Abstract

In response to the growing global burden of fungal infections with uncertain impact, the World Health Organization (WHO) established an Expert Group to identify priority fungal pathogens and establish the WHO Fungal Priority Pathogens List for future research. This systematic review aimed to evaluate the features and global impact of invasive candidiasis caused by Candida tropicalis. PubMed and Web of Science were searched for studies reporting on criteria of mortality, morbidity (defined as hospitalization and disability), drug resistance, preventability, yearly incidence, diagnostics, treatability, and distribution/emergence from 2011 to 2021. Thirty studies, encompassing 436 patients from 25 countries were included in the analysis. All-cause mortality due to invasive C. tropicalis infections was 55%–60%. Resistance rates to fluconazole, itraconazole, voriconazole and posaconazole up to 40%–80% were observed but C. tropicalis isolates showed low resistance rates to the echinocandins (0%–1%), amphotericin B (0%), and flucytosine (0%–4%). Leukaemia (odds ratio (OR) = 4.77) and chronic lung disease (OR = 2.62) were identified as risk factors for invasive infections. Incidence rates highlight the geographic variability and provide valuable context for understanding the global burden of C. tropicalis infections. C. tropicalis candidiasis is associated with high mortality rates and high rates of resistance to triazoles. To address this emerging threat, concerted efforts are needed to develop novel antifungal agents and therapeutic approaches tailored to C. tropicalis infections. Global surveillance studies could better inform the annual incidence rates, distribution and trends and allow informed evaluation of the global impact of C. tropicalis infections.

Keywords: Candida tropicalis, candidaemia, invasive fungal infection, global epidemiology, mortality

Introduction

Candida tropicalis is important as a cause of invasive candidiasis with high mortality.1–5 Whilst the 30-day mortality of candidaemia lingers unchanged at 30%–40%,6–9 that of C. tropicalis bloodstream infections has been reported to be as high as 52%.10 This heightened mortality emphasizes the critical need for a deeper understanding of the factors contributing to the virulence of C. tropicalis and the development of effective treatment strategies. The proportion of Candida bloodstream infections caused by C. tropicalis waspreviously surpassed by C. albicans, Nakaseomyces glabratus (previously C. glabrata complex) and/or C. parapsilosis complex,6,11,12 however, in Southeast Asia and South America it has overtaken and has been reported as the first or second most important cause of Candida bloodstream infections.13,14

The shift in the epidemiology of infections from C. albicans to non-albicans Candida and other yeast spp., including C. tropicalis, has been associated with increasing resistance to antifungal agents.1,15,16 This phenomenon underscores the urgency of monitoring and addressing antifungal resistance, particularly in the context of C. tropicalis infections. Notably, an Australian report described an increase in resistance from rare, <2%, to 16.7% a decade later.16,17 Thus, data focusing on C. tropicalis and its differentiation from other Candida spp. are important.

As part of the WHO development of the first FPPL, this systematic review aimed to evaluate the features and global impact of invasive candidiasis caused by C. tropicalis. The criteria for evaluation included mortality, hospitalisation and disability, antifungal drug resistance, preventability, yearly incidence, global distribution, and emergence in the last 10 years. Identified knowledge gaps for C. tropicalis were highlighted for further research. By addressing these gaps, this review contributes to a more comprehensive understanding of the clinical and epidemiological aspects of C. tropicalis infections, thus informing strategies for its management and control.

Materials and Methods

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) statement.18 Adherence to PRISMA guidelines enhances the transparency and reproducibility of this review's methodology. PubMed and Web of Science databases were used. Eligibility criteria for studies were any population including adults and children, reports with specific data on Candida tropicalis infection or of isolates, observational studies, randomised controlled trials, guidelines, epidemiology, or surveillance reports and, publication between 1 January 2011 and 19 February 2021.

Reports were eligible if they included data on at least one of the prespecified criteria being mortality, hospitalisation and disability, antifungal drug resistance, preventability, yearly incidence, global distribution, and emergence over the last 10 years. Studies reporting on non-human data including animals and plants, studies not reporting on C. tropicalis, studies with no data on the prespecified criteria above, case reports, conference abstracts and reviews, reports on novel antifungal agents in pre-clinical, early phase trials or not licenced, in vitro papers on resistance mechanisms and papers not written in English were excluded.

Search strategy

On PubMed, the search was optimized using the medical subject headings (MeSH) with keyword terms in the title or abstract for each criterion (not case sensitive). The final search used (Candida tropicalis[MeSH Terms]) combined, using AND term, with criteria terms including (mortality[MeSH Terms]) OR (morbidity[MeSH Terms]) OR (hospitalisation[MeSH Terms]) OR (disability[All Fields])) OR (drug resistance, fungal[MeSH Terms]) OR (prevention and control[MeSH Subheading]) OR (disease transmission, infectious[MeSH Terms]) OR (diagnostic[Title/Abstract]) OR (antifungal agents[MeSH Terms]) OR (epidemiology[MeSH Terms]) OR (surveillance [Title/Abstract]).

On Web of Science, MeSH terms are not available and therefore topic search (TS), title (TI) or abstract (AB) search was used. The final search used [TI=(‘Candida tropicalis’) OR TI=(‘C. tropicalis’)], combined, using AND term, with criteria terms each as topic search, including (mortality) OR (case fatality) OR (morbidity) OR (hospitali*ation) OR (disability) OR (drug resistance) OR (prevention and control) OR (disease transmission) OR (diagnostic) OR (antifungal agents) OR (epidemiology) OR (surveillance). Symbol * allows a truncation search for variations of the term (e.g., hospitalisation or hospitalization). All articles from each database were imported into a reference manager, Endnote®.

Study selection

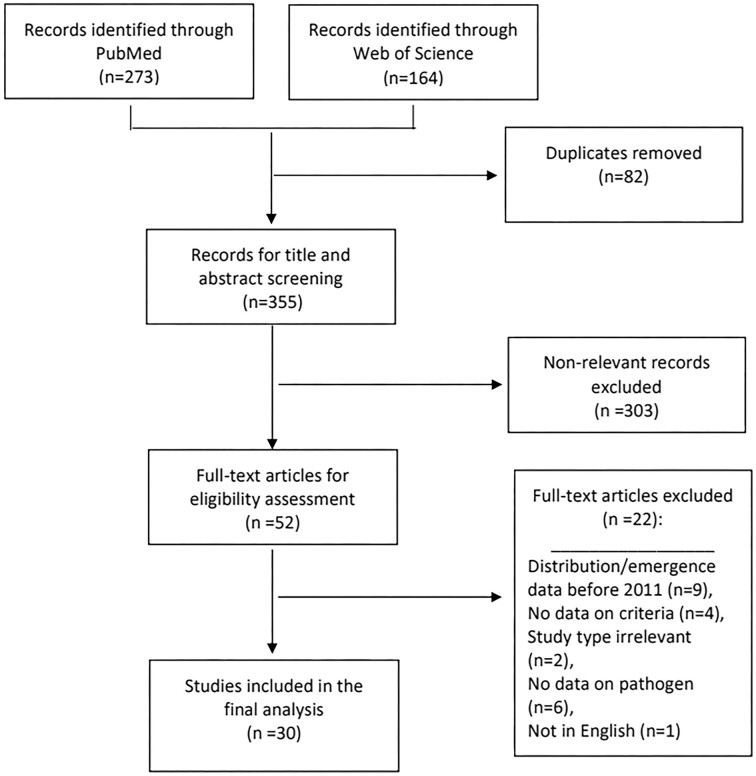

The final search results from each database were incorporated into the online systematic review software, Covidence® (Veritas Health Innovation, Sydney, Australia). Duplicates were removed in Covidence®. The remaining articles underwent title and abstract screening based on the inclusion criteria. No reason was provided for article exclusion during title and abstract screening. Full-text screening was performed for the final set of eligible articles; excluded articles were recorded with reasons. All of the title, abstract and full-text screenings were performed independently by two reviewers (HK, CK) using Covidence®. Discrepancies were resolved by a third reviewer (JWA). Additional articles identified from the references of the included articles were added and screened. The resulting articles were subject to the final analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram for selection of studies included in the systematic review. Based on: Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement.57

Data collection

Data from the final list of included studies were extracted for the relevant criteria. The extracted data was checked by the second reviewer (20% check).

Risk of bias assessment

Risk of bias assessment was performed for the included studies on relevant bias criteria, depending on the type of data extracted. Risk of bias tool for randomized trials version 2 (ROB 2) tool was used to assess the randomised controlled trials.19 The risk of bias in non-randomized studies (RoBANS) tool was used to assess the non-randomised studies.20 For the overall risk, using the ROB 2 tool, the studies were rated as low, high risk or some concerns. Using the RoBANS tool, the studies were rated as having low, high, or unclear risk.

As the systematic review was intended to inform on specific criteria rather than study outcomes as in traditional systematic reviews, the bias assessment tools were not perfectly suited for the task to assess the bias for the specific criteria. We used each criterion as an outcome of the study and assessed if any bias was expected based on the study design, data collection or analysis in that particular study. Following that strategy, studies classified as unclear or high overall risk were still considered for analysis.

Data extraction

The extracted data on the outcome criteria were quantitatively or qualitatively synthesised depending on the amount and nature of the data.

Results

Study selection

PubMed and Web of Science Core Collection databases searched between 1 January 2011 and 19 February 2021 yielded 273 and 164 articles, respectively. Duplicates were removed and the remaining, 355 articles underwent title/abstract screening. After excluding non-relevant articles, 52 articles underwent full-text screening. After excluding articles based on the full-text review, 30 studies were included in the final analysis, including 436 patients from 25 countries. A flow diagram outlining the process of study selection is shown in Figure 1.

Risk of bias

Overall risk of bias for each study is presented in Table 1. Of the included studies, 14 were classified as having a low risk of bias in all the domains assessed. Nine studies were classified as unclear risk of bias, mostly due to the potential selection biases caused by unclear eligibility criteria or population groups, or unclear confirmation/consideration of confounding variables. Seven studies were classified as high risk, because of the selection bias due to inadequate considerations in the selection of patients or eligibility criteria.

Table 1.

Risk of bias

| Author | Publication year | Risk (low, high, unclear) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Al-obaid et al. | 2017 | High | 58 |

| Arastehfar, Daneshnia, et al. | 2020 | Low | 1 |

| Arastehfar et al. | 2020 | Low | 21 |

| You et al. | 2020 | Unclear | 23 |

| Zhou et al. | 2019 | High | 59 |

| Castanheira et al. | 2020 | Low | 26 |

| Chapman et al. | 2017 | Low | 16 |

| Chen et al. | 2019 | Low | 31 |

| Eliakim-Raz et al. | 2016 | Unclear | 60 |

| Fan et al. | 2017 | High | 32 |

| Fernández-Ruiz et al. | 2015 | Low | 11 |

| Guinea et al. | 2014 | Unclear | – - |

| Guo et al. | 2017 | High | 39 |

| Jordan et al. | 2014 | High | 24 |

| Kang et al. | 2017 | Low | 22 |

| Karadag-Oncel et al. | 2015 | Low | 25 |

| Katsuragi et al. | 2014 | Low | 35 |

| Khadka et al. | 2017 | Low | 33 |

| Ko et al. | 2019 | Unclear | 2 |

| Liu et al. | 2019 | Unclear | 10 |

| Medeiros et al. | 2019 | Low | 27 |

| Megri et al. | 2020 | Unclear | 4 |

| Siopi et al. | 2020 | Low | 28 |

| Tang et al. | 2014 | Low | 40 |

| Tasneem et al. | 2017 | Unclear | 29 |

| Toda et al. | 2019 | Low | 34 |

| Wang et al. | 2020 | Unclear | 36 |

| Wang et al. | 2020 | Unclear | 37 |

| Wang et al. | 2016 | High | 61 |

| Xiao et al. | 2015 | Low | 30 |

| Yfsudhason et al. | 2015 | High | 38 |

Deaths

Mortality data are summarized in Table 2. Overall mortality due to C. tropicalis candidaemia was as high as 55%–60% (105/186).1,21 Five studies reported on the 30-day mortality rates in C. tropicalis candidaemia patients ranging from 32% to 52%.2,10,11,22,23 Overall mortality rates in paediatric patients with invasive C. tropicalis infections were 26%–40%.24,25

Table 2.

Mortality

| Author | Year | Study design | Study period | Country | Level of care | Population description | Number of patients | Mortality type | N/N, % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arastehfar, Daneshnia, et al. 1 | 2020 | Retrospective cohort study | Multi-centre | 09/2014–02/2019 | Iran | Not stated | Patients with candidaemia | 62 | Overall mortality | 37/62, 59.6% |

| Arastehfar et al. 21 | 2020 | Retrospective cohort study | Multi-centre | 2010–2019 (variable per site) | Turkey | Tertiary | Patients with candidaemia | 127 | Overall mortality | 68/124, 54.8% |

| You et al. 23 | 2020 | Retrospective cohort study | Multi-centre | 01/2011–12/2018 | China | Tertiary | Haematology patients with candidaemia | 90 | 30-day mortality | 30-day mortality: 30/90, 33.3% 8-day mortality: 20/90, 22.2% |

| Fernández-Ruiz et al. 11 | 2015 | Retrospective cohort study | Multi-centre | 05/2010–04/2011 | Spain | Tertiary | Patients with candidaemia | 59 | 30-day mortality | 18/56, 32% |

| Jordan et al. 24 | 2014 | Retrospective cohort study | Multi-centre | 01/2008–12/2009 | Spain | Tertiary | Paediatric intensive care patients with invasive candidiasis | 19 | Overall mortality | 5/19, 26.30% |

| Kang et al. 22 | 2017 | Retrospective cohort study | Multi-centre | 2007–2014 | Korea | Tertiary | Patients with candidaemia | 46 | 30-day mortality | 18/44, 34% |

| Karadag-Oncel et al. 25 | 2015 | Retrospective cohort study | Single centre | 01/2004–12/2012 | Turkey | Tertiary | Candidaemic children; febrile neutropaenic patients and premature infants excluded | 20 | 30-day mortality | 8/20, 40% |

| Ko et al. 2 | 2019 | Retrospective cohort study | Multi-centre | 01/2010–02/2016 | Korea | Tertiary | >16 years old with non-albicans candidaemia | 263 | 30-day mortality | 116/163, 44.1% |

| Liu et al. 10 | 2019 | Retrospective cohort study | Multi-centre | 07/2011–06/2014 | Taiwan | Tertiary | Adults aged > 20 years with candidaemia | 248 | 30-day mortality | 129/248, 52% |

| Medeiros et al. 27 | 2019 | Retrospective cohort study | Single centre | 01/2011–12/2016 | Brazil | Tertiary | All patients | 14 | 30-day mortality | 6/14, 42% |

| Megri et al. 4 | 2020 | Retrospective cohort study | Multi-centre | 2016–2019 | Algeria | Tertiary | All patients | 16 | In-hospital | 13/16, 82% |

| Tang et al. 40 | 2014 | Retrospective cohort study | Single centre | 2009–2012 | Taiwan | Tertiary | Adult patients with cancer | 52 | In-hospital | 25/52, 48% |

Inpatient care

Hospital length of stay due to C. tropicalis could not be assessed due to a lack of data from the included studies.

Complications and sequelae

Disability due to C. tropicalis could not be assessed due to a lack of data from the included studies.

Antifungal resistance

In total, 25 studies reported on the drug susceptibility or resistance rates of C. tropicalis. Details of these studies are presented in Table 3. Drug susceptibility to azoles and other antifungal drugs are presented in Tables 4 and 5, respectively.

Table 3.

Studies reporting drug susceptibility/resistance

| Author | Year | Study design | Study period | Country | Level of care | Population description | Number of patients | Number of isolates | Samples collected from | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al-obaid et al. 58 | 2017 | Retrospective cohort study | Single centre | 03/2015–10/2015 | Kuwait | Tertiary | All patients | 54 | 63 | Blood, genito-urinary, respiratory and digestive tracts and wounds |

| Arastehfar, Daneshnia, et al. 1 | 2020 | Retrospective cohort study | Multi-centre | 09/2014–02/2019 | Iran | Not stated | Patients with candidaemia | 62 | 64 | Blood |

| Arastehfar et al. 21 | 2020 | Retrospective cohort study | Multi-centre | 2010–2019 (variable per site) | Turkey | Tertiary | Patients with candidaemia | 127 | 161 | Blood |

| You et al. 23 | 2020 | Retrospective cohort study | Multi-centre | 01/2011–12/2018 | China | Tertiary | Haematology patients with candidaemia | 90 | 90 | Blood |

| Zhou et al. 59 | 2019 | Retrospective cohort study | Single centre | 01/2012–12/2017 | China | Tertiary | Adult burns intensive care patients with candidiasis | Uncertain | 68 | Blood (6), Other including wound, intravascular catheter, respiratory tract and urine (64) |

| Castanheira et al. 26 | 2020 | Prospective cohort study | Multi-centre | 01/2016–12/2017 | 25 countries | Tertiary | All patients | Uncertain | 227 | Blood, respiratory tract, wounds, urine and other |

| Chapman et al. 16 | 2017 | Prospective cohort study | Multi-centre | 2014–2015 | Australia | Mix | Patients with candidaemia | 24 | 24 | Blood |

| Chen et al. 31 | 2019 | Prospective cohort study | Single centre | 03/2011–12/2017 | Taiwan | Tertiary | Adult patients with candidaemia | 344 | 344 | Blood |

| Eliakim-Raz et al. 60 | 2016 | Retrospective cohort study | Single centre | 01/2007–12/2014 | Israel | Tertiary | Adult patients with candidaemia | 16 | 16 | Blood |

| Fan et al. 32 | 2017 | Retrospective cohort study | Multi-centre | 08/2009 and 07/2014 | China | Tertiary | Patients with invasive candidiasis | Uncertain | 507 | Blood (220), ascitic fluid (130), bronchoalveolar lavage (36), wounds (36), biliary fluid (27), other (65) |

| Fernández-Ruiz et al. 11 | 2015 | Retrospective cohort study | Multi-centre | 05/2010–04/2011 | Spain | Tertiary | Patients with candidaemia | 59 | 59 | Blood |

| Guinea et al. 48 | 2014 | Prospective cohort study | Multi-centre | 05/2010–04/2011 | Spain | Tertiary probably | Patients with candidaemia | Uncertain | 59 | Blood |

| Guo et al. 39 | 2017 | Prospective cohort study | Multi-centre | 01/2012–12/2013 | China | Tertiary | All patients with invasive candidiasis | Uncertain | 160 | 61 Blood, 41 ascitic fluid, 18 BAL 12 CVC tips, 6 pus, 8 bile, 9 pleural fluid, 4 CSF, 1 tissue |

| Katsuragi et al. 35 | 2014 | Retrospective cohort study | Single centre | 01/2007–12/2011 | Japan | Tertiary | All patients | 212 | 212 | Sputum (123), Urogenital (49), Stool (17), Intra-body materials (11), Blood (11), Others (1) |

| Khadka et al. 33 | 2017 | Retrospective cohort study | Single centre | 07/2014–01/2015 | Nepal | Tertiary | All patients | 20 | 20 | Urine (12), Sputum (8) |

| Liu et al. 10 | 2019 | Retrospective cohort study | Multi-centre | 07/2011–06/2014 | Taiwan | Tertiary | Adults aged > 20 years with candidaemia | 248 | 248 | Blood |

| Medeiros et al. 27 | 2019 | Retrospective cohort study | Single centre | 01/2011–12/2016 | Brazil | Tertiary | Patients with candidaemia | 12 | 12 | Blood |

| Megri et al. 4 | 2020 | Retrospective cohort study | Multi-centre | 2016–2019 | Algeria | Tertiary | All patients | 16 | 19 | Blood |

| Siopi et al. 28 | 2020 | Retrospective cohort study | Single centre | 2009–2018 | Greece | Tertiary | Patients with candidaemia | 31 | 31 | Blood |

| Tasneem et al. 29 | 2017 | Cross sectional study | Single centre | 01/2014–02/2015 | Pakistan | Tertiary | Patients with candida at any site | 26 | 26 | Urine (10), vaginal (6), sputum (4), tracheal lavage (3), pus (3) |

| Wang et al. 36 | 2020 | Retrospective cohort study | Single centre | 12/2018–11/2019 | China | Tertiary | Patients with C tropicalis urogenital infections | 64 | 64 | Urogenital |

| Wang et al. 37 | 2020 | Cross sectional study | Single centre | 12/2018–11/2019 | China | Tertiary | Patients with candida infection | 84 | 87 | Urine (43), vaginal swabs (22), blood (11), bile (4), sputum (4), catheter tips (2), ascites (1) |

| Xiao et al. 30 | 2015 | Prospective cohort study | Multi-centre | 08/2009–07/2012 | China | Tertiary | Patients with invasive candidiasis | Uncertain | 379 | Blood (148), ascitic fluid (100), central line catheter (12), pus (17), bronchoalveolar lavage (28), bile (28), pleural fluid (23), cerebrospinal fluid (13), tissue (9), peritoneal dialysate (1) |

| Yfsudhason et al. 38 | 2015 | Prospective cohort study | Single centre | 01/2013–12/2013 | India | Tertiary | Any isolates | Uncertain | 61 | urine (39), vaginal swabs (12), exudates (4), blood (6) |

| Toda 34 | 2019 | Retrospective cohort study | Multi-centre | 2012–2016 | USA | Tertiary | Patients with candidaemia | 52 | 52 | Blood |

Table 4.

Drug susceptibility to azoles

| Author | Number of isolates | MIC method | Fluconazole | Voriconazole | Posaconazole | Itraconazole | Isavuconazole |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al-obaid et al. 58 | 63 | Vitek 2 YST AST/CLSI BPs | R: 0, 0% Range: 1–1 MIC50: 1 MIC90: 1 |

R: 0, 0% Range: 0.12–0.12 MIC50: 0.12 MIC90: 0.12 |

Not done | Not done | Not done |

| Arastehfar, Daneshnia, et al. 1 | 64 | CLSI M27-A3 | R: 4, 6.25% a SDD: 7, 10.9% GM: 0.9 Range: 0.125–64 MIC50: 0.5 MIC90: 4 |

R: 7, 10.9% I: 18, 28.1% GM: 0.14 Range: 0.016–4 MIC50: 0.125 MIC90: 1 |

Not done | NWT: 2, 3.1% GM: 0.26 Range: 0.06–16 MIC50: 0.25 MIC90: 1 |

Not done |

| Arastehfar et al. 21 | 161 | CLSI M27-A3 | R: 15, 9.3% b SDD: 1, 0.6% |

R: 16, 9.9% I: 2, 1.2% |

NWT: 25, 15.5% | NWT: 20, 12.4% | NWT: 22, 13.7% |

| Zhou et al. 59 | 68 | CLSI M44-A2 | R or SDD: 34, 50% | R or I: 23, 33.3% | Not done | NWT: 34, 50% | Not done |

| Castanheira et al. 26 | 227 | CLSI M27-A3 | R: 6, 2.6% c SDD: 1, 0.4% |

R: 4, 1.8% I: 3, 1.3% |

NWT: 17, 7.5% | Not done | Not done |

| Chapman et al. 16 | 24 | Sensitititre YeastOne/CLSI BPs | R: 4, 16.7% SDD: 2, 8.3% GM: 2.6 Range: 0.5–256 MIC90: 64 |

R: 4, 16.7% I: 5, 19.3% GM: 0.2 Range: 0.008→8 MIC90: 3 |

NWT: 17, 71% GM: 0.18 Range: 0.0015–1 MIC90: 0.5 |

NWT: 17, 71% GM: 0.18 Range: 0.03–1 MIC90: 0.5 |

Not done |

| Chen et al. 31 | 344 | Sensititre YeastOne/CLSI BPs and EUCAST posaconazole BP | R: 48, 14% SDD: 10, 2.9% Range: 0.06–512 MIC50: 1 MIC90: 32 |

R or I: 75, 21.8% Range: 0.004–16 MIC50: 0.12 MIC90: 2 |

NWT: 285, 82.9% Range: 0.06–16 MIC50: 0.25 MIC90: 0.5 |

NWT: 20, 5.8% Range: 0.06–32 MIC50: 0.25 MIC90: 0.5 |

Not done |

| Fan et al. 32 | 585 | Sensititre YeastOne/CLSI BPs | R: 140, 12.8% SDD: 60, 10.3% GM: 2.59 MIC50: 2 MIC90: 32 |

R: 67, 11.4% I: 54, 9.3% GM: 0.13 MIC50: 0.12 MIC90: 1 |

NWT: 0, 0% GM: 0.17 MIC50: 0.12 MIC90: 0.5 |

NWT: 0, 0% GM: 0.21 MIC50: 0.25 MIC90: 0.5 |

Not done |

| Fernández-Ruiz et al. 11 | 56 | EUCAST broth microdilution | R: 13, 23.2% d GM: 1.83 MIC90: >64 |

R: 15, 26.8% GM: 0.13 MIC90: >8 |

R: 11, 19.6% GM: 0.047 MIC90: 8 |

Not done | Not done |

| Guinea et al. 48 | 59 | EUCAST and CLSI M27-A3 | EUCAST R: 13, 22% GM: 1.83 Range:  0.12– 0.12– 64 64MIC90: >64 CLSI R: 1, 1.7% SDD: 1, 1.7% GM: 0.71 Range: 0.12–8 MIC90: 1 |

EUCAST R: 15, 25.4% GM: 0.13 Range:  0.015– 0.015– 8 8MIC90: >8 CLSI R: 0, 0% I: 1, 1.7% GM: 0.026 Range: 0.003–0.25 MIC90: 0.06 |

EUCAST R: 11, 18.6% GM: 0.047 Range:  0.015– 0.015– 8 8MIC90: 8 CLSI R: 0, 0% GM: 0.023 Range: 0.0017–0.12 MIC90: 0.06 |

EUCAST GM: 0.057 Range:  0.015– 0.015– 8 8MIC90: 8 |

Not done |

| Guo et al. 39 | 160 | CLSI M27-A3 | R: 15, 9.4% e SDD: 13, 8.1% Range: 0.064–128 MIC50: 0.5 MIC90: 4 |

R: 15% I: 11, 6.9% Range: 0.016–8 MIC50: 0.032 MIC90: 0.25 |

Not done | NWT: 18, 11.2% Range: 0.032–32 MIC50: 0.25 MIC90: 1 |

Not done |

| Katsuragi et al. 35 | 11 | CLSI M27-A3 | R: 4, 36.4% Range: 1→64 MIC50: 8 MIC90: >64 |

R: 0, 0% Range: 0.13–0.5 MIC50: 0.25 MIC90: 0.5 |

Not done | NWT: 8, 72.7% Range: 0.25→8 MIC50: 4 MIC90: >8 |

Not done |

| Khadka et al. 33 | 20 | CLSI M44-A disk diffusion | R: 4, 20% SDD 4, 20% |

Not done | Not done | Not done | Not done |

| Liu et al. 10 | 248 | Sensititre YeastOne/CLSI BPs | R: 41, 16.5% f SDD 43, 17.3% f Range: 0.25→256 MIC50: 2 MIC90: 16 |

R: 32, 12.9% I: 109, 44% Range: 0.015–>8 MIC50: 0.25 MIC90: 1 |

NWT: 178, 71.8% Range: 0.015–2 MIC50: 0.25 MIC90: 0.5 |

NWT: 11, 4.4% Range: 0.06–1 MIC50: 0.25 MIC90: 0.5 |

Not done |

| Medeiros et al. 27 | 12 | CLSI M27-A3 | R: 0, 0% SDD: 2, 16.7% Range: 0.125–4.0 MIC50: 0.5 MIC90: 4.0 |

Not done | Not done | R: 0, 0% SDD: 1, 8.3% Range: <0.03–0.125 MIC50: 0.03 MIC90: 0.06 |

Not done |

| Megri et al. 4 | 19 | CLSI M27-A3 | R: 6, 31.6% | R: 9, 47.4% | Not done | NWT: 5, 26.3% | Not done |

| Siopi et al. 28 | 23 | Sensititre YeastOne/CLSI BPs | R: 0, 0% I: 1, 4% Range: 0.25–4 MIC50: 2 MIC90: 2 |

R: 0, 0% I: 1, 4% Range: 0.015–0.5 MIC50: 0.06 MIC90: 0.12 |

NWT: 0, 0% Range: 0.03–0.5 MIC50: 0.12 MIC90: 0.5 |

NWT: 0, 0% Range: 0.06–0.5 MIC50: 0.12 MIC90: 0.5 |

Not done |

| Tasneem et al. 29 | 26 | CLSI M44-A disk diffusion | R: 0, 0% | R: 2, 7.6% | Not done | Not done | Not done |

| Wang et al. 36 | 64 | CLSI M27-A4 | R: 27, 42% | R: 28, 43.7% | Not done | NWT: 29, 45.3% | Not done |

| Wang et al. 37 | 87 | CLSI M27-A4 | R: 36, 41.4% I, 2, 2.3% MIC50: 1 MIC90: >64 |

R: 36, 41.4% I: 12, 13.8% MIC50: 0.25 MIC90: 16 |

Not done | NWT: 36, 41.4% MIC50: 0.5 MIC90: 16 |

Not done |

| Xiao et al. 30 | 379 | Sensititre YeastOne/CLSI BPs | R: 31, 8.2% g SDD: 13, 3.4% GM: 1.9 Range: 0.25→256 |

R: 20, 5.3% I: 16, 4.2% GM: 0.08 Range: ≤0.008→8 |

NWT: 120, 31.7% GM: 0.13 Range: 0.008→8 |

NWT: 5, 98.7% GM: 0.18 Range: 0.015→16 NWT: 1.3% |

Not done |

| Yfsudhason et al. 38 | 61 | Disk Diffusion | R: 23, 37.7% | Not done | Not done | R: 16, 26.2% | Not done |

| Toda 34 | 52 | CLSI M27-A3 | R: 12, 4.2% h | R: 6, 2.1% | Not done | Not done | Not done |

Note: Studies with a high risk of bias excluded from this table. Susceptibility values are expressed as minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) in mg/L. BPs, breakpoints, GM, Geometric mean, MIC50, minimum inhibitory concentration of 50% of isolates, MIC90, minimum inhibitory concentration of 90% of isolates; S, susceptible; SDD, susceptible dose dependent; I, intermediate; R, resistant; WT, wildtype; NWT, non-wild type. a2 cross-resistant to voriconazole; b9 cross-resistant to voriconazole; c4 cross-resistant to voriconazole; dresistance to fluconazole lower (1.7%) with CLSI method; e9.3% resistant/NWT to more than 2 azoles; f80 were R or I to voriconazole; g1 isolate cross-resistant to voriconazole; hNo isolates cross-resistant. Data are given as provided in source documents.

Table 5.

Drug susceptibility to other antifungal drugs

| Author | Number of isolates | MIC method | Micafungin | Anidulafungin | Caspofungin | Amphotericin B | Flucytosine |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al-obaid et al. 58 | 63 | Vitek 2 YST AST/CLSI BPs | R: 0, 0% Range: 0.06–0.06 MIC50: 0.06 MIC90: 0.06 |

Not done | R: 0, 0% Range: 0.25–0.25 MIC50: 0.25 MIC90: 0.25 |

NWT: 0, 0% Range: 0.25–0.5 MIC50: 0.25 MIC90: 0.5 |

R: 1, 1.6% Range: 1.0–16 MIC50: 1 MIC90: 1 |

| Arastehfar, Daneshnia, et al. 1 | 64 | CLSI M27-A3 | R: 2, 3.1% GM: 0.05 Range: 0.008–1 MIC50: 0.06 MIC90: 0.25 |

R: 0, 0% GM: 0.04 Range: 0.008–0.5 MIC50: 0.025 MIC90: 0.125 |

Not done | NWT: 0, 0% GM 0.64 Range: 0.125–2 MIC50: 0.5 MIC90: 1 |

Not done |

| Arastehfar et al. 21 | 161 | CLSI M27-A3 | R: 0, 0% | R: 0, 0% | Not done | NWT: 0, 0% | Not done |

| Castanheira et al. 26 | 227 | CLSI M27-A3 | R: 2, 0.9% | R: 2, 0.9% | R: 2, 0.9% | NWT: 0, 0% | Not done |

| Chapman et al. 16 | 24 | Sensititre YeastOne/CLSI BPs | R: 0, 0% GM: 0.02 Range: <0.008–0.06 MIC90: 0.03 |

R: 0, 0% GM: 0.03 Range: <0.015–0.12 MIC90: 0.06 |

R: 0, 0% GM: 0.04 Range: 0.015–0.25 MIC90: 0.09 |

NWT: 0, 0% GM: 0.65 Range: <0.12–1 MIC90: 1 |

NWT: 1, 4% GM: 0.07 Range: <0.06–1 MIC90: 0.197 |

| Chen et al. 31 | 344 | Sensititre YeastOne/CLSI BPs | R: 2, 0.6% Range: 0.015–2 MIC50: 0.03 MIC90: 0.03 |

R: 2, 0.6% Range: 0.008–1 MIC50: 0.06 MIC90: 0.12 |

R: 3, 0.9% Range: 0.015–8 MIC50: 0.06 MIC90: 0.12 |

NWT: 0, 0% Range: 0.25–1 MIC50: 1 MIC90: 1 |

NWT: 4, 1.2% Range: 0.03–64 MIC50: 0.03 MIC90: 0.06 |

| Fan et al. 32 | 585 | Sensititre YeastOne/CLSI BPs | R: 2, 0.4% I: 0, 0% GM: 0.03 MIC50: 0.03 MIC90: 0.03 |

R: 2, 0.4% I: 2, 0.4% GM: 0.07 MIC50: 0.06 MIC90: 0.25 |

R: 2, 0.4% I: 0, 0% GM: 0.04 MIC50: 0.03 MIC90: 0.06 |

NWT: 0, 0% GM: 0.75 MIC50: 1 MIC90: 1 |

NWT: 3, 0.6% GM: 0.07 MIC50: 0.03 MIC90: 0.12 |

| Fernández-Ruiz et al. 11 | 56 | EUCAST broth microdilution | GM: 0.034 MIC90: 0.03 |

R: 2, 3.6% GM: 0.034 MIC90: 0.03 |

GM: 0.41 MIC90: 0.5 |

R: 0, 0% GM: 0.079 MIC90: 0.12 |

Not done |

| Guinea et al. 48 | 59 | EUCAST and CLSI M27-A3 | EUCAST GM: 0.034 MIC90: 0.03 Range: ≤0.03–2 CLSI R: 2, 3.4% GM: 0.021 MIC90: 0.06 Range: 0.03–1 |

EUCAST R: 2, 3.4% GM: 0.034 Range: ≤0.03–1 MIC90: 0.03 CLSI R: 2, 3.4% GM: 0.014 Range: 0.017–2 MIC90: 0.03 |

EUCAST GM: 0.41 Range:0.12–2 MIC90: 0.5 CLSI R: 0, 0% I: 1, 1.7% GM: 0.12 Range: 0.015–0.5 MIC90: 0.25 |

EUCAST GM: 0.079 Range: ≤0.03–0.5 MIC90: 0.12 CLSI GM: 0.22 Range: 0.03–1 MIC90: 0.5 |

EUCAST GM: 0.154 Range: ≤0.12–32 MIC90: 0.12 |

| Guo et al. 39 | 160 | CLSI M27-A3 | R: 0, 0% Range: 0.008–0.25 MIC50: 0.32 MIC90: 0.125 |

Not done | R: 0, 0% I: 9, 5.6% Range: 0.008-0.5 MIC50: 0.125 MIC90: 0.25 |

NWT: 0, 0% Range: 0.125–2 MIC50: 0.5 MIC90: 1 |

NWT: 0, 0% Range: 0.064–0.125 MIC50: 0.064 MIC90: 0.064 |

| Katsuragi et al. 35 | 11 | CLSI M27-A3 | Range: 0.06–2 MIC50: 0.06 MIC90: 0.13 |

Not done | Not done | Range: 0.13–1 MIC50: 0.25 MIC90: 0.5 |

NWT: 0, 0% Range: 0.13–4 MIC50: 0.25 MIC90: 0.25 |

| Liu et al. 10 | 248 | Sensititre YeastOne/CLSI BPs | R: 4, 1.6% I: 2, 0.8% Range: 0.015–2 MIC50: 0.03 MIC90: 0.03 |

R: 4, 1.6% I: 1, 0.4% Range: 0.03–2 MIC50: 0.12 MIC90: 0.25 |

R: 4, 1.6% I: 2, 0.8% Range: 0.015–>8 MIC50: 0.06 MIC90: 0.25 |

NWT: 0, 0% Range: 0.12–2 MIC50: 0.5 MIC90: 1 |

NWT: 3, 1.2% Range: <0.06–64 MIC50: 0.06 MIC90: 0.12 |

| Medeiros et al. 27 | 12 | CLSI M27-A3 | R: 0, 0% Range: <0.015–1.0 MIC50: <0.015 MIC90: 0.03 |

Not done | Not done | R: 0, 0% Range: 0.06–1.0 MIC50: 0.25 MIC90: 1.0 |

Not done |

| Megri et al. 4 | 19 | CLSI M27-A3 | R: 0, 0% | R: 0, 0% | Not done | NWT: 0, 0% | Not done |

| Siopi et al. 28 | 23 | Sensititre YeastOne/CLSI BPs | R: 0, 0% Range: 0.015–0.06 MIC50: 0.03 MIC90: 0.06 |

R: 0, 0% Range: ≤0.015–0.12 MIC50: ≤0.015 MIC90: 0.06 |

R: 0, 0% Range: 0.015–0.12 MIC50: 0.03 MIC90: 0.06 |

Not done | NWT: 0, 0% Range: ≤0.06–0.12 MIC50: ≤0.06 MIC90: 0.12 |

| Tasneem et al. 29 | 26 | CLSI M44-A disk diffusion | Not done | Not done | Not done | NWT: 0, 0% | Not done |

| Xiao et al. 30 | 379 | Sensititre YeastOne/CLSI BPs | R: 0, 0% GM: 0.03 Range: ≤0.008–0.06 |

R: 0, 0% I: 11, 0.3% GM: 0.05 Range: ≤0.015–0.5 |

R: 0, 0% GM: 0.04 Range: 0.15–0.25 |

NWT: 0, 0% GM: 0.68 Range: 0.25–1 |

NWT: 3, 1.1% GM: 0.04 Range: ≤0.06→64 |

Note: Susceptibility values are expressed as minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) in mg/L. BPs, breakpoints, GM, Geometric mean, MIC50, minimum inhibitory concentration of 50% of isolates, MIC90, minimum inhibitory concentration of 90% of isolates; S, susceptible; SDD, susceptible dose dependent; I, intermediate; R, resistant; WT, wildtype; NWT, non-wild type. Data are given as provided in source documents.

Resistance rates to fluconazole were variable between studies. A majority of the studies reported resistance rates of 0%–18%,10,16,21,26–34 with up to 3–4-fold increases in fluconazole resistance rates in the last 10 years16,31,32 though differences in methodology should be noted, as well as unclear interpretation of trailing endpoints. Four studies reported resistance rates as high as 36%–42% to fluconazole,35–38 from non-sterile sites. Similarly, non-wild type (non-WT) rates for itraconazole ranged from 0% to 26%,30–32,34,38,39 in most of the studies, except in three reporting rates of 41%–73%.16,35,37 For voriconazole, resistance rates were also generally comparable ranging from 0% to 22%,10,16,21,26,28,30–32,35,39 except in two studies by Wang et al. reporting 41%–44% resistance rates36,37 largely from urogenital tract isolates. Fan et al. and Siopi et al. reported 0% non-WT rates for posaconazole.28,32 In contrast, two studies reported high posaconazole non-wild type rates of 71%–83%.16,31 Chen et al. reported cross-resistance or non-wild type rate to itraconazole, voriconazole, and posaconazole in patients with fluconazole-resistant C. tropicalis infection.31 It should be noted however that these authors applied EUCAST breakpoints to a methodology designed for CLSI breakpoints, and it was not clear whether duplicate isolates from the same patient were included.

Resistance rates to echinocandins, including anidulafungin, caspofungin and micafungin were low (0%–1%).16,21,26,28,30–32,39 Similarly, C. tropicalis isolates showed a low non-WT rate to amphotericin B (0% in most studies)16,26,27,29–32,39 and to 5-flucytosine (0%–4%).16,30–32,35,39

Preventability

Risk factors for invasive C. tropicalis infections included leukaemia (OR 4.77) and chronic lung disease (OR 2.62)11 compared with infections caused by other Candida species (Table 6). Renal impairment and high Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II (APACHE II) score were also associated with C. tropicalis candidaemia compared with non-albicans Candida candidaemia (P < .001).2 A higher proportion of paediatric intensive care unit (PICU) patients with invasive C. tropicalis infections were more likely to have prolonged neutropenia compared with other Candida species infections (42% vs. 7.5%) (P < .05).24

Table 6.

Risk factors

| Author | Year | Study design | Study period | Country | Level of care | Population description | Number of patients | Risk factors | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fernández-Ruiz et al. 11 | 2015 | Retrospective cohort study | Multi-center | 05/2010–04/2011 | Spain | Tertiary | Patients with candidaemia | 59 | Bloodstream infections due to Candida tropicalis vs. other Candida species: Age [OR 1.01 (95% CI 1.00–1.02)], leukaemia [OR 4.77 (95% CI 1.96–11.6)], chronic lung disease [OR 2.62 (95% CI 1.44–4.77)] |

| Jordan et al. 24 | 2014 | Retrospective cohort study | Multi-center | 01/2008–12/2009 | Spain | Tertiary | Paediatric intensive care patients with invasive candidiasis | 19 | Neutropenia in 3/19 C. tropicalis vs. 5/125 any Candida species |

| Ko et al. 2 | 2019 | Retrospective cohort study | Multi-center | 01/2010–02/2016 | Korea | Tertiary | >16 years old with non-albicans candidaemia | 263 | Renal disease associated with C. tropicalis compared with other non-albicans species (P < .001), APACHE II scores were highest in C. tropicalis (P < .001) |

Annual incidence

Two studies reported on the annual incidence rates of C. tropicalis (Table 7). Fernández-Ruiz et al. reported an annual incidence of 0.62 cases per 100 000 population, based on the observation of 59/752 (7.8%) of candidaemia episodes involving C. tropicalis in Spain.11 In Australia, based on the observation of C. tropicalis accounting for 4%–5% of candidaemia cases, an annual incidence of C. tropicalis was estimated at 0.11 cases per 100 000 population.16

Table 7.

Annual incidence

| Author | Publication year | Study design | Study design | Study period | Country | Level of care | Population description | Number of patients | Annual incidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chapman et al.16 | 2017 | Prospective cohort study | Multi-center | 2014–2015 | Australia | Mix | Patients with candidaemia | 24 | 0.11/100 000/year based on Candida tropicalis comprising around 4%–5% of candidaemia (24 isolates of 548 episodes/526 patients) and population based on annual incidence of 2.41/100 000/year (for all candidaemia) |

| Fernández-Ruiz et al.11 | 2015 | Retrospective cohort study | Multi-center | 05/2010–04/2011 | Spain | Tertiary | 59 | 59 | Annual incidence 0.62 cases per 100 000 population |

Current global distribution

Data on the prevalence of C. tropicalis in different regions were observed to be limited. In addition to the studies reporting C. tropicalis incidence in Australia and Spain (Table 7),11,16 a single-center study conducted in Taiwan between 2009 and 2012 reported 52 C. tropicalis cases out of 242 candidaemia episodes in cancer patients, with an estimated incidence of 0.38 cases per 1000 hospital admissions (Table 8).40

Table 8.

Distribution

| Author | Publication year | Study design | Study period | Country | Level of care | Population description | Number of patients | Prevalence | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tang et al.40 | 2014 | Retrospective cohort study | Single-center | 2009–2012 | Taiwan | Tertiary | Adult patients with cancer | 52 | 0.38 per 1000 admissions (52 tropicalis out of 242 episodes of candidaemia with an incidence of 1.77 episode per 1000 admissions) |

Trends in last 10 years

Trends in the last 10 years for C. tropicalis could not be assessed due to a lack of data from the included studies.

Discussion

This systematic review synthesizes the available data on Candida tropicalis. Data specific to C. tropicalis is scarce with only 30 studies included in the final analysis over the 10 years. High-quality studies with low risk of bias represented just under half of these. However, the data available supports C. tropicalis as an important pathogen due to its increasing prevalence, high mortality, morbidity, and drug resistance.

The mortality of C. tropicalis infections appears to be higher than that of other Candida species. Overall mortality was as high as 55%–60% and was 26%–40% in paediatric patients, with the 30-day mortality of bloodstream infection between 32% and 52%. This compares poorly to the 30-day mortality of candidaemia overall (30%–40%).6–9,12 Virulence factors of C. tropicalis include biofilm formation which may contribute to worse outcomes along with higher rates of resistance.41,42Candida tropicalis pathogenicity is likely to be related to characteristics it shares with C. albicans of true pseudohyphae formation which aids adhesion, tissue penetration, biofilm formation and immune cell evasion, with data suggesting higher protease activity, host cell damage and biofilm formation than C. albicans,43–45 contributing to high mortality.43,46

Morbidity may also be greater for C. tropicalis though the impact on inpatient care, complications or sequelae could not be assessed due to lack of data. For other Candida species, hospital length of stay is 2–8 weeks, and the rate of complications or sequelae is considered ‘low’ as survivors are seldom left with disability.

Of concern, and related to worse outcomes, are the increasing resistance rates to azoles. Resistance or non-wild type rates varied, with higher rates of resistance noted from non-sterile sites, where susceptibility testing may only be done because of lack of clinical response. It should also be noted that C. tropicalis is renowned for the phenomenon of producing trailing endpoints in susceptibility tests, with unclear clinical significance.47 Few studies were noted to account for trailing,1,16,48 and user differences between reading endpoints by eye with CLSI methodology and reading of 51% inhibition being recorded as resistant by EUCAST methodology may also lead to differences in interpretation of the trailing phenomenon, as noted with the higher rates of azole resistance with EUCAST methodology compared to CLSI in Guinea et al.48 Nonetheless, the increasing reports of ERG11 gene mutations in C. tropicalis associated with high-level and pan-azole resistance indicates that true azole resistance is increasing in C. tropicalis, and support reports of around 15%–20% resistance which is increased from previous (7%).16,49 When examining studies with a low risk of bias, using CLSI methodology on blood culture isolates, the highest rate of fluconazole resistance was 16.7%.16 Low resistance or non-wild type rates to echinocandins, amphotericin B and flucytosine were reassuring. Data assessing whether decreased susceptibility of C. tropicalis to azoles is leading to breakthrough infections or failure of therapy are needed. Whilst azole prophylaxis in haematology patients is one factor associated with breakthrough azole-resistant C. tropicalis infection, other risk factors play a significant role.1,50 Azole use in the environment may select for azole-resistant C. tropicalis prevalent in enriched soil and be transferred into the food chain.41,51,52

Factors associated with the development of infection with C. tropicalis included immunosuppressive conditions such as leukaemia and organ dysfunction such as renal impairment and chronic lung disease. Preventative measures were not described in the retrieved articles. It remains to be seen whether measures that are relevant differ from those for other non-albicans Candida species and is an area for further research. Should colonization via the food chain prove important,41,51,52 reduction in environmental use of azoles as well as close attention to cleaning food and preparation may help. Antifungal stewardship in clinical medicine is also likely to be beneficial.53

The extent to which the incidence of C. tropicalis infections has increased also warrants further study. Annual incidence rates of C. tropicalis infections were reported in Spain (0.62/100 000 population)11 and in Australia (estimated to be 0.11/100 000 population).16 Infection with C. tropicalis is noted globally. Several reports have shown C. tropicalis increasing as a proportion of all candidaemia episodes in various locations especially Brazil14 and the Asia Pacific where it is reported as the most common species isolated.13

Limitations of this study include the relatively small number of studies eligible for inclusion, and the fact that many of these included substantial risk of bias. Conference abstracts were not assessed, and bias introduced by this could not be assessed, acknowledging that research from poorly resourced countries is less likely to progress to publication. Conclusions were limited by the high level of heterogeneity in the format of reporting outcome measures.

Cohort studies and sub-analysis evaluating morbidity outcome measures such as length of stay and long-term complications for invasive C. tropicalis infections are needed. Candida bloodstream infection is complicated by endocarditis in 2%–15% of cases and endophthalmitis in 1%–20% of cases, both of which are likely to have long-term morbidity though this is rarely measured.53–56 Whilst C. tropicalis is the causative agent in a minority of these complications,54–56 quantifying the long-term burden of illness on the healthcare system including cost analyses would help inform the need for preventative measures. Evaluation of potential in vitro and in vivo synergy between antifungal drugs could allow optimization of the current treatment regimens for C. tropicalis. Global surveillance studies could better inform the annual incidence rates, distribution and trends in other countries and regions.

Conclusion

Candida tropicalis is an important fungal pathogen associated with infection that carries a high mortality. Available data suggest increasing incidence and rates of resistance to azoles, though these as well as risk factor analysis are poorly quantified. There is a need for high-quality studies focused on C. tropicalis.

Acknowledgement

This work, and the original report entitled WHO Fungal Priority Pathogens List to Guide Research, Development, and Public Health Action, was supported by funding kindly provided by the Governments of Austria and Germany (Ministry of Education and Science). We acknowledge all members of the WHO Advisory Group on the Fungal Priority Pathogens List (WHO AG FPPL), the commissioned technical group, and all external global partners, as well as Haileyesus Getahun (Director Global Coordination and Partnerships Department, WHO), for supporting this work. The authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this article and do not necessarily represent the decisions, policies, or views of the World Health Organization.

Contributor Information

Caitlin Keighley, Sydney Infectious Diseases Institute, The University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia; Centre for Infectious Diseases and Microbiology Laboratory Services, Institute of Clinical Pathology and Medical Research, NSW Health Pathology, Westmead Hospital, Westmead, NSW, Australia; Southern IML Pathology, 3 Bridge St, Coniston, NSW, Australia.

Hannah Yejin Kim, Sydney Infectious Diseases Institute, The University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia; Faculty of Medicine and Health, School of Pharmacy, The University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia; Westmead Hospital, Westmead, NSW, Australia.

Sarah Kidd, National Mycology Reference Centre, Microbiology & Infectious Diseases, SA Pathology, Adelaide, SA, Australia; School of Biological Sciences, University of Adelaide, Adelaide, SA, Australia.

Sharon C-A Chen, Sydney Infectious Diseases Institute, The University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia; Centre for Infectious Diseases and Microbiology Laboratory Services, Institute of Clinical Pathology and Medical Research, NSW Health Pathology, Westmead Hospital, Westmead, NSW, Australia.

Ana Alastruey, Mycology Reference Laboratory, National Centre for Microbiology, Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Majadahonda, Madrid, Spain.

Aiken Dao, Sydney Infectious Diseases Institute, The University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia; Westmead Hospital, Westmead, NSW, Australia.

Felix Bongomin, Department of Medical Microbiology & Immunology, Faculty of Medicine, Gulu University, Gulu, Uganda.

Tom Chiller, Mycotic Diseases Branch, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GE, USA.

Retno Wahyuningsih, Department of Parasitology, Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Kristen Indonesia, Jakarta, Indonesia.

Agustina Forastiero, Servicio de Micologia, Laboratorio de Microbiologia, Hospital Britanico, Buenos Aires, Argentina.

Adi Al-Nuseirat, World Health Organization Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean, Cairo 11371, Egypt.

Peter Beyer, AMR Division, World Health Organization, Geneva.

Valeria Gigante, AMR Division, World Health Organization, Geneva.

Justin Beardsley, Sydney Infectious Diseases Institute, The University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia; Westmead Hospital, Westmead, NSW, Australia.

Hatim Sati, AMR Division, World Health Organization, Geneva.

C Orla Morrissey, The Alfred Hospital, Department of Infectious Diseases, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia; Monash University, Department of Infectious Diseases, Central Clinical School, Faculty of Medicine, Nursing and Health Sciences, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia.

Jan-Willem Alffenaar, Sydney Infectious Diseases Institute, The University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia; Faculty of Medicine and Health, School of Pharmacy, The University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia; Westmead Hospital, Westmead, NSW, Australia.

Author contributions

Caitlin Keighley (Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft), Hannah Yejin Kim (Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft), Sarah Kidd (Writing – review & editing), Sharon C-A. Chen (Writing – review & editing), Ana Alastruey (Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing), Aiken Dao (Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing), Felix Bongomin (Writing – review & editing), Tom Chiller (Writing – review & editing), Retno Wahyuningsih (Writing – review & editing), Agustina Forastiero (Writing – review & editing), Adi Al-Nuseirat (Writing – review & editing), Peter Beyer (Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing), Valeria Gigante (Writing – review & editing), Justin Beardsley (Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – review & editing), Hatim Sati (Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing), C. Orla Morrissey (Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – review & editing), and Jan-Willem Alffenaar (Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft)

Declaration of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1. Arastehfar A, Daneshnia F, Hafez A et al. Antifungal susceptibility, genotyping, resistance mechanism, and clinical profile of Candida tropicalis blood isolates. Med Mycol. 2020; 58:766–773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ko JH, Jung DS, Lee JY et al. Poor prognosis of Candida tropicalis among non-albicans candidemia: a retrospective multicenter cohort study, Korea. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2019; 95: 195–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Liu WL, Huang YT, Hsieh MH et al. Clinical characteristics of Candida tropicalis fungaemia with reduced triazole susceptibility in Taiwan: a multicentre study. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2019; 53: 185–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Megri Y, Arastehfar A, Boekhout T et al. Candida tropicalis is the most prevalent yeast species causing candidemia in Algeria: the urgent need for antifungal stewardship and infection control measures. Antimicrobial Resistance Infection Control. 2020;9: 50. 10.1186/s13756-020-00710-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Munoz P, Giannella M, Fanciulli C et al. Candida tropicalis fungaemia: incidence, risk factors and mortality in a general hospital. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2011; 17: 1538–1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Keighley C, Chen SC, Marriott D et al. Candidaemia and a risk predictive model for overall mortality: a prospective multicentre study. BMC Infect Dis. 2019; 19: 445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kofteridis DP, Valachis A, Dimopoulou D et al. Factors influencing non-albicans candidemia: a case-case-control study. Mycopathologia. 2017; 182: 665–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Magill SS, Edwards JR, Bamberg W et al. Multistate point-prevalence survey of health care-associated infections. N Engl J Med. 2014; 370: 1198–1208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lockhart SR, Iqbal N, Cleveland AA et al. Species identification and antifungal susceptibility testing of Candida bloodstream isolates from population-based surveillance studies in two U.S. cities from 2008 to 2011. J Clin Microbiol. 2012; 50: 3435–3442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Liu WL, Huang YT, Hsieh MH et al. Clinical characteristics of Candida tropicalis fungaemia with reduced triazole susceptibility in Taiwan: a multicentre study. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2019; 53: 185–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fernández-Ruiz M, Puig-Asensio M, Guinea J et al. Candida tropicalis bloodstream infection: incidence, risk factors and outcome in a population-based surveillance. J Infect. 2015; 71: 385–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Keighley CL, Pope A, Marriott DJE et al. Risk factors for candidaemia: a prospective multi-centre case-control study. Mycoses. 2020; 64: 257–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chakrabarti A, Sood P, Rudramurthy SM et al. Incidence, characteristics and outcome of ICU-acquired candidemia in India. Intensive Care Med. 2015; 41: 285–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pfaller MA, Diekema DJ, Gibbs DL et al. Results from the ARTEMIS DISK Global Antifungal Surveillance Study, 1997 to 2007: a 10.5-year analysis of susceptibilities of Candida apecies to fluconazole and voriconazole as determined by CLSI standardized disk diffusion. J Clin Microbiol. 2010; 48: 1366–1377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. McTaggart LR, Cabrera A, Cronin K, Kus JA-O. Antifungal susceptibility of clinical yeast isolates from a large Canadian reference laboratory and application of whole-genome sequence analysis to elucidate mechanisms of acquired resistance. LID - 10.1128/AAC.00402-20 [doi] LID - e00402-20. (1098-6596 (Electronic)). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chapman B, Slavin M, Marriott D et al. Changing epidemiology of candidaemia in Australia. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2017; 72: 1103–1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chen S, Slavin M, Nguyen Q et al. Active surveillance for candidemia, Australia. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006; 12: 1508–1516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021; 372: n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2019; 366:l4898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kim SY, Park JE, Lee YJ et al. Testing a tool for assessing the risk of bias for nonrandomized studies showed moderate reliability and promising validity. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013; 66: 408–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Arastehfar A, Polat SH, Daneshnia F et al. Recent increase in the prevalence of fluconazole-non-susceptible Candida tropicalis blood isolates in Turkey: clinical implication of azole-non-susceptible and fluconazole tolerant phenotypes and genotyping. Front Microbiol. 2020; 11: 587278. 10.1186/s13756-020-00710-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kang SJ, Kim SE, Kim UJ et al. Clinical characteristics and risk factors for mortality in adult patients with persistent candidemia. J Infect. 2017; 75: 246–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. You LS, Yao CY, Yang F et al. Echinocandins versus amphotericin B against Candida tropicalis fungemia in adult hematological patients with neutropenia: a multicenter retrospective cohort study. Infect Drug Resist. 2020; 13: 2229–2235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jordan I, Hernandez L, Balaguer M et al. C. albicans, C. parapsilosis and C. tropicalis invasive infections in the PICU: clinical features, prognosis and mortality. Rev Esp Quimioter. 2014; 27: 56–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Karadag-Oncel E, Kara A, Ozsurekci Y et al. Candidaemia in a paediatric centre and importance of central venous catheter removal. Mycoses. 2015; 58: 140–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Castanheira M, Deshpande LM, Messer SA, Rhomberg PR, Pfaller MA. Analysis of global antifungal surveillance results reveals predominance of Erg11 Y132F alteration among azole-resistant Candida parapsilosis and Candida tropicalis and country-specific isolate dissemination. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020; 55: 105799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Medeiros MAP, Melo APV, Bento AO et al. Epidemiology and prognostic factors of nosocomial candidemia in Northeast Brazil: a six-year retrospective study. PLoS One. 2019; 14:e0221033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Siopi M, Tarpatzi A, Kalogeropoulou E et al. Epidemiological trends of fungemia in Greece with a focus on candidemia during the recent financial crisis: a 10-year survey in a tertiary care academic hospital and review of literature. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2020; 64: e01516–19. 10.1186/s13756-020-00710-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tasneem U, Siddiqui MT, Faryal R, Shah AA. Prevalence and antifungal susceptibility of Candida species in a tertiary care hospital in Islamabad, Pakistan. J Pak Med Assoc. 2017; 67: 986–991. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Xiao M, Fan X, Chen SCA et al. Antifungal susceptibilities of Candida glabrata species complex, Candida krusei, Candida parapsilosis species complex and Candida tropicalis causing invasive candidiasis in China: 3 year national surveillance. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2015; 70: 802–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Chen PY, Chuang YC, Wu UI et al. Clonality of fluconazole-nonsusceptible Candida tropicalis in bloodstream infections, Taiwan, 2011–2017. Emerg Infect Dis. 2019; 25: 1660–1667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Fan X, Xiao M, Liao K et al. Notable increasing trend in azole non-susceptible Candida tropicalis causing invasive candidiasis in China (August 2009 to July 2014): molecular epidemiology and clinical azole consumption. Front Microbiol. 2017;8: 464. 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Khadka S, Sherchand JB, Pokhrel BM et al. Isolation, speciation and antifungal susceptibility testing of Candida isolates from various clinical specimens at a tertiary care hospital, Nepal. BMC Res Notes. 2017; 10: 218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Toda M, Williams SR, Berkow EL et al. Population-based active surveillance for culture-confirmed candidemia - four sites, United States, 2012–2016. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2019; 68: 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Katsuragi S, Sata M, Kobayashi Y et al. Antifungal susceptibility of Candida isolates at one institution. Med Mycol J. 2014; 55: E1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wang QY, Li CR, Tang DL, Tang KW. Molecular epidemiology of Candida tropicalis isolated from urogenital tract infections. Microbiologyopen. 2020;9: e1121. 10.1002/mbo3.1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wang QY, Tang DL, Tang KW, Guo J, Huang Y, Li CR. Multilocus sequence typing reveals clonality of fluconazole-nonsusceptible Candida tropicalis: a study from Wuhan to the global. Front Microbiol. 2020; 11: 11554249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Yfsudhason BL, Mohanrani K. Candida tropicalis as a predominant isolate from clinical specimens and its antifungal susceptibility pattern in a tertiary care hospital in Southern India. J Clin Diagnos Res. 2015;9: DC14–6. 10.7860/jcdr/2015/13460.6208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Guo LN, Xiao M, Cao B et al. Epidemiology and antifungal susceptibilities of yeast isolates causing invasive infections across urban Beijing, China. Future Microbiol. 2017; 12: 1075–1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Tang HJ, Liu WL, Lin HL, Lai CC. Epidemiology and prognostic factors of candidemia in cancer patients. PLoS One. 2014;9: e99103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Cordeiro Rde A, de Oliveira JS, Castelo-Branco Dde S et al. Candida tropicalis isolates obtained from veterinary sources show resistance to azoles and produce virulence factors. Med Mycol. 2015; 53: 145–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Moralez AT, Franca EJ, Furlaneto-Maia L, Quesada RM, Furlaneto MC. Phenotypic switching in Candida tropicalis: association with modification of putative virulence attributes and antifungal drug sensitivity. Med Mycol. 2014; 52:106–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Yang B, Wei Z, Wu M, Lai Y, Zhao W. A clinical analysis of Candida tropicalis bloodstream infections associated with hematological diseases, and antifungal susceptibility: a retrospective survey. Original research. Front Microbiol. 2023; 14: 1092175. 10.3389/fmicb.2023.1092175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Saiprom N, Wongsuk T, Oonanant W, Sukphopetch P, Chantratita N, Boonsilp S. Characterization of virulence factors in Candida species causing candidemia in a Tertiary Care hospital in Bangkok, Thailand. J Fungi (Basel). 2023;9: 353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.dos Santos MM, Ishida K. We need to talk about Candida tropicalis: virulence factors and survival mechanisms. Med Mycol. 2023; 61: myad075. 10.1093/mmy/myad075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Keighley C, Pope AL, Marriott D, Chen SC, Slavin MA., Group AaNZMI . Time-to-positivity in bloodstream infection for Candida species as a prognostic marker for mortality. Med Mycol. 2023; 61: myad028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Marcos-Zambrano LJ, Escribano P, Sánchez-Carrillo C, Bouza E, Guinea J. Scope and frequency of fluconazole trailing assessed using EUCAST in invasive Candida spp. Isolates. Med Mycol. 2016; 54: 733–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Guinea J, Zaragoza Ó, Escribano P et al. Molecular identification and antifungal susceptibility of yeast isolates causing fungemia collected in a population-based study in Spain in 2010 and 2011. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014; 58:1529–1537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Keighley C, Gall M, van Hal S et al. Whole genome sequencing shows genetic diversity, as well as clonal complex and gene polymorphisms associated with fluconazole non-susceptible isolates of Candida tropicalis. J Fungi. 2022;8: 896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kontoyiannis DP, Vaziri I, Hanna HA et al. Risk factors for Candida tropicalis fungemia in patients with cancer. Clin Infect Dis. 2001; 33: 1676–1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Lo HJ, Tsai SH, Chu WL et al. Fruits as the vehicle of drug resistant pathogenic yeasts. J Infect. 2017; 75: 254–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Yang YL, Lin CC, Chang TP et al. Comparison of human and soil Candida tropicalis isolates with reduced susceptibility to fluconazole. PLoS One. 2012;7: e34609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Keighley C, Cooley L, Morris AJ et al. Consensus guidelines for the diagnosis and management of invasive candidiasis in haematology, oncology and intensive care settings, 2021. Intern Med J. 2021; 51 Suppl 7: 89–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Prabhudas-Strycker KK, Butt S, Reddy MT. Candida tropicalis endocarditis successfully treated with AngioVac and micafungin followed by long-term isavuconazole suppression. IDCases. 2020; 21: e00889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Tanaka H, Ishida K, Yamada W, Nishida T, Mochizuki K, Kawakami H. Study of ocular candidiasis during nine-year period. J Infect Chemother. 2016; 22: 149–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Ueda T, Takesue Y, Tokimatsu I et al. The incidence of endophthalmitis or macular involvement and the necessity of a routine ophthalmic examination in patients with candidemia. PLoS One. 2019; 14: e0216956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6: e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Al-Obaid K, Asadzadeh M, Ahmad S, Khan Z. Population structure and molecular genetic characterization of clinical Candida tropicalis isolates from a tertiary-care hospital in Kuwait reveal infections with unique strains. PLoS One. 2017; 12:e0182292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Zhou J, Tan J, Gong Y, Li N, Luo G. Candidemia in major burn patients and its possible risk factors: a 6-year period retrospective study at a burn ICU. Burns. 2019; 45: 1164–1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Eliakim-Raz N, Babaoff R, Yahav D, Yanai S, Shaked H, Bishara J. Epidemiology, microbiology, clinical characteristics, and outcomes of candidemia in internal medicine wards—a retrospective study. Int J Infect Dis. 2016; 52: 49–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Wang Y, Shi C, Liu JY, Li WJ, Zhao Y, Xiang MJ. Multilocus sequence typing of Candida tropicalis shows clonal cluster enrichment in azole-resistant isolates from patients in Shanghai, China. Infect Genet Evol. 2016; 44: 418–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]