Abstract

Objective:

This review aimed to synthesize the experiences of patients with metachromatic leukodystrophy, adrenoleukodystrophy, or Krabbe disease and the experiences of their families.

Introduction:

Leukodystrophies are metabolic diseases caused by genetic mutations. There are multiple forms of the disease, varying in age of onset and symptoms. The progression of leukodystrophies worsens central nervous system symptoms and significantly affects the lives of patients and their families.

Inclusion criteria:

Qualitative studies on the experiences of patients with leukodystrophies and their family members were included. These experiences included treatments such as enzyme replacement therapy and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; effects of tracheostomy and gastrostomy; burdens on the family, coordinating care within the health care system, and family planning due to genetic disorders. This review considered studies in any setting.

Methods:

MEDLINE (Ovid), CINAHL Plus (EBSCOhost), APA PsycINFO (EBSCOhost), Scopus, and MedNar databases were searched on November 18, 2022. Study selection, critical appraisal, data extraction, and data synthesis were conducted in accordance with the JBI methodology for systematic reviews of qualitative evidence, and synthesized findings were evaluated according to the ConQual approach.

Results:

Eleven studies were eligible for synthesis, and 45 findings were extracted corresponding with participants’ voices. Of these findings, 40 were unequivocal and 5 were credible. The diseases in the included studies were metachromatic leukodystrophy and adrenoleukodystrophy; no studies were identified for patients with Krabbe disease and their families. These findings were grouped into 11 categories and integrated into 3 synthesized findings, including i) providing care by family members and health care providers as physical symptoms progress, which relates to the effects of the characteristics of progressive leukodystrophies; ii) building medical teamwork to provide appropriate support services, comprising categories related to the challenges experienced with the health care system for patients with leukodystrophy and their families; and iii) coordinating family functions to accept and cope with the disease, which included categories related to family psychological difficulties and role divisions within the family. According to the ConQual criteria, the second synthesized finding had a low confidence level, and the first and third synthesized findings had a very low confidence level.

Conclusions:

The synthesized findings of this review provide evidence on the experiences of patients with metachromatic leukodystrophy or adrenoleukodystrophy and their families. These findings indicate that there are challenges in managing a patient’s physical condition and coordinating the health care system and family functions.

Review registration:

PROSPERO CRD42022318805

Supplemental digital content:

A Japanese-language version of the abstract of this review is available [http://links.lww.com/SRX/A49].

Keywords: adrenoleukodystrophy, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, Krabbe disease, metachromatic leukodystrophy, quality of life

ConQual Summary of Findings

| Experiences of patients and their family members with metachromatic leukodystrophy, adrenoleukodystrophy, and Krabbe disease | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bibliography: Koto Y, Ueki S, Yamakawa M, Sakai N. Experiences of patients with metachromatic leukodystrophy, adrenoleukodystrophy, and Krabbe disease and their family members: a qualitative systematic review. JBI Evid Synth. 2024;?():??-?? | |||||

| Synthesized finding | Type of research | Dependability | Credibility | ConQual score | Comments |

| Providing care by family members and health care providers as physical symptoms progress | Qualitative | Low (downgraded 2 levels) | Moderate (downgraded 1 level) | Very low | Downgraded 3 levels: Dependability downgraded 2 levels because 1 study was not clear on all 5 items assessing dependability. Of the other 4 studies, statements explaining the influence of the researcher were not present in all 4 included studies, statements identifying the researcher’s location were not present in 3 studies, and 1 study was not clear on the consistency between methodology and analytical method. Credibility downgraded 1 level due to a mix of U and C findings |

| Building medical teamwork to provide appropriate support services | Qualitative | Moderate (downgraded 1 level) | Moderate (downgraded 1 level) | Low | Downgraded 2 levels: Dependability downgraded 1 level because statements explaining the influence of the researchers were not present in all 8 included studies, statements identifying the researcher’s location were not present in 7 studies, and 1 study was not clear on the consistency between methodology and analytical method.Credibility downgraded 1 level due to a mix of U and C findings |

| Coordinating family functions to accept and cope with the disease | Qualitative | Low (downgraded 2 levels) | Moderate (downgraded 1 level) | Very low | Downgraded 3 levels: Dependability downgraded 2 levels because 1 study was not clear on all 5 items for assessing dependability. Of the other 7 studies, statements explaining the influence of researcher were not present in all 7 included studies and statements identifying the researcher’s location were not present in 6 studies. Credibility downgraded 1 level due to a mix of U and C findings |

U, unequivocal; C: credible

Introduction

Lysosomal storage and peroxisomal disorders are rare diseases that comprise over 50 disorders. These diseases are intractable inborn errors of metabolism caused by different genetic lesions and lead to impaired lysosomal and peroxisomal functions. Persons with these diseases present with symptoms throughout the body owing to the accumulation of metabolic substances; however, the diseases that present symptoms in the cranial nervous system have a significant impact on patients’ lives. Among these diseases, leukodystrophy of the central nervous system includes metachromatic leukodystrophy (MLD), adrenoleukodystrophy (ALD), and Krabbe disease (globoid cell leukodystrophy). These 3 conditions have a similar pathophysiology of leukodystrophy caused by demyelination in the central nervous system and show a similar clinical phenotype, although the causative gene is different. The progression of leukodystrophy associated with demyelination causes cognitive and neurological dysfunction, which interferes with the daily life of patients and their families.1–3

MLD is an autosomal recessive hereditary disease caused by a deficiency of arylsulfatase A.1 The incidence of MLD is estimated to be 0.16–2.0 per 100,000 live births.4,5 The disease is classified into 4 types according to age of onset and clinical course: i) late infantile, ii) early juvenile, iii) late juvenile, and iv) adult-onset.6 The most common late infantile form develops before 2 years of age and presents with hypotonia, loss of deep tendon reflexes, and gait disturbance. The juvenile type develops between ages 2.5 and 16 years, and presents with optic nerve atrophy, intellectual disability, and spastic paraplegia. Patients with juvenile MLD become bedridden approximately 18 months after onset.1 Adult-onset type develops over 16 years of age, leading to motor and cognitive impairments.6 Although enzyme replacement therapy, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT), and gene therapy are promising treatment options, symptomatic therapies, such as antiepileptic drugs and muscle relaxants, are currently used.1

ALD is an X-linked genetic disorder caused by ABCD1 gene mutations. It involves demyelination in the central nervous system and adrenal glands.2 The incidence of ALD in Asia is 0.2–0.7 patients per 100,000 live births.4,7 However, incidence varies by race, with a reported 1.3/100,000 live births among non-Hispanic Blacks and 2.4/100,000 live births among non-Hispanic Whites.7 Childhood cerebral ALD is the most common type of ALD and occurs between the ages of 3 and 10 years. Patients may present with impaired academic performance, vision, and cognitive function, and progress quickly to a vegetative state.2 In addition, there are various clinical types of ALD, including adrenomyeloneuropathy with spastic gait after 20 years of age and Addison disease with only adrenal insufficiency symptoms. The treatments for cerebral ALD are HSCT and gene therapy by early detection.2,8

Krabbe disease is an autosomal recessive genetic disorder caused by galactocerebrosidase deficiency. Patients with Krabbe disease present with central and peripheral neuropathies.3 The disease can be classified into 4 types based on the age of onset: i) early infantile, ii) late infantile, iii) juvenile, and iv) adult. The incidence of early infantile type is 1 in 394,000 births.9 Early infantile Krabbe disease develops around 6 months of age and progresses rapidly. Patients become bedridden by 1 year of age and die by 2 or 3 years of age.3 Patients with the late infantile or juvenile types can live longer than patients with the early infantile type. Patients with adult Krabbe disease have gait changes, muscle weakness, and spastic paraplegia.3 HSCT is an effective treatment for patients with infantile Krabbe disease.10

Diagnosis of MLD and Krabbe disease is confirmed by a decrease in enzyme activity or presence of pathological mutations.4,10 ALD is diagnosed by increasing levels of very long-chain fatty acids.2 Early detection of Krabbe disease through newborn screening is being attempted.10,11 Because these diseases are hereditary, the diagnosis of one patient may lead to the discovery that a family member is a patient or carrier; therefore, it is important to provide genetic counseling for patients and their family members. Patients receive supportive therapy and HSCT for the treatment of these diseases.1–3 Early HSCT can improve life expectancy,2,10,12 whereas complications, such as graft-vs-host disease, may lead to increased suffering.12

The progression of a patient’s symptoms places a heavy burden on the family as the level of care required increases.4 The need for nighttime endotracheal suctioning and restrictions on activities, such as going out of the house, affect the lives of the family as well as the patient.13 As symptoms progress, patients have difficulty speaking. When the disease progresses to the point the patient is in a vegetative state, end-of-life care is important.3

Few quantitative studies have focused on the quality of life (QOL) of patients with MLD, ALD, or Krabbe disease and their family members. In a quantitative study that determined the impact of leukodystrophy on patients’ QOL, a disease-specific QOL scale for patients with Krabbe disease was developed.14 Another study found that mothers of patients with MLD have a lower QOL than the general population.15 It is important to interpret the experiences of patients and their families to identify the impact and challenges of the disease on their lives. Understanding the details of these experiences and accumulating information can allow health care providers to consider ways to assist patients and family members. Therefore, the synthesis of qualitative studies based on the experiences of patients and their family members is required. However, it was anticipated there would be limited studies on patients’ experiences because it would not be possible to interview patients after their symptoms had progressed to the point where conversation would be difficult.

A preliminary search of PROSPERO, MEDLINE, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, and JBI Evidence Synthesis was conducted, and no current or in-progress systematic reviews on the topic were identified. In the preliminary search of MEDLINE, we identified 5 articles on the experiences of parents of patients with leukodystrophy.15–19 Three papers on parents of children with ALD revealed families’ experiences with newborn screening, diagnosis, and long-term care.17–19 Two papers on MLDs revealed findings on health care services and patients’ and family members’ QOL.15,19 The articles obtained from the preliminary search showed that ALD and MLD affect the lives of patients and their families in several ways. Each study focused on different events, and the synthesis of such findings is necessary to clarify the overall experiences of patients and their families.

This review aimed to synthesize the experiences of patients with MLD, ALD, or Krabbe disease and their families to reveal the impact of treatment and home care burden. The resulting synthesized findings show the challenges faced by patients and their family members, the support they seek, and factors that influence QOL, all of which may be used in diagnosis, treatment, and support at home.

Review question

What are the experiences of patients with MLD, ALD, or Krabbe disease and the experiences of their family members?

Inclusion criteria

Participants

The target population for this review was patients with MLD, ALD, or Krabbe disease, and their family members. These diseases, categorized as lysosomal and peroxisomal diseases, share similar symptoms and treatments. Leukodystrophies have similar symptoms but different disease mechanisms, prognoses, and treatment. For this reason, studies focusing on patients and families with leukodystrophies other than MLD, ALD, or Krabbe disease were excluded from this review. Due to the rarity of the target diseases, qualitative studies on multiple diseases that included the target diseases of this review were eligible for inclusion.19,20 However, if we were unsure whether findings/illustrations were from individuals with the target diseases or their family members, the findings were not included in the data extraction and synthesis. Eligible participants were not restricted by sex because ALD is X-linked, and MLD and Krabbe disease are associated with autosomal mutations. Because disease progression and prognosis differ depending on the target disease type, there were no restrictions on the age or disease type of the participants. This review included the patient’s parents, siblings, and children as family members. If study participants were described as caregivers, we included the study in the synthesis only after confirming that the caregivers were clearly stated as family members. This was because the progression of the target disease necessitates daily care. Also, family members may be carriers of a pathogenic variant, as these are hereditary diseases.

Phenomena of interest

This review focused on the experiences of patients with MLD, ALD, or Krabbe disease and their families. Life experiences covered treatments, such as HSCT and gene therapy, as well as supportive care experiences, such as home care and ventilator use. In addition to the effectiveness and complications of treatment, we considered experiences related to the physical condition of patients using tracheostomies and gastric lavage, as well as the burden of family caregiving. Furthermore, eligible studies may have focused on the impact of being a genetic carrier on family relationships and family planning. The review included those related to the patient’s health care environment and experiences with diagnosis, health care systems, health care services, and social resources. The phenomena of interest also included the social context, such as patient and family insurance coverage and newborn screening.

Context

This review considered studies in any setting. Challenges and disadvantages for patients and families with leukodystrophy can occur in different contexts, such as hospitals, homes, day care services, schools, and workplaces. MLD, ALD, and Krabbe disease have different prevalence rates depending on the country and region,2 thus there were no restrictions regarding countries or regions in this review.

Types of studies

This review considered qualitative studies. Eligible study designs included phenomenology, grounded theory, ethnography, action research, and qualitative descriptive studies. We planned to include mixed methods studies if qualitative results could be analyzed separately; however, no mixed methods studies were eligible for inclusion.

Methods

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with the JBI methodology for systematic reviews of qualitative evidence.21 Selected studies were evaluated against the inclusion criteria, and then assessed for methodological quality. If judged to meet the criteria, the data were extracted and synthesized. The synthesized findings were graded according to the ConQual approach.22 This review was conducted in accordance with an a priori protocol23 and registered with PROSPERO (CRD42022318805).

Search strategy

Search strategies were developed for published and unpublished articles. The search strategy took place in 3 phases. First, an initial limited search of MEDLINE (Ovid) and CINAHL Plus (EBSCOhost) was conducted to identify articles on the topic. To develop a full search strategy for MEDLINE (Ovid), CINAHL Plus (EBSCOhost), APA PsycINFO (EBSCOhost), and Scopus, we used text words from the titles and abstracts of relevant articles and index terms describing the articles. The search strategy, including all identified keywords and index terms, were adapted for each included database and information source (Appendix I). All reference lists of included studies were scrutinized for additional studies. We searched for unpublished studies and gray literature using MedNar. The gray literature was to include academic papers, dissertations, research reports, committee reports, government reports, and conference papers that comprised qualitative studies.

No language restrictions were imposed. For articles in languages other than English, we searched for an English-language abstract to assess the content. If an English-language abstract was not available or if the reviewer determined that a translation was necessary, we asked a translation company (Tokyo Hanyaku Co., Ltd.) that employs native speakers to translate it into English.

Because these diseases are rare and the number of identified publications was expected to be small, no publication date limit was set in order to search as broadly as possible.

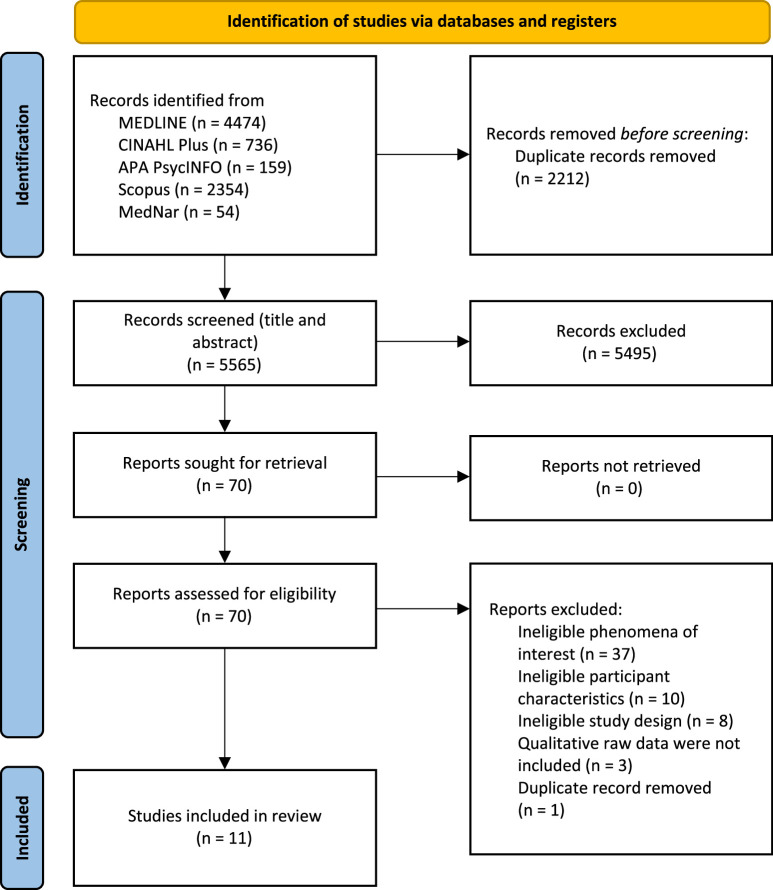

Study selection

After the search, all identified citations were collated and uploaded to EndNote v.X9.2 (Clarivate Analytics, PA, USA), and duplicate records were removed. Duplicate records that were not deleted by the EndNote function were deleted manually. Two reviewers (YK, SU) independently assessed the titles and abstracts, according to the inclusion criteria. A pilot test was conducted, in which 20 randomly selected study titles and abstracts were independently screened by 2 reviewers (YK, SU) to ensure that there were no differences in their judgments. The results of the pilot testing confirmed that the 2 reviewers’ judgments were 100% consistent. Potentially eligible studies were retrieved in full, and their citation details were imported into the JBI System for the Unified Management, Assessment and Review of Information (JBI SUMARI; JBI, Adelaide, Australia).24 The full text of the selected studies were assessed in detail by 2 reviewers (YK, SU) independently according to the inclusion criteria. We provided reasons for the exclusion of articles at full-text screening in Appendix II. Reviewers planned to resolve any difference through discussion or with a third reviewer; however, this was not required. The search results and study inclusion process are presented in a Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram (Figure 1).25

Figure 1.

Search results and study selection and inclusion process.25

Assessment of methodological quality

Eligible studies were critically assessed for methodological quality by 2 reviewers (YK, SU) independently. The standard JBI critical appraisal checklist for qualitative research was used.21 This checklist comprises 10 items to determine whether there are appropriate statements related to the consistency of the purpose, methodology, and trustworthiness of qualitative research. The checklist included yes, no, and unclear options; unclear was used when a simplified description or text was present in the study, but details were unknown.

In 2 studies, sufficient details were not provided in the article; in these cases, the reviewers contacted the authors of the articles and requested missing or additional data for clarification. If any disagreements arose between the reviewers at the selection process, they were resolved through a discussion or with a third reviewer (MY). The results of the critical appraisal are presented in narrative format and in Table 1.

Table 1.

Critical appraisal of eligible qualitative studies

| Study | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Q9 | Q10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brown, et al. 201830 | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | N | Y | Y | Y |

| Eichler, et al. 201613 | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | N | Y | Y | Y |

| Eichler, et al. 202231 | N | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y |

| Feng, et al. 201918 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y |

| Forrest, et al. 200820 | N | U | U | U | U | N | N | Y | Y | Y |

| Lee, et al. 201417 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y |

| Morton, et al. 202233 | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y |

| Nepomuceno, et al. 201232 | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y |

| Pasquini, et al. 202119 | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y |

| Santos, et al. 201834 | N | Y | Y | Y | U | N | N | Y | Y | Y |

| Schwan, et al. 201916 | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y |

| Total % | 18 | 91 | 91 | 82 | 82 | 9 | 0 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

Y, yes; N, no; U, unclear

JBI critical appraisal checklist for qualitative research.

Q1 = Is there congruity between the stated philosophical perspective and the research methodology?

Q2 = Is there congruity between the research methodology and the research question or objectives?

Q3 = Is there congruity between the research methodology and the methods used to collect data?

Q4 = Is there congruity between the research methodology and the representation and analysis of data?

Q5 = Is there congruity between the research methodology and the interpretation of results?

Q6 = Is there a statement locating the researcher culturally or theoretically?

Q7 = Is the influence of the researcher on the research, and vice-versa, addressed?

Q8 = Are participants and their voices adequately represented?

Q9 = Is the research ethical according to current criteria or, for recent studies, is there evidence of ethical approval by an appropriate body?

Q10 = Do the conclusions drawn in the research report flow from the analysis, or interpretation, of the data?

After critical appraisal, to ensure the quality of the studies in terms of methodology and adequately capturing the voice and meaning of the participants, studies that did not meet the criteria were excluded. Therefore, studies that answered yes to Q8 (Are participants and their voices adequately represented?) on the JBI checklist were selected for inclusion. This criterion was applied to ensure the confidence of the extracted findings; this question is considered an essential element in the synthesis of qualitative findings to properly understand what the findings represent. Studies that did not meet this criterion were excluded and are listed in Appendix III.

Data extraction

Data from the studies included in the review were extracted independently by 2 reviewers (YK, SU) using the standardized JBI data extraction tool in JBI SUMARI.21,24 The data extracted included specific details about the populations, context, culture, geographical location, study methods, and the phenomena of interest relevant to the purpose of the review. The findings and the participants’ voices were extracted verbatim to assess the level of credibility of the findings. The results are summarized in Appendix IV. When disagreements arose among reviewers during the selection process, they were resolved by a discussion. The plan was to discuss the issue with a third reviewer if it could not be resolved by the 2 reviewers; however, no disagreements arose that needed to be resolved. If necessary, reviewers planned to contact the authors of the articles to request clarifications regarding any missing or additional data; however, besides inquiries made during the assessment of methodological quality, no contact with the authors was required during data extraction.

Data synthesis

We used a meta-aggregation method for the extracted qualitative findings and synthesized them using JBI SUMARI.26 Findings extracted for this review were the highest levels provided in each paper; for example, if findings were presented as themes and subthemes, the themes were extracted. This extraction method involved integrating findings by assembling and classifying these findings based on semantic similarities to generate a set of statements. These categories created a single set of synthesized findings that may serve as a basis for evidence-based practice. The categories were created for synthesized findings with at least 2 findings per category. We included only unequivocal and credible findings in the synthesis. We relied on consensus among the authors for naming of synthesized findings and categories.

In the event of difficulties integrating experiences of patients and their families into a single category, the authors planned to create separate integrated sets for the 2 participant types; however, this was not required.

Assessing confidence in the findings

The final synthesized findings were evaluated according to the ConQual approach to establish confidence of qualitative synthesis results. The process for the determination of the ConQual score for the synthesized findings is described in the Summary of Findings with the main elements and details of the review.22 The Summary of Findings also includes the title, population, phenomena of interest, and context of the review. It also presents each synthesized finding, along with the study type, dependability, credibility, and overall ConQual score.

Results

Study inclusion

The comprehensive database searches identified 7777 potentially relevant records. After removal of duplicates via EndNote and manually (n=2212), the titles and abstracts of the remaining records were assessed (n=5565). Following this assessment, 5495 records were excluded. The 70 remaining records underwent full-text screening; 56 articles were excluded after this step because they did not meet the inclusion criteria (Appendix II). The reasons for the exclusion of these 56 articles were ineligible phenomena of interest (n=37), ineligible disease (n=10), ineligible study design (n=8), and duplicate record (n=1). There were several disagreements between the 2 reviewers during the screening of the titles and abstracts and full-text screening; however, the disagreements were resolved after discussion.

The reference lists of the remaining 14 studies were checked, and no further eligible studies were identified. The remaining studies were then critically appraised for methodological quality, and 3 studies27–29 were rated unclear on Q8 of the JBI critical appraisal checklist (Are participants and their voices adequately represented?) because they did not include qualitative raw data. These studies were excluded, as per the a priori protocol.23 In total, 11 studies were included in the review.13,16–20,30–34 The full study selection process is shown in Figure 1.25

Methodological quality

As previously mentioned, 3 studies were ineligible for inclusion after methodological quality assessment due to responses of unclear on Q8 (Appendix III). One paper explicitly stated that it would not publish direct quotes because the rarity of the disease would lead to identification of the participants.28 The authors of the other 2 articles were contacted to request additional information; however, these authors either declined to provide raw data or there was no reply to inquiry.27,29

For the overall quality score, none of the remaining 11 studies met all of the appraisal criteria. One study met 9 criteria,18 1 study met 8 criteria,17 6 studies met 7 criteria,13,16,19,30,32,33 2 studies met 6 criteria,31,34 and 1 study met 3 criteria.20 All studies met the criteria for Q8, Q9, and Q10. Additionally, no study met the criterion for Q7 (Is the influence of the researcher on the research, and vice-versa, addressed?), 18% of the studies met the criterion for Q1 (Is there congruity between the stated philosophical perspective and the research methodology?), and 9% met the criterion for Q6 (Is there a statement locating the researcher culturally or theoretically?). Meanwhile, 91% of the studies met the criteria for Q2 (Is there congruity between the research methodology and the research question or objectives?) and Q3 (Is there congruity between the research methodology and the methods used to collect data?), and 82% met the criteria for Q4 (Is there congruity between the research methodology and the representation and analysis of data?) and Q5 (Is there congruity between the research methodology and the interpretation of results?). Thus, we obtained qualitative data on the experiences of patients and their families. However, the included articles were not sufficiently rigorous with regard to their philosophical background, cultural location of the researchers, or the influence of the researchers on the results.

Characteristics of included studies

The characteristics of the included studies are presented in Appendix IV. Studies included those conducted in a single country or region as well as those conducted across multiple countries. Of the studies conducted in a single country, 3 were conducted in the United States,16,19,30 2 in Brazil,32,34 2 in Taiwan,17,18 and 1 in Australia.20 In studies conducted in multiple countries, 1 study was conducted in the United States, France, Germany, and Colombia13; 1 study in the United States, France, Germany, and the United Kingdom31; and 1 study in the United Kingdom and Republic of Ireland.33 Two studies were written in a language other than English (Chinese18 and Portuguese32) and the full texts were translated by a translation company (Tokyo Hanyaku Co., Ltd.) into the reviewers’ native language, Japanese, to facilitate understanding. The findings and illustrations were then translated into English by the translation company.

All studies were published between 2008 and 2022. The context of all studies was the community. Nine studies involved parents or caregivers13,16–20,30,31,33 and 2 studies involved the family unit, such as parents and siblings.32,34 No studies directly involved patients. The diseases targeted by the included studies were MLD13,19,30,31,33 and ALD.16–18,20,32,34 There were no studies on Krabbe disease.

Data collection methods included 6 semi-structured interviews,13,18–20,30,33 2 studies used in-depth interviews with open-ended questions,16,17 2 used in-depth interviews in a life history study,32,34 and 1 used an online survey and semi-structured telephone interview.31 For methodology and analytical methods, the studies employed a modified grounded theory approach,19 constant comparative analysis paradigm,30 combined grounded theory approach and content analysis methods,13 thematic analysis,16 inductive thematic content approach,33 phenomenological analysis,17,18 life story research method,32,34 and descriptive analytics31; and qualitative descriptive.20

In total, 107 participants and 2 families were included across the 11 studies. Of these participants, 49 were mothers and 7 were fathers. Additionally, 50 family members and 1 caregiver were included, although their relationships with the patients were not specified. Because some papers used the word caregiver instead of parent or family member, the term caregiver was used in the citations of the raw data; however, these caregivers were all parents or family members. There were 2 studies in which the number of participants for the target diseases was not stated.19,20 Only 3 studies provided information on the age of the participants: 1 with a mean age of 48.6 (range, 37–58) years,30 1 with a mean age of 41.8 years,18 and another with a range of 33–52 years.17 Only 2 studies reported on the age of patients with the target disease, 1 with a mean age of 19.0 years30 and the other with an age range of 10–16 years.18 Two studies described the ethnicity of the participants: the first with all Caucasian participants30 and the second with 5 Caucasian, 2 Latino, 2 mixed ethnicity, and 1 African American.16 Only 1 study described faith, and of the 8 participants, 3 were Taoists, 2 were Buddhists, 2 were Christians, and 1 had no religion.17

One study that reported on health insurance included information on the type of insurance coverage of the participants.19 Employer-sponsored insurance coverage was 100%; some children were covered by additional public insurance: Medicaid 40%, Medicare 6.7%, children’s health insurance 13.3%, and medical assistance program (state or county) 13.3%.

Review findings

In total, 45 findings with narrative illustrations were extracted from the 11 studies; of these, 40 were assessed as being unequivocal and 5 were determined to be credible (Appendix V). The protocol stated that patients’ and family members’ experiences may be separated for synthesis if necessary23; however, all findings were based on the experiences of parents or family members (as previously noted, caregivers in the raw data were all parents or family members). All findings were subject to synthesis, and no separation was needed.

Through the synthesis, the findings were aggregated into 11 categories based on similarity of meaning. The categories were then synthesized to generate 3 synthesized findings. The confidence of the synthesized findings was graded using the ConQual approach (see the Summary of Findings).22 One of the included studies received yes responses for 4 of the 5 ConQual criteria for dependability18 (Q2, Q3, Q4, Q6, Q7); 8 studies received yes responses for 3 of the criteria13,16,17,19,30,32–34; 1 study for 2 of the critera31; and 1 study did not receive a yes response for any of the 5 dependability criteria.20 Based on these findings for dependability, in accordance with the ConQual guidelines, the confidence of 1 of the synthesized finding was downgraded 1 level and 2 synthesized findings were downgraded 2 levels. All 3 synthesized findings included a combination of unequivocal and credible findings; consequently, in accordance with the ConQual guidelines for credibility, the confidence was reduced by another level. This ranking indicated that 1 qualitative synthesized finding had low confidence and 2 had very low confidence.

The illustrations supporting each of the findings are provided with citations and page numbers. In one study, the raw data were published as supplementary data.31

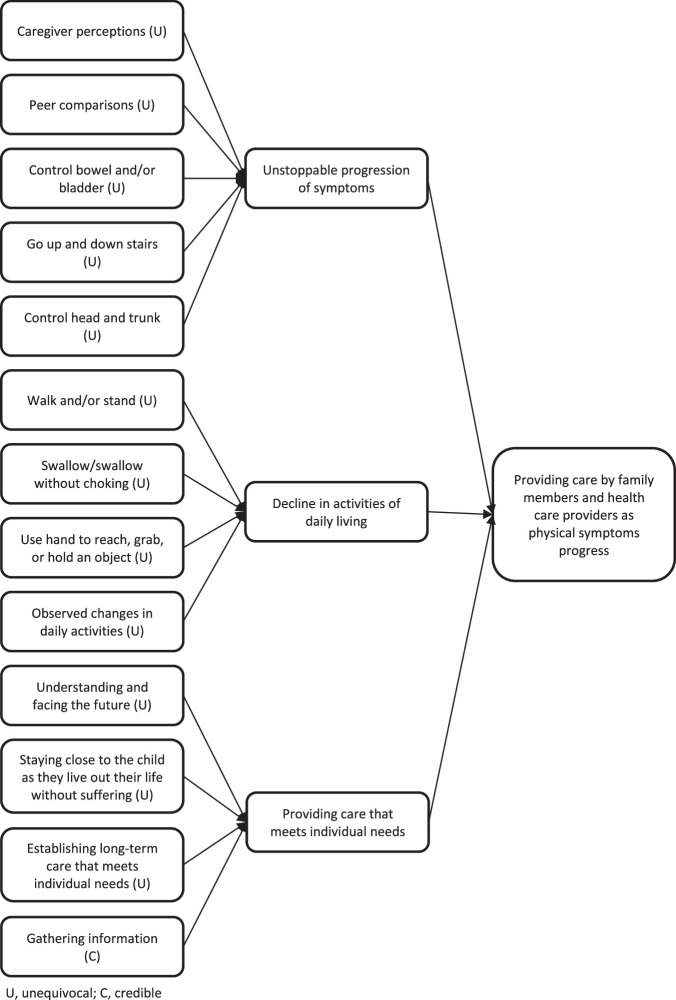

Synthesized finding 1: Providing care by family members and health care providers as physical symptoms progress

The first synthesized finding comprised 3 categories: unstoppable progression of symptoms, decline in activities of daily living, and providing care that meets individual needs. The synthesized finding was sourced from 13 findings across 4 studies (Figure 2).18,20,30,31 The levels of credibility for the findings in this synthesized finding were unequivocal for 12 and credible for 1.

Figure 2.

Synthesized finding 1: Providing care by family members and health care providers as physical symptoms progress

The target diseases were progressive diseases, with physical symptoms worsening even with currently available treatments and supportive care. As the symptoms progressed, patients’ difficulties with activities of daily living (ADLs) and social activities that they previously performed had a significant impact on them and their family members. However, even within this context, families were still searching for ways to implement medical care and utilize social resources in accordance with the individual needs of the patients.

Category 1.1: Unstoppable progression of symptoms

This category was formed from 5 unequivocal findings sourced from 2 studies.30,31 The focus of this category was on the change in the patient’s loss of physical mobility as symptoms progressed. The progression of leukodystrophy causes gradual onset of symptoms and loss of physical function; however, the degree of symptom progression varies with the disease type. Patients’ parents or family members noticed the first minor symptoms and changes that appeared, and sought medical attention.

She developed a small tremor in her hands when she would reach for things. And for me, my parent radar went off and I just felt like something was going on, so I sought a new pediatrician who would listen to my concerns. 31 (supplementary data) (from caregiver)

However, even with medical attention and the best possible treatment, it is difficult to resolve all of the symptoms of leukodystrophy. Patients with MLD lost the ability to sit up and had to use diapers for all their excretion.

Then in grade 2, he lost upper body control, he started falling over in the booster seat. So we’d go around a turn and he’d fall over. So, we had to put him back into a car seat. 30 (p.5) (from caregiver)

By the end of grade 2, he was wearing diapers full-time because he was having accidents all the time. 30 (p.5) (from caregiver)

Category 1.2: Decline in activities of daily living

This category was formed from 4 unequivocal findings sourced from 2 studies.30,31 Progression of symptoms leads to difficulty with ADLs. Parents or family members observed their child’s gradual loss of ability to walk and ingest food. Of particular importance was the loss of ADLs previously acquired. Patients grew and developed until symptoms associated with substrate accumulation become apparent. Afterward, ADLs quickly declined after the onset of symptoms.

She started choking on liquids because she couldn’t swallow very well. 30 (p.5) (from caregiver)

She walked with a walker for a very short time. So between 3, 4 months later, she quit [walking] altogether. 30 (p.5) (from caregiver)

The effects of leukodystrophy are not limited to physical function; they also lead to cognitive decline. Patients with juvenile MLD experienced a loss of ability as their symptoms progressed after previously acquiring reading, writing, and calculation skills, because symptom onset was after school age.

In first grade, he was top of his class in whatever they were teaching him in math, top of his class… Third grade, just all of a sudden, he couldn’t add. 31 (from caregiver)

Category 1.3: Providing care that meets individual needs

This category was formed from 4 findings (3 unequivocal, 1 credible) sourced from 2 studies.18,20 Parents hoped that their children’s suffering was minimized as much as possible; therefore, they adjusted their lives to spend as much time as possible by their child’s side and made decisions about accepting invasive medical procedures.

Right now, the most important thing to me is being close to my child. As soon as I get home from work, I cuddle with him and sing to him. I don’t know how much time we have left, so I want to be by his side as much as possible telling him that “I’m here, it’s OK.” 18 (p.31) (from parent)

We signed a paper saying not to perform emergency life-saving procedures. I’ve accepted the fact that I can’t do anything for the child. But I don’t want my child to experience that sort of suffering, not even a little bit. My wish is for the child to move on comfortably—I don’t want to show them my pain.18 (p.32) (from parent)

Parents also collected information about their child’s disease. They attempted to understand the disease with the limited information they had, as it was a rare disease with limited information available.

We got this paper and it was the seminal paper written on ALD (adrenoleukodystrophy) in 1997 by Dr Hugo Moser and that was really good. That gave us … that gave me the details. 20 (p.1332) (from parent)

Because the symptoms associated with leukodystrophy are diverse and vary by disease type and patient, planning comprehensive care based on the disease alone is difficult. Parents provided information about their children and collaborated with health care providers to ensure that their children received appropriate care.

I wrote a note to let them know that the child had trouble falling asleep. After that, the relatively veteran nurses who always cared for him refrained from disturbing his sleep when coming to check on him, measure his temperature, scan barcodes, etc. I was very moved to learn that they let the child sleep deeply, even when it meant facing professional risk by bending the rules. 18 (p.33) (from parent)

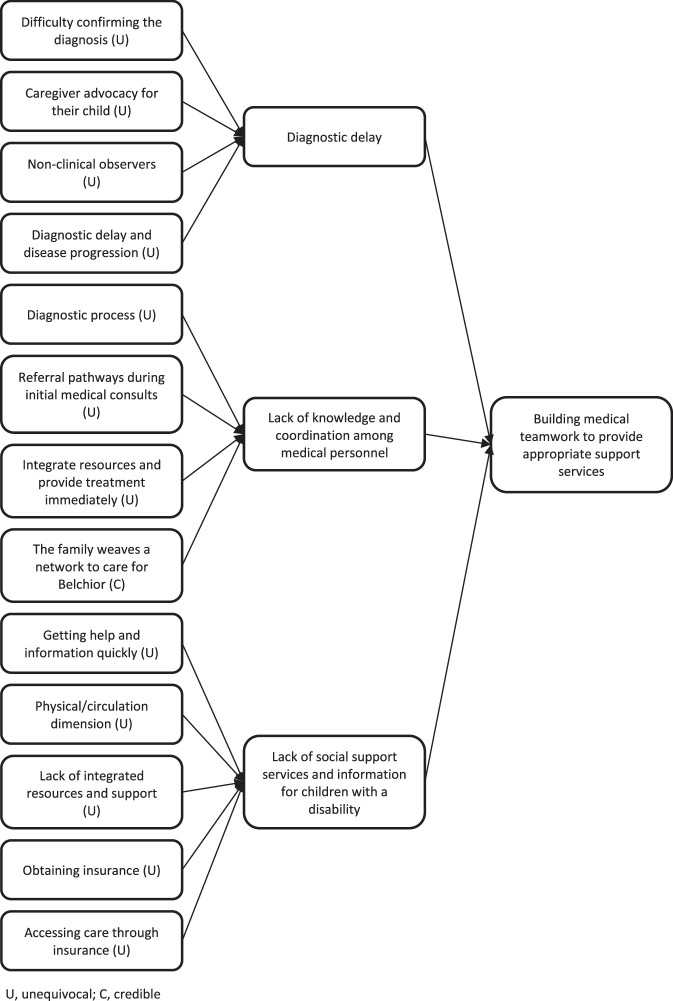

Synthesized finding 2: Building medical teamwork to provide appropriate support services

The second synthesized finding comprised 3 categories: diagnostic delay, lack of knowledge and coordination among medical personnel, and lack of social support services and information for children with a disability. The synthesized finding were sourced from 13 findings across 8 studies (Figure 3).13,17–19,31–34 The levels of credibility for the findings in this synthesized finding were unequivocal for 12 and credible for 1.

Figure 3.

Synthesized finding 2: Building medical teamwork to provide appropriate support services

Diagnosis of leukodystrophy in patients took a long time because few doctors specialize in these rare diseases. Delayed diagnosis led to delayed therapeutic intervention and to progression of irreversible leukodystrophy. Patients and their families complained about the lack of knowledge of these rare diseases among health care providers. This led to lost opportunities for referrals to appropriate medical departments and care. Furthermore, the lack of an adequate system for providing information on social support services for children with disabilities revealed that families must search for information on their own.

Category 2.1: Diagnostic delay

This category was formed from 4 findings sourced from 3 studies.17,31,33 As a rare disease, leukodystrophy is difficult to diagnose. Even when a patient was attended to by a health care provider, proper diagnosis was often delayed. Parents or family members were skeptical about the diagnosis of their children and visited multiple physicians.

The physician thought he had ADHD and suggested some medication … He [the child] took the medication for 3 months, but his condition got worse; he lost his balance and easily fell down. He couldn’t see and sometimes couldn’t talk. I was terrified. After a series of neurological examinations and genetic analysis, he was finally diagnosed with ALD. 17 (p.199) (from parent)

So first, we went to the midwife and she said just to wait a bit longer. And then we went to the doctors and asked for a referral to see a physiotherapist. We eventually got a referral. And then the physiotherapist said that she had hypermobility syndrome…and the physio decided there was no treatment needed. And then I decided to pay for a private physio because I wasn’t happy with what the NHS physio said. I didn’t think it was quite right… then she started having physiotherapy through the NHS because they accepted that she was late walking… And then in the end, I still wasn’t happy. I thought there wasn’t something quite right because she still wasn’t walking. She wasn’t balancing. Her speech is a little bit delayed. So, we went to a private neurologist. 31 (supplementary data) (from caregiver)

Parents were not the only ones to notice symptoms when they started to appear. Other adults involved in the child’s life, such as a nursery teacher, noticed minor changes and recommend that the parents seek medical attention.

We requested the help of a nursery teacher [child’s name] has had. And she agreed to observe [child’s name] for half a day… we had the chat with the nursery teacher after she’d observed [child’s name] for that half a day, and she had words to us. And I will never forget them… ‘There’s something very wrong and you need to get somebody to have a really good look at her.’ And it was from that point that she then contacted the GP, our local doctor…I think it was within three days, [child’s name] was having a CT scan at the local hospital 31 (supplementary data) (from caregiver)

In the case of leukodystrophy, symptoms progress rapidly even before diagnosis. Parents were left with the uncertainty of why their children gradually lost the ability to perform activities that they could previously execute.

…he was speaking very well compared to others his age. He was very talkative and fine at two. At that age then he began to slow down speaking and slowly but surely losing all his ability. He was really quite well developed at two years of age as a little boy but over the course of about nine months all that disappeared on him. From that age of two to three where he lost his physical ability before his mental faculties was very traumatic for him and for us and physically painful and emotionally upsetting and confusing and distressing for [Name] and for us. It was terrible to watch him. 33 (p.5) (from parent)

Category 2.2: Lack of knowledge and coordination among medical personnel

This category was formed from 4 findings sourced from 4 studies.13,18,31,32 Because the 3 diseases included in this review are rare, health care providers may not have sufficient knowledge of them. Due to this lack of knowledge, patients received a delayed diagnosis or lost the opportunity to receive appropriate care.

The doctor sent us to an endocrine doctor, which told us, “Have him drink more milk. He’s just on the slower scale. He’s just got developmental and cognitive delays.” So, time went past and… we kept seeing more problems, like with motor skills. He was real clumsy, things like that. So, I went into the doctor’s office since it was a new doctor and laid down the medical records…He reviewed the notes and we started from there, going through even allergy specialists, you name it. It took us, it seemed forever, to get into neurology. 31 (supplementary data) (from caregiver)

In addition, patients with these diseases, which can present with a variety of symptoms, were followed up in multiple departments. Patients’ families complained about the lack of cooperation between the departments.

At the very beginning, we took our child to XX Psychosomatic Clinic. There, they wrote us a referral to a neurologist who performed an exam. From the eye clinic, we were introduced to the head of XX Eye Clinic. So we came and went many times. Finally, we were dealing with National Taiwan University Hospital. None of these doctors are in the same place. If they were in the same location, they could discuss the child’s symptoms with each other. 18 (p.32) (from parent)

Within the existing system to support patients and their families living at home, there were problems with coordination among medical personnel and adjusting to the family’s desired care and lifestyle. The patient’s parents wanted the doctor to visit their home to ensure not only the patient’s health, but also that of the entire family.

[…] I needed the [ESF(Estratégia Saúde da Família; Family Health Strategy)] doctor twice to come here to see my son. […] I asked the doctor to come again on a different day. He said: “Wasn’t he going to make an appointment?”. He sent a nurse. Now doctor has changed, a doctor working there, female doctor, I do not remember her name. Even without inviting her, she came here to visit him. So I think just like him [the doctor], he has an obligation to visit, mainly, a patient like him, and it was a failure, because if it is a “family health”, then they need to visit the houses. We needed him, but he didn’t come to help us, he told me to take him to the public hospital and he would provide the transport… in a way to say do not come. We did provide the transport anyway to take him. 32 (p.162) (from parent)

Category 2.3: Lack of social support services and information for children with a disability

This category was formed from 5 unequivocal findings sourced from 4 studies.17–19,34 As the disease progressed, patients with leukodystrophy experienced a decline in physical function and various handicaps in their daily lives. Patients’ primary caregivers were their parents who are responsible for their daily care. Parents sought ways to care for their children and social resources for better support.

I was carrying the child in my arms to the bath and washing them; I didn’t know at the time that I could purchase a shower chair if I requested one. Everyone taught me about the physical transformation and mucus problems, so I knew how to handle such things. Thinking about it now, the techniques everyone (treatment nurses) taught me were invaluable. I wish I had learned about them sooner. 18 (p.33) (from parent)

Children with disabilities received more appropriate care when integrated support was provided through collaboration among multiple departments and professions rather than support from each department independently. Some family members saw a physician, but were recommended to see a physical therapist, speech therapist, or other professional in the rehabilitation department.

This was the second time. The first one I went there and thanks God we got a speech therapist and a physical therapist through the child’s prosecutor. But they only have a limited amount of sessions, and when they end we have to start the process again. When they were ending I took the reports of the physical therapist and the speech therapist. I took them there and they said: No, now they are sending you to the rehabilitation center, they have the conditions to care for you. 34 (p.4) (from parent)

However, patients and parents were not fully informed about support and social resources. The parents actively tried to utilize social resources. In particular, parents wanted society as a whole to address the issue of who is responsible for the care of children after the death of a parent.

We didn’t obtain much assistance from the government and the [Taiwan Foundation for Rare Disorders]. I hope these two organizations can take ALD more seriously, so we don’t need to seek the resources ourselves. I am worried about who will take care of my son after I am gone. I get so scared every time I think about this issue. What can I do? Nobody can answer my question, not even God. The government should do something about it. The government should sponsor some community programs to take care of children like my son. 17 (p.202) (from parent)

In addition, insurance coverage is an issue for patients with leukodystrophy. The treatment of rare diseases, such as leukodystrophy, is evolving, and the development of new drugs and use of existing drugs are being considered. However, parents were troubled by the lack of insurance coverage and the possibility of not receiving high-cost treatment based on the latest findings.

For her, you might need a drug that is proven for cystic fibrosis, but we know for a fact that she has some of the same lung issues, but we may not be able to get the insurance to cover that equipment or that drug because we don’t have the background that says, “Oh yeah, they will work for MLD too.” 19 (p.5) (from parent)

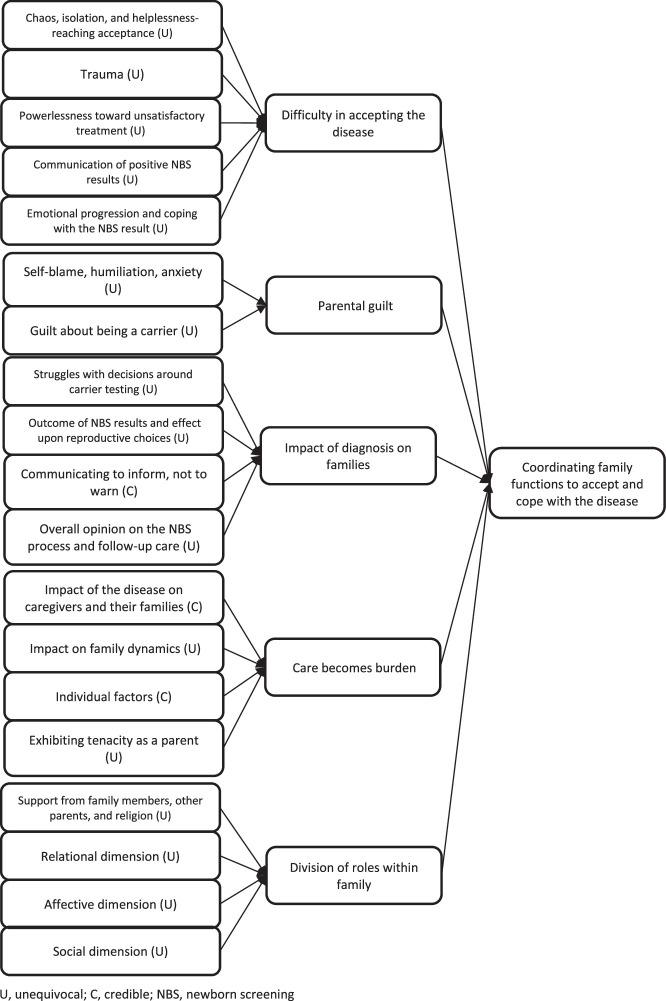

Synthesized finding 3: Coordinating family functions to accept and cope with the disease

The third synthesized finding comprised 5 categories: difficulty in accepting the disease, parental guilt, impact of diagnosis on families, care becomes burden, and division of roles within family. These were sourced from 19 findings across 8 studies (Figure 4).13,16–20,33,34 The levels of credibility for the findings in this synthesized finding were unequivocal for 16 and credible for 3.

Figure 4.

Synthesized finding 3: Coordinating family functions to accept and cope with the disease

Receiving a diagnosis of one of the target diseases affected family functions, first, because the diseases lead to severe disabilities and second, because the diseases are hereditary. Inherited disease traits can also affect siblings and relatives. When patients were diagnosed, the family did not easily accept the diagnosis. Along with grieving for the patient’s future comes parental guilt. Additionally, caring for children with disabilities was a major burden on the family. Thus, the family member who received the diagnosis faced many difficulties. However, family members attempted to cope with those difficulties by sharing their roles and coordinating family functions.

Category 3.1: Difficulty in accepting the disease

This category was formed from 5 unequivocal findings sourced from 4 studies.16–18,20 For the parents, accepting their children’s disease was difficult. Moreover, parents were greatly impacted by the knowledge that their child, who previously had been developing to a certain degree, now had a progressive disease.

At the time, I didn’t know what ALD actually was, so I had no idea how the disease would progress. I watched a video on the Internet and thought, ‘I can never accept this.’ It was such a terrifying thing. The idea that our own child would change like that—we didn’t believe it at all… 18 (p.30) (from parent)

The first two weeks, I just laid in bed and cried. Between the hours of 7 and 7, I got up and I was on remote control … but as soon as the children were back in bed, I was curled up in my bed in the foetal position just thinking, this cannot be happening to my child. 20 (p.1331) (from parent)

Parents living with children with progressive diseases such as leukodystrophy experienced immeasurable anguish. The parents were grieving and considered dying alongside their children.

It was like hearing a life sentence. I was very sad and felt hopeless. The progressive deterioration caused by the disease was just like a volcano erupting; the disease spread and ruined the function of various body organs. It’s unbearable to me, both physically and spiritually. My son was hospitalized when the tragic earthquake hit Taiwan. I wished the hospital had been crushed by the earthquake, so my son and I could have died together. 17 (p.199) (from parent)

However, parents sometimes chose, as a coping mechanism, not to think too deeply about their children’s condition. Parents often received negative information at the time of diagnosis, such as the progression of symptoms, severity of disability, lack of curative treatment, and poor prognosis. In particular, being told of the diagnosis immediately after the birth of the child and before the appearance of symptoms, as in the case of a newborn screening, was a significant burden for parents.

I try not to think about the future too much because it freaks me out. I try to envision positive things, but if I think too far in the future sometimes my mind goes: What if he’s in a wheelchair? What if he’s dead? So I really don’t think about it very often. I guess that’s the way that I deal with it. 16 (p.5) (from parent)

Category 3.2: Parental guilt

This category was formed from 2 unequivocal findings sourced from 2 studies.17,18 MLD, ALD, and Krabbe disease are hereditary diseases, and parents are informed about this by their health care providers at the time of diagnosis. ALD, in particular, is a severe form of X-linked disease in boys that may be due to inheritance of the X chromosome from the mother. Therefore, mothers of children with ALD experienced guilt that their children had the disease.

Our oldest child had spoken with their teacher. ‘Why did Mom give me this sickness? I don’t want to die yet. My little brother can’t walk anymore and he can’t eat anything, he just lies in bed. It’s so scary.’ I ask him for forgiveness every day—(here the mother stopped speaking and was lost for words, with tears in her eyes and a blank expression)—I tell them I’m sorry that both of them got sick… 18 (p.31) (from parent)

Parents questioned why only the child had developed the disease and blamed themselves, as none of the child’s siblings or relatives had developed the disease.

My big sister has four sons, my second sister has six sons and my third sister has one son. All their sons are healthy. They are around 30 to 40 years old. Why me? Why do I have this bad gene? They (doctors) said it is a 50% of chance (to get the disease), but I think it’s 100%. What I have done? I feel guilty for bringing my sons to this world. 17 (p.200) (from parent)

Category 3.3: Impact of diagnosis on families

This category was formed from 4 findings (3 unequivocal; 1 credible) sourced from 4 studies.16,17,20,33 A diagnosis of leukodystrophy affected not only the patient but the entire family. Because of the hereditary nature of the disease, the patient’s siblings could also be patients or carriers. Therefore, while early diagnosis and follow-up is recommended, there was an additional conflict for parents to receive test results of siblings and family members.

If my daughter had the gene, the next generation needs to be protected from inheriting the disease by taking precautions. I know I should take her for a genetic testing to confirm the outcome. But I am scared of the outcome. 17 (p.200) (from parent)

However, a sibling’s new diagnosis from testing was not necessarily a negative experience. The parent said that, thanks to the patient, the early diagnosis allowed their sibling to receive early treatment and support in the future.

It did and it absolutely has I will be forever grateful for his early diagnosis thanks to his older sister. 33 (p.10) (from parent)

Category 3.4: Care becomes burden

This category was formed from 4 findings (2 unequivocal; 2 credible) sourced from 4 studies.13,16,18,19 Patients with leukodystrophy gradually lost physical function and required a variety of care in their daily lives, and many of the caregivers were their parents; for example, patients gradually required care such as suctioning of phlegm, tube feeding, and changing clothes. Parents and family members adjusted from their lives prior to the diagnosis to lives in which they focused on caring for the patient. However, parents and family members also had jobs and their own lives, and changing their lives was not easy. In this context, patient care was a burden and caused an emotional impact.

Showing up on time … completing assignments … or maintaining a job. 13 (p.1461) (from caregiver)

He [husband] went into a depression. We didn’t have any means of communication. I eventually got him to go to therapy, but even during his time in therapy, he wasn’t coming home and talking to me. It’s been a rough almost two years. 16 (p.5) (from parent)

In addition to the direct burden, parents also felt psychologically burdened by having to use their insurance for many treatments and support.

It goes back to walking around in somebody else’s shoes and trying to figure it out. It is not like we are trying to take advantage of anybody when we have kids with rare genetic illnesses. It is very difficult. 19 (p.5) (from parent)

Although parents were suffering, they also considered how to respond to the situation by taking care of their children and learning what to do while continuing to work.

I was taking care of the child full-time at that point. Although it was dreadful, I had to study up. There wasn’t anyone to help me at home. So I researched…and researched…and researched…that was the only way I could help him. Taking care of my child is everything. There is nothing else. 18 (p.31) (from parent)

Category 3.5: Division of roles within family

This category was formed from 4 unequivocal findings sourced from 2 studies.17,34 When parents and family members faced various challenges, they attempted to coordinate family functions and share their respective roles to cope with the challenges.

My husband and I quarreled with each other sometimes, but my husband has never blamed me for passing the gene on to my son. We became even closer after my son’s disease. We (participant and her husband) help each other. Even my mother-in-law has never blamed anyone. 17 (p.201) (from parent)

In particular, the roles were divided between husband and wife. By coordinating each other’s lives and taking care of their children, the parents felt they were a team.

It’s like that, she takes care during the day and I arrive at night… it’s like that in here, it’s like in a hospital, one day she sleeps with him, the other I sleep, we take turns. 34 (p.4) (from parent)

Discussion

The synthesized findings in this review revealed the experiences of parents and family members of patients with MLD and ALD. Although this review did not identify any articles in which the patients themselves were included, it is possible that family members were also patients or carriers, due to the characteristics of the hereditary disease.

Leukodystrophy is a progressive disease, and the importance of care for the progression of physical symptoms and severity of disability was evident in the review findings. A previous review of patients with similar rare diseases and their family members showed the burden of symptoms and treatment owing to disease progression.35 Another review noted the challenges of living as patient with a rare disease and the challenges in the health care system.36

Other findings from the current review suggested that medical personnel responsible for providing support to patients and family members lacked knowledge and cooperation, and that there was a need to create a system to provide appropriate support. It was evident that family members were trying to adjust roles to provide care for patients and to manage challenges and conflicts.

Patient care

Synthesized finding 1 (providing care by family members and health care providers as physical symptoms progress) indicates that the patient’s family members assemble support for the condition in the face of progressive symptoms and declining ADLs. The loss of functions previously acquired, a hallmark of leukodystrophy, had a profound impact on the family members.30,31 Information about disease progression and prognosis was painful for families. However, once the patient’s disease status was accepted, the family could create a system to provide care tailored to the patient’s individual condition and needs.18,20 These findings suggest that tailoring appropriate care to progressive symptoms contributes to the patient’s QOL.

Patients with leukodystrophy demonstrate cognitive and neurological decline and physical symptoms.1 Enzyme replacement therapy, HSCT, and gene therapy are currently being initiated for the treatment of leukodystrophies37; however, large proteins are restricted by the blood–brain barrier, and enzyme replacement therapy cannot resolve central nervous system symptoms.1 HSCT is associated with risk of complications and is expected to be effective only before the onset of symptoms. Although gene therapy is still in its infancy, it is expected to slow demyelination and maintain cognitive function and motor development.38 Expert consensus on the application and effectiveness of these treatments is being developed, and the accumulation of information by registries is being considered.39 Meanwhile, supportive care is important for patients after the progression of symptoms. Previous studies of patients with MLD and ALD in Japan have shown examples of supportive care through enteral nutrition, tracheostomies, and home ventilators.4 Therefore, in supporting patients with leukodystrophy and their families, it is important to tailor support to their individual needs.

Medical system

Synthesized finding 2 (building medical teamwork to provide appropriate support services) indicates an urgent need to establish a support system for patients with leukodystrophy, as families navigate 3 challenges identified within our categories: delayed diagnosis, lack of knowledge of medical personnel, and lack of support services. Among leukodystrophies, the speed of progression varies with the type of disease. Patients and family members experienced discomfort and visited a doctor, but a diagnosis was not immediately reached.17,33 While parents noticed changes in their child, in some cases, child care workers who were involved with the child on a regular basis also noticed changes.31 To reduce the delay in diagnosis, a diagnostic algorithm combining imaging and genetic testing has been proposed for early diagnosis and treatment.40,41 The inclusion of these leukodystrophies in newborn screening has been considered, with Krabbe disease a target disease in some areas.10 Early diagnosis after consultation is expected to lead to more treatment options that can halt disease progression and reduce the psychological burden on the family.

Because leukodystrophies are rare diseases, there are few medical professionals who specialize in them. The lack of experts leads to delays in diagnosis and provision of appropriate treatment.33,42 In addition, lack of knowledge on the part of health care providers could lead to patient and family concerns.35 Furthermore, as the disease progresses, patients with leukodystrophy have reduced ADLs and require multiple supports. Patients and families are required to select and combine these support services. There is also a challenge to build relationships between supporters and health care providers involved in patient care.42 Supporters include therapists (eg, physical therapists), home living support positions (eg, home care workers for patients), and nursery teachers and caregivers for day care services in the community. In addition to physicians and nurses, patients with leukodystrophy need support from these professionals, as various types of care are required as the disease progresses.

It is necessary to promote understanding of leukodystrophy across the medical profession. Many health care providers have no experience with patients with leukodystrophy, and the lack of knowledge may affect a trusting relationship.13,31 This lack of knowledge extends to other lysosomal diseases besides leukodystrophy.35 For patients and their families to receive appropriate care, there must be a system in which leukodystrophy specialists and other health care providers can work together. Proper coordination among supporters leads to smooth service delivery. Patients present with a wide variety of symptoms, requiring visits to multiple departments and a combination of services, which can be burdensome for families.18 It results in both a procedural and financial burden to obtain services.42 Therefore, it is desirable to have a service coordinator who plans comprehensive support for patients and their families.

Family support

Synthesized finding 3 (coordinating family functions to accept and cope with the disease) indicates that families need support through the process of accepting and coping with the impact of the diagnosis and the burden of caregiving. Accepting the diagnosis of leukodystrophy in children is difficult for parents and family members.16–18,20 The regression of a child’s condition is unacceptable, especially when prior to the onset of the disease, the child had grown and developed almost identical to that of a child without leukodystrophy. Moreover, being told that the disease is hereditary makes the parents feel guilt.17,18 However, there were positive aspects, such as the patient’s diagnosis leading to an early diagnosis in their siblings.33 Therefore, it is important to address the family’s psychological needs in cooperation with medical specialists and genetic counselors to provide support.

The impact of the diagnosis and the care burden on parents and caregivers should be fully considered. A survey of caregivers of patients with MLD revealed that the care of the children affected not only the health of the caregivers, but also their social and family functioning.43 Leukodystrophies also affect the health and reproductive planning of parents and siblings. Therefore, in addition to the patient, supporters (eg, nurses, therapists, care workers, social workers) are expected to assess the burden on caregivers and family members, and to offer additional support or resources if necessary.

In addition, the burden of caring for a child with a disability is significant for the family, compelling them to make changes to their lifestyle.13,16,18,19 A diagnosis of leukodystrophy may cause parents to stop working or lead to a deterioration in their marital relationships.43 However, some families changed roles and made adjustments to their lives as a family, including their children with leukodystrophy.17,34 Supporters are expected to provide appropriate information and help coordinate family functions so that the family can accept the disease and live with the patient at home.

Limitations

One limitation of this review concerns the quality of the studies. According to the JBI critical appraisal checklist for qualitative studies,21 the methodological quality of the included studies was not high, and one study with missing methodological descriptions was included.20 Furthermore, the credibility of the synthesized findings were low or very low. This was due to many of the papers missing adequate descriptions of the methodology, and items related to the trustworthiness of qualitative research. As a result of the poor quality of the studies, the confidence level of the recommendations produced in this review may be low. In addition, some studies were translated into Japanese and English, which could have led to a loss of meaning and incorrect interpretation; however, the translations were done by native speakers of each language, thereby mitigating the impact of potential translation issues.

Another limitation is that no papers on patients with Krabbe disease were identified. Of the 3 diseases covered by this review, Krabbe disease is believed to be the least prevalent, and there is a lack of research on the experiences of patients and their families.

Furthermore, the protocol for this review included family members as well as patients, but all of the included studies involved parents or family members. Depending on the form of leukodystrophy, patients’ cognitive function declines quickly after disease onset,2 thus making it difficult for them to participate in qualitative research through interviews. However, some female carriers of ALD and patients with Addison disease can speak; therefore, further investigations are needed.

Conclusions

The synthesis of the studies in this review provided insight into the experiences of families who have a member with MLD or ALD. In supporting patients and their families, this review suggests that it is necessary to provide appropriate care to patients, develop medical systems to make this possible, and provide support to families.

The methodological quality of the studies included in the review and the description of the articles were lacking. As a result, the confidence of the synthesized findings is low or very low. Therefore, it is necessary to exercise caution when interpreting the recommendations that follow.

Recommendations for practice

These recommendations were developed based on the findings of this review and graded based on JBI guidance.44 Grade “A” indicates a strong recommendation and Grade “B” indicates a weak recommendation Three aspects of support for patients with MLD or ALD and their families were identified as patient care, medical system, and family support there are 6 recommendations for practice:

To maintain patient QOL, each patient’s needs should be identified by health care providers and the plans of care should be individualized based on the needs of the patients and their families. The health care provider and family should continue to discuss supportive care and end-of-life care so that this can be introduced at the appropriate time. (Grade B)

Medical specialists, health care providers, and other care providers, such as childcare workers or teachers, should collaborate and provide information to patients and their families to facilitate early diagnosis and early treatment. (Grade B)

Screening of newborns and a diagnostic algorithm that combines imaging and genetic testing is suggested to improve early diagnosis. (Grade B)

Education about leukodystrophy is particularly important for health care providers involved in pediatric care. Health care providers in pediatric care should receive education about the signs and diagnosis of leukodystrophy, as well as the care requirements of individuals diagnosed with leukodystrophy and their families. (Grade B)

Coordinated care from a multidisciplinary team is required. A coordinator who works with the patients and the families to assist with the planning of comprehensive care and support is recommended. (Grade B)

Ongoing professional support and counseling for parents and other family members is suggested to provide emotional support to the families of children with leukodystrophy. (Grade B)

Recommendations for research

Based on the challenges encountered in this systematic review, the following 4 recommendations for future studies were developed:

To clarify the quality of the qualitative research, the philosophical background, researchers’ attributes, influence of the researcher on the research, and consistency between methodology and analytical method should be clearly stated.

Future studies on the experiences of patients with Krabbe disease and their families should be conducted.

Studies should be conducted with patients who are able to talk about their experiences, such as patients with adrenomyeloneuropathy, Addison type and female carriers of ALD, and adult-type MLD.

Studies should be conducted that collect longitudinal data on the experiences of patients with leukodystrophy and their families, rather than cross-sectional or retrospective studies. It is hoped that longitudinal studies will include identifying changes in experience with novel therapeutic interventions, such as gene therapy.

Acknowledgments

Osaka University Library for assistance in developing the search strategy.

Funding

This work was supported by Takeda Japan Medical Office Funded Research Grant 2021, which assisted with the collection of articles and language editing for this protocol, and by JSPS KAKENHI (Grant Number JP22K17513), which assisted with translation from other languages into English, English editing of manuscripts, and Open Access fees.

Author contributions

YK conceptualized the concept for the review and contributed to the methodology and writing of the original draft. SU conceptualized the concept for the review, contributed to the methodology, and reviewed the draft of the review. MY contributed to the methodology and reviewed the draft of the review. NS supervised the project and reviewed the draft of the review.

Appendix I: Search strategy

MEDLINE (Ovid)

Search conducted: November 18, 2022

| Search | Query | Records retrieved |

|---|---|---|

| #1 | exp lysosomal storage diseases/ or exp peroxisomal disorders/ | 33,084 |

| #2 | (leukodystrophy or metachromatic or Krabbe or adrenoleukodystrophy).ti. or (leukodystrophy or metachromatic or Krabbe or adrenoleukodystrophy).ab. or (leukodystrophy or metachromatic or Krabbe or adrenoleukodystrophy).kw. | 7610 |

| #3 | 1 or 2 | 37,145 |

| #4 | (patient or patients or participant or participants or family or families or mother or mothers or father or fathers or parents or grandparent or grandparents or grandfather or grandfathers or grandmother or grandmothers or child or children or sibling or siblings or carer or carers or caregiver or caregivers).ab. | 9,350,665 |

| #5 | 3 and 4 | 17,537 |

| #6 | (life or living or well-being or experience* or care or challeng* or advantag* or disadvantages or attitude or emotions or stress or frustration or satisfact* or dissatisfact*).ab. | 5,559,623 |

| #7 | exp Genetic Therapy/ or exp Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation/ or Bone Marrow Transplantation/ or Cord Blood Stem Cell Transplantation/ or gene therapy.ab. or hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.ab. or bone marrow transplantation.ab. or cord blood stem cell transplantation.ab. | 183,460 |

| #8 | 6 or 7 | 5,708,536 |

| #9 | 5 and 8 | 4474 |

CINAHL Plus (EBSCOhost)

Search conducted: November 18, 2022

| Search | Query | Records retrieved |

|---|---|---|

| S1 | (MH “Lysosomal Storage Diseases+”) or (MH “Peroxisomal Disorders+”) | 3531 |

| S2 | TI(leukodystrophy or metachromatic or Krabbe or adrenoleukodystrophy) or AB(leukodystrophy or metachromatic or Krabbe or adrenoleukodystrophy) | 788 |

| S3 | S1 or S2 | 3972 |

| S4 | AB(patient or patients or participant or participants or family or families or mother or mothers or father or fathers or parents or grandparent or grandparents or grandfather or grandfathers or grandmother or grandmothers or child or children or sibling or siblings or carer or carers or caregiver or caregivers) | 2,477,792 |

| S5 | S3 and S4 | 1955 |

| S6 | AB(life or living or well-being or experience* or care or challeng* or advantag* or disadvantages or attitude or emotions or stress or frustration or satisfact* or dissatisfact*) | 1,731,483 |

| S7 | (MH “Gene Therapy”) or (MH “Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation”) or (MH “Bone Marrow Transplantation+“) or AB(“gene therapy” or “hematopoietic stem cell transplantation” or “bone marrow transplantation” or “cord blood stem cell transplantation”) | 21,668 |

| S8 | S6 or S7 | 1,747,988 |

| S9 | S5 and S8 | 736 |

APA PsycINFO (EBSCOhost)

Search conducted: November 18, 2022

| Search | Query | Records retrieved |

|---|---|---|

| S1 | TI(“lysosomal storage disease*” or “peroxisomal disorder*” or leukodystrophy or metachromatic or Krabbe or adrenoleukodystrophy) or AB(“lysosomal storage disease*” or “peroxisomal disorder*” or leukodystrophy or metachromatic or Krabbe or adrenoleukodystrophy) or KW(“lysosomal storage disease*” or “peroxisomal disorder*” or leukodystrophy or metachromatic or Krabbe or adrenoleukodystrophy) | 914 |