Summary

The intestinal lamina propria (LP) is a leukocyte-rich cornerstone of the immune system owing to its vital role in immune surveillance and barrier defense against external pathogens. Here, we present a protocol for isolating and analyzing immune cell subsets from the mouse intestinal LP for further downstream applications. Starting from tissue collection and cleaning, epithelium removal, and enzymatic digestion to collection of single cells, we explain each step in detail to maximize the yield of immune cells from the intestinal LP.

Subject areas: Cell isolation, Flow Cytometry, Immunology

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Protocol for the isolation of murine leukocytes from the intestinal lamina propria

-

•

Comparative analysis of the isolation efficiency of three widely used digestion enzymes

-

•

Assessment of intestinal immune cells using minimal 8-color flow cytometry panels

-

•

Advice for choosing the digestion enzyme based on the cell of interest to maximize yield

Publisher’s note: Undertaking any experimental protocol requires adherence to local institutional guidelines for laboratory safety and ethics.

The intestinal lamina propria (LP) is a leukocyte-rich cornerstone of the immune system owing to its vital role in immune surveillance and barrier defense against external pathogens. Here, we present a protocol for isolating and analyzing immune cell subsets from the mouse intestinal LP for further downstream applications. Starting from tissue collection and cleaning, epithelium removal, and enzymatic digestion to collection of single cells, we explain each step in detail to maximize the yield of immune cells from the intestinal LP.

Before you begin

Protocol for the isolation of immune cells from murine intestinal lamina propria

The gastrointestinal tract is the body’s largest non-lymphoid reservoir of immune cells.1 Among the different anatomical regions of the gut, the intestinal lamina propria (LP) is rich in leukocytes owing to its pivotal role in immune surveillance and barrier protection against external pathogens.2 The intestinal immune compartment comprises a collaborative network of a myriad of innate and adaptive immune cells that together play a cardinal role in gut homeostasis. This network includes specialized secondary lymphoid structures such as Peyer’s patches, cryptopatches, and isolated lymphoid follicles that contribute significantly to the intestinal immune landscape.3 Recent studies have shown that environmental perturbations influence the gut microbiome, leading to immune dysfunction and even neuropathologies.4,5 To understand the underlying mechanisms governing these cellular and molecular changes, it is essential to study in detail the individual LP immune cells and their interplay. Isolating immune cells from the LP is a complex multistep process involving a pre-digestion step to strip away the epithelium and intraepithelial leukocytes, followed by enzymatic digestion to dissociate the connective tissue and collect the immune cells residing within the LP.6,7,8 Isolated cells can then be analyzed using flow cytometry or sorted for further follow-up analyses, like single-cell sequencing, RNA extraction, or protein analysis. There is a plethora of different protocols circulating for the digestion and recovery of LP lymphocytes, most of them essentially differing in the enzymes used. However, different enzymes also differentially preserve cell surface antigens, depending on the cell type. In this methods article, we therefore discuss how to choose the best enzyme to digest the intestinal tissue based on the cell population of interest. The proper choice of digestion enzyme is critical for maximizing the yield of immune populations without perturbing marker expressions during intestinal immune cell isolation.9 We provide a comprehensive overview of the best enzymatic digestions for isolation of specific leukocyte populations in the intestinal LP. We believe that choosing the most suitable digestion protocol is instrumental for advancing our understanding of the intricate interplay between immune cells, the gut microbiome,10,11 and the broader physiological ramifications therein.12

Institutional permissions

All mice used for these experiments were bred and maintained in SPF conditions at the Translational Animal Research Center of the University Medical Center Mainz. All animals were used in accordance with federal and state policies. Before performing the experiment explained below, please make sure to acquire permissions from the relevant regional ethics committee.

Mice

All mice used for these experiments were C57BL/6J. The experimental mice were always age-, gender- and vivarium- matched, since these factors immensely affect the immune cell composition in the intestinal LP.13,14

Preparation of media, buffers, and antibody mix

Prepare buffers and media

Timing: 30 min

-

1.

Label one full set of tubes for each organ that will be processed. One full set of tubes = 3 × 50 mL conical tubes (for strip, shake and collection) and 1 × 25 mL conical tube (for digestion).

-

2.

Prepare 3% media (recipe to be found in materials and equipment) and keep it cold. We recommend preparing at least 75 mL per intestinal sample (one intestinal sample = one colon or one small intestine).

-

3.

Prepare required volumes of strip and shake media fresh, according to the recipe specified in materials and equipment, and keep them cold.

-

4.Add strip and shake media to their respective 50 mL conical tubes.

-

a.Strip media: Add 20 mL for the small intestine and 10 mL for the colon.

-

b.Shake media: Add 20 mL for the small intestine and 15 mL for the colon.

-

a.

-

5.

Prepare digestion media according to the cell type of interest. Appropriate recipes and volumes are listed in the materials section below. Prepare the media fresh and keep it cold to keep the enzymes inactive.

-

6.

Add 2 mL and 1 mL of digestion media to the 25 mL conical tubes for the small intestine and colon, respectively.

-

7.

Turn on the incubators with horizontal shakers and set them to 37°C.

-

8.

Label the 10 cm petri dishes (1/mouse) and 6-well plates (1 well/sample) and fill them with 10 and 5 mL of cold 3% media, respectively.

CRITICAL: Keep all the media, 6-well plates, and conical tubes on ice/at 4°C unless specified explicitly.

Prepare antibody-mix

Timing: 30 min

-

9.

Prepare the antibody-mix fresh on the day of the experiment (50 μL/sample). The dilutions and clone names of the antibodies used for the different staining panels can be found in materials and equipment section.

-

10.

Prepare the surface antibody mix in FACS Buffer I and intracellular antibody mix in 1× permeabilization buffer from the eBioscience Foxp3 / Transcription Factor Staining Buffer Set.

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Anti-mouse B220 (clone ID RA3-6B2) | BioLegend | Cat# 103234 |

| Anti-mouse CD11b (clone ID M1/70) | BioLegend | Cat# 101212 |

| Anti-mouse CD11b (clone ID M1/70) | BioLegend | Cat# 101216 |

| Anti-mouse CD11c (clone ID HL3) | BD Biosciences | Cat# 550261 |

| Anti-mouse CD127 (IL-7Rα) (clone ID A7R34) | BioLegend | Cat# 135009 |

| Anti-mouse CD138 (clone ID 281-2) | BioLegend | Cat# 142508 |

| Anti-mouse CD19 (clone ID 1D3) | BioLegend | Cat# 115520 |

| Anti-mouse CD19 (clone ID 1D3) | eBioscience | Cat# 13-0193 |

| Anti-mouse CD25 (IL-2Rα) (clone ID 7D4) | BD Biosciences | Cat# 553072 |

| Anti-mouse CD267 (TACI) (clone ID 8F10) | BioLegend | Cat# 133403 |

| Anti-mouse CD335 (NKp46) (clone ID 29A1.4) | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 46-3351-80 |

| Anti-mouse CD3ε (clone ID 145-2C11) | BioLegend | Cat# 100304 |

| Anti-mouse CD4 (clone ID RM4-5) | BioLegend | Cat# 100527 |

| Anti-mouse CD45 (clone ID 30-F11) | BioLegend | Cat# 103138 |

| Anti-mouse CD5 (clone ID 53-7.3) | BioLegend | Cat# 100603 |

| Anti-mouse CD8α (clone ID 5H10) | Invitrogen | Cat# MCD0805 |

| Anti-mouse CD90.2 (Thy1.2) (clone ID 53-2.1) | BioLegend | Cat# 140316 |

| Anti-mouse FcεR1a (clone ID MAR-1) | BioLegend | Cat# 134304 |

| Anti-mouse FoxP3 (clone ID FJK-16s) | eBioscience | Cat# 12-5773 |

| Anti-mouse Gr-1 (clone ID RB6-8C5) | BioLegend | Cat# 108403 |

| Anti-mouse KLRG1 (clone ID 2F1) | eBioscience | Cat# 17-5893-81 |

| Anti-mouse Ly6C (clone ID AL-21) | BD Biosciences | Cat# 560594 |

| Anti-mouse Ly6G (clone ID 1A8) | BioLegend | Cat# 127608 |

| Anti-mouse MHC-II (clone ID M5/114.15.2) | BioLegend | Cat# 107605 |

| Anti-mouse RORγt (clone ID Q31-378) | BD Biosciences | Cat# 562894 |

| Anti-mouse TCRγδ (clone ID UC7-13D5) | eBioscience | Cat# 13-5811 |

| Anti-mouse TCRγδ (clone ID eBio GL3) | eBioscience | Cat# 46-5711 |

| Anti-mouse TCRβ (clone ID H57-597) | BioLegend | Cat# 109205 |

| Anti-mouse TCRβ (Clone ID H57-597) | BD Biosciences | Cat# 553169 |

| Fixable viability dye | eBioscience | Cat# 65-0865 |

| Streptavidin | eBioscience | Cat# 47-4317 |

| Mouse Fc-block | Bio X Cell | Cat# BE0307 |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| BD Cytofix/Cytoperm Fixation/Permeabilization Kit | BD Biosciences | Cat# AB_2869008 |

| Brefeldin A | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# P1585-1MG |

| Collagenase D (>0.15 U/mg lyophilizate) | Roche | Cat# 11088882001 |

| Collagenase VIII (≥125 U/mg lyophilizate) | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# C2139-1G |

| Deoxyribonuclease (DNase) I from bovine pancreas | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# DN25-1G |

| Dispase II (neutral protease, grade II) (0,8 U/mg) | Roche | Cat# 4942078001 |

| Dithiothreitol (DTT) | Roche | Cat# 10708984001 |

| DMEM/F-12 (with GlutaMAX) | Gibco Life Technologies | Cat# 31331093 |

| Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# E9884 |

| Foxp3/Transcription factor staining buffer set | eBioscience | Cat# 00-5523-00 |

| HEPES buffer (1 M) | Gibco Life Technologies | Cat# 15630080 |

| IMDM | Gibco Life Technologies | Cat# 12440053 |

| Ionomycin | PromoKine | Cat# PK-CA577-1565-5 |

| L-glutamine 200 mM | Gibco Life Technologies | Cat# A2916801 |

| Liberase TL Research Grade | Roche | Cat# 5401020001 |

| Penicillin/Streptomycin (P/S) | Gibco Life Technologies | Cat# 15140122 |

| Percoll | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# GE17-0891-01 |

| Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# B6542-5MG |

| Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (1×) | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# D8537-500ML |

| RPMI-1640 (with GlutaMAX) | Gibco Life Technologies | Cat# 61870036 |

| Sodium pyruvate (100 mM) | Gibco Life Technologies | Cat# 11360070 |

| Trypan blue solution, 0.4% | Gibco Life Technologies | Cat# 15250061 |

| β-Mercaptoethanol (β-ME) | AppliChem | Cat# A1108.0250 |

| Experimental models: Organisms/strains | ||

| C57BL/6J mice (males and females; 8–12 weeks old) | The Jackson Laboratory | Cat# 000664 |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| GraphPad Prism (version: 10.1.2) | Dotmatics | https://www.graphpad.com |

| FlowJo (version: 10.8.1) | BD Biosciences | https://www.flowjo.com |

| BD FACSDiva (version: 6.1.3) | BD Biosciences | https://www.bdbiosciences.com |

| Other | ||

| Cell strainer (100 μm) | Sarstedt AG | Cat# 83.3945.100 |

| Cell strainer (70 μm) | Sarstedt AG | Cat# 83.3945.070 |

| Centrifuge (Heraeus Megafuge 16R) | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 7500 4270 |

| Conical tubes (50 mL) | Greiner Bio-One | Cat# 227261 |

| BD FACS Canto II flow cytometer | BD Biosciences | N/A |

| Luna automated cell counter | BioCat | Cat# LUC-04-00786 |

| Metal strainer | Dille & Kamille | Cat# 53270012 |

| Narrow pattern forceps | Fine Science Tools | Cat# 11003-18 |

| Noyes spring scissors | Fine Science Tools | Cat# 15012-12 |

| Nylon mesh – 200 pore size | SEFAR Medifab | Cat# 03-200/54 |

| Nylon mesh – 70 pore size | SEFAR Medifab | Cat# 03-70/33 |

| BRAND LDPE Pasteur pipettes | Fisher Scientific | Cat# 10222661 |

| Petri dishes (100 mm × 20 mm polystyrene) | Corning | Cat# 430 591 |

| Surgical forceps | Fine Science Tools | Cat# 11009-15 |

| Surgical scissors, 11.5 cm sharp/sharp | Fine Science Tools | Cat# 91460-11 |

| Surgical scissors, 18.5 cm sharp/blunt | Fine Science Tools | Cat# 14000-18 |

| V-bottom plates (96-well) | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 2605 |

Materials and equipment

Stock media

T Cell Medium

| Reagents | Stock concentration | Final concentration | Volume |

|---|---|---|---|

| RPMI | N/A | N/A | 450 mL |

| FCS | 100% | 10% (v/v) | 50 mL |

| L-glutamine | 200 mM | 2 mM | 5 mL |

| Penicillin G | 10,000 units/mL | 100 U/mL | 5 mL |

| Streptomycin | 10,000 μg/mL | 100 μg/mL | 5 mL |

| HEPES | 1 M | 10 mM | 5 mL |

| NEAA | 100× | 1× | 5 mL |

| Sodium Pyruvate | 100 mM | 1 mM | 5 mL |

| β-Mercaptoethanol | 100 mM (in PBS, prepared from commercial stock) | 50 μM | 250 μL |

Note: The media mentioned above must be stored at 4°C. We recommend not storing them longer than 6 weeks, so long as the color has not changed from orange to pink. If any change in color occurs, discard the media and prepare fresh, as this is an indication of altered pH.

B Cell Medium

| Reagents | Stock concentration | Final concentration | Volume |

|---|---|---|---|

| DMEM | N/A | N/A | 450 mL |

| FCS | 100% | 10% (v/v) | 50 mL |

| L-glutamine | 200 mM | 2 mM | 5 mL |

| Penicillin G | 10,000 units/mL | 100 U/mL | 5 mL |

| Streptomycin | 10,000 μg/mL | 100 μg/mL | 5 mL |

| HEPES | 1 M | 10 mM | 5 mL |

| NEAA | 100× | 1× | 5 mL |

| Sodium Pyruvate | 100 mM | 1 mM | 5 mL |

| β-Mercaptoethanol | 100 mM | 50 μM | 250 μL |

Note: The media mentioned above must be stored at 4°C. We recommend not storing them longer than 6 weeks, so long as the color has not changed from orange to pink. If any change in color occurs, discard the media and prepare fresh, as this is an indication of altered pH.

3% Medium

| Reagents | Stock concentration | Final concentration | Volume |

|---|---|---|---|

| RPMI | N/A | N/A | 450 mL |

| L-glutamine | 200 mM | 2 mM | 5 mL |

| Penicillin G | 10,000 units/mL | 100 U/mL | 5 mL |

| Streptomycin | 10,000 μg/mL | 100 μg/mL | 5 mL |

| FCS | 100% | 3% (v/v) | 15 mL |

| HEPES | 1 M | 20 mM | 10 mL |

Note: The media mentioned above must be stored at 4°C. We recommend not storing them longer than 6 weeks, so long as the color has not changed from orange to pink. If any change in color occurs, discard the media and prepare fresh, as this is an indication of altered pH.

0% Medium

| Reagent | Stock concentration | Final concentration | Volume |

|---|---|---|---|

| RPMI | N/A | 500 mL | |

| L-glutamine | 200 mM | 2 mM | 5 mL |

| Penicillin G | 10,000 units/mL | 100 U/mL | 5 mL |

| Streptomycin | 10,000 μg/mL | 100 μg/mL | 5 mL |

| β-Mercaptoethanol | 100 mM | 50 μM | 250 μL |

| HEPES | 1 M | 20 mM | 10 mL |

| Sodium Pyruvate | 100 mM | 1 mM | 5 mL |

Note: This media is only required in small amounts for the digestion step. 0% media can, however, be prepared in a 500 mL RPMI media bottle and stored for up to 3 months at 4°C.

Shake Medium

| Reagent | Stock concentration | Final concentration | Volume |

|---|---|---|---|

| RPMI | N/A | N/A | 500 mL |

| L-glutamine | 200 mM | 2 mM | 5 mL |

| Penicillin G | 10,000 units/mL | 100 U/mL | 5 mL |

| Streptomycin | 10,000 μg/mL | 100 μg/mL | 5 mL |

| EDTA | 0.5 M | 2 mM | 2 mL |

| HEPES | 1 M | 20 mM | 10 mL |

Note: Make enough shake media for the total number of samples: 40 mL shake media may be used per small intestine sample (20 mL – twice) and 30 mL shake media is used per colon (15 mL – twice). Media can be prepared within a 500 mL RPMI media bottle and stored at 4°C for up to 6 weeks, so long as the color has not changed from orange to pink. If any change in color occurs, discard the media, and prepare fresh, as this is an indication of altered pH.

Strip Medium

| Reagent | Stock concentration | Final concentration | Volume (small intestine) | Volume (colon) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3% Media (recipe above) | N/A | N/A | 20 mL | 10 mL |

| EDTA | 0.5 M | 5 mM | 200 μL | 100 μL |

| DTT | 1 M | 1 mM | 20 μL | 10 μL |

Note: Make enough strip media for the total number of samples on the day of experiment, as DTT must be used fresh. Please refrain from storing longer than 24 h.

Digestion medium

Collagenase D – digestion media:

| Reagent | Stock concentration | Final concentration | Volume (small intestine) | Volume (colon) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HBSS | 1× | 1× | 5 mL | 3 mL |

| FCS | 100% | 2% | 100 μL | 60 μL |

| Collagenase D | 100 mg/mL | 500 μg/mL | 25 μL | 15 μL |

| Dispase type II | 25 U/mL | 0.5 U/mL | 100 μL | 60 μL |

| DNase I | 100 mg/mL | 500 μg/mL | 25 μL | 15 μL |

Note: Enough digestion media should be made fresh on the day of experiment for the total number of samples and stored at 4°C. Please do not store the media for later use as the activity of the enzymes will be affected.

Collagenase VIII – digestion media

| Reagent | Stock concentration | Final concentration | Volume (small intestine) | Volume (colon) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IMDM media | 1× | 1× | 10 mL | 6 mL |

| FCS | 100% | 10% | 1 mL | 600 μL |

| Collagenase VIII | N/A | 1 mg/mL | 10 mg | 6 mg |

| DNase I | 100 mg/mL | 500 μg/mL | 50 μL | 30 μL |

Note: Enough digestion media should be made fresh on the day of experiment for the total number of samples and stored at 4°C. Please do not store the media for later use as the activity of the enzymes will be affected.

Liberase TL – digestion media

| Reagent | Stock concentration | Final concentration | Volume (small intestine) | Volume (colon) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0% Media (recipe above) | N/A | N/A | 10 mL | 6 mL |

| Liberase TL | 5 mg/mL | 100 μg/mL | 200 μL | 120 μL |

| DNase I | 100 mg/mL | 500 μg/mL | 50 μL | 30 μL |

Note: Enough digestion media should be made fresh on the day of experiment for the total number of samples and stored at 4°C. Please do not store the media for later use as the activity of the enzymes will be affected.

Note: All the aforementioned enzymes can be freshly prepared from the original stock (usually in powder form) or they can be dissolved in PBS (with no supplements) and stored at −20°C for up to 6 months. However, we do not suggest thawing the frozen stocks more than 5 times. But please check the product specifications before you dissolve to choose the appropriate medium and temperature of storage.

FACS buffers

-

•

FACS Buffer I: 2% (v/v) FCS to PBS (i.e., 10 mL FCS to 500 mL of PBS).

-

•

FACS Buffer II: 20 mM concentration of EDTA (pH 8.0) to FACS Buffer I.

Note: The FACS buffers can be stored at 4°C for up to three months.

Antibody mix

T cell panel

| Fluorochrome | Antibody | Dilution factor | Clone |

|---|---|---|---|

| FITC | TCRβ | 1:200 | H57-597 |

| PE | FoxP3 | 1:100 | FJK-16s |

| PerCP | TCRgd | 1:200 | eBioGL3 |

| PE-Cy7 | CD4 | 1:400 | RM4-5 |

| APC | CD8α | 1:200 | 5H10 |

| APC-eFl780 | Fixable viability dye | 1:1000 | N/A |

| BV421 | RORgt | 1:400 | Q31-378 |

| BV510 | CD45 | 1:200 | 30-F11 |

Note: The antibody mix must be prepared fresh on the day of experiment and stored at 4°C. This is especially applicable for tandem dyes which have an increased tendency to degrade/dissociate.

B cell panel

| Fluorochrome | Antibody | Dilution factor | Clone |

|---|---|---|---|

| FITC | MHC-II | 1:1000 | M5/114.15.2 |

| PE | CD267 (TACI) | 1:200 | 8F10 |

| PerCP | B220 (CD45R) | 1:200 | RA3-6B2 |

| PE-Cy7 | CD19 | 1:2000 | 6D5 |

| APC | CD11b | 1:1000 | M1/70 |

| APC-eFl780 | Fixable viability dye | 1:1000 | N/A |

| BV421 | CD138 | 1:400 | 281–2 |

| BV510 | CD45 | 1:200 | 30-F11 |

Note: The antibody mix must be prepared fresh on the day of experiment and stored at 4°C. This is especially applicable for tandem dyes which have an increased tendency to degrade/dissociate.

ILC panel

| Fluorochrome | Antibody | Dilution factor | Clone |

|---|---|---|---|

| FITC | CD25 | 1:100 | 7D4 |

| PE | CD127 | 1:100 | A7R34 |

| PerCP | CD335 | 1:200 | 29A1.4 |

| PE-Cy7 | Streptavidin | 1:100 | N/A |

| APC | KLRG1 | 1:200 | 2F1 |

| APC-eFl780 | Fixable viability dye | 1:1000 | N/A |

| BV421 | RORgt | 1:400 | Q31-378 |

| BV510 | CD45 | 1:200 | 30-F11 |

| Biotinylated antibodies: | CD3ε | 1:100 | 145-2C11 |

| CD19 | 1:200 | 1D3 | |

| CD5 | 1:400 | 53–7.3 | |

| TCRβ | 1:200 | H57-597 | |

| TCRgd | 1:200 | UC7-13D5 | |

| FcεR1a | 1:400 | MAR-1 | |

| Gr-1 | 1:400 | RB6-8C5 |

Note: The antibody mix must be prepared fresh on the day of experiment and stored at 4°C. This is especially applicable for tandem dyes which have an increased tendency to degrade/dissociate.

Myeloid cell panel

| Fluorochrome | Antibody | Dilution factor | Clone |

|---|---|---|---|

| FITC | MHC-II | 1:1000 | M5/114.15.2 |

| PE | Ly6G | 1:400 | 1A8 |

| PerCP | CD90.2 | 1:1000 | 53–2.1 |

| PE-Cy7 | CD11b | 1:500 | M1/70 |

| APC | CD11c | 1:200 | HL3 |

| APC-eFl780 | Fixable viability dye | 1:1000 | N/A |

| BV450 | Ly6C | 1:100 | AL-21 |

| BV510 | CD45 | 1:200 | 30-F11 |

Note: The antibody mix must be prepared fresh on the day of experiment and stored at 4°C. This is especially applicable for tandem dyes which have an increased tendency to degrade/dissociate.

CRITICAL: β-Mercaptoethanol is acutely toxic to inhale and a skin irritant. DTT can also cause skin irritation and serious eye damage. Please take the necessary precautions suggested by the institute safety guidelines and the manufacturer while using those reagents. Wear protective gloves and clothing and handle these chemicals under a well-ventilated fume hood.

Step-by-step method details

Collection of tissue from the mouse

Timing: 5–10 min (per mouse)

This step describes the collection of the intestinal tissue from the peritoneal cavity of a mouse. When referring to both the small intestine and colon, they will be referred to as the intestine.

-

1.

Euthanize the mouse using carbon dioxide (CO2) or another method of your choice adhering to 3R (Replacement, Reduction and Refinement) guidelines.

Note: Before euthanizing mice, place the shake media at room temperature to bring to ambient temperature.

-

2.

Fix the mouse on a dissection board and spray the abdominal area with 70% ethanol (Figure 1A).

-

3.

To remove the intestine from the peritoneal cavity (See Methods video S1):

-

a.Cut open the abdomen to access the peritoneal cavity (Figure 1B) using 18.5 cm surgical scissors.

-

b.To collect the small intestine, make an incision just below the stomach.

-

c.Hold the open duodenal end of the small intestine and use a small 11.5 cm surgical scissors to detach the intestine from the mesenteric fat by gently scraping along the length of the small intestine with the sharp end of the open scissors.

-

d.Once the cecal end of the intestine is reached, cut right above the cecum, to detach and collect the small intestine (Figure 1C).Note: If desired, the cecum can be taken separately for analysis.

-

e.Transfer the detached small intestine to 3% media in a 6-well plate on ice until all mice are sacrificed and their intestines are collected.

-

f.To collect the colon, make a cut just below the cecum and use the small scissors to detach it from the fat by gently scraping along the length with the open scissors, similar to the small intestine (See Methods video S2).Methods video S2. Removal of the colon from the mouse (related to step 3F-H)Download video file (15.9MB, mp4)

-

g.Using 12 cm blunt-end dissection scissors, cut the pelvic bone through the rectal opening at a slightly lateral cutting angle, to minimize the damage to the tissue.

-

h.Cut the colon at the rectal end and transfer it to 3% media in a 6-well plate on ice until all mice are sacrificed and their intestines are collected (Figure 1D).Note: The small intestine and colon must be stored and digested separately as they differ in their immune cell compositions. As a standard recommendation, we suggest not to prepare more than 4 mice if working alone and when isolating both SI and colon. With experience, the number can be increased up to 6 mice per person.

CRITICAL: Two factors significantly affect the final cell viability of the tissues: the presence of mesenteric fat and the time between death of the mouse and tissue collection. While one should try to work as fast as possible throughout the protocol until cell fixation, it is also important to remove as much mesenteric fat as possible in earlier steps.

CRITICAL: Two factors significantly affect the final cell viability of the tissues: the presence of mesenteric fat and the time between death of the mouse and tissue collection. While one should try to work as fast as possible throughout the protocol until cell fixation, it is also important to remove as much mesenteric fat as possible in earlier steps.

Methods video S1. Opening of the peritoneal cavity and removal of the small intestine from the mouse (related to step 3A-D)Download video file (64.5MB, mp4) -

a.

Figure 1.

Steps involved in organ collection before the stripping of epithelial tissue

The small intestine and colon are collected from the animal for subsequent dissociation to collect the cells through enzymatic digestion.

(A) The animal is secured to a dissection board and the abdominal cavity is opened to access the peritoneum.

(B) The stomach can be found directly underneath the liver.

(C) An incision is made after the stomach at the beginning of the small intestine (SI).

(D) After gently removing the small intestine from the cavity, a cut is made at the end of the SI to detach it from the cecum.

(E) The collected intestines are placed in ice-cold 3% media in 6-well plates.

(F) Metal strainer set up on a glass beaker to transfer the intestines after the stripping and shaking steps, eliminating residual media containing the stripped epithelial cells.

Tissue cleaning and stripping of the epithelial layer

Timing: 3–7 min cleaning (per sample) + 20 min for stripping + 10 min for shaking

This step describes the removal of unwanted layers and segments of intestinal tissue, including the mesenteric fat, Peyer’s patches, and the intestinal epithelium.

-

4.Clean the intestine:

-

a.Remove residual fat along the intestine with forceps or fingers (See Methods video S3).Methods video S3. Removal of the mesenteric fat can be accomplished with forceps and/or fingers (related to step 4A)Download video file (118.6MB, mp4)

-

b.Cut out Peyer’s patches from the small intestine using small scissors (See Methods video S4). Skip the step for the colon as they don’t have Peyer’s patches.Note: There are typically around 6–10 Peyer’s patches along the small intestine of a C57BL/6 mouse.Methods video S4. Removal of the Peyer’s patches with small scissors (related to step 4B)Download video file (69MB, mp4)

-

c.Cut open the intestine longitudinally with small scissors. Using forceps, push out the feces and rinse it vigorously by shaking it in 3% media in a petri dish to clean out the residual feces (see Methods video S5).

CRITICAL: If the intestine is very dirty, due to age or an infection or inflammation model, place the tissue in a conical tube with 15–20 mL of 3% media and vortex/ manually shake for 10–15 s to get rid of the debris. The intestine must look clean and free of feces after this step. Note that extreme/prolonged manual shaking could impact the intra-epithelial cellular composition, while the lamina propria should not be affected.Methods video S5. Cleaning and rinsing the intestine (related to step 4C)Download video file (66.4MB, mp4)

CRITICAL: If the intestine is very dirty, due to age or an infection or inflammation model, place the tissue in a conical tube with 15–20 mL of 3% media and vortex/ manually shake for 10–15 s to get rid of the debris. The intestine must look clean and free of feces after this step. Note that extreme/prolonged manual shaking could impact the intra-epithelial cellular composition, while the lamina propria should not be affected.Methods video S5. Cleaning and rinsing the intestine (related to step 4C)Download video file (66.4MB, mp4)

-

a.

-

5.

Transfer the clean tissue to a conical tube with 20 mL of strip media and incubate at 37°C for 20 min on a horizontal shaker at about 80–100 rpm.

Note: If a horizontal shaker is not available, a bacterial shaker can be used alternatively.

-

6.

After incubation, vortex and strongly agitate the tubes for 30 s (see Methods video S6 and S7).

-

7.

Transfer the contents to a metal strainer (pore size about 300 m) placed on a glass beaker (Figure 1E).

Note: Alternatively, a nylon mesh sieve with 200 m pore size could be used. Smaller pore sizes must be avoided as tend to get clogged easily.

-

8.Using curved forceps, remove the tissue from the strainer and dab on paper towels to get rid of residual media. Discard the flowthrough.Optional: After steps 5 to 8, the cells from the epithelial layer will be in the flowthrough fraction collected in the beaker, and the remaining intestinal tissue will be left on the metal strainer. For studying the intraepithelial lymphocytes, a Percoll gradient can be used to obtain a pure suspension of immune cells: (Timing: additional 1–1.5 h)

-

a.Transfer the flow through to a 50 mL falcon and rinse the strainer with 10 mL of 3% media.

-

b.Spin down at 450 × g for 10 min at 4°C.

-

c.Prepare isotonic Percoll solution by mixing 90% of Percoll stock with 10% 10× PBS. From the isotonic Percoll, make 40% and 80% Percoll solutions by diluting in DMEM-10.

-

d.Discard the supernatant from b. and resuspend the cell pellet in 5 mL of 40% Percoll solution.

-

e.Gently overlay it on top of 3 mL of 80% Percoll in a 15 mL conical tube.

-

f.Centrifuge at 1300 × g for 20 min at 16°C, without brakes.

-

g.Aspirate the upper phase containing the fat and debris, using a Pasteur pipette, and transfer the ring interphase between the 40% and 80% Percoll layers into a fresh 15 mL tube.

-

h.Add 10 mL of FACS Buffer-I, invert to mix and spin the cells down at 450 × g for 10 min at 4°C. Discard the supernatant and count the cells in the pellet.

-

a.

-

9.Transfer the tissue to a 50 mL conical tube containing the shake media.

-

a.Vortex and physically agitate the sample by shaking the tube vigorously up and down for about 30 s.

-

b.Transfer the tissue to the metal strainer again, to discard the shake media.

-

c.The tissue should be pink at this point. If not, repeat the shaking step to get rid of the remaining epithelium (see troubleshooting problem 1).

-

a.

Enzymatic digestion of tissue

Timing: 2–3 min mechanical dissociation (per sample) + 28 min for enzymatic digestion

This step describes the digestion of the LP to obtain a single cell suspension of the resident immune cells. Important to note is that not all digestion enzymes will produce the same end result. This is mainly because enzymes have different effects on sensitive epitopes and can alter the reproducibility and significance of the data. So, make sure to prepare the enzymatic digestion media according to the cell types of interest.

-

10.

Transfer the tissue to fresh RPMI media (without FCS!) in a 6-well plate on ice to wash off the residual EDTA and FCS from the strip and shake media.

-

11.

Mechanically dissect the tissue into ∼1 mm3 pieces using Noyes spring scissors in a 25 mL conical tube containing 2 mL and 1 mL of digestion media, for the small intestine and colon, respectively. See Figure 2A.

Note: If you do not have these tubes, we suggest cutting the tissue in a 2 mL eppendorf tube and transferring the contents to a 50 mL conical tube. In this case, make sure to rinse the Eppendorf tube with media and transfer anything remaining to avoid cell loss.

-

12.

Add the respective volume of digestion media into the conical tube (8 mL for the small intestine and 5 mL for the colon). See Figure 2B.

Note: We recommend rinsing the scissors while pipetting the added media to obtain any leftover tissue or cells stuck to the scissors.

-

13.

Incubate the tissue suspension at 37°C for 28 min on a rotating horizontal shaker at 80–100 rpm.

Figure 2.

Manual dissociation of the intestinal tissue to facilitate better enzymatic digestion

After the stripping step, the tissue is transferred to a 25 mL conical tube containing 1 mL of digestion media and cut into 1mm pieces to aid in enzymatic digestion.

(A) This demonstrates a simple and efficient method of using two small scissors to cut the stripped intestinal tissue into tiny pieces. It’s important to do this in 1 mL volume to facilitate thorough cutting of the tissue.

(B) The tissue should resemble the image shown here after mechanical dissociation. If the tissue appears as large chunks, further cutting is necessary to ensure better tissue digestion.

(C) Expected pellet size of isolated single cells from colonic-LP. Image shown is from colon, though similar pellet sizes are expected from colon and small intestine.

Collection of dissociated cells

Timing: 25–30 min

This step describes the collection of single cells from the intestinal tissue following the mechanical and enzymatic dissociation.

-

14.

Pipette 10 mL of 3% media on a 100 μm filter on a clean 50 mL conical tube (collection tube).

-

15.

Following the 28-min enzymatic digestion, vortex and shake the digested samples vigorously and apply the cell suspension to the 100 μm filter on the labeled collection tubes.

-

16.

Using the flat-end (non-rubber side) of the plunger from a 1 mL syringe, mash the bigger pieces of the intestine leftover on the filter.

Note: If the tissue was well cut in step 10, there will be minimal tissue residue. If you have excessive undigested tissue, we suggest repeating the digestion step and consider chopping the tissue into much smaller pieces the following time. See troubleshootingproblem 2.

-

17.

Pipette 10 mL of 3% media into the digestion tube, thereby rinsing the piston (these can be cleaned, autoclaved and reused), and pass this volume through the filter. Wash the filter with an additional 5 mL of fresh 3% media.

-

18.

Centrifuge the cell suspension at 450 × g for 10 min at 4°C

-

19.Discard the supernatant and resuspend the pellet in 5 mL of 3% media. See troubleshooting problem 3.Optional: Percoll gradient can be used to obtain a pure suspension of immune cells. Please refer to optional section of step 8, for protocol to prepare 40% and 80% Percoll solutions. (Timing: additional 1 h)

-

a.Resuspend the cell pellet in 5 mL of 40% Percoll solution and gently overlay it on top of 3 mL of 80% Percoll in a 15 mL conical tube.

-

b.Centrifuge the tubes at 1300 × g for 20 min at room temperature without brakes.

-

c.Remove the upper phase containing the fat and debris and transfer the ring interphase between the 40% and 80% Percoll layers into a fresh 15 mL conical tube.

-

d.Add 10 mL of FACS Buffer-I to wash the residual Percoll and mix well by inverting.

-

e.Spin the cells down at 450 × g for 10 min at 4°C. Discard the supernatant and resuspend the pellet in 1 mL of FACS Buffer-I, to count the cells.Note: The Percoll gradient step is time-consuming. When dealing with time-sensitive populations, we recommend skipping this and proceeding to the next step. Viable immune populations can be visualized in later analysis using a pan-leukocyte marker (e.g., CD45) and viability dye.

-

a.

-

20.

Pass the cell suspension through a 70 μm filter and wash the filter with 5 mL of fresh 3% media.

-

21.

Count cells to determine the total cell number. Resuspend the cells with equal volume of Trypan blue (1:1) and count the cells manually using a hemocytometer or use an automated cell counter.

-

22.

Centrifuge the remaining cell suspension at 450 × g for 10 min at 4°C and resuspend the pellet in the desired volume of media to get optimal cell numbers for staining or restimulation.

Note: If you do plan to use counting beads, resuspend the colon in 1 mL of FACS Buffer-I and the small intestine in 3 mL of FACS Buffer-I, and use 100 μL each for staining. In other cases, we suggest resuspending at a concentration of 10 x 106 cells/mL to get 2 million cells in 200 μL for restimulation and 1 million in 100 μL for staining. For stimulating or culturing T cells, myeloid cells, and ILCs, the cells are resuspended in T cell media. For stimulating B-cells, the cells should be resuspended in B cell media.

Pause point: The cells can be stored at 4°C for up to 4 h, if there is a need to pause the experiment.

Antibody staining for flow cytometry

Timing: variable depending on the choice of antibodies; approximately 2–4 h

To study the isolated immune populations, the cells should be stained with fluorochrome-labeled antibodies then analyzed using a flow cytometer. In this section, we will describe the process of staining and recommend a minimalistic 8-color antibody panel to identify T cells, B cells, ILCs, myeloid cells and their major subsets in the intestinal LP.

-

23.

Once the cells are resuspended, seed them in a labeled 96-well V-bottom plate and centrifuge at 300 × g for 5 min at 4°C. Throughout the staining process the V-bottom plate must be centrifuged at 300 × g for 5 min at 4°C unless explicitly mentioned otherwise (see troubleshooting problem 3).

Note: Staining can also be done in 1.5 mL eppendorf tubes. Volumes and centrifugation speeds remain the same, however up to 450 μL of FACS buffer should be used in the washing steps to get rid of unbound antibodies.

-

24.

Discard the supernatant and resuspend the cells in 50 μL of FACS Buffer-I containing Fc-block (anti-mouse CD16/CD32). Incubate the cells for 30 min at 4°C.

Note: This step is crucial as Fc receptors can non-specifically bind to the fluorescent-labeled antibodies and therefore give false-positive results.

-

25.

Meanwhile, prepare the antibody cocktails for staining different immune cell populations. Above are the (8-color) panels we used to test the enzymatic efficiency of the different digestion enzymes in isolating immune cells residing in the intestinal-LP.

-

26.

Add 150 μL of FACS Buffer-I to wash out the excess, unbound Fc block and centrifuge the plate 300 × g for 5 min at 4°C.

-

27.

Discard the supernatant and resuspend the cells in 200 μL of FACS Buffer-I to wash the cells. Centrifuge the plate at 300 × g for 5 min at 4°C and discard the supernatant.

-

28.

Resuspend the cell pellet in 50 μL of FACS Buffer-I containing the antibody mix, including biotinylated antibodies, fixable viability dye, and fluorochrome-labeled antibodies against surface antigens. Incubate for 30 min at 4°C in the dark. After the incubation, add 150 μL of FACS Buffer-I per well to wash out the unbound antibodies and repeat step 27.

Optional: If biotinylated antibodies were used, resuspend the cells in 50 μL of FACS Buffer-I containing fluorescently labeled streptavidin and incubate it for 30 min at 4°C in the dark. Wash the cells with 150 μL of FACS Buffer-I, centrifuge and discard the supernatant. Repeat step 27.

-

29.

Prepare the fixation solution in the eBioscience FoxP3 / Transcription Factor Staining Buffer Set, by diluting 1 part of the fixation/permeabilization concentrate with 3 parts of the fixation/permeabilization diluent. For 1× permeabilization wash buffer, add 9 parts of double-distilled water to 1 part of the 10× permeabilization buffer in the kit. Mix well before use.

Note: Prepare the solution fresh and store it in the dark at 4°C. The buffer can be stored longer and used as long as it is kept cold. The permeabilization buffer must be prepared with water and not PBS!

-

30.

Resuspend the cells in 100 μL of the fixation solution and incubate for 30 min to 1 h in the dark at 4°C. Add 100 μL of the permeabilization buffer to wash off the fixation solution, centrifuge, and discard the supernatant.

Optional: If there is no need for intracellular staining, skip steps 29 and 30. Instead, cells can be fixed with 100 μL of 2% formaldehyde for 60 min then washed with 100 μL of FACS Buffer-I. Centrifuge at 300 × g for 5 min at 4°C, discard the supernatant and resuspend the cells in 200 μL of FACS Buffer-II. Store in the dark at 4°C until acquisition on a flow cytometer.

Pause point: The cells can be stored at 4°C until the next day in the fixation solution if there is need to pause the experiment.

-

31.

Resuspend the pellet in 200 μL of permeabilization buffer to ensure permeabilization of the cells and to remove the residual fixation solution. Centrifuge at 400 × g for 5 min at 4°C and discard the supernatant.

-

32.

Resuspend the cells in 50 μL of permeabilization buffer containing the intracellular antibodies and incubate in the dark for 1 h at 4°C. If there is a weak staining of intracellular antigens, refer to troubleshooting problem 4 for suggestions.

Note: Some intracellular antibodies have better staining when they are incubated until the next day, so make sure to check which works for the antibodies in your panel.15

Pause point: Cells can be stored in the dark at 4°C until the next day in the antibody mix if there is a need to pause the experiment and if compatible with the specific antibodies in use (see Note in step 32).

-

33.

Add 150 μL of permeabilization buffer, centrifuge the cells at 400 × g for 5 min at 4°C and discard the supernatant. Repeat the wash with 200 μL of permeabilization buffer, centrifuge, and discard the supernatant.

-

34.

Resuspend the cells in 200 μL of FACS buffer-II and acquire them using a flow cytometer.

Note: The EDTA in the buffer allows the cells to remain separated, however, if the cell suspension looks turbid and the cells remain sticky, refer to troubleshootingproblem 5 for suggestions.

Optional: For cytokine staining, count cells and stimulate the same number of cells for all samples in the appropriate media containing kinase activator (e.g., PMA), calcium ionophore (e.g., ionomycin), and a Golgi-blocker (e.g., Brefeldin-A) for 4 h at 37°C. Following this, stain the cells using the same steps as mentioned above, starting from step 23. If there are no transcription factors in the staining panel, fix the cells with the BD Cytofix/Cytoperm Fixation/Permeabilization Kit. This is an economical and relatively gentler alternative to the eBioscience FoxP3 / Transcription Factor Staining Buffer Set as there is no permeabilization of the nuclear membrane. For a combination of cytokine and transcription factor staining, stimulate the cells as explained above and use the eBioscience FoxP3 / Transcription Factor Staining Buffer Set.

Expected outcomes

The intestinal LP serves as a collaborative hub for a large cohort of leukocytes that are continuously exposed to pathogens and foreign particles.10,11,16 To comprehend the role of these cells and their crosstalk in maintaining intestinal homeostasis, it is crucial to isolate and study them. This protocol is optimized for isolating viable leukocytes from the intestinal LP and is applicable to both the small intestine and colon. The required modifications in buffer volumes for small intestine versus colon are specified periodically throughout the protocol. In this section, we will discuss the results obtained for T and B lymphocytes as well as ILCs isolated from colonic-LP using the three common digestion enzymes employed for leukocyte isolation from the intestine. Additionally, we also include a comparative analysis of intestinal myeloid cells to complete the review of all major leukocyte subsets residing in the intestinal LP. This will allow to have a detailed overview of which enzyme is to be preferred for which specific cell type.

Using the aforementioned protocol, we isolated immune cells from the colonic LP of 8-week-old wild-type mice (mixed gender), stained them with fluorophore-labeled antibodies, and analyzed them via flow cytometry. The cells were counted before the staining process to obtain total cell number in the single-cell suspensions. An increased number of total isolated cells were obtained using collagenase VIII for tissue digestion compared to the other enzymes (Figure 3A). However, analysis of the stained cells using flow cytometry revealed that the isolated cells from the colonic LP of wild-type C57BL6/J mice did not show any major differences in their absolute number of live leukocytes (Live CD45+ cells) irrespective of the digestion enzyme (Figures 3B and 3C). Thus, all three digestion enzymes tested here will give similar yields for the final total numbers of isolated leukocytes.

Note: The absolute cell number of total live cells obtained varies based on the strain, age, and gender of the mice, as well as the kind of facility they are housed in. While mice housed in germ-free facilities yield relatively low cell numbers, mice housed in specific pathogen-free (SPF) facilities have a much higher yield of intestinal leukocytes. Be aware to use age- and gender-matched littermate controls from the same vivarium.

Figure 3.

Different digestion enzymes yield the same number of live leukocytes from the colonic-LP

Following isolation, colonic-LP cells were counted using an automated cell counter. Cells were then stained with fluorescent antibodies for flow cytometry to evaluate the number of leukocytes (CD45+ cells) among the total isolated cells.

(A) Total cell number after isolation from the colonic-LP counted using an automated cell counter.

(B and C) show the frequencies from total single leukocytes and absolute cell number, respectively, of total live CD45+ leukocytes isolated using different enzymes for enzymatic digestion from the colonic-LP quantified from flow cytometric analysis. While the overall cell numbers and viability remain high for cells isolated using the collagenase VIII digestion, graph C shows that all the enzymes yield a similar number of viable CD45+ leukocytes from the colonic-LP. Graphs shows mean +/− SEM (n = 4/group) and statistical tests were done using one-way ANOVA. ∗p ≤ 0.05.

Flow cytometric analysis of ILCs

ILCs are cells that develop from the common lymphoid progenitor, akin to B and T cells, but do not depend on the recombination-activating genes. They share similarities with T cells in their transcription factor profiles and cytokine production16.17 However, unlike T cells, they can respond to environmental cues in an "innate"-like manner. One of the major highlights of intestinal ILCs is their ability to express MHC-II and play a significant role in regulating CD4 T cell responses against commensals17.18 There are three major groups of ILCs. Group 1 ILCs express NKp46 and T-bet, include ILC1s and natural killer (NK) cells, and play critical roles in anti-viral responses. Group 2 ILCs express GATA3 and are important for allergic responses and the maintenance of airway homeostasis. Group 3 ILCs express RORγt, include lymphoid tissue inducer (LTi) cells, NKp46+ ILC3s, and NKp46- ILC3s, and are critical for anti-bacterial responses. This classification underscores the diverse functions of ILCs in the immune system, with each group specializing in specific responses and contributing to the overall regulation of immune activities, particularly within the intestinal environment.

As shown in Figure 4A, from the live CD45+ cells, total ILCs were gated as Lineage (CD3, CD5, TCRab, TCRgd, CD19, Gr-1 and FCεR1a)-negative CD127+ cells. Using surface receptor and transcription factor expression profiles, these cells were further classified into subsets as NKp46+ group 1 ILCs, RORgt+ (NKP46+/−) ILC3s and double-negative cells. ILC2s were identified from the double-negative population as KLRG1+ cells. From group 1 ILCs, NK cells were identified through their expression of KLRG1 (Figure S1). Comparative analysis of the different subsets shows that Liberase TL was able to give a better yield of ILCs compared to Collagenase D or Collagenase VIII, both in frequency as well as cell numbers of total ILCs (Figure 4B), ILC3s (Figure 4C) and ILC2s (Figure 4D). This demonstrates that Liberase TL is the superior choice of enzymatic digestion for isolation and analysis of intestinal ILCs.

Figure 4.

Liberase TL digestion results in a better isolation efficiency of ILCs

To assess the effectiveness of various digestion enzymes in isolating intestinal ILCs, we compared the yield from commonly used digestion enzymes (Collagenase D, Collagenase VIII, and Liberase TL) for isolating intestinal leukocytes. After isolating the total cells, we focused on live CD45+ cells. These cells were further analyzed by excluding Lineage+ cells by using antibodies targeting T cells (CD3e, TCRb, TCRgd, CD5), B cells (CD19, CD5), and myeloid cells (CD11b, Gr-1, and Fc Ra).

(A) Comparison of the common gating strategy used for analysis of the three different enzymatic digestion groups. Starting from live CD45+ leukocytes, we gated on lineage-negative CD127+ cells to capture total ILCs. Further gating on subsets of ILCs involved using RORγt to distinguish group 3 ILCs (ILC3s) and RORγt- NKp46+ cells as constituting group 1 (G1) ILCs. Within G1 ILCs, KLRG1 was used to separate ILC1s from NK cells (KLRG1+) (Figure S1). Additionally, from the RORγt-, NKp46- population, we gated on group 2 ILCs, identified as CD25+ KLRG1+ cells.

(B–D) Frequency and the absolute cell numbers of total Lin- CD127+ cells (graph B), G1 ILCs and ILC3s (graph C), and Group 2 ILCs (graph D) are shown. Comparative analysis among the three different enzymes clearly shows that Liberase TL facilitates better isolation of ILCs compared to collagenases D or VIII, both in terms of total ILC numbers as well as within group 2 and 3 ILCs. The graphs represent frequencies and absolute cell numbers as mean +/− SEM (n = 4/group) and statistical significance was analyzed using one-way (graph B, D and E) or two-way (graph C) ANOVA. ∗p ≤ 0.05.

Analysis of T cells

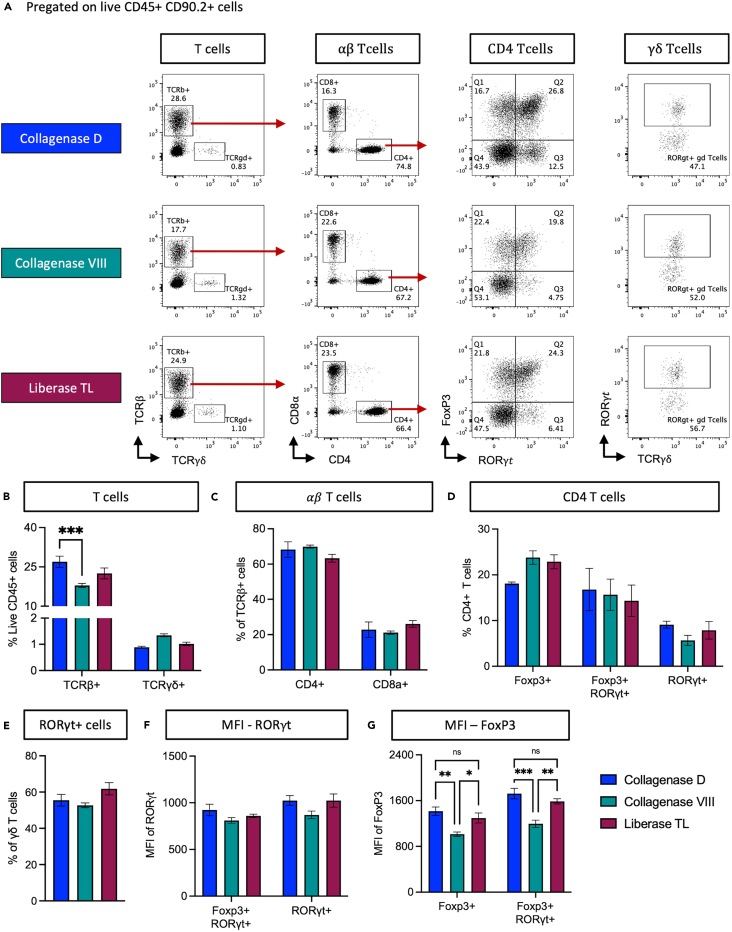

T cells develop in the thymus and together with B cells form the adaptive branch of immune responses. They play critical roles in both health and disease. Together with B cells, myeloid cells and ILCs, T cells are important for containing the commensals, defending against pathogens, and general regulation of the mucosal environment in the intestine.19,20 Dysregulated T cells have been implicated in several intestinal pathologies like colorectal cancer, inflammatory bowel disease and celiac disease.21,22,23 Here, T cells isolated with the different digestion enzymes were analyzed using flow cytometry as shown in Figure 5A. From the live CD45+ total leukocytes, TCRαβ and TCRγδ were used for gating αβ-T cells and γδ-T cells, respectively. αβ-T cells were further divided into CD4+ helper T cells (CD4+) and CD8+ cytotoxic T cells (CD8α+). Helper T cells are the major subtype of CD4+ T cells found in the intestinal LP during homeostasis. From the CD4 subpopulation, regulatory T cells (FoxP3+ Tregs), microbiota induced peripheral regulatory T cells (RORγt+ FoxP3+), and IL-17 producing Th17 cells (RORγt+) were identified using FoxP3 and RORγt expression. From the total γδ-T cells, IL-17-producing cells were identified based on RORγt transcription factor expression.

Figure 5.

T cell marker retention is better with Collagenase D based enzymatic digestion

After isolating total colonic-LP cells, we focused on T cells and their subtypes based on the expression of surface receptors and transcription factors.

(A) Comparison of the gating strategy in randomly chosen samples from the three enzyme groups (Collagenase D, Collagenase VIII, and Liberase TL). From live CD45+ leukocytes, subsets were defined by expression of surface receptors to distinguish αβ-T cells and γδ-T cells. The αβ-T cells were further classified into subtypes using CD4 and CD8α surface expression. CD4 T cells were further grouped based on their transcription factor expression profile into FoxP3+ Tregs, RORγt+ FoxP3+ peripheral Tregs, and RORγt+ Th17 cells.

(B) Based on the gating, the frequencies of the subtypes of T cells, namely αβ-T cells and γδ-T cells are as shown.

(C) Frequencies of CD4 and CD8 T cells among all αβ T cells.

(D) Subtypes of CD4 T cells were grouped based on transcription factors into Tregs, peripheral Tregs, and Th17 cells.

(E) γδ T cell expression of transcription factor RORγt.

(F and G) show the MFI of RORγt and FoxP3, respectively, among the subpopulations from D. Values represent mean frequencies +/− SEM (n = 4/group). While there is no significant difference in percentages or absolute cell numbers between the T cell subtypes after isolation using three different enzymes (B-E), collagenase D digestion results in better retention of marker expression. This is evidenced by reduced transcription factor expression shown in figures F and G when compared to samples isolated using Collagenase VIII. Statistical significance was analyzed using one-way (graph E) or two-way (graph B, C, D, F and G) ANOVA. ∗p ≤ 0.05; ∗∗p ≤ 0.01; ∗∗∗p ≤ 0.001.

Comparative analysis of the subtypes of αβ-T cells and γδ-T cells showed that Collagenase D yielded a significantly higher frequency of αβ-T cells, compared to Collagenase VIII or Liberase TL (Figure 5B). While there were no significant changes in the frequencies (Figures 5C–5E) or cell numbers (not shown) of the subtypes of αβ-T cells and γδ-T cells, the MFI of transcription factors is altered when the samples were digested using Collagenase VIII (Figures 5F and 5G). This might be due to the lower clostripain and trypsin activity of Liberase TL and Collagenase D, compared to Collagenase VIII, as well as the activation of genes by digestion enzymes as previously discussed by other research groups.24,25 Digestion enzymes may also alter the pH and metabolism of the cells. Collectively, these data identify Collagenase D as the best choice for the enzymatic digestion of intestinal tissue for the analysis of T cells.

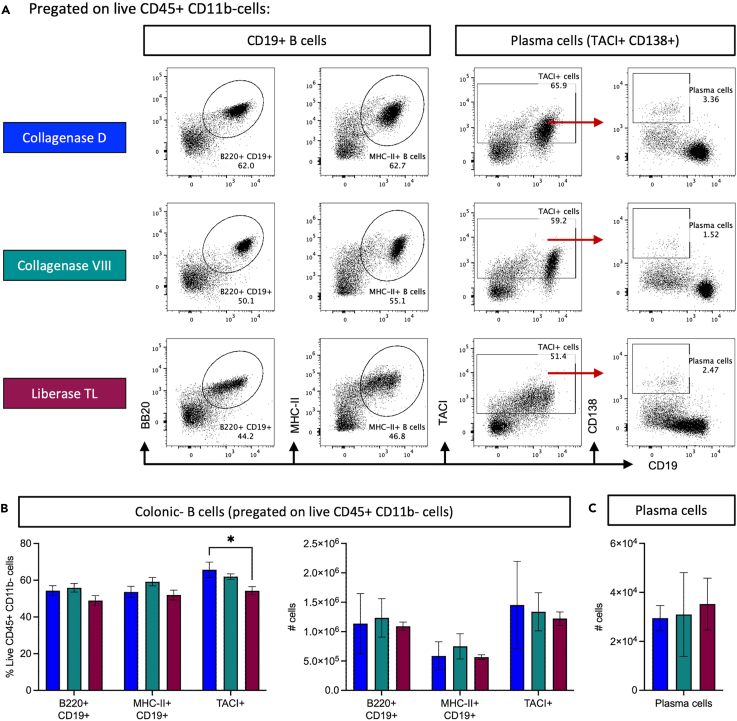

Analysis of B cells

Similar to T cells, B cells are adaptive lymphocytes that develop from the common lymphoid progenitor. Unlike T cells, these cells develop in the bone marrow and migrate to the lymphoid and non-lymphoid tissues to support tissue organization, homeostasis, and protect against pathogens. B cells can eventually mature into antibody-secreting plasma cells. In the intestine, plasma cells secreting IgA are critical for gut homeostasis.20,26,27 To study if the enzymes used for digestion of the intestinal LP affect the isolation efficiency of B cells, we analyzed B cells from single cell suspensions isolated using the three different digestion enzymes. As shown in Figure 6A, from Live CD45+ CD11b- cells, CD19+ B cells are gated using either B220 or type-II MHC co-expression. From the TACI+ cells, plasma cells are gated as CD19- cells that are CD138+. Comparative analysis of the different populations showed that Collagenase D and VIII digestions yielded more B cells compared to Liberase TL in both frequencies as well as absolute cell numbers (Figure 6B). In contrast, plasma cells remain unaltered irrespective of the digestion enzyme (Figure 6C). However, as clearly seen in Figure 6A, cells from Liberase TL digestion show reduced CD19 staining, due to a possible partial cleavage of the epitope, resulting in a very variable CD19 expression compared to cells isolated using Collagenase D or Collagenase VIII. Thus, we suggest using Collagenase D or Collagenase VIII for the isolation of B cells.

Figure 6.

B cells can be efficiently isolated using Collagenase D and VIII

To compare the efficacy of different digestion enzymes in isolating colonic-B cells (CD19+) and plasma cells (TACI+ CD138+ cells), we compared cells obtained using three commonly used digestion enzymes (Collagenase D, Collagenase VIII, and Liberase TL) for isolating intestinal leukocytes. Following the isolation of live cells, our main focus was on examining the CD45+ CD11b- cells. These cells were subjected to a series of further analyses based on surface receptor expression to identify and characterize the intestinal B cells and plasma cells.

(A) The comparison of gated cells among the three enzymatic digestion protocols revealed no significant differences. From pre-gated live CD45+ CD11b- cells, we gated on B cells using B220 and MHC-II expression. To gate on plasma cells, the cells were first gated on TACI-positive cells and from these, CD138+ plasma cells were identified.

(B) Calculated frequencies and absolute cell numbers of the B cells gated in A from the live CD45+ CD11b- cells.

(C) Absolute cell numbers of plasma cells in the colonic-LP isolated using three different digestion enzymes (CD19- TACI+ CD138+ cells). Comparison of cell frequencies and absolute numbers clearly shows that Collagenase D and Collagenase VIII have better and more efficient B cell isolations. While there is no significant difference in the cell numbers, CD19 has better staining as seen in Fig A. when Collagenase D or VIII was used for the tissue digestion. The graphs depict absolute cell numbers as mean ± SEM (n = 4/group) and statistical significance was analyzed using one-way (graphs C) or two-way (graph B) ANOVA. ∗p ≤ 0.05.

Analysis of myeloid cells

The intestinal LP houses an extensive network of immune cells to protect against constant exposure to both harmless and pathogenic microbes and foreign particles. Myeloid cells, including macrophages, monocytes, neutrophils, and dendritic cells (DCs) are the intestine’s first line of defense against said pathogens. These cells express pattern recognition receptors against microbe and pathogen-associated molecular patterns, which can include toll-like (TLRs) and nucleotide oligomerization domain (NOD)like (NLRs) receptors that innately identify pathogens. To study the various myeloid cells in the intestine and whether they are affected by the choice of digestion enzymes, we stained and analyzed cells from the intestinal LP using common myeloid cell markers. From the total live CD45+ cells, neutrophils (CD11b+ Ly6G+) are gated out and the remaining CD11b+ cells are used to create a monocyte waterfall by gating Ly6C vs. MHC-II (Figure 7A). Using this gating strategy, macrophages and type 2 conventional dendritic cells (cDC2s) (MHC-II+ Ly6C-), mature monocytes (MHC-II+ Ly6C+) and immature monocytes (MHC-II- Ly6C+) can be classified. Dendritic cells (CD11c+ MHC-II+) are directly gated from the total live cells and cDC1s and cDC2s are further classified by their negative or positive expression of CD11b, respectively (Figure 7A). Comparative analysis of all the gated populations shows no significant alterations in cell numbers (data not shown) or frequencies (Figures 7B–7D). Thus, all the three enzymes can be used for studying myeloid cells in the intestinal LP. However, one needs to keep in mind that these are the most common markers and were used to obtain an overview of the major populations, but a more detailed and in-depth analysis of the different subsets requires more complex flow cytometry staining panels. However, if and how such additional markers might be altered by the choice of digestion enzyme still needs to be evaluated.

Figure 7.

Myeloid cells are not preferentially affected by any digestion enzyme

To evaluate the efficiency of various digestion enzymes in isolating myeloid cells, we compared cells obtained using commonly employed digestion enzymes (Collagenase D, Collagenase VIII, and Liberase TL) for isolating intestinal leukocytes. Following isolation, our focus was on live CD45+ cells. Subsequently, these cells underwent further analysis involving gating based on surface receptors and marker expressions.

(A) The comparison of gated cells among the three enzymatic digestion protocols revealed no significant differences. Beginning with live CD45+ cells, we gated on myeloid cells using CD11b (macrophages and monocytes) and Ly6G (neutrophils). From the CD11b+ population, we further analyzed macrophages (CD11b+ MHC-II + Ly6C-) using MHC-II and Ly6C markers. Additionally, the total live CD45+ CD90.2- population was utilized to identify conventional dendritic cells (cDCs) (MHC-II+ CD11c+), further sub-grouped into cDC1s (CD11b-) and cDC2s (CD11b+).

(B) Calculated frequencies of the different myeloid cells from the live CD45+ CD90.2- cells.

(C) Subtypes among the CD11b+ cells based on their expression of MHC-II and Ly6C.

(D) Subtypes of CD11c+ MHC-II + cDCs based on CD11b expression. Comparative analysis among the three different enzymes clearly shows that Collagenase D has an elevated neutrophil population, but no other significant differences were found either in terms of population frequencies or absolute cell numbers. The graphs depict absolute cell numbers as mean ± SEM (n = 4/group) and statistical significance was analyzed using two-way ANOVA.

Limitations

One of the major limitations of isolating intestinal immune cells lies in ensuring their viability for downstream processing. When sorted cells are intended for use in culture or sequencing, the primary goal of the isolation process should be to maintain cell viability. In addition to the considerations suggested in troubleshooting, it is important to note that the overall digestion process itself can be stressful and damaging to the cells. A density gradient that is designed for leukocyte enrichment (recommended in the protocol as the Percoll step) was omitted for the same reason. Therefore, if the intention is to use cells for sorting or sequencing, it is recommended to keep them in 10% FCS media as much as possible after the digestion process.

Another significant limitation of this protocol arises when using Liberase TL for cell digestion. As depicted in Figure 6A, there is a loss of epitope, evident in CD19 staining, resembling more of a smear than an isolated population compared to cells from Collagenase D or VIII digestion. Liberase TL also yields ineffective staining of plasma cells isolated from small intestinal LP (Figure 8A). Similarly, T cells isolated from the small intestinal LP using Liberase TL often exhibit CD8 cleavage (Figure 8B). This underscores that Liberase TL is not an optimal choice for studies focused on B and T cells.

Figure 8.

Isolation efficiency of lymphocytes is strongly influenced by the choice of the digestion enzyme and depends on the abundance of the cells

(A) Plasma cells isolated from small intestine LP using Liberase TL and Collagenase VIII. Splenic plasma cells are shown as a positive control. This graph clearly shows that Liberase TL digestion cleaves the sensitive epitopes of plasma cells in the SI-lamina propria.

(B) Liberase-TL also cleaves the CD8 epitopes on T cells in the small intestine LP as shown in the graph. Similarly gated cells from Collagenase D digestion of SI-LPL, clearly shows that the CD8 epitope is cleaved by Liberase TL, but not Collagenase D. Both A and B show that the cells in the small intestine behave differently to enzymatic digestion. This could be attributed to the increased enzyme volume in the digestion mix or the presence of excessive cells, allowing reduced access to the epitopes. While the reason needs elucidation, it clearly must be considered while choosing enzymes for an isolation protocol for intestinal leukocytes.

Despite the provided tips and troubleshooting, the age of the mice inevitably has a profound impact on the efficiency of the isolation protocol and the viability of the isolated cells. Collagenase VIII appears to be the most effective when isolating cells from the tissues of older mice. For researchers planning to investigate the immune landscape of the intestinal LP, it is advisable to consider these aforementioned strengths and limitations before making a choice, based on the specific requirements of the experiment, and tailoring the enzyme selection accordingly to the cells of interest.

Troubleshooting

Problem 1

Samples have low cell viability (Step 21).

Potential solution

Three main factors affect final cell viability: 1) the presence of mesenteric fat, 2) time from death to single cell suspension, and 3) age of the mice. The paradox of this protocol lies in the aim for both efficiency in fat removal and speed. Additionally, older mice have lower cell viability. It is recommended to work with mice as young as possible, preferably between 6 and 12 weeks. If this is not possible, it may be advisable to use the collagenase VIII digestion protocol, as this protocol works better and gives a higher viability in aged mice (mice older than 6 months) compared to Collagenase D or Liberase TL.

Problem 2

Samples do not flow through the cell strainers after digestion, due to clogging of the filters (Step 15).

Potential solution

This occurs for 3 main reasons: 1) too much fat remaining on the tissue after cleaning, 2) too many epithelial cells remaining after stripping, or 3) improper cutting of the tissue before digestion (See Figure 2). To avoid clogging due to excess fat, the tissue must be cleaned very well, and all the residual mesenteric fat must be removed. As epithelial cells are a very sticky cell type, an additional stripping step is recommended to avoid the presence of these cells consequently clogging the filters later in the protocol.

Problem 3

Small cell pellet / Low cell numbers (step 19 and step 23).

Potential solution

Wash all sieves, filters, and plungers used during the protocol thoroughly as intestinal cells are adhesive to surfaces. Ensure that centrifugation steps are adapted to the centrifuge available and make sure that cells are pelleted solidly each time. Keep in mind that the enzyme of choice should be considered in the yield of final cell numbers.

Problem 4

Weak staining of intranuclear proteins (step 32).

Potential solution

Ensure that the proper fixation kit is used. We suggest usage of the eBioscience Foxp3 kit. Since the permeabilization buffer in this kit can permeabilize the nuclear membrane, it allows access for the antibodies targeting transcription factors to enter the nucleus. Hint: if transgenic mice expressing fluorescent proteins are used, 2% formaldehyde can be used for fixing the cells to preserve the fluorescent protein expression. The intracellular staining can be done with antibodies diluted in the permeabilization buffer.28

Problem 5

Turbid single cell suspensions (step 34).

Potential solution

The gut is an extremely sticky tissue. Increase the concentration of EDTA (suggested maximum concentration of 10 mM) and DNase I (suggested maximum concentration of 50 μg/mL) to the FACS buffer II. If FACS sorting is the aim, also increase the concentration of FCS (10% or higher) and dilute the samples.

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contacts, Tommy Regen (regen@uni-mainz.de) and Ari Waisman (waisman@uni-mainz.de).

Technical contact

Further information on technical details, resources, and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the technical contact, Arthi Shanmugavadivu (arthi.shanmugavadiviu@vib.be).

Materials availability

This study did not generate new unique reagents.

Data and code availability

This study did not generate/analyze data sets/codes.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Dominika Lukas from the lab of Prof. Dr. Georg Gasteiger, Dr. Konrad Gronke from the lab of Prof. Dr. Andreas Diefenbach, and Dr. Alexander Kazakov from the lab of Prof. Dr. Christoph Wilhelm for their initial guidance and support in teaching the isolation techniques used in their respective labs (Collagenase D and Liberase TL-based protocols). We thank Dr. Elena Kotsiliti from the lab of Prof. Dr. Mathias Heikenwälder for sharing the primary collagenase isolation protocol. This work was supported by the German Research Foundation (DFG), Collaborative Research Center SFB TR355/1 (project number 490846870) to T.R. and A.W.

Author contributions

A.S. conceptualized the study and standardized the isolation technique. A.S., K.C., and A.P.Z. optimized the protocols, performed the experiments, and analyzed the results. A.S. and K.C. wrote the manuscript and constructed the figures. K.C. and A.P.Z. recorded the videos. A.P.Z. created the graphical abstract. T.R. and A.W. supervised the work. All the authors commented on and edited the manuscript.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xpro.2024.103154.

Contributor Information

Arthi Shanmugavadivu, Email: arthi.shanmugavadivu@vib.be.

Tommy Regen, Email: regen@uni-mainz.de.

Supplemental information

References

- 1.Hunyady B., Mezey E., Palkovits M. Gastrointestinal immunology: cell types in the lamina propria--a morphological review. Acta Physiol. Hung. 2000;87:305–328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mazzucchelli L., Maurer C. Encyclopedia of Gastroenterology. Elsevier; 2004. Colon, Anatomy; pp. 408–412. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jung C., Hugot J.-P., Barreau F. Peyer’s Patches: The Immune Sensors of the Intestine. Int. J. Inflam. 2010;2010:823710–823712. doi: 10.4061/2010/823710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sasso J.M., Ammar R.M., Tenchov R., Lemmel S., Kelber O., Grieswelle M., Zhou Q.A. Gut Microbiome-Brain Alliance: A Landscape View into Mental and Gastrointestinal Health and Disorders. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2023;14:1717–1763. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.3c00127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Muhammad F., Fan B., Wang R., Ren J., Jia S., Wang L., Chen Z., Liu X.A. The Molecular Gut-Brain Axis in Early Brain Development. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022;23 doi: 10.3390/ijms232315389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reißig S., Hackenbruch C., Hövelmeyer N. Isolation of T Cells from the Gut. Methods Mol. Biol. 2014;1193:21–25. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-1212-4_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gronke K., Kofoed-Nielsen M., Diefenbach A. Isolation and Flow Cytometry Analysis of Innate Lymphoid Cells from the Intestinal Lamina Propria. Methods Mol. Biol. 2017;1559:255–265. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-6786-5_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pascal M., Kazakov A., Chevalier G., Dubrule L., Deyrat J., Dupin A., Saha S., Jagot F., Sailor K., Dulauroy S., et al. The neuropeptide VIP potentiates intestinal innate type 2 and type 3 immunity in response to feeding. Mucosal Immunol. 2022;15:629–641. doi: 10.1038/s41385-022-00516-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Autengruber A., Gereke M., Hansen G., Hennig C., Bruder D. Impact of enzymatic tissue disintegration on the level of surface molecule expression and immune cell function. Eur. J. Microbiol. Immunol. 2012;2:112–120. doi: 10.1556/EuJMI.2.2012.2.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Campbell C., Kandalgaonkar M.R., Golonka R.M., Yeoh B.S., Vijay-Kumar M., Saha P. Crosstalk between Gut Microbiota and Host Immunity: Impact on Inflammation and Immunotherapy. Biomedicines. 2023;11 doi: 10.3390/biomedicines11020294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shi N., Li N., Duan X., Niu H. Interaction between the gut microbiome and mucosal immune system. Mil. Med. Res. 2017;4:14. doi: 10.1186/s40779-017-0122-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shoubridge A.P., Choo J.M., Martin A.M., Keating D.J., Wong M.-L., Licinio J., Rogers G.B. The gut microbiome and mental health: advances in research and emerging priorities. Mol. Psychiatry. 2022;27:1908–1919. doi: 10.1038/s41380-022-01479-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang Z., Chen B., Liu X., Li H., Xie L., Gao Y., Duan R., Li Z., Zhang J., Zheng Y., Su W. Effects of sex and aging on the immune cell landscape as assessed by single-cell transcriptomic analysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2021;118 doi: 10.1073/pnas.2023216118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klein S.L., Flanagan K.L. Sex differences in immune responses. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2016;16:626–638. doi: 10.1038/nri.2016.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Whyte C.E., Tumes D.J., Liston A., Burton O.T. Do more with Less: Improving High Parameter Cytometry Through Overnight Staining. Curr. Protoc. 2022;2 doi: 10.1002/cpz1.589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Singh R.K., Chang H.-W., Yan D., Lee K.M., Ucmak D., Wong K., Abrouk M., Farahnik B., Nakamura M., Zhu T.H., et al. Influence of diet on the gut microbiome and implications for human health. J. Transl. Med. 2017;15:73. doi: 10.1186/s12967-017-1175-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vivier E., Artis D., Colonna M., Diefenbach A., Di Santo J.P., Eberl G., Koyasu S., Locksley R.M., McKenzie A.N., Mebius R.E., et al. Innate Lymphoid Cells: 10 Years On. Preprint at Cell Press. 2018;174:1054–1066. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hepworth M.R., Monticelli L.A., Fung T.C., Ziegler C.G.K., Grunberg S., Sinha R., Mantegazza A.R., Ma H.L., Crawford A., Angelosanto J.M., et al. Innate lymphoid cells regulate CD4 + T-cell responses to intestinal commensal bacteria. Nature. 2013;498:113–117. doi: 10.1038/nature12240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bauché D., Joyce-Shaikh B., Jain R., Grein J., Ku K.S., Blumenschein W.M., Ganal-Vonarburg S.C., Wilson D.C., McClanahan T.K., Malefyt R.d.W., et al. LAG3 + Regulatory T Cells Restrain Interleukin-23-Producing CX3CR1 + Gut-Resident Macrophages during Group 3 Innate Lymphoid Cell-Driven Colitis. Immunity. 2018;49:342–352.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang L., Ray A., Jiang X., Wang J.y., Basu S., Liu X., Qian T., He R., Dittel B.N., Chu Y. T regulatory cells and B cells cooperate to form a regulatory loop that maintains gut homeostasis and suppresses dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis. Mucosal Immunol. 2015;8:1297–1312. doi: 10.1038/mi.2015.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jabri B., Sollid L.M. T Cells in Celiac Disease. J. Immunol. 2017;198:3005–3014. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1601693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zheng Z., Wieder T., Mauerer B., Schäfer L., Kesselring R., Braumüller H. T Cells in Colorectal Cancer: Unravelling the Function of Different T Cell Subsets in the Tumor Microenvironment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023;24 doi: 10.3390/ijms241411673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gomez-Bris R., Saez A., Herrero-Fernandez B., Rius C., Sanchez-Martinez H., Gonzalez-Granado J.M. CD4 T-Cell Subsets and the Pathophysiology of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023;24:2696. doi: 10.3390/ijms24032696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Uniken Venema W.T.C., Ramírez-Sánchez A.D., Bigaeva E., Withoff S., Jonkers I., McIntyre R.E., Ghouraba M., Raine T., Weersma R.K., Franke L., et al. Gut mucosa dissociation protocols influence cell type proportions and single-cell gene expression levels. Sci. Rep. 2022;12:9897. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-13812-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schreurs R.R.C.E., Drewniak A., Bakx R., Corpeleijn W.E., Geijtenbeek T.H.B., van Goudoever J.B., Bunders M.J. Quantitative comparison of human intestinal mononuclear leukocyte isolation techniques for flow cytometric analyses. J. Immunol. Methods. 2017;445:45–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2017.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reboldi A., Arnon T.I., Rodda L.B., Atakilit A., Sheppard D., Cyster J.G. Mucosal immunology: IgA production requires B cell interaction with subepithelial dendritic cells in Peyer’s patches. Science. 2016;1979:352. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf4822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu Y., Rhoads J. Communication between B-Cells and Microbiota for the Maintenance of Intestinal Homeostasis. Antibodies. 2013;2:535–553. doi: 10.3390/antib2040535. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heinen A.P., Wanke F., Moos S., Attig S., Luche H., Pal P.P., Budisa N., Fehling H.J., Waisman A., Kurschus F.C. Improved method to retain cytosolic reporter protein fluorescence while staining for nuclear proteins. Cytometry A. 2014;85:621–627. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.22451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

This study did not generate/analyze data sets/codes.