Abstract

Background:

Academic family medicine (FM) physicians aim to balance competing needs of providing clinical care with nonclinical duties of program administration, formal education, and scholarly activity. FM residency is unique in its scope of practice, clinical settings, and training priorities, which may differ between university-based and community-based programs. In both types of programs, these competing needs are a source of faculty dissatisfaction and burnout. We performed this study to explore the allocation of nonclinical administrative full-time equivalents (FTE) for FM residency core faculty members.

Results:

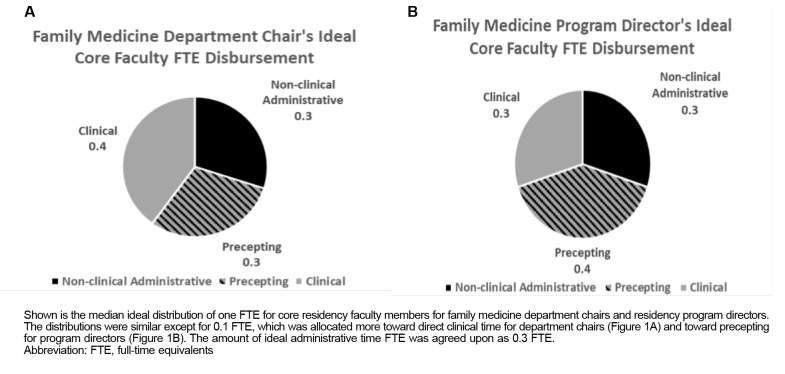

Reported nonclinical administrative FTE time allocation is equivalent between university/medical school-based and community-based programs. The ideal proportion of FTE distribution identified by DCs had greater amounts of direct clinical care compared to greater emphasis on precepting time identified by PDs. DCs and PDs agreed that administrative time should be used for advising residents, curriculum development and delivery, and evaluation of resident performance. Barriers to allocating additional administrative time for DCs included loss of revenue and pressure by hospital-level leadership. PDs responded that the need for clinical supervision of residents was most significant.

Methods:

We performed our research through a cross-sectional survey of FM department chairs (DC) and residency program directors (PD) conducted by the Council of Academic Family Medicine Educational Research Alliance. We used descriptive statistics to characterize the data and Pearson’s χ2 tests to evaluate bivariate relationships.

Conclusions:

DCs and PDs offer a similar ideal picture of core responsibilities, though subtle differences remain. These differences should be considered for the next revision of the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education minimum program standards to best meet the needs of all FM programs.

Keywords: administration, core faculty, family medicine, graduate medical education, residency

INTRODUCTION

The three foundational pillars of clinical care, education, and scholarship provide the base for family medicine residency training in the United States.1 Core faculty provide direct patient care (clinical time), clinical teaching and supervision of residents (precepting time), and participation in nonclinical activities related to resident education, scholarship, and program administration (nonclinical administrative time).2 Both nonclinical and clinical activities benefit the academic mission of family medicine residency programs by allowing core faculty to model participation in all three pillars of clinical care, education, and scholarship.

Nonclinical activities are most effective when core residency faculty have protected time (ie, time allocated for a specific purpose without distractions or interruptions) and clearly delineated responsibilities.3, 4 Several changes in the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) common program requirements reduced overall protections for time outside of direct patient care for program directors and core faculty since 2019, when the pre-2019 protections—at least 40–60% of time outside of direct patient care, depending on program size—were reduced to 10% of time outside of direct patient care. (Through extensive advocacy by national family medicine leadership, pre-2019 protections were recently added to the family medicine program requirements effective 2024.)5 The 2019 reduction, however, led the American Board of Family Medicine (ABFM) to study the impact of that policy change. The ABFM investigators found that 75% of survey respondents reported significant adverse impacts, including increased clinical requirements and pressure to complete more patient visits while reducing the time available to address program administration, education, and scholarship.6 Program morale and quality of residency education were also negatively impacted.6 Researchers of a previous study suggested that the average disbursement of full-time equivalents (FTE) for nonclinical work was 0.26 FTE; program administration, resident feedback/evaluation, and didactics made up most of that time.7 Those researchers additionally found that members in all work settings identified the balance of workload, administration, and competing priorities as the biggest challenge to being productive across all three pillars.7 Many respondents reported that clinical demands were impinging on academic and education time.7 This perceived workload is associated with an increased desire to leave faculty positions. 3, 8

Unlike other specialties, family medicine residency training primarily occurs in community-based programs.9 Community-based programs have less infrastructural and support staff to train family medicine residents, requiring core faculty to perform additional administrative duties.10 We sought to describe the allocation, disbursement, and use of nonclinical administrative FTE for family medicine residency core faculty at academic-based and community-based residency programs, as well as perceived barriers to allocation of nonclinical FTE. This research aimed to inform accreditation policy requirements on the adequate allocation of nonclinical administrative time to best support residency program needs.

METHODS

Study Design and Data Collection

Using the seven-step approach to survey design by Artino et al 11, we developed questions by reviewing the literature for validated reporting within our sample population, consulting with experts, validating survey items with experts, conducting cognitive interviews, and pilot testing the survey questions.11 The Council of Academic Family Medicine Educational Research Alliance (CERA) Steering Committee evaluated our questions for consistency with the overall subproject aim, readability, and existing evidence of reliability and validity. Family medicine educators outside of the target population pretested the questions. A CERA national omnibus survey of family medicine department chairs and program directors in 2023 included our questions along with additional questions on other content areas. The methodology of the CERA department chair and program director survey has previously been described.12 Appendix A details the final standardized demographic and developed content questions on nonclinical administrative time for department chairs and program directors. Data were collected from department chairs opening August 8 and closing September 15, 2023, and program directors opening September 26 and closing October 30, 2023.

Our survey questions were distributed to all US family medicine department chairs as identified by the Association of Departments of Family Medicine, and ACGME-accredited US family medicine program directors as identified by the Association of Family Medicine Residency Directors. We chose these groups because department chairs and program directors actively participate in allocating nonclinical administrative FTE for academic-based and community-based residency programs. We excluded data from Canadian department chairs because the accreditation and governing rules are significantly different from those in the United States. Email invitations to participate were delivered using the survey software SurveyMonkey (SurveyMonkey, Inc). After the initial email invitation, nonrespondents received two follow-up emails on a weekly basis to encourage them to participate. Nonrespondents then received a third reminder 2 days before the survey closed.

At the time of the survey, the list of department chairs had 230 names; three were no longer department chairs, or their emails were undeliverable. The CERA Steering Committee emailed the department chair survey to a sample size of 227. At the time of the survey, the list of program directors had 754 names; 10 had previously opted out of surveys, or their emails were undeliverable. The CERA Steering Committee emailed the program directors survey to a sample size of 744. The program director survey contained a qualifying question to remove programs that had not yet graduated three resident classes; based on that question, 29 respondents were omitted. Department chairs and program directors completing the survey were not required to respond to all the items.

Statistical Analyses

We used descriptive statistics to describe the allocation, the ideal state, and the person allocating nonclinical FTE for family medicine residency core faculty. We analyzed data using R statistics software version 4.2.2 (The R Foundation). To examine the associations among allocated nonclinical, administrative FTE, the person allocating FTE, perceptions, and program characteristics, we computed bivariate statistics. To evaluate bivariate relationships, we used Pearson’s χ2 tests of independence, employing a level of statistical significance set at α=0.05.

Our intention for this study was to describe the allocation and disbursement of FTE separately from the usage and barriers from both the department chair and program director surveys.

Ethical Considerations

The American Academy of Family Physicians Institutional Review Board approved the CERA surveys before dissemination for the department chair survey in August 2023 and for the program director survey in September 2023.

RESULTS

Survey Demographic Data

The overall response rates for the department chair and program director surveys were 50.2% (114/227) and 37.9% (271/715), respectively. Appendix B displays the descriptive characteristics of responding department chairs and program directors. Department chairs were more likely to be associated with medical school-based (51.9%) than community-based residency programs (33.0%), and a majority served communities with more than 500,000 individuals (53.4%). In comparison, program directors were more likely to be associated with community-based residency programs (81.9%) than with university-based residency programs (16.2%), and a majority served communities with fewer than 500,000 individuals (71.5%).

Allocation of Nonclinical Administrative FTE

Family medicine department chairs and program directors responded that the median allocated amount of FTE designated nonclinical administrative time was 0.2–0.29 FTE (IQR: 0.1–0.39 FTE) or up to 1.5 days per week. Results of the department chair survey, which encompassed primarily medical school-based residency programs, indicated that in 60.8% of residency programs, the department chair is primarily responsible for allocating and distributing FTE for residency core faculty, followed by residency program directors in 28.9% of residencies. In contrast, the program director survey results, which encompassed primarily community-based residency programs, indicated that in 53.4% of residency programs, the program director is the primary person allocating, followed by department chairs in 20.3% of residencies. The results of the department chair survey did not show an association between the type of residency program and the person allocating FTE (Table 1). However, results of the program director survey showed a significant association (P<.001) between program director allocation for community-based and department chair for university-based programs. In the results of the department chair survey, the number of faculty did not affect FTE allocation (data not shown). This factor could not be discerned in the program director survey because the number of faculty in the residency program was not asked in the CERA standardized demographic information.

Table 1. Differences Between Entity Allocating FTE and Type of Residency Program.

|

Department c hair survey |

Program d irector survey |

|||||

|

Entity allocating FTE |

Medical school-based, n (%) |

Community-based, n (%) |

P value |

University-based, n (%) |

Community-based, n (%) |

P value |

|

Department chairs Program directors Other |

35 (66.0) 14 (26.4) 4 (7.5) |

16 (53.3) 10 (33.3) 4 (13.3) |

.476 |

30 (69.8) 6 (14.0) 7 (16.3) |

23 (10.8) 133 (62.7) 56 (26.4) |

<.001 |

Abbreviation: FTE, full-time equivalents

Ideal Proportions for Full-Time FTE Disbursement

Both family medicine department chairs and program directors responded that 0.3 FTE is the ideal nonclinical administrative time (Figure 1). Department chairs and program directors had slight differences in direct clinical time and precepting time allocation. Department chairs allocated 0.4 FTE to direct clinical time and 0.3 FTE to precepting time, whereas program directors allocated 0.3 FTE to direct clinical time and 0.4 FTE to precepting time.

Figure 1 . Family Medicine Department Chairs’ and Program Directors’ Ideal Disbursement of FTE for Residency Core Faculty.

Department Chair and Program Director Perceptions of Nonclinical Administrative FTE

Department chairs allocated less FTE for nonclinical administrative time than program directors (Table 2). Specifically, department chairs had higher proportions of faculty allocated 0 to 0.19 FTE for administrative purposes, whereas program directors had higher proportions of faculty with greater than 0.4 FTE (P=.005) allocated. We observed the same pattern in perceptions of the ideal amount for administrative tasks, where department chairs would ideally allocate lower amounts of nonclinical administrative FTE compared to program directors (P<.001).

Table 2. Family Medicine Department Chair and Program Director Perceptions of Nonclinical Administrative Time.

|

Department chairs, n (%) |

Program directors, n (%) |

P value |

|

|

Allocated nonclinical administrative FTE 0–0.19 0.20–0.29 0.30–0.39 >0.4 |

— 34 (36.2) 33 (35.1) 21 (22.3) 6 (6.4) |

— 63 (23.4) 84 (31.2) 67 (24.9) 55 (20.4) |

.005 |

|

Ideal nonclinical administrative FTE 0–0.19 0.20–0.29 0.30–0.39 >0.4 |

— 21 (22.3) 43 (25.7) 19 (20.2) 11 (11.8) |

— 27 (10.0) 95 (18.6) 82 (30.5) 65 (24.2) |

<.001 |

|

Allocated compared to ideal nonclinical administrative FTE Allocated < ideal Allocated = ideal Allocated > ideal |

— 28 (29.7) 49 (52.1) 17 (18.2) |

— 109 (40.6) 117 (43.5) 43 (15.9) |

.178 |

|

Allocated ≥ STFM workgroup recommendations 2 No Yes |

— 67 (71.3) 27 (28.7) |

— 147 (55.6) 122 (45.3) |

.005 |

|

Importance of protecting nonclinical administrative FTE Unimportant Important |

— 25 (26.3) 70 (73.7) |

— 59 (22.2) 207 (77.8) |

.413 |

Abbreviations: FTE, full-time equivalents; STFM, Society of Teachers of Family Medicine

We then assessed the ideal disbursement of FTE by department chairs and program directors. In the department chair survey, 29.8% of academic family medicine department’s residency programs allocated less nonclinical administrative FTE than they believed ideal. Meanwhile, 52.1% of academic family medicine departments’ residency programs allocated what they responded was ideal, and 18.2% allocated more nonclinical administrative FTE than they believed ideal. Similarly, in the program director survey, 40.6% of residency programs allocated less nonclinical administrative FTE than the ideal. Meanwhile, 43.5% of residency programs allocated what they responded was ideal, and 15.9% allocated more nonclinical administrative FTE than the ideal. Only 28.7% of academic family medicine department’s residency programs and 44.7% of community residency programs allocated the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine (STFM) work group-recommended amount of nonclinical administrative FTE of 0.3. 2

Regarding the importance of protecting nonclinical administrative time (ie, allocating time for a specific purpose without distractions or interruptions) for core residency faculty, 26.3% of department chairs and 22% of program directors felt that doing so is not important. Meanwhile, 73.7% of department chairs and 78% of program directors felt that protecting nonclinical administrative time for core faculty is important.

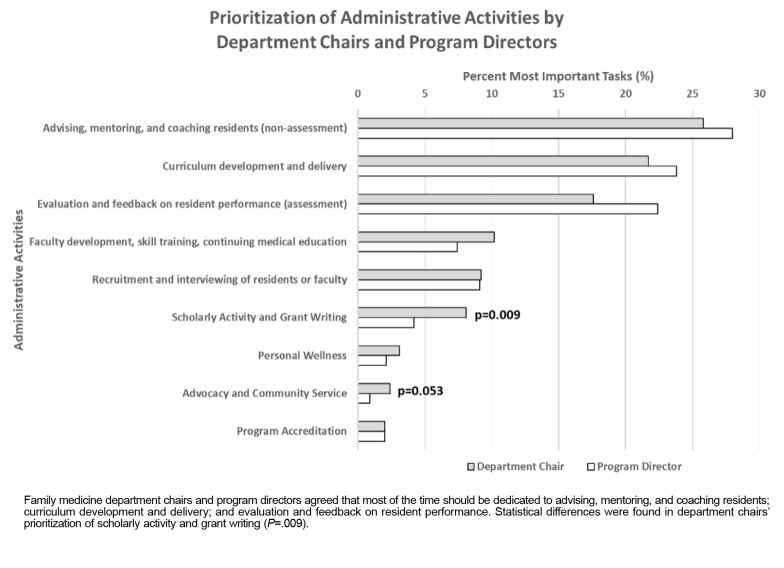

Perceived Beneficial Administrative Tasks

We found a substantial concordance between department chairs and program directors on prioritizing nonclinical administrative tasks (Figure 2; Appendix C). The three most common tasks chosen by department chairs and program directors were advising, mentoring, and coaching residents (nonassessment); curriculum development and delivery; and evaluation and feedback on resident performance (assessment). The three least commonly chosen tasks for nonclinical administrative time included personal wellness, advocacy and community service, and program accreditation. However, we found a statistically significant difference in department chairs prioritizing scholarly activity (P=.009) and trending toward statistical significance in prioritizing advocacy and community service (P=.053) more highly compared to program directors.

Figure 2 . Family Medicine Department Chair and Program Director Prioritization of Administrative Activities.

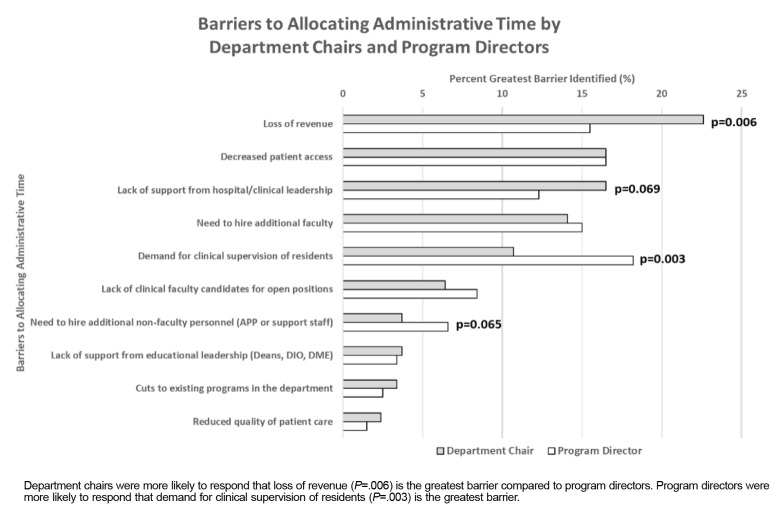

Barriers to Allocating Additional Nonclinical Administrative FTE

We identified substantial concordance regarding the barriers to allocating additional nonclinical administrative FTE between department chairs and program directors, with few exceptions (Figure 3; Appendix D). The most common barrier reported by department chairs is a loss of revenue (P=.006), whereas for program directors, it was the need for clinical supervision of residents (P=.003). Decreased patient access was the second highest-ranked barrier for department chairs and program directors. Loss of revenue was the third highest-ranked barrier cited by program directors, and the need for clinical supervision of residents was the fifth highest-ranked barrier for department chairs. Differences, although not statistically significant, also were seen in department chairs responding that a lack of hospital-level leadership support is a significant barrier (P=.069). In contrast, program directors responded that the need to hire additional support staff to allow for additional nonclinical administrative FTE is a significant barrier (P=.065). The lowest-ranked common barriers for department chairs and program directors were cuts to existing programs in the department and reduced quality of patient care.

Figure 3 . Family Medicine Department Chair and Program Director Perceived Barriers to Allocating Additional Administrative Time.

DISCUSSION

Family medicine professional organizations and stakeholders sought significant requirement changes to obtain standardized, protected nonclinical time for core residency faculty.13 Before the latest ACGME updates, an STFM task force published a call-to-arms joint guideline laying out recommendations for protected nonclinical time for all residency faculty.2 This collective advocacy resulted in changes to ACGME Policy II.B.4, which defines the roles and responsibilities of core faculty.14 Specifically, ACGME delineated a two-tier minimum nonclinical time requirement for family medicine residency programs to follow, allocating either 0.4 FTE (programs with 12 or fewer residents) or 0.6 FTE (programs with 13 or more residents) with the intention that core faculty will have a significant role in the instruction, supervision, mentorship, and administration of the residency program.14 Unfortunately, we were unable to study this two-tiered system as an adequate method to allocate FTE because the smallest ordinal number of residents in the program was less than 19 on the CERA standardized demographic question response options (Appendix A).15

Differences in program structure appear to be more impactful than the program’s size.16 Academic-based and community-based family medicine residency programs differ immensely in the scope of practice, clinical settings, and training priorities (ie, added program emphasis on inpatient, outpatient, obstetric, or community medicine).17 This diversity in training necessitates different needs for each program to operate effectively. Academic programs appear to need more time for clinical duties, while community-based programs may need more time for precepting. These different needs are sensible given that department chairs at academic-based residency programs cited revenue loss as the most significant barrier to increasing nonclinical administrative FTE, while program directors at community-based residency programs cited the need for resident clinical supervision as the greatest barrier to increasing nonclinical administrative FTE. Additionally, department chairs have added pressure from hospital-level leadership, while program directors need to hire more support staff to accommodate additional administrative FTE.

Department chairs and program directors agreed that protecting nonclinical administrative time is important. Specifically, core faculty nonclinical administrative time should focus on the following three priorities: (a) advising, mentoring, and coaching residents; (b) curriculum development and delivery; and (c) evaluation and feedback on resident performance. We found a statistically significant increase in department chairs prioritizing core faculty working on scholarly activity and an increased difference trending toward significance in advocacy and community service work for program directors. This discrepancy may stem from the promotion and tenure tracks needed for academic advancement within departments of family medicine, whereas most community-based residency programs do not require promotion and tenure. 18

The ideal breakdowns for FTE disbursement for family medicine residency core faculty that we identified align with previously published studies.7 In the survey of family medicine program directors, 0.17 FTE was used on nonclinical duties, leading to a recommendation of 0.2 FTE as the proposed ideal for nonclinical duties. However, the list of nonclinical activities used to make these calculations was likely incomplete. For example, we found that department chairs and program directors agreed that the most prioritized nonclinical activity for core faculty to perform is advising, mentoring, or coaching residents in a nonassessment fashion. This activity was not included in the previous study and likely requires several hours per week to perform. The 0.3 FTE for nonclinical administrative time identified by department chairs and program directors as ideal may be a more plausible amount to allocate.

Time management and work-life integration are crucial and often difficult for family medicine core faculty.19 Faculty who feel that they have too many duties with patient care and resident supervision also have a greater desire to leave a faculty position.20 Additionally, discordance between the portions of work that provide joy and the amount of time spent in those tasks leads to physician burnout.21 Faculty members have previously identified workload, administrative burden, and competing priorities as their biggest work-related challenges.22 Greater clinical demands compromise nonclinical responsibilities. These feelings can be extrapolated to our data because department chairs were more likely to provide less nonclinical administrative FTE than they believed ideal for creating more clinical and precepting time. Although nonclinical administrative tasks are necessary, clinical needs and revenue generation often overshadow them.

During this study, ACGME changed its requirements for nonclinical FTE following advocacy efforts from many academic family medicine organizations.5 The constant change in requirements on this topic limits the longevity of this evidence for potential use. Similarly, the progressive push toward competency-based medical education within family medicine may change the needs of residency programs to accommodate the inclusion of new assessment and curricular methods to meet the needs of the trainees of tomorrow.23 An additional technicality of the current evidence is the ambiguity regarding what tasks ACGME includes in its definition of nonclinical time. Particularly, programs often consider precepting residents to be an aspect of clinical time. We attempted to limit this confusion by separating precepting as a separate FTE entity. Another limitation of our study was that program directors and department chairs from the same institutions each could respond to the CERA surveys. Due to the anonymity of the survey design, we were unable to assess the frequency and to what extent that factor could alter the data analysis. Because of this obstacle, possible duplication of data entries for the allocation amount and person allocating is likely present, but results on perceptions and perceived barriers are not affected.

Future studies on FTE disbursement would benefit from focusing on core faculty’s needs rather than programs’ needs. The answers to what proportion of time is needed and what is ideal are likely faculty-specific rather than program-specific. More in-depth time and motion study data would be beneficial to determine the ideal time required for individual tasks performed by each core faculty member, recognizing that not all faculty perform the same duties within a residency program. These quantitative measures also would benefit from additional qualitative analysis of the tensions between time management at work, faculty well-being, and residency program needs.

CONCLUSIONS

Preferred FTE disbursement for core faculty differs between academic-based and community-based programs. Academic-based residency programs report a greater demand for direct patient care and scholarly activity, whereas community-based programs report more necessity for resident supervision. The differences found in our study could be used to inform ACGME accreditation processes to meet the needs of residency programs.

References

- 1.Wilson M R. Scholarly activity redefined: balancing the three-legged stool. Ochsner J. 2006;6(1):12–14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Griesbach S, Theobald M, Kolman K. Joint guidelines for protected nonclinical time for faculty in family medicine residency programs. Fam Med. 2021;53(6):443–452. doi: 10.22454/FamMed.2021.506206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pollart S M, Novielli K D, Brubaker L. Time well spent: the association between time and effort allocation and intent to leave among clinical faculty. Acad Med. 2015;90(3):365–371. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Newton W P, Hoekzema G, Magill M, Hughes L. Dedicated time for education is essential to the residency learning environment. J Am Board Fam Med. 2022;35(5):37. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education

- 6.Newton W P, Magill M. The impact of the ACGME’s June 2019 changes in residency requirements. J Am Board Fam Med. 2020;33(6):36. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jarrett J B, Griesbach S, Theobald M, Tiemstra J D, Lick D. Nonclinical time for family medicine residency faculty: national survey results. PRiMER. 2021;5:45. doi: 10.22454/PRiMER.2021.338005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Greenberger S M, Finnell J T, Chang B P. Changes to the ACGME common program requirements and their potential impact on emergency medicine core faculty protected time. AEM Educ Train. 2020;4(3):244–253. doi: 10.1002/aet2.10421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Green L A, Miller W L, Frey J J, Iii The time is now: a plan to redesign family medicine residency education. Fam Med. 2022;54(1):7–15. doi: 10.22454/FamMed.2022.197486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen J G, Saidi A, Rivkees S, Black N P. University- versus community-based residency programs: does the distinction matter? J Grad Med Educ. 2017;9(4):426–429. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-16-00579.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Artino A R, Rochelle La, Dezee J S, Gehlbach K J, H. Developing questionnaires for educational research. Med Teach. 2014;36(6):463–474. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2014.889814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seehusen D A, Mainous A G, Iii, Chessman A W. Creating a centralized infrastructure to facilitate medical education research. Ann Fam Med. 2018;16(3):257–260. doi: 10.1370/afm.2228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Theobald M. STFM advocates for protected nonclinical time for residency faculty. Ann Fam Med. 2019;17(5):467–468. [Google Scholar]

- 14.ACGME program requirements for graduate medical education in family medicine. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. 2023. https://www.acgme.org/globalassets/pfassets/programrequirements/120_familymedicine_2023.pdf https://www.acgme.org/globalassets/pfassets/programrequirements/120_familymedicine_2023.pdf

- 15.CAFM Educational Research Alliance: recurring demographic questions. Society of Teachers of Family Medicine. 2024. www.stfm.org/publicationsresearch/cera/howtoapply/recurringquestions www.stfm.org/publicationsresearch/cera/howtoapply/recurringquestions

- 16.Jattan A, Penner C G, Giesbrecht M. A comparison of teaching opportunities for rural and urban family medicine residents. Med Educ. 2020;54(2):162–170. doi: 10.1111/medu.14015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pollack S W, Andrilla Cha, Peterson L. Rural versus urban family medicine residency scope of training and practice. Fam Med. 2023;55(3):162–170. doi: 10.22454/FamMed.2023.807915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jacobs C K, Everard K M, Cronholm P F. Promotion of clinical educators: a critical need in academic family medicine. Fam Med. 2020;52(9):631–634. doi: 10.22454/FamMed.2020.687091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gragnano A, Simbula S, Miglioretti M. Work-life balance: weighing the importance of work-family and work-health balance. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(3):907–907. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17030907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buck K, Williamson M, Ogbeide S, Norberg B. Family physician burnout and resilience: a cross-sectional analysis. Fam Med. 2019;51(8):657–663. doi: 10.22454/FamMed.2019.424025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ko S S, Guck A, Williamson M, Buck K, Young R. Residency Research Network of Texas Investigators. Family medicine faculty time allocation and burnout: a Residency Research Network of Texas study. J Grad Med Educ. 2020;12(5):620–623. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-19-00930.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shah D T, Williams V N, Thorndyke L E. Restoring faculty vitality in academic medicine when burnout threatens. Acad Med. 2018;93(7):979–984. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Newton W P, Magill M, Barr W, Hoekzema G, Karuppiah S, Stutzman K. Implementing competency based ABFM board eligibility. J Am Board Fam Med. 2023;36(4):703–707. [Google Scholar]