Abstract

This study aimed to optimize subcritical water extraction process, characterize chemical composition and investigate the biological activities of Nitraria sibirica Pall. (NSP) anthocyanin. Overall, the optimization was achieved under following conditions: extraction temperature 140 °C, extraction time 45 min and flow rate 7 mL/min with the extraction yield of 1.075 mg/g. 3 cyanidin, 3 petunidin, 1 delphinidin and 1 pelargonidin compounds were identified in the anthocyanic extract from NSP via UPLC–Triple–TOF–MS/MS. NSP anthocyanin exhibited better DPPH free-radical scavenging activity than ascorbic acid. It displayed superior α-glucosidase inhibition activity, which was ∼14 times higher than that of acarbose. Moreover, enzyme kinetics results indicated that NSP anthocyanin behaved as a reversible, mixed-type inhibitor. Molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulation results revealed that NSP anthocyanin interacted with α-glucosidase mainly via van der Waals forces, hydrogen bond and possessed fairly stable configuration. Therefore, NSP anthocyanin is a promising α-glucosidase inhibitor for diabetes mellitus.

Keywords: Nitraria sibirica Pall., Anthocyanin, Subcritical water extraction, UPLC–triple–TOF–MS/MS, Antioxidant, α-Glucosidase inhibition activity

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

The subcritical water extracted technology of NSP anthocyanin was optimized by RSM.

-

•

3 cyanidin, 3 petunidin, 1 delphinidin and 1 pelargonidin anthocyanins were identified.

-

•

Anthocyanic extract exhibited more excellent α-glucosidase inhibition than acarbose as a reversible, mixed-type inhibitor.

-

•

NSP anthocyanin interacted with enzyme mainly via van der Waals and hydrogen bond and possessed fairly stable configuration.

1. Introduction

Nitraria sibirica Pall. (NSP), belonging to the Nitraria genus of the Nitrariaceae family, is widely distributed in the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. As an ecological and economic forest tree, it has prominent characteristics in drought prevention, salt and alkali resistance and plays a critical role in ecological protection in the northwest of China (Qiu et al., 2023; P. Zhang et al., 2023; Zhu et al., 2021). The berries of NSP are used as food by the local Tibetan and Mongolian people because of their various nutrients. In addition, NSP berries are used for the production of fruit juice, wine, tea, fruit powder and seed oil in the food industry. Researches on the chemical components of NSP berries have shown that abundant bioactive substances exist in these berries, such as organic acids, alkaloids and phenolic compounds (Gravel & Poupon, 2010; Jiang et al., 2021; Song, Xia, Ji, Chen, & Lu, 2019; Zhao, Ding, Sun, Turghun, & Han, 2023; Zheng et al., 2011). As one of the chemical compounds in fruits, anthocyanin displays potential applications in cosmetic, pharmaceutical and food industries, becoming more popular among consumers. (Camara et al., 2022; Panchal, John, Mathai, & Brown, 2022). Modern pharmacological research has shown that anthocyanin obtained from Nitraria exhibits multiple pharmacological functions such as antioxidant, hypolipidemic, neuroprotective and cardioprotective activities. (Chen et al., 2021; Hu, Zheng, Li, & Suo, 2014; Ma et al., 2016; M. Zhang et al., 2017).

Conventional methods for anthocyanic extraction are Soxhlet, heat reflux and microwave- and ultrasound-assisted extractions, which require organic solvents to obtain high extraction yield (Cai et al., 2016; Hong, Netzel, & O'Hare, 2020; Kumari, Umakanth, Narsaiah, & Uma, 2021; Nunes Mattos et al., 2022). However, consumers are beginning to pay increasing attention to food safety in the modern society. Moreover, green and healthy production processes are currently required for food development. Therefore, a green, sustainable and economically feasible extraction technology is crucial. Subcritical water extraction (SWE) is a green solvent–extraction technique, which uses pressurized low-polar water between its boiling (100 °C) and critical (374 °C) points to maintain the liquid form of water. Because of its high dielectric constant, water is not an ideal extraction solvent for phenolic compounds at normal atmospheric temperature. However, temperature variations could change the dielectric constant of water, altering the corresponding polarity and selectivity (Kang, Ko, & Chung, 2021). The application of converted subcritical water makes it easy to extract less polar compounds (Xu et al., 2021). As a positive alternative of traditional extraction techniques, the SWE technology exhibits several advantages of being green, non-toxic, safe and cost effective and is widely used for the extraction of various active ingredients, such as essential oils, pectin and phenolic compounds (Basak & Annapure, 2022; Falletti et al., 2023; Liu et al., 2023; Mikucka, Zielinska, Bulkowska, & Witonska, 2022; Wang, Ye, Wang, Yin, & Liang, 2021). Optimization of the extraction process is crucial for obtaining good extraction yield of active ingredients. From the perspective of economy and production, response surface methodology (RSM) is considered as a suitable method for process optimization and is commonly used in the optimization of the extraction process (Ordóñez-Santos, Esparza-Estrada, & Vanegas-Mahecha, 2021; Ursu et al., 2023). Till now, no reports have been published on the application of SWE for extracting anthocyanin compounds from NSP fruit. Therefore, this study can provide an effective and green approach for NSP anthocyanic extraction, development and utilization in the food industry.

In this study, the SWE extraction process, compound analysis and biological activity of NSP anthocyanin were investigated. It is hypothesized that the SWE extraction technology is suitable for extracting NSP anthocyanin and the obtained extract may display excellent biological activities. The objectives of this study were to (1) optimize the SWE technology for NSP anthocyanic extraction, (2) characterize the chemical components of the anthocyanic extract and (3) investigate the antioxidant and hypoglycemic activities of the components and clarify the mechanism involved in their hypoglycemic functions.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Plant and reagents

Fresh fruits of NSP were collected in October 2021 from the Nuomuhong farm located in Haixi Mongol and Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, Qinghai Province (latitude: 36°27′N, longitude: 96°27′E, and altitude: 2857 m) and identified by Professor Qingbo Gao (Northwest Institute of Plateau Biology, Chinese Academy of Science). The voucher specimen (Nwipb 0334879) was conserved in the Qinghai Tibet Plateau Biological Herbarium, Northwest Institute of Plateau Biology. The kits of 2,2′- azinobis (3-ethyl-benzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) diammonium salt (ABTS, S0121) was purchased from Beyotime Biotechnology (Shanghai, China). 1,1-Diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA.). 4-Nitrophenyl glucopyranoside (pNPG) with a purity >98% and α-glucosidase (originated from yeast) were purchased from Aladdin Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Acarbose was supplied by Shanghai Yuanye Bio-Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). The anthocyanin standard of cyanidin-3-O-(trans-p-coumaroyl)-diglucoside (C3G) was prepared in our laboratory as previously published (Hu et al., 2014). HPLC-grade water was purchased from Wahaha (Hangzhou, China). HPLC grade acetonitrile and methanol were obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA). All other reagents used were of analytical grade unless otherwise stated.

2.2. SWE design by RSM

A type of RSM combined with the Box-Behnken Design (BBD) was performed to assess the influence of independent factors on anthocyanic extract (AEs) yield. The experiment involved three factors: X1, extraction temperature 120–140 °C; X2, extraction time 30–60 min and X3, flow rate 6–8 mL/min at three levels coded +1 (high value), 0 (medium value) and − 1 (low value). A total of 17 runs (5 replications for the center point included) were conducted to obtain the optimal conditions via SWE. The AEs yield (Y) was considered as the response variable of the experimental design. The levels of each independent variable and the 17 corresponding experimental designs are displayed in Table S1 and 1. To reduce the system errors, each experiment was performed in triplicate. Results of experiment were fitted to the quadratic polynomial model and the responses were predicted based on the following equation: Eq. (1).

| (1) |

where Y is the response variable (AEs yield, mg/g), Xi and Xj represent the levels of the independent variables. The constant, regression coefficients of linear, interaction and quadratic coefficient terms are expressed as β0, βi, βij and βii, respectively.

The significant difference under various conditions was analyze by the analysis using variance (ANOVA). The Fisher (F) value at a probability (P) of 0.05 was applied to evaluate the significant levels of quadratic interactions and linearity of different variables. The data of the lack-of-fit test were employed to determine the adequacy of the established model.

2.3. Conventional extraction of NSP anthocyanin

First, 1.00 g of fresh NSP fruit was weighed accurately and placed into a conical flask with a stopper. Then, 15 mL of ultrapure water (70 °C) was added into the bottle. Hot water extraction was conducted by ultrasonic treatment under the following conditions: ultrasonic time 45 min, extraction temperature 70 °C, ultrasonic power 150 W and ultrasonic frequency 20 kHz. Methanol extraction was performed according to the above ultrasonic condition but the solvent was replaced by 50% methanol solution (methanol: water, v: v). Finally, the anthocyanic extract was concentrated and dried using a vacuum freeze-dryer at −40 °C and vacuum of 10 Pa.

2.4. Determination of total anthocyanin contents for NSP anthocyanin

The total anthocyanin content for NSP was measured according to the pH-differential method with little modifications (Wrolstad, 2001). The absorbance of NSP anthocyanin was determined at 520 nm and 700 nm with pH 1.0 and pH 4.5, respectively. The anthocyanin content was calculated using Eq. (2) in terms of cyanidin-3,5-diglucoside equivalent with molar extinction coefficient of 30,175 and the molecular weight of 611.5 g/mol.

| (2) |

where A = (A520-A700) pH 1.0- (A520-A700) pH 4.5, MW represents the molecular weight of cyanidin-3,5-diglucoside. DF is the dilution factor and DV stands for the total volume (mL). ε represents the extinction coefficient for the standard of cyanidin-3,5-diglucoside. W is the sample weight and L represents path length (1 cm). 103 is the converted coefficient from g to mg.

2.5. UPLC-triple-TOF-MS/MS and HPLC conditions

To identify the chemical compound of NSP anthocyanic extract, the UPLC–Triple–TOF–MS/MS analysis was performed. First, 20.0 mg of the extracted sample was weighed accurately and 10 mL of 80% methanol was added and fully mixed using the vortex mixer. The solution was sonicated to dissolve anthocyanins and further centrifuged to obtain supernatant. The sample was filtered through a 0.22 μm filter before analysis. The analysis was conducted on an UPLC–Triple–TOF–MS/MS system equipped with AcquityTM ultra UPLC (Waters, American) and Triple TOF 5600+ mass spectrometer (AB SCIEX, American)with electric spray ion source. The separation process was conducted on an ACQUITY UPLC HSS T3 column (2.1 mm × 150 mm, 1.8 μm; Waters Corp). The chromatographic conditions for anthocyanin separation were as follows: column temperature 50 °C, wavelength 520 nm, injection volume 1 μL and flow rate 0.3 mL/min. The mobile phases composed of 0.1% formic acid acetonitrile (A) and 0.1% formic acid water (B). The chromatographic elution program was as follows: 5%–10% A (0–5 min), 10%–30% A (5–25 min), 30%–95% A (25–30 min). The conditions of mass spectrometry were installed under the following conditions: the pressure values for curtain gas (CUR), gasl (GS1) and gas2 (GS2) were 35, 55 and 55 psi, respectively. The scanning range was 100–1500 m/z. The temperature of the ion source (TEM) was fixed at 550 °C (negative) or 600 °C (positive). The ion source voltage was commanded at −4500 V (negative) or 5500 V (positive). For the first order scanning, the focusing voltage (CE) and declustering potential were separately regulated at 10 V and 100 V, respectively. The MS data were gathered in TOF MS ∼ Product Ion∼IDA mode. For the second order scanning, the CID energy value was set at −60, −40 and − 20 V, respectively. To lower the error value <2 ppm, a CDS pump was applied for mass axis correction before injection.

The semi-quantification analysis of NSP anthocyanin was conducted based on cyanidin-3-O-(trans-p-coumaroyl)-diglucoside (C3G) as a reference standard under different concentrations by HPLC. The chromatographic separations conditions were set as below: analytical column kromasil 100–5-C18 (4.6 mm × 250 mm, 5 μm; Acchorm), detection wavelength 520 nm, column temperature 30 °C, velocity of flow 1 mL/min and injection volume 10 μL. The elution phases were composed of acetonitrile (A) and 0.1% formic acid water (B). The gradient elution program was as below: 0–30 min, 10%–25% A. The HPLC analysis results were expressed as the average mg per g of dry anthocyanic extract in triplicate.

2.6. Evaluation of antioxidant activity

2.6.1. DPPH free-radical scavenging activity assay

DPPH is an extremely free radical, that is commonly employed as an assay to estimate the antioxidant activity of active ingredients. The determination of DPPH free-radical scavenging capacity was performed based on previous reports (Huo et al., 2023). Briefly, 2 mL newly prepared DPPH ethanol solution (0.08 mg/mL) was mixed with 1 mL of anthocyanin solution (0.8, 1.2, 1.6, 2.0, 2.8 and 3.6 μg/mL) and the mixed system was left to react for 30 min in a dark environment at room temperature. The absorbance value was recorded at 517 nm. Ascorbic acid was applied as the positive control. The DPPH free-radical scavenging capability was computed using the following equation.

| (3) |

where A0, A1 and A2 are the absorbance values of the anthocyanin solution, the mixture of the anthocyanin solution and anhydrous ethanol, and the mixture of DPPH and deionized water, respectively.

2.6.2. ABTS free-radical scavenging activity assay

The ABTS free-radical scavenging capacity of anthocyanin was determined following the manufacturer's instructions of ABTS kits. Briefly, the solution of H2O2 and peroxidase was separately diluted for 1000 and 10 times, respectively, and 20 μL peroxidase solution was added into a 96-well plate. Next, 10 μL phosphate-buffered solution (PBS) and various concentrations of sample solution (15, 17, 20, 24, 30 and 40 μg/mL) were added to the blank control and sample groups, respectively. Meanwhile, 10 μL of different concentrations of Trolox standard solution (0.15, 0.3, 0.6, 0.9, 1.2 and 1.5 mM) was added into the standard curve group. Afterwards, 170 μL ABTS diluted solution was added and gently mixed well. The reacted system was incubated at ambient temperature for 6 min. Finally, the absorption value was determined at 414 nm. Standard curve was plotted according to the absorbance D-value of the control and standard groups against the corresponding Trolox concentration, expressed as Y = aX + b (Y represents the D-values between control and standard groups and X is the concentration of Trolox standard). Ascorbic acid was used as the positive control. The ABTS free-radical scavenging activity of the sample was calculated by substituting the Y value (the D-values between control and sample groups) into the standard curve and represented as a standard equivalent to Trolox (mM) according to the established calibration curve.

2.7. Measurement of α-glucosidase activity in vitro

2.7.1. α-Glucosidase inhibition activity

The α-glucosidase inhibition of NSP anthocyanin was investigated as reported by Dong et al (Dong, Hu, Yue, & Wang, 2021). First, 20 μL of anthocyanin solution with various concentrations (0.04, 0.08, 0.12, 0.16, 0.20 and 0.24 mg/mL) and 80 μL of PBS (0.1 mM) were mixed sufficiently in a 96-well plate. Next, 50 μL of PBS and α-glucosidase solution fixed at 1 U/mL were separately added into the anthocyanin sample control and experimental groups. The mixed system was pre-incubated for 30 min at 37 °C. Then, 0.5 mM of pNPG solution was added and well-mixed for another incubation at 37 °C for 30 min. Afterwards, 0.1 mol/L Na2CO3 solution was added to terminate the reaction system. Finally, the absorbance value was determined at 405 nm using a microplate reader. Acarbose was employed as the positive control. The inhibition rate for α-glucosidase was calculated according to the formula below.

| (4) |

where A1, A2, A and A0 represent the absorbance of the sample group (containing the PBS buffer, enzyme, sample extracts, pNPG and Na2CO3 solution), the sample control group without enzyme, the blank group without the sample, and the blank control group without the sample and enzyme, respectively.

2.7.2. Enzyme kinetics of α-glucosidase inhibition

The inhibition types of NSP anthocyanin against α-glucosidase were measured as previously reported (Lin, Chai, Zheng, Huang, & Ou-Yang, 2019). The concentration of pNPG substrates was fixed at 0.5 mmol/L. Various enzyme concentrations (0.05, 0.10, 0.20, 0.40 and 0.80 U) and NSP anthocyanin concentrations (0, 0.06, 0.12 and 0.24 mg/mL) were provided. To confirm the mechanism involved in the inhibition of α-glucosidase by NSP anthocyanin, enzyme kinetic research was performed via Lineweaver–Burk and Dixon plots. Enzyme concentration was fixed at 0.4 U and various concentrations of NSP anthocyanin (0, 0.03, 0.06 and 0.12 mg/mL) and pNPG substrates (0.125, 0.25, 0.5, 1.0 and 2.0 mmol/L) were provided. In addition, various concentrations (0.5, 1.0, 2.0 and 4.0 mg/mL) were considered for the positive control acarbose. The double reciprocal lines of initial velocity (ν) against substrate concentration were plotted and applied for determining the Michaelis–Menten constant (Km) and maximum reaction velocity (Vmax) through the Michaelis–Menten model. The Lineweaver–Burk equation was used to clarify the inhibition mechanism in the form of a double reciprocal form.

| (5) |

where ν represents the velocity of the enzymatic reaction in the absence of NSP anthocyanin or acarbose. Ki and Km are the inhibition and Michaelis-Menten constants. [I] and [S] stand for the concentrations of NSP anthocyanin or acarbose and pNPG, respectively.

2.7.3. Molecular docking and molecular dynamic simulation

To explain the possible mechanism involved in the inhibition of α-glucosidase by NSP anthocyanin, the identified compounds were further subjected to molecular docking using sailvinav1.0. The three-dimensional (3D) crystallographic structures of α-glucosidase derived from yeast are unavailable. Fortunately, the crystal structure of human lysosomal acid-α-glucosidase (PDB ID: 8CB1) is available and acquired from the protein database (http://www.rcsb.org/ pdb). The protein crystal structure was modified by the deleting the water molecules and adding polar hydrogen atoms. The 2D structures of the compounds were downloaded from the Pubchem Data Bank (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) or drawn by Chemdraw software. Then the structures were converted to 3D format by sailvina software and treated with the addition of hydrogen atoms, charges, and energy minimization. Finally, the docked model was chosen to be the most favorable binding mode for further analysis in terms of the lowest binding energy of α-glucosidase and anthocyanin compounds. The protein–ligand interactions were visualized using AutoDock Vina.

The main anthocyanin of C3G was selected for the molecular dynamic simulation research. The GROMACS 2020.6 software package, charm 36 all-atom force field and TIP3P water model were employed for studying the C3G–α-glucosidase complexes. The scan time and time interval were set at 10,000 ps and 2 ps, respectively (Yao et al., 2022). System balancing involved two steps: 2 ns NVT (constant temperature and volume appropriate thermodynamic ensemble) and 2 ns NPT (constant temperature, pressure and particle number). Data analysis was performed using QtGrace v.0.2.6.

2.8. Statistics analysis

The Design-Expert software 8.0.5b (State-East, Inc. Minneapolis, USA) was used for the RSM analysis. All studies were conducted at least three times independently, and the data were expressed as the mean ± standard error of mean. GraphPad Prism 7.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc., CA, USA) was employed for statistical analysis. Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05 in terms of one-way ANOVA analysis.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Optimization of anthocyanic extraction by SWE

The detailed variables for each group of the BBD design are listed in Table 1, and the corresponding experimental response values (within the range of 0.606–1.005 mg/g) obtained under different conditions are also displayed. The AEs yield of NSP anthocyanin was assessed using the polynomial equation below, based on the regression analysis of the experimental data. Meanwhile, the relation between quadratic, linear and interaction terms for the predicted response could be explained in terms of the following eq.

| (6) |

Table 1.

Experimental design and results for response surface analysis.

| Run | Factor |

Y |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| X1 Extraction temperature (°C) |

X2 Extraction time (min) |

X3 Flow rate (mL/min) |

AEs yield mg/g |

|

| 1 | 130 | 45 | 7 | 0.963 |

| 2 | 140 | 30 | 7 | 0.788 |

| 3 | 130 | 60 | 6 | 0.756 |

| 4 | 130 | 45 | 7 | 0.958 |

| 5 | 120 | 60 | 7 | 0.817 |

| 6 | 120 | 45 | 6 | 0.795 |

| 7 | 130 | 45 | 7 | 1.005 |

| 8 | 120 | 30 | 7 | 0.627 |

| 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 |

130 130 140 130 140 120 140 130 130 |

60 30 60 45 45 45 45 45 30 |

8 6 7 7 6 8 8 7 8 |

0.606 0.634 0.850 0.891 0.961 0.764 0.913 1.001 0.803 |

The analysis results of the response surface experimental design and the adequacy as well as suitability of the model are summarized in Table S2. The F value of the model fitted by BBD was 0.0072 (P < 0.05), where the lack of fit of the model was 2.62 (P > 0.05). These results indicated that the model is applicable and significant according to the ANOVA analysis.

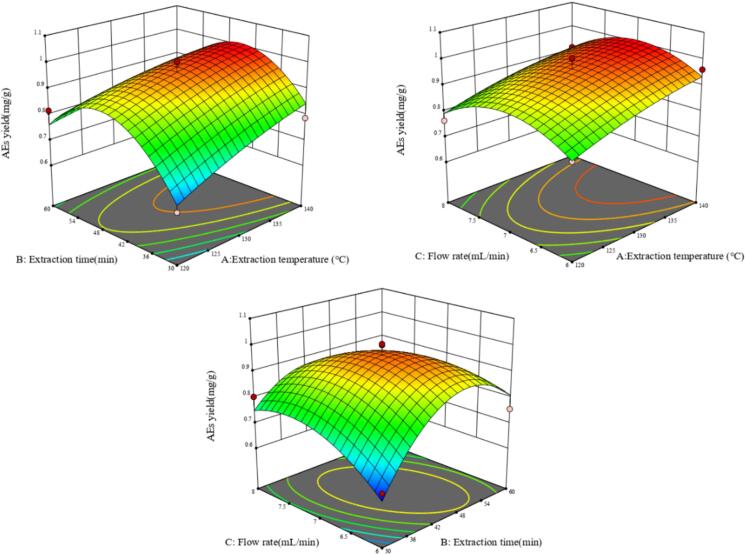

The effects of various factors on the AEs yield were determined based on the F values. The higher F value implied a better effect on a response variable. As shown in Table S2, only the effects of X1, X2X3, X22 and X32 were significant (P < 0.05). Among the three independent variables, the influence order on the response was X1 (extraction temperature) ˃ X2 (extraction time) ˃ X3 (flow rate). The 3D response surface charts representing the influence of interactive variables on the AEs yield were displayed in Fig. 1. Each pair of factors within the experimental range was plotted in 3D surface graphs, whereas the level of the other variable was set at zero and kept unchanged. If there were higher inclines and slopes, the interaction between two variables would be more significant. As shown in Fig. 1, significant interaction existed between X2 and X3 (P < 0.05). However, the interaction among the other pairs of factors was insignificant (P > 0.05).

Fig. 1.

3D response surface plots for the interactive effects of independent variables on AEs yield.

Based on experimental results, the optimal conditions were predicted as follows: extraction temperature140 °C, extraction time 44.77 min and flow rate 6.94 mL/min. From the perspective of convenient operation, the modified extraction conditions were as follows: extraction temperature 140 °C, extraction time 45 min and flow rate 7 mL/min. The validity of the model was confirmed and three parallel experiments were conducted. AEs yield of 1.075 mg/g was achieved, which was close to the predicted theoretical value of 1.010 mg/g. These results indicated that the employed model was appropriate to reflect the prospective process optimization.

3.2. Comparison of SWE with other extraction methods

Two conventional extraction techniques of methanol extraction (ME) and hot water extraction (HWE) were compared with SWE. The AEs yield under the optimal conditions (140 °C, 45 min and 7 mL/min) of SWE could reach 1.075 mg/g. By contrast, the obtained AEs yields via ME and HWE were 0.996 and 0.845 mg/g, respectively, which were lower than that of SWE. It is commonly recommended that anthocyanic extraction should be conducted at low temperatures because the susceptibility to heat could induce the degradation of anthocyanin compounds. The results obtained in our research showed that NSP anthocyanins could be effectively extracted by SWE compared with traditional approaches. This result is consistent with many reports on subcritical extraction of anthocyanins (Ju & Howard, 2006; Kang et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2021). This is probably because that the thermodynamic properties of water, including viscosity, surface tension and dielectric constant, remarkably change under subcritical state, which could improve the efficiency and selectivity of the extraction (Ju & Howard, 2006). The ability of solvent to extract anthocyanins at elevated temperatures is because of the high superficial fluid velocity of the solvents through the extraction cell. In addition, the mass transfer for active ingredients was enhanced, making the decreased solvent polarity increase the solubility of anthocyanin in water (Kuasnei et al., 2022). These findings confirm the significant benefits of SWE: green extraction solvent and ideal extraction yields. Therefore, SWE is an economical, environment-friendly technology to extract biologically active ingredients in the food industry.

3.3. Identification of anthocyanin compounds via UPLC–triple–TOF–MS/MS

The anthocyanin composition was identified based on molecular and ion fragments, retention time, molecular weight and reported references (Chen et al., 2021; Saha et al., 2020; Sang, Zhang, Sang, & Li, 2018; M. Zhang et al., 2017; Zheng et al., 2011). The UPLC chromatogram of anthocyanic extract was displayed in Fig. 2. The corresponding MS/MS spectra, structures and data information are separately displayed in Figs. S1, S2 and Table 2. Eight anthocyanins were detected, which belonged to 4 types such as cyanidin (compounds 1, 4 and 8), delphinidin (compound 2), petunidin (compounds 3, 6 and 7) and pelargonidin (compound 5) derivatives. The mass of m/z 287 was attributed to cyanidin compounds. Compound 1 exhibited a molecular-ion mass of m/z 611.1583, in which the fragment [M + H − 324]− was cleaved to produce the fragment ion m/z 287.0536, indicating that a diglucoside molecule was missed. Based on molecular and ion fragments, retention time, molecular weight, and reported references, compound 1 should be cyanidin-3-O-diglucoside (Sang et al., 2018; M. Zhang et al., 2017; Zheng et al., 2011). For compound 4, the missing fragment [M + H − 470]− was speculated as a single ion fragment product formed when a coumarin-acylated diglucoside moiety was detached from aglycone. Then compound 4 was identified as cyanidin-3-O-(trans-p-coumaroyl)-diglucoside, which was further confirmed by the standard in subsequent experiments as the main ingredient of NSP anthocyanin. Similarly, as an isomer of compound 4, compound 8 was characterized as cyanidin-3-O-(trans-p-coumaroyl)-glucoside-5-O-glucoside (Hu et al., 2014; Zheng et al., 2011). A mass of m/z 303 corresponded to the characteristic fragment of delphinidin derivatives. With the loss of two hexoses and one coumarin acid group (corresponding to the total mass of the missing fragment [M + H − 470]), compound 2 was identified as delphinidin-3-O-(trans-p-coumaroyl)-glucoside-5-O-glucoside (Sang et al., 2018). The fragment ion with m/z 317 represents a petunidin compound. The fragment [M + H − 616] was generated by the splitting of molecular ion with m/z 933.2736. In addition, it is speculated that the molecule disposed coumaroyl rutinoside and glucoside at sites 3 and 5, respectively. Ultimately, compound 3 was inferred as petunidin-3-O-(p-coumaroylrutinoside)-5-O-glucoside (Saha et al., 2020). Compounds 6 and 7 were the isomers of petunidin anthocyanins. The disposed fragment of [M + H − 308] comprised coumaroyl glucoside. The trans and cis isomers could be distinguished by corresponding proportion and peak time. The polarity of cis-coumaroyl-anthocyanin was higher than that of trans-coumaroyl-anthocyanin; therefore, it could be earlier eluted by a C18 chromatographic column (M. Zhang et al., 2017; Zheng et al., 2011). Compounds 6 and 7 were speculated as petunidin-3-O-(cis-p-coumaroyl)-glucoside and petunidin-3-O-(trans-p-coumaroyl)-glucoside, respectively (M. Zhang et al., 2017). The specific ion peak at m/z 271 was identified as the parent nucleus of pelargonidin derivatives. The lost fragment [M + H − 470] represented the loss of coumarin-acylated diglucoside, and compound 5 was confirmed as pelargonidin-3-O-(trans-p-coumaroyl)-diglucoside (Sang et al., 2018). In brief, 3 cyanidin, 3 petunidin, 1 delphinidin and 1 pelargonidin anthocyanins were detected in the NSP anthocyanic extract. Among them, monoglucoside, diglucosides, coumaroylated derivatives as well as cis and trans isomers were detected. Moreover, petunidin-3-O-(p-coumaroylrutinoside)-5-O-glucoside and cyanidin-3-O-(trans-p-coumaroyl)-glucoside-5-O-glucoside were first reported in NSP berries.

Fig. 2.

UPLC chromatogram for anthocyanin constituents in NSP extract at 520 nm.

Table 2.

Identification of NSP anthocyanin by UPLC-Triple-TOF MS/MS.

| NO | RT | [M + H]+ (m/z) | MS/MS fragments | Formula | Compounds | CID |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5.74 | 611.1583 | 287.0536 | C27H31O16 | Cyanidin-3-O-diglucoside | 11,968,393 |

| 2 | 9.03 | 773.1906 | 303.0495 | C36H37O19 | Delphinidin-3-O-(trans-p-coumaroyl)-glucoside-5-O-glucoside | 101,633,884 |

| 3 | 10.73 | 933.2736 | 317.0647 | C43H49O23 | Petunidin-3-O-(p-coumaroylrutinoside)-5-O-glucoside) | 170,836,262 |

| 4 | 11.24 | 757.1949 | 287.0551 | C36H37O18 | Cyanidin-3-O-(trans-p-coumaroyl)-diglucoside | – |

| 5 | 14.34 | 741.1986 | 271.0598 | C36H37O17 | Pelargonidin-3-O-(trans-p-coumaroyl)-diglucoside | – |

| 6 | 17.72 | 625.1727 | 317.0647 | C31H29O14 | Petunidin-3-O-(cis-p-coumaroyl)-glucoside | 101,753,346 |

| 7 | 19.58 | 625.1732 | 317.0650 | C31H29O14 | Petunidin-3-O-(trans-p-coumaroyl)-glucoside | 101,753,346 |

| 8 | 23.31 | 757.1953 | 287.0549 | C36H37O18 | Cyanidin-3-O-(trans-p-coumaroyl)-glucoside-5-O-glucoside | 443,623 |

3.4. Semi-quantification of anthocyanin by HPLC

Based on the analysis results of the anthocyanic extract, cyanidin-3-O-(trans-p-coumaroyl)-diglucoside (C3G) is the predominant ingredient and proportion of entire accounts for >80% of the whole anthocyanins. Therefore, the semi-quantification of anthocyanin was performed by HPLC based on C3G as the standard substance, and the corresponding chromatogram is shown in Fig. S3. The calibration curve was generated by plotting the peak areas vs. various content of compound C3G in the range of 0.2–4 μg. The standard curve is expressed as equation of Y = 1068.8X – 1.2421 (Y: peak area and X: C3G content). The linear correlation coefficient of R2 was 1. Base on the above result, the content of anthocyanin was 1.27 mg/g, which was a little higher than the data acquired by the pH-differential method.

3.5. Antioxidant activity in vitro

The DPPH free-radical scavenging abilities of NSP and ascorbic acid are displayed in Fig. S4a. These two tested substances exhibited excellent scavenging effects in a dose-dependent manner within the range of 0.8–3.6 μg/mL. Moreover, NSP anthocyanin exhibited higher DPPH free-radical scavenging effect than that of ascorbic acid, and their IC50 values were 1.274 ± 0.0138 μg/mL and 3.4828 ± 0.0315 μg/mL, respectively. ABTS free-radical scavenging capacity is also a common assay used to assess antioxidant activity of natural product from plant samples. Similarly, the scavenging activities of NSP anthocyanin and ascorbic acid were dramatically enhanced along with the increased concentration, which also displayed concentration-dependent characteristics (Fig. S4b). The standard curve was drawn by plotting the D-value of the control and sample groups vs. various concentrations and expressed as Y = 1.2624X – 0.011 (Y: absorption value and X: Trolox concentrations) with the linear correlation coefficient R2 of 0.9984. However, the NSP anthocyanin displayed weaker scavenging effect compared with ascorbic acid. The ABTS free-radical scavenging activities of anthocyanin and ascorbic acid were equivalent to 0.9738 ± 0.1433 and 1.9903 ± 0.1876 mM Trolox at a concentration of 40 μg/mL, respectively. Based on the results of antioxidant activity, NSP anthocyanin exhibited strong antioxidant activity, which could be used as a strong antioxidant in daily dietary.

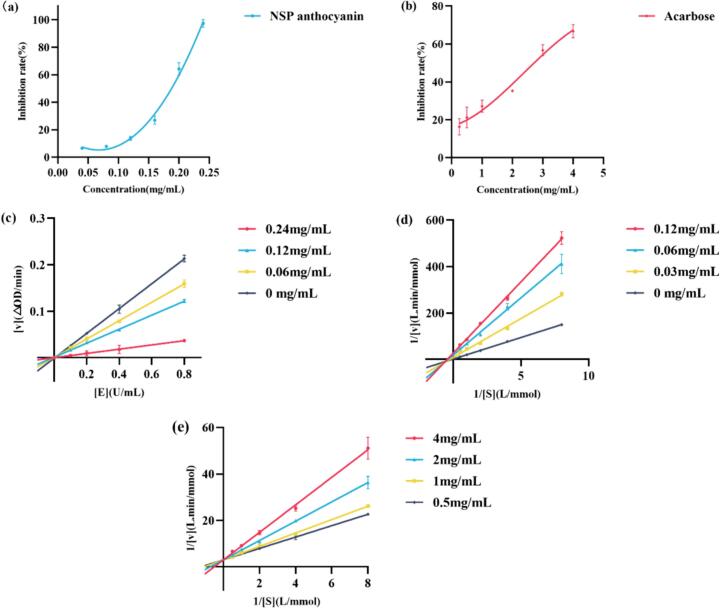

3.6. Inhibition activity of α-glucosidase in vitro

The α-glucosidase inhibition activity of the NSP anthocyanic extract was investigated and displayed in Fig. 3a. Correspondingly, the inhibition effect of acarbose against α-glucosidase was exhibited in Fig. 3b. The enzyme inhibition rate increased as the concentration of NSP anthocyanin and acarbose increased, which indicated that the significant inhibitory activity of the two substances was in a dose-dependent manner. The IC50 values of NSP anthocyanin and acarbose were calculated as 0.1807 ± 0.0135 and 2.4980 ± 0.1016 mg/mL, respectively. The comparative result of IC50 values suggested that the α-glucosidase inhibitory activity of NSP anthocyanin was superior to that of the positive drug, which was almost 14 times of that of acarbose. Therefore, NSP is a promising candidate in the development of potential anti-diabetic drugs.

Fig. 3.

Inhibitory effect of NSP anthocyanin and acarbose on α-glucosidase inhibition activity (a); inhibitory activity of NSP anthocyanin on α-glucosidase; (b), inhibitory activity of acarbose on α-glucosidase; (c) inhibitory mechanism of NSP anthocyanin on α-glucosidase; (d) enzyme kinetics of NSP anthocyanin on α-glucosidase; (e) enzyme kinetics of acarbose on α-glucosidase.

3.7. Inhibitory mechanism of NSP anthocyanin on α-glucosidase

The inhibitory mechanism could be speculated from the kinetic diagram of the inhibitor against the enzyme. The reversibility of NSP anthocyanin against α-glucosidase was estimated by a plot of reaction rate (v) vs. enzyme concentration ([E]) at various anthocyanin concentrations. As demonstrated in Fig. 3c, all lines passed through the origin and the slopes reduced with the increase in anthocyanin concentration, which denoted that anthocyanin acted on α-glucosidase activity and had no effect on enzyme dosage. It could be concluded that there were noncovalent interactions between α-glucosidase and NSP anthocyanin. Therefore, the inhibitory effect of anthocyanin on α-glucosidase was reversible.

3.8. Inhibitory kinetics of anthocyanin on α-glucosidase

Enzyme kinetics was conducted to evaluate the α-glucosidase inhibitory mechanism of anthocyanic extract. Based on the Lineweaver–Burk double reciprocal curve plot, the inhibition kinetics curves of NSP anthocyanin and acarbose were obtained to measure the inhibition type and constant. The kinetic parameters were calculated and shown in Table S3. The values of Vmax and Km decreased along with the increase in NSP concentration. The slope of the straight line increased with the increase in anthocyanin concentration and all straight lines intersected in the third quadrant (Fig. 3d). The above results indicated that the inhibitory effect of anthocyanin on α-glucosidase belonged to mixed competitive inhibition. For acarbose, the Km value increased along with the increase in NSP concentration. However, the Vmax value remained unchanged. In addition, all straight lines intersected at a point located on the Y-axis, which denoted that it belonged to competitive inhibition (Fig. 3e). This result was consistent with that of previous literature (Li, Yang, Wang, Ma, & Peng, 2023). Ki is the dissociation constant of the inhibitor, which indicates the binding ability of the inhibitor to the enzyme. The smaller the Ki, the better the inhibitory activity. The values of Ki were calculated to be 8.0052 ± 0.2531 and 99.2586 ± 0.2734 μg/mL for NSP and acarbose respectively, according to Eq. (5), which indicated that the inhibition of NSP on α-glucosidase was stronger than that of acarbose.

3.9. Molecular docking and molecular dynamic simulation

Molecular docking was used to analyze the eight anthocyanin compounds to reflect the possible mechanism on α-glucosidase. The 3D and 2D models of anthocyanins and acarbose subjected to α-glucosidase are exhibited in Figs. 4 and S5, respectively. The results for the affinity and interaction, including van der Waals, hydrogen bond, pi-pi stacked, pi-Anion, carbon hydrogen bond, pi-sigma, pi-alkyl, unfavorable acceptor-acceptor, pi‑sulfur interactions, between α-glucosidase and anthocyanin are demonstrated in Table S4. The affinity values between α-glucosidase and anthocyanin compounds were in the range of −9.4 to −8.0 kcal/mol (Table S4), indicating that strong binding force exists between enzyme and ligands. Moreover, all affinity values were lower than that of acarbose −7.1, which was consistent with the α-glucosidase inhibition experimental result. The binding forces among proteins and ligands were mainly van der Waals and hydrogen bonds.

Fig. 4.

The 3D model for the interaction between compounds and α-glucosidase.

The parameters of root mean square deviation (RMSD; Fig. S6a) and root mean square fluctuation (RMSF; Fig. S6b) were applied for the analysis of structural change, dynamic stability of C3G and enzyme complex systems. The stability of the C3G–enzyme complex system was analysed with a set RMSD value of 60 ns. The RMSD values of the complex system undulated in the range of 0.2 nm after 4 ns, indicating that the system was relatively stable in the later period of C3G–enzyme combination. RMSF was used to analyze the changes in ligand atom positions and enzyme chain residues under particular temperatures and pressures. The RMSF values of most residues of α-glucosidases combined with C3G were <2 nm, indicating that they possessed fairly stable configurations.

Anthocyanin 1–8 (a-h) and acarbose (i).

4. Conclusion

The study employed green extraction technology of SWE to obtain NSP anthocyanins and optimize the extraction process via RSM. The anthocyanic extraction yield 1.075 mg/g could be achieve under the optimal extraction conditions: temperature 140 °C, extraction time 45 min and flow rate 7 mL/min. The anthocyanic extraction yield under these conditions was higher than that obtained through conventional extraction methods. Eight anthocyanins i.e. 3 cyanidin, 3 petunidin, 1 delphinidin and 1 pelargonidin compounds were identified in the extract. The semi-quantification of the anthocyanic extract was also conducted via HPLC. The anthocyanic extract exhibited excellent DPPH free-radicals scavenging effects, which was better than that of ascorbic acid with an IC50 value of 1.274 ± 0.0138 μg/mL. Moreover, the anthocyanic extract exhibited strong inhibition of α-glucosidase activity, which was ∼14 times higher than that of the positive drug acarbose. The inhibitory kinetics mechanism of NSP anthocyanin was a mixed competitive inhibitor in a reversible way. Bioinformatics research predicted that the stable composite structures formed between anthocyanin and α-glucosidase were mainly dominated by hydrogen bonding and van der Waals force. Therefore, NSP anthocyanin is a potential α-glucosidase inhibitor and can be applied for the development of hypoglycemic functional foods. This research provides a novel extraction technology and supports scientific data for the development and utilization of NSP anthocyanin in the food industry in the future.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Lichengcheng Ren: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Qi Dong: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Methodology. Zhenhua Liu: Investigation, Formal analysis. Yue Wang: Methodology, Formal analysis. Nixia Tan: Visualization, Investigation. Honglun Wang: Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition. Na Hu: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the Youth Innovation Promotion Association, CAS (2020426), Qinghai Provincial Science and Technology Major Project (2023-SF-A5) and Qinghai Province Kunlun Talents Program (2022).

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fochx.2024.101626.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary material

Data availability

The data that has been used is confidential.

References

- Basak S., Annapure U.S. The potential of subcritical water as a “green” method for the extraction and modification of pectin: A critical review. Food Research International. 2022;161 doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2022.111849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Z., Qu Z., Lan Y., Zhao S., Ma X., Wan Q.…Li P. Conventional, ultrasound-assisted, and accelerated-solvent extractions of anthocyanins from purple sweet potatoes. Food Chemistry. 2016;197(Pt A):266–272. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.10.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camara J.S., Locatelli M., Pereira J.A.M., Oliveira H., Arlorio M., Fernandes I.…Bordiga M. Behind the scenes of anthocyanins-from the health benefits to potential applications in food, pharmaceutical and cosmetic fields. Nutrients. 2022;14(23) doi: 10.3390/nu14235133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S., Zhou H., Zhang G., Dong Q., Wang Z., Wang H., Hu N. Characterization, antioxidant, and neuroprotective effects of anthocyanins from Nitraria tangutorum Bobr. fruit. Food Chemistry. 2021;353 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.129435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong Q., Hu N., Yue H., Wang H. Inhibitory activity and mechanism investigation of Hypericin as a novel alpha-glucosidase inhibitor. Molecules. 2021;26(15) doi: 10.3390/molecules26154566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falletti P., Vázquez M.F.B., Rodrigues L.G.G., Santos P.H., Lanza M., Cabrera J.L.…Comini L.R. Optimization of the subcritical water extraction of sulfated flavonoids from Flaveria bidentis. Journal of Supercritical Fluids. 2023;199 doi: 10.1016/j.supflu.2023.105958. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gravel E., Poupon E. Biosynthesis and biomimetic synthesis of alkaloids isolated from plants of the Nitraria and Myrioneuron genera: An unusual lysine-based metabolism. Natural Product Reports. 2010;27(1):32–56. doi: 10.1039/b911866g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong H.T., Netzel M.E., O’Hare T.J. Optimisation of extraction procedure and development of LC-DAD-MS methodology for anthocyanin analysis in anthocyanin-pigmented corn kernels. Food Chemistry. 2020;319 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.126515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu N., Zheng J., Li W., Suo Y. Isolation, stability, and antioxidant activity of anthocyanins from Lycium ruthenicum Murray and Nitraria Tangutorum Bobr of Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Separation Science and Technology. 2014;49(18):2897–2906. doi: 10.1080/01496395.2014.943770. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huo J., Ni Y., Li D., Qiao J., Huang D., Sui X., Zhang Y. Comprehensive structural analysis of polyphenols and their enzymatic inhibition activities and antioxidant capacity of black mulberry (Morus nigra L.) Food Chemistry. 2023;427 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2023.136605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang S., Chen C., Dong Q., Shao Y., Zhao X., Tao Y., Yue H. Alkaloids and phenolics identification in fruit of Nitraria tangutorum Bobr. by UPLC-Q-TOF-MS/MS and their a-glucosidase inhibitory effects in vivo and in vitro. Food Chemistry. 2021;364 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.130412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ju Z., Howard L.R. Subcritical water and sulfured water extraction of anthocyanins and other phenolics from dried red grape skin. Journal of Food Science. 2006;70(4):S270–S276. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.2005.tb07202.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kang H.J., Ko M.J., Chung M.S. Anthocyanin structure and pH dependent extraction characteristics from blueberries (Vaccinium corymbosum) and chokeberries (Aronia melanocarpa) in subcritical water state. Foods. 2021;10(3) doi: 10.3390/foods10030527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuasnei M., Wojeicchowski J.P., Santos N.H., Pinto V.Z., Ferreira S.R.S., Zielinski A.A.F. Modifiers based on deep eutectic mixtures: A case study for the extraction of anthocyanins from black bean hulls using high pressure fluid technology. Journal of Supercritical Fluids. 2022;191 doi: 10.1016/j.supflu.2022.105761. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumari P.K., Umakanth A.V., Narsaiah T.B., Uma A. Exploring anthocyanins, antioxidant capacity and α-glucosidase inhibition in bran and flour extracts of selected sorghum genotypes. Food Bioscience. 2021;41 doi: 10.1016/j.fbio.2021.100979. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Yang J., Wang M., Ma X., Peng X. Studies on the inhibition of alpha-glucosidase by biflavonoids and their interaction mechanisms. Food Chemistry. 2023;420 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2023.136113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin M.Z., Chai W.M., Zheng Y.L., Huang Q., Ou-Yang C. Inhibitory kinetics and mechanism of rifampicin on alpha-glucosidase: Insights from spectroscopic and molecular docking analyses. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2019;122:1244–1252. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.09.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Li L., Wu W., Zhang G., Zheng Y., Ma C.…Xu Z. Green extraction of active ingredients from finger citron using subcritical water and assessment of antioxidant activity. Industrial Crops and Products. 2023;200 doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2023.116821. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ma T., Hu N., Ding C., Zhang Q., Li W., Suo Y.…Ding C. In vitro and in vivo biological activities of anthocyanins from Nitraria tangutorun Bobr. fruits. Food Chemistry. 2016;194:296–303. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.07.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikucka W., Zielinska M., Bulkowska K., Witonska I. Subcritical water extraction of bioactive phenolic compounds from distillery stillage. Journal of Environmental Management. 2022;318 doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2022.115548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunes Mattos G., de Araujo P., Santiago M.C., Sampaio Doria Chaves A.C., Rosenthal A., Valeriano Tonon R., Correa Cabral L.M. Anthocyanin extraction from Jaboticaba skin (Myrciaria cauliflora Berg.) using conventional and non-conventional methods. Foods. 2022;11(6) doi: 10.3390/foods11060885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ordóñez-Santos L.E., Esparza-Estrada J., Vanegas-Mahecha P. Ultrasound-assisted extraction of total carotenoids from mandarin epicarp and application as natural colorant in bakery products. LWT- Food Science and Technology. 2021;139 doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2020.110598. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Panchal S.K., John O.D., Mathai M.L., Brown L. Anthocyanins in chronic diseases: The power of purple. Nutrients. 2022;14(10) doi: 10.3390/nu14102161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu D., Zhu G., Bhat M.A., Wang L., Liu Y., Sang L.…Sun N. Water use strategy of nitraria tangutorum shrubs in ecological water delivery area of the lower inland river: Based on stable isotope data. Journal of Hydrology. 2023;624 doi: 10.1016/j.jhydrol.2023.129918. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saha S., Singh J., Paul A., Sarkar R., Khan Z., Banerjee K. Anthocyanin profiling using UV-vis spectroscopy and liquid chromatography mass spectrometry. Journal of AOAC International. 2020;103(1):23–39. doi: 10.5740/jaoacint.19-0201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sang J., Zhang Y., Sang J., Li C.-Q. Anthocyanins from Nitraria tangutorun: Qualitative and quantitative analyses, antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities and their stabilities as affected by some phenolic acids. Journal of Food Measurement and Characterization. 2018;13(1):421–430. doi: 10.1007/s11694-018-9956-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Song Q., Xia X., Ji C., Chen D., Lu Y. Optimized flash extraction and UPLC-MS analysis on antioxidant compositions of Nitraria sibirica fruit. Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis. 2019;172:379–387. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2019.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ursu M.G.S., Milea S.A., Pacularu-Burada B., Dumitrascu L., Rapeanu G., Stanciu S., Stanciuc N. Optimizing of the extraction conditions for anthocyanin’s from purple corn flour (Zea mays L): Evidences on selected properties of optimized extract. Food Chemistry: X. 2023;17 doi: 10.1016/j.fochx.2022.100521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Ye Y., Wang L., Yin W., Liang J. Antioxidant activity and subcritical water extraction of anthocyanin from raspberry process optimization by response surface methodology. Food Bioscience. 2021;44 doi: 10.1016/j.fbio.2021.101394. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wrolstad M.M.G.R.E. Characterization and measurement of anthocyanins by UV-visible spectroscopy. Current Protocols in Food Analytical Chemistry. 2001 doi: 10.1002/0471142913.faf0102s00. F1.2.1-F1.2.13. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu S., Fang D., Tian X., Xu Y., Zhu X., Wang Y.…Ma L. Subcritical water extraction of bioactive compounds from waste cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) flowers. Industrial Crops and Products. 2021;164 doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2021.113369. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yao H., Liu J., Xu M., Ji J., Dai Q., You Z. Discussion on molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of the asphalt materials. Advances in Colloid and Interface Science. 2022;299 doi: 10.1016/j.cis.2021.102565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M., Ma J., Bi H., Song J., Yang H., Xia Z.…Wei L. Characterization and cardioprotective activity of anthocyanins from Nitraria tangutorum Bobr. by-products. Food & Function. 2017;8(8):2771–2782. doi: 10.1039/c7fo00569e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang P., Zhang F., Wu Z., Cahaeraduqin S., Liu W., Yan Y. Analysis on the salt tolerance of Nitraria sibirica Pall. based on Pacbio full-length transcriptome sequencing. Plant Cell Reports. 2023;42(10):1665–1686. doi: 10.1007/s00299-023-03052-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao T., Ding Y., Sun W., Turghun C., Han B. Ultrasonic-assisted extraction of flavonoids from Nitraria sibirica leaf using response surface methodology and their anti-proliferative activity on 3T3-L1 preadipocytes and antioxidant activities. Journal of Food Science. 2023;88(6):2325–2338. doi: 10.1111/1750-3841.16612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng J., Li H., Ding C., Suo Y., Wang L., Wang H. Anthocyanins composition and antioxidant activity of two major wild Nitraria tangutorun Bobr. variations from Qinghai–Tibet Plateau. Food Research International. 2011;44(7):2041–2046. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2010.07.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu L., Li M., Huo J., Lian Z., Liu Y., Lu L.…Chen J. Overexpression of NtSOS2 from halophyte Plant N. tangutorum enhances tolerance to salt stress in Arabidopsis. Frontiers in Plant Science. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fpls.2021.716855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material

Data Availability Statement

The data that has been used is confidential.