Abstract

Background

Caused by duplications of the gene encoding peripheral myelin protein 22 (PMP22), Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 1A (CMT1A) is the most common hereditary neuropathy. Despite this shared genetic origin, there is considerable variability in clinical severity. It is hypothesized that genetic modifiers contribute to this heterogeneity, the identification of which may reveal novel therapeutic targets. In this study, we present a comprehensive analysis of clinical examination results from 1,564 CMT1A patients sourced from a prospective natural history study conducted by the RDCRN-INC (Inherited Neuropathy Consortium). Our primary objective is to delineate extreme phenotype profiles (mild and severe) within this patient cohort, thereby enhancing our ability to detect genetic modifiers with large effects.

Methods

We have conducted large-scale statistical analyses of the RDCRN-INC database to characterize CMT1A severity across multiple metrics.

Results

We defined patients below the 10th (mild) and above the 90th (severe) percentiles of age-normalized disease severity based on the CMT Examination Score V2 and Foot Dorsiflexion Strength (MRC scale). Based on extreme phenotype categories, we defined a statistically justified recruitment strategy, which we propose to use in future modifier studies.

Interpretation

Leveraging whole genome sequencing with base pair resolution, a future genetic modifier evaluation will include single nucleotide association, gene burden tests, and structural variant analysis. The present work not only provides insight in the severity and course of CMT1A, but also elucidates the statistical foundation and practical considerations for a cost-efficient and straightforward patient enrollment strategy that we intend to conduct on additional patients recruited globally.

Keywords: Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease, PMP22, whole genome sequencing, phenotype outliers, disease severity, natural history, CMTES, genetic modifiers, CMT1A

Introduction

With an estimated prevalence of 1:2,500, Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease (CMT), also called Hereditary Motor and Sensory Neuropathy (HMSN), is the most common form of inherited neurological disorders (Bird, 1993; Dyck and Lambert, 1968). Patients exhibit length-dependent weakness, muscular atrophy, and sensory loss (Fridman, et al., 2015; Skre, 1974). More than 100 genes have been found to cause CMT with multiple forms of inheritance, and many more likely remain to be discovered (Nagappa M, 2022; Rossor, et al., 2013). The demyelinating forms (CMT1 and CMT4) affect Schwann cells and lead to slowed nerve conduction velocities (Birouk, et al., 1997; Krajewski, et al., 2000). Charcot-Marie-Tooth 1A (CMT1A) is the most frequent CMT subtype (Braathen, 2012; Fridman, et al., 2015; Karadima, et al., 2011). In nearly all patients, CMT1A is caused by a recurrent 1.5 Mb duplication caused by nonallelic homologous recombination which contains the gene encoding peripheral myelin protein 22 (PMP22) on chromosome 17p11.2 (Lupski, et al., 1991; Matsunami, et al., 1992; Raeymaekers, et al., 1991; Zhang, et al., 2010). CMT1A is usually dominantly inherited, but 10–20% of CMT1A patients seen in clinic have de novo duplications(Kanwal, et al., 2011; Lee, et al., 2020; Nelis, et al., 1996).

PMP22 is an integral membrane protein highly expressed by myelinating Schwann cells and is localized to compact myelin (Adlkofer, et al., 1995; Fledrich, et al., 2014; Suh, et al., 1997). Three copies of PMP22 lead to an overexpression of the PMP22 protein, causing destabilization of the myelin sheath and leading to demyelination and secondary axonal loss (Kim, et al., 2012). Therefore, many CMT1A treatment approaches have aimed to decrease the amount of PMP22 expression (Stavrou, et al., 2021). Currently, there is no disease-modifying therapies for CMT1A (Morena, et al., 2019; Stavrou, et al., 2021), however, several promising clinical trials (PREMIER, NCT04762758) and pre-IND studies are under way (Attarian, et al., 2021; Prukop, et al., 2020; Stavrou, et al., 2022). Deletion of one PMP22 copy causes the reciprocal disease Hereditary Neuropathy with Liability to Pressure Palsies (HNPP)(Li, et al., 2013; Pantera, et al., 2020). Given the dosage-sensitive nature of PMP22, therapies involving reducing PMP22 expression levels may require careful adjustment. A hypothesized genetic modifier could provide a safe, alternative drug target.

Genetic modifiers can affect the age of disease onset, disease severity, rate of progression, and other aspects of disease presentation such as the absence or addition of clinical signs (Lamar and McNally, 2014; Mroczek and Sanchez, 2020). Prior CMT1A genetic modifiers studies have identified candidates that require further confirmation (Nam, et al., 2018; Sinkiewicz-Darol, et al., 2015; Tao, et al., 2019a; Tao, et al., 2019b). Four intronic variants in SIPA1L2 showed the strongest association with foot dorsiflexion strength(Tao, et al., 2019b), but the exact haplotypes that offer biologically relevant effects could not be inferred using a GWAS strategy. Recently, a CMT1A mouse model employing a Sipa1l2 deletion validated interactions between Sipa1l2 and the CMT1A phenotype, but the effect on neuropathy was small (George, et al., 2023).

An extreme phenotype approach presumes that the largest allelic effect sizes are contained towards the edges of the phenotypic distributions, thereby increasing the likelihood of detecting differences in relatively small samples sizes. This approach should also reduce the variability of clinical raters and in patient self-reported symptoms, both of which would be more problematic for measures closer to the mean of the distribution.

To define the extremes of the CMT1A phenotype, we used the RDCRN-INC clinical database, which contains prospectively collected natural history data from expert evaluators at multiple centers, to create normative data and to develop an abbreviated clinical inclusion schema (Birouk, et al., 1997; Lamar and McNally, 2014; Li, et al., 2021; Mroczek and Sanchez, 2020; Pantera, et al., 2020; Secchin, et al., 2020; Sheth, et al., 2008; Tao, et al., 2019a). Our approach uses standardized tools in the CMT field and will enable the identification of patients falling into the extremes of clinical quantitative traits. Having defined extreme phenotypes will allow for expedited patient identification, smaller number of enrolled patients, and the option to collect additional data at later time points.

Materials and Methods

Patient Recruitment

As of October 2022, the RDCRN-INC database (https://www.rarediseasesnetwork.org) for protocols 6601 and 6602 contained 24,364 records for 4,207 patients from 2,999 families, collected at 20 centers world-wide. Each INC site had institutional review board approval. Patients were recruited by experienced neurologists and pediatricians, consented, and examined following a standardized CMT protocol. Examinations contained a CMT-specific patient and family history, clinical examinations with focus on motor and sensory function, gait patterns, and foot deformities. Muscle strength was measured using the default scale of the Medical Research Council (MRC). Motor nerve conduction studies of the median and/or ulnar nerve as well as sensory conduction studies of the radial nerve were assessed in some, but not all, patients.

Outcome Measures for CMT1A

The goal of this work is to define a clinically meaningful and statistically solid study design for a whole genome sequencing (WGS) based genetic modifier approach on patients with CMT1A. We herein describe how we will select patients, using defined clinical criteria for extreme phenotypes in statistically justified age categories. For the proposed study design, we performed statistical analyses to determine the most informative clinical outcome measures to define severity. The RDCRN-INC database collects data from patients >3 years of age; the patient age was calculated as the exact time in years between the patient’s date of birth and the date of the examination using the Lubridate package in R statistical software. For ages 3–20, we used the CMT Pediatric Score (CMTPedS), which has been clinically validated for that age group and is sensitive to change with age (Burns, et al., 2012; Cornett, et al., 2017). The CMTPedS is an 11-item test that measures several aspects of disease severity: hand dexterity, strength, sensation, balance, motor functions. Possible scores range from 0–44 and are based on norm-derived z-scores(Burns, et al., 2013). For ages 21 or older, we used the CMT Exam Score version 2 (CMTES) and the CMT Neuropathy Score version 2 (CMTNS) (Murphy, et al., 2011), which delineates mild (CMTNS ≤10), moderate (CMTNS 11–20), and severe (CMTNS >20). The CMTNS is a composite scoring system comprised of 9 items, totaling 36 points. It assesses patient symptoms (3 items), examination findings (4 items), and electrophysiology (2 items). The CMTES, a subset of the CMTNS, focuses on patient symptoms and examination findings while excluding electrophysiology, with a maximum score of 28 (Fridman, et al., 2020). Foot Dorsiflexion Strength (FDS) is a sub-category of both the CMTES and the CMTPedS, and ranges from 0 to 5 on an ordinal scale and (5 = normal strength; 4-,4,4+ = slight, moderate, submaximal strength, respectively; 3 = movement against gravity, but not manual resistance; 2 = movement without gravity, 1 = slight muscle contraction but no movement; grade 0 = no muscle contraction). In our analysis, we used FDS of the left foot and suggest clinicians to use the non-dominant foot when considering severity. For FDS calculations, grade 4- was given a value of 3.5, and grade 4+ was given a value of 4.5. Severity percentiles were calculated using the baseline exams for each patient to avoid bias of patients with multiple follow up exams skewing results.

Extreme Phenotype Sampling

Using relevant outcome measures, we sought to clinically define patients from below the 10th percentile and above the 90th percentile of severity. Severity was considered with respect to patient age. We removed patients with known comorbidities such as diabetes mellitus, chemotherapy. We removed patients with a recorded foot surgery, which could affect their FDS and function, except for patients who had proximal leg weakness, which is a sign of a severe phenotype.

RESULTS

Comprehensive analysis of the INC clinical database

To characterize the spectrum and distribution of CMT1A phenotypes, we analyzed all 24,363 records within the INC database (Table 1). We first removed patients who did not have a positive and documented PMP22 duplication test, as well as patients with specific confounding comorbidities, including diabetes mellitus, and prior chemotherapy. Approximately 28% of the patients had a foot surgery prior to their baseline exam and were removed unless they showed proximal leg weakness of MRC 4, so that ankle surgeries would no longer be a confounder in their assessment. This left 9,620 reported records of 1,978 CMT1A patients from 1,501 families. There were 857 female patients, 692 male patients, and 3 without specification of sex.

Table 1.

Summary of records in INC clinical database for CMT1A patients

| # Events | #CMTES/CMTPedS | #FDS | Mean Age (years) | Median Age (years) | % Male | % Female | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | 9623 | 4042 | 3857 | 34.02±21.3 | 32.4 [0 – 91] | 0.45 | 0.55 |

| Baseline | 1564 | 1329 | 1511 | 33.18±20.6 | 31.9 [0 – 87] | 0.45 | 0.55 |

Abbreviations: FDS, Foot dorsiflexion strength, measured using the MRC scale and was calculated using the score for the patient’s left foot; CMTPedS, Charcot-Marie-Tooth Pediatric Score; CMTES, Charcot-Marie-Tooth Examination Score Version 2.

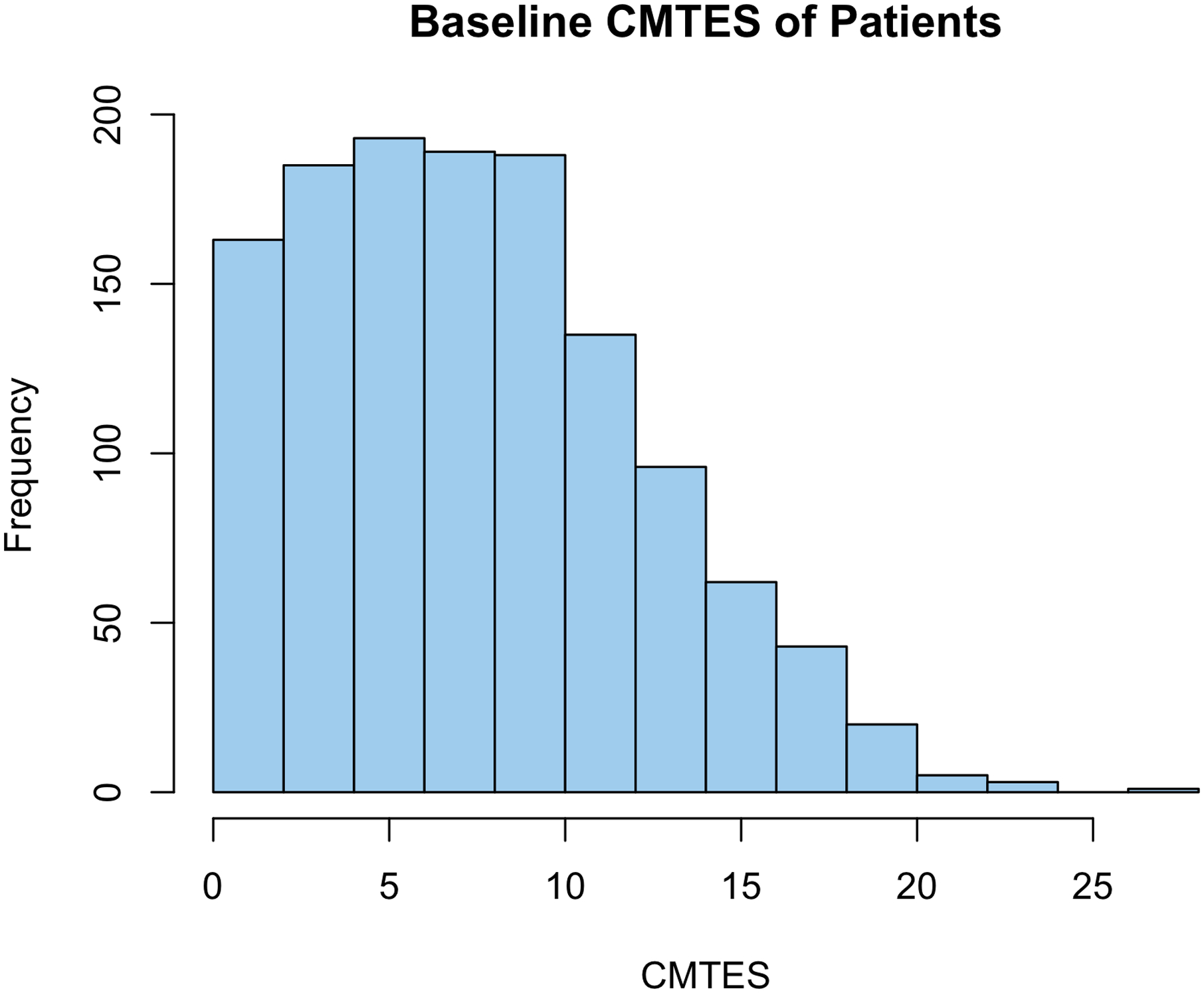

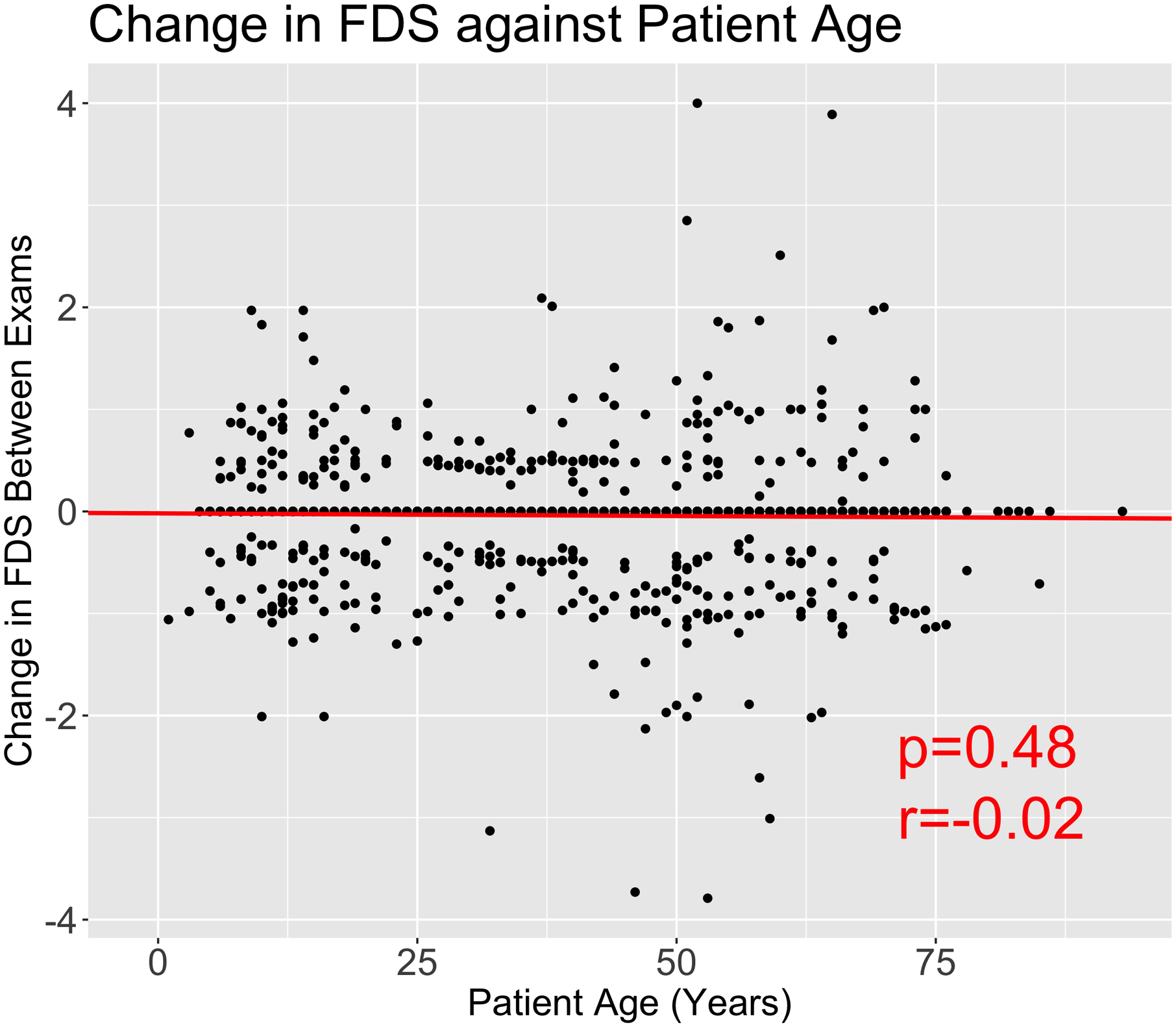

Out of 9,620 filtered records, 4,623 had a visit date information that we could use to calculate age of examination. As in most long duration studies, the records were incomplete (Fig. 1A). For instance, electrophysiological measures were too incomplete to be considered a broad inclusion criterion. To avoid over-representation and potential bias of data from individuals with multiple follow-up exams, we analyzed only the baseline exam of a patient for phenotype correlations. For 1,564 baseline exams, the mean patient age was 32 with a range of 0 to 87 years of age (Fig. 1B). CMTES ranged from 0 to 27 in our cohort (mean=7.97) and MRC foot dorsiflexion ranged from 0 to 5, with all possible scores recorded (mean=3.87) (Fig. 1C, 1D). The distribution of CMTES in the baseline of our cohort suggest the traditional severity grading of mild (CMTNS ≤10), moderate (CMTNS 11–20), or severe (CMTNS >20) is not normally distributed in CMT1A patients. The CMTES and CMTPedS were significantly correlated with patient age, r=0.530, p<0.0001 and r=0.372, p<0.0001, respectively. Foot dorsiflexion strength (FDS) was also significantly correlated with age (r=−0.355, p<0.0001) (Figs. 2A, 2B).

Figure 1. Cohort summary statistics.

(A) Bar plot showing proportion of available data out of 4,623 RDCRN database records. (B) Histogram of patient age (years) at baseline. The RDCRN database contains CMT1A patient exams across all ages. (C) Histogram of baseline CMTES (0–28) for 1,564 CMT1A patients. (D) Histogram of baseline MRC foot dorsiflexion strength (FDS, 0–5) for 1,564 CMT1A patients. Most CMT1A patients had minimal weakness or normal foot strength of MRC 4–5.

Figure 2. Age and strength correlation in CMT1A.

Scatterplot of CMTES (A), Foot dorsiflexion strength (FDS) at MRC scale, left foot (B), CMTES progression (C) and FDS progression (D) against patient age in years with linear regression model shown in red. CMTES and FDS and patient age are highly correlated, emphasizing the need to measure severity against age at examination. The change in CMTES and FDS was calculated as the change in score between exams divided by year. Plots C and D show that there is no significant correlation between patient age and rate of progression for CMTES and FDS.

On cross-sectional assessment, the overall average change for CMTES and FDS per year was 0.224 and −0.039 respectively, and thus comparable to prior studies for the rate of change of CMTES (Fridman, et al., 2020; Kitani-Morii, et al., 2020). Our analysis reveals that progression of CMT1A severity is constant, as measured by CMTES (r=0.037, p=0.194) and FDS (r=−0.020, p=0.4812), irrespective of patient age (Figs. 2C, 2D). Pearson’s correlation coefficient between CMTES and FDS is significant (r=−0.664, p<0.0001), suggesting that both are corresponding clinical measures. Given the correlation between severity and age, we concluded that any model aiming at defining phenotypic outliers needs to adjust for patient age at exam. Importantly, there were no significant differences in severity (CMTES) or progression (change in CMTES) of CMT1A between males and females, p=0.8156 and p=0.8218 respectively.

Devising a simplified enrollment decision schema for clinical use

To enable the identification of severe and mild extremes of CMT1A phenotypes in an anticipated cohort that is still being enrolled, we sought to simplify ad hoc enrollment decisions for a clinical setting by creating age bins. Each bin should contain patients who are expected to show similar phenotypic expression based on the above analyzed cross sectional data. Within each of the five age bins, the correlation between CMTES and current age at exam should be weak (0 < r < 0.2), justifying the age cut offs for each bin. Ideal phenotype comparison would be for every unique birth year; however, our cohort may not contain the exact spectrum of CMT1A phenotype variability. Accordingly, for practical purposes we created age-bins that limited the effect of age on severity, while not over-fitting specific metrics for our large but incomplete dataset. Therefore, we made the age categories broad with realistic age milestones, and that have statistical support. Comparing the bins yields significant differences between age groups but reduces the age-CMTES correlation between age groups (Fig. 3A). Using baseline exam CMTES/CMTPedS measures, we calculated Pearson coefficients to be: Bin 1 (0–20 years of age), r=0.368, age and CMTPedS; Bin 2 (21–40 years of age), r=0.104, age and CMTES; Bin 3 (41–50 years of age), r=0.186, age and CMTES; Bin 4 (51–70 years of age), r=0.096, age and CMTES; and Bin 5 (71+ years of age); r=0.143, age and CMTES. For age group 0–20 years, we used CMTPedS scores and observed a moderate correlation. This is due to clinical disease onset typically being in the second decade of life, demonstrating a starker contrast in severity between childhood and adolescence. Therefore, to guard against erroneously enrolling patients into Bin 1 that present with mild symptoms, we will only enroll severely affected age 0–20-year-old patients (CMTPedS ≥ 28, FDS ≤ 4-). Similarly, we will only enroll mildly affected age patients over 70 years of age (CMTES ≤ 7, FDS = 5) to ensure the phenotype is not exacerbated by age-related confounding factors. In summary, to distinguish mildly and severely affected CMT1A patients, we calculated the bottom and top 10 percentile of our cohort for CMTES and FDS, the two most available clinical measures. The distribution of CMTES and FDS significantly differ between the five age-based bins (Figs. 3A, 3B). There were no differences in CMTES or FDS between males and females for any age group. Results of this analysis are summarized in a detailed metrics in Table 2. Based on this approach, we identified 216 out of 1,978 patients with extreme phenotypes for their age (116 mild, 100 severe). Finally, we have created a one-page printable workflow that can be used by clinicians to make decisions on inclusion into the modifier study (Fig. 4). We envision this one-page flow chart to be available in participating neurology clinics and allow for cost-and time efficient focus of enrollment on patients that qualify as an extreme phenotype.

Figure 3. Statistical definition of proposed age brackets.

Boxplots comparing the distributions of CMTES (A) and FDS (MRC scale) (B) between our proposed age brackets. There are significant differences in the distribution of scores in CMTES between proposed age groups. This supports our decision to model CMT1A severity in respect to patient age. Statistics performed by Wilcoxon signed ranked test between age groups. NS. Not significant, *p<0.05, ***p<0.001

Table 2.

Statistical metrics of the enrollment decision form by age group.

| Bins by age (Years) | Metric | 0th | 10th | 25th | 50th | 75th | 90th | 100th | p-value | mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bin1: 0–20 | CMTPedS | 0 | 8 | 13 | 18 | 24 | 28 | 42 | 0.000 | 18.52 |

| FDS | 0 | 3.5 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 0.734 | 4.12 | |

| Bin2: 21–40 | CMTES | 0 | 2 | 4 | 7 | 10 | 12 | 20 | 0.079 | 7.26 |

| FDS | 0 | 3.5 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 0.257 | 4.24 | |

| Bin3: 41–50 | CMTES | 0 | 3 | 6 | 9 | 12 | 16 | 27 | 0.002 | 9.21 |

| FDS | 0 | 1 | 3.5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 0.005 | 3.68 | |

| Bin4: 51–70 | CMTES | 0 | 5 | 8 | 12 | 15 | 18 | 26 | 0.019 | 11.58 |

| FDS | 0 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 0.331 | 2.98 | |

| Bin5: 71+ | CMTES | 4 | 7 | 11 | 13 | 15 | 18 | 21 | 0.331 | 12.86 |

| FDS | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 0.253 | 2.60 |

Abbreviations: FDS, Foot dorsiflexion strength, measured using the MRC scale and was calculated using the score for the patient’s left foot; CMTPedS, Charcot-Marie-Tooth Pediatric Score; CMTES, Charcot-Marie-Tooth Examination Score Version 2. P-value of the Pearson’s product moment correlation between metric and patient age in respective age bracket.

Figure 4. Schematic of inclusion criteria for CMT1A WGS modifier study.

Clinicians should follow diagram to assess if patient is mild or severe according to the 10th and 90th percentiles of RDCRN database for a given age. We are still collecting samples for WGS and genetic modifier analysis.

Minimal dataset for clinical evaluation

For patients identified as eligible using the simplified enrollment decision form in a clinical setting, we have designed a minimal dataset to use for patient evaluation. The minimal dataset has 10 fields that are required for inclusion: Patient ID, research protocol, sex, date of birth, date of exam, PMP22 duplication confirmed or 1st or 2nd degree relative confirmed (T/F), previous foot surgery (T/F), comorbidities such as diabetes mellitus, hip or knee surgery, chemotherapy, or obesity (T/F, if T then specify), CMTES/CMTPedS, and FDS. The minimal dataset also includes eight optional fields that would be beneficial for analysis: genetic lab of PMP22 duplication, country of origin, ancestry/ethnicity, age at first difficulty walking (years), high-arched feet/foot deformity (T/F), ulnar motor nerve conduction velocity [m/s], ulnar nerve distal compound motor action potential (CMAP) amplitude (mV), as well as the scoring rubric breakdown for the seven categories of the CMTES (Sensory, Motor LL, Motor UL, Pinprick, Vibration, Strength LL, Strength UL). This minimal dataset has been approved by clinical experts within the INC and is as simplified to enable broad participation. We included all 216 INC CMT1A patients (116 mild, 100 severe) that fall into phenotypic extremes according to the above enrollment form. To help ensure that we have the most up-to-date phenotype information, we will prioritize the most recent exam. In instances in which the latest exam is not strictly mild or severe according to our criteria, we suggest considering inclusion if two or more previous exams support a mild or severe phenotype.

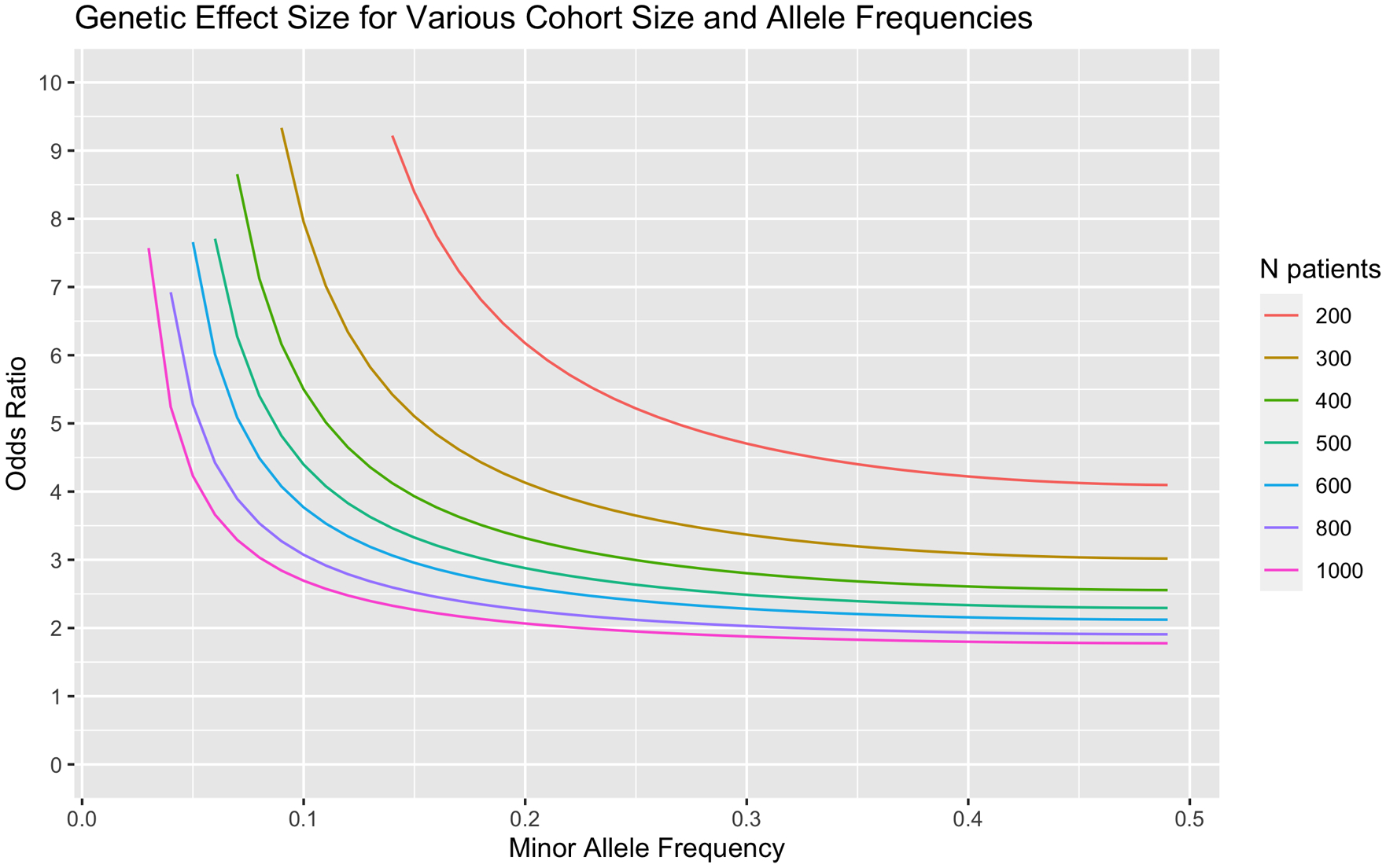

Power calculations

When performing many single statistical tests as in genome wide association studies, some tests will reach significance of p<0.05 by probabilistic chance. The naïve Bonferroni correction method is one common approach to adjust results (Bland and Altman, 1995) by requiring a significance threshold of P<5 × 10−8 for genome wide association studies (Gao, et al., 2008; Pe’er, et al., 2008; Xu, et al., 2014). It is argued that this significance threshold is more than necessary when accounting for linkage disequilibrium with the genome, and a more stringent threshold offers limited benefit when balancing false positive discovery and power (Risch, 1996). Therefore, for our study design, we calculated a preliminary minimum detectable genetic effect size for varying allele frequencies and sample sizes [Fig 5]. We inferred an additive model, alpha=5×10−8, and power=0.8 as parameters for our calculations. This extreme phenotyping approach has an exceptionally large power gain for rare variants (Amanat, et al., 2020), and past GWAS modifier studies for CMT1A have shown success in identifying statistically powered associations with fewer samples than we will use, and with a simpler definition for mild and severe. Based off the power calculations, a sample of at least 400 patients will be a minimum to amass the desired amount of statistical power.

Figure 5. Power calculations of genetic effect size for varying cohort sizes.

Larger cohort sizes increase our power to detect variants with significant effects. Effect size was calculated with an inferred additive model, alpha=5×10−8, and power=0.8. Based off our calculations, we expect to sequence a minimum of 400 patients for extensive modifier analysis.

Discussion

This study proposes an efficient strategy for selecting patients to enroll into genetic modifier studies for CMT1A. Given the constraints on resources, we developed a simplified approach that will preserve the statistical power and minimize initial data demands for participant enrollment. We have defined mild and severe phenotype criteria using CMTES and FDS as clinical markers. A simplified enrollment workflow allows clinicians to focus on enrolling the extreme 20 percent of patients rather than all CMT1A cases. The latter would likely lead to exclusion at the stage of genotyping or sequencing prioritization due to uncertainties of clinical precision and the need to conserve cost, which tend to be high for genetic studies. Additional exclusion criteria, such as diabetes mellitus, but also the decision to exclude enrollment for patients with prior foot surgery, further reduces the number of available cases by nearly 30%. How surgical procedures on the feet of CMT patients affects outcomes is complicated. While some experts argue that surgery has an effect on the MRC scale for foot dorsiflexion strength, specifically in cases of ankle arthrodesis, studies have shown that foot surgery does not have an effect on the CMTES and CMTPedS foot dorsiflexion (Laura, et al., 2018; Lin, et al., 2019; Ramdharry, et al., 2021; Tejero, et al., 2021). Because we wish to enrich the differences in mild and severe phenotypes from genetic modifiers, not environmentally acquired changes, we chose to exclude patients who had prior foot surgery.

We have already performed a GWAS-based analysis of CMT1A and have identified at least one strong candidate: SIPA1L2 was associated with foot dorsiflexion strength (maximum OR=12.794) (Tao, et al., 2019a; Tao, et al., 2019b). However, we suggest that our definition of mild and severe phenotypic CMT1A is more comprehensive with the inclusion of age-adjusted severity, using CMTES in addition to foot dorsiflexion strength, and with a larger expected cohort. Furthermore, given that we have these known candidates, we can do a separate test for association using a more relaxed significance threshold. By planning for a sequencing-based study (short- or long-read genome sequencing), we will also have the opportunity to look for more functional variation, rare changes, as well as structural variation. It is possible that subgroups of extreme CMT1A phenotypes are caused by different mechanisms, such as oligogenic burden, risk genes, and gene-environmental interactions.

We estimate that about 2,000–3,000 CMT1A patients have to be evaluated at participating centers in order to enroll ~400 participants in the extreme upper and lower 10th percentiles. The final future cohort will thus include patients from multiple countries and continents, which will enrich the study cohort for a broader ancestry spectrum, as well as include numerous clinicians from different centers with well-established protocols to help overcome examiner bias.

In summary, we have analyzed thousands of CMT1A patients and established a framework to quickly categorize mildly and severely affected patients in a clinical research setting. This is the first time that mild and severe phenotypes for CMT1A have been quantified with statistical support. This will focus valuable clinical research resources on enrolling the 10th and 90th percentile for severity. Due to CMT1A being a progressive disease, adjustment of clinical measures for age is important and can be achieved by creating five age-bins. We are working with the INC and multiple other clinicians, who are interested contributing to enlarging this modifier genetic cohort. The presented study concept is also an invitation to other neuromuscular experts to explore with us their potential contributions. A strong CMT1A modifying genetic locus will likely be explored for therapeutic target development for CMT1A and potentially related demyelinating forms of peripheral neuropathies.

Acknowledgments

We thank the patients for participating in this study. This work would not have been possible without the timeless efforts of many clinicians and study nurses at the different RDCRN-INC centers.

Funding

This work has been funded by NIH (5U54NS065712 to M.S. and 5R01NS105755 to S.Z.), Muscular Dystrophy Association, and CMT Association. MFD received a DFG scholarship (DO 2386/1-1). Vera Fridman is supported by NIH Mentored K23 Patient-Oriented Research Career Development Award - National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Grant number: 1K23DK118202-01A1.

JB is supported by a Senior Clinical Researcher mandate of the Research Fund - Flanders (FWO) under grant agreement number 1805021N. Several authors of this publication are member of the European Reference Network for Rare Neuromuscular Diseases (ERN EURO-NMD) and of the European Reference Network for Rare Neurological Diseases (ERN-RND). JB is is a member of the μNEURO Research Centre of Excellence of the University of Antwerp.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Data Availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

References

- Adlkofer K, Martini R, Aguzzi A, Zielasek J, Toyka KV, Suter U (1995). Hypermyelination and demyelinating peripheral neuropathy in Pmp22-deficient mice. Nat Genet 11:274–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amanat S, Requena T, Lopez-Escamez JA (2020). A Systematic Review of Extreme Phenotype Strategies to Search for Rare Variants in Genetic Studies of Complex Disorders. Genes (Basel) 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attarian S, Young P, Brannagan TH, Adams D, Van Damme P, Thomas FP, Casanovas C, Tard C, Walter MC, Pereon Y, Walk D, Stino A, de Visser M, Verhamme C, Amato A, Carter G, Magy L, Statland JM, Felice K (2021). A double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized trial of PXT3003 for the treatment of Charcot-Marie-Tooth type 1A. Orphanet journal of rare diseases 16:433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird TD (1993). Charcot-Marie-Tooth Hereditary Neuropathy Overview. In: GeneReviews((R)). Adam MP, Mirzaa GM, Pagon RA, Wallace SE, Bean LJH, Gripp KW, Amemiya A (Eds), Seattle (WA). [Google Scholar]

- Birouk N, Gouider R, Le Guern E, Gugenheim M, Tardieu S, Maisonobe T, Le Forestier N, Agid Y, Brice A, Bouche P (1997). Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 1A with 17p11.2 duplication. Clinical and electrophysiological phenotype study and factors influencing disease severity in 119 cases. Brain 120 (Pt 5):813–823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bland JM, Altman DG (1995). Multiple significance tests: the Bonferroni method. BMJ 310:170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braathen GJ (2012). Genetic epidemiology of Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. Acta Neurol Scand Suppl:iv–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns J, Menezes M, Finkel RS, Estilow T, Moroni I, Pagliano E, Laura M, Muntoni F, Herrmann DN, Eichinger K, Shy R, Pareyson D, Reilly MM, Shy ME (2013). Transitioning outcome measures: relationship between the CMTPedS and CMTNSv2 in children, adolescents, and young adults with Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. J Peripher Nerv Syst 18:177–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns J, Ouvrier R, Estilow T, Shy R, Laura M, Pallant JF, Lek M, Muntoni F, Reilly MM, Pareyson D, Acsadi G, Shy ME, Finkel RS (2012). Validation of the Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease pediatric scale as an outcome measure of disability. Ann Neurol 71:642–652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornett KMD, Menezes MP, Shy RR, Moroni I, Pagliano E, Pareyson D, Estilow T, Yum SW, Bhandari T, Muntoni F, Laura M, Reilly MM, Finkel RS, Eichinger KJ, Herrmann DN, Bray P, Halaki M, Shy ME, Burns J, Group CS (2017). Natural history of Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease during childhood. Ann Neurol 82:353–359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyck PJ, Lambert EH (1968). Lower Motor and Primary Sensory Neuron Diseases with Peroneal Muscular Atrophy .2. Neurologic Genetic and Electrophysiologic Findings in Various Neuronal Degenerations. Archives of Neurology 18:619-&. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fledrich R, Stassart RM, Klink A, Rasch LM, Prukop T, Haag L, Czesnik D, Kungl T, Abdelaal TA, Keric N, Stadelmann C, Bruck W, Nave KA, Sereda MW (2014). Soluble neuregulin-1 modulates disease pathogenesis in rodent models of Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease 1A. Nat Med 20:1055–1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fridman V, Bundy B, Reilly MM, Pareyson D, Bacon C, Burns J, Day J, Feely S, Finkel RS, Grider T, Kirk CA, Herrmann DN, Laura M, Li J, Lloyd T, Sumner CJ, Muntoni F, Piscosquito G, Ramchandren S, Shy R, Siskind CE, Yum SW, Moroni I, Pagliano E, Zuchner S, Scherer SS, Shy ME, Inherited Neuropathies C (2015). CMT subtypes and disease burden in patients enrolled in the Inherited Neuropathies Consortium natural history study: a cross-sectional analysis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 86:873–878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fridman V, Sillau S, Acsadi G, Bacon C, Dooley K, Burns J, Day J, Feely S, Finkel RS, Grider T, Gutmann L, Herrmann DN, Kirk CA, Knause SA, Laura M, Lewis RA, Li J, Lloyd TE, Moroni I, Muntoni F, Pagliano E, Pisciotta C, Piscosquito G, Ramchandren S, Saporta M, Sadjadi R, Shy RR, Siskind CE, Sumner CJ, Walk D, Wilcox J, Yum SW, Zuchner S, Scherer SS, Pareyson D, Reilly MM, Shy ME, Inherited Neuropathies Consortium-Rare Diseases Clinical Research N (2020). A longitudinal study of CMT1A using Rasch analysis based CMT neuropathy and examination scores. Neurology 94:e884–e896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao X, Starmer J, Martin ER (2008). A multiple testing correction method for genetic association studies using correlated single nucleotide polymorphisms. Genet Epidemiol 32:361–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George CM, Timothy JH, Abigail LDT, Isaac X, Stephan Z, Robert WB (2023). Testing SIPA1L2 as a modifier of CMT1A using mouse models. bioRxiv:2023.2011.2030.569428. [Google Scholar]

- Kanwal S, Choi BO, Kim SB, Koo H, Kim JY, Hyun YS, Lee HJ, Chung KW (2011). Wide phenotypic variations in Charcot-Marie-Tooth 1A neuropathy with rare copy number variations on 17p12. Anim Cells Syst 15:301–309. [Google Scholar]

- Karadima G, Floroskufi P, Koutsis G, Vassilopoulos D, Panas M (2011). Mutational analysis of PMP22, GJB1 and MPZ in Greek Charcot-Marie-Tooth type 1 neuropathy patients. Clin Genet 80:497–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YH, Chung HK, Park KD, Choi KG, Kim SM, Sunwoo IN, Choi YC, Lim JG, Lee KW, Kim KK, Lee DK, Joo IS, Kwon KH, Gwon SB, Park JH, Kim DS, Kim SH, Kim WK, Suh BC, Kim SB, Kim NH, Sohn EH, Kim OJ, Kim HS, Cho JH, Kang SY, Park CI, Oh J, Shin JH, Chung KW, Choi BO (2012). Comparison between clinical disabilities and electrophysiological values in Charcot-Marie-Tooth 1A patients with PMP22 duplication. Journal of clinical neurology 8:139–145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitani-Morii F, Noto YI, Tsuji Y, Shiga K, Mizuta I, Nakagawa M, Mizuno T (2020). Rate of Changes in CMT Neuropathy and Examination Scores in Japanese Adult CMT1A Patients. Front Neurol 11:626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krajewski KM, Lewis RA, Fuerst DR, Turansky C, Hinderer SR, Garbern J, Kamholz J, Shy ME (2000). Neurological dysfunction and axonal degeneration in Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 1A. Brain 123 (Pt 7):1516–1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamar KM, McNally EM (2014). Genetic Modifiers for Neuromuscular Diseases. J Neuromuscul Dis 1:3–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laura M, Singh D, Ramdharry G, Morrow J, Skorupinska M, Pareyson D, Burns J, Lewis RA, Scherer SS, Herrmann DN, Cullen N, Bradish C, Gaiani L, Martinelli N, Gibbons P, Pfeffer G, Phisitkul P, Wapner K, Sanders J, Flemister S, Shy ME, Reilly MM, Inherited Neuropathies C (2018). Prevalence and orthopedic management of foot and ankle deformities in Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. Muscle Nerve 57:255–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee AJ, Nam DE, Choi YJ, Noh SW, Nam SH, Lee HJ, Kim SJ, Song GJ, Choi BO, Chung KW (2020). Paternal gender specificity and mild phenotypes in Charcot-Marie-Tooth type 1A patients with de novo 17p12 rearrangements. Mol Genet Genomic Med 8:e1380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Parker B, Martyn C, Natarajan C, Guo JS (2013). The PMP22 Gene and Its Related Diseases. Mol Neurobiol 47:673–698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li T, Mizrahi D, Goldstein D, Kiernan MC, Park SB (2021). Chemotherapy and peripheral neuropathy. Neurol Sci 42:4109–4121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin T, Gibbons P, Mudge AJ, Cornett KMD, Menezes MP, Burns J (2019). Surgical outcomes of cavovarus foot deformity in children with Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. Neuromuscul Disord 29:427–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupski JR, de Oca-Luna RM, Slaugenhaupt S, Pentao L, Guzzetta V, Trask BJ, Saucedo-Cardenas O, Barker DF, Killian JM, Garcia CA, Chakravarti A, Patel PI (1991). DNA duplication associated with Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 1A. Cell 66:219–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsunami N, Smith B, Ballard L, Lensch MW, Robertson M, Albertsen H, Hanemann CO, Muller HW, Bird TD, White R, et al. (1992). Peripheral myelin protein-22 gene maps in the duplication in chromosome 17p11.2 associated with Charcot-Marie-Tooth 1A. Nat Genet 1:176–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morena J, Gupta A, Hoyle JC (2019). Charcot-Marie-Tooth: From Molecules to Therapy. Int J Mol Sci 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mroczek M, Sanchez MG (2020). Genetic modifiers and phenotypic variability in neuromuscular disorders. J Appl Genet 61:547–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy SM, Herrmann DN, McDermott MP, Scherer SS, Shy ME, Reilly MM, Pareyson D (2011). Reliability of the CMT neuropathy score (second version) in Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. J Peripher Nerv Syst 16:191–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagappa MSS, Taly AB (2022). Charcot Marie Tooth. StatPearls [Internet] Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-. [Google Scholar]

- Nam SH, Kanwal S, Nam DE, Lee MH, Kang TH, Jung SC, Choi BO, Chung KW (2018). Association of miR-149 polymorphism with onset age and severity in Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 1A. Neuromuscul Disord 28:502–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelis E, Van Broeckhoven C, De Jonghe P, Lofgren A, Vandenberghe A, Latour P, Le Guern E, Brice A, Mostacciuolo ML, Schiavon F, Palau F, Bort S, Upadhyaya M, Rocchi M, Archidiacono N, Mandich P, Bellone E, Silander K, Savontaus ML, Navon R, Goldberg-Stern H, Estivill X, Volpini V, Friedl W, Gal A, et al. (1996). Estimation of the mutation frequencies in Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 1 and hereditary neuropathy with liability to pressure palsies: a European collaborative study. Eur J Hum Genet 4:25–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantera H, Shy ME, Svaren J (2020). Regulating PMP22 expression as a dosage sensitive neuropathy gene. Brain Res 1726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pe’er I, Yelensky R, Altshuler D, Daly MJ (2008). Estimation of the multiple testing burden for genomewide association studies of nearly all common variants. Genet Epidemiol 32:381–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prukop T, Wernick S, Boussicault L, Ewers D, Jager K, Adam J, Winter L, Quintes S, Linhoff L, Barrantes-Freer A, Bartl M, Czesnik D, Zschuntzsch J, Schmidt J, Primas G, Laffaire J, Rinaudo P, Brureau A, Nabirotchkin S, Schwab MH, Nave KA, Hajj R, Cohen D, Sereda MW (2020). Synergistic PXT3003 therapy uncouples neuromuscular function from dysmyelination in male Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 1A (CMT1A) rats. J Neurosci Res 98:1933–1952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raeymaekers P, Timmerman V, Nelis E, De Jonghe P, Hoogendijk JE, Baas F, Barker DF, Martin JJ, De Visser M, Bolhuis PA, et al. (1991). Duplication in chromosome 17p11.2 in Charcot-Marie-Tooth neuropathy type 1a (CMT 1a). The HMSN Collaborative Research Group. Neuromuscul Disord 1:93–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramdharry G, Singh D, Gray J, Kozyra D, Skorupinska M, Reilly MM, Laura M (2021). A prospective study on surgical management of foot deformities in Charcot Marie tooth disease. J Peripher Nerv Syst 26:187–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risch NM, KR (1996). The Future of Genetic Studies of Complex Human Diseases. Science Vol 273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossor AM, Polke JM, Houlden H, Reilly MM (2013). Clinical implications of genetic advances in Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. Nat Rev Neurol 9:562–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Secchin JB, Leal RCC, Lourenco CM, Marques VD, Nogueira PTL, Santos ACJ, Tomaselli PJ, Marques W Jr. (2020). High glucose level as a modifier factor in CMT1A patients. J Peripher Nerv Syst 25:132–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheth S, Francies K, Siskind CE, Feely SM, Lewis RA, Shy ME (2008). Diabetes mellitus exacerbates motor and sensory impairment in CMT1A. J Peripher Nerv Syst 13:299–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinkiewicz-Darol E, Lacerda AF, Kostera-Pruszczyk A, Potulska-Chromik A, Sokolowska B, Kabzinska D, Brunetti CR, Hausmanowa-Petrusewicz I, Kochanski A (2015). The LITAF/SIMPLE I92V sequence variant results in an earlier age of onset of CMT1A/HNPP diseases. Neurogenetics 16:27–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skre H (1974). Genetic and clinical aspects of Charcot-Marie-Tooth’s disease. Clin Genet 6:98–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stavrou M, Kagiava A, Choudury SG, Jennings MJ, Wallace LM, Fowler AM, Heslegrave A, Richter J, Tryfonos C, Christodoulou C, Zetterberg H, Horvath R, Harper SQ, Kleopa KA (2022). A translatable RNAi-driven gene therapy silences PMP22/Pmp22 genes and improves neuropathy in CMT1A mice. J Clin Invest 132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stavrou M, Sargiannidou I, Georgiou E, Kagiava A, Kleopa KA (2021). Emerging Therapies for Charcot-Marie-Tooth Inherited Neuropathies. Int J Mol Sci 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suh JG, Ichihara N, Saigoh K, Nakabayashi O, Yamanishi T, Tanaka K, Wada K, Kikuchi T (1997). An in-frame deletion in peripheral myelin protein-22 gene causes hypomyelination and cell death of the Schwann cells in the new Trembler mutant mice. Neuroscience 79:735–744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao F, Beecham GW, Rebelo AP, Blanton SH, Moran JJ, Lopez-Anido C, Svaren J, Abreu L, Rizzo D, Kirk CA, Wu X, Feely S, Verhamme C, Saporta MA, Herrmann DN, Day JW, Sumner CJ, Lloyd TE, Li J, Yum SW, Taroni F, Baas F, Choi BO, Pareyson D, Scherer SS, Reilly MM, Shy ME, Zuchner S, Inherited Neuropathy C (2019a). Modifier Gene Candidates in Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease Type 1A: A Case-Only Genome-Wide Association Study. J Neuromuscul Dis 6:201–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao F, Beecham GW, Rebelo AP, Svaren J, Blanton SH, Moran JJ, Lopez-Anido C, Morrow JM, Abreu L, Rizzo D, Kirk CA, Wu X, Feely S, Verhamme C, Saporta MA, Herrmann DN, Day JW, Sumner CJ, Lloyd TE, Li J, Yum SW, Taroni F, Baas F, Choi BO, Pareyson D, Scherer SS, Reilly MM, Shy ME, Zuchner S, Inherited Neuropathy C (2019b). Variation in SIPA1L2 is correlated with phenotype modification in Charcot- Marie- Tooth disease type 1A. Ann Neurol 85:316–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tejero S, Chans-Veres J, Carranza-Bencano A, Galhoum AE, Poggio D, Valderrabano V, Herrera-Perez M (2021). Functional results and quality of life after joint preserving or sacrificing surgery in Charcot-Marie-Tooth foot deformities. Int Orthop 45:2569–2578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu C, Tachmazidou I, Walter K, Ciampi A, Zeggini E, Greenwood CM, Consortium UK (2014). Estimating genome-wide significance for whole-genome sequencing studies. Genet Epidemiol 38:281–290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F, Seeman P, Liu P, Weterman MA, Gonzaga-Jauregui C, Towne CF, Batish SD, De Vriendt E, De Jonghe P, Rautenstrauss B, Krause KH, Khajavi M, Posadka J, Vandenberghe A, Palau F, Van Maldergem L, Baas F, Timmerman V, Lupski JR (2010). Mechanisms for nonrecurrent genomic rearrangements associated with CMT1A or HNPP: rare CNVs as a cause for missing heritability. Am J Hum Genet 86:892–903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.