Abstract

Objectives

Determine if the association between posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and substance use (alcohol misuse or smoking tobacco) is mediated/moderated by exercise or volunteering among aging (≥ 40 years) men who have sex with men (MSM), and if this mediation/moderation differs by HIV serostatus.

Methods

Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study data were used. Three datasets with PTSD measured during different time periods (10/1/2017-3/31/2018, 898 men; 4/1/2018-9/30/2018, 890 men; 10/1/2018-3/31/2019, 895 men) were analyzed. Longitudinal mediation analyses estimated the mediation effect of exercise and volunteering on the outcomes.

Results

Nine percent of MSM had evidence of PTSD. There was no statistically significant mediation effect of exercise or volunteering regardless of substance use outcome. The odds of smoking at a future visit among MSM with PTSD were approximately double those of MSM without PTSD. Results did not differ by HIV serostatus.

Discussion

There is a particular need for effective smoking cessation interventions for aging MSM with PTSD.

Keywords: Posttraumatic stress disorder, PTSD, Alcohol misuse, Smoking tobacco, Men who have sex with men, MSM, Aging, USA

Introduction

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a mental health problem that develops after trauma exposure or experiencing a life-threatening event (National Center for PTSD). Men who have sex with men (MSM) have been shown to have a higher prevalence of past traumatic event exposure as compared to heterosexual men, and differential severity of these traumatic events may place trauma-exposed MSM at greater risk for PTSD relative to trauma-exposed heterosexual men (Roberts et al., 2010). Indeed, Tang et al. (2020) demonstrated that worldwide, MSM living with HIV have an estimated 33% prevalence of PTSD, compared to 20% of heterosexual men living with HIV. People living with HIV (PLWH) additionally experience a disproportionate rate of PTSD as compared to the general population (Boarts et al., 2006; McLean & Fitzgerald, 2016). Potential explanations for the elevated rate of PTSD among PLWH include early and repeated trauma exposure over the life course and the HIV diagnosis itself (Martin & Kagee, 2011; McLean & Fitzgerald, 2016; Tang et al., 2020).

Age further complicates the relationship between sexual orientation/gender, HIV status, and PTSD. The prevalence of PTSD is around 1.9% among adult men in the United States (U.S.) (Cloitre et al., 2019), relative to an estimated 13.5% among older MSM living with HIV (Zepf et al., 2020). Midlife and older MSM (aged 40 years and older) have experienced unique societal conditions throughout their life course. The U.S. gay rights movement of the 1960’s-1980’s increased social visibility and encouraged publicly “coming out”, while societal homophobia and the HIV/AIDS epidemic introduced untold stigma and trauma during the same time period (Wight et al., 2012; Meanley et al., 2020). The distinct experiences and stressors that MSM navigate, which in turn may impact their mental health, is consistent with minority stress theory. This theory posits that mental health disparities among sexual minority populations can be attributed to the social stress experienced by sexual minority individuals that is unique to their sexual minority status (e.g., stigma), and in addition to stressors experienced by the general population (Frost & Meyer, 2023). Wight et al. (2012) examined the impact of sexual minority stressors and common aging-related stressors (independence and fiscal concerns) on the mental health of midlife and older MSM, and found that both sexual minority stressors and aging-related stressors had a negative relationship with positive affect and positive relationship with depressive symptoms.

Rates of PTSD along with substance use disorders are estimated to range between 25% and 55% (Bowen et al., 2017), with theory suggesting a potential bidirectional causal relationship between these two disorders (McCauley et al., 2012). The exact direction of this association seems to vary by individual and involve complex factors, but studies have found that most frequently, the development of PTSD temporally precedes that of a substance use disorder, which lends credence to the self-medication theory – that individuals with PTSD use substances to help manage their PTSD symptoms (McCauley et al., 2012). While individuals with PTSD may turn to a range of substances, alcohol misuse and being a tobacco smoker in particular are highly co-prevalent with PTSD (9.8-61.3% prevalence of alcohol misuse among individuals with PTSD [Debell et al., 2014]; 12.0-53.0% prevalence of smoking tobacco among individuals with PTSD [Pericot-Valverde et al., 2018]). Further, PLWH report greater rates of smoking tobacco relative to people without HIV (PWOH) (Johnston et al., 2021); smoking is a leading cause of death for PLWH, and among PLWH adherent to HIV therapies, smoking is estimated to cause greater loss of life than the HIV infection (Reddy et al., 2016). These conditions require special attention given that alcohol misuse, smoking tobacco, and PTSD are associated with greater HIV disease progression in PLWH (Kimerling et al., 1999; Pacella et al., 2012; Hile et al., 2016; Crane et al., 2017).

There are several approaches to treating PTSD, alcohol misuse, and smoking tobacco, including individual psychotherapy, group therapy, and medications (Marques & Formigoni, 2001; Schnurr et al., 2003; Bradley et al., 2005; Imel et al., 2008; Jeffreys et al., 2012; Kahler et al., 2015; Stead et al., 2017; Akbar et al., 2018; Kaplan et al., 2021). Beyond these methods, alternate approaches for addressing alcohol misuse and smoking tobacco have been explored (e.g., exercise and volunteering) that may be integrated into PTSD treatment programs with relative ease.

To start, exercise may be effective at treating PTSD (Hegberg et al., 2019). A study among PLWH found that individuals ranked walking and exercising as more effective for managing HIV-related anxiety – a correlate of PTSD – than other coping strategies such as talking with a healthcare provider, taking anti-anxiety medications, or using alcohol or cigarettes (Kemppainen et al., 2006). In addition to these benefits, exercise may help to reduce alcohol consumption (Manthou et al., 2016) and aid recovery from alcohol misuse (Brown et al., 2009). Exercise can also increase motivation for quitting smoking and encourage cessation behaviors (LaRowe et al., 2023). Evidence suggests that these effects work through exercise limiting craving for alcohol or tobacco that can lead to subsequent alcohol misuse (Gawor et al., 2021) or smoking relapse (Ussher et al., 2014), respectively. These effects likely work through neurobiological pathways relating to the brain’s reward circuit (Lynch et al., 2013).

Volunteering may also be effective at treating PTSD. A volunteering program among U.S. military veterans was associated with reduced PTSD symptoms when measured at program completion vs. initiation (Matthieu et al., 2017). Beyond the effects on PTSD symptoms, volunteering, too, may help to reduce alcohol and tobacco use, but research suggests that this relationship is complex. A German panel study showed that volunteering actually predicted moderate alcohol consumption a year later among adults aged 40 years and older (Pavlova et al., 2019b). On the other hand, a panel study conducted in the United Kingdom found that volunteering reduced the risk of heavy alcohol consumption two years later among adults aged 40-50 years, and reduced pub attendance among adults aged 65-75 years – but only if these older adults were volunteering with a service-oriented organization (Pavlova et al., 2019a). Both panel studies showed that individuals who had ever been a member of a voluntary organization tended to smoke less relative to those who had not (Pavlova et al., 2019a; Pavlova et al., 2019b). In terms of potential mechanisms, volunteering may increase social engagement and social support, and subsequently protect against alcohol misuse and smoking (Pavlova et al., 2019a). Additionally, volunteering may help individuals – especially older adults – to substitute for social roles they may have held earlier in their life (e.g., parent or spouse) (Russell et al., 2019). Volunteering has been shown to reduce depression levels, especially among older adults (Musick & Wilson, 2003), as well as improve psychological well-being, including among PLWH (Piliavin & Siegl, 2007; Samson et al., 2009) – both of which are associated with alcohol misuse (Abraham & Fava, 1999; Phillips-Howard et al., 2010), and smoking tobacco (Fluharty et al., 2017; Lappan et al., 2020).

Given this basis, and the need for more research on factors that mediate or moderate the association between trauma exposure and health outcomes among PLWH (LeGrand et al., 2015), we investigated exercise and volunteering as protective factors to discourage alcohol misuse and being a tobacco smoker among MSM with PTSD. According to the integrated behavioral model, an individual’s behavior is determined by their intention to perform the behavior, as well as knowledge and skills, salience of the behavior, environmental constraints, and habit. Behavioral intention, in turn, is affected by an individual’s attitude, perceived norm, and personal agency (Montaño & Kasprzyk, 2008). Informed by this theoretical model, it is highly plausible that participation in exercise or volunteering activities may impact any number of these upstream factors and discourage alcohol or tobacco use. For example, if an individual begins engaging in exercise, then smoking cessation may become far more salient. A social support network established through volunteering may alter an individual’s attitude towards cutting back on alcohol or tobacco use, and affect an individual’s perceived norm regarding participation in these behaviors. Partaking in exercise or volunteering routines may increase an individual’s self-confidence and personal agency, promoting subsequent attempts to reduce alcohol or tobacco use.

We operationalized our study by determining if the association between PTSD and alcohol misuse or being a tobacco smoker was mediated or moderated by self-motivated (i.e., not part of a prescribed intervention) exercise or volunteering among aging MSM, hypothesizing that there would be a statistically significant protective mediation/moderation effect. We also explored if the mediation/moderation effect differed by HIV serostatus. Exercise and volunteering were chosen as the protective factors of interest because if shown to be effective, it is feasible that aging MSM with PTSD could be encouraged to engage in these behaviors as a component of PTSD treatment approaches.

Methods

Study Sample and Design

The Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study (MACS) is a prospective cohort study of primarily MSM living with or without HIV. Study design and enrollment for the MACS has been previously described (Kaslow et al., 1987; Silvestre et al., 2006), but briefly the MACS began recruiting in 1984 at study centers in Baltimore, Maryland/Washington, DC; Chicago, Illinois; Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania/Columbus, Ohio; and Los Angeles, California. At semiannual visits, data from standardized questionnaires, physical examinations, and biospecimens were collected (Kaslow et al., 1987). The study protocol was approved by each institution’s institutional review board, and participants provided written consent.

This study focused on men enrolled in the MACS Healthy Aging substudy (R01-MD010680, PIs: Plankey & Friedman). This substudy was limited to MACS MSM aged 40 years and older, and was conducted during MACS semiannual visits from April 2, 2016 to April 8, 2019 (MACS visits 65-70) (Egan et al., 2021). For further details on the MACS Healthy Aging substudy study design and enrollment criteria, please refer to Egan et al. (2021). For this present study, the time period was limited to October 1, 2017 through September 30, 2019 (MACS visits 68-71) due to availability of posttraumatic stress symptom data. MACS visit 71 was included so we could examine alcohol misuse and tobacco smoking outcomes prospectively.

For these analyses, we constructed three separate datasets, each with PTSD measured at a different data collection wave (October 1, 2017-March 31, 2018 [MACS visit 68]; April 1, 2018-September 30, 2018 [MACS visit 69]; or October 1, 2018-March 31, 2019 [MACS visit 70]). We took this approach because the mediation models we used were limited to including an exposure measured at a single data collection wave. Each of these three datasets contained the same MACS participants, with the exception of those who were missing data. Figure S1 describes the construction of each of the three datasets, including at which wave the variables were measured. Within each dataset, we excluded men who were missing measures for PTSD, missing measures for the outcome variables over all of follow-up, or missing measures for the mediator variables over all of follow-up.

Exposure: Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

Posttraumatic stress symptoms were measured via the PTSD CheckList – Civilian Version (PCL-C; Cronbach’s alpha = 0.92, high construct validity, among PLWH with a substance use disorder and other psychiatric disorder [Cuevas et al., 2007]) (Weathers et al., 1994), which is comprised of 17 survey questions. We created a binary variable for a likely diagnosis of PTSD via Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)-IV criteria. In order to have evidence of PTSD, a participant must have provided at least one symptomatic response in PCL-C questions 1-5, at least three symptomatic responses in questions 6-12, and at least two symptomatic responses in questions 13-17 (Weathers et al., 1994). If a participant had one missing observation for the binary PTSD variable over visits 68-70, and their PTSD values were constant in the two non-missing observations, then their missing PTSD observation was imputed with that constant value.

Mediators: Exercise and Volunteering

Exercise data were collected via the short International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ; test-retest reliability = 0.43-0.54, moderate criterion validity, among middle-aged Swiss adults [Mäder et al., 2006]). IPAQ scoring is based on the days and minutes of walking, moderate, or vigorous intensity physical activity in the prior week (IPAQ Research Committee, 2005). Before scoring, we linearly interpolated missing values at a visit for days and minutes of past week walking, moderate, or vigorous physical activity using non-missing values from visits directly adjacent to the missing. We then scored participant responses to the short IPAQ, and categorized total physical activity in the past week as low, moderate, or high, to provide a categorical exercise variable for the mediation analyses (IPAQ Research Committee, 2005).

Volunteering was derived from survey questions that asked participants to indicate the frequency of their volunteer work for political, charitable, religious, and/or other voluntary activities in the last 12 months (none; 1-2 times; 3-5 times; 6 or more times; don’t know; prefer not to say). We combined participant responses to generate a measure for frequency of volunteer work of any kind in the last 12 months, and linearly interpolated missing values at a visit using non-missing values from visits directly adjacent to the missing. Finally, we created a binary volunteering variable, which captured if a participant volunteered at least once or not at all in the past year, and used this variable in the mediation/moderation analyses. This definition was selected for volunteering because while the minimum amount of volunteer work in the last 12 months in order to be considered “positive for volunteering” is low, Pavlova et al. (2019a) demonstrated that mere membership in or attending meetings of voluntary organizations can have an impact on alcohol consumption and tobacco smoking behaviors. We therefore did not want to preclude the identification of these effects by requiring participants to be highly active in their volunteer activities in order to be considered “positive for volunteering”.

Outcomes: Alcohol Misuse and Current Tobacco Smoking

We assessed alcohol misuse via the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test – Consumption (AUDIT-C; test-retest reliability = 0.65-0.85, moderate criterion and discriminative validity, among male general medical patients seen at VA Medical Centers [Bradley et al., 1998]), which screens for heavy drinking and/or active alcohol abuse or dependence (Bush et al., 1998). These questions asked participants about their drinking behaviors in the prior 6 months, and were administered in the Healthy Aging substudy questionnaire, as well as in the MACS core visit surveys. In cases where a participant did not provide AUDIT-C answers in the Healthy Aging questionnaire, but did provide answers in the core visit surveys, we used the core visit answers. AUDIT-C responses had an agreement of 75-89% between the Healthy Aging and core visit surveys. We created a binary variable for alcohol misuse, defined as an AUDIT-C score of four or more unless all the points came from the first AUDIT-C question, where a participant was then defined as drinking within the recommended limits (SAMHSA). Missing values for alcohol misuse at a visit were filled in using the nearest non-missing value within one year.

Current tobacco smoking identified participants as never, former, or current smokers at each MACS visit; we created a binary variable, coded as current smoker vs. not a current smoker. We filled in missing values for current smoking at a visit using the nearest non-missing value within one year. We also created a joint outcome variable, coded as positive if a participant reported alcohol misuse and current tobacco smoking at a visit, and negative otherwise.

Covariates

We selected covariates in this analysis based on a literature review (Williamson, 2000; Gold & Marx, 2007; DiGrande et al., 2008; Regan et al., 2016; Desrichard et al., 2018; Frazier et al., 2018; Ursoiu et al., 2018; McMillan et al., 2020) and expert knowledge, with covariates chosen to minimize confounding based on previously demonstrated associations between the covariates and exposure and outcomes included in this study. The selected covariates included recruitment cohort, age, educational attainment, depressive symptoms, internalized homophobia, frailty phenotype, HIV serostatus; and among the PLWH, CD4 cell count and suppressed HIV viral load. Recruitment cohort was coded into the four waves of MACS recruitment (1984, 1987, 2001, and 2010+), and used to capture any unmeasured cohort effects. Age was measured at each visit as a continuous variable. We coded educational attainment at the baseline visit as high school or less; some college; college graduate; and at least some postgraduate education.

Depressive symptoms were determined at each visit, defined as a Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; Cronbach’s alpha = 0.81, high construct validity, among community-residing older males [Lewinsohn et al., 1997]) score of ≥ 20; we linearly interpolated missing CES-D scores at a visit using non-missing values from visits directly adjacent to the missing. A study by Armstrong et al. (2019) of CES-D scores among MACS participants found that a cutoff of ≥ 20 had a higher specificity than the more traditional cutoff of ≥ 16. Internalized homophobia was coded as binary and based on participant responses to the nine-item Internalized Homophobia Scale (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.83, high convergent validity, among a community sample of gay men, Herek et al., 1998). We defined participants as exhibiting internalized homophobia if they “agreed” or “strongly agreed” with any of the nine scale items (Herrick et al., 2013). Missing values for internalized homophobia at a visit were filled in using the nearest non-missing value within two years. Frailty phenotype was determined using the Fried criteria (high predictive validity, Fried et al., 2001), defined as the presence of three or more of: unintentional weight loss ≥ 10 pounds; low energy (self-report); weakness (dominant hand grip strength in the lowest 20%, adjusted for body mass index); slow gait speed (walking speed < 1 meter/second in a timed 4-meter walk); and low physical activity (self-report). Prior to the creation of the frailty phenotype binary variable, we filled in missing values for each criterion at a visit using the nearest non-missing value within one year.

HIV serostatus at a visit was assessed via enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, confirmed by Western blot (Kaslow et al., 1987). Among PLWH, CD4 cell count was measured via flow cytometry (Kaslow et al., 1987) and analyzed continuously. We linearly interpolated missing CD4 cell counts at a visit using non-missing values from visits directly adjacent to the missing. We analyzed suppressed HIV viral load as binary, defined as an HIV viral load < 200 copies/mL, consistent with Health Resources and Services Administration guidelines for HIV viral suppression (HRSA, 2019). We linearly interpolated missing HIV viral loads at a visit using non-missing values from visits directly adjacent to the missing.

After we defined the variables and created each dataset, we excluded missing values using a pairwise deletion approach. Within each dataset, we compared participant characteristics stratified by PTSD status using χ2 and Fisher’s exact test when table cell sizes were less than 10. We compared medians of continuous variables with the Kruskal-Wallis test. We conducted all data management using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Statistical Analysis

This study sought to determine if the association between PTSD and alcohol misuse or being a tobacco smoker is mediated or moderated by exercise or volunteering among aging MSM.

Mediation analyses model the effect of a main exposure on an outcome (direct effect), as well as the effect of the exposure on the outcome that works through a mediating variable(s) that is on the causal pathway between the exposure and the outcome (indirect effect) (MacKinnon et al., 2007). Mittinty & Vansteelandt (2020) presented a method for conducting longitudinal mediation analysis with natural effect models (see Appendix 1 for an explanation of natural effect models), which was used in this present study. This method estimates the natural direct, natural indirect, and total effects of an exposure at a single point in time on a longitudinal outcome at each measurement timepoint, using time-varying measures of the mediator and covariates. We selected this analytic method as opposed to others, such as cross-lagged panel models, because causal mediation analyses present shortcomings for cross-lagged panel models (and structural equation models in general), that do not apply to models developed from the counterfactual framework (as the Mittinty & Vansteelandt [2020] method is) (Imai et al., 2010; Lüdtke & Robitzsch, 2021). Appendix 2 briefly describes the Mittinty & Vansteelandt (2020) method. The method relies on the assumption that all confounders for the exposure-outcome, exposure-mediator, and mediator-outcome associations are accounted for in the model. Due to the longitudinal measures of the mediator and outcome, this methodological approach assumes that time-varying confounding of the mediator-outcome association is adjusted for via the exposure measure, previous longitudinal measures of the mediator and outcome, and previous/current longitudinal measures of the covariates. We adapted R code for the models provided by the authors in their publication for our needs.

Within each of our three separate datasets (with PTSD measured at a different wave; Figure S1), we lagged covariates and mediators so that along with PTSD, they modeled the time-varying outcomes at subsequent visits. This helped to establish temporality along the causal pathways. For example, in the visit 68 PTSD dataset (PTSD measured between October 1, 2017-March 31, 2018; Figure S1 Panel a & Figure S2 Panel a), the mediator and covariates measured between October 1, 2017-March 31, 2018 were used to model outcomes measured between April 1, 2018-September 30, 2019; the mediator and covariates measured between April 1, 2018-September 30, 2018 were used to model outcomes measured between October 1, 2018-September 30, 2019; and the mediator and covariates measured between October 1, 2018-March 31, 2019 were used to model the outcome measured between April 1, 2019-September 30, 2019. This pattern was repeated in the visit 69 PTSD and visit 70 PTSD datasets (Figure S2).

Within our three datasets, we generated separate models for each mediator (exercise and volunteering) and outcome (alcohol misuse, tobacco smoking, and alcohol misuse and tobacco smoking) combination for a total of six different models, per dataset. We ran these six mediation models using the entire sample and then stratified by HIV serostatus. Stratification allowed us to determine if any direct, indirect, or total effects of PTSD differed by HIV serostatus, and include HIV-specific covariates in the analyses including only PLWH. The models using the entire sample controlled for recruitment cohort, age, educational attainment, depressive symptoms, internalized homophobia, frailty phenotype, and HIV serostatus; the models among PWOH controlled for all the above (minus HIV serostatus); and the models among PLWH controlled for all the above (minus HIV serostatus), and additionally included CD4 cell count and suppressed HIV viral load. Since the outcomes used in this study were binary, final mediation model estimates obtained were the odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the natural direct, natural indirect, and total effect of PTSD at each outcome measurement wave.

Using an example with exercise as the mediator and alcohol misuse as the outcome, the estimated natural direct, natural indirect, and total effect of PTSD on alcohol misuse at each outcome measurement wave can be interpreted as follows: The natural direct effect is the odds of alcohol misuse in MSM with PTSD who exercise as if they do not have PTSD vs. the odds of alcohol misuse in MSM without PTSD who exercise as if they do not have PTSD. The natural indirect effect is the odds of alcohol misuse in MSM with PTSD who exercise as if they have PTSD vs. the odds of alcohol misuse in MSM with PTSD who exercise as if they do not have PTSD. The total effect is the sum of the natural direct effect and the natural indirect effect, and is the odds of alcohol misuse in MSM with PTSD who exercise as if they have PTSD vs. the odds of alcohol misuse in MSM without PTSD who exercise as if they do not have PTSD. Similar interpretations can be derived for the other mediators and outcomes.

Finally, we explored whether the associations between PTSD and the three outcomes were moderated by exercise or volunteering, using the entire sample within each dataset, and stratified by HIV serostatus. For the moderation analyses we used logistic regression models, and generated two models for each test – one without covariates, and one including all covariates utilized in the longitudinal mediation analyses. We used the temporally closest outcomes within each dataset in the regression models (for example, in the visit 68 PTSD dataset, we used outcomes as measured at visit 69).

We conducted all analyses in R, and relied on packages ‘tableone’ (Yoshida & Bartel, 2021), ‘mvtnorm’ (Genz et al., 2021), ‘VGAM’ (Yee, 2015), and ‘geepack’ (Højsgaard et al., 2006).

Results

There were 1,318 men enrolled in the Healthy Aging substudy. In the visit 68 PTSD dataset (PTSD measured between October 1, 2017-March 31, 2018), 235 (18%) men who were missing the measurement for PTSD, 1 (0%) man who was missing measures for alcohol misuse or tobacco smoking over all of follow-up, and 184 (14%) men who were missing measures for exercise or volunteering over all of follow-up, were excluded. This resulted in a visit 68 PTSD dataset analytic sample of 898 MSM. In the visit 69 PTSD dataset (PTSD measured between April 1, 2018-September 30, 2018), 231 (18%) men who were missing the measurement for PTSD, 2 (0%) men who were missing measures for alcohol misuse or smoking over all of follow-up, and 195 (15%) men who were missing measures for exercise or volunteering over all of follow-up, were excluded. This resulted in an analytic sample of 890 MSM for the visit 69 PTSD dataset. In the visit 70 PTSD dataset (PTSD measured between October 1, 2018-March 31, 2019), 252 (19%) men were missing the measurement for PTSD, 8 (1%) men were missing measures for alcohol misuse or smoking over all of follow-up, and 163 (12%) men were missing measures for exercise or volunteering over all of follow-up. We excluded these men. This resulted in a visit 70 PTSD dataset analytic sample of 895 MSM.

Within the visit 68 PTSD dataset, 821 (91%) MSM did not have PTSD, while 77 (9%) MSM had evidence of PTSD. This is compared to 810 (91%) MSM who did not have PTSD and 80 (9%) MSM who had PTSD in the visit 69 PTSD dataset, and 813 (91%) MSM who did not have PTSD and 82 (9%) MSM who did have PTSD in the visit 70 PTSD dataset (Table 1). At the first available collection wave for each variable (e.g., visit 68 PTSD dataset: visit 68 for the mediators and covariates; visit 69 for the outcomes – see Figure S1), a statistically significantly greater proportion of MSM with PTSD reported participation in alcohol misuse as compared to MSM without PTSD in the visit 68 PTSD dataset only (p-value = 0.04). Across all three datasets, MSM with PTSD were statistically significantly more likely to be tobacco smokers and misuse alcohol and smoke compared to MSM without PTSD (all p-values ≤ 0.01) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Analytic sample characteristics at the first available collection wave for each variable, stratified by evidence of PTSD.

Visit 68 (10/1/17 – 3/31/18) PTSD dataset: 898 men who have sex with men (No PTSD N = 821; PTSD N = 77).

Visit 69 (4/1/18 – 9/30/18) PTSD dataset: 890 men who have sex with men (No PTSD N = 810; PTSD N = 80).

Visit 70 (10/1/18 – 3/31/19) PTSD dataset: 895 men who have sex with men (No PTSD N = 813; PTSD N = 82).

| Variable | No PTSD | PTSD | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol misuse (N, %) | |||

| Visit 68 dataset | 176 (21) | 25 (33) | 0.04 |

| Visit 69 dataset | 179 (22) | 19 (24) | 0.84 |

| Visit 70 dataset | 202 (25) | 20 (24) | 1.00 |

| Currently smoking (N, %) | |||

| Visit 68 dataset | 109 (13) | 21 (27) | < 0.01 |

| Visit 69 dataset | 104 (13) | 20 (25) | < 0.01 |

| Visit 70 dataset | 102 (13) | 23 (28) | < 0.01 |

| Alcohol misuse and currently smoking (N, %) | |||

| Visit 68 dataset | 34 (4) | 10 (13) | < 0.01 |

| Visit 69 dataset | 35 (4) | 10 (13) | < 0.01 |

| Visit 70 dataset | 39 (5) | 10 (12) | 0.01 |

| Total exercise (N, %) | |||

| Visit 68 dataset | 0.33 | ||

| Low | 172 (22) | 21 (29) | |

| Moderate | 277 (35) | 24 (33) | |

| High | 344 (43) | 27 (38) | |

| Visit 69 dataset | 0.20 | ||

| Low | 189 (24) | 26 (33) | |

| Moderate | 289 (37) | 24 (30) | |

| High | 311 (39) | 29 (37) | |

| Visit 70 dataset | 0.26 | ||

| Low | 245 (30) | 31 (38) | |

| Moderate | 234 (29) | 18 (22) | |

| High | 334 (41) | 33 (40) | |

| Volunteered at least once in the past 12 months (N, %) | |||

| Visit 68 dataset | 473 (58) | 51 (66) | 0.20 |

| Visit 69 dataset | 478 (59) | 40 (50) | 0.15 |

| Visit 70 dataset | 472 (58) | 43 (52) | 0.39 |

| Recruitment cohort (N, %) | |||

| Visit 68 dataset | < 0.01 | ||

| 1984 | 490 (60) | 28 (36) | |

| 1987 | 61 (7) | 5 (7) | |

| 2001 | 227 (28) | 34 (44) | |

| 2010+ | 43 (5) | 10 (13) | |

| Visit 69 dataset | < 0.01 | ||

| 1984 | 488 (60) | 28 (35) | |

| 1987 | 63 (8) | 3 (4) | |

| 2001 | 220 (27) | 36 (45) | |

| 2010+ | 39 (5) | 13 (16) | |

| Visit 70 dataset | < 0.01 | ||

| 1984 | 487 (60) | 35 (43) | |

| 1987 | 63 (8) | 4 (5) | |

| 2001 | 221 (27) | 31 (38) | |

| 2010+ | 42 (5) | 12 (15) | |

| Age, in years (median [IQR]) | |||

| Visit 68 dataset | 62.4 [56.3, 67.7] | 56.1 [49.8, 63.6] | < 0.01 |

| Visit 69 dataset | 62.8 [56.9, 68.0] | 57.6 [51.2, 65.2] | < 0.01 |

| Visit 70 dataset | 63.3 [57.4, 68.7] | 58.4 [50.9, 64.4] | < 0.01 |

| Educational attainment (N, %) | |||

| Visit 68 dataset | 0.02 | ||

| High school or less | 97 (12) | 17 (22) | |

| Some college | 192 (23) | 21 (27) | |

| College graduate | 218 (27) | 20 (26) | |

| At least some postgraduate education | 314 (38) | 19 (25) | |

| Visit 69 dataset | < 0.01 | ||

| High school or less | 95 (12) | 22 (28) | |

| Some college | 192 (24) | 15 (19) | |

| College graduate | 215 (27) | 20 (25) | |

| At least some postgraduate education | 308 (38) | 23 (29) | |

| Visit 70 dataset | 0.01 | ||

| High school or less | 93 (11) | 19 (23) | |

| Some college | 192 (24) | 21 (26) | |

| College graduate | 226 (28) | 19 (23) | |

| At least some postgraduate education | 302 (37) | 23 (28) | |

| Depressive symptoms (N, %) | |||

| Visit 68 dataset | 75 (9) | 54 (70) | < 0.01 |

| Visit 69 dataset | 85 (11) | 55 (69) | < 0.01 |

| Visit 70 dataset | 81 (10) | 61 (74) | < 0.01 |

| Internalized homophobia (N, %) | |||

| Visit 68 dataset | 138 (17) | 35 (46) | < 0.01 |

| Visit 69 dataset | 147 (18) | 28 (35) | < 0.01 |

| Visit 70 dataset | 149 (18) | 35 (43) | < 0.01 |

| Frailty phenotype (N, %) | |||

| Visit 68 dataset | 70 (9) | 13 (17) | 0.02 |

| Visit 69 dataset | 65 (8) | 18 (23) | < 0.01 |

| Visit 70 dataset | 76 (10) | 10 (13) | 0.43 |

| HIV seropositive (N, %) | |||

| Visit 68 dataset | 385 (47) | 47 (61) | 0.02 |

| Visit 69 dataset | 374 (46) | 51 (64) | < 0.01 |

| Visit 70 dataset | 381 (47) | 49 (60) | 0.04 |

| CD4 cell count, in cells/mm3 - PLWH only (median [IQR]) | |||

| Visit 68 dataset | 674.0 [477.0, 850.3] | 667.0 [508.0, 876.0] | 0.56 |

| Visit 69 dataset | 681.0 [488.3, 832.0] | 621.0 [516.5, 769.8] | 0.52 |

| Visit 70 dataset | 639.0 [483.0, 853.0] | 682.0 [514.5, 855.0] | 0.52 |

| Unsuppressed HIV viral load (≥ 200 copies/mL) - PLWH only (N, %) | |||

| Visit 68 dataset | 24 (6) | 6 (13) | 0.11 |

| Visit 69 dataset | 21 (6) | 3 (6) | 1.00 |

| Visit 70 dataset | 15 (4) | 7 (15) | < 0.01 |

Note. IQR = Interquartile range; PLWH = People living with HIV; PTSD = Posttraumatic stress disorder.

Across all three datasets (Table 1), there was no statistically significant difference in exercise or volunteering between MSM with and without PTSD. Relative to MSM without PTSD, MSM with PTSD were more likely to have been enrolled in later MACS recruitment waves; have lower educational attainment; have depressive symptoms and internalized homophobia; be HIV seropositive; and were on average younger in age (all p-values ≤ 0.04). Additionally, among PLWH in the visit 70 PTSD dataset, a greater proportion with PTSD had unsuppressed HIV viral load (15%) as compared to those without PTSD (4%; p-value < 0.01).

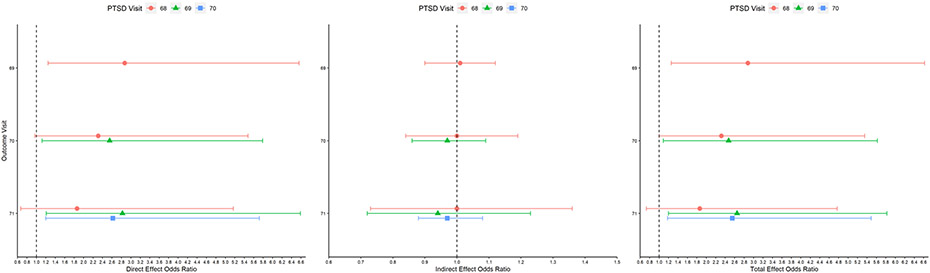

In longitudinal mediation analyses across all three datasets, there was no statistically significant natural indirect effect of exercise or volunteering regardless of outcome (alcohol misuse, tobacco smoking, or alcohol misuse and tobacco smoking; Figures 1-6). Thus, there is no evidence that the association between PTSD and alcohol misuse or being a tobacco smoker was mediated by exercise or volunteering among aging MSM in this sample.

Figure 1. Longitudinal mediation analysis results with exercise as the mediator and alcohol misuse as the outcome, among all men.

Bars represent the 95% confidence intervals. The vertical dashed line marks an odds ratio of 1.0.

PTSD = Posttraumatic stress disorder.

Due to lack of statistical significance of the natural indirect effect across longitudinal mediation analyses, the natural direct and total effect largely mirrored each other. In the dataset with PTSD measured at visit 68, the odds of alcohol misuse at visit 69 were estimated as 1.86 times (95% CI: 1.07-3.21 times) greater for MSM with PTSD vs. without PTSD when exercise was considered as a mediator (Figure 1; Table S1). When including volunteering as a potential mediator, the odds of visit 69 alcohol misuse were estimated at 1.80 times (95% CI: 1.06-3.06 times) greater for MSM with PTSD vs. without PTSD (Figure 2; Table S2).

Figure 2. Longitudinal mediation analysis results with volunteering as the mediator and alcohol misuse as the outcome, among all men.

Bars represent the 95% confidence intervals. The vertical dashed line marks an odds ratio of 1.0.

PTSD = Posttraumatic stress disorder.

Being a tobacco smoker as the outcome demonstrated a much more consistent statistically significant association with PTSD. With exercise as a mediator, the natural direct and total effects were statistically significant across all the datasets and outcome visits. The estimated odds of being a smoker at a future visit in MSM with PTSD ranged between 2.01 and 2.71 times higher than the odds for those without PTSD (Figure 3; Table S3). Results were similar in models with volunteering as the mediator. The estimated odds of being a smoker at a future visit with PTSD ranged between 1.93 and 2.66 times higher than the odds without PTSD (Figure 4; Table S4).

Figure 3. Longitudinal mediation analysis results with exercise as the mediator and current tobacco smoking as the outcome, among all men.

Bars represent the 95% confidence intervals. The vertical dashed line marks an odds ratio of 1.0.

PTSD = Posttraumatic stress disorder.

Figure 4. Longitudinal mediation analysis results with volunteering as the mediator and current tobacco smoking as the outcome, among all men.

Bars represent the 95% confidence intervals. The vertical dashed line marks an odds ratio of 1.0.

PTSD = Posttraumatic stress disorder.

Figure 5 & Table S5 present the natural direct, natural indirect, and total effects estimated in the longitudinal mediation analyses across all three datasets with exercise as the mediator and alcohol misuse and smoking as the outcome. In these analyses, the direct and total effects of PTSD were statistically significant across all outcome measures for the visit 69 and visit 70 PTSD datasets. For the visit 68 PTSD dataset, the natural direct effect was statistically significant for visit 69 alcohol misuse and smoking, and the estimated total effect was statistically significant for visit 69 and visit 70 alcohol misuse and smoking. The odds of alcohol misuse and being a tobacco smoker at a future visit for MSM with PTSD were between 2.32 and 2.88 times greater than the odds of alcohol misuse and being a smoker at a future visit for those without PTSD. Results followed the same pattern when volunteering was considered as the mediator (Figure 6; Table S6). The longitudinal mediation analyses stratified by HIV serostatus produced similar results to the overall analyses, and thus are not presented.

Figure 5. Longitudinal mediation analysis results with exercise as the mediator and alcohol misuse and current tobacco smoking as the outcome, among all men.

Bars represent the 95% confidence intervals. The vertical dashed line marks an odds ratio of 1.0.

PTSD = Posttraumatic stress disorder.

Figure 6. Longitudinal mediation analysis results with volunteering as the mediator and alcohol misuse and current tobacco smoking as the outcome, among all men.

Bars represent the 95% confidence intervals. The vertical dashed line marks an odds ratio of 1.0.

In the PTSD visit 68 analyses, 1/10,000 random perturbation repetitions was excluded because it resulted in extreme model estimates.

PTSD = Posttraumatic stress disorder.

In the moderation analyses (Tables 2, 3, 4; Tables S7-S12), the only models with a statistically significant interaction term were those with visit 69 alcohol misuse as the outcome and visit 68 PTSD and volunteering as the interaction (statistically significant with and without covariates in the model), among the entire sample (Table 2) and PWOH only (Table S7); and with visit 71 smoking as the outcome and visit 70 PTSD and volunteering as the interaction (statistically significant without covariates in the model), among PLWH only (Table S11). For all models with a significant interaction term, individuals who volunteered had a significant association between PTSD and increased odds of the outcome (borderline significant in the Table S7 adjusted model), while individuals who did not volunteer did not have a significant association. Overall, there is little evidence from our study that the association between PTSD and alcohol misuse, being a tobacco smoker, or alcohol misuse and smoking is moderated by exercise or volunteering.

Table 2.

Logistic regression between PTSD and alcohol misuse by levels of exercise or volunteering, among all men.

| Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

Exercise | Volunteered at least once in

the past 12 months |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Moderate | High | P-valuea | No | Yes | P-valuea | |

| Crude | |||||||

| Visit 68 PTSD | 1.42 (0.48, 4.17) |

1.81 (0.74, 4.43) |

2.18 (0.96, 4.97) |

Moderate vs. Low: 0.74 High vs. Low: 0.53 |

0.74 (0.27, 2.03) |

2.75 (1.50, 5.04) |

0.03 |

| Visit 69 PTSD | 1.37 (0.54, 3.49) |

1.26 (0.50, 3.17) |

0.85 (0.31, 2.33) |

Moderate vs. Low: 0.90 High vs. Low: 0.50 |

1.19 (0.57, 2.50) |

0.96 (0.43, 2.14) |

0.69 |

| Visit 70 PTSD | 1.12 (0.48, 2.64) |

1.71 (0.61, 4.77) |

0.59 (0.24, 1.48) |

Moderate vs. Low: 0.54 High vs. Low: 0.32 |

0.68 (0.30, 1.53) |

1.30 (0.65, 2.63) |

0.23 |

| Adjusted b | |||||||

| Visit 68 PTSD | 1.19 (0.32, 4.42) |

1.77 (0.53, 5.93) |

2.53 (0.92, 6.91) |

Moderate vs. Low: 0.62 High vs. Low: 0.46 |

0.99 (0.31, 3.20) |

2.30 (1.06, 5.01) |

0.05 |

| Visit 69 PTSD | 0.85 (0.27, 2.63) |

1.11 (0.36, 3.47) |

0.86 (0.26, 2.78) |

Moderate vs. Low: 0.95 High vs. Low: 0.69 |

1.02 (0.42, 2.52) |

0.96 (0.39, 2.38) |

0.73 |

| Visit 70 PTSD | 0.94 (0.34, 2.59) |

1.05 (0.30, 3.65) |

0.87 (0.27, 2.86) |

Moderate vs. Low: 0.63 High vs. Low: 0.34 |

0.53 (0.20, 1.39) |

1.31 (0.54, 3.20) |

0.24 |

Note. Boldface indicates statistically significant results.

P-value for interaction term between PTSD and exercise or volunteering.

Models adjusted for recruitment cohort, age, educational attainment, depressive symptoms, internalized homophobia, frailty phenotype, and HIV serostatus.

CI = Confidence interval; PTSD = Posttraumatic stress disorder.

Table 3.

Logistic regression between PTSD and current tobacco smoking by levels of exercise or volunteering, among all men.

| Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

Exercise | Volunteered at least once in

the past 12 months |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Moderate | High | P-valuea | No | Yes | P-valuea | |

| Crude | |||||||

| Visit 68 PTSD | 1.96 (0.73, 5.22) |

1.65 (0.53, 5.14) |

3.29 (1.35, 8.02) |

Moderate vs. Low: 0.82 High vs. Low: 0.44 |

1.98 (0.75, 5.20) |

2.66 (1.38, 5.14) |

0.62 |

| Visit 69 PTSD | 2.50 (1.03, 6.10) |

1.85 (0.65, 5.26) |

2.44 (0.92, 6.47) |

Moderate vs. Low: 0.67 High vs. Low: 0.97 |

1.76 (0.79, 3.93) |

2.80 (1.33, 5.91) |

0.41 |

| Visit 70 PTSD | 2.12 (0.93, 4.80) |

1.04 (0.23, 4.81) |

4.72 (2.10, 10.61) |

Moderate vs. Low: 0.42 High vs. Low: 0.17 |

1.97 (0.88, 4.43) |

3.51 (1.75, 7.05) |

0.29 |

| Adjusted b | |||||||

| Visit 68 PTSD | 2.88 (0.74, 11.28) |

0.52 (0.11, 2.44) |

2.60 (0.88, 7.72) |

Moderate vs. Low: 0.40 High vs. Low: 0.92 |

2.44 (0.72, 8.27) |

1.48 (0.63, 3.46) |

0.98 |

| Visit 69 PTSD | 0.89 (0.27, 2.89) |

0.71 (0.17, 2.93) |

3.51 (0.97, 12.72) |

Moderate vs. Low: 0.71 High vs. Low: 0.49 |

1.03 (0.38, 2.84) |

1.47 (0.56, 3.90) |

0.22 |

| Visit 70 PTSD | 1.50 (0.50, 4.53) |

0.52 (0.09, 3.16) |

5.89 (1.38, 25.07) |

Moderate vs. Low: 0.32 High vs. Low: 0.42 |

1.23 (0.43, 3.48) |

2.34 (0.88, 6.20) |

0.71 |

Note. Boldface indicates statistically significant results.

P-value for interaction term between PTSD and exercise or volunteering.

Models adjusted for recruitment cohort, age, educational attainment, depressive symptoms, internalized homophobia, frailty phenotype, and HIV serostatus.

CI = Confidence interval; PTSD = Posttraumatic stress disorder.

Table 4.

Logistic regression between PTSD and alcohol misuse and current tobacco smoking by levels of exercise or volunteering, among all men.

| Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

Exercise | Volunteered at least once in

the past 12 months |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Moderate | High | P-valuea | No | Yes | P-valuea | |

| Crude | |||||||

| Visit 68 PTSD | 3.02 (0.75, 12.17) |

4.80 (1.19, 19.46) |

3.18 (0.85, 11.94) |

Moderate vs. Low: 0.64 High vs. Low: 0.96 |

1.33 (0.16, 10.80) |

4.01 (1.75, 9.18) |

0.34 |

| Visit 69 PTSD | 7.80 (2.39, 25.49) |

1.45 (0.32, 6.71) |

2.81 (0.57, 13.88) |

Moderate vs. Low: 0.09 High vs. Low: 0.31 |

3.08 (1.14, 8.28) |

3.01 (0.96, 9.43) |

0.98 |

| Visit 70 PTSD | 3.96 (1.40, 11.22) |

1.19 (0.15, 9.79) |

2.29 (0.62, 8.40) |

Moderate vs. Low: 0.32 High vs. Low: 0.52 |

2.32 (0.74, 7.33) |

3.17 (1.21, 8.26) |

0.68 |

| Adjusted b | |||||||

| Visit 68 PTSD | 2.94 (0.37, 23.66) |

1.71 (0.22, 13.21) |

1.91 (0.41, 8.88) |

Moderate vs. Low: 0.92 High vs. Low: 0.86 |

1.24 (0.09, 16.91) |

2.10 (0.73, 6.07) |

0.42 |

| Visit 69 PTSD | 3.31 (0.67, 16.32) |

1.15 (0.16, 8.32) |

1.26 (0.14, 11.28) |

Moderate vs. Low: 0.11 High vs. Low: 0.51 |

1.35 (0.40, 4.57) |

1.44 (0.36, 5.80) |

0.90 |

| Visit 70 PTSD | 2.46 (0.66, 9.21) |

0.68 (0.05, 8.82) |

2.41 (0.34, 17.08) |

Moderate vs. Low: 0.22 High vs. Low: 0.41 |

1.43 (0.34, 6.01) |

1.72 (0.46, 6.36) |

0.91 |

Note. Boldface indicates statistically significant results.

P-value for interaction term between PTSD and exercise or volunteering.

Models adjusted for recruitment cohort, age, educational attainment, depressive symptoms, internalized homophobia, frailty phenotype, and HIV serostatus.

CI = Confidence interval; PTSD = Posttraumatic stress disorder.

Discussion

Results from our analyses did not support the hypotheses that exercise or volunteering mediated or moderated the association between PTSD and alcohol misuse or being a tobacco smoker among aging MSM. Further, results did not differ by HIV serostatus. These findings may reflect the fact that we did not observe any statistically significant baseline differences in exercise or volunteering between MSM with and without PTSD. The PTSD vs. no PTSD groups included in our particular study therefore may have been too similar regarding levels of exercise and volunteering for a significant mediation or moderation effect to be detected. In other samples this may differ, and warrants further exploration in diverse study populations.

In a study using MACS Healthy Aging substudy data that explored psychological connection to the gay community and negative self-appraisals related to physical appearance and aging, it was found that fitness engagement (level of physical activity and motivation to have a fit body) mediated this relationship, such that psychological connection to the gay community was associated with greater fitness engagement and fitness engagement was associated with less negative self-appraisals. Further, the protective effect of fitness engagement on negative self-appraisals was shown to be stronger among PLWH as compared to PWOH (Brennan-Ing et al., 2022). Thus, in certain contexts, fitness-related activities may prove to be protective factors and promote healthy aging among midlife and older MSM. An additional study that drew upon MACS Healthy Aging substudy data explored volunteering, optimism, religiosity/spirituality, and global resiliency as mediating factors to buffer the relationship between internalized homophobia and depressive symptoms (Okafor et al., 2023). It was found that optimism and global resiliency mediated and buffered the relationship between internalized homophobia and depressive symptoms (internalized homophobia reduced these mediating factors, but the mediating factors were associated with less depressive symptoms). Religiosity/spirituality was shown to be a mediator but not protective (internalized homophobia reduced religiosity/spirituality, and religiosity/spirituality was associated with more depressive symptoms), and no statistically significant mediating effect of volunteering was found (Okafor et al., 2023). The lack of a protective mediating effect of volunteering agrees with our study findings. The overall results of Okafor et al. (2023) suggest that optimism and global resiliency may be effective protective factors for discouraging alcohol misuse or smoking among aging MSM with PTSD.

It is important to note that although this study did not find evidence of mediation/moderation by exercise or volunteering on the association between PTSD and alcohol misuse or being a smoker, this does not rule out mediation or moderation of this association by other, yet undiscovered protective factors. Additionally, future studies should consider alternate strategies for measuring and analyzing exercise and volunteering as exposures (e.g., self-reporting exercise vs. capture via an accelerometer). Further, while our study examined self-motivated exercise and volunteering as potential protective factors, these activities might have more protective effects against alcohol misuse or smoking were they prescribed interventions. These types of interventions, which would contain more structure and accountability than self-motivated exercise and volunteering, may have quite different mediation or moderation effects on the association between PTSD and misusing alcohol or smoking, and may prove more successful. Indeed, a randomized controlled trial demonstrated that a yoga intervention may help to decrease rates of alcohol and drug abuse (Reddy et al., 2014), while a web-based cognitive-behavioral intervention was shown to reduce alcohol consumption and PTSD symptoms (Brief et al., 2013). Among veterans with PTSD, an acceptance and commitment therapy intervention was effective for encouraging smoking cessation (Kelly et al., 2015), and a combined cognitive processing therapy and smoking cessation counseling/pharmacotherapy intervention was effective for reducing smoking behaviors and PTSD symptoms (Dedert et al., 2019). Whether these interventions are equally effective for discouraging alcohol misuse or smoking tobacco among aging MSM with PTSD remains to be determined. Finally, future studies may benefit from specifically considering the context in which exercise or volunteering activities take place. Different types of exercise or volunteering may have differential protective effects against alcohol misuse or smoking, and length of time that an individual has participated in these activities may have important effects as well.

Our longitudinal mediation analyses revealed a clear and consistently significant association between PTSD and being a tobacco smoker. MSM with PTSD had an estimated odds of smoking at a future timepoint that was approximately double that of MSM without PTSD. These results corroborate previous studies that show a twice greater likelihood of smoking among individuals with PTSD relative to those without (Kearns et al., 2018). O’Cleirigh et al. (2015) found a dose-response relationship between number of sexual minority stressors and trauma experiences and odds of smoking among MSM, and D’Avanzo et al. (2016) showed increased smoking odds among young MSM with PTSD symptoms as compared to young MSM without these symptoms. Further, our results showed a strong association between PTSD and the alcohol misuse and smoking outcome pattern. If our proposed directed acyclic graphs (DAGs; Figure S2) are accurate and all confounders adjusted for in our models, then the associations between PTSD and smoking, and PTSD and alcohol misuse and smoking among aging MSM may be interpreted as causal (Greenland et al., 1999).

While our study had many strengths, including use of data from a large cohort study with robust methods for data collection, it was not without its limitations. Our DAGs and models may have been misspecified, or there may have been unmeasured/uncontrolled for confounding, which could have resulted in incorrect effect estimates. Second, because the protective factors we examined were self-motivated and this was not a randomized controlled trial, there was likely selection bias in terms of which participants were exercising and volunteering, which may have influenced how those activities were associated with alcohol misuse and being a tobacco smoker. Third, though prior studies have suggested that minimal engagement in voluntary organizations can have an effect on alcohol consumption and tobacco smoking (Pavlova et al., 2019a; Pavlova et al., 2019b), it may be the case that in this context volunteering is only protective against alcohol misuse and being a tobacco smoker when it is performed frequently. Exploring how different definitions of volunteering may influence the association between PTSD and alcohol misuse and tobacco smoking should serve as the subject for future research. Finally, the longitudinal mediation analysis method from Mittinty & Vansteelandt (2020) employed in this study utilized inverse probability weighting (IPW) to adjust for covariates in a generalized estimating equation (GEE) model (Appendix 2). IPW adjustment in GEE models can lead to biased estimates (Tchetgen Tchetgen et al., 2012). Specifying an independence working correlation structure in the GEE can produce unbiased estimates (Tchetgen Tchetgen et al., 2012) and this strategy was used in our study, however an independence correlation between longitudinal measures is likely incorrect.

In summary, this study showed that there is a robust association between PTSD and being a tobacco smoker among aging MSM, with no differential effects by HIV serostatus. These results suggest that effective smoking cessation programs are needed for aging MSM with PTSD. These programs may reduce the incidence of diseases such as cardiovascular disease and smoking-related cancers, both of which disproportionately impact PLWH (Hemkens & Bucher, 2014; Hessol et al., 2021). While we failed to find evidence for exercise or volunteering as pathways to discourage alcohol misuse or smoking, other potentially efficacious protective factors likely exist, such as optimism or resiliency (Okafor et al., 2023), brief motivational interventions (Monahan et al., 2013), medication and mental health treatment adherence (Oslin et al., 2002; Raupach et al., 2014), mobile health applications (Hicks et al., 2017), nicotine replacement therapy (Stead et al., 2012), or social support (Wagner et al., 2004; Groh et al., 2007). These protective factors should be further explored and uncovered, particularly in the context of aging MSM, in future work.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study is funded by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (grant R01-MD010680 Plankey & Friedman). The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). MACS/WIHS Combined Cohort Study (MWCCS) (Principal Investigators): Atlanta Clinical Research Site (CRS) (Ighovwerha Ofotokun, Anandi Sheth, and Gina Wingood), grant U01-HL146241; Baltimore CRS (Todd Brown and Joseph Margolick), grant U01-HL146201; Bronx CRS (Kathryn Anastos, David Hanna, and Anjali Sharma), grant U01-HL146204; Brooklyn CRS (Deborah Gustafson and Tracey Wilson), grant U01-HL146202; Data Analysis and Coordination Center (Gypsyamber D’Souza, Stephen Gange and Elizabeth Topper), grant U01-HL146193; Chicago-Cook County CRS (Mardge Cohen and Audrey French), grant U01-HL146245; Chicago-Northwestern CRS (Steven Wolinsky), grant U01-HL146240; Northern California CRS (Bradley Aouizerat, Jennifer Price, and Phyllis Tien), grant U01-HL146242; Los Angeles CRS (Roger Detels and Matthew Mimiaga), grant U01-HL146333; Metropolitan Washington CRS (Seble Kassaye and Daniel Merenstein), grant U01-HL146205; Miami CRS (Maria Alcaide, Margaret Fischl, and Deborah Jones), grant U01-HL146203; Pittsburgh CRS (Jeremy Martinson and Charles Rinaldo), grant U01-HL146208; UAB-MS CRS (Mirjam-Colette Kempf, Jodie Dionne-Odom, and Deborah Konkle-Parker), grant U01-HL146192; UNC CRS (Adaora Adimora and Michelle Floris-Moore), grant U01-HL146194.

The MWCCS is funded primarily by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), with additional co-funding from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute Of Child Health & Human Development (NICHD), National Institute On Aging (NIA), National Institute Of Dental & Craniofacial Research (NIDCR), National Institute Of Allergy And Infectious Diseases (NIAID), National Institute Of Neurological Disorders And Stroke (NINDS), National Institute Of Mental Health (NIMH), National Institute On Drug Abuse (NIDA), National Institute Of Nursing Research (NINR), National Cancer Institute (NCI), National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD), National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK), National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD), and in coordination and alignment with the research priorities of the National Institutes of Health, Office of AIDS Research (OAR). MWCCS data collection is also supported by grant UL1-TR000004 (UCSF CTSA), grant UL1-TR003098 (JHU ICTR), grant UL1-TR001881 (UCLA CTSI), grant P30-AI-050409 (Atlanta CFAR), grant P30-AI-073961 (Miami CFAR), grant P30-AI-050410 (UNC CFAR), grant P30-AI-027767 (UAB CFAR), and grant P30-MH-116867 (Miami CHARM).

The authors are indebted to the participants of the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study (MACS) Healthy Aging Study. The authors thank the staff at the four MACS sites for implementation support, and John Welty, Montserrat Tarrago, and Katherine McGowan for data support of this study.

Appendix 1

Natural effect models, which rely on counterfactuals, decompose the total effect of the exposure on the outcome into the natural direct effect and the natural indirect effect. The natural direct effect is defined as the difference in the outcome between two scenarios where the exposure has two different values and the mediator has a value as would be observed under one of those scenarios (Pearl, 2001). In an example with a binary exposure (where exposed = 1 and unexposed = 0) and outcome (where outcome event = 1 and no outcome event = 0) and mediator of any type (categorical or continuous), the natural direct effect could be represented by:

where is the outcome when the exposure is equal to 1 (exposed) and the mediator () is at the level as would be observed if the exposure were equal to 0 (unexposed), and is the outcome when the exposure is equal to 0 and the mediator is at the level as would be observed if the exposure were equal to 0. The natural indirect effect is defined as the difference in the outcome between two scenarios where the exposure has one value and the mediator has the values as would be observed among the exposed and unexposed (Pearl, 2001). In an example with a binary exposure (where exposed = 1 and unexposed = 0) and outcome (where outcome event = 1 and no outcome event = 0) and mediator of any type, the natural indirect effect could be represented by:

where is the outcome when the exposure is equal to 0 (unexposed) and the mediator () is at the level as would be observed if the exposure were equal to 1 (exposed), and is the outcome when the exposure is equal to 0 and the mediator is at the level as would be observed if the exposure were equal to 0 (Pearl, 2001; Lange et al., 2012).

Appendix 2

From the Mittinty & Vansteelandt (2020) longitudinal mediation analysis method: Inverse probability weighting was used to obtain exposure weights and mediator weights at each timepoint (which account for exposure-outcome, exposure-mediator, and mediator-outcome confounding). Exposure weights were truncated at the 95th percentile to avoid outlier weights having an undue influence on results. An additional variable for the exposure was added to the dataset and the dataset replicated once per timepoint per person, with the new exposure variable once taking its original value and once being set to a reference value within each replication pair. Within each relevant row of the dataset, the product of the exposure and mediator weights was used as a final weight variable.

The estimates for the natural direct and indirect effects were obtained by fitting a weighted generalized estimating equation (GEE; using the final weights) of the time-varying outcome on the original exposure variable, the new exposure variable, timepoint, and separate interactions between timepoint and the original and new exposure variables. The sum of the natural direct and natural indirect effect estimates provided the total effect estimate. Standard errors (and thus 95% confidence intervals) for the natural direct and indirect, and total effect estimates were obtained through a procedure that, prior to calculation of the exposure and mediator weights, randomly perturbed the values used to calculate the weights. The weighted GEE used to obtain the coefficients for estimating the natural direct and indirect effects was then run with the new weights, and by repeating this process 10,000 times and extracting the coefficient estimates and variance-covariance matrix from each weighted GEE run, the standard error for the total and natural direct and indirect effect estimates was found.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The Authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Works Cited

- Abraham HD, & Fava M (1999). Order of onset of substance abuse and depression in a sample of depressed outpatients. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 40(1), 44–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akbar M, Egli M, Cho YE, Song BJ, & Noronha A (2018). Medications for alcohol use disorders: An overview. Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 185, 64–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong NM, Surkan PJ, Treisman GJ, Sacktor NC, Irwin MR, Teplin LA, Stall RC, Jacobson LP, & Abraham AG (2019). Optimal metrics for identifying long term patterns of depression in older HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected men who have sex with men. Aging & Mental Health, 23(4), 507–514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boarts JM, Sledjeski EM, Bogart LM, & Delahanty DL (2006). The differential impact of PTSD and depression on HIV disease markers and adherence to HAART in people living with HIV. AIDS and Behavior, 10(3), 253–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen S, De Boer D, & Bergman AL (2017). The role of mindfulness as approach-based coping in the PTSD-substance abuse cycle. Addictive Behaviors, 64, 212–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley KA, McDonell MB, Bush K, Kivlahan DR, Diehr P, & Fihn SD (1998). The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions: Reliability, validity, and responsiveness to change in older male primary care patients. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 22(8), 1842–1849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley R, Greene J, Russ E, Dutra L, & Westen D (2005). A multidimensional meta-analysis of psychotherapy for PTSD. American Journal of Psychiatry, 162(2), 214–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan-Ing M, Haberlen S, Ware D, Egan JE, Brown AL, Meanley S, Palella FJ, Bolan R, Cook JA, Okafor CN, Friedman MR, & Plankey MW (2022). Psychological connection to the gay community and negative self-appraisals in middle-aged and older men who have sex with men: The mediating effects of fitness engagement. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 77(1), 39–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brief DJ, Rubin A, Keane TM, Enggasser JL, Roy M, Helmuth E, Hermos J, Lachowicz M, Rybin D, & Rosenbloom D (2013). Web intervention for OEF/OIF veterans with problem drinking and PTSD symptoms: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 81(5), 890–900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RA, Abrantes AM, Read JP, Marcus BH, Jakicic J, Strong DR, Oakley JR, Ramsey SE, Kahler CW, Stuart G, Dubreuil ME, & Gordon AA (2009). Aerobic exercise for alcohol recovery: Rationale, program description, and preliminary findings. Behavior Modification, 33(2), 220–249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush K, Kivlahan DR, McDonell MB, Fihn SD, Bradley KA, & Ambulatory Care Quality Improvement Project (ACQUIP). (1998). The AUDIT Alcohol Consumption Questions (AUDIT-C): An effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Archives of Internal Medicine, 158(16), 1789–1795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloitre M, Hyland P, Bisson JI, Brewin CR, Roberts NP, Karatzias T, & Shevlin M (2019). ICD-11 posttraumatic stress disorder and complex posttraumatic stress disorder in the United States: A population-based study. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 32(6), 833–842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crane HM, McCaul ME, Chander G, Hutton H, Nance RM, Delaney JA, Merrill JO, Lau B, Mayer KH, Mugavero MJ, Mimiaga M, Willig JH, Burkholder GA, Drozd DR, Fredericksen RJ, Cropsey K, Moore RD, Simoni JM, Mathews WC, Eron JJ, Napravnik S, Christopoulos K, Geng E, Saag MS, & Kitahata MM (2017). Prevalence and factors associated with hazardous alcohol use among persons living with HIV across the US in the current era of antiretroviral treatment. AIDS and Behavior, 21(7), 1914–1925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuevas CA, Bollinger AR, Vielhauer MJ, Morgan EE, Sohler NL, Brief DJ, Miller AL, & Keane TM (2007). HIV/AIDS Cost Study: Construct validity and factor structure of the PTSD Checklist in dually diagnosed HIV-seropositive adults. Journal of Trauma Practice, 5(4), 29–51. [Google Scholar]

- D'Avanzo PA, Halkitis PN, Yu K, & Kapadia F (2016). Demographic, mental health, behavioral, and psychosocial factors associated with cigarette smoking status among young men who have sex with men: The P18 cohort study. LGBT Health, 3(5), 379–386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debell F, Fear NT, Head M, Batt-Rawden S, Greenberg N, Wessely S, & Goodwin L (2014). A systematic review of the comorbidity between PTSD and alcohol misuse. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 49(9), 1401–1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dedert EA, Resick PA, Dennis PA, Wilson SM, Moore SD, & Beckham JC (2019). Pilot trial of a combined cognitive processing therapy and smoking cessation treatment. Journal of Addiction Medicine, 13(4), 322–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desrichard O, Vallet F, Agrigoroaei S, Fagot D, & Spini D (2018). Frailty in aging and its influence on perceived stress exposure and stress-related symptoms: Evidence from the Swiss Vivre/Leben/Vivere study. European Journal of Ageing, 15, 331–338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiGrande L, Perrin MA, Thorpe LE, Thalji L, Murphy J, Wu D, Farfel M, & Brackbill RM (2008). Posttraumatic stress symptoms, PTSD, and risk factors among lower Manhattan residents 2–3 years after the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 21(3), 264–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan JE, Haberlen SA, Meanley S, Ware D, Brown AL, Siconolfi D, Brennan-Ing M, Stall R, Plankey MW, & Friedman MR (2021). Understanding patterns of healthy aging among men who have sex with men: Protocol for an observational cohort study. JMIR Research Protocols, 10(9), e25750, doi: 10.2196/25750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fluharty M, Taylor AE, Grabski M, & Munafò MR (2017). The association of cigarette smoking with depression and anxiety: A systematic review. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 19(1), 3–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frazier EL, Sutton MY, Brooks JT, Shouse RL, & Weiser J (2018). Trends in cigarette smoking among adults with HIV compared with the general adult population, United States-2009–2014. Preventive Medicine, 111, 231–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, Newman AB, Hirsch C, Gottdiener J, Seeman T, Tracy R, Kop WJ, Burke G, & McBurnie MA (2001). Frailty in older adults: Evidence for a phenotype. The Journals of Gerontology: Series A, 56(3), M146–M157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost DM, & Meyer IH (2023). Minority stress theory: Application, critique, and continued relevance. Current Opinion in Psychology, 51, 101579, doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2023.101579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gawor A, Hogervorst E, & Wilcockson T (2021). Does an acute bout of moderate exercise reduce alcohol craving in university students?. Addictive Behaviors, 123, 107071, doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2021.107071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genz A, Bretz F, Miwa T, Mi X, Leisch F, Scheipl F, & Hothorn T (2021). mvtnorm: Multivariate Normal and t Distributions. R package version 1.1–3. http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=mvtnorm. [Google Scholar]

- Gold SD, & Marx BP (2007). Gay male sexual assault survivors: The relations among internalized homophobia, experiential avoidance, and psychological symptom severity. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 45(3), 549–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenland S, Pearl J, & Robins JM (1999). Causal diagrams for epidemiologic research. Epidemiology, 10(1), 37–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groh DR, Jason LA, Davis MI, Olson BD, & Ferrari JR (2007). Friends, family, and alcohol abuse: An examination of general and alcohol-specific social support. American Journal on Addictions, 16(1), 49–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) Ryan White & Global HIV/AIDS Programs. (2019). HIV/AIDS Bureau Performance Measures. Available from: https://ryanwhite.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/ryanwhite/grants/core-measures.pdf (accessed August 11, 2022). [Google Scholar]

- Hegberg NJ, Hayes JP, & Hayes SM (2019). Exercise intervention in PTSD: A narrative review and rationale for implementation. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10:133. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemkens LG, & Bucher HC (2014). HIV infection and cardiovascular disease. European Heart Journal, 35(21), 1373–1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herek GM, Cogan JC, Gillis JR, & Glunt EK (1998). Correlates of internalized homophobia in a community sample of lesbians and gay men. Journal of the Gay and Lesbian Medical Association, 2(1), 17–25. [Google Scholar]

- Herrick AL, Stall R, Chmiel JS, Guadamuz TE, Penniman T, Shoptaw S, Ostrow D, & Plankey MW (2013). It gets better: Resolution of internalized homophobia over time and associations with positive health outcomes among MSM. AIDS and Behavior, 17(4), 1423–1430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hessol NA, Barrett BW, Margolick JB, Plankey M, Hussain SK, Seaberg EC, & Massad LS (2021). Risk of smoking-related cancers among women and men living with and without HIV. AIDS, 35(1), 101–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hicks TA, Thomas SP, Wilson SM, Calhoun PS, Kuhn ER, & Beckham JC (2017). A preliminary investigation of a relapse prevention mobile application to maintain smoking abstinence among individuals with posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Dual Diagnosis, 13(1), 15–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hile SJ, Feldman MB, Alexy ER, & Irvine MK (2016). Recent tobacco smoking is associated with poor HIV medical outcomes among HIV-infected individuals in New York. AIDS and Behavior, 20(8), 1722–1729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Højsgaard S, Halekoh U & Yan J (2006) The R package geepack for generalized estimating equations. Journal of Statistical Software, 15(2), 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Imai K, Keele L, & Tingley D (2010). A general approach to causal mediation analysis. Psychological Methods, 15(4), 309–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imel ZE, Wampold BE, Miller SD, & Fleming RR (2008). Distinctions without a difference: Direct comparisons of psychotherapies for alcohol use disorders. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 22(4), 533–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IPAQ Research Committee. (2005). Guidelines for Data Processing and Analysis of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) – Short and Long Forms, November 2005. Accessed November 1, 2021. http://www.ipaq.ki.se.

- Jeffreys M, Capehart B, & Friedman MJ (2012). Pharmacotherapy for posttraumatic stress disorder: Review with clinical applications. Journal of Rehabilitation Research & Development, 49(5), 703–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston PI, Wright SW, Orr M, Pearce FA, Stevens JW, Hubbard RB, & Collini PJ (2021). Worldwide relative smoking prevalence among people living with and without HIV. AIDS, 35(6), 957–970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahler CW, Spillane NS, Day AM, Cioe PA, Parks A, Leventhal AM, & Brown RA (2015). Positive psychotherapy for smoking cessation: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 17(11), 1385–1392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan B, Galiatsatos P, Breland A, Eissenberg T, & Cohen JE (2021). Effectiveness of ENDS, NRT and medication for smoking cessation among cigarette-only users: A longitudinal analysis of PATH Study wave 3 (2015–2016) and 4 (2016–2017), adult data. Tobacco Control, doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2020-056448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaslow RA, Ostrow DG, Detels R, Phair JP, Polk BF, Rinaldo CR Jr., for the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study. (1987). The Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study: Rationale, organization, and selected characteristics of the participants. American Journal of Epidemiology, 126(2), 310–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kearns NT, Carl E, Stein AT, Vujanovic AA, Zvolensky MJ, Smits JA, & Powers MB (2018). Posttraumatic stress disorder and cigarette smoking: A systematic review. Depression and Anxiety, 35(11), 1056–1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly MM, Sido H, Forsyth JP, Ziedonis DM, Kalman D, & Cooney JL (2015). Acceptance and commitment therapy smoking cessation treatment for veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder: A pilot study. Journal of Dual Diagnosis, 11(1), 50–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemppainen JK, Eller LS, Bunch E, Hamilton MJ, Dole P, Holzemer W, Kirksey K, Nicholas PK, Corless IB, Coleman C, Nokes KM, Reynolds N, Sefcik L, Wantland D, & Tsai Y-F. (2006). Strategies for self-management of HIV-related anxiety. AIDS Care, 18(6), 597–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimerling R, Calhoun KS, Forehand R, Armistead L, Morse E, Morse P, Clark R, & Clark L (1999). Traumatic stress in HIV-infected women. AIDS Education and Prevention, 11(4), 321–330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange T, Vansteelandt S, & Bekaert M (2012). A simple unified approach for estimating natural direct and indirect effects. American Journal of Epidemiology, 176(3), 190–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lappan S, Thorne CB, Long D, & Hendricks PS (2020). Longitudinal and reciprocal relationships between psychological well-being and smoking. Nicotine and Tobacco Research, 22(1), 18–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaRowe LR, Dunsiger SI, & Williams DM (2023). Acute exercise-induced changes in motivation and behavioral expectation for quitting smoking as predictors of smoking behavior in women. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 37(3), 475–482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeGrand S, Reif S, Sullivan K, Murray K, Barlow ML, & Whetten K (2015). A review of recent literature on trauma among individuals living with HIV. Current HIV/AIDS Reports, 12(4), 397–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR, Roberts RE, & Allen NB (1997). Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) as a screening instrument for depression among community-residing older adults. Psychology and Aging, 12(2), 277–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lüdtke O, & Robitzsch A (2021). A critique of the random intercept cross-lagged panel model. PsyArxiv. doi: 10.31234/osf.io/6f85c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch WJ, Peterson AB, Sanchez V, Abel J, & Smith MA (2013). Exercise as a novel treatment for drug addiction: A neurobiological and stage-dependent hypothesis. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 37(8), 1622–1644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Fairchild AJ, & Fritz MS (2007). Mediation analysis. Annual Review of Psychology, 58, 593–614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mäder URS, Martin BW, Schutz Y, & Marti B (2006). Validity of four short physical activity questionnaires in middle-aged persons. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 38(7), 1255–1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manthou E, Georgakouli K, Fatouros IG, Gianoulakis C, Theodorakis Y, & Jamurtas AZ (2016). Role of exercise in the treatment of alcohol use disorders. Biomedical Reports, 4(5), 535–545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]