Abstract

Introduction:

HIV preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is highly effective when taken as prescribed. Digital health adherence interventions have been identified as effective for improving antiretroviral therapy adherence among people with HIV, but limited evidence exists for PrEP adherence interventions among people without HIV. The purpose of this Community Guide systematic review was to present the characteristics and effectiveness of digital PrEP adherence interventions.

Methods:

The author searched the CDC HIV Prevention Research Synthesis cumulative database for digital health interventions with PrEP adherence outcomes published in peer-reviewed journals from 2000-2022. Studies with comparison arms or pre-post data evaluating interventions in high-income countries were included. Two reviewers independently screened citations, extracted data, conducted risk of bias assessment, and resolved discrepancies through discussion. Summary effect estimates were calculated using median and interquartile interval.

Results:

Nine studies were included and all focused on gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men. Eight studies were U.S.-based while the other was conducted in the Netherlands. Five were randomized control trials and four were pre-/post studies. All studies showed improved adherence in the intervention arms compared with comparison groups or pre-intervention data. One study also reported improvement in PrEP care retention.

Discussion:

Digital health adherence interventions with different strategies to improve PrEP and HIV-related outcomes were identified. The small number of studies identified is a limitation. Findings from this review served as the basis for the Community Preventive Services Task Force recommendation to use these interventions to increase PrEP adherence to prevent HIV infection.

Introduction

Ending the HIV Epidemic in the U.S. (EHE) is the operational plan developed by agencies across the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) to pursue the goal to reduce new HIV infections by 75% by 2025 and 90% by 2030.1 DHSS identified four key strategies to achieve these goals in the United States, including 1) diagnosing people with HIV as early as possible after infection, 2) treat people with HIV rapidly and effectively to reach sustained viral suppression, 3) prevent new HIV transmission through evidence-based interventions including pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) and syringe services programs (SSPs), and 4) respond quickly to potential HIV outbreaks to get prevention and treatment services to people who need them. The National HIV/AIDS Strategy (2022-2025) is closely aligned with and complements the EHE.2 The national strategy encourages collaboration between all sectors of society to prevent new HIV infections, improve health outcomes of people with HIV, and reduce HIV-related disparities and health inequities.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends clinicians offer PrEP to persons who are at high risk for HIV acquisition.3 When taken daily as prescribed, PrEP reduces the risk of getting HIV from sex by 99% and from injection drug use by at least 74%.4 There is a strong connection between adherence to PrEP and its effectiveness in preventing HIV acquisition; reduced adherence is associated with a decline in effectiveness.4–6 The CDC Prevention Research Synthesis (PRS) Project has been closely following the research on PrEP use and adherence to identify Best Practices (i.e., evidence-based, evidence-informed interventions)7. The CDC PRS Project collaborated with the Community Guide Program (CGP; ”Community Guide”) to provide evidence for the Community Preventive Services Task Force (CPSTF) to make a recommendation. CPSTF was established by DHHS to complement the work of the USPSTF, and the recommendations by CPSTF are considered to be the gold standard for what works to protect and improve population health.9 CGP provides administrative, scientific, and technical support for CPSTF.8 Results from the systematic review was the basis for the CPSTF’s recommendation for digital health interventions to increase adherence to PrEP.10

A digital health intervention is an umbrella term that covers all technology meant to improve patient outcomes and uses text messages, mobile applications (apps), phone calls, or websites to deliver reminders, guidance, and support that may be tailored to an individual’s needs. Digital health interventions have been identified as effective for improving HIV care among people with HIV.11 Digital interventions provide one or more of the following:

Information about HIV, PrEP, and strategies for being in care and persistence.

Services such as automated or interactive feedback, online forum discussions, virtual support groups, or adherence tracking intended to motivate participants.

Regular reminders for medications, virtual check-in appointments, and clinic visits.

Digital interventions may be combined with in-person activities such as one-on-one counseling, peer-led group sessions, or patient navigation.

Methods

Community Guide methods were used to conduct this systematic review.12–14 In brief, the methods include the steps of 1) forming multidisciplinary chapter development teams, 2) developing a conceptual approach to organizing, grouping, selecting and evaluating the interventions; 3) selecting interventions to be evaluated; 4) searching for and retrieving evidence; 5) assessing the quality of and summarizing the body of evidence of effectiveness; 6) translating the body of evidence of effectiveness into recommendations; 7) considering information on evidence other than effectiveness; and 8) identifying and summarizing research gaps. PRS librarians conducted a digital health and PrEP search query in the CDC PRS Project database, a cumulative HIV database created using search results from ongoing targeted comprehensive literature searches that include a PrEP focused literature search.15 The PrEP search is run in the databases (platforms) MEDLINE (OVID), EMBASE (OVID), PsycINFO (OVID, and CINAHL (EBSCOhost), supplemented by additional hand searches (e.g., journals, reference list checks). A PRS trained coder screens each citation by title and abstract to identify articles published in English that report PrEP-related behavioral (e.g., behaviors or behavioral intentions related to PrEP uptake) or biologic (e.g., any aspect of the use or effects of a PrEP medication for HIV prevention) outcomes and assigns a “PrEP” code to the article. Next, a pair of the PRS trained coders independently screen the full text of these PrEP articles to identify those reporting PrEP adherence outcomes (i.e., any subset or grouping based on PrEP adherence) and assign the code “PrEP adherence”. 16,17 The coders meet to discuss and reconcile coding discrepancies. If coders could not reach consensus, a third PRS team member was consulted. Articles with keywords “PrEP” and “PrEP adherence” were identified from the PRS Project database and were eligible for inclusion in the systematic review. Eligible articles published 2000 – 2022 were identified in June 2021 with an update in May 2023 by using the same search query. A detailed search strategy is available from the Community Guide website.10

Primary studies (e.g., research studies that included data gathered and analyzed by the authors) published in a peer-reviewed journal were included if they 1) evaluated digital health interventions to improve PrEP adherence, 2) reported PrEP adherence, 3) had comparison arms or pre-post data 4) were conducted in a country with a high-income economy18, and 5) were written in English. Commentaries, reviews, and non-peer-reviewed publications were not eligible for this review.

Three team members who were authors for this review and had extensive systematic review experience were trained to code studies specific for this review. They independently screened potential publications for inclusion and abstracted information from included studies. Coding pairs assessed included studies on their quality of execution using an established set of criteria.12–14 The tool addressed threats to internal and external validity and included six domains with nine possible limitations for each study.12–14 These domains are: description of the intervention and population (0-1 limitation); description of the sampling process (0-1); validity and reliability of the intervention exposure and measurement (0-2); description and use of appropriate analytic methods (0-1); interpretations of results including attrition (i.e., whether more than 20% of study participants was lost to follow-up), confounding and potential bias (0-3); and other (0-1). Studies were classified as having good (0–1 limitations), fair (2–4), or limited (>4) quality of execution. Studies with limited quality of execution were excluded from the analyses.12,13 Discrepancies between coder pairs were reconciled via discussion and, if needed, a senior coder was consulted. All screening and data abstract forms were pilot tested and revised as necessary.

The primary outcome of interest was daily PrEP adherence while HIV incidence and HIV-related morbidity (i.e., the state of being symptomatic or unhealthy for a disease or condition) and mortality (i.e., the number of deaths caused by the health event under investigation) were secondary outcomes.19 PrEP adherence was assessed using “excellent adherence”, defined as taking seven doses of PrEP per week, “good adherence”, defined as taking four or more doses of PrEP per week, or “poor adherence”, defined as less than four doses per week.20 For summary measures, medians and interquartile intervals (IQI) were calculated. Studies that performed stratified analysis based on different intervention or demographic characteristics were narratively summarized.

Results

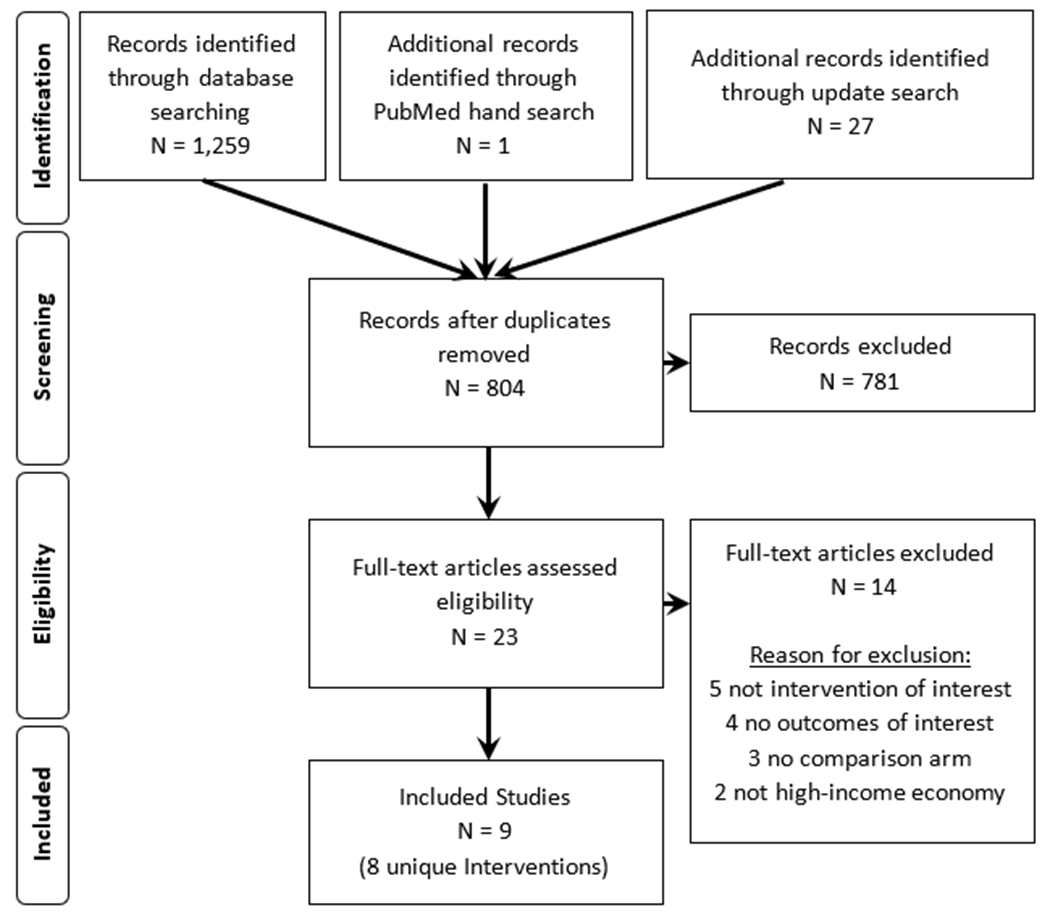

This review found 1,260 citations (1,259 citations in the PRS database and 1 citation through the PubMed hand search) with the initial search and 27 from the updated search. Overall, the authors screened 23 full texts. Of these, 14 studies did not meet the study criteria. Thus, this review included nine21–29 studies evaluating eight unique interventions (Figure 1). These nine intervention studies are:

Figure 1:

PRISMA flowchart

DOT29, a culturally- and youth-tailored app that sent pill reminders and educational texts,

Enhanced AMPrEP 21 a mobile app plus visualized feedback,

enPrEP22 that sent automated weekly text message reminders with an online support group,

iTAB23 that sent daily and customized text messages via a mobile app,

iTEXT24 that sent weekly bidirectional text or email messages via a mobile app,

PrEPmate26 that provided daily at customized time text messages and youth-tailored interactive online support groups, and

ViralCombat27, a gaming adherence intervention.

Details about the included studies are available on the Community Guide website.30

Five21–23,26,27 studies were individual randomized controlled trials (iRCTs) and four24,25,28,29 used pre-post only design. Studies evaluating enhanced AMPrEP21, iTAB23, PrEPmate26, and mSMART among African American MSM28 had good quality of execution; the remaining studies22,24,25,27,29 had fair quality of execution. The commonly assigned limitations were unclear sampling process24–26,28,29, use of self-reported data or outcome measures without validation22,24,29, and high attrition21,22,27.

Most of included studies are U.S.-based (n=8)22–29, but Enhanced AMPrEP21 is from the Netherlands. Sample sizes were 10 to 398, and all the U.S. studies were implemented in urban areas and covered all four regions as defined by the U.S. Census Bureau, with iTAB23 in the West, PrEPmate26 in the Midwest, mSMART25,28 and ViralCombat27 in the South, DOT29 and enPrEP22 in the Northeast, and iTEXT24 in both Midwest and West regions.

The included studies provided various digital health services and communicated with participants using different methods at varied frequencies. The digital health services included medication reminders for daily PrEP use (n=7)21–23,25,26,28,29, information and education (n=5)22,23,26,27,29, adherence tracking (n=4)21,25,28,29, support groups (n=2)22,26, and counseling (n=1).23 These services were delivered through a digital app only (n=3)21,25,28, an app plus text messaging (n=2)27,29, text messaging only (n=1)23, or text messaging plus email, phone, or internet (n=3)22,24,26. Study participants received digital communications at least daily (n=5)23,25,26,28,29, weekly (n=3)22,24,27, or monthly (n=1).21 These communications could be unidirectional where pre-set messages were sent to the participants (n=3),21–23 bidirectional with automated messages where participants’ questions were answered by pre-set messages (n=5),24–26,28,29 or bidirectional with personalized messages where participants’ questions were answered by live support (n=2).24,26

In addition to the digital health services, enPrEP22 provided an in-person support group. ViralCombat27 provided smartphones to study participants while other interventions required participants to have a smartphone and data plan. None of the studies provided information about the languages used for communications, though PrEPmate26 and ViralCombat27 recruited only English speaking participants while iTAB23 included both English- and Spanish-speakers.

All studies used standard forms saved in a central cloud location to collect data, obtain lab work, and provide information or instructions to participants. The median for intervention duration was nine months, with five studies24,25,27–29 lasting six months or less and four studies21–23,26 lasting longer than six months.

In terms of demographic characteristics of participants in included studies, six studies23,25–29 reported the mean age of participants; the median was 25 years. Two studies reported median ages of 3921 and 4924 years, and the remaining study22 did not report age.

Most participants were male (median of 99%). Five studies24,25,27–29 only recruited male participants. Four recruited transgender women and they accounted for a median of 3% of participants.21–23,26 All studies focused on MSM.

All studies conducted in the United States (n=822–29) reported racial or ethnic distributions. Participants were White (median of 60%, n=623–26,28,29), Black or African American (median of 23%, n=822–29), Hispanic or Latino (median 11%, n=722–27,29), or Asian American (median of 5%, n=523,25,26,28,29). Study participants were demographically similar to the U.S. general population. EnPrEP22 and one of mSMART28 studies recruited only Black or African American participants and showed the intervention to be effective in increasing PrEP adherence. No study analyzed whether intervention effectiveness varied based on race or ethnicity.

All studies reported at least one measure of socioeconomic status. A median 81% of participants were employed full time or part-time (n=621,22,25,26,28,29); the remaining three studies23,24,27 did not report employment status. In two studies, the majority of participants had an annual income less than $20K (59%26, 66%22). Three studies21,23,25 reported a median of 22% of participants who had an annual income less than $24-25K. Four studies24,27–29 did not report income. Eight studies22–29 reported a median of 89% of participants who completed some college or more. Most participants were insured (78%26 and 100%21, n=2), covered by Medicaid or Medicare (64%22 and 90%27, n=2), or paid for healthcare through private insurance or self-pay (19%, n=122). One study27 reported that just under 50% of participants were receiving PrEP payment assistance. Five studies23–25,28,29 did not report insurance status.

Four studies assessed participants’ drug use history using questionnaires such as the Drug Abuse Screening Test31 and reported no or low (63%23 and 100%25) or excessive substance use (median of 37%, n=321–23). In two studies, the majority of participants reported they engaged in “any” recreational substance use (64%26 and 72%23, n=2). Of four studies that reported alcohol use, study participants reported low alcohol use (100%, n=125) or excessive alcohol use (median of 29%, n=321,22,26). Additionally, three studies reported on mental health issues and showed a median of 13% of study participants reporting mild depression, depression, or anxiety symptoms (n=3).21,22,25

In terms of changes in PrEP adherence, all studies showed participants receiving interventions had greater improvement on adherence (e.g., self-reported, dried blood spot) and higher adherence compared with comparisons (e.g., standard of care, no intervention, in-person adherence counseling) (Table 1). Most studies reported “good adherence” only21,25,26 or “excellent adherence”.23,25,27 When evaluated against comparisons, a higher proportion of intervention participants achieved good adherence (median of 13.0 percentage points higher; Interquartile Interval (IQI): 6.4-25.3 percentage points; n=621,23,25–28) or excellent adherence (median of 16.8 percentage points higher; IQI: 12.7-26.7 percentage points; n=423,25,27,29). ITEXT24 provided weekly bidirectional personalized texts or email reminders for pill taking and reported that the post-intervention group missed statistically significant fewer PrEP doses when compared to the pre-intervention group (Relative Risk 0.50; 95% Confidence Interval [CI] 0.29-0.84).

Table 1.

Effectiveness of Digital Health Interventions to Increase PrEP Adherence

| Outcome Measure | Number of Studies | Effect Sizes |

|---|---|---|

| Good adherencea | 6 | Absolute difference: Median: 13.0 pct pts (IQId: 6.4 - 25.3 pct ptse) |

| Relative difference: Median: 19.3% (IQId: 9.0 - 40.0%) | ||

| Excellent adherenceb | 4 | Absolute difference: Median: 16.8 pct pts (IQId: 12.7 - 26.7 pct ptse) |

| Relative difference: Median: 75.5% (IQId: 12.7 - 26.7%) | ||

| Retentionc | 1 | ORf: 2.62 (95% CI 1.24 - 5.54; p=0.01) |

Note: Boldface indicates statistical significance (p<0.05)

Good adherence: consistent with four or more doses of PrEP per week

Excellent adherence: consistent with 7 doses of PrEP per week

Retention: proportion of participants making all clinical visits

IQI: interquartile interval

Pct pts: percentage points

OR: odds ratio

The intervention group in Enhanced AMPrEP21 received visualized feedback in the app while the comparison group only received text messages. More participants in the intervention group achieved excellent adherence (Odds Ratio [OR] 2.0, 95% CI 1.1-3.8; p = 0.026) but the number of participants with “poor adherence” didn’t change (OR 1.5, 95% CI 0.61-3.8; p = 0.36). The authors also found poor adherence was associated with symptoms of depression or anxiety (OR 3.2, 95% CI 1.1-9.5) and low concern of acquiring HIV (OR 4.3, 95% CI 1.6-12).

iTAB23, PrEPmate26, and ViralCombat27 intervened throughout the follow-up periods and examined intervention effects over time. While all three studies found effects diminishing over time (duration of 3 to 12 months), iTAB23 and ViralCombat27 reported higher adherence in the intervention groups when compared with the control groups over time.

There is no evidence/report from the included studies that intervention effectiveness differed by interventions or participants’ characteristics including age, socioeconomic status, or drug use history.

In terms of HIV incidence and HIV-related morbidity and mortatlity, iTAB23 and PrEPmate26 studies reported HIV incidence. PrEPmate26 reported no HIV seroconversions in either the intervention or comparison groups. iTAB23 reported two HIV seroconversions in the intervention group among patients who discontinued PrEP. None of included studies reported HIV-related morbidity or mortality outcomes.

Other intervention benefits include that PrEPmate26 found that a significantly larger proportion of PrEP care visits were completed by participants in the intervention group compared with those in the comparison group (OR 2.62, 95% CI 1.24-5.54; p=0.01).

DOT29, enPrEP22, and PrEPmate26 identified a reduction in sexual risk behaviors as an additional benefit of these interventions. Studies reported decreases in the mean number of anal sex partners and the proportion of study participants who reported condomless anal sex. The studies also found lower proportions of participants with a diagnosed sexually transmitted infection (STI) at follow-up. Reductions were similar for both intervention and control groups.

Although the majority of studies did not assess acceptability of the intervention, in the few studies25,29 that did, digital interventions to improve adherence to daily-use HIV PrEP were highly acceptable. Of the services offered, study participants were most likely to use daily pill reminders and weekly check-ins.22,24–27

Discussion

This systematic review found that digital PrEP adherence interventions improved both daily-use pill taking and retention in PrEP care, thereby improving health for population groups which are at risk for HIV infection. Findings from this review served as the basis for the CPSTF’s recommendation to use these interventions to increase PrEP adherence to prevent HIV infection.10

Based on the CDC’s PrEP clinical practice guideline, clinical visits every three months are recommended for daily PrEP users to receive HIV testing, medication adherence counseling, behavioral risk reduction support, side effect assessment, STI symptom assessment, and renal function and bacterial STI testing.32 This review found that some of these strategies including counseling and behavioral risk reduction support can be provided by digital interventions between clinical visits.

Digital health may enhance care access for persons no matter where they live33 but it has technology and equipment requirements. Eight of the nine included studies only recruited participants who had smartphones and adequate data plans. In 2021, 85% of U.S. adults used a smartphone34, 77% had high-speed broadband service at home35, and 93% used the Internet35, suggesting digital interventions could be widely implemented. Inequalities of smartphone ownership have diminished by race or ethnicity, but still exists for Americans with lower incomes36, older adults, and people living in rural areas.37 In addition, even those who do own a smartphone may have pay-as-you-go type plans and face financial barriers to pay the cost of data and text messaging. It is important to consider participants’ income, age, and geographic location when implementing these interventions.

Most participants in the included studies were insured, but such coverage may not represent the general population in the U.S. Most insurance plans and state Medicaid programs cover the cost of PrEP.38 Other programs provide PrEP for free or at a reduced cost, such as Ready, Set, PrEP39 that provides medication at no cost to those who qualify, co-pay assistance programs40 that lower costs of PrEP medications, and state PrEP assistance programs41 that cover the costs for medication, clinical visits, and lab testing. Despite these programs, people who earn incomes that are too high for marketplace subsides or earn incomes below the federal poverty level in states that do not have expanded Medicaid may not be on PrEP due to the costs of PrEP medications and other costs including clinical visits and lab tests. Finally, the potential privacy risks, and need to ensure confidentiality and privacy are important to consider for digital health interventions. One of the included studies reported confidentiality concerns around receiving HIV-related text messages.22 The study used innocuous language such as “time to take vitamin pills” or “time to take mints” to replace HIV-specific language to help protect confidentiality.22 Digital health intervention materials also need to be compliant with Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) to protect privacy.42

Limitations

This review has several limitations. All studies focused on MSM; thus, the findings may not be applicable for other groups with risk factors for HIV infection such as people who share needles or equipment or people who exchange sex for money. This review also has a limited number of included studies and only included digital health interventions conducted in high-income countries, limiting its findings’ applicability to mid- and low-income countries. In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, use of digital health has been expanded, and more studies may be available in the next few years. Further reviews with more studies would help fill in the evidence gaps and increase understanding about the generalizability of the findings.

Conclusions

Based on the findings, CPSTF recommends digital health interventions to increase adherence to HIV PrEP based on sufficient evidence of effectiveness.20 These interventions improve both daily-use pill taking and retention in PrEP care, thereby potentially improving health for population groups not infected with HIV but at high risk for HIV infection.

Acknowledgments:

We acknowledge Theresa, Sipe1, PhD, MPH, MS, RN, and the following PrEP adherence review coordination team members: Priya Jakhmola3, MS, MBA, Camilla Harshbarger1, PhD, Dawn Smith1, MD, MPH, Katrina Hedberg3, MD, MPH, Doug Campos-Outcalt4, MD, MPA, Sarah Stoddard5, PhD, RN, CNP, FSAHM, FAAN, Matthew Hogben6, PhD, Jason Farley7, PhD, ANP-BC, FAAN, Michael Stirratt8, PhD, Jeffery Kwong9, DNP, MPH, FAANP, FAAN, Timothy W Menza10, MD, PhD, Patrick Sullivan11, DVM, PhD, Casey Messer12, DHSc, PA-C, AAHIVS.

Acknowledged PrEP adherence review coordination members’ Affiliations: 1Division of HIV Prevention, 6Division of Sexually Transmitted Disease Prevention, National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral hepatitis, STD, & TB Prevention; 3Public Health Science and Surveillance, Office of Science, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 4Oregon Health Authority; 3University of Arizona; 5University of Michigan; 7John Hopkins University; 8National Institute of Mental Health; 9American Association of Nursing Practitioners; 10Oregon State Health Department; 11Emory University; 12American Academy of Physician Assistants.

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

References

- 1.U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. What is Ending the HIV Epidemic in the U.S.? Accessed February 1, 2024. https://www.hiv.gov/federal-response/ending-the-hiv-epidemic/overview

- 2.U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. National HIV/AIDS Strategy (2022-2025). Updated December 1, 2023. Accessed Febryary 1, 2024. https://www.hiv.gov/federal-response/national-hiv-aids-strategy/national-hiv-aids-strategy-2022-2025

- 3.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Prevention of Acquisition of HIV: Preexposure Prophylaxis. Updated August 22, 2023. Accessed February 1, 2024. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/prevention-of-human-immunodeficiency-virus-hiv-infection-pre-exposure-prophylaxis

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. PrEP Effectiveness. Updated June 6, 2022. Accessed February 1, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/basics/prep/prep-effectiveness.html

- 5.Sidebottom D, Ekström AM, Strömdahl S. A systematic review of adherence to oral pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV - how can we improve uptake and adherence? BMC Infect Dis. Nov 16 2018;18(1):581. doi: 10.1186/s12879-018-3463-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dimitrov DT, Mâsse BR, Donnell D. PrEP adherence patterns strongly affect individual HIV risk and observed efficacy in randomized clinical trials. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. Aug 1 2016;72(4):444–51. doi: 10.1097/qai.0000000000000993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. PrEP Best Practices Criteria. Updated January 12, 2022. Accessed February 1, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/research/interventionresearch/compendium/prep/prep-best-practices.html

- 8.The Community Guide. About the Community Preventive Services Task Force. Updated June 22, 2023. Accessed February 1, 2024. https://thecommunityguide.org/pages/about-community-preventive-services-task-force.html

- 9.The Community Guide. About The Community Guide. Updated May 31, 2023. Accessed February 1, 2024. https://thecommunityguide.org/pages/about-community-guide.html

- 10.Guide to Community Preventive Services. HIV Prevention: Digital Health Interventions to Improve Adherence to HIV Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis. Updated October 11, 2022. Accessed February 1, 2024. https://www.thecommunityguide.org/findings/hiv-prevention-digital-health-interventions-improve-adherence-hiv-pre-exposure-prophylaxis.html.

- 11.Lester RT. Ask, Don’t tell — Mobile phones to improve HIV care. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(19):1867–1868. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1310509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Briss PA, Zaza S, Pappaioanou M, et al. Developing an evidence-based Guide to Community Preventive Services--methods. The Task Force on Community Preventive Services. Am J Prev Med. Jan 2000;18(1 Suppl):35–43. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(99)00119-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zaza S, Wright-De Agüero LK, Briss PA, et al. Data collection instrument and procedure for systematic reviews in the Guide to Community Preventive Services. Task Force on Community Preventive Services. Am J Prev Med. Jan 2000;18(1 Suppl):44–74. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(99)00122-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.The Community Guide. Methods Manual for Community Guide Systematic Reviews. Accessed November 7, 2023. https://www.thecommunityguide.org/pages/methods-manual.html

- 15.DeLuca JB, Mullins MM, Lyles CM, Crepaz N, Kay L, Thadiparthi S. Developing a comprehensive search strategy for evidence based systematic reviews. Evid Based Lib Inf Pract. March/17 2008;3(1):3–32. doi: 10.18438/B8KP66 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kamitani E, Johnson WD, Wichser ME, Adegbite AH, Mullins MM, Sipe TA. Growth in proportion and disparities of HIV PrEP use among key populations identified in the United States national goals: Systematic review and meta-analysis of published surveys. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. Aug 1 2020;84(4):379–386. doi: 10.1097/qai.0000000000002345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Compendium of evidence-based interventions and best practices for HIV prevention: pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) chapter. Updated February 23, 2022. Accessed February 1, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/research/interventionresearch/compendium/prep/index.html.

- 18.The World Bank. World Bank Country and Lending Groups. Accessed February 1, 2024. https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519),

- 19.Hernandez JBR, Kim PY. Epidemiology Morbidity And Mortality. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing Copyright © 2023, StatPearls Publishing LLC.; 2023. [Updated 2022 Oct 3]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024. Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK547668/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guide to Community Preventive Services. TFFRS - HIV Prevention: Digital Health Interventions to Improve Adherence to HIV Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis. Updated October 11, 2022. Accessed February 1, 2024. https://www.thecommunityguide.org/pages/tffrs-hiv-prevention-digital-health-interventions-improve-adherence-hiv-pre-exposure-prophylaxis.html

- 21.van den Elshout MAM, Hoornenborg E, Achterbergh RCA, et al. Improving adherence to daily preexposure prophylaxis among MSM in Amsterdam by providing feedback via a mobile application. AIDS. Sep 1 2021;35(11):1823–1834. doi: 10.1097/qad.0000000000002949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Colson PW, Franks J, Wu Y, et al. Adherence to pre-exposure prophylaxis in black men who have sex with men and transgender women in a community setting in Harlem, NY. AIDS Behav. Dec 2020;24(12):3436–3455. doi: 10.1007/s10461-020-02901-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moore DJ, Jain S, Dubé MP, et al. Randomized controlled trial of daily text messages to support adherence to preexposure prophylaxis in individuals at risk for human immunodeficiency virus: The TAPIR Study. Clin Infect Dis. May 2 2018;66(10):1566–1572. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix1055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fuchs JD, Stojanovski K, Vittinghoff E, et al. A mobile health strategy to support adherence to antiretroviral preexposure prophylaxis. AIDS Patient Care STDS. Mar 2018;32(3):104–111. doi: 10.1089/apc.2017.0255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mitchell JT, LeGrand S, Hightow-Weidman LB, et al. Smartphone-based contingency management intervention to improve pre-exposure prophylaxis adherence: Pilot trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2018;6(9):e10456. doi: 10.2196/10456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu AY, Vittinghoff E, von Felten P, et al. Randomized controlled trial of a mobile health intervention to promote retention and adherence to preexposure prophylaxis among young people at risk for human immunodeficiency virus: The EPIC study. Clin Infect Dis. May 30 2019;68(12):2010–2017. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Whiteley L, Craker L, Haubrick KK, et al. The impact of a mobile gaming intervention to increase adherence to pre-exposure prophylaxis. AIDS Behav. Jun 2021;25(6):1884–1889. doi: 10.1007/s10461-020-03118-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mitchell JT, Burns CM, Atkinson B, et al. Feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary Effficacy of a gamified mobile health contingency management intervention for PrEP adherence among Black MSM. AIDS Behav. Oct 2022;26(10):3311–3324. doi: 10.1007/s10461-022-03675-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weitzman PF, Zhou Y, Kogelman L, Rodarte S, Vicente SR, Levkoff SE. mHealth for pre-exposure prophylaxis adherence by young adult men who have sex with men. Mhealth. 2021;7:44. doi: 10.21037/mhealth-20-51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guide to Community Preventive Services. HIV Prevention: Digital Health Interventions to Improve Adherence to HIV Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis: Summary Evidence Table. 2021. Accessed February 1, 2024. https://www.thecommunityguide.org/media/2022/set-hiv-prep-508.pdf

- 31.National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) Clinical Trials Network. Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST-10). Accessed February 1, 2024. https://cde.drugabuse.gov/sites/nida_cde/files/DrugAbuseScreeningTest_2014Mar24.pdf

- 32.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: US Public Health Service. Preexposure Prophylaxis for the Prevention of HIV infection in the United States - 2021 Update: a clinical practice guideline. 2021. Accessed February 1, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/risk/prep/cdc-hiv-prep-guidelines-2021.pdf?msclkid=c0988d62a62d11ecbc61ab52784fea5b

- 33.Wong KYK, Stafylis C, Klausner JD. Telemedicine: a solution to disparities in human immunodeficiency virus prevention and pre-exposure prophylaxis uptake, and a framework to scalability and equity. Mhealth. 2020;6:21. doi: 10.21037/mhealth.2019.12.06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Statista. Percentage of U.S. adults who own a smartphone from 2011 to 2021. March 21st,, 2022. Updated April. Accessed February 1, 2024. https://www.statista.com/statistics/219865/percentage-of-us-adults-who-own-a-smartphone/

- 35.Pew Research Center. Internet/Broadbanc Fact Sheet. Updated January 31 2024. Accessed February 1, 2024. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/fact-sheet/internet-broadband/

- 36.Vogels EA. Digital divide persists even as Americans with lower incomes make gains in Updated June 22nd, 2021. Accessed February 1, 2024. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/06/22/digital-divide-persists-even-as-americans-with-lower-incomes-make-gains-in-tech-adoption/

- 37.Vogels EA. Some digital divides persist between rural, urban and suburban America. Updated August 19th, 2021. Accessed February 1, 2024. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/08/19/some-digital-divides-persist-between-rural-urban-and-suburban-america/

- 38.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Paying for PrEP. October 5, 2023. Updated June 6, 2022. Accessed February 1, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/basics/prep/paying-for-prep/index.html

- 39.Abbas UL, Glaubius R, Mubayi A, Hood G, Mellors JW. Antiretroviral therapy and pre-exposure prophylaxis: Combined impact on HIV transmission and drug resistance in South Africa. J Infect Dis. 2013;208(2):224–234. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gilead. Gilead’s advancing access® programs is here to help you. Accessed February 1, 2024. https://www.gileadadvancingaccess.com/

- 41.National Alliance of State and Territorial AIDS Directors. PrEP/PEP Access: State PrEP assistance programs. Accessed February 1, 2024. https://nastad.org/prepcost-resources/prep-assistance-programs

- 42.Helathcare Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) Journal. HIPAA Compliance Checklist 2022. Accessed February 1, 2024. https://www.hipaajournal.com/hipaa-compliance-checklist/