Abstract

Protein kinases are responsible for a myriad of cellular functions, such as cell cycle, apoptosis, and proliferation. Because of this, kinases make excellent targets for therapeutics. During the process to identify clinical kinase inhibitor candidates, kinase selectivity profiles of lead inhibitors are typically obtained. Such kinome selectivity screening could identify crucial kinase anti-targets that might contribute to drug toxicity and/or reveal additional kinase targets that potentially contribute to the efficacy of the compound via kinase polypharmacology. In addition to kinome panel screening, practitioners also obtain the inhibition profiles of a few non-kinase targets, such as ion-channels and select GPCR targets to identify compounds that might possess potential liabilities. Often ignored is the possibility that identified kinase inhibitors might also inhibit or bind to the other ~30,000 proteins in the cell that are not kinases, which may be relevant to toxicity or even additional mode of drug action. This review highlights various inhibitors, which have been approved by the FDA or are currently undergoing clinical trials, that also inhibit other non-kinase targets. The binding poses of the drugs in the binding sites of the target kinases and off-targets are analyzed to understand if the same features of the compounds are critical for the polypharmacology.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

The human kinome consists of over 530 protein kinases, many of which are associated with the initiation and progression of cancer and other diseases.[1] Kinases are responsible for numerous important cellular functions, including cell cycle, apoptosis, and proliferation. Because of this, kinases make excellent targets for therapeutics, including anti-cancer, anti-inflammatories, and more. As of early 2024, the U.S. FDA has approved 80 small-molecule kinase inhibitors, and the last five years have seen an unparalleled success in the discovery of these novel therapeutics. About 150 kinase-targeted therapies are currently undergoing clinical trials, and numerous other kinase inhibitors are in pre-clinical stages of development.[2] The workflow of the development of these small molecule kinase inhibitors, as outlined in Figure 1, commonly involves compound hit identification, design and development of structure-activity relationship (SAR) through screening for the selected target, pre-clinical in vitro and in vivo efficacy studies, pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics evaluation, and toxicity screening, followed by lead optimization to identify a clinical candidate, which is subjected to clinical trials, in hopes of obtaining FDA approval. Typically, during this developmental process, anti-targets are screened; however, it is common that this toxicity-related selectivity screening is only focused within the kinase domain and safety panels, like CEREP panels, that screen for specific targets, such as ion channels (hERG) and G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs), that have well characterized pharmacological toxicities. Because of this, therapeutic responses are usually attributed to the inhibition of the target kinase, while synergistic effects from non-kinase targets are not fully elucidated.

Figure 1.

Workflow for the development of kinase inhibitor drugs. Figure created using BioRender.

In recent years, the emergence of in silico experimentation and more reliable methods of molecular docking have provided a cost-effective means of predicting non-kinase targets of kinase inhibitors. Furthermore, emerging machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence methods have provided powerful tools to evaluate the comprehensive profiles of drugs. While many reports and reviews have discussed the kinase off-targets of many kinase inhibitors,[3,4] there is a paucity of reviews that have focused on non-kinase targets of kinase inhibitors, although such non-kinase targeting could contribute to kinase inhibitor efficacy or toxicity. A few review articles have also addressed the issue of non-kinase targets of kinase inhibitors, but these articles are about seven or more years out, and considering that the last few years have seen an explosion of drugs approved by the FDA that target kinases, it is timely to provide an update of non-kinase targets of kinase inhibitors.[5,6] In addition to providing an update on the topic, this review also compares the binding poses of the drugs in the binding sites of the target kinases and off-targets to provide some insights regarding the chemical features that are critical for the polypharmacology.

Competitive kinase inhibitors & non-kinase off targets

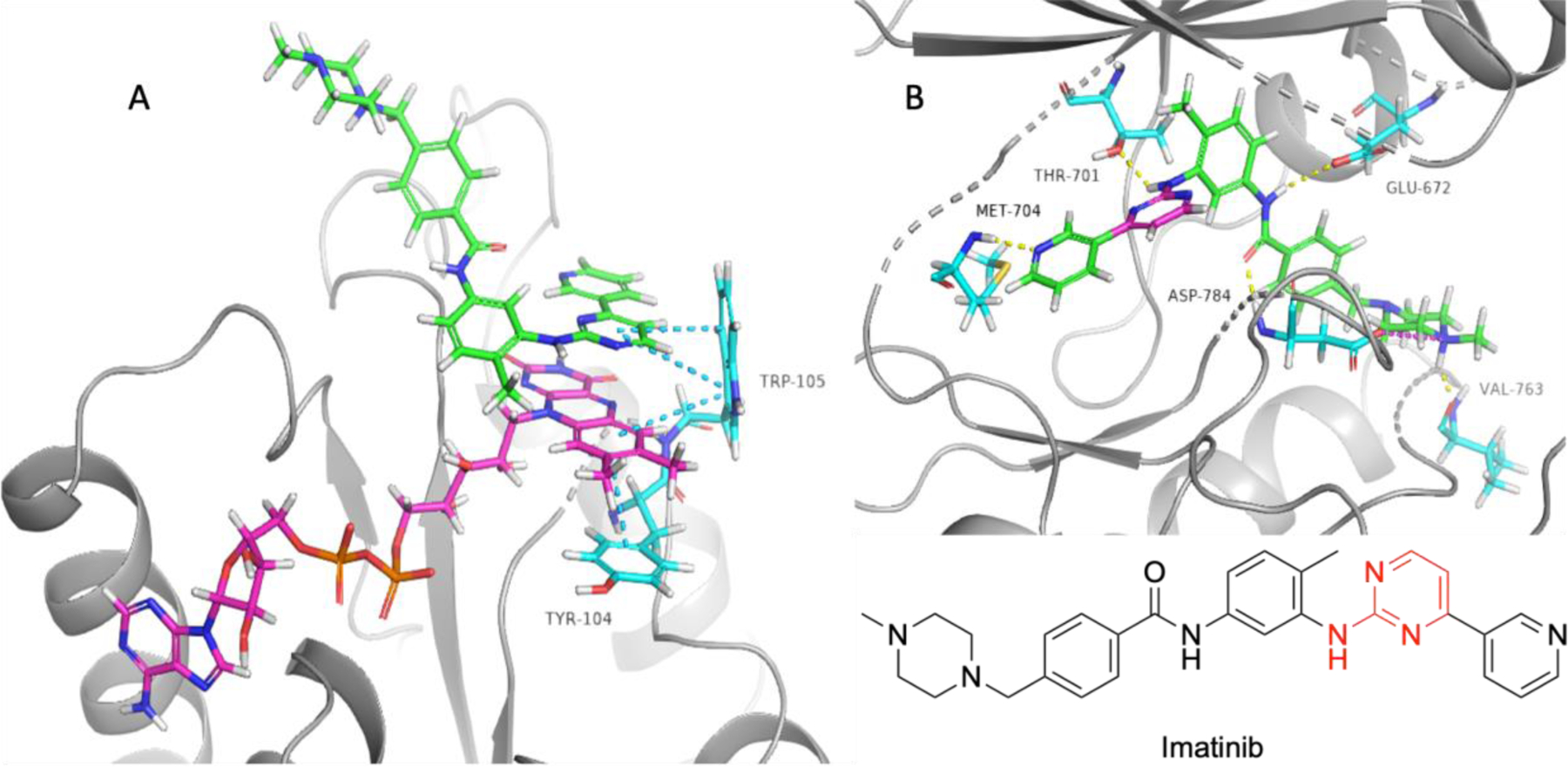

In 2001, the FDA approved imatinib, a first-in-class tyrosine kinase inhibitor that revolutionized modern medicine. Imatinib was originally designed through structure-based techniques to target the inactive conformation of the BCR-ABL mutated kinase and is used for the treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML).[7] It was later found that imatinib is a potent inhibitor of tyrosine kinases, including platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR), c-Kit, and discoidin domain receptor 1 (DDR1), which subsequently led to its approval to treat several additional solid and blood cancers.[8] Several years after the FDA approval, a proteomics study revealed that imatinib inhibits non-kinase target NADPH quinone oxidoreductase 2 (NQO2) with an IC50 of 82 nM, a potency that is within physiological relevance at clinical dosing.[9,10] NQO2 is involved in xenobiotic metabolism and is highly expressed in healthy kidney and liver tissues, was well as in a variety of cancers.[11] Inhibition of NQO2 has been shown to cause myeloid hyperplasia as well as increased sensitivity to chemical carcinogenesis.[9] To date, there have been no studies that directly investigate the role of effect NQO2 inhibition in imatinib-treated cancer cells. A number of mild adverse side effects of imatinib have been reported, including diarrhea, edema, and muscle cramping, but it is still unknown whether inhibition of NQO2 plays a role in these adverse effects. A crystal structure of imatinib bound to NQO2 has been solved and is represented in Figure 2. Imatinib binds to the active site of NQO2 through a pi-pi stacking interaction between the pyrimidine moiety and tryptophan residue, Trp105. The 2-aminopyrimidine moiety is essential for binding in kinases; hinge residue from DDR1 (Thr701) participate in hydrogen bonding with the secondary amine. Ligand interactions with the hinge involves interactions with the protein backbone. Several moieties within imatinib participate in critical hydrogen bonding, pi-cation interactions, or salt bridges in the DDR1 kinase that is not observed in the NQO2 crystal structure. The pyridine moiety participates in hydrogen bonding with the backbone of hinge residues Met704 in DDR. Both kinases generate several hydrogen bonding interactions with the amide moiety, including interactions with aspartic acid residues in the DFG motif. The piperazine moiety also makes strong salt bridge and pi-cation interactions with DDR1.

Figure 2.

Crystal structures of imatinib bound to NQO2 (PDB: 3FW1) and DDR1 (PDB: 4BKJ). A) Imatinib bound to NQO2. Imatinib is represented in green, FAD cofactor is represented in yellow, NQO2 residues are represented in aqua, blue dashes represent pi-pi stacking interactions. B) Imatinib bound to the inactive conformation of DDR1. Imatinib is represented in green, with pyrimidine moiety responsible for NQO2 binding shown in magenta. Yellow dashes illustrate hydrogen bonding, magenta dashes show salt bridges, green dashes portray pi-cation interactions. Red coloring in compound structure of imatinib indicate moieties that participate in positive interactions with both NQO2 and DDR1.

Nilotinib was approved by the FDA in 2007, also for the treatment of CML. The structure of the second generation BCR-ABL kinase inhibitor is highly homologous to and was rationally designed based on its predecessor, imatinib, and was developed to increase potency in response to the occurrence of imatinib resistance.[12] The minute changes observed in the structure of nilotinib resulted in a 20-fold increase in potency of BCR-ABL and translated into an effective clinical treatment of imatinib resistant CML while retaining its activity against c-Kit, PDGFRα, and DDR1.[13] As expected, nilotinib does inhibit non-kinase target NQO2, although less than imatinib, with an IC50 of 380 nM.[9,10] It was also found the nilotinib shows inhibitory activity against Smoothened (SMO), a component of the Hedgehog (Hh) signaling pathway, at clinically relevant concentrations (Hh/SMO pathway inhibition IC50 of 374 nM). The Hh pathway is thought to be important in the survival of cancer stem cells, a subpopulation of cancer cells which enables tumor persistence, usually leading to relapse.[14] Aberrant Hh pathway activation (Figure 3) is found in numerous cancers, including myeloid leukemia,[15] glioblastoma,[16] and basal cell carcinoma (BCC).[17] Recent studies have shown that Hh pathway inhibition could increase sensitivity of cells to cytotoxic drugs, and tumors with dysregulated Hh pathway signaling responded well to SMO antagonists.[14] Thus, SMO inhibition could be contributing to the clinical efficacy of nilotinib at typical recommended dosing of 400 mg twice daily (average maximum concentration of the drug in plasma (Cmax) of 1644 ng/mL).[18] Although the crystal structure of nilotinib bound to SMO has not been solved, Chahal and colleagues utilized in silico molecular docking techniques, using ligand-based 3D atomic property field (APF) models and SMO pocket docking for binding pose prediction and utilizing docking results of known inhibitors of SMO, including vismodegib, to validate their findings, to predict the binding conformation of nilotinib to SMO. It was predicted that the 2-aminopyrimidine moiety and the pyridine moiety engage in hydrogen bonding interactions with the SMO binding pocket.[14] The exact binding pattern of nilotinib to SMO cannot be confirmed without co-crystallization, however, if nilotinib is interacting with the binding cavity of SMO as suggested, the 2-aminopyrimidine and pyridine moieties are excellent candidates to participate in hydrogen bonding, which is observed in the hinge region of the ABL1 kinase.[14]

Figure 3.

Hh pathway. In the absence of hedgehog (Hh) ligand, Patched (PTCH) protein inhibits the activity of Smoothened (SMO), which prohibits the disassociation of transcription factor GLI from suppressor of fused (SUFU) protein, inhibiting gene transcription. Upon PTCH activation via Hh ligand binding, SMO is activated, allowing GLI to dissociate from SUFU, inducing gene transcription. Figure was created using BioRender.

Dasatinib, another second generation BCR-ABL tyrosine kinase inhibitor, was approved by the FDA in 2006. Unlike imatinib and nilotinib, dasatinib was designed as a Src kinase family inhibitor and potently inhibits a host of kinases, such as c-Src, lymphocyte-specific protein tyrosine kinase (LCK), c-Kit, and Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK).[19] Dasatinib has been shown to be 325-fold more potent than imatinib and is highly effective in treating various forms of leukemia, including imatinib-resistant CML.[20] Interestingly, due to the structural differences compared to imatinib and nilotinib, dasatinib was found to not bind to NQO2 at clinically relevant concentrations.[10] However, dasatinib has been shown to weakly bind transthyretin (TTR), a thyroid hormone transport protein that resides within the blood plasma.[21] While transthyretin has not been linked to cancer, several authors have discussed the clinically significant effects of protein binding on the pharmacokinetic (PK) properties of a drug.[22] Plasma protein binding is typically associated with poor compound solubility and is a result of entropic effects. A crystal structure of dasatinib bound to transthyretin, as shown in Figure 4, reveals a pi-cation interaction between Lys15 and the 4-aminopyrimidine moiety. The 4-aminopyrimidine moiety participates in hydrogen bonding within the hinge region of c-Src and appears to extend into the solvent exposed area. The thiazole and chlorophenyl moieties participate in key interactions to c-Src that are not important for transthyretin binding. Hinge residue Met343 hydrogen bonds to both the 4-aminopyrimidine and the thiazole, while the chloro engages in a halogen bonding interaction with the backbone of aspartic acid residue Asp404, part of the DFG motif.

Figure 4.

Crystal structures of dasatinib bound to transthyretin (PDB: 7ERK) and c-Src (PDB: 3G5D). A) Dasatinib bound to thyroid hormone transport protein transthyretin. B) Dasatinib bound to the active conformation of c-Src. Dasatinib is illustrated in green with magenta representing the pyrimidine moiety responsible for primary binding to transthyretin. Yellow dashes represent hydrogen bonding interactions, green dashes represent pi-cation interactions, magenta dashes represent halogen bonding interactions. C) Polar surface model of dasatinib bound to transthyretin. D) Polar surface model of dasatinib bound to c-Src kinase. Blue shading is electronegative, red shading is electropositive. Red coloring in compound structure of dasatinib indicate moieties that participate in positive interactions with both transthyretin and c-Src.

Sorafenib, FDA approved in 2005, is an orally bioavailable multi-kinase inhibitor that was originally designed as a Raf1 inhibitor.[23] Its phenotypic activity, however, is generally attributed to its ability to target numerous kinases within the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathway, namely vascular endothelial growth factor receptors (VEGFRs), PDGFRs, c-Kit, and FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3 (FLT3).[23] Sorafenib was originally approved for the treatment of renal cell carcinoma (RCC), and was later approved to treat hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and differentiated thyroid carcinoma (DTC).[24] In 2013, it was reported that sorafenib inhibits off-target system Xc (also known as cystine/glutamate antiporter).[24] This transporter imports a molecule of cystine from outside the cell in exchange for one molecule of glutamate from inside the cell, and inhibition of system Xc can lead to ferroptosis (Figure 5).[25] Ferroptosis is a non-apoptotic form of cell death characterized by the extensive lipid peroxidation downstream of the metabolic dysfunction.[26] Despite the numerous reports that have accumulated regarding sorafenib’s induction of ferroptosis via system Xc inhibition, recent experimentation has shown that sorafenib is not a robust system Xc inhibitor or ferroptosis inhibitor in a wide range of cell lines, including numerous human hepatoma cells, unlike inhibitors sulfasalazine and erastin.[27] It has been shown that sorafenib exhibits low selectivity and, therefore, may trigger many other lethal mechanisms. Sorafenib has also been shown to bind phosphodiesterase 6D (PDE6D) with a dissociation constant (Kd) of 1.23 μM, which is clinically relevant at recommended dosing.[28] It was found that PDE6D is commonly overexpressed HCC, including in sorafenib resistant strains of HCC, and contributes to sorafenib resistance.[29] Additional studies are needed to elucidate the role of PDE6D inhibition within sorafenib treated cells.

Figure 5.

Ferroptosis pathway. Cell death via ferroptosis is induced in times of excess lipid peroxidation, which can be generated from lipoxygenases, cytochrome P450 oxidoreductases, and via the iron catalyzed Fenton reaction. Excess iron within the cell originates from breakdown of ferritin storages, or through iron uptake through transferrin receptors, which transport Fe3+ into the cell. Iron is reduced by STEAP3 (six-transmembrane epithelial antigen of prostate 3) and DMT1 (divalent metal transporter 1). Lipid peroxidases can be reduced by glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4), which is regulated by glutathione concentrations within the cell. The system Xc is responsible for maintaining sufficient levels of glutathione limiting reagent, cysteine, within the cell in exchange of glutamate, which is also required for glutathione synthesis. This synthesis is catalyzed by glutamate-cysteine ligase (GSL) and glutathione synthetase (GSS). Figure was created using BioRender.

Fostamatinib, previously known as R788, is the first FDA approved spleen tyrosine kinase (SYK) inhibitor. Fostamatinib is approved for use in adults with chronic immune thrombocytopenia purpura, or ITP. Fostamatinib is a phosphate containing prodrug which, when subjected to intestinal microsomes in vivo, is quickly metabolized by phosphatases to form the active metabolite, R406; R406 inhibits SYK with an IC50 of 41 nM.[30] A study performed by M. G. Rolf et. al. quantified non-kinase off-target activities, and R406 was found to inhibit adenosine A3 receptor (A3AR) (IC50 = 18 nM) at a clinically relevant concentration.[31] Further investigation into the antagonist activity of R406 against A3AR demonstrated that R406 acts as a functional inhibitor of adenosine uptake. Adenosine uptake plays a major role in the regulation of extracellular adenosine concentrations, and it has been previously shown that higher levels of extracellular adenosine can protect against organ tissue damage.21 Specifically, dipyridamole and dilazep, which are both known adenosine uptake inhibitors, are known to have anti-thrombotic effects.[33] Since ITP is characterized by a significant decrease in the number of platelets in the blood, it is possible that the A3AR inhibitory property of R406 is contributing to its efficacy. In terms of side effects, an increase in blood pressure has been reported in many patients taking R406, but it is unlikely that inhibition of adenosine uptake is the cause.[31]

Gefitinib, which was FDA approved in 2003, is an oral inhibitor of epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase (EGFR) with an IC50 value of 33 nM.[34] Gefitinib is approved for the treatment of breast cancer and non-small cell lung cancer. Although efficacious, gefitinib use is associated with numerous side effects, including life-threatening interstitial lung disease (ILD), which could be due to its inhibition of off-targets.[35] Verma and coworkers utilized a structure-based systems biology approach to identify off-targets of gefitinib and found gefitinib inhibits numerous non-kinase targets, including potent inhibition of mitochondrial dihydroorotate dehydrogenase (DHODH) and estradiol 17-beta-dehydrogenase 1 (HSD17B1). In their study, they utilized the binding energy calculated via docked poses to predict the binding affinity and found the binding energy of gefitinib to be −100.487 kcal/mol and −97.635 kcal/mol for DHODH and HSD17B1, respectively; for reference, gefitinib to EGFR docking shows a binding energy of −88.354 kcal/mol (Ki = 0.4 nM).[36] It is possible that DHODH is the responsible target for ILD; administration of leflunomide, a known DHODH inhibitor, has also been found to induce interstitial lung disease.[37] Despite the intensive computational experimentation, it is important to note that DHODH and HSD17B1 antagonism by gefitinib have not been confirmed in vitro or in vivo, and the link to clinically observed side effects is merely speculative.

Axitinib is a second-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitor that was approved by the FDA in 2012 for the treatment of renal cell carcinoma. Axitinib potently inhibits VEGFR1/2/3, PDGFR, and c-Kit with IC50 values less than 5 nM.[38] Originally designed as a VEGFR inhibitor, axitinib boasts a superior selectivity profile than its first-generation counterparts, inhibiting no targets outside of VEGFRs, PDGFR, and c-Kit at a concentration of 20 nM.[39] However, outside of the kinome, axitinib shows off-targeted inhibition of E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase (SHPRH) and mediator of RNA polymerase II transcription subunit 23 (MED23), and these two targets can also be associated to the clinical efficacy of Axitinib.[40] SHPRH is a protein that shares many of the characteristics of DNA repair proteins, as it assists in maintaining genomic stability by reducing the amount of DNA damage errors.[41] SHPRH is known to be responsible for blocking Wnt signaling; in cancer, Wnt signaling is highly expressed and is known to aid in cancer stem cell renewal (Figure 6).[40,42,43] MED23, on the other hand, is responsible for mediating transcription by promoting monoubiquitylation of histone H2B at lysine-20, but is also believed to be associated with the Wnt signaling pathway.[44] It was found that at 10 μM, axitinib significantly increased the SHPRH protein stability, and later found that SHPRH is required for axitinib mediated Wnt signaling, which was observed at 5 μM axitinib concentration.[45] At current clinical dosing (5 mg twice daily, Cmax of 27.8 ng/mL), it is unlikely these Wnt suppressing effects are observed through the stabilization of SHPRH.[46]

Figure 6.

Wnt signaling pathway. Wnt pathway is activated when Wnt binds to the frizzled and lipoprotein receptor-related protein (LRP), which interacts with and activates disheveled, which inhibits a protein complex consisting of axin, glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK-3β), casein kinase 1α (CK1α), and Adenomatous Polyposis Coli (APC) tumor suppressor, allowing β-catenin to bind to T-cell specific factor (TCF) and lymphoid enhancer-binding factor (LEF), inducing gene transcription. Upon Wnt pathway inhibition, the protein complex of axin, GSK-3β, CK1α, and APC phosphorylates β-catenin, inducing degradation. Figure created with BioRender.com.

Vemurafenib was approved by the FDA in 2011 for the treatment of metastatic melanoma with BRAF mutation V600E, and was later approved for the treatment of Erdheim-Chester Disease, a rare blood disease for which there was no treatment.[47] Vemurafenib was developed as an inhibitor for Raf kinases using a scaffold-based design approach, and it selectively inhibits the mutated BRAF V600E over the wild type by about 3-fold.[48] Alectinib was FDA approved in 2015 for the treatment of ALK-positive NSCLC.[49] Alectinib was designed as a second-generation inhibitor of ALK and was developed through the use of high-throughput screening.[50] Alectinib potently inhibits both ALK (IC50 = 1.9 nM) and RET (IC50 = 4.8 nM).[50,51] Both vemurafenib and alectinib have been discovered to inhibit ferrochelatase (FECH), an enzyme in the heme biosynthesis pathway that converts protoporphyrin IX (PPIX) to functional heme.[52] A common side effect of both vemurafenib and alectinib is the development of photosensitivity; inhibition of FECH leads to protoporphyrin accumulation, which is directly linked to photosensitization.[47,52] Therapeutic potential of FECH inhibition remains underexplored, as no drug-like direct FECH inhibitors are known. However, FECH inhibition is known to be antiangiogenic, so it is possible these compounds could be used as treatment options outside of cancer, such as in ocular disease.[53] A number of kinase inhibitors have been identified to bind FECH with micromolar affinities, including crenolanib, alectinib, axitinib, nilotinib, and vemurafenib, which are clinically relevant concentrations.[54]

Dabrafenib was first FDA approved in 2013 for the treatment of melanoma and gained additional approval through combination therapy with trametinib for the treatment of melanoma, NSCLC, anaplastic thyroid cancer (ATC), and low-grade gliomas, all of which are BRAF V600E positive. Developed as a BRAF V600E inhibitor, dabrafenib shows potent inhibition of both wild type BRAF and mutant BRAF, with IC50 values of 3.2 nM and 2 nM respectively.[55,56] Dabrafenib has also been discovered to be an agonist of the human pregnane X receptor (hPXR), with EC50 values ranging from 82 to 110 nM.[57] hPXR is a powerful regulator of the transcription of metabolizing enzymes and transporters.[57] Activation of the hPXR receptor has been shown to induce drug resistance in breast cancer cells.[58] Furthermore, an increase in cytochrome p450 (CYP) enzymes have been shown to cause adverse drug-drug interactions, causing an increased awareness of hPXR as a possible off target in drug development.[59,60] Crystal structures of dabrafenib bound to its kinase target BRAF V600E and non-kinase target hPXR have been solved and are represented in Figure 7. The sulfonamide moiety is the major contributor to the binding of dabrafenib to hPXR, forming a hydrogen bond with Ser247. This moiety is also important for the kinase binding affinity and makes numerous interactions with the conserved lysine residue Lys483, and the backbone of DFG motif residues Asp594 and Phe595. The 2-aminopyrimidine moiety plays an essential role in binding to BRAF V600E, engaging in two hydrogen bonding interactions with the backbone of hinge residue Cys532, while avoiding any interactions with hPXR.

Figure 7.

Crystal structures of dabrafenib bound to hPXR (PDB: 6HJ2) and BRAF V600E (PDB: 4XV2). A) Dabrafenib bound to hPXR. B) Dabrafenib bound to BRAF V600E. Dabrafenib is represented in green and magenta, with magenta representing moieties interacting with hPXR non-kinase off target. Yellow dashes represent hydrogen bonding interactions, aqua dashes represent pi-pi stacking interactions, magenta dashes represent salt bridges. Red coloring in compound structure of dabrafenib indicate moieties that participate in positive interactions with both hPXR and BRAF V600E.

Midostaurin is a multi-kinase inhibitor that was FDA approved in 2017 for the treatment of AML. Midostaurin, originally discovered to inhibit kinases in 1986, is a natural product of Streptomyces staurosporeus and has activity against FLT3, FLT3 mutants, PDGFRs, VEGFR2 and c-Kit.54 Midostaurin is also an inhibitor of the enzyme aldo-keto reductase 1C3 (AKR1C3).[61] The limited in vivo efficacy of midostaurin led to combination therapy with daunorubicin, an anthracycline antibiotic. AKR1C3 mediates the reduction of anthracyclines to their less-active hydroxyl metabolites, so in the context of AML, AKR1C3 plays a critical role in resistance to chemotherapy.[62] Midostaurin was found to inhibit AKR1C3 with a sub-micromolar IC50, well within the clinically relevant concentrations of midostaurin (50 mg bid, Cmax of 1604.9 ng/mL).[61,63] Thus, the synergistic combination of the two drugs can be attributed to midostaurin’s ability to inhibit the inactivation of daunorubicin by AKR1C3.

Dinaciclib was developed as a cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitor that has advanced to phase III clinical trials for the treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).[64,65] Dinaciclib has IC50 values less than 5 nM against CDK1, CDK2, CDK5, and CDK9, while avoiding inhibition of closely related ERK2 and GSK3B.[66] Dinaciclib, like midostaurin, inhibits AKR1C3 with a Kd of 69 nM.[67] Furthermore, dinaciclib has yet to be approved by the FDA due to low efficacy, suggesting possible synergistic effects if used in combination with daunorubicin.[62,64] Currently, there are no clinical trials exploring this possibility.

Palbociclib, another CDK inhibitor, was FDA approved in 2015 to treat hormone receptor(HR)-positive, human epidermal growth factor receptor type 2 (HER2)-negative breast cancer in combination with hormone therapy.[68] Palbociclib selectively inhibits CDK4/D1 and CDK6/D2 with IC50’s of 11 nM and 15 nM, respectively, while avoiding inhibition of CDK1, CDK2 and CDK5.[69] Recently, it was discovered that palbociclib potently binds to and is an inhibitor of STING (Kd of 6.01 nM), a protein integral to immune response in infection, vaccine development, and cancer immunotherapy.[70] The ability to modulate STING activity has implications in both cancer and autoimmune disease. Patients with autoimmune diseases that display overactivation of STING may benefit from an antagonist of STING, while the use of STING agonists has been studied within the Sintim lab as a potential cancer vaccine therapy.[70,71] The inhibition of STING within a cancer therapeutic setting, however, could suppress immune response to cancer cells. Follow-up work is needed to clarify if the strong inhibition of STING by palbociclib makes patients more susceptible to infection. To elucidate the mode of binding for palbociclib to STING, Gao and colleagues performed molecular docking, and used the results to design in vitro STING mutants to elucidate residues that are integral for binding.[70] They determined that STING residue Tyr167 is essential for binding, which was predicted by their docking models. Comparing a crystal structure of palbociclib bound to CDK6 (PDB: 5L2I) and predicted binding of palbociclib to STING (Figure 8) the acetate moiety participates in essential hydrogen bonding interactions within the binding pocket of both STING (Thr267) and CDK6 (Asp163). The pyridinone moiety is predicted to contribute to palbociclib binding affinity in STING, and does not participate in any interactions for CDK6, a possible axis to differentiate the inhibitory activity. Similarly, the 2-aminopyrimidine participates in an essential hydrogen bonding interaction to the hinge region of CDK6.

Figure 8.

Predicted pose and crystal structure of palbociclib bound to STING protein and CDK6 (PDB: 5L2I). A) Predicted binding pose of palbociclib bound to STING protein. Figure adapted from Gao et. al.[70] B) Two-dimensional representation of palbociclib bound to CDK6. Magenta arrows represent hydrogen bonding interactions, green lines represent pi-pi stacking interactions. Red coloring in compound structure of palbociclib indicate moieties that are predicted to participate in positive interactions with both STING and CDK6.

Netarsudil, a potent Rho-associated protein kinase (ROCK) inhibitor, was approved in 2017 for the treatment of glaucoma.[72] Netarsudil has a Ki of 1 nM for both ROCK1 and ROCK2.[72,73] Inhibition of ROCK has been associated with reduced cell contraction, decreased expression of fibrosis-related proteins, and increased trabecular outflow facility and thereby decreased intraocular pressure (IOP). It has been claimed that in addition to ROCK inhibition, netarsudil also inhibits norepinephrine transport (NET), at clinical ocular concentrations.[73] Blocking NET would result in blockage of norepinephrine reuptake at noradrenergic synapses, increasing the duration and strength of endogenous norepinephrine signaling.[74] Additionally, NET inhibition has been shown to lower production of aqueous humor (AH) and decrease episcleral venous pressure.[72] Netarsudil, however, is rapidly metabolized into netarsudil-M1 (half-life of 175 minutes) via esterases within the cornea, but netarsudil-M1 is not claimed to be a NET inhibitor. Therefore, systemic NET inhibition most likely does not contribute to the clinical success of netarsudil.[73]

Entrectinib was approved by the FDA in 2019 for the treatment of ROS1-positive metastatic NSCLC.[75] Entrectinib potently inhibits TRKA, TRKB, TRKC, ROS1, and ALK with IC50 values of 1, 3, 5, 12, and 7 nM, respectively.[76] Tropomyosin-related kinases (TRKs) play important roles in the development and function of neurons of the central and peripheral nervous systems.[76] Additionally, chromosomal rearrangements involving the NTRK1 gene, which encodes the TRKA protein, were reported in cases of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC).[77] Activated ROS1 and ALK tyrosine kinases also occur in NSCLCs.[78] Thus, entrectinib’s pan-TRK, ROS1, and ALK inhibitory activity is most potent in models that are dependent upon ROS1 or ALK fusion proteins.[79] Entrectinib’s non-kinase target, ABCB1, is an efflux transporter; the role of ABC efflux transporters is to protect body organs against xenobiotics.[80] Inhibitory effects of entrectinib on the efflux activities of ABCB1 was observed using an accumulation assay with model cytotoxic substrate drugs.[80] This inhibition of ABCB1 transporters can be used in the future for tumors with an overexpression of ABCB1 in order to resensitize cancer cells.32 Many tyrosine kinase inhibitors have been discovered to interact with transport proteins, such as imatinib, nilotinib, dasatinib, brigatinib, crizotinib, among others.[81] These receptors have been linked to multi-drug resistance in many cancers, which has led to an increased efforts to investigate combination therapies. An in-depth discussion of ABC transporters and their effects on pharmacokinetics lies beyond the scope of this review; a detailed review of TKI’s and their interactions with transport proteins was recently written by Krchniakova and others.[81]

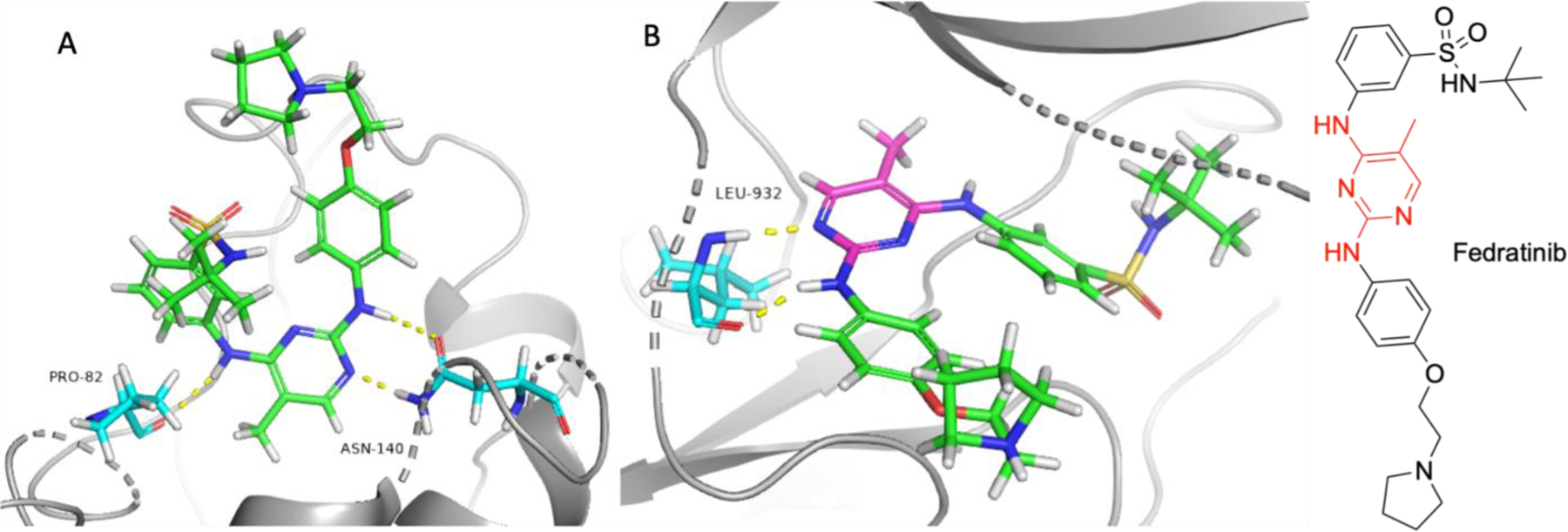

Fedratinib was approved by the FDA in 2019 for the treatment of adults with high risk or intermediate-2 myelofibrosis.[82] Fedratinib is a selective Janus kinase 2 (JAK2) inhibitor with an IC50 of 3 nM.[83] JAK2 plays a vital role in the signaling of normal hematopoiesis.[84] Fedratinib does inhibit other targets which may play a role in the clinical efficacy of this compound, including non-kinase target BRD4, with an IC50 of 130 nM, as well as related BRD2, BRD3, and BRDT.[85–87] The bromodomain and bromo extra terminal domain (BET) family of proteins bind to acetylated lysine residues.[88] BET proteins are epigenetic regulators of gene transcription and are involved in cell growth, differentiation, and inflammation.[89] BRD4 is implicated in the transcription of several oncogenes.[90] Based on initial pharmacokinetics (PK) studies, patients that took 300 mg (recommended dosing is 400 mg per day) showed a Cmax of 971 ng/mL, well above the in vitro BRD4 IC50 of 130 nM, indicating that BRD4 could feasibly contribute to the anti-cancer activity of fedratinib.[91] Dual inhibition of the JAK/STAT pathway and BET inhibition has been shown to synergistically block NF-κβ hyperactivation and inflammatory cytokine production resulting in the reduction of disease burden and reversing bone marrow fibrosis in mice models.[84] A crystal structure of fedratinib binding to BRD4 and JAK2 and is shown in Figure 9. The hinge binding 2,4-diaminopyrimidine moiety shown interacting with JAK2 residue Leu932 also interacts through hydrogen bonding interactions with BRD4 residues Asn140 and Pro82.

Figure 9.

Crystal structure of fedratinib bound to BRD4 (PDB: 4PS5) and JAK2 (PDB: 6VNE). A) Fedratinib bound to BRD4. B) Fedratinib bound to JAK2. Fedratinib is represented in green and magenta, with magenta representing moieties interacting with BRD4 non-kinase off target. Yellow dashes represent hydrogen bonding interactions. Red coloring in compound structure of fedratinib indicate moieties that participate in positive interactions with both BRD4 and JAK2.

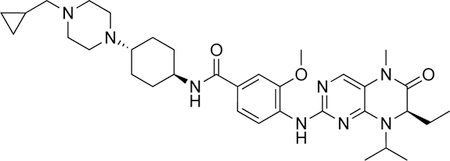

Another known kinase inhibitor with activity against BRD isoforms is volasertib.[86,92] Volasertib, a polo-like kinase 1 (PLK1) inhibitor (IC50 = 0.87 nM) being investigated in patients with AML, recently had its orphan status designated by the FDA withdrawn.[93] PLK1 plays a role in mitosis and is usually found to be overexpressed in several cancers while expressed at a much lower rate in normal non-dividing tissues.[90] Volasertib binds to BRD4 with a Kd of 79 nM. BRD4 inhibition has shown promising effects in preclinical solid tumor models, but single agent treatment has not been found to be effective.[94–97] Thus, a polypharmacological approach, including PLK1/BRD4 and JAK2/BRD4 dual inhibition, is an effective strategy in improving clinical efficacy. Crystal structures of volasertib binding to BRD4 and its main target PLK1 have also been solved and are shown in Figure 10. Akin to the BRD4 crystal structure binding to fedratinib (Figure 9), residue Asn140 participates in hydrogen bonding with the 6-oxo position on the 5,6,7,8-tetrahydropteridine moiety, which also interacts with BRD4 residue Cys136. Additionally, the anisole moiety forms a pi-pi stacking interaction with Trp81, reinforcing the binding affinity. The 5,6,7,8-tetrahydropteridine moiety participates in hydrogen bonding with PLK1 hinge residue Cys133. The amide in volasertib is the only moiety that engages in a hydrogen bonding interaction with PLK1 and not BRD4.

Figure 10.

Crystal structure of volasertib bound to BRD4 (PDB: 5V67) and PLK1 (PDB: 3FC2). A) Volasertib bound to BRD4. B) Volasertib bound to PLK1. Volasertib is represented in green and magenta, with magenta representing moieties interacting with BRD4 non-kinase off target. Yellow dashes represent hydrogen bonding interactions, aqua dashes represent pi-pi stacking interactions. Red coloring in compound structure volasertib indicate moieties that participate in positive interactions with both BRD4 and PLK1.

Tofacitinib is a potent, non-selective inhibitor of the JAK kinases, with IC50 values for JAK1 and 3 less than 5 nM.[98] Tofacitinib became the first JAK inhibitor FDA approved for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis in 2012, and later approved to treat psoriatic arthritis and ulcerative colitis.[99,100] Through the use of ML, Faquetti and colleagues found an additional non-kinase off-target of tofacitinib, transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily M member 6 (TRPM6), a protein primarily responsible for magnesium transportation. Tofacitinib has a weak binding affinity for TRPM6, with a Kd of about 7 μM, which is clinically irrelevant.[100,101]

Baricitinib, another JAK inhibitor, was also evaluated by Faquetti and colleagues. Baricitinib is a potent inhibitor of JAK1 and JAK2, with IC50 values of 5.9 nM and 5.7 nM, respectively, and was FDA approved in 2018 for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis.[98] It was found that baricitinib inhibits phosphodiesterase 10A (PDE10A) at clinically irrelevant concentrations.[100,102] Despite the unsuccessful identification of toxicity causing off-targets, the use of machine learning techniques to identify potential undesirable off-targets will save time and resources in preclinical therapeutic development.

Covalent kinase inhibitors and non-kinase off targets

Covalent inhibitors form covalent bonds with cysteine residues or other reactive/nucleophilic residues such as lysine, serine, and aspartic acid.[103,104] The process of covalent bond formation is thought of as a two-step process; first, the inhibitor must bind in a reversible fashion to the protein target, followed by formation of a covalent bond by a nucleophilic residue on the protein attaching the electrophilic covalent warhead. Furthermore, medicinal chemists can alter the reactivity of the covalent warhead as needed, providing an axis of tunability to alter potency and selectivity. It is not surprising, however, that covalent kinase inhibitors are not totally selective within the kinome, and outside of it, as a portion of the human proteome possess cysteines.[105]

Interestingly, osimertinib, an FDA approved drug for the treatment of NSCLC, was found to target cathepsin cysteine proteases, including CTSC, CTSH, and CTSL1.[105] Osimertinib was approved in 2015 as an EGFR inhibitor. Osimertinib is a mutant-selective EGFR inhibitor with remarkable potency; the drug inhibits L858R with an IC50 of 12 nM and has an IC50 of 1 nM against the T790M mutation. It is important to note that IC50 values for irreversible inhibitors can be misleading due the inherent time dependence.[106] However, later studies showed that osimertinib was found to covalently modify cathepsins in both cellular and animal models.[105] Further computational studies suggest additional non-kinase off targets of osimertinib, including peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) and renin.[107] The molecular docking of osimertinib to various protein targets was performed utilizing a docking procedure that generated a covalent binding pose of osimertinib bound to EGFR that closely resembled the co-crystal structure of osimertinib bound to EGFR (PDB: 4ZAU).[107] PPARγ has been implicated in a number of diseases, including obesity, inflammation, and cancer.[108] Notably, activation of PPARγ is known to induce insulin sensitization, which could possibly contribute to the unusual side effect of hyperglycemia, which is exhibited in some patients who take osimertinib.[105,108,109] Renin is an enzyme that is a primary regulator of blood pressure.[110] The interactions between osimertinib and non-kinase off-targets PPARγ and renin have yet to be confirmed outside of covalent molecular docking, which can be prone to errors, hence, further experimental investigation is warranted.

Ibrutinib was first approved by the FDA in 2013 for the treatment of mantle cell lymphoma.[111,112] Ibrutinib was later indicated for the treatment of other B-cell malignancies, including chronic lymphocytic leukemia, marginal zone lymphoma (MZL), and Waldenström’s Macroglobulinemia (WM). Ibrutinib works by inhibiting BTK, which blocks the B-cell receptor pathway, which is aberrantly active in B-cell malignancies. Ibrutinib inhibits BTK by forming a covalent bond with the Cys481 residue.[112] Ibrutinib also reacts with numerous other cysteine-containing proteins; in a proteomic profiling study, researchers found ibrutinib inhibited peroxiredoxin-like 2A (FAM213A or PRXL2A) with an IC50 of 0.9 μM.[111] FAM213A is an uncharacterized protein which contains two conserved cysteines and has been linked to a poor prognosis in acute myeloid leukemia via regulation of oxidative stress and myelopoiesis.[112,113] At current dosing, the concentration of ibrutinib is unlikely to reach the FAM213A IC50 of 0.9 μM, deeming this off-target irrelevant.[114] However, ibrutinib shows antiproliferative effects against acute myeloid leukemia, and at higher doses, therapeutic efficacy could be tied to its inhibition of FAM213A. Ibrutinib was recently found to non-covalently bind to and inhibit NUDIX hydrolase NUDT5 with similar potencies as FAM213A (IC50 of 0.837 μM).[115] NUDIX proteins are relatively understudied and are poorly understood; they function as nucleotide-metabolizing enzymes and NUDT5 has been implicated as a possible synergistic target of PARP1 in breast cancer cells.[116] Due to the relatively weak potency, NUDIX inhibition is not a relevant off-target in current clinical settings, but has been used as a hit compound in the development of molecular probes for NUDT5 and NUDT14.[115]

Afatinib was FDA approved in 2013 for the treatment of metastatic NSCLC. Afatinib works by irreversibly inhibiting EGFR, human epidermal growth factor (HER) 2, and HER4, with IC50 values of 0.5, 14, and 1 nM, respectively.[117] Afatinib also exhibits non-covalent binding to brachyury (also known as T-box transcription factor T).[118] Brachyury is involved in the progression and/or initiation of numerous cancers, including lung, prostate, breast, colon, and hepatocellular cancers.[119] Additionally, this off-target activity has allowed for afatinib to be repurposed as a potential chordoma treatment, as brachyury is a key driver of this disease.[118] Chordoma, also called notochordal sarcoma, is a slowly growing cancer of spinal tissue and is often found near the sacral or clival regions.[118] Because brachyury is not present in normal tissues, it presents as an excellent anticancer target, and targeted therapeutics have high potential. The crystal structures of afatinib bound to kinase target EGFR (PDB: 4G5J) and non-kinase target brachyury (PDB: 6ZU8) have been solved and are shown in Figure 11. The essential amide moiety of afatinib binds to brachyury residue Val123 in a non-covalent fashion and is involved in the covalent bonding mechanism with Cys797 in EGFR. The 4-aminopyrimidine and phenyl chloride moieties engage in key interactions in EGFR while avoiding interactions in brachyury, with 4-aminopyrimidine binding to hinge residue Met793.

Figure 11.

Crystal Structure of afatinib bound to brachyury (PDB: 6ZU8) and EGFR (PDB: 4G5J). A) Afatinib bound to brachyury. B) Afatinib bound to EGFR, Cys797 is participating in covalent bonding. Afatinib is represented in green and magenta, with magenta representing moieties interacting with brachyury non-kinase off target. Yellow dashes represent hydrogen bonding interactions, magenta dashes represent salt bridges. Red coloring in compound structure of afatinib indicate moieties that participate in positive interactions with both brachyury and EGFR.

Kinase inhibitors and microtubule formation targets

Tivantinib is a non-competitive c-Met inhibitor that has yet to gain FDA approval.[120] Discovered by means of a phenotype-driven process, tivantinib showed promising anti-cancer activity and impressive selectivity, with a c-Met Km of 35.5 nM.[121] It was later discovered that the antiproliferative properties displayed by tivantinib were independent of the c-Met inhibition, and that interactions with microtubule formation contributed to its anticancer activity.[122,123]

During its development, rigosertib was identified and optimized to be a competitive inhibitor of PLK1.[124] Rigosertib does not bind to PLK1 in an irreversible fashion, despite the vinyl sulfone moiety that could act as a potential covalent warhead. Rigosertib has advanced to stage III clinical trials for the treatment of myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) but was not FDA approved due to poor efficacy.[125] Rigosertib was thought to interact with microtubule formation, however, this opinion was highly contentious due to its intricate involvement of PLK1 in the progression of mitosis.[126] The microtubule formation destabilization was ultimately confirmed using CRISPR technology.[127] There have been several other small molecule kinase inhibitors that have been discovered to interact microtubules; a comprehensive review on the topic has been recently published by Tanabe.[126] Crystal structures of both tivantinib and rigosertib bound to microtubules have been solved and are shown below (Figure 12). The indole and pyrrolidine-2,5-dione moieties in tivantinib engage in hydrogen bonding interactions with microtubule residues Ala315 and Asn256, respectively. The carboxylic acid moiety in rigosertib participates in a hydrogen bonding interaction with Ser178.

Figure 12.

Crystal structures of tivantinib (PDB: 5BC4) and rigosertib (PDB: 5OV7) bound to tubulin. A) Tivantinib bound to tubulin. B) Overall structure of tubulin represented in ribbon with binding site residues containing tivantinib represented by polar surface models. C) Rigosertib bound to tubulin. D) Overall structure of tubulin represented in ribbon with binding site residues containing rigosertib represented by polar surface models. Yellow dashes represent hydrogen bond interactions, orange dashes represent clashing interactions. Ribbon coloring is indicative of residue position. Polar surface area coloring determined by electrostatic potential; red shading is electropositive, blue shading is electronegative. Red coloring in compound structures of tivantinib and rigosertib indicate moieties that participate in positive interactions with tubulin.

Non-Kinase Inhibitors with Kinase Off-Targets

Levosimendan is a phosphodiesterase 3 (PDE3) inhibitor that was approved for clinical use in Europe in 2000 for the treatment for heart failure.[128] Through the use of in silico experimentation and in vitro validation, levosimendan was discovered to inhibit a number of kinases, including potent inhibition of RIO kinase 1 (RIOK1) and RIOK3 (85% inhibition when tested at 10 μM for both kinases), and moderate inhibition of FLT3, PIP5K1A, and c-Kit (76%, 78%, and 74% inhibition at 10 μM, respectively).[129] To date, many studies have examined the safety and efficacy of levosimendan. This extensive data has resulted in in the conclusion that levosimendan is relatively safe, with hypotension, extrasystoles, and headache/migraine being the primary risk factors.[128] When investigated in B-cell lymphoma cancer models, levosimendan boasts sub-micromolar potencies.[129]

Inhibitors of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase, or PARP, have also been revealed to have kinase activity as off-targets. A recent study utilizing an in silico experimentation to in vitro confirmation workflow identified rucaparib and niraparib as PARP inhibitors that have sub-micromolar potencies against kinases.[130] Rucaparib was FDA approved for the treatment with deleterious BRCA mutation associated ovarian cancer and is selective for PARP1 over other isoforms.[130,131] Rucaparib was found to inhibit CDK16, proto-oncogene serine/threonine kinase 3 (PIM3), and dual-specificity tyrosine phosphorylation-regulated kinase 1B (DYRK1B) kinases with IC50 values of 381 nM, 436 nM, and 747 nM, respectively.[130,132] These activities were observed in in vitro cell models, indicating the possibility of inducing adverse-effects in the blood and liver.

Niraparib was FDA approved in 2017 for the maintenance treatment of patients with recurrent ovarian, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal cancer.[133] Niraparib potently inhibits both PARP1 and PARP2 and was also found to potently inhibit DYRK1A and DYRK1B, with IC50 values of 297 nM and 254 nM, respectively.[130] The DYRK kinases are not implicated in ovarian cancer; however, DYRK1A is associated with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), a clinically relevant axis that needs to be further explored.[130]

Conclusion

It is apparent that many FDA approved kinase inhibitors and experimental compounds are active against other non-kinase targets that can contribute to the desired efficacy or result undesired toxicities. Among the several non-kinase targets that have been co-crystallized with the related kinase inhibitor, two distinct observations can be made. First, many of the moieties that participate in key interactions in the non-kinase proteins also bind to the most important parts of kinases: the hinge backbone and the catalytic regions. This is an unwelcome observation; most hinge and catalytic region binding moieties contain hydrogen bond donors and acceptors, thus, making it difficult to block undesired interactions to off-targets by simply avoiding certain functional groups. Secondly, most reported kinase inhibitors flexible, allowing several bioactive conformations to exist to a multitude of targets. For example, the average number of rotatable bonds for the kinase inhibitors highlighted in this review is 6.8. One strategy that could be used to improve selectivity for kinase over non-kinase target is to design compounds that are locked into the bioactive conformation for the desired kinase target.

Despite the possible implications of off-target interactions in non-kinase proteins, it is irrational to demand that all kinase inhibitors must undergo proteome-wide screening to identify off-targets during pre-clinical trials; it is neither time nor cost effective, and current safety panels can adequately identify major sources of toxicity. A recent study utilized a data-driven approach to identify/predict the non-kinase targets of over 150,000 kinase inhibitors.[134] Data from this study, especially datapoints that are experimentally validated, could be used as training set for machine learning to help predict non-kinase targets of potential kinase drugs, which could inform new polypharmacological strategies or mitigate unnecessary contribution to adverse effects.

Table 1.

Names and structures of kinase inhibitors and their non-kinase targets.

| Name | Structure | Kinase Target | Non-Kinase Off Target |

|---|---|---|---|

| imatinib |

|

ABL, PDGFR, c-Kit, DDR1 | NQO2 |

| nilotinib |

|

ABL, PDGFR, c-Kit, DDR1 | NQO2, SMO |

| dasatinib |

|

ABL, Src, LCK, c-Kit, BTK | TTR |

| sorafenib |

|

VEGFR, PDGFR, c-Kit, FLT3 | Xc, PDE60 |

| fostamatinib |

|

SYK | A3AR |

| gefitinib |

|

EGFR | DHODH, HSO17B1 |

| axitinib |

|

VEGFR1/2/3, PDGFR, c-Kit | SHPRH, MED23 |

| vemurafenib |

|

BRAF | FECH |

| alectinib |

|

ALK, RET | FECH |

| dabrafenib |

|

BRAF | hPXR |

| midostaurin |

|

FLT3, PDGFR, VEGFR2, c-Kit | AKR1C3 |

| dinaciclib |

|

CDKs | AKR1C3 |

| palbociclib |

|

CDK4/6 | STING |

| netarsudil |

|

ROCK1/2 | NET |

| entrectinib |

|

ALK, ROS1, NTRK1/2/3 | ABCB1 |

| fedratinib |

|

JAK2 | BRD4 |

| volasertib |

|

PLK1 | BRD4 |

| tofacitinib |

|

JAK1/2/3 | TRPM6 |

| baricitinib |

|

JAK1/2 | PDE10A |

Protein kinases are top targets for various diseases.

Kinase inhibitors rarely inhibit single kinase targets.

Some kinase inhibits also inhibit non-kinase targets.

Non-kinase target inhibition could account for drug efficacy and/or toxicity.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health (1R01CA267978).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests:

Herman Sintim reports financial support was provided by National Cancer Institute. If there are other authors, they declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- [1].Lim Kam Sian TCC, Chüeh AC, Daly RJ, Proteomics-based interrogation of the kinome and its implications for precision oncology, Proteomics 21 (2021). 10.1002/pmic.202000161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Bhullar KS, Lagarón NO, McGowan EM, Parmar I, Jha A, Hubbard BP, Rupasinghe HPV, Kinase-targeted cancer therapies: Progress, challenges and future directions, Mol Cancer 17 (2018). 10.1186/s12943-018-0804-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Klaeger S, Heinzlmeir S, Wilhelm M, Polzer H, Vick B, Koenig PA, Reinecke M, Ruprecht B, Petzoldt S, Meng C, Zecha J, Reiter K, Qiao H, Helm D, Koch H, Schoof M, Canevari G, Casale E, Re Depaolini S, Feuchtinger A, Wu Z, Schmidt T, Rueckert L, Becker W, Huenges J, Garz AK, Gohlke BO, Zolg DP, Kayser G, Vooder T, Preissner R, Hahne H, Tõnisson N, Kramer K, Götze K, Bassermann F, Schlegl J, Ehrlich HC, Aiche S, Walch A, Greif PA, Schneider S, Felder ER, Ruland J, Médard G, Jeremias I, Spiekermann K, Kuster B, The target landscape of clinical kinase drugs, Science (1979) 358 (2017). 10.1126/science.aan4368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Reinecke M, Brear P, Vornholz L, Berger BT, Seefried F, Wilhelm S, Samaras P, Gyenis L, Litchfield DW, Médard G, Müller S, Ruland J, Hyvönen M, Wilhelm M, Kuster B, Chemical proteomics reveals the target landscape of 1,000 kinase inhibitors, Nat Chem Biol (2023). 10.1038/s41589-023-01459-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Munoz L, Non-kinase targets of protein kinase inhibitors, Nat Rev Drug Discov 16 (2017) 424–440. 10.1038/nrd.2016.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Hantschel O, Unexpected off-targets and paradoxical pathway activation by kinase inhibitors, ACS Chem Biol 10 (2015) 234–245. 10.1021/cb500886n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Jeon JY, Sparreboom A, Baker SD, Kinase Inhibitors: The Reality Behind the Success, Clin Pharmacol Ther 102 (2017) 726–730. 10.1002/cpt.815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Lee SJ, Wang JYJ, Exploiting the promiscuity of imatinib, J Biol 8 (2009). 10.1186/jbiol134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Winger JA, Hantschel O, Superti-Furga G, Kuriyan J, The structure of the leukemia drug imatinib bound to human quinone reductase 2 (NQO2), BMC Struct Biol 9 (2009). 10.1186/1472-6807-9-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Rix U, Hantschel O, Dü Rnberger G, Rix LLR, Planyavsky M, V Fernbach N, Kaupe I, Bennett KL, Valent P, Colinge J, Kö Cher T, Superti-Furga G, Chemical proteomic profiles of the BCR-ABL inhibitors imatinib, nilotinib, and dasatinib reveal novel kinase and nonkinase targets, Blood 110 (2007) 4055–4063. 10.1182/blood-2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Miettinen TP, Björklund M, NQO2 is a reactive oxygen species generating off-target for acetaminophen, Mol Pharm 11 (2014) 4395–4404. 10.1021/mp5004866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Jabbour E, Cortes J, Kantarjian H, Core Evidence Nilotinib for the treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia: An evidence-based review, 2009. www.dovepress.com. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- [13].Weisberg E, Manley PW, Breitenstein W, Brüggen J, Cowan-Jacob SW, Ray A, Huntly B, Fabbro D, Fendrich G, Hall-Meyers E, Kung AL, Mestan J, Daley GQ, Callahan L, Catley L, Cavazza C, Mohammed A, Neuberg D, Wright RD, Gilliland DG, Griffin JD, Characterization of AMN107, a selective inhibitor of native and mutant Bcr-Abl, Cancer Cell 7 (2005) 129–141. 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Chahal KK, Li J, Kufareva I, Parle M, Durden DL, Wechsler-Reya RJ, Chen CC, Abagyan R, Nilotinib, an approved leukemia drug, inhibits smoothened signaling in Hedgehog-dependent medulloblastoma, PLoS One 14 (2019). 10.1371/journal.pone.0214901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Zhao C, Chen A, Jamieson CH, Fereshteh M, Abrahamsson A, Blum J, Kwon HY, Kim J, Chute JP, Rizzieri D, Munchhof M, VanArsdale T, Beachy PA, Reya T, Hedgehog signalling is essential for maintenance of cancer stem cells in myeloid leukaemia, Nature 458 (2009) 776–779. 10.1038/nature07737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Clement V, Sanchez P, de Tribolet N, Radovanovic I, Ruiz i Altaba A, HEDGEHOG-GLI1 Signaling Regulates Human Glioma Growth, Cancer Stem Cell Self-Renewal, and Tumorigenicity, Current Biology 17 (2007) 165–172. 10.1016/j.cub.2006.11.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Caro I, Low JA, The role of the hedgehog signaling pathway in the development of basal cell carcinoma and opportunities for treatment, Clinical Cancer Research 16 (2010) 3335–3339. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Trent J, Molimard M, Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of nilotinib in gastrointestinal stromal tumors, Semin Oncol 38 (2011). 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2011.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Das J, Chen P, Norris D, Padmanabha R, Lin J, Moquin RV, Shen Z, Cook LS, Doweyko AM, Pitt S, Pang S, Shen DR, Fang Q, De Fex HF, McIntyre KW, Shuster DJ, Gillooly KM, Behnia K, Schieven GL, Wityak J, Barrish JC, 2-Aminothiazole as a novel kinase inhibitor template. Structure-activity relationship studies toward the discovery of N-(2-chloro-6-methylphenyl)-2-[[6-[4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazinyl]-2-methyl-4-pyrimidinyl]amino]-1, 3-thiazole-5-carboxamide (Dasatinib, BMS-354825) as a potent pan-Src kinase inhibitor, J Med Chem 49 (2006) 6819–6832. 10.1021/jm060727j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].O’hare T, Walters DK, Stoffregen EP, Jia T, Manley PW, Mestan J, Cowan-Jacob SW, Lee FY, Heinrich MC, Deininger MWN, Druker BJ, In vitro Activity of Bcr-Abl Inhibitors AMN107 and BMS-354825 against Clinically Relevant Imatinib-Resistant Abl Kinase Domain Mutants, Cancer Res 65 (2005) 4500–4505. http://cancerres.aacrjournals.org/. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Yokoyama T, Kashihara M, Mizuguchi M, Repositioning of the Anthelmintic Drugs Bithionol and Triclabendazole as Transthyretin Amyloidogenesis Inhibitors, J Med Chem 64 (2021) 14344–14357. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.1c00823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Schmidt S, Gonzalez D, Derendorf H, Significance of protein binding in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics, J Pharm Sci 99 (2010) 1107–1122. 10.1002/jps.21916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Wilhelm S, Carter C, Lynch M, Lowinger T, Dumas J, Smith RA, Schwartz B, Simantov R, Kelley S, Discovery and development of sorafenib: A multikinase inhibitor for treating cancer, Nat Rev Drug Discov 5 (2006) 835–844. 10.1038/nrd2130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, Hilgard P, Gane E, Blanc J-F, de Oliveira AC, Santoro A, Raoul J-L, Forner A, Schwartz M, Porta C, Zeuzem S, Bolondi L, Greten TF, Galle PR, Seitz J-F, Borbath I, Häussinger D, Giannaris T, Shan M, Moscovici M, Voliotis D, Bruix J, Sorafenib in Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma, N. Engl. J. Med 359 (2008) 378–390. www.nejm.org. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Dixon SJ, Patel D, Welsch M, Skouta R, Lee E, Hayano M, Thomas AG, Gleason C, Tatonetti N, Slusher BS, Stockwell BR, Pharmacological inhibition of cystine-glutamate exchange induces endoplasmic reticulum stress and ferroptosis, Elife 2014 (2014). 10.7554/eLife.02523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Werth EG, Rajbhandari P, Stockwell BR, Brown LM, Time Course of Changes in Sorafenib-Treated Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells Suggests Involvement of Phospho-Regulated Signaling in Ferroptosis Induction, Proteomics 20 (2020). 10.1002/pmic.202000006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Zheng J, Sato M, Mishima E, Sato H, Proneth B, Conrad M, Sorafenib fails to trigger ferroptosis across a wide range of cancer cell lines, Cell Death Dis 12 (2021). 10.1038/s41419-021-03998-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Li Y, Meng Q, Wang P, Liu X, Fu Q, Xie Y, Zhou Y, Qi X, Huang N, Identification of PDE6D as a potential target of sorafenib via PROTAC technology, BioRxiv (2020) 2020.05.06.079947. 10.1101/2020.05.06.079947. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Dietrich P, Hellerbrand C, Bosserhoff A, The delta subunit of rod-specific photoreceptor cgmp phosphodiesterase (Pde6d) contributes to hepatocellular carcinoma progression, Cancers (Basel) 11 (2019). 10.3390/cancers11030398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Braselmann S, Taylor V, Zhao H, Wang S, Sylvain C, Baluom M, Qu K, Herlaar E, Lau A, Young C, Wong BR, Lovell S, Sun T, Park G, Argade A, Jurcevic S, Pine P, Singh R, Grossbard EB, Payan DG, Masuda ES, R406, an orally available spleen tyrosine kinase inhibitor blocks Fc receptor signaling and reduces immune complex-mediated inflammation, Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics 319 (2006) 998–1008. 10.1124/jpet.106.109058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Rolf MG, Curwen JO, Veldman-Jones M, Eberlein C, Wang J, Harmer A, Hellawell CJ, Braddock M, In vitro pharmacological profiling of R406 identifies molecular targets underlying the clinical effects of fostamatinib, Pharmacol Res Perspect 3 (2015). 10.1002/prp2.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Noji T, Karasawa A, Kusaka H, Adenosine uptake inhibitors, Eur J Pharmacol 495 (2004) 1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Fishman P, Drugs Targeting the A3 Adenosine Receptor: Human Clinical Study Data, Molecules 27 (2022) 3680–3692. 10.3390/molecules27123680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Wakeling AE, Guy SP, Woodburn JR, Ashton SE, Curry BJ, Barker AJ, Gibson KH, ZD1839 (Iressa) An Orally Active Inhibitor of Epidermal Growth Factor Signaling with Potential for Cancer Therapy, Cancer Res 62 (2002) 5749–5754. http://cancerres.aacrjournals.org/content/62/20/5749.full.html#related-urls. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Muhsin M, Graham J, Kirkpatrick P, Gefitinib, Nat Rev Drug Discov 2 (2003) 515–516. 10.1038/nrd1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Verma N, Rai AK, Kaushik V, Brünnert D, Chahar KR, Pandey J, Goyal P, Identification of gefitinib off-targets using a structure-based systems biology approach; Their validation with reverse docking and retrospective data mining, Sci Rep 6 (2016). 10.1038/srep33949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Roubille C, Haraoui B, Interstitial lung diseases induced or exacerbated by DMARDS and biologic agents in rheumatoid arthritis: A systematic literature review, Semin Arthritis Rheum 43 (2014) 613–626. 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2013.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Hu-Lowe DD, Zou HY, Grazzini ML, Hallin ME, Wickman GR, Amundson K, Chen JH, Rewolinski DA, Yamazaki S, Wu EY, McTigue MA, Murray BW, Kania RS, O’Connor P, Shalinsky DR, Bender SL, Nonclinical antiangiogenesis and antitumor activities of axitinib (AG-013736), an oral, potent, and selective inhibitor of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor tyrosine kinases 1, 2, 3, Clinical Cancer Research 14 (2008) 7272–7283. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].McTigue M, Murray BW, Chen JH, Deng YL, Solowiej J, Kania RS, Molecular conformations, interactions, and properties associated with drug efficiency and clinical performance among VEGFR TK inhibitors, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109 (2012) 18281–18289. 10.1073/pnas.1207759109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Qu Y, Gharbi N, Yuan X, Olsen JR, Blicher P, Dalhus B, Brokstad KA, Lin B, Øyan AM, Zhang W, Kalland KH, Ke X, Axitinib blocks Wnt/β-catenin signaling and directs asymmetric cell division in cancer, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113 (2016) 9339–9344. 10.1073/pnas.1604520113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Chatterjee N, Walker GC, Mechanisms of DNA damage, repair, and mutagenesis, Environ Mol Mutagen 58 (2017) 235–263. 10.1002/em.22087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Jung YS, Il Park J, Wnt signaling in cancer: therapeutic targeting of Wnt signaling beyond β-catenin and the destruction complex, Exp Mol Med 52 (2020) 183–191. 10.1038/s12276-020-0380-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Zhang Y, Wang X, Targeting the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in cancer, J Hematol Oncol 13 (2020). 10.1186/s13045-020-00990-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Streubel G, Bracken AP, MED 23: a new Mediator of H2B monoubiquitylation, EMBO J 34 (2015) 2863–2864. 10.15252/embj.201592996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Qu Y, Gharbi N, Yuan X, Olsen JR, Blicher P, Dalhus B, Brokstad KA, Lin B, Øyan AM, Zhang W, Kalland KH, Ke X, Axitinib blocks Wnt/β-catenin signaling and directs asymmetric cell division in cancer, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113 (2016) 9339–9344. 10.1073/pnas.1604520113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Chen Y, Tortorici MA, Garrett M, Hee B, Klamerus KJ, Pithavala YK, Clinical pharmacology of axitinib, Clin Pharmacokinet 52 (2013) 713–725. 10.1007/s40262-013-0068-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Klaeger S, Gohlke B, Perrin J, Gupta V, Heinzlmeir S, Helm D, Qiao H, Bergamini G, Handa H, Savitski MM, Bantscheff M, Médard G, Preissner R, Kuster B, Chemical Proteomics Reveals Ferrochelatase as a Common Off-target of Kinase Inhibitors, ACS Chem Biol 11 (2016) 1245–1254. 10.1021/acschembio.5b01063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Bollag G, Tsai J, Zhang J, Zhang C, Ibrahim P, Nolop K, Hirth P, Vemurafenib: The first drug approved for BRAF-mutant cancer, Nat Rev Drug Discov 11 (2012) 873–886. 10.1038/nrd3847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Pirker R, Filipits M, Alectinib in RET-rearranged non-small cell lung cancer-Another progress in precision medicine?, Transl Lung Cancer Res 4 (2015) 797–800. 10.3978/j.issn.2218-6751.2015.03.08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Kinoshita K, Asoh K, Furuichi N, Ito T, Kawada H, Hara S, Ohwada J, Miyagi T, Kobayashi T, Takanashi K, Tsukaguchi T, Sakamoto H, Tsukuda T, Oikawa N, Design and synthesis of a highly selective, orally active and potent anaplastic lymphoma kinase inhibitor (CH5424802), Bioorg Med Chem 20 (2012) 1271–1280. 10.1016/j.bmc.2011.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Kodama T, Tsukaguchi T, Yoshida M, Kondoh O, Sakamoto H, Selective ALK inhibitor alectinib with potent antitumor activity in models of crizotinib resistance, Cancer Lett 351 (2014) 215–221. 10.1016/j.canlet.2014.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Savitski MM, † Friedrich, Reinhard BM, † Franken Holger, Werner T, Savitski MF, Eberhard D, Molina DM, Jafari R, Dovega RB, Klaeger S, Kuster B, Nordlund P, Bantscheff M, Drewes G, Tracking cancer drugs in living cells by thermal profiling of the proteome, Science (1979) 346 (2014) 1255784. https://www.science.org. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Sishtla K, Lambert-Cheatham N, Lee B, Han DH, Park J, Sardar Pasha SPB, Lee S, Kwon S, Muniyandi A, Park B, Odell N, Waller S, Park IY, Lee SJ, Seo SY, Corson TW, Small-molecule inhibitors of ferrochelatase are antiangiogenic agents, Cell Chem Biol 29 (2022) 1010–1023.e14. 10.1016/j.chembiol.2022.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Klaeger S, Gohlke B, Perrin J, Gupta V, Heinzlmeir S, Helm D, Qiao H, Bergamini G, Handa H, Savitski MM, Bantscheff M, Médard G, Preissner R, Kuster B, Chemical Proteomics Reveals Ferrochelatase as a Common Off-target of Kinase Inhibitors, ACS Chem Biol 11 (2016) 1245–1254. 10.1021/acschembio.5b01063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Rheault TR, Stellwagen JC, Adjabeng GM, Hornberger KR, Petrov KG, Waterson AG, Dickerson SH, Mook RA, Laquerre SG, King AJ, Rossanese OW, Arnone MR, Smitheman KN, Kane-Carson LS, Han C, Moorthy GS, Moss KG, Uehling DE, Discovery of dabrafenib: A selective inhibitor of Raf Kinases with antitumor activity against B-Raf-driven tumors, ACS Med Chem Lett 4 (2013) 358–362. 10.1021/ml4000063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].King AJ, Arnone MR, Bleam MR, Moss KG, Yang J, Fedorowicz KE, Smitheman KN, Erhardt JA, Hughes-Earle A, Kane-Carson LS, Sinnamon RH, Qi H, Rheault TR, Uehling DE, Laquerre SG, Dabrafenib; Preclinical Characterization, Increased Efficacy when Combined with Trametinib, while BRAF/MEK Tool Combination Reduced Skin Lesions, PLoS One 8 (2013). 10.1371/journal.pone.0067583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Creusot N, Gassiot M, Alaterre E, Chiavarina B, Grimaldi M, Boulahtouf A, Toporova L, Gerbal-Chaloin S, Daujat-Chavanieu M, Matheux A, Rahmani R, Gongora C, Evrard A, Pourquier P, Balaguer P, The Anti-Cancer Drug Dabrafenib Is a Potent Activator of the Human Pregnane X Receptor, Cells 9 (2020). 10.3390/cells9071641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Chen Y, Tang Y, Chen S, Nie D, Regulation of drug resistance by human pregnane X receptor in breast cancer, Cancer Biol Ther 8 (2009) 1265–1272. 10.4161/cbt.8.13.8696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Harmsen S, Meijerman I, Beijnen JH, Schellens JHM, Nuclear receptor mediated induction of cytochrome P450 3A4 by anticancer drugs: A key role for the pregnane X receptor, Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 64 (2009) 35–43. 10.1007/s00280-008-0842-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Liu T, Beck JP, Hao J, A concise review on hPXR ligand-recognizing residues and structure-based strategies to alleviate hPXR transactivation risk, RSC Med Chem 13 (2022) 129–137. 10.1039/d1md00348h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Morell A, Novotná E, Milan J, Danielisová P, Büküm N, Wsól V, Selective inhibition of aldo-keto reductase 1C3: a novel mechanism involved in midostaurin and daunorubicin synergism, Arch Toxicol 95 (2021) 67–78. 10.1007/s00204-020-02884-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Matsunaga T, Yamaguchi A, Morikawa Y, Kezuka C, Takazawa H, Endo S, El-Kabbani O, Tajima K, Ikari A, Hara A, Induction of aldo-keto reductases (AKR1C1 and AKR1C3) abolishes the efficacy of daunorubicin chemotherapy for leukemic U937 cells, Anticancer Drugs 25 (2014) 868–877. 10.1097/CAD.0000000000000112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Wang Y, Yin OQP, Graf P, Kisicki JC, Schran H, Green, Kane, Dose- and time-dependent pharmacokinetics of midostaurin in patients with diabetes mellitus, J Clin Pharmacol 48 (2008) 763–775. 10.1177/0091270008318006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Ghia P, Scarfò L, Perez S, Pathiraja K, Derosier M, Small K, Sisk CMC, Patton N, Efficacy and safety of dinaciclib vs ofatumumab in patients with relapsed/refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia, Blood 129 (2017) 1876–1878. 10.1182/blood-2016-10-748210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Paruch K, Dwyer MP, Alvarez C, Brown C, Chan TY, Doll RJ, Keertikar K, Knutson C, McKittrick B, Rivera J, Rossman R, Tucker G, Fischmann T, Hruza A, Madison V, Nomeir AA, Wang Y, Kirschmeier P, Lees E, Parry D, Sgambellone N, Seghezzi W, Schultz L, Shanahan F, Wiswell D, Xu X, Zhou Q, James RA, Paradkar VM, Park H, Rokosz LR, Stauffer TM, Guzi TJ, Discovery of dinaciclib (SCH 727965): A potent and selective inhibitor of cyclin-dependent kinases, ACS Med Chem Lett 1 (2010) 204–208. 10.1021/ml100051d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Kumar SK, Laplant B, Chng WJ, Zonder J, Callander N, Fonseca R, Fruth B, Roy V, Erlichman C, Stewart AK, Dinaciclib, a novel CDK inhibitor, demonstrates encouraging single-agent activity in patients with relapsed multiple myeloma Key Points, (2015). 10.1182/blood-2014-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Novotná E, Büküm N, Hofman J, Flaxová M, Kouklíková E, Louvarová D, Wsól V, Aldo-keto reductase 1C3 (AKR1C3): a missing piece of the puzzle in the dinaciclib interaction profile, Arch Toxicol 92 (2018) 2845–2857. 10.1007/s00204-018-2258-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Beaver JA, Amiri-Kordestani L, Charlab R, Chen W, Palmby T, Tilley A, Zirkelbach JF, Yu J, Liu Q, Zhao L, Crich J, Chen XH, Hughes M, Bloomquist E, Tang S, Sridhara R, Kluetz PG, Kim G, Ibrahim A, Pazdur R, Cortazar P, FDA approval: Palbociclib for the treatment of postmenopausal patients with estrogen receptor-positive, HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer, Clinical Cancer Research 21 (2015) 4760–4766. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Fry DW, Harvey PJ, Keller PR, Elliott WL, Meade M, Trachet E, Albassam M, Zheng X, Leopold WR, Pryer NK, Toogood PL, Specific inhibition of cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 by PD 0332991 and associated antitumor activity in human tumor xenografts, 2004. http://aacrjournals.org/mct/article-pdf/3/11/1427/3261842/1427-1437.pdf. [PubMed]

- [70].Gao J, Zheng M, Wu X, Zhang H, Su H, Dang Y, Ma M, Wang F, Xu J, Chen L, Liu T, Chen J, Zhang F, Yang L, Xu Q, Hu X, Wang H, Fei Y, Chen C, Liu H, CDK inhibitor Palbociclib targets STING to alleviate autoinflammation, EMBO Rep 23 (2022). 10.15252/embr.202153932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Chandra D, Quispe-Tintaya W, Jahangir A, Asafu-Adjei D, Ramos I, Sintim HO, Zhou J, Hayakawa Y, Karaolis DKR, Gravekamp C, STING Ligand c-di-GMP Improves Cancer Vaccination against Metastatic Breast Cancer, Cancer Immunol Res 2 (2014) 901–910. 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-13-0123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Moshirfar M, Parker L, Birdsong OC, Ronquillo YC, Hofstedt D, Shah TJ, Gomez AT, Hoopes PC, Moran JA, Use of Rho kinase Inhibitors in Ophthalmology: A Review of the Literature, Med. Hypothesis Discov. Innov. Ophthalmol 7 (2018) 101–111. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Lin CW, Sherman B, Moore LA, Laethem CL, Lu DW, Pattabiraman PP, Rao PV, Delong MA, Kopczynski CC, Discovery and preclinical development of netarsudil, a novel ocular hypotensive agent for the treatment of glaucoma, Journal of Ocular Pharmacology and Therapeutics 34 (2018) 40–51. 10.1089/jop.2017.0023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Schroeder C, Jordan J, Norepinephrine transporter function and human cardiovascular disease, Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 303 (2012) 1273–1282. 10.1152/ajpheart.00492.2012.-Approxi. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Facchinetti F, Friboulet L, Profile of entrectinib and its potential in the treatment of ROS1-positive NSCLC: Evidence to date, Lung Cancer: Targets and Therapy 10 (2019) 87–94. 10.2147/LCTT.S190786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Liu D, Offin M, Harnicar S, Li BT, Drilon A, Entrectinib: An orally available, selective tyrosine kinase inhibitor for the treatment of NTRK, ROS1, and ALK fusion-positive solid tumors, Ther Clin Risk Manag 14 (2018) 1247–1252. 10.2147/TCRM.S147381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Vaishnavi A, Capelletti M, Le AT, Kako S, Butaney M, Ercan D, Mahale S, Davies KD, Aisner DL, Pilling AB, Berge EM, Kim J, Sasaki H, Il Park S, Kryukov G, Garraway LA, Hammerman PS, Haas J, Andrews SW, Lipson D, Stephens PJ, Miller VA, Varella-Garcia M, Jänne PA, Doebele RC, Oncogenic and drug-sensitive NTRK1 rearrangements in lung cancer, Nat Med 19 (2013) 1469–1472. 10.1038/nm.3352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Pacenta HL, Macy ME, Entrectinib and other ALK/TRK inhibitors for the treatment of neuroblastoma, Drug Des Devel Ther 12 (2018) 3549–3561. 10.2147/DDDT.S147384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Ardini E, Menichincheri M, Banfi P, Bosotti R, De Ponti C, Pulci R, Ballinari D, Ciomei M, Texido G, Degrassi A, Avanzi N, Amboldi N, Saccardo MB, Casero D, Orsini P, Bandiera T, Mologni L, Anderson D, Wei G, Harris J, Vernier JM, Li G, Felder E, Donati D, Isacchi A, Pesenti E, Magnaghi P, Galvani A, Entrectinib, a Pan-TRK, ROS1, and ALK inhibitor with activity in multiple molecularly defined cancer indications, Mol Cancer Ther 15 (2016) 628–639. 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-15-0758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Vagiannis D, Yu Z, Novotna E, Morell A, Hofman J, Entrectinib reverses cytostatic resistance through the inhibition of ABCB1 efflux transporter, but not the CYP3A4 drug-metabolizing enzyme, Biochem Pharmacol 178 (2020). 10.1016/j.bcp.2020.114061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Krchniakova M, Skoda J, Neradil J, Chlapek P, Veselska R, Repurposing tyrosine kinase inhibitors to overcome multidrug resistance in cancer: A focus on transporters and lysosomal sequestration, Int J Mol Sci 21 (2020). 10.3390/ijms21093157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Mullally A, Hood J, Harrison C, Mesa R, Fedratinib in myelofibrosis, Blood Adv 4 (2020) 1792–1800. 10.1182/bloodadvances.2019000954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]