ABSTRACT

Bacterial and fungal copper radical oxidases (CROs) from Auxiliary Activity Family 5 (AA5) are implicated in morphogenesis and pathogenesis. The unique catalytic properties of CROs also make these enzymes attractive biocatalysts for the transformation of small molecules and biopolymers. Despite a recent increase in the number of characterized AA5 members, especially from subfamily 2 (AA5_2), the catalytic diversity of the family as a whole remains underexplored. In the present study, phylogenetic analysis guided the selection of six AA5_2 members from diverse fungi for recombinant expression in Komagataella pfaffii (syn. Pichia pastoris) and biochemical characterization in vitro. Five of the targets displayed predominant galactose 6-oxidase activity (EC 1.1.3.9), and one was a broad-specificity aryl alcohol oxidase (EC 1.1.3.7) with maximum activity on the platform chemical 5-hydroxymethyl furfural (EC 1.1.3.47). Sequence alignment comparing previously characterized AA5_2 members to those from this study indicated various amino acid substitutions at active site positions implicated in the modulation of specificity.

IMPORTANCE

Enzyme discovery and characterization underpin advances in microbial biology and the application of biocatalysts in industrial processes. On one hand, oxidative processes are central to fungal saprotrophy and pathogenesis. On the other hand, controlled oxidation of small molecules and (bio)polymers valorizes these compounds and introduces versatile functional groups for further modification. The biochemical characterization of six new copper radical oxidases further illuminates the catalytic diversity of these enzymes, which will inform future biological studies and biotechnological applications.

KEYWORDS: carbohydrate-active enzyme, Auxiliary Activity Family 5, copper radical oxidase, galactose oxidase, alcohol oxidase, HMF oxidase

INTRODUCTION

There is an increasing emphasis on the advancement of a circular (bio)economy, including the development of more sustainable materials and industrial processes, due to the negative environmental impacts that result from our overconsumption of non-renewable resources (1–5). One avenue to address this is to utilize enzymes as bio-based catalysts. Enzyme discovery continues to play an important role toward the development of efficient enzymes for more environmentally friendly industrial applications (6–8). In particular, oxidative reactions encompass several important chemical transformations utilized in the pharmaceutical, agricultural, and biofuel industries, to name a few. Replacement of chemical oxidants, many of which produce hazardous waste, with oxidase enzymes as industrial (bio)catalysts is particularly attractive due to the low-risk waste streams and milder reaction condition requirements associated with enzymes (9, 10).

In this context, copper radical oxidases (CROs), which comprise Auxiliary Activity Family 5 (AA5) within the carbohydrate-active enzymes classification (11, 12), have become attractive targets as biocatalysts (13, 14). CROs catalyze the two-electron oxidation of primary alcohols or aldehydes (gem-diols) to their corresponding aldehyde or carboxylic acid products, respectively, using O2 as a terminal electron acceptor, generating H2O2 as a co-product. Within the active site, CROs coordinate a mononuclear copper metal center, which is redox-coupled to a unique crosslinked tyrosyl-cysteinyl radical co-factor (15, 16). Fungal CROs constitute two subfamilies of AA5: Subfamily 1 (AA5_1), which contains glyoxal oxidases first discovered in 1987 from the white rot fungus, Phanerochaete chrysosporium (17), and Subfamily 2 (AA5_2), which includes the archetypal galactose-6-oxidase (FgrGalOx) from the wheat blight pathogen, Fusarium graminearum (18, 19). There are also AA5 CROs, including those from bacteria and plants, that do not fall into these two originally defined subfamilies (11, 13).

Since its discovery in the 1960s, FgrGalOx has been utilized for a wide range of biotechnological applications, such as the functional modification of galactose-containing polysaccharides for the development of functional materials (20–23), glycoprotein labeling (24–26), drug development (27, 28), production of flavor or fragrance compounds (29–31), etc.

Despite this decades-long history, enzymological research on AA5_2 has focused exclusively on FgrGalOx and close Fusarium homologs. In 2015, two Colletotrichum AA5_2 enzymes (CgrAlcOx and CglAlcOx) were discovered, which preferentially oxidized aliphatic alcohols over galactose-containing substrates (32). Since then, several other AA5_2 enzymes have been characterized, revealing a broad substrate specificity within the subfamily that can be categorized into three catalytic classes: traditional galactose-6-oxidases (GalOx, EC 1.1.3.12) (16), general alcohol oxidases (AlcOx, EC 1.1.3.7) (32), and aryl alcohol oxidases (AAO, EC 1.1.3.37) (33). Although a significant amount of CRO research has centered on their potential as biocatalysts, recent studies have also uncovered the biological importance of CROs in cell wall morphogenesis and as virulence factors in phytopathogenesis (34–39). Sustained interest in exploiting the diverse substrate scope of CROs for industrial biocatalysts, together with advancing our understanding of their biological roles, motivates further exploration of the AA5_2 sequence space.

Although the number of characterized AA5_2 members has significantly increased over the last few years [(32, 33, 40–44), reviewed in references (13, 14)], the subfamily remains largely underexplored (Fig. 1). To address this, phylogenetic analysis of AA5_2 sequences was performed to guide the selection of six new targets from several uncharacterized monophyletic groups for recombinant expression and subsequent biochemical characterization to reveal their activities.

Fig 1.

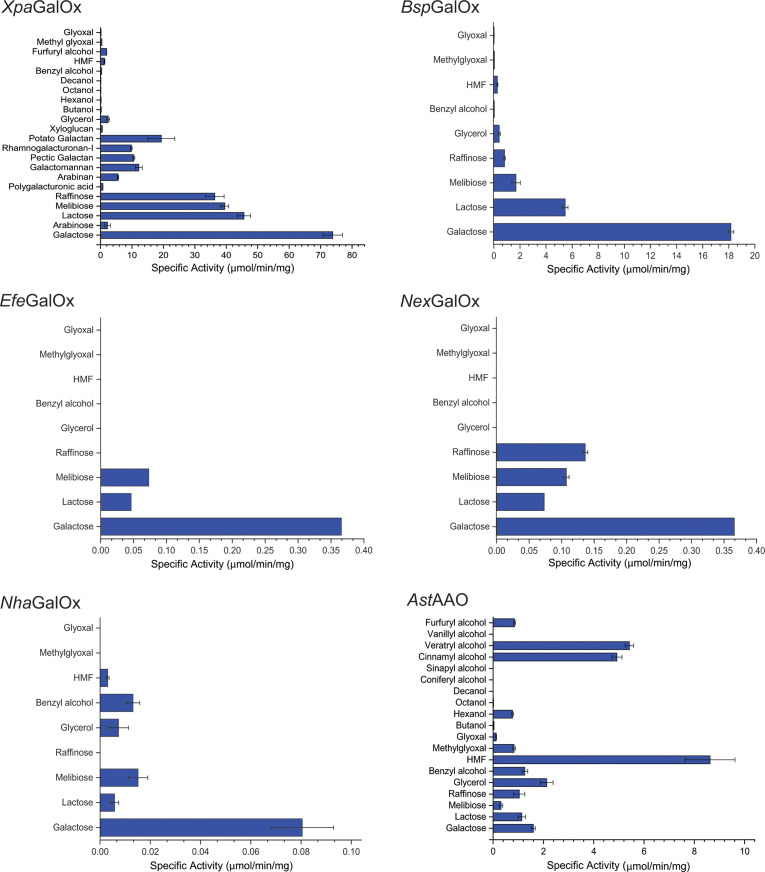

Specific activities of AA5_2 members on representative compounds. Individual values are presented in Table S2. Specific activity was determined using the HRP-ABTS-coupled assay with 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.0, at room temperature, except for NexGalOx (50 mM sodium acetate buffer, pH 5.0). Measurements were performed in triplicate with 300 mM carbohydrates (galactose, lactose, melibiose, and raffinose), 300 mM glycerol, 10 mM aromatic alcohols [benzyl alcohol and 5-hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF)], and 10 mM aldehydes (methyl glyoxal and glyoxal). Nha, Nectria haematococca; Efe, Epichloe festucae; Nex, Niesslia exilis; Ast, Acremonium strictum; Bsp, Bisporella sp.; and Xpa, Xanthoria parietina.

RESULTS

Target selection and recombinant protein production

We presented previously a maximum likelihood (ML) phylogeny of 623 manually curated AA5_2 catalytic modules grouped into 38 clades, which was used to select targets for recombinant production and enzymatic characterization (40). Previously characterized AA5_2 members are broadly distributed around the tree (Fig. S1). Here, six AA5_2 targets were selected from distantly related (distal) and closely related (adjacent) clades to those of well-studied members to diversify the coverage of AA5_2. Targets chosen from the uncharacterized Clades 5 and 13 originate from Bisporella sp. (Bsp) and Epichloe festucae (Efe), both of which are plant endophytes, whereas the AA5_2 from the uncharacterized Clade 12 is from Niesslia exilis (Nex), a saprophytic fungus. An AA5_2 from the lichen-forming fungus, Xanthoria parietina (Xpa), was chosen from Clade 3, which contains one characterized AA5_2 [MreGalOx (40)]. Two AA5_2 targets from the fungi Acremonium strictum (Ast) and Nectria haematococca (Nha) were also chosen from Clade 14, which contains several well-characterized galactose and alcohol oxidases from different Fusarium species [FveGalOx (45), FsuGalOx (46), FoxAlcOx (40), FoxAAO, and FgrAAO (41)].

All of the targets were successfully produced as secreted, hexahistidine-tagged proteins from Komagataella pfaffii (syn. Pichia pastoris) KM71H and purified via immobilized mobile affinity chromatography (Fig. S2). Typical protein yields using baffled shake-flasks ranged between 6 and 25 mg/L (Table S1). Treatment with PNGaseF under denaturing conditions resulted in changes in electrophoretic mobility corresponding to 3–19 kDa, indicating the presence of N-glycosylation on all of the purified AA5_2 enzymes (Fig. S2).

Initial biochemical characterization

Activities of the recombinantly produced AA5_2 enzymes were screened with an initial panel of representative substrates known to be oxidized by AA5 members, i.e., galactose, lactose, melibiose, raffinose, glycerol, benzyl alcohol, 5-hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF), methyl glyoxal, and glyoxal. Based on previous observations with other AA5 members (33, 40, 41), screening assays were performed at room temperature and sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.0. Most of the AA5_2 targets demonstrated canonical galactose-6-oxidase activity (EC 1.1.3.12) on galactose and galactosides. The exception was the AA5 member from Acremonium strictum, which was most active on HMF, indicative of general aryl alcohol oxidase (EC 1.1.3.37) activity (33, 40).

Galactose or HMF, as appropriate, was then used to determine the pH rate and temperature stability profiles for each CRO (Fig. S3 to S5). Generally, the enzyme targets displayed optimal activity between pH 6 and 8 in sodium phosphate buffer with approximately bell-shaped pH-rate profiles (Fig. S3), as observed for other characterized AA5_2 members (32, 33, 40–44). Exceptions were NhaGalOx, which displayed a sharp activity increase between pH 7.5 and 8.5, and NexGalOx, which was most active in sodium acetate buffer at pH 5. In general, the AA5_2 targets were stable at 30°C, similar to previously characterized CROs and consistent with the mesophilic nature of their source fungi (Fig. S4 and S5). Interestingly, EfeGalOx retained full activity after 48 h of incubation at 50°C.

Substrate specificities

Based on the specific activity values observed for each enzyme, additional substrates were screened. For XpaGalOx, the most active galactose oxidase, this panel was expanded to include polysaccharides and alkanols, while for AstAAO, additional aryl alcohols were assayed (Fig. 1; Table S2). A selection of the best substrates was subjected to detailed Michaelis-Menten kinetic analysis (Table 1; Fig. S6 to S9) at conditions (pH and temperature) based on the optima observed for each enzyme. These data are discussed for each CRO in the following sections.

TABLE 1.

Michaelis-Menten kinetic parameters for selected substrates

| Enzyme | Substrate | KM (mM) | kcat (s−1) | kcat/KM (M−1 s−1) | pH | Temperature (°C) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FgrGalOx | Galactose | 82 | 503 | 6,370 | (47) | ||

| 102 | 1,060 | 10,400 | (48) | ||||

| XpaGalOx | Galactose | 10 ± 0.2 | 241 ± 2 | 24,100 | 6.5 | 25 | This work |

| Lactose | 58.4 ± 0.4 | 190 ± 2 | 3,250 (1,500)a |

||||

| Melibiose | 19.7 ± 2.8 (23.9 ± 5.5)b |

206 ± 9 (234 ± 25)b |

10,460 (9,790)b |

||||

| Raffinose | 6.9 ± 0.3 | 189 ± 4 | 27,400 | ||||

| Glycerol | (76)a | ||||||

| HMF | (330)a | ||||||

| BspGalOx | Galactose | 36.3 ± 1.4 | 52.1 ± 0.2 | 1,420 | 6.0 | 25 | This work |

| Lactose | 186 ± 10 | 16.5 ± 0.6 | 89 (72)a |

||||

| Melibiose | 140 ± 7 | 13 ± 0.3 | 93 (54)a |

||||

| Raffinose | 156 ± 6 | 8.4 ± 0.2 | 54 (51)a |

||||

| Glycerol | (3)a | ||||||

| EfeGalOx | Galactose | 8.2 ± 1.8 (8.1 ± 2.5)b |

0.7 ± 0.1 (0.7 ± 0.1)b |

85 (86)b |

8.5 | 50 | This work |

| NexGalOx | Galactose | 828 ± 78 | 7.5 ± 0.6 | 9 (7.2)a |

5.0 | 30 | This work |

| NhaGalOx | Galactose | 930 ± 98 | 4.3 ± 0.4 | 5 (4)a |

8.0 | 30 | This work |

| AstAAO | Galactose | 931 ± 138 | 13.8 ± 1.3 | 15 (14)a |

7.5 | 30 | This work |

| Lactose | (6)a | ||||||

| Melibiose | 486 ± 68 | 2.1 ± 0.2 | 4 (3)a |

||||

| Raffinose | 75.3 ± 2.6 | 2.8 ± 0.1 | 37 (30)a |

||||

| Glycerol | 1,697 ± 163 | 30.6 ± 2.2 | 18 (18)a |

||||

| Hexanol | 2 ± 7.5 | 8.3 ± 0.7 | 130 (107)a |

||||

| Benzyl alcohol | (230)a | ||||||

| HMF | 2.0 ± 1.0 (9.4 ± 1.0)b |

24.9 ± 1.4 (42.7 ± 2.2)b |

12,400 (4,540)b |

||||

| Cinnamyl alcohol | 11.6 ± 1.0 | 43.8 ± 1.5 | 3,780 (4,800)a |

||||

| Veratryl alcohol | 1.8 ± 0.3 (6.4 ± 0.8)b |

16.5 ± 1.5 (38.3 ± 2.6)b |

9,160 (5,980)b |

||||

| Furfuryl alcohol | 24.0 ± 3.7 | 15.6 ± 1.7 | 650 (510)a |

||||

| Methylglyoxal | 45 ± 11 | 6.8 ± 1.2 | 150 (119)a |

||||

| Glyoxal | (15)a |

Values in parentheses correspond to kcat/KM values determined from the slopes of linear fits to initial-rate kinetic data substrate concentrations well below saturation (see Fig. S6 to S9); individual KM and kcat values were not calculated.

Kinetic parameters were obtained by fitting a modified Michaelis-Menten equation including a term for substrate inhibition.

XpaGalOx

The lichen-forming symbiotic fungus, Xanthoria parietina (Xpa), commonly associates with green algae and has found use as a biomonitor for the qualitative detection of environmental metal pollution due to its robust tolerance to heavy metals (49). X. parietina encodes an AA5_2 member, XpaGalOx, which is in the divergent Clade 3 (Fig. 1) together with a recently characterized galactose oxidase [MreGalOx (40)] with which it shares 59% sequence identity. Similarly, XpaGalOx shares 58% identity with FgrGalOx (19) (Table S1). Initial activity screens with a small panel of representative substrates showed that XpaGalOx had the highest specific activity on galactose and was relatively good at oxidizing galacto-oligosaccharides such as lactose, melibiose, and raffinose. XpaGalOx also exhibited low specific activities on glycerol, benzyl alcohol, and, interestingly, the classic AA5_1 substrate, methyl glyoxal (Fig. 2). Based on the high specific activities observed on galacto-oligosaccharides, the substrate panel was extended to more relevant plant-based carbohydrates. The activity was detected on arabinose, arabinan, galactomannan, galactan, and rhamnogalacturonan-I (Fig. 1). Initial rate kinetics showed that XpaGalOx had comparable catalytic efficiencies for galactose and raffinose (Table 1). XpaGalOx also showed good catalytic efficiency for melibiose. As listed in Table 2, XpaGalOx displayed a kcat value, which was two- and fourfold lower than the reported values for FgrGalOx [503 s−1 (47) and 1,060 s−1 (48)]. Interestingly, XpaGalOx showed a 10-fold decrease in the KM for galactose, which resulted in a two- and fourfold increase in specificity compared to the archetype, FgrGalOx, which has reported kcat/KM values of 6,370 M−1 s−1 (47) and 10,400 M−1 s−1 (48), respectively.

Fig 2.

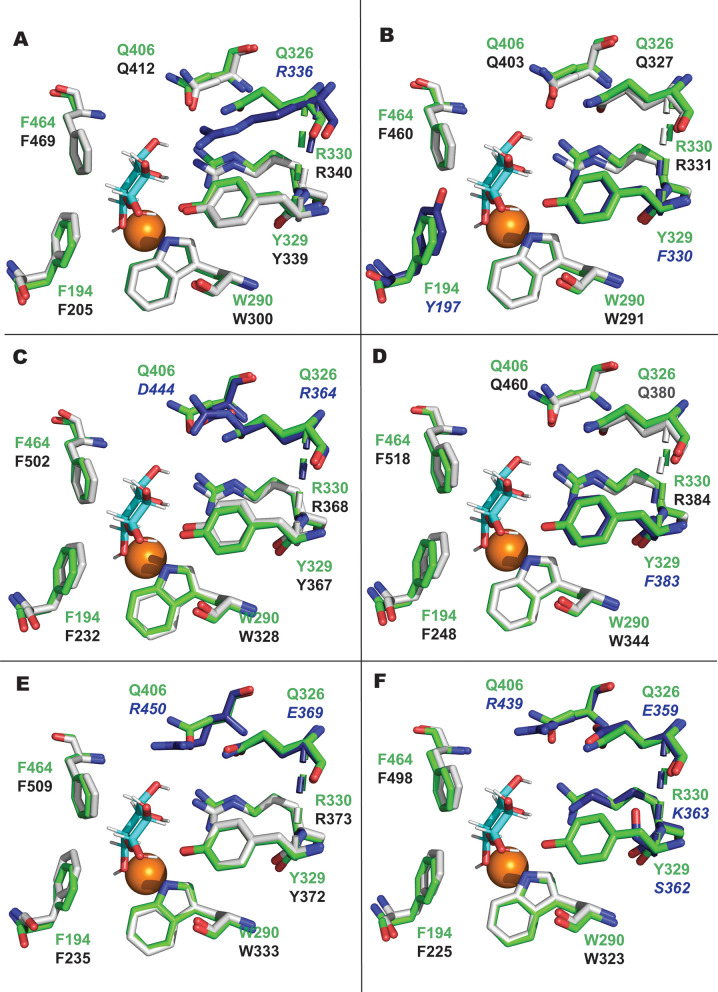

Tertiary structural comparison of AA5 CRO active sites. Structural models of (A) XpaGalOx, (B) BspGalOx, (C) EfeGalOx, (D) NexGalOx, (E) NhaGalOx, and (F) AstAAO were generated with AlphaFold3 (73) and superposed with an experimental structure of FgrGalOx [PDB 1gof (19), green amino acids], into which galactose was docked previously (40). Conserved residues within respective AA5_2 members from this work are shown as gray sticks with black labels, while non-conserved residues are displayed as blue sticks and labels. Galactose and copper are shown as cyan sticks and orange spheres, respectively. In all cases, AlphaFold did not generate the corresponding active-site Cys-Tyr crosslink (19), but modeled these as two independent sidechains; this did not affect the overall analysis.

TABLE 2.

Comparison of amino acid substitutions in key active site positions of several characterized AA5_2 members and the archetype FgrGalOxa

| Enzyme | Organism | Active site amino acids | GenBank/JGI accession | Reference | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Radical stabilization | Active site shape/substrate recognition | |||||||||

| FgrGalOx | Fusarium graminearum | W290 | F194 | Q326 | Y329 | R330 | Q406 | F464 | AAO95371 | (16, 19) |

| FsaGalOx | Fusarium sambucinum | W | F | Q | Y | R | Q | F | AIR07394 | (50) |

| FauGalOx | Fusarium austro- americanum | W | F | Q | Y | R | Q | F | AAA16228 | (45) |

| MreGalOx | Mytilinidion resinicola | W | F | Q | F | R | Q | F | XP_033570565 | (40) |

| ExeGalOx | Exophiala xenobiotica | W | F | Q | F | R | Q | F | KIW55415 | (40) |

| FoxGalOxB | Fusarium oxysporum | W | M | Q | F | R | Q | F | FOTG_04629 | (40) |

| PfeGalOx | Penicillium fellutanum | W | Y | Q | Y | R | Q | F | jgi|Penfe1|382062 | (40) |

| Xpa GalOx | Xanthoria parietina | W | F | R | Y | R | Q | F | jgi|Xanpa2|1578647 | This work |

| Bsp GalOx | Bisporella spp. | W | Y | Q | F | R | Q | F | jgi|Bissp1|110239 | This work |

| Efe GalOx | Epichloe festucae | W | F | R | Y | R | D | F | ACN30267 | This work |

| Nex GalOx | Niesslia exilis | W | F | Q | F | R | Q | F | jgi|Nieex1|192818 | This work |

| Nha GalOx | Nectria haematococca | W | F | E | Y | R | R | F | XP_003039318 | This work |

| FveGalOx | Fusarium verticillioides | W | F | E | Y | K | Q | F | ADG08188 | (45) |

| FsuGalOx | Fusarium subglutinans | W | F | E | Y | K | Q | F | ADG08187 | (46) |

| Pru AlcOx/GalOx | Penicillium rubens | W | Y | D | Y | R | E | F | CAP96757 | (40, 43) |

| CgrRafOx | Colletotrichum graminicola | Y | F | A | W | R | S | F | EFQ36699 | (42) |

| CgrAlcOx | Colletotrichum graminicola | F | W | G | F | M | T | F | EFQ30446 | (32) |

| CglAlcOx | Colletotrichum gloeosporioides | F | W | L | F | M | T | F | jgi|Gloci1|1901294 | (32, 40) |

| PorAlcOx | Pyricularia oryzae | F | F | G | L | Y | T | F | XP_003719369 | (40) |

| AsyAlcOx | Aspergillus sydowii | F | Y | H | D | R | V | F | XP_040706357 | (40) |

| AflAlcOx | Aspergillus flavus | W | Y | L | Y | H | E | F | KAF7627372 | (40) |

| FoxAlcOx | Fusarium oxysporum | W | F | D | S | K | A | F | EXL65576 | (40) |

| FoxAAO | Fusarium oxysporum | W | F | E | Y | K | Q | F | XP_018246910 | (41) |

| FgrAAO | Fusarium graminearum | W | F | E | Y | K | Q | F | XP_011322138 | (41) |

| CgrAAO | Colletotrichum graminicola | Y | F | E | W | R | T | F | EFQ27661 | (33) |

| Ast AAO | Acremonium strictum | W | F | E | S | K | R | F | jgi|Acrst|1377707 | This work |

Conserved residues in relation to FgrGalOx are indicated in bold font and non-conserved residues are indicated in italic font, based on primary and tertiary structural alignments. AA5_2 members characterized in this present study are indicated in underlined, bold font.

The product(s) following galactose oxidation by XpaGalOx were assessed after the incubation of 300 mM of galactose with XpaGalOx. The proton nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectrum of the reaction showed that XpaGalOx oxidized the C6-OH of galactose with 35% conversion to produce the corresponding aldehyde (Fig. S10), typical of galactose 6-oxidases (EC 1.1.3.9).

BspGalOx

Bisporella sp. is a widespread saprobic ascomycete, which is also frequently isolated as a plant endophyte (51). The protein encoded by Bsp_PMI857 (JGI accession) is located in Clade 5, which contains no other characterized members (Fig. S1). BspGalOx shares 55% sequence identity with FgrGalOx (19) (Table S1). BspGalOx exhibited the highest specific activity on galactose and lower activities on galacto-oligosaccharides. Minimal activities were also observed on glycerol and HMF (Fig. 1). Although BspGalOx was most active on galactose and had a lower KM value for galactose, it demonstrated a 5- and 10-fold lower catalytic efficiency for galactose compared to the reported values of 6,370 M−1 s−1 (47) and 10,400 M−1 s-1 (48), respectively, for FgrGalOx (Table 1). Catalytic efficiencies of BspGalOx for lactose, melibiose, and raffinose were 15, 15, and 25 times lower, respectively, compared to galactose (Table 1).

EfeGalOx

Epichloe festucae is an endophytic fungus associated with cool-season grasses, often conferring insect resistance to grass hosts due to the production of toxic alkaloids (52). EfeGalOx is located alone in Clade 13 and shares 65% sequence identity with FgrGalOx (19) (Fig. S1; Table S1). The adjacent Clade 14 contains several characterized members from various Fusarium species [FveGalOx (45), FsuGalOx (46), FoxAlcOx (40), FoxAAO, and FgrAAO (41)]. Initial activity screens showed that galactose was the best substrate for EfeGalOx, and minimal activity was observed on lactose and melibiose. No activity was detected on raffinose, glycerol, benzyl alcohol, and HMF nor was there any activity on the classic AA5_1 substrates, methyl glyoxal and glyoxal (Fig. 1). Although the highest specific activity was observed on galactose, initial rate kinetics showed that EfeGalOx had a 120-fold lower catalytic efficiency for galactose, compared to FgrGalOx (Table 1). Notably, EfeGalOx had a KM value for galactose that was 10-fold lower than that of FgrGalOx. Despite this, a significantly lowered kcat resulted in a ca. 100-fold lower kcat/KM value compared to FgrGalOx (Table 2).

NexGalOx

The fungus Niesslia exilis is a saprotrophic filamentous fungus that inhabits decaying plant matter such as leaf litter or woody debris (53). NexGalOx is in Clade 12, which contains no other characterized members, and is adjacent to Clade 13, which contains the aforementioned EfeGalOx (Fig. S1). NexGalOx shares 60% and 65% sequence identity with EfeGalOx and FgrGalOx (19), respectively (Table S1). Low specific activities were measured on galactose and galacto-oligosaccharides (lactose, melibiose, and raffinose), and no activity was observed on glycerol, benzyl alcohol, HMF, methyl glyoxal, and glyoxal, similar to the substrate profile of EfeGalOx (Fig. 1). A higher KM value and lower kcat value resulted in catalytic efficiencies for galactose that were over 700-fold lower compared to FgrGalOx (Table 1).

NhaGalOx

Nectria haematococca (asexual form: Fusarium solani) is one of over 50 members of the Fusarium solani species complex (54). Members of this complex are known to cause disease in over 100 genera of plants. NhaGalOx is located in Clade 14, which also contains the Fusarium CROs FveGalOx (45), FsuGalOx (46), FoxAAO, FgrAAO (41), and FoxAlcOx (40), as well as AstAAO discussed below (Fig. S1). NhaGalOx shares 71% sequence identity with FgrGalOx (19). Similarly, NhaGalOx also shares 70% identity with FoxAAO, FgrAAO, and FoxAlcOx from the same clade (Fig. S1). The highest specific activity was measured on galactose, with lower levels of activity detected on lactose, melibiose, glycerol, benzyl alcohol, and HMF; no activity was detected on methyl glyoxal and glyoxal (Fig. 1). Despite the low specific activities measured, the broad substrate profile of NhaGalOx validates the grouping of Fusarium AA5_2 homologs in Clade 14. Although NhaGalOx was most active on galactose, initial rate kinetics show that a combination of higher KM and lower kcat values (Table 1) resulted in a catalytic efficiency on galactose that was over 1,000 times lower than that of FgrGalOx.

AstAAO

Acremonium strictum is an environmentally widespread soil-dwelling saprotroph that has also been shown to be involved in a range of plant endophytic and parasitic relationships. A. strictum has also been reported to be an opportunistic human pathogen, infecting immunocompromised patients (55, 56). AstAAO is in Clade 14 together with the aforementioned NhaGalOx and several characterized Fusarium CROs (Fig. S1). AstAAO shares 65% and 69% sequence identity with FgrGalOx (19) and NhaGalOx, respectively. Comparable to NhaGalOx, AstAAO shares 72% sequence identity with FoxAAO, FgrAAO (41), and FoxAlcOx (40) (Table S1). Initial activity screens showed that AstAAO was most active on HMF and had lower specific activities on carbohydrates. As such, the substrate panel was extended to include other aliphatic and aromatic alcohols (Fig. 1). Activity was detected on cinnamyl alcohol, veratryl alcohol, and furfuryl alcohol. Interestingly, activity was detected on hexanol but not on butanol, octanol, and decanol. Activity was also detected on methylglyoxal and glyoxal, which are typical substrates of AA5_1 CROs (Fig. 1). Initial rate kinetics showed that AstAAO has comparable catalytic efficiencies on HMF, cinnamyl alcohol, and veratryl alcohol (Table 1). Substrate inhibition was also observed for several substrates, namely HMF and veratryl alcohol (Fig. S9). In comparison with characterized AA5_2 CROs, AstAAO showed a similar substrate profile to that of CgrAAO (33) from Colletotrichum graminicola, despite sharing only 46% sequence identity (Table S1). Like CgrAAO, the catalytic efficiency of AstAAO for galactose was 700-fold lower than the highest reported kcat/KM value of 10,400 M−1 s−1 for FgrGalOx (48). Although HMF was one of the best substrates for AstAAO, its catalytic efficiency was four times lower than that of CgrAAO for HMF. Interestingly, despite being several fold less efficient on many CgrAAO substrates, AstAAO had a comparable catalytic efficiency for veratryl alcohol.

HMF is an important biomass-derived platform chemical, which can yield several useful chemical building blocks through its partial or complete oxidation. These include 2,5-dimethylfuran (DFF), 5-hydroxy-2-furancarboxylic acid, 5-formyl-2-furancarboxylic acid (FFCA), and 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid (FDCA) (57, 58). Individual AA5_2 CROs have been reported to oxidize HMF to varying degrees. For instance, CgrAAO (33), FgrAAO (41), and CgrAlcOx (32) oxidize HMF to DFF, a mixture of DFF/FFCA and a mixture of FFCA/FDCA, respectively. Proton NMR analysis indicated that AstAAO oxidized HMF to DFF and FFCA in the ratio of 60:40 (Fig. S11).

DISCUSSION

Enzyme discovery plays an important role in advancing green chemistry and the development of a sustainable bioeconomy (59, 60). Oxidation chemistry constitutes ca. 30% of industrial chemical transformations (10); thus, the discovery and characterization of diverse CROs can stimulate the development of new oxidative biocatalysts. Indeed, an engineered CRO was central to the recent industrial development of a biocatalytic pathway to produce a key antiviral drug (61), and efforts continue to be focused on optimizing CRO catalysis and expanding CRO substrate specificities (28, 62, 63); see also reference (13). In parallel, as CROs are implicated in fungal morphogenesis and phytopathogenesis (34, 35), understanding CRO biochemistry, therefore, underpins understanding their roles in biology and potential as targets in the development of strategies to combat plant disease.

In the present study, six new CROs from a range of AA5_2 phylogenetic clades were biochemically characterized. Five were demonstrated to be canonical galactose-6-oxidases (XpaGalOx, BspGalOx, EfeGalOx, NexGalOx, and NhaGalOx) and one to be an aryl alcohol oxidase (AstAAO). As shown previously by our group (40) and elaborated here, AA5_2 sequences separate into 38 well-supported clades with high bootstrap values (Fig. S1). However, the inclusion of the newly characterized members in this phylogeny further illustrates that galactose-specific (EC 1.1.3.12) and general alcohol oxidase activities (EC 1.1.3.7, EC 1.1.3.37, and EC 1.1.3.47) are dispersed throughout numerous clades and are not monophyletic. This likely reflects the high overall sequence identity and similarity observed in the family as a whole (Table S1), which confounds functional prediction.

No substrate or product complexes of AA5 members have been solved, so direct information on active-site interactions is currently lacking (19, 32, 33, 37, 64). However, site-directed mutagenesis and in silico studies have implicated several key active site residues in the modulation of substrate specificity (47, 65–67). Yet, these studies also indicate that substrate specificity cannot be readily attributed to the effects of any specific amino acids in a predictable manner. Substrate specificity may instead be due to a complex interplay between several factors, such as steric factors and hydrogen-bonding capabilities of amino acid side chains constituting the active site. To place the CROs from the present study in the context of previously characterized AA5_2 members, Table 2 and Fig. 2 present a comparison of key active site residues first established in FgrGalOx.

Early work has established the roles that tryptophan (W290 in FgrGalOx) in the second coordination sphere plays in the stabilization of the tyrosyl-cysteinyl radical cofactor and binding of galactose (47). More recently, mutagenesis of the corresponding tyrosine in the Colletotrichum aryl alcohol oxidase, CgrAAO, to tryptophan (Y334W) greatly reduced activity on all aryl alcohols and greatly boosted activity on galactose-containing carbohydrates (33). The galactose 6-oxidases characterized in this work all contained a tryptophan in the position corresponding to W290 in FgrGalOx. Interestingly, AstAAO also possessed a tryptophan in this position, despite primarily oxidizing aryl alcohols (Table 2; Fig. 2F).

Other key residues include Y329 and R330 in FgrGalOx (Table 2; Fig. 2), which are predicted to bind the C1-OH and C3-/C4-OH of galactose (40, 48, 66). The position corresponding to R330 in FgrGalOx appears to be a strong modulator of substrate preference: the majority of characterized galactose oxidases retain this arginine (Table 2). Yet, some alcohol oxidases, i.e., CgrAAO (33) and AsyAlcOx (40), also retain this arginine but substitute the second-shell tryptophan with tyrosine and phenylalanine, respectively. Also notable is that PruAlcOx retains the corresponding tryptophan/arginine pair and has similar activity on galactose and other alcohols (40). This suggests that the R330 position in FgrGalOx is necessary but not sufficient for determining galactose activity. Indeed, the growing body of data suggests that the tryptophan/arginine pair, corresponding to W290 and R330 in FgrGalOx, are the key indicators of galactose 6-oxidase activity although the modulation of activity levels may involve more complex factors. For example, NexGalOx and NhaGalOx, which have the W290/R330 pair, display galactose oxidase activity but are significantly less efficient at turning-over galactose when compared to FgrGalOx.

F194 and F464 in FgrGalOx (Table 2; Fig. 2) are proposed to provide a hydrophobic surface for interactions with galactose. Molecular modeling and site-directed mutagenesis suggest that F464, in particular, forms aromatic stacking interactions with the galactose ring (48). Interestingly, F464 (in FgrGalOx) is conserved in all characterized CROs and is therefore not an indicator of GalOx, AlcOx, or AAO activity (Table 2). The position corresponding to F194 in FgrGalOx, which is variably substituted with other aromatic residues among the characterized CROs (Tyr and Trp; Met in FoxGalOxB is anomalous), also does not correlate with substrate scope (Table 2).

Regarding the position corresponding to Y329 in FgrGalOx, this residue is variably substituted by phenylalanine in other GalOxs [ExeGalOx, MreGalOx, and FoxGalOxB (40), and BspGalOx and NexGalOx (this work)]. All the aforementioned galactose oxidases had lower catalytic efficiencies for galactose compared to FgrGalOx, which suggests that substitution of tyrosine to phenylalanine may affect overall levels of activity rather than modulate substrate preference. Interestingly, some alcohol oxidases, e.g., CgrAlcOx (32) and CgrAAO (33), also have aromatic substitutions at this position, while others [FoxAlcOx, PorAlOx, and AsyAlcOx (40)] contain non-aromatic residues. For example, AstAAO from the present study has a serine in place of the tyrosine.

The glutamine residues in positions Q326 and Q406 in FgrGalOx are also noteworthy (66–68). Loss of one or both glutamines is generally, but not exclusively (e.g., EfeGalOx), correlated with a loss of GalOx activity. A recent study on the engineering of CgrAlcOx has shown that these glutamines increase affinity for galactose, likely through hydrogen bonding (65). Interestingly, XpaGalOx, which has a twofold higher catalytic efficiency and 10-fold lower KM on galactose compared to FgrGalOx (Table 1), contains an arginine at the position corresponding to Q326 in FgrGalOx (Table 2; Fig. 2A). Two other galactose oxidases from our present study (EfeGalOx and NhaGalOx) with over 100-fold lower catalytic efficiency on galactose contained Arg and Glu substitutions, respectively, at the position corresponding to Q326 in FgrGalOx. Like XpaGalOx, EfeGalOx (Table 2; Fig. 2C) also contains an Arg substitution at the Q326 (FgrGalOx) position and has a KM value for galactose that is 10 times lower than FgrGalOx. The longer Arg residue could potentially extend further into the binding site to form additional hydrogen bonds that may improve galactose binding. EfeGalOx and NhaGalOx also contained Asp and Arg substitutions, respectively, at position Q406 in FgrGalOx.

Conclusion

The characterization of six new fungal AA5_2 orthologs in this study contributes comparative biochemical data that helps to refine the understanding and prediction of the catalytic potential of CROs. On one hand, the expansion of characterized CROs provides valuable information to guide enzyme selection for biocatalytic applications and further protein engineering efforts. On the other hand, this in vitro structure-function data can inform the identification of the true physiological substrates of CROs in vivo, which are generally unknown but integral to microbiology and phytopathogenesis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals and enzymes

All substrate stocks and buffer solutions were prepared with Ultrapure water (18.2 Ω) unless otherwise stated. Lyophilized powders of catalase from bovine liver (2,000–5,000 units/mg, Sigma) and horseradish peroxidase (Rz > 3.0, BioBasic Canada, Inc.) were used as received. All substrates and reagents were purchased from commercial sources (Sigma-Aldrich, VWR, or Fisher) and used without further purification.

Sequence analysis and bioinformatics

A previous ML phylogenetic tree comprising 623 AA5_2 catalytic modules omitting any accessory modules (40) was used to select six uncharacterized AA5_2 sequences. AlphaFold 3 (69) was used to generate structural homology models of the target AA5_2 CROs with a copper ion, using the AlphaFold Server at https://golgi.sandbox.google.com/.

DNA cloning and recombinant strain production

cDNA encoding the mature AA5_2 proteins, including any accessory modules, but without signal peptides, was commercially synthesized (Genewiz) and cloned directly into pPICZαA or pPICZαC using the EcoRI, ClaI, and XbaI restriction sites in flush with the sequence encoding the Saccharomyces cerevisiae α-factor signal peptide. The resulting constructs were transformed into chemically competent Escherichia coli DH5α by heat shock. Recombinant strains were produced as described in the Invitrogen EasySelect Pichia system manuals (Invitrogen). Briefly, 5 µg of recombinant plasmids containing target sequences were linearized with PmeI and transformed into Komagataella pfaffii (syn. Pichia pastoris) KM71H via electroporation. Transformed K. pastoris were spread on YPD agar plates containing 100 or 500 µg mL−1 of Zeocin. Zeocin-resistant transformants were isolated from plates.

Large-scale protein production and purification

Large-scale protein production and purification were performed as previously described (40). Briefly, single colonies of K. pastoris KM71H-expressing clones were streaked onto agar plates containing Zeocin (100 or 500 µg/mL) and grown in the dark for 2 days (30°C). Precultures of 5 mL YPD and 0.5 mg/mL Zeocin were inoculated with a single colony and shaken for 30°C at 250 rpm for 8 h, after which 1 L of BMGY media in 4 L baffled flasks was inoculated with the precultures and left to grow overnight at 30°C, 250 rpm. Once the BMGY cultures reached an OD600 of 6–12, the cells were harvested by centrifugation (20 min, 20°C, 4,000 rpm) and resuspended using 400 mL of BMMY media, supplemented with 0.5 mM CuSO4 (70) and 3% methanol (vol/vol), then transferred into 2 L baffled flasks and shaken at 250 rpm at 16°C for 3 days. The cultures were fed 1% (vol/vol) methanol every 24 h, and on day 3, secreted proteins were separated from cells by centrifugation at 4,500 rpm for 20 min at 4°C. The supernatant was decanted, and the pH was adjusted to 7.4–8.0 by dropwise additions of 5 M NaOH. The resulting liquid was filtered through a 0.45 µm membrane and allowed to equilibrate for at least 12 h at 4°C.

The supernatant was passed through a 5 mL pre-packed Ni-NTA column, pre-equilibrated with 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer at pH 7.4 with 500 mM NaCl and 10 mM imidazole at 5 mL/min. Proteins were eluted with a linear gradient of 0%–100% of 500 mM imidazole in a 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer with 500 mM NaCl at 5 mL/min. The total elution volume was collected in 1 mL fractions, and fractions of interest were pooled and concentrated using a 10,000 MWCO Vivaspin centrifugal concentrator. Concentrated protein fractions (maximum 2 mL) were loaded onto a Superdex 75 size exclusion column pre-equilibrated with 200 mL of 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer at pH 7.0. Total elution volume was collected as 1.5 mL fractions, and fractions of interest were pooled and concentrated as mentioned previously. The proteins were aliquoted, flash frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −70°C. SDS-PAGE was carried out using pre-cast 4%–20% (wt/vol) polyacrylamide gels in the presence of 2% (wt/vol) SDS under reducing conditions. Proteins were visualized using Coomassie blue R-250. Protein concentrations were determined by measuring A280 using extinction coefficients calculated with the ProtParam tool on the ExPASy server.

Analytical protein deglycosylation

The presence of protein N-glycosylation was assessed by treatment with N-glycosidase F from Flavobacterium meningosepticum (PNGaseF, New England Biolabs) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, deglycosylation experiments were performed under denaturing conditions by adding 5 µg pf protein to 10× Glycoprotein Denaturing Buffer and heated for 10 min at 100°C. The samples were subsequently diluted to 20 µL with GlycoBuffer 2 and tergitol-type NP-40 detergent. The samples were incubated for 1 h at 37°C after the addition of 1 µL of PNGaseF. Changes in protein mobility were assessed by SDS-PAGE stained and visualized by staining with Coomassie blue R-250. Molecular weights of proteins were estimated using a standard curve of the log (MW) versus Rf of the protein ladder (BLUelf).

Substrate screen

The activity of target enzymes was surveyed on a variety of substrates using the HRP-ABTS-coupled assay in a reaction volume of 200 µL of 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.0, 0.25 mg/mL ABTS, and 0.1 mg/mL HRP at room temperature in a 96-well plate. Absorbance was measured at 415 nm on the BioTek Epoch microplate spectrophotometer. Galactose, lactose, melibiose, raffinose, glycerol, benzyl alcohol, hydroxymethylfurfural, methylglyoxal, and glyoxal were screened as representative carbohydrates (300 mM), polyol (300 mM), aryl alcohol, and aldehyde (10 mM) substrates.

pH activity profile

Enzyme activity across a wide range of pH values was determined as described (40) using citrate-phosphate (pH 4.0–6.0), sodium phosphate (pH 6.0–8.5), glycine-NaOH (pH 8.0–9.5), and CHES (pH 9.0–10.5) buffers. Enzyme activity was measured using the HRP-ABTS-coupled assay in a 96-well plate format at room temperature (ca. 20°C) in 50 mM buffer with the best substrate as determined by the substrate screen (Fig. 1).

Temperature stability profile

Temperature stability profiles of the target enzymes were determined by first diluting the stock protein in 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer at the previously determined pH optimum. The diluted protein was then pre-incubated in a thermocycler set to maintain a temperature gradient between 30°C and 50°C. Samples were taken out at different time intervals and enzyme activity was measured using the HRP-ABTS-coupled assay in a 96-well plate assay at room temperature. The best substrate determined from the substrate screen (Fig. 1) was used to assay enzyme activity.

Michaelis-Menten kinetics

To determine the Michaelis-Menten parameters of the target enzymes, a range of substrate concentrations were used for each substrate. The reactions were performed using the coupled HRP-ABTS assay with 0.46 mM ABTS, 21 U/mL of HRP in 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer at pH between 6 and 8.5 and temperatures between 20°C and 30°C depending on pH profiles and temperature stability assays (except NexGalOx, which was assayed in 50 mM sodium acetate, pH 5.0). Measurements were made in 1 mL plastic cuvettes using the Cary 60 UV-VIS spectrometer. The Michaelis-Menten equation was fit to the data using OriginPro software (OriginLab 9.85)

Enzyme product analysis

HRP and catalase (1 mg/mL) were combined with 300 mM of galactose or 20 mM HMF in 50 mM sodium phosphate, pH 6.5, to a final volume of 1 mL. The reactions were initiated by adding 50 or 100 µg of purified XpaGalOx and AstAAO, respectively. For galactose oxidation, 0.1 mg/mL BSA was also added. The reactions were stirred at 400 rpm at room temperature for 24 h followed by enzyme removal through ultrafiltration (5 kDa cut-off Vivaspin column). Negative controls without additions of XpaGalOx or AstAAO were prepared. Filtrate from the galactose oxidation was lyophilized after which the dried powder was dissolved in D2O. D2O was added to the filtrate from the HMF oxidation to a final composition of 10% (vol/vol). NMR experiments were performed on a Bruker AVANCE 400 Hz spectrometer. Peaks were identified by comparison with reference spectra (33, 40, 71). Percentage conversion was calculated from integration values of relevant peak areas.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Maria Ezhova and Dr. Zhicheng Xia (UBC Department of Chemistry) for their support with NMR data acquisition. J.K.F. thanks Dr. Maria Cleveland for her support and guidance.

This study was funded by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (Discovery Grant RGPIN-2018-03892 and Strategic Partnership Grant STPGP 493781-16) and Genome Canada/Genome BC (Large-Scale Applied Research Project #10405). J.K.F. is funded by the NSERC-CREATE/DFG-IRTG training program “PRoTECT-Plant Responses To Eliminate Critical Threats” (CREATE 509257-18).

H.B. and Y.M. conceptualized the study. J.K.F., Y.M., M.T.V., and A.B. conducted experiments. J.K.F. analyzed the data. A.T. and H.B. supervised the study. J.K.F. and H.B. wrote the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Harry Brumer, Email: brumer@msl.ubc.ca.

Haruyuki Atomi, Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan.

DATA AVAILABILITY

All data generated and analyzed during this study are included in this article and the associated supplementary information files. All nucleotide sequences, protein sequences, and protein structural information used in this work were extracted from public databases, i.e., GenBank (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/), The Protein Data Bank (www.rcsb.org/), The CAZy database (www.cazy.org/), and JGI Mycocosm (mycocosm.jgi.doe.gov/mycocosm/home).

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

The following material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1128/aem.01014-24.

Tables S1 to S3; Figures S1 to S11.

ASM does not own the copyrights to Supplemental Material that may be linked to, or accessed through, an article. The authors have granted ASM a non-exclusive, world-wide license to publish the Supplemental Material files. Please contact the corresponding author directly for reuse.

REFERENCES

- 1. Wiedmann T, Lenzen M, Keyßer LT, Steinberger JK. 2020. Scientists' warning on affluence. Nat Commun 11:10. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-16941-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Marion P, Bernela B, Piccirilli A, Estrine B, Patouillard N, Guilbot J, Jérôme F. 2017. Sustainable chemistry: how to produce better and more from less?. Green Chem 19:4973–4989. doi: 10.1039/C7GC02006F [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tan ECD, Lamers P. 2021. Circular bioeconomy concepts—a perspective. Front Sustain 2. doi: 10.3389/frsus.2021.701509 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rosenboom JG, Langer R, Traverso G. 2022. Bioplastics for a circular economy. Nat Rev Mater 7:117–137. doi: 10.1038/s41578-021-00407-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kohli K, Prajapati R, Sharma BK. 2019. Bio-based chemicals from renewable Biomass for integrated biorefineries. Energies 12:233. doi: 10.3390/en12020233 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Heckmann CM, Paradisi F. 2020. Looking back: a short history of the discovery of enzymes and how they became powerful chemical tools. Chem Cat Chem 12:6082–6102. doi: 10.1002/cctc.202001107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Robinson PK. 2015. Enzymes: principles and biotechnological applications. Essays Biochem 59:1–41. doi: 10.1042/bse0590001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wiltschi B, Cernava T, Dennig A, Galindo Casas M, Geier M, Gruber S, Haberbauer M, Heidinger P, Herrero Acero E, Kratzer R, Luley-Goedl C, Müller CA, Pitzer J, Ribitsch D, Sauer M, Schmölzer K, Schnitzhofer W, Sensen CW, Soh J, Steiner K, Winkler CK, Winkler M, Wriessnegger T. 2020. Enzymes revolutionize the bioproduction of value-added compounds: From enzyme discovery to special applications. Biotechn Adv 40:107520. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2020.107520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wahart AJC, Staniland J, Miller GJ, Cosgrove SC. 2022. Oxidase enzymes as sustainable oxidation catalysts. R Soc open sci 9:17. doi: 10.1098/rsos.211572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dong J, Fernández‐Fueyo E, Hollmann F, Paul CE, Pesic M, Schmidt S, Wang Y, Younes S, Zhang W. 2018. Biocatalytic oxidation reactions: a chemist’s perspective. Angew Chem Int Ed 57:9238–9261. doi: 10.1002/anie.201800343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Levasseur A, Drula E, Lombard V, Coutinho PM, Henrissat B. 2013. Expansion of the enzymatic repertoire of the cazy database to integrate auxiliary redox enzymes. Biotechnol Biofuels 6:41. doi: 10.1186/1754-6834-6-41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. The CAZypedia Consortium . 2018. Ten years of CAZypedia: a living encyclopedia of carbohydrate-active enzymes. Glycobiology 28:3–8. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwx089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fong JK, Brumer H. 2022. Copper radical Oxidases: Galactose oxidase, Glyoxal oxidase, and beyond! Essays Biochem 67:EBC20220124. doi: 10.1042/EBC20220124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Koschorreck K, Alpdagtas S, Urlacher VB. 2022. Copper-radical oxidases: a diverse group of biocatalysts with distinct properties and a broad range of biotechnological applications. Eng Microb 2:100037. doi: 10.1016/j.engmic.2022.100037 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Whittaker MM, Ballou DP, Whittaker JW. 1998. Kinetic Isotope effects as probes of the mechanism of galactose oxidase. Biochemistry 37:8426–8436. doi: 10.1021/bi980328t [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Whittaker JW. 2003. Free radical catalysis by galactose oxidase. Chem Rev. 103:2347–2364. doi: 10.1021/cr020425z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Whittaker MM, Kersten PJ, Nakamura N, Sanders-Loehr J, Schweizer ES, Whittaker JW. 1996. Glyoxal oxidase from Phanerochaete chrysosporium is a new radical-copper oxidase. J Biol Chem 271:681–687. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.2.681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cooper JAD, Smith W, Bacila M, Medina H. 1959. Galactose oxidase from Polyporus circinatus, FR. J Biol Chem 234:445–448. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)70223-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ito N, Phillips SEV, Stevens C, Ogel ZB, McPherson MJ, Keen JN, Yadav KDS, Knowles PF. 1991. Novel thioether bond revealed by a 1.7Å crystal structure of galactose oxidase. Nature 350:87–90. doi: 10.1038/350087a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Parikka K, Leppänen A-S, Xu C, Pitkänen L, Eronen P, Österberg M, Brumer H, Willför S, Tenkanen M. 2012. Functional and anionic cellulose-interacting polymers by selective chemo-enzymatic carboxylation of galactose-containing polysaccharides. Biomacromolecules 13:2418–2428. doi: 10.1021/bm300679a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mikkonen KS, Parikka K, Suuronen JP, Ghafar A, Serimaa R, Tenkanen M. 2014. Enzymatic oxidation as a potential new route to produce polysaccharide aerogels. RSC Adv 4:11884. doi: 10.1039/c3ra47440b [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Derikvand F, Yin DT, Barrett R, Brumer H. 2016. Cellulose-based biosensors for esterase detection. Anal Chem. 88:2989–2993. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.5b04661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kanyong P, Krampa FD, Aniweh Y, Awandare GA. 2017. Enzyme-based amperometric galactose biosensors: a review. Microchim Acta 184:3663–3671. doi: 10.1007/s00604-017-2465-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wilchek M, Spiegel S, Spiegel Y. 1980. Fluorescent reagents for the labeling of glycoconjugates in solution and on cell surfaces. Biochem Biophys Res Com 92:1215–1222. doi: 10.1016/0006-291X(80)90416-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lampio A, Siissalo I, Gahmberg CG. 1988. Oxidation of glycolipids in liposomes by galactose oxidase. European J Biochem 178:87–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1988.tb14432.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Suzuki Y, Suzuki K. 1972. Specific radioactive labeling of terminal N-acetylgalactosamine of glycosphingolipids by the galactose oxidase-sodium borohydride method. J Lipid Res 13:687–690. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2275(20)39375-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Duke JA, Paschall AV, Glushka J, Lees A, Moremen KW, Avci FY. 2022. Harnessing galactose oxidase in the development of a chemoenzymatic platform for glycoconjugate vaccine design. J Biol Chem 298:101453. doi: 10.1016/j.jbc.2021.101453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Johnson HC, Zhang SG, Fryszkowska A, Ruccolo S, Robaire SA, Klapars A, Patel NR, Whittaker AM, Huffman MA, Strotman NA. 2021. Biocatalytic oxidation of alcohols using galactose oxidase and a manganese(Iii) activator for the synthesis of islatravir. Org Biomol Chem 19:1620–1625. doi: 10.1039/D0OB02395G [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ribeaucourt D, Bissaro B, Guallar V, Yemloul M, Haon M, Grisel S, Alphand V, Brumer H, Lambert F, Berrin JG, Lafond M. 2021. Comprehensive insights into the production of long chain aliphatic aldehydes using a copper-radical alcohol oxidase as biocatalyst. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng 9:4411–4421. doi: 10.1021/acssuschemeng.0c07406 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ribeaucourt David, Saker S, Navarro D, Bissaro B, Drula E, Correia LO, Haon M, Grisel S, Lapalu N, Henrissat B, O’Connell RJ, Lambert F, Lafond M, Berrin J-G. 2021. Identification of copper-containing oxidoreductases in the secretomes of three Colletotrichum species with a focus on copper radical oxidases for the biocatalytic production of fatty aldehydes. Appl Environ Microbiol 87:e0152621. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01526-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ribeaucourt D, Höfler GT, Yemloul M, Bissaro B, Lambert F, Berrin J-G, Lafond M, Paul CE. 2022. Tunable production of (R)- or (S)-citronellal from geraniol via a bienzymatic cascade using a copper radical alcohol oxidase and old yellow enzyme. ACS Catal 12:1111–1116. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.1c05334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Yin DL, Urresti S, Lafond M, Johnston EM, Derikvand F, Ciano L, Berrin JG, Henrissat B, Walton PH, Davies GJ, Brumer H. 2015. Structure-function characterization reveals new catalytic diversity in the galactose oxidase and glyoxal oxidase family. Nat Commun 6:13. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mathieu Y, Offen WA, Forget SM, Ciano L, Viborg AH, Blagova E, Henrissat B, Walton PH, Davies GJ, Brumer H. 2020. Discovery of a fungal copper radical oxidase with high catalytic efficiency toward 5-hydroxymethylfurfural and benzyl alcohols for bioprocessing. ACS Catal 10:3042–3058. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.9b04727 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bissaro B, Kodama S, Nishiuchi T, Díaz-Rovira AM, Hage H, Ribeaucourt D, Haon M, Grisel S, Simaan AJ, Beisson F, Forget SM, Brumer H, Rosso M-N, Guallar V, O’Connell R, Lafond M, Kubo Y, Berrin J-G. 2022. Tandem metalloenzymes gate plant cell entry by pathogenic fungi. Sci Adv 8:eade9982. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.ade9982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Leuthner B, Aichinger C, Oehmen E, Koopmann E, Müller O, Müller P, Kahmann R, Bölker M, Schreier PH. 2005. A H2O2-producing glyoxal oxidase is required for filamentous growth and pathogenicity in Ustilago maydis. Mol Genet Genomics 272:639–650. doi: 10.1007/s00438-004-1085-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Crutcher FK, Moran-Diez ME, Krieger IV, Kenerley CM. 2019. Effects on hyphal morphology and development by the putative copper radical oxidase Glx1 in Trichoderma virens suggest a novel role as a cell wall associated enzyme. Fun Gen Biol 131:103245. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2019.103245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Chaplin AK, Petrus MLC, Mangiameli G, Hough MA, Svistunenko DA, Nicholls P, Claessen D, Vijgenboom E, Worrall JAR. 2015. GlxA is a new structural member of the radical copper oxidase family and is required for glycan deposition at hyphal tips and morphogenesis of Streptomyces lividans. Biochem J. 469:433–444. doi: 10.1042/BJ20150190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Liman R, Facey PD, van Keulen G, Dyson PJ, Del Sol R. 2013. A laterally acquired galactose oxidase-like gene is required for aerial development during osmotic stress in Streptomyces coelicolor . PLoS One 8:e54112. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Whittaker MM, Whittaker JW. 2006. Streptomyces coelicolor oxidase (SCO2837p): a new free radical metalloenzyme secreted by Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). Archive Biochem Biop 452:108–118. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2006.06.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Cleveland ME, Mathieu Y, Ribeaucourt D, Haon M, Mulyk P, Hein JE, Lafond M, Berrin JG, Brumer H. 2021. A survey of substrate specificity among auxiliary activity family 5 copper radical oxidases. Cell Mol Life Sci. 78:8187–8208. doi: 10.1007/s00018-021-03981-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Cleveland M, Lafond M, Xia FR, Chung R, Mulyk P, Hein JE, Brumer H. 2021. Two Fusarium copper radical oxidases with high activity on aryl alcohols. Biotechnol Biofuels 14:19. doi: 10.1186/s13068-021-01984-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Andberg M, Mollerup F, Parikka K, Koutaniemi S, Boer H, Juvonen M, Master E, Tenkanen M, Kruus K. 2017. A novel Colletotrichum graminicola raffinose oxidase in the AA5 family. Appl Environ Microbiol 83:17. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01383-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Mollerup F, Aumala V, Parikka K, Mathieu Y, Brumer H, Tenkanen M, Master E. 2019. A family AA5_2 carbohydrate oxidase from Penicillium rubens displays functional overlap across the AA5 family. PLoS One 14:e0216546. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0216546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Mazurkewich S, Seveso A, Larsbrink J. 2023. A unique AA5 alcohol oxidase fused with a catalytically inactive CE3 domain from the bacterium Burkholderia pseudomallei. FEBS Lett 597:1779–1791. doi: 10.1002/1873-3468.14632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Aparecido Cordeiro F, Bertechini Faria C, Parra Barbosa‐Tessmann I. 2010. Identification of new galactose oxidase genes in Fusarium spp. J Basic Microbiol 50:527–537. doi: 10.1002/jobm.201000078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Faria CB, de Castro FF, Martim DB, Abe CAL, Prates KV, de Oliveira MAS, Barbosa-Tessmann IP. 2019. Production of galactose oxidase inside the Fusarium fujikuroi species complex and recombinant expression and characterization of the galactose oxidase GaoA protein from Fusarium subglutinans. Mol Biotechnol 61:633–649. doi: 10.1007/s12033-019-00190-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Rogers MS, Tyler EM, Akyumani N, Kurtis CR, Spooner RK, Deacon SE, Tamber S, Firbank SJ, Mahmoud K, Knowles PF, Phillips SEV, McPherson MJ, Dooley DM. 2007. The stacking tryptophan of galactose oxidase: a second-coordination sphere residue that has profound effects on tyrosyl radical behavior and enzyme catalysis. Biochemistry 46:4606–4618. doi: 10.1021/bi062139d [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Deacon SE, Mahmoud K, Spooner RK, Firbank SJ, Knowles PF, Phillips SEV, McPherson MJ. 2004. Enhanced fructose oxidase activity in a galactose oxidase variant. Chem Bio Chem 5:972–979. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200300810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Gur F, Yaprak G. 2011. Biomonitoring of metals in the vicinity of soma coal-fired power plant in western Anatolia, Turkey using the epiphytic lichen, Xanthoria Parietina. J Environ Sci Health A Tox Hazard Subst Environ Eng 46:1503–1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Paukner R, Staudigl P, Choosri W, Haltrich D, Leitner C. 2015. Expression, purification, and characterization of galactose oxidase of Fusarium sambucinum in E. coli. Protein Exp Pur 108:73–79. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2014.12.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Grigoriev IV, Nordberg H, Shabalov I, Aerts A, Cantor M, Goodstein D, Kuo A, Minovitsky S, Nikitin R, Ohm RA, Otillar R, Poliakov A, Ratnere I, Riley R, Smirnova T, Rokhsar D, Dubchak I. 2012. The genome portal of the department of energy joint genome institute. Nucleic Acids Res 40:D26–D32. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Wang R, Luo S, Clarke BB, Belanger FC. 2021. The epichloe festucae antifungal protein Efe-AfpA Is also a possible effector protein required for the interaction of the fungus with its host grass Festuca rubra subsp. rubra. Microorganisms 9:140. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms9010140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Gams W, Stielow B, Gräfenhan T, Schroers HJ. 2019. The ascomycete genus Niesslia and associated monocillium-like anamorphs. Mycol Progress 18:5–76. doi: 10.1007/s11557-018-1459-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Coleman JJ, Rounsley SD, Rodriguez-Carres M, Kuo A, Wasmann CC, Grimwood J, Schmutz J, Taga M, White GJ, Zhou S, et al. 2009. The genome of Nectria haematococca: contribution of supernumerary chromosomes to gene expansion. PLoS Genet 5:e1000618. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Miyakis S, Velegraki A, Delikou S, Parcharidou A, Papadakis V, Kitra V, Papadatos I, Polychronopoulou S. 2006. Invasive Acremonium strictum infection in a bone marrow transplant recipient. Ped Infect Dis J 25:273–275. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000202107.73095.ad [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Racedo J, Salazar SM, Castagnaro AP, Díaz Ricci JC. 2013. A strawberry disease caused by Acremonium strictum. Eur J PLANT Pathol 137:649–654. doi: 10.1007/s10658-013-0279-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Werpy T, Petersen G, Aden A, Bozell J, Holladay J, White J, Manheim A, Eliot D, Jones S, Lasure L. 2004. Top value added chemicals from Biomass, volume 1: Results of screening for potential candidates from sugars and synthesis gas. US Department of Energy, Oak Ridge, TN. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Bozell JJ, Petersen GR. 2010. Technology development for the production of biobased products from biorefinery carbohydrates-the US Department of Energy’s "Top 10" revisited. Green Chem 12:539. doi: 10.1039/b922014c [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Wu SK, Snajdrova R, Moore JC, Baldenius K, Bornscheuer UT. 2021. Biocatalysis: enzymatic synthesis for industrial applications. Angew Chem Int Ed 60:88–119. doi: 10.1002/anie.202006648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Sheldon RA, Brady D. 2022. Green chemistry, biocatalysis, and the chemical industry of the future. Chem Sus Chem 15. doi: 10.1002/cssc.202102628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Huffman MA, Fryszkowska A, Alvizo O, Borra-Garske M, Campos KR, Canada KA, Devine PN, Duan D, Forstater JH, Grosser ST, et al. 2019. Design of an in vitro biocatalytic cascade for the manufacture of islatravir. Science 366:1255–1259. doi: 10.1126/science.aay8484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Zhang SG, Ruccolo S, Fryszkowska A, Klapars A, Marshall N, Strotman NA. 2021. Electrochemical activation of galactose oxidase: mechanistic studies and synthetic applications. ACS Catal 11:7270–7280. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.1c01037 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Yeo WL, Tay DWP, Miyajima JMT, Supekar S, Teh TM, Xu J, Tan YL, See JY, Fan H, Maurer-Stroh S, Lim YH, Ang EL. 2023. Directed evolution and computational modeling of galactose oxidase toward bulky benzylic and alkyl secondary alcohols. ACS Catal 13:16088–16096. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.3c03427 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Ito N, Phillips SEV, Yadav KDS, Knowles PF. 1994. Crystal structure of a free radical enzyme, galactose oxidase. J Mol Biol 238:794–814. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Koncitikova R, Zuily L, Lemarié E, Ribeaucourt D, Saker S, Haon M, Brumer H, Guallar V, Berrin J-G, Lafond M. 2023. Rational engineering of AA5_2 copper radical oxidases to probe the molecular determinants governing their substrate selectivity. FEBS J 290:2658–2672. doi: 10.1111/febs.16713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Lippow SM, Moon TS, Basu S, Yoon S-H, Li X, Chapman BA, Robison K, Lipovšek D, Prather KLJ. 2010. Engineering enzyme specificity using computational design of a defined-sequence library. Chem Biol 17:1306–1315. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2010.10.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Sun LH, Bulter T, Alcalde M, Petrounia IP, Arnold FH. 2002. Modification of galactose oxidase to introduce glucose 6-oxidase activity. Chem Bio Chem 3:781. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Rannes JB, Ioannou A, Willies SC, Grogan G, Behrens C, Flitsch SL, Turner NJ. 2011. Glycoprotein labeling using engineered variants of galactose oxidase obtained by directed evolution. J Am Chem Soc. 133:8436–8439. doi: 10.1021/ja2018477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Abramson J, Adler J, Dunger J, Evans R, Green T, Pritzel A, Ronneberger O, Willmore L, Ballard AJ, Bambrick J, et al. 2024. Accurate structure prediction of biomolecular interactions with AlphaFold 3. Nature 630:493–500. doi: 10.1038/s41586-024-07487-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Spadiut O, Olsson L, Brumer H. 2010. A comparative summary of expression systems for the recombinant production of galactose oxidase. Microb Cell Fact 9:13. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-9-68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Carro J, Ferreira P, Rodríguez L, Prieto A, Serrano A, Balcells B, Ardá A, Jiménez‐Barbero J, Gutiérrez A, Ullrich R, Hofrichter M, Martínez AT. 2015. 5-hydroxymethylfurfural conversion by fungal aryl-alcohol oxidase and unspecific peroxygenase. FEBS J 282:3218–3229. doi: 10.1111/febs.13177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Tables S1 to S3; Figures S1 to S11.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated and analyzed during this study are included in this article and the associated supplementary information files. All nucleotide sequences, protein sequences, and protein structural information used in this work were extracted from public databases, i.e., GenBank (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/), The Protein Data Bank (www.rcsb.org/), The CAZy database (www.cazy.org/), and JGI Mycocosm (mycocosm.jgi.doe.gov/mycocosm/home).