US health insurers seek to show that they really care

In John Q, a Hollywood blockbuster that topped the US box office on its opening weekend, it is not too difficult to spot the bad guys.

Denzel Washington plays John Q Archibald, a factory worker and regular guy who is doing all he can to support his wife and son. One day, the boy keels over while playing little league baseball, and only an emergency heart transplant can save him.

But there's a big problem. John's dastardly health insurers won't cover the costs of the operation. Unknown to John, his employer-sponsored health plan had been downgraded. The plan, says the hospital administrator, does not cover “a procedure of this magnitude.”

Time is running out. And so the increasingly distraught father takes the emergency room hostage, demanding that the cardiac surgeon performs the transplant. Dad may not have a great health plan, but he has a fantastic gun.

Why has John Q, released in the United States on 15 February, captured the imagination of the American public? The tense hostage scenes and a gun-toting Denzel must have played a part. But perhaps, more importantly, the film's portrayal of the limitations of health insurance has touched a raw nerve.

“Half of Americans say they had a problem with their health plan in the last year,” said Drew Altman, president of the Kaiser Family Foundation, which provides information on health issues to policymakers, the media, and the public. “Sometimes this problem is that the plan wouldn't cover health procedures.”

Altman said that the movie was inaccurate in one major way. It suggested that the biggest problem with health plans was that they did not cover emergencies. But the main problem, said Altman, was that patients could not “get lots of small things covered and so their care is delayed.”

But Altman believes that John Q was accurate in conveying one important truth. It was true, he said, that the public sometimes considered health insurers as “evil,” even if it was employers—not insurers—who had set the limitations on health coverage. “The public,” said Altman, “is angry with insurance companies, not with their [the public's] employers.”

The film is likely to add to the backlash against these companies, by portraying them as greedy, uncaring, and responsible for obstructing vital medical care. How would the industry respond to the movie's disparaging message?

John Q, said the Wall Street Journal (14 February 2002), offered health insurers an interesting marketing question: “Should they ignore the movie, attack it—or seize on it to promote their own agendas?”

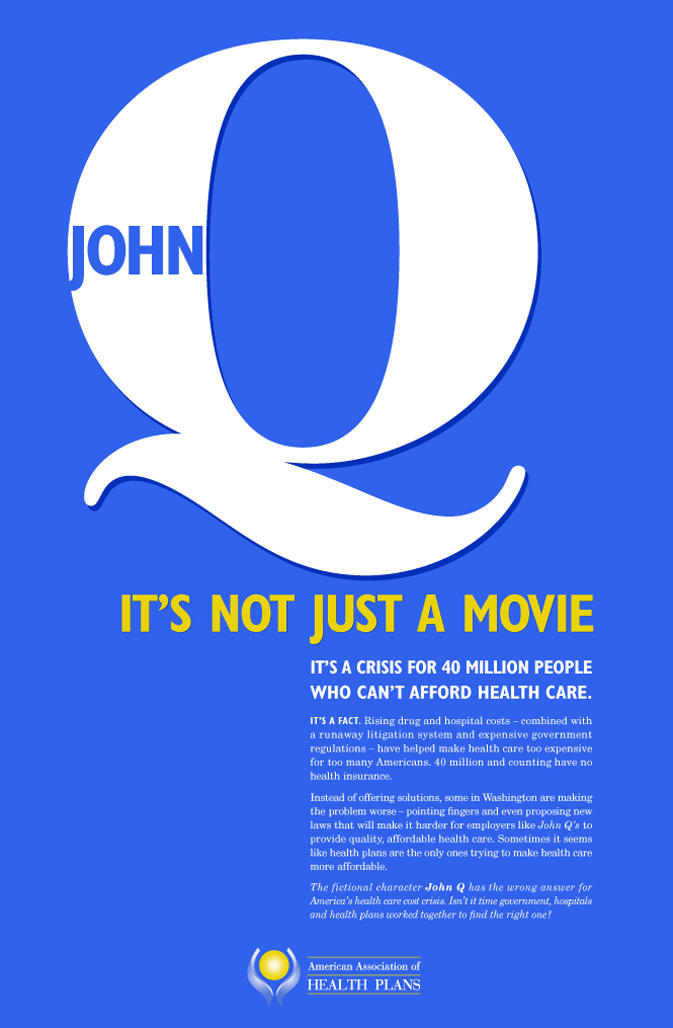

The insurers chose the last of these options, and did so in true Hollywood style. On the same day that the movie premiered, The American Association of Health Plans ran a full page, colour advertisement in Hollywood trade newspapers, and in the Capitol Hill paper Roll Call. The ad puts a major spin on the movie's message.

“John Q—It's not just a movie,” said the ad, “it's a crisis for 40 million people who can't afford health care.” Health insurers, of course, were not to blame.

Instead, the crisis was due to “rising drug and hospital costs,” a “runaway litigation system,” and “expensive government regulations.” The ad pointed the finger at “some in Washington” for proposing “new laws that will make it harder for employers like John Q's to provide quality, affordable health care.”

In the ad, the industry gave itself a pat on the back: “Sometimes it seems like health plans are the only ones trying to make health care more affordable.” The ad sought to turn the bad guys in John Q into the good guys.

Defensive posturing? Not at all, said the association's president, Karen Ignani. “We're not being defensive here,” she told the Wall Street Journal, “we're trying to shine a spotlight on the problem.”

Mark Merritt, the association's senior vice president, told the Washington Post (14 February 2002) that he was “a huge Denzel Washington fan.” It made sense, he said, for the association to adopt John Q, as a way of showing that health insurers do care about the uninsured millions.

This is not the first time that a Hollywood movie has attacked the US health insurance industry. In As Good As It Gets, for example, the lead character rages against her health insurer for obstructing her son's asthmatic care. But this is the first time that the insurance industry has advertised in showbiz papers.

The industry's glitzy adoption of John Q as a tool for its own political gain is a clever, if not transparent, piece of media manoeuvring. “The industry is artfully doing damage control,” said Drew Altman.

Will the damage control be enough? This seems extremely unlikely, given that John Q confirms to the public its deep suspicions about health plans. “People are afraid,” said Altman, “that the health plan won't be there for them when they are really sick.” The industry ad will not be enough to calm the public's jangled nerves.

Figure.

How health insurers put a spin on the movie's message

Figure.

™ © 2002, NEW LINE CINEMA

Denzel Washington (left) as John Q has captured the American public's imagination