Abstract

Objective

Interleukin (IL)-22 is a potential therapeutic protein for the treatment of metabolic diseases such as obesity, type 2 diabetes, and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease due to its involvement in multiple cellular pathways and observed hepatoprotective effects. The short serum half-life of IL-22 has previously limited its use in clinical applications; however, the development of mRNA-lipid nanoparticle (LNP) technology offers a novel therapeutic approach that uses a host-generated IL-22 fusion protein. In the present study, the effects of administration of an mRNA-LNP encoding IL-22 on metabolic disease parameters was investigated in various mouse models.

Methods

C57BL/6NCrl mice were used to confirm mouse serum albumin (MSA)-IL-22 protein expression prior to assessments in C57BL/6NTac and CETP/ApoB transgenic mouse models of metabolic disease. Mice were fed either regular chow or a modified amylin liver nonalcoholic steatohepatitis–inducing diet prior to receiving either LNP-encapsulated MSA-IL-22 or MSA mRNA via intravenous or intramuscular injection. Metabolic markers were monitored for the duration of the experiments, and postmortem histology assessment and analysis of metabolic gene expression pathways were performed.

Results

MSA-IL-22 was detectable for ≥8 days following administration. Improvements in body weight, lipid metabolism, glucose metabolism, and lipogenic and fibrotic marker gene expression in the liver were observed in the MSA-IL-22–treated mice, and these effects were shown to be durable.

Conclusions

These results support the application of mRNA-encoded IL-22 as a promising treatment strategy for metabolic syndrome and associated comorbidities in human populations.

Keywords: interleukin-22, Lipid nanoparticle therapeutic, Messenger RNA, Metabolic disorders, Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease, Serum lipid parameters

Graphical abstract

Created with BioRender.com.

Highlights

-

•

In mice, durable expression and subsequent effects of MSA-IL-22 were observed.

-

•

MSA-IL-22 ameliorated metabolic syndrome–associated parameters.

-

•

MSA-IL-22 improved body weight in mice with diet-induced MASLD.

-

•

Correction of hepatic steatosis and dyslipidemia was also observed.

-

•

Data support mRNA-encoded IL-22 as a treatment for metabolic syndrome.

Abbreviations

- ALT

alanine aminotransferase

- AMLN

amylin liver nonalcoholic steatohepatitis

- AST

aspartate aminotransferase

- CRP

C-reactive protein

- eWAT

epididymal white adipose tissue

- H&E

hematoxylin and eosin

- HDL

high-density lipoprotein

- IL

interleukin

- IL-22R1

interleukin-22 receptor 1

- IM

intramuscular

- IV

intravenous

- LDL

low-density lipoprotein

- LNP

lipid nanoparticle

- MASLD

metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease

- MSA

mouse serum albumin

- PYY

peptide YY

- RT-qPCR

reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction

- STAT

signal transducer and activator of transcription

1. Introduction

The rising incidence of metabolic diseases such as obesity, type 2 diabetes, and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD; previously called nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, NAFLD) is of growing global concern, impacting more than 650 million, 437 million, and 882 million individuals globally, respectively [[1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [6]]. Although invasive and noninvasive treatment options for metabolic diseases are available, many of these interventions are difficult to maintain or associated with safety concerns [[7], [8], [9]]. Growing evidence suggests that endogenous cytokines have improved safety profiles and, when used therapeutically, may alleviate symptoms associated with metabolic disease [10]. Interleukin (IL)-22 has been identified as one such cytokine with therapeutic potential due to its biological impacts on multiple metabolic disease factors [11].

IL-22 is a member of the IL-10 cytokine family that mediates cellular responses by binding to the IL-22 receptor 1 (IL-22R1), a receptor predominantly expressed on epithelial cells and some fibroblasts. Binding of IL-22 to its receptor induces conformational changes that enable interaction of the IL-22/IL-22R1 complex with IL-10 receptor β [12,13]. This, in turn, activates Janus kinase 1-tyrosine-kinase 2 (JAK1-TYK2 kinases), leading to serine phosphorylation of signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) proteins, particularly STAT3 [14,15]. Activation of the STAT3 transcription factor leads to downstream expression of the extracellular signal-regulated kinases, c-Jun N-terminal kinase, and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways [15]. Through these pathways, IL-22 promotes the expression of downstream innate immune mediators, mitogenic modulators, and antiapoptotic modulators that promote survival, proliferation, and regeneration [15].

IL-22 is distinct from other IL-10 cytokine family members that affect immunomodulatory cells and primarily targets epithelial cell populations such as hepatocytes and pancreatic acinar cells [[16], [17], [18], [19]]. Direct hepatoprotective effects of IL-22 have been demonstrated in a study of liver-specific IL-22 transgenic mice [20]. In this study, mice with serum IL-22 levels as high as ∼6000 pg/mL showed normal growth and no obvious adverse phenotypes, with the exception of lower body weight after 5 months. Histological examination findings were also largely normal, except for a slight thickening of the epidermis and minor skin inflammation compared with wild-type mice. These findings suggest that the specificity of an IL-22 therapeutic may limit its side effects [20].

Further preclinical evidence supports the therapeutic potential of IL-22 for metabolic diseases. Mice that are deficient in IL-22 and fed a high-fat diet are prone to developing metabolic disorders, which can be reversed by the administration of exogenous IL-22 [11]. In other studies, results indicated that IL-22 may play a protective role in preventing tissue injury during acute liver inflammation [21] and attenuate oxidative stress through inducing hepatic metallothionein [22]. IL-22 has also been shown to be involved in liver regeneration after partial hepatectomy [23] and have beneficial effects on alcoholic hepatitis [24]. In obese mice, IL-22 administration improved glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity, resolved hyperinsulinemia and hyperproinsulinemia, and decreased body weight and redistributions of fat [25].

In vivo studies have suggested that IL-22 may show promise for the treatment of liver-associated metabolic diseases; however, the short serum half-life (<2 h) of IL-22 has limited its use in clinical applications [13]. To overcome the limitation of the short half-life of IL-22 and other cytokine therapeutics, previous studies have evaluated frequent dose administration or the use of fusion to immunoglobulins or serum albumin to improve stability [17,[26], [27], [28], [29]]. Significantly, a recombinant human IL-22 dimer fusion protein, known as F-652, was shown to be tolerable in healthy participants in phase 1/2 clinical trials [26,30]. Currently, F-652 is under development for conditions such as acute graft-versus-host disease and acute alcoholic hepatitis [31].

Serum stabilization is essential for the therapeutic use of IL-22; therefore, the flexibility of fusion protein design and delivery facilitated by lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) make mRNA-LNP technology suitable for enabling treatment with host-generated serum-stable IL-22 fusion protein [32]. The adaptability of the mRNA-LNP platform approach has been demonstrated across protein therapeutics, including IL-10 [33], IL-12 [34], IL-2 [35], and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor [36] and in ongoing clinical trials for OX40 ligand, IL-23, IL-36γ, IL-12, and IL-15 [37].

In the current study, the effects of an mRNA-LNP formulation encoding IL-22 covalently linked to serum albumin on body weight, lipid metabolism, glucose metabolism, and lipogenic and fibrotic marker gene expression in the liver were evaluated in mouse models of metabolic disease.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. mRNA-LNP production and formulation

A sequence-optimized mRNA encoding mouse IL-22 with either the N- or C-terminus linked to mouse serum albumin (MSA) was synthesized in vitro using an optimized T7 RNA polymerase-mediated transcription reaction with complete replacement of uridine by N1-methyl-pseudouridine, as previously described [38]. The reaction contained a DNA template encoding the IL-22 open reading frame flanked by 5′ and 3′ untranslated region sequences and terminated by an encoded poly-A tail. A 5’ Cap 1 structure was added using Vaccinia capping enzyme (New England Biolabs) and Vaccinia 2′ O-methyltransferase (New England Biolabs) after transcription. The mRNA was purified by oligo-dT affinity purification, buffer exchanged by tangential flow filtration into sodium acetate (pH 5.0), sterile filtered, and stored at −20 °C until further use.

The resultant mRNA was encapsulated in an LNP using a modified ethanol-drop nanoprecipitation process that was previously described [39]. The mRNA was mixed with ionizable, structural, helper, and polyethylene glycol lipids in acetate buffer (pH 5.0) in a 2.5:1 (lipids:mRNA) ratio. The mixture was neutralized with Tris-Cl (pH 7.5), sucrose was added as a cryoprotectant, and the final solution was sterile filtered. The formulated LNP was stored at −70 °C until further use. Analytical characterization, including determination of particle size and polydispersity, encapsulation, mRNA purity, double-stranded RNA content, osmolality, pH, endotoxin, and bioburden, indicated that all formulations had a particle size of 80–100 nm, >80% mRNA encapsulation, and <1 EU/mL endotoxin and were acceptable for in vivo study.

2.2. In vitro synthesis and detection of MSA and MSA-IL-22

HeLa cells were maintained using Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum at 37 °C in an atmosphere containing 5% CO2. To assess in vitro protein expression levels for each construct, cells were transfected with C-terminally linked IL-22-MSA or N-terminally linked MSA-IL-22 using Lipofectamine 2000 per the manufacturer's instructions. HEK-Blue™ IL-22 cells (HEK293 cells expressing the human IL-22R1, IL-10 receptor β, STAT3, and a STAT3-inducible secreted embryonic alkaline phosphatase reporter gene; InvivoGen) were maintained according to the manufacturer's protocol. Cells were then seeded at 50,000 cells/well in 96-well plates and incubated with conditioned media from the transfected HeLa cells (5, 2.5, 1.25, 0.625, 0.312, and 0.156 ng) and incubated for 24 h at 37 °C. After the incubation, 20 μL of spent media was added to 180 μL QUANTI-Blue solution and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min to allow for color development. Production of the secreted embryonic alkaline phosphatase reporter was quantified by densitometry (655 nm) using a Synergy HT2 instrument (Biotek).

2.3. Animal models

Screening for IL-22 expression and for SAA1/SAA2 and Reg3g expression were conducted per in-house standard protocol in 8-week-old female C57BL/6NCrl mice (Charles River). Mice were fed a regular chow diet (Prolab® IsoPro® RMH 3000, 26 kcal% protein, 14 kcal% fat). Mice were shipped to Moderna, Inc., and acclimated for 1 week. They were not randomly assigned and were housed in groups of 5.

For the disease models, male C57BL/6NTac and male CETP/ApoB mice, both from Taconic Biosciences, were used. C57BL/6NTac mice were fed with a modified amylin liver nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (AMLN) diet (D09100310i, Taconic Biosciences) containing high-fat and high-carbohydrate content (40 kcal% fat, 20 kcal% fructose, and 2% cholesterol) or a regular chow diet as a control. C57BL/6NTac mice conditioned with an AMLN diet exhibited obesity after ≥26 weeks, with corresponding metabolic and liver histopathologic features of MASLD such as steatosis and hepatic inflammation, including hepatic crown-like structures and activated stellate cells [40,41]. These effects arise not only from the elevated uptake of dietary lipids but also from the upregulation of endogenous fatty acid synthesis via de novo lipogenesis [42]. Comprehensive phenotype and growth information about this mouse model is available online [40] and has been published [43]. For the studies presented herein, animals were fed the AMLN diet for 18 weeks or 34 weeks for the study with animals with more severe disease.

CETP/ApoB mice (B6.SJL-Tg[APOA-CETP]1Dsg Tg[APOB]1102Sgy N10 – 3716- M) were fed the AMLN diet for 6 weeks (disease model) or a regular chow diet (control group). This mouse model expresses both human cholesteryl ester transfer protein (CETP) and human apolipoprotein B100 (ApoB100) transgenes and thus exhibits humanized serum high-density lipoprotein (HDL) and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol distribution.

Male mice were fed at Taconic Biosciences for 16 or 32 weeks (C57BL/6NTac) or 6 weeks (CETP/ApoB), shipped to Moderna, Inc., and then acclimated for an additional 2 weeks. Animals were then randomly assigned to matched study groups based on age, body weight, and lipid profiles (the latter only for certain studies) and housed in groups of 2 or single-caged only in the study with animals with more severe disease at 22 °C on a 12-hour light, 12-hour dark cycle. Matched AMLN diet groups were subsequently divided into treatment groups to receive LNP-encapsulated MSA-IL-22 (0.5 mg/kg) or MSA (0.5 mg/kg) mRNA intravenously (IV) through the lateral tail vein or 0.1 mg/kg of MSA or, in some studies, MSA-IL-22 via intramuscular (IM) injection in the quadriceps. For the studies in C57BL/6NTac mice, an untreated AMLN diet–fed group was maintained in parallel, and an untreated, control chow diet–fed group was included at the end or maintained in parallel for comparison.

Body weight and food intake were monitored twice weekly. Mice were euthanized by CO2 asphyxiation followed by cervical dislocation at the end of each experiment; serum, liver, and epididymal adipose tissue (for certain studies) were harvested for subsequent analyses. Tissues were either snap frozen, immersed in RNAlater (Invitrogen, cat no. AM7021), or formalin fixed, depending on the designated downstream analysis. Metabolic efficiency was calculated by dividing the body weight gain (mg) throughout the course of the study by the total metabolizable energy (kcal) of the diet consumed in the same period [44]. The corresponding dietary content values were 4.4867 kcal/g and 3.16 kcal/g for the AMLN and chow diets, respectively.

During the studies, mice that presented with wounds or died due to excessive fighting were excluded from all analyses. No differences were found in unscheduled deaths between the different treatment groups, and all deaths were most likely linked to the generally aggressive behavior of male C57BL/6N mice when housed together. All research involving animals was conducted in accordance with the Moderna, Inc., Animal Care and Use guidelines and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

2.4. Quantification of serum lipid, cytokines, ALT, AST, CRP, glucose, IL-22, and PYY levels

Murine blood samples were collected from the submandibular vein, followed by immediate collection of serum by centrifugation for 7 min at 4700× g in MiniCollect serum separator tubes (Greiner Bio-One, cat no. 450472). Serum aliquots were stored at −80 °C. LDL and HDL cholesterol, triglyceride and total serum cholesterol concentrations, alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and C-reactive protein (CRP) levels were quantified by IDEXX BioAnalytics using a Beckman Coulter AU680 analyzer. For the LDL cholesterol readout, the limit of the detection of the instrument was 7 mg/dL. Cytokine levels were measured by the Luminex commercial panel Mouse ProcartaPlex Mix&Match 11-plex (PPX-11-MXEPUXD).

Serum IL-22 and tissue levels in the small intestine, large intestine, liver, and spleen were determined using the Mouse IL-22 DuoSet ELISA (R&D Systems, cat no. DY582) per the manufacturer's protocol. Absorbance values were determined at 450 nm using a Synergy HT2 and analyzed with Gen5 software (v3.1.1) using a 4-parameter logistic curve fit from the standard curve. Peptide YY (PYY) levels were measured in mice that were initially fasted overnight for 12 h; the mice were then refed for 1 h. PYY levels were determined using the PYY ELISA kit (BioVendor, LLC YK081) following the manufacturer's protocol. Glucose levels were measured after fasting and refeeding using Abbott Alphatrak 2 glucometers.

2.5. Glucose tolerance tests

Glucose tolerance tests were performed as previously described [45,46]. Male AMLN diet–fed C57BL/6NTac mice and chow diet–fed control mice were housed in pairs and fasted for 6 h during the daytime. Thereafter, baseline fasting glucose was measured (0 min), and glucose (2 g/kg) in saline (0.9%) was administered via intraperitoneal injection. Blood glucose was measured 15, 30, 60, and 120 min after glucose administration using Abbott Alphatrak 2 glucometers.

2.6. RNA isolation and RT-qPCR

Total liver RNA was isolated using the Maxwell RSC simplyRNA Tissue Kit (Promega, cat no. AS1340) and automated Maxwell RSC 48 instrument (Promega, cat no. AS8500). Total liver RNA was isolated using QIAshredder columns (Qiagen, cat no. 79656) and RNeasy mini purification kit (Qiagen, cat no. 74106) according to the manufacturer's protocol for the in vivo gene expression analysis in C57BL/6Tac mice. All RNA was quantified with a NanoDrop UV visible spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher) for reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) analyses. Per the supplier's protocol, complementary DNA was synthesized from 1000 ng of RNA per sample with the TaqMan real-time PCR assay (Thermo Fisher, cat no. 4387406). RT-qPCR was performed as previously described [46] using a QuantStudio 7 Pro qPCR system, with results normalized to ribosomal protein L19 (Rpl19) gene expression.

2.7. RNA isolation and quantification of gene expression levels using NanoString technology for the nCounter Mouse Metabolic Pathways Panel

RNA was isolated from livers (immersed and stored in RNAlater solution at 4 °C) of AMLN diet–fed C57BL/6Tac untreated mice and those treated weekly with either MSA-IL-22 or MSA over 6 weeks, using the automated Promega Maxwell RSC simplyRNA Tissue Kit per the manufacturer's recommendations (Promega, cat no. AS1340). RNA quality was assessed using Tape Station RNA ScreenTape (Agilent, cat no. 5067-5576) and quantified using the Invitrogen Quant-iT RNA Broad Range Assay Kit (Invitrogen, cat no. Q10213). RNA (50 ng) was used as input for the nCounter Mouse Metabolic Pathways Panel (XT-CSO-MMP1-12) according to the nCounter XT CodeSet Gene Expression Assays protocol. Resulting Reporter Code Count files were examined with NanoString nSolver software for Quality Control analysis.

2.8. Histology analysis

Liver and adipose tissues were collected and fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for 48 h for subsequent routine paraffin processing. Paraffin-embedded samples were sectioned (4 μm) and mounted on charged glass slides. Immunohistochemistry was performed using an AutostainerPlusLink stainer (Dako). Slides were baked and dewaxed; this was followed by heat-induced epitope retrieval performed in a Dako PT Link using a TRIS/EDTA buffer (FLEX TRS High, pH9; Dako, K8004). In the stainer, slides were incubated in a 3.0% hydrogen peroxide block and a serum-free protein block, followed by application of rabbit monoclonal F4/80 primary antibody (Cell Signaling, cat no. 70076). After application of EnVision + anti-Rabbit Labelled Polymer-HRP (Dako, K4003), DAB + Chromogen Solution (Dako, K3468) was used for chromogenic brightfield visualization. Samples were then counterstained for 5 min with modified Harris hematoxylin (Dako, S3301) and sealed with a coverslip. Slides were scanned at 20× on an Aperio AT2 whole slide scanner, and images were analyzed with Indica Labs HALO software. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)–, picrosirius red–, or F4/80–stained liver tissue and H&E-stained adipose tissue were analyzed and scored as previously described [47]. The severity of micro- and macrovesicular steatosis and hepatocellular hypertrophy (defined as cellular enlargement ≥1.5 times normal hepatocyte diameter) was scored based on the percentage of total area affected. Inflammation was scored by averaging the number of inflammatory foci across 5 microscope fields. Scoring of hepatic fibrosis severity was based on the presence of pathological collagen staining by picrosirius red, and F4/80 staining was also used to evaluate macrophage clusters. CellSens (Olympus) software was used for objective scoring of adipose tissue hypertrophy by measuring the diameters of 5 representative adipocytes at 40× magnification.

2.9. Statistical analysis

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was the main model of choice. Animal effects were included for data involving repeated measures, and time was modeled as a categorical variable where applicable [48,49]. A Bayesian version [50] of ANOVA was used for left-censored lipid data in which values were below the assay lower limit of detection. Where indicated, responses were modeled on a log10 scale or after Box–Cox transformation [51] to meet normality requirements. All fitted models were examined for their residual diagnostics and goodness-of-fit criteria. The terms used in each model are described in their respective figure descriptions. Dunnett contrasts were calculated for comparison against the MSA group. For liver histology scores, all pairwise contrasts were performed. R package emmeans [52] was used to calculate estimates and their respective 95% confidence intervals. Multiple comparisons were adjusted using Sidak correction, except when explicitly noted otherwise. α level was set at 0.05 and 2-sided. All statistical analyses were conducted with R [53] version 4.1.0.

3. Results

3.1. mRNA design, in vitro expression, and bioactivity evaluation

To extend the serum half-life of IL-22 for preclinical investigation, mRNA sequences encoding mouse IL-22 were designed with either the C- or N-terminus covalently linked to MSA via a Glycine-Glycine-Glycine-Serine linker (Table S1). In HeLa cells transfected with the MSA-IL-22 mRNA constructs, the IL-22 fusion proteins were expressed at similar levels for both the N-terminally linked MSA-IL-22 and C-terminally linked IL-22-MSA (Figure 1A). Activity of the expressed MSA-IL-22 proteins was further evaluated by exposing HEK-Blue reporter IL-22 cells to MSA-IL-22–containing conditioned media collected from the transfected HeLa cells. Similar levels of reporter activity were observed for both constructs at MSA-IL-22 concentrations of ≥1.25 ng/mL (Figure 1B). However, given that the C-linked IL-22-MSA had lower activity at concentrations of <1.25 ng/mL, the N-linked MSA-IL-22 mRNA was selected for subsequent in vivo studies.

Figure 1.

Expression and activity of MSA-IL-22 in vitro and in vivo. (A) Levels of N- or C-terminally linked MSA-IL-22 in conditioned media were determined using ELISA 24 h after the transfection of HeLa cells. Data are representative of 3 independent biological replicates (n = 3; mean ± SD). (B) HEK-Blue-IL-22 cells were exposed to MSA-IL-22–containing conditioned media for 24 h, followed by detection of STAT3 pathway activation by densitometry measurements at a wavelength of 655 nm. Results are representative of 3 independent biological replicates (n = 3, mean ± SD). (C) N-terminally linked MSA-IL-22 mRNA was intravenously administered to C57BL/6NCrl female mice at 0.5 mg/kg (n = 5) or 0.25 mg/kg (n = 5). Sera were collected for analysis at 6 h post administration and daily from day 3 through day 7. (D) IL-22 protein levels in sera were determined using ELISA. Mean values with SD error bars are indicated. The half-life of the protein following the treatment dosage of 0.5 mg/kg is determined to be 91.85 h, while the half-life of the protein for the 0.25 mg/kg treatment dosage is calculated to be 125.3 h. ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; IL, interleukin; MSA, mouse serum albumin; SD, standard deviation.

3.2. Durability and distribution of MSA-IL-22 expression in C57BL/6NCrl mice

The expression of N-linked MSA-IL-22 protein in serum was analyzed in female C57BL/6NCrl mice for 7 days (Figure 1C) or 8 days (Figure S1A) following a single IV administration of LNP-encapsulated MSA-IL-22 mRNA. Serum IL-22 protein levels remained relatively stable during the first 3 days after administration, with a gradual decline thereafter (Figure 1D, Figure S1A). Peak serum levels were observed 24 h after injection of MSA-IL-22 mRNA (Figure S1A). IL-22 protein remained detectable in serum for ≥168 h (7 days) after administration, with levels comparable between the groups receiving 0.25-mg/kg and 0.5-mg/kg doses of MSA-IL-22 mRNA. At 24 h following administration, IL-22 protein was detectable at low levels in the small intestine, large intestine, and spleens of MSA-IL-22 mRNA–injected C57BL/6NTac mice and was undetectable in control animals. Levels of IL-22 protein in control chow fed animals were higher in the liver (mean 119 ± 30 pg/mg tissue) than in other organs and increased further following MSA-IL-22 mRNA injection (Figure S1B). The relatively high baseline levels of hepatic IL-22 protein have been reported previously [54]. The durability of MSA-IL-22 expression in vivo was considered sufficient to proceed with the subsequent in vivo evaluation of the metabolic effects of MSA-IL-22 in a model of metabolic disease.

3.3. MSA-IL-22 improves measures of MASLD in AMLN-induced disease models of metabolic disease in C57BL/6NTac mice

3.3.1. Effects of MSA-IL-22 treatment on body weight and lipid metabolism

Male C57BL/6NTac mice were fed an AMLN diet for 18 weeks to induce MASLD before the administration of the first dose of LNP-encapsulated mRNA (Figure 2A). Mice were injected weekly for 6 weeks with LNP-encapsulated MSA or MSA-IL-22 mRNA. Analyses of mouse sera collected 72 h after each MSA-IL-22 administration indicated high levels of IL-22 protein that gradually declined over 6 weeks after the initial dose (Figure S2A). A significant reduction in body weight was observed over time among mice treated with MSA-IL-22 compared with mice treated with MSA (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Metabolic effects of weekly administration of MSA-IL-22 and MSA treatment over 6 weeks in C57BL/6NTac mice. (A) Male C57BL/6NTac mice were fed an AMLN diet from 6 weeks of age (week −18). LNP-encapsulated MSA (n = 9) or MSA-IL-22 (n = 9) mRNA was administered at 0.5 mg/kg weekly over 6 weeks to mice fed an AMLN diet, with an untreated AMLN group (n = 5) maintained in parallel. (B) Body weight and (C) relative lipid parameters of serum cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, and triglyceride levels were determined at week −1 (baseline) and 72 h after the administration of each dose and are expressed as a percentage relative to each mouse's baseline; baseline measure per mouse is treated as 100%. For body weight comparisons, age-matched mice fed a chow diet (n = 6) were included at the end of the treatment period. Significance levels (∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗p < 0.001) are shown relative to mice treated with MSA and (B) were determined by 1-way ANOVA [48] between groups, adjusted for multiple comparisons per time point for body weight analysis. (C) For serum lipid analyses in mg/dL (Figure S2B) and percentages, a C approach was chosen [50] over frequentist to better account for data points falling below the assay limit of detection. Time point–, lipid-, and group-specific linear terms with their interactions were used to model population-level effects, and mouse-level varying effects were specified to account for repeated measures. Heterogeneous variance observed across time points and groups per serum were accounted for by estimating residual variance to change linearly in time points, serum, and groups. Analyses of all serum data excluded 2 mice, 1 in each of the MSA and untreated groups, due to insufficient volume of prebleed samples. One mouse treated with MSA-IL-22 was excluded from all analyses in this figure, as pathology indicated an infection. Significance levels (∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗p < 0.001) are shown for mice treated with MSA-IL-22 relative to those treated with MSA; significance levels (#p < 0.05) are shown for the untreated group relative to the MSA group. Mean indicated with SD error bars. AMLN, amylin liver nonalcoholic steatohepatitis; ANOVA, analysis of variance; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; IL, interleukin; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; LNP, lipid nanoparticle; MSA, mouse serum albumin; SD, standard deviation.

Absolute lipid parameters were similar in MSA-treated mice and untreated AMLN mice; however, the MSA-IL-22–treated mice consistently exhibited lower levels of triglycerides, HDL, LDL, and total cholesterol across the study period (Figure S2B). However, baseline levels of these parameters, especially HDL and triglycerides, were lower in the C57BL/6NTac mice treated with MSA-IL-22 than in other groups, which initially made interpretation challenging. To account for this variation, subsequent experiments included randomization with stratification according to baseline HDL cholesterol and triglyceride levels.

When normalized to baseline levels, relative LDL cholesterol levels in MSA-IL-22–treated mice were significantly lower than in MSA-treated mice from weeks 2 through 6, with triglyceride levels significantly lower at weeks 4 and 6 (Figure 2C). No significant differences were observed with relative HDL or total cholesterol concentrations.

3.3.2. Effects of MSA-IL-22 treatment on liver markers of MASLD, inflammation, and fibrosis

At the conclusion of the study, after 6 weeks of dosing, liver weight was reduced significantly in mice treated with MSA-IL-22 compared with those treated with MSA. Liver weight in mice treated with MSA-IL-22 was similar to that seen in mice fed a chow diet (Figure 3A). Analysis of liver morphology indicated the presence of microvesicular and macrovesicular steatosis in all AMLN-fed mice (Figure 3B). Mice in the MSA-IL-22 treatment group and control chow group had significantly less microvesicular steatosis than mice treated with MSA. Furthermore, significantly less macrovesicular steatosis was observed in mice fed a chow diet than in the untreated group that was fed AMLN (Figure 3C). Inflammation was significantly lower in mice treated with MSA-IL-22 than in the group treated with MSA, which unexpectedly had higher levels of inflammation than the untreated AMLN and control chow groups (Figure 3C). Unlike mice treated with MSA, those that received MSA-IL-22 did not present with liver hypertrophy; however, this difference did not reach statistical significance (Figure 3C). Liver tissue immunostaining indicated that mice in the MSA treatment group had the highest score of F4/80-positive macrophages, followed by the untreated AMLN group and the MSA-IL-22 group (Figure S2C, D). Liver fibrosis scores were generally low across groups, which was expected in mice fed an AMLN diet for 24 weeks; the lowest score was observed in the control chow group (Figure S2D).

Figure 3.

Effects of weekly MSA-IL-22 administration on liver health and expression of lipogenic and fibrotic marker genes in the livers of C57BL/6NTac mice. (A) Liver weights (g) were measured 72 h after the last dose in a 6-week treatment period in which MSA (n = 9) or MSA-IL-22 mRNA (n = 9) was administered at 0.5 mg/kg to male C57BL/6NTac mice fed an AMLN diet. An untreated AMLN group (n = 5) and a control chow group (n = 6) were included. For comparisons between mice groups, liver weight in grams was transformed using a Box–Cox transformation [51]. The transformed liver weight was modeled as g(liver weights) = β0 + β1∗group; g(.) refers to the Box–Cox transformation. (B) Representative H&E-stained liver and epididymal adipose tissues were assessed and (C) scored for levels of microvesicular and macrovesicular steatosis, inflammation, and liver hypertrophy. Pairwise comparisons of these ordinal staining scores between mice groups were performed with Dunn's test following a significant Kruskal–Wallis nonparametric test. Holm's test was used to control for family-wise error rate within each liver histology score and cross-adjusted across all 6 different scores tested, including scores from Bonferroni correction. Only the statistically significant results compared with those derived from MSA-treated mice are shown in the figure. Adipose hypertrophy is represented as average adipocyte diameter in μm and was analyzed using a 1-way ANOVA. (D) Differential expression levels of selected fibrosis- and lipogenesis-associated genes were determined relative to Rpl19 expression using RT-qPCR. A linear mixed-effects model for all genes in this study, with 2-way interactions between genes and mice groups as fixed effects and mouse-specific random effects, was fitted. nlme R package [49] was used to model heterogeneous variances in genes and groups. Significance levels (∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗p < 0.001) that were appropriately adjusted for multiple comparisons are shown relative to mice treated with MSA. One mouse treated with MSA-IL-22 was excluded from all analyses in this figure, as pathology indicated an infection. Mean values with SD error bars are indicated. AMLN, amylin liver nonalcoholic steatohepatitis; ANOVA, analysis of variance; H&E, hematoxylin and eosin; IL, interleukin; MSA, mouse serum albumin; RT-qPCR, reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction; SD, standard deviation.

Analysis of epididymal adipose tissue morphology by H&E staining indicated significantly less adipose hypertrophy in the MSA-IL-22–treated and control chow groups than in the MSA-treated group (Figure 3B, C). In general, the tissue histology of mice treated with MSA-IL-22 more closely resembled that of mice fed a control chow diet.

Hepatic expression of genes encoding biomarkers of fibrosis and lipogenesis was assessed by RT-qPCR (Table S2). Similar to the control chow group, mice treated with MSA-IL-22 showed a minimal fold change in expression levels of markers of fibrosis and inflammation, namely collagen alpha-1(I) chain (Col1a1), collagen alpha-2(I) chain (Col1a2), and tumor necrosis factor (Tnf), and these levels were significantly different from those in the MSA-treated group (Figure 3D).

Notably, MSA-IL-22–treated mice had significantly higher phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase 1 (Pck1) expression than the MSA-treated group. Mice treated with MSA-IL-22 had significantly lower expression levels of acetyl-CoA carboxylase 1 (Acaca), diacylglycerol O-acyltransferase 1 (Dgat1), and liver-derived transmembrane glycoprotein NMB (Gpnmb) than the MSA-treated group (Figure 3D). Additionally, mice treated with MSA-IL-22 had increased expression of the hepatic antioxidant enzymes metallothionein-1 (Mt1) and metallothionein-2 (Mt2) (Figure 3D). Compared with MSA-treated mice, expression levels of apolipoprotein A-I (Apoa1) and programmed cell death 1 ligand 1 (Cd274) were significantly increased and decreased, respectively, in the MSA-IL-22–treated group (Figure S3).

Evaluation of fibrosis- and lipogenesis-associated gene expression using the NanoString Metabolic Pathway Panel confirmed the RT-qPCR results, including increased and reduced expression of Pck1 and Acac, respectively (Table S3). The analysis of this panel also indicated reduced expression of acyl-CoA desaturase 1 (Scd1) and fatty acid synthase (Fasn) (Figure S4), which are other key fatty acid synthesis–related genes.

3.3.3. Effects of MSA-IL-22 treatment on serum cytokines and liver enzymes

Analysis of serum cytokine levels (Figure S5A) showed no significant differences among the treatment groups in most cases, with the exception of increased levels of CCL4, CCL5, CXCL9, and TNF-α observed in the MSA treatment group. Interestingly, levels of these cytokines were not elevated in the sera of mice treated with MSA-IL-22. Levels of ALT and AST enzymes were measured to assess liver function (Figure S5B); however, no changes were observed across treatment groups. As expected in an MASLD model, CRP levels were elevated in all groups treated with the AMLN diet (Figure S5B). However, no additional increase in CRP levels was noted following MSA-IL-22 treatment. Overall, these findings demonstrated that MSA-IL-22 treatment over 6 weeks improved measures of MASLD, including body weight, lipid metabolism, and lipogenic and fibrotic marker gene expression, in the mouse model of metabolic disease.

3.4. Effect of MSA-IL-22 treatment durability on body weight and lipid parameters

To evaluate the durability of changes in body weight and lipid parameters following MSA-IL-22 treatment, AMLN-fed male C57BL/6NTac mice were monitored for 3 weeks following the administration of 3 doses of MSA-IL-22 mRNA (0.5 mg/kg) on days 0, 7, and 14 (Figure 4A). Serum IL-22 protein levels remained constant on days 3, 10, and 17 (Figure 4B). After the third dose, body weight was significantly lower in mice treated with MSA-IL-22 than in those treated with MSA and was remarkably similar to that of the control chow mice for the entire duration of the study (Figure 4C). Food intake was initially lower in mice treated with MSA-IL-22 but subsequently increased and became comparable to that in mice treated with MSA and untreated AMLN mice within approximately 14 days of the administration of dose 3 (Figure 4D).

Figure 4.

Metabolic effects of weekly administration of 3 doses of MSA-IL-22 or MSA treatment in C57BL/6NTac mice fed an AMLN or chow diet. (A) Male C57BL/6NTac mice were fed an AMLN or chow diet from 6 weeks of age (week −18). LNP-encapsulated MSA or MSA-IL-22 mRNA was administered to mice fed an AMLN diet (n = 8 and n = 11, respectively) at 0.5 mg/kg weekly over 3 weeks on days 0, 7, and 14. Two untreated groups of mice (1 AMLN diet group [n = 9] and 1 chow diet group [n = 7]) were maintained in parallel. Sera were collected for ELISA and lipid analysis at the indicated time points. (B) Levels of IL-22 in sera from treated mice were measured 72 h after each administration on days 3, 10, and 17. (C) Body weight and (D) food intake were monitored through day 39 without additional treatment. Body weight (C) on day 1 was considered baseline for percentage normalization, as control group body weight was not measured at −20 and −13 days. Normalized body weight calculations were performed as mentioned previously (Figure 2 description). Body weight assessed in both grams and percentage were analyzed with a linear mixed model, with time point– and group–level interactions as fixed effects and mouse-specific random effects to account for repeated measures over time points. Heterogenous variances observed across groups and time points were also modeled [49]. (D) For analysis of food intake, a model similar to that of body weight was fitted but with heterogeneous variances across groups specific to each time point. (E) Total cholesterol, LDL and HDL cholesterol, and triglyceride levels were measured after sera collection. For serum lipid analyses in mg/dL, a Bayesian approach was chosen [50] over frequentist to better account for data points falling below the assay limit of detection. Time point–, serum-, and group-specific linear terms, as well as their interactions, were used to model population-level effects, and mouse-level varying effects were specified to account for repeated measures. Heterogeneous variance observed across time points and groups per serum were accounted for by estimating residual variance to change linearly in time points, serum, and groups. Significance levels (∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗p < 0.001) are shown for MSA-IL-22–treated mice relative to MSA-treated mice; significance levels (δ p < 0.05; δδ p < 0.01) are shown for control mice relative to MSA-treated mice; significance levels (#p < 0.05; ##p < 0.01) are shown for the untreated group relative to the MSA-treated group. Mean values with SD error bars are indicated. AMLN, amylin liver nonalcoholic steatohepatitis; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; IL, interleukin; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; LNP, lipid nanoparticle; MSA, mouse serum albumin; SD, standard deviation.

Total cholesterol, LDL and HDL cholesterol, and triglyceride levels decreased rapidly following the first dose of MSA-IL-22, with only HDL cholesterol and triglyceride levels returning to comparable levels in the MSA-treated mice and the untreated AMLN and control chow groups 17 days after dose 3 (Figure 4E). Variability in nonfasted triglyceride levels between groups prior to treatment limited the interpretation of triglyceride results. LDL cholesterol levels stabilized after the initial decrease, with significantly lower levels on days 25, 32, and 39 in MSA-IL-22–treated mice compared with MSA-treated mice fed AMLN diets. As expected, serum LDL cholesterol levels were below the level of detection in the control group of mice that was fed chow diets, given the low cholesterol content of this diet and generally very low levels of LDL in wild-type mice.

Durability of the improvements in body weight and lipid parameters were further evaluated following administration of MSA-IL-22 every other week on days 0, 14, and 28 (Figure S6A). Serum MSA-IL-22 levels remained reasonably constant across days 3, 17, and 31 (Figure S6B). Similar to weekly MSA-IL-22 dosing, every-2-week dosing resulted in reduced body weight after the first dose, with a significant reduction observed in mice treated with MSA-IL-22 compared with mice treated with MSA by day 39 (Figure S6C). Blood lipid levels were significantly reduced after the first dose of MSA-IL-22 compared with MSA; however, total cholesterol and HDL cholesterol levels were comparable by day 39 (Figure S6D). Histological analyses of liver sections indicated the presence of steatosis across all groups except the control chow group (Figure S6E) and no differences between MSA-treated and MSA-IL-22–treated mice after 3 doses. Adipose tissue morphology was also similar between treatment groups. Gene expression analyses indicated no significant changes in the expression of markers of fibrosis and lipogenesis between mice treated with MSA-IL-22 or MSA (Figure S6F); this suggests that dosing with MSA-IL-22 every other week was not sufficient to beneficially affect hepatic lipid deposition, although it was sufficient to reduce body weight in AMNL-fed mice to a range similar to that in the control chow mice for the duration of the study.

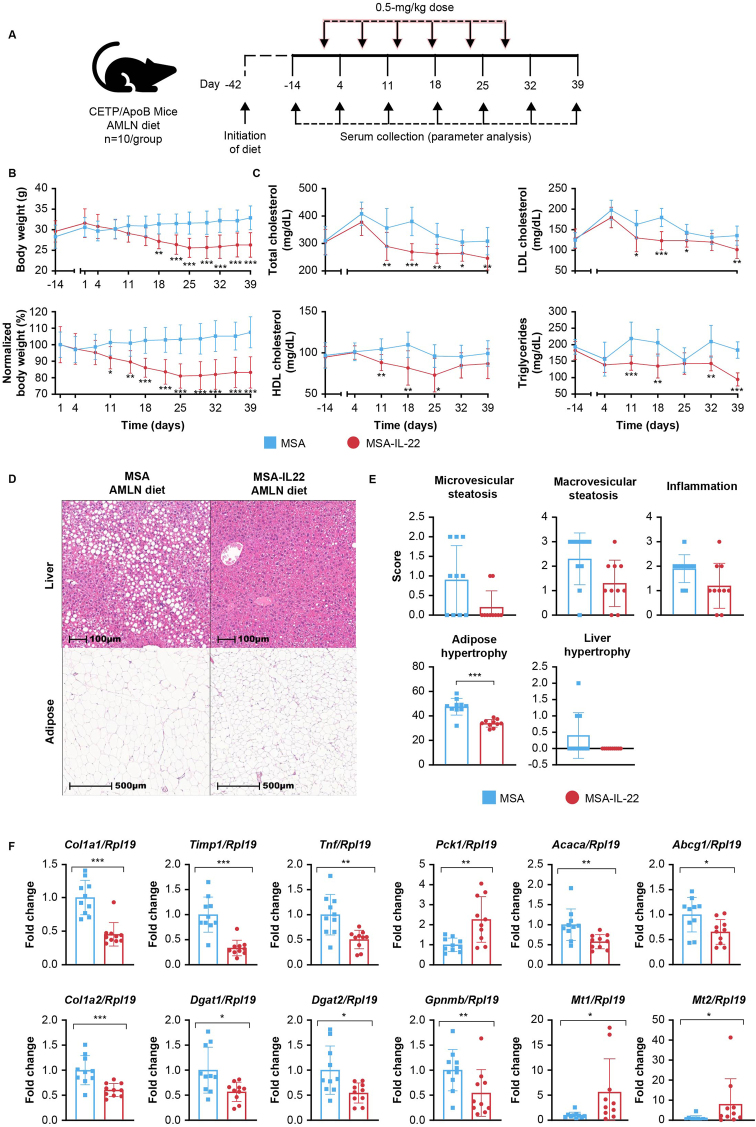

3.5. MSA-IL-22 treatment improves body weight, adipose tissue hypertrophy, hepatic steatosis, and lipid metabolism in the CETP/ApoB mouse model

CETP/ApoB transgenic mice express both human APOB and human CETP and thereby display a lipoprotein profile that more closely resembles that of humans, with elevated LDL and decreased HDL cholesterol levels [55]. This mouse model was implemented to investigate the potential benefits of MSA-IL-22, and the effects of 6 weekly doses of MSA-IL-22 were evaluated (Figure 5A). IL-22 protein serum levels were detectable 72 h after each dose and remained stable over the 6 weeks of intervention (Figure S7A). Reductions in body weight were observed following administration of the first dose of MSA-IL-22 mRNA, and body weight remained significantly lower than that in mice treated with MSA through day 39 (Figure 5B). Random assignment of CETP/ApoB mice before treatment allowed for clear delineation of significantly lower total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, and triglyceride levels in mice treated with MSA-IL-22 from day 11 through day 39 compared with mice treated with MSA (Figure 5C). HDL cholesterol levels were significantly lower in the MSA-IL-22 treatment group from days 11–25, returning to levels comparable to those in the MSA treatment group in the last 2 weeks of the study. Ratios of LDL to HDL and LDL to total cholesterol were similar between the MSA and MSA-IL-22 groups (Figure S7B). Histological analyses indicated a trend toward reduced microvesicular and macrovesicular steatosis and inflammation in the livers of MSA-IL-22–treated mice compared with the MSA-treated group (Figure 5D–E). Furthermore, adipose hypertrophy was significantly lower in mice treated with MSA-IL-22 than in those treated with MSA (Figure 5D–E). No significant difference was observed in liver F4/80-positive macrophages between the 2 groups (Figure S7C, D). Hepatic expression levels of collagen alpha-1(I) chain (Col1a1), collagen alpha-2(I) chain (Col1a2), metalloproteinase inhibitor 1 (Timp1), tumor necrosis factor (Tnf), acetyl-CoA carboxylase 1 (Acaca), diacylglycerol O-acyltransferase 1 (Dgat1), diacylglycerol O-acyltransferase 2 (Dgat2), and ATP-binding cassette sub-family G member 1 (Abcg1) were significantly lower, while Pck1 expression was significantly increased in mice treated with MSA-IL-22 compared with those treated with MSA (Figure 5F). Additionally, mice treated with MSA-IL-22 had significantly lower expression levels of Gpnmb and significantly higher levels of Mt1 and Mt2 (Figure 5F); these findings are consistent with those seen in C57BL/6NTac mice fed an AMNL diet and treated with MSA-IL-22 (Figure 3).

Figure 5.

Metabolic effects of weekly administration of MSA-IL-22 or MSA treatment in CETP/ApoB mice fed an AMLN diet. (A) Male CETP/ApoB mice were fed an AMLN diet from day −42. LNP-encapsulated MSA or MSA-IL-22 mRNA was administered at 0.5 mg/kg weekly for 6 weeks to mice fed an AMLN diet (n = 10 mice/group), starting on day 0. Sera were collected for ELISA and lipid analysis at the indicated time points. (B) Body weight and (C) total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, and triglyceride levels were monitored through day 39. Body weight (B) at day −14 was considered as baseline for percentage normalization, and normalization was performed as mentioned previously (Figure 2 description). A similar model (described in Figure 4C) was fitted to both body weight in grams and percentage data. All lipid (C) values were above the assay limit of detection; therefore, data were fitted to a linear mixed model with time point–, group-, and lipid–level interactions as fixed effects and mouse-specific random effects to account for repeated measures across time points and lipids. Heterogeneous variances across groups, time points, and lipids were also accounted for [49]. (D) Representative H&E-stained liver and adipose tissue were assessed between mice treated with MSA and MSA-IL-22 and graded for (E) microvesicular and macrovesicular steatosis, inflammation, and liver hypertrophy, as mentioned previously [41]. Group comparisons of the ordinal staining scores were performed with Dunn's test following a significant Kruskal–Wallis nonparametric test. Holm's adjustment was implemented across all 5 different scores tested (including f4/80 score from [D]). Adipose hypertrophy is represented as average adipocyte diameter in μm and is analyzed using 1-way ANOVA. (F) Differential expression levels were determined relative to Rpl19 expression using RT-qPCR for a select set of fibrosis- and lipogenesis-associated genes in mice treated with MSA or MSA-IL-22. A linear mixed-effects model was fitted for all genes (including genes from Figure S7 [E]), with gene- and group–level interactions as fixed effects and mouse-specific random effects; the model also accounted for heterogeneous variances in genes and groups [49]. Significance levels (∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗p < 0.001) were determined using the appropriate adjustment methods. Mean values with SD error bars are indicated. AMLN, amylin liver nonalcoholic steatohepatitis; ANOVA, analysis of variance; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; H&E, hematoxylin and eosin; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; IL, interleukin; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; LNP, lipid nanoparticle; MSA, mouse serum albumin; RT-qPCR, reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction; SD, standard deviation.

Differential expression analysis of other selected genes of interest found no differences between the MSA and MSA-IL-22-treated groups (Figure S7E). Analysis of serum cytokine levels revealed that levels of CCL4, CCL5, CSF-3, CXCL9, IFN-γ, and IL-12p70 were significantly lower in the MSA-IL-22 group than in the MSA group (Figure S7F). ALT levels were lower in MSA-IL-22–treated mice than in MSA-treated mice, while serum AST levels were comparable between groups (Figure S7G).

The effects of MSA-IL-22 treatment in the CETP/APOB mouse model are consistent with those in the C57BL/6NTac model, further supporting its potential as a therapeutic for metabolic syndrome and associated comorbidities in human populations.

3.6. MSA-IL-22 treatment has minimal impact on body weight or lipid profiles in nonobese CETP/ApoB mice that are fed a chow diet

To exclude the possibility of unwanted weight loss in lean mice, the effects of weekly administration of MSA-IL-22 or MSA mRNA on body weight and lipid profiles were also evaluated in CETP/ApoB mice fed a chow diet (Figure S8A). IL-22 protein serum levels were comparable between mice fed AMLN and chow diets and remained stable over the 6 weeks of the intervention (Figure S7A, H). Body weight was relatively stable in mice treated with MSA-IL-22; however, weight increased modestly over time in mice treated with MSA (Figure S8B). Total and HDL cholesterol levels in mice treated with MSA-IL-22 were consistently higher than those in mice treated with MSA. LDL cholesterol levels and LDL-to-HDL and LDL-to-total cholesterol ratios remained relatively similar between treatments through day 39 (Figure S8C, D). No significant differences were observed in any cytokine levels (Figure S8E) or AST levels between the MSA and the MSA-IL-22 treatment groups. However, a significant decrease in ALT levels was noted following MSA-IL-22 treatment (Figure S8F).

3.7. MSA-IL-22 treatment via IV and IM routes of administration in C57BL/6NTac mice fed an AMLN diet for 34 weeks improves body weight, liver function, and lipid profile

To further evaluate the effects of MSA-IL-22 treatment in a model of more severe metabolic syndrome, MSA-IL-22 mRNA-LNP was administered to C57BL/6NTac mice fed an AMLN diet for 34 weeks. Given the potential advantages and disadvantages of different drug administration routes [56], IV and IM administration routes were compared in this model. There was no visible local reaction observed at the site following the intramuscular administration. In these mice, which were 40 weeks old at the start of the study and had severe metabolic syndrome, body weight decreased within a few days of the initial 0.5-mg/kg IV injection of MSA-IL-22, and weight continued to decrease significantly throughout the 7-week study. A significant decrease in weight was also observed when MSA-IL-22 was administered as a 0.1-mg/kg IM dose (Figure S9A); therefore, there is potential to explore alternative routes of administration at a lower dose.

Daily caloric intake transiently decreased during the first 3 weeks by approximately 50% in the IV-administered group and mildly declined in the IM-administered group. However, by the end of the study, caloric intake was identical across all groups (Figure S9B, Table S5, Table S6). The total cumulative energy intake was lowest in control chow mice, followed by the MSA-IL-22 IV-administered and then MSA-IL-22 IM-administered groups (Figure S9C, Table S4).

After 7 weeks, reductions in overall weight, liver weight, and epididymal white adipose tissue (eWAT) weight (Figure S9D) were observed in both the IV and IM MSA-IL-22 treatment groups. Weight gain was significantly reduced in the MSA-IL-22 IV group and IM group compared with the MSA-treated group (Figure S9D). The liver weight/body weight ratio was unaffected by MSA-IL-22, suggesting that the liver weight reduction was driven by the overall body weight loss. Conversely, the eWAT weight/body weight ratio was significantly lower in the MSA IL-22 IV group than in the MSA-treated group.

Metabolic efficiency, defined as weight gain per caloric intake over the course of the study, was significantly reduced in both MSA-IL-22 treatment groups compared with the MSA-treated group, with the IV group showing the most pronounced effect (Figure S9E). This could suggest that, in addition to lowering food intake, MSA-IL-22 increases energy expenditure. Following prolonged feeding of the AMLN diet in these animals, ALT levels were notably elevated. However, in the group treated with MSA-IL-22 IV, ALT levels were remarkably similar to those in the control chow group by the end of the study. Despite lower potency than IV administration, IM treatment also significantly reduced ALT levels (Figure S9F). Total cholesterol, HDL, LDL, and triglyceride levels were reduced in the group treated with MSA-IL-22 IV compared with the MSA-treated and untreated AMLN groups (Figure S9G). Collectively, these results strongly suggest that in mice with a more severe metabolic syndrome disease state, MSA-IL-22 treatment improves liver function, body weight, and lipid profile.

3.8. Assessing hepatic and intestinal signaling pathways through MSA-IL22 with Saa1/Saa2 and Reg3g as biomarkers

We evaluated the role of MSA-IL-22 in mediating hepatic and intestinal epithelial signaling by testing hepatic serum amyloid A1 and A2 (Saa1/Saa2) gene expression as markers for hepatic IL-22 signaling and assessing the induction colonic expression of Regenerating islet-derived protein 3 gamma (Reg3g) for intestinal signaling. We administered MSA and MSA-IL22 to female C57BL/6NCrl mice and collected liver and colon samples at 6-, 24-, and 72-hours post-treatment for gene expression analysis (Figure S10).

Our results showed a notable decrease in hepatic Saa1/2 expression at 6 h, followed by a strong induction at 72 h, indicating a temporal effect that culminated in increased hepatic expression of SAAaa1/2 (Figure S10A). It is well established that IL-22 induces the production of circulating SAA released by the liver [57], and our study confirmed that MSA-IL-22 also stimulates this pathway. Additionally, we observed a significant increase in Reg3g expression in the colon as early as 6 h after injection which was sustained until 72 h after injection (Figure S10B), suggesting a potent response from the intestinal epithelium to MSA-IL-22. IL-22 is known to be a crucial regulator of intestinal microbial communities and maintains intestinal homeostasis by mitigating harmful inflammatory responses in adults [57]. It promotes the expression of several antimicrobial factors, including regenerating islet-derived proteins (Reg) REG3B and REG3G, β-defensins, and S100 proteins [58]. Our experiments confirmed that MSA-IL22 treatment also led to increased expression of Reg3b at various time points, highlighting the intestinal epithelium as a critical site for MSA-IL-22 activity. In addition to this finding, we examined the expression of Interleukin-22 receptor alpha 2 (IL-22ra2), also referred to as the IL-22 binding protein (IL-22BP) [59], in the colon (Figure S10C). IL-22RA2 functions as a soluble, naturally occurring decoy receptor that binds IL-22 with high affinity but does not transmit a signal. By binding to IL-22, IL-22RA2 effectively neutralizes IL-22 by preventing it from interacting with the functional IL-22 receptor complex. Our findings indicated that MSA-IL-22 does not appear to alter the expression of this endogenous inhibitor of IL-22 signaling.

3.9. Association between MSA-IL-22 and increased PYY levels, reduced food intake, and improvement in body weight gain and glucose tolerance

Body weight was significantly reduced in obese C57BL/6NTac mice fed an AMLN diet and treated with MSA-IL-22, which may partially be explained by transient decreases in food intake. IL-22 has previously been shown to increase serum levels of the anorexigenic hormone PYY, which is predominantly produced by L cells in the ileum and colon, other enteroendocrine cells throughout the intestine, and pancreatic islet cells [11,60]. Therefore, weight gain, energy intake, and metabolic efficiency were assessed following the administration of 2 doses of MSA or MSA-IL-22 (day 0 and day 7) to C57BL/6Ntac mice fed either the chow diet or AMLN diet (Figure 6A). Additionally, PYY levels were evaluated after fasting for 12 h and 1 h after refeeding to investigate serum PYY as a potential mechanistic link between MSA-IL-22 and changes in body weight and lipid profiles. Reductions in body weight were observed after the administration of the first dose of MSA-IL-22; these reductions became significant compared with the findings observed in MSA-treated control groups after 2 doses for both groups of mice fed the AMLN and chow diets (Figure 6B, C). The control chow mice in this study had a higher body weight than the CETP/ApoB mice (Figure 5 and Figure S8); therefore, the weight loss is most likely an effect of loss of excessive adipose tissue in the control mice.

Figure 6.

Effects of 2 doses of MSA-IL-22 or MSA treatment on body weight, blood glucose, food intake, and PYY in C57BL/6NTac mice fed an AMLN diet. (A) Two doses of LNP-encapsulated MSA or MSA-IL-22 mRNA (0.5 mg/kg each) were administered 1 week apart (days 0 and 7) to male C57BL/6NTac mice fed an AMLN or chow diet from 6 weeks of age (week −18; n = 10 mice/group). One day after dose 2 (day 8), mice were fasted for 12 h, followed by a 1-hour ad libitum refeeding period. Sera were collected before and after the fasting period and after refeeding. (B) Body weight was measured on days 1, 3, 7, 8, and 9 and analyzed by fitting a linear mixed-effects model with diet-, group-, and time point–specific interactions as fixed effects and mouse-specific random intercepts to account for repeated measures over time. Time point–specific heterogenous variances observed between MSA-IL-22 and MSA groups and between AMLN and chow diet groups were also modeled [49]. Mean values with SD error bars are indicated. Significance levels are shown for MSA-IL-22 relative to the MSA groups for AMLN (∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗p < 0.001) and chow (δδ p < 0.01) diet. (C) Differential weight gain with respect to day 1 was calculated on day 8 per mouse. (D) PYY levels were determined using ELISA. Serum PYY analyses excluded 3 mice in the MSA group and 1 mouse in the MSA-IL-22 group due to insufficient sample volume after fasting. Both fasting and refeeding PYY levels were analyzed together with diet-, group-, and PYY measure–specific interactions as fixed effects, and mouse-specific random effects were used to account for repeated measures over both PYY levels [49]. (E) food intake was measured as the total intake throughout the study duration, and (F) energy intake was calculated as food intake multiplied by metabolizable energy content in the diet. (G) Metabolic efficiency was calculated as the average body weight gained per cage in mg over energy intake (kcal) of that respective cage. Note that food intake, energy intake, and metabolic efficiency were measured per cage; each cage housed 2 mice, as previously described. (H) Fasting and (I) refeeding glucose levels were determined by glucometry. All these measures were analyzed independently using a 2-way ANOVA [48], with diet- and group-specific interactions. Significance levels (∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗p < 0.001; not significant [ns]) in this figure are shown relative to MSA mice from the respective diet group. AMLN, amylin liver nonalcoholic steatohepatitis; ANOVA, analysis of variance; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; IL, interleukin; LNP, lipid nanoparticle; MSA, mouse serum albumin; PYY, peptide YY; SD, standard deviation.

After fasting and refeeding, PYY levels were significantly elevated in mice treated with MSA-IL-22 compared with mice treated with MSA, irrespective of diet (Figure 6D). Congruent with the well-documented role of PYY in appetite suppression [61], food intake and thereby energy intake were reduced in mice treated with MSA-IL-22 that were fed the AMLN diet but not in those fed the chow diet throughout the study (Figure 6E, F). Furthermore, metabolic efficiency, an indicator of the ability to store ingested energy, was reduced in mice treated with MSA-IL-22 irrespective of diet (Figure 6G), suggesting that elevated energy expenditure, in addition to reduced food intake, might contribute to the weight loss observed in these mice. The significant reduction in blood glucose levels after fasting and refeeding in mice treated with MSA-IL-22 and fed an AMLN diet (Figure 6H, I) further emphasizes the beneficial effects of MSA-IL-22 on metabolic parameters. No effects on glucose levels were observed in mice fed a chow diet, which is consistent with an absence of insulin resistance at baseline in these mice.

To further explore the effects of MSA-IL-22 treatment on glucose homeostasis, glucose tolerance tests were performed following the weekly administration of MSA or MSA-IL-22 for 2 weeks in male C57BL/6Ntac mice fed an AMLN or chow diet (Figure 7A). MSA-IL-22 treatment was associated with a significant reduction in glucose levels 30, 60, and 120 min after intraperitoneal glucose delivery in mice fed an AMLN diet but only a slight decrease in the mice fed a chow diet (Figure 7B, C). Consistent with these observations, the area under the curve, a readout for the total blood glucose excursion during the glucose tolerance test, was significantly lower in AMLN-fed mice that were treated with MSA-IL-22 than in those treated with MSA (Figure 7D). Overall, these findings show that, in addition to normalizing body weight, reducing hyperphagia, improving dyslipidemia, and ameliorating liver steatosis and markers of inflammation and fibrosis, treatment with MSA-IL-22 significantly improved glucose tolerance in obese mice.

Figure 7.

Effects of 2 doses of MSA-IL-22 or MSA treatment on glucose tolerance in C57BL/6NTac mice fed an AMLN diet. (A) Two doses of LNP-encapsulated MSA or MSA-IL-22 mRNA (0.5 mg/kg each) were administered 1 week apart to male C57BL/6NTac mice fed either an AMLN diet (n = 10/group) or chow diet (n = 8 for MSA; n = 9 for MSA-IL-22) from 6 weeks of age (week −18). On day 8 (1 day after dose 2), mice were fasted for 6 h, followed by the intraperitoneal administration of glucose (2 mg/kg). Glucose tolerance was determined in (B) mice fed a chow diet and (C) mice fed an AMLN diet by measuring blood glucose levels after the fasting period (0 min) and 15, 30, 60, and 120 min after glucose administration. Glucose tolerance in (B) and (C) were analyzed together with a linear mixed-effects model with diet-, group-, and time point–level interactions as fixed effects and mouse-specific random effects to account for repeated measures over time points. Heterogenous variances observed across groups, diets, and time points were also modeled [49]. (D) Area under the curve of the glucose traces for the MSA and MSA-IL-22 group as shown in mice fed a chow (B) and an AMLN diet (C) are compared in this panel. A linear model with diet- and group–level interactions as covariates was fitted to this data. Significance levels (∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗p < 0.001; not significant [ns] in this figure are shown relative to MSA mice from the respective diet group. Mean values with SD error bars are indicated. AMLN, amylin liver nonalcoholic steatohepatitis; AUC, area under the curve; IL, interleukin; IP, intraperitoneal; LNP, lipid nanoparticle; MSA, mouse serum albumin; SD, standard deviation.

4. Discussion

Metabolic disease is characterized by the presence of various obesity-associated systemic metabolic disturbances, including type 2 diabetes and MASLD; it remains a growing health concern and is an important contributor to global mortality rates [1,2,5,6]. The potential for IL-22 to treat these conditions is underpinned by its involvement in glucose and lipid metabolism, with previous studies linking IL-22 treatment with decreased weight gain, protection against alcohol-induced liver damage, upregulation of hepatic antioxidant enzymes, and enhanced liver regeneration [11,[20], [21], [22], [23], [24]]. The C57BL/6Ntac mouse model, conditioned with a lipid- and carbohydrate-rich diet such as AMLN, develops metabolic and liver histopathologic features of MASLD [40,41], whereas the CETP/ApoB mouse model expresses a lipoprotein profile similar to that of humans [55]. Our study demonstrated that administration of an LNP-encapsulated IL-22 in metabolic disease C57BL/6Ntac and CETP/ApoB mouse models ameliorated the effects of an AMLN (high-fat, high-carbohydrate) diet and significantly improved lipid and glucose metabolism, obesity, and symptoms of MASLD.

The clinical utility of IL-22 has been limited by its relatively short serum half-life, which is usually <2 h [13]. One approach to prolonging the half-life is fusion of the IL-22 polypeptide with a protein that has an extended serum half-life, such as immunoglobulin or serum albumin; such a strategy could be particularly beneficial when considering the use of IL-22 in treating metabolic diseases. The fusion protein approach has been successfully used elsewhere to enhance the half-life of other therapeutic candidate cytokines [28,29,62]. The covalent linking of serum albumin does not result in steric hindrance that is associated with other linkage proteins or domains (e.g., fragment crystallizable domains); however, it increases the half-life of short-lived species, such as glucagon-like peptide-1, from a few minutes to approximately 1 week [27]. The improved half-life of N-linked MSA-IL-22 in our study was evident from stable serum levels over a week following administration of the LNP-encapsulated therapeutic.

Our study in C57BL/6Ntac mice demonstrated that weekly administration of LNP-encapsulated N-linked MSA-IL-22 mRNA over 6 weeks significantly reduced body weight in mice with preexisting diet-induced MASLD. Elevated IL-22 protein levels were detected in liver tissue after MSA-IL-22 mRNA treatment, which is consistent with the known expression sites and hepatoprotective effects of IL-22 [13,15]. Reductions in steatosis, inflammation, and hypertrophy of the liver and epididymal adipose tissue, along with improvements in serum lipid profiles and glucose tolerance, were also observed in these mice; this suggests a parallel improvement in metabolic health. Even in mice with more severe disease, MSA-IL-22 treatment improved the condition, with reductions in liver weight and eWAT and decreased ALT levels, suggesting improved liver health and possible increased lipolysis and energy expenditure.

The beneficial effects of MSA-IL-22 mRNA treatment in the liver seen in the C57BL/6Ntac mouse studies were further supported by observed changes in hepatic gene expression in mice treated with IL-22. In C57BL/6Ntac mice treated with MSA-IL-22, hepatic Pck1 expression levels were elevated; Pck1 has been shown to play an important role in MASLD, as its downregulation is associated with murine and human nonalcoholic steatohepatitis [63]. GPNMB in circulation has been shown to be a promising biomarker for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and MASLD progression [64,65]. Consistent with the decrease in overall MASLD severity, Gpnmb expression levels were significantly lower in MSA-IL-22–treated mice than in MSA-treated mice. Lower expression of genes involved in lipogenesis were also observed, namely those of Acaca, the first enzyme in the de novo lipogenic cascade; Dgat1, an enzyme catalyzing the last step of triglyceride synthesis [[66], [67], [68], [69], [70]]; Scd1, a central lipogenic enzyme [71]; and Fasn, an inhibiting enzyme of de novo lipogenesis [72], providing a potential mechanism underlying the reduced steatosis observed with MSA-IL-22 treatment. These results are congruent with previous findings that show that recombinant IL-22 is associated with the repression of triglyceride and cholesterol synthesis–associated genes and provides a protective effect against steatosis in an MASLD mouse model [11,73]. Additionally, mice treated with MSA-IL-22 in our study had an increased expression of the hepatic antioxidant enzymes Mt1 and Mt2; these findings are consistent with those of previous studies that suggest upregulation of Mt1 and Mt2 by IL-22 [20,22]. By inducing hepatic metallothionein, IL-22 may attenuate stress kinase activation, hepatic inflammatory functions, and reactive oxygen species production. In summary, reduction in hepatic expression of genes involved in fibrosis and lipogenesis was observed. These effects could be driven by direct effects of IL-22 on activity of these pathways [73,74] or be the result of reduced food intake and body weight, which could consequently improve insulin resistance, lipogenesis, and general metabolic health [75].

Dysregulation of lipid metabolism is a hallmark of metabolic syndrome, with increased serum LDL cholesterol and triglyceride levels contributing to the development of atherosclerosis and a subsequent increased risk for cardiovascular disease and stroke [76,77]. In this study, the metabolic disease models of C57BL/6Ntac and CETP-ApoB mice treated with MSA-IL-22 had reduced total cholesterol and HDL and LDL cholesterol levels compared with mice treated with MSA. In humans, cholesterol is predominantly transported in proatherogenic LDL particles, while HDL particles are the major cholesterol-carrying lipoproteins in mice [78]. This difference in cholesterol transport can influence outcomes in preclinical metabolic studies and limit the translatability of the findings. However, CETP/ApoB mice express a lipid metabolism that more closely resembles that in humans, and when these mice are fed a high-fat, high-cholesterol diet like the AMLN diet, they develop significantly more atherosclerotic lesions than controls [55]; therefore, this is an ideal model for evaluating treatments for hypercholesterolemia or LDL/HDL imbalance. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that demonstrates the effects of IL-22 overexpression in the CETP/ApoB animal model that received a high-fat, high-cholesterol diet. The results confirmed improvements in body weight and lipid metabolism as evidenced by reductions in total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, and triglyceride levels; HDL levels were only marginally affected. Interestingly, when MSA-IL-22 treatment was administered to the CETP/ApoB mice that were fed a regular chow diet, lipid levels and body weight were either comparable to or higher than that seen in CETP/ApoB mice fed the regular chow diet and treated with MSA. Together, these results indicate that the effects of MSA-IL-22 are relevant only in mice fed a high-fat, high-carbohydrate diet but not in those on a normal diet. Additionally, it is suggested that IL-22 treatment in humans may not lead to unwanted excessive weight loss in a lean patient.

Glucose intolerance and insulin resistance are further hallmarks of metabolic syndrome [79], and the development of type 2 diabetes is associated with an increase in overall cardiometabolic risk [80]. Treatment with MSA-IL-22 mRNA reduced fasting glucose levels and significantly improved glucose tolerance in an intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test in mice fed an AMLN diet, highlighting the involvement of IL-22 in glucose metabolism [81].

Collectively, these results indicate improvement of most major characteristics of metabolic syndrome, namely obesity, glucose intolerance, and dyslipidemia, and improvement in MASLD [79].

Similar to previous reports in animals treated with recombinant IL-22-Fc fusion protein [11], C57BL/6Ntac mice treated with MSA-IL-22 fed either an AMLN or chow diet displayed reduced food intake (significant for the AMLN diet only) and decreased metabolic efficiency; this is potentially linked to increased energy expenditure and might contribute to the beneficial weight loss effects of MSA-IL-22. Serum PYY levels after refeeding were significantly higher in mice treated with MSA-IL-22 irrespective of diet. The role of PYY as a suppressant of appetite and food consumption [61,82,83] is well documented, and IL-22 expression was detected in the intestine of mice treated with MSA-IL-22; therefore, these results suggest that, beyond the effects of MSA-IL-22 on the liver, there is a potential mechanistic link between MSA-IL-22 treatment and the corresponding reduction in body weight in C57BL/6 mice.

To further characterize the LNP-encapsulated MSA-IL-22 mRNA as a potential therapeutic, an IM formulation was investigated in the mouse model with a more severe disease profile. Remarkably, with the lower IM dose, body weight was reduced to values comparable to that in control chow mice. Moreover, a downward trend in percentage change in body weight was noted with IM administration of MSA-IL-22. These results suggest the possibility of reducing the dosage further, thereby enhancing the potential for a safer treatment profile and promoting the testing of different administration routes. These data are particularly compelling in the context of the phase 1 clinical trial of the recombinant human IL-22-Fc fusion protein (F-652), during which the administration route was switched from subcutaneous to IV because of adverse reactions [26]. Therefore, the opportunity to test different administration routes at lower doses presents possibilities for a safer and more patient-friendly treatment approach, and future research could concentrate on exploring alternative routes of administration and varying doses.

It is widely recognized that the specificity of IL-22 for receptors in epithelial cells, rather than immune cells, potentially reduces its therapeutic side effects [30]. Interestingly, in the present study, examination of serum cytokine and liver ALT and AST levels did not show any increase after 6 weeks of MSA-IL-22 treatment. An initial but temporary increase in the expression of selected cytokines was observed in mice treated with MSA alone but not in those treated with MSA-IL-22. This observation suggests that the fusion protein of MSA and IL-22 mitigates certain downstream effects of the MSA peptide, which may be related to IL-22 function.

5. Conclusion

In the present study, the effects of administration of LNP-encapsulated MSA-IL-22 mRNA in mouse models of metabolic disease showed favorable effects on body weight, lipid and glucose metabolism, and lipogenic and fibrotic marker gene expression. Despite these promising data, a constraint of the present study is the absence of extensive safety data. As part of the ongoing development of this therapeutic approach, additional safety studies in other species such as rats and cynomolgus monkeys are needed to further ascertain the safety profile of MSA-IL-22. Nonetheless, the data presented here demonstrate the robust, durable effects of MSA-IL-22 in both diet-induced and genetic mouse models of metabolic syndrome and support the use of the mRNA-LNP platform to develop and further improve IL-22 formulations as clinical candidates for metabolic diseases.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Susanna Canali: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Supervision, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Alexander W. Fischer: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Supervision, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation. Mychael Nguyen: Writing – review & editing, Investigation. Karl Anderson: Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Formal analysis. Lorna Wu: Writing – review & editing. Anne-Renee Graham: Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation. Chiaowen Joyce Hsiao: Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis. Chinmayi Bankar: Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis. Nancy Dussault: Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Formal analysis. Veronica Ritchie: Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Formal analysis. Meagan Goodridge: Writing – review & editing, Investigation. Todd Sparrow: Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Data curation. Allison Pannoni: Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Data curation. Sze-Wah Tse: Writing – review & editing, Investigation. Vivienne Woo: Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Formal analysis. Kaitlin Klovdahl: Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Formal analysis. Jared Iacovelli: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Project administration, Methodology, Conceptualization. Eric Huang: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Project administration.

Declaration of competing interest

At the time of this analysis, all authors were employees of Moderna, Inc. and may hold stock/stock options in the company.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Ariel Ridgway and Ying Fu for assistance with experimental work. Medical writing and editorial assistance was provided by Melissa Vetten, PhD, and Jessica Nepomuceno, PhD, of MEDiSTRAVA in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP 2022) guidelines, funded by Moderna, Inc., and under the direction of the authors. This work has been funded by Moderna, Inc. The funder was involved in the study design, collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, and writing of this article or the decision to submit it for publication.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molmet.2024.101965.

Contributor Information

Susanna Canali, Email: Susanna.Canali@modernatx.com.

Alexander W. Fischer, Email: alexanderfischer212@gmail.com.

Mychael Nguyen, Email: mychaelnguyen@gmail.com.

Karl Anderson, Email: Karl.Anderson@modernatx.com.

Lorna Wu, Email: lwu2@wellesley.edu.

Anne-Renee Graham, Email: Anne-Renee.Graham@modernatx.com.

Chiaowen Joyce Hsiao, Email: chiaowen.hsiao@modernatx.com.

Chinmayi Bankar, Email: Chinmayi.Bankar@modernatx.com.

Nancy Dussault, Email: Nancy.Dussault@modernatx.com.

Veronica Ritchie, Email: Veronica.Ritchie@modernatx.com.

Meagan Goodridge, Email: meaganlgoodridge@gmail.com.

Todd Sparrow, Email: Todd.Sparrow@modernatx.com.

Allison Pannoni, Email: allisonpannoni@gmail.com.

Sze-Wah Tse, Email: Eva.Tse@modernatx.com.

Vivienne Woo, Email: Vivienne.Woo@modernatx.com.

Kaitlin Klovdahl, Email: Kaitlin.Klovdahl@modernatx.com.

Jared Iacovelli, Email: jared.iacovelli@gmail.com.

Eric Huang, Email: Eyhuang01@gmail.com.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data to this article:

Data availability