Abstract

Excessive compression after parotidectomy can lead to flap necrosis, while inadequate pressure can cause fluid accumulation. This study aimed to determine the optimal pressure and compression properties of different types of dressings. Initially, pressure measurements were taken for conventional Barton's dressing and a pre‐fabricated facial garment. In the subsequent phase, patients were randomly assigned to receive one of three types of pressure dressings: conforming bandage Barton's dressing, elastic bandage Barton's dressing or pre‐fabricated facial garment. The dressing types were randomly crossed over the following day. The mean pressure exerted by conventional Barton's dressing and the pre‐fabricated facial garment was 15.86 and 14.81 mmHg, respectively. There was no significant difference in the proportion of optimal pressure among the three types of pressure dressing (p‐values of 0.195, 0.555 and 0.089 at pre‐auricular, angle of mandible and post‐auricular sites, respectively). The pre‐auricular area demonstrated the highest proportion of optimal pressure, while suboptimal pressure was noted at the angle of the mandible and post‐auricular area. Dressing types had no effect on pressure stability (p = 0.37), and there was no significant difference in patient preference (p = 0.91). Conforming bandage Barton's dressing, elastic bandage Barton's dressing and pre‐fabricated facial garment exhibit comparable compressive properties, with no significant difference in patient preference and pressure stability.

Keywords: Barton's dressing, hematoma, parotidectomy, seroma, skin flap necrosis

1. INTRODUCTION

The parotid gland, constituting the largest major salivary gland, is frequently afflicted by salivary gland tumours, rendering it a pivotal site for surgical intervention. Post‐parotidectomy, meticulous wound management becomes imperative to prevent potential complications. Barton's dressing encompasses a non‐adherent bandage layered with absorbent material and stretchable adhesive, meticulously applied to compress dead space and forestall haematoma and seroma formation. 1 However, a notable challenge arises in the form of skin necrosis, often stemming from inadequate tissue perfusion along the flap's periphery, with a predilection for ischaemic injury, particularly pronounced in prominent areas. 2 , 3

Traditional pressure dressings, while effective, are subject to operator variability and patient discomfort. They may shift or lose elasticity, compromising their compressive function and causing discomfort, especially in warm climates. 4 , 5 , 6 Furthermore, their frequent removal for wound assessment disrupts the healing continuum.

In response, commercial compression garments have emerged, 7 , 8 designed to offer consistent pressure without impeding patient comfort or mobility. By proffering advantages such as facilitating uninterrupted sleep and mouth opening, coupled with reusability, thus addressing several drawbacks associated with traditional dressings.

While studies have outlined optimal pressure ranges for various body areas, limited data exist concerning the ideal compressive pressure for parotidectomy skin flaps. This study aims to compare the pressure efficacy and stability between traditional Barton's dressing using conforming bandage and pre‐fabricated commercial garments. providing valuable insights for post‐parotidectomy care.

A study on capillary pressure of the upper extremity at the heart level revealed that appropriate pressure should be from 10.5 to 22.5 mmHg. 9 While parotid dressing was applied at higher location over bony prominences, such as the temporomandibular joint, mandibular ramus and mastoid process. Pressure above these areas may require less than extremities. 10 Limited data exist concerning the ideal compressive pressure for parotidectomy skin flaps. This study aims to compare pressure efficacy and stability between traditional Barton's dressing and pre‐fabricated commercial garments, providing valuable insights for post‐parotidectomy care.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study consisted of two phases. Initially, 10 participants were enrolled in the first phase. Standardized methods for pressure measurement were employed, with targeted compression pressure ranging between 10.5 and 22.5 mmHg. 9 Pressure over the skin was assessed using both conventional Barton's dressing and a commercial facial garment. The mean and standard pressure differences were utilized to calculate the sample size required for a non‐inferiority trial in the second phase.

In the second phase of the study, 20 patients aged over 18 years who were scheduled for parotidectomy were recruited. Patients with poor‐quality facial skin or those who underwent other types of skin incisions were excluded. Comprehensive data including demographic profiles, compression pressure parameters and postoperative clinical records were documented. Each patient underwent random allocation to different types of pressure dressings: conforming bandage Barton's dressing, elastic bandage Barton's dressing and pre‐fabricated facial garment. The dressings were alternated in a randomized sequence on subsequent days (e.g., ABC, BCA, CAB, BAC, CBA, etc.). The patients were unaware of the types and sequence of parotid dressing on the first day post‐operatively. However, they were informed afterwards and could compare the current type of dressing with the previous one.

In general, a pressure dressing is applied by placing a layer of rose‐shaped gauze—formed by folding 4 × 4 “gauze into the shape of a rose—over the skin flap and securing it with elastic materials.” The Barton's method involves wrapping the dressing garment layer by layer around the patient's head using either a conforming or elastic bandage. In contrast, a pre‐fabricated garment is an elastic wrap that is ready to use. Continuous monitoring of compression pressure was conducted at specific anatomical points, including the pre‐auricular, angle of mandible and post‐auricular areas. Pressure sensors were positioned beneath a layer of rose‐shaped gauze, which was subsequently covered with different types of bandages. Real‐time pressure monitoring was implemented and recorded onto a microSD card. Following monitoring, pressure dressings remained applied for an additional 24 h. After all 20 patients were included, VAS scores and pressure measurements were processed by the author “NN,” a non‐physician researcher. Optimal pressure was defined as maintaining pressure within the targeted range for a certain duration compared with the total recording time. Instances of pressure falling below 10.5 mmHg or exceeding 22.5 mmHg were categorized as under‐pressure and over‐pressure, respectively. The proportions of under‐pressure and over‐pressure were calculated using a similar method as that employed for determining optimal pressure.

The preference for dressing types was assessed using a visual analogue scale. Additionally, post‐operative adverse events related to each dressing type, such as delayed facial nerve impairment and wound complications, were carefully documented. Approval for the study was obtained from the Institutional Review Board (SIRB), COA no. Si 686/2020 and COA no. Si 199/2021. The study was conducted at a tertiary hospital from September 2020 to November 2021.

The categorical data were presented as numbers (percentage). Continuous data were described using mean and standard deviation (SD) for parametric variables, while median and interquartile range (IQR) were used for non‐parametric variables. The proportions of optimal pressure, under‐pressure and over‐pressure were compared using the Friedman test. Pressure stabilities were assessed using the Kruskal–Wallis test for non‐parametric data. The results were analysed according to the intention‐to‐treat principle. Data analysis was conducted using SPSS version 22.0 for Windows. A p‐value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. RESULTS

The mean pressure exerted by conventional Barton's dressing and the commercial garment was 15.86 and 14.81 mmHg, respectively. Baseline patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The proportion of optimal pressure across three dressing groups in three different areas is presented in Table 2. Statistical analysis revealed no significant difference in the proportion of optimal pressure among the three types of dressing (p‐value = 0.195, 0.555 and 0.089) at the pre‐auricular area, angle of the mandible and post‐auricular area, respectively. Furthermore, no significant difference in the proportion of over‐ and under‐pressure was observed among the three types of dressing, as detailed in Table 2. Pressure stability, calculated using the interquartile difference, also showed no significant different, as indicated in Table 3.

TABLE 1.

Baseline characteristics of 20 patients.

| Mean ± SD or n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Weight, kg | 64.9 ± 15.8 |

| Height, cm | 163.2 ± 9.4 |

| Axial head circumference, cm | 55.5 ± 2.4 |

| Coronal head circumference, cm | 64.3 ± 3.0 |

| Procedure | |

| Rt. Superficial parotidectomy | 6 (30) |

| Lt. Superficial parotidectomy | 7 (35) |

| Rt. Total parotidectomy | 3 (15) |

| Lt. Total parotidectomy | 4 (20) |

TABLE 2.

Comparison in percent of pressure and VAS among three types of dressing.

| Type of pressure dressing | p‐value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conform Barton's dressing | Elastic bandage Barton's dressing | Commercial facial garment | ||

| Percent of optimal pressure a | ||||

| Pre‐auricular | 54.3 (26.5, 89.4) | 37.0 (0.2, 77.3) | 33.2 (11.6, 70.6) | 0.195 |

| Angle of mandible | 3.8 (0, 70.1) | 0.4 (0, 4.1) | 6.6 (0, 26.0) | 0.555 |

| Post‐auricular | 0.2 (0, 58.2) | 0 (0, 20.2) | 2.5 (0, 53.8) | 0.089 |

| Percent of under‐pressure a | ||||

| Pre‐auricular | 0 (0, 1.4) | 0.2 (0, 57.7) | 30.0 (0, 78.8) | 0.135 |

| Angle of mandible | 96.3 (27.7, 100) | 99.6 (95.9, 100) | 93.4 (74.0, 100) | 0.555 |

| Post‐auricular | 99.8 (40.8, 100) | 100 (77.1, 100) | 97.5 (44.8, 100) | 0.115 |

| Percent of over‐pressure b | ||||

| Pre‐auricular | 34.5 (0 to 100) | 8.6 (0 to 100) | 0.5 (0 to 100) | 0.422 |

| Angle of mandible | 0 (0 to 5.9) | 0 (0 to 13.2) | 0 (0 to 22.5) | 0.584 |

| Post‐auricular | 0 (0 to 5) | 0 (0 to 13.3) | 0 (0 to 36.1) | 0.867 |

| Visual analogue scale (VAS) | 7 (5, 9) | 7 (5.3, 9.8) | 7 (4.3, 9.4) | 0.912 |

Note: p‐values were from Friedman test.

Median (P25, P75).

Median (Min to Max).

TABLE 3.

Comparison of pressure stability (interquartile of proportion of pressure).

| Type of pressure dressing | p‐value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conform Barton's dressing (n = 20) | Elastic bandage Barton's dressing (n = 20) | Commercial facial garment (n = 20) | ||

| Interquartile difference of proportion of optimal pressure | ||||

| Pre‐auricular (%) | 60.87 | 77.02 | 59.07 | 0.368 |

| Angle of mandible (%) | 70.08 | 4.11 | 26.04 | |

| Post‐auricular (%) | 58.21 | 20.18 | 53.84 | |

The median (P25, P75) visual analogue scale ratings for conforming bandage Barton's dressing, elastic bandage Barton's dressing and commercial facial garment were 7.0 (5.0, 9.0), 7.0 (5.25, 9.75) and 7.0 (4.25, 9.37), respectively. Patient preference, as assessed by the VAS, did not exhibit significant differences among the three types of pressure dressings, yielding a p‐value of 0.912.

4. DISCUSSION

The maintenance of optimal pressure in parotid dressing is crucial for preventing post‐parotidectomy complications. 9 Specifically, the focus of applied pressure over the skin flap should primarily target the pre‐auricular region, where most tissues are dissected. 11 Conversely, suboptimal pressure over the skin flap may result in ineffective potential space obliteration, potentially leading to complications such as seroma, haematoma and sialocele. 1 , 12 Additionally, excessive pressure may adversely affect skin flap perfusion, 2 particularly in areas where the marginal mandibular nerve traverses superficially to the mandibular ramus.

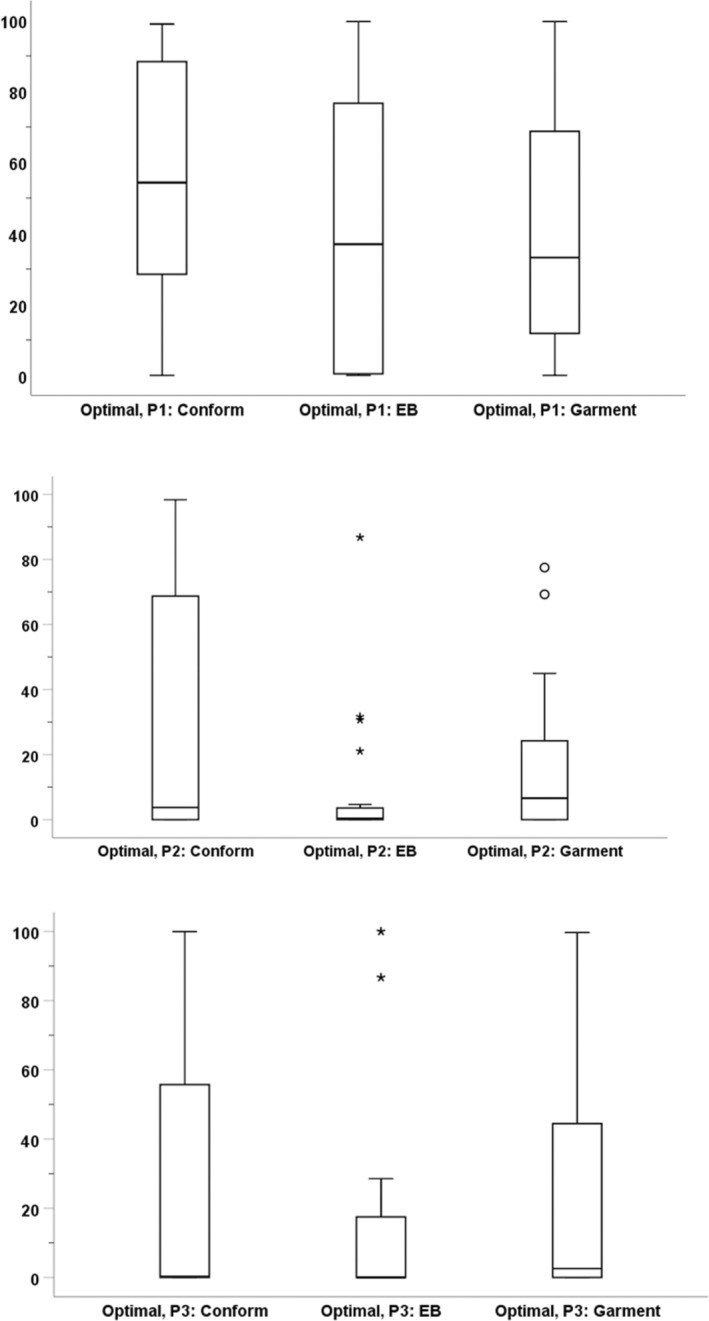

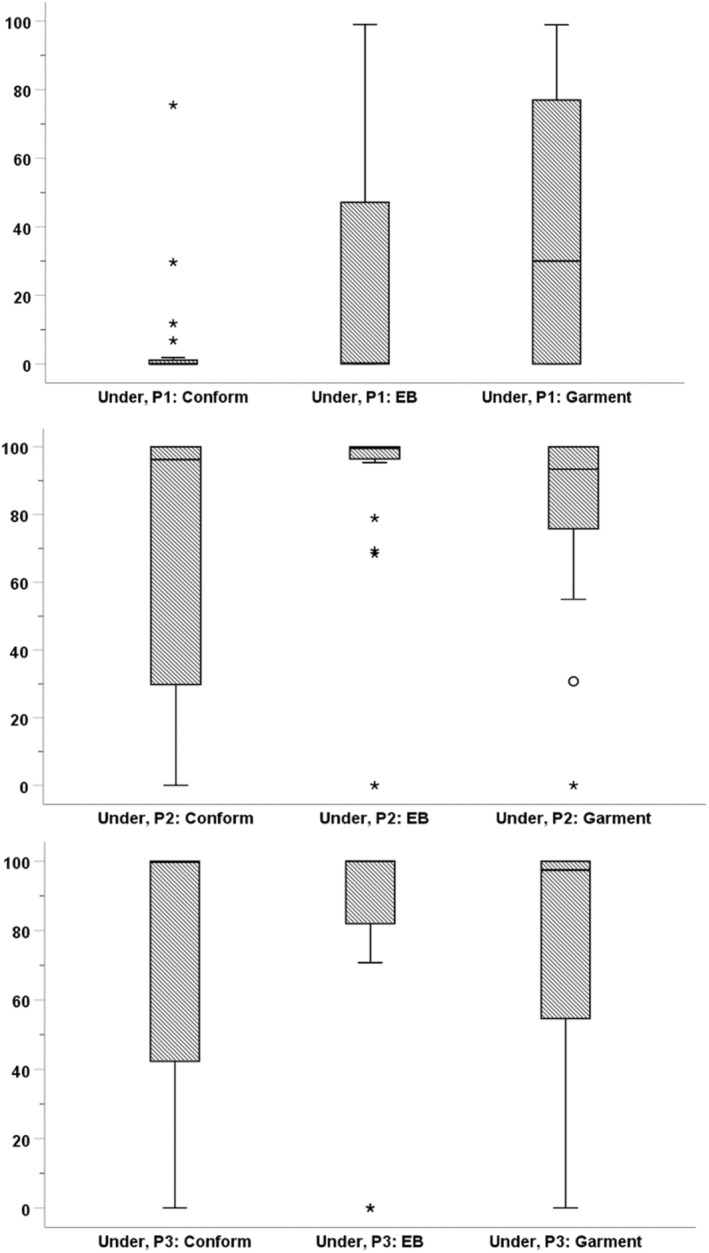

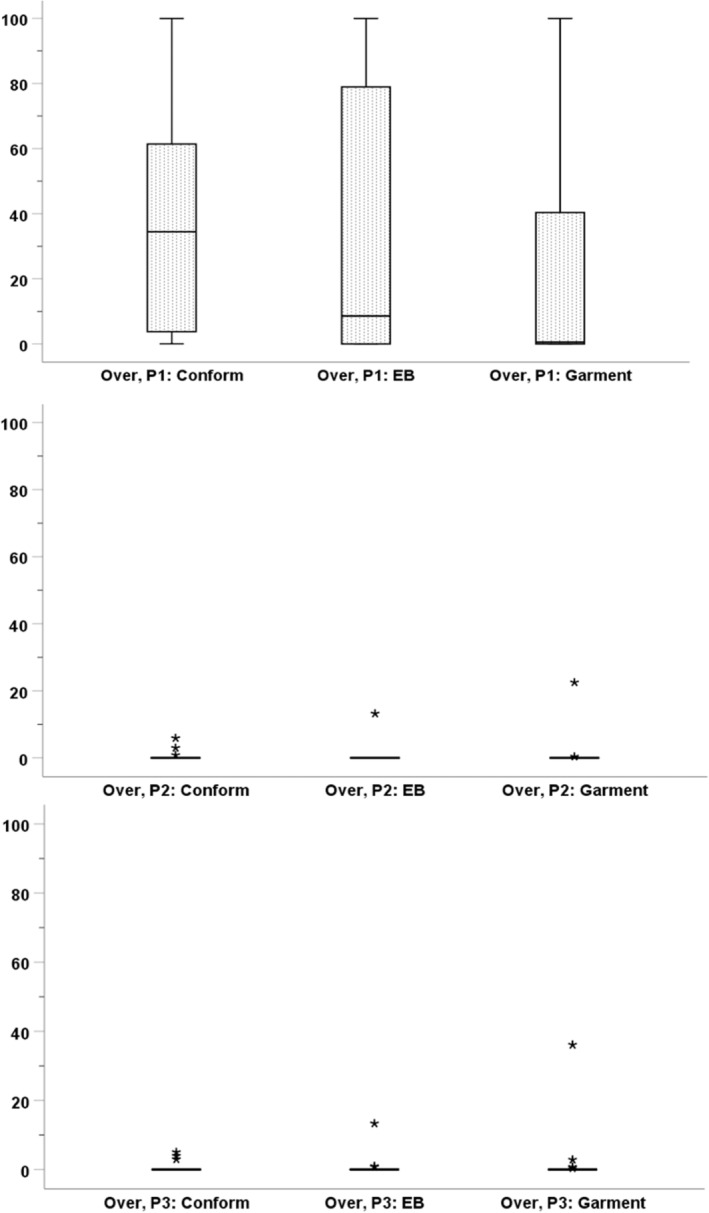

In our study, the highest proportion of optimal pressure was consistently observed at the pre‐auricular area compared with the post‐auricular area and over the angle of the mandible (refer to Figures 1, 2, 3). These findings remained consistent across different types of outer dressing. Among the three types of pressure dressing—conforming bandage Barton's dressing, elastic bandage Barton's dressing and commercial facial garment—no significant difference in the proportion of optimal pressure was found. The p‐values were 0.195, 0.555 and 0.089 at the pre‐auricular area, angle of mandible and post‐auricular area, respectively. Kiuchi et al. previously suggested that optimal pressure at these specific areas could be achieved using a kidney‐shaped cotton pad. 13 In our study, a similar approach was adopted using a free gauze rolled into a rose‐shaped fashion. Standardizing the method of inner gauze alignment could mitigate the risk of inadvertent injury. Our results also indicated lower compression pressure at the angle of mandible and the post‐auricular area (refer to Figures 1, 2, 3).

FIGURE 1.

Whisker box plot of proportion of optimal pressure (%), type of pressure dressing and location.

FIGURE 2.

Whisker box plot of proportion of under‐pressure (%), type of pressure dressing and location.

FIGURE 3.

Whisker box plot of proportion of over‐pressure (%), type of pressure dressing and location.

In this study, only one patient (5%) experienced temporary pre‐auricular swelling, which spontaneously resolved after re‐application of conform Barton's dressing the following day. The incidence of complications in our study was comparable to the 4% post‐parotidectomy hematoma reported by Heo, K.W et al. In their study, pressure dressing was achieved by suture transfixion of silicone sheets over the skin flap. 14 Despite one third of cases experiencing over‐pressure at the pre‐auricular area primarily due to conform Barton's dressing, no associated complications were observed. However, it is worth noting that iatrogenic ischaemic injury from pressure dressing has been reported in parotidectomy patients 2 by Yoon, Y.H. et al.

Currently, there is a lack of standardized wound care protocols for patients undergoing parotidectomy. Moreover, the elasticity of outer garments used in wound care may diminish over time. One of the primary factors influencing stability throughout the day is the position of the patient. Notably, research in cardiac device surgery has shown that pressure exerted by conventional dressings tends to be higher in the supine position compared with the upright position. 8 On the one hand, external objects such as pillows may inadvertently increase pressure if they directly compress the wound. Conversely, neck flexion has been observed to reduce the compressive properties of outer garments. However, our study found no significant difference in pressure stability among the three types of pressure dressing (p‐value 0.368). Real‐time pressure measurements were continuously recorded, and there was no notable variance in pressure stability related to patients' positioning.

In this study, each patient received three types of parotid wound dressings in random sequences, and their satisfaction was assessed using a visual analogue scale. Results showed no significant difference among the three types of pressure dressing (p‐value 0.912). Therefore, the choice of pressure dressing method can be based on surgeon preference. The compressive pressure applied in our study was accurately measured and recorded, with results validated by appropriate techniques and equivalent types of surgical dressing. However, it is recommended to conduct further studies with a larger sample size to explore post‐parotidectomy complications in relation to different types of compressive pressure dressing.

5. CONCLUSION

The compressive properties of both types of elastic bandage dressing and pre‐fabricated facial garment are comparable. Overall, compression pressure remained within optimal ranges with good stability. Patient preference did not significantly differ among the types of dressing, and no notable complications related to these pressure dressings were observed.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This research project was supported by the Faculty of Medicine Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University, Grant Number (IO) R016431009.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Our grateful appreciation was expressed to Assist. Prof. Dr. Chulaluk Komoltri, Ms. Julaporn Pooliam, our consulting statistician, and all patients who were involved in this study, and Ms. Jeerapa Kerdnoppakhun for assistance with manuscript preparation.

Kertpholwattana S, Pongsapich W, Ratanaprasert N, Ngamying N, Thamaphat K. Comparative study of optimal compression pressure between conventional Barton's dressing and prefabricate garment in parotidectomy patients. Int Wound J. 2024;21(7):e70005. doi: 10.1111/iwj.70005

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1. Kontos M, Petrou A, Prassas E, et al. Pressure dressing in breast surgery: is this the solution for seroma formation? J BUON. 2008;13:65‐67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Yoon YH, Park JY, Choi JW, Koo BS. Iatrogenic ear lobule ischemic injury from pressure dressing as an unusual complication of parotidectomy. Am J Otolaryngol. 2008;29:361‐362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Powell BW. The value of head dressings in the postoperative management of the prominent ear. Br J Plast Surg. 1989;42:692‐694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wax M, Tarshis L. Post‐parotidectomy fistula. J Otolaryngol. 1991;20:10‐13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Corcione F, Califano L. Treatment of parotid gland tumors. Int Surg. 1990;75:171‐173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ragno JR Jr, Nespeca JA. A postsurgical pressure dressing technique. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1988;65:165‐166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Shi C, Dumville JC, Cullum N, Connaughton E, Norman G. Compression bandages or stockings versus no compression for treating venous leg ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021;7:CD013397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kiuchi K, Okajima K, Tanaka N, et al. Novel compression tool to prevent hematomas and skin erosions after device implantation. Circ J. 2015;79:1727‐1732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Shore AC. Capillaroscopy and the measurement of capillary pressure. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2000;50:501‐513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tantawy SA, Abdelbasset WK, Nambi G, Kamel DM. Comparative study between the effects of Kinesio taping and pressure garment on secondary upper extremity lymphedema and quality of life following mastectomy: a randomized controlled trial. Integr Cancer Ther. 2019;18:1534735419847276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yamashita T, Tomoda K, Kumazawa T. The usefulness of partial parotidectomy for benign parotid gland tumors. A retrospective study of 306 cases. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl. 1993;500:113‐116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jianjun Y, Haofu W, Yanxia C, et al. A device for applying postsurgical pressure to the lateral face. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1999;88:303‐306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chen JY, Zeng DS, Yu D, Jin K. The use of kidney‐shaped pressure bandage to prevent postoperative salivary fistula. Shanghai Kou Qiang Yi Xue. 2010;19:144‐146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Heo KW, Baek MJ, Park SK. Pressure dressing after excision of preauricular sinus: suture transfixion of silicone sheets. J Laryngol Otol. 2009;123:1367‐1370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.