Abstract

Fundamental to mammalian intrinsic and innate immune defenses against pathogens is the production of Type I and Type II interferons, such as IFN-β and IFN-γ, respectively. The comparative effects of IFN classes on the cellular proteome, protein interactions, and virus restriction within cell types that differentially contribute to immune defenses are needed for understanding immune signaling. Here, a multilayered proteomic analysis, paired with biochemical and molecular virology assays, allows distinguishing host responses to IFN-β and IFN-γ and associated antiviral impacts during infection with several ubiquitous human viruses. In differentiated macrophage-like monocytic cells, we classified proteins upregulated by IFN-β, IFN-γ, or pro-inflammatory LPS. Using parallel reaction monitoring, we developed a proteotypic peptide library for shared and unique ISG signatures of each IFN class, enabling orthogonal confirmation of protein alterations. Thermal proximity coaggregation analysis identified the assembly and maintenance of IFN-induced protein interactions. Comparative proteomics and cytokine responses in macrophage-like monocytic cells and primary keratinocytes provided contextualization of their relative capacities to restrict virus production during infection with herpes simplex virus type-1, adenovirus, and human cytomegalovirus. Our findings demonstrate how IFN classes induce distinct ISG abundance and interaction profiles that drive antiviral defenses within cell types that differentially coordinate mammalian immune responses.

Keywords: Interferon-beta, interferon-gamma, interferon-stimulated gene, parallel reaction monitoring, thermal proximity coaggregation, adenovirus, herpes simplex virus-1, HSV-1, human cytomegalovirus, HCMV

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

The cornerstone of mammalian intrinsic and innate immune defense against pathogens is the production of interferons (IFN), cytokines that stimulate anti-pathogen signaling pathways through the simultaneous expression of hundreds of interferon-stimulated genes (ISG). Type I IFNs (IFN-α, β, ε, κ, ω, and others) and Type II IFN (IFN-γ) have long been recognized for their pleiotropic and inhibitory properties against invading pathogens1, 2. These cytokines and ISGs not only serve autocrine roles for inhibiting pathogen replication, but also trigger cascades of paracrine signaling to alert nearby cells and professional cells in the innate and adaptive immune systems. In response to virus infections, unlike type I IFNs that are produced by most somatic cell types, the type II IFN-γ is primarily secreted by immune cell types. IFN-γ serves as a bridge between the innate and adaptive immune responses, stimulating the cytotoxic activity of natural killer cells and critically activating macrophages by polarization to promote viral clearance. It is now evident that, during a viral infection, host type I and II IFNs stimulate cell-autonomous and non-autonomous immunogenic pathways in both immune and non-immune cell types that suppress each stage of the viral life cycle (e.g., virion entry, viral mRNA and protein synthesis, genome replication, assembly, and egress)3.

Towards understanding cell-wide responses to cytokine stimulation in macrophages, studies have previously uncovered the proteome profiles upon cytokine treatments from the perspective of macrophage activation, uncovering strikingly dynamic plasticity in pro-inflammatory or anti-inflammatory characteristics4–9. For example, under the influence of concurrent IFN-γ and lipopolysaccharides (LPS), macrophages (Mφ) adopt a canonical M1 phenotype. In this activated state, they become potent producers of pro-inflammatory mediators, including tumor necrosis factor TNF, IL-1β, IL-6, and inducible nitric oxide synthase. Yet, from the perspective of innate immune responses to different IFN classes, we have yet to define the comparative proteomes of macrophages and relative impacts during different viral infections. Furthermore, whereas transcriptional responses to IFNs have been extensively investigated, comparative proteome level information is still limited in both immune and non-immune cell types. This is particularly valuable, as mRNA transcript levels have variable ability to predict cellular protein abundances10–13.

Protein-protein interaction studies in the context of IFN stimulation are only just coming to light. In HeLa cells, protein interaction network rearrangements upon Type I IFN-β stimulation were previously determined through protein correlation profiling and size exclusion chromatography, revealing how IFN-β reorganizes core translational complexes through the genesis of and remodeling by ISGs14. Given the breadth of ISG expression upon interferon stimulation, it has been theorized that many IFN-stimulated ISGs coordinate actions to control viral replication and spread3, 15, 16. Recent evidence alternatively has begun to emerge suggesting that most ISG-mediated virus restriction may be virus-specific and derived from a minimal subset of the hundreds of ISGs concomitantly induced by IFNs17–20. However, the extent to which specific ISGs are induced upon IFN stimulation and how these contribute to antiviral resistance amongst immune and non-immune cell types remain unclear and intense areas of research.

While many studies have examined the effects of IFN types on limiting virus infection, a primary focus has been on treatments with a singular IFN class. A transcriptomic study of type I and II IFNs in lung fibroblasts during Varicella-Zoster Virus (VZV) infection offers a glimpse into the comparative potency of IFN-α and IFN-γ in restricting virus infection21. In this study, IFN-γ-mediated induction of IRF1 was found to inhibit VZV replication more effectively than IFN-α-mediated induction of IRF9. To our knowledge, an investigation has yet to compare the effects of IFN classes on the cellular proteome and relative restriction of virus progeny production across multiple physiologically relevant cell types and viruses. Understanding these aspects adds an additional framework for contextualizing the relative contributions of specific ISGs and their abundance levels to inhibiting a given virus infection across cell types with distinct capacities to restrict infection. To begin addressing this gap, in this work, we integrated global proteome analyses with targeted mass spectrometry (MS), thermal proximity coaggregation-MS (TPCAMS), and molecular virology assays to determine how ISGs differentially contribute to host antiviral capacities between immune-modulatory cell types. In differentiated macrophage-like monocytic cells, we classified sets of both shared and distinct ISG proteins responsive to each IFN class. We orthogonally confirmed the relative protein alterations using parallel reaction monitoring (PRM) by developing a proteotypic peptide library for ISG markers induced by each IFN class. Additional comparison to stimulation with pro-inflammatory LPS helped to contextualize the observed IFN signatures. We further assessed ISG protein interactions upon IFN types I and II stimulation, observing maintenance of key ISG protein complexes across treatments. Subsequent comparison of macrophage-like monocytic cells to primary keratinocytes enabled us to identify relative ISG abundances, cytokine induction, and antiviral capacities of both cell types across infections with several ubiquitous human viruses. Infections with herpes simplex virus-1 (HSV-1), adenovirus (AdV), and human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) revealed cell type-dependent differences in virus progeny production, which were coincident with relative ISG protein levels. Altogether, our study provides insights into how IFN classes induce distinct ISG protein expression and interaction profiles that differentially drive host resistance to virus infections in cell types that engage in mammalian innate immunity.

Experimental Procedures.

Cell culture.

THP-1, pGK, Vero, MRC-5, and HEK293 cells were originally purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; TIB-202, PCS-200–014, CCL-81, CCL-171, and CRL-1573, respectively). THP-1 cells were maintained in RPMI-1640 medium (Gibco; 11875119) supplemented with 10 mM HEPES (Gibco; 15630080), 1 mM sodium pyruvate (Gibco; 11360070), and 0.05 mM 2-mercaptoethanol (Gibco; 21985023), 10% v/v fetal bovine serum (GeminiBio; 100–106), and 1% v/v Penicillin/Streptomycin (10,000 U/mL; Gibco; 15140–148). pGK cells were maintained in dermal basal medium (ATCC; PCS-200–030) supplemented with a keratinocyte growth kit (ATCC; PCS-200–040). Vero, MRC-5, and HEK293 cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM; Sigma-Aldrich; D5796) supplemented with 10% v/v fetal bovine serum (GeminiBio) and 1% v/v Penicillin/Streptomycin (10,000 U/mL; Gibco). All cells were cultured at 37°C and 5% CO2.

Viruses and infections.

The HSV-1 strain 17+ genome was isolated from a bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) encoding the full HSV-1 genome (pBAC-HSV-1) in E. coli strain GS1783, a gift from Dr. Beatte Sodeik (Hannover Medical School, Germany). HSV-1 virus stock was produced by electroporation of pBAC-HSV-1 into Vero cells and propagated at a low multiplicity of infection (MOI = 0.001) in Vero cells until 100% cytopathic effect was observed. Virus particles were purified by ultracentrifugation with a 10% Ficoll underlay and resuspended in 200 mM MES, 30mM Tris-HCl, 100 mM NaCl, pH 7.4. HSV-1 stock titers were determined by plaque assay in Vero cells. AdV serotype 5 (Ad5) was a gift from Dr. Jane Flint (Princeton University, USA). The virus was propagated in HEK293 and purified through two sequential rounds of ultracentrifugation with a cesium chloride gradient. Purified virus particles were stored in 40% v/v glycerol and Ad5 stock titers were determined by plaque assay in HEK293 cells. The HCMV strain TB40/E genome was isolated from a BAC, a gift from Dr. Thomas Shenk (Princeton University, USA). HCMV virus stock was produced by electroporation of pBAC-HCMV into MRC-5 cells and propagated at a low multiplicity of infection (MOI = 0.01) in MRC-5 cells until 100% cytopathic effect was observed. Virus particles were purified by ultracentrifugation with a 20% sorbitol underlay and resuspended in DMEM containing 10% v/v FBS and 1% v/v Pen/Strep. HCMV stock titers were determined by the tissue culture infectious dose method (TCID50).

For all virus stocks, at the indicated times, cell-associated virus was collected and released by three sequential freeze-thaw cycles using liquid nitrogen and a 37°C water bath (HSV-1, Ad5, and HCMV), then combined with cell-free virus (HSV-1 and HCMV) prior to purification by ultracentrifugation. To collect cell-associated virus, cell monolayers were scraped and pellets were centrifuged at 20,000 ×g for 5 min at 4°C to remove cell debris. All infections were performed in low volume at 37°C. After viral adsorption (1 h for HSV-1 and 2 h for both Ad5 and HCMV), the viral inoculum was aspirated and replaced with respective supplemented maintenance media for the duration of each experiment.

Virus progeny production assays.

All virus titer assays were performed with three biological replicates per condition. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 9 and significance was determined by Student’s t test (two-tailed): *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001.

HSV-1.

HSV-1 titers were determined by plaque assay. Cells were pre-treated as indicated and infections were performed at an MOI of 10. Viral inoculum was prepared by diluting the virus stock in respective supplemented maintenance media (pGK cells), or supplemented maintenance media with FBS adjusted to 2% v/v (THP-1 cells). At 24 hours post-infection (hpi), cells were scraped into the media and samples were freeze-thawed for three successive cycle using liquid nitrogen and a 37°C water bath. To remove cell debris, lysates were centrifuged at 20,000 ×g for 5 min at 4°C. Serial dilution of lysates in DMEM containing 2% v/v FBS and 1% v/v Pen/Strep was prepared to infect confluent monolayers of Vero cells. After 1 h viral adsorption at 37°C, viral inoculum was aspirated and replaced with 2% v/v FBS, 1% v/v Pen/Strep, and 1% methocel. Cell monolayers were incubated at 37°C until plaques were visible (~3 days), washed in PBS, and fixed and stained with 50% v/v methanol, 1% w/v crystal violet for 15 min. Virus titers were calculated as plaque-forming units (PFU/mL).

Adenovirus.

Ad5 titers were also determined by plaque assay. Upon indicated pre-treatment of cells, infections were performed at an MOI of 20. Viral inoculum was prepared by diluting the virus stock in respective supplemented maintenance media. At 72 hpi, virus was similarly prepared as described for HSV-1. Serial dilution of lysates was performed in DMEM containing 10% v/v FBS and 1% v/v Pen/Strep, and infections were performed on HEK293 cell monolayers. After 2 h viral adsorption at 37°C, viral inoculum was aspirated and replaced with DMEM containing 2% v/v FBS, 1% v/v Pen/Strep, and 0.45% w/v SeaPlaque agarose (Lonza; BMA50101). Cells were incubated at 37°C until plaques were visible (~7 days), after which a quarter volume of 10% w/v trichloroacetic acid was added to each well for 30 min at room temperature. Media was aspirated and cell monolayers were fixed and stained with 70% v/v methanol, 1% w/v crystal violet for 15 min. Virus titers were calculated as plaque-forming units (PFU/mL).

Human cytomegalovirus.

HCMV titers were determined by the TCID50 method. After the indicated cell pre-treatments, infections were performed at an MOI of 5. As with Ad5, viral inoculum was prepared by diluting the virus stock in respective supplemented maintenance media. At 120 hpi, virus was similarly prepared as described for HSV-1. Serial dilution of lysates was carried out in MRC-5 cell maintenance media and added to reporter plates of confluent MRC-5 cells. Virus titers were calculated as infectious units (IU/mL).

PMA differentiation and IFN stimulant treatments.

THP-1 cells were differentiated using 50 ng/mL PMA for 48 h for all proteomic analyses, or as indicated in immunoblot experiments, prior to IFN stimulation. Differentiation was observed by phase contrast microscopy using a Nikon Eclipse TS100 inverted phase contrast microscope and 20× objective. For all IFN stimulants, cells were treated for 24 h, unless otherwise indicated, in supplemented maintenance media with either 1% FBS (THP-1 cells), or fully supplemented maintenance media (pGK cells). For proteomic analyses, human IFN-β 1a (Sigma-Aldrich; IF014) and human IFN-γ (Biolegend; 570206) were used at 100 U/ml and 100 ng/ml, respectively, and LPS from E. coli K12 (InVivoGen; tlrl-eklps) was used at 200 ng/ml for the indicated durations of either 24 h or 48 h. Concentrations of 100 U/ml IFN-β and 100 ng/ml IFN-γ were selected based on the observed ability to induce known ISG protein expression in differentiated THP-1 cells (Fig. 1B-C) and on previous reports demonstrating activation of immune responses at these concentrations22–24. A concentration of 200 ng/ml LPS was selected based on prior proteomic characterization of a pro-inflammatory response in THP-1 cells at this concentration7. For immunoblot analyses, IFN-β, IFN-γ, human IFN-λ (Biolegend; 711204), and LPS were used at the indicated concentrations.

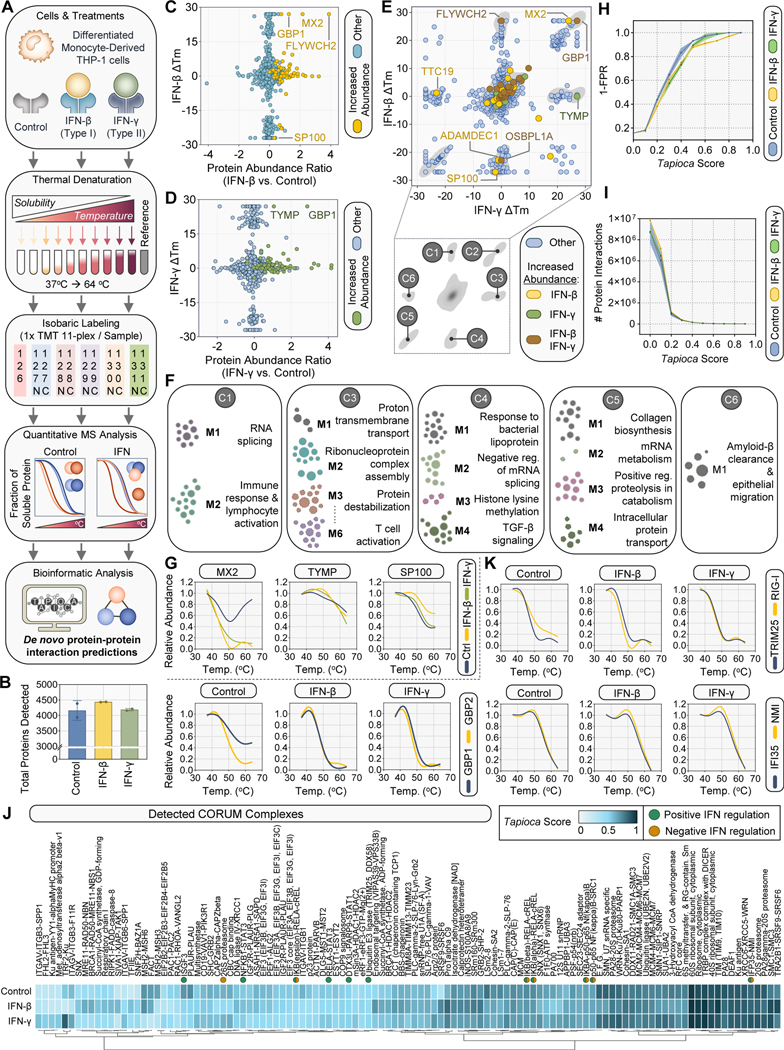

Fig 1. Type I and Type II IFNs drive differential inflammatory responses in macrophage-like monocytic cells.

(A) Workflow for characterizing inflammatory signatures of macrophage-like monocytic cells upon IFN stimulation. THP-1 cells were differentiated with PMA for 48 h prior to treatment for 24 h (Control, Type I IFN-β, Type II IFN-γ, or LPS). Whole cell proteome analysis by data-dependent acquisition (DDA) mass spectrometry (MS) with orthogonal targeted MS by parallel reaction monitoring established IFN response signatures (upon control, IFN-β, IFN-γ, or LPS treatments). Thermal proximity coaggregation and MS defined IFN-induced dynamics of protein-protein interactions (upon control, IFN-β, or IFN-γ treatments). Follow-up molecular and virology assays established the differential contributions of IFN classes in restricting virus progeny production.

(B-C) Optimization of PMA pre-treatment by immunoblot using reported ISGs IFIT3, RIG-I, and IRF1 in THP-1 cells upon subsequent stimulation with IFN-β (B) or IFN-γ (C) for 24 h.

(D and E) Scatter plots of relative protein abundances of IFN-β (B) and IFN-γ (C) treatments over the control. Peripheral x- and y-axis plots indicate the relative density of proteins. Gene ontology (GO) analyses of the significantly increased proteins were performed and representative GO terms are labeled, with -log10 p-values and fold enrichments relative to the whole human genome.

(F) Protein-protein interaction network of the significantly increased proteins from (D and E). Protein lists were combined with further annotation and sub-clustering for related functions. Protein nodes display the relative abundances between the IFN treatments as a ratio of their fold-change increases over the control. Edges represent STRING database-informed functional protein interactions.

Immunoblot analysis.

Cells were lysed in 1× Laemlli buffer (62.5 mM Tris-HCL, pH 6.8, 2% w/v SDS, 10% v/v glycerol, 0.02% w/v bromophenol blue, 100 mM DTT), boiled at 95°C for 10 min, and run through SDS-PAGE. PVDF membrane was used to transfer proteins by the wet transfer method. 5% w/v milk in PBS was used to block membranes in 1× tris-buffered saline, and blots were sequentially incubated with primary and secondary antibodies. Immunofluorescence detection was performed to visualize protein bands using the LI-COR Odyssey CLx imaging system. The following antibodies were used: α-MX1/2/3 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology; sc-166412), α-IFIT1 (Cell Signal Technology; 14769S), α-IFIT3 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology; sc-393512), α-RIG-I (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-376845), α-IRF1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology; sc-497), α-ISG15 (Thermo Fisher Scientific; 703131), and α-tubulin (Sigma-Aldrich; T6199). Secondary antibodies were conjugated with Alexa Fluor fluorophore (Life Technologies). Uncropped images of immunoblot membranes in this study are provided (Fig. S4).

Cytokine quantification by qPCR.

All qPCR assays were performed with three biological replicates per condition. Total cellular RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen). Incubation with DNaseI (Invitrogen) was performed on isolated RNA following the manufacturer’s instructions to digest DNA contaminants. Reverse transcription was performed using the SuperScript IV First-Strand Synthesis kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Quantitative PCR was performed using the ViiA 7 real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems), SYBR green PCR master mix (Life Technologies), and gene-specific primers. The follow primers were used: ifn-β (F: 5’- AAACTCATGAGCAGTCTGCA - 3’; R: 5’- AGGAGATCTTCAGTTTCGGAGG −3’), cxcl10 (F: 5’-ACGCTGTACCTGCATCAGCA −3’; R: 5’- TTGATGGCCTTCGATTCTGG −3’), isg54 (F: 5’- ACGGTATGCTTGGAACGATTG −3’; R: 5’- AACCCAGAGTGTGGCTGATG −3’), il-12 (F: 5’- CTCCAGAAGGCCAGACAAACTC −3’; R: 5’- GCCAGGCAACTCCCATTAGTTA −3’), tnf (F: 5’- CTGGGCAGGTCTACTTTGGG −3’; R: 5’- CTGGAGGCCCCAGTTTGAAT −3’), and gapdh (F: 5’- TTCGACAGTCAGCCGCATCTTCTT −3’; R: 5’- CAGGCGCCCAATACGACCAAATC-3’). To quantify relative mRNA abundances of each gene, the ΔΔCt method was applied using gapdh as the internal reference. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 9 and significance was determined by Student’s t test (two-tailed): *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001.

Whole Proteome and PRM-MS Sample Preparation.

In biological triplicate for the whole proteome analysis and biological duplicate for the PRM analysis, cells were collected by scraping monolayers, washing in PBS, pelleting, and lysing by resuspension in 5% SDS and 50 mM triethylammonium bicarbonate (TEAB), pH 8.5. Protein concentration was determined by BCA assay (Pierce; 23225), and 20 μg protein per sample was reduced and alkylated, upon the addition of a final concentration of 25 mM tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP) and 50 mM chloroacetamide, and incubation at 70°C for 20 min. Samples were acidified with aqueous phosphoric acid to a final concentration of 2.5% and loaded onto S-Trap micro spin columns (Protifi; C02-micro) with binding/wash buffer (100 mM TEAB and 90% methanol, pH 7.55) for desalting, digestion, and peptide extraction following the manufacturer’s protocol. Samples were washed for a total of 10 rounds prior to trypsinization. Trypsin digestion was performed at a 1:25 ratio (enzyme:protein w/w ratio) and incubated overnight at 37°C. Peptides were eluted, dried down using a speed-vac, and resuspended in 1% formic acid and 1% acentonitrile to achieve a final concentration of 0.75 μg/μl, with 2 μl (1.5 μg) loaded on column for LC-MS/MS analysis.

Whole Proteome MS.

LC-MS/MS analysis.

Peptides were analyzed by LC-MS/MS on a Dionex Ultimate 3000 nanoRSLC coupled online to an EASYSpray ion source and a Q Exactive HF Hybrid Quadrupole-Orbitrap mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) using data-dependent acquisition (DDA) mode. Peptides (1.5 μg on column) were separated using an EASYSpray PepMap RSLC C18 column (75 μm x 50 cm) heated at 50°C via a 150 min linear gradient of 3 to 30% solvent B over 80 min, followed by an increase from 30 to 40% solvent B over 70 min at a 250 nL/min flow rate. MS1 scans were acquired at a 120,000 resolution, an AGC target of 3e6, a maximum inject time (MIT) of 30 ms, and a scan range of 350 to 1800 m/z recorded in profile. The top 20 precursors were selected for fragmentation and MS2 scans were acquired at 15,000 resolution, an AGC target of 1e5, an MIT of 25 ms, an isolation window of 1.2 m/z, a fixed first mass of 100.0 m/z, and a normalized collision energy of 28. Peptide match was set to preferred with a dynamic exclusion of 30 s.

DDA data analysis.

RAW files were analyzed through Proteome Discoverer v2.4 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) wherein spectra were searched against a Uniprot human database (downloaded January 2021) appended with common contaminants. Using the SEQUEST HT algorithm, the search parameters required tryptic peptides with a maximum of 2 missed cleavages, precursor mass tolerance of 4 ppm, and a fragment ion mass tolerance of 0.02 Da. Permitted peptide modifications included static carbamidomethylation on cysteine, dynamic oxidation of methionine, dynamic deamidation on asparagine, dynamic phosphorylation on serine, threonine, and tyrosine, as well as dynamic loss of methionine and acetylation on the N-termini of proteins. Matched spectra were scored by Percolator and PTMs were localized using ptmRS. Peptide and protein identifications were assembled from the resulting peptide spectrum matches with a false discovery rate of less than 0.01 at both the peptide and protein levels. Proteins with at least 2 unique peptides were quantified. Missing values were imputed through the low abundance resampling algorithm and proteins were normalized by the total peptide amount. Protein abundance was calculated by the summed abundances method and statistically different abundances were determined by a background-based t test implemented in Proteome Discoverer. Gene ontology analyses of differential proteins (adjusted p-value ≤ 0.05) were assessed through statistical overrepresentation analysis using the PANTHER classification system knowledgebase25, 26 and functional annotation using the DAVID bioinformatics database27, 28. HumanBase (Flatiron Institute – Simons Foundation)29 was used for monocyte-specific functional module detection. Unsupervised hierarchical clustering was performed using Morpheus (Broad Institute; https://software.broadinstitute.org/morpheus). Protein-protein interactions were generated in Cytoscape30 (version 3.10.1) using the StringApp Plugin with edges set to high confidence and all interaction features detected except for textmining31, 32.

PRM-MS.

Peptide library assembly.

Peptides were selected by prioritizing identification in the DDA MS analysis of the whole proteome (see above). DDA RAW files were analyzed by Proteome Discoverer v2.4 to generate a spectral library of identified peptides and loaded into the Skyline MS analysis platform33, 34 along with the RAW files. The selected IFN responsive proteins were additionally filtered for tryptic peptides between 7 and 28 amino acids in length, with carbamidomethyl cysteine modifications allowed to select against multiple ion charge states. Transition ion settings were set to include the +2 or +3 precursor charge states with b and y ions, library match tolerance of 0.5 m/z, instrument settings at 50–1500 m/z, method match tolerance of 0.055 m/z, full-scan settings at 30,000 resolving power and 200 m/z for MS/MS filtering. The retention time predictor calculator in Skyline was used to run and sequentially refine a series of scheduled runs with 6 min retention time windows. The final IFN responsive peptide library for PRM was defined to include ≥ 2 unique peptides per protein. Final peptide inclusion lists were extracted to include 7 min retention time windows for selected precursor ions set to a maximum of 16 concurrent precursors.

PRM LC-MS/MS analysis.

Samples were analyzed by LC-MS/MS using a Dionex Ultimate 3000 nanoRSLC coupled online to an EASYSpray ion source and a Q Exactive HF Hybrid Quadrupole-Orbitrap mass spectrometer. Peptides (1.5 μg on column) were separated using an EASYSpray PepMap RSLC C18 column (75 μm x 25 cm) heated at 50°C via a 60 min linear gradient of 2 to 22% solvent B over 45 min, followed by an increase to 38% solvent B over 15 min at a 250 nL/min flow rate. The PRM method included an MS1 scan followed by 30 PRM scans. For the full scan MS1, the instrument was set to a full scan range of 400 to 2000 m/z, 15,000 resolution, an AGC target setting of 3e6, and MIT of 15 ms. MS2 scans were set to be acquired at a resolution of 30,000, an AGC target setting of 1e5, MIT of 60 ms, an isolation window of 0.8 m/z, fixed first mass of 125.0 m/z, and a normalized collision energy of 27. Spectrum data (MS1 and PRM scans) were recorded in profile.

PRM data analysis.

RAW PRM files were imported into Skyline to both extract the product ion chromatograms and calculate peak areas. RAW files were also searched by Proteome Discoverer and search results were imported into Skyline as a spectral library. Spectra were searched against a Uniprot human database (downloaded January 2021) appended with common contaminants. The SEQUEST HT algorithm was used to search for tryptic peptides with ≤ 2 missed cleavages, a precursor mass tolerance of 10 ppm, and a fragment mass tolerance of 0.02 Da. Percolator was used to score the matched spectra. In Skyline, peptides were parsed to maintain the ≥ 3 highest intensity fragment ions in the IFN treated samples with the lowest mass errors. In each sample, peak areas for each peptide were summed and normalized by the total MS1 intensity of the sample. Peptide abundance comparisons were calculated as a ratio of an IFN-treated sample over control the treatment, and all peptides per protein were averaged per replicate, and then averaged across replicates. Individual values of each protein per sample were plotted in heatmaps and two-tailed Student’s t tests were performed to determine statistical significance in GraphPad Prism.

TPCA and MS.

Sample preparation.

6 × 106 THP-1 cells in biological duplicate were collected by trypsinization after 24 h treatment of each IFN stimulant condition. Samples for heat denaturation were prepared as previously described35. Cells were washed in PBS, pelleted, and resuspended in 500 μl PBS. 10% of the cell suspension (50 μl) was individually aliquoted into ten PCR tubes. Samples were subjected to heat denaturation with a thermal cycler, each placed at one temperature along a gradient ranging from 37°C to 64°C for 3 min then kept at 4°C for 3 min. Lysis buffer (100 μl; 75 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 15 mM MgCl2, 1.5× HALT protease and phosphatase inhibitor (Fisher Scientific; 78446), 3 mM TCEP) was added to each PCR tube and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen. Upon thawing at room temperature, samples were mechanically lysed by ten passes through a 21-gauge needle, followed by six passes through a 26-gauge needle. Lysates were freeze-thawed and centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 20 min at 40°C. Supernatants were reduced and alkylated with 25 mM TCEP and 25 mM chloroacetamide at 55°C for 30 min. Methanol-chloroform extraction was performed and precipitated protein was resuspended in 160 μl of 50 mM EPPS-KOH, pH 8.3. Samples were bath sonicated with 20 bursts of 1 s pulses and BCA was performed to determine protein concentrations. For each sample of IFN condition, the volume required to achieve a protein concentration of 0.5 mg/mL in the 37°C sample, and associated temperature samples were volume-matched. Trypsin digestion (Thermo Fisher Scientific; 90059) with 1 ug enzyme was performed at a 1:50 w/w enzyme:protein ratio overnight at 37°C. Digested peptides were adjusted to 100 mM EPPS, pH 8.3 and 20% of 100% anhydrous acetonitrile. Peptides were labeled using 11-plex isobaric labeling TMT reagents (Thermo Fisher Scientific; 90406 and A34807) for 1 h at room temperature with 1000 rpm shaking. TMT channels 126–131N were used to label the gradient of heat denatured samples in a non-randomized order, while the 11th 131C channel was used to label a reference channel, for cross TMT-plex referencing, containing an equal volume mixture of all 37°C-treated samples across all IFN treatment conditions. TMT labeling was quenched with the addition of a final concentration of 0.33% hydroxylamine (Sigma-Aldrich, 467804) and incubation for 10 min at room temperature. A test mixture was generated by combining 2 ul of each labeled channel per TMT-plex, acidifying to 1% trifluoroacetic acid, and desalting by C18 stagetip. Samples were resuspended in 5 ul of 1% formic acid and 1% acetonitrile, with 2 ul of test mixture analyzed by LC-MS/MS on a Q Exactive HF instrument. Derived ratios from the test mix were calculated by searching the RAW file in Proteome Discoverer v2.4. Sigmoidal curve fitting was performed to correct for lower protein solubility at the higher temperatures and technical variation between samples. From these ratios, a quantitative mixture was assembled by combining labeled samples of each channel in a TMT 11-plex. Quantitative mixtures were dried down in a speed-vac, resuspended in 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid, and separated into eight fractions using basic reverse phase fractionation following the manufacturer’s instructions (Thermo Fisher Scientific; 84868). Fractionated samples were dried down in a speed-vac and resuspended in 6 ul of 1% formic acid and 1% acetonitrile prior to LC-MS/MS analysis on a Q Exactive HF instrument.

TPCA LC-MS/MS analysis.

All samples were analyzed using a Dionex Ultimate 3000 nanoRSLC coupled online to an EASYSpray ion source and a Q Exactive HF Hybrid Quadrupole-Orbitrap mass spectrometer. Test mixtures were resolved using a linear gradient of 6 to 18% solvent B over 60 min, then 18 to 29% solvent B over 30 min at a 250 nL/min flow rate. Full scan MS1 was set at a resolution of 120,000, an AGC of 3e6, an MIT of 30 ms, and a scan range of 350 to 1800 m/z. MS2 scans were set to acquire the top 20 most intense precursor ions, a resolution of 45,000, an AGC of 1e5, an MIT of 72 ms, an isolation window of 1.2 m/z, a fixed first mass of 100.0 m/z, and a normalized collision energy of 34. Dynamic exclusion was set to 25 s. Quantitative mixtures were resolved similarly, with the following exceptions: the linear gradient of 6 – 18% solvent B was performed over 80 min, and an isolation window of 0.8 m/z.

TPCA data processing.

RAW files were analyzed through Proteome Discoverer v2.4, as described for the DDA whole proteome analysis with additional specifications as described. To partially account for the likelihood of isotopic carryover of the TMT labels from adjacent channels to bias the quantitative Tm measurements and predicted PPIs, reporter ion isotopic distributions were used as isotope correction factors in Proteome Discoverer (Table S1, Supporting Information). The spectral recalibration node was used for offline recalibration of mass accuracy. Database search parameters included fully tryptic peptides, ≤ 2 missed cleavages, and static carbamidomethylation of cysteine, TMT labeling of the N terminus and lysine (dynamic for the test mixture searches and static for the quantitative mixture searches). Further dynamic modifications included oxidation of methionine, deamination of asparagine, as well as methionine loss and acetylation of NH2-termini. Precursor mass tolerance was placed at 4 ppm and fragment mass tolerance was set to 0.02 Da. Percolator was used to calculate the false discovery rate (used at 1%). Under the reporter ion quantifier node, integration tolerance was set to 10 ppm and the integration method was placed as the most confident centroid. The co-isolation threshold was set to 30 and the average reporter signal:noise threshold was set to eight. Modified peptides containing deamidated asparagine or glutamine, phosphorylated serine, threonine, or tyrosine, or oxidized methionine were excluded from the quantification analysis.

TPCA data was further processed as previously reported36. First, the data were normalized within plex using median of median normalization. This was accomplished by calculating the median value of all proteins within a single 11-plex, then calculating the median value of all such generated median values. The values of all proteins across all plexes were divided by this final median value. The data were next normalized across plex by calculating the mean value of the reference channel for each individual protein across all plexes in which the given protein was detected, giving one mean value for each protein detected across all conditions and replicates. The values of all proteins were then divided by the given protein’s mean value which was calculated in the previous step. Finally, the data were fit to a three-parameter log-logistic equation:

| Eq. 1 |

Calculating Protein and .

Protein melting temperature () was determined by first scanning along a protein’s melting curve to identify a temperature at which the protein’s relative abundance was 0.5 ±0.05. For curves in which this criterion was not met but in which at least one value below 0.5 was observed, curve fitting was performed. First, the two-point transition from a value above 0.5 to a value below 0.5 was selected as the center (e.g., if the value at 55°C is 0.6 and the value at the following temperature, 58°C, is 0.45, then center is the between 55°C and 58°C). Two subsets (four-point curves) of the melting curve were then selected such that one curve was centered at one value below and the other one value above the center point determined in the previous step. A third-degree polynomial was fit to each of the curves and the determined parameters were used to generate higher resolution curves. These two higher resolution curves were averaged together, using their respective r2 values (calculated based on fit to their respective four-point curves). This averaged higher resolution curve was used to estimate the temperature at which the protein’s relative abundance was 0.5 ±0.05. In scenarios in which two offset curves could not be selected (i.e., centered at the very first or very last value of the curve) a single four-point curve was selected and the was otherwise determined in the same fashion. If the relative abundance of a protein was never observed reach 0.5 or below the protein was considered a nonmelter and assigned a of 100°C. Protein melting shifts (Tm) were calculated by subtracting the melting temperature observed in the experimental condition from that observed in the control condition.

Prediction of protein-protein interactions from TPCA data.

Protein-protein interactions (PPIs) were predicted from TPCA data using the ensemble machine learning framework Tapioca36, which automatically integrates TPCA data with sequence predicted protein physical properties, protein domain information, and tissue-specific functional networks (here a monocyte-specific functional network was used). Tapioca computes a 0 to 1 score for all possible protein pairs detected within the TPCA data. Tapioca predictions were evaluated using the gold standard as previously reported36, which uses filtered subset of CORUM complexes as positive examples and proteins pairs not known to localize to any of the same subcellular localizations as negative controls. Subcellular localizations were based on the Human Protein Atlas database37. The gold standard was used to calculate a false positivity rate (FPR) versus Tapioca score curve. Based on this curve, a Tapioca score cutoff of 0.5 (average of ~10% FPR across all conditions and replicates) was used to call PPIs.

CORUM complex analysis.

Detection of a CORUM complex was defined as detecting greater than 50% of the given complex’s subunits. CORUM complex scores were calculated by taking the average of Tapioca scores assigned to the complex’s detected subunit pairs. Complexes were considered assembled if they were assigned a score of 0.4 or higher.

TPCA quantification and statistical analyses.

TPCA data processing and analyses were performed using Python 3.10.8, using the Python libraries NumPy38, Scikit-learn, SciPy39, Pandas, Biopython40, Seaborn, and Matplotlib. See Data Availability for access information to the Tapioca code.

Data Availability.

Raw MS files generated in this study have been deposited to the public database ProteomeXchange Consortium repository via the PRIDE partner repository41. The accession number is PXD046976. PRM data has been deposited in Panorama Public42 and can be accessed at https://panoramaweb.org/mcuQny.url. The code for Tapioca can be accessed at https://github.com/FunctionLab/tapioca. Entire membrane images for immunoblot data are provided as supplementary data within the Supporting Information.

Results and Discussion

Type I and Type II IFNs drive differential inflammatory responses in macrophage-like monocytic cells

To understand the cell-wide responses to different IFN classes and subsequent impacts on virus restriction, we first sought to define the protein abundance signatures upon independent stimulation with IFNs (Fig. 1A). We selected the human monocytic leukemia cell line, THP-1, as it has long served as a tractable model system to investigate cytokine responses across a broad range of contexts, including during diverse virus infections43–50. To investigate macrophage-like responses to IFNs, we differentiated the THP-1 cells with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) for 48 h prior to IFN stimulation (Fig. S1A). We focused our analysis on type I IFN-β and type II IFN-γ stimulation in the differentiated THP-1 cells, as type III IFN-λs have been shown to be functional predominantly within cells comprising endothelial and epithelial barriers. Indeed, other cell types including THP-1 cells exhibit low levels or absent expression of the IFN-λ receptor, IFNLR151.

Upon determining PMA treatment conditions to differentiate the THP-1 cells, we selected 50 ng/mL for 48 h, as it induced protein expression of known ISGs and activators of ISG expression, including IFIT3, RIG-I, and IRF1 (Fig. 1B). IFIT3 levels were induced and stable between low (10 ng/ml) and high (100 ng/ml) levels of IFN-γ treatment, with the exception of a marked increase upon longer-term and high PMA pre-treatment and high IFN-γ stimulation (5 days of 50 ng/ml PMA) (Fig. 1C). These observations suggested that our selected PMA treatment condition was below a saturated cellular response level for expressing known ISGs. Total cell lysates were collected at 24 h post stimulation with either vehicle control, IFN-β, or IFN-γ and the resulting proteomes were compared by label-free MS quantification. Among the approximately 6,000 proteins identified, over 5,250 proteins were quantified across biological replicates. A subset of 435 proteins had significantly altered abundances (up- or down-regulated) upon either IFN treatment relative to the control (adjusted p-value ≤0.05 and log2 fold-change ≥1) (Fig. 1D-E, Table S2, Supporting Information).

Focusing on proteins upregulated by IFNs, gene ontology (GO) analysis of the 150 proteins increased by IFN-β and the 151 proteins increased by IFN-γ revealed similar enrichments in pathways relating to virus and protozoan defenses, innate immune response, and responses to either type I IFN or type II IFN, respectively. As expected, these observations support that the IFN responses were sustained at the 24 h time point. Seventy-two proteins were commonly increased upon each IFN treatment. Of these, proteins exhibiting relatively similar degrees of increase over the control condition included proteins involved in virus defense such as promyelocytic leukemia body constituents PML and SP110, the RNA helicase DDX60L, as well as E3-ubiquitin ligases DTX3L, TRIM22, and TRIM25. Consistent with equivalent activation of IFN signaling between the treatments, components immediately downstream of initial IFN signaling through ligand binding to cell surface IFNAR receptors were also similar, including STAT1, STAT2, IRF9, and NFKBIB. Notably, the transmembrane protein TMEM256 exhibited not only a similar increase between the two IFN treatments, but also the highest induction relative to the control (Fig. 1D-E). While roles for TMEM256 in immune responses and defense against pathogens do not appear to be reported, Influenza A virus infection has been shown to regulate its splicing, suggesting a possible role in the replication of this virus52. Additionally, similar increases were identified in proteins known to temper immune signaling, including IFI35, STAT2, UBE2L6, and CASP1. These observations likely represent the co-occurrence of compensatory homeostatic regulatory mechanisms upon initiation and maintenance of IFN stimulation.

In addition to the proteins that responded similarly to the two IFN treatments, several groups of proteins displayed an average preferential upregulation in response to one of the IFN classes (Fig. 1F, Table S2, Supporting Information). Upon IFN-β stimulation versus control, relative to IFN-γ versus control, proteins involved in ISGylation, including ISG15, HERC5, and USP18 were increased over eight-fold. Canonical ISGs belonging to the family of interferon inducible proteins with tetratricopeptide repeats, IFIT1 and IFIT3, exhibited approximately ten-fold and two-fold increases, respectively. The dynamin-like GTP-binding proteins MX1 and MX2 were nearly five-fold increased. Proteins involved in nucleic acid sensing during pathogen infections, including the oligoadenylate synthetase proteins OAS1, OAS2, OAS3, and OASL, were induced three-fold. Proteins that were enhanced during IFN-γ treatment, relative to IFN-β, were consistent with roles for IFN-γ in polarization of macrophages. Specifically, IFN-γ enriched for proteins that modulate immune cell activation, proliferation, and apoptotic pathways. This included the tryptophan-metabolizing enzyme IDO153 (87-fold increase), GTPases (GIMAP4, GIMAP5, and GIMAP8 at ~4-fold, 66-fold, and 2-fold increases, respectively), and programmed cell death ligand CD27454 (8-fold increase), as well as inflammatory M1 polarization markers such as the cytokine IL-1β (~6.5 fold increase), TNF receptor family protein CD4055 (2.5-fold increase), adhesion molecule ICAM-156 (~4-fold increase), major histocompatibility complex components HLA-DPA1, HLA-DRB1 (>20-fold increase), and CD7457, 58. We identified expected increases in anti-microbial GTPases, GBP1, GBP2, GBP4, GBP5, and GBP7 (~4-fold increase), which have been shown to facilitate pathogen clearance through disruption and pathogen-associated molecular pattern (PAMP) release of pathogen-contain vacuoles, followed by downstream caspase-mediated inflammasome formation and pyroptosis59. Altogether, our cell-wide proteome analysis revealed differential inflammatory responses in macrophage-like differentiated THP-1 cells upon stimulation with type I and II IFNs.

Comparison to pro-inflammatory LPS stimulation uncovers specific ISG protein profiles

To further consider our IFN-induced proteomic findings in differentiated THP-1 cells in relation to alternative IFN stimulatory agents, we performed a comparison upon treatment with the pro-inflammatory stimulant, LPS, for 24 h (Figs. 1A and 2A). LPS is well known to induce the expression of type I IFNs by macrophages and other immune cell types60–63. As such, we anticipated that LPS would phenocopy protein profiles upon IFN-β treatment. Indeed, we identified common relative enrichments between IFN-β and LPS treatments in proteins with gene ontology classes connected to IFN-β response, cytolysis, ISG15 conjugation, positive and negative regulation of type I IFN signaling, ribonuclease activity, and positive regulation of virus defense (Fig. 2A and Fig. S1B). We also identified ISGs commonly induced by all three treatments (IFN-β, IFN-γ, and LPS). Given prior proteomic evaluation of LPS treatment at 24 h in undifferentiated, monocyte-like THP-1 cells7, we incorporated this complementary dataset in our analysis (adjusted p-value ≤ 0.05 and log2 fold-change ≥ 0.6). This enabled us to obtain a subset of 47 proteins upregulated across the stimulants in both differentiated (IFN-β, IFN-γ, and LPS) and undifferentiated (LPS) cells (Fig. 2B and Fig. S1C). Unsupervised hierarchical clustering and association with the previously defined GO categories stratified proteins into groups with the highest enrichments either in response to IFN-γ (e.g., GBP1 and GBP2), to IFN-β and LPS (e.g., DDX58, IFIT1, IFIT3, MX1, MX2, OAS1, ISG15, SP110), to LPS (e.g., GBP4, IFIH1, HELZ2), or those with milder or equivalent enrichments across these treatments (e.g., IFI16, IFI35, PML, TAP2). We then performed a functional module analysis using a human monocyte-specific background (Fig. 2C). In agreement with the GO analyses under non-tissue specific conditions (Fig. 1B-D and Fig. 2A-B), the resulting functional networks were linked to the negative regulation of the viral life cycle (Module 1), response to exogenous double-stranded RNA (Module 2), chromatin binding and DNA break repair (Module 3), response to IFN-γ and TNF (Module 4), and defense against viruses (Modules 5 and 6). Notably, proteins in Modules 5 and 6 (e.g., OAS1, OAS2, MX1, MX2, ISG15) exhibited strong type I IFN-dependent abundance increases, relative to IFN-γ.

Fig 2. Comparison to pro-inflammatory LPS stimulation uncovers specific ISG protein profiles.

(A) GO overrepresentation analysis of proteins significantly increased upon either IFN-β or IFN-γ treatments over the control in differentiated THP-1 cells, with additional comparison to LPS treatment versus the control.

(B) Alluvial plot with GO categories in (A) and heatmap with hierarchical clustering of the common 47 significantly increased proteins identified across IFN-β, IFN-γ, and LPS treatments from this study, as well as LPS treatment in undifferentiated THP-1 cells from Mulvey, et al7.

(C) Functional module detection and clustering of the 47 proteins from (B) based on a tissue-specific monocyte background, as determined by HumanBase29. Edges represent functional association and size represents the relative number of identified functional relationships.

(D) Targeted MS analyses by parallel reaction monitoring for selected IFN responsive proteins from each functional module in (C), as well as stimulant-specific proteins and others with known roles in the described categories. A proteotypic peptide library of these ISG protein markers was developed to monitor relative protein abundances across cells treated with IFN-β, IFN-γ, or LPS.

(E) Immunoblot analyses of observed inflammatory protein signatures in the THP-1 cells treated across varying concentrations of IFN-λ and IFN-β as shown.

(F) Immunoblot analyses of observed inflammatory protein signatures in the THP-1 cells treated across varying concentrations of IFN-β and IFN-γ, including low (10 U/mL and 10 ng/mL, respectively) and high (100 U/mL and 100 ng/mL, respectively). IFN responsive protein signatures were comparatively assessed between IFN-β and IFN-γ treatments at early (3 h) and later (24 h) treatment times.

(G) Immunoblot analyses of observed inflammatory protein signatures in the THP-1 cells treated across varying concentrations of LPS (20 ng/mL, 200 ng/mL, and 2000 ng/mL).

To validate the relative protein alterations observed in the cell-wide proteome analyses, we developed a proteotypic peptide library for ISG protein markers and designed a targeted MS assay based on PRM for the simultaneous detection and quantification of proteins responsive to the IFN stimulants. We built our assay to detect ISG protein classes promiscuously responsive to all IFN stimulants. Included were proteins from each functional module identified above, stimulant-specific proteins, and proteins with ISG-relevant roles (antiviral and cytokine responses, PAMP sensing, signal transduction, protein modification, antigen presentation, and regulating IFN levels). We performed manual curation of proteotypic peptides unique to each protein, and sequentially optimized detection parameters for LC separation, MS detection, and MS/MS fragmentation (Fig. 2D and Table S3, Supporting Information). In agreement with our data-dependent whole proteome analysis, we observed increases in all relevant IFN-responsive conditions for 68 out of 69 proteins monitored. The increased precision of our ISG-PRM assay additionally uncovered upregulation of proteins that were not reproducibly identified or fell below the fold-change and statistical significance cut-offs of our whole proteome analysis (e.g., TRIM5, TRIM14, IFIT5, HLA-DRB5).

Having determined proteomic markers upon 24 h of stimulation in THP-1 cells, we next validated several of these IFN-dependent changes and further assessed their dynamics by immunoblotting. As expected, differentiated THP-1 cells were poorly responsive to Type III IFN-λ, which is known to induce a kinetically delayed ISG profile similar to Type I IFNs64. Specifically, IFN-λ did not induce IRF1, IFIT1, or MX1 protein levels even after 48 of treatment (Fig. 2E). However, in agreement with our proteomic data, IFIT1, MX1, and ISG15 increased upon IFN-β and IFN-γ treatments (Fig. 2E-G). Shorter IFN stimulation at 3 h indicated time-dependent increases in ISGs. Notably, free, unconjugated ISG15 is rapidly produced upon IFN-β treatment, and conjugated to proteins over longer periods of time. Finally, we confirmed signature increases in MX1 and IFIT1 upon LPS stimulation for 24 h (Fig. 2G). Collectively, these data identify and orthogonally validate protein signatures both unique to Type I and Type II IFN classes and promiscuous to IFN stimulants in an immune cell type.

Type I and Type II IFNs differentially stabilize ISG protein interactions in macrophage-like monocytic cells

As protein functions inherently rely on the strengths and stoichiometry of their protein-protein interactions, as well as their cellular abundances, the extent to which ISGs are expressed upon IFN stimulation provides an initial framework for understanding their functions in vivo. To extend our knowledge of IFN-responsive ISGs, we used the thermal proximity coaggregation method (TPCA-MS) to globally define ISG protein associations upon IFN stimulation (Fig. 3A). TPCA-MS makes use of the biophysical principle that interacting proteins stabilize one another, thus resulting in similar protein denaturation/aggregation and melting curve profiles (i.e., protein thermal stability) upon exposure of cells to a gradient of increasing temperatures65–68. Upon PMA differentiation and IFN stimulation in THP-1 cells, each sample was divided into fractions and incubated at one of ten temperatures along a 37°C to 64°C temperature gradient. This enabled generation of log-logistic protein denaturation curves. Soluble proteins were extracted and isobaric labeling was performed by tandem mass tagging (TMT). Over 5,500 proteins were detected throughout the samples, with ~4,000 proteins identified per condition at the level of ≥ 2 unique peptides per protein (Fig. 3B and Table S4, Supporting Information).

Fig 3. Type I and Type II IFNs differentially stabilize ISG protein interactions in macrophage-like monocytic cells.

(A) Thermal proximity coaggregation and MS (TPCA-MS) workflow using Tapioca for characterizing protein interactions at a global scale. Sample preparation, data processing, and bioinformatic analysis of differentiated THP-1 cells upon IFN treatments (Control, IFN-β, and IFN-γ).

(B) Total number of proteins detected in each condition upon TPCA-MS analysis.

(C-D) Melting temperature shifts upon IFN treatment, Control – IFN, relative to the protein abundance ratios (IFN vs. Control) for (C) IFN-β and (D) IFN-γ. Proteins highlighted in yellow (IFN-β) or green (IFN-γ) denote those that were significantly increased in abundance relative to the control from the DDA-MS experiment (adjusted p-value ≤0.05 and log2 fold-change ≥1).

(E) Comparison of melting temperature shifts between Control - IFN-β and Control - IFN-γ. Proteins highlighted in yellow (IFN-β), green (IFN-γ), or brown (both IFN-β and IFN-γ) denote those that were significantly increased in abundance relative to the control from the DDA-MS experiment (adjusted p-value ≤0.05 and log2 fold-change ≥1). C1 – C6 denote labels for independent clusters of proteins exhibiting similar melting temperature shifts ~ ≥ 17°C for at least one IFN condition.

(F) Functional module detection of clusters C1 – C6 using Humanbase29 with a tissue-specific background of monocytes. The most significant modules are described. Cluster 2 contained too few proteins for functional module detection.

(G) Smoothened protein solubility curves for IFN-responsive proteins with melting temperature shifts as determined in (C-E), including MX2, TYMP, and SP100. Curves are expressed across the temperature gradient (37°C to 64°C). Solid lines represent the mean relative protein abundance of the biological replicates at each temperature.

(H) Evaluation of the true negative rate by one minus the false positivity rate (1-FPR) across Tapioca scoring values.

(I) Total number of predicted protein interactions across Tapioca scoring values.

(J) CORUM complex analysis based on Tapioca scoring, being defined as greater than 50% of the subunits comprising a complex. Average Tapioca scores were used to determine CORUM complex scoring and complexes were considered assembled with a score of 0.4 or higher.

(K) Smoothened protein solubility curves for Tapioca-predicted interactions, including CORUM complex proteins, GBP1 and GBP2, TRIM25-RIG-I, IFP35-NMI, across the temperature gradient (37°C to 64°C). Solid lines represent the mean relative protein abundance of the biological replicates at each temperature.

Upon normalizing protein abundances across temperatures, the resulting protein solubility curves were fitted with a three-parameter log-logistic function. Both protein melting temperature () and shifts in upon comparison of the IFN to control conditions (Control – IFN) were calculated. We first compared IFN-induced protein alterations in thermal stability to their protein abundance changes (IFN vs. Control) (Fig. 3C-D). Most proteins with increased abundances upon IFN stimulation did not exhibit large shifts in melting temperatures. Among the few proteins that displayed shifts (~17–27°C) were GBP1, MX2, and FLYWCH2 upon IFN-β stimulation, as well as TYMP and GBP1 upon IFN-γ stimulation. The positive direction of values suggested decreased stability upon IFN treatment. Several explanations may account for this outcome, including IFN-dependent increases in associations with protein complexes, nucleic acids, and small molecules. These observations further suggest that only a few IFN-induced thermal stability alterations involve proteins with significant abundance increases. Our findings are consistent with a prior study of protein correlation profiling in IFN-treated HeLa cells14. It is possible that alternative mechanisms drive the altered protein thermal stability in IFN contexts, such as post-translation modifications and subcellular localization. In comparing IFN-specific melting temperature shifts, we clustered proteins exhibiting distinct characteristics, i.e., thermal shifts exclusive to IFN-β (Clusters 1 and 4) or IFN-γ (Clusters 3 and 6) treatment, and those jointly affected by Type I and Type II IFNs (Clusters 2 and 5) (Fig. 3E and Table S5, Supporting Information). Using a monocyte-specific background, the enriched GO terms within these clusters included RNA splicing (Cluster 1), proton transmembrane transport and protein destabilization (Cluster 3), response to bacterial lipoprotein (Cluster 4), collagen biosynthesis and proteolysis (Cluster 5), and amyloid-β clearance (Cluster 6) (Fig. 3F). Proteins in Clusters 1 and 4 were both associated with the regulation of mRNA splicing and immune responses to PAMPs. Included were spliceosomal ribonucleoproteins, SNRPD3 and SNRPE (Cluster 1), as well as the interferon-inducible transcriptional regulator, SP100 (Cluster 4). While functional modules could not be confidently detected for the proteins in Cluster 2, we identified several interferon inducible and antiviral proteins, including MAVS, MX2, GBP1, CASP6, and SHFL. Consistent with roles for IFN-γ in recruiting and activating immune cells, IFN-γ dependent thermal shifts were identified for proteins involved in regulating T cell activation (Cluster 3). For example, Cluster 3 contained the thymidine phosphorylase, TYMP, with reported functions in facilitating T cell exhaustion69.

In observing the altered protein solubility curves from interferon-induced proteins within these clusters, including MX2, TYMP, and SP100 (Fig. 3G), we wanted to further assess ISG protein-protein interaction dynamics from our TPCA data. To accomplish this, we adapted our recently developed machine-learning platform to predict de novo protein-protein interaction dynamics, Tapioca36. We used Tapioca to integrate our TPCA data with assessments of protein physical properties, protein domains, and tissue-specific functional networks. We previously demonstrated that these parameters improved predictions compared to methods based on Euclidean distance36. We determined the false positivity rate for protein-protein interactions, selecting a Tapioca score cut-off of 0.5 for calling pairwise interactions (Fig. 3H). This cut-off corresponded to fewer than ~ 1% of all possible protein interactions (Fig. 3I). To monitor known protein complexes, we used Tapioca scoring on CORUM database complexes (Comprehensive Resource of Mammalian Protein Complexes70), detecting 113 CORUM complexes in at least one condition (Fig. 3J and Table S6, Supporting Information). Of these, several were ISG-containing with immune-modulatory functions that (1) passed our significance threshold for all three treatment conditions, and (2) contained at least one protein that was significantly increased in abundance across IFN-β, IFN-γ, and LPS treatments (from Fig. 2A-C). These positive and negative IFN regulatory complexes included the ISG factor 3 (ISGF3) complex, NFκB1-STAT3, 26S proteasome, IFP35-NMI, IκB binding partners, DTX3L-PARP9-STAT1, and TRIM25-RIG-I (Fig. 3J). In agreement with Tapioca predictions, protein solubility curves for components of the TRIM25-RIG-I and IFI35-NMI complexes were closely aligned (Fig. 3K). In addition to CORUM complexes, we observed expected associations between ISGs with reported functional interactions, including GBP1 with GBP2, and IFIT1 with IFIT2 and IFIT3 upon IFN stimulation (Fig. 3K and S2A). In the context of sensing bacteria-derived LPS, GBP1 and GBP2 were reported to interact, with GBP1 capable of recruiting caspase-4 to engage in pyroptosis71, 72. Consistent with this, we observed that GBP1 and GBP2 were each other’s highest predicted interactor upon either IFN treatment (Fig. 3K and Table S7, Supporting Information). Tapioca predicted additional GBP1 associations with proteins that align with its known biology, including CASP4 and GBP4 (Fig. S2B). While several ISGs exhibited altered solubilities upon IFN treatment, others were predicted to form interactions basally in control-treated THP-1 cells. In these cases, IFN treatment resulted in similar or higher interaction scores. We observed this for many of the 47 proteins that were upregulated across stimulants in THP-1 cells (IFN-β, IFN-γ, and LPS) (Fig. 3J and Table S7, Supporting Information). One possibility for this observation is that the basal expression levels of ISGs in immune THP-1 cells are sufficient to induce the interactions. IFN treatment may serve to increase the stoichiometry (in cases of oligomeric complexes such as TRIM proteins) and the penetrance of these ISG associations. Altogether, TPCA analysis of ISG protein interactions uncovered the formation and stabilization of ISG protein complexes that are known to modulate core cellular immune responses in both somatic and immune cell types.

Integration of immune cell & keratinocyte IFN responses with complementary ISG datasets

Comparative analyses of IFN-dependent proteomic signatures and relative abilities to inhibit virus infections offer insight into how specific ISGs contribute to host antiviral responses. Within a microenvironment of a virus infection, investigating these features between cell types that comprise sites of first-line encounters with viruses and immune cells helps to clarify outcomes of virus spread across a tissue and accompanying host responses. As such, common or unique host defense factors that drive variations in host susceptibility, viral replication, and virus spread can be more clearly discerned. Towards this end, having established IFN stimulatory responses in differentiated THP-1 cells, we next compared relative ISG abundance changes in primary gingival keratinocytes (pGK) of the oral mucosa (Fig. 4A). We selected pGKs for this comparative analysis given (1) their relevance as a frequent first-encounter barrier to pathogen infections; (2) their vulnerability to immune-modulatory virus infections and infection-induced illnesses; (3) their susceptibility to engaging in dysregulated immune states including ulcers; and (4) the lack of fundamental understanding of immune responsiveness and antiviral immunity of cells in the oral mucosal barrier73–78. To capture possible differences in the maintenance of ISG protein expression, we performed IFN-β and IFN-γ treatments for 24 h and 48 h and analyzed the proteome responses (Fig. S3A and Table S2, Supporting Information). Principal components analysis and Pearson’s correlation assessment indicated that the proteomes were primarily stratified by cell type (Fig. 4B and Fig. S3B). Considering cell type differences across all conditions (control, IFN-β and IFN-γ), in pGK cells, we detected enrichments in proteins with developmental and cytoskeletal roles (e.g., integrins ITGA2, ITGA3, and ITGB4, laminin subunits LAMA3 and LAMB3, EGFR, CDCP1, and annexins ANXA1, ANXA2, ANXA3) (Fig. S3C). As anticipated, proteins mediating keratinocyte differentiation (e.g., CSTA, EVPL, IVL and TGM1) were also increased. In THP-1 cells, we detected protein enrichments in lymphocyte activation and T cell activation in immune response (e.g., CORO1A, ITGAL, LCP1, LGALS9, SPN), amine catabolism (e.g., HNMT and KYNU), as well as metabolism relating to the electron transport chain and ATP (e.g., COA6, PARP1, NDUFA4).

Fig 4. Comparative proteomic analysis of immune cell & keratinocyte IFN responses with complementary ISG datasets.

(A) Workflow for comparing the whole cell proteomic responses of monocyte-derived THP-1 cells and primary gingival keratinocytes upon stimulation with type I IFN-β and type II IFN-γ.

(B) Principal components analysis of THP-1 (24 h treatment) and pGK (24 h and 48 h treatments) samples.

(C) Comparison of relative protein abundances across IFN treatment conditions for ISG protein classes previously found to be either (1) upregulated upon pro-inflammatory LPS treatment in undifferentiated THP-1 cells (Mulvey, et al.7), or (2) evolutionarily conserved across species (Shaw, et al.79) and those found to be common in type I IFN-stimulated immune cells (Aso, et al.80). Protein abundances were normalized to the sum of each protein. Statistical analysis was performed using the Krustal-Wallis multiple comparisons test (****p-value ≤ 0.0001).

(D) Overlap occurrence of significantly increased proteins from the whole proteome of this study, relative to other ISG datasets. Statistical analysis was performed for each condition relative to the proteome of this study, using the Krustal-Wallis multiple comparisons test (****p-value ≤ 0.0001).

(E) Scatter plots and venn diagrams of significantly different proteins compared between THP-1 and pGK cells upon 24 h IFN stimulation (adjusted p-value ≤0.05 and log2 fold-change ≥1).

(F) Heatmaps of the relative abundances of significantly increased proteins identified in (E) with hierarchical clustering.

(G) Protein-protein interaction network of proteins identified in (E-F). Protein nodes depict the relative abundances between IFN-β and IFN-γ treatments as a ratio of their fold-change increases over the control. These ratio of ratios are shown in comparison to each other in the THP-1 and pGK cells. Edges represent STRING database-informed functional protein interactions.

Beyond proteins underlying fundamental cell type differences, we sought to place our findings in the context of previously reported ISG classes. We compared our proteomes to several related and complementary datasets, including (1) the proteomic characterization of LPS-treated THP-1 cells7; (2) a study that defined evolutionarily conserved ISGs across ten animal species79; and (3) an investigation into ISGs induced following a type I IFN stimulus across CD4+ immune cells targeted by HIV-1 infection (T cells, monocytes, and monocyte-derived macrophages)80. Upon exploring the intersection of these ISG-related datasets, we identified enrichments of our IFN stimulant-induced proteins with each immune-related dataset (Fig. 4C-D and Table S8, Supporting Information). Specifically, we observed a significant overlap between proteins up-regulated upon both types of IFN stimulation in our THP-1 and pGK cells and the ISGs in the three above-mentioned complementary datasets. Notably, up-regulated proteins in pGK cells were ~10–20% more enriched than those in THP-1 cells for evolutionarily conserved ISGs and “common” ISGs found in immune cells (Fig. 4D). Among these were antiviral proteins (RNA helicase protein DDX60, and tripartite motif-containing proteins TRIM26 and TRIM14), proteins known to modulate NF-KB activity and inflammation (E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase proteins RNF31 and RNF114), T-cell activation (RNF114), and protein ubiquitination or degradation (proteasome subunit protein PSMB8, ubiquitin hydrolase USP25, and lysosomal membrane glycoprotein LAMP3). Given that many of these proteins have reported roles in negatively regulating Type I IFN signaling81–84, their lack of induction in treated differentiated THP-1 cells may reflect a cell state of sustained positive IFN-β signaling.

We further identified proteins jointly up-regulated upon 24 h of IFN stimulation between THP-1 and pGK cells (adjusted p-value ≤0.05 and log2 fold-change ≥1) (Fig. 4E-G). Extended treatment time to 48 h in pGK cells primarily maintained the observed increases, with the exceptions of the beta-enolase ENO3, transcriptional regulator TXNIP, and glycosyltransferase domain-containing protein GLT8D1. IFN-β and IFN-γ treatments jointly increased 49 and 42 proteins over the control, of which conserved and immune cell “common” ISG proteins comprised 82% and 45%, respectively. Among these proteins, many exhibited similar relative degrees of upregulation between the two cell types, including the conserved and immune cell “common” ISGs, DDX58, CMPK2, STAT1, MX1, PML, and ISG15 in response to IFN-β, as well as SP110, STAT2, DTX3L, TRAFD1, GBP1, and SAMD9L in response to IFN-γ (Fig. 4E-G). Of those conserved and immune cell “common” proteins with degrees of upregulation differing by ~1.5× or more, THP-1 cells expressed higher levels of two out of three members of the canonical ISG factor 3 (ISGF3) complex that activates ISG transcription (IRF9 and STAT2), proteins involved in ISGylation control (USP18 and HERC5), as well as the transcription regulator TRIM22, RNA binding protein EIF2AK2, PML body constituent SP110, and GTP binding protein GTPBP2. Proteins expressed more strongly in pGK cells included IFIT proteins (IFIT1, IFIT2, and IFIT3) and innate immune regulators (IFI44, IFI44L, and BST2). Upon IFN-γ stimulation, far fewer conserved and immune cell “common” ISGs were increased in THP-1 relative to pGK cells, and these included STAT1, CD274, and TRIM22. IFN-γ-treated pGK cells had higher levels of the ISGylation factors ISG15 and UBE2L6, RNA binding proteins OAS2 and IFIH1, IFIT3, RNF213, and LAP3. Distinct from joint upregulations, the majority of differentially expressed proteins upon either IFN stimulation appeared unique to either THP-1 or pGK cells (Fig. 4E and S3D). In each of these comparisons, a subset of the proteins were ISGs that fell below our fold-change cut-off and significance threshold for the alternative cell line. Outside of this context, other proteins likely represent cell type-specific responses, such as the immune-associated GTPases GIMAP4 and GIMAP5 in IFN-γ-induced THP-1 cells, as well as the caspase inhibitory CARD16 in IFN-β-induced THP-1 cells. Altogether, we uncovered a series of IFN-induced proteins with differential relative abundances across cell types that play distinct roles in pathogen defense.

Relative antiviral protection conferred by cell type-specific IFN-induced ISG profiles

IFN binding to cognate receptors at the cell surface initiates the expression of a suite of pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory chemokines and cytokines. These small molecules not only promote inflammation during a pathogen infection, but also recruit immune cells to the site of infection. To understand the extent to which these molecules are expressed in THP-1 and pGK cells, we performed quantitative RT-PCR upon treating cells with IFN stimulants for 6 h (Fig. 5A). We chose a treatment time of 6 h to capture the early phase of the cellular response to IFN, as well as to represent a duration after which we and others have described relatively high cytokine production levels during virus infection85, 86. We performed LPS treatment in the differentiated THP-1 cells as a positive control for each cytokine assessed. As expected, LPS treatment strongly induced expression of pro-inflammatory ifn-β and tnf, whereas either IFN had no or minimal effect in each cell type. With the exception of isg54 levels, we observed equivalent or lower cytokine induction levels in IFN-stimulated pGK cells relative to THP-1 cells. In pGK cells, IFN treatments induced over 600-fold of cxcl10, which was nearly six-fold higher upon IFN-β treatment and doubled upon IFN-γ treatment in THP-1 cells. Levels of il-12 were minimally induced in pGK cells, yet increased approximately 30-fold in THP-1 cells. These observations support the heightened capacity of immune cells to initially respond to inflammatory signals, as well as promote the recruitment and activation of other immune cells.

Fig 5. Cell type-specific ISG abundances upon IFN stimulation confer relative antiviral protection.

(A) Relative levels of cytokines by qPCR analysis across IFN-stimulated THP-1 and pGK cells at 6 h post-treatment.

(B) Levels of virus progeny production in both IFN-stimulated THP-1 and pGK cells upon infections with either HSV-1, adenovirus, or HCMV. Statistical significance was determined by Student’s t test (two-tailed): *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001.

Having established the proteomic and cytokine expression signatures of Type I and Type II IFN stimulation, we sought to define the relative impact of these components on restricting virus progeny production in both cell types. We selected to infect cells with the α-herpesvirus, HSV-1, the tumor virus, AdV, and the β-herpesvirus, HCMV, as these viruses exist ubiquitously throughout the human population and have been shown to induce different levels of cytokines during infection86–89. Given differences in cell type characteristics (e.g., Fig. S3C) that can impact viral susceptibility and permissiveness, our focus was to compare the relative degree of virus restriction upon IFN treatments within each cell type. In assessing the number of infectious viral particles produced during HSV-1 infection for 24 h at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10, we observed differences in the relative capacities of each cell type to restrict the infection. In control treatments, THP-1 cells produced less infectious virus particles than pGK cells, implying less efficient virus replication (Fig. 5B). This was consistent with prior observations of HSV-1 infection in THP-1 cells and epithelial Vero cells90. Overall, we observed that IFN treatments reduced HSV-1 progeny production, in agreement with previous studies of HSV-1 infection in THP-1 cells91, 92. These findings were in line with knowledge that macrophages are a main source of Type I IFN during infections, contributing to host antiviral restriction, including during HSV-1 infection93–95. Relative to the controls, pre-treatment with IFN-β reduced HSV-1 titers by 83-fold in THP-1 cells and 4-fold in pGK cells. Pre-treatment with IFN-γ reduced HSV-1 titers by 42-fold and 4-fold, respectively. One possibility is that the proteins differentially expressed between IFN-β and IFN-γ treatments in pGK cells do not provide an added antiviral benefit in further inhibiting the production of infectious viral particles at this MOI and time point. While the lack of induction of certain antiviral ISGs in an IFN treatment (e.g., IFN-γ-induced GBP2 and GBP5) could be indirectly functionally compensated for by the induction of other IFN-specific antiviral ISGs (IFN-β-induced IFI27, IFI44, and IFI44L), the collective profile differences in sum do not appear to impact virus production. Furthermore, proteins jointly increased to similar extents by IFN (e.g., IFN-β-induced MX1 and IFN-γ-induced ISG15), or to a greater extent in pGK cells (e.g., IFN-β-/IFN-γ-induced MX2, IFIT2, IFIT3), may not account for the stark HSV-1 titer differences between the two cell types. This possibility would be intriguing given that MX2 has been shown to promote capsid disassembly and genome release during HSV-1 infection in THP-1 cells92. To account for the positive THP-1 differences between IFN treatments, as well as the lack of change in pGK, it is possible that select ISGs more strongly induced in THP-1s could be primary antiviral contributors. Indeed, some evolutionarily conserved or immune cell “common” ISGs that exhibit this trend include GTPBP2, TRIM22, HERC5, SP110, and IRF9.

During AdV infection for 72 h at an MOI of 20, the relative degrees of virus restriction upon IFN pre-treatments between the cell lines were more similar. IFN-β reduced AdV titers 17-fold and 6-fold in THP-1 and pGK cells, respectively. IFN-γ reduced AdV titers 83-fold and 70-fold, respectively. These observations point to the possibility that jointly increased proteins upon IFN-γ stimulation may contribute to similar virus restriction levels (e.g., HLA-DRB1, HLA-DPA1, and GBP5, among many others). In contrast to infections with HSV-1 and AdV, upon HCMV infection for 120 h at an MOI of 3, we observed little to no restriction, with the exception of a 4-fold reduction in HCMV titers upon IFN-β treatment of THP-1 cells. HCMV can induce several thousand-fold levels of cytokines in human cells upon infection at similar MOIs86. Thus, it is possible that the induced cytokines and ISGs conferred by IFN treatment do not provide further antiviral capacities. Additionally given the long lifecycle of HCMV, transient IFN stimulation for 24 h may be insufficient. Collectively, our findings describe how IFN classes induce distinct ISG abundance and interaction profiles that differentially contribute to antiviral resistance across different cells of the innate and adaptive immune systems.

Conclusions

We have described the contributions of Type I and Type II IFNs in orchestrating antiviral restriction of virus production within cell types that differentially contribute to the mammalian immune system. Our comparative analysis of macrophage-like monocytic THP-1 cells and primary gingival keratinocytes revealed that ISGs exhibit cell type-specific expression patterns endogenously, including basal and IFN-induced levels. These differences may be important contributors to the distinct degrees of virus suppression observed. A reasonable counter consideration is that the degree of ISG induction does not always correlate with the extent of antiviral capacity. This possibility has been reported for strongly induced IFIT proteins having little to no effect during several virus infections96–99. Between THP-1 and pGK cells during HSV-1 infection, this could explain the shared increases in IFIT1, IFIT2, IFIT3, MX1, and MX2, yet relatively minimal HSV-1 restriction effects in pGK cells. However, virus-specific mechanisms may be inhibiting certain ISGs, and ISGs may have virus-specific antiviral capacities. These are likely major contributing factors to the observed differences between viruses. Indeed, while IFIT proteins can suppress translation initiation, they have also been shown, particularly for IFIT1 to preferentially recognize viral 5’-triphosphate RNA motifs100, 101. From the perspective of virus-directed inhibition, the HSV-1 endoribonuclease UL41 has been shown to reduce IFIT3 mRNA levels102. It has also been reported that HSV-1 induces the expression of host microRNA miR-24–3p, which dampens IRF3-dependent induction of IFIT1 and IFIT2 mRNA. While these mechanisms of IFIT protein inhibition during HSV-1 infection have thus far identified manipulation of mRNA expression, these studies nevertheless support the existence of evolved immune evasion strategies. AdV infection is also well characterized in blocking IFN signaling pathways, particularly through the immediate-early and early expression of E1A, E1B, and E4 proteins103. It is further worth noting that we examined antiviral effects during contexts of ~ single cycles of infection. Additional investigation into virus spread during multi-cycle infections at lower MOIs will alter the relative impacts of IFN on virus restriction.