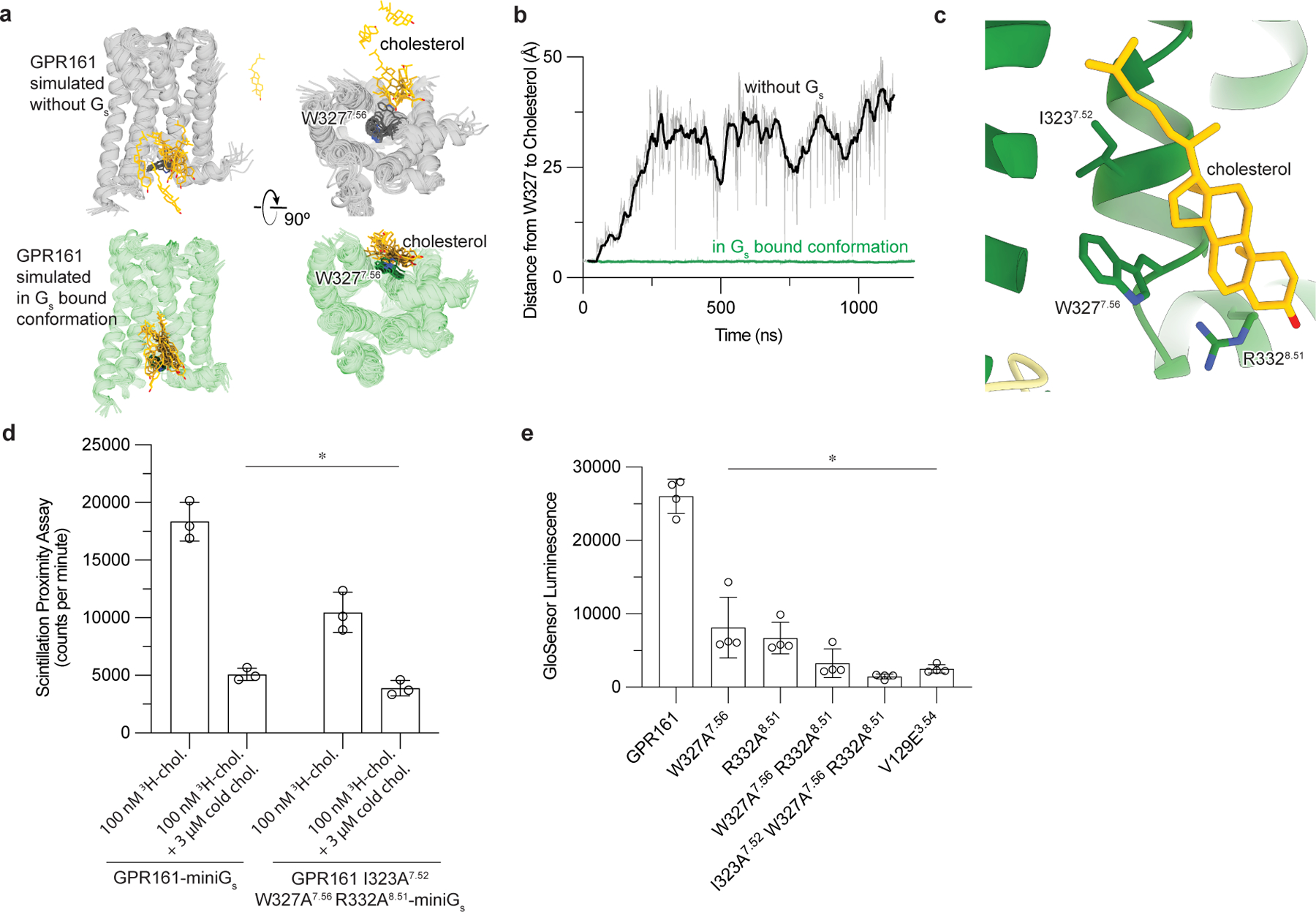

Figure 4: Cholesterol binding to GPR161 facilitates Gs coupling.

a)In unrestrained simulations of GP161 with miniGs removed, the initially bound cholesterol is highly dynamic and often dissociates from the receptor (top row; simulation snapshots shown in gray and yellow). By contrast, in simulations where GPR161 residues that contact miniGs are restrained to their miniGs bound conformation, cholesterol remains stably bound (bottom row; simulation snapshots shown in green and yellow). b) Time traces from representative simulations under each condition show that cholesterol dissociates in the former case but maintains its contact with residue W3277.56 in the latter case. See Methods. Data from remaining simulations is shown in Extended Data Figure 5. c) Close up view of cholesterol bound to the intracellular side of transmembrane helix 6 (TM6) and TM7. Three key interacting residues (I3237.52, W3277.56, R3328.51) are highlighted as sticks. d) 3H-cholesterol (3H-chol) binding assay for purified GPR161-miniGs and GPR161-AAA7.52, 7.56, 8.51-miniGs. Data are mean ± s.d. from n=3 biologically independent replicates (*P < 0.05; two-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison tests; adjusted P values: GPR161-miniGs vs.GPR161-AAA7.52, 7.56, 8.51-miniGs -miniGs=0.0002, GPR161-miniGs vs. GPR161-miniGs + cold chol. and GPR161-AAA7.52, 7.56, 8.51-miniGs + cold chol.=<0.0001). e) GloSensor cAMP production assay assessing mutations in cholesterol binding site of GPR161. Data are mean ± s.d. from n=4 biologically independent replicates (*P < 0.05; one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison tests; adjusted P values: <0.0001 for all mutants vs. GPR161 WT).