Abstract

Delirium, a syndrome characterized by an acute change in attention, awareness, and cognition, is commonly observed in older adults, although there are few quantitative monitoring methods in the clinical setting. We developed a bispectral electroencephalography (BSEEG) method capable of detecting delirium and can quantify the severity of delirium using a novel algorithm. Preclinical application of this novel BSEEG method can capture a delirium-like state in mice following lipopolysaccharide administration. However, its application to postoperative delirium (POD) has not yet been validated in animal experiments. This study aimed to create a POD model in mice with the BSEEG method by monitoring BSEEG scores following EEG head-mount implantation surgery and throughout the recovery. We compared the BSEEG scores of C57BL/6J young (2–3 months old) with aged (18–19 months old) male mice for quantitative evaluation of POD-like states. Postoperatively, both groups displayed increased BSEEG scores and a loss of regular diurnal changes in BSEEG scores. In young mice, BSEEG scores and regular diurnal changes recovered relatively quickly to baseline by postoperative day (PO-Day) 3. Conversely, aged mice exhibited prolonged increases in postoperative BSEEG scores and it reached steady states only after PO-Day 8. This study suggests that the BSEEG method can be utilized as a quantitative measure of POD and assess the effect of aging on recovery from POD in the preclinical model.

Keywords: Aging, Bispectral electroencephalography, Head-mount implantation surgery, Postoperative delirium

Delirium is an acute brain failure characterized by a sudden onset of fluctuating mental symptoms with impaired consciousness (1). It has been directly linked to poor outcomes, such as high mortality, postdischarge institutionalization, and cognitive decline (2). Postoperative delirium (POD) is the most common postoperative complication in this demographic but despite its severe impact, its pathological mechanism is still not well understood (3). Diagnosis of delirium primarily relies on clinical observation and expert opinion as there are few biological-quantitative monitoring methods (1). As a result, delirium remains undiagnosed in roughly half or more clinical cases and thus, there is insufficient research on underlying mechanisms for delirium (4).

Therefore, an urgent need is to develop an approach to detect delirium and objectively quantify its severity. Our group has developed a new approach using a novel bispectral electroencephalogram (BSEEG) method to identify delirium and predict patient outcomes by capturing its brain wave characteristics (5). Unlike conventional EEG, the BSEEG method uses a simplified, lightweight one-channel electroencephalography (EEG) recording. The BSEEG score can be useful for delirium screening and is significantly associated with clinical outcomes, including mortality, hospital stay duration, and postdischarge disposition (6,7). The effectiveness of the BSEEG method has been validated in over 1 000 patients (8).

Following the success of the BSEEG method in the clinical setting, we pivoted to a preclinical study by applying the BSEEG method for lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced mouse model of delirium to lay the groundwork for clarifying delirium pathophysiology with hopes to assist in the development of effective preventions and treatments (9). Because many preclinical studies have shown that in addition to LPS injection, surgical intervention causes systemic inflammation as well as neuroinflammation, subsequently inducing a delirium-like state (10,11).

The next step to enhance the utility of the BSEEG method in preclinical study is to validate the effectiveness of the approach on animal models of POD-like states. It is particularly beneficial as continuous monitoring for quantifying POD-like states in mice has hardly been reported. One study monitored aged mice in an ICU-like condition, noting that their EEG and circadian changes, characterized by frequent arousals and slow wave ratios, were similar to those seen in delirious ICU patients (12). However, no study has yet monitored long postoperative periods including diurnal changes with EEG comparing young and aged mice. As several studies reported the possible role of circadian rhythm in delirium pathophysiology, it is of interest to assess diurnal change using the BSEEG score (9). Thus, we applied the BSEEG method following EEG head-mount surgery to continuously monitor and quantify BSEEG response to surgical insults during the postsurgical recovery period across the 2 age groups.

Methods and Materials

Animals and Housing

All male C57BL/6J mice (young: 2–3 months, aged: 18–19 months) were purchased from Jackson Laboratory and housed at Stanford University’s animal facility. Preoperatively, 4–5 mice shared a cage with free access to food and water. Postoperatively, each mouse was housed individually. The environment was maintained in a 12:12 hour light-dark cycle, a temperature of 20–26°C, and humidity of 30%–60%. The experiments followed a protocol approved by Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC), known as Stanford’s Administrative Panel on Laboratory Animal Care (APLAC), accredited by Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC).

Experimental Procedure

Experiment schedule

EEG recording began immediately following EEG head-mount implantation surgery, spanning postoperative day (PO-Day) 0 to 14, with PO-Day 0 denoted as the surgery day. BSEEG scores were then compared between young (n = 12) and aged mice (n = 15; Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the experiment and the postoperative BSEEG scores on each young mouse. A, Schematic diagram of the experiment: EEG recording began immediately after the EEG head-mount implantation surgery. After that, raw EEG data were digitally converted into the ratio of 3 to 10 Hz power spectral density and calculated BSEEG scores. B, The postoperative BSEEG scores on each young mouse: BSEEG scores were plotted on the y-axis, whereas the postoperative times were displayed on the x-axis. Daytime/night was shown as yellow/gray lines on the background of the x-axis. C, The postoperative BSEEG scores on each aged mouse: BSEEG scores were plotted on the y-axis, whereas the postoperative times were displayed on the x-axis. Daytime/night was shown as yellow/gray lines on the background of the x-axis. BSEEG = bispectral electroencephalogram; EEG = electroencephalography.

EEG electrode head-mount placement surgery

EEG head-mount implantation surgery was conducted as reported in previous studies (9,13,14). Under isoflurane (1%–3% inhalation) anesthesia, the skull was exposed and the head-mount was placed on the midline, with its anterior holes at 2 mm anterior to bregma and its posterior holes at 2 mm anterior to lambda ±2 mm. Four holes were bored into the skull with a 23-gauge needle through the head-mount holes and 4 screws were inserted into holes. Finally, the head mount was fixed with dental cement. Mice received postoperative analgesia via meloxicam 5 mg/kg in subcutaneous injection and subsequently connected to an EEG system. EEG was recorded from the right frontal cortex with the right anterior screw (EEG2) and the right parietal cortex with the right posterior screw (EEG1). The left anterior screw at left frontal cortex served as the ground, and the left posterior screw at the left parietal cortex served as the reference. We used signals from EEG2 because EEG2 is documented in previous studies as more sensitive than EEG1 (9).

EEG signal processing for BSEEG scores

Raw EEG was digitally converted into power spectral density to calculate BSEEG scores. We used the Sirenia software to record and export raw data into an EDF file and it was processed through our web-based tool (https://sleephr.jp/gen/mice7days/) to calculate BSEEG scores. Our web-based tool is an automatic calculator for the BSEEG score, the ratio of 3 to 10 Hz power.

BSEEG score

In this study, we defined a BSEEG score as the average BSEEG score for every 12 hours (7 am to 7 pm) to highlight regular diurnal changes seen along the circadian rhythm reported in our previous study (9).

Standardized BSEEG score

To highlight the differences in the BSEEG scores compared to the postoperative steady state, we defined the standardized BSEEG (sBSEEG) score as the difference between daytime/night BSEEG scores on each PO-Day and daytime BSEEG scores on PO-Day 14. The daytime BSEEG score on PO-Day 14 was defined as sBSEEG score = 0. We adopted this approach because the baseline EEG cannot be recorded before head-mount surgery and because, as in general animal postoperative care, animals are fully recovered from 7 to 14 days (15). Therefore, most mice were estimated to fully recover and reach a steady state in their BSEEG scores on PO-Day 14.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism version 10. Error bars were shown as means ± standard error of the means (mean ± SEM). p < .05 was marked with an asterisk and considered statistically significant. Shapiro–Wilk test assessed data normality. Differences between the young and aged groups were analyzed with Welch’s t test, where data were normally distributed, or with Mann–Whitney U test, where data were not normally distributed. Daytime sBSEEG score differences from PO-Day 1–13 and PO-Day 14 were analyzed with a paired t test, where data were normally distributed, or with Wilcoxon signed-rank test, where data were not normally distributed. Mice that died or showed recording errors, such as abnormal waves or persistent BSEEG scores above 20, were excluded.

Results

The data presents postoperative BSEEG scores of the young mice (Figure 1B). Most young mice lost diurnal changes for several days postsurgery. A small proportion of mice exhibited drastic increases in BSEEG scores (>10) on PO-Day 1 (Figure 1B, nos. 3, 8). Conversely, the opposite effect was observed as some mice were nearly unaffected in BSEEG scores on PO-Day 1 (Figure 1B, nos. 5, 12). Notably, the daytime BSEEG scores of most mice stabilized around a BSEEG score of 4 by PO-Day 14 (Figure 1B, nos. 1–9, 11, 12).

The postoperative BSEEG scores for aged mice indicated greater variation compared to young mice (Figure 1C). Only a small number of aged mice exhibited regular diurnal variation patterns (Figure 1C, nos. 3, 9) where BSEEG scores are higher at daytime, as commonly seen in young mice around PO-Day 14 (Figure 1B). However, a majority of the cohort displayed no consistent pattern in the BSEEG scores, even around PO-Day 14. They were either flat (Figure 1C, nos. 1, 5, 6, 12, 13, 14), reversed as such that diurnal change where BSEEG scores were higher at night (Figure 1C, nos. 10, 15), or irregular (Figure 1C, nos. 2, 4, 7, 8, 11). Some of the mice showed drastic increases in BSEEG scores (>10) on PO-Day 1 to 3 (Figure 1C, nos. 4, 6, 10, 11). The BSEEG scores on many mice showed recovery from the increase in BSEEG score and the loss of diurnal changes due to the effect of surgery. However, in contrast to young mice, it is remarkable that the BSEEG score patterns observed around PO-Day 14 in aged mice remained diverse depending on each mouse.

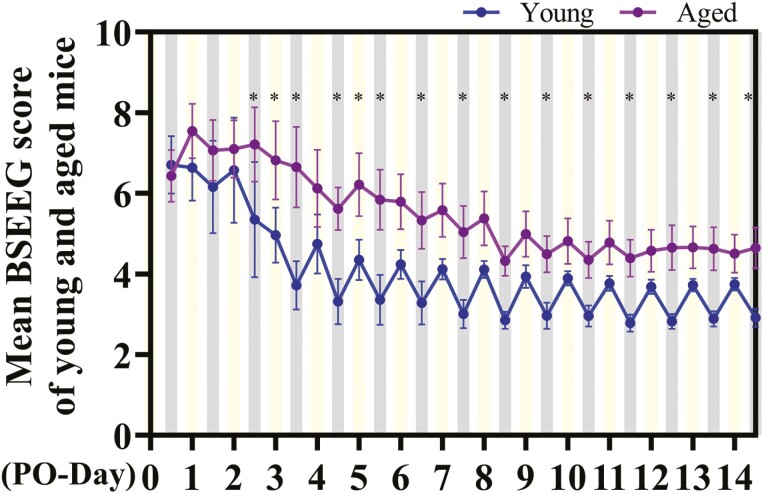

We then compared the mean BSEEG scores on the young and aged mice (Figure 2). The mean BSEEG scores of young mice regained regular diurnal changes early by PO-Day 3 and reached steady state ranging between BSEEG scores of 2.5 and 4 (Figure 2). In contrast, the mean BSEEG scores of aged mice did not regain clear diurnal changes and reached steady state with slight fluctuation around BSEEG scores of 4.5 to 5 later by PO-Day 9 (Figure 2). Aged mice also had significantly higher average BSEEG scores at night than young mice during the whole period, except from PO-Day 0 to 2 (Figure 2, Supplementary Figure 1).

Figure 2.

The postoperative mean BSEEG scores comparing young and aged mice. BSEEG scores were plotted on the y-axis, whereas the recording times were displayed on the x-axis. Daytime/night was shown as yellow/gray lines on the background of the x-axis. All error bars were shown as means ± standard error of the means (mean ± SEM). p < .05 was marked with an asterisk (*) and considered statistically significant. BSEEG = bispectral electroencephalogram.

Because the steady-state levels of the mean BSEEG scores were different between young and aged mice, we compared the sBSEEG scores between young and aged mice (Figure 3, Supplementary Figure 2). In the young cohort, there were statistically significant differences in the sBSEEG scores on the daytime of PO-Day 1 to 3 compared with that of PO-Day 14, and there was no statistical significance after the daytime of PO-Day 3 compared with that of PO-Day 14 (Figure 3A, Supplementary Figure 3). On the other hand, in aged mice, there were statistical significances from the daytime of PO-Day 1 to 7 when compared with PO-Day 14, and the daytime mean sBSEEG scores showed no statistical significance after the daytime of PO-Day 7 when compared with PO-Day 14, except from PO-Day 11 (Figure 3B, Supplementary Figure 4). The major difference between young and aged mice was the more prolonged duration of the sBSEEG score elevation in aged mice (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The postoperative mean sBSEEG scores. A, The postoperative mean sBSEEG scores on young mice comparing daytime sBSEEG scores in PO-Day 0 to 13 with PO-Day 14: sBSEEG scores were plotted on the y-axis, whereas the recording times were displayed on the x-axis. Daytime/night was shown as yellow/gray lines on the background of the x-axis. All error bars were shown as means ± standard error of the means (mean ± SEM). p < .05 was marked with an asterisk (*) and considered statistically significant. B, The postoperative mean sBSEEG scores on aged mice comparing daytime sBSEEG scores in PO-Day 0 to 13 with PO-Day 14: sBSEEG scores were plotted on the y-axis, whereas the recording times were displayed on the x-axis. Daytime/night was shown as yellow/gray lines on the background of the x-axis. All error bars were shown as means ± standard error of the means (mean ± SEM). p < .05 was marked with an asterisk (*) and considered statistically significant. PO = post-operative; sBSEEG = standardized bispectral electroencephalogram.

Discussion

We showed that the BSEEG method, effective in the detection of delirium within the clinical setting, is also capable of quantifying brain wave responses postsurgery among young and aged mice. In young mice, the surgical impact on BSEEG scores was relatively short as many young mice resumed regular diurnal variation soon after surgery and BSEEG scores returned to baseline levels. In aged mice, however, the same recovery took notably longer and postsurgery diurnal variation in BSEEG scores was unstable and varied by individual.

This result aligns well with older adults being at higher risk of developing delirium. Also, the lack of clear diurnal change among aged mice suggests that loss of circadian rhythm could be a marker of loss of brain resilience, potentially predating in the aging brain before the development of delirium. Circadian rhythm is a known major determinant of sleep timing and structure (16). Older adults tend to sleep and wake earlier, reporting more advanced sleep-wake phase disorders than young adults (16). One study reported that circadian rhythm-related factors, like decreased REM sleep, lower melatonin levels, and higher cortisol levels, independently increased delirium risk in the ICU (17,18). Our data suggests that the BSEEG method could detect vulnerabilities in aged brains at baseline predisposing to delirium. Such assessment can be used before surgery and is expected to evaluate the potential preventive or therapeutic effects of future interventions on delirium.

The incidence of POD depends on age and the type of surgery the patient undergoes (19). Under different conditions, the course quantified by the BSEEG method may differ. While conventional methods need frequent behavioral testing at multiple time points to evaluate delirium-like states in mice over time, the BSEEG method allows continuous evaluation with quantitative measurement without manipulating mice repeatedly. Thus, the BSEEG method offers advantages in providing detailed, objective chronological information on the delirium-like state under various conditions, including age, sex, surgical type, or drug administration.

The BSEEG data from our study align with the previous literature on the postoperative model. Some studies reported that cognitive impairment and glial activation in young adult animals typically occur between PO-Day 1 and 3 but not at PO-Day 7 (20), whereas those changes can be observed even at PO-Day 7 in aged animals (21). Moreover, one study reported that anesthesia and surgery impair the blood–brain barrier and cognitive function in aged mice more than in adult mice (22). Microglia release more cytokines in aged animal brains than in young following external insults, suggesting their role in the pathogenesis of cognitive decline in aged animals (23).

We acknowledge several limitations in this study. First, we did not investigate behavior or tissue. Second, we did not investigate the individual differences in vulnerability. Individual differences in vulnerability to exogenous insults, potentially rooted in the core pathophysiological mechanisms of delirium and its subtypes, warrant further study. Third, our study included only male mice. The reason is that including females complicates age comparisons due to changing female hormone levels with age. Finally, inserting the screw directly into the brain causes some degree of direct brain injury. As direct brain damage can cause acute brain dysfunction beyond neuroinflammation alone, including energy deprivation and metabolic disturbances (24), the head-mount implantation surgery POD model in this study is not necessarily generalizable to delirium from various causes other than neurosurgery cases.

This study is the first to apply the BSEEG method to POD in animal experiments. We successfully detected the age differences of POD vulnerability in mice quantitatively and chronologically. This study further validated the usefulness of the BSEEG method with our approach, applying it from clinical studies to a preclinical model to explore the neurobiology of delirium. We hope to see this approach used more widely in preclinical delirium studies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the support from Stanford University School of Medicine Veterinary Service Center (VSC).

Contributor Information

Tsuyoshi Nishiguchi, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Stanford University School of Medicine, Palo Alto, California, USA; Faculty of Medicine, Department of Neuropsychiatry, Tottori University, Yonago, Tottori, Japan.

Kazuki Shibata, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Stanford University School of Medicine, Palo Alto, California, USA; Sumitomo Pharma Co. Ltd., Osaka, Osaka, Japan.

Kyosuke Yamanishi, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Stanford University School of Medicine, Palo Alto, California, USA; Department of Neuropsychiatry, School of Medicine, Hyogo Medical University, Nishinomiya, Hyogo, Japan.

Mia Nicole Dittrich, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Stanford University School of Medicine, Palo Alto, California, USA.

Noah Yuki Islam, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Stanford University School of Medicine, Palo Alto, California, USA.

Shivani Patel, Department of Molecular and Cell Biology, University of California, Berkeley, California, USA.

Nathan James Phuong, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Stanford University School of Medicine, Palo Alto, California, USA.

Pedro S Marra, Department of Psychiatry, University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine, Iowa City, Iowa, USA.

Johnny R Malicoat, Department of Psychiatry, University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine, Iowa City, Iowa, USA.

Tomoteru Seki, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Stanford University School of Medicine, Palo Alto, California, USA; Department of Psychiatry, Tokyo Medical University, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo, Japan.

Yoshitaka Nishizawa, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Stanford University School of Medicine, Palo Alto, California, USA; Faculty of Medicine, Department of Neuropsychiatry, Osaka Medical and Pharmaceutical University, Takatsuki, Osaka, Japan.

Takehiko Yamanashi, Faculty of Medicine, Department of Neuropsychiatry, Tottori University, Yonago, Tottori, Japan.

Masaaki Iwata, Faculty of Medicine, Department of Neuropsychiatry, Tottori University, Yonago, Tottori, Japan.

Gen Shinozaki, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Stanford University School of Medicine, Palo Alto, California, USA.

Gustavo Duque, (Biological Sciences Section).

Funding

No funding source.

Conflict of Interest

G.S. has pending patents as follows: “Non-invasive device for predicting and screening delirium,” PCT application no. PCT/US2016/064937 and US provisional patent no. 62/263,325; “Prediction of patient outcomes with a novel electroencephalography device,” US provisional patent no. 62/829,411. “DEVICES, SYSTEMS, AND METHOD FOR QUANTIFYING NEURO-INFLAMMATION,” United States Patent Application No. 63/124,524. All other authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1. Setters B, Solberg LM.. Delirium. Prim Care. 2017;44(3):541–559. 10.1016/j.pop.2017.04.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Witlox J, Eurelings LS, de Jonghe JF, Kalisvaart KJ, Eikelenboom P, van Gool WA.. Delirium in elderly patients and the risk of postdischarge mortality, institutionalization, and dementia: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2010;304(4):443–451. 10.1001/jama.2010.1013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Adults AGSEPoPDiO. American Geriatrics Society abstracted clinical practice guideline for postoperative delirium in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(1):142–150. 10.1111/jgs.13281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Spronk PE, Riekerk B, Hofhuis J, Rommes JH.. Occurrence of delirium is severely underestimated in the ICU during daily care. Intensive Care Med. 2009;35(7):1276–1280. 10.1007/s00134-009-1466-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Shinozaki G, Chan AC, Sparr NA, et al. Delirium detection by a novel bispectral electroencephalography device in general hospital. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2018;72(12):856–863. 10.1111/pcn.12783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Shinozaki G, Bormann NL, Chan AC, et al. Identification of high mortality risk patients and prediction of outcomes in delirium by bispectral EEG. J Clin Psychiatry. 2019;80(5):e1–e8. 10.4088/JCP.19m12749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Yamanashi T, Crutchley KJ, Wahba NE, et al. Evaluation of point-of-care thumb-size bispectral electroencephalography device to quantify delirium severity and predict mortality. Br J Psychiatry. 2021;Aug 2:1–8. 10.1192/bjp.2021.101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nishizawa Y, Yamanashi T, Saito T, et al. Bispectral EEG (BSEEG) Algorithm captures high mortality risk among 1,077 patients: its relationship to delirium motor subtype. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2023;31:704–715. 10.1016/j.jagp.2023.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yamanashi T, Malicoat JR, Steffen KT, et al. Bispectral EEG (BSEEG) quantifying neuro-inflammation in mice induced by systemic inflammation: a potential mouse model of delirium. J Psychiatr Res. 2021;133:205–211. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.12.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yang T, Velagapudi R, Terrando N.. Neuroinflammation after surgery: from mechanisms to therapeutic targets. Nat Immunol. 2020;21(11):1319–1326. 10.1038/s41590-020-00812-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Field RH, Gossen A, Cunningham C.. Prior pathology in the basal forebrain cholinergic system predisposes to inflammation-induced working memory deficits: reconciling inflammatory and cholinergic hypotheses of delirium. J Neurosci. 2012;32(18):6288–6294. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4673-11.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dulko E, Jedrusiak M, Osuru HP, et al. Sleep fragmentation, electroencephalographic slowing, and circadian disarray in a mouse model for intensive care unit delirium. Anesth Analg. 2023;137(1):209–220. 10.1213/ANE.0000000000006524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Buchanan GF, Murray NM, Hajek MA, Richerson GB.. Serotonin neurones have anti-convulsant effects and reduce seizure-induced mortality. J Physiol. 2014;592(19):4395–4410. 10.1113/jphysiol.2014.277574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Purnell BS, Hajek MA, Buchanan GF.. Time-of-day influences on respiratory sequelae following maximal electroshock-induced seizures in mice. J Neurophysiol. 2017;118(5):2592–2600. 10.1152/jn.00039.2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Oliveira LMO, Dimitrov D. Surgical techniques for chronic implantation of microwire arrays in rodents and primates. In: Nicolelis MAL, ed. Methods for Neural Ensemble Recordings. 2nd ed. Chapter 2. CRC Press/Taylor & Francis; 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Duffy JF, Zitting KM, Chinoy ED.. Aging and circadian rhythms. Sleep Med Clin. 2015;10(4):423–434. 10.1016/j.jsmc.2015.08.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sun T, Sun Y, Huang X, et al. Sleep and circadian rhythm disturbances in intensive care unit (ICU)-acquired delirium: a Case-Control Study. J Int Med Res. 2021;49(3):300060521990502. 10.1177/0300060521990502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Logan RW, McClung CA.. Rhythms of life: circadian disruption and brain disorders across the lifespan. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2019;20(1):49–65. 10.1038/s41583-018-0088-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Whitlock EL, Vannucci A, Avidan MS.. Postoperative delirium. Minerva Anestesiol. 2011;77(4):448–456. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wan Y, Xu J, Ma D, Zeng Y, Cibelli M, Maze M.. Postoperative impairment of cognitive function in rats: a possible role for cytokine-mediated inflammation in the hippocampus. Anesthesiology. 2007;106(3):436–443. 10.1097/00000542-200703000-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. He J, Liu T, Li Y, et al. JNK inhibition alleviates delayed neurocognitive recovery after surgery by limiting microglia pyroptosis. Int Immunopharmacol. 2021;99:107962. 10.1016/j.intimp.2021.107962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Yang S, Gu C, Mandeville ET, et al. Anesthesia and surgery impair blood-brain barrier and cognitive function in mice. Front Immunol. 2017;8:902. 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Dilger RN, Johnson RW.. Aging, microglial cell priming, and the discordant central inflammatory response to signals from the peripheral immune system. J Leukoc Biol. 2008;84(4):932–939. 10.1189/jlb.0208108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Maclullich AM, Ferguson KJ, Miller T, de Rooij SE, Cunningham C.. Unravelling the pathophysiology of delirium: a focus on the role of aberrant stress responses. J Psychosom Res. 2008;65(3):229–238. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2008.05.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.