Abstract

Background

Tumor Treating Fields (TTFields) are alternating electric fields that disrupt cancer cell processes. TTFields therapy is approved for recurrent glioblastoma (rGBM), and newly-diagnosed (nd) GBM (with concomitant temozolomide for ndGBM; US), and for grade IV glioma (EU). We present an updated global, post-marketing surveillance safety analysis of patients with CNS malignancies treated with TTFields therapy.

Methods

Safety data were collected from routine post-marketing activities for patients in North America, Europe, Israel, and Japan (October 2011–October 2022). Adverse events (AEs) were stratified by age, sex, and diagnosis.

Results

Overall, 25,898 patients were included (diagnoses: ndGBM [68%], rGBM [26%], anaplastic astrocytoma/oligodendroglioma [4%], other CNS malignancies [2%]). Median (range) age was 59 (3–103) years; 66% patients were male. Most (69%) patients were 18–65 years; 0.4% were < 18 years; 30% were > 65 years. All-cause and TTFields-related AEs occurred in 18,798 (73%) and 14,599 (56%) patients, respectively. Most common treatment-related AEs were beneath-array skin reactions (43%), electric sensation (tingling; 14%), and heat sensation (warmth; 12%). Treatment-related skin reactions were comparable in pediatric (39%), adult (42%), and elderly (45%) groups, and in males (41%) and females (46%); and similar across diagnostic subgroups (ndGBM, 46%; rGBM, 34%; anaplastic astrocytoma/oligodendroglioma, 42%; other, 40%). No TTFields-related systemic AEs were reported.

Conclusions

This long-term, real-world analysis of > 25,000 patients demonstrated good tolerability of TTFields in patients with CNS malignancies. Most therapy-related AEs were manageable localized, non-serious skin events. The TTFields therapy safety profile remained consistent across subgroups (age, sex, and diagnosis), indicative of its broad applicability.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11060-024-04682-7.

Keywords: Tumor Treating Fields, TTFields, Glioblastoma, Brain tumor, High grade gliomas, Safety

Introduction

Malignant gliomas, including glioblastoma (GBM [grade 4 isocitrate dehydrogenase wildtype (IDHwt)]), high grade astrocytoma IDH-mutated, and high grade oligodendroglioma IDH-mutated and 1p/19q-codeleted, classified based on histological and molecular characteristics in accordance with current World Health Organization (WHO) 2021 classification [1], are one of the most common primary glial central nervous system (CNS) cancers worldwide [2]. GBM has a high recurrence rate and very poor prognosis [3–5].

Treatment of newly diagnosed GBM (ndGBM) according to the Stupp protocol; i.e., maximum safe resection, followed by radiotherapy with concomitant and maintenance temozolomide (TMZ), has shown a median overall survival (OS) of 14–16 months, and a low 5-year OS rate of 5–10% [6–9].

Tumor Treating Fields (TTFields) are electric fields that exert physical forces to disrupt cellular processes critical for cancer cell viability and tumor progression [10, 11]. TTFields therapy is locoregional and non-invasive; the fields are generated by a wearable medical device and delivered to the tumor via arrays placed on the scalp. TTFields therapy targets cancer cells through multiple mechanisms, and predominantly exert their effects through mitotic and motility disruption, downregulation of the DNA damage response, and enhancement of antitumor immunity [12–18]. Additionally, TTFields have effects on upregulation of autophagy, enhancement of cell membrane permeability, and weakening of the tight junctions that constitute the blood-brain barrier [19–22].

TTFields therapy is approved for use as monotherapy in recurrent GBM (rGBM), and with maintenance TMZ in ndGBM, and Conformité Européene (CE)-marked for grade IV glioma in the European Union (EU), based on results from the pivotal EF-11 and EF-14 studies, respectively [9, 17, 22–24]. TTFields therapy with maintenance TMZ is a category 1 recommended treatment in the NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines) for ndGBM [22, 24, 25].

In the EF-11 study (rGBM patients), while the primary objective (demonstration of superiority of TTFields vs comparator) was not met, efficacy of TTFields monotherapy was comparable with physician’s best choice treatment, with TTFields therapy also showing improvements in the safety profile and quality of life (QoL) [23]. In the EF-14 study (ndGBM patients), OS and progression- free survival (PFS) were extended by 4.9 months and 2.7 months, respectively, with TTFields therapy concomitant with TMZ versus TMZ alone, representing a significant improvement for both endpoints [9]. The benefit appeared sustained, with 5-year OS rates of 13% versus 5% in the TTFields therapy with TMZ and TMZ alone groups, respectively [9]. Furthermore, TTFields therapy did not have a negative influence on health-related QoL, except for a higher incidence of skin toxicity [26, 27]. TTFields therapy was not associated with an increase in systemic toxicity in either the EF-11 or EF-14 pivotal studies [9, 23]. Recent meta-analysis of comparative TTFields therapy studies also suggests survival is significantly improved with the addition of TTFields to systemic standard of care (SOC) in patients with ndGBM in the real-world setting (HR: 0.63; 95% CI 0.53–0.75; p < 0.001). Among post-approval studies, the pooled median OS was 22.6 months (95% CI 17.6–41.2) for patients treated with TTFields therapy and 17.4 months (95% CI 14.4–21.6) for those receiving standard radiochemotherapy only [28]. These data provide evidence of consistency of efficacy in the real world.

Besides GBM, TTFields therapy with pemetrexed plus platinum-based chemotherapy has also been approved in the US and Europe for patients with pleural mesothelioma, under the Humanitarian Device Exemption pathway, based on results from the STELLAR study [29–31]. In this study, TTFields therapy demonstrated encouraging OS results, together with a tolerable safety profile and no increase in systemic toxicity [30].

TTFields therapy given concurrently with SOC therapies is also in clinical development as a potential approach for several other solid tumor indications.

Unsolicited post-marketing surveillance (PMS) data from 11,029 patients with CNS tumors treated with TTFields therapy between October 2011 and February 2019 were previously reported, which confirmed the favorable safety profile demonstrated in clinical studies and registry/real-world data without any new safety concerns [4, 9, 23, 32]. A sub-analysis of this dataset confirmed that TTFields therapy also has a favorable safety profile in a high-risk patient population with GBM and hydrocephalus harboring programmable or non-programmable ventriculoperitoneal (VP) shunts [33]. Furthermore, analysis of pediatric data from the PMS dataset revealed no new safety signals in children or adolescents with CNS tumors [34].

The present global PMS safety analysis reports an update on the previously published surveillance data [4], in a cohort of more than 25,000 patients with CNS tumors treated with TTFields therapy over an 11-year period.

Methods

This was a post-marketing surveillance analysis of patients with CNS tumors treated with TTFields therapy between October 2011 and October 2022 in North America, Europe, Israel, and Japan.

Unsolicited safety data were collected from routine post-marketing activities and interactions between the device manufacturer, patients, caregivers, and healthcare professionals (which included treating physicians, nurses, and other team members). Adverse events (AEs) were analyzed by the device manufacturer to determine seriousness and relatedness to TTFields therapy. AEs were classified using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA) version 25.1 and were graded as serious or non-serious. An AE was considered serious if it led to ≥1 of the following: (1) death; (2) life-threatening illness/injury; (3) permanent body structure/function impairment, including chronic disease; (4) in-patient hospitalization or prolongation of existing hospitalization; (5) medical/surgical intervention to prevent life-threatening illness, injury, or permanent body structure/function impairment; (6) fetal distress/death, congenital abnormality, or birth defect.

AEs were stratified by age (<18,18–65, and >65 years of age), sex, and diagnosis (ndGBM, rGBM, anaplastic astrocytoma and anaplastic oligodendroglioma, and other CNS tumors [including low-grade gliomas, high-grade gliomas, and metastases]). The historical diagnostic nomenclature was utilized as the majority of data collection occurred prior to the adoption of the WHO 2021 classification system.

Due to the retrospective nature of the analysis, AE occurrences were assessed via descriptive statistics.

Results

Baseline characteristics

A total of 25,898 patients were identified and included in this analysis. Post-marketing surveillance data for these patients were evaluated in the results. Baseline characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Most patients (n=18,665 [72%]) were from North America; 6,032 (23%) were from Europe or Israel, and 1,201 (5%) were from Japan. For patients with known age (n=25,718), median age (range) at start of treatment was 59 (3–103) years of age. The majority (17,817 [69%]) were 18–65 years of age; in total, there were 93 (0.4%) pediatric (<18 years of age) patients, and 7,808 (30%) elderly (>65 years of age) patients. Two-thirds (n=16,994 [66%]) of patients were male. Diagnoses were ndGBM (n=17,587 [68%]), rGBM (n=6,774 [26%]), anaplastic astrocytoma/oligodendroglioma (n=1,141 [4%]) and other (n=396 [2%]).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients treated with TTFields therapy

| Characteristic | Total | ndGBM | rGBM | AA/AO | Othera |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | (N = 25,898) | (n = 17,587) | (n = 6,774) | (n = 1,141) | (n = 396) |

| Age (years of age) | |||||

| < 18 | 93 (< 1) | 37 (< 1) | 31 (< 1) | 14 (1) | 11 (3) |

| 18–65 | 17,817 (69) | 11,390 (65) | 5,123 (76) | 1,000 (88) | 304 (77) |

| > 65 | 7,808 (30) | 5,989 (34) | 1,611 (24) | 127 (11) | 81 (20) |

| Unknown | 180 (1) | 171 (1) | 9 (< 1) | N/A | N/A |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 16,994 (66) | 11,427 (65) | 4,530 (67) | 780 (68) | 257 (65) |

| Female | 8,904 (34) | 6,160 (35) | 2,244 (33) | 361 (32) | 139 (35) |

| Region | |||||

| North America | 18,665 (72) | 12,042 (68) | 5,402 (80) | 869 (76) | 352 (89) |

| Europe and Israel | 6,032 (23) | 4,347 (25) | 1,369 (20) | 272 (24) | 44 (11) |

| Japan | 1201 (5) | 1198 (7) | 3 (< 1) | N/A | N/A |

AA, anaplastic astrocytoma; AO, anaplastic oligodendroglioma; NA, not applicable; ndGBM, newly diagnosed glioblastoma; rGBM, recurrent glioblastoma; TTFields, Tumor Treating Fields

aIncludes high-grade gliomas, low-grade gliomas, and brain metastases

Percentages may not total to 100%, due to rounding

Safety

Overall, 18,798 (73%) patients reported ≥1 (all-cause) AE, with the most common being skin reaction beneath the arrays (n=11,062 [43%] patients), electric sensation (i.e. under-array tingling; n=3,557 [14%]), and heat sensation (under-array warmth; n=3,083 [12%]) (Table 2). Electric sensation may be caused by displaced contact of the arrays on the scalp, potentially leading to arching across the gap between the arrays and scalp interface. Such electric sensations are not life-threatening electric shocks, but are commonly described as a tingling sensation beneath the arrays [4].

Table 2.

Most common AEs, whether related to TTFields therapy or not, in patients treated with TTFields therapy by age, sex, and diagnosis, with an incidence of ≥ 5% in the total cohort

|

MedDRA v25.1 System Organ Class / preferred term n (%) |

Total (N = 25,898) |

Age (years of age) | Sex | Diagnosis | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

< 18 (n=93) |

18–65 (n = 17,817) |

> 65 (n = 7,808) |

Female (n = 8,904) |

Male (n = 16,994) |

ndGBM (n = 17,587) |

rGBM (n = 6,774) |

AA/AO (n = 1,141) |

Othera (n = 396) |

||

| Patients with ≥ 1 AE | 18,798 (73) | 58 (62) | 12,795 (72) | 5,849 (75) | 6,710 (75) | 12,090 (71) | 13,201 (75) | 4,515 (67) | 796 (70) | 286 (72) |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | 1,467 (6) | 8 (9) | 1,003 (6) | 452 (6) | 571 (6) | 896 (5) | 1,068 (6) | 322 (5) | 54 (5) | 23 (6) |

| General disorders and administration site conditions | 9,486 (37) | 26 (28) | 6,650 (37) | 2,773 (36) | 3,523 (40) | 5,963 (35) | 6,689 (38) | 2,269 (33) | 403 (35) | 125 (32) |

| Electric sensationb | 3,557 (14) | 9 (10) | 2,734 (15) | 800 (10) | 1,402 (16) | 2,155 (13) | 2,576 (15) | 758 (11) | 167 (15) | 56 (14) |

| Fatigue/malaise | 1,809 (7) | 6 (6) | 1,204 (7) | 591 (8) | 637 (7) | 1,172 (7) | 1300 (7) | 420 (6) | 69 (6) | 20 (5) |

| General physical health deterioration | 1,273 (5) | 1 (1) | 873 (5) | 396 (5) | 426 (5) | 847 (5) | 876 (5) | 352 (5) | 41 (4) | 4 (1) |

| Heat sensationc | 3,083 (12) | 13 (14) | 2,157 (12) | 901 (12) | 1,156 (13) | 1,927 (11) | 2,152 (12) | 726 (11) | 152 (13) | 53 (13) |

| Pain | 1,784 (7) | 6 (6) | 1,214 (7) | 561 (7) | 809 (9) | 975 (6) | 1,300 (7) | 393 (6) | 70 (6) | 21 (5) |

| Infections and infestations | 1,984 (8) | 5 (5) | 1,238 (7) | 735 (9) | 739 (8) | 1245 (7) | 1,424 (8) | 451 (7) | 80 (7) | 29 (7) |

| Injury, poisoning, and procedural complications | 3,004 (12) | 3 (3) | 1,855 (10) | 1,135 (15) | 1,117 (13) | 1,887 (11) | 2,128 (12) | 718 (11) | 113 (10) | 45 (11) |

| Fall | 1,995 (8) | 3 (3) | 1,129 (6) | 861 (11) | 713 (8) | 1,282 (8) | 1,367 (8) | 520 (8) | 77 (7) | 31 (8) |

| Musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders | 1,753 (7) | 1 (1) | 1,062 (6) | 686 (9) | 672 (8) | 1,081 (6) | 1,308 (7) | 373 (6) | 59 (5) | 13 (3) |

| Muscular weakness | 1,247 (5) | 1 (1) | 708 (4) | 534 (7) | 457 (5) | 790 (5) | 910 (5) | 290 (4) | 38 (3) | 9 (2) |

| Nervous system disorders | 8,510 (33) | 28 (30) | 5,859 (33) | 2,585 (33) | 3,028 (34) | 5,482 (32) | 5,878 (33) | 2,171 (32) | 323 (28) | 138 (35) |

| Cognitive disorder | 1,201 (5) | - | 702 (4) | 492 (6) | 345 (4) | 856 (5) | 857 (5) | 290 (4) | 36 (3) | 18 (5) |

| Headache | 2,446 (9) | 12 (13) | 1,878 (11) | 549 (7) | 967 (11) | 1,479 (9) | 1,649 (9) | 646 (10) | 103 (9) | 48 (12) |

| Seizure | 3,034 (12) | 10 (11) | 2,164 (12) | 850 (11) | 1049 (12) | 1,985 (12) | 2,032 (12) | 845 (12) | 117 (10) | 40 (10) |

| Psychiatric disorders | 1,535 (6) | 3 (3) | 1,019 (6) | 508 (7) | 485 (5) | 1,050 (6) | 1,082 (6) | 373 (6) | 63 (6) | 17 (4) |

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders | 11,436 (44) | 36 (39) | 7,732 (43) | 3,614 (46) | 4,221 (47) | 7,215 (42) | 8,387 (48) | 2,388 (35) | 499 (44) | 162 (41) |

| Skin reaction | 11,062 (43) | 36 (39) | 7,444 (42) | 3,528 (45) | 4,123 (46) | 6,939 (41) | 8,143 (46) | 2,279 (34) | 483 (42) | 157 (40) |

AA, anaplastic astrocytoma; AE, adverse event; AO, anaplastic oligodendroglioma; MedDRA, Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities; ndGBM, newly diagnosed glioblastoma; rGBM, recurrent glioblastoma; TTFields, Tumor Treating Fields

aIncludes high-grade gliomas, low-grade gliomas, and brain metastases; bCommonly described as a tingling sensation below the arrays; cheat below the arrays; commonly described as a warm sensation

Percentages may not total to 100%, due to rounding

AE patterns were generally similar regardless of age, sex, and diagnosis, although the incidence of skin reactions was slightly higher in patients with ndGBM than those with rGBM (n=8,143 [46%] vs n=2,279 [34%] patients, respectively) (Table 2).

In total, 58 (62%) of pediatric patients reported ≥1 AE, regardless of relatedness of TTFields therapy; the most common events were skin reaction (36 [39%]) patients, heat sensation (13 [14%]), and headache (12 [13%]), which were generally in line with the overall population.

Overall, 5,849 (75%) of elderly patients reported ≥1 AE. AEs in elderly patients were also consistent with the overall population; most common events were skin reaction (n=3,528 [45%] patients), heat sensation (n=901 [12%]), and electric sensation (n=800 [10%]).

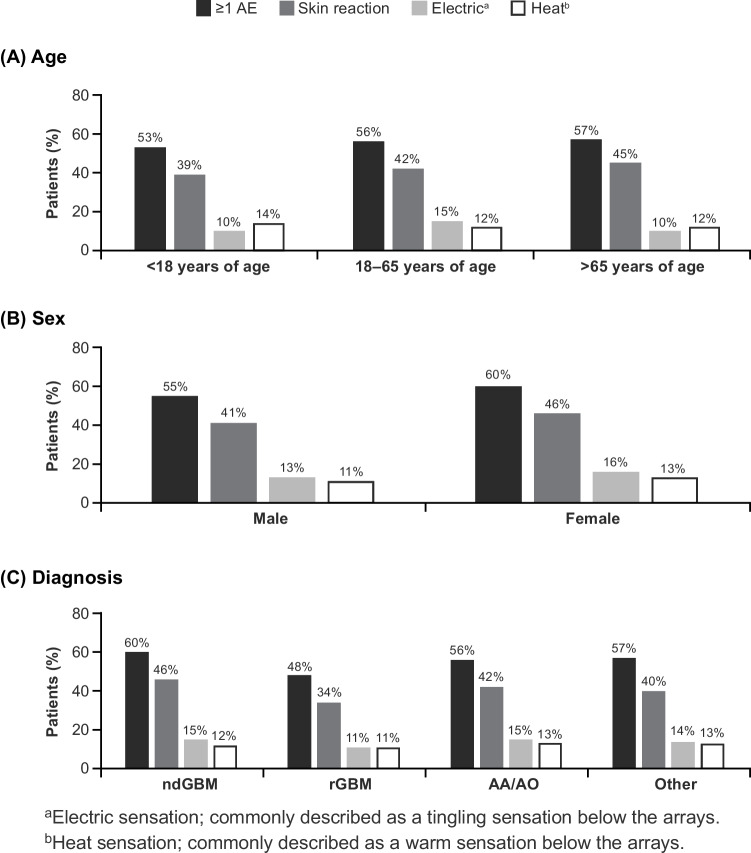

In total, 14,599 (56%) of patients reported AEs considered by the manufacturer to be possibly related to TTFields therapy. Device-related AEs occurring in ≥2% of the overall population are shown in Supplementary Table 1. The most frequently reported device-related AEs were skin reaction (n=11,029 [43%] patients), electric sensation (n=3,557 [14%]) and heat sensation (n=3,083 [12%]), occurring mainly underneath the arrays (Figure 1). Other device-related AEs included skin ulcer and wound complication (each 1% [Table 3]).

Fig. 1.

TTFields therapy-related AEs occurring in ≥ 10% of patients in any group, by age, sex, and diagnosis

Table 3.

Most common TTFields therapy-related AEs by age, sex, and diagnosis: full data set

| MedDRA v25.1 System Organ Class / preferred term n (%) |

Total (N = 25,898) |

Age (years) | Sex | Diagnosis | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 18 (n = 93) |

18–65 (n = 17,817) |

> 65 (n = 7,808) |

Female (n = 8,904) |

Male (n = 16,994) |

ndGBM (n = 17,587) |

rGBM (n = 6,774) |

AA/AO (n = 1,141) |

Othera (n = 396) |

||

| Ear and labyrinth disorders | 5 (< 1) | - | 3 (< 1) | 2 (< 1) | 2 (< 1) | 3 (< 1) | 4 (< 1) | - | 1 (< 1) | - |

| Auditory disorder | 4 (< 1) | - | 3 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) | 2 (< 1) | 2 (< 1) | 3 (< 1) | - | 1 (< 1) | - |

| Ear disorder | 1 (< 1) | - | - | 1 (< 1) | - | 1 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) | - | - | - |

| Eye disorders | 9 (< 1) | - | 7 (< 1) | 2 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) | 8 (< 1) | 8 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) | - | - |

| Eye disorder | 5 (< 1) | - | 4 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) | 4 (< 1) | 5 (< 1) | - | - | - |

| Visual impairment | 4 (< 1) | - | 3 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) | - | 4 (< 1) | 3 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) | - | - |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | 19 (< 1) | - | 16 (< 1) | 3 (< 1) | 6 (< 1) | 13 (< 1) | 16 (< 1) | 2 (< 1) | - | 1 (< 1) |

| Nausea/vomiting | 19 (< 1) | - | 16 (< 1) | 3 (< 1) | 6 (< 1) | 13 (< 1) | 16 (< 1) | 2 (< 1) | - | 1 (< 1) |

| General disorders and administration site conditions | 7,356 (28) | 22 (24) | 5,250 (29) | 2,056 (26) | 2,797 (31) | 4,559 (27) | 5,232 (30) | 1,675 (25) | 337 (30) | 112 (28) |

| Complication associated with device | 17 (< 1) | - | 8 (< 1) | 9 (< 1) | 4 (< 1) | 13 (< 1) | 14 (< 1) | 2 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) | - |

| Discomfort | 609 (2) | 2 (2) | 414 (2) | 192 (2) | 239 (3) | 370 (2) | 458 (3) | 113 (2) | 29 (3) | 9 (2) |

| Electric sensationb | 3,557 (14) | 9 (10) | 2,734 (15) | 800 (10) | 1,402 (16) | 2,155 (13) | 2,576 (15) | 758 (11) | 167 (15) | 56 (14) |

| Fatigue/malaise | 1,337 (5) | 5 (5) | 871 (5) | 455 (6) | 461 (5) | 876 (5) | 982 (6) | 287 (4) | 52 (5) | 16 (4) |

| Gait disturbance | 25 (< 1) | - | 18 (< 1) | 7 (< 1) | 13 (< 1) | 12 (< 1) | 19 (< 1) | 6 (< 1) | - | - |

| Heat sensationc | 3,083 (12) | 13 (14) | 2157 (12) | 901 (12) | 1,156 (13) | 1,927 (11) | 2,152 (12) | 726 (11) | 152 (13) | 53 (13) |

| Medical device site reaction | 1 (< 1) | - | 1 (< 1) | - | 1 (< 1) | - | 1 (< 1) | - | - | - |

| Oedema | 16 (< 1) | - | 12 (< 1) | 4 (< 1) | 9 (< 1) | 7 (< 1) | 16 (< 1) | - | - | - |

| Pain | 1,227 (5) | 3 (3) | 852 (5) | 371 (5) | 566 (6) | 661 (4) | 913 (5) | 251 (4) | 51 (4) | 12 (3) |

| Pyrexia | 1 (< 1) | - | 1 (< 1) | - | 1 (< 1) | - | - | 1 (< 1) | - | - |

| Swelling | 1 (< 1) | - | 1 (< 1) | - | 1 (< 1) | - | 1 (< 1) | - | - | - |

| Temperature intolerance | 24 (< 1) | - | 20 (< 1) | 4 (< 1) | 11 (< 1) | 13 (< 1) | 19 (< 1) | 3 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) |

| Immune system disorders | 84 (< 1) | - | 52 (< 1) | 32 (< 1) | 27 (< 1) | 57 (< 1) | 74 (< 1) | 7 (< 1) | 3 (< 1) | - |

| Hypersensitivity | 84 (< 1) | - | 52 (< 1) | 32 (< 1) | 27 (< 1) | 57 (< 1) | 74 (< 1) | 7 (< 1) | 3 (< 1) | - |

| Infections and infestations | 54 (< 1) | - | 40 (< 1) | 14 (< 1) | 17 (< 1) | 37 (< 1) | 44 (< 1) | 5 (< 1) | 3 (< 1) | 2 (1) |

| Abscess | 6 (< 1) | - | 5 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) | 2 (< 1) | 4 (< 1) | 5 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) | - | - |

| Brain abscess | 1 (< 1) | - | 1 (< 1) | - | 1 (< 1) | - | 1 (< 1) | - | - | - |

| Cellulitis | 2 (< 1) | - | 1 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) | - | - |

| Eye infection | 2 (< 1) | - | 1 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) | 2 (< 1) | - | - | - |

| Infection | 4 (< 1) | - | 2 (< 1) | 2 (< 1) | 2 (< 1) | 2 (< 1) | 4 (< 1) | - | - | - |

| Osteomyelitis | 1 (< 1) | - | 1 (< 1) | - | - | 1 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) | - | - | - |

| Skin infection | 38 (< 1) | - | 29 (< 1) | 9 (< 1) | 10 (< 1) | 28 (< 1) | 30 (< 1) | 3 (< 1) | 3 (< 1) | 2 (1) |

| Injury, poisoning and procedural complications | 496 (2) | - | 323 (2) | 167 (2) | 234 (3) | 262 (2) | 365 (2) | 109 (2) | 16 (1) | 6 (2) |

| Contusion | 36 (< 1) | - | 23 (< 1) | 13 (< 1) | 16 (< 1) | 20 (< 1) | 28 (< 1) | 8 (< 1) | - | - |

| Fall | 114 (< 1) | - | 72 (< 1) | 42 (1) | 44 (< 1) | 70 (< 1) | 69 (< 1) | 38 (1) | 6 (1) | 1 (< 1) |

| Fracture | 9 (< 1) | - | 6 (< 1) | 3 (< 1) | 7 (< 1) | 2 (< 1) | 9 (< 1) | - | - | - |

| Injury | 28 (< 1) | - | 14 (< 1) | 14 (< 1) | 14 (< 1) | 14 (< 1) | 24 (< 1) | 3 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) | - |

| Radiation injury | 4 (< 1) | - | 1 (< 1) | 3 (< 1) | 2 (< 1) | 2 (< 1) | 3 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) | (< 1) | - |

| Skin laceration | 79 (< 1) | - | 44 (< 1) | 35 (< 1) | 29 (< 1) | 50 (< 1) | 54 (< 1) | 23 (< 1) | 2 (< 1) | - |

| Thermal burn | 9 (< 1) | - | 6 (< 1) | 3 (< 1) | 6 (< 1) | 3 (< 1) | 7 (< 1) | 2 (< 1) | - | - |

| Wound complication | 257 (1) | - | 183 (1) | 68 (1) | 137 (2) | 120 (1) | 202 (1) | 43 (1) | 7 (1) | 5 (1) |

| Investigations | 405 (2) | - | 280 (2) | 124 (2) | 149 (2) | 256 (2) | 328 (2) | 59 (1) | 13 (1) | 5 (1) |

| Quality of life decreased | 405 (2) | - | 280 (2) | 124 (2) | 149 (2) | 256 (2) | 328 (2) | 59 (1) | 13 (1) | 5 (1) |

| Metabolism and nutrition disorders | 4 (< 1) | - | 2 (< 1) | 2 (< 1) | 2 (< 1) | 2 (< 1) | 4 (< 1) | - | - | - |

| Appetite disorder | 4 (< 1) | - | 2 (< 1) | 2 (< 1) | 2 (< 1) | 2 (< 1) | 4 (< 1) | - | - | - |

| Musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders | 172 (1) | - | 122 (1) | 50 (1) | 88 (1) | 84 (< 1) | 133 (1) | 31 (< 1) | 6 (1) | 2 (1) |

| Arthralgia | 64 (< 1) | - | 47 (< 1) | 17 (< 1) | 38 (< 1) | 26 (< 1) | 56 (< 1) | 7 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) | - |

| Arthritis | 1 (< 1) | - | 1 (< 1) | - | 1 (< 1) | - | 1 (< 1) | - | - | - |

| Arthropathy | 1 (< 1) | - | - | 1 (< 1) | - | 1 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) | - | - | - |

| Back disorder | 1 (< 1) | - | 1 (< 1) | - | 1 (< 1) | - | 1 (< 1) | - | - | - |

| Mobility decreased | 6 (< 1) | - | 2 (< 1) | 4 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) | 5 (< 1) | 5 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) | - | - |

| Muscle spasms | 60 (< 1) | - | 44 (< 1) | 16 (< 1) | 25 (< 1) | 35 (< 1) | 38 (< 1) | 16 (< 1) | 5 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) |

| Muscular weakness | 14 (< 1) | - | 8 (< 1) | 6 (< 1) | 5 (< 1) | 9 (< 1) | 8 (< 1) | 5 (< 1) | - | 1 (< 1) |

| Musculoskeletal stiffness | 28 (< 1) | - | 22 (< 1) | 6 (< 1) | 20 (< 1) | 8 (< 1) | 26 (< 1) | 2 (< 1) | - | - |

| Nervous system disorders | 2,251 (9) | 11 (12) | 1,708 (10) | 526 (7) | 891 (10) | 1,360 (8) | 1,544 (9) | 572 (8) | 94 (8) | 41 (10) |

| Balance disorder | 87 (< 1) | - | 55 (< 1) | 32 (< 1) | 43 (< 1) | 44 (< 1) | 67 (< 1) | 16 (< 1) | 3 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) |

| Cognitive disorder | 19 (< 1) | - | 14 (< 1) | 5 (< 1) | 4 (< 1) | 15 (< 1) | 16 (< 1) | 3 (< 1) | - | - |

| Coordination abnormal | 2 (< 1) | - | 2 (< 1) | - | 1 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) | - | - |

| Dizziness | 8 (< 1) | - | 5 (< 1) | 3 (< 1) | 3 (< 1) | 5 (< 1) | 7 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) | - | - |

| Dysesthesia | 13 (< 1) | - | 11 (< 1) | 2 (< 1) | 6 (< 1) | 7 (< 1) | 5 (< 1) | 7 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) | - |

| Headache | 2,144 (8) | 11 (12) | 1,639 (9) | 488 (6) | 845 (9) | 1,299 (8) | 1,463 (8) | 550 (8) | 91 (8) | 40 (10) |

| Hyperesthesia | 1 (< 1) | - | 1 (< 1) | - | - | 1 (< 1) | - | - | 1 (< 1) | - |

| Hypoesthesia | 1 (< 1) | - | - | 1 (< 1) | - | 1 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) | - | - | - |

| Lethargy | 2 (< 1) | - | 1 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) | 2 (< 1) | - | - | - |

| Memory impairment | 2 (< 1) | - | 1 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) | - | 2 (< 1) | 2 (< 1) | - | - | - |

| Paresthesia | 5 (< 1) | - | 5 (< 1) | - | 3 (< 1) | 2 (< 1) | 5 (< 1) | - | - | - |

| Speech disorder | 7 (< 1) | - | 5 (< 1) | 2 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) | 6 (< 1) | 7 (< 1) | - | - | - |

| Syncope | 1 (< 1) | - | 1 (< 1) | - | - | 1 (< 1) | - | 1 (< 1) | - | - |

| Tremor | 1 (< 1) | - | - | 1 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) | - | 1 (< 1) | - | - | - |

| Psychiatric disorders | 353 (1) | - | 239 (1) | 113 (1) | 113 (1) | 240 (1) | 269 (2) | 63 (1) | 16 (1) | 5 (1) |

| Agitation | 29 (< 1) | - | 19 (< 1) | 10 (< 1) | 5 (< 1) | 24 (< 1) | 17 (< 1) | 7 (< 1) | 4 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) |

| Anxiety | 49 (< 1) | - | 29 (< 1) | 20 (< 1) | 15 (< 1) | 34 (< 1) | 38 (< 1) | 8 (< 1) | 2 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) |

| Claustrophobia | 12 (< 1) | - | 8 (< 1) | 4 (< 1) | 5 (< 1) | 7 (< 1) | 9 (< 1) | 2 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) | - |

| Depression | 32 (< 1) | - | 23 (< 1) | 9 (< 1) | 15 (< 1) | 17 (< 1) | 21 (< 1) | 6 (< 1) | 4 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) |

| Insomnia | 237 (1) | - | 161 (1) | 75 (1) | 78 (1) | 159 (1) | 189 (1) | 40 (1) | 6 (1) | 2 (1) |

| Mental status changes | 2 (< 1) | - | 1 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) | - | 2 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) | - | - |

| Mood altered | 2 (< 1) | - | 2 (< 1) | - | 1 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) | 2 (< 1) | - | - | - |

| Sleep disorder | 2 (< 1) | - | 2 (< 1) | - | - | 2 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) | - | - |

| Stress | 15 (< 1) | - | 9 (< 1) | 6 (< 1) | 3 (< 1) | 12 (< 1) | 13 (< 1) | 2 (< 1) | - | - |

| Respiratory, thoracic, and mediastinal disorders | 4 (< 1) | - | 4 (< 1) | - | 1 (< 1) | 3 (< 1) | 4 (< 1) | - | - | - |

| Asphyxia | 4 (< 1) | - | 4 (< 1) | - | 1 (< 1) | 3 (< 1) | 4 (< 1) | - | - | - |

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders | 11,193 (43) | 36 (39) | 7,550 (42) | 3,554 (46) | 4,147 (47) | 7,046 (41) | 8,228 (47) | 2,314 (34) | 493 (43) | 158 (40) |

| Alopecia | 25 (< 1) | 1 (1) | 21 (< 1) | 3 (< 1) | 15 (< 1) | 10 (< 1) | 24 (< 1) | - | 1 (< 1) | - |

| Decubitus ulcer | 2 (< 1) | 1 (1) | - | 1 (< 1) | 2 (< 1) | - | 1 (< 1) | - | 1 (< 1) | - |

| Hyperhidrosis | 394 (2) | 1 (1) | 311 (2) | 81 (1) | 95 (1) | 299 (2) | 296 (2) | 74 (1) | 19 (2) | 5 (1) |

| Purpura | 1 (< 1) | - | 1 (< 1) | - | 1 (< 1) | - | - | - | 1 (< 1) | - |

| Rash | 11 (< 1) | - | 6 (< 1) | 5 (< 1) | 3 (< 1) | 8 (< 1) | 9 (< 1) | 2 (< 1) | - | - |

| Skin atrophy | 5 (< 1) | - | 4 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) | 3 (< 1) | 2 (< 1) | 4 (< 1) | - | 1 (< 1) | - |

| Skin discoloration | 5 (< 1) | - | 5 (< 1) | - | 1 (< 1) | 4 (< 1) | 4 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) | - | - |

| Skin erosion | 11 (< 1) | - | 9 (< 1) | 2 (< 1) | 7 (< 1) | 4 (< 1) | 8 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) | 2 (< 1) | - |

| Skin lesion | 2 (< 1) | - | - | 2 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) | - | - |

| Skin reaction | 11,029 (43) | 36 (39) | 7,419 (42) | 3,521 (45) | 4,110 (46) | 6,919 (41) | 8,117 (46) | 2,272 (34) | 483 (42) | 157 (40) |

| Skin ulcer | 157 (1) | 1 (1) | 101 (1) | 54 (1) | 74 (1) | 83 (< 1) | 98 (1) | 48 (1) | 9 (1) | 2 (1) |

| Vascular disorders | 2 (< 1) | - | 1 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) | 2 (< 1) | - | 2 (< 1) | - | - | - |

| Hematoma | 2 (< 1) | - | 1 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) | 2 (< 1) | - | 2 (< 1) | - | - | - |

AA, anaplastic astrocytoma; AE, adverse event; AO, anaplastic oligodendroglioma; MedDRA, Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities; ndGBM, newly diagnosed glioblastoma; rGBM, recurrent glioblastoma; TTFields, Tumor Treating Fields

aIncludes high-grade gliomas, low-grade gliomas, and brain metastases; bCommonly described as a tingling sensation below the arrays; cheat below the arrays; commonly described as a warm sensation

Percentages may not total to 100%, due to rounding

TTFields therapy-related AEs were also generally similar across patient subgroups, again with the exception that the incidence of treatment-related skin reactions was slightly higher in patients with ndGBM than in those with rGBM (n=8,177 [46%] vs n=2,272 [34%] patients, respectively) (Table 3).

In total, 49 (53%) of pediatric patients reported AEs considered to be possibly related to TTFields therapy. The most common treatment-related AEs in pediatric patients were: skin reaction (n=36 [39%]), heat sensation (n=13 [14%]), and headache (n=11 [12%]). There were no device-related AEs specific to children. There were no reports of device-related agitation, insomnia, or sleep disorder in pediatric patients.

In elderly patients, 4,432 (57%) reported AEs considered to be possibly related to treatment. The most common treatment-related AEs in elderly patients were skin reaction (n=3,521 [45%]), heat sensation (n=901 [12%]), and electric sensation (n=800 [10%]). Incidence of treatment-related fall and fracture in elderly patients was 1% and <1%, respectively.

Incidence of treatment-related skin reaction was 41% (n=6,919) and 46% (n=4,110) in males and females, respectively.

Patients with ≥1 all-cause serious AE are shown by subgroup in Supplementary Table 2). Serious AEs were reported in 5,773 (22%) of patients overall, with seizure (n=1,930 [7%]), brain edema (n=637 [2%]), fall (n=622 [2%]), general physical health deterioration (n=418 [2%]), and respiratory tract infection (n=406 [2%]) being the most common. Serious AEs considered potentially related to TTFields therapy were reported by in 124 (<1%) patients (Table 4); most common were wound complication (n=86 [<1%]), skin ulcer (n=20 [<1%]), skin laceration (n=7 [<1%] beneath the arrays), and fall (n=7 [<1%]).

Table 4.

Serious AEs potentially related to TTFields therapy in total patient cohort

| MedDRA v25.1 System Organ Class / preferred term n (%) | Total (N = 25,898) |

|---|---|

| Patients with ≥ 1 serious device-related event | 124 (< 1) |

| General disorders and administration site conditions | 1 (< 1) |

| Gait disturbance | 1 (< 1) |

| Infections and infestations | 6 (< 1) |

| Abscess | 3 (< 1) |

| Brain abscess | 1 (< 1) |

| Cellulitis | 1 (< 1) |

| Osteomyelitis | 1 (< 1) |

| Injury, poisoning and procedural complications | 101 (< 1) |

| Contusion | 1 (< 1) |

| Fall | 7 (< 1) |

| Fracture | 6 (< 1) |

| Injury | 1 (< 1) |

| Radiation injury | 1 (< 1) |

| Skin laceration | 7 (< 1) |

| Wound complicationa | 86 (< 1) |

| Nervous system disorders | 6 (< 1) |

| Cognitive disorder | 1 (< 1) |

| Headache | 6 (< 1) |

| Psychiatric disorders | 1 (< 1) |

| Anxiety | 1 (< 1) |

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders | 26 (< 1) |

| Skin erosion | 4 (< 1) |

| Skin reaction | 2 (< 1) |

| Skin ulcer | 20 (< 1) |

AE, adverse event; MedDRA, Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities; TTFields, Tumor Treating Fields

aIncludes wound dehiscence and wound infection

Only 405 (2%) of patients overall reported an AE of TTFields-related ‘QoL decreased’. In the context of these analyses, ‘QoL decreased’ refers to an unsolicited AE incidence of ‘QoL decreased’ per MedDRA version 25.1 preferred terms; QoL analysis via validated QoL assessment scale was not performed.

No new safety signals were identified in any patient subgroup, including vulnerable pediatric and elderly patients, and no systemic toxicities were reported.

Discussion

This retrospective, global, PMS analysis represents the largest dataset of TTFields therapy-treated patients to date, including more than 25,000 patients with CNS tumors over an 11-year period, and adds to the growing body of real-world safety data for TTFields therapy. These long-term data demonstrate the tolerability of TTFields therapy in patients with CNS malignancies.

The baseline characteristics of the dataset were reflective of the real-world demographics for this patient population [6]. In line with the literature, most patients in this dataset had a diagnosis of ndGBM. [35].

Rates and types of AEs were generally comparable regardless of age, sex, or diagnosis, demonstrating feasibility of TTFields therapy across demographic subgroups, including high-risk pediatric and elderly populations.

Goldman et al. previously reported pediatric data (n=81) from the same TTFields therapy PMS dataset from 2015–2021 [34]. Overall, AEs were predominantly mild-to-moderate localized skin events; incidence of skin reactions was similar in each age group (35% in children <13 years of age and 37% in adolescents 13–17 years of age) [34]. There were no unexpected toxicities identified in the pediatric patient population and, our analysis, representing an expansion of this dataset, continues to align with these findings. Although the TTFields therapy label does not currently include use in children with GBM (it is approved in adults [≥22 years of age in the US and ≥18 years of age in all other countries]), owing to their exclusion from the pivotal EF-11 and EF-14 studies, there is a growing body of real-world data and case reports indicating feasibility, in terms of safety, in pediatric patients [34, 36, 37].

Ram et al. recently conducted a subgroup analysis of the pivotal EF-14 study in elderly patients (≥65 years of age) with ndGBM. TTFields therapy concurrent with maintenance TMZ significantly improved PFS, and TTFields therapy-related skin AEs were low-grade and manageable, with no significant increases in systemic toxicity or negative effects on patient health-related QoL [38]. There were no major differences in AEs between patients >65 years of age and the overall population. Furthermore, TTFields therapy-related falls and fractures (which could perhaps occur due to the need to carry the device) were uncommon in elderly patients; this is important in a patient population who may be more susceptible to such events.

Real-world data to date also indicate no new safety findings or added toxicities of TTFields therapy in patients with electronic implantable devices including cardiac pacemakers/defibrillators and programmable/non-programmable VP shunts [33, 39, 40].

As expected from experiences with the clinical studies, and previous real-world data, the most common TTFields therapy-related AEs were mild-to-moderate localized skin AEs beneath the arrays [4, 9, 23, 32, 41–47]. The incidence of treatment-related skin reactions was slightly higher in patients with ndGBM than with rGBM (46% vs 34%, respectively), in agreement with previous reports [4, 34, 48], and which may be secondary to cumulative toxic effects of TMZ, and more likely skin sensitization caused by radiation therapy immediately preceding TTFields therapy in patients with ndGBM. The incidence of treatment-related skin reactions in patients with astrocytoma/oligodendroglioma was 42%, providing evidence of the device safety profile in this diagnostic subset for which fewer TTFields therapy data have been published previously, compared with GBM. In patients with ‘other’ tumor types (which included low-grade gliomas, high-grade gliomas, and metastases), the incidence of treatment-related skin reactions was 40%, further highlighting consistency of the device safety profile among diagnostic groups.

Skin AEs associated with TTFields therapy are, amongst other factors, a result of the mechanical, thermal, chemical, and moisture-related stresses related to prolonged contact between the skin and the device arrays and adhesive [49, 50]. Dermatologic irritations can include contact dermatitis, hyperhidrosis, xerosis or pruritus, and more rarely, skin erosions/ulcers and infections [49]. Such AEs can be mitigated, and scalp health maintained, using prophylaxis techniques, such as careful application, removal, and repositioning of the arrays, alongside regular skin examinations [49, 51–53]. Education of patients and caregivers about such preventative strategies, together with optimization of clinical practice techniques, may therefore reduce the risk of developing skin irritations [51, 54]. Prevention and management of skin AEs may maximize TTFields therapy usage time, which has been shown to be associated with improved survival outcomes in previous studies [28, 55].

When skin irritations are reported, these are typically mild-to-moderate and can usually be managed using topical agents, such as over-the-counter steroid creams, with referral to a dermatologist required only in the case of Grade 2 or 3 AEs [49].

Importantly, and in line with observations from the pivotal GBM clinical studies, no notable TTFields therapy-related systemic AEs were detected in this long-term surveillance analysis [9, 23]. Similarly, prospective clinical studies have consistently shown that TTFields therapy given concomitantly with systemic standard of care therapies does not lead to increases in systemic toxicity versus the concomitant therapy alone, in patients with GBM [56–58]. The lack of systemic side effects can be attributed to the locoregional nature of the therapy and is a key consideration in the GBM patient population who are already heavily burdened by disease and symptomology, as well as by considerable side effects of concurrent systemic treatments.

As this analysis spans 11 years, from 2011 to 2022, the database includes patients who have used the first generation NovoTTF-100A system, and those who have used the next generation NovoTTF-200A system. The second-generation system was CE-marked in the EU in 2015 and approved in the USA by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2016. The NovoTTF-200A is smaller and lighter than its predecessor, allowing for increased convenience and manageability. The transducer arrays themselves did not change largely as part of the system update; the only difference was a change in array color from white to tan. Patient experiences with the different generations of the device were not captured in this analysis; however, survey data in patients with GBM indicate that the improved handling and portability and overall design modifications of the second-generation NovoTTF-200A system help patients comply with daily treatment duration goals and meet recommended target compliance rates required for optimal therapeutic efficiency [59].

The large cohort size is a major strength of this analysis. There are, however, limitations inherent to the retrospective study design. Analyses were not statistically powered based on the design, and therefore, comparative statements should be considered as observational only. The retrospective nature of the study design has the potential to underestimate frequency of AEs. It is possible that the duration of treatment may impact occurrence and severity of skin AEs; however, these data were not captured. Additionally, data were not collected regarding use of concomitant therapies which may have had an effect on AE incidences.

An ongoing pivotal study assessing TTFields therapy in combination with radiotherapy and TMZ in ndGBM (TRIDENT; NCT04471844), and ongoing pivotal and pilot studies in other solid tumors, including pancreatic cancer and brain metastases from lung cancer, will provide further safety data of TTFields therapy across additional patient populations.

Conclusions

This global, PMS analysis of >25,000 patients represent the largest dataset of TTFields therapy use to date. These long-term, real-world data expand on previous real-world and clinical data, demonstrating a tolerable safety profile of TTFields therapy for patients with CNS tumors, with no new safety findings. Most AEs were localized and manageable non-serious skin events. There were no systemic adverse effects related to device use reported.

Overall, the safety profile of TTFields therapy remained consistent among patient subgroups and the total cohort, suggesting feasibility in multiple subpopulations. TTFields therapy was well tolerated across diagnostic groups, including patients with astrocytoma/oligodendroglioma and other CNS tumors. Importantly, the safety profile in pediatric and elderly patient subgroups was consistent with the overall population, with no new safety signals identified in these vulnerable populations. These data therefore provide further supportive evidence of the broad applicability of TTFields therapy.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Medical writing support under the direction of the authors was provided by Huda Abdullah, PhD, (formerly of Novocure Inc, USA), Melanie Lam, PharmD, (Novocure Inc, USA), Melanie More, BSc (of Prime, Knutsford, UK), and Imogen Francis, BSc, (formerly of Prime, Knutsford, UK). Writing and editorial support provided by Prime was funded by Novocure Inc. and conducted according to Good Publication Practice guidelines (Link).

Author contributions

All authors contributed to interpretation of the data. All authors contributed to the development of the manuscript, reviewed the drafts, and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This analysis was performed and funded by Novocure Inc. All costs related to publications, including medical writing support was funded by Novocure Inc.

Data Availability

Analyzed, non-confidential data will be made available 3 years after the date of publication upon reasonable request from qualified researchers.

Declarations

Competing interests

Maciej M Mrugala reports consultant fees from Alexion, Biocept, and Merck. Wenyin Shi reported grants/research support from Novocure Inc, Brainlab AG, and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals; and work as a consultant/independent contractor for Novocure Inc, Varian Medical Systems Inc, and Brainlab AG & Dohme Corp; role as an advisory/board member and work as a consultant/independent contractor with Vascular Biogenics Ltd (VBL) and ViruCure Therapeutics; and role on speaker bureaus and honorarium from Takeda and AstraZeneca. Fabio Iwomoto reports consultant fees from AbbVie, Alexion Pharmaceuticals, Gennao Bio, Guidepoint Global, Kiyatec, Massive Bio, Medtronic, Merck, MimiVax, Novocure, PPD, Regeneron, Tocagen, and Xcures; research funding from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celldex, FORMA Therapeutics, Merck, Northwest Biotherapeutics, Novocure, Sapience Therapeutics and Tocagen; travel and accommodation expenses from Oncoceutics. Rimas V Lukas reported grants/research support from NCI P50CA221747, BrainUp grant 2136, Bristol-Myers Squibb (drug support only for IIT); role as an advisory/ board member for Merck, Novocure, Cardinal Health, and AstraZeneca; work on a speaker bureau for Novocure Inc and Merck; honorarium from MedLink Neurology, EBSCO Publishing, and Elsevier. Joshua D Palmer reports consultant fees from Varian Medical Systems, ICOTEC and Novocure; research funding from NIH and Genentech. John H Suh reports consultant fees from Novocure and Philips; provides consultancy services for Neutron Therapeutics and EmpNia, and travel fees from Novocure Inc. Martin Glas reported work as a consultant/independent contractor with Roche Pharma, Novartis, AbbVie Inc, Novocure Inc, Servier, Seagen and Daiichi-Sankyo; honorarium from Novartis, UCB Inc, TEVA Pharmaceuticals, Bayer Corp, Novocure Inc, Medac, Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp, and Kyowa Kirin Group; and travel fees from Novocure Inc and Medac.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.World Health Organization (2022) WHO classification of CNS Tumours. https://radiopaedia.org/articles/who-classification-of-cns-tumours-1?lang=gb. Accessed 18 Nov 2022

- 2.GBD (2016) Brain and Other CNS Cancer Collaborators (2019) Global, regional, and national burden of brain and other CNS cancer, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol 18:376–393. 10.1016/s1474-4422(18)30468-x 10.1016/s1474-4422(18)30468-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Louis DN, Perry A, Reifenberger G, von Deimling A, Figarella-Branger D, Cavenee WK, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, Kleihues P, Ellison DW (2016) The 2016 World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: a summary. Acta Neuropathol 131:803–820. 10.1007/s00401-016-1545-1 10.1007/s00401-016-1545-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shi W, Blumenthal DT, Oberheim Bush NA, Kebir S, Lukas RV, Muragaki Y, Zhu JJ, Glas M (2020) Global post-marketing safety surveillance of Tumor Treating Fields (TTFields) in patients with high-grade glioma in clinical practice. J Neurooncol 148:489–500. 10.1007/s11060-020-03540-6 10.1007/s11060-020-03540-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Filley AC, Henriquez M, Dey M (2017) Recurrent glioma clinical trial, CheckMate-143: the game is not over yet. Oncotarget 8:91779–91794. 10.18632/oncotarget.21586 10.18632/oncotarget.21586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ostrom QT, Price M, Neff C, Cioffi G, Waite KA, Kruchko C, Barnholtz-Sloan JS (2022) CBTRUS Statistical Report: Primary Brain and Other Central Nervous System Tumors Diagnosed in the United States in 2015–2019. Neuro Oncol 24:v1–v95. 10.1093/neuonc/noac202 10.1093/neuonc/noac202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stupp R, Hegi ME, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, Taphoorn MJB, Janzer RC, Ludwin SK, Allgeier A, Fisher B, Belanger K, Hau P, Brandes AA, Gijtenbeek J, Marosi C, Vecht CJ, Mokhtari K, Wesseling P, Villa S, Eisenhauer E, Gorlia T, Weller M, Lacombe D, Cairncross JG, Mirimanoff R-O (2009) Effects of radiotherapy with concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide versus radiotherapy alone on survival in glioblastoma in a randomised phase III study: 5-year analysis of the EORTC-NCIC trial. Lancet Oncol 10:459–466. 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70025-7 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70025-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stupp R, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, Weller M, Fisher B, Taphoorn MJ, Belanger K, Brandes AA, Marosi C, Bogdahn U, Curschmann J, Janzer RC, Ludwin SK, Gorlia T, Allgeier A, Lacombe D, Cairncross JG, Eisenhauer E, Mirimanoff RO (2005) Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med 352:987–996. 10.1056/NEJMoa043330 10.1056/NEJMoa043330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stupp R, Taillibert S, Kanner A, Read W, Steinberg D, Lhermitte B, Toms S, Idbaih A, Ahluwalia MS, Fink K, Di Meco F, Lieberman F, Zhu JJ, Stragliotto G, Tran D, Brem S, Hottinger A, Kirson ED, Lavy-Shahaf G, Weinberg U, Kim CY, Paek SH, Nicholas G, Bruna J, Hirte H, Weller M, Palti Y, Hegi ME, Ram Z (2017) Effect of Tumor-Treating Fields plus maintenance temozolomide vs maintenance temozolomide alone on survival in patients with glioblastoma: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 318:2306–2316. 10.1001/jama.2017.18718 10.1001/jama.2017.18718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karanam NK, Story MD (2021) An overview of potential novel mechanisms of action underlying Tumor Treating Fields-induced cancer cell death and their clinical implications. Int J Radiat Biol 97:1044–1054. 10.1080/09553002.2020.1837984 10.1080/09553002.2020.1837984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mun EJ, Babiker HM, Weinberg U, Kirson ED, Von Hoff DD (2018) Tumor-Treating Fields: a fourth modality in cancer treatment. Clin Cancer Res 24:266–275. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-1117 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-1117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Giladi M, Schneiderman RS, Voloshin T, Porat Y, Munster M, Blat R, Sherbo S, Bomzon Z, Urman N, Itzhaki A, Cahal S, Shteingauz A, Chaudhry A, Kirson ED, Weinberg U, Palti Y (2015) Mitotic spindle disruption by alternating electric fields leads to improper chromosome segregation and mitotic catastrophe in cancer cells. Sci Rep 5:18046. 10.1038/srep18046 10.1038/srep18046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Voloshin T, Kaynan N, Davidi S, Porat Y, Shteingauz A, Schneiderman RS, Zeevi E, Munster M, Blat R, Tempel Brami C, Cahal S, Itzhaki A, Giladi M, Kirson ED, Weinberg U, Kinzel A, Palti Y (2020) Tumor-treating fields (TTFields) induce immunogenic cell death resulting in enhanced antitumor efficacy when combined with anti-PD-1 therapy. Cancer Immunol Immunother 69:1191–1204. 10.1007/s00262-020-02534-7 10.1007/s00262-020-02534-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Voloshin T, Schneiderman RS, Volodin A, Shamir RR, Kaynan N, Zeevi E, Koren L, Klein-Goldberg A, Paz R, Giladi M, Bomzon Z, Weinberg U, Palti Y (2020) Tumor Treating Fields (TTFields) hinder cancer cell motility through regulation of microtubule and actin dynamics. Cancers (Basel) 12:3016. 10.3390/cancers12103016 10.3390/cancers12103016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karanam NK, Ding L, Aroumougame A, Story MD (2020) Tumor Treating Fields cause replication stress and interfere with DNA replication fork maintenance: Implications for cancer therapy. Transl Res 217:33–46. 10.1016/j.trsl.2019.10.003 10.1016/j.trsl.2019.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karanam NK, Srinivasan K, Ding L, Sishc B, Saha D, Story MD (2017) Tumor-Treating Fields elicit a conditional vulnerability to ionizing radiation via the downregulation of BRCA1 signaling and reduced DNA double-strand break repair capacity in non-small cell lung cancer cell lines. Cell Death Dis 8:e2711. 10.1038/cddis.2017.136 10.1038/cddis.2017.136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gera N, Yang A, Holtzman TS, Lee SX, Wong ET, Swanson KD (2015) Tumor Treating Fields perturb the localization of septins and cause aberrant mitotic exit. PLoS ONE 10:e0125269. 10.1371/journal.pone.0125269 10.1371/journal.pone.0125269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moser JC, Salvador E, Deniz K, Swanson K, Tusynski J, Carlson KW, Karanam NK, Patel CB, Story M, Lou E, Hagemann C (2022) The mechanisms of action of Tumor Treating Fields. Cancer Res 3650–3658. 10.1158/0008-5472.Can-22-0887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Chang E, Patel CB, Pohling C, Young C, Song J, Flores TA, Zeng Y, Joubert L-M, Arami H, Natarajan A, Sinclair R, Gambhir SS (2018) Tumor Treating Fields increases membrane permeability in glioblastoma cells. Cell Death Discov 4:113. 10.1038/s41420-018-0130-x 10.1038/s41420-018-0130-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Salvador E, Kessler AF, Domröse D, Hörmann J, Schaeffer C, Giniunaite A, Burek M, Tempel-Brami C, Voloshin T, Volodin A, Zeidan A, Giladi M, Ernestus R-I, Löhr M, Förster CY, Hagemann C (2022) Tumor Treating Fields (TTFields) reversibly permeabilize the blood–brain barrier in vitro and in vivo. Biomolecules 12:1348. 10.3390/biom12101348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Shteingauz A, Porat Y, Voloshin T, Schneiderman RS, Munster M, Zeevi E, Kaynan N, Gotlib K, Giladi M, Kirson ED, Weinberg U, Kinzel A, Palti Y (2018) AMPK-dependent autophagy upregulation serves as a survival mechanism in response to Tumor Treating Fields (TTFields). Cell Death Dis 9:1074. 10.1038/s41419-018-1085-9 10.1038/s41419-018-1085-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Novocure (2019) Optune®: instructions for use. https://cms-admin.optunegio.com/sites/patient/files/2023-11/Optune_IFU.pdf. Accessed 1 Mar 2024

- 23.Stupp R, Wong ET, Kanner AA, Steinberg D, Engelhard H, Heidecke V, Kirson ED, Taillibert S, Liebermann F, Dbaly V, Ram Z, Villano JL, Rainov N, Weinberg U, Schiff D, Kunschner L, Raizer J, Honnorat J, Sloan A, Malkin M, Landolfi JC, Payer F, Mehdorn M, Weil RJ, Pannullo SC, Westphal M, Smrcka M, Chin L, Kostron H, Hofer S, Bruce J, Cosgrove R, Paleologous N, Palti Y, Gutin PH (2012) NovoTTF-100A versus physician’s choice chemotherapy in recurrent glioblastoma: a randomised phase III trial of a novel treatment modality. Eur J Cancer 48:2192–2202. 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.04.011 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.04.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Novocure (2020) Optune®: instructions for use (EU). https://www.optune.de/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Optune_User_Manual_ver2.0.pdf. Accessed 1 Mar 2024

- 25.National Comprehensive Cancer Network (2023) Central Nervous System Cancers Version 1.2023. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/cns.pdf. Accessed 18 Aug 2023

- 26.Taphoorn MJB, Dirven L, Kanner AA, Lavy-Shahaf G, Weinberg U, Taillibert S, Toms SA, Honnorat J, Chen TC, Sroubek J, David C, Idbaih A, Easaw JC, Kim CY, Bruna J, Hottinger AF, Kew Y, Roth P, Desai R, Villano JL, Kirson ED, Ram Z, Stupp R (2018) Influence of treatment with Tumor-Treating Fields on health-related quality of life of patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma: a secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol 4:495–504. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.5082 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.5082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stupp R, Ram Z (2018) Quality of life in patients with glioblastoma treated with tumor-treating fields—Reply. JAMA 319:1823–1823. 10.1001/jama.2018.1862 10.1001/jama.2018.1862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ballo MT, Conlon P, Lavy-Shahaf G, Kinzel A, Vymazal J, Rulseh AM (2023) Association of Tumor Treating Fields (TTFields) therapy with survival in newly diagnosed glioblastoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neurooncol 164:1–9. 10.1007/s11060-023-04348-w 10.1007/s11060-023-04348-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Novocure (2021) Optune LUATM: instructions for use for unrescetable malignant pleural mesothelioma. https://www.optunelua.com/pdfs/Optune-Lua-MPM-IFU.pdf?uh=18f20e383178129b5d6cd118075549592bae498860854e0293f947072990624c&administrationurl=https%3A%2F%2Foptunelua-admin.novocure.intouch-cit.com%2F. Accessed 21 July 2023

- 30.Ceresoli GL, Aerts JG, Dziadziuszko R, Ramlau R, Cedres S, van Meerbeeck JP, Mencoboni M, Planchard D, Chella A, Crino L, Krzakowski M, Russel J, Maconi A, Gianoncelli L, Grosso F (2019) Tumour Treating Fields in combination with pemetrexed and cisplatin or carboplatin as first-line treatment for unresectable malignant pleural mesothelioma (STELLAR): a multicentre, single-arm phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 20:1702–1709. 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30532-7 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30532-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Novocure (2017) Novocure™ Receives Humanitarian Use Device Designation for Treatment of Pleural Mesothelioma. https://www.novocure.com/novocure-receives-humanitarian-use-device-designation-for-treatment-of-pleural-mesothelioma/. Accessed 14 Feb 2022

- 32.Mrugala MM, Engelhard HH, Dinh Tran D, Kew Y, Cavaliere R, Villano JL, Annenelie Bota D, Rudnick J, Love Sumrall A, Zhu J-J, Butowski N (2014) Clinical practice experience with NovoTTF-100A™ system for glioblastoma: the Patient Registry Dataset (PRiDe). Semin Oncol 41(Suppl 6):S4–S13. 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2014.09.010 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2014.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oberheim-Bush NA, Shi W, McDermott MW, Grote A, Stindl J, Lustgarten L (2022) The safety profile of Tumor Treating Fields (TTFields) therapy in glioblastoma patients with ventriculoperitoneal shunts. J Neurooncol 158:453–461. 10.1007/s11060-022-04033-4 10.1007/s11060-022-04033-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goldman S, Margol A, Hwang EI, Tanaka K, Suchorska B, Crawford JR, Kesari S (2022) Safety of Tumor Treating Fields (TTFields) therapy in pediatric patients with malignant brain tumors: Post-marketing surveillance data. Front Oncol 12:958637. 10.3389/fonc.2022.958637 10.3389/fonc.2022.958637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miller KD, Ostrom QT, Kruchko C, Patil N, Tihan T, Cioffi G, Fuchs HE, Waite KA, Jemal A, Siegel RL, Barnholtz-Sloan JS (2021) Brain and other central nervous system tumor statistics, 2021. CA Cancer J Clin 71:381–406. 10.3322/caac.21693 10.3322/caac.21693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gött H, Kiez S, Dohmen H, Kolodziej M, Stein M (2022) Tumor treating fields therapy is feasible and safe in a 3-year-old patient with diffuse midline glioma H3K27M - a case report. Childs Nerv Syst 38:1791–1796. 10.1007/s00381-022-05465-z 10.1007/s00381-022-05465-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.O’Connell D, Shen V, Loudon W, Bota DA (2017) First report of tumor treating fields use in combination with bevacizumab in a pediatric patient: a case report. CNS Oncol 6:11–18. 10.2217/cns-2016-0018 10.2217/cns-2016-0018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ram Z, Kim CY, Hottinger AF, Idbaih A, Nicholas G, Zhu JJ (2021) Efficacy and safety of tumor treating fields (TTFields) in elderly patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma: subgroup analysis of the phase 3 EF-14 clinical trial. Front Oncol 11:671972. 10.3389/fonc.2021.671972 10.3389/fonc.2021.671972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ashby L, Hasselle M, Chowdhary S, Fathallah-Shaykh H, Zhu JJ (2015) ATCT-04: Retrospective analysis of Tumor Treating fields (TTFields) in adults with glioblastoma: safety profile of the Optune™ medical device in patients with implanted non-programmable shunts, programmable shunts, and pacemakers/defibrillators. Neuro Oncol 17(Suppl 5):v1. 10.1093/neuonc/nov206.04

- 40.Kew Y, Demopoulos A, Oberheim-Bush NA, Zhu JJ (2017) ACTR-65. Safety profile of Tumor Treating Fields in adult glioblastoma patients with implanted non-programmable shunts, programmable shunts, and pacemakers/defibrillators: 6-year updated retrospective analysis of Optune® therapy. Neuro Oncol 19(Suppl 6):vi14–vi15. 10.1093/neuonc/nox168.053

- 41.Ceresoli GL, Zucali PA, Mencoboni M, Botta M, Grossi F, Cortinovis D, Zilembo N, Ripa C, Tiseo M, Favaretto AG, Soto-Parra H, De Vincenzo F, Bruzzone A, Lorenzi E, Gianoncelli L, Ercoli B, Giordano L, Santoro A (2013) Phase II study of pemetrexed and carboplatin plus bevacizumab as first-line therapy in malignant pleural mesothelioma. Br J Cancer 109:552–558. 10.1038/bjc.2013.368 10.1038/bjc.2013.368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gkika E, Grosu A-L, Macarulla Mercade T, Cubillo Gracián A, Brunner TB, Schultheiß M, Pazgan-Simon M, Seufferlein T, Touchefeu Y (2022) Tumor Treating Fields concomitant with sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular cancer: results of the HEPANOVA phase II study. Cancers (Basel) 14:1568. 10.3390/cancers14061568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Pless M, Droege C, von Moos R, Salzberg M, Betticher D (2013) A phase I/II trial of Tumor Treating Fields (TTFields) therapy in combination with pemetrexed for advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 81:445–450. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2013.06.025 10.1016/j.lungcan.2013.06.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rivera F, Benavides M, Gallego J, Guillen-Ponce C, Lopez-Martin J, Küng M (2019) Tumor Treating Fields in combination with gemcitabine or gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel in pancreatic cancer: results of the PANOVA phase 2 study. Pancreatology 19:64–72. 10.1016/j.pan.2018 10.1016/j.pan.2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vergote I, von Moos R, Manso L, Van Nieuwenhuysen E, Concin N, Sessa C (2018) Tumor Treating Fields in combination with paclitaxel in recurrent ovarian carcinoma: results of the INNOVATE pilot study. Gynecol Oncol 150:471–477. 10.1016/j.ygyno.2018.07.018 10.1016/j.ygyno.2018.07.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nishikawa R, Yamasaki F, Arakawa Y, Muragaki Y, Narita Y, Tanaka S, Yamaguchi S, Mukasa A, Kanamori M (2023) Safety and efficacy of Tumour-Treating Fields (TTFields) therapy for newly diagnosed glioblastoma in Japanese patients using the Novo-TTF System: a prospective post-approval study. Jpn J Clin Oncol 53(5):371–311. 10.1093/jjco/hyad001 10.1093/jjco/hyad001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Leal T, Kotecha R, Ramlau R, Zhang L, Milanowski J, Cobo M, Roubec J, Petruzelka L, Havel L, Kalmadi S, Ward J, Andric Z, Berghmans T, Gerber DE, Kloecker G, Panikkar R, Aerts J, Delmonte A, Pless M, Greil R, Rolfo C, Akerley W, Eaton M, Iqbal M, Langer C (2023) Tumor Treating Fields therapy with standard systemic therapy versus standard systemic therapy alone in metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer following progression on or after platinum-based therapy (LUNAR): a randomised, open-label, pivotal phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol 24:1002–1017. 10.1016/S1470-2045(23)00344-3 10.1016/S1470-2045(23)00344-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Weinberg U, Perez S, Grewal J, Kinzel A (2018) INNV-04. Safety and adverse event profile of tumor treating fields in glioblastoma: a global post-market surveillance analysis. Neuro Oncol 20(Suppl 6):vi139. 10.1093/neuonc/noy148.579 10.1093/neuonc/noy148.579 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lacouture M, Anadkat MJ, Ballo MT, Iwamoto F, Jeyapalan SA, La Rocca RV, Schwartz M, Serventi JN, Glas M (2020) Prevention and management of dermatologic adverse events associated with Tumor Treating Fields in patients with glioblastoma. Front Oncol 10:1045. 10.3389/fonc.2020.01045 10.3389/fonc.2020.01045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lacouture M, Davis ME, Elzinga G, Butowski N, Tran D, Villano JL, DiMeglio L, Davies AM, Wong ET (2014) Characterization and management of dermatologic adverse events with the NovoTTF-100A System, a novel anti-mitotic electric field device for the treatment of recurrent glioblastoma. Semin Oncol 41(Suppl 4):S1–14. 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2014.03.011 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2014.03.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Anadkat MJ, Lacouture M, Friedman A, Horne ZD, Jung J, Kaffenberger B, Kalmadi S, Ovington L, Kotecha R, Abdullah HI, Grosso F (2023) Expert guidance on prophylaxis and treatment of dermatologic adverse events with Tumor Treating Fields (TTFields) therapy in the thoracic region. Front Oncol 12:975473. 10.3389/fonc.2022.975473 10.3389/fonc.2022.975473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gatson NTN, Ornelas S, Manikowski J, Toms SA, Leese E (2023) Tumor Treating Fields (TTFields) therapy skin safety and prevention strategy using a fractionated schema protocol (3-days on/1-day off), effect on skin adverse events. J Clin Oncol 41(16 suppl):e14030. 10.1200/JCO.2023.41.16_suppl.e14030 10.1200/JCO.2023.41.16_suppl.e14030 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chaudhry A, Naveh A, Hershkovich HS, Garcia-Carracedo D, Weinberg U, Ze Bomzon, Palti Y (2016) NIMG-26. Periodic transducer array shifting preserves both ttfields intensity in the gross tumor volume (GTV) and promotes scalp health during the course of glioblastoma therapy. Neuro Oncol 18(Suppl 6):vi129–vi130. 10.1093/neuonc/now212.538 10.1093/neuonc/now212.538 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lukas RV, Mrugala MM (2017) Pivotal therapeutic trials for infiltrating gliomas and how they affect clinical practice. Neurooncol Pract 4:209–219. 10.1093/nop/npw016 10.1093/nop/npw016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Toms SA, Kim CY, Nicholas G, Ram Z (2019) Increased compliance with tumor treating fields therapy is prognostic for improved survival in the treatment of glioblastoma: a subgroup analysis of the EF-14 phase III trial. J Neurooncol 141:467–473. 10.1007/s11060-018-03057-z 10.1007/s11060-018-03057-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Miller R, Song A, Ali A, Niazi M, Bar-Ad V, Martinez N, Glass J, Alnahhas I, Andrews D, Judy K, Evans J, Farrell C, Werner-Wasik M, Chervoneva I, Ly M, Palmer J, Liu H, Shi W (2022) Scalp-sparing radiation with concurrent temozolomide and Tumor Treating Fields (SPARE) for patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma. Front Oncol 12:896246. 10.3389/fonc.2022.896246 10.3389/fonc.2022.896246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bokstein F, Blumenthal D, Limon D, Harosh CB, Ram Z, Grossman R (2020) Concurrent Tumor Treating Fields (TTFields) and radiation therapy for newly diagnosed glioblastoma: A prospective safety and feasibility study. Front Oncol 10:411. 10.3389/fonc.2020.00411 10.3389/fonc.2020.00411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Song A, Ly M, Bar-Ad V, Werner-Wasik M, Glass J, Martinez N, Andrews D, Judy K, Evans J, Farrell C, Shi W (2019) ACTR-49. Initial experience with scalp preservation and radiation plus concurrent alternating electric Tumor-Treating Fields (SPARE) for glioblastoma patients. Neuro Oncol 21(Suppl 6):vi24. 10.1093/neuonc/noz175.091 10.1093/neuonc/noz175.091 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kinzel A, Ambrogi M, Varshaver M, Kirson ED (2019) Tumor Treating Fields for Glioblastoma Treatment: patient satisfaction and compliance with the second-generation Optune® system. Clin Med Insights Oncol 13:1–7. 10.1177/1179554918825449 10.1177/1179554918825449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Analyzed, non-confidential data will be made available 3 years after the date of publication upon reasonable request from qualified researchers.