitation issues and complications pose a serious concern.

Numerous studies on the association between OA and exosomes have been reported to date. Exosomes play a key function in OA pathogenesis, including inflammatory response regulation and maintaining cartilage tissue homeostasis. Furthermore, apart from being the potential biomarkers for OA diagnosis, multiple studies have suggested therapeutic role of exosomes in OA-associated patients [11]. In this study, we present a narrative review providing deep insights into better understanding of exosome biology, isolation techniques, role in OA pathophysiology, and potential role in future OA therapeutics. A literature search for studies involving exosomes in osteoarthritis was conducted using the keywords "Exosomes" and "Osteoarthritis" in the PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science databases. Relevant articles from the last 15 years on the role of exosomes and their components in OA, using both human and animal models, were included. Furthermore, studies involving exosomes in other inflammatory joint diseases were excluded.

Background

Discovery

Exosomes are small structures, approximately one thousand times smaller than a typical cell, which were first identified by Rose Johnstone in 1983 [12]. They were later referred to as “platelet dust” in human plasma by Wolf et al. [13]. Rose Johnstone's initial research focused on examining the depletion of the transferrin receptor off the outer layer of reticulocytes during their maturation process. By conjugating gold nanoparticles to transferrin, she was able to detect the encapsulation of the receptors inside endosomes, particularly into internal vesicles having a size of approximately 50 nm. Subsequently, the cells generated these "intraluminal vesicles" through exocytosis, and they were thereafter referred to as "exosomes" [14].

Following that, numerous cell lines demonstrating the release of these vesicles in vitro and diverse biological fluids were examined for their potential to contain EVs [15]. EVs were classified into three types based on their release mechanism and size: microvesicles (< 1000 nm), apoptotic bodies (> 1000 nm), and exosomes (< 200 nm). This study focuses on exosomes, the smallest EVs formed by the fusion of late endosomes or multivesicular bodies (MVBs) and released into the extracellular space.

Biogenesis, Release, and Uptake

Figure 1 illustrates a step-by-step process in the biogenesis of exosomes. Exosomes biogenesis includes various cellular steps. Initially, endosome formation originates by the inward budding of plasma membrane, resulting in an ‘inside-out’ internal structure having exact same membrane composition. Inward budding of endosome membrane into the surrounding lumina forms an intraluminal vesicle (ILVs). During maturation, the cargoes including RNAs, proteins, and lipids are incorporated into ILV through an endosomal-sorting complex that is required for transport (ESCRT)-dependent or -independent pathways. Matured endosomes that contain multiple ILVs are termed as multi-vesicular bodies (MVBs). Subsequently, these MVBs are transported to the trans-Golgi network for endosome recycling, where they must go through one of the possible outcomes. They can either be transported to lysosomes for enzymatic breakdown or be transported toward the plasma membrane, wherein the vesicles are released as exosomes [16]. MVB fusion with the cellular membrane is a fine-tuned process, which requires several crucial factors, such as Rab GTPases and SNARE complexes. Exosomal cargoes from the source cell can be further delivered to target cells via endocytosis, direct membrane fusion, and receptor–ligand interaction [17].

Fig. 1.

Biogenesis and secretion of Exosomes. Drawn using BioRender

Exosome Composition

The exosome components vary based on the origin cell types and multiple pathophysiological conditions. Moreover, their origin poses significant impact on the exosome composition. It has been widely reported that exosome contains various biomolecules, such as proteins, lipids, cytokines, transcription factors, and nucleic acids including different types of mRNAs, microRNAs (miRNAs), long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs), mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), and transfer RNA (tRNA) [18]. Proteins constituted inside the exosomes are classified into two groups: first, a common group with constituents that take part in various processes, such as exosome biogenesis, vesicle secretion and formation, like programmed cell death 6 interacting protein and tumor susceptibility gene 101 whose secretion is based on proteins like heat shock proteins (such as HSP70, HSP90), Rab GTPase proteins, and CD63 and CD81 proteins. The other group includes cell-specific components like CD45 and MHC-II that closely regulate antigen-processing process [19].

Exosome Isolation Methods

Isolation methods for exosomes from various sources are mainly based on three biophysical characteristics, which are size and density, immuno-affinity separation and polymer-based precipitation. Multiple studies have compared the purity and yield of exosomes from different isolation methods [20–22]. To date, there are various kits available for exosome isolation; however, extensive research is on-going to develop an ideal, robust, and reliable isolation technique. Figure 2 illustrates different isolation techniques for exosomes.

Fig. 2.

Different isolation methods for exosomes. Drawn using BioRender

Size- and Density-Based Methods

The size- and density-based technique works on the principle where larger components, such as cells (live and dead) and debris, along with smaller components such as macromolecules, are eliminated from the sample. This can be achieved by several methods, such as ultracentrifugation, ultrafiltration, and size-exclusion chromatography. Exosome isolation using ultracentrifugation, where a sample centrifuged at a speed of 100,000 xg, is considered as the gold standard method [23]. Their yield and purity are affected by the centrifuge time, rotor type, or centrifugal force. The advantages of ultracentrifugation method include reliability to isolations from large volume of samples and high purity, while the disadvantages include time-consuming and high set-up costs [24]. Meanwhile, ultrafiltration method employs membranes with varying molecular weight to separate exosomes of specific size. The yield using ultrafiltration is on a par with the ultracentrifugation with significant lower processing time and easy set-up [25]. In addition, size-exclusion chromatography employs a column for serial elution of subtypes of extracellular vesicles of varying sizes, with smaller particles held onto the pores of static phases and larger particles released with mobile phase [26]. Table 1 compares the different traditional methods of exosome isolation.

Table 1.

Comparison of different traditional exosome isolation methods

| Method | Principle | Sample source | Recovery | Purity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Differential ultracentrifugation | Size and density | Blood, urine, saliva, cell culture medium | Low | Medium |

| Density gradient centrifugation | Size and density | Nucleic acid, cell component, protein complex | Low | High |

| Ultrafiltration | Size | Blood, urine, cell culture medium | High | Low |

| Size-exclusion chromatography | Size | Blood, urine, plasma | Relatively-low | High |

Immunoaffinity Separation

Immunoaffinity separation allows specific isolation of exosomes unlike the other two methods mentioned previously. Preferred subtype of extracellular vesicles can be obtained from the sample based on the target CD81, CD63, Rab5, CD9, CD82 surface marker proteins [27, 28]. This method can be based on two principles which are enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and immunoprecipitation. ELISA method uses antibodies to immobilize the target antigen on exosome surface. Through subsequent washing, un-attached elements are eluted, while the attached exosomes are detected using secondary antibody containing a reported enzyme. Moreover, in immunoprecipitation method, the antibodies are fixed on to solid-state matrices, which commonly uses polymeric or magnetic beads. It yields higher efficiency and sensitivity, thus enabling surface immunoanalysis [29].

Polymer-Based Precipitation

This method works on the principle that the solubility of exosomes is reduced by adding polymer molecules, which are water-soluble and amphiphilic. By engaging the water molecules around exosomes, these polymer molecules establish a hydrophobic microenvironment, leading to exosome precipitation. Generally, overnight incubation with polyethylene glycol (PEG) is used to precipitate exosomes comparatively more easily and at low-speed centrifugation [30]. An aqueous two-phase system is another novel precipitation technique that is based on separation of different particles in different phases, generates a more exosome. When it is treated with two distinct solutions (dextran and PEG solutions), a lower phase containing accumulated exosomes and an upper phase containing accumulated proteins and other molecules are formed [31, 32].

Exosomes in OA Pathogenesis

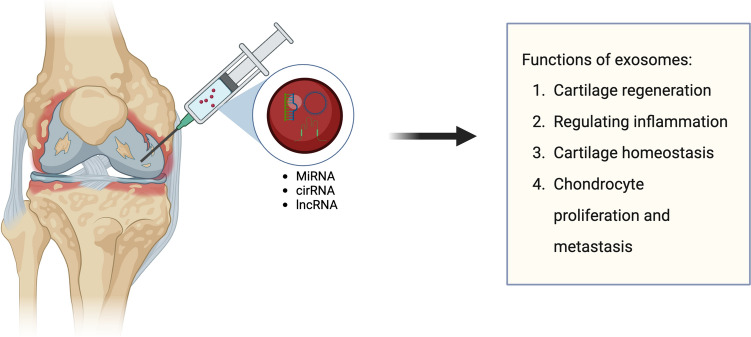

Recent trends suggest that a number of studies investigating the role of exosomes in various joint diseases is on the rise. Exosomes regulate gene expression and their downstream pathophysiological processes via intercellular communication [33] via their constituents, such as microRNAs. In addition to the various beneficial biological functions associated with exosomes, chondrocytes, fibroblasts, immune cells, and synoviocytes in an OA joint can communicate by passing pathogenic signals to each other via exosomes. These communications may interfere with the joint's homeostasis and microenvironment, thereby advancing the disease condition. In the synovial tissue of OA patients, pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha, IL-6, Il-1beta, and IL-22, have been found to be overexpressed [34]. Figure 3 depicts the different functions of exosomes in pathology of OA.

Fig. 3.

Different functions of exosomes in OA pathophysiology. Drawn using BioRender

Exosomes from OA were able to negatively regulate the gene expression of chondrocytes according to some of the earliest studies demonstrating the association between exosomes and OA pathology. When treating articular cartilage chondrocytes with OA-derived exosomes, one study found increased expression of catabolic and inflammatory genes and decreased expression of anabolic genes [35]. Exosomes derived from OA patients' synovial fluid significantly stimulated the release of multiple inflammatory metalloproteinases, chemokines, and cytokines via M1 macrophages [36]. Macrophages treated with exosomes derived from synovial osteoarthritis stimulated osteoclast formation and proliferation [37]. In addition, Nakasa et al. investigated the role of exosomes in intercommunication between chondrocytes and other cells in OA joints, where exosomes derived from IL-1beta-treated chondrocytes and synoviocytes revealed a threefold increase in MMP-13 secretion [38]. In a similar study by Kato et al. [39], exosomes increased production of MMP-13 and ADAMTS-5 while decreasing expression of ACAN and Col2a1.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small coding RNAs demonstrated miRNAs to be involved in the regulation of osteoclasts (miR-31) and osteoblasts (miR-140-3p) [40, 41]. The miRNA screening of exosomes from IL-1beta-induced fibroblasts revealed a total of 50 differentially expressed miRNAs, including miR-199b and miR-4454, which are pro-inflammatory and involved in cartilage regeneration [42]. Furthermore, gender-specific differences in exosomal miRNA expression have been reported. Exosomal miRNAs that are specific to female OA have been shown to be regulated by estrogen via the TLR signaling pathway. This can be attributed to why the prevalence of OA is higher in women, particularly after menopause [43]. Exosomes derived from chondrocytes of OA patients showed a significant reduction in the expression of miR-92a-3p, which was shown to target WNT5A in chondrocytes and MSCs [44]. It has been demonstrated that WNT5A plays a crucial role in chondrogenic differentiation and cartilage degeneration [45]. Mao et al. found that exosomal miR-95-5p is downregulated in OA chondrocytes and can modulate cartilage microenvironment and formation by targeting HDAC2/8, which inhibits cartilage-specific genes, thereby impeding cartilage formation [36, 46]. In addition to exosomal miRNAs, exosomal proteins also contribute to the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis. Exosomes derived from OA chondrocytes exhibited elevated levels of senescence and overexpression of the channel protein connexin43 (Cx43) [47].

Therapeutic Applications of Exosomes in OA

Mesenchymal Stem Cell (MSC)-Derived Exosomes

During cartilage regeneration process, exosomes play a key role as mediators for intercellular communication and induction of multiple cellular processes by modulating various signaling pathways. Cartilage tissue regeneration involves several paracrine signaling in MSC populations. A major therapeutic function of MSC-derived exosomes is their anti-inflammatory potency. During OA pathogenesis, pro-inflammatory mediators, such as IL-1beta and TNF-alpha, are upregulated [48, 49]. Since inflammation is closely associated with OA pathogenesis, the anti-inflammatory potency of MSC-derived exosomes could be utilized in OA therapeutics. A study using exosomes from adipose-derived MSCs impeded the cartilage degeneration and asserted their anti-inflammatory function [50]. Furthermore, in OA patients, exosomes derived from bone marrow MSCs (BMSCs) can impede negative effects of various inflammatory mediators and also the TNF-alpha-induced inflammatory effects on cartilage homeostasis [51]. Exosomes from BMSCs when treated to chondrocytes of OA patients decrease the expression of COX2 (an OA marker) and various proinflammatory interleukins (IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, and IL-17). Table 2 depicts the therapeutic effects of exosomes in OA.

Table 2.

Therapeutic effects of different source-derived exosomes

| Exosomes | Target cells | Mechanisms | Biological effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| BMSCs-derived exosomes | Synovial fibroblasts | Increase the expression of anabolic marker genes while decreasing catabolic and inflammatory marker genes | Repair of injured cartilage and subchondral bone |

| Osteoarthritic chondrocytes | ERK, AKT and p38 pathways | Inhibit apoptosis | |

| Macrophages | MiR-26a-5p/PTGS2 pathway | Restrict synovial fibroblast and macrophage activity | |

| AMSCs-derived exosomes | Osteoarthritis chondrocytes | Upregulate cytokine IL-10 and collagen II and decrease proinflammatory mediators | Cartilage regeneration and inflammatory modulation |

| hUSCs-derived exosomes | Osteoarthritis chondrocytes | Decrease the expression of endothelial growth factor A (VEGFA) gene | Promote the proliferation and migration capacity of OA chondrocytes |

| PRP-Exos | Osteoarthritic chondrocyte | WNT/β-catenin signaling pathway | Stimulate chondrocytes proliferation and migration |

| EMSCs-derived exosomes | Osteoarthritic chondrocytes | Balance the synthesis and degradation of cartilage matrix | Prevent the development of cartilage destruction |

Furthermore, in vivo, exosomal Wnt5a and Wnt5b were shown to inhibit OA by inducing the Yes-associated protein (YAP) via the Wnt signaling pathway and promoting chondrocyte proliferation, which in turn reduces ECM production. The exosomes obtained from miR-140-5p-upregulated synovial MSCs were shown to prevent this ECM secretion [52]. The miR-129-5p in synovial MSC exosomes is downregulated and reported to inhibit the progression of IL-1beta induced OA by targeting the 3’UTR of HMGB1. Thus, exosomes rich in miR-129-5p, via negative regulation of HMGB1, can significantly reduce the inflammatory reactions and chondrocyte apoptosis [53]. In OA patients and synovial fibroblasts treated with IL-1β, PTGS2 is high and MiR-26a-5p is low. PTGS2 is targeted by miR-26a-5p. By inhibiting PTGS2, miR-26a-5p overexpression protects synovial fibroblasts. Obviously, overexpression of miR-26a-5p inhibits PTGS2-mediated synovial fibroblast injury in OA, which is important for treating OA [54]. In in vivo, overexpression of miR-126-3p from synovial fibroblast-derived exosomes impedes the cartilage damage and chondrocyte inflammation, which may have therapeutic value for OA patients [55]. Exosomes derived from synovial fibroblasts are known to regulate disease prognosis, involving inflammation and cartilage degeneration. One study investigated the immuno-modulatory function of exosomes from late OA patients on macrophages [56]. Upon exosome treatment, macrophages were shown to secrete multitude of pro-inflammatory chemokines and cytokines like MMP12, CCL15, IL-1B, CCL1, and CCL8. Another study revealed that exosomes, upon treatment with chondrocytes, reduced the cell viability and increased the expression of pro-inflammatory genes like IL-6 and TNF-alpha [55].

Human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) are another cell source for exosome isolation. In an in vivo model, hESCs-derived exosomes promoted Col II expression and downregulated ADAMTS5 expression by IL-1β treatment [57]. Notably, exosome-mediated physiological responses in cartilage repair includes (1) increased chondrocyte proliferation, (2) reduced apoptosis of cartilage cells, (3) reduced pro-inflammatory synovial cytokines, (4) increased M2 macrophage infiltration, and (5) regulated immune phenotype and response. Furthermore, exosomes derived from embryonic MSCs (ESCs) have demonstrated the ability to decrease matrix breakdown and promote cartilage healing in animal models [58].

In addition, due of the ease of arthroscopy, exosomes obtained from adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells (ADSCs) are being used more recently. Exosomes from ADSCs were shown to downregulate apoptosis-related beta-galactosidase activity, thus reducing the secretion of pro-inflammatory in OA osteoclasts [59]. Similar findings were reported in OA chondrocytes stimulated with IL-1beta [60]. Wu et al. demonstrated that exosomal miR-100-5p from ADSCs prevented cartilage degeneration by inhibiting mTOR, which increases autophagy in OA chondrocytes [61]. Figure 4 shows the different sources of exosomes and their therapeutic applications.

Fig. 4.

Different sources of exosomes and their therapeutic effects. Drawn using BioRender

Platelet-Rich Plasma-Derived Exosomes

Platelet-rich plasma (PRP), obtained from whole blood, has supra-physiological platelet concentrations and many growth factors that can improve bone regeneration, cartilage, and tissue repair. It has been demonstrated that PRP injections in OA patients affect the entire joint environment [62]. In addition to growth factors, PRP is a source of exosomes and their abundant contents. Numerous exosomes are discharged by the platelets. Alexander and colleagues classified two types of autologous blood products and discovered that their derived exosomes are sufficient to induce chondrogenic gene expression in OA chondrocytes [63]. In in vivo, Liu and colleagues discovered that exosomes derived from PRP had the same therapeutic effect on OA as activated PRP. The growth factors contained in these exosomes activated the Wnt/-catenin signaling pathway [64]. However, further research is required to validate and quantify exosomes derived from PRP, which could lead to their application in clinical practice.

Exosomes as OA Biomarkers

The differential expression of exosomal miRNAs and proteins could theoretically render exosomes as diagnostic biomarkers for OA. Nevertheless, their diagnostic value is still in its infancy. Furthermore, the exosomal content varies at various disease stages. Currently, Kellgren–Lawrence grading systems for OA severity possess few discrepancies between image evaluation and clinical picture. This grading system determines whether intra-articular HA injections or surgical interventions are necessary [65]. Consequently, additional biomarkers such as exosomes that are specific and minimally invasive are required. The cargo of exosomes such as miRNAs is relatively stable and can be easily obtained [66]. Table 3 lists different OA biomarkers in exosomes.

Table 3.

Exosomal biomarkers for OA

| Exosomes | Biomarkers | Expression |

|---|---|---|

| Synovial fluid-derived exosomes | lncRNA PCGEM1 | Upregulated |

| Plasma-derived exosomes | miR-193b | Downregulated |

| Stem cell-derived exosomes | Hsa-circ-0104595 | Upregulated |

Zhao et al. examined the diagnostic value of plasma and synovial fluid exosomes in OA patients to distinguish early from progressive OA. Exosomal lncRNA PCGEM1 expression in synovial fluid was significantly higher in late-stage OA than in early-stage OA, and significantly higher in early-stage OA than in normal controls, suggesting that the exosomal lncRNA PCGEM1 in synovial fluid may be an effective biomarker for distinguishing early-stage from late-stage OA [67]. The substantially lower level of plasma exosomal miR-193b-3p in OA patients compared to the control group suggests that exosomal miR-193b-3p may be a novel diagnostic marker for OA [68]. OA synovial fluid exosome proteins differ by gender. Female OA synovial fluid exosomes up-regulate haptoglobin, orosomucoid, and ceruloplasmin and down-regulate apolipoprotein. Male OA synovial fluid exosomes show upregulation of β-2-glycoprotein and complement component five protein and downregulation of Spt-Ada-Gcn5 acetyltransferase (SAGA)-related factor 29. In OA patients, gender differences in synovial fluid exosome protein content may be new diagnostic markers [43]. Furthermore, end-stage OA exosomes contain more cytokines, especially chemokines, than synovial fluid. Synovial fluid microenvironment and exosome-mediated intercellular communication offer a new perspective on OA pathological research, and exosomal cytokines may be new OA diagnostic biomarkers [69].

Conclusion and Future Directions

Exosomes are extensively dispersed in various body fluids, carrying and transmitting crucial signal molecules to form a new intercellular information transmission system. It has been demonstrated that exosomes derived from chondrocytes, synovial cells, and synovial fluid are implicated in the pathogenesis of OA. In the meantime, numerous studies have demonstrated that exosomes from natural cells, particularly MSCs, can maintain chondrocyte homeostasis and reduce the pathological severity of OA, indicating the potential therapeutic value of exosomes for OA/cartilage injury. The properties of exosomes indicate their potential utility in the treatment of OA. To begin with, exosomes have a fairly long lifespan. Exosomes can be extracted from a variety of bodily fluids and kept at 80 °C for extended periods of time. Second, exosomes transport bioactive compounds, such as mRNAs, miRNAs, lncRNAs, and proteins, to shield them from enzymatic degradation, implying that exosomes can deliver nucleic acid and protein medicines to target cells. Third, exosomes can be changed to carry certain medications in order to satisfy the needs of specific treatment regimens. Exosomes have been implicated in both the direct and the indirect regulation of OA pathogenesis. However, the possible efficacy and the targets of exosomes as therapeutic drivers remain unclear and there is still a long way to go in both fundamental and clinical research. In future, it will be necessary to clarify the targets and the mechanisms of exosomes in various tissues and to evaluate the efficacy and the safety of exosomes in vivo.

Acknowledgements

None.

Author Contributions

Nazmul Huda Syed and Asma Abdullah Nurul conceived and designed the study. Syed Nazmul Huda performed the literature search and acquired the data. Syed Nazmul Huda and Iffath Misbah wrote the initial manuscript. Maryam Azlan, Muhammad Rajaei, and Asma Abdullah Nurul critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content and approved for submission.

Funding

This study was funded by the Fundamental Research Grant Scheme (FRGS/1/2021/SKK0/USM/03/7) from Ministry of Higher Education (MOHE), Malaysia.

Data Availability

No new data was generated in this article. This review presents comprehensive insights about the already published data.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical Standard Statement

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by the any of the authors.

Informed consent

For this type of study informed consent is not required.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Buratta S, Tancini B, Sagini K, Delo F, Chiaradia E, Urbanelli L, Emiliani C. Lysosomal exocytosis, exosome release and secretory autophagy: The autophagic-and endo-lysosomal systems go extracellular. International journal of molecular sciences. 2020;21(7):2576. doi: 10.3390/ijms21072576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shi R, Wang PY, Li XY, Chen JX, Li Y, Zhang XZ, Zhang CG, Jiang T, Li WB, Ding W, Cheng SJ. Exosomal levels of miRNA-21 from cerebrospinal fluids associated with poor prognosis and tumor recurrence of glioma patients. Oncotarget. 2015;6(29):26971. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pisitkun T, Shen RF, Knepper MA. Identification and proteomic profiling of exosomes in human urine. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2004;101(36):13368–13373. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403453101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zlotogorski-Hurvitz A, Dayan D, Chaushu G, Korvala J, Salo T, Sormunen R, Vered M. Human saliva-derived exosomes: Comparing methods of isolation. Journal of Histochemistry & Cytochemistry. 2015;63(3):181–189. doi: 10.1369/0022155414564219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li Z, Wang Y, Xiao K, Xiang S, Li Z, Weng X. Emerging role of exosomes in the joint diseases. Cellular Physiology and Biochemistry. 2018;47(5):2008–2017. doi: 10.1159/000491469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu SL, Sun P, Li Y, Liu SS, Lu Y. Exosomes as critical mediators of cell-to-cell communication in cancer pathogenesis and their potential clinical application. Translational Cancer Research. 2019;8(1):298. doi: 10.21037/tcr.2019.01.03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mosquera-Heredia MI, Morales LC, Vidal OM, Barcelo E, Silvera-Redondo C, Vélez JI, Garavito-Galofre P. Exosomes: Potential disease biomarkers and new therapeutic targets. Biomedicines. 2021;9(8):1061. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines9081061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hawker GA, King LK. The burden of osteoarthritis in older adults. Clinics in Geriatric Medicine. 2022;38(2):181–192. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2021.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.He Y, Li Z, Alexander PG, Ocasio-Nieves BD, Yocum L, Lin H, Tuan RS. Pathogenesis of osteoarthritis: Risk factors, regulatory pathways in chondrocytes, and experimental models. Biology. 2020;9(8):194. doi: 10.3390/biology9080194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Uivaraseanu B, Vesa CM, Tit DM, Abid A, Maghiar O, Maghiar TA, Hozan C, Nechifor AC, Behl T, Patrascu JM, Bungau S. Therapeutic approaches in the management of knee osteoarthritis. Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine. 2022;23(5):1–6. doi: 10.3892/etm.2022.11257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fan WJ, Liu D, Pan LY, Wang WY, Ding YL, Zhang YY, Ye RX, Zhou Y, An SB, Xiao WF. Exosomes in osteoarthritis: Updated insights on pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology. 2022;26(10):949690. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2022.949690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pan BT, Johnstone RM. Fate of the transferrin receptor during maturation of sheep reticulocytes in vitro: Selective externalization of the receptor. Cell. 1983;33(3):967–978. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90040-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wolf P. The nature and significance of platelet products in human plasma. British Journal of Haematology. 1967;13(3):269–288. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1967.tb08741.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnstone RM, Adam M, Hammond JR, Orr L, Turbide C. Vesicle formation during reticulocyte maturation. Association of plasma membrane activities with released vesicles (exosomes) Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1987;262(19):9412–9420. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)48095-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Valenzuela MM, Ferguson Bennit HR, Gonda A, Diaz Osterman CJ, Hibma A, Khan S, Wall NR. Exosomes secreted from human cancer cell lines contain inhibitors of apoptosis (IAP) Cancer Microenvironment. 2015;8:65–73. doi: 10.1007/s12307-015-0167-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Williams RL, Urbé S. The emerging shape of the ESCRT machinery. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology. 2007;8(5):355–368. doi: 10.1038/nrm2162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yue B, Yang H, Wang J, Ru W, Wu J, Huang Y, Lan X, Lei C, Chen H. Exosome biogenesis, secretion and function of exosomal miRNAs in skeletal muscle myogenesis. Cell Proliferation. 2020;53(7):e12857. doi: 10.1111/cpr.12857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kalluri R, LeBleu VS. The biology, function, and biomedical applications of exosomes. Science. 2020;367(6478):eaau6977. doi: 10.1126/science.aau6977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang Y, Bi J, Huang J, Tang Y, Du S, Li P. Exosome: A review of its classification, isolation techniques, storage, diagnostic and targeted therapy applications. International Journal of Nanomedicine. 2020;22:6917–6934. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S264498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shu SL, Yang Y, Allen CL, Hurley E, Tung KH, Minderman H, Wu Y, Ernstoff MS. Purity and yield of melanoma exosomes are dependent on isolation method. Journal of Extracellular Vesicles. 2020;9(1):1692401. doi: 10.1080/20013078.2019.1692401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patel GK, Khan MA, Zubair H, Srivastava SK, Khushman MD, Singh S, Singh AP. Comparative analysis of exosome isolation methods using culture supernatant for optimum yield, purity and downstream applications. Scientific Reports. 2019;9(1):5335. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-41800-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tang YT, Huang YY, Zheng L, Qin SH, Xu XP, An TX, Xu Y, Wu YS, Hu XM, Ping BH, Wang Q. Comparison of isolation methods of exosomes and exosomal RNA from cell culture medium and serum. International Journal of Molecular Medicine. 2017;40(3):834–844. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2017.3080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Diaz G, Bridges C, Lucas M, Cheng Y, Schorey JS, Dobos KM, Kruh-Garcia NA. Protein digestion, ultrafiltration, and size exclusion chromatography to optimize the isolation of exosomes from human blood plasma and serum. JoVE (Journal of Visualized Experiments). 2018;134:e57467. doi: 10.3791/57467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yu LL, Zhu J, Liu JX, Jiang F, Ni WK, Qu LS, Ni RZ, Lu CH, Xiao MB. A comparison of traditional and novel methods for the separation of exosomes from human samples. BioMed Research International. 2018;26:2018. doi: 10.1155/2018/3634563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zeringer E, Barta T, Li M, Vlassov AV. Strategies for isolation of exosomes. Cold Spring Harbor Protocols. 2015;2015(4):074476. doi: 10.1101/pdb.top074476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Momen-Heravi F, Balaj L, Alian S, Trachtenberg AJ, Kuo WP. Impact of biofluid viscosity on size and sedimentation efficiency of the isolated microvesicles. Frontiers in Physiology. 2012;29(3):26975. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2012.00162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sall IM, Flaviu TA. Plant and mammalian-derived extracellular vesicles: a new therapeutic approach for the future. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology. 2023 doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2023.1215650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Uddin MJ, Mohite P, Munde S, Ade N, Oladosu TA, Chidrawar VR, Patel R, Bhattacharya S, Paliwal H, Singh S. Extracellular vesicles: The future of therapeutics and drug delivery systems. Intelligent Pharmacy. 2024 doi: 10.1016/j.ipha.2024.02.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sharma P, Ludwig S, Muller L, Hong CS, Kirkwood JM, Ferrone S, Whiteside TL. Immunoaffinity-based isolation of melanoma cell-derived exosomes from plasma of patients with melanoma. Journal of Extracellular Vesicles. 2018;7(1):1435138. doi: 10.1080/20013078.2018.1435138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rider MA, Hurwitz SN, Meckes DG. ExtraPEG: A polyethylene glycol-based method for enrichment of extracellular vesicles. Scientific Reports. 2016;6(1):1–4. doi: 10.1038/srep23978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang D, Zhang W, Zhang H, Zhang F, Chen L, Ma L, Larcher LM, Chen S, Liu N, Zhao Q, Tran PH. Progress, opportunity, and perspective on exosome isolation-efforts for efficient exosome-based theranostics. Theranostics. 2020;10(8):3684. doi: 10.7150/thno.41580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Slyusarenko M, Nikiforova N, Sidina E, Nazarova I, Egorov V, Garmay Y, Merdalimova A, Yevlampieva N, Gorin D, Malek A. Formation and evaluation of a two-phase polymer system in human plasma as a method for extracellular nanovesicle isolation. Polymers. 2021;13(3):458. doi: 10.3390/polym13030458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Duan P, Tan J, Miao Y, Zhang Q. Potential role of exosomes in the pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment of hypoxic diseases. American Journal of Translational Research. 2019;11(3):1184. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhao K, Ruan J, Nie L. Effects of synovial macrophages in osteoarthritis. Frontiers in Immunology. 2023;10(14):1164137. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1164137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhou Q, Cai Y, Jiang Y, Lin X. Exosomes in osteoarthritis and cartilage injury: Advanced development and potential therapeutic strategies. International Journal of Biological Sciences. 2020;16(11):1811. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.41637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li Z, Li M, Xu P, Ma J, Zhang R. Compositional variation and functional mechanism of exosomes in the articular microenvironment in knee osteoarthritis. Cell Transplantation. 2020;20(29):0963689720968495. doi: 10.1177/0963689720968495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Song JE, Kim JS, Shin JH, Moon KW, Park JK, Park KS, Lee EY. Role of synovial exosomes in osteoclast differentiation in inflammatory arthritis. Cells. 2021;10(1):120. doi: 10.3390/cells10010120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nakasa, T., Miyaki, S., Kato, T., Takada, T., Nakamura, Y., Ochi, M. (2012). Exosome derived from osteoarthritis cartilage induces catabolic factor gene expressions in synovium. InORS 2016 Annual Meeting, San Francisco.

- 39.Kato T, Miyaki S, Ishitobi H, Nakamura Y, Nakasa T, Lotz MK, Ochi M. Exosomes from IL-1β stimulated synovial fibroblasts induce osteoarthritic changes in articular chondrocytes. Arthritis Research and Therapy. 2014;16:1–1. doi: 10.1186/ar4679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mizoguchi F, Murakami Y, Saito T, Miyasaka N, Kohsaka H. miR-31 controls osteoclast formation and bone resorption by targeting RhoA. Arthritis Research and Therapy. 2013;15:1–7. doi: 10.1186/ar4282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fushimi S, Nohno T, Nagatsuka H, Katsuyama H. Involvement of miR-140-3p in Wnt3a and TGF β3 signaling pathways during osteoblast differentiation in MC 3T3-E1 cells. Genes to Cells. 2018;23(7):517–527. doi: 10.1111/gtc.12591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li H, Zheng Q, Xie X, Wang J, Zhu H, Hu H, He H, Lu Q. Role of exosomal non-coding RNAs in bone-related diseases. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology. 2021;23(9):811666. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2021.811666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kolhe R, Hunter M, Liu S, Jadeja RN, Pundkar C, Mondal AK, Mendhe B, Drewry M, Rojiani MV, Liu Y, Isales CM. Gender-specific differential expression of exosomal miRNA in synovial fluid of patients with osteoarthritis. Scientific Reports. 2017;7(1):2029. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-01905-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mao G, Zhang Z, Hu S, Zhang Z, Chang Z, Huang Z, Liao W, Kang Y. Exosomes derived from miR-92a-3p-overexpressing human mesenchymal stem cells enhance chondrogenesis and suppress cartilage degradation via targeting WNT5A. Stem Cell Research and Therapy. 2018;9:1–3. doi: 10.1186/s13287-018-1004-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Inoue Y, Kumagai K, Ishikawa K, Kato I, Kusaba Y, Naka T, Nagashima K, Choe H, Ike H, Kobayashi N, Inaba Y. Increased Wnt5a/ROR2 signaling is associated with chondrogenesis in meniscal degeneration. Journal of Orthopaedic Research: official Publication of the Orthopaedic Research Society. 2024 doi: 10.1002/jor.25825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mao G, Hu S, Zhang Z, Wu P, Zhao X, Lin R, Liao W, Kang Y. Exosomal miR-95-5p regulates chondrogenesis and cartilage degradation via histone deacetylase 2/8. Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine. 2018;22(11):5354–5366. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.13808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Varela-Eirín M, Carpintero-Fernández P, Guitián-Caamaño A, Varela-Vázquez A, García-Yuste A, Sánchez-Temprano A, Bravo-López SB, Yañez-Cabanas J, Fonseca E, Largo R, Mobasheri A. Extracellular vesicles enriched in connexin 43 promote a senescent phenotype in bone and synovial cells contributing to osteoarthritis progression. Cell Death and Disease. 2022;13(8):681. doi: 10.1038/s41419-022-05089-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Molnar V, Matišić V, Kodvanj I, Bjelica R, Jeleč Ž, Hudetz D, Rod E, Čukelj F, Vrdoljak T, Vidović D, Starešinić M. Cytokines and chemokines involved in osteoarthritis pathogenesis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2021;22(17):9208. doi: 10.3390/ijms22179208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bodmer JL, Schneider P, Tschopp J. The molecular architecture of the TNF superfamily. Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 2002;27(1):19–26. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(01)01995-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhao C, Chen JY, Peng WM, Yuan B, Bi Q, Xu YJ. Exosomes from adipose-derived stem cells promote chondrogenesis and suppress inflammation by upregulating miR-145 and miR-221. Molecular Medicine Reports. 2020;21(4):1881–1889. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2020.10982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang J, Rong Y, Luo C, Cui W. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes prevent osteoarthritis by regulating synovial macrophage polarization. Aging (Albany NY). 2020;12(24):25138. doi: 10.18632/aging.104110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tao SC, Yuan T, Zhang YL, Yin WJ, Guo SC, Zhang CQ. Exosomes derived from miR-140-5p-overexpressing human synovial mesenchymal stem cells enhance cartilage tissue regeneration and prevent osteoarthritis of the knee in a rat model. Theranostics. 2017;7(1):180. doi: 10.7150/thno.17133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Qiu M, Liu D, Fu Q. MiR-129-5p shuttled by human synovial mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes relieves IL-1β induced osteoarthritis via targeting HMGB1. Life Sciences. 2021;15(269):118987. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.118987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jin Z, Ren J, Qi S. RETRACTED: human bone mesenchymal stem cells-derived exosomes overexpressing microRNA-26a-5p alleviate osteoarthritis via down-regulation of PTGS2. International Immunopharmacology. 2019;78:105946. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2019.105946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhou Y, Ming J, Li Y, Li B, Deng M, Ma Y, Chen Z, Zhang Y, Li J, Liu S. Exosomes derived from miR-126-3p-overexpressing synovial fibroblasts suppress chondrocyte inflammation and cartilage degradation in a rat model of osteoarthritis. Cell Death Discovery. 2021;7(1):37. doi: 10.1038/s41420-021-00418-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhao X, Zhao Y, Sun X, Xing Y, Wang X, Yang Q. Immunomodulation of MSCs and MSC-derived extracellular vesicles in osteoarthritis. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology. 2020;29(8):575057. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2020.575057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang Y, Yu D, Liu Z, Zhou F, Dai J, Wu B, Zhou J, Heng BC, Zou XH, Ouyang H, Liu H. Exosomes from embryonic mesenchymal stem cells alleviate osteoarthritis through balancing synthesis and degradation of cartilage extracellular matrix. Stem Cell Research and Therapy. 2017;8:1–3. doi: 10.1186/s13287-017-0632-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nurul AA, Azlan M, Ahmad Mohd Zain MR, Sebastian AA, Fan YZ, Fauzi MB. Mesenchymal stem cells: Current concepts in the management of inflammation in osteoarthritis. Biomedicines. 2021;9(7):785. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines9070785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tofiño-Vian M, Guillén MI, Perez del Caz MD, Castejón MA, Alcaraz MJ. Extracellular vesicles from adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells downregulate senescence features in osteoarthritic osteoblasts. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity. 2017 doi: 10.1155/2017/7197598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tofiño-Vian M, Guillén MI, Pérez del Caz MD, Silvestre A, Alcaraz MJ. Microvesicles from human adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells as a new protective strategy in osteoarthritic chondrocytes. Cellular Physiology and Biochemistry. 2018;47(1):11–25. doi: 10.1159/000489739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wu J, Kuang L, Chen C, Yang J, Zeng WN, Li T, Chen H, Huang S, Fu Z, Li J, Liu R. miR-100-5p-abundant exosomes derived from infrapatellar fat pad MSCs protect articular cartilage and ameliorate gait abnormalities via inhibition of mTOR in osteoarthritis. Biomaterials. 2019;1(206):87–100. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2019.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Filardo G, Previtali D, Napoli F, Candrian C, Zaffagnini S, Grassi A. PRP injections for the treatment of knee osteoarthritis: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Cartilage. 2021;13(1):364S–S375. doi: 10.1177/1947603520931170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Otahal A, Kramer K, Kuten-Pella O, Weiss R, Stotter C, Lacza Z, Weber V, Nehrer S, De Luna A. Characterization and chondroprotective effects of extracellular vesicles from plasma-and serum-based autologous blood-derived products for osteoarthritis therapy. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology. 2020;25(8):584050. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2020.584050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Liu X, Wang L, Ma C, Wang G, Zhang Y, Sun S. Exosomes derived from platelet-rich plasma present a novel potential in alleviating knee osteoarthritis by promoting proliferation and inhibiting apoptosis of chondrocyte via Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery and Research. 2019;14:1–6. doi: 10.1186/s13018-019-1529-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ahmed SM, Mstafa RJ. Identifying severity grading of knee osteoarthritis from x-ray images using an efficient mixture of deep learning and machine learning models. Diagnostics. 2022;12(12):2939. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics12122939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ingenito F, Roscigno G, Affinito A, Nuzzo S, Scognamiglio I, Quintavalle C, Condorelli G. The role of exo-miRNAs in cancer: A focus on therapeutic and diagnostic applications. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2019;20(19):4687. doi: 10.3390/ijms20194687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhao Y, Xu J. Synovial fluid-derived exosomal lncRNA PCGEM1 as biomarker for the different stages of osteoarthritis. International Orthopaedics. 2018;42:2865–2872. doi: 10.1007/s00264-018-4093-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Miao C, Zhou W. The research progress of exosomes in osteoarthritis, with particular emphasis on the mediating roles of miRNAs and lncRNAs. Frontiers in Pharmacology. 2021;21(12):685623. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.685623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gao K, Zhu W, Li H, Ma D, Liu W, Yu W, Wang L, Cao Y, Jiang Y. Association between cytokines and exosomes in synovial fluid of individuals with knee osteoarthritis. Modern Rheumatology. 2020;30(4):758–764. doi: 10.1080/14397595.2019.1651445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No new data was generated in this article. This review presents comprehensive insights about the already published data.