Abstract

With the paucity of data available regarding COVID-19 in pregnancy in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), near the start of the pandemic, the Global Network for Women’s and Children’s Health Research, funded by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), initiated four separate studies to better understand the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in eight LMIC sites. These sites included: four in Asia, in Bangladesh, India (two sites) and Pakistan; three in Africa, in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Kenya and Zambia; and one in Central America, in Guatemala. The first study evaluated changes in health service utilisation; the second study evaluated knowledge, attitudes and practices of pregnant women in relationship to COVID-19 in pregnancy; the third study evaluated knowledge, attitude and practices related to COVID-19 vaccination in pregnancy; and the fourth study, using antibody status at delivery, evaluated changes in antibody status over time in each of the sites and the relationship of antibody positivity with various pregnancy outcomes. Across the Global Network, in the first year of the study there was little reduction in health care utilisation and no apparent change in pregnancy outcomes. Knowledge related to COVID-19 was highly variable across the sites but was generally poor. Vaccination rates among pregnant women in the Global Network were very low, and were considerably lower than the vaccination rates reported for the countries as a whole. Knowledge regarding vaccines was generally poor and varied widely. Most women did not believe the vaccines were safe or effective, but slightly more than half would accept the vaccine if offered. Based on antibody positivity, the rates of COVID-19 infection increased substantially in each of the sites over the course of the pandemic. Most pregnancy outcomes were not worse in women who were infected with COVID-19 during their pregnancies. We interpret the absence of an increase in adverse outcomes in women infected with COVID-19 to the fact that in the populations studied, most COVID-19 infections were either asymptomatic or were relatively mild.

Keywords: attitude, COVID-19, epidemiology, general obstetric, knowledge, low and middle income countries, practice, pregnancy, vaccination

1 |. INTRODUCTION

The first cases of COVID-19 appeared in late 2019 and the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the COVID-19 disease to be a global pandemic in March 2020.1 Although it soon became clear that COVID-19 infection could be associated with extensive morbidity and mortality, especially in the elderly and in those with various risk factors, it was not clear what the impact of COVID-19 infections was on pregnant women or on their pregnancy outcomes.2,3 It was also not clear whether the impact of COVID-19 on pregnant women and their pregnancies was the same in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) as in initial reports from high-income countries.

Initial reports of pregnancy outcomes in women with COVID-19 from high-income countries generally presented data from women who were antigen-positive by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and hospitalised; in these women, there was no question that morbidity and mortality for the women themselves was high.2 Reports on other adverse pregnancy outcomes were variable but several studies found increased incidences of stillbirth, neonatal mortality, preterm birth, pre-eclampsia and low birthweight. Furthermore, modelling exercises focused on LMICs, evaluating the potential impact of a reduction in health services as a result of COVID-19, suggested important increases in adverse outcomes linked to decreased health care utilisation for pregnant women.3 To better understand the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on pregnancy outcomes in LMICs, we undertook the Global Network COVID-19 studies described below.

2 |. METHODS

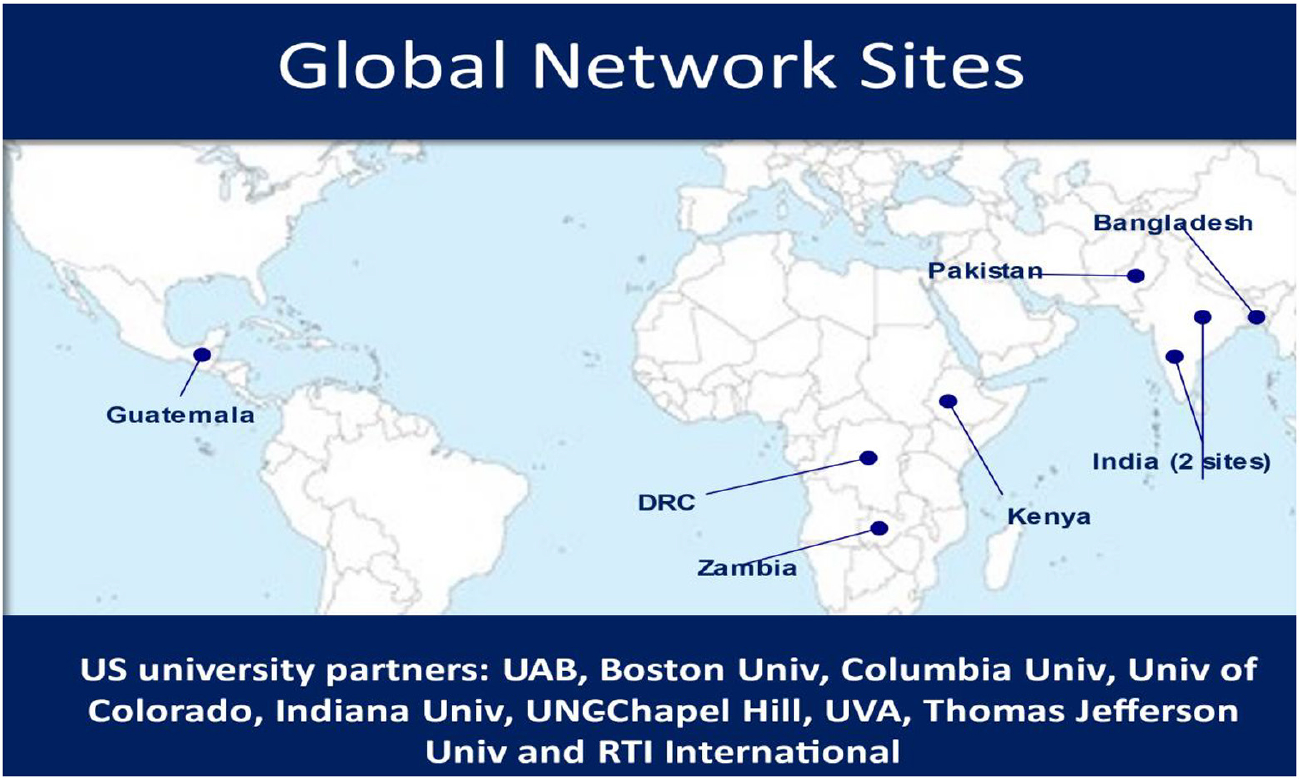

The Global Network for Women’s and Children’s Health Research (Global Network) is a multi-country, scientific and research capacity-building programme focused on pregnant women and children. Established in 2000 by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) it is currently operating in seven LMICs (Figure 1).4,5 In 2008, the Global Network established the Maternal Newborn Health Registry (MNHR) – a prospective, population-based registry aimed at providing statistics on pregnancy-related healthcare services and pregnancy outcomes. The MNHR provides population-based data on maternal and neonatal health outcomes such as preterm birth, fetal growth restriction, and maternal, fetal, and newborn mortality. The Global Network’s COVID-19 studies were initiated early in the pandemic, when limited data were available regarding the impact of COVID-19 on pregnant women and pregnancy outcomes in LMICs. We used this platform to collect data on knowledge, attitudes and practices (KAP) related to COVID-19, and also to collect data on KAP related to COVID-19 vaccination, and the use of healthcare services before and during the pandemic, and to collect a blood samples at delivery to determine maternal COVID-19 antibody status as a measure of prior infection.

FIGURE 1.

Global Network map.

3 |. RESULTS

We divided the Global Network’s COVID-19 work into four separate studies. The first evaluated the indirect impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on some healthcare services and the impact on several pregnancy outcomes.6 The first observation was that although there were small reductions in physician deliveries in the first year of the pandemic, we could demonstrate no impact on any pregnancy-related health outcomes. Specifically, during the COVID-19 period, in the Global Network sites, there were no increases in stillbirths or neonatal deaths, and no increases in preterm or low-birthweight births.

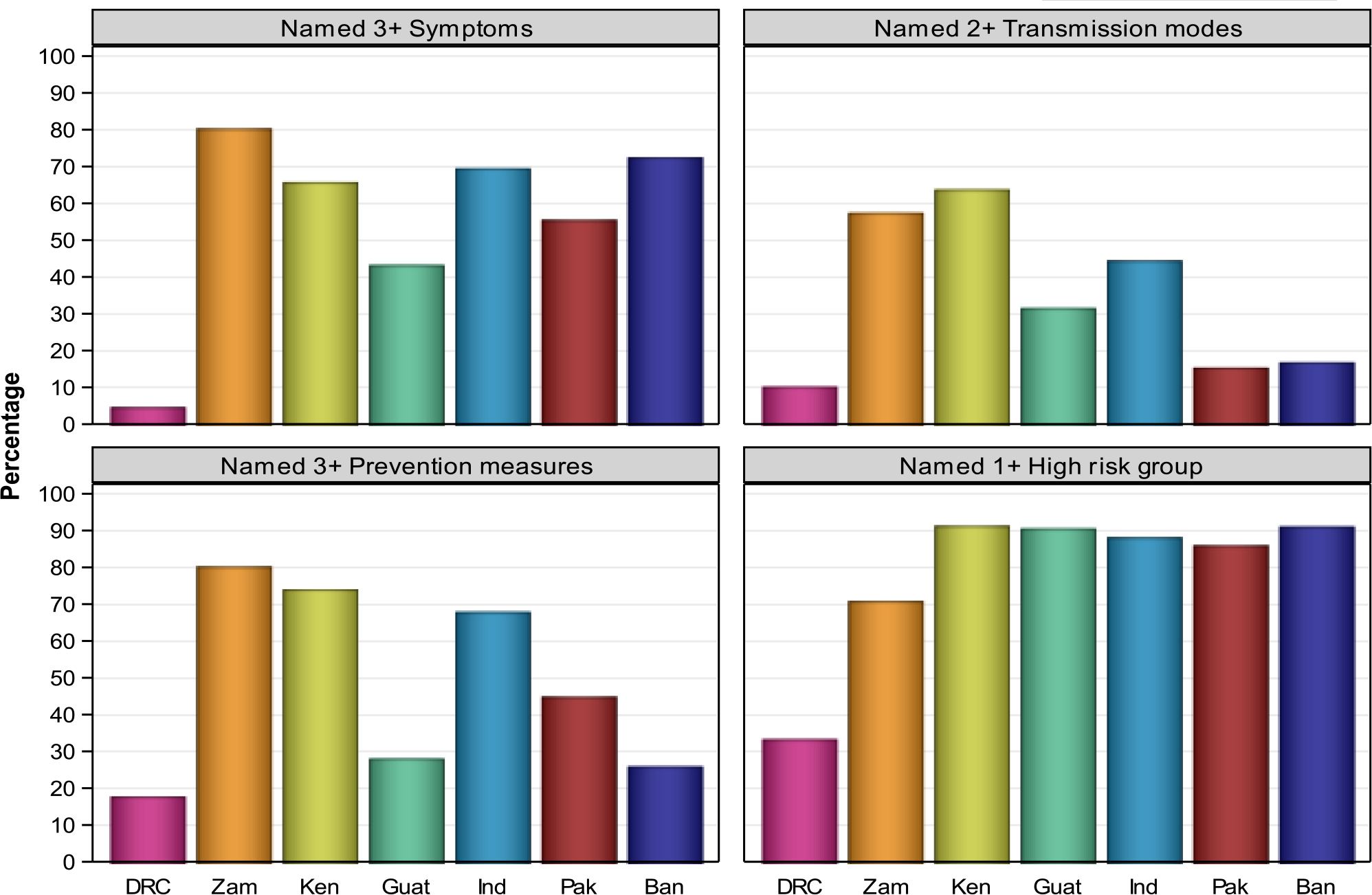

Our second study focused on pregnant women’s KAP related to COVID-19.7 These data were collected using a survey constructed for this purpose. Knowledge was assessed by asking participants to identify specific symptoms of COVID-19 infection, methods of transmission, measures to prevent the spread of COVID-19 and knowledge of the highest risk groups. Attitudes towards the disease were assessed with questions related to avoidance of antenatal care (ANC) visits and institutional delivery. Practices were assessed by exploring the measures that pregnant women adopted to contain the spread of COVID-19.

Key findings from this study showed that women in the Global Network sites had variable and generally low levels of knowledge related to COVID-19. Across all the sites, only 56.8% of women could name three or more COVID-19 symptoms, only 34.3% knew two or more transmission modes, 51.3% knew three or more preventive measures and 79.7% named at least one high-risk condition. As a result of COVID-19 exposure concerns, 23.8% of pregnant women said they avoided prenatal care visits, 7.5% planned to avoid hospitals; 24% were afraid to get infected with COVID-19 by their healthcare providers (Figure 2). Pregnant women in Guatemala were more likely to reduce healthcare-seeking behaviour because of COVID-19, compared with the other Global Networks sites. Although variable among the sites, overall, 29.1% of pregnant women planned to stay at home and 63.3% planned to wear a facemask to protect themselves against COVID-19. Our major observation is that there were very large differences in KAP related to COVID-19 among the sites, and overall the knowledge regarding COVID-19 was generally low.

FIGURE 2.

Knowledge of COVID-19 symptoms, modes of transmission, measures to reduce transmission and high-risk groups, by site.

Our third study evaluated a number of factors related to COVID-19 vaccination.8 We observed large variations in KAP concerning COVID-19 vaccination among the sites. Overall, only half the pregnant women believed the COVID-19 vaccine to be very or somewhat effective, 31.4% believed the COVID-19 vaccine to be safe for women trying to get pregnant and only 22.8% believed the COVID-19 vaccine to be safe for pregnant women (Tables 1 and 2). Nevertheless, 56% of the women surveyed said that they would get the vaccine if available. The main reasons for vaccine hesitancy among pregnant women were related to vaccine safety (30.6%), adverse side effects (25.1%) and a lack of trust (25.0%). Guatemalan women were more likely and Pakistani women were less likely to get vaccinated. In most sites, uneducated women were less likely to get vaccinated. Women would turn to family members and health professionals to seek COVID-19 vaccination-related advice. Most pregnant women at each site were unvaccinated, and rates for pregnant women were considerably lower than the overall country rates for adults (Table 3). We considered whether the lack of vaccine use among pregnant women, especially in Africa, was related to vaccine hesitancy or simply the non-availability of vaccinations as a result of inadequate supply, poor supply distribution or a lack of trained personnel.9 Research is currently underway to attempt to better understand these issues.

TABLE 1.

COVID-19 vaccination: women’s beliefs about effectiveness.

| All | DRC | Zambia | Kenya | Guatemala | India | Pakistan | Bangladesh | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women, n | 13 094 | 308 | 2477 | 2147 | 990 | 2782 | 2115 | 2275 |

| Very or somewhat effective | 50% | 29% | 75% | 37% | 58% | 72% | 40% | 22% |

| Not effective | 13% | 3% | 9% | 17% | 19% | 3% | 34% | 3% |

| Do not know | 37% | 69% | 16% | 47% | 23% | 25% | 26% | 75% |

TABLE 2.

COVID-19 vaccination: women’s beliefs about safety in pregnancy.

| All | DRC | Zambia | Kenya | Guatemala | India | Pakistan | Bangladesh | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women, n | 13 094 | 308 | 2477 | 2147 | 990 | 2782 | 2115 | 2275 |

| Safe if pregnant | 22% | 30% | 37% | 12% | 29% | 35% | 15% | 6% |

| Safe if trying to become pregnant | 31% | 53% | 53% | 24% | 36% | 44% | 16% | 11% |

| Willing to get vaccine | 56% | 47% | 71% | 49% | 50% | 80% | 28% | 51% |

TABLE 3.

Women vaccinated for COVID-19 before delivery (March 2021–January 2022) compared with overall country rates.

| Site | Country vaccine rates (WHO) | COVID-19 vaccination among pregnant women (Global Network) |

|---|---|---|

| DRC | 12% | 0% |

| Zambia | 16% | 0.3% |

| Kenya | 22% | 0% |

| Guatemala | 46% | 16.6% |

| Bangladesh | 78% | 0% |

| Pakistan | 59% | 0% |

| India | 72% | 19.2% |

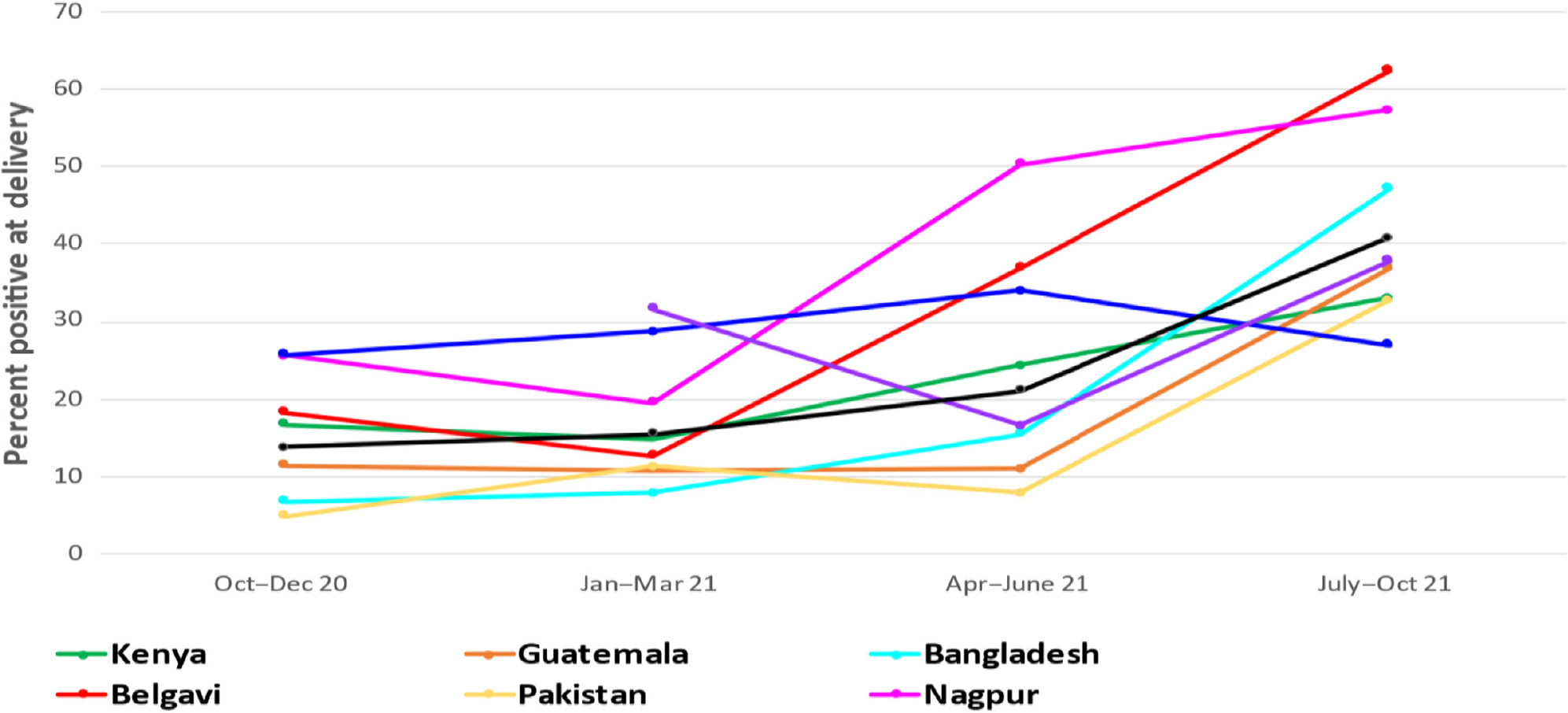

In our fourth study, to estimate the overall scope of COVID-19 disease in pregnant women, we implemented COVID-19 antibody screening at the time of delivery.10 Our first observation was that the percentage of women testing positive increased substantially over time at all sites. For this study, we divided the study time into four periods, starting from October 2020 to October 2021. Overall, across all sites, the percentage of women testing positive at the time of delivery increased from 17% to 40% (Figure 3). In the last time period, there were substantial differences in positivity rates across sites. In all sites, over time, a greater proportion of the women delivering became COVID-19 antibody positive. A greater proportion of women in India compared with the other sites tested positive.

FIGURE 3.

COVID-19 antibody positivity at delivery over time, by site.

An important finding was related to the association of a positive test with clinical outcomes. Table 4 shows that with the possible exception of postpartum haemorrhage, no other adverse outcome was increased in women who were antibody-positive. In the article, sensitivity analyses were performed to account for women who may have been infected prior to pregnancy or were vaccinated.10

TABLE 4.

COVID positivity and risk of adverse maternal and fetal/neonatal outcomes.

| Overall % | Positive % | Negative % | Adjusted RR (95% CI) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal outcomes | |||||

| Maternal deaths <42 days (per 100 000) | 22 | 27 | 20 | – | – |

| Hypertensive disease/pre-eclampsia/eclampsia | 2.1 | 2.1 | 2.2 | 0.96 (0.73–1.26) | 0.7690 |

| APH | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 1.15 (0.70–1.87) | 0.5864 |

| PPH | 1.0 | 1.2 | 1.0 | 1.44 (1.01–2.07) | 0.0457 |

| Fetal/neonatal outcomes | |||||

| Stillbirths (per 1000) | 18.3 | 18.9 | 18.0 | 1.27 (0.95–1.69) | 0.1022 |

| Preterm births | 15.7 | 15.2 | 15.9 | 1.03 (0.93–1.14) | 0.5504 |

| Low birthweight | 17.0 | 17.7 | 16.8 | 1.09 (0.99–1.19) | 0.0872 |

| Neonatal deaths <28 days (per 1000) | 17.6 | 16.6 | 18.0 | 1.11 (0.82–1.50) | 0.5045 |

Abbreviations: APH, antepartum haemorrhage; PPH, postpartum haemorrhage.

4 |. INTERPRETATION

From the Global Network COVID-19 studies, a number of conclusions can be drawn. The first is that knowledge regarding COVID-19 was generally low and was highly variable among the sites. Over the course of the pandemic, there were few substantial changes in pregnant women’s knowledge related to COVID-19. Knowledge related to vaccine use was also low. Most women claimed to have little knowledge about efficacy or safety related to COVID-19 vaccines. Only 58% would accept a vaccine if offered. We compared rates of vaccination in pregnant women in each site with the reported country vaccination rates, and in each site there were stark differences. We expect that these differences are the result of a number of factors, with regards to demand and vaccine availability. For example, on the demand side, factors such as vaccine hesitancy, concerns about vaccine safety and effectiveness, as well as cultural/religious-related barriers might explain some of the low vaccination rates. On the vaccine supply side, issues such as the non-availability of vaccines, distribution problems and a lack of trained personnel are likely to explain some of the low rates.9,11

Knowledge about COVID-19 vaccination is limited and highly variable among pregnant women at the Global Network sites. Addressing vaccine safety and effectiveness among pregnant women is important for educational efforts to increase vaccination rates. There appears to be a need for tailored health literacy intervention programmes targeted not only at the pregnant women but also their families and health professionals in the community, as they are identified by pregnant women as the main source of vaccine-related information.11 Furthermore, it is important to include pregnant women in the early stages of vaccine trials and vaccination roll-outs.

The health impact of COVID-19 may be linked either to indirect effects of decreased healthcare utilisation or direct effects resulting from infection. We believe that at least part of the difference between the results of the Global Network studies and earlier reports is explained by the populations studied and the methods by which a COVID-19 infection was diagnosed. Antigen positivity implies a current infection, with the testing generally performed because of maternal symptoms. Antibody positivity implies prior infection, whether the testing was performed because of symptoms or not. In the Global Network study, the blood for antibody testing was collected from women at delivery, the vast majority of whom were asymptomatic. We believe that our results are therefore quite different than results from a symptomatic population and can be interpreted in the following way. Most women who become infected with COVID-19 are asymptomatic. Of those who become symptomatic, most do not become seriously ill and do not have an adverse pregnancy outcome. The adverse outcomes generally reported are mostly confined to women who were hospitalised with severe disease. Thus, it is crucial to distinguish whether the study on COVID-19 outcomes was based on antibody positivity or the presence of COVID-19 antigens, and whether it focused on mostly asymptomatic women or on severely ill and hospitalised women.10

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the leadership of the clinical sites and the subjects at each site who participated in these studies.

Funding information

Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

ETHICAL APPROVALS

The study protocol was approved by respective ethical review committees of participating institutions from India and Pakistan and the United States. All procedures were conducted per hospital protocol following receipt of informed written consent.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study will be available from the NICHD data & specimen hub (https://dash.nichd.nih.gov/).

REFERENCES

- 1.Cucinotta D, Vanelli M. WHO declares COVID-19 a pandemic. Acta Biomed. 2020;91(1):157–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Villar J, Ariff S, Gunier RB, Thiruvengadam R, Rauch S, Kholin A, et al. Maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality among pregnant women with and without COVID-19 infection: the INTERCOVID multinational cohort study. JAMA Pediatr. 2021;175:817–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roberton T, Carter ED, Chou VB, Stegmuller AR, Jackson BD, Tam Y, et al. Early estimates of the indirect effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on maternal and child mortality in low-income and middle-income countries: a modelling study. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8:e901–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koso-Thomas M, McClure EM. The Global Network for Women’s and Children’s Health Research: a model of capacity-building research. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2015;20:293–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McClure EM, Garces A, Hibberd PL, Moore J, MacGuire ER, Goudar SS, et al. The Global Network Maternal Newborn Health Registry: a multi-national, community-based registry of pregnancy outcomes. Reprod Health. 2020;17(Suppl 2):184. 10.1186/s12978-020-01020-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Naqvi S, Naqvi F, Saleem S, Thorsten VR, Figueroa L, Mazariegos M, et al. Health care in pregnancy during the COVID-19 pandemic and pregnancy outcomes in six low-and-middle-income countries: evidence from a prospective, observational registry of the Global Network for Women’s and Children’s Health. BJOG. 2022;129:1298–1307. 10.1111/1471-0528.17175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Naqvi F, Naqvi S, Billah SM, Saleem S, Fogleman E, Peres-da-Silva N, et al. Knowledge, attitude and practices of pregnant women related to COVID-19 infection: a cross-sectional survey in seven countries from the Global Network for Women’s and Children’s Health. BJOG. 2022;129:1289–97. 10.1111/1471-0528.17122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Naqvi S, Saleem S, Naqvi F, Sk Billah M, Nielsen E, Fogleman E, et al. Knowledge, attitudes and practices of pregnant women regarding COVID-19 vaccination in pregnancy in 7 low and middle-income countries: an observational trial from the Global Network. BJOG. 2022;129(12):2002–9. 10.1111/1471-0528.17226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goldenberg RL, Naqvi S, Saleem S, McClure EM. Variability in COVID-19 vaccination rates in pregnant women: vaccine hesitancy or supply limitations? BJOG. 2022;129:2095–6. 10.1111/1471-0528.17257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goldenberg RL, Saleem S, Billah SM, Kim J, Moore JL, Ghanchi NK, et al. COVID-19 antibody positivity over time and pregnancy outcomes in seven low-and-middle-income countries: a prospective, observational study of the Global Network for Women’s and Children’s Health Research. BJOG. 2022;130:366–76. 10.1111/1471-0528.17366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tagoe ET, Sheikh N, Morton A, Nonvignon J, Sarker AR, Williams L, et al. COVID-19 vaccination in lower-middle income countries: national stakeholder views on challenges, barriers, and potential solutions. Front Public Health. 2021;9:709127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study will be available from the NICHD data & specimen hub (https://dash.nichd.nih.gov/).