Abstract

Global estimates indicate that over 600 million individuals worldwide consume the areca (betel) nut in some form. Nonetheless, its consumption is associated with a myriad of oral and systemic ailments, such as pre-cancerous oral lesions, oropharyngeal cancers, liver toxicity and hepatic carcinoma, cardiovascular distress, and addiction. Users commonly chew slivers of areca nut in a complex consumable preparation called betel quid (BQ). Consequently, the user is exposed to a wide array of chemicals with diverse pharmacokinetic behavior in the body. However, a comprehensive understanding of the metabolic pathways significant to BQ chemicals is lacking. Henceforth, we performed a literature search to identify prominent BQ constituents and examine each chemical’s interplay with drug disposition proteins. In total, we uncovered over 20 major chemicals (e.g., arecoline, nicotine, menthol, quercetin, tannic acid) present in the BQ mixture that were substrates, inhibitors, and/or inducers of various phase I (e.g., CYP, FMO, hydrolases) and phase II (e.g., GST, UGT, SULT) drug metabolizing enzymes, along with several transporters (e.g., P-gp, BCRP, MRP). Altogether, over 80 potential interactivities were found. Utilizing this new information, we generated theoretical predictions of drug interactions precipitated by BQ consumption. Data suggests that BQ consumers are at risk for drug interactions (and possible adverse effects) when co-ingesting other substances (multiple therapeutic classes) with overlapping elimination mechanisms. Until now, prediction about interactions is not widely known among BQ consumers and their clinicians. Further research is necessary based on our speculations to elucidate the biological ramifications of specific BQ-induced interactions and to take measures that improve the health of BQ consumers.

Keywords: Areca nut, betel nut, betel quid, drug interaction, enzyme, metabolism, arecoline, drug transport

1. INTRODUCTION

Areca (betel) nut is a psychoactive substance and established carcinogen widely consumed in many parts of the world, including Southeast and East Asia and Tropical Pacific nations. Worldwide, there are an estimated 600 million users of it [1–3]. Growing evidence is showing that consumption of the areca nut (AN) is sustained after migration into industrialized nations [4], further disseminating the areca nut (AN) health burden globally. Mastication of the nut releases psychoactive alkaloids (e.g., arecoline) that increase mental alertness and produce euphoric-like effects, often leading to addiction [5]. Other detrimental side effects from consuming AN include liver toxicity, hepatic cancer, metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular illness, tongue staining, red/black staining of teeth, periodontal disease, pre-cancerous lesions of the mouth (e.g., leukoplakia, oral submucosal fibrosis), and increased incidence of esophageal, pharyngeal, and oral cancers [2, 6]. A commonly consumed concoction containing the AN is called betel quid (BQ), which derives its name from the leaf (Piper betel pepper plant) that is used to wrap the nut and other ingredients into a chewable preparation [2, 6]. BQ, sometimes referred to as “pan masala”, generally consists of betel leaf, sliced areca nut, lime, and sweeteners/flavorings according to local customs and traditions. When tobacco is added, the preparation is then referred to as “gutkha” in some cultures. A typical consumer chews many quids throughout the day [7, 8], often swallowing the betel juices that lead to systemic exposure to a wide array of chemicals with various pharmacokinetic properties in the body. Of importance to drug metabolism, these chemicals may be substrates for drug-metabolizing enzymes (DME) and drug transporters and sometimes act as an inducer and/or inhibitor of these disposition proteins. This is especially significant if the BQ user concomitantly takes prescription, over-the-counter (OTC), or other therapeutic agents dealt with in the body by overlapping elimination mechanisms. However, there is a large paucity of research on how BQ consumption may influence the metabolism of other substances. It remains unknown if metabolism-based interactions contribute to the massive health burden associated with BQ consumption in society. Henceforth, we initially conducted an extensive literature search to identify major chemical constituents in BQ, then determined their metabolic interplay with drug disposition proteins (Phase I/II enzymes and drug transporters), and subsequently generated theoretical predictions of drug interactions in BQ consumers. Finally, we highlighted future areas of clinical research to build upon our initial predictions.

2. METHODS

Google Scholar and PubMed databases were used to perform literature searches and identify specific chemicals within components of the BQ, including the areca nut, betel leaf, flavorings, spices, and tobacco leaf. In order to gather a comprehensive list of data, no restrictions on the year of publication were imposed during our literature search, and data were acquired from both humans and non-human animals (e.g., mice, rats). Specific key words used in the searches included “areca”, “areca nut”, “betel”, “betel nut”, “betel leaf”, “betel quid”, “tobacco”, and “tobacco leaf” in combination with “chemicals”, “constituents”, “ingredients,” and “content”. Findings were compiled into an Excel spreadsheet to sort ingredients per BQ component. Then, names of identified BQ constituents were incorporated into a subsequent literature search to categorize each chemical’s interplay with DME and transporters. Keywords used in this search included the chemical name combined with “metabolism”, “drug transporter”, “drug-metabolizing enzyme”, “pharmacokinetics”, “inhibition”, “induction”, and “substrate”, Chemicals were designated as a substrate, inhibitor, and/or inducer of drug transporters and Phase I and Phase II DMEs. The findings were subsequently analyzed by cross-referencing published information to make preliminary predictions about potential drug interactions perpetrated by BQ constituents.

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

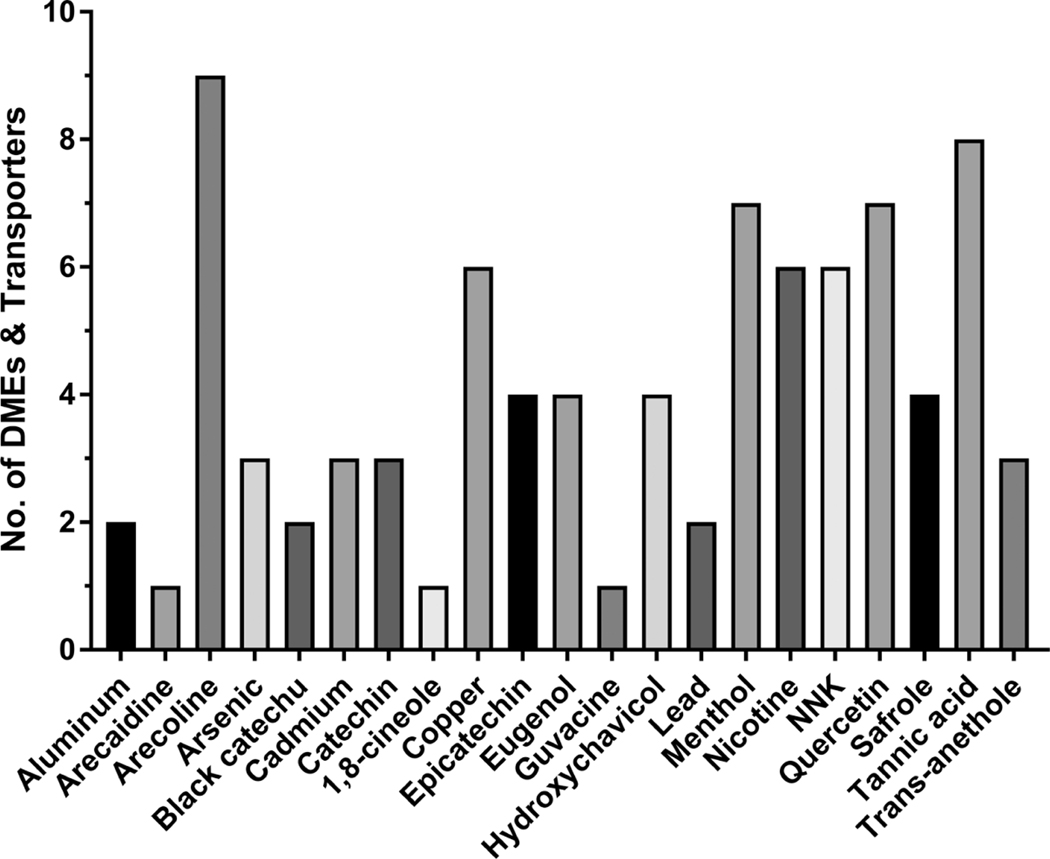

A synopsis of our findings is included in (Figs. 1-3) and Table 1. A total of 21 major chemicals were found in BQ components, specifically 8 in the areca nut, 4 in the betel leaf, 4 in miscellaneous additives/spices, and 5 in tobacco (Fig. 1). These chemicals include aluminum, arecoline, arecaidine, catechin, copper, epicatechin, guvacine, and tannic acid in the areca nut, eugenol, hydroxychavicol, quercetin, and safrole in the betel leaf, black catechu, 1,8-cineole, menthol and trans-anethole in miscellaneous additives/spices, and arsenic, cadmium, lead, nicotine, and 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone (NNK) in tobacco (Fig. 1). These constituents were found to interplay with over 20 different DMEs, along with several drug transporters, in mammalian species (Fig. 2). Collectively, this includes 14 Phase I enzymes: carbonyl reductase, esterase, flavin-containing monooxygenase (FMO), NAD(P)H Quinone Dehydrogenase 1 (NQO1), 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (11β-HSD), xanthine oxidase (XO), various cytochrome P450 (CYP) isoenzymes, and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH)–cytochrome P450 reductase (CPR). Identified phase II enzymes, a total of 4, include glutathione S-transferase (GST), sulfotransferase (SULT), UDP-glucuronosyltransferase (UGT), and methylases. Five drug transporters were also identified, inclusive of breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP), multidrug resistance-associated proteins (MRP), organic anion transporting polypeptide (OATP), P-glycoprotein (P-gp), and the human proton-coupled amino acid transporter-1 (hPAT1). BQ chemicals with 4 or more different probable interactions with distinct DMEs and/or transporters include arecoline, copper, epicatechin, eugenol, hydroxychavicol, menthol, nicotine, NNK, quercetin, safrole, and tannic acid (Fig. 1). DMEs with 4 or more identified potential interactions with distinct BQ substances include CYP1A, CYP2A, CYP2C, CYP2D, CYP2E, CYP3A, GST, Methylase, SULT, and UGT (Fig. 2). A total of 87 potential interactions with BQ constituents were uncovered, of which 34 were found in AN constituents, 19 in betel leaf chemicals, 20 in tobacco ingredients, and 13 in miscellaneous spices and additives (Fig. 3). Furthermore, Table 1 highlights the various interplay between specific BQ constituents and specific DMEs and transporters. A more detailed discussion about the individual constituents and their relevant interactivity with these enzymes and transporters is also presented.

Fig. (1).

Primary BQ constituents that interplay with DMEs (both Phase I and Phase II) and drug transporters.

Fig. (3).

The number of speculative DME and transporter interactivities (e.g., substrate, inhibition, induction) per each BQ component.

Table 1.

DME and transporter interactivity with BQ constituents.

|

Note: The black box means there is NO interactivity between the enzyme/transporter and betel quid constituent.

Fig. (2).

Specific DMEs and drug transporters manifesting interplay with major constituents found in the BQ mixture.

3.1. Areca Nut

The AN, a fruit of the areca palm tree (Areca catechu), contains numerous substances that are significant to drug metabolism. Among the major chemical constituents include the areca alkaloids (arecoline, arecaidine, guvacoline, and guvacine), polyphenols (tannins and catechins), and other elements (aluminum and copper).

3.1.1. Areca Alkaloids

The percent composition of areca alkaloids in AN samples varies between studies, with one study reporting that arecoline, arecaidine, guvacoline, guvacine constituted approximately 0.30–0.63%, 0.31–0.66%, 0.03–0.06%, and 0.19–0.72%, respectively [9]. Another study reported that arecoline is present in the range of 0.1% to 0.9% in various processed nuts [10], and another study found that arecoline was the most abundant alkaloid in AN samples [11]. Arecaidine content varies over 12-fold among AN products and apparently is greater in mature nut extracts versus younger nuts [12, 13]. Although the work of Huang and McLeish found that guvacoline is the least abundant alkaloid in the AN [9], other published works suggest that guvacoline amounts are similar to other areca alkaloids [12, 13]. Although generally not considered the major areca alkaloid, guvacine is the most abundant alkaloid in the mature betel nut (3x more than arecoline), composing ~50%−80% of all alkaloid content in dry AN and BQ preparations [13].

Our literature review found that arecoline has a significant interaction with both phase I and phase II DME. Its effects on glutathione S-transferase (GST) enzymes are unequivocal. Several studies indicated that arecoline inhibited GST activity in mice and human tissue [14–16], whereas another study found that arecoline induced hepatic GST activity in mice [17]. For instance, in human buccal mucosal fibroblasts, arecoline significantly decreased GST activity in a dose-dependent manner by up to 46% following exposure to 400 μg/mL during a 24 h incubation period [14]. Arecoline is a substrate for human flavin monooxygenases-1 (FMO1) and FMO3 [18], mouse carboxylesterase (Ces) [19], and pig liver esterase [19]. Arecoline, administered at 4 mg/kg/d for 7 days to rats, induced various isoenzymes of the cytochrome P450 (CYP) family in hepatic tissue, specifically CYP1A, CYP2B, CYP2C, CYPD2D, CYP2E, and CYP3A [20].

Arecaidine is a de-esterified derivative of arecoline and is a substrate for the human proton-coupled amino acid transporter 1 (hPAT-1) [21], also called solute carrier family 36 Member 1 (SLC36A1). Guvacoline (alternatively called norarecoline) is an N-demethylated congener of arecoline. Although our literature search did not reveal any information about guvacoline’s interplay with drug disposition proteins, it might be a substrate for esterases (hydrolases) since the molecule contains a labile methyl ester group similar to arecoline. Like arecaidine, guvacine is a substrate for hPAT-1 [21].

3.1.2. Polyphenols

Among the major polyphenols found in the AN are tannins, ranging from 1.13 −3.39% composition in various samples of AN [22]. Tannins collectively include a diverse array of substances that have an extensive impact on xenobiotic metabolism and biology. Tannins can bind to and precipitate proteins, amino acids, and alkaloids [23] and generally decrease enzymatic activity due to complexation with the enzyme; however, they may also induce enzyme activity. Tannic acid, a type of hydrolysable tannin, significantly modulates phase I and II DME activities [24]. Specifically, livers obtained from mice treated with 20, 40, 60, and 80 mg/kg of tannic acid had significant reductions in NQO1 activity by 30%, 61%, 90%, and 89%, respectively [24]. A similar dose-dependent trend was observed in kidney tissues, albeit to a lesser degree of inhibition [24]. Tannic acid had a dramatic effect on NQO1 functionality in mice treated with 60 mg/kg, abolishing almost 100% of activity in liver and kidney tissue [24]. Similar effects were observed in rabbits, in which tannic acid inhibited liver and kidney NQO1 activity with an IC50 of 7.3 μM and 8.6 μM, respectively [25].

Krajka-Kuzniak and Baer-Dubowska also reported that tannic acid decreased hepatic CYP2E activity by up to 50% at 80 mg/kg [24]. In human liver microsomes, tannic acid inhibited CYP2E1 activity with an IC50 of 15 μM [26], whereas an IC50 of 30 μM was found in mouse liver microsomes [27]. Furthermore, tannic acid blocked CPR activity in human liver microsomes (IC50 of 17.4 μM) [26] and in hepatocytes (IC50 of 55 μM) [28]. Moreover, tannic acid inhibited human CYP1A isoenzymes, with a preference for CYP1A2 (IC50 of 23 μM and 2.3 μM for CYP1A1 and CYP1A2, respectively [26]).

Tannic acid also exerts an impact on the expression and functionality of phase II enzymes and drug transporters. For example, its effects on GST activity were found to be variable, as renal GST activity was induced by up to 34% in mice treated with the highest dose (80 mg/kg), but hepatic GST activity was reduced by 25% at the same dose [24]. Tannic acid inhibited GST activity in human liver cytosol with a Ki of 0.4 μM [25] and inhibited UGT activity in rat liver with an IC50 of 50 μM [29]. Tannic acid can also modulate drug transport (efflux), as it decreases protein expression and functionality of P-glycoprotein (P-gp), multidrug resistance-associated protein 1 (MRP1), and multidrug resistance-associated protein 2 (MRP-2) in human cholangiocytes at concentrations ranging from 5 to 25 μM [30].

Catechins are another type of polyphenol commonly found in the AN, with several studies reporting catechin is the most abundant compound in AN with up to 2.79 mg/g [11, 31]. Catechins, in general, are metabolized extensively by phase II synthetic processes and can modulate the activity of DMEs [32]. For example, catechin is primarily metabolized in the small intestine of rats, where it enters intestinal epithelial cells and undergoes glucuronidation, sulfonation, and methylation [33]. Epicatechin, another common polyphenol found in the AN, is mainly metabolized by glucuronidation and methylation in rats [34], with some sulfonation [35]. It also deters some phase II enzyme activity. For instance, epicatechin inhibited the sulfation of baicalein in human colon cancer cells with an IC50 of 18 μM [36]. Additionally, epicatechin exhibited a dose-dependent inhibition of baicalein sulfonation (IC50 of 25 μM) and glucuronidation (IC50 of 32 μM) in rat intestines [36]. Epicatechin (250 μM) also significantly impeded the glucuronidation of α-naphthol in isolated rat small intestines [37]. Moreover, epicatechin (50 μM) modestly inhibited human CYPs with the most profound effect on CYP2E1 [38].

Quercetin is reportedly the second most abundant polyphenol in AN at 0.14 mg/g dry weight [31], and is also found in the betel leaf. Quercetin is conjugated with UDP in human liver and intestine, preferentially by UGT1A1, UGT1A8, and UGT1A9 [39]. Low exposure of quercetin (10 μM) to human Caco-2 cells over 5 weeks resulted in a significant 100% increase in UGT activity compared to the control [40]. Quercetin inhibited SULT1A1 activity in human and fetal liver tissue, with Ki of 4.7 nM and 4.8 nM, respectively [41]. In addition, quercetin inhibits several drug transporters with varying affinities [42], with IC50 of 0.13 μM, 10 μM, 1.55 μM, 3.22 μM, and 0.34 μM for breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP), organic anion transporting polypeptides 1A2 (OATP1A2), OATP1B1, OATP1B3, and OATP2B1, respectively [42]. In the same study, quercetin’s glucuronide and sulfate conjugates inhibited these transporters, with IC50 values lower than quercetin [42]. The mRNA levels and protein expression of numerous DME and transporters were lowered in a dose-dependent manner in rats treated with 25–100 mg/kg of quercetin [43]. Quercetin strongly inhibited human recombinant CYP2D6 (IC50 = 0.65 μM) and moderately inhibited human recombinant CYP2C19 and CYP3A4 with IC50 values of 12 μM and 5.5 μM, respectively [44]. In contrast, another study demonstrated that quercetin has minimal impact on CYP2D6, CYP2C19, and CYP3A4 activity [42]. Significantly, quercetin and its sulfate and methyl conjugate potently inhibited XO-mediated metabolism of 6-mercaptopurine, with IC50 of 1.4 μM, 0.5 μM, and 0.2 μM, respectively [45]. Potent inhibition of XO by quercetin (IC50 of 0.44 −1.4 μM) has been shown in other studies [46, 47].

Finally, aqueous and methanolic extracts of the Areca catechu plant (areca palm tree), both tested at 100 μg/mL, inhibited human CYP3A4 activity by 99% and 85%, respectively [48].

3.1.3. Elements

Aluminum and copper are two of the most abundant elements found in AN samples with relevance to drug metabolism, constituting about 7 −50 μg/g and 3.64 −8.77 μg/g, respectively [49, 50]. Rats chronically exposed to low-level aluminum (5 mg/kg/day for 21 days) had a 33% reduction in CYP2E1 activity and an over 50% increase in UGT activity [51]. Copper has been shown to inhibit human CYP1A2 (IC50 = 5.7 μM) and human CYP3A4 (IC50 = 8.4 μM) in vitro [52]. Copper exposure (60–500 μM) for 24 h to a human-relevant rat hepatoma cell model repressed (“inhibited”) the expression of GST pi (GSTP1) in a dose-dependent manner compared to non-copper treated cells [53]. Copper exhibited similar dose-dependent repression of CYP1A1/2, NQO1, SULT1C1, and UGT1A6 enzymes [53].

3.2. Betel Leaf

The betel leaf (Piper betle) is used to wrap the AN and other masticatory ingredients into a consumable preparation, such as BQ. The leaf is rich in phenolic compounds, such as safrole (15.35 mg/g), hydroxychavicol (9.74 mg/g), eugenol (2.51 mg/g), and quercetin (1.11 mg/g) [2]. Safrole, a class 2b carcinogen, is extensively metabolized with side chain oxidation mediated mainly by CYP2C9 and CYP2E1 [54]. Safrole is a potent inhibitor of human CYP1A2 (Ki of 1.5 μM), CYP2A6 (IC50 of 12 μM), and CYP2E1 (Ki of 2.8 μM), with weaker effects on CYP2D6 and CYP3A4 [55]. In hepatocytes, hydroxychavicol mainly undergoes sulfonation and glucuronidation with some glutathionylation [56] and is a potent inhibitor of XO with an IC50 value of 17 μM [57, 58]. Eugenol, a phenylpropanoid, is metabolized to hydroxychavicol by human CYP2D6 [59]. In human MC7 cells, eugenol dose-dependently inhibited CYP1A1 activity and also suppressed CYP1A1 induction by DMBA, a chemical carcinogen [60]. Rats administered dietary eugenol (5% w/w) for 4 weeks had a 40% reduction in CYP1A expression compared to control animals, while GST and UGT activities were increased by 100 −200% [61]. Eugenol-mediated induction of GST and UGT activity has been corroborated in other studies [62, 63].

3.3. Miscellaneous Additives and Spices

Menthol, a monoterpenoid found in the peppermint plant, is incorporated into various AN products, such as ready-made products sold in retail stores [4]. In branded pan masala samples, menthol content ranged from 1.1 to 6.5 mg/g in one study [64] and constituted 0.12 to 0.622% content in another study [65]. Menthol provides a cooling sensation in the mouth of users, which might counteract the irritative effects of the alkaloids during mastication, and may also temporarily freshen breath. Menthol has a significant interplay with drug disposition proteins. For instance, menthol undergoes glucuronidation via UGT2B7 and human UGT2B17 [66, 67]. Menthol (100 μM) and peppermint oil extract (a natural source of menthol) inhibited human carboxylesterase-1 (CES1) by up to 90% of control in vitro [68, 69]. Menthol inhibited UGT-catalyzed glucuronidation of the tobacco carcinogen NNAL in cells overexpressing various UGT isoenzymes and human liver microsomes [70]. Menthol impeded the CYP2D4-catalyzed metabolism of omeprazole (IC50 = 4.4 μM) and CYP1A2-mediated metabolism of phenacetin (IC50 = 8.7 μM) in rat liver microsomes [71]. However, menthol did not alter caffeine (CYP1A2 marker substrate) clearance in healthy female volunteers, although an effect on caffeine absorption was found [72]. Menthol (administered orally at 10 mg/kg for 7 days to mice) induced CYP2C-mediated metabolism of phenytoin and CYP3A-mediated metabolism of triazolam with a parallel increase in the expression of these proteins in the liver [73].

The same research group reported that menthol inhibited CYP2C9 mediated metabolism of warfarin in mice treated with 1 mg/kg for 2 days, which led to decreased clotting time (loss of warfarin efficacy) and an increase in hepatic CYP2C9 mRNA expression [74]. Likewise, CYP2C9 mRNA expression levels were increased in human hepatic cells exposed to 10 μM of menthol for 24 hr [74]. Furthermore, menthol inhibited human CYP3A4-catalyzed oxidation of nifedipine in vitro with a Ki of 87 μM [75]. Additionally, menthol inhibited both CYP2A6 and 2A13 in vitro, with more efficient inhibition of CYP2A13 (Ki of 8.2 μM and 110 μM for 2A6 and 2A13, respectively) [76]. Finally, among 11 human recombinant CYP isoenzymes tested, CYP2A6 was found to be the predominant catalyst of menthol hydroxylation [77].

Catechu is an astringent, reddish-brown substance that is often smudged on the betel leaf to facilitate the wrapping of BQ ingredients [2]. Black catechu, or “cutch”, is an extract prepared from the heartwood of Acacia catechu (Family-Leguminosae). Black catechu is rich in quercetin, catechins, and other phytochemicals and alkaloids [2]. Black catechu administered orally to rabbits at 264 mg/kg significantly reduced the clearance of theophylline, suggesting that it inhibits CYP1A isoenzymes [78]. Interestingly, rabbit CYP1A displays a similar metabolic capacity to its human homolog [79]. Aqueous and methanolic extracts of black catechu (100 μg/mL) inhibited human CYP3A4 activity by 96% and 62%, respectively [48].

Spices often incorporated into betel mixtures include cloves, cardamom, and aniseed [2]. Eugenol, as discussed above, is a major active ingredient in cloves. According to the work of Noumi et al. [80], the major chemical in cardamom species is 1,8-cineole, also known as “eucalyptol”, which is a substrate for human and rat CYP3A [81, 82]. Trans-anethole is a predominant constituent in aniseed essential oil (> 99%) [83]. In humans and rodents, trans-anethole is metabolized by CYP-mediated oxidation and to some extent, epoxidation to a cytotoxic metabolite trans-anethole-epoxide [84]. Trans-anethole (125 mg/kg x 10 days to rats) increased the hepatic activity of GST by 41% and UGT by 67% but did not influence hepatic CYP1A or CYP2B activity [62].

3.4. Tobacco

Nicotine, an alkaloid in the tobacco plant, is a powerfully addictive psychostimulant that undergoes vast metabolism in the body. For example, nicotine is a substrate for FMO, UGT, and methylase in humans, as well as various CYP450 isoenzymes, namely CYP2A6 [85]. Although some data suggests that nicotine induces the activity of CYP1A in rats [86–89], clinical studies did not confirm these results in humans, as chronic administration (42 mg/day of nicotine as a transdermal patch for 10 days) did not influence caffeine pharmacokinetics [90]. In rats, chronic nicotine exposure induced the activity of CYP2E1 [91]; however, nicotine did not alter chlorzoxazone (CYP2E1 marker substrate) pharmacokinetics in humans [92]. Seven-day nicotine treatment (1 mg/kg/d) significantly increased CYP2B expression and functionality by approximately 100% in rat brains [93].

Tobacco also contains a number of toxic nitrosamines, such as 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone (NNK), which is extensively metabolized in the body by various CYP enzymes [94]. NNK α-hydroxylation, resulting in metabolites capable of forming DNA adducts, is chiefly catalyzed by human CYP1A2, CYP2A6, CYP2B6, and CYP3A4 [94]. CYP2A13 is a major catalyst of NNK bioactivation in respiratory tissue [94]. NNK is also reduced to NNAL by carbonyl reductase and 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase [94, 95]. Analysis of tobacco leaves in BQ samples detected significant levels of arsenic (0.035 mg/kg), cadmium (0.028 mg/kg), and lead (0.42 mg/kg) [96]. Although the exact biotransformation mechanisms of arsenic are still debated, it is likely a substrate for GST omega and methylases [97]. It has been observed that mice exposed to arsenic (80 ppm in drinking water for 10 weeks) had modestly elevated tissue GST activity (~ 25%) compared to untreated mice [98]. In human hepatoma cells exposed to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), arsenic (5 μM) decreased PAH-mediated induction of CYP1A1/1A2 by 47% [99]. Cadmium, another constituent of tobacco, repressed CYP2E1 activity but did not impact CYP3A1 activity in rats [100]. In healthy human subjects exposed to low-level cadmium, accelerated CYP2A6-mediated warfarin metabolism [101] and pronounced effects on xenobiotic transport in the brain, kidneys, and liver were reported [102, 103]. Lead is an inducer of GSTs and CYP450 enzymes in rats [104, 105]. A clinical study found that mild-moderate lead poisoning in children did not interfere with the clearance of caffeine (CYP1A2 substrate) or dextromethorphan (CYP2D6 substrate). Due to its small sample size, this study should be interpreted cautiously. Moreover, this study did not study the effects of excessive lead exposure [106].

4. PREDICTIONS OF DRUG INTERACTIONS

Findings from this literature review revealed a wide array of chemicals in BQ components (areca nut, betel leaf, tobacco, and miscellaneous additives/spices), which collectively interplay with mammalian drug disposition enzymes and transporters (Figs. 1–3 and Table 1). Interplay with enzymes and transporters has been reported herein in not only animal species (e.g., rodents) but also in humans and sometimes a combination of human and animal data. Although findings derived from human models have the highest clinical relevance, animal data is still informative because pharmacokinetic profiling obtained in animals has been shown to translate to the human condition [107, 108]. In addition, animal (pre-clinical) data are often the first attempt to identify new hot topics of research on humans (clinical impact).

Collectively, this new body of information obtained in our literature review suggests that BQ consumers are at elevated risk for drug interactions when co-consuming medications and other therapeutic agents with overlapping metabolic patterns. The consequences of these drug interactions might include loss of efficacy in the case of enzyme induction/activation or enhanced pharmacotoxicity in the case of enzyme inhibition. In the case of pro-drugs, enzyme induction and enzyme inhibition could result in improved efficacy (with possible greater drug toxicities) and loss of efficacy, respectively. Given the widespread concerns of harmful adverse consequences as a consequence of drug interactions [109] and the dearth of data regarding the role of drug interactions in the global BQ health crisis, we subsequently sought to apply this information to predict (theorize) drug interactions in BQ consumers. Henceforth, the following sections highlight examples based on cross-referencing with information retrieved and analyzed from our initial literature review.

4.1. Phase I Metabolism

Phase I drug metabolism generally yields a polar, more water-soluble metabolite to facilitate excretion from the body. Among the phase I elimination mechanisms include oxidative reactions that are catalyzed via several enzyme families, such as FMOs and CYPs. FMOs oxidize an extensive array of N- and S-containing xenobiotics [110]. We identified two BQ constituents that are substrates for human FMO, namely AN alkaloid arecoline [18] and tobacco plant alkaloid nicotine [85]. In theory, during consumption of BQ, these substances would compete for similar metabolic active sites of the FMO enzyme, leaving one substance less metabolized and subject to accumulation in the body. In the case of arecoline, increased exposure would increase its toxicological profile as it is inherently an established toxicant [111]. Of additional significance is that various N-containing medications are metabolized by FMO, such as ranitidine, numerous tricyclic antidepressants, amphetamine, ephedrine, several 1st-generation antihistamines, clozapine, olanzapine, tamoxifen, voriconazole, and many other drugs [110]. S-containing agents metabolized by FMO include albendazole, cimetidine, propylthiouracil (PTU), clindamycin, and several other drugs [110]. Methimazole, an antithyroid medication used to manage hyperthyroidism, is an established inhibitor of human FMO [110] and may block the metabolism of arecoline or nicotine, leading to an untoward drug interaction.

Arecoline is the major toxic alkaloid found in the AN [112]. Chemically, it contains a methyl ester functional group, rendering it a likely substrate for hydrolases (esterases) [112]. The current literature shows that mouse carboxylesterase and pig liver esterase metabolize arecoline [19], although human esterase remains to be determined. Based on enzyme-substrate preferences, arecoline is likely a substrate for human carboxylesterase-1 (CES1) rather than human carboxylesterase-2 (CES2) [112, 113]. Clinically important agents that are inhibitors of CES1 include ethanol [114], simvastatin [70], several cannabinoids [115], and numerous natural products [116]. In addition, a handful of therapeutic agents and drugs of abuse are metabolized by CES1 [113].

CYP enzymes are hemeproteins that play an enormous role in metabolizing drugs and are a locus for substantial amounts of drug interactions observed in patients. Significantly, we uncovered 17 unique constituents of BQ that interact with CYP enzymes. For example, arecoline induced the expression and functionality of 6 different CYP enzymes, including CYP3A [20]. Although these findings were observed in rats, there is clinical evidence of human interaction. Taiwanese BQ chewers taking tacrolimus, a known CYP3A4/5 substrate [117], had lower trough concentrations of tacrolimus compared to non-chewers [118]. Other BQ constituents also interplay with CYP3A, including menthol, which has been shown to be an inducer and inhibitor of CYP3A4 [73, 75] and 1,8-cineole, which is a substrate for CYP3A in rats and humans [81, 82]. NNK, a nitrosamine toxin found in tobacco, is also a substrate for CYP3A4 [94]. On the contrary, catechu, quercetin, and copper are inhibitors of human CYP3A4 in vitro [44, 48, 52]. Given that CYP3A4 is the most abundant CYP in the body and metabolizes approximately 50% of currently available prescription drugs [119], the significance of BQ components interacting with this CYP cannot be overstated and thus clearly warrants further research.

Following our analysis, we uncovered a total of 9 chemicals present in BQ, exhibiting interplay with the CYP1A enzyme family. The majority of these chemicals can be classified as inhibitors, including arsenic [99], black catechu [34], copper [52], eugenol [61], menthol [71], safrole [55], and tannic acid [26]. Conversely, arecoline induces CYP1A2 [20], and NNK is a substrate for human CYP1A2 [94]. Clinically relevant drug substrates of CYP1A1/2 include acetaminophen, caffeine, theophylline, tizanidine, ropinirole, and numerous others [120]. Collectively, the metabolism of a CYP1A substrate (e.g., theophylline) could be impeded. The pretreatment of rabbits with black catechu, a CYP1A inhibitor, resulted in a significant increase in plasmatic theophylline exposure [78]. Since theophylline has a narrow therapeutic range, inhibition of its metabolism triggered by BQ consumption would lead to significant adverse effects (extreme nausea, vomiting, metabolic disturbances, cardiovascular toxicity, seizures) unless therapeutic drug monitoring is vigorously employed.

We found that a total of 7 BQ constituents interplay with the CYP2E enzyme family. Safrole, a chemical found in the betel leaf, acts as both a substrate and inhibitor of human CYP2E1 [54, 55]. Other human CYP2E1 inhibitors include epicatechin [38] and tannic acid [26], both of which are found in the AN. Several inducers were also reported, including aluminum [51], arecoline [20], and possibly nicotine [91]. With these differing effects on CYP2E function, it is difficult to predict drug interactions at this enzyme locus. Nonetheless, these results are intriguing as CYP2E enzymes generate reactive oxygen species (ROS) during metabolic reactions, metabolize a handful of drugs (acetaminophen, ethanol, and several anesthetics), and catalyze the bioactivation of procarcinogens [121].

CYP2A enzymes metabolize a few therapeutic entities, such as coumarin, letrozole, tegafur, and valproic acid [122]. BQ constituents interacting with CYP2A include safrole (inhibitor of human 2A6 [54]), menthol (substrate for human 2A6 [77] and inhibitor of human 2A6 and 2A13 [76]), nicotine (substrate for human 2A6 [85]), and NNK (substrate for human 2A6 and 2A13 [94]). Collectively, these chemicals are either substrates, inhibitors, or both, suggesting that the metabolism of co-consumed CYP2A substrate drugs may be hampered in BQ consumers, leading to potential pharmacotoxicity. In the case of tegafur, a prodrug, reduced metabolism might result in insufficient bioactivation to 5-fluorouracil and consequently impact its efficacy in treating cancer. Furthermore, nicotine, a component of BQ, is a substrate for human CYP2A6, while several other BQ chemicals inhibit this enzyme. A potential interaction could essentially lead to the accumulation of nicotine in the brain and perhaps enhance its psychostimulatory effects in BQ consumers.

Other CYPs identified in this study include CYP2B, CYP2C, and CYP2D. Chemicals in BQ exhibiting interplay with CYP2B in rats include arecoline (inducer) [20] and nicotine (inducer) [93], whereas NNK is a substrate for human CYP2B6 [94]. The induction of CYP2B in rat brain [93] was found to be consistent with the higher levels of human CYP2B6 found in the brains of smokers [123]. With the presumption that arecoline and nicotine induce human CYP2B enzymes in BQ users, consumption of BQ would not only affect the metabolism of CYP2B6 substrate drugs (e.g., bupropion, efavirenz, methadone, meperidine [124–127]), but also be implicated in tumorigenesis as CYP2B inducers, such as phenobarbital, increase the growth of liver tumors [128]. Arecoline (inducer) [20], menthol (inducer) [73, 74], quercetin (inhibitor) [44], and safrole (substrate) [54] were found to interact with rodent and/or human CYP2C enzymes. A significance of these findings is that 2C isoenzymes are the second most abundant CYP after 3A, representing over 20% of the total CYP present in the human liver [129]. Other 4 BQ constituents interact with CYP2D, including arecoline (inducer of rat CYP2D) [20], eugenol (substrate for human CYP2D6) [59], menthol (inhibitor of rat 2D4) [71], and quercetin (inhibitor of human 2D6 [44]). Along with CYP3A and CYP2C, the CYP2D enzyme family is a major metabolizer of prescription medications and other therapeutic substances. Collectively, there is potential for a plethora of drug interactions with CYP2C and CYP2D substrate drugs in BQ consumers. As an example, pain therapy may be hypothetically impacted. CYP2D6 plays a dominant role in activating several opioid prodrugs (codeine, tramadol, hydrocodone) [130]. A net inhibition of CYP2D6 by BQ constituents will lead to less activation and possible diminished efficacy (loss of pain control) if standard doses are administered. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents (NSAIDs), such as ibuprofen and celecoxib, are metabolized by CYP2C9 to less pharmacologically active metabolites [131]. A net CYP2C9 inductive effect elicited by BQ chemicals could result in reduced efficacy of NSAIDs.

Two BQ constituents found in the AN, tannic acid [24] and copper [53], inhibit NQO1. NQO1 catalyzes the reduction of chemically reactive quinone-like compounds, such as metabolites derived after drug bioactivation in the liver [132]. A net inhibition of NQO1 activity in BQ consumers could hamper this endogenous detoxification mechanism and place the user at risk for adverse effects.

XO is a molybdenum-containing enzyme playing an important role in purine catabolism and oxidizes antitumor drugs, such as azathioprine and 6-mercaptopurine [133]. Quercetin and two of its predominant circulating metabolites potently inhibit XO-mediated oxidation of 6-mercaptopurine [45], suggesting (although not proving) that concurrent ingestion of BQ and 6-mercaptopurine would lead to drug accumulation and associated toxic adverse effects, possibly mandating dose adjustments. Hydroxychavicol, intriguingly, is a more potent XO inhibitor than allopurinol [57], which is clinically used for the treatment of hyperuricemia. Furthermore, Tai et al. found that AN chewing is negatively associated with hyperuricemia [134].

4.2. Phase II Metabolism

Phase II DMEs aid in xenobiotic excretion from the body in the urine by catalyzing conjugation reactions with endogenous molecules to the drug substrate. BQ chemicals interplay with several phase II DMEs, mainly GST, SULT, and UGT. We uncovered 10 different constituents that interacted with GSTs in both animal and human physiologic models. Substrates for GSTs include hydroxychavicol [56], arsenic [97], and likely arecoline [112]. On the other hand, exposure to several BQ compounds induces tissue GST activity, including arsenic [98], eugenol [61–63], lead [104, 105], tannic acid (in kidney but not liver tissue) [24], and trans-anethole [62]. Arecoline has been reported to both inhibit and induce GST enzymes [14–17]. A primary metabolic role of GST enzymes is to catalyze the addition of glutathione (GSH) to reactive electrophilic xenobiotics, resulting in a less toxic derivative with greater water solubility [135]. Numerous alkylating chemotherapy agents (and/or their metabolites) are metabolized by GST-mediated GSH conjugation, such as busulfan, melphalan, cyclophosphamide, ifosfamide, and chlorambucil [136–138]. Additionally, the over-expression of tissue GST, such as GSTP, and GST enzyme induction, has been implicated in resistance to chemotherapy [135]. Taken together, BQ consumers are possibly at risk of drug interactions while co-ingesting chemotherapeutic agents that are cleared by GST enzymes, and these potential interactions might have significant clinical implications in cancer care.

SULT enzymes catalyze the sulfonation of numerous xenobiotics, hormones, and neurotransmitters. Sulfonation reactions generally lead to the detoxification of an active drug substance. Examples of SULT substrates include acetaminophen, various opioids, ethinyl estradiol, propofol, tamoxifen’s active metabolite, etc. [139]. A total of 5 chemicals identified in BQ were reported to interact with SULT enzymes. Substrates include catechin [33], epicatechin [35], and hydroxychavicol [56]. Copper [53], epicatechin [36], and quercetin [41] were identified as inhibitors of SULT enzymes in human cells and tissues. Altogether, BQ ingestion, such as, preparations with ample quercetin within the betel leaf and ripe AN [140], may hamper the metabolism of co-administered SULT substrates, thereby reducing the detoxification of the substrate drug. An example is the drug acetaminophen, which is heavily reliant on phase II metabolism (e.g., SULTs) for deactivation [141, 142]. Theoretically, inhibition of SULT by BQ constituents (e.g., quercetin, epicatechin, copper) could shunt acetaminophen metabolism to toxification pathways, increasing generation of the hepatotoxic acetaminophen metabolite N-acetyl-p-benzoquinone imine (NAPQI).

A total of 11 BQ constituents act as inducers, inhibitors, and/or substrates of UGT enzymes. Catechin [33], epicatechin [34], hydroxychavicol [56], menthol [66, 67], and nicotine [85] are all substrates for rodent and/or human UGT enzymes. UGT inhibitors include copper [53], epicatechin [36], and tannic acid [29]. Menthol’s inhibition of NNAL in cells and human liver microsomes was corroborated clinically in mentholated tobacco smokers [70]. Several inducers of UGTs were found, including aluminum [51], eugenol [61–63], quercetin [40], and trans-anethole [62]. UGTs catalyze the addition of glucuronic acid to xenobiotics, which in most cases, provides detoxification and aids secretion from the body. A number of therapeutic agents (and their metabolites) are metabolized by UGTs, including acetaminophen, opioids, NSAIDs, anticonvulsants, etc. [143]. With differing effects on UGT function, it is difficult to predict the net effect of BQ consumption on UGT enzyme activity. Given the extensive list of drug substrates for UGT and growing recognition of UGT’s impact on drug metabolism, more information about UGT-mediated metabolism in BQ consumers is certainly needed.

4.3. Drug Transporters

Drug transporter proteins play important roles in drug absorption (e.g., along the intestinal barrier), distribution into and out of various bodily tissues (e.g., brain, liver), and excretion from the body (e.g., kidney) [144]. Thus, modulation of their function can greatly affect the PK, efficacy, and toxicity of drugs [144]. Comparatively, we uncovered significantly fewer BQ constituents that interact with drug transporters than those that interact with phase I or phase II DMEs. Tannic acid, a component of the AN, downregulates (“inhibits”) human P-gp, MRP1, and MRP2 [30], and quercetin inhibits human BCRP, OATP1A2, OATP1B1, OATP1B3, and OATP2B1 [42]. In the same study, the authors found that quercetin’s glucuronide and sulfate conjugates also inhibited some of these transporters [42]. P-gp, BCRP, and MRP are efflux transporters that act as gatekeepers, limiting the absorption of xenobiotics across the intestinal lining, while OATPs generally function as influx transporters, aiding tissue uptake of drug substrates, such as rifampicin, methotrexate, antidiabetics, and statins [144]. Interestingly, quercetin inhibits both efflux and influx transporters; however, the net effect of drug PK in BQ consumers is especially challenging to predict. Tannic acid inhibits efflux transporters and may increase the absorption and brain penetration of drugs that are substrates for P-gp, BCRP, or MRP. For example, tannic acid’s modulation of drug efflux improved the antitumor effects of mitomycin C and 5-fluorouracil [30]. P-gp is one of the best-studied drug transporters with wide substrate specificity for structurally divergent compounds, such as protease inhibitors, calcium channel blockers, anticonvulsants, and anticancer drugs (e.g., vinca alkaloids, anthracyclines, and taxanes) [144].

Two alkaloids abundant in the AN, arecaidine and guvacine, are substrates for hPAT1, an intestinal transporter that facilitates absorption of small zwitterionic α-amino acids (e.g., proline, alanine) and the anticonvulsant vigabatrin [145]. Therefore, these alkaloids may compete with the intestinal uptake of vigabatrin. In such cases, this might reduce the bioavailability of vigabatrin and temper its antiseizure effects.

4.4. Miscellaneous

The BQ mixture consists of a rich supply of elements, including (but not limited to) aluminum, calcium, magnesium, and manganese [50]. As multivalent cations (e.g., Al3+, Ca2+, Mg2+, Mn2+) present in the GI tract of BQ chewers, they could chemically react with certain antibiotics, such as tetracyclines and fluoroquinolones, or even levothyroxine, in an established mechanism called chelation [146]. The formed chelate is insoluble and poorly absorbed across the intestinal barrier, leading to drastic reductions in systemic exposure, for example, of tetracycline (50 −90% lower) [146] and ciprofloxacin (43% lower) [147]. There is conflicting data on the significance of chelation-mediated interactions with levothyroxine, with one study reporting a reduction in levothyroxine exposure by 20–25% when co-administered with calcium formulations [148]. Taken together, our data suggest that BQ chewers, especially those who swallow (instead of spitting out) the juices from the mastication mixture, may be prone to chelation-based drug interactions in the GI tract. These effects will certainly be pronounced if the chewer is also taking multivitamin supplements or other products that contain polyvalent metal cations. Antibiotic and thyroid supplementation therapy in BQ users may require therapeutic adjustments (e.g., separation of drug administration by several hours from chewing, change in therapeutic agent, etc.).

4.5. Future Research

A significant portion of the world’s population still consumes BQ products [1–3], despite the well-documented myriad of health problems associated with their consumption [6]. Whether or not drug interactions contribute to these adverse health sequelae is an intriguing question. However, a study on it is still in its infancy. Our data provide new insight into potential drug interactions in BQ consumers, in which BQ ingredients may precipitate adverse pharmacokinetic (e.g., altered metabolism) and pharmacodynamic interactions (e.g., side effects, loss of efficacy). There is a probability for metabolic-based interactions with drugs from various therapeutic classes, such as analgesics, anticonvulsants, antimicrobials, cancer chemotherapeutics, drugs of abuse, thyroid medications, and possibly others (Fig. 4). To make definitive conclusions about these interactions, further information is required, such as the concentrations and subsequent pharmacokinetic profiles of BQ chemicals in the bloodstream of both acute and chronic users. Besides areca alkaloids, very little is known about how much of BQ constituents (e.g., tannic acid and quercetin that have the potential to elicit various drug interactions) reach systemic circulation in BQ consumers, and far less is known about relative tissue amounts, such as in the liver where the bulk of drug metabolism occurs in the body. If this information is in hand, we can cross-check if a sufficient compound is present in circulation to eclipse the threshold for interactions to occur, such as enzyme inhibition (e.g., concentrations exceeding the IC50). Certainly, head-to-head clinical studies (e.g., evaluating pharmacokinetics-pharmacodynamics of patients administered BQ plus drug versus drug alone) would be a boon. With the absence of clinical data, we can employ in vivo human-relevant models (e.g., humanized mice) to study intriguing predictions derived in this review. Further studies in human hepatocytes and physiologically based pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic models could be useful. Another approach is to vigorously monitor BQ users (e.g., obtaining a detailed medication history) presenting to the clinic with health problems, such as those prescribed with new pharmacotherapy consisting of narrow therapeutic index drugs, the concentrations of which can be readily measured in blood. This approach can identify drug interactions in the clinic and prompt follow-up mechanism-based studies. With further information, multitudes of public health research projects could be instituted to disseminate this information to other scientists, health care providers, and the public in general.

Fig. (4).

Consumption of BQ potentially elicits drug interactions with medications from various therapeutic classes.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, we discovered that a plethora of chemicals present in the BQ mastication mixture has dynamic interplay (e.g., substrate, inhibition, induction) with various DMEs (both Phase I and Phase II) and drug transporters. Our analysis predicted that the BQ consumer is at risk for metabolic drug interactions with drugs from vast therapeutic classes, the consequence of which may encompass pharmacotoxicity and/or failed efficacy. Our novel set of knowledge is most likely poorly known by BQ consumers and their prescribing clinicians. Therefore, further laboratory and clinical research are required based on our predictions, further specifying harmful drug interactions precipitated by BQ consumption, which would ultimately aid in improving the overall health of BQ users.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge Henry Touchton, BS, for providing initial input for the literature review.

FUNDING

This study was supported by The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, School of Dentistry Summer Research Program, and National Institute of Health/National Institute of Drug Abuse (NIH/NIDA).

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

- AN

Areca Nut

- BQ

Betel Quid

- DME

Drug-Metabolizing Enzymes

- GST

Glutathione S-Transferase

- OTC

Over-the-Counter

- SULT

Sulfotransferase

- UGT

UDP-Glucuronosyltransferase

Footnotes

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Not applicable.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

REFERENCES

- [1].Gupta PC; Warnakulasuriya S. Global epidemiology of areca nut usage. Addict. Biol, 2002, 7(1), 77–83. 10.1080/13556210020091437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Humans IWGECR Betel-quid and areca-nut chewing and some areca-nut derived nitrosamines. IARC Monogr. Eval. Carcinog. Risks Hum, 2004, 85, 1–334. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Moss WJ The seeds of ignorance-consequences of a booming betel-nut economy. N. Engl. J. Med, 2022, 387(12), 1059–1061. 10.1056/NEJMp2203571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Tungare S; Myers AL Retail availability and characteristics of addictive areca nut products in a US metropolis. J. Psychoactive Drugs, 2021, 53(3), 256–271. 10.1080/02791072.2020.1860272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Winstock A. Areca nut-abuse liability, dependence and public health. Addict. Biol., 2002, 7(1), 133–138. 10.1080/13556210120091509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Islam S; Muthumala M; Matsuoka H; Uehara O; Kuramitsu Y; Chiba I; Abiko Y. How each component of betel quid is involved in oral carcinogenesis: Mutual interactions and synergistic effects with other carcinogens-A review article. Curr. Oncol. Rep, 2019, 21(6), 53. 10.1007/s11912-019-0800-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Ko YC; Chiang TA; Chang SJ; Hsieh SF Prevalence of betel quid chewing habit in Taiwan and related sociodemographic factors. J. Oral Pathol. Med, 1992, 21(6), 261–264. 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1992.tb01007.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Lan TY; Chang WC; Tsai YJ; Chuang YL; Lin HS; Tai TY Areca nut chewing and mortality in an elderly cohort study. Am. J. Epidemiol, 2007, 165(6), 677–683. 10.1093/aje/kwk056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Huang JL; McLeish MJ High-performance liquid chromatographic determination of the alkaloids in betel nut. J. Chromatogr. A, 1989, 475(2), 447–450. 10.1016/S0021-9673(01)89702-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Shivashankar S; Dhanaraj S; Matthew A; Murthy SS; Vyasamurthy MN; Govindarajan VS Physical and chemical characteristics of processed arecanuts. J. Food Sci. Technol., 1969, 6(2), 113–116. [Google Scholar]

- [11].Yang Y; Huang H; Cui Z; Chu J; Du G. UPLC–MS/MS and network pharmacology-based analysis of bioactive anti-depression compounds in betel nut. Drug Des. Devel. Ther, 2021, 15, 4827–4836. 10.2147/DDDT.S335312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Franke AA; Mendez AJ; Lai JF; Arat-Cabading C; Li X; Custer LJ Composition of betel specific chemicals in saliva during betel chewing for the identification of biomarkers. Food Chem. Toxicol, 2015, 80, 241–246. 10.1016/j.fct.2015.03.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Jain V; Garg A; Parascandola M; Chaturvedi P; Khariwala SS; Stepanov I. Analysis of alkaloids in areca nut-containing products by liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry. J. Agric. Food Chem, 2017, 65(9), 1977–1983. 10.1021/acs.jafc.6b05140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Chang YC; Hu CC; Tseng TH; Tai KW; Lii CK; Chou MY Synergistic effects of nicotine on arecoline-induced cytotoxicity in human buccal mucosal fibroblasts. J. Oral Pathol. Med, 2001, 30(8), 458–464. 10.1034/j.1600-0714.2001.030008458.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Dasgupta R; Saha I; Pal S; Bhattacharyya A; Sa G; Nag TC; Das T; Maiti BR Immunosuppression, hepatotoxicity and depression of antioxidant status by arecoline in albino mice. Toxicology, 2006, 227(1–2), 94–104. 10.1016/j.tox.2006.07.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Zhou J; Sun Q; Yang Z; Zhang J. The hepatotoxicity and testicular toxicity induced by arecoline in mice and protective effects of vitamins C and e. Korean J. Physiol. Pharmacol, 2014, 18(2), 143–148. 10.4196/kjpp.2014.18.2.143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Singh A; Rao AR Effects of arecoline on phase I and phase II drug metabolizing system enzymes, sulfhydryl content and lipid peroxidation in mouse liver. Biochem. Mol. Biol. Int, 1993, 30(4), 763–772. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Giri S; Krausz KW; Idle JR; Gonzalez FJ The metabolomics of (±)-arecoline 1-oxide in the mouse and its formation by human flavin-containing monooxygenases. Biochem. Pharmacol, 2007, 73(4), 561–573. 10.1016/j.bcp.2006.10.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Patterson TA; Kosh JW Elucidation of the rapid in vivo metabolism of arecoline. Gen. Pharmacol, 1993, 24(3), 641–647. 10.1016/0306-3623(93)90224-L [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Run-mei X; Jun-jun W; Jing-ya C; Li-juan S; Yong C. Effects of arecoline on hepatic cytochrome P450 activity and oxidative stress. J. Toxicol. Sci, 2014, 39(4), 609–614. 10.2131/jts.39.609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Voigt V; Laug L; Zebisch K; Thondorf I; Markwardt F; Brandsch M. Transport of the areca nut alkaloid arecaidine by the human proton-coupled amino acid transporter 1 (hPAT1). J. Pharm. Pharmacol, 2013, 65(4), 582–590. 10.1111/jphp.12006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Gurumurthy BR Diversity in tannin and fiber content in areca nut (Areca catechu) samples of Karnataka, India. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci, 2018, 7(1), 2899–2906. 10.20546/ijcmas.2018.701.346 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Adamczyk B; Simon J; Kitunen V; Adamczyk S; Smolander A. Tannins and their complex interaction with different organic nitrogen compounds and enzymes: Old paradigms versus recent advances. ChemistryOpen, 2017, 6(5), 610–614. 10.1002/open.201700113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Krajka-Kuźniak V; Baer-Dubowska W. The effects of tannic acid on cytochrome P450 and phase II enzymes in mouse liver and kidney. Toxicol. Lett, 2003, 143(2), 209–216. 10.1016/S0378-4274(03)00177-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Karakurt S; Adali O. Effect of tannic acid on glutathione S-transferase and NAD(P)H: Quinone oxidoreductase 1 enzymes in rabbit liver and kidney. Fresenius Environ. Bull, 2011, 20(7a), 1804–1811. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Yao HT; Chang YW; Lan SJ; Yeh TK The inhibitory effect of tannic acid on cytochrome P450 enzymes and NADPH-CYP reductase in rat and human liver microsomes. Food Chem. Toxicol, 2008, 46(2), 645–653. 10.1016/j.fct.2007.09.073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Mikstacka R; Gnojkowski J; Baer-Dubowska W. Effect of natural phenols on the catalytic activity of cytochrome P450 2E1. Acta Biochim. Pol, 2002, 49(4), 917–925. 10.18388/abp.2002_3751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Pillai VC; Mehvar R. Inhibition of NADPH-cytochrome P450 reductase by tannic acid in rat liver microsomes and primary hepatocytes: Methodological artifacts and application to ischemia–reperfusion injury. J. Pharm. Sci, 2011, 100(8), 3495–3505. 10.1002/jps.22531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Grancharov K; Engelberg H; Naydenova Z; Müller G; Rettenmeier A; Golovinsky E. Inhibition of UDP-glucuronosyltransferases in rat liver microsomes by natural mutagens and carcinogens. Arch. Toxicol, 2001, 75(10), 609–612. 10.1007/s00204-001-0282-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Naus PJ; Henson R; Bleeker G; Wehbe H; Meng F; Patel T. Tannic acid synergizes the cytotoxicity of chemotherapeutic drugs in human cholangiocarcinoma by modulating drug efflux pathways. J. Hepatol, 2007, 46(2), 222–229. 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.08.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Sari LM; Hakim RF; Mubarak Z; Andriyanto A. Analysis of phenolic compounds and immunomodulatory activity of areca nut extract from Aceh, Indonesia, against Staphylococcus aureus infection in Sprague-Dawley rats. Vet. World, 2020, 13(1), 134–140. 10.14202/vetworld.2020.134-140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Yong Feng W. Metabolism of green tea catechins: An overview. Curr. Drug Metab, 2006, 7(7), 755–809. 10.2174/138920006778520552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Donovan JL; Crespy V; Manach C; Morand C; Besson C; Scalbert A; Rémésy C. Catechin is metabolized by both the small intestine and liver of rats. J. Nutr, 2001, 131(6), 1753–1757. 10.1093/jn/131.6.1753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Abd El Mohsen MM; Kuhnle G; Rechner AR; Schroeter H; Rose S; Jenner P; Rice-Evans CA Uptake and metabolism of epicatechin and its access to the brain after oral ingestion. Free Radic. Biol. Med, 2002, 33(12), 1693–1702. 10.1016/S0891-5849(02)01137-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Baba S; Osakabe N; Natsume M; Muto Y; Takizawa T; Terao J. In vivo comparison of the bioavailability of (+)-catechin, (−)-epicatechin and their mixture in orally administered rats. J. Nutr, 2001, 131(11), 2885–2891. 10.1093/jn/131.11.2885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Fong YK; Li CR; Wo SK; Wang S; Zhou L; Zhang L; Lin G; Zuo Z. In vitro and in situ evaluation of herb–drug interactions during intestinal metabolism and absorption of Baicalein. J. Ethnopharmacol, 2012, 141(2), 742–753. 10.1016/j.jep.2011.08.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Mizuma T; Awazu S. Dietary polyphenols (−)-epicatechin and chrysin inhibit intestinal glucuronidation metabolism to increase drug absorption. J. Pharm. Sci, 2004, 93(9), 2407–2410. 10.1002/jps.20146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Muto S; Fujita K; Yamazaki Y; Kamataki T. Inhibition by green tea catechins of metabolic activation of procarcinogens by human cytochrome P450. Mutat. Res, 2001, 479(1–2), 197–206. 10.1016/S0027-5107(01)00204-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Boersma MG; van der Woude H; Bogaards J; Boeren S; Vervoort J; Cnubben NHP; van Iersel MLPS; van Bladeren PJ; Rietjens IMCM Regioselectivity of phase II metabolism of luteolin and quercetin by UDP-glucuronosyl transferases. Chem. Res. Toxicol, 2002, 15(5), 662–670. 10.1021/tx0101705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Galijatovic A; Walle UK; Walle T. Induction of UDP-glucuronosyltransferase by the flavonoids chrysin and quercetin in Caco-2 cells. Pharm. Res, 2000, 17(1), 21–26. 10.1023/A:1007506222436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].De Santi C; Pietrabissa A; Mosca F; Rane A; Pacifici GM Inhibition of phenol sulfotransferase (SULT1A1) by quercetin in human adult and foetal livers. Xenobiotica, 2002, 32(5), 363–368. 10.1080/00498250110119108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Mohos V; Fliszár-Nyúl E; Ungvári O; Kuffa K; Needs PW; Kroon PA; Telbisz Á; Özvegy-Laczka C; Poór M. Inhibitory effects of quercetin and its main methyl, sulfate, and glucuronic acid conjugates on cytochrome P450 enzymes, and on OATP, BCRP and MRP2 transporters. Nutrients, 2020, 12(8), 2306. 10.3390/nu12082306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Liu Y; Luo X; Yang C; Yang T; Zhou J; Shi S. Impact of quercetin-induced changes in drug-metabolizing enzyme and transporter expression on the pharmacokinetics of cyclosporine in rats. Mol. Med. Rep, 2016, 14(4), 3073–3085. 10.3892/mmr.2016.5616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Elbarbry F; Ung A; Abdelkawy K. Studying the inhibitory effect of quercetin and thymoquinone on human cytochrome p450 enzyme activities. Pharmacogn. Mag, 2018, 13(Suppl. 4), S895–S899. 10.4103/0973-1296.224342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Mohos V; Pánovics A; Fliszár-Nyúl E; Schilli G; Hetényi C; Mladěnka P; Needs PW; Kroon PA; Pethő G; Poór M. Inhibitory effects of quercetin and its human and microbial metabolites on xanthine oxidase enzyme. Int. J. Mol. Sci, 2019, 20(11), 2681. 10.3390/ijms20112681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Nagao A; Seki M; Kobayashi H. Inhibition of xanthine oxidase by flavonoids. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem, 1999, 63(10), 1787–1790. 10.1271/bbb.63.1787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Van Hoorn DEC; Nijveldt RJ; Van Leeuwen PAM; Hofman Z; M’Rabet L; De Bont DBA; Van Norren K. Accurate prediction of xanthine oxidase inhibition based on the structure of flavonoids. Eur. J. Pharmacol, 2002, 451(2), 111–118. 10.1016/S0014-2999(02)02192-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Wink M; Ashour ML; Youssef FS; Gad HA Inhibition of cytochrome P450 (CYP3A4) activity by extracts from 57 plants used in traditional chinese medicine (TCM). Pharmacogn. Mag., 2017, 13(50), 300–308. 10.4103/0973-1296.204561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Mathew P; Austin RD; Varghese SS; Manojkumar, Estimation and comparison of copper content in raw areca nuts and commercial areca nut products: Implications in increasing prevalence of oral submucous fibrosis. J. Clin. Diagn. Res, 2014, 8(1), 247–249. 10.7860/JCDR/2014/8042.3932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Spyrou NM; Akanle O; Spyrou NM Elemental composition of betel nut and associated chewing materials. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem, 2001, 249(1), 67–70. 10.1023/A:1013273421535 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Bidlack WR; Brown RC; Meskin MS; Lee TC; Klein GL Effect of aluminum on the hepatic mixed function oxidase and drug metabolism. Drug Nutr. Interact, 1987, 5(1), 33–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Kim JS; Ahn T; Yim SK; Yun CH Differential effect of copper (II) on the cytochrome P450 enzymes and NADPH-cytochrome P450 reductase: Inhibition of cytochrome P450-catalyzed reactions by copper (II) ion. Biochemistry, 2002, 41(30), 9438–9447. 10.1021/bi025908b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Darwish WS; Ikenaka Y; Nakayama S; Ishizuka M. The effect of copper on the mRNA expression profile of xenobiotic-metabolizing enzymes in cultured rat H4-II-E cells. Biol. Trace Elem. Res, 2014, 158(2), 243–248. 10.1007/s12011-014-9915-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Ueng YF; Hsieh CH; Don MJ; Chi CW; Ho LK Identification of the main human cytochrome P450 enzymes involved in safrole 1′-hydroxylation. Chem. Res. Toxicol, 2004, 17(8), 1151–1156. 10.1021/tx030055p [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Ueng YF; Hsieh CH; Don MJ Inhibition of human cytochrome P450 enzymes by the natural hepatotoxin safrole. Food Chem. Toxicol, 2005, 43(5), 707–712. 10.1016/j.fct.2005.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Nakagawa Y; Suzuki T; Nakajima K; Ishii H; Ogata A. Biotransformation and cytotoxic effects of hydroxychavicol, an intermediate of safrole metabolism, in isolated rat hepatocytes. Chem. Biol. Interact, 2009, 180(1), 89–97. 10.1016/j.cbi.2009.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Murata K; Nakao K; Hirata N; Namba K; Nomi T; Kitamura Y; Moriyama K; Shintani T; Iinuma M; Matsuda H. Hydroxychavicol: A potent xanthine oxidase inhibitor obtained from the leaves of betel, Piper betle. J. Nat. Med, 2009, 63(3), 355–359. 10.1007/s11418-009-0331-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Nishiwaki K; Ohigashi K; Deguchi T; Murata K; Nakamura S; Matsuda H; Nakanishi I. Structure–activity relationships and docking studies of hydroxychavicol and its analogs as xanthine oxidase inhibitors. Chem. Pharm. Bull, 2018, 66(7), 741–747. 10.1248/cpb.c18-00197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Sakano K; Inagaki Y; Oikawa S; Hiraku Y; Kawanishi S. Copper-mediated oxidative DNA damage induced by eugenol: Possible involvement of O-demethylation. Mutat. Res. Genet. Toxicol. Environ. Mutagen, 2004, 565(1), 35–44. 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2004.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Han EH; Hwang YP; Jeong TC; Lee SS; Shin JG; Jeong HG Eugenol inhibit 7,12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene-induced genotoxicity in MCF-7 cells: Bifunctional effects on CYP1 and NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase. FEBS Lett, 2007, 581(4), 749–756. 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.01.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Iwano H; Ujita W; Nishikawa M; Ishii S; Inoue H; Yokota H. Effect of dietary eugenol on xenobiotic metabolism and mediation of UDP-glucuronosyltransferase and cytochrome P450 1A1 expression in rat liver. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr., 2014, 65(2), 241–244. 10.3109/09637486.2013.845650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Rompelberg CJM; Verhagen H; van Bladeren PJ Effects of the naturally occurring alkenylbenzenes eugenol and trans-anethole on drug-metabolizing enzymes in the rat liver. Food Chem. Toxicol, 1993, 31(9), 637–645. 10.1016/0278-6915(93)90046-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Yokota H; Hashimoto H; Motoya M; Yuasa A. Enhancement of UDP-glucuronyltransferase, UDP-glucose dehydrogenase, and glutathione S-transferase activities in rat liver by dietary administration of eugenol. Biochem. Pharmacol, 1988, 37(5), 799–802. 10.1016/0006-2952(88)90164-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Kannan A; Das M; Khanna SK Estimation of menthol in pan masala samples by a spectrophotometric method. Food Addit. Contam, 1997, 14(4), 367–371. 10.1080/02652039709374539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Rao MV; Krishnamurthy MN; Nagaraja KV; Kapur OP Gas chromatographic determination of menthol in mentholated sweets and Pan Masala. J. Food Sci. Technol., 1983, 20, 130–131. [Google Scholar]

- [66].Coffman BL; King CD; Rios GR; Tephly TR The glucuronidation of opioids, other xenobiotics, and androgens by human UGT2B7Y(268) and UGT2B7H(268). Drug Metab. Dispos, 1998, 26(1), 73–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Turgeon D; Carrier JS; Chouinard S; Bélanger A. Glucuronidation activity of the UGT2B17 enzyme toward xenobiotics. Drug Metab. Dispos, 2003, 31(5), 670–676. 10.1124/dmd.31.5.670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Mazhar H; Robaey P; Harris C. An in vitro evaluation of the inhibition of recombinant human carboxylesterase-1 by herbal extracts. J. Nat. Health Prod. Res, 2021, 3(1), 1–14. 10.33211/jnhpr.11 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Shimizu M; Fukami T; Nakajima M; Yokoi T. Screening of specific inhibitors for human carboxylesterases or arylacetamide deacetylase. Drug Metab. Dispos, 2014, 42(7), 1103–1109. 10.1124/dmd.114.056994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Kozlovich S; Chen G; Watson CJW; Blot WJ; Lazarus P. Role of l- and d-menthol in the glucuronidation and detoxification of the major lung carcinogen, NNAL. Drug Metab. Dispos, 2019, 47(12), 1388–1396. 10.1124/dmd.119.088351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Feng X; Liu Y; Sun X; Li A; Jiang X; Zhu X; Zhao Z. Pharmacokinetics behaviors of l -menthol after inhalation and intravenous injection in rats and its inhibition effects on CYP450 enzymes in rat liver microsomes. Xenobiotica, 2019, 49(10), 1183–1191. 10.1080/00498254.2018.1537531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Gelal A; Guven H; Balkan D; Artok L; Benowitz NL Influence of menthol on caffeine disposition and pharmacodynamics in healthy female volunteers. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol, 2003, 59(5–6), 417–422. 10.1007/s00228-003-0631-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Hoshino M; Ikarashi N; Hirobe R; Hayashi M; Hiraoka H; Yokobori K; Ochiai T; Kusunoki Y; Kon R; Tajima M; Ochiai W; Sugiyama K. Effects of menthol on the pharmacokinetics of triazolam and phenytoin. Biol. Pharm. Bull, 2015, 38(3), 454–460. 10.1248/bpb.b14-00764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Hoshino M; Ikarashi N; Tsukui M; Kurokawa A; Naito R; Suzuki M; Yokobori K; Ochiai T; Ishii M; Kusunoki Y; Kon R; Ochiai W; Wakui N; Machida Y; Sugiyama K. Menthol reduces the anticoagulant effect of warfarin by inducing cytochrome P450 2C expression. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci, 2014, 56, 92–101. 10.1016/j.ejps.2014.02.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Dresser GK; Wacher V; Wong S; Wong HT; Bailey DG Evaluation of peppermint oil and ascorbyl palmitate as inhibitors of cytochrome P4503A4 activity in vitro and in vivo. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther, 2002, 72(3), 247–255. 10.1067/mcp.2002.126409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Kramlinger VM; von Weymarn LB; Murphy SE Inhibition and inactivation of cytochrome P450 2A6 and cytochrome P450 2A13 by menthofuran, β-nicotyrine and menthol. Chem. Biol. Interact, 2012, 197(2–3), 87–92. 10.1016/j.cbi.2012.03.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Miyazawa M; Marumoto S; Takahashi T; Nakahashi H; Haigou R; Nakanishi K. Metabolism of (+)- and (−)-menthols by CYP2A6 in human liver microsomes. J. Oleo Sci., 2011, 60(3), 127–132. 10.5650/jos.60.127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Al-Mohizea AM; Raish M; Ahad A; Al-Jenoobi FI; Alam MA Pharmacokinetic interaction of Acacia catechu with CYP1A substrate theophylline in rabbits. J. Tradit. Chin. Med, 2015, 35(5), 588–593. 10.1016/S0254-6272(15)30144-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Bogaards JJP; Bertrand M; Jackson P; Oudshoorn MJ; Weaver RJ; Van Bladeren PJ; Walther B. Determining the best animal model for human cytochrome P450 activities: A comparison of mouse, rat, rabbit, dog, micropig, monkey and man. Xenobiotica, 2000, 30(12), 1131–1152. 10.1080/00498250010021684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Noumi E; Snoussi M; Alreshidi M; Rekha PD; Saptami K; Caputo L; De Martino L; Souza L; Msaada K; Mancini E; Flamini G; Al-sieni A; De Feo V. Chemical and biological evaluation of essential oils from cardamom species. Molecules, 2018, 23(11), 2818. 10.3390/molecules23112818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Duisken M; Sandner F; Blömeke B; Hollender J. Metabolism of 1,8-cineole by human cytochrome P450 enzymes: Identification of a new hydroxylated metabolite. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Gen. Subj., 2005, 1722(3), 304–311. 10.1016/j.bbagen.2004.12.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Miyazawa M; Shindo M; Shimada T. Oxidation of 1,8-cineole, the monoterpene cyclic ether originated from eucalyptus polybractea, by cytochrome P450 3A enzymes in rat and human liver microsomes. Drug Metab. Dispos, 2001, 29(2), 200–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Samojlik I; Petković S; Stilinović N; Vukmirović S; Mijatović V; Božin B. Pharmacokinetic herb-drug interaction between essential oil of aniseed ( Pimpinella anisum L., Apiaceae) and acetaminophen and caffeine: A potential risk for clinical practice. Phytother. Res., 2016, 30(2), 253–259. 10.1002/ptr.5523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Newberne P; Smith RL; Doull J; Goodman JI; Munro IC; Portoghese PS; Wagner BM; Weil CS; Woods LA; Adams TB; Lucas CD; Ford RA The FEMA GRAS assessment of trans-anethole used as a flavouring substance. Food Chem. Toxicol, 1999, 37(7), 789–811. 10.1016/S0278-6915(99)00037-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Benowitz NL; Hukkanen J; Jacob P III Nicotine chemistry, metabolism, kinetics and biomarkers. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol, 2009, 192(192), 29–60. 10.1007/978-3-540-69248-5_2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Iba MM; Fung J. Induction of pulmonary cytochrome P4501A1: Interactive effects of nicotine and mecamylamine. Eur. J. Pharmacol, 1999, 383(3), 399–403. 10.1016/S0014-2999(99)00639-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Iba MM; Fung J; Pak YW; Thomas PE; Fisher H; Sekowski A; Halladay AK; Wagner GC Dose-dependent up-regulation of rat pulmonary, renal, and hepatic cytochrome P-450 (CYP) 1A expression by nicotine feeding. Drug Metab. Dispos, 1999, 27(9), 977–982. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Iba MM; Scholl H; Fung J; Thomas PE; Alam J. Induction of pulmonary CYP1A1 by nicotine. Xenobiotica, 1998, 28(9), 827–843. 10.1080/004982598239083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Price RJ; Renwick AB; Walters DG; Young PJ; Lake BG Metabolism of nicotine and induction of CYP1A forms in precision-cut rat liver and lung slices. Toxicol. in vitro, 2004, 18(2), 179–185. 10.1016/j.tiv.2003.08.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Hukkanen J; Jacob P III; Peng M; Dempsey D; Benowitz NL Effect of nicotine on cytochrome P450 1A2 activity. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol, 2011, 72(5), 836–838. 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2011.04023.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Yue J; Khokhar J; Miksys S; Tyndale RF Differential induction of ethanol-metabolizing CYP2E1 and nicotine-metabolizing CYP2B1/2 in rat liver by chronic nicotine treatment and voluntary ethanol intake. Eur. J. Pharmacol, 2009, 609(1–3), 88–95. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2009.03.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Hukkanen J; Jacob P III; Peng M; Dempsey D; Benowitz NL Effects of nicotine on cytochrome P450 2A6 and 2E1 activities. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol, 2010, 69(2), 152–159. 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2009.03568.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Khokhar JY; Miksys SL; Tyndale RF Rat brain CYP2B induction by nicotine is persistent and does not involve nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Brain Res, 2010, 1348, 1–9. 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.06.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Jalas JR; Hecht SS; Murphy SE Cytochrome P450 enzymes as catalysts of metabolism of 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone, a tobacco specific carcinogen. Chem. Res. Toxicol, 2005, 18(2), 95–110. 10.1021/tx049847p [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Maser E; Stinner B; Atalla A. Carbonyl reduction of 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone (NNK) by cytosolic enzymes in human liver and lung. Cancer Lett, 2000, 148(2), 135–144. 10.1016/S0304-3835(99)00323-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Al-Rmalli SW; Jenkins RO; Haris PI Betel quid chewing elevates human exposure to arsenic, cadmium and lead. J. Hazard. Mater, 2011, 190(1–3), 69–74. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2011.02.068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Aposhian HV; Aposhian MM Arsenic toxicology: Five questions. Chem. Res. Toxicol, 2006, 19(1), 1–15. 10.1021/tx050106d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Xie Y; Liu J; Liu Y; Klaassen CD; Waalkes MP Toxicokinetic and genomic analysis of chronic arsenic exposure in multidrug-resistance MDR1a/1b(−/−) double knockout mice. Mol. Cell. Biochem, 2004, 255(1/2), 11–18. 10.1023/B:MCBI.0000007256.44450.8c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [99].Vakharia DD; Liu N; Pause R; Fasco M; Bessette E; Zhang QY; Kaminsky LS Effect of metals on polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon induction of CYP1A1 and CYP1A2 in human hepatocyte cultures. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol, 2001, 170(2), 93–103. 10.1006/taap.2000.9087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [100].Alexidis AN; Rekka EA; Kourounakis PN Influence of mercury and cadmium intoxication on hepatic microsomal CYP2E and CYP3A subfamilies. Res. Commun. Mol. Pathol. Pharmacol, 1994, 85(1), 67–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [101].Satarug S; Nishijo M; Ujjin P; Vanavanitkun Y; Baker JR; Moore MR Effects of chronic exposure to low-level cadmium on renal tubular function and CYP2A6-mediated coumarin metabolism in healthy human subjects. Toxicol. Lett, 2004, 148(3), 187–197. 10.1016/j.toxlet.2003.10.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [102].Wang H; Zhang L; Xia Z; Cui JY Effect of chronic cadmium exposure on brain and liver transporters and drug-metabolizing enzymes in male and female mice genetically predisposed to Alzheimer’s disease. Drug Metab. Dispos, 2022, 50(10), 1414–1428. 10.1124/dmd.121.000453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [103].Yang H; Zhou S; Guo D; Obianom ON; Li Q; Shu Y. Divergent regulation of OCT and MATE drug transporters by cadmium exposure. Pharmaceutics, 2021, 13(4), 537. 10.3390/pharmaceutics13040537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [104].Nehru B; Kaushal S. Effect of lead on hepatic microsomal enzyme activity. J. Appl. Toxicol, 1992, 12(6), 401–405. 10.1002/jat.2550120607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [105].Wright L; Kornguth SE; Oberley TD; Siegel FL Effects of lead on glutathione S-transferase expression in rat kidney: A dose-response study. Toxicol. Sci, 1998, 46(2), 254–259. 10.1006/toxs.1998.2543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [106].Lowry JA; Pearce RE; Gaedigk A; Venneman M; Talib N; Leeder JS; Kearns GL Lead and its effects on cytochromes P450. J. Drug Metab. Toxicol, 2012, S5(004). 10.4172/2157-7609.S5-004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [107].de Jong M; Maina T. Of mice and humans: Are they the same?--Implications in cancer translational research. J. Nucl. Med, 2010, 51(4), 501–504. 10.2967/jnumed.109.065706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [108].Zhao M; Lepak AJ; Andes DR Animal models in the pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic evaluation of antimicrobial agents. Bioorg. Med. Chem, 2016, 24(24), 6390–6400. 10.1016/j.bmc.2016.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [109].Magro L; Arzenton E; Leone R; Stano MG; Vezzaro M; Rudolph A; Castagna I; Moretti U. Identifying and characterizing serious adverse drug reactions associated with drug-drug interactions in a spontaneous reporting database. Front. Pharmacol, 2021, 11, 622862. 10.3389/fphar.2020.622862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [110].Krueger SK; Williams DE Mammalian flavin-containing monooxygenases: Structure/function, genetic polymorphisms and role in drug metabolism. Pharmacol. Ther, 2005, 106(3), 357–387. 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.01.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]