Abstract

Covalent organic frameworks (COFs) have much potential in the field of analytical separation research due to their distinctive characteristics, including easy modification, low densities, large specific surface areas and permanent porosity. This article provides a historical overview of the synthesis and broad perspectives on the applications of COFs. The use of COF-based membranes in gas separation, water treatment (desalination, heavy metals and dye removal), membrane filtration, photoconduction, sensing and fuel cells is also covered. However, these COFs also demonstrate great promise as solid-phase extraction sorbents and solid-phase microextraction coatings. In addition to various separation applications, this work aims to highlight important advancements in the synthesis of COFs for chiral and isomeric compounds.

Keywords: : capillary electrochromatography, covalent organic frameworks, gas chromatography, high-performance liquid chromatography, solid-phase microextraction

Graphical abstract

Plain language summary

Executive summary.

Covalent organic frameworks (COFs) have emerged as ideal candidate materials for advanced applications in analytical separation science due to their high porosity, large surface areas, well-defined pore structures, tunable pore sizes, adjustable surface properties and excellent stability. The design principles (topologies and linkages, building blocks), synthetic methods and functionalized strategies (bottom-up, in situ and postmodification) of COFs make them versatile for application purposes.

Types of COFs

The 2D or 3D crystalline structures of COF materials are well-defined and predictable due to the generation of stiff covalent interactions through a variety of synthetic organic processes between the structural units.

The production of COFs has been steadily increasing with various internal functionalizations, such as triazine, imine, hydrazone, borazine, azine and so on, as their presence and potential applications have been thoroughly explored.

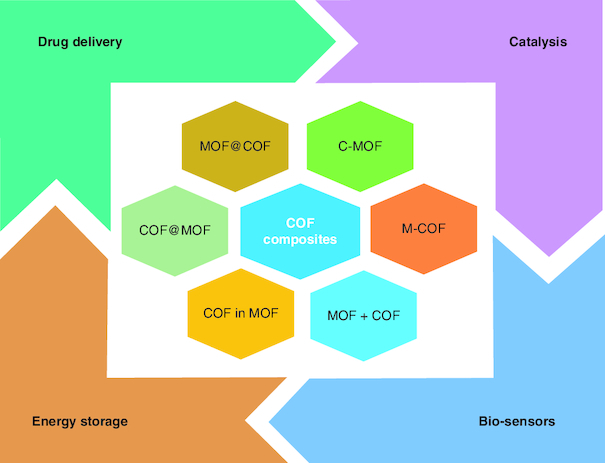

The insertion of the secondary building units of MOFs into the building units of COFs will result in targeted products with traits from both MOFs and COFs. Those formed components will work in concert to provide multifunctional properties for particular uses such as energy conservation, photodynamic energy conversion, heterogeneous catalysis, adsorption and separation, detecting and semiconducting capabilities.

Applications

The potential applications of functional COFs were highlighted including adsorption and separation, heterogeneous catalysis, fluorescence, conductivity and solar cells.

Pharmaceutical applications: COFs are promising in separation science from sample pretreatment (solid-phase extraction and solid-phase microextraction) to chromatography (gas chromatography, high-performance liquid chromatography, capillary electrochromatography) for diverse targets. The unique properties of COFs make them good candidates as sorbents in solid-phase extraction. Several specific, nonhydrophobic mechanisms including hydrogen bonding, electrostatic attraction and π–π electron donor–acceptor interaction are reasons for its excellent extraction performance. Large surface areas and good thermal and chemical stability make COFs ideal candidates for the stationary phase for gas chromatography. Chiral COF-bound capillary columns provide better resolution and larger separation factors than commercial chiral capillary columns. The chiral microenvironment, π–π interactions, hydrogen bonding and van der Waals interactions play significant roles in chiral gas chromatography. The unique structures, good solvent stability and large surface area also make COFs potentially useful in high-performance liquid chromatography.

Environmental applications: COFs are prominent candidates in the area of water treatment, such as the removal of salts, dyes, metal ions and other organics. The applications of COF-based nanofiltration membranes mainly focus on the removal of dyes and salts from water.

COFs in drug delivery: Combining outstanding thermal and chemical stabilities, structural designability and inherent porosity in one material, COFs have shown their potential in biorelated applications. Recent focus has been devoted to exploring COFs for antibacterial activity and drug delivery. The basic concept is that skeletons have been developed for docking specific functional sites to trigger interplay with cells that cause antibacterial activity or target cancer cells, and the pores can be designed to load specific drugs for delivery into cells.

In light of their extraordinary performance and numerous applications, including in the preservation and extraction of gases, highly hydrophobic interactions, catalytic processes, transformation of energy, energy conservation, optoelectronics and pharmaceutical operations, demand for nanoporous materials has grown dramatically over the last century. Chemistry can be utilized to create an extensive range of porous substances [1]. It comprises a basic discipline of science that allows the development and production of novel porous compounds and provides a description of the molecular foundations of a wide range of physicochemical attributes and purposes at distinct atomic stages and duration levels. Crystalline molecules are distinctive in that they can sustain broad-term molecular arrangements and provide a unique molecular arena or platform for starting and controlling a variety of linkages and collaborates that make up the processes of various molecular assemblies [2].

Researchers have made great strides in creating a wide range of chemical design principles, from broadened (1D, 2D and 3D) to distinct (zero-dimensional; 0D) frameworks [3]. These have been achieved by assembling construction elements in a variety of ways, ranging from inorganic [4] to pure organic [5] components, from disorganized to organized arrangements [6] and from nonporous to porous natures [7]. Nature's capacity to combine atoms into intricate systems with sophisticated functions served as the inspiration for this work. Various techniques for connecting materials, ranging from minimal interactions (e.g., stacking at π–π) to strong connections (e.g., covalent linking), have been employed to skillfully assemble the components of these designs. Reticular chemistry, which employs topologically designed components, was introduced as a means of producing these porous materials.

Most covalent organic frameworks (COFs) create and assemble their skeletons from regularly ordered stiff π components, which result in topologically ordered columnar π combinations. These columnar π arrays allow charge-carrier mobility to be facilitated by prearranged paths and provide intracolumn electronic coupling, and can therefore be used as semiconductors. One benefit of using ordered COF structures for sensors, bioprobes, optoelectronics and photovoltaics is that their luminous segments can be prearranged in space [8].

The special combination of organic functionality and crystallinity in COFs gives these materials a wide range of beneficial features [9]. One of the most researched characteristics of COFs is porosity. Their porosity is extremely adjustable, and COFs with micropores and mesopores have been observed. COFs have promise for use in gas preservation purposes due to their huge surface areas and low densities. COFs have large storage capabilities for significant gases such as methane, hydrogen and carbon dioxide. Hazardous gases like ammonia can be captured and stored using COFs. For example, ammonia is a frequently used chemical that must be carried properly due to its caustic and dangerous nature. Since ammonia is a Lewis base, it can be efficiently trapped by interacting with Lewis acidic groups, for instance, the boron atoms in boroxine or COFs with boronated ester bases.

COFs may load a variety of compounds into their nanopores in addition to adsorbing gas molecules [1]. For instance, imine-based COF-Lan Zhou University (COF-LZU1) can produce palladium (Pd) COF-LZU1 by loading Pd ions through its apertures through the synergistic interactions between nitrogen atoms in the COFs and Pd ions. A heterogeneous catalytic system is created by the Pd ions on the COF surfaces, that are catalytically engaged and approachable to both the substrate and the reactant. Cross-linked sulfonated polyether ether ketone-based covalent organic proton exchange polymeric membranes have been created and are employed in fuel cells [10]. These membranes serve as a divider of both electrodes and as an electrolyte for carrying protons in fuel cells to provide proton conductivity.

COFs are used in environmental applications including membrane separation, adsorption and detection of a variety of contaminants, including radionuclides, heavy metals and hazardous organic contaminants [11]. Due to a variety of characteristics, such as their maximum Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) surface area and aperture size with high stability and good crystallinity, COFs have become a dominant force in the field of separation research [12]. In separation techniques like solid-phase extraction (SPE) and solid-phase microextraction (SPME), COFs such as hydrazone COFs, covalent triazine frameworks (CTFs) and those that are imide-linked, are preferred.

Drugs with low solubility or transportability across biological membranes can also be transported using COFs as nanocarriers [13]. COFs can be used for controlled drug delivery because of their wide pores and large surface areas, which facilitate potential loadings and effective delivery regulation. For chromatographic methods including high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), gas chromatography (GC) and capillary electrochromatography (CEC), COFs can be employed as stationary phases. HPLC uses chiral stationary phases (CSPs) called chiral COFs (CCOFs) to separate racemic mixtures. Effective chiral separation can be achieved by securely immobilizing several biological molecules (amino acids, peptides and enzymes) into achiral COFs that are enriched with chirality [14].

History

Metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) were the initial group of porous materials produced utilizing reticular chemistry [15]. This modular MOF concept was first presented in the English language edition of Angewandte Chemie in 1985. The increased number of journals in this field of chemistry has grown enormously and will likely persist in the decades that follow. After Yaghi et al. released the first discoveries of their investigations in 1995 and gave this class of compounds the term MOFs, the field of chemistry experienced a surge in publications. Organic connectors having functional groups eligible for complexing metal atoms or aggregates as linking components can be used to make these zeolite mimics (MOFs) quickly and easily.

Ten years later in 2005, Yaghi et al. provided the first description of COFs [16]. The creation of porous, crystalline COFs is done with simple elements (H, B, C, N and O), which are recognized to make powerful covalent bonds in widely popular and practical components like diamond, graphite and boron nitride. These COFs, which hold strong covalent connections between their pure organic groups, can be referred to as organic zeolites.

Compared with traditional porous materials like zeolites and activated carbons, MOFs and COFs provide several benefits, such as easily modifiable frameworks, large surface areas, large pore sizes and established and tunable geometries [17]. They therefore hold great promise for many uses, such as catalysis [18,19], gas adsorption and differentiation [2,20], detection [3,21] and drug delivery [2].

Due to the association of coordination linkages between metal ions/clusters and organic linkers, MOFs are special materials that incorporate both inorganic and organic components. Contrarily, COFs are huge, 2- and 3D organic frameworks that are constructed exclusively of simple elements (H, B, C, N and O) using powerful covalent connections [1]. Compared with MOFs, COFs have seen remarkable development and demonstrated tremendous potential for functional investigation. This is because they have minimal mass densities, good heat stabilities and persistent porosity since they are made of light-massed elements joined by rigid covalent bonds.

Compared with inorganic zeolites, COF materials have various advantages in addition to lower densities. The repeated creation of Si-O-Si and Si-O-Al bonds forms 3D frameworks for the crystalline inorganic zeolite structures. COF materials, on the other hand, may be created from a spectrum of stiff organic building components with various structural arrangements.

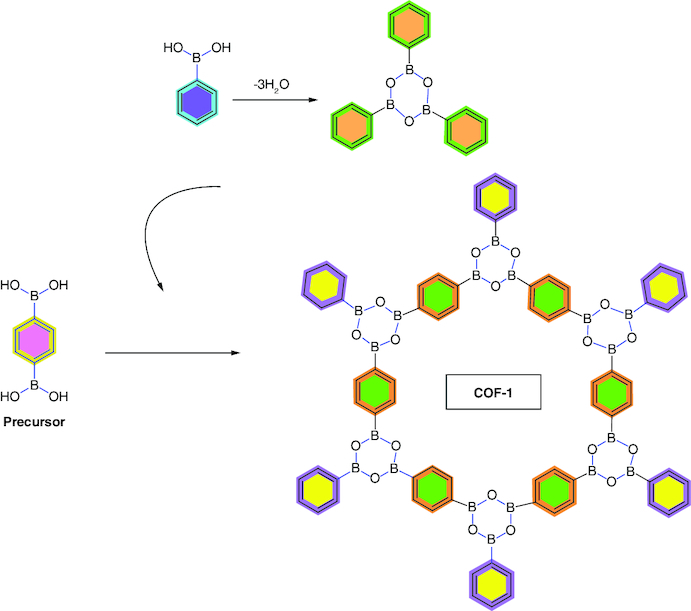

The first two members of the COF family [16], COF-1 (C3H2BO)6. (C9H12)1 and COF-5 (C9H4BO2), were viable up to 600°C and were created using a straightforward one-pot method. These two COFs were created by condensing boronic acids under minimal preparation, are efficient and high-yielding and also demonstrated modest densities and distinctive surface areas (between 700 and 1600 m2/g), better than those of well-recognized zeolites and porous silicates. Three boronic acid molecules unite to form a planar six-membered B3O3 (boroxine) ring, which is the starting point for the synthesis of COF-1 by removing three water molecules as shown in Figure 1. A five-membered BO2C2 ring is produced via the dehydration reaction between phenylboronic acid and trigonal building block, 2,3,6,7,10,11-hexahydroxytriphenylene (HHTP), which is utilized in an analogous condensation procedure for COF-5.

Figure 1.

Self-condensation of 1,4-benzenediboronic acid to produce covalent organic framework-1 with proposed crystalline structure.

Many synthetic processes, including solvothermal and ionothermal reactions and others that can be carried out at normal temperature and pressure, have been proposed for the production of COFs [22]. The generation of improved COFs depends on the strength of the covalent bonds or association among the layers. The 2D or 3D crystalline structures of COF materials are well-defined and predictable due to the generation of stiff covalent interactions through a variety of synthetic organic processes between the structural units.

In 2D COFs, the covalently connected scaffolding is limited to 2D sheets, which pile up to create a multilayered eclipsed structure with consistently positioned columns [1]. This columnar piled structure offers a special way to build structured π systems. The ordered columns in 2D COFs may facilitate charge carrier movement in the stacking direction, indicating that new π-electronic and photofunctional materials for optoelectronics and photovoltaics could be made using 2D COFs. On the other hand, 3D COFs, which broaden the framework three-dimensionally by adding a building block with a sp3 carbon or silane atom, typically have large specific surface area, many open sites and low densities. These qualities make 3D COFs the best choice for gas preservation. The production of COFs has steadily increased with various internal functionalizations, such as triazine, imine, hydrazone, borazine, azine and so on, as their presence and potential applications have been thoroughly explored.

Synthesis

With their distinctive conformations and morphologies, COFs are polymers that can interact with photons, excitons, electrons, holes, spins, ions and molecules to create limited molecular spaces and novel molecular substrates for structural and operational development [23]. These compounds comprise low densities, stiff structures and extraordinary thermal resistance (up to 600°C). Furthermore, compared with well-known zeolites and porous silicates, they have surface areas that are larger and exhibit permanent porosity. Typically, the structural components of COFs have several reactive sites and a rigid π backbone [2]. The configuration of the systems and the type of reactive units have a profound influence on the solubility of these compounds in solvent. The reaction media for the bidirectional covalent bond formation reaction is often a combination of polar and nonpolar solvents in the synthesis of COFs. Major elements to take into account for the thermodynamic regulation of the reaction are the nature of solvents, catalysts, reaction temperature and reaction time. The resulting COFs' crystallinity and porosity are determined by these variables.

Several new varieties of COFs have been created via boroxine [16], boronate-ester [24], borosilicate [25], triazine [26], imine [27], hydrazone [28], borazine [29], squaraine [30], azine [31], phenazine [32], imide [33], double stage [34], spiro-borate [35], C=C [36], amide [37], viologen [38], hypercoordinate silicon [39], 1,4-dioxin links [40] and urea [41] linkages depending on the nature of the chemical processes and applications.

Solvothermal synthesis

Most COFs are produced via solvothermal techniques, and the reaction circumstances are greatly influenced by solubility, responsiveness of the structural units, reversibility of the reactions, temperature, solvent properties and catalyst concentrations [2]. The solvothermal synthesis of COF materials typically requires heating (80–120°C) inside a sealed vessel and involves 2 to 9 days, due to the processes for synthesis in autoclaves. Notably, some COFs can be manufactured using this technique on a large scale. For instance, 2,4,6-tris(4-aminophenoxy)-1,3,5-triazine and 2,4,6-tris(4-formylphenoxy)-1,3,5-triazine are the sources for TPT-COF-1 preparation using the solvothermal method [42].

Microwave synthesis

The microwave approach has been applied for the quick synthesis of crystalline porous COFs because solvothermal synthesis requires considerable reaction time [2]. The microwave solvent extraction method has the advantage of more effectively removing oligomers from COFs, and the final formed COFs have significant porosity. The microwave approach has been used to successfully synthesize imine-linked TpPa-COF [43], COF-5 [44] and COF-102 [45], which are boronate-ester linked.

Ionothermal synthesis

CTFs are typically made using ionothermal techniques [1]. Crystalline-conjugated CTFs with strong chemical and thermal stabilities are produced via cyclotrimerization of aromatic nitrile building units in the presence of molten zinc chloride at 400°C. ZnCl2 is used in this relatively reversible trimerization reaction as a catalyst and solvent. The majority of CTFs, including CTF-1 and CTF-2, are created under ionothermal conditions [26].

Mechanochemical synthesis

A straightforward synthetic approach is desirable because solvothermal and microwave processes both take place under complex conditions (e.g., a reaction process in a sealed Pyrex tube, neutral atmosphere, sufficient solvents, temperature for crystallization) [2]. The COFs, comprising TpPa-1, TpPa-2, TpPa-NO2, TpPa-F4, TpBD, TpBD-(NO2)2, TpBD-Me2 and TpBD-(OMe)2, are produced through the mechanochemical synthesis by mixing the monomers (1,3,5-triformylphloroglucinol [Tp] with p-phenylenediamine [Pa] and benzidine [BD]) in a mortar and pestle at room temperature.

Interfacial synthesis

The interfacial synthetic process is a new and effective technique for producing COF thin films with simultaneous control of their thickness, in contrast to the aforementioned synthetic techniques, which mostly produce insoluble and processable powders [2]. For example, Tp-Bpy, Tp-Azo, Tp-Ttba and Tp-Tta have been created at the junction of two solvents by combining an aqueous solution of diamine and p-toluenesulfonic acid with dichloromethane, which dissolves Tp [46]. This technique makes it possible to create films with adjustable thicknesses between 4 and 150 nm.

Characterization

High stability, structural diversity and organized structures are the defining characteristics of COFs. They are spherical particles and have very good thermal stability. Characterization can be carried out using solid-state 13C nuclear magnetic resonance, Fourier transform infrared, powder x-ray diffraction (PXRD) [1], thermogravimetric analysis, scanning electron microscopy (SEM), transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and nitrogen sorption isotherms. When COFs were subjected to PXRD examination, their crystallinity was validated and diffraction peaks that might have been caused by the initial components or their known solvates were disclosed [16]. In addition to the PXRD [47] method used for analyzing the morphology of COFs, 3D rotation electron diffraction or 3D electron diffraction tomography data collection techniques using TEM or high-resolution TEM have also been developed for single-crystal structural analysis of micrometer- or submicrometer-sized COF crystals [48].

One morphologically distinct crystallite was detected for each COF after extensive SEM imaging, used to demonstrate the purity of the phase. The Fourier transform infrared spectra of these crystalline COFs showed bands corresponding to variant functional groups, indicating production of the anticipated ring groups in the COFs. With the help of single-crystal x-ray diffraction with a resolution of 0.85, various COFs have been produced as individual crystals, and the frameworks of these crystals have been clarified [49]. Single-crystal x-ray diffraction measurements have shown fine resolution of the exact crystal properties, such as the unit-cell parameters of the particular space group, atomic locations and geometric parameters (bond lengths and angles). This provides an opportunity to assess both structure-related features and absorption of guest molecules, opening the door to thorough mechanistic investigations of COFs.

Other instruments for characterizing and verifying results include solid-state 13C nuclear magnetic resonance, elemental analysis, field-emission SEM, atomic force microscopy, thermogravimetric analysis, optical transient absorption spectroscopy, BET surface area and pore size evaluation by gas sorption isotherm measurements [2]. Along with static detection techniques, dynamic light scattering measurements provide information about the quantity and typical size of COF particles within the polymerization system [50]. The turbidity of the reaction system is also helpful in estimating the rate of COF formation and its responsiveness to the polymerization conditions of initially homogeneous systems.

Types of COFs

COFs with design principles

Two-dimensional COFs

In 2D COFs, 2D sheets can be covalently linked to the framework. These sheets are further stacked to create a layered eclipsed structure with periodically aligned columns. In addition to producing completely arranged π arrays, 2D COFs also produce 1D open channels [23]. For example, to produce 2D COFs like COF-6, boronic acid building blocks like benzenetriboronic acid must be combined with HHTP. A novel type of π-electronic and photofunctional material for photovoltaics and optoelectronics may be created using 2D COFs because of the ordered columns in these structures, which may allow charge carrier transit in the stacking direction. Other examples of 2D COFs are COF-8 and COF-10.

Three-dimensional COFs

High specific surface areas, many open sites and low densities are the hallmarks of 3D COFs, which expand the covalently bonded framework in 3D using a structural unit containing a sp3 carbon or silane atom [1]. Due to these features, 3D COFs are excellent options for gas preservation. Tetrahedral tetra-boronic acids have been used as precursors, and HHTP was used to condense or cocondensate 3D frameworks [51]. Examples of 3D COFs include COF-102, COF-103, COF-105 and COF-108 [52].

COFs with linkage diversities

Novel varieties of COFs have been created using different functional linkages. The porous COF structures thus formed have extremely low densities, good stability and permanent porosity with unusual functionalities like gas adsorption and storage, sensing, water treatment and electronic conductivity, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Applications of covalent organic framework composites.

| S. no. | Type of linkage | COF | Building blocks/organic linkers | Pore size (Å) | Applications | Examples | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Boroxine | COF-105 | 1,4-Benzenediboronic acid; 2,3,6,7,10,11-hexahydroxytriphenylene | 27 | Gas separation, neutral, acidic, basic analyte separation | COF-1, COF-102, COF-103, TP-COF, COF-18 Å | [3,16] |

| 2 | Triazine | CTF-1 | 1,4-Dicyanobenzene; 1,3,5-tricyanobenzene | 12 | Gas separation | CTF-2, CTF-0 | [3,26,53] |

| 3 | Imine | COF-300 | Tetra-(4-anilyl) methane; terephthaldehyde | 7.2 | Water treatment, fuel cells, gas separation, racemic alcohol separation | COF-366, COF-42, COF-LZU1 | [3,27,28] |

| 4 | Azine | ACOF-1 | 1,3,5-Triformylbenzene hydrazine hydrate | 9.4 | Gas separation | [3,31] | |

| 5 | Polyimide | PI-COF-1 | Pyromellitic dianhydride; tris(4-aminophenyl) amine | 33 | Electronics and semiconductors | PI-COF-2, PI-COF-3 | [3,33] |

| 6 | Polyarylether | JUC-505 | Tetrafluoroterephthalonitrile; 1,2-dihydroxybenzene | 16.8 | Gas adsorption and separation | JUC-506, JUC-505-NH2 | [3,54] |

| 7 | β-Ketoenamine | TpPa-1 | 1,3,5-Triformylphloroglucinol | 18 | Water treatment, fuel cells, pervaporation, gas separation | TpPa-1, TpBD, TpHz, TpAzo | [3,55] |

| 8 | Thiophene | T-COF 1 | 2,3,6,7,10,11-Hexahydroxytriphenylene; 2,5-thiophenediboronic acid | 13.8 | Electron conductivity and gas separation | T-COF 2, T-COF 4 | [3,56] |

| 9 | Benzodithiophene | BDT-COF | Benzodithiophene-2,6-diyldiboronic acid; polyol 2,3,6,7,10,11-hexahydroxytriphenylene | 34 | Photoluminescence activity | BDT-COF thin films, TT-COF | [3,57] |

ACOF: Azine-linked COF; BDT COF: Benzodithiophene COF; COF: Covalent organic framework; CTF: Covalent triazine framework; PI COF: Polyimide-linked COF; S. no.: Serial number; T COF: Thiophene-based COF.

Boroxine-linked COFs

Boron-containing COFs are constructed through the self-condensation of single building units. As an illustration, 1,4-benzenediboronic acid undergoes a self-condensation reaction to produce COF-1 [16]. These boron-containing COFs have the benefits of modest densities, better BET surface areas and excellent thermal stabilities (up to 450–600°C).

Triazine-linked COFs

The synthesis process for triazine-linked COFs is based on the cyclotrimerization of nitrile building blocks in the existence of zinc chloride [3]. These triazine-based COFs (CTFs) usually show minimal crystallinity compared with boron-containing COFs but possess strong thermal and chemical stability. CTFs may be useful as catalyst reinforcers due to their concentration of nitrogen atoms [53]. These are most effectively generated using ionothermal synthesis [26].

Imine-linked COFs

The covalent creation of separate -C=N- bonds allows the separation of imine-based COFs that have thus far been synthesized using two groups [27]; the first is a Schiff base type. For example, COF-300 belongs to this category and is produced when aldehydes and amines cocondensate. Through the cocondensation reaction of aldehydes and hydrazides, hydrazone-linked imine-based COFs are formed and constitute the second type of imine-based COFs (e.g., COF-42 and COF-43) [28]. They are primarily employed in catalytic and optoelectronic applications.

Azine-linked COFs

Efficiently crystalline 2D azine COFs are produced when hydrazine and pyrene are combined during solvothermal condensation [31]. The pyrene stacking orientation makes azine-linked frameworks profoundly luminous, whereas the hydrazine units operate as open docking sites for hydrogen-bonding interactions. For example, the explosive 2,4,6-trinitrophenol can be selectively detected using azine-linked pyrene frameworks with better sensitivity and selectivity provided by the synergistic applications of the vertices and edge units (e.g., py-azine COFs).

Imide-linked COFs

An imide linkage is created by reacting amine derivatives with acetic anhydride [3]; this process necessitates a high reaction temperature of up to 250°C. Examples include polyimide (PI)-COF-1, PI-COF-2 and PI-COF-3, produced using solvothermal methods [33]. These have exceptional thermal and chemical stability.

Spiroborate-linked COFs

The condensation of polyols with alkali tetraborate or boric acid, or the thermodynamic transesterification of borate and polyols, are two simple processes that can result in the formation of spiroborate bonds [35]. The ionic boronic acid derivatives known as spiroborates have high hydrolysis resistance and are stable in methanol, water and normal environments [2]. These COFs absorb a significant quantity of H2 and CH4 and have large BET surface areas.

Polyarylether-based COFs

To create ether linkages, ortho-difluoro benzene and catechol building blocks engage in nucleophilic aromatic substitution reactions. This process produces polyarylether (PAE)-COFs [54]. The materials produced have been confirmed as stable in hostile chemical environments such as boiling water, potent acids and bases and redox conditions. Antibiotics present in water bodies (pH: 1–13) were successfully removed by PAE-COFs having carboxyl- or amino-functionalized moieties. These stable COFs are the ideal starting point for creating functional materials that may be utilized in harsh chemical conditions. A few examples are JUC-505, JUC-506 and JUC-505-NH2.

Lithium-doped 3D COFs

Doping electropositive metals into COFs is a potential way to increase hydrogen storage capacity. When Mulfort and Hupp worked on applied chemical condensation techniques to create the lithium (Li)-doped COF, they discovered the hydrogen adsorption capacity of the generated Li-doped COF had increased by almost double [58]. The Li cations doped into COFs with a positive charge are responsible for efficient binding of hydrogen and improved adsorption. Only positively charged Li atoms increase hydrogen capacity whereas neutral Li atoms and anions do not.

β-Ketoenamine-linked COFs

To prepare β-ketoenamine-linked COFs, redox-active 2,6-diaminoanthraquinone (DAAQ) moieties are added to a 2D COF connected by β-ketoenamines, providing exceptional hydrolytic stability [59]. Its 2D layered architecture and higher capacitance explain why this material exhibits well-defined, quick redox processes [55].

Thiophene-based COFs

The synthesis and characterization of a remarkable charge transfer complex between thieno[3,2-b] thiophene-2,5-diboronic acid and tetracyanoquinodimethane are key steps in the production of thiophene-based COFs [56]. This complex was made possible by the distinctive COF architecture. Taken together, these findings highlight significant synthetic advancements made in COF implementation in electronic devices (e.g., T-COF 1 and T-COF 2).

Benzodithiophene-based COFs

HHTP and a diboronic acid containing benzodithiophene were condensed to produce BDT-COFs. These BDT-COFs may be handled in air with good gas storage efficiency since benzodithiophene is an abundantly porous, crystalline and thermally stable component [57].

COFs on substrates

COFs on porous ceramic α-Al2O3 substrate

COFs have been prepared on the exterior of porous metal oxides [3]. One such example is the development of 3D COF-320 on porous ceramic -Al2O3 [60]. As a connector between the COF and porous -Al2O3, 3-aminopropyltriethoxysilane is used in this technique to functionalize the surface of porous -Al2O3. The 3D COF-320 membrane, which is permselective to hydrogen-methane and hydrogen-nitrogen, has a high hydrogen permeance and is hydrogen selective.

COFs on 3D graphene substrate

Interfacial polymerization methods were applied to generate graphene substrate-based COFs (e.g., COF-DAAQ BTA-3DG) [3]. A DMAc solution of benzene-1,3,5-tricarbaldehyde and DAAQ is mixed and soaked in 3D-graphene in the procedure for this COF [61]. Large specific capacity helpful for photoconduction is found in this synthetic COF-graphene composite.

COFs on capillary substrates

Polydopamine has been used to create polydopamine-coated capillaries by modifying the capillary substrate [62]. To produce a COF on the polydopamine capillary, the capillary is sealed and heated to 100°C for 20 h. It is then rinsed with methanol and dried under nitrogen flow. The COF-5 polydopamine capillary is the best illustration of this procedure. Glass substrates [63], amine-modified reduced graphene oxide [64], hexagonal boron nitride [65], 3-aminopropyltrimethoxysilane-functionalized silicon wafer [66], single-layer graphene [67,68], highly oriented pyrolytic graphite [69], metal substrates prepared from silver and gold, copper foil (single-layer graphene–copper) [70] and amino-functionalized carbohydrates [71] are some additional examples of substrates used for COFs.

Integrated COFs: MOF composites

More than 80,000 MOFs with more than 2000 topologies and 500 COFs with more than 18 topologies have so far been reported [72]. Strong covalent bonds hold conventional COFs together and open metal sites are typically absent. The durability of the coordination bond in MOFs is usually weaker than that of COFs, which restricts their applicability in certain conditions. Conversely, open metal sites play a significant role in MOFs and are appropriate for a variety of catalytic processes. The insertion of the secondary building units of MOFs into the building units of COFs will result in targeted products with traits from both MOFs and COFs. Those formed components will retain their unique characteristics (large specific surface area, configurable pore sizes, periodic network structures and beneficial chemical and thermal stability) but will also work in concert to provide multifunctional properties for particular uses such as energy conservation, photodynamic energy conversion, heterogeneous catalysis, adsorption and separation and detecting and semiconducting capabilities (Table 2).

Table 2.

Metal-organic framework/covalent organic framework composites and their applications.

| S. no. | MOF/COF composites | MOF used | COF used | Interaction | Applications | Examples | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | MCOF | Zn, Cu | 2D COFs, 3D COFs | Metal-ligand coordination | Catalysis and gas separation | Zn-COFs, Cu-COFs | [73] |

| 2 | MOF@COF | NH2-MIL-68 | TPA-COF | C=N | Photodegradation of rhodamine B | NH2-MIL-68@ TPA-COF | [74] |

| NH2-MIL-101 | NTU-COF | B-O, C=N | Styrene oxidation | NH2-MIL-101@ NTU-COF | [75] | ||

| 3 | COF@MOF | NH2-UiO-66 | TpPa-1 | C=N | Photocatalytic H2 evolution | TpPa-1 C=N@ NH2-UiO-66 | [76] |

| 4 | MOF + COF | NH2-MIL-125 | TTB-TTA | C=N | Photocatalytic degradation of methyl orange | NH2-MIL-125(Ti)+TTB-TTA | [77] |

| 5 | C-MOF | Ti6O6 | NH2 | Imine condensation | Photocatalyzed polymerization of methyl methacrylate | MOF-901, MOF-902 | [78] |

COF: Covalent organic framework; MOF: Metal-organic framework; Pa: P-phenylenediamine; S. no.: Serial number: Tp: Triformylphloroglucinol; TPA-COF: Triphenylamine-based COFs; TTA: Triazine-triyl-trianiline; TTB: Triazine-triyl-tribenzaldehyde.

Metal COFs

By connecting MOFs and COFs with MCOFs, complementary qualities between the two types of materials can be leveraged [72]. These properties are a balanced mixture of crystallinity, porosity, stability and tunability. Two-dimensional MCOF construction involves the use of planar building elements to form layered and stacked structures. Three-dimensional MCOFs [73] have the potential to provide several open metal sites with different orientations, setting them apart from 2D MCOFs [73]. These MCOFs have intriguing applications in a range of domains, primarily gas differentiation and catalysis. Zinc-COFs and copper-COFs are two types of MCOFs.

MOF@COF

Using MOFs as the connecting cores and COFs as the shells, MOF@COF composites were created [72]. Covalent bonding is used to create these core-shell MOF@COF composites. The aromatic characteristics of MOFs and the ordered columnar structural characteristics of COFs encourage strong stacking connections between MOFs and COFs, resulting in the development of core-shell MOF@COF composites. Examples include the composites NH2-MIL-68@TPA-COF [74,79] and NH2-MIL-101(Fe)@NTU-COF [75,80].

COF@MOF

In the process of producing COF@MOF composites, several synthetic methods have been devised that are similar to those used to create MOF@COF composites [72]. In the preparation method, the core-shell COF@MOF combination is created by introducing an amino-functionalized MOF to the synthetic reaction system of a COF (e.g., composite COF@MOF: TpPa-1-COF@NH2-UiO-66) [76,81].

MOF + COF

Apart from MOF@COF or COF@MOF composites that incorporate both MOFs and COFs, different combinations of MOF + COF have also been created that do not contain core-shell structures [71]. To produce MOF + COF composites, the COFs and MOFs are first postsynthetically covalently altered, and then the COFs or MOFs are subsequently added to the outer surface. The best example of this is the composite made of NH2-MIL-125(Ti) [82] and TTB-TTA [77].

C-MOF

The composition of C-MOFs is closer to that of MOFs, whereas the synthesis conditions are closer to those of COFs [72]. By fusing the chemistry of MOFs and COFs, the first C-MOF, designated MOF-901, was created [83]. An amine-functionalized titanium-oxo cluster was produced in situ and connected to terephthalaldehyde using an imine condensation reaction as part of the growth process of MOF-901 [78].

COF-in-MOF

Apart from cultivating COFs on MOF surfaces, one may also meticulously cultivate COFs inside specific MOFs utilizing the latter structures as templates [72]. For this scenario, the COFs created using MOF templates may inherit the mother MOFs' regular morphology and exquisite crystallinity [84].

3D CCOFs

Racemic alcohols sulfoxides, carboxylic acids and esters are separated by HPLC using 3D CCOFs as CSPs [85]. By coning a tetrahedral tetra(4-anilyl) methane with a tetra-aldehyde, a 3D CCOF is created (e.g., CCOF-5 and CCOF-6). For the separation of racemic alcohols, the degree of separation and selectivity factors recorded for CCOF-5 and CCOF-6 are comparable to or higher than those previously generated for MOF-based CSPs.

CCOF-bound capillary columns

During the preparation procedure, chiral (+)-diacetyl-L-tartaric anhydride ((+)-Ac-L-Ta) will first functionalize Tp to create a chiral functionalized monomer CTp [86]. To create the final CCOF, -CTpBD, BD is then condensed with CTp. High thermal stability is demonstrated by these CCOFs. Additionally, manufactured CCOF-bound capillary columns exhibit a profound degree of separation for enantiomers. CTpPa-1 and CTpPa-2 are further illustrations.

CCOF CTpBD@Sio2

Using an in situ growth technique, the CCOF CTpBD was immobilized on the surface of amino-functionalized silica (SiO2-NH2) to generate the CCOF core-shell microsphere composite CTpBD@SiO2 [87]. This CSP was employed as a new CSP for HPLC enantiomers separation. Compared with other CCOFs, the manufactured CTpBD@SiO2-packed column shown high column efficiency, high enantioselectivity and good repeatability toward diverse racemates.

Magnetic COFs

Fe3O4 was used as the core and terephthaldicarboxaldehyde and 1,3,5-tris(4-aminophenyl) benzene were applied as the organic ligands to create the core-shell structured Fe3O4@COFs [88]. In the majority of cases, these magnetic COFs are used to remove organic pollutants, harmful metal ions, colors, medications and personal care products.

Applications of COFs

General use applications

Covalent organic/inorganic hybrid proton exchange polymeric membranes

Cross-linked sulfonated polyether ketone aromatic polymers have been utilized to create covalent organic/inorganic hybrid proton exchange polymeric membranes [10]. The exceptional temperature stability, mechanical toughness and oxidative stability of these aromatic polyether ketones and polysulfones are well recognized. Ion-conductive membranes for fuel cells comprise one promising use of these aromatic polymers. The ionomer membrane in fuel cells serves as an electrolyte for proton transport and a barrier between the two electrodes. By inserting acidic units among these aromatic rings of polymers, typically with a sulfonation reaction, proton conductivity can be created.

COFs as porous nanotubes & fullerenes

Two-dimensional COFs are extended sheets of organic units covalently bonded to generate porous materials that exclusively contain light components. These sheets can be folded into stable nanotubes and, depending on the energetics, a COF made of fullerene is possible [89]. These substances have intriguing uses in gas storage, as molecular transporters, filters or structural units for 3D structures.

High carbon dioxide preservation capacity in COFs

CO2 shows a strong quadrupole moment but, unlike other gases, lacks a dipole moment [2]. To maximize absorption capacity and selectivity, it is essential to build a porous structure that makes use of this fundamental property. COFs provide a novel pathway for constructing apertured structures to preserve and segregate CO2 with high capacity due to the combined characteristics of profound structural arrangement and chemical stability. It was determined that 3D COFs have significantly more empty volume, porosity and surface area for CO2 storage than 2D and 1D COFs, confirmed by data from atomistic simulations on CO2 storage in COFs including 3D (COF-102, COF-103, COF-105 and COF-108), 2D (COF-6, COF-8 and COF10) and 1D (COF_NT) structures [90].

COFs for hydrogen storage

Efficient covalent connections (C-C, C-O, B-O and Si-C) between each organic building block in COFs enable the production of components with more porosity and minimal crystal density. Compared with MOFs that contain metal ions, these features make COFs ideal candidates for storing H2 [91]. Because of their large surface area and free volume, these 3D COFs (COF-102, -103, -105 and -108) possess more hydrogen storage capacity (i.e., 2.5–3-times) than that of 2D (COF-1 and –5) and 1D COFs.

COFs for ammonia storage

The gathering and preservation of dangerous gases is another application of COFs [9]. For example, ammonia is a frequently used chemical that must be used properly because of its harmfulness and corrosiveness. Since ammonia is a Lewis base, it can efficiently interact with Lewis acidic groups, like boron atoms found in boroxine or boronate ester-based COFs [92]. Moreover, these boronate ester-based COFs have a high density of Lewis acid boron sites, which are an essential part of their frameworks for usage. COF-10, which is generated via condensation of HHTP and biphenyl-tetracarboxylic acid dianhydride building units, displays great capacity for ammonia storage. The boron sites in these COFs are ideal for storing corrosive materials like ammonia due to their unique adsorbent surface that is ready to interact with Lewis base gases.

COFs in heterogenous catalysis

In addition to adsorbing gas molecules, COFs can also load other compounds into their nanopores [1]. Imine-based COF-LZU129, for example, can incorporate Pd ions into its pores to form Pd/COF-LZU1 using collaboration between the nitrogen atoms in the COFs and the Pd ions [93]. A heterogeneous catalytic system is formed by the Pd ions on the COF walls, which are remarkably catalytically active and accessible to both the substrate and the reactant.

COFs as semiconductors

Electronic and optoelectronic materials are constructed using COFs. For instance, the π-electronic 2D terephthalaldehyde-COF, which is composed of interlocking hexagons with pyrene-2,7-diboronic acid groups at the edges and hexahydroxytriphenylene molecules at the vertices, produces a strong blue luminescence [24]. Consequently, terephthalaldehyde-COFs will collect a variety of photons ranging from UV to visible and transform those to stunning blue illumination.

COFs in photoconduction

Superior-grade single crystals of particular π-conjugated arenes can display photoconductivity due to exciton migration throughout the lattice and charge separation at the molecule–electrode interface [1]. The columns' periodic alignment and the stacking structure's eclipse make it manageable for COFs to initiate photoconductivity. A pyrene-based polypyrene-COF has been prepared through the self-condensation of pyrene-2,7-diboronic acid and is the first illustration of a photoconductive COF. With dimensions in the micrometer range for their length, width and thickness, polypyrene-COFs have a cubic shape. The production of excimer in the stacked pyrenes gives rise to the intensely blue luminescence of these cubes [94].

COFs as sensors

COFs have small-volume pores and a defined pore environment, making them appealing materials for sensing applications [19]. An azine-linked COF (made from hydrazine and 1,3,6,8-tetrakis(4-formylphenyl) pyrene with four aldehyde groups) was subjected to a nitroaromatic compound-induced fluorescence quenching test. This azine-linked COF was very sensitive and selective in this experiment when exposed to the explosive 2,4,6-trinitrophenol [31]. The same concept was investigated using the imine-connected 3D-polypyrene-COF. Fluorescence quenching was demonstrated by a 75% decrease in fluorescence at a 20 ppm concentration of picric acid [95].

H2 evolution with COF photocatalysts

COFs are a significant discovery i9n relation to heterogeneous photocatalysis because they are composed of molecular building blocks, allowing them to have nearly infinite chemical tunability for all tasks necessary to the photocatalytic process, namely light processing, differentiation of charges, charge conveyance and electrocatalysis. Substantial surface areas and a significant interaction surface provide greater exposure to inducers, electrolytes, suicidal components and complementary catalysts across the sample, owing to the extreme architectural permeability. A 1,3,5-tris-(4-formyl-phenyl) triazine-COF is a potent H2-evolving photocatalytic system [96].

COFs for environmental applications

Emerging environmental contamination poses a serious threat to the ecosystem and human health. Adsorption, enhanced oxidation and membrane separation are just a few of the many methods that have been created to remove environmental toxins. The environmental remediation uses of stable COFs are numerous and emerging. They were able to catalyze the conversion of clean energy into a usable form and also initiate the degradation of pollutants by adsorbing metal ions, (volatile) hazardous organic pollutants and gases such as CO2 and volatile iodine through their pore channels, as shown in Table 3. This improved the performance of membrane-based separation.

Table 3.

Performance of covalent organic frameworks in adsorbing hazardous environmental contaminants.

| S. no. | Adsorbents | Adsorbates | Adsorption selectivity | Adsorption mechanism | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | COF-LZU8 | Hg2+ | Hg2+, Co2+, Cu2+, Pd2+, Cd2+, Mg2+ | Interactions between Hg (II) and Pd atoms | [97] |

| 2 | COF-TpAb-AO | UO22+ | UO22+ | Coordination of AO and UO22+ | [98] |

| 3 | CTF-CTTD | I2 | I2 | Dynamically changes guest-accessible pores | [99] |

| 4 | iCON | TcO4- | ReO4-A vs NO3, CO3-2, PO4-3 | Anion exchange between ReO4-A and Cl- | [100] |

| 5 | 3D COF-COOH | Nd3+ | Nd3+vs Sr2+, Fe3+ | Interaction between Nd3+ and carboxy groups | [101] |

| 6 | TS-COF-1 | Methylene blue Rhodamine B Congo red |

NA | Intrinsic pore-size effect of adsorbents and size of adsorbates | [102] |

3D COF-COOH: Functionalized 3D COFs; AO: Amidoximated COFs; COF: Covalent organic framework; CTF: Covalent triazine-based framework; iCON: Ionic COFs; LZU: Lan Zhou University; MOF: Metal-organic framework; NA: Not available; S. no.: Serial number; TS COF: Triazine-based COFs.

COFs as adsorbents

In addition to collecting gas molecules, multifunctional COFs can be employed as adsorbents to extract metallic ions and hazardous organic pollutants from aqueous solutions [103].

Heavy metals & radionuclides

Several COFs have exhibited rapid adsorption equilibrium, elevated adsorption capacity and robust adsorption selectivity toward various heavy metal ions and radioactive compounds, such as Hg2+ [97], UO22+ [98,104], I- [99], Nd3+ [101] and TCO4 [100].

Poisonous organic pollutants

Due to their poisonous nature, organic pollutants such as organic dyes and pharmaceutical pollutants have also caused considerable concern in addition to inorganic contaminants [103]. Because of their hydrophobic character, COFs have a strong attraction for a variety of lipophilic organic materials. Organic dyes, such as methylene blue, rhodamine B and Congo red, could be successfully adsorbed by PI COFs functionalized with triazine [102].

Gas adsorption

COFs with high porosity, like COF-103 [105], and low density, like COF-108 [105], have been appraised for gas adsorption. These COFs demonstrate great promise for the adsorptive elimination of unstable pollutants, like volatile iodine [106], and for the preservation of incineration gas products, like CO2 [90].

Filtration membranes

COFs are options for making membrane materials for separation because of their organized, adjustable, nanodimensional (1–2 nm) pore channels. To elaborate membrane assembly for water treatment, a COF-based composite membrane was created by directly crystallizing COFs on polysulfone substrates [107]. This COF-polysulfone membrane demonstrated durable stability in very acidic and basic conditions, as well as high water permeance and stable rejection rates to various dye molecules. For the separation of CO2/CH2, a mixed matrix membrane made up of azine-linked COFs (ACOF-1) was created [108].

Chemical sensors

In the identification of many contaminants, such as cations (e.g., Hg2+, Cu2+ and ammonia [109]), anions (e.g., F- [110]) and organics (e.g., 2,4,6-trinitrophenol [111], enrofloxacin and ampicillin [112]), COFs with luminescence properties are promising chemical sensors. Azine-linked COFs and 3D pyrene-COFs are two examples.

Catalysts

COF-based catalysts are typically used in photo- or electrocatalytic reactions to preserve clean energy (e.g., CO2 reduction and H2 production) and for toxin degradation in the field of environmental protection. Another interesting environmental use of COFs is the creation of H2 and CO2 reduction through the use of COF-based catalysts. Examples of this include the loading of COFs into manufactured cobaloximes and the electrocatalytic abilities of various metals to load CTFs [113]. Research on COF-based catalysts for pollutant degradation is crucial. TpMA COFs [114] and COF-based catalysts (Pd/COF-LZU1 [115]) were used in the photocatalytic deprivation of phenol and methyl orange coloring.

Pharmaceutical applications

COFs and their combinations have been studied as potentially useful absorbents for SPE, prospective coverings for SPME and unique stationary phases for GC, HPLC and CEC because of their unique properties, which include simplicity in transformation, minimal density, huge unique surface areas, excellent stability and persistent porosity, as shown in Figure 2 [12].

Figure 2.

Pharmaceutical applications of covalent organic frameworks.

COFs applicability in analytical separation science

-

1.

The BET surface area and aperture size range of COFs employed in analytical separation science are 114 to 1590 m2/g and 7 to 34, respectively.

-

2.

Because of their excellent crystallinity and great stability, imine-linked COFs have become prominent in the field of separation science.

-

3.

COFs can be utilized as sorbents for SPE, including CTF-1, CTpBD, TpPa-2 and COF-1.

-

4.

Magnetic SPE has been done using magnetic COFs@Fe3O4 composites such as TpBD@ Fe3O4, TbBd@ Fe3O4 and TpPa-1@ Fe3O4.

-

5.

COFs@SiO2 composites, including hydrazone COF@SiO2 and TpBD@SiO2, are examples of stationary phases for HPLC.

COFs for sample pretreatment

COFs for SPE

Numerous unique, nonhydrophobic mechanisms, such as hydrogen bonding, electrostatic attraction and the π–π electron donor–acceptor associations, were credited with the extraordinary extraction efficiency of COFs. Magnetic SPE, due to its superior mass transfer effectiveness, practicality and ecological compatibility, is an essential sample preparation method. Building magnetic COF composites in SPE has attracted interest since it combines the advantages of COFs' efficient extraction capabilities with magnetic separation's advantages [12].

Eight monocyclic aromatic compounds were separated from an aqueous solution using CTF-1, a superb adsorbent with fast sorption/desorption dynamics and complete sorption reversibility [116]. Compared with one of the most widely used and well-liked polymeric adsorbents, Amberlite XAD-4 resin, this CTF showed much higher adsorption of polar and/or ionic compounds.

A polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS)/CTF stir bar coating was developed to sorptively extract eight phenols from natural water specimens, including phenol, 2-chlorophenol, 2-nitrophenol, 4-nitrophenol, 2,4-dimethylphenol, p-chloro-m-cresol and 2,4-dichlorophenol [117]. HPLC-UV detection was further employed. The generated PDMS/CTF coating's hydrophobic effect, π–π conjugate and intermolecular hydrogen link led to an extremely high yield of extraction for the specified phenols.

COF-CTpBD was successfully used as an enrichment material for online SPE followed by ICP-MS to determine different trace ions [118]. For the pretreatment of trace/ultratrace metal ions in complicated materials, the CTpBD demonstrated excellent potential as an effective adsorbent. Then, it was necessary to separate and enrich Cr (III), Mn (II), Co (II), Ni (II), Cd (II), V (V), Cu (II), As (III), Se (IV) and Mo (VI) and the contents by ICP-MS.

COF TpPa-1 was used to extract N-linked glycopeptide enriched tryptic digests of two reference glycoproteins (human IgG and HRP) before matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-TOF mass spectrometry studies [119]. TpPa-1 demonstrated outstanding recycling and clinging ability, and this approach has been shown to have great biocompatibility, specificity and precision.

TpPa2-Ti4+, a COF-based immobilized metal ion affinity chromatography material, was made by simply immobilizing Ti (IV) into TpPa-2 COFs without the use of additional complexing ligands [120]. The produced COFs with titanium (IV) ion modifications displayed discernment (β-casein: BSA = 1:100) for phosphopeptide capture from β-casein. With great sensitivity and acceptable selectivity, they were also effectively used to enrich phosphopeptides from nonfat milk and HeLa cells.

Superparamagnetic Fe3O4 nanospheres were used as core centers in the preparation of magnetic core-shell COF nanospheres, and TpBD was used as the core-shell since it is a highly stable porous COF [121]. Bisphenol A and bisphenol AF, two common endocrine-disrupting chemicals, can be rapidly eliminated from aqueous solutions using these magnetic core-shell COF nanospheres, which have an efficient sorption capability and reusability.

For isolating phthalate esters from plastic materials, a magnetic CTFs/Ni composite was generated through the in situ incorporation of nickel ions onto the CTF matrix using a solvothermal technique [122]. The generated CTFs/Ni composite had great extraction efficiency for the targeted phthalate esters due to π–π interaction and hydrophobic effects, and was characterized by good preparation repeatability and chemical stability. Additionally, the quick transfer of target phthalate esters from the aqueous solution to the adsorbents was made possible by this CTF/Ni composite's magnetic properties, which reduced matrix interference for the extraction.

Core–shell Fe3O4COFs proved a successful novel sorbent for peptide enrichment [123]. The prepared Fe3O4@COFs displayed intrinsic properties of simple preparation, undeviating aperture dimensions, maximum magnetic responsiveness, wide exterior surface area and superior chemical stability, leading to a straightforward, quick and effective peptide-enrichment process. Additionally, the Fe3O4@COFs composites showed beneficiary size-exclusion performance for the selective capture of peptides and deterrence of proteins, extending the scope of COFs' applicability in proteomic research.

By attaching a COF (TpPa-1) to surface-modified Fe3O4 nanoparticles, a bouquet-shaped magnetic porous nanocomposite was created [124]. This magnetic TpPa-1 (prepared using Tp and Pa components) comprises interconnected porous TpPa-1 nanofibers and clusters of core-shell magnetic nanoparticles. As a result, they showed greater specific surface area, greater porosity and a stronger magnetic field, making them the perfect sorbent for enriching trace analytes. The magnetic SPE of trace polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) from environmental materials was used to assess the performance of these magnetic COFs.

COFs for SPME

Using less solvent, SPME integrates sample introduction, extraction and sampling into a single step, making it a most promising sample pretreatment techniques [12]. The application of COFs in SPME has drawn recent attention. The enormous adsorption capacity and long lifespan of the synthesized SPME fibers are guaranteed by strong covalent bonds and multilayered COFs. First, 1,3,5-benzenetricarboxaldehyde and terephthalic dihydrazide were combined to create a hydrazone COF. The second step was to create polydopamine (PDA) modified stainless-steel fiber (SSF) by dipping the prepared SSF into a dopamine solution with a pH value of 8.5 that had been adjusted with tris-HCl solution. Finally, utilizing 3-aminopropyltriethoxysilane as the linker, the hydrazone COF was incorporated into the PDA-SSF. These prepared COF fibers are particularly selective for pyrethroids due to the abundance of phenyl rings and C=N groups on hydrazone COFs that offer opportunities for hydrophobic and hydrogen bonding contact, π–π stacking and van der Waals forces [125]. The created COF fibers can be used to isolate pyrethroids from samples of fruits and vegetables.

Through the use of thiol-ene click chemistry, a cross-linked hydrazone COF coating was generated and used for the SPME of pesticides in crops. Van der Waals forces and π–π hydrogen-bonding interactions among the analytes and COFs were important in the extraction process [126].

COFs as stationary phases for chromatography

Predominance of COF-based columns over traditional silica columns

In separation science, COFs are also appealing due to their unique architectures and range of functions. Its exceptional extraction efficiency is attributed to several distinct, nonhydrophobic processes, including electrostatic attraction, hydrogen bonding and π–π electron donor–acceptor contact. Compared with Amberlite XAD-4, the most effective commercial polymeric resin, CTF-1 sorbent showed greater sorption of polar and/or ionic chemicals. With strong linear range, low detection limits, good repeatability and enrichment factors, the manufactured PDMS/CTF-coated stir bars for SPE are either equal to or better than commercial polyethylene glycol (PEG)- and PDMS-coated stir bars [116,117]. The CCOF-bound capillary columns outperformed commercial chiral capillary columns Cyclosil B and β-DEX 225 in terms of resolution and isolation factors. Their van der Waals interaction, hydrogen bonds, π–π interaction and chiral microenvironment were important in chiral GC. The best example is that, compared with conventional chiral columns, baseline separation of (±)-methyl lactate, (±)-1-phenylethanol, (±)-limonene and (±)-1-phenyl-1-propanol was obtained on the CCOF-bound capillary columns in just 5 min. Because of their distinct architectures, large surface area and strong solvent stability, COFs have prospective use in HPLC. For instance, isocratic elution without adding buffers in the mobile phase was used to achieve baseline separation of five nucleobases (Cyt, Ura, Thy, Gua and Ade), five nucleosides (C, U, T, G and A) and five deoxynucleosides (dC, dU, dT, dG and dA) on the TpBD@SiO2-pPDMS/CTFacked column. This is a beneficial improvement over commercial C18 and NH2-SiO2 columns. COFs@SiO2 composites show promise in HPLC due to the strong separation ability of COFs and the healthy column-packing properties of regular silica microspheres.

COF-based columns for GC

COFs are excellent candidates for the stationary phase in GC because of their enormous surface areas and better heat and chemical stability [12]. Chiral separation is a further use of COFs in GC. Significant contributions to chiral GC were made by the chiral microenvironment, π–π interaction, hydrogen bonding and van der Waals interaction of CCOFs.

Tp and BD were easily synthesized in solution form to create TpBD, a COF [127]. This was done by mixing the ethanolic solution of Tp and BD at ambient temperature. On the TpBD-coated column, a variety of significant industrial analytes are baseline separated with excellent column efficiency and good precision. The hydrogen connection among the analytes and the TpBD frameworks, π–π interactions and van der Waals interaction are all necessary for the isolation of these significant industrial analytes.

To create the chiral monomer CTp, an enantiomer of (+)-diacetyl-L-tartaric anhydride was used in reaction with Tp. The obtained CTp was summarized with appropriate diamine to create CCOF-CTpPa [128]. On this formed CCOF-bound capillary column, isolation of (±)-methyl lactate, (±)-1-phenylethanol, (±)-limonene and (±)-1-phenyl-1-propanol has occurred.

COFs for HPLC

COFs have potential in HPLC because of their distinctive architectures, strong solvent stability and large surface areas [12]. One intriguing and practical method for overcoming the drawbacks of bare COFs, such as their irregular form and wide size distribution for HPLC use, is the fabrication of COF core-shell microspheres. TpBD COF [129], which is made up of BD and Tp, acts as the COF shell, and aminosilica (SiO2-NH2) is the core to support the TpBD shell. By adjusting the Tp and BD monomer concentrations, the TpBD shell thickness can be changed. These formed TpBD@SiO2-packed columns exhibit excellent hydrophobic selectivity and better reproducibility for the isolation of acidic molecules (p-cresol, hydroquinone and p-chlorophenol), basic molecules (nucleosides, nucleosides and deoxynucleosides) and neutral molecules (toluene and ethylbenzene, PAHs).

Cyclic trimerization of terephthalonitrile was used to decorate the surface of a cyano-terminated silicon spheres (CN-SiO2) with CTFs [130]. These were used to analyze a wide range of probe molecules, such as monosubstituted benzenes, PAHs, phenols, anilines and bases.

Combining the distinctive monolithic column architecture with the unique advantages of COFs to create COF monolithic columns is another tactic to obviate the drawbacks of using bare COFs for HPLC applications. PAHs, phenols, anilines, NSAIDs and benzothiophenes can be separated using methacrylate-bonded COF monolithic columns, for example, poly(TpPa-MA-co-EDMA) monolithic columns [131].

Tetrahedral tetra(4-anilyl)methane was united with a tetra-aldehyde (produced from the favored chiral tetra-aryl1,3-dioxolane-4,5-dimethanols backbone) to create a 3D CCOF [132]. This resulting CCOF undergoes imine linkage oxidation resulting in an amide-linked framework with preserved crystallinity, persistent porosity and improved chemical stability. These CCOFs are employed in HPLC as CSPs to separate racemic alcohols, sulfoxides, carboxylic acids and esters.

Immobilizing several biological molecules (amino acids, peptides and enzymes) covalently into achiral COFs enriches the chirality in COFs. The provided biomolecules CCOFs will function as flexible and extremely effective CSPs for separation of different racemates through normal and reverse-phase HPLC, inheriting strong chirality and particular interactions from the immobilized biomolecules [133].

COFs for CEC

CEC is a precise isolation technique that combines the benefits of HPLC and capillary electrophoresis [12]. One of the most popular CEC variants, open-tube CEC (OT-CEC) has a poor phase ratio and a small column capacity. However, because of their large surface areas and plentiful organofunctional groups, COFs have a significant likelihood of addressing the aforementioned limitations because of the property of accessible alteration with porous materials of OT-CEC columns.

COF-LZU1 were used as the stationary phase in OT-CEC [134]. The 3-glycidoxypropyltrimethoxysilane-modified capillary was occupied with COF-LZU1 dispersion to create the LZU1-coated capillary. Alkylbenzenes, PAHs and anilines were all successfully separated. High resolution and separation skills were produced by LZU1's hydrophobic interaction and superior size selectivity. COF-LZU1 is an imine-based COFs with appealing qualities like geometric periodicity, rigidity and high porosity. During OT-CEC, the Schiff base reaction was used to create the COF-LZU1 epitaxial growth on the inner capillary column walls [135]. Good stability and reproducibility were observed in the baseline separation of amino acids, neutral analytes and NSAIDs.

COFs in drug delivery formulations

As many drugs have a limited biological half-life, regulated or sustained drug delivery is required [136]. Because 3D COFs are extremely stable and have significant affinity for drug molecules, they are ideal for the controlled release of medications.

Triazine triphenyl imine COFs were produced by heating a 1:1 mixture of triazine triphenylamine and triazine triphenyl aldehyde with the assistance of a catalytic acetic acid using the solvent mesitylene/dioxane [137]. The liberated electron pairs on the imine nitrogens of this triazine triphenyl imine COF are reserved for reversible noncovalent interactions that bind the guest molecules. For the selective absorption and delivery of quercetin as a model medication, these interactions are utilized. This emphasizes the probable use of COFs as nanocarriers for the delivery of medications that might not otherwise be soluble or transportable across biological barriers.

The expanded 3D framework structures PI-COF-4 and PI-COF-5, respectively, were created by immidizing pyromellitic dianhydride with 1,3,5,7-tetraaminoadamantane and tetra(4-aminophenyl) methane [138]. These 3D PI-COFs were employed to regulate drug delivery in vitro since they exhibit elevated loadings and maximum release control, and their large pores and surface area encouraged this use.

A 3,30-dimethoxybenzidine building block and linking unit 1,3,5-triformylbenzen were used to design and synthesize imide-linked DT-COF material [139]. This material was -tested as a drug transporter by lading and releasing carboplatin (CP) in vitro. To calculate the collective drug release, the CP-DT-COF was tested at pH = 7.4 (physiological pH of normal cells) and pH = 5.0 (physiological pH of cancer cells). The release rates of CP from CP-DT-COFs changed at various pH values when the cumulative release percenage of CP for pH = 5.0 and physiological pH 7.4 were compared. When the pH reached the desired level for cancer cells, the CP was quickly released from the DT-COF molecule, which was specifically designed to hold the drug at physiological pH.

COFs with regularity in nanoscale-sized pores can be created specifically to accommodate organic building blocks with reactive groups of functional importance on their outermost layers. They are thus a desirable alternative to chemotherapy as a cancer agent. Ethylenedianiline-triformyl phloroglucinol, a permeable ecodegradable nitrogen-containing COF material produced through the Schiff base condensation reaction of 4,4′-ethylenedianiline and 2,4,6-triformylphloroglucinol, demonstrated enhanced cytotoxicity against the cancer cells HCT 116, HepG2, A549 and MIA-Paca2 [140]. The characteristic apoptotic changes in ethylenedianiline-triformyl phloroglucinol-induced cell death include nuclear condensation, DNA breakdown, externalization of phosphatidylserine followed by elimination of mitochondrial membrane potential, overexpression of proapoptotic proteins and suppression of antiapoptotic proteins.

Using a straightforward click chemistry with azide monomer and alkyne, a thioether-ended triazole bridge-containing COF (TCOF) was created for dual-sensitive (pH and glutathione [GSH]) anticancer drug delivery systems [141]. Due to its flexibility, PEG was easily added to the synthetic COF to create a stable TCOF (TCOF-PEG) colloidal solution. When loaded with the medication doxorubicin (DOX), The TCOF-DOX-PEG exhibited sensitivity to lysosomal pH 5 and GSH conditions. Due to the dynamic nature of triazole, DOX release increased fourfold in a GSH environment (as opposed to pH 7.4) and threefold in a pH 5 setting.

The 8-hydroxyquinoline-enriched COF, COF-HQ, has been used as a possible nanocarrier for drug delivery and regulated release because it exhibits long-lasting crystal structure, appropriate aperture dimension, high distribution in physiological solution and pH sensitivity [142]. A 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) drug-loading experiment demonstrated that the addition of quinoline groups considerably increased COF-HQ's drug uploading capacity. Due to the quinoline groups' and C=N's sensitivity to pH, the drug release profiles of 5-FU from 5-FU-loaded COF-HQ under various pH levels demonstrated that the drug's release was pH-dependent.

Based on density functional theory, an analysis of the effects of biguanide and metformin on COF-B and COF-Al was conducted [143]. Across the various configurations of the electron-rich cavity on the COF surfaces, biguanide and metformin showed excellent interplay. The type and degree of associations between the drug molecule and the COF surfaces were anticipated by the evaluation of the quantum theory of atom in molecules. Both medications had great adsorption on the COF surfaces, according to the estimated electrical and structural properties. The results of stabilization energies after drug molecule engagement indicate that the COF surfaces under investigation are stable and have potential as biguanide and metformin delivery systems.

Applications of advanced science in COFs

The C-MOF coassembly created by the Feng group was used for C2H2, C2H2, C2H2, CH2 and NH3 absorption. Compared with nonpartitioned MOF materials, the absorption of the previously mentioned gases by C-MOF coassembly was significantly increased. CO2/CH4 can also be successfully separated by MOF/COF composite membranes. To address diverse industrial contaminants, MOF/COF composites have been employed as competitive solid-phase adsorbents or extractants, as shown in Figure 3 [144]. For instance, a MOF-5/COF hybrid is a strong adsorbent for concomitant elimination of auramine O and rhodamine B dyes through different noncovalent interactions (e.g., electrostatic, H-bonding and -stacking). Utilizing the electrochemical impedance spectroscopy method, Ce-MOF@COF hybrids were used to detect minute amounts of oxytetracycline.

Figure 3.

Integration of covalent organic frameworks and metal-organic frameworks.

Computational screening of COFs

As more and more COFs are being synthesized [145], it is impractical to evaluate the extraction capabilities of large numbers of COFs using only experimental methods. To narrow down the best choices for future experimental studies, high-throughput computational screening of materials is helpful in examining the gas-dissociation capabilities of an extensive range of components. Computational evaluation [146] of scientifically synthesized COFs for different purposes was made easier by the generation of COF databases like computation-ready experimental COFs (CoRE COFs) and clean, uniform and refined with automatic tracking from experimental databases (e.g., CURATED) COFs [147,148].

For the evaluation of CO2/H2 combination isolation capabilities of COFs, five distinct cyclic adsorption processes, including pressure swing adsorption, vacuum swing adsorption, temperature swing adsorption, pressure-temperature swing adsorption, vacuum-temperature swing adsorption and grand canonical Monte Carlo simulations were processed. H2 preservation and CH4 delivery ability were examined in the CoRE COF database. For adsorbent-based noble gas separations under pressure swing adsorption and vacuum swing adsorption conditions, the computational evaluation of 187 CoRE COFs revealed that COFs can have excellent functional abilities for Kr and Xe in addition to strong sorption of Kr/Ar, Xe/Kr and Rn/Xe.

For helium purification, computational COF screening has been carried out [149]. Crystallographic data for COF structures was taken from the CURATED COF database, which contains over 688 types of experimentally synthesized COF structures. There is no partial occupation or structural disarray because all structures have been cleared of solvent molecules. This technique makes use of a variety of highly permeable polymers. An exceptional helium-selective COF and densely porous polymer phase work together to produce a membrane with exceptional Helium separation.

To go beyond COFs' present performance thresholds, ionic liquids must be incorporated [150]. However, it is impossible to synthesize and test all possible ionic liquid COF combinations [151]. However, utilizing a multifaceted computational screening method that combines the conductor-like screening model for realistic solvents method, grand canonical Monte Carlo, molecular dynamics simulations and density functional theory calculations, the CO2/N2 distinction capabilities of ionic liquid COF [152] composites can be improved based on both adsorption and membranes.

One effective technology for solvent separation is organic solvent nanofiltration (OSN) [153]. The membranes must have appropriately dimensioned apertures for quick solvent infusion and a fine pore size distribution to distinguish between components of parallel sizes to provide efficient and high-performance OSN. Several computationally generated 2D COF membranes with various functional groups and pore diameters have been used. In a study by Wei and colleagues using 245 sets of molecular simulations, 7 ultrathin COF membranes were evaluated for OSN of 7 solvents (acetonitrile, acetone, methanol, ethanol, isopropanol, methyl ethyl ketone and n-hexane) and four solutes (2,5-furandiamine, paracetamol, α-methylstyrene dimer and Nile red) [154] .

Conclusion

The potential of COFs remains a significant area that must be thoroughly investigated in terms of materials science. Porous structures are essential for multiple processes, including catalysis, ion conduction, gas sorption, storage and separation and energy storage. In separation science, from sample pretreatment (SPE and SPME) to chromatography (GC, HPLC, CEC) for a variety of targets, it has been demonstrated that COFs are promising, with key characteristics. To satisfy the requirements of various separation technologies and to enhance the degree of separation and selectivity, COF composites and bulk COF partials have been created. Solid-state NMR investigations have shown that imine-based COFs exhibit hydrogen-bonding interactions with guest molecules in the context of drug administration because they possess crucial characteristics including crystallinity and porosity. The unbound electron pairs on the imine nitrogens of this form of COF are located to noncovalently attach the intruder molecules reversibly. For the precise attachment between COF pores and drug molecules, these noncovalent interactions are employed. The drug encapsulated in the COF results in a decreased multiplication rate when related to direct drug delivery, according to proliferation control assays employing human breast cancer cells. The promise of this class of polymers is highlighted by the sensible incorporation of host–guest interactions through hydrogen bonding into the plan of nanocarriers for drug delivery. This is especially true for the supervision of medications have difficulty traversing cell membranes. Recent reports of free-standing poly-COF membranes have given the creation of unceasing COF membranes with exceptional mechanical characteristics and higher separation performance fresh life.A thorough review of the research being done on COF materials used in separation applications, such as extraction of gases, conditioning of water, chiral separation, OSN and so on was provided. To create enhanced separation methods, we anticipate that this work will provide guidance for the creation and production of functional COFs and act as a catalyst for further advancements in this emerging field.

Future perspective

Expanding the boundaries to include biological sensors or biomarkers, which is a prospective future path for the field, will require further structural engineering in the creation of novel fluorescent and phosphorescent COF components. To increase the usefulness of COFs in separation science, careful design and the blending of COFs with additional functional components should be done. Recent advancements have shown the great potential of COFs for the removal of toxic metals such as mercury from aqueous solutions. This research should be further reinforced and broadened to cope with various environmental contaminations in air, water and soil. As for biorelated applications, rather than MOFs with toxic metal species, COFs could provide a unique platform for creating a predesigned nanospace with specifically sequenced docking sites. Efforts in this direction will pave the way to the selective encapsulation and separation of biomolecules in an efficient manner. In the case of drug delivery, the biocompatibility and toxicity of COFs must be documented in detail, and the design of skeletons without toxicity is a minimum requirement. Practical implementation is mainly based on further achievements in the chemistry, physics and materials science of COFs.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the National Institute of Pharmaceutical Education and Research (NIPER), Hyderabad, India, for its valuable insights in preparing the manuscript. The authors thank the Department of Pharmaceuticals, Ministry of Chemicals & Fertilizers, Government of India, New Delhi, for a NIPER fellowship award. This manuscript bears the NIPER-Hyderabad communication number: NIPER-H/2023/.

Financial disclosure