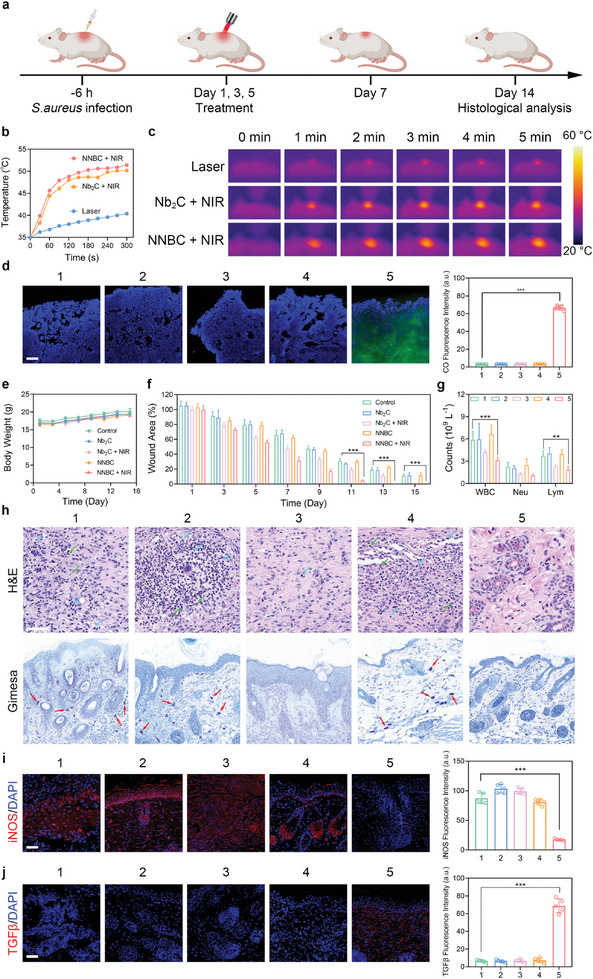

Figure 5.

In vivo experiment on the antibacterial ability of NNBCs in a skin wound model. a) Schematic illustration of the mouse model establishment and therapeutic process. b) Photothermal heating curves in various treatment groups and c) the corresponding thermographic images. d) CO generation in mouse skin wounds after various treatments (blue fluorescence: DAPI; green fluorescence: CO probe; scale bar = 50 µm; n = 5). e) Changes in the body weights of the mice from different treatment groups (n = 5). f) Quantitative analysis of the residual wounded areas after different treatments (n = 5). g) Blood parameters from various treatment groups, including white blood cell (WBC), neutrophils (Neu), and lymphocytes (Lym) (n = 5). h) H&E and Giemsa staining of the skin tissue in the wound areas from various treatment groups (green arrow: Neu; blue arrow: Lym; red arrow: bacteria). i) Inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS, M1‐type), and j) transforming growth factor β (TGF‐β, M2‐type) immunofluorescence staining of the skin tissue in the wound areas and the corresponding semi‐quantitative analysis. (1: control; 2: Nb2C; 3: Nb2C + NIR; 4: NNBC; 5: NNBC + NIR; scale bar = 50 µm; n = 5). All data are presented as the mean ± SD, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.