ABSTRACT

Genome editing in non-model bacteria is important to understand gene-to-function links that may differ from those of model microorganisms. Although species of the Burkholderia cepacia complex (Bcc) have great biotechnological capacities, the limited genetic tools available to understand and mitigate their pathogenic potential hamper their utilization in industrial applications. To broaden the genetic tools available for Bcc species, we developed RhaCAST, a targeted DNA insertion platform based on a CRISPR-associated transposase driven by a rhamnose-inducible promoter. We demonstrated the utility of the system for targeted insertional mutagenesis in the Bcc strains B. cenocepacia K56-2 and Burkholderia multivorans ATCC17616. We showed that the RhaCAST system can be used for loss- and gain-of-function applications. Importantly, the selection marker could be excised and reused to allow iterative genetic manipulation. The RhaCAST system is faster, easier, and more adaptable than previous insertional mutagenesis tools available for Bcc species and may be used to disrupt pathogenicity elements and insert relevant genetic modules, enabling Bcc biotechnological applications.

IMPORTANCE

Species of the Burkholderia cepacia complex (Bcc) have great biotechnological potential but are also opportunistic pathogens. Genetic manipulation of Bcc species is necessary to understand gene-to-function links. However, limited genetic tools are available to manipulate Bcc, hindering our understanding of their pathogenic traits and their potential in biotechnological applications. We developed a genetic tool based on CRISPR-associated transposase to increase the genetic tools available for Bcc species. The genetic tool we developed in this study can be used for loss and gain of function in Bcc species. The significance of our work is in expanding currently available tools to manipulate Bcc.

KEYWORDS: Burkholderia, CAST, genetic tools, targeted mutagenesis, gene insertion

INTRODUCTION

Species in the genus Burkholderia have potential use in agriculture and bioremediation and as cell factories but are also opportunistic pathogens (1–3). One example is the subgroup Burkholderia cepacia complex (Bcc), which comprises species with plant protective and growth promotion properties and produces enzymes and metabolites of commercial interest (1–4). Unfortunately, all Bcc species can cause severe infections in people with cystic fibrosis and compromised immune systems (4), which hampers their utilization in biotechnological applications.

Developing genetic tools for genome editing could help streamline Bcc genomes, eliminating their pathogenic potential and enhancing biotechnological capacities. However, genome editing in Bcc species is challenging due to the characteristics of their genomes, which range from 6 to 9 Mb and have approximately 65% GC content and repetitive DNA elements (4). In addition, many antibiotic resistance genetic markers are ineffective for mutant selection due to Bcc intrinsic resistance to most antibiotics (5, 6). Despite these difficulties, several genetic tools have been developed, which include methods for gene deletion (7), allelic replacement (8), insertional mutagenesis (9), plasmid-based gene expression (10, 11), CRISPR-based gene silencing or CRISPRi (12), and transposon mutagenesis (13). Except for CRISPRi, all site-directed editing tools in Bcc species are based on homologous recombination, which requires PCR amplification and cloning of homologous DNA flanking regions in suitable vectors. Examples of homologous recombination-based systems applied to Bcc are gene disruption with the pGPΩ (9) or pKNOCK (14, 15) plasmid series, allelic replacement with the pSHAFT-vector series (8), and gene deletion with pGPI-SceI and pDAI-SceI (7). For genomic DNA integration, transposon Tn7-based mini-Tn7 is inserted in the chromosome at an attTn7 site downstream of the essential glmS gene (16). While the Tn7 tool is valuable for genomic DNA integration, this system only allows integration at specific sites in the genome.

Recently, the CRISPR-associated transposases (CASTs) from Scytonema hofmannii (ShCAST) (17) and Vibrio cholerae (VchCAST) (18) have been developed into genetic tools that allow DNA sequence integration at targeted region(s) without the need for homologous recombination. In these systems, the transposases provide DNA integration properties while the CRISPR-Cas effectors allow programable, RNA-guided specific insertion of a DNA fragment or cargo DNA (19, 20). ShCAST was the first programmable tool for genomic insertion of desired cargo DNA in a recombination-independent manner (17). ShCAST consists of a V-K CRISPR effector (Cas12k) and the transposition proteins TnsB, TnsC, and TniQ. The V-K CRISPR effector forms a complex with TnsB, TnsC, and TniQ and catalyzes the RNA-guided DNA transposition by unidirectionally inserting DNA segments 60–66 bp downstream of protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) sequences (17). ShCAST was first used to introduce DNA insertions in Escherichia coli (17) and later in Burkholderia thailandensis, Agrobacterium fabrum (21), and Shewanella oneidensis (22). On the other hand, the V. cholerae VchCAST employs a type I-F CRISPR-Cas cascade consisting of the Cas6, Cas7, and Cas8 proteins and four transposases named TnsB, TnsC, TniQ, and TnsA (18, 23) and was also first applied to insert DNA in the E. coli genome (18). An improved version of VchCAST, called INTEGRATE, was later demonstrated to produce DNA insertions in Klebsiella oxytoca, Pseudomonas putida (23), and Agrobacterium tumefaciens (24). The overall lengths of the ShCAST and the INTEGRATE system are approximately 5,800 and 8,500 bp, respectively.

In this work, we develop RhaCAST, a ShCAST-based genetic tool driven by a rhamnose-inducible promoter, for targeted insertional mutagenesis in Bcc species. We chose ShCAST based on its smaller overall size compared to INTEGRATE and its previous successful use in a non-Bcc Burkholderia species, B. thailandensis (21). We demonstrate the applicability of RhaCAST for targeted-chromosomal gene integration in two Bcc species, Burkholderia cenocepacia K56-2 and Burkholderia multivorans ATCC 17616. RhaCAST was designed to allow multiple genetic manipulations by the recycling of selection markers

RESULTS

Construction of the RhaCAST system for use in Bcc strains

The RhaCAST system developed in this work (Fig. 1A) consists of two elements: a replicative plasmid pRhaCAST, encoding the ShCAST-associated machinery under the control of a rhamnose-inducible promoter, and a suicide plasmid pDonorTp, housing the cargo DNA. While pRhaCAST contains a chloramphenicol (Cm) resistance marker to facilitate plasmid maintenance, pDonorTp harbors a trimethoprim (Tp) resistance marker, dhfr, as the cargo DNA, flanked by the ShCAST-recognition sites left end (LE) and right end (RE), along with the flippase recombination target (FRT) sites (17, 25). pRhaCAST also harbors a constitutive promoter PJ23119 to drive the expression of the CRISPR RNA (crRNA), which guides the site-directed insertion of the DNA cargo sequence located in pDonorTp. The rationale and details for constructing the RhaCAST system are explained in the supplemental file and Materials and Methods, respectively.

Fig 1.

Schematics of RNA-guided DNA integration by ShCAST developed for Bcc (RhaCAST). (A) The two-plasmid ShCAST system encodes protein-RNA components. pRhaCAST encodes for tnsB, tnsC, tniQ, Cas12k, and crRNA scaffold, which form the complex needed for RNA-guided DNA integration driven by the rhamnose-inducible system (rhaR, rhaS). pDonorTp encodes for the cargo gene (TpR), encoding trimethoprim resistance flanked by the FRT internal to the transposon LE and RE. (B) Schematic of experimental overview for CAST-mediated genomic insertion. Plasmid pRhaCAST and pDonorTp would be introduced into B. cenocepacia K56-2 or B. multivorans ATCC 17616 with a helper strain carrying pRK2013 via tetra-parental conjugation. The transposition event is induced by L-rhamnose. The cargo flanking with LE and RE inserts directionally with LE integrating close to the PAM.

Use and validation of the RhaCAST system for insertional mutagenesis in B. cenocepacia K56-2

To evaluate the use of RhaCAST in Bcc species, we first analyzed possible PAM sequences based on the original systems. For ShCAST, the highest insertion frequencies in E. coli were obtained using the GGTT and GGTC PAMs (17). Also, the previous study that used the ShCAST system in B. thailandensis found that using a TGTC PAM resulted in high on-target insertion efficiency (21). Thus, we decided to target DNA regions containing GGTT, GGTC, and TGTC PAMs in B. cenocepacia K56-2 and aimed to interrupt genetic elements that would result in observable phenotypes.

We first targeted the paaA gene, which encodes the phenylacetyl-CoA oxygenase subunit PaaA (26). This gene is part of the paaABCDE operon, which enables phenylacetic acid (PAA) degradation and its utilization as a sole carbon source (27). Three crRNAs were designed to target paaA in B. cenocepacia K56-2 using intragenic GGTT, GGTC, and TGTC PAMs. The pRhaCAST plasmids containing the crRNAs targeting paaA were introduced into B. cenocepacia K56-2 via tetra-parental mating in media containing L-rhamnose alongside pDonorTp and the conjugal helper plasmid, pRK2013 (Fig. 1B). Colonies yielded from the tetra-parental mating were selected on media containing Tp, and then, their phenotype was studied by replica plating in PAA or glucose as the sole carbon sources. We observed that 92%, 82%, and 64% of the colonies in which the paaA gene had been targeted using GGTC, TGTC, and GGTT PAMs, respectively, had the expected phenotype, with growth on glucose but no growth on PAA (Table 1). Integration of the cargo DNA on target in clones with the desired phenotype was further confirmed by colony PCR (Fig. S1). In summary, we confirmed that the GGTC PAM yielded the highest number of transformants with on-target insertions.

TABLE 1.

Summary of targeting paaA with RhaCAST system in B. cenocepacia K56-2

| PAM | Distance between ATG and downstream PAM sequence (bp) | Conjugation efficiency (conjugant/recipient) | Colonies on target (mutants with expected phenotype/isolates screened) | Percent (%) on target |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GGTC | 436 | 5.95 × 10−7 | 46/50 | 92 |

| TGTC | 564 | 1.07 × 10−8 | 41/50 | 82 |

| GGTT | 81 | 2.47 × 10−8 | 39/61 | 64 |

Further application of the RhaCAST system to target fliF and phbC in B. cenocepacia K56-2

Next, we applied this system to disrupt other genes in B. cenocepacia K56-2. Specifically, we targeted fliF, a gene encoding a transmembrane protein crucial for the formation of the S and M rings within the basal body complex of the flagellum (28). Disrupting fliF is expected to yield non-flagellated cells since fliF plays a crucial role in flagellum formation (12, 29). Out of the 10 Tp-resistant colonies tested by colony PCR, nine yielded the expected PCR product, indicating integration of the cargo DNA at the correct position within fliF (Fig. S2). While wild-type (WT) cells exhibited motility in a plate-based assay, the mutants created with the RhaCAST system (fliF::CAST-Tp) showed complete abrogation of swimming motility (Fig. 2A and B). The lack of motility was similar to the effect observed in a control fliF mutant created with a homologous recombination-based system (fliF::pAH26) (Fig. 2A and B). Microscopy images also show that fliF mutants did not bear flagella (Fig. 2C).

Fig 2.

Targeting fliF by shCAST in B. cenocepacia K56-2 abolishes swimming motility. (A) Representative plate of motility assay performed in nutrient broth with 0.3% agar. Motility was determined by the growth of bacteria around the point of inoculation, exhibited as the wild type. Motility was ablated by CAST targeting of fliF in K56-2 WT: filF::pAH26 (insertional mutant) and fliF::CAST-Tp. (B) Diameter of the swimming motility halos in (A). Data are representative of three biological replicates repeated in triplicate. Diamond shapes in the boxplot represent the diameter mean. (C) The indicated strains were grown overnight and used for flagellum staining. The flagellum was stained with Ryu flagellum stain. Cells were imaged by differential interference contrast (DIC). The white arrows indicate the presence of flagellum. The scale bar is 5 µm.

To further assess the utility of RhaCAST in B. cenocepacia K56-2, phbC was targeted, which encodes poly-β-hydroxybutyrate polymerase, an enzyme required for PHB synthesis. We tested 10 Tp-resistant colonies obtained from conjugation by colony PCR, and nine showed the expected PCR product, indicating correct integration (Fig. S3). PHB granule accumulation was assessed by fluorescence microscopy following Nile red staining. Wild-type K56-2 formed large intracellular PHB granules. However, the mutants created with the RhaCAST system were unable to produce PHB granules, similar to a control mutant created with a homologous recombination-based system (phbC::pAH27) (12) (Fig. 3).

Fig 3.

Targeting phbC with shCAST abolishes poly-β-hydroxybutyrate granule accumulation in B. cenocepacia K56-2. Polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) granules are stained with Nile red, as seen on the bottom panels. WT, an insertional mutant of the phbC gene made with homologous recombination-based plasmid (phbC::pAH27), and an insertional mutant of the phbC gene made with pRhaCAST (phbC::pAH27) are shown. The scale bar is 5 µm.

RhaCAST-mediated gain of function, recycling of resistance marker for subsequent mutagenesis, and plasmid curing

To demonstrate the utility of the RhaCAST system for gain-of-function studies, we introduced a genetic element, free-use GFP (fugfp), into B. cenocepacia K56-2. We constructed pDonorTp-fugfp by cloning fugfp (30) into pDonorTp (Fig. 1 and 4A). The cargo was delivered to a genetically neutral locus of the B. cenocepacia K56-2 genome, the intragenic region between RS16895 and RS16900 (31). The RhaCAST-enabled insertion of fugfp resulted in a mutant B. cenocepacia K56-2::CAST-fugfp-Tp exhibiting the characteristic fluorescence (Fig. 4B and C).

Fig 4.

RhaCAST-mediated gain of function and recycling of antibiotic resistance cassette. (A) Schematics of the fugfp insertion into B. cenocepacia K56-2 chromosome after co-transformation of pRhaCAST and pDonorTp-fugfp. The TpR marker is excised by FLP-FRT recombination mediated by pFLP3, resulting in Tp-sensitive cells that express fugfp. The second integration event targets fliF in B. cenocepacia K56-2 CAST::fugfp by co-transformation of pRhaCAST and pDonorTp, resulting in B. cenocepacia K56-2 CAST::fugfp fliF::CAST-Tp. (B) Phenotypic characterization of motility and GFP signals in K56-2 wild-type (top left), K56-2::CAST-fugfp (top right), K56-2::fliF::CAST-Tp (bottom left), and K56-2::CAST-fugfp fliF::CAST-Tp (bottom right). The motility was determined by the presence of a halo surrounding the point of inoculation in nutrient broth with 0.3% agar. Expression of GFP was captured with FluorChem Q. (C) Micrographs showing green fluorescence of the K56-2::CAST-fugfp and K56-2::fliF::CAST-Tp mutants. The scale bar is 5 µm.

Burkholderia species display intrinsic resistance to many antibiotics commonly used as selectable markers. Thus, recycling the same antibiotic marker for subsequent mutagenesis would be ideal. We took advantage of the Flp-FRT system (25) to excise the dhfr gene between the FRT sites, thus rendering the mutants sensitive to Tp. In the case of the K56-2::CAST-fugfp-Tp mutant, the expression of Flp from the pFLP3 plasmid left the fugfp cargo in the chromosome (K56-2::CAST-fugfp) (Fig. S10). This strain was then used as the background for subsequent mutagenesis of fliF. The resulting strain, B. cenocepacia K56-2::CAST-fugfp fliF::CAST-Tp, was fluorescent and lacked swimming motility (Fig. 4B and C).

A common step immediately after mutant construction with a plasmid-based genetic tool is plasmid curation, usually performed by subculturing the obtained mutants without selective pressure to facilitate plasmid removal. However, a specific procedure for curing pRhaCAST from the CAST-Tp mutants was unnecessary. After tetra-parental mating, Tp-resistant colonies were selected with Tp and gentamycin (not Cm). Therefore, pRhaCAST was not maintained. We demonstrated the absence of pRhaCAST by replica-plating the mutants B. cenocepacia K56-2::CAST-fugfp-Tp in solid media with and without Cm (data not shown). The absence of pRhaCAST was also confirmed by whole-genome sequencing. Similarly, after the subsequent integration on fliF that resulted in B. cenocepacia K56-2::CAST-fugfp fliF::CAST-Tp, cells were tetracycline-sensitive, indicating the absence of pFLP3. Genome sequencing results confirmed that pFLP3 was no longer present in the strains tested.

Optimized RhaCAST for B. multivorans ATCC 17616

Having shown that the RhaCAST could mutagenize B. cenocepacia K56-2, we next focused on another species of Bcc, B. multivorans ATCC 17616. We employed a similar strategy as B. cenocepacia K56-2, targeting the paaA gene of B. multivorans ATCC 17616. However, we obtained no colonies following conjugation via tetra-parental mating at 37°C. It has been reported that conducting transposition using VchCAST at temperatures lower than 37°C (30°C or 25°C) can strongly enhance integration efficiencies in E. coli (23) due to a slower growth rate, allowing longer transposition times. To determine if lowering incubation temperature would increase the integration efficacy of RhaCAST, we targeted the paaA gene in B. multivorans by performing tetra-parental matings at three different temperatures, 37°C, 30°C, and 23°C. We only observed Tp-resistant clones when the conjugation was performed at 23°C.

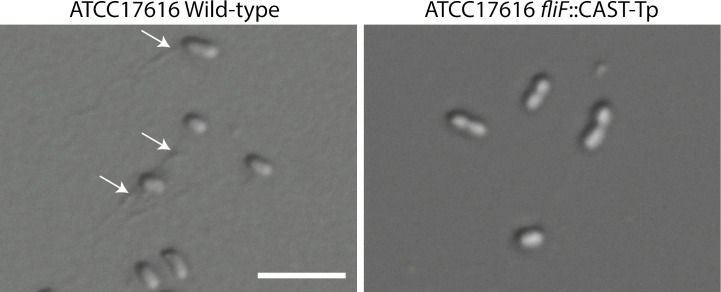

The phenotypic characterization of the B. multivorans ATCC17616 putative paaA mutants was performed similarly to B. cenocepacia K56-2, where we patched Tp-resistant transformants onto M9 minimal media with phenylacetic acid or glucose as the sole carbon sources. Targeting the chromosome with two PAMs (GGTC and CGTC) resulted in 97% and 92% DNA cargo insertion efficiency, respectively. However, targeting with GGTT resulted in successful integration only in 11% of the colonies tested (Table 2). Integration of the cargo DNA on target in clones with the desired phenotype was further confirmed by colony PCR (Fig. S4). We also targeted fliF of B. multivorans ATCC 17616 and confirmed the insertion site with colony PCR. From the 10 colonies tested, 9 exhibited the expected size of the PCR product for integration (Fig. S5). As expected, the mutant shows complete abolishment of the flagellum (Fig. 5).

TABLE 2.

Summary of targeting paaA with RhaCAST system in B. multivorans ATCC 17616

| PAM | Distance between ATG and downstream PAM (bp) | Conjugation efficiency (conjugant/recipient) |

Colonies on target (mutant with expected phenotype/isolate screened) | Percent (%) on target |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CGTC | 435 | 7.22 × 10−9 | 12/13 | 92 |

| GGTT | 80 | 4.33 × 10−9 | 1/9 | 11 |

| GGTC | 193 | 1.60 × 10−8 | 30/31 | 97 |

Fig 5.

Targeting fliF by shCAST in B. multivorans ATCC 17616 abolished flagellum formation. The indicated strains were grown overnight and used for flagellum staining. Cells were imaged by DIC. The white arrows indicate the presence of flagellum. The scale bar is 5 µm.

Long-read sequencing confirms on-site insertional mutagenesis and detects the frequency of whole-plasmid integration

It has been observed that the ShCAST system can sometimes result in the co-integration of the entire donor plasmid into the targeted site (21, 32). To explore this possibility, we performed long-read sequencing of several mutants created with our RhaCAST system (Table 3). Of 15 genomes sequenced, 100% contained the DNA cargo on target, but in 3 of them, the insertion consisted of whole-plasmid integration. While all single insertional mutants showed integration of cargo DNA only (Fig. S6 to S9), one of two double mutants sequenced showed co-integration of the whole plasmid into the target site (Fig. S11). In B. multivorans ATCC17616, two of the four sequenced mutants had the whole plasmid integrated into the genome (Fig. S12). For the mutants with the cargo-only insertion, the distances of the PAM and LE were between 59 and 67 bp, similar to the previously reported integration distance from PAM in E. coli, which is 60–66 bp (17).

TABLE 3.

Long-read sequencing summary of mutants created using RhaCAST system in B. cenocepacia K56-2 and B. multivorans ATCC17616

| Mutants | crRNA’s primer number | Summary | Distance of cargo integration (bp)a |

|---|---|---|---|

| K56-2 paaA::CAST-Tp | 3390 | On-target, integration of cargo only | 63 |

| K56-2 paaA::CAST-Tp | 3422 | On-target, integration of cargo only | 61 |

| K56-2 paaA::CAST-Tp | 3423 | On-target, integration of cargo only | 63 |

| K56-2 fliF::CAST-Tp | 3463 | On-target, integration of cargo only | 67 |

| K56-2 fliF::CAST-Tp | 3466 | On-target, integration of cargo only | 64 |

| K56-2 phbC::CAST-Tp | 3469 | On-target, integration of cargo only | 64 |

| K56-2 phbC::CAST-Tp | 3472 | On-target, integration of cargo only | 64 |

| K56-2::CAST-fugfp-Tp | 3475 | On-target, integration of cargo only | 63 |

| K56-2::CAST-fugfp-Tp | 3478 | On-target, integration of cargo only | 64 |

| K56-2::CAST-fugfp fliF::CAST-Tp | 3475 | On-target, integration of cargo only | 60 |

| K56-2::CAST-fugfp fliF::CAST-Tp | 3475 | On-target, whole-plasmid integrationb | 63 |

| ATCC 17616 paaA::CAST-Tp | 3390 | On-target, integration of cargo only | 59 |

| ATCC 17616 paaA::CAST-Tp | 3422 | On-target, whole-plasmid integrationb | 65 |

| ATCC 17616 paaA::CAST-Tp | 3424 | On-target, integration of cargo only | 59 |

| ATCC 17616 fliF::CAST-Tp | 3463 | On-target, whole-plasmid integrationb | 60 |

From PAM to LE.

Co-integration of the cargo DNA and the whole plasmid.

DISCUSSION

Genetic tools are necessary to dissect genotype–phenotype relationships, especially in organisms like Bcc species, which display a duality of beneficial and pathogenic traits. Here, we report the application of the ShCAST system to the Bcc for targeted DNA insertion without homologous recombination. Several research groups have optimized ShCAST for various species, including S. oneidensis (22), B. thailandensis, P. putida, and A. fabrum (21). Most ShCAST systems have the constitutive Plac promoter to drive the expression of tnsB, tnsC, tniQ, and cas12k genes, except for S. oneidensis MR-1, where the endogenous promoters were used (22). The Plac promoter is non-functional in several Burkholderia species strains, including B. cenocepacia and B. multivorans (9). This work employed a rhamnose-inducible, tightly regulated expression system (10) to drive tnsB-tnsC-tniQ-Cas12k-tracrRNA expression.

To introduce the pRhaCAST and pDonor into B. cenocepacia K56-2, we performed tetra-parental conjugation with the helper plasmid pRK2013 at a conjugation temperature of 37°C. However, conjugation for B. multivorans ATCC17616 only yielded transformants when the conjugation was performed at 23°C. It has been suggested that lower temperatures could exhibit higher integration efficiencies (23). In E. coli, incubation times at either 30°C or 25°C can enhance integration efficiencies with VchCAST (33). However, the mechanistic explanation for the temperature effect on CAST systems has not been thoroughly studied.

It has been described that the use of ShCAST for site-specific genome targeting resulted in whole-plasmid integration into the target site due to the lack of functional TnsA (32). This issue has been observed in various species, including E. coli, B. thailandensis, P. putida, and A. fabrum (21, 34, 35). We also observed a few instances of co-integration of full-length plasmid in B. cenocepacia and B. multivorans. Using linear or 5′-nicked DNA donors could prevent co-integration formation (34). However, these approaches cannot be applied if the plasmid is introduced into the recipient via conjugation. While incorporation of whole plasmids has a low frequency, it is a limitation of the system. To rule out whole-plasmid integration in selected mutants, PCR amplification of the target gene should reveal a PCR product that includes the cargo DNA’s expected size. A failed PCR reaction or a longer-than-expected PCR product may signal whole-plasmid integration. To confirm the suspected whole-plasmid integration, we recommend whole-genome sequencing. Alternatively, multiple studies have shown that the ShCAST system has off-target activity and lower fidelity than the INTEGRATE system in various species. Whether the INTEGRATE system can overcome some of the limitations of RhaCAST in any Bcc species remains to be demonstrated.

The RhaCAST system developed for Bcc provides an improved targeted integration system compared to available targeted mutagenesis and Tn7 tools for chromosomal integration. Current site-directed genome editing tools are based on homologous recombination, which requires the cloning of long homology arms (9). As for genomic integration with Tn7 tools, integration could be only at specific sites (16). RhaCAST allows targeting any genomic region with only 24 bp of crRNA to deliver a cargo DNA. The delivered DNA fragment can be aimed to disrupt a functional element or introduce a genetic element in the chromosome at a specific site. In addition, the pRhaCAST plasmid is easily cured as opposed to the plasmid described by Strecker et al., which cannot be cured easily after transformation (21). Other systems developed based on ShCAST require extra curing steps dependent on the temperature-sensitive origin (21) or via counter selection (22). The spontaneous curing of pRhaCAST allows the system to be used iteratively without additional steps of plasmid curation. It should be noted, however, that while we observed high integration efficiency of selected genes, other genomic regions may be more challenging to target.

In summary, the RhaCAST system is a versatile tool that can be used for both loss- and gain-of-function applications in Bcc species. Additionally, this system allows for the excision and reuse of the selection marker, enabling iterative genetic manipulation without additional selection markers. The RhaCAST system is faster, easier, and more adaptable than existing insertional mutagenesis tools for Bcc species. RhaCAST may be used to disrupt and insert relevant genetic elements, paving the way for future Bcc biotechnological applications.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, selective antibiotics, and growth conditions

Strains and plasmids are shown in Table 4 and Table S1. Primers used in this study are listed in Table S2. All strains were grown in a LB-Lennox medium (Difco). B. cenocepacia K56-2, B. multivorans ATCC 17616, and the strains of E. coli were grown at 37°C, except for E. coli Stbl2, which was grown at 30°C. The following selective antibiotics were used: Cm (Sigma; 20 µg/mL for E. coli), Tp (Sigma; 100 µg/mL for strains of Burkholderia, 50 µg/mL for E. coli), and gentamicin (Sigma; 50 µg/mL for all strains of Burkholderia).

TABLE 4.

Strains and plasmids used in this work

| Strain or plasmid | Features | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Burkholderia cenocepacia K56-2 | Clinical isolate from cystic fibrosis patient; ET12 lineage | (36) |

| K56-2 fliF::pAH26 | Derived from K56-2; pAH26 integrated into fliF; Tpr | (12) |

| K56-2 phbC::pAH27 | Derived from K56-2; pAH27 integrated into phbC; Tpr | (12) |

| K56-2 paaA::CAST-Tp (3390) | Derived from K56-2; cargo containing Tpr integrated into paaA; made with crRNA 3390 | This study |

| K56-2 paaA::CAST-Tp (3422) | Derived from K56-2; cargo containing Tpr integrated into paaA; made with crRNA 3422 | This study |

| K56-2 paaA::CAST-Tp (3423) | Derived from K56-2; cargo containing Tpr integrated into paaA; made with crRNA 3423 | This study |

| K56-2 fliF::CAST-Tp (3463) | Derived from K56-2; cargo containing Tpr integrated into fliF; made with crRNA 3463 | This study |

| K56-2 fliF::CAST-Tp (3466) | Derived from K56-2; cargo containing Tpr integrated into fliF; made with crRNA 3466 | This study |

| K56-2 phbC::CAST-Tp (3469) | Derived from K56-2; cargo containing Tpr integrated into phbC; made with crRNA 3466 | This study |

| K56-2 phbC::CAST-Tp (3472) | Derived from K56-2; cargo containing Tpr integrated into phbC; made with crRNA 3472 | This study |

| K56-2::CAST-fugfp-Tp (3475) | Derived from K56-2; cargo containing fugfp and Tpr integrated into intergenic region RS16895-90; made with crRNA 3475 | This study |

| K56-2::CAST-fugfp-Tp (3478) | Derived from K56-2; cargo containing fugfp and Tpr integrated into intergenic region RS16895-90; made with crRNA 3478 | This study |

| K56-2::CAST-fugfp | Derived from K56-2::CAST-fugfp-Tp (3475); Tpr flanking by the FRT region excised via Flp recombination using pFLP3 | This study |

| K56-2::CAST-fugfp fliF::CAST-Tp | Derived from K56-2::CAST-fugfp (3475); cargo containing Tpr integrated into fliF; made with crRNA 3463 | This study |

|

Burkholderia multivorans ATCC 17616 |

Soil sample | ATCC |

| ATCC 17616 paaA::CAST-Tp (3390) | Derived from ATCC17616; cargo containing Tpr integrated into paaA; made with crRNA 3390 | This study |

| ATCC 17616 paaA::CAST-Tp (3422) | Derived from ATCC17616; cargo containing Tpr integrated into paaA; made with crRNA 3422 | This study |

| ATCC 17616 paaA::CAST-Tp (3424) | Derived from ATCC17616; cargo containing Tpr integrated into paaA; made with crRNA 3424 | This study |

| ATCC 17616 fliF::CAST-Tp (3463) | Derived from ATCC17616; cargo containing Tpr integrated into fliF; made with crRNA 3463 | This study |

| E. coli DH5α |

F- Φ80lacZΔM15 Δ(lacZYAargF) U169 recA1 endA1 hsdR17 (rH−, mK+) phoA supE44 λ− thi-1 gyrA96 relA1 |

Cardona lab collection |

| E. coli Stbl2 | F- mcrA Δ(mcrBC-hsdRMS-mrr) recA1 endA1lon gyrA96 thi supE44 relA1 λ− Δ(lac-proAB) | Invitrogen |

| E. coli PIR1 | F- ∆lac169 rpoS(Am) robA1 creC510 hsdR514 endA recA1 uidA(∆MluI)::pir-116 | Cardona lab collection |

| E. coli SY327 | F- araD Δ(lac-proAB) argE(Am) recA56 Rifr nalA λpir | (37) |

| pHelper_ShCAST_crRNA | AmpR, oricolE1, Sh-cas12K-tnsBC-tniQ, PJ23119-crRNA | (17) |

| pDonor_ShCAST_kanR | KmR, oriR6K, Tn-neo | (17) |

| pSCrhaB2plus | ripBBR1

rhaR, rhaS, PrhaB TpR mob+, rhaI1-rhaI1 permutation of rhaS binding sites upstream of PrhaBAD and bacteriophage T7 gene 10 stem-loop inserted upstream of native rhaBAD 5′ UTR |

(10) |

| pKD3 | Cmr oriR6K rgnB | (38) |

| pRK2013 | ricolE1 RK2 derivative Kanr mob+ tra+ | (39) |

| pZLrhaB2plus | pSCrhaB2plus with modifications of resistance cassette to CmR | This study |

| pDonorTp | pDonor_ShCAST_kanR with modification of KmR to TpR | This study |

| pDonorTp-fugfp | pDonorTp with the addition of fugfp gene from pUS252 outside of the FRT sites | This study |

| pUS252 | ripUC, KmR, fuGFP | Addgene plasmid #127674 |

| pFLP3 | Ampr, Tetr, Flp | (30) |

| pRhaCAST | pZLrhaB2plus with Sh-cas12K-tnsBC-tniQ cloned into, which is driven by the rhamnose-inducible promoter | This study |

Construction of the RhaCAST system

pRhaCAST

First, the dhfr resistance marker gene of pSCrhaB2plus (Addgene plasmid #164226) was changed by the chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (cat) gene. Briefly, the cat gene was PCR-amplified from pKD3 (Addgene plasmid #45604) using primers 876 and 877. This PCR product was introduced into pSCrhaB2plus by restriction cloning with NsiI and EcoRV, replacing the original dhfr with cat. The resulting construct was transformed into E. coli DH5α, and Cm-resistant colonies were screened by colony PCR with primers 876 and 877 to isolate clones harboring the resulting plasmid, pZLrhaB2plus. Next, components of the ShCAST (tnsB, tnsC, tniQ, and Cas12k) and the crRNA region were PCR-amplified from pHelper_ShCAST_crRNA (Addgene plasmid #127921) (17) using primers 3145 and 3146. This PCR product was introduced into pSCrhaB2plus by restriction cloning with NdeI and XbaI. The resulting construct was transformed into E. coli Stbl2, and Cm-resistant colonies were screened by colony PCR with primers 848 and 1120. The obtained plasmid was called pRhaCAST.

pDonorTp

To replace the antibiotic resistance marker of pDonor_ShCAST_kanR (Addgene plasmid #127924) from neo (kanamycin resistance) to dhfr, the dhfr gene was first PCR-amplified from pTnMod-STp (GenBank accession: AF061932) (40) using primers 1025 and 1001. Next, pDonor_ShCAST_kanR was inverse PCR-amplified using primers 1540 and 1541 to remove the neo gene. The two DNA fragments were restricted with KpnI and XhoI and ligated, and the ligation products were transformed into E. coli PIR1. Tp-resistant colonies were determined by colony PCR with primers 1542 and 1543. The obtained plasmid was called pRhaCAST. The sequences of pZLrhaB2plus, pRhaCAST, and pDonorTp were confirmed by whole-plasmid sequencing performed by Plasmidsaurus using Oxford Nanopore Technology (ONT).

Cloning of crRNAs into pRhaCAST

crRNAs were ordered as single-stranded oligos from Integrated DNA Technologies and PCR-amplified to create double-stranded DNA fragments. The PCR products were then introduced into pRhaCAST using Golden Gate cloning with SapI, with the following cycle parameters: (5 min 37°C → 5 min 16°C) × 50 cycles followed by 5 min at 60°C and 5 min at 85°C. The newly constructed plasmids were then transformed into E. coli Stbl2. Cm-resistant colonies were screened by colony PCR with either primers 848 and 1120 or primers 848 and the spacer-specific primers.

Construction of pDonorTp-fugfp

The fugfp gene was PCR-amplified from pUS252 with primers 3481 and 3482, adding XmaI and NdeI restriction sites. pDonorTp was inverse PCR-amplified with primers 3483 and 3484 harboring the same restriction sites. The fugfp gene was then introduced outside the FRT sites in pDonorTp by restriction cloning with the XmaI and NdeI sites. Successful E. coli SY327 transformants were determined by colony PCR with primers 3482 and 3485 and screening for fuGFP fluorescence. pDonorTp-fugfp sequence was confirmed by whole-plasmid sequencing performed by Plasmidsaurus using ONT.

Tetra-parental mating

Tetra-parental mating was performed similarly to tri-parental mating, as previously described (31). E. coli MM290/pRK2013 (helper strain), E. coli Stbl2/pRhaCAST with corresponding crRNA, and E. coli PIR1/pDonorTp or pDonorTp-fugfp were conjugated into Burkholderia. Briefly, each 5 mL of the subculture of the recipient was made from 100 µL overnight culture and was grown to an optical density (OD) of 0.3–0.6. E. coli containing plasmids was harvested and resuspended in LB and adjusted to a 1.5-mL suspension with an OD600 of 0.3. An overnight culture of the recipient was subcultured in 5 mL of LB and grown to the OD600 of 0.3–0.6. The resulting culture was adjusted to a 0.5-mL suspension in LB with an OD600 of 1.0. All the cultures were mixed and centrifuged at 5,000 rcf for 5 min. The pellet was then resuspended in 100 µL of LB broth and spotted onto an LB agar plate containing 0.05% rhamnose. The plate was incubated at 37°C or 23°C, depending on the recipient strain, for 24 hours. The cells were collected and resuspended in 1 mL of LB, and 100 µL of the cell suspension was plated (without diluting) in LB plates with gentamycin and Tp.

Removal of antibiotic resistance cassette using Flp-FRT recombination

The Flp expression vector pFLP3 (30) was introduced into Burkholderia::CAST-fugfp-Tp by tri-parental mating using E. coli MM290/pRK2013 as a helper strain. Tetracycline and gentamycin-resistant colonies were selected and patched onto LB agar plates with Tp to check for sensitivity. The resulting strain has the Tp resistance cassette excised and is left with fugfp in the genome. The exconjugants sensitive to Tp were used for subsequent mutagenesis.

Phenotypic characterization of phenylacetic acid auxotroph mutant

Colonies obtained from tetra-parental mating were patched onto M9 medium agar with 10 mM phenylacetic acid or 20 mM glucose, 100 μg/mL Tp, and 50 µg/mL gentamycin. Plates were incubated for 24 hours at 37°C. The phenylacetic acid auxotroph mutants were identified by the absence of growth in the medium containing phenylacetic acid as the carbon source and the presence of growth in the glucose-containing medium.

Flagellum staining

Cells were prepared for flagellum staining as previously described (12). Briefly, an overnight culture was incubated statically at room temperature for 20–25 min. A 1:10 dilution of this culture was prepared in sterile water, carefully mixed by tapping for 30 sec, and left to sit statically for 20–25 min. A drop of the diluted culture was placed on a glass slide and rested for 20 min. A cover glass was applied gently to the samples. Flagella were stained using the Ryu stain (41). Ryu flagellum stain was added in excess toward one side of the coverslip and allowed to dry for 2–3 hours at room temperature. Slides were observed by light microscopy at 1,000× total magnification on an upright AxioImager Z1 (Zeiss).

Nile red staining and detection of PHA granules

PHA granules were detected as previously reported (12), with some modifications. Briefly, overnight cultures of the appropriate strains were inoculated to an OD600 of 0.025 and grown at 37°C for 3 hours with shaking at 230 rpm. One milliliter of the resulting culture was washed twice and resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS); 3.7% formaldehyde + 1% methanol (Sigma) was used to fix the cells at room temperature for 10 min; excess formaldehyde was quenched by the addition of an equal volume of 0.5 M glycine. Cells were washed, resuspended in PBS, and stained at room temperature with 0.5 µg/mL Nile red (Carbosynth) for 20 min. Excess stain was removed by washing with PBS; then, cells were mounted on 1.5% agarose pads and imaged by fluorescence microscopy at 1,000× on an upright AxioImager Z1 (Zeiss). Nile red was excited at 546/12 nm and detected at 607/33 nm.

FuGFP detection

Fluorescence microscopy was performed as previously described (12). Overnight cultures of cells expressing FuGFP were first diluted to an OD600 of 0.025 and grown for 3 hours to an OD600 of 0.15 (early exponential phase). Cells were immobilized on 1.5% agarose pads and imaged with an AxioImager Z1 (Zeiss). FuGFP was excited at 470/40 nm and detected at 525/50 nm.

Plate-based motility assay

The plate-based motility assay was performed as previously described (12), with some modifications. Briefly, strains were grown on LB agar with the appropriate antibiotics, and single colonies were selected to stab-inoculate into a motility medium consisting of nutrient broth (Difco) with 0.3% agar. Plates were incubated right-side up for 22 hours at 37°C. The motility halos were recorded quantitatively by measuring the diameter of turbidity, corresponding to the bacteria swimming away from the point of inoculation. The images of the motility assay performed on fugfp-expressing mutants were taken with a FluorChem Q system (Cell Biosciences, Santa Clara, CA).

Genome sequencing and data analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted using the PureLink microbiome DNA purification kit (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Long-read sequencing was performed by Plasmidsaurus using ONT with custom annotations. Briefly, the genomic DNA was minimally fragmented, and the amplification-free long-read sequencing library was constructed using the v14 library prep chemistry. The library was then sequenced using R10.4.1 flow cells (ONT); genome assemblies were performed with Flye v2.9.1 (42) using high-quality ONT reads and were polished with Medaka v1.8.0. The genome annotations were performed using Bakta v1.6.1 (43). Sequences were analyzed with Geneious 8.1.9.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by a Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC) of Canada Discovery Grant to S.T.C. and a University of Manitoba Collaborative Research Program (UCRP) grant to S.T.C. and D.B.L. Z.L.Y. was supported by a Research Manitoba and University of Manitoba Graduate Fellowship (UMGF); A.S.M.Z.R. was supported by a University of Manitoba Graduate Fellowship (UMGF); A.M.H. was supported by a Cystic Fibrosis Canada studentship and a Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Vanier award.

S.T.C. and Z.L.Y. formulated the ideas and design of the project; Z.L.Y., A.S.M.Z.R., and A.M.H. designed and cloned the plasmids and mutants; Z.L.Y., A.S.M.Z.R., and A.M.H. performed phenotypic assays; Z.L.Y. and A.S.M.Z.R. processed and analyzed the data; Z.L.Y. wrote the manuscript and edited together with S.T.C., A.S.M.Z.R., A.M.H., and D.B.L.; S.T.C. and D.B.L. provided financial support and supervised the work.

Contributor Information

Silvia T. Cardona, Email: silvia.cardona@umanitoba.ca.

Nicole R. Buan, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, Lincoln, Nebraska, USA

DATA AVAILABILITY

For ease of distribution, the following plasmids are deposited to Addgene: pZLrhaB2plus (#211787), pRhaCAST (#211791), pDonorTp (#211788), and pDonorTp-fugfp (#211790). All the genome sequences of the mutants from this study are available in the NCBI database under BioProject PRJNA1041412.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

The following material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1128/aem.00699-24.

Rationale for the construction of RhaCAST, Tables S1 and S2, and Figures S1 to S12.

ASM does not own the copyrights to Supplemental Material that may be linked to, or accessed through, an article. The authors have granted ASM a non-exclusive, world-wide license to publish the Supplemental Material files. Please contact the corresponding author directly for reuse.

REFERENCES

- 1. Depoorter E, Bull MJ, Peeters C, Coenye T, Vandamme P, Mahenthiralingam E. 2016. Burkholderia: an update on Taxonomy and Biotechnological potential as antibiotic producers. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 100:5215–5229. doi: 10.1007/s00253-016-7520-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Eberl L, Vandamme P. 2016. Members of the genus Burkholderia: good and bad guys. F1000Res 5:1007. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.8221.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Morya R, Salvachúa D, Thakur IS. 2020. Burkholderia: an untapped but promising bacterial genus for the conversion of aromatic compounds. Trends Biotechnol 38:963–975. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2020.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mahenthiralingam E, Urban TA, Goldberg JB. 2005. The multifarious, multireplicon Burkholderia cepacia complex. Nat Rev Microbiol 3:144–156. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Scoffone VC, Chiarelli LR, Trespidi G, Mentasti M, Riccardi G, Buroni S. 2017. Burkholderia cenocepacia infections in cystic fibrosis patients: drug resistance and therapeutic approaches. Front Microbiol 8:1592. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rhodes KA, Schweizer HP. 2016. Antibiotic resistance in Burkholderia species. Drug Resist Updat 28:82–90. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2016.07.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Flannagan RS, Linn T, Valvano MA. 2008. A system for the construction of targeted unmarked gene deletions in the genus Burkholderia. Environ Microbiol 10:1652–1660. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2008.01576.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Shastri S, Spiewak HL, Sofoluwe A, Eidsvaag VA, Asghar AH, Pereira T, Bull EH, Butt AT, Thomas MS. 2017. An efficient system for the generation of marked genetic mutants in members of the genus Burkholderia. Plasmid 89:49–56. doi: 10.1016/j.plasmid.2016.11.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Flannagan RS, Aubert D, Kooi C, Sokol PA, Valvano MA. 2007. Burkholderia cenocepacia requires a periplasmic HtrA protease for growth under thermal and osmotic stress and for survival in vivo. Infect Immun 75:1679–1689. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01581-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hogan AM, Jeffers KR, Palacios A, Cardona ST. 2021. Improved dynamic range of a rhamnose-inducible promoter for gene expression in Burkholderia spp. Appl Environ Microbiol 87:e0064721. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00647-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cardona ST, Valvano MA. 2005. An expression vector containing a rhamnose-inducible promoter provides tightly regulated gene expression in Burkholderia cenocepacia. Plasmid 54:219–228. doi: 10.1016/j.plasmid.2005.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hogan AM, Rahman ASMZ, Lightly TJ, Cardona ST. 2019. A broad-host-range CRISPRi toolkit for silencing gene expression in Burkholderia. ACS Synth Biol 8:2372–2384. doi: 10.1021/acssynbio.9b00232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Scoffone VC, Trespidi G, Barbieri G, Irudal S, Israyilova A, Buroni S. 2021. Methodological tools to study species of the genus Burkholderia. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 105:9019–9034. doi: 10.1007/s00253-021-11667-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Alexeyev MF. 1999. The pKNOCK series of broad-host-range mobilizable suicide vectors for gene knockout and targeted DNA insertion into the chromosome of gram-negative bacteria. Biotechniques 26:824–826. doi: 10.2144/99265bm05 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Castonguay-Vanier J, Vial L, Tremblay J, Déziel E. 2010. Drosophila melanogaster as a model host for the Burkholderia cepacia complex. PLoS ONE 5:e11467. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Heacock-Kang Y, McMillan IA, Zarzycki-Siek J, Sun Z, Bluhm AP, Cabanas D, Hoang TT. 2018. The heritable natural competency trait of Burkholderia pseudomallei in other Burkholderia species through comE and crp. Sci Rep 8:12422. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-30853-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Strecker J, Ladha A, Gardner Z, Schmid-Burgk JL, Makarova KS, Koonin EV, Zhang F. 2019. RNA-guided DNA insertion with CRISPR-associated transposases. Science 365:48–53. doi: 10.1126/science.aax9181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Klompe SE, Vo PLH, Halpin-Healy TS, Sternberg SH. 2019. Transposon-encoded CRISPR–Cas systems direct RNA-guided DNA integration. Nature 571:219–225. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1323-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Park J-U, Tsai AW-L, Chen TH, Peters JE, Kellogg EH. 2022. Mechanistic details of CRISPR-associated transposon recruitment and integration revealed by cryo-EM. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 119:e2202590119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2202590119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zeng T, Yin J, Liu Z, Li Z, Zhang Y, Lv Y, Lu M-L, Luo M, Chen M, Xiao Y. 2023. Mechanistic insights into transposon cleavage and integration by TnsB of ShCAST system. Cell Rep 42:112698. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2023.112698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Trujillo Rodríguez L, Ellington AJ, Reisch CR, Chevrette MG. 2023. CRISPR-associated transposase for targeted mutagenesis in diverse proteobacteria. ACS Synth Biol 12:1989–2003. doi: 10.1021/acssynbio.3c00065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cheng Z-H, Wu J, Liu J-Q, Min D, Liu D-F, Li W-W, Yu H-Q. 2022. Repurposing CRISPR RNA-guided integrases system for one-step, efficient genomic integration of ultra-long DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res 50:7739–7750. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkac554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Vo PLH, Ronda C, Klompe SE, Chen EE, Acree C, Wang HH, Sternberg SH. 2021. CRISPR RNA-guided Integrases for high-efficiency, multiplexed bacterial genome engineering. Nat Biotechnol 39:480–489. doi: 10.1038/s41587-020-00745-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Aliu E, Lee K, Wang K. 2022. CRISPR RNA-guided integrase enables high-efficiency targeted genome engineering in Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Plant Biotechnol J 20:1916–1927. doi: 10.1111/pbi.13872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hoang TT, Karkhoff-Schweizer RR, Kutchma AJ, Schweizer HP. 1998. A broad-host-range Flp-FRT recombination system for site-specific excision of chromosomally-located DNA sequences: application for isolation of unmarked Pseudomonas aeruginosa mutants. Gene 212:77–86. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(98)00130-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Teufel R, Mascaraque V, Ismail W, Voss M, Perera J, Eisenreich W, Haehnel W, Fuchs G. 2010. Bacterial phenylalanine and phenylacetate catabolic pathway revealed. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107:14390–14395. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005399107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Law RJ, Hamlin JNR, Sivro A, McCorrister SJ, Cardama GA, Cardona ST. 2008. A functional phenylacetic acid catabolic pathway is required for full pathogenicity of Burkholderia cenocepacia in the Caenorhabditis elegans host model. J Bacteriol 190:7209–7218. doi: 10.1128/JB.00481-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Francis NR, Irikura VM, Yamaguchi S, DeRosier DJ, Macnab RM. 1992. Localization of the Salmonella typhimurium flagellar switch protein FliG to the cytoplasmic M-ring face of the basal body. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 89:6304–6308. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.14.6304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Yang P, Zhang M, van Elsas JD. 2017. Role of flagella and type four Pili in the co-migration of Burkholderia terrae BS001 with fungal hyphae through soil. Sci Rep 7:2997. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-02959-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Choi KH, Gaynor JB, White KG, Lopez C, Bosio CM, Karkhoff-Schweizer RR, Schweizer HP. 2005. A Tn7-based broad-range bacterial cloning and expression system. Nat Methods 2:443–448. doi: 10.1038/nmeth765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hogan AM, Scoffone VC, Makarov V, Gislason AS, Tesfu H, Stietz MS, Brassinga AKC, Domaratzki M, Li X, Azzalin A, Biggiogera M, Riabova O, Monakhova N, Chiarelli LR, Riccardi G, Buroni S, Cardona ST. 2018. Competitive fitness of essential gene knockdowns reveals a broad-spectrum antibacterial inhibitor of the cell division protein FtsZ. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 62:e01231-18. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01231-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Vo PLH, Acree C, Smith ML, Sternberg SH. 2021. Unbiased profiling of CRISPR RNA-guided transposition products by long-read sequencing. Mob DNA 12:13. doi: 10.1186/s13100-021-00242-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gelsinger DR, Vo PLH, Klompe SE, Ronda C, Wang H, Sternberg SH. 2023. Bacterial genome engineering using CRISPR RNA-guided transposases. bioRxiv:2023.03.18.533263. doi: 10.1101/2023.03.18.533263 [DOI]

- 34. Strecker J, Ladha A, Makarova KS, Koonin EV, Zhang F. 2020. Response to comment on “RNA-guided DNA insertion with CRISPR-associated transposases”. Science 368:eabb2920. doi: 10.1126/science.abb2920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rice PA, Craig NL, Dyda F. 2020. Comment on “RNA-guided DNA insertion with CRISPR-associated transposases” Science 368:eabb2022. doi: 10.1126/science.abb2022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Darling P, Chan M, Cox AD, Sokol PA. 1998. Siderophore production by cystic fibrosis isolates of Burkholderia cepacia. Infect Immun 66:874–877. doi: 10.1128/IAI.66.2.874-877.1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Miller VL, Mekalanos JJ. 1988. A novel suicide vector and its use in construction of insertion mutations: osmoregulation of outer membrane proteins and virulence determinants in Vibrio cholerae requires toxR. J Bacteriol 170:2575–2583. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.6.2575-2583.1988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Datsenko KA, Wanner BL. 2000. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97:6640–6645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.120163297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Figurski DH, Helinski DR. 1979. Replication of an origin-containing derivative of plasmid RK2 dependent on a plasmid function provided in trans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 76:1648–1652. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.4.1648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Dennis JJ, Zylstra GJ. 1998. Plasposons: modular self-cloning minitransposon derivatives for rapid genetic analysis of gram-negative bacterial genomes. Appl Environ Microbiol 64:2710–2715. doi: 10.1128/AEM.64.7.2710-2715.1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kodaka H, Armfield AY, Lombard GL, Dowell VR. 1982. Practical procedure for demonstrating bacterial flagella. J Clin Microbiol 16:948–952. doi: 10.1128/jcm.16.5.948-952.1982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kolmogorov M, Yuan J, Lin Y, Pevzner PA. 2019. Assembly of long, error-prone reads using repeat graphs. 5. Nat Biotechnol 37:540–546. doi: 10.1038/s41587-019-0072-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Schwengers O, Jelonek L, Dieckmann MA, Beyvers S, Blom J, Goesmann A. 2021. Bakta: rapid and standardized annotation of bacterial genomes via alignment-free sequence identification. Microbial Genomics 7:000685. doi: 10.1099/mgen.0.000685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Rationale for the construction of RhaCAST, Tables S1 and S2, and Figures S1 to S12.

Data Availability Statement

For ease of distribution, the following plasmids are deposited to Addgene: pZLrhaB2plus (#211787), pRhaCAST (#211791), pDonorTp (#211788), and pDonorTp-fugfp (#211790). All the genome sequences of the mutants from this study are available in the NCBI database under BioProject PRJNA1041412.