Abstract

Magang geese are typical short-day breeders whose reproductive behaviors are significantly influenced by photoperiod. Exposure to a long-day photoperiod results in testicular regression and spermatogenesis arrest in Magang geese. To investigate the epigenetic influence of DNA methylation on the seasonal testicular regression in Magang geese, we conducted whole-genome bisulfite sequencing and transcriptome sequencing of testes across 3 reproductive phases during a long-day photoperiod. A total of 250,326 differentially methylated regions (DMR) were identified among the 3 comparison groups, with a significant number showing hypermethylation, especially in intronic regions of the genome. Integrating bisulfite sequencing with transcriptome sequencing data revealed that DMR-associated genes tend to be differentially expressed in the testes, highlighting a potential regulatory role for DNA methylation in gene expression. Furthermore, there was a significant negative correlation between changes in the methylation of CG DMRs and changes in the expression of their associated genes in the testes. A total of 3,359 DMR-associated differentially expressed genes (DEG) were identified; functional enrichment analyses revealed that motor proteins, MAPK signaling pathway, ECM-receptor interaction, phagosome, TGF-beta signaling pathway, and calcium signaling might contribute to the testicular regression process. GSEA revealed that the significantly enriched activated hallmark gene set was associated with apoptosis and estrogen response during testicular regression, while the repressed hallmark gene set was involved in spermatogenesis. Our study also revealed that methylation changes significantly impacted the expression level of vitamin A metabolism-related genes during testicular degeneration, with hypermethylation of STRA6 and increased calmodulin levels indicating vitamin A efflux during the testicular regression. These findings were corroborated by pyrosequencing and real-time qPCR, which revealed that the vitamin A metabolic pathway plays a pivotal role in testicular degeneration under long-day conditions. Additionally, metabolomics analysis revealed an insufficiency of vitamin A and an abnormally high level of oxysterols accumulated in the testes during testicular regression. In conclusion, our study demonstrated that testicular degeneration in Magang geese induced by a long-day photoperiod is linked to vitamin A homeostasis disruption, which manifests as the hypermethylation status of STRA6, vitamin A efflux, and a high level of oxysterol accumulation. These findings offer new insights into the effects of DNA methylation on the seasonal testicular regression that occurs during long-day photoperiods in Magang geese.

Key words: DNA methylation, seasonal reproduction, photoperiod, testicular degeneration, Magang geese

INTRODUCTION

Domestic geese are seasonal breeders with the lowest reproductive capacity among all poultry species, as their reproduction timing depends on day length. The Magang Geese, a topical short-day breeder, initiates its breeding season from late summer through to the following spring (Shi et al., 2007a; Shi et al., 2008). Similar to other seasonal breeders, the reproductive activation of Magang geese is influenced by seasonal variations in daily photoperiods. Increasing evidence suggests that exposure to a long-day photoperiod inhibits reproductive activity, resulting in testicular regression and spermatogenesis arrest in males (Huang et al., 2008; Zhu et al., 2017; Pan et al., 2022).

Seasonal reproduction is intricately controlled by photoperiod and complex endocrine signals orchestrated by the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis. In birds, light signals predominantly regulate the secretion of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) in the Pars tuberalis (PT) through the activation of deep brain photoreceptors (DBP) in the hypothalamus (Nakao et al., 2008; Kuenzel et al., 2015). TSH retrogradely acts upon tanycyte in the Mediobasal hypothalamus, facilitating the conversion of thyroxine (T4) to triiodothyronine (T3), which plays an essential role in the seasonal activation of the HPG axis by regulating the biosynthesis and secretion of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH). This cascade influences sex hormone production and gametogenesis via the secretion of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH) by the pituitary gland; LH acts on Leydig cells to regulate testosterone production, thus regulating the seasonal activities of the reproductive axis in animals (Kuenzel, 2014; Yusuke Nakane, 2019).

In seasonally breeding birds, day length triggers morphological alterations in their reproductive systems, particularly in the testes (Follett and Maung, 1978). The effect of photoperiod on the reproductive system primarily manifests as depleted testicular function, leading to reduced testosterone production, spermatogenesis arrest, and changes in sperm quality and quantity. Testosterone is crucial for controlling male reproductive activities, as it influences a wide range of physiological, morphological, and behavioral characteristics associated with breeding that depend on its presence. In seasonal breeders, male plasma T levels typically exhibit a pronounced peak during the breeding season, play a pivotal role in the development of male genitalia, support sperm production, and regulate mating behavior (Shi et al., 2007a). These alterations culminate in a decline in fertility and inhibited mating behavior (Jiménez, et al., 2015; Zhu et al., 2017; Beltrán-Frutos, et al., 2022).

A long-day photoperiod caused a profound change in the architecture and function of the testes of Magang geese. Although transcriptome responses to photoperiod effects on the testis have been extensively studied in avians (Sun et al., 2020; Sharma, et al., 2021), relatively little is known about the epigenetic impact of testicular regression during long-day photoperiods. Current knowledge is primarily based on genetic analyses of candidate genes associated with endocrine regulation of the HPG axis (Leska, et al., 2012; Gumułka, et al., 2023). Epigenetic changes alter the reproductive pathways linked to male fertility in Mustela nigripes (Tennenbaum et al., 2024). In Siberian hamsters, DNA methyltransferase 3a (Dnmt3a) exhibits marked photoperiodic plasticity, with short-day photoperiods notably increasing both global DNA methylation and Dnmt3a expression in the testes (Lynch et al., 2016). Recent studies have demonstrated that m6A modification plays a regulatory role in seasonal testicular activity. This suggests that m6A modification in testicular tissue may contribute to the recovery of testicular function stimulated by photoperiods (Rader et al., 2023). Growing evidence shows that DNA methylation appears to play a potential role in testicular regression induced by long-day photoperiods.

DNA methylation is a key component of epigenetic regulation; recent studies have highlighted that DNA methylation has a substantial impact on the regulation of the seasonal reproductive behavior and phenotypic plasticity of animals (Stevenson and Prendergast, 2013; Alvarado et al., 2014; Viitaniemi, et al., 2019; He et al., 2023). The epigenetics mechanisms underlying seasonal changes in testicular function in geese have not been fully elucidated. To elucidate the epigenetic effect on testicular function in Magang geese, we compared the epigenetic and transcriptional profiles of the testes. Additionally, to investigate the relationship between epigenetic modifications and gene expression changes in response to long-day photoperiods, we identified the essential genes and pathways that potentially contribute to testicular regression induced by long-day photoperiods via differential expression analyses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and Artificial Photoperiodism

The animal trials were conducted from September 2019 to November 2019 at a geese farm located in Qingyuan City (113° 06′ E, 23° 68′ N), Guangdong Province. A population of 3-year-old Magang goose (n = 540, male: female =1:5) was used in the experiment. Initially, the geese were exposed to a natural photoperiod, in which day length was approximating [(12 light (L):12 dark (D)]. As the geese entered their breeding seasons and displayed strong reproductive activity (RA stage), we collected RA samples on 27 September 2019 and initiated an artificial photoperiod program to suppress the breeding activity of Magang geese. Subsequently, the geese were transferred to artificial long-day conditions (18 L: 6 D) for 17 d, leading to the decline of testicular reproductive activity in the population. At this stage, the laying rate in female geese decreased to 17% compared to the laying period, and samples were collected (RD stage). Two weeks later, the geese population was induced into the reproductive inactivity stage, and samples were collected accordingly (RI stage). In the present study, 3 independent biological replicates were performed for each group (RA, RD, and RI). The geese were euthanized by inhalation of carbon dioxide and cervical dislocation, which was performed by a laboratory technician who has extensive experience in the application of these techniques. Testis samples were collected. The testis tissue was immediately crosscut and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) solution for 12 h at 4°C. For RNA extraction, testicular samples were dissected into small pieces, frozen in liquid nitrogen immediately, and then stored at -80°C.

Testicular Histology and Measurement of Hormone Concentrations

Geese testicular samples were then dehydrated in an ethanol series and embedded in paraffin in accordance with standard procedures. Serial sections (5 μM) were mounted on slides coated with poly-L-lysine (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO, USA). Some sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE) for histological observation. The slides were examined using a photomicroscope (BX51, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). We randomly selected five convoluted seminiferous tubules in each section at each stage and calculated their cross-section areas using Image Pro Plus 6.0 software. Serum concentrations of testosterone (T), luteinizing hormone (LH), and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) were measured using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) according to the instructions provided with the kits. The detection range for T was 0.31 to 20 ng/mL with a coefficient of variation (CV) of less than 10%; for LH, 0.5 to 100 mIU/mL with a CV of less than 8%; and for FSH, 0.9 to 210 mIU/mL with a CV of less than 8%.

Bisulfite Sequencing and Bioinformatics Analyses

Testicular samples from the 3 groups (RA, RD, and RI), each with 3 biological replicates (n = 3), were collected for transcriptome sequencing and whole-genome bisulfite sequencing (BS-seq). For BS-sequencing, genomic DNA was extracted from tissues using the QIAamp DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (69504, QIAGEN, Germany). A total of 500 ng of genomic DNA was subjected to bisulfite treatment using the Zymo EZ DNA Methylation-Gold Kit (Zymo Research, CA, USA). Subsequently, the bisulfite-treated DNA was purified to prepare whole-genome bisulfite sequencing libraries with an EpiGnome Kit (Epicenter, Madison, WI, USA). All libraries were sequenced using the BGI MGISEQ-2000 platform with 100 bp paired-end reads (BGI, Shenzhen, Guangdong, China). Raw data quality control involved trimming low-quality bases and removing adapters with Trimmomatic v.0.36 (Bolger et al., 2014). The reference genome index was constructed using HISAT2 v2.1.0 software (Kim et al., 2019) from the chromosome-level genome of the Lion-head goose (Anser cygnoides), which was assembled by Zhongkai University of Agriculture and Engineering (data unpublished). Clean reads were aligned to the reference genome with default parameters, and unique mapping reads were utilized for methylation analyses.

The bisulfite conversion efficiency was assessed by calculating the proportion of methylated cytosines (false discovery rate, FDR < 0.05), with those covered by at least five sequencing reads considered methylation sites for subsequent analyses. DNA methylation levels were determined by calculating the proportion of methylated cytosines out of the total cytosines for each sample across all 3 sequence contexts. The consistency between biological replicates was verified through sliding window analysis (window size =100 kb and step size =50 kb). Differentially methylated regions (DMRs) were identified using MethylKit (Akalin et al., 2012) with a 100 bp window size and a 50 bp step size, applying the Benjamini–Hochberg method for multiple test correction (Benjamini and Hochberg, 1995). Pearson's correlation coefficient between methylation levels in pairs of biological replicates was calculated within 3 groups.

RNA-seq and Differential Gene Expression Analysis

Total RNA was extracted and subjected to RNA sequencing using the BGISeq-500 platform, which generated 50 bp single-end reads. Clean reads filtered by Fastp (Chen et al., 2018a) were mapped to the goose genome using HISAT2 v2.1.0 software (Kim et al., 2019) with default parameters. Differentially expressed genes (DEG) were identified using DEseq2(v.1.26.0) (Love et al., 2014), with a threshold of FDR <=0.05 and a fold change >=2. Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed at each stage using the regularized log2 transform of normalized counts for all genes, as generated by DESeq2 (v.1.26.0) (Love et al., 2014). Pearson correlation for gene expression (log2 of the normalized counts) between biological replicates was calculated using R v.3.6.2 (https://www.R-project.org). The DMR-associated genes were subjected to gene ontology (GO) enrichment analysis using Metascape (https://Metascape.org/). KEGG pathway annotation was performed according to the KEGG database (https://www.genome.jp/kegg/) (Kanehisa and Goto, 2000; Kanehisa, 2019; Kanehisa et al., 2023), and KEGG enrichment analysis was carried out using KOBAS (Bu et al., 2021), with p < 0.05 set as the threshold for significant enrichment. The Primers used for qPCR are listed in Table S1.

Detection of vitamin A metabolite, steroid metabolite, and calcium/calmodulin level in the testis

The concentrations of vitamin A metabolites in the testicular tissues of geese at the 3 stages were measured using the AB SCIEX QTRAP LC‒MS/MS detection platform. Testicular samples were homogenized and processed for liquid chromatograph-mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) analysis within 24 h. Six vitamin A metabolites (isotretinoin, retinoic acid, all-trans-retinol, all-trans-retinal, and retinyl acetate) and 43 steroids (Table S2) were quantified using a Waters ACQUITY UPLC system (Waters, Framingham, MA). Chromatography was conducted on an ACQUITY UPLC BEH C18 column (2.1 × 100 mm, Waters) with a 5 μL sample injection volume by an autosampler, and the column temperature was maintained at 40°C. Mass spectrometry analysis was performed under positive ion mode conditions with the following parameters: ion source temperature at 500°C; ion spray voltage at 5,000 V; curtain gas (nitrogen) pressure, 30 psi; and both atomizing and auxiliary gas pressure, 60 psi. The multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) scan method was utilized for mass spectrometry. Calmodulin (CaM) levels were detected in a testicular homogenate using a chicken CaM ELISA kit (SBJ-C108, SenBeiJia Biological Technology Co., Ltd. Nanjing, China), and the calcium concentration in the serum samples was determined using a calcium assay kit (C004-2-1, Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, China).

Bisulfite Conversion and Pyrophosphate Sequencing

The PyroMark Q96 ID Pyrophosphate Sequencing System (Qiagen, Seoul, South Korea) was used to assess the methylation status of various CpG sites within the TSS region of STRA6, TGFB2, and TGFBR2. Primers were designed using PyroMark Assay Design 2.0 (https://www.qiagen.com/us/resources) and featured a biotinylated 5′ end. The quality and integrity of the amplicons were verified via agarose gel electrophoresis prior to pyrophosphate sequencing, as shown in Table S1. Testis DNA was bisulfite-transformed using an EpiTect DNA kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) following the manufacturer's recommendations. Two cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 5 min, incubation at 60°C for 10 min, and subsequent column-based DNA purification were performed. PCR amplification of 25 ng of bisulfite-transformed DNA was performed using a PyroMark PCR kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) with the following PCR conditions: 95°C for 15 min; 45 x (95°C for 30 s; 56°C for 30 s; 72°C for 30 s) and 72°C for 5 min. PCRs reactions were performed in a Veriti 96-well thermal cycler (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), and the quality and size of the amplicons were assessed by agarose gel electrophoresis. Pyrophosphate sequencing was performed on a PyroMark ID pyrophosphate sequencer (Qiagen, Seoul, South Korea) using PyroMark Gold Q96 reagent (Qiagen, Valencia, USA), and methylation levels were calculated using PyroMark Q96 software (version 1.0.10; Qiagen). All pyrophosphate sequencing assays were validated across a range of methylated to unmethylated DNA ratios (0, 10, 25, 50, 75, 90, and 100%) (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), from which standard curves were generated to determine primer sensitivity.

Real-Time qPCR Validation

Total RNA was reverse transcribed according to the instructions of the PrimeScript RT reagent kit (Takara, RR037A, Takara Biomedical Technology, Shiga, Otsu, Japan). Primers for the selected DEGs and the housekeeping gene (Zhang et al., 2021) were designed using Primer Premier 5 software (Table S1). The Primers used were synthesized by Shenzhen BGI Co., Ltd. The qPCR reaction system included 5 μL of qPCR SYBR Green Master Mix; 0.5 μL of forward and reverse Primers, 0.5 μL of cDNA, and 10 μL of ddH2O. The reaction conditions were as follows: 95 °C for 5 min, 40 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, 60 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 10 min. The default settings for the dissolution curve were used. Three replicates were performed for each sample. The relative expression of each gene was calculated using 2−△△CT statistical analysis. All the data are shown as the mean ± SEM.

Isolation and Culture of Leydig Cells From Adult Magang Geese

Under aseptic conditions, the left testis of a mature gander was quickly harvested and placed in ice-cold PBS, and the tunica albuginea and blood vessels were carefully removed to maintain testicular parenchyma integrity. The parenchyma was rinsed in D-Hank's solution, placed in a sterile 50 mL centrifuge tube, and gently disaggregated with tweezers. Next, 0.1% Type II collagenase (1 mg/mL) was added and incubated at 37°C for 2 min, followed by agitation at 200 rpm for 25 min. The digestion process was stopped by adding DMEM-F12 medium, and the mixture was filtered through 70 μm and 40 μm strainers. The filtrate was centrifuged at 1,000 rpm for 5 min to remove the supernatant. The cell pellet was resuspended in DMEM-F12. The cell suspension was incubated with DMEM-F12 containing 10% FBS, 2% antibiotics, and 3β-HSD staining solution at 37°C for 6 h to assess stromal cell proportions. The cell suspension was then layered over Percoll gradients (60, 40, 25, and 17%) and centrifuged at 3,000 rpm at 4°C for 30 min. Cell bands between 25% and 40% Percoll were collected, washed, and resuspended in DMEM-F12 medium supplemented with 10% FBS and 2% antibiotics. For stromal cell culture, cells were adjusted to a concentration of 2 × 106 cells/mL, seeded into 12-well plates, and cultured at 37°C with 5% CO2, 95% O2, and saturated humidity, with medium changes every 48 h.

Following a 48-h cultivation period, the culture medium was removed, and the cells were washed with PBS. Subsequently, a mixture of culture medium supplemented with 3β-HSD staining solution at a 2:1 ratio was added, and the mixture was incubated for more than 6 h. Fields displaying the characteristic black-blue staining were identified, documented, and photographed through microscopic examination.

To investigate the effect of vitamin A supplementation on Leydig cells, Leydig cells were seeded into 24-well culture plates at a density of 1 × 10^6 cells/mL and treated with Retinol (R7632, Sigma-Aldrich) at a concentration of 0, 0.1, 0.5, 1, and 5 μM, respectively. Each group had five replicate wells. After 24 h of cultivation at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere, cells were harvested for total RNA extraction to assess gene expression.

Aim to explore the genetic function of STRA6 on Leydig cells, Leyding cells were seeded at a density of 1 × 10^6 cells/mL in 24-well plates and were transfected at 80% confluency. siRNA oligos were designed and synthesized by Sangon Biotech (see Table S1 for details). The cells were transfected with 25 μM siRNA after 24 h incubation at 37°C. The transfection reagents Lipofectamine 3,000 (L3000001,Thermo Fisher) were used according to the manufacturer's instructions. After 24 h of incubation at 37°C and 5% CO2, the Leydig cells were collected for total RNA extraction to analyze gene expression.

Statistical Analysis

Normal distribution and variance tests were assessed by the D'Agostino & Pearson test and F-test, respectively. Differences between groups were compared using t-test, and statistical analysis was performed using GraphPadPrism 7.0. p < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

RESULTS

Testicular Morphology and Histology During Testicular Regression Induced by a Long-Day Photoperiod

Exposure to long-day photoperiods significantly influences the reproductive status of Magang geese. Substantial differences in testicular size and histology were observed across the 3 groups. Under the influence of long-day photoperiods, both the gonadosomatic index (GSI = gonad mass/body mass × 100%) and testicular volume significantly decreased. Histological of testicular tissue sections revealed a notable decrease in the area of the testicular varicose ducts during prolonged daylight conditions (Figure 1A). This was accompanied by a gradual reduction in the number of spermatogonia, Leydig cells, and spermatozoa, with the RI stage showing an almost complete absence of elongated sperm (Figure 1B). Our results indicate that long-day photoperiods exert an inhibiting effect on the reproductive activity and spermatogenesis in Magang geese gander. The serum FSH, LH, and T concentration showed significant decline during testicular regression induced by long-day photoperiod (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

Effects of photoperiod on the histomorphology of goose testes. (A) The weight ratio of the testes to the body (%). (B) Testicular weight (g). (C) Area of seminiferous tubules (nm2). (D) Histology of the testis by hematoxylin-eosin (H&E): LC, Leydig cells; Spg, spermatogonia; Spz, spermatozoa. The error bars represent the means ± SEMs (n = 8, each period); **p < 0.005, *** p = 0.0001, **** p < 0.0001.

Transcriptome Changes During Testicular Regression Induced by a Long-Day Photoperiod

To determine the effect of transcriptome changes on testicular regression under long-day photoperiods, we generated and analyzed gene-expression data for testes across 3 stages to identify DEGs (Table S3 and Table S4). Principal component analysis (PCA) of the goose testicular transcriptome data revealed significant differences between the groups and high repeatability among the samples (Figure 2A). Based on the number of DEGs between groups, we identified 602 DEGs between RA and RD, including 482 upregulated and 120 downregulated DEGs; 1,899 DEGs between RD and RI, with 699 upregulated and 1,200 downregulated DEGs; and 3,457 DEGs between RA and RI, consisting of 1,659 upregulated and 1,798 downregulated DEGs (Figure 2B). Notably, the number of DEGs significantly increased as the process of reproductive degeneration progressed. Furthermore, cluster analysis of these DEGs revealed five statistically significant clusters (Figure 2C).

Figure 2.

Transcriptome mapping of goose testes and distribution of differentially methylated regions in goose testis. (A) Principal component analysis of goose testis transcriptome data. (B) Number of differentially expressed genes. (C) Cluster map of differentially expressed genes. (D) The genome-wide methylation level of goose testis data. (E) Distribution of methylation levels across genes. (F) Number of differentially methylation regions. (G) The distribution of different methylation regions. High methylation (red) and low methylation (blue).

Gene ontology (GO) analyses were conducted on the DEGs associated with testicular degeneration regulated by a long-day photoperiod (Table S5). The DEGs demonstrated distinct enrichment patterns across the 3 stages. In Clusters 1 and 4, DEGs were enriched in GO categories such as cell cycle, mannose biosynthesis, response to environmental stress, sexual reproduction, and regulation of neuron differentiation. In Cluster 2, DEGs were significantly associated with cell division, chromosome condensation and segregation, and amine metabolic processes. DEGs in Cluster 3 were notably enriched in the regulation of the cell cycle, morphogenesis of anatomical structures, and steroid hormone-mediated signaling pathways. Finally, the GO categories associated with Cluster 5 included neurotransmitter transport, signal transduction, and the regulation of cell death.

KEGG pathway analyses of the DEGs provided a detailed investigation of transcriptome changes across the 3 stages (Table S6). We found significant enrichment of reproduction-related pathways in Cluster 3, including the calcium signaling pathway, TGF-beta signaling pathway, GnRH signaling pathway, thyroid hormone signaling pathway, estrogen signaling pathway, and prolactin signaling pathway. Additionally, pathways involving axon guidance and synapses, such as the serotonergic synapse, glutamatergic synapse, and dopaminergic synapse, were significantly represented. Cluster 5 displayed enriched activity in the PI3K-Akt signaling pathway, focal adhesion, ECM-receptor interaction, axon guidance, and Rap1 signaling pathway. Conversely, Clusters 1, 2, and 4 showed no significant pathway enrichment. For validation, five genes related to the TGF-beta signaling pathway were selected for analysis by qRT-PCR (Figure S1).

DNA Methylation Profiling During Testicular Regression Induced by a Long-Day Photoperiod

Whole-genome bisulfite sequencing (BS-seq) was performed on the testes of Magang geese to explore the methylation changes under long-day photoperiods. The study included 3 biological replicates for each period, with an average sequencing depth of approximately 30X. On average, BS-seq covers more than 85% of all cytosines, including CG, CHG, and CHH (with H representing A, T, or C), in the goose genome (Table S7). The average genome-wide cytosine methylation levels were approximately 86.98, 0.45, and 0.44% in the CG, CHG, and CHH contexts, respectively, in the RA group; approximately 87.48, 0.48, and 0.49% in the CG, CHG, and CHH contexts, respectively, in the RD group; and approximately 87.37, 0.50, and 0.51% in the CG, CHG, and CHH contexts, respectively, in the RI group. CG methylation was predominant in the Magang goose testes, with minimal methylation observed in the CHG or CHH context. The proportion of methylated cytosine in the GC context showed no significant variation between replicates (Table 1, F test, p > 0.05).

Table 1.

Methylation levels in the goose genome in 3 sequence contexts (CG, CHG, and CHH, where H = A, T, or C).

| Condition | Proportion of methylated sites |

Genome-wide methylation level |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CG | CHG | CHH | CG | CHG | CHH | |

| RA | 86.98 ± 0.29 | 0.45 ± 0.01 | 0.44 ± 0.01 | 63.89 ± 1.09 | 0.79 ± 0.00Aa | 0.78 ± 0.01b |

| RD | 87.48 ± 0.17 | 0.48 ± 0.03 | 0.49 ± 0.02 | 66.94 ± 1.34 | 0.79 ± 0.04Bb | 0.80 ± 0.04a |

| RI | 87.37 ± 0.84 | 0.50 ± 0.01 | 0.51 ± 0.02 | 70.49 ± 2.38 | 0.80 ± 0.01a | 0.81 ± 0.01ab |

The different letters indicate the significant levels of variance in methylation levels across individuals between groups. A lowercase letter means P < 0.05, and A uppercase letter means P < 0.01, F test.

We further examined the dynamic changes in DNA methylation level at gene locations during the process of testicular reproductive degeneration under the regulation of a long-day photoperiod.

Analysis of the methylation distribution at gene loci in testicular tissue revealed a significantly greater increase in CG methylation within the gene body than in the transcriptional start site region (TSS) and transcriptional termination region (TES) region (Figure 2E). Conversely, the methylation levels of both CHG and CHH exhibited similar distribution patterns. Notably, long-day photoperiod significantly increased the genome-wide methylation levels in all 3 contexts across the 3 stages of the testes (Figure 2D, T-test, p < 0.05). These findings indicate a differential regulation of gene expression through DNA methylation in the testis under the influence of long-day photoperiod regulation.

Differentially Methylated Regions During Testicular Regression Induced by Long-Day Photoperiod

Consistent with previous studies, DNA methylation in the goose genome occurs primarily at CG sites. To explore the variation in methylation levels in the testis across the RA, RD, and RI stages, we identified DMRs for each comparison group (RA vs. RD, RA vs. RI, RD vs. RI) using a beta-binomial model (Table S8), including DMRs in the CG, CHG, and CHH contexts. Among the 3 comparison groups, we found 4,846 DMRs between RA and RD, comprising 3,904 hypermethylated DMRs and 942 hypomethylated DMRs; 22,399 DMRs between RD and RI, comprising 18,428 hypermethylated DMRs and 3,971 hypomethylated DMRs; and 223,081 DMRs between RA and RI, comprising 208,254 hypermethylated DMRs and 14,827 hypomethylated DMRs. Notably, a substantial increase in CG methylation levels was observed across numerous regions of the testis (Figure 2F). Furthermore, we mapped the DMRs to genomic and genic features and quantified the number of DMRs associated with gene-related hypermethylation and low methylation in CG contexts. Our analysis indicated that the DMRs, especially those that are hypermethylated, are predominantly distributed across various gene-related regions, with significant enrichment in intron regions (Figure 2G).

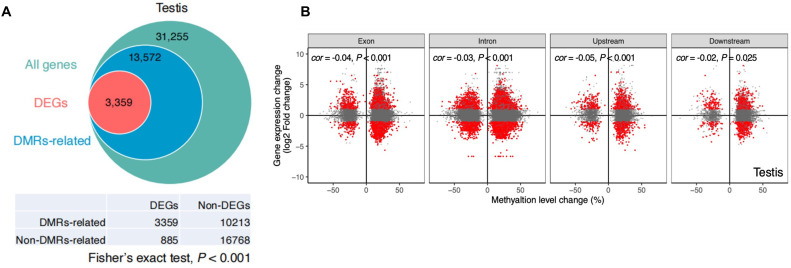

Influence of DNA Methylation on Gene Expression

To explore the potential impact of methylation changes in goose testes on gene expression under a long-day photoperiod, we analyzed the differential gene expression linked to CG DMRs (Figure 3A). A gene was deemed to be associated with CG-DMR if a minimum of one CG-DMR was found either within the gene or in a region extending up to 2 kb upstream or downstream from the gene. Within the testis, 3,359 of 13,572 DMR-associated genes (accounting for 24.8%) were recognized as DEGs across the 3 stages, and Fisher's exact test indicated that DMR-associated genes were significantly more likely to exhibit differential expression (P < 0.001). More than 70% of CG DMR-associated DEGs contained CG DMRs in their introns (Table S9). We investigated the relationship between DNA methylation alterations at CG DMRs and changes in the expression of their associated genes during reproductive degeneration in goose testes under long-day conditions. Our findings demonstrated a notable negative correlation between the DNA methylation level and gene expression. Long-day photoperiod-induced CG methylation changes have a significant negative impact on genome-wide gene expression (Figure 3B). These results suggest that differential gene expression in the testis may be associated with phenotypic characteristics and epigenetic regulation.

Figure 3.

DMR-related genes in goose testes were more likely to be DEGs and the effect of DMRs on gene expression. (A) Changes in DMR methylation and DMR-associated differentially expressed genes in goose testes under photoperiod regulation. (B) The X-axis represents the difference in the methylation of DMRs in each control group, and the Y-axis represents the difference in the expression of DMR-associated genes in the 3 control groups (logarithmic change). Red dots represent genes with significant (Benjamini-Hochberg, FDR<0.05) differential expression. Cor represents the Pearson correlation coefficient, and P indicates a significant difference in the correlation coefficient.

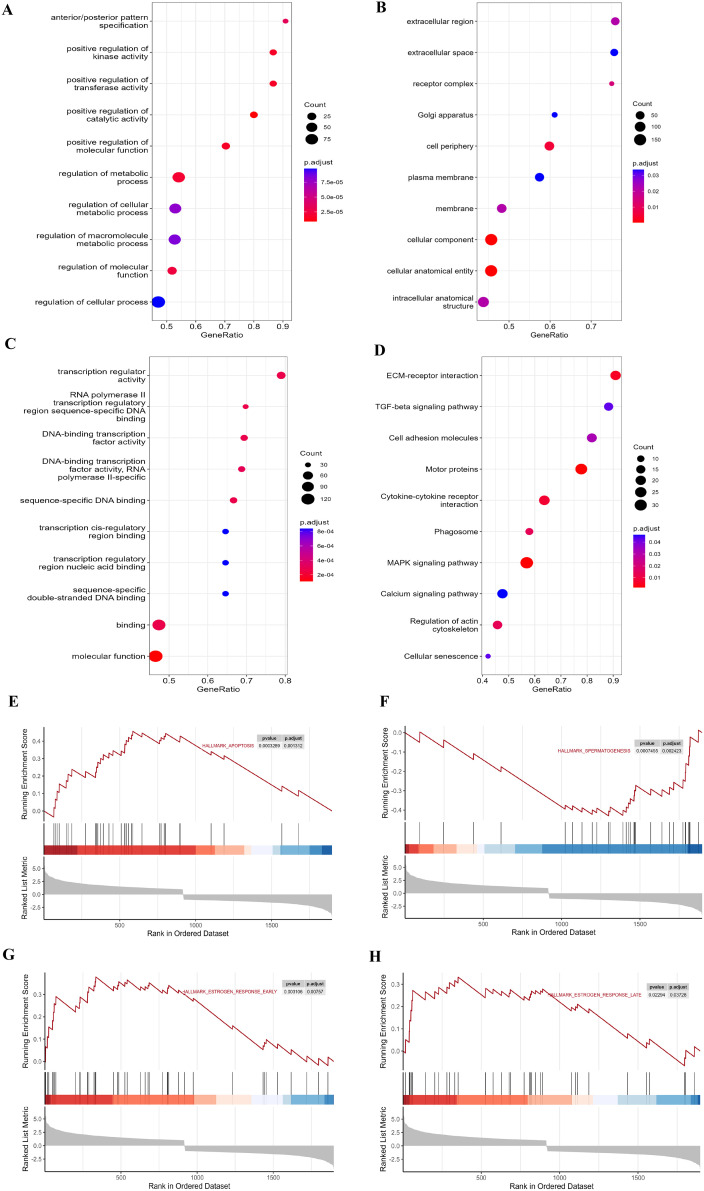

To further identify key molecules and pathways contributing to the reproductive degeneration under long-day conditions, we performed GO annotation analysis and GSEA. The most enriched GO terms in biological processes (BP), cellular components (CC), and molecular function (MF) are presented in Table S10. The analysis between RA and RI highlighted that positive regulation of kinase activity, positive regulation of transferase activity, and positive regulation of catalytic activity were predominant in BP; cell periphery, cellular anatomical entity, and cellular component were highly enriched in CC; and significant enrichment in MF was noted for transcription regulator activity and transcription cis-regulatory region binding (Figures 4A, 4B, and 4C). However, no significant GO term was enriched in the RA and RD comparisons. In the comparison between RA and RI, KEGG pathway analysis revealed significant enrichment of 11 signaling pathways related to DAM-related, including motor proteins, MAPK signaling pathway, cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction, ECM-receptor interaction, regulation of actin cytoskeleton, phagosome, TGF-beta signaling pathway, calcium signaling pathway, cellular senescence, focal adhesion, and cell adhesion molecules (Figure 4D). GSEA revealed the significantly activated enriched hallmark terms associated with apoptosis, estrogen response early, and estrogen response late, while spermatogenesis was identified as a suppressed enrichment term (Figures 4E, 4F, 4G,and 4H).

Figure 4.

KEGG and GSEA of the DMR-related DEGs in goose testes. Gene ontology (GO) analysis for DMR-related DEGs: (A) biological processes (BP), (B) molecular function (MF), and (C) cellular components (CC). (D) The Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment of DMR-related DEGs. (E) The hallmarks gene set database was used to analyze the gene expression values of the RA and RI samples. Significant gene sets were defined as those for which the FDR was < 0.25 and the P-value was < 0.05.

Growing evidence suggests that hypermethylation in the CG context located in the gene body is associated with increased levels of gene expression. Among the genes showing hypermethylation in the CG context within the gene body and higher expression in the RI during the testicular regression, 2 DMR-associated DEGs involved in the response to vitamin A were identified, including STRA6 and RBP5. These findings suggest the important role of vitamin A signaling in testicular regression induced by long-day photoperiods via DNA methylation. Specifically, we focused on the effect of DNA methylation changes on the mRNA expression levels of the genes related to vitamin A signaling and TGF-β signaling pathways in the testis. Pyrosequencing was utilized to assess the methylation levels of STRA6, TGFB2, and TGFBR2 (Table 2). Furthermore, we identified significant differences in genes related to the retinoic acid pathway among the DMR-associated DEGs. We selected 2 upregulated genes (STRA6 and RBP5) and 4 downregulated genes (RBP7, ALDH1A3, CYP27C1, and RARA) for RT-qPCR verification (Figure 5C), and the results were consistent with the RNA-seq data. These findings indicate that the vitamin A signaling may play a crucial role in testicular reproduction. Our results revealed significant variations in methylation levels of the STRA6, TGFB2, and TGFBR2 genes between RA and RI, with an apparent increase in methylation correlating with the progression of testicular regression.

Table 2.

Methylation level of STRA6, TGFB2, and TGFBR2 validated by pyrophosphate sequencing.

| Assay | Condition | Sample ID | Pos. 1 | Pos. 2 | Pos. 3 | Pos. 4 | Mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meth. (%) | Meth. (%) | Meth. (%) | Meth. (%) | ||||

| STRA6 | RA | RA1 | 63.53 | 54.79 | 69.57 | / | 62.63 |

| RA2 | 64.38 | 57.28 | 68.13 | / | 63.26 | ||

| RA3 | 60.07 | 55.27 | 64.69 | / | 60.01 | ||

| RA4 | 59.39 | 55.92 | 69.32 | / | 61.54 | ||

| RA5 | 68.52 | 66.37 | 71.84 | / | 68.91 | ||

| RA6 | 53.31 | 51.45 | 34.42 | / | 46.39 | ||

| RI | RI1 | 68.88 | 60.54 | 64.6 | / | 64.67 | |

| RI2 | 75.27 | 67.86 | 67.82 | / | 70.32 | ||

| RI4 | 68.08 | 57.39 | 64.98 | / | 63.48 | ||

| RI6 | 76.89 | 73.55 | 70.79 | / | 73.74 | ||

| T test | RA vs. RI | <0.05 | |||||

| TGFB2 | RA | RA1 | 52.43 | 59.01 | 79.32 | 60.2 | 62.74 |

| RA2 | 46.19 | 55.84 | 87.01 | 61.72 | 62.69 | ||

| RA3 | 49.69 | 58.71 | 84.41 | 64.08 | 64.22 | ||

| RA4 | 59.27 | 64.5 | 82.17 | 61.22 | 66.79 | ||

| RA5 | 62.26 | 62.64 | 87.68 | 68.1 | 70.17 | ||

| RA6 | 63.26 | 64 | 81.96 | 66.73 | 68.99 | ||

| RI | RI1 | 76.35 | 63.52 | 91.13 | 72.79 | 75.95 | |

| RI2 | 73.75 | 68.05 | 92.23 | 79.06 | 78.27 | ||

| RI3 | 62.47 | 62.58 | 87.41 | 68.88 | 70.34 | ||

| RI4 | 48.63 | 58.63 | 86.9 | 77.34 | 67.88 | ||

| RI5 | 63.82 | 64.72 | 89.36 | 68.82 | 71.68 | ||

| RI6 | 76.11 | 72.22 | 92.03 | 82 | 80.59 | ||

| T test | RA vs. RI | <0.05 | |||||

| TGFBR2 | RA | RA1 | 76.09 | 66.73 | 76.27 | 73.28 | 73.09 |

| RA2 | 73.8 | 64.19 | 72.67 | 69.65 | 70.08 | ||

| RA3 | 75.13 | 62.55 | 74.74 | 72.85 | 71.32 | ||

| RA4 | 79.77 | 67.28 | 77.49 | 75.88 | 75.11 | ||

| RA5 | 82.79 | 74.14 | 82.24 | 78.28 | 79.36 | ||

| RA6 | 82.85 | 70.11 | 82.35 | 77.75 | 78.27 | ||

| RI | RI1 | 96.5 | 80.32 | 88.64 | 90.09 | 88.89 | |

| RI2 | 91.46 | 78.59 | 85.5 | 87.72 | 85.82 | ||

| RI3 | 87.28 | 74.89 | 84.78 | 81.66 | 82.15 | ||

| RI4 | 93.28 | 77.09 | 86.57 | 86.19 | 85.78 | ||

| RI5 | 81.64 | 69.95 | 78.99 | 77.25 | 76.96 | ||

| RI6 | 94.1 | 83.91 | 86.34 | 92.25 | 89.15 | ||

| T test | RA vs. RI | <0.0001 |

One-tailed t test were performed to compare the methylation level of all sites between 2 groups.

Figure 5.

Changes in vitamin A-related metabolites and gene expression in goose testes during reproductive degeneration. (A) Possible pathway for the flow of retinoids in the testis: retinol-RBP-TTR, retinol bound to the retinol binding protein; transthyretin complex; STRA6, stimulated by retinoic acid gene 6 cell membrane receptor; LRAT, lecithin retinol transferase; CRBP, cellular retinol binding protein; RDH, retinol dehydrogenase; ALDH, retinaldehyde dehydrogenase; RA, retinoic acid; CYP26, cytochrome P-450 enzymes from the cyp26 family; RAR, retinoic acid receptor; RXR, rexinoid receptor. (B) Changes in vitamin A- related metabolites in the testis(ng/g) (C) RT‒qPCR validation of retinol pathway-related genes. The error bars represent the means ± SEMs (n = 3–6, each period); * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

Alterations in Vitamin A-Related Metabolite Content in the Testes

Interestingly, in comparison to the RA stage, STRA6 exhibited an increased expression and showed a high methylation level in the CG context within their gene body and promoter in the RI stage (Table S9). As STRA6 is critical for cellular vitamin A uptake and homeostasis, we investigated vitamin A metabolism in goose testes during testicular regression. We quantified the concentrations of vitamin A and its related metabolites across 3 stages by using LC-MS/MS (Figure 5A). Compared to the other 4 vitamin A metabolites, all-trans-retinol showed a high concentration in the testis. We observed a significant decrease in all-trans-retinol and retinyl acetate concentration in the RI stage compared to that in the RA stage (Figure 5B). This reduction in vitamin A metabolite content suggested that a decrease in vitamin A supply may inhibit testicular reproduction and development. Relative to the RA stage, genes involved in vitamin A signaling exhibited dynamic changes, with significantly increased mRNA levels of STRA6 and RBP5 observed in the RI stage (Figure 5C).

The Molecular Function of STRA6 in Steroid Biosynthesis in Leydig Cells in Goose Testes

Recent studies suggest that the role of STRA6 extends beyond mere retinol transportation and also as a significant player within various signaling networks. To explore the impact of vitamin A on the expression of vitamin A signaling and steroid signaling genes in the Leydig cells of Magang geese, we investigated the mRNA level of genes involved in the vitamin A signaling pathway (including STRA6, RBP5, RBP7, ALDH1A3, and RARA), the steroid signaling pathway (such as StAR, HSD17B7, and SRD5A3), and the calmodulin-related gene CaMK4. Employing Ledying cell culture (Figure 6A and 6B), we supplemented the culture medium with vitamin A, and observed a dose-dependent enhancement in the expression levels of STRA6 and RBP5. The introduction of 5 μM vitamin A markedly enhanced the mRNA expression level of genes related to the vitamin A signaling pathway (STRA6 and RBP5), steroid biosynthesis (StAR and SRD5A3), and calmodulin protein CaMK4 (Figures 6C and 6D). To explore the effect of vitamin A on the expression of steroid biosynthesis genes in the Leydig cells of Magang geese, we employed siRNA-mediated knockdown of STRA6 to elucidate the relationship between vitamin A uptake and steroidogenic functionality in Leydig cells. Subsequently, we found that knocking down the STRA6 gene via siRNA significantly increased the expression level of the steroidogenesis gene StAR in Leydig cells but had no significant impact on RBP5 gene expression (Figures 6E and 6F). These results reveal the crucial role of vitamin A in regulating the expression of specific genes in the Leydig cells of Magang geese, particularly within the vitamin A signaling and steroid biosynthesis pathway.

Figure 6.

STRA6 gene expression knockdown by siRNA induces the transport of cholesterol for mitochondrial steroidogenesis in goose Leydig cells. (A) Geese Leydig cells were cultured for 24 h. (B) Expression of 3β-HSD in goose Leydig cells. (C) Treatment of goose Leydig cells with vitamin A markedly elevated the expression of STRA6. (D) The expression of STRA6 and RBP5 significantly increased vitamin A transport in goose Leydig cells and induced cholesterol transport and steroidogenesis. (D) Knockdown of Stra6 increased the expression of StAR in Leydig cells.

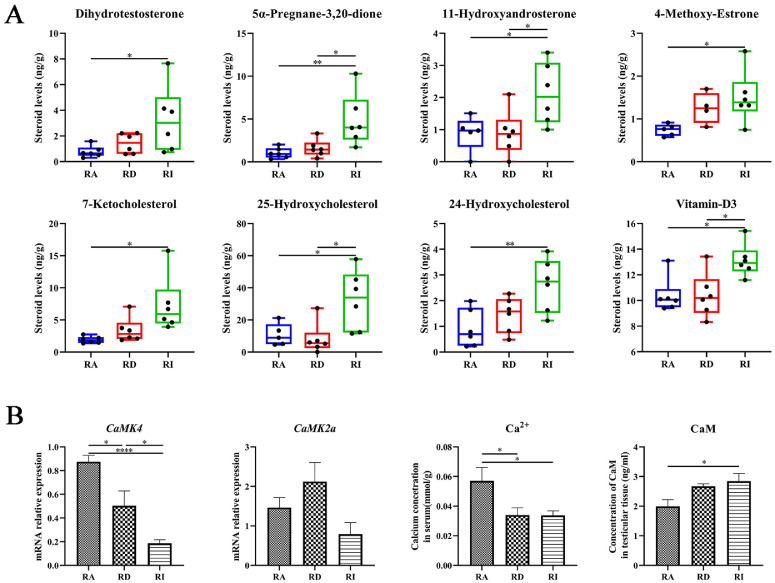

Effects of Photoperiod on Eendogenous Neutral Steroid Metabolism and Ca2+/Calmodulin in Testis

The decrease in reproductive activity in Magang geese may be linked to disrupted steroid production under a long-day photoperiod. To explore the dynamics of endogenous neutral steroids in geese testes, we performed LC-MS/MS to measure the concentration of steroids (Figure 7A). Thirty-one steroids were identified in the testes; 8 of them displayed changes across the 3 stages, indicating alterations in steroid biosynthesis throughout the 3 phases during seasonal testicular regression. The concentrations of endogenous testosterone and androstenedione remained consistent across the RA, RD, and RI stages, while the dihydrotestosterone (DHT) level increased significantly between the RA and RI stages. Additionally, the concentrations of 2 androgen metabolites, 11-hydroxyandrosterone and 25-hydroxyandrosterone, progressively increased during the testicular degeneration of Magang geese, with significant increases between each comparison. The level of vitamin D3, which is crucial for sex hormone synthesis regulation, was markedly higher in the RI stage than in the RA stage. Moreover, we observed that an abnormally high levels of oxysterols accumulated in the testes under the nonbreeding status; 3 oxysterols, 7-ketocholesterol, 25-hydroxycholesterol, and 24-hydroxycholesterol were highly accumulated in the testicular tissues in the RI stage. We also compared the calmodulin content across the 3 stages and detected an increase in calmodulin; notable significant differences were exhibited between the RA and RI stages.

Figure 7.

Alternations in Testicular steroid metabolism and Ca2+ concentration during the reproductive degeneration process in Magang geese. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01,****p < 0.0001 (A) The concentration of endogenous neutral steroids detected in testes at the 3 stages. (B) In calcium signaling, the mRNA level of CaMK4 and CaMK2a, and the concentration of calmodulin were investigated in testes across the 3 stages. Serum calcium (Ca2+ ) concentration was also compared across the 3 stages.

DISCUSSION

Day length is one of the most important factors regulating seasonal reproduction in geese. Male geese undergo a reduction in testis size and a decrease or cessation in sperm production during non-reproductive seasons. They exhibit permeation of the blood–testis barrier, lower testosterone production, complete arrest of spermatogenesis, and inhibited mating behavior. Previous studies have indicated that the cellular mechanism of testicular regression is related to apoptosis in both germ cells and Sertoli cells, as well as a decrease in the number of Leydig cells (Morales et al., 2002; Islam et al., 2012; Jiménez et al., 2015; Beltrán-Frutos et al., 2022; Valentini, et al., 2022). In recent years, the underlying mechanisms involved in testicular regression and loss of fertility in males have been well-studied in mammals (Sharma et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2019; Tabecka-Lonczynska et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2021; Yao et al., 2023a; Yao et al., 2023b). Increasing evidence supports the view that neuroendocrine regulation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–gonad axis is integrally involved in regulating testicular regression in seasonal reproductive breeders (Rosati et al., 2019; An et al., 2023).

Magang geese are short-day breeders that exhibit strict seasonal patterns of breeding. The breeding season of Magang geese generally begins when the day length decreases and ends when the day length increases (Shi et al., 2007b). They mate during times of the year when the day length becomes shorter. When the photoperiod increases, reproductive activity is inhibited, leading to a significant reduction in testicular volume and a decrease in testosterone concentrations (Shi et al., 2007b). However, the genetic mechanism underlying testicular regression in short-day breed Magang geese remains largely unknown. Previous studies have indicated that DNA methylation plays a critical role in testis development and the compensatory response in the testis (Chen et al., 2018b; Wang et al., 2018; Anqi et al., 2022). Through genome-wide DNA methylation analysis, we compared the methylation patterns across the 3 stages of testicular degeneration induced by long-light exposure. In this study, we reported the global methylation patterns of testicular tissues of geese, which are highly similar to those of mammals, and revealed that DNA methylation occurs preferentially at CpG sites in the testes of geese. The average CpG, CHG, and CHH genome-wide scale methylation levels in testicular tissue progressively increased and significant differed during the process of long light-induced testicular degeneration. A Previous study suggested that DNA methylation is involved in light modulation (Takaki et al., 2020) and is a widespread mechanism of light-induced circadian clock plasticity (Azzi et al., 2014). This suggests that DNA methylation patterns play an important role in the HPG axis as a regulatory mechanism in response to photoperiodic changes and contribute to regulating reproductive behavior in seasonal breeders (Stevenson and Prendergast 2013; Viitaniemi et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2023).

At the epigenetic level, the pattern of CpG association with gene features revealed that the intronic regions of the goose genome comprised the largest proportion of DMRs in the testes. Compared to short-day conditions, long-light stimulation induces dramatic CG hypermethylation in the testis. In contrast to the brain, the testis shows great genome instability and predominantly exhibits CG hypermethylation under long-light stimulation. Additionally, at the transcriptome level, the testis contains more DEGs (Liu et al., 2023). The correlation between methylation changes in CG DMRs and expression changes in their associated genes was significant for the genes that contained CG DMRs in their exons, introns, upstream regions, and downstream regions. Significant correlations were detected between the methylation changes in long-light-induced DMRs and the expression changes in the DEGs associated with the DMRs. Therefore, long light-induced CG methylation changes significantly negatively impact genome-wide gene expression in the testis.

To evaluate the potential impact of methylation changes associated with long-light-induced testicular degeneration on gene expression, we examined gene expression associated with CpG DMRs in testicular degeneration. We performed KEGG enrichment analysis, which revealed that pathways related to ECM-receptor interactions, TGF-beta signaling, and focal adhesion were both differentially expressed and methylated across the 3 stages. Previous studies have shown that testosterone-retinoic acid signaling is a key factor in the regulation of seasonal reproduction and spermatogenesis in the testes of plateau pikas (Wang et al., 2019). Retinoic acid plays an important role in testicular development and function, especially spermatogenesis, by regulating the expression of target genes. Gene ontology term enrichment analysis revealed that the 14 DMR-associated DEGs were significantly enriched in response to retinoic acid between the RA and RI comparison. Unlike the findings in mammals, where different genes may be implicated, the genes associated with seasonal testicular degeneration in geese were identified as STRA6, RBP5, and RBP7 instead of STRA8 and RBP4.

In our study, long light-induced testicular regression was associated with alterations in DNA methylation and the expression of genes involved in the vitamin A metabolism pathway. STRA6, a member receptor of the retinol-RBP complex, has been shown to be a bidirectional transporter of vitamin A across blood-tissue barriers (Amengual et al., 2014; Kelly et al., 2016; Dhokia and Macip, 2021), and its regulatory mechanism is controlled by calmodulin, calmodulin significantly affects the vitamin A transport activity of STRA6, and increased calcium/calmodulin promotes the efflux of vitamin A from cells and inhibits the influx of vitamin A through STRA6 (Zhong et al., 2020). Furthermore, Ca2+ signaling regulates vitamin A transport via structural changes in CaM-STRA6 (Young et al., 2021). STRA6 is strongly expressed at the level of blood-organ barriers, exhibiting a high level of expression in Sertoli cells (Bouillet et al., 1997). In our study, STRA6 had a hypermethylated upstream sequence in the RI, which correlated with an increased expression level in these inactive testes. We also detected a higher concentration of calmodulin protein in the testicular homogenate in the RI stage, which suggested a potential correlation between calmodulin dysregulation and reproduction failure. Indeed, vitamin A accumulation significantly decreased in the RI group. Growing evidence supports the view that vitamin A plays an important role in regulating testicular functions. In rodents, vitamin A deficiency has an adverse effect on testosterone secretion (Yang et al., 2018). In adults, an excess of vitamin A leads to an increase in basal testosterone secretion and spermatogenetic disorders (Livera et al., 2002); Consistent with our observations in the testis, insufficient vitamin A and decreased testosterone in the serum of individuals in the RI stage.

Previous studies have shown that loss of STRA6 function is critical for maintaining vitamin A homeostasis in peripheral tissues (Kelly and von Lintig, 2015). STRA6-deficient mice exhibit eye deformities that are characteristic of vitamin A deficiency (Ruiz, et al., 2012). RBP5 is a new member of the classical retinol-binding protein (RBP) family and has been shown to be involved in retinol metabolism (Folli, et al., 2001); with its functional similarity to the other RBPs, RBP5 may affect retinoid uptake. As expected, in goose Leydig cells, the expression levels of both STRA6 and RBP5 was markedly increased in response to vitamin A, as did those of genes involved in the steroidogenesis pathway, including StAR and SRD5A3. Previous studies have shown that retinoids enhance StAR transcription and steroidogenesis (Livera et al., 2002; Manna, et al., 2023). However, very little is known about the relationship between STRA6 and RBP5. STRA6 knockdown did not significantly alter the expression of RBP5 in the Leydig cells of geese.

In addition to the direct effect of vitamin A on steroidogenesis, our results showed a high level of oxysterols present in the testicular tissues in the RI stage. The concentrations of 7-ketocholesterol, 25-hydroxycholesterol, and 24-hydroxycholesterol significantly increased in the RI stage. Current evidence indicates that oxysterols play an important role in cholesterol homeostasis and are extensively involved in inhibiting the biosynthesis of cholesterol (Luu et al., 2016). Oxysterols regulate steroidogenesis through the modulation of StAR activity (King et al., 2004). On the other hand, nuclear receptors for oxysterols are also important regulators of germ cell physiology (Volle et al., 2007; Dallel et al., 2018). LXR can be activated by multiple oxysterols, in LXR null mice, germ cell apoptosis increases, leading to reproductive disorders (Sèdes et al., 2018).7-Ketocholesterol is the predominant and most toxic oxysterol and is associated with many diseases and disabilities associated with aging. The buildup of the 7-ketocholesterol impedes normal cholesterol metabolism and has the ability to significantly stimulate rapid ROS production and, eventually, apoptosis (Anderson et al., 2020).

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, this study provides a comprehensive analysis of genome-wide DNA methylation patterns during long light-induced testicular degeneration in Magang geese. We identified significant changes in DNA methylation across the 3 reproductive stages. Moreover, we discovered numerous genes that exhibited hypermethylation during the seasonal testicular regression occurring in the nonbreeding season for Magang geese. Epigenetic changes in these genes may lead to the efflux of vitamin A from the testicular Leydig cells, thereby contributing to seasonal testicular degeneration.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by Key Area Research and Development Program of Guangdong Province (2020B020222003), the key discipline research capacity improvement project of Guangdong Province (2021ZDJS006), the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (2021A1515010781), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32072730). We sincerely thank Aimei Dai and Zhongqi Liufu at Sun Yat-sen University for the valuable discussion and helpful comments on this manuscript.

Author Contributions: X.S, YB. T, and YM.H conceived the idea and designed the experiments, X.S and YT.F wrote the manuscript, DY.L, YS.W, JX.L, YL.X, X.S, and YT, F performed experiments and data analysis, JQ.P, DL.J, and HJ.OY helped to collect the samples. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics Approval: All experimental animal procedures complied with the laboratory animal management and welfare regulations approved by the Experimental Animal Ethics Committee of Zhongkai University of Agriculture and Engineering (EAEC-ZHKU, Guangzhou, Guangdong, China), under permit NO.2019120310. All efforts have been made to minimize animal suffering.

Consent for Publication: Not applicable.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data sets supporting the results of this article were included within the article and additional files. The raw sequence data reported in this paper have been deposited in the Genome Sequence Archive (Genomics, Proteomics & Bioinformatics 2021) at National Genomics Data Center (Nucleic Acids Res 2022), China National Center for Bioinformation / Beijing Institute of Genomics, Chinese Academy of Sciences (Bio-Project of Bisulfite sequencing data and RNA-seq data: PRJCA021186; GSA accession of Bisulfite sequencing data and RNA-seq data: CRA013708) that are publicly accessible at https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa.

DISCLOSURES

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.psj.2024.103769.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

Table S1. Primers used for the real-time quantitative PCR, bisulfite sequencing PCR and pyrosequencing

Table S2. List of steroid metabolites and vitamin A metabolites detected in testes.

Table S3. Summary of transcriptome sequencing data

Table S4. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) identified among the 3 comparison groups

Table S5. GO enrichment in DEGs

Table S6. KEGG enrichment analysis of DEGs

Table S7. Summary of whole-genome bisulfite sequencing data

Table S8. Detail of the significant differentially Methylated regions identified among the 3 comparison groups

Table S9. DMR-related DEGs among the 3 stages under long-day conditions

Table S10. GO enrichment and KEGG enrichment in DMR-associated DEGs

Figure S1. Real-time qPCR validated the mRNA level of TGF-beta signaling

REFERENCES

- Akalin A., Kormaksson M., Li S., Garrett-Bakelman F.E., Figueroa M.E., Melnick A., Mason C.E. methylKit: a comprehensive R package for the analysis of genome-wide DNA methylation profiles. Genome Biol. 2012;13:R87. doi: 10.1186/gb-2012-13-10-r87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarado S., Fernald R.D., Storey K.B., Szyf M. The dynamic nature of DNA methylation: a role in response to social and seasonal variation. Integr. Comp. Biol. 2014;54:68–76. doi: 10.1093/icb/icu034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amengual J., Zhang N., Kemerer M., Maeda T., Palczewski K., Von Lintig J. STRA6 is critical for cellular vitamin A uptake and homeostasis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2014;23:5402–5417. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An K., Yao B., Tan Y., Kang Y., Su J. Potential role of anti-müllerian hormone in regulating seasonal reproduction in animals: the example of males. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24 doi: 10.3390/ijms24065874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson A., Campo A., Fulton E., Corwin A., Jerome W.G., 3rd, O'Connor M.S. 7-Ketocholesterol in disease and aging. Redox Biol. 2020;29 doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2019.101380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anqi Y., Saina Y., Chujie C., Yanfei Y., Xiangwei T., Jiajia M., Jiaojiao X., Maoliang R., Bin C. Regulation of DNA methylation during the testicular development of Shaziling pigs. Genomics. 2022;114 doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2022.110450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azzi A., Dallmann R., Casserly A., Rehrauer H., Patrignani A., Maier B., Kramer A., Brown S.A. Circadian behavior is light-reprogrammed by plastic DNA methylation. Nature Neurosci. 2014;17:377–382. doi: 10.1038/nn.3651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beltrán-Frutos E., Seco-Rovira V., Martínez-Hernández J., Ferrer C., Serrano-Sánchez M.I., Pastor L.M. Cellular modifications in spermatogenesis during seasonal testicular regression: an update review in mammals. Animals (Basel) 2022;12 doi: 10.3390/ani12131605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y., Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate - a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. Royal Statist. Soc., Series B. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Bolger A.M., Lohse M., Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouillet P., Sapin V., Chazaud C., Messaddeq N., Décimo D., Dollé P., Chambon P. Developmental expression pattern of Stra6, a retinoic acid-responsive gene encoding a new type of membrane protein. Mech. Dev. 1997;63:173–186. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(97)00039-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bu D., Luo H., Huo P., Wang Z., Zhang S., He Z., Wu Y., Zhao L., Liu J., Guo J., Fang S., Cao W., Yi L., Zhao Y., Kong L. KOBAS-i: intelligent prioritization and exploratory visualization of biological functions for gene enrichment analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;49:W317–W325. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkab447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S., Zhou Y., Chen Y., Gu J. fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics. 2018;34:i884–i890. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Shen L.H., Gui L.X., Yang F., Li J., Cao S.Z., Zuo Z.C., Ma X.P., Deng J.L., Ren Z.H., Chen Z.X., Yu S.M. Genome-wide DNA methylation profile of prepubertal porcine testis. Reprod. Fertil. Dev. 2018;30:349–358. doi: 10.1071/RD17067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallel S., Tauveron I., Brugnon F., Baron S., Lobaccaro J.M.A., Maqdasy S. Liver X receptors: a possible link between lipid disorders and female infertility. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018;19:2177. doi: 10.3390/ijms19082177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhokia V., Macip S. A master of all trades – linking retinoids to different signalling pathways through the multi-purpose receptor STRA6. Cell Death Discov. 2021;7:358. doi: 10.1038/s41420-021-00754-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Follett B.K., Maung S.L. Rate of testicular maturation, in relation to gonadotrophin and testosterone levels, in quail exposed to various artificial photoperiods and to natural daylengths. J. Endocrinol. 1978;78:267–280. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.0780267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folli C., Calderone V., Ottonello S., Bolchi A., Zanotti G., Stoppini M., Berni R. Identification, retinoid binding, and x-ray analysis of a human retinol-binding protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2001;98:3710–3715. doi: 10.1073/pnas.061455898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gumułka M., Hrabia A., Rozenboim I. Alterations in gonadotropin, prolactin, androgen and estrogen receptor and steroidogenesis-associated gene expression in gander testes in relation to the annual period. Theriogenology. 2023;205:94–105. doi: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2023.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He X., Wang W., Sun W., Chu M. Photoperiod induces DNA methylation changes in the melatonin receptor 1A. Gene in Ewes. Animals (Basel) 2023;13 doi: 10.3390/ani13121917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y.M., Shi Z.D., Liu Z., Liu Y., Li X.W. Endocrine regulations of reproductive seasonality, follicular development and incubation in Magang geese. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2008;104:344–358. doi: 10.1016/j.anireprosci.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Islam M.N., Tsukahara N., Sugita S. Apoptosis-mediated seasonal testicular regression in the Japanese Jungle Crow (Corvus macrorhynchos) Theriogenology. 2012;77:1854–1865. doi: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2012.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez R., Burgos M., Barrionuevo F.J. Circannual testis changes in seasonally breeding mammals. Sexual Develop. 2015;9:205–215. doi: 10.1159/000439039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanehisa M. Toward understanding the origin and evolution of cellular organisms. Protein Sci. 2019;28:1947–1951. doi: 10.1002/pro.3715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanehisa M., Furumichi M., Sato Y., Kawashima M., Ishiguro-Watanabe M. KEGG for taxonomy-based analysis of pathways and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023;51:D587–d592. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkac963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanehisa M., Goto S. KEGG: kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:27–30. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly M., von Lintig J. STRA6: role in cellular retinol uptake and efflux. Hepatobiliary Surg. Nutr. 2015;4:229–242. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2304-3881.2015.01.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly M., Widjaja-Adhi M.A., Palczewski G., von Lintig J. Transport of vitamin A across blood-tissue barriers is facilitated by STRA6. Faseb J. 2016;30:2985–2995. doi: 10.1096/fj.201600446R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D., Paggi J.M., Park C., Bennett C., Salzberg S.L. Graph-based genome alignment and genotyping with HISAT2 and HISAT-genotype. Nature Biotechnol. 2019;37:907–915. doi: 10.1038/s41587-019-0201-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King S.R., Matassa A.A., White E.K., Walsh L.P., Jo Y., Rao R.M., Stocco D.M., Reyland M.E. Oxysterols regulate expression of the steroidogenic acute regulatory protein. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2004;32:507–517. doi: 10.1677/jme.0.0320507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuenzel W.J. Research advances made in the avian brain and their relevance to poultry scientists. Poult. Sci. 2014;93:2945–2952. doi: 10.3382/ps.2014-04408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuenzel W.J., Kang S.W., Zhou Z.J. Exploring avian deep-brain photoreceptors and their role in activating the neuroendocrine regulation of gonadal development. Poult. Sci. 2015;94:786–798. doi: 10.3382/ps.2014-04370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leska A., Kiezun J., Kaminska B., Dusza L. Seasonal changes in the expression of the androgen receptor in the testes of the domestic goose (Anser anser f. domestica) Gen Comp. Endocrinol. 2012;179:63–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2012.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Xu Y., Wang Y., Zhang J., Fu Y., Liufu S., Jiang D., Pan J., Ouyang H., Huang Y., Tian Y., Shen X. The DNA methylation status of the serotonin metabolic pathway associated with reproductive inactivation induced by long-light exposure in Magang geese. BMC Genomics. 2023;24:355. doi: 10.1186/s12864-023-09342-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livera G., Rouiller-Fabre V., Pairault C., Levacher C., Habert R. Regulation and perturbation of testicular functions by vitamin A. Reproduction. 2002;124:173–180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Love M.I., Huber W., Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014;15:550. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luu W., Sharpe L.J., Capell-Hattam I., Gelissen I.C., Brown A.J. Oxysterols: old tale, new twists. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2016;56:447–467. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010715-103233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch E.W., Coyle C.S., Lorgen M., Campbell E.M., Bowman A.S., Stevenson T.J. Cyclical DNA methyltransferase 3a expression is a seasonal and estrus timer in reproductive tissues. Endocrinology. 2016;157:2469–2478. doi: 10.1210/en.2015-1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manna P.R., Reddy A.P., Pradeepkiran J.A., Kshirsagar S., Reddy P.H. Regulation of retinoid mediated StAR transcription and steroidogenesis in hippocampal neuronal cells: Implications for StAR in protecting Alzheimer's disease. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2023;1869 doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2022.166596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales E., Pastor L.M., Ferrer C., Zuasti A., Pallarés J., Horn R., Calvo A., Santamaría L., Canteras M. Proliferation and apoptosis in the seminiferous epithelium of photoinhibited Syrian hamsters (Mesocricetus auratus) Int. J. Androl. 2002;25:281–287. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2605.2002.00363.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakao N., Ono H., Yamamura T., Anraku T., Takagi T., Higashi K., Yasuo S., Katou Y., Kageyama S., Uno Y., Kasukawa T., Iigo M., Sharp P.J., Iwasawa A., Suzuki Y., Sugano S., Niimi T., Mizutani M., Namikawa T., Ebihara S., Ueda H.R., Yoshimura T. Thyrotrophin in the pars tuberalis triggers photoperiodic response. Nature. 2008;452:317–322. doi: 10.1038/nature06738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan J.Q., Liufu S., Sun J.F., Chen W.J., Ouyang H.J., Shen X., Jiang D.L., Xu D.N., Tian Y.B., He J.H., Huang Y.M. Long-day photoperiods affect expression of OPN5 and the TSH-DIO2/DIO3 pathway in Magang goose ganders. Poult. Sci. 2022;101 doi: 10.1016/j.psj.2022.102024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rader M.A., Jaime O.G., Abarca V.O., Young K.A. Photoperiod alters testicular methyltransferase complex mRNA expression in Siberian hamsters. Gen. Comparat. Endocrinol. 2023;333 doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2022.114186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosati L., Di Fiore M.M., Prisco M., Di Giacomo Russo F., Venditti M., Andreuccetti P., Baccari G.C., Santillo A. Seasonal expression and cellular distribution of star and steroidogenic enzymes in quail testis. J. Exp. Zool. B Mol. Dev. Evol. 2019;332:198–209. doi: 10.1002/jez.b.22896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz A., Mark M., Jacobs H., Klopfenstein M., Hu J., Lloyd M., Habib S., Tosha C., Radu R.A., Ghyselinck N.B., Nusinowitz S., Bok D. Retinoid content, visual responses, and ocular morphology are compromised in the retinas of mice lacking the retinol-binding protein receptor, STRA6. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2012;53:3027–3039. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-8476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sèdes L., Thirouard L., Maqdasy S., Garcia M., Caira F., Lobaccaro J.A., Beaudoin C., Volle D.H. Cholesterol: a gatekeeper of male fertility? Front. Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2018;9:369. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2018.00369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma A., Das S., Kumar V. Transcriptome-wide changes in testes reveal molecular differences in photoperiod-induced seasonal reproductive life-history states in migratory songbirds. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 2019;86:956–963. doi: 10.1002/mrd.23155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma A., Das S., Sur S., Tiwari J., Chaturvedi K., Agarwal N., Malik S., Rani S., Kumar V. Photoperiodically driven transcriptome-wide changes in the hypothalamus reveal transcriptional differences between physiologically contrasting seasonal life-history states in migratory songbirds. Sci. Rep. 2021;11:12823. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-91951-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Z.D., Huang Y.M., Liu Z., Liu Y., Li X.W., Proudman J.A., Yu R.C. Seasonal and photoperiodic regulation of secretion of hormones associated with reproduction in Magang goose ganders. Domest. Anim. Endocrinol. 2007;32:190–200. doi: 10.1016/j.domaniend.2006.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Z.D., Huang Y.M., Liu Z., Liu Y., Li X.W., Proudman J.A., Yu R.C. Seasonal and photoperiodic regulation of secretion of hormones associated with reproduction in Magang goose ganders. Domest. Anim. Endocrinol. 2007;32:190–200. doi: 10.1016/j.domaniend.2006.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Z.D., Tian Y.B., Wu W., Wang Z.Y. Controlling reproductive seasonality in the geese: a review. World's Poult. Sci. J. 2008;64:343–355. [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson T.J., Prendergast B.J. Reversible DNA methylation regulates seasonal photoperiodic time measurement. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2013;110:16651–16656. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1310643110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun L., Guo L., Wang J., Li M., Appiah M.O., Liu H., Zhao J., Yang L., Lu W. Photoperiodic effect on the testicular transcriptome in broiler roosters. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. (Berl) 2020;104:918–927. doi: 10.1111/jpn.13336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabecka-Lonczynska A., Mytych J., Solek P., Koziorowski M. Autophagy as a consequence of seasonal functions of testis and epididymis in adult male European bison (Bison bonasus, Linnaeus 1758) Cell Tissue Res. 2020;379:613–624. doi: 10.1007/s00441-019-03111-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takaki N., Uchiwa T., Furuse M., Yasuo S. Effect of postnatal photoperiod on DNA methylation dynamics in the mouse brain. Brain Res. 2020;1733 doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2020.146725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tennenbaum S.R., Bortner R., Lynch C., Santymire R., Crosier A., Santiestevan J., Marinari P., Pukazhenthi B.S., Comizzoli P., Hawkins M.T.R., Maldonado J.E., Koepfli K.P., vonHoldt B.M., DeCandia A.L. Epigenetic changes to gene pathways linked to male fertility in ex situ black-footed ferrets. Evol Appl. 2024;17:e13634. doi: 10.1111/eva.13634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentini L., Zupa R., Pousis C., Cuko R., Corriero A. Proliferation and apoptosis of cat (Felis catus) male germ cells during breeding and non-breeding seasons. Vet. Sci. 2022;9 doi: 10.3390/vetsci9080447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viitaniemi H.M., Verhagen I., Visser M.E., Honkela A., van Oers K., Husby A. Seasonal variation in genome-wide DNA methylation patterns and the onset of seasonal timing of reproduction in great tits. Genome Biol. Evol. 2019;11:970–983. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evz044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volle D.H., Mouzat K., Duggavathi R., Siddeek B., Déchelotte P., Sion B., Veyssière G., Benahmed M., Lobaccaro J.M. Multiple roles of the nuclear receptors for oxysterols liver X receptor to maintain male fertility. Mol. Endocrinol. 2007;21:1014–1027. doi: 10.1210/me.2006-0277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Jin L., Ma J., Chen L., Fu Y., Long K., Hu S., Song Y., Shang D., Tang Q., Wang X., Li X., Li M. Hemicastration induced spermatogenesis-related DNA methylation and gene expression changes in mice testis. Asian-Australas J. Anim. Sci. 2018;31:189–197. doi: 10.5713/ajas.17.0518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Su R., Liu P., Yuan Z., Han Y., Zhang H., Weng Q. Seasonal changes of mitochondrial autophagy and oxidative response in the testis of the wild ground squirrels (Spermophilus dauricus) Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2021;321:R625–r633. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00105.2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.J., Jia G.X., Yan R.G., Guo S.C., Tian F., Ma J.B., Zhang R.N., Li C., Zhang L.Z., Du Y.R., Yang Q.E. Testosterone-retinoic acid signaling directs spermatogonial differentiation and seasonal spermatogenesis in the Plateau pika (Ochotona curzoniae) Theriogenology. 2019;123:74–82. doi: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2018.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y., Luo J., Yu D., Zhang T., Lin Q., Li Q., Wu X., Su Z., Zhang Q., Xiang Q., Huang Y. Vitamin A promotes Leydig cell differentiation via alcohol dehydrogenase 1. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 2018;9:644. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2018.00644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao B., An K., Kang Y., Tan Y., Zhang D., Su J. Reproductive suppression caused by spermatogenic arrest: transcriptomic evidence from a non-social animal. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023;24:4611. doi: 10.3390/ijms24054611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao B., Tan Y., An K., Kang Y., Hou Q., Zhang D., Su J. Seasonal patterns of miRNA and mRNA expression profiles in the testes of plateau zokors (Eospalax baileyi) Comparat. Biochem Physiol. Part D. 2023;48 doi: 10.1016/j.cbd.2023.101143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young B.D., Varney K.M., Wilder P.T., Costabile B.K., Pozharski E., Cook M.E., Godoy-Ruiz R., Clarke O.B., Mancia F., Weber D.J. Physiologically relevant free Ca(2+) ion concentrations regulate STRA6-calmodulin complex formation via the BP2 region of STRA6. J Mol Biol. 2021;433 doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2021.167272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakane Y., Y T. Photoperiodic regulation of reproduction in vertebrates. Annu. Rev. Anim. Biosci. 2019;15:173–194. doi: 10.1146/annurev-animal-020518-115216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B.B., Shen X., Li X.J., Tian Y.B., Ouyang H.J., Huang Y.M. Reference gene selection for expression studies in the reproductive axis tissues of Magang geese at different reproductive stages under light treatment. Sci. Rep. 2021;11:7573. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-87169-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong M., Kawaguchi R., Costabile B., Tang Y., Hu J., Cheng G., Kassai M., Ribalet B., Mancia F., Bok D., Sun H. Regulatory mechanism for the transmembrane receptor that mediates bidirectional vitamin A transport. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2020;117:9857–9864. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1918540117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu H., Chen Z., Shao X., Yu J., Wei C., Dai Z., Shi Z. Reproductiveaxis gene regulation during photostimulation and photorefractoriness in Yangzhou goose ganders. Front. Zool. 2017;14:11. doi: 10.1186/s12983-017-0200-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Primers used for the real-time quantitative PCR, bisulfite sequencing PCR and pyrosequencing

Table S2. List of steroid metabolites and vitamin A metabolites detected in testes.

Table S3. Summary of transcriptome sequencing data

Table S4. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) identified among the 3 comparison groups

Table S5. GO enrichment in DEGs

Table S6. KEGG enrichment analysis of DEGs

Table S7. Summary of whole-genome bisulfite sequencing data

Table S8. Detail of the significant differentially Methylated regions identified among the 3 comparison groups

Table S9. DMR-related DEGs among the 3 stages under long-day conditions

Table S10. GO enrichment and KEGG enrichment in DMR-associated DEGs

Figure S1. Real-time qPCR validated the mRNA level of TGF-beta signaling