Harold Shipman's murderous career led to demands that steps be taken to prevent any recurrence, but devising an acceptable and workable method of monitoring mortality rates in individual general practices is not a simple matter

Soon after the publication of the review of Harold Shipman's clinical practice,1 one of us (RB) went to a meeting for families of possible victims of Shipman. Each of the 100 people present was facing the possibility that at least one member of their family had been murdered by their general practitioner. They wanted the review explained, and to ask questions about how the health service had failed to detect Shipman's murders. One person asked, “How will I be able to trust a doctor again?” Whatever the answer given at the time, the only adequate response must be a collective one from the medical profession and its regulators together. One such response, recommended in the review of Shipman's clinical practice, would be the development of a system to monitor the mortality of general practitioners' patients.

Our aim in this paper is to stimulate debate about monitoring mortality in general practice; an appropriately designed system, as well as detecting illegal behaviour, might help general practitioners to plan improved methods of care.

Summary points

Analysis of excess numbers of deaths among Harold Shipman's patients reached a figure similar to the total determined by the inquiry

Monitoring mortality rates among general practitioners' patients would help maintain public trust

Such a system could detect high mortality at an early stage by using valid local comparative data and information about non-fatal outcomes

Procedures for investigating abnormal patterns need to be agreed

A monitoring system could also provide practices with information to help select clinical policies to reduce mortality

Findings of the review

Firstly, drawing on the review and updated information reported to the Shipman Inquiry, we summarise key findings relevant to our later consideration of monitoring.2 Shipman worked in a group practice in West Yorkshire from 1974 to 1975. After a break in his career following conviction for drug offences, he worked in a group practice in Hyde, Greater Manchester, from 1977 to 1992. From 1992 to 1998, he practised single handedly in Hyde. In January 2000, he was convicted of the murder of 15 of his older female patients. In investigating deaths of Shipman's patients, the review used four sources of evidence.

Clinical records—On the basis of clinical judgment about the relation between certified cause of death and clinical history, and the features typical of the convictions (for example, Shipman's presence at death), review of 180 records of patients for whom Shipman had issued a death certificate resulted in 102 deaths being classified as highly suspicious and 39 as moderately so.

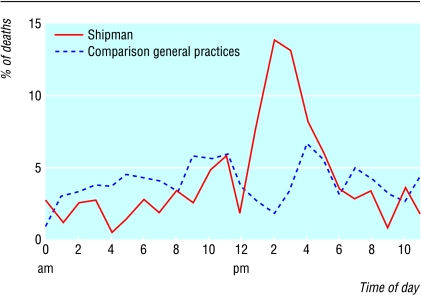

Cremation forms—Shipman's cremation forms were compared with those completed by a matched sample of six local general practitioners selected as having similar patient populations and periods of practice to Shipman. He recorded that he was present at death more commonly than did the other general practitioners (19.5% v 1%), although relatives or carers were less likely to have been present (40.1% v 80.2%). A peak in the proportion of deaths among Shipman's patients occurred between 1 pm and 6 pm (fig 1), and the proportion of patients reported as dying quickly (within 29 minutes) was higher (60% v 23%).

Figure 1.

Percentage of deaths occurring at different times of day

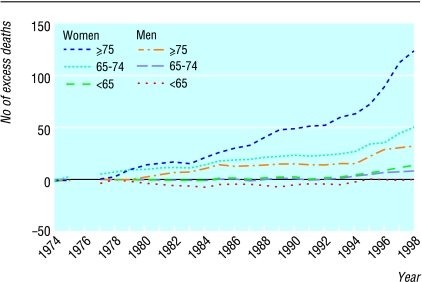

All death certificates signed by Shipman from 1974 onwards—Comparison with the same six general practitioners from Hyde, plus four from Todmorden, resulted in an excess of 236 deaths (95% confidence interval 198 to 277) certified by Shipman in 1974-98 that had occurred at the patient's home or on the practice premises. The excess was greatest among women aged 75 or above, but there were also smaller excesses in other subgroups (fig 2).

Figure 2.

Cumulative excess of Shipman's over comparison general practices' deaths occurring at home or on practice premises

Analysis of deaths of all patients registered with Shipman at any time in 1987-98—Mortality among Shipman's patients was compared with rates for England and Wales, manufacturing districts as defined by the Office for National Statistics, and the local health district (Tameside). The analysis reported in the review has been updated,2 and excesses of 152 (141 women) in comparison with Tameside, 176 (153 women) compared with manufacturing districts, and 197 (162 women) compared with England and Wales have been identified. These estimates are broadly similar to the analysis of deaths certified by Shipman that had occurred at home or on his practice premises.

Requirements for monitoring mortality

We searched Medline for reports of monitoring mortality rates in general practice, and it became clear that except for a few local schemes, monitoring systems are not yet established. The introduction of effective monitoring is not straightforward. Various sets of data are available in principle, and several approaches to their analysis and interpretation have already been explored. However, within the limitations of available resources, the actions proposed in response to monitoring reports should dictate data and analysis needs, rather than the actions being shaped by data availability.3

Although it is a priority to detect serial killing as early as possible, it is unlikely that methods of future killings will match Shipman's exactly, and therefore monitoring should be designed for the early detection of aberrant behaviour more generally, as reflected in mortality patterns. Early identification of the more extreme patterns within the normal range is also desirable. Detection of aberrant and normal variations should be considered separately, since decisions and actions consequent on their detection, as well as data collection and analysis, are likely to differ. For example, a signal suggesting aberrant behaviour would result in further investigation independently of, and perhaps unknown to, the general practitioner concerned, and with the possibility of subsequent professional sanctions or legal action. Signals showing that mortality patterns are at the extremes of normal might also prompt investigation, but usually in collaboration with the general practitioner, and with the intention of providing appropriate support (or of learning lessons for dissemination of good practice if the observed patterns are favourably extreme).

Different approaches, and possibly even different monitoring systems, are required to meet these objectives. Each should be tuned as far as possible to optimise performance towards their stated ends. Early identification of general practitioners with high death rates among their patients without generating many false positives is required in any such system (box B1), but introduction of a sufficiently sensitive and specific system will prove difficult for several reasons.

Box 1.

A system to monitor patient mortalities in general practice to detect murder must:

- Be sensitive (lead to few false negatives)

- Be specific (lead to few false positives)

- Provide data meaningful to general practitioners and public health physicians

- Require a minimum of expertise and resources to maintain

- Be acceptable to practitioners

- Be acceptable to patients

Only a small number of patients registered with a general practitioner die each year, and random year to year variation makes detection of an abnormally high number of deaths in any particular year difficult.4 In the analysis of Shipman's certificates an excess accumulated over 24 years of clinical practice was reported, but in prospective monitoring, an epoch as long as 24 years would be unhelpful.

The review of Shipman's clinical practice was retrospective, but a well defined “trigger” criterion with known statistical properties would be needed for prospective monitoring. A recent paper5 has shown that a finely tuned procedure would have allowed early detection of Shipman's excess deaths. However, neither this nor other techniques6–13 will eliminate false positives if the detection level is set low enough to be useful in routine prospective monitoring.

Monitoring should also be practical in routine use by general practitioners or public health physicians, and not be unduly complex or costly to administer. Finally, the procedures for investigation of highlighted doctors must be developed and evaluated with care. A legitimate clinical reason will usually explain the observed rates, and therefore a transparently fair and professionally supportive process is required.

Desirable features of monitoring systems

The ability of a monitoring system to detect high mortality rates at an early stage might be improved by several features (box B2). The choice of data for comparison will influence the interpretation of observed differences in mortality rates. In reviewing Shipman's clinical practice, a matched group of local doctors was selected in the report. In a monitoring system, comparisons based on knowledge of local populations, general practitioners' working patterns, and numbers of deaths in hospitals would increase the confidence that could be placed in the findings. Analysis of mortality in patient age and sex subgroups by cause of death and by circumstances of death (including the people who were present and time of death) would be desirable. Information about adverse events and non-fatal outcomes such as myocardial infarction or stroke would help complete the picture.14,15

Box 2.

Features to improve ability of a monitoring system to detect abnormal practice and inform clinical policies

- Valid local comparative data

- Information in age and sex subgroups

- Additional information about circumstances of death

- Classification by cause of death

- Data about adverse events and selected non-fatal outcomes

- Adjustment for the numbers of patients cared for by the general practitioner

There will still be limitations. For example, monitoring of particular subgroups of general practitioners, such as locums, assistants, and those caring for people in hospices, may be difficult if not impossible. Similarly, in practices that operate shared list systems, analysis by individual practice may be the only option.

Mortality monitoring for planning and improving care

Since murder by general practitioners is exceptional, any system that is introduced simply to detect it might have fallen into disuse by the time such an event recurs. However, better information about mortality rates in general practice could also facilitate the planning and monitoring of clinical policies to gradually reduce mortality. Whether both objectives can be achieved by a single monitoring system remains to be seen.

Some general practitioners already collect information about the numbers of deaths of patients registered with their practices. Examples include the collection of data in individual practices,16,17 groups of practices, 18 and a district.19 Others have audited deaths to identify aspects of care that could be improved.20–22 Furthermore, one report showed that one general practitioner's work was associated with reduced mortality among his patients.23

A monitoring system would have to be sensitive to changes in mortality rates in small populations if it is to be used by practices for developing clinical policies. Information about selected process indicators would help in the interpretation of differences in mortalities between practices with similar populations. Monitoring will thus require an understanding of general practitioners' patterns of work and reliable judgments about which practices and which doctors have similar patients. Local organisations such as primary care trusts would have a key role to play. The creation of such a system to monitor, and perhaps reduce, mortality in general practice would be one response to that doubting relative's question about trust.

Letters p 280

Footnotes

Funding: None.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Baker R. Harold Shipman's clinical practice. 1974-1998. London: Stationery Office; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 2. The Shipman Inquiry. www.shipman-inquiry.org.uk/documentday.asp?from=a&day=5 (accessed 14 Nov 2002).

- 3.Dowie J. Decision validity should determine whether a generic or condition-specific HRQOL measure is used in health care decisions. Health Economics. 2002;11:1–8. doi: 10.1002/hec.667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frankel S, Sterne J, Smith GD. Mortality variations as a measure of general practitioner performance: implications of the Shipman case. BMJ. 2000;320:489. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7233.489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Spiegelhalter DJ, Kindsman R, Grigg O, Treasure T. Risk adjusted sequential probability ratio tests: applications to Bristol, Shipman, and adult cardiac surgery. Int J Qual Health Care (in press). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Mohammed MA, Cheng KK, Rouse A, Marshall T. Bristol, Shipman, and clinical governance: Shewhart's forgotten lessons. Lancet. 2001;357:463–467. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)04019-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adab P, Rouse AM, Mohammed MA, Marshall T. Performance league tables: The NHS deserves better. BMJ. 2002;324:95–98. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7329.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Austin PC, Naylor CD, Tu JV. A comparison of a Bayesian vs. a frequentist method for profiling hospital performance. J Eval Clin Pract. 2001;7:35–45. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2753.2001.00261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lawrence RA, Dorsch MF, Sapsford RJ, Mackintosh AF, Greenwood DC, Jackson BM, et al. Use of cumulative mortality data in patients with acute myocardial infarction for early detection of variation in clinical practice: observational study. BMJ. 2001;323:324–327. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7308.324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bolsin S, Colson M. The use of the Cusum technique in the assessment of trainee competence in new procedures. Int J Qual Healthcare. 2000;12:433–438. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/12.5.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ramsay CR, Grant AM, Wallace SA, Garthwaite PH, Monk AF, Russell IT. Statistical assessment of the learning curves of health technologies. Health Technol Assess. 2001;5(12):1–98. doi: 10.3310/hta5120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aylin P, Alves B, Best N, Cook A, Elliott P, Evans SJW, et al. Comparison of UK paediatric cardiac surgical performance by analysis of routinely collected data 1984-96; was Bristol an outlier? Lancet. 2001;358:181–187. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05404-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Steiner SH, Cook RJ, Farewell VT, Treasure T. Monitoring surgical performance using risk-adjusted cumulative sum charts. Biostatistics. 2000;1:441–452. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/1.4.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dovey SM, Meyers DS, Phillips RL, Jr, Green LA, Fryer GE, Galliher JM, et al. A preliminary taxonomy of medical errors in family practice. Qual Saf Health Care. 2002;11:233–238. doi: 10.1136/qhc.11.3.233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wolff AM, Bourke J, Campbell IA, Leembruggen DW. Detecting and reducing hospital adverse events: outcomes of the Wimmera clinical risk management program. Med J Aust. 2001;174:621–625. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2001.tb143469.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khunti K. A method of creating a death register for general practice. BMJ. 1996;312:952. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7036.952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holden J, Tutham D. Place of death of 714 patients in a north west general practice 1992-2000: an indicator of quality? J Clin Excellence. 2001;3:33–35. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holden, O'Donnell S, Brindley J, Miles L. Analysis of 1263 deaths in four general practices. Brit J Gen Pract. 1998;48:1409–1412. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stacey R, Robinson L, Bhopal R, Spencer J. Evaluation of death registers in general practice. Br J Gen Pract. 1998;48:1739–1741. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robinson LA, Stacy R, Spencer JA, Bhopal R. How to do it: use facilitated case discussions for significant event auditing. BMJ. 1995;311:315–318. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7000.315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Payne JN, Milner PC, Saul C, Browns IR, Hannay DR, Ramsay LE. Local confidential inquiry into avoidable factors in deaths from stroke and hypertensive disease. BMJ. 1993;307:1027–1030. doi: 10.1136/bmj.307.6911.1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hermoni D, Nijim Y, Spencer T. Preventable deaths: 16 year study of consecutive deaths in a village in Israel. Br J Gen Pract. 1992;42:521–523. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hart J T, Thomas C, Gibbons B, Edwards C, Hart M, Jones J, et al. Twenty five years of case finding and audit in a socially deprived community. BMJ. 1991;302:1509–1513. doi: 10.1136/bmj.302.6791.1509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]