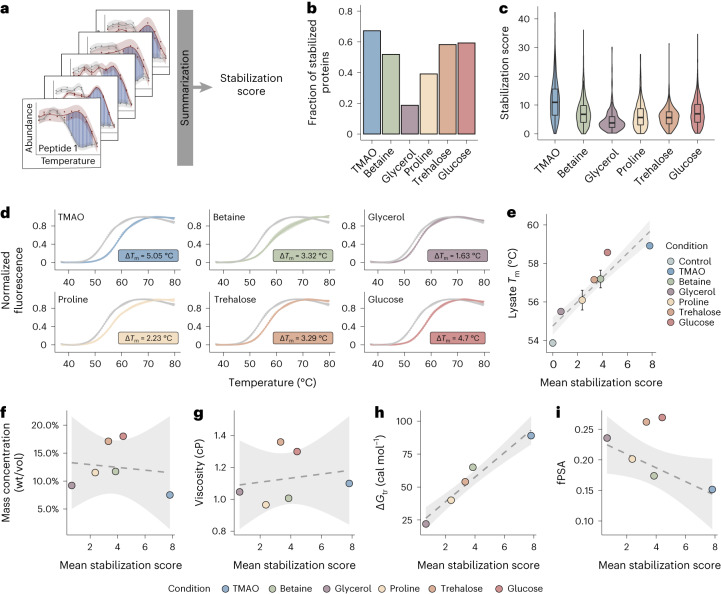

Fig. 2. Osmolytes have a global effect on protein stability.

a, Overview of the analytical procedure. A peptide-level score was calculated by summing the distances (blue) between thermal profiles in the absence (gray) and presence (red) of osmolyte at temperature values where confidence intervals do not overlap. Peptide-level scores were then combined after correcting for peptide length and overlap into a stabilization score for each protein (Supplementary Fig. 2c and Methods). b, Fraction of stabilized proteins out of all detected proteins for each osmolyte. c, Distribution of stabilization scores for proteins significantly stabilized by each osmolyte. Horizontal lines define the median, and boxes define the 25th and 75th percentiles; whiskers represent the maximum and minimum values. Each box plot represents the stabilization scores of stabilized proteins (205 proteins for glycerol, 791 for glucose, 885 for trehalose, 702 for betaine, 423 for proline and 733 for TMAO) calculated based on two LiP–MS replicates per temperature. d, Melting curves for E. coli cell lysate measured by DSF under control conditions (gray) and after the addition of osmolytes. Error bars show mean ± s.d. (n = 5 replicates per condition). e, Linear regression between DSF-measured lysate melting temperatures and mean stabilization scores for all detected proteins. Error bars show mean ± s.d. (n = 5 replicates). The shaded area represents the confidence interval of the linear fit (dashed line). f–i, Linear regression between mean stabilization score and osmolyte mass concentration (wt/vol; f), osmolyte viscosity at 25 °C (g), transfer free energy (Gtr) for backbone model substrate transferred from water to 1 M osmolyte8 (h) and fraction polar surface area8 (fPSA; i). Transfer free energy for glucose was not available in the literature. In all cases, the shaded area represents the confidence interval of the linear fit (dashed line); cP, centipoise.