Abstract

Positron Emission Tomography (PET) imaging employs positron-emitting radioisotopes to visualize biological processes in living subjects with high sensitivity and quantitative accuracy. As the most translational molecular imaging modality, PET can detect and image a wide range of radiotracers with minimal or no modification to parent drugs or targeting molecules. This article provides a comprehensive analysis of developing PET radioligands using allosteric modulators for the metabotropic glutamate receptor subtype 4 (mGluR4) as a therapeutic target for neurological disorders. We focus on the selection of lead compounds from various chemotypes of mGluR4 positive allosteric modulators (PAMs) and discuss the challenges and systematic characterization required in developing brain-penetrant PET tracers specific for mGluR4. Through this analysis, we offer insights into the development and evaluation of PET ligands. Our review concludes that further research and development in this field hold great promise for discovering effective treatments for neurological disorders.

Keywords: Metabotropic glutamate receptor 4 (mGluR4), Parkinson's disease (PD), Drug development, Radiotracer, Positron emission tomography (PET)

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Positron emission tomography (PET) is a non-invasive medical imaging technique that uses a positron-emitting radioisotope to detect pairs of high-energy photons emitted in a time-coincident manner. These photons are produced by the annihilation of a positron and an electron, and detecting them with a PET scanner allows for the generation of three-dimensional images that show the distribution of the radiotracer in the body with exceptional sensitivity (pM to nM).1-4 Therefore PET enables the imaging of low density receptor in vivo by using a target specific tracers. PET imaging is considered the most translational of all molecular imaging modalities because of its sensitivity and quantitative accuracy, as well as its ability to detect and image a wide range of radiotracers without the need for significant modifications to the parent drugs or targeting molecules. As a result, PET imaging holds promise as a critical tool for advancing our knowledge of neurological and psychiatric disorders, while addressing the unmet needs for techniques that can accurately assess neurophysiological biomarkers in living human subjects and patients.5, 6 Despite the immense potential of PET imaging, only around 50 CNS targets are currently addressed in humans according to the National Institute of Mental Health,7 while thousands of brain proteins remain unexplored.8, 9 This is largely due to the challenges of developing and acquiring radiotracers that bind specifically to their targets.10 As is known that small molecular PET radioligands often suffer from off-target binding, and it has been estimated that small molecules, including existing marketed drugs, can bind to multiple different proteins, with an average of 6.3 receptors targeted per molecule,11 adding another layer of complexity to PET tracer development. This article presents a comprehensive review of the development and current status of PET tracers for mGluR4, including their origin, historical background, recent advancements, and insights for future possibilities.

As the primary excitatory neurotransmitter in the vertebrate CNS, glutamate acts on ionotropic receptors (iGluRs) or mGluRs to mediate over 50% of all excitatory synaptic Transmission. The mGluRs, which are divided into three groups (I, II and III) with eight subtypes (mGluR1-8) based on their sequence homologies, pharmacological properties, and signal transduction pathways. The mGluRs belong to class C of the G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) superfamily, which accounts for approximately 30% of the molecular targets for currently marketed drugs. Group III mGluRs (mGluR4, 6, and 8) are predominantly expressed in the presynaptic terminals of basal ganglia (BG) circuitry. In Parkinson’s disease (PD), dopamine depletion leads to hyperactivity in this circuitry, making Group III mGluRs, particularly mGluR4, critical therapeutic targets for non-dopaminergic pharmacological interventions. A highly simplified version of regulation of basal ganglia function is demonstrated as Chart 1 (adapted from Craig W. Lindsley, Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2009, 9, 949), and the reader is referred to Braak and Del Tredicci, Exp. Neurol., 2008 for a more thorough review of the current understanding of the control of BG activity. In the Parkinson’s BG circuit, the loss of striatal dopamine produces an imbalance in the direct (striatum to GPi/SNr) and indirect pathways (striatum to GPe), leading to too much inhibitory tone from the output nuclei. mGluR4-mediated reductions in GABA (at the striatopallidal synapse) and glutamate (at the STN-SNc synapse) could restore equilibrium in the output nuclei, and the activation of mGluR4 is hypothesized to potentially avert further degeneration of SNc neurons. Recent studies have demonstrated the neuroprotective effects of an mGluR4 positive allosteric modulator (PAM) in both cultured neurons and in vivo,11, 12 as well as potential therapeutic benefits in rodent models of PD.13, 14

Chart 1.

A simplified model of the basal ganglia (BG) circuit comparing normal physiology with PD. Excitatory (glutamatergic) projections are shown from the STN and SNc (top) and inhibitory (GABAergic) projections are shown from the D2 Striatum D1, SNc (bottom), GPe and GPi/SNr. Top. In the normal BG circuit, direct (striatum to GPi/SNr) and indirect (striatum to GPe) projections to the output nuclei are balanced by striatal dopaminergic tone. D1 receptor-containing neurons stimulate transmission through the direct pathway and D2 receptor-containing neurons inhibit transmission through the indirect pathway. These circuits converge at the GPi/SNr with a balance of inhibitory (via direct pathway) and excitatory (via indirect pathway) to properly regulate inhibitory output to the thalamus. mGluR4 (black circle) is localized and active at the synapse between the striatum and GPe (striatopallidal synapse) as well as synapses between the STN and SNc. Bottom. In the Parkinson’s BG circuit, the loss of striatal dopamine produces an imbalance in the direct and indirect pathways leading to too much inhibitory tone from the output nuclei. mGluR4-mediated decreases in GABA (striatopallidal synapse) and glutamate (STN-SNc synapse) are hypothesized to restore balance to the output nuclei and possibly prevent further degeneration of SNc neurons via excitotoxic mechanisms. GPE=external segment of the globus pallidus, GPi=internal segment of the globus pallidus, STN= subthalamic nucleus, SNr=substantia nigra pars reticulata, SNc= substantia nigra pars compacta (Adapted from Lindsley, Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2009, 9, 949 and Wichmann, Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 1996, 6, 751).

It is challenging to develop highly selective orthosteric ligands for individual mGluR subtypes due to the high conservation of the glutamate binding site.15-18 In addition, the orthosteric ligands are usually based on polar amino acid derivatives which usually do not cross BBB.19, 20 Allosteric modulators, which bind to sites distinct from the highly conserved glutamate binding site of mGluRs, have recently drawn intense attention in new drug development.21, 22 These molecules regulate positively or negatively the affinity of the orthosteric ligand, providing a potentially safer and more specific alternative to competitive orthosteric ligands.

Over the past two to three decades, several pharmaceutical companies have focused on developing allosteric modulators for the mGluR4 receptor through extensive research in medicinal chemistry. Different PAM ligands have been developed by these companies, including Addex,23-25 Merck,25-27 Lundbeck,28-30 Prexton Therapeutics,31, 32 Domain Therapeutics,33 Boehringer Ingelheim/Evotec34, 35 as well as Vanderbilt University.30, 31, 36-39 This effort has led to the discovery of multiple chemotypes of mGluR4 PAM in vivo tool compounds. The structural classes of these molecules are wide-ranging, from triaryl amines,40 cyclohexyl amides,28 picolinamides,41 and pyrazolo[4,3- b]pyridines,36, 42 which speaks to the variability in the allosteric binding sites of the receptor.

The development of PET tracers for in vivo brain imaging often hinges on the availability of high-affinity small-molecule ligands with established structure-affinity relationships, as these are crucial for rigorous drug development and serve as a key starting point for PET probes. The development of radiotracers is a complex process that requires expertise in disease-related biological targets, chemical synthesis and radiolabeling techniques, in vitro assay development, animal handling and models, PET imaging acquisition, and image analysis. Given the interdisciplinary nature of this field, it has been particularly challenging to establish a uniform set of standards for evaluating radiotracers and achieving a shared understanding among experts and non-experts alike. As a result, the assessment of radiotracers remains a complex and ongoing endeavor that requires collaboration across multiple disciplines.

Despite the significant progress that has been made in the development of PET tracers for mGluR4, there are still several challenges that need to be addressed before these tracers can be used in clinical practice. These challenges include improving the sensitivity and specificity of the radiotracers, optimizing the radiolabeling methods for clinical-scale production, and establishing the safety and efficacy of the tracers in human subjects. Nevertheless, the ongoing efforts to develop PET tracers for mGluR4 hold promise for advancing our understanding of neurological and psychiatric disorders, and for developing new therapies that target mGluR4.

The distribution pattern and expression level of mGluR4 protein are of significant importance, yet none of the radioligand studies to date have clearly disclosed these details. Brain autoradiography experiments in rats, using in situ hybridization with oligodeoxyribonucleotide probes and an orthosteric radioligand, have shown that mGluR4 is expressed heterogeneously across different regions, with high levels noted in the cerebellum.43 , 44 By comparing the in situ hybridization results of mGluR4 and mGluR5, we estimate that the concentration of the target protein (Bmax) value for mGluR4 in the thalamus is less than 20 nM, while in the cerebellum it ranges from 50 to 100 nM.45 For radioligand development, it is generally required that the binding potential (BP = Bmax/Kd), predicted from in vitro measurements, be greater than 5,46 or even much higher, therefore, for effective imaging, the radioligand for mGluR4 might need an affinity as low as < 4-5 nM.

Our primary objective is to provide a comprehensive summary of available chemotypes of ligands that target mGluR4, including an analysis of their structure-activity relationship (SAR) and potential for PET probe development. In addition, we will evaluate the current state-of-the-art PET probes based on our experience and insights. Our goal is to offer valuable insights into the development of new PET probes for mGluR4, which could aid in the diagnosis and treatment of neurological disorders such as PD. This work aims to provide a detailed understanding of PET tracer development for mGluR4, with the potential to benefit the scientific community in the diagnosis and treatment of neurological disorders such as PD.

2. Chemotypes and available radioligands for mGluR4

2.1. The first three chemotypes discovered in 1990s.

In the 1990s, scientists endeavored to identify ligands that could modulate mGluRs without relying on amino acid derivatives. CPCCOEt,47 PHCCC,47 MPEP,48 and SIB-189349 are three early examples of non-amino acid-containing chemotypes that act as allosteric modulators targeting mGluR1, 4 and/or 5 (Figure 1). However, these compounds are unsuitable for radioligand development without modification. Further modifications have led to the development of some subtype-selective modulators with impressive effects: a) Modification of MPEP led to mGluR5 modulators (5 and 6); b) modification of (−)-PHCCC led to mGluR4 PAMs ligands 7 and 8 (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

The earliest mGluR allosteric modulators.

Figure 2.

The potent mGluR4 PAMs derived from PHCCC.

2.1.1. PHCCC derived compounds might be promising for mGluR4 PET tracers

The racemic form of CPCCOEt (1) and PHCCC (2) were initially reported as mGluR1 antagonist.47 However, (−)-PHCCC (5), the enantiomer of PHCCC, was later discovered to have single-digit μM mGluR4 PAM activity.11 Further studies on the SAR of PHCCC analogs indicated that the oxime moiety was crucial for its activity, and modification of the east ring was quite sensitive to modification. Replacement of the east ring with a 2-pyridine group resulted in highly potent mGluR4 PAM 8.50 Compound 8 (VU0359516) was devoid of activity against all the other mGluR subtypes tested at 10 μM, making this chemptype promising for PET tracer development. However, to date, no radioligand has been developed from this chemotype, suggesting that further exploration of this compound type may be worthwhile.

2.1.2. Chromenone oxime series and the discovery of PXT002331

It appears that the (−)-enatiomer of PHCCC is critical, as compound 9 is inactive (Figure 2). Research conducted by Domain Therapeutics and Prexton Therapeutics has led to significant advancements, focusing on the medicinal chemistry work centered around (−)-PHCCC. They have discovered that substituting the cyclopropyl ring with a double bond and constricting the amide moiety into bicyclic heterocycles leads to chromenone oxime derivatives with potent mGluR4 PAM activities.32 In addition, compound 10 (PXT002331) exhibited no activity on NMDA, AMPA, kainate, group I (mGluR1 and 5), or group II (mGluR2 and 3) mGluRs up to 10 μM. However, it demonstrated activity within group III (mGluR6, 7, and 8), displaying selectivity that was 15-, 110-, and 50-fold higher for mGluR4 compared to mGluR6, mGluR7, and mGluR8, respectively.

The steep structure-activity relationship (SAR) observed in the east ring of the chromenone oxime series poses some challenge, nevertheless, modifications to the west ring of chromenone oxime derivatives, as illustrated in Figure 2, have shown relative tolerance.51 Furthermore, Prexton Therapeutics has made significant progress in the development of PXT002331, which has entered clinical trials in Europe for the treatment of PD. PXT002331 has shown impressive safety results and promising clinical improvements in early trials for the treatment of PD. However, the compound failed to sufficiently distinguish itself from placebo to meet the study endpoints, indicating that further research and development are needed to optimize its efficacy.52, 53 Nonetheless, these results provide valuable insights into the potential therapeutic benefits of mGluR4 modulation for the treatment of PD and other related conditions.

2.1.3. Quinazolinone derivatives

Although it has been established that oximes are essential for mGluR4 PAM activity in PHCCC derivatives, a recent patent has demonstrated that quinazolinone derivatives (such as compound 11) can also serve as potent mGluR4 PAMs (< 1000 nM).54 This highlights the importance of continued SAR studies and the potential for discovering novel mGluR4 PAMs with diverse structural scaffolds (Figure 2).

Both oxime and quinazolinone derivatives have demonstrated potential as suitable chemotypes for the development of mGluR4 PET tracers. However, to date, there have been no reports on the development of these chemotypes for this purpose. We hope that radiochemists will further explore and develop these chemotypes for the development of mGluR4 PET tracers. Moreover, the tolerance of this chemotype to modification makes it promising for the development of single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) and fluorescent ligands, offering a broad range of imaging modalities for the exploration of mGluR4 biology and the development of novel therapies.

2.1.4. MPEP and SIB-1893 derivatives

MPEP and SIB-1893 have been reported as mGluR5 negative allosteric modulators (NAMs) with weak mGluR4 PAM activity.55, 56 It is worth noting that [18F]FPEB and [18F]PSS232, which are derived from MPEP, are currently available for human brain imaging of mGluR5 (Figure 1). Overall, these two chemotypes are currently unsuitable for mGluR4 imaging.

2.2. Cyclohexyl amide derivatives

Cyclohexyl amide 12 (VU0155041) is an mGluR4 PAM (Figure 3), which was discovered through High-Throughput Screening (HTS) in early 2000s.57 Compared to (−)-PHCCC, compound 12 is eight times more potent and does not cause cross-talk with other mGluR subtypes. Additionally, it has demonstrated efficacy in preclinical models of PD.57, 58 However, the SAR reported for this chemotype was unremarkable, its shallow SAR limits its potential as both a drug candidate and a PET probe for development.57, 59 Although compound 12 has promising pharmacological properties on its own, no PET probes have been developed from this chemotype to date. Without further SAR disclosure containing either fluorine, iodine, and/or methoxy groups, it is unlikely to be successful in the future. Furthermore, it is important to note that compound 12 does not compete with (−)-PHCCC binding, indicating that it may bind to a different allosteric site than (−)-PHCCC.30

Figure 3.

Shallow SAR of cyclohexyl amide derivatives.

2.3. N-phenylpicolinamide derivatives

Since its discovery in 2009,41 this chemotype has undergone extensive study, revealing clear SAR data. Maintaining the right-hand aniline as 3,4-dichlorophenyl, the authors initially explored various aryl, cycloalkyl, and heteroaryl substituents on the west ring. Compounds with five-membered heterocycles, cyclohexyl, and phenyl groups were found to be inactive (>10 μM). However, introducing a 2-pyridyl group restored good potency (Figure 4, compound 15), while the 2-pyrazine compound 16 lost its activity.41 Subsequent modifications on the east ring of 2-pyridylamide compounds resulted in a series of potent compounds, indicating that the east ring showed tolerance to modification (Figures 4-9). As a result, this chemotype shows great promise for PET tracer development, and in fact, all the published radioligands with brain imaging data have been based on this chemotype (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Simple N-phenylpicolinamide derivatives.

Figure 9.

A new mGluR4 18F tracer showing promising in vitro binding.

2.3.1. SAR of simple N-phenylpicolinamide derivatives

With the potent mGluR4 PAM ligand 17 (ML128) discovered via calcium mobilisation assays (EC50 = 110 nM),41 the first mGluR4 radioligand [11C]17 (Figure 5) was then characterized and reported in 2013 by Kil et al.60 The radiosynthesis involved methylation of the phenol precursor 18 (Figure 5) using [11C]iodomethane ([11C]CH3I) with 5 M potassium hydroxide (KOH) in N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF) at 90°C for 5 minutes, resulting in a decay-corrected radiochemical yield (RCY) of approximately 27.7 ± 5.3% (n = 5) based on the radioactivity of [11C]CO2. The radiochemical purity of [11C]17 was >99%, with a molar activity of 188.7 ± 88.8 GBq/mol (n = 4) at the end of synthesis (EOS). Additionally, [3H]17 was prepared using a similar method for the competitive binding affinity assay (IC50 = 5.1 nM), crucial for developing PET ligands, as EC50 values in functional assays don’t always correlate closely to binding affinity values.61

Figure 5.

Improved N-phenylpicolinamide derivatives (Images are adapted from Kil, Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2016, 26, 133).

Being the first PET radioligand to readily cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB), [11C]17 PET brain images exhibited high activity accumulation in regions like the hippocampus, striatum, thalamus, olfactory bulb, and cerebellum.60 The time-activity curves (TAC) of [11C]17 showed initial peak uptake in the cerebellum (< 0.3%ID/g) within 2 minutes, followed by rapid washout. This underscores the potential for enhancing in vivo imaging efficacy, leading to the design and characterization of new tracers in subsequent research. Given the prevanlence of O-demethylation in metabolic pathways, modifications were made by replacing oxygen with sulfur in the methoxy groups, leading to the synthesis of several sulfur-containing compounds (19 and 20 in Figure 5). These compounds underwent evaluation for both microsomal stability and binding affinity using [3H]ML128. Notably, both sulfur containing compounds showed increased binding affinity compared to ML128, Compound 20 showed slightly improved metabolic stability as well. Of significance is the observation that [11C]20 showed higher cerebellum uptake and yielded better imaging results (Figure 5). Due to the absence of clear scale bars in some parts of the original papers, we hope that the authors conducted the experiments head-to-head and processed the images under uniform settings. This approach bolsters the reliability of their findings.

As mentioned earlier, Prexton Therapeutics has made significant progress in the development of an mGluR4 PAM called PXT002331. This compound has successfully entered clinical trials in Europe for the treatment of PD. However, this compound lacks a suitable handle for labeling with both 11C and 18F isotopes. Alternatively, evaluating it using the existing mGluR4-specific radioligand could be considered, and [11C]20 as the superior ligand at that time was chosen as the radioligand. At the beginning, Prexton Therapeutics approached us with a collaboration proposal to conduct in vivo evaluation of PXT002331 using the radioligand [11C]20, and this initiative is based on the assumption that PXT002331 could potentially replace this radioligand. For that study, we were asked to make the thiophenol precursor and prepare samples for the blocking studies.62 Without satisfactory results, subsequently, Pexton Therapeutics published the monkey imaging data in collaboration with the Karolinska institutet. From that study, there was no blocking effect by PXT002331 in the PET brain imaging. In addition, the SUV values at the peak under the blocking condition were significantly higher than those at the baseline condition.63 Amazingly, [11C]20 was later used in a separate clinical trial (gov Identifier: NCT03826134) by H. Lundbeck A/S, where it was renamed as [11C]PXT012253. This trial marked a significant milestone as the first clinical trial involving an mGluR4 PET tracer. However, there has been no disclosure of human data likely due to concerns arising from primate data. In addition, there have also been no in vitro binding assays about how PXT002331 could displace [11C]PXT012253. In other words, the characterization was just based on the assumption that both compounds bind to the same allosteric site of mGluR4 and we do hope more careful characterization could have been carried out before moving to clinical trials.

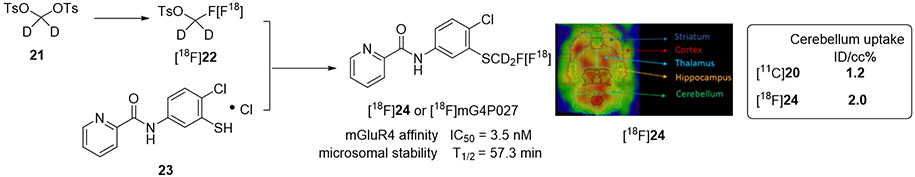

The development of a PET tracer for imaging mGluR4 using 18F is of significant importance due to the favorable physical and nuclear properties of this radionuclide. Compared to 11C, 18F has a longer half-life, allowing for more extensive imaging protocols and thorough kinetic studies. Additionally, the low positron energy resulting from 18F decay enables high-resolution imaging. As a result, 18F is frequently preferred over 11C. Furthermore, the use of 18F allows for accurate metabolic and plasma analysis, making it an ideal choice for PET tracer development. To achieve this goal, we further replaced the methylthio group with a dideuterium-fluoromethylthio moiety, resulting in the development of compound 21. Firstly, binding assays were conducted using the tritium-labeled radioligand [3H]17 to evaluate the binding affinities of compounds 17, 20 and 24 to mGluR4 in parallel. This assay was carried out with mGluR4-transfected CHO cells, involved increasing the concentration of the test compounds from 0.01 nM to 10 μM in the presence of 2 nM [3H]17, providing IC50 values as binding affinities. Moreover, the in vitro liver microsomal stability of compounds 17, 20 and 24 was also assessed by incubating them in rat liver microsomes with NADPH cofactor. This probe exhibits similar binding affinity to its counterparts (3.5 nM), with the added benefit of improved metabolic stability (57.3 min) and better brain uptake. It stands out as the most stable 18F probe developed thus far. However, the radiolabeling process presents several significant challenges, which must be overcome to facilitate its clinical application.64

The reported radiolabeling process involved a laborious two-step manual procedure with two preparative HPLC steps (Figure 6), necessitating a significant amount of 18F and posing considerable safety concerns. The two-step radiosynthesis of [18F]24 was reported by maual labeling, which took 2.5–3.5 h with a 11.6% ± 2.9% radiochemical yield (RCY, n = 7, decay corrected). The radiochemical purity of [18F]24 was >99% and the molar activity was 84.1 ± 11.8 GBq/μmol (n = 7). To address these issues, we have conducted comprehensive analyses of the radiolabeling process and are actively exploring means of automation to facilitate its use in an Investigational New Drug Application (IND) for human studies.65

Figure 6.

An 18F PET tracer with improved metabolic stability.

2.3.2. SAR of East Ring of N-phenylpicolinamide derivatives

In this particular chemical class, the east ring of N-phenylpicolinamide derivatives is rarely amenable to modification. Amides,66 sulfonamide derivatives,67 and phthalimides68 have been reported as potent mGluR4 PAMs, suggesting some degree of flexibility in this framework. Intriguingly, bulky substituents do not seem to significantly impact the compound’s activity, 68 making it relatively facile to develop both PET and fluorescent ligands (Figure 7). Notably, recent research into bivalent tethered ligands that exhibit dual mGluR2 and mGluR4 PAM activities provides a promising avenue for future modification of this chemical class,69 raising hope for improving the in vivo behavior of these ligands through modifications to the east ring.

Figure 7.

Derivatives from the modification of the east ring.

The first 18F mGluR4 PET tracer, published in 2014, was based on a phthalimide derivative (Figure 8), [18F]30.61 The radiolabeling process was straightforward from the precursor 37, achieved through the nucleophilic reaction of [18F]fluoride in DMSO at 120 °C. The average decay corrected radiochemical yield (RCY) of [18F]30 was 16.4 ± 4.8% (n = 4) with high radiochemical purity (> 98%). The molar activity of [18F]30 at the end of synthesis (EOS) was 233.5 ± 177.8 GBq/μmol (n = 4). However, it was observed that the phthalimide moiety was not very stable and underwent hydrolysis under neutral conditions evidenced by LC-MS, making it less appealing for clinical applications. To mitigate this issue, the final formulation of the tracer involved a 0.1 M citrate buffer (pH = 4) with 10% ethanol, which effectively prevented hydrolysis. Despite this, no additional tracers have been developed from this phthalimide class thus far. While chemical modification could potentially address the instability associated with phthalimides, even the simple amide might be a more viable alternative.

Figure 8.

The first mGluR4 18F tracer and its in vivo behavior.

It should be pointed out that in a particular study of [18F]30, there was no significant blocking effect observed even when using a known mGluR4 PAM ligand at a high dose of 10mg/kg. Although the imaging showed heterogeneous distribution in coronal sections, no sagittal imaging was presented in the paper. Although the TACs derived from different areas of the monkey brain demonstrated fast accumulation and reversible binding of [18F]30, there was no clear preference in distribution in different brain regions. Taken together, these findings suggest that this tracer may not be suitable for in vivo imaging of mGluR4.

While this chemotype shows great promise, as evidenced by our recent study (Figure 9), it is important to note that further research is needed to fully assess the efficacy and safety of the compound in vivo. In our study, we designed and radiolabeled a picolinamide derivative, 38, using Sulfur(VI) Fluoride Exchange (SuFEx) click chemistry, achieving a radiolabeling yield of over 90% with a simple mixing process at room temperature in just a few seconds. Autoradiographic analysis of [18F]38 showed that the compound accumulated the most radioactivity in the cerebellum of rat brains, where mGluR4 is known to be highly expressed. Importantly, a significant blocking effect was observed using the known mGluR4 PAM ligand mG4P012, indicating that compound 38 is an mGluR4 PAM ligand binding to the same binding sites as mG4P012. These findings suggest that compound 38 is a promising candidate for further development as a mGluR4 PAM and imaging probe. It should be noted that many of the previous studies published have skipped in vitro autoradiography studies and directly proceeded to in vivo animal imaging. This omission may have limited the accuracy and reliability of the results, as in vitro studies can provide valuable insights into the binding properties and specificity of the radiotracer.

This study has been accepted as an abstract at the 2023 SNMMI meeting (Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging),70 and we are currently in the process of preparing a full paper for publication with thorough characterization of this ligand.

2.3.3. Pyrazolo[4,3-b]pyridine derivatives

Due to the in vivo instability of the picolinamide scaffold, primarily resulting from the instability of its amide bond, various efforts have been made to improve its stability. One such approach involved replacing the picolinamide scaffold’s head groups with heterocycles, which resulted in the discovery of a series of heterocyclic derivatives,36 most of which exhibited significant or complete loss of activity. However, the introduction of the pyrazolo[4,3-b]pyridine group was a breakthrough, leading to the discovery of potent mGluR4 PAMs like 40 (Figure 10).36 Despite its promising activity, compound 40 was found to be a strong inhibitor of CYP1A2, and did not show significant improvement in vitro pharmacokinetic properties. Although 40 was found to be inactive to a wider panel of GPCRs, enzymes, ion channels, nuclear hormone receptors and transporters, it did show potent monoamine oxidase-B activity (MAO-B, 330 nM). Inhibitors of MAO-B are clinically employed in Parkinson’s disease for symptomatic purposes, making 40 as a good therapeutic candidate for PD. However, the robust MAO-B activity presents a challenge in selective brain imaging of mGluR4.

Figure 10.

Pyrazolo[4,3-b]pyridine derivatives as potent mGluR4 PAMs.

While building on the promising pyrazolo[4,3-b]pyridine motif for mGluR4 PAM activity, further optimization of this chemotype of the east ring led to the discovery of several potent derivatives, including a number of indazole, indole and other polyaza-systems. Several derivatives were discovered to be inactive or exhibited a loss of activity. The optimization campaign led to compounds 41 and 42 (Figure 10), which showed resolved issues of CYP1A2 induction, and 41 was inactive against all CYP enzymes studied (CYP1A2, 3A4, 2C9, 2D6: >30 μM).39, 71, 72 In addition, 41 was evaluated in mGluR selectivity panel, and it was inactive against all the other mGluR subtypes (mGluR6 was not included). The author noted that while these potent derivatives also showed some solubility issues, which could hinder their application in drug development, they may not pose a significant obstacle for PET tracer development given the microdosing approach used in nuclear medicine. Recently, a new report on compound 43 claimed to address these problems, however the selectivity was not disclosed.73 While all these compounds belong to the same chemotype, which holds some promise for PET radioligand development, it has not yet been extensively explored in this regard. Therefore, research groups are strongly encouraged to investigate one or two of the most potent compounds within this category.

2.4. Thiazolopyrazole derivatives

Addex Pharmaceuticals74 and Lundbeck Research29 announced the discovery of a new class of PAMs for mGluR4, consisting of a series of thiazolopyrazole derivatives (Figure 11). ADX88178 (44) is reported to be selective for mGluR4, potent (EC50 = 4 nM), orally available, and brain penetrant, showing efficacy in a number of rodent models of Parkinson’s disease.75 In vitro studies revealed that ADX88178 demonstrated no activity on mGluR1, mGluR2, mGluR3, mGluR5, mGluR7, or gamma-aminobutyric acid B (GABAB) receptors at concentrations up to 30 μM. The compound ADX88178 was found to display agonist activity at mGluR6 with an EC50 value greater than 10 μM. However, it showed PAM activity at mGluR8 with an EC50 of 2.2 μM Lundbeck's tricyclic thiazolopyrazole derivatives are highly potent mGluR4 PAMs, displaying significant selectivity over mGluR1, mGluR2, mGluR3, mGluR5, and mGluR7 (EC50 > 10 μM). Furthermore, an in vivo study evaluating brain exposure in rats demonstrated a brain/plasma ratio of 1 at one hour following subcutaneous dosing of one compound in this chemotype, indicating excellent penetration of the blood-brain barrier.29

Figure 11.

Thiazolopyrazole derivatives as potent mGluR4 PAMs.

Both thiazolopyrazole derivatives hold promise for PET tracer development according to the reported data. However, while [11C]ADX88178 was successfully labeled by Fujinaga et al.,76 both in vitro and in vivo data indicated poor mGluR4 binding. In addition, radioactive accumulation in the autoradiography was identified in some negligible regions, such as the cerebral cortex and midbrain, indicating nonspecific or off-target binding. Notably, no animal imaging was disclosed in that study (Figure 12). We also successfully labeled compound [18F]46 in high purity (>99%), and in vitro autoradiography revealed a heterogeneous distribution with very strong signal at cerebellum.77 However, the PET imaging studies of [18F]46 exhibited low brain-penetration (SUV < 0.5%).77 Taken together, both studies suggest that this chemotype may not be ideal for PET imaging probes.

Figure 12.

Thiazolopyrazole PET probe for mGluR4.

2.5. A few chemotypes with less potency

Although there are several additional chemotypes 47,78 48,34 49,79 5079 with lower potency that were not discussed in detail due to limited availability of both activity and SAR data (Figure 13), their significance should not be underestimated. The challenges posed by the shallow SAR for all mGluRs make it difficult for radiochemists to work on these chemotypes, because most radiochemistry labs lack the necessary activity assays. However, we believe that closer collaboration between labs with functional assays and radiochemistry settings can help to bridge this gap. Therefore, we strongly encourage researchers to establish partnerships and work together towards a more comprehensive understanding of mGluR allosteric modulators to fulfill the usefulness of radiochemistry in drug development.

Figure 13.

A few more mGluR4 PAM chemotypes with low potency.

3. Exploring Promising Chemotypes and Their Relationships

As mentioned, developing highly selective orthosteric ligands for individual mGluR subtypes is challenging due to the conservation of the glutamate binding site and the polar nature of amino acid derivatives used as ligands, limiting their ability to cross the BBB. Allosteric modulators, binding to distinct sites from the glutamate binding site, have gained significant attention in drug development due to their lessened evolutionary pressure for conservation. In the pursuit of allosteric modulators, scientists observed that even minor structural changes (as subtle as altering a single atom) can cause a "molecular switch" in mGluR allosteric ligands, altering pharmacological mode or subtype selectivity.

Over the past few decades, pharmaceutical companies have focused on developing allosteric modulators for mGluR4 through extensive medicinal chemistry research. Various PAM ligands have emerged from these efforts, leading to the discovery of diverse chemotypes of mGluR4 PAM in vivo tool compounds. These chemotypes, including triaryl amines, cyclohexyl amides, picolinamides, and pyrazolo[4,3-b]pyridines, showcase the receptor's allosteric binding site variability. We analyze these chemotypes to pinpoint promising candidates for radioligand development, noting that some chemotypes are still in early stages and require further maturation, while others share close similarities with each other.

We exclude the discussion of MPEP and SIB-1893 derivatives (3-6), Cyclohexyl amide derivatives (12 and 13), and several chemotypes (47-50) from section 2.5. due to their immaturity for radioligand development, owing to either low potency or insufficient SAR data. Thiazolopyrazole derivatives (44 and 46) are potent mGluR4 PAMs. However, they exhibit very low brain exposure, rendering them unsuitable for tracer development.

Some of the promising chemotypes are outlined in Figure 14. Among these, N-phenylpicolinamide derivatives (17, 20, 24, 30, 38) stand out as the most extensively studied, with the development of both 11C and 18F ligands. Radioligand [11C]20 has even progressed to the clinical phase for human studies, although specific data remains undisclosed. Compound 24, with its improved metabolic stability and binding affinity, demonstrates considerable promise for in vivo brain imaging, prompting the authors to apply for an IND for clinical development. However, the imaging data of rat brain reveals wide distribution in the brain, and no autoradiographic studies have been disclosed to illustrate binding specificity, a crucial factor in tracer development. While the new tracer [18F]38 exhibits some promising binding patterns compared to IHC data, further meticulous studies are necessary for in vivo imaging. Despite the potential shown by N-phenylpicolinamides as a promising chemotype, advancing to clinical studies requires more thorough investigations.

Figure 14.

Representative PET tracers and selected potential chemotypes for mGluR4.

Pyrazolo[4,3-b]pyridine derivatives derived from N-phenylpicolinamide via amide head group cyclization, demonstrate potent mGluR4 PAM activity and exceptional subtype selectivity, yet they remain unexplored in radiolabeling endeavors. Cyclization resulted in compound 40, a highly potent mGluR4 PAM, and its derivatives show tolerance to modifications on the ester ring, making them promising candidates for radioligand development. Despite their potential, no radioligands have been developed from this group to date.

The PHCCC class (8) and its derivatives, such as chromenone oxime (10) and quinazolinone derivatives (11), are potent mGluR4 PAMs. Among them, the chromenone oximes stand out with substantial SAR data available, making them highly promising candidates for radioligands. Originating from PHCCC, their development traces back to the 1990s, yet no radioligands have been developed from this group thus far. We look forward to seeing research groups take on the challenge of developing radioligands from either pyrazolo[4,3-b]pyridine or chromenone oxime chemotypes.

4. Conclusions and perspectives

In conclusion, mGluR4 has been extensively studied in recent years, and it shows great promise as a therapeutic target for a variety of neurological disorders. The development of more specific and selective allosteric modulators of mGluR4 has led to the discovery of several chemotypes of modulators with potent activity and improved pharmacokinetic properties. However, further optimization and refinement of these compounds are still necessary to improve their efficacy and specificity, as well as to overcome issues with solubility and BBB penetration based on our PET imaging studies.

PET imaging of mGluR4 is of particular interest in the field of neuroimaging and drug development, as it could provide valuable insights into the role of mGluR4 in neurological disorders and help identify potential therapeutic targets. However, currently available tracers either lack specificity or are unable to cross the BBB, highlighting the need for further research and development of more specific and BBB-permeable tracers. With continued research and collaboration among scientists and researchers in the field, it is hoped that the development of effective treatments for neurological disorders will be accelerated, improving the lives of millions of people worldwide.

Significance.

Both drug development and disease diagnosis can benefit significantly from PET in vivo brain imaging.

The development of PET-specific radiotracers for in vivo brain imaging often relies on high-affinity small-molecule ligands with well-established structure-affinity relationships and requires careful characterization of the radioligands.

With this perspective, we aim to highlight the challenges, potential, and promise associated with developing mGluR4 radiotracers for brain imaging.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

J.F Wang acknowledges financial support from the NIH/NIA K25AG061282.

ABBREVIATIONS USED

- PET

Positron Emission Tomography

- mGluR4

Metabotropic Glutamate Receptor 4

- PD

Parkinson's disease

- iGluRs

ionotropic receptors

- BG

basal ganglia

- PAM

positive allosteric modulator

- SAR

structure-activity relationship

- SPECT

single-photon emission computed tomography

- NAM

negative allosteric modulator

- IND

Investigational New Drug Application

- TAC

time-activity-curve

- SuFEx

Sulfur(VI) Fluoride Exchange

Biographies

Junfeng Wang holds Bachelor's and Master's degrees in Organic and Medicinal Chemistry from Zhengzhou University, China. He subsequently earned his Ph.D. in Chemical Biology from Peking University, China. Since 2010, he has been actively engaged in molecular imaging research in the USA, gaining extensive experience in designing and characterizing fluorescent probes, Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) contrast agents, and Positron Emission Tomography/Single Photon Emission Computed Tomography (PET/SPECT) radioligands. Currently, his research interests focus on developing small molecules, peptides, and nanobodies for molecular imaging and radiation therapy applications. Upon establishing his own laboratory, he spearheaded the development of PET radioligands at Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, establishing a robust pipeline for their advancement.

Yingbo Li earned her Ph.D. in Biomedical Sciences from the University of Macau, China. She specializes in chemical biology, cell biology, and animal models. Currently, she is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Molecular and Cellular Pharmacology at Peking University. Her research focuses on the development of site-specifically labeled nanobodies for PET imaging and radioimmunotherapy through genetic code expansion.

Georges El Fakhri earned his Ph.D. in Medical Physics from the University of Paris XI. He is an internationally recognized expert in quantitative SPECT, PET-CT, and PET-MR. He has served as a Professor of Radiology at Harvard Medical School and was the founding Director of the Gordon Center for Medical Imaging. Additionally, he directed the Massachusetts General Hospital PET Core and co-directed the Division of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging. Currently, he is a Professor at Yale University, where he serves as the Director of the Yale PET Center and Vice Chair of Scientific Research.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ghosh KK; Padmanabhan P; Yang C-T; Ng DCE; Palanivel M; Mishra S; Halldin C; Gulyás B Positron emission tomographic imaging in drug discovery. Drug Discovery Today. 2022;27(1):280–91. Drug. Discov. Today. 2022, 27 (3), 280–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abraham T; Feng J Evolution of brain imaging instrumentation. Semin. Nucl. Med 2011, 41 (3), 202–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pike VW PET radiotracers: crossing the blood–brain barrier and surviving metabolism. Trends. Pharmacol. Sci 2009, 30 (8), 431–440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holland JP; Liang SH; Rotstein BH; Collier TL; Stephenson NA; Greguric I; Vasdev N Alternative approaches for PET radiotracer development in Alzheimer's disease: imaging beyond plaque. J. Labelled Comp. and Radiopharm 2014, 57 (4), 323–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eriksson L; Kanno I Blood sampling devices and measurements. Med. Prog. Technol 1991, 17 (3-4), 249–257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hargreaves RJ; Rabiner EA Translational PET imaging research. Neurobiol. Dis 2014, 61, 32–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.CNS Radiotracer Table https://www.nimh.nih.gov/research/research-funded-by-nimh/therapeutics/cns-radiotracer-table.shtml (accessed Dec 22nd, 2023).

- 8.Martins-de-Souza D; Carvalho PC; Schmitt A; Junqueira M; Nogueira FCS; Turck CW; Domont GB Deciphering the human brain proteome: characterization of the anterior temporal lobe and corpus callosum as part of the Chromosome 15-centric Human Proteome Project. J. Proteome Res 2014, 13 (1), 147–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van de Bittner GC; Ricq EL; Hooker JM A philosophy for CNS radiotracer design. Acc. Chem. Res 2014, 47 (10), 3127–3134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matthews PM; Rabiner EA; Passchier J; Gunn RN Positron emission tomography molecular imaging for drug development. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol 2012, 73 (2), 175–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maj M; Bruno V; Dragic Z; Yamamoto R; Battaglia G; Inderbitzin W; Stoehr N; Stein T; Gasparini F; Vranesic I; et al. (−)-PHCCC, a positive allosteric modulator of mGluR4: characterization, mechanism of action, and neuroprotection. Neuropharmacology 2003, 45 (7), 895–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Battaglia G; Busceti CL; Molinaro G; Biagioni F; Traficante A; Nicoletti F; Bruno V Pharmacological activation of mGlu4 metabotropic glutamate receptors reduces nigrostriatal degeneration in mice treated with 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1, 2, 3, 6-tetrahydropyridine. J. Neurosci 2006, 26 (27), 7222–7229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hopkins CR; Lindsley CW; Niswender CM mGluR4-positive allosteric modulation as potential treatment for Parkinson’s disease. Future Med. Chem 2009, 1 (3), 501–513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hefti F. Drug discovery for nervous system diseases: Wiley-Liss; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marino MJ; Hess JF; Liverton N Targeting the metabotropic glutamate receptor mGluR4 for the treatment of diseases of the central nervous system. Curr. Top. Med. Chem 2005, 5 (9), 885–895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marino MJ; Conn PJ Glutamate-based therapeutic approaches: allosteric modulators of metabotropic glutamate receptors. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol 2006, 6 (1), 98–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Niswender CM; Jones CK; Conn PJ New therapeutic frontiers for metabotropic glutamate receptors. Curr. Top. Med. Chem 2005, 5 (9), 847–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang Z-Q Agonists and antagonists for group III metabotropic glutamate receptors 6, 7 and 8. Curr. Top. Med. Chem 2005, 5 (9), 913–918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thomsen C; Kristensen P; Mulvihill E; Haldeman B; Suzdak PD L-2-amino-4-phosphonobutyrate (L-AP4) is an agonist at the type IV metabotropic glutamate receptor which is negatively coupled to adenylate cyclase. Eur. J. Pharmacol 1992, 227 (3), 361–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gasparini F; Bruno V; Battaglia G; Lukic S; Leonhardt T; Inderbitzin W; Laurie D; Sommer B; Varney M; Hess S; et al. (R, S)-4-phosphonophenylglycine, a potent and selective group III metabotropic glutamate receptor agonist, is anticonvulsive and neuroprotective in vivo. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther 1999, 289 (3), 1678–1687. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Christopoulos A. Allosteric binding sites on cell-surface receptors: novel targets for drug discovery. 2002;1(3):198-210. Nat. Rev. Drug. Discov 2002, 1 (3), 198–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Conn PJ; Lindsley CW; Meiler J; Niswender CM Opportunities and challenges in the discovery of allosteric modulators of GPCRs for treating CNS disorders. Nat. Rev. Drug. Discov 2014, 13 (9), 692–708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Célanire S; Campo B Recent advances in the drug discovery of metabotropic glutamate receptor 4 (mGluR4) activators for the treatment of CNS and non-CNS disorders. Expert. Opin. Drug. Discov 2012, 7 (3), 261–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bolea C. Amido derivatives and their use as positive allosteric modulators of metabotropic glutamate receptors. PCT Int. Appl. WO 2009010454 A3, 2009.

- 25.Liverton NJ; Boléa C; Celanire S; Luo YF Tricyclic Compounds as Allosteric Modulators of Metabotropic Glutamate Receptors. U.S. Pat. Appl. 2013/0210807 A1, 2013.

- 26.McCauley JA Sulfonamide derivative metabotropic glutamate r4 ligands. U.S. Pat. Appl. 2011/0243844 A1, 2011.

- 27.Marino MJ, Williams DL Jr, O'Brien JA, Valenti O, McDonald TP, Clements MK, Wang R, DiLella AG, Hess JF, Kinney GG. Allosteric modulation of group III metabotropic glutamate receptor 4: a potential approach to Parkinson's disease treatment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 2003, 100 (23), 13668–13673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bennouar K-E; Uberti MA; Melon C; Bacolod MD; Jimenez HN; Cajina M; Kerkerian-Le Goff L; Doller D; Gubellini P Synergy between L-DOPA and a novel positive allosteric modulator of metabotropic glutamate receptor 4: implications for Parkinson's disease treatment and dyskinesia. Neuropharmacology 2013, 66 (23), 158–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hong S-P; Liu KG; Ma G; Sabio M; Uberti MA; Bacolod MD; Peterson J; Zou ZZ; Robichaud AJ; Doller D Tricyclic thiazolopyrazole derivatives as metabotropic glutamate receptor 4 positive allosteric modulators. J. Med. Chem 2011, 54 (14), 5070–5081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Robichaud AJ; Engers DW; Lindsley CW; Hopkins CR Recent progress on the identification of metabotropic glutamate 4 receptor ligands and their potential utility as CNS therapeutics. ACS. Chem. Neurosci 2011, 2 (8), 433–449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Charvin D; Di Paolo T; Bezard E; Gregoire L; Takano A; Duvey G; Pioli E; Halldin C; Medori R; Conquet F An mGlu4-Positive Allosteric Modulator A lleviates Parkinsonism in P rimates. Mov. Disord 2018, 33 (10), 1619–1631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Charvin D; Pomel V; Ortiz M; Frauli M. l.; Scheffler S; Steinberg E; Baron L; Deshons L; Rudigier R; Thiarc D; et al. Discovery, structure–activity relationship, and antiparkinsonian effect of a potent and brain-penetrant chemical series of positive allosteric modulators of metabotropic glutamate receptor 4. J. Med. Chem 2017, 60 (20), 8515–8537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schann S; Mayer S; Morice C; Giethlen B Oxime derivatives and their use as allosteric modulators of metabotropic glutamate receptors. U.S. Pat. Appl. 2015/8962627 B2, 2015.

- 34.East SP; Bamford S; Dietz MG; Eickmeier C; Flegg A; Ferger B; Gemkow MJ; Heilker R; Hengerer B; Kotey A; et al. An orally bioavailable positive allosteric modulator of the mGlu4 receptor with efficacy in an animal model of motor dysfunction. Bioorganic. Med. Chem. Lett 2010, 20 (16), 4901–4905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.East SP; Gerlach K mGluR4 positive allosteric modulators with potential for the treatment of Parkinson's disease: WO09010455. Expert. Opin. Ther. Pat 2010, 20 (3), 441–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Engers DW; Blobaum AL; Gogliotti RD; Cheung Y-Y; Salovich JM; Garcia-Barrantes PM; Daniels JS; Morrison R; Jones CK; Soars MG; et al. Discovery, synthesis, and preclinical characterization of N-(3-Chloro-4-fluorophenyl)-1 H-pyrazolo [4, 3-b] pyridin-3-amine (VU0418506), a novel positive allosteric modulator of the metabotropic glutamate receptor 4 (mGlu4). Acs. Chem. Neurosci 2016, 7 (9), 1192–1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Patnaik S; Zheng W; Choi JH; Motabar O; Southall N; Westbroek W; Lea WA; Velayati A; Goldin E; Sidransky E; et al. Discovery, structure–activity relationship, and biological evaluation of noninhibitory small molecule chaperones of glucocerebrosidase. J. Med. Chem 2012, 55 (12), 5374–5348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lindsley CW; Hopkins CR Metabotropic glutamate receptor 4 (mGlu4)-positive allosteric modulators for the treatment of Parkinson's disease: historical perspective and review of the patent literature. Expert. Opin. Ther. Pat 2012, 22 (5), 461–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Panarese JD; Engers DW; Wu Y; Guernon JM; Chun A; Gregro AR; Bender AM; Capstick RA; Wieting JM; Bronson JJ; et al. The discovery of VU0652957 (VU2957, Valiglurax): SAR and DMPK challenges en route to an mGlu4 PAM development candidate. Bioorganic. Med. Chem. Lett 2019, 29 (2), 342–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kalinichev M; Le Poul E; Boléa C; Girard F; Campo B; Fonsi M; Royer-Urios I; Browne SE; Uslaner JM; Davis MJ; et al. Characterization of the novel positive allosteric modulator of the metabotropic glutamate receptor 4 ADX88178 in rodent models of neuropsychiatric disorders. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther 2014, 350 (3), 495–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Engers DW; Niswender CM; Weaver CD; Jadhav S; Menon UN; Zamorano R; Conn PJ; Lindsley CW; Hopkins CR Synthesis and evaluation of a series of heterobiarylamides that are centrally penetrant metabotropic glutamate receptor 4 (mGluR4) positive allosteric modulators (PAMs). J. Med. Chem 2009, 52 (14), 4115–4118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Niswender CM; Jones CK; Lin X; Bubser M; Thompson Gray A; Blobaum AL; Engers DW; Rodriguez AL; Loch MT; Daniels JS; et al. Development and antiparkinsonian activity of VU0418506, a selective positive allosteric modulator of metabotropic glutamate receptor 4 homomers without activity at mGlu2/4 heteromers. ACS. Chem. Neurosci 2016, 7 (9), 1201–1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Testa CM; Standaert DG; Young AB; Penney JB Jr Metabotropic Glutamate Receptor mRNA Expression in the Basal Ganglia of the Rat. J. Neurosci 1994, 74 (5), 3005–3018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hudtloff C; Thomsen C Autoradiographic visualization of group III metabotropic glutamate receptors using [3H]-L-2-amino-4-phosphonobutyrate. Br. J. Pharmacol 1998, 124 (5), 971–977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Patel S; Hamill TG; Connolly B; Jagoda E; Li WP; Gibson RE Species differences in mGluR5 binding sites in mammalian central nervous system determined using in vitro binding with [18F]F-PEB. Nucl. Med. Biol 2007, 34 (8), 1009–1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pike VC Considerations in the Development of Reversibly Binding PET Radioligands for Brain Imaging. Curr. Med. Chem 2016, 23 (18), 1818–1869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Annoura H; Fukunaga A; Uesugi M; Tatsuoka T; Horikawa Y A novel class of antagonists for metabotropic glutamate receptors, 7-(hydroxyimino) cyclopropa [b] chromen-1a-carboxylates. Bioorganic. Med. Chem. Lett 1996, 6 (7), 763–766. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gasparini F; Lingenhöhl K; Stoehr N; Flor PJ; Heinrich M; Vranesic I; Biollaz M; Allgeier H; Heckendorn R; Urwyler S; et al. 2-Methyl-6-(phenylethynyl)-pyridine (MPEP), a potent, selective and systemically active mGlu5 receptor antagonist. Neuropharmacology 1999, 38 (10), 1493–1503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Varney MA; Cosford ND; Jachec C; Rao SP; Sacaan A; Lin F-F; Bleicher L; Santori EM; Flor PJ; Allgeier H SIB-1757 and SIB-1893: selective, noncompetitive antagonists of metabotropic glutamate receptor type 5. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther 1996, 6 (7), 763–766. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Williams R; Zhou Y; Niswender CM; Luo QW; Conn PJ; Lindsley CW; Hopkins CR Re-exploration of the PHCCC scaffold: discovery of improved positive allosteric modulators of mGluR4. ACS. Chem. Neurosci 2010, 1 (6), 411–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schann S; Mayer S; Morice C; Giethlen B Novel oxime derivatives and their use as allosteric modulators of metabotropic glutamate receptors. PCT Int. Appl. WO 2011051478 A1, 2011.

- 52.Gonzalez-Latapi P; Bhowmick SS; Saranza G; Fox SH Non-dopaminergic treatments for motor control in Parkinson's disease: an update. CNS. Drugs 2020, 34 (10), 1025–1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rascol O; Medori R; Baayen C; Such P; Meulien D; Group AS A Randomized, Double-Blind, Controlled Phase II Study of Foliglurax in Parkinson's Disease. Mov. Discord 2022, 37 (5), 1088–1093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.AMALRIC C; BARRE A; Mayer S; Dorange I; Manteau B; Blayo A Substituted quinazolinone derivatives and their use as positive allosteric modulators of mglur4. PCT Int. Appl. WO 2020021064 A1, 2020.

- 55.Mathiesen JM; Svendsen N; Bräuner-Osborne H; Thomsen C; Ramirez MT Positive allosteric modulation of the human metabotropic glutamate receptor 4 (hmGluR4) by SIB-1893 and MPEP. Br. J. Pharmacol 2003, 138 (6), 1026–1030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sharma S; Kedrowski J; Rook JM; Smith RL; Jones CK; Rodriguez AL; Conn PJ; Lindsley CW Discovery of molecular switches that modulate modes of metabotropic glutamate receptor subtype 5 (mGlu5) pharmacology in vitro and in vivo within a series of functionalized, regioisomeric 2-and 5-(phenylethynyl) pyrimidines. J. Med. Chem 2009, 52 (14), 4103–4106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Niswender CM; Johnson KA; Weaver CD; Jones CK; Xiang ZX; Luo QW; Rodriguez AL; Marlo JE; de Paulis T; Thompson AD; et al. Discovery, characterization, and antiparkinsonian effect of novel positive allosteric modulators of metabotropic glutamate receptor 4. Mol. Pharmacol 2008, 74 (5), 1345–1358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Betts MJ; O'Neill MJ; Duty S Allosteric modulation of the group III mGlu4 receptor provides functional neuroprotection in the 6-hydroxydopamine rat model of Parkinson's disease. Br. J. Pharmacol 2012, 166 (8), 2317–2330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Williams R; Johnson KA; Gentry PR; Niswender CM; Weaver CD; Conn PJ; Lindsley CW; Hopkins CR Synthesis and SAR of a novel positive allosteric modulator (PAM) of the metabotropic glutamate receptor 4 (mGluR4). Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett 2009, 19 (17), 4967–4970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kil K-E; Zhang ZD; Jokivarsi K; Gong CY; Choi J-K; Kura S; Brownell A-L Radiosynthesis of N-(4-chloro-3-[11C] methoxyphenyl)-2-picolinamide ([11C] ML128) as a PET radiotracer for metabotropic glutamate receptor subtype 4 (mGlu4). Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett 2013, 21 (19), 5955–5962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kil K-E; Poutiainen P; Zhang ZD; Zhu AJ; Choi J-K; Jokivarsi K; Brownell A-L Radiosynthesis and evaluation of an 18F-labeled positron emission tomography (PET) radioligand for metabotropic glutamate receptor subtype 4 (mGlu4). J. Med. Chem 2014, 57 (21), 9130–9138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wang JF; Shoup TM; Brownell A-L; Zhang ZD Improved synthesis of the thiophenol precursor N-(4-chloro-3-mercaptophenyl) picolinamide for making the mGluR4 PET ligands. Tetrahedron 2019, 75 (29), 3917–3922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Takano A; Nag S; Jia ZS; Jahan M; Forsberg A; Arakawa R; Grybäck P; Duvey G; Halldin C; Charvin D Characterization of [11C] PXT012253 as a PET Radioligand for mGlu 4 Allosteric Modulators in Nonhuman Primates. Mol. Imaging Biol 2019, 21 (3), 500–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wang JF; Qu XY; Shoup TM; Yuan GY; Afshar S; Pan CZ; Zhu AJ; Choi J-K; Kang HJ; Poutiainen P; et al. Synthesis and characterization of fluorine-18-Labeled N-(4-Chloro-3-((Fluoromethyl-D 2) Thio) Phenyl) Picolinamide for imaging of mGluR4 in brain. J. Med. Chem 2020, 63 (6), 3381–3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang JF; Moon SH; Cleary MB; Shoup TM; El Fakhri G; Zhang ZD; Brownell AL Detailed Radiosynthesis of [18F]mG4P027 as a Positron Emission Tomography (PET) Radiotracer for mGluR4. J. Labelled Comp. Radiopharm 2023, 66 (2), 34–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Engers DW; Field JR; Le U; Zhou Y; Bolinger JD; Zamorano R; Blobaum AL; Jones CK; Jadhav S; Weaver CD; et al. Discovery, synthesis, and structure–activity relationship development of a series of N-(4-Acetamido) phenylpicolinamides as positive allosteric modulators of metabotropic glutamate receptor 4 (mGlu4) with CNS exposure in rats. J. Med. Chem 2011, 54 (4), 1106–1110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.McCauley JA; Butcher JW; Hess JW; Liverton NJ; Romano JJ Sulfonamide derivatives as mGluR4 receptor ligands. PCT Int. Appl. WO 2010033350 A1, 2010.

- 68.Jones CK; Engers DW; Thompson AD; Field JR; Blobaum AL; Lindsley SR; Zhou Y; Gogliotti RD; Jadhav S; Zamorano R; et al. Discovery, synthesis, and structure–activity relationship development of a series of N-4-(2, 5-dioxopyrrolidin-1-yl) phenylpicolinamides (VU0400195, ML182): characterization of a novel positive allosteric modulator of the metabotropic glutamate receptor 4 (mGlu4) with oral efficacy in an antiparkinsonian animal model. J. Med. Chem 2011, 54 (21), 7639–7647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fulton MG; Loch MT; Rodriguez AL; Lin X; Javitch JA; Conn PJ; Niswender CM; Lindsley CW Synthesis and pharmacological evaluation of bivalent tethered ligands to target the mGlu2/4 heterodimeric receptor results in a compound with mGlu2/2 homodimer selectivity. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett 2020, 30 (13), 127212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wang JF; Li YB; Takahashi K; El Fakhri G SuFEx click chemistry enabled fast efficient F-18 labeling (5 seconds) for the understanding of drug development - A case study. J. Nucl. Med 2023, 64 (Supplement 1), P731. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Engers DW; Bollinger SR; Engers JL; Panarese JD; Breiner MM; Gregro A; Blobaum AL; Bronson JJ; Wu YJ; Macor JE; et al. Discovery and characterization of N-(1, 3-dialkyl-1H-indazol-6-yl)-1H-pyrazolo [4, 3-b] pyridin-3-amine scaffold as mGlu4 positive allosteric modulators that mitigate CYP1A2 induction liability. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett 2018, 28 (15), 2641–2646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bollinger SR; Engers DW; Panarese JD; West M; Engers JL; Loch MT; Rodriguez AL; Blobaum AL; Jones CK; Thompson Gray A; et al. Discovery, Structure–Activity Relationship, and Biological Characterization of a Novel Series of 6-((1 H-Pyrazolo [4, 3-b] pyridin-3-yl) amino)-benzo [d] isothiazole-3-carboxamides as Positive Allosteric Modulators of the Metabotropic Glutamate Receptor 4 (mGlu4). J. Med. Chem 2019, 62 (1), 342–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Panarese JD; Engers DW; Wu Y-J; Bronson JJ; Macor JE; Chun A; Rodriguez AL; Felts AS; Engers JL; Loch MT; et al. Discovery of VU2957 (valiglurax): An mGlu4 positive allosteric modulator evaluated as a preclinical candidate for the treatment of Parkinson's disease. ACS. Med. Chem. Lett 2018, 10 (3), 255–260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bolea C; Celanire S Preparation of novel heteroaromatic derivatives and their use as positive allosteric modulators of metabotropic glutamate receptors. PCT Int. Appl. WO 2009010455 A2, 2009.

- 75.Le Poul E; Bolea C; Girard F; Poli S; Charvin D; Campo B; Bortoli J; Bessif A; Luo B; Koser AJ; et al. A potent and selective metabotropic glutamate receptor 4 positive allosteric modulator improves movement in rodent models of Parkinson's disease. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther 2012, 343 (1), 167–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Fujinaga M; Yamasaki T; Nengaki N; Ogawa M; Kumata K; Shimoda Y; Yui J; Xie L; Zhang YD; Kawamura K; et al. Radiosynthesis and evaluation of 5-methyl-N-(4-[11C] methylpyrimidin-2-yl)-4-(1H-pyrazol-4-yl) thiazol-2-amine ([11C] ADX88178) as a novel radioligand for imaging of metabotropic glutamate receptor subtype 4 (mGluR4). Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett 2016, 26 (2), 370–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wang JF; Shoup T; Qu XY; Kang HJ; El Fakhri G; Zhang ZD; Brownell A-L Synthesis and evaluation of a F-18 labeled tricyclic thiazolopyrazole derivative for imaging of metabotropic glutamate receptor 4 (mGluR4). J. Nucl. Med 2020, 61 (Supplement 1), 1031. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Niswender CM; Lebois EP; Luo QW; Kim K; Muchalski H; Yin HY; Conn PJ; Lindsley CW Positive allosteric modulators of the metabotropic glutamate receptor subtype 4 (mGluR4): Part I. Discovery of pyrazolo [3, 4-d] pyrimidines as novel mGluR4 positive allosteric modulators. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett 2008, 18 (20), 5626–5630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Williams R; Niswender CM; Luo QW; Le U; Conn PJ; Lindsley CW Positive allosteric modulators of the metabotropic glutamate receptor subtype 4 (mGluR4). Part II: Challenges in hit-to-lead. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett 2009, 19 (3), 962–966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]