Abstract

Background & Objective:

The regulator of chromosome condensation 2 (RCC2) and RAS-related C3 botulinum toxin substrate 1 (Rac1) have been implicated in the promotion of breast cancer cell proliferation and migration. The signaling pathway involving p53/RCC2/Rac1 has been proposed to contribute to the regulation of colon cancer metastasis. However, until now, this pathway has not been thoroughly investigated in breast cancer. This study seeks to explore the influence of immunohistochemical expression and the correlation among RCC2, Rac1, and p53 in breast infiltrating ductal carcinoma (IDC).

Methods:

Immunostaining was performed on 120 breast IDC specimens using RCC2, Rac1, and p53 antibodies. Statistical analyses were conducted to examine the correlations between these antibodies.

Results:

A Positive expression of RCC2, Rac1, and p53 was observed in 116 (96.7%), 120 (100%), and 33 (27.5%) of the breast cancer cases, respectively. RCC2, Rac1, and p53 demonstrated association with poor prognostic parameters such as frequent mitoses, high Ki-67 status, positive lymphovascular invasion (LVI), and advanced tumor stage. A highly significant direct correlation was found between each immunohistochemical marker and the other two markers. Shorter overall survival was linked to multifocal tumors (P=0.017), advanced tumor stage (T3) (P=0.010), Luminal B subtype (P=0.015), progressive disease (P=0.003), positive Her2neu status (P=0.008), and metastasis to distant organs (P<0.001). However, RCC2, Rac1, and p53 did not exhibit a significant association with overall survival.

Conclusion:

The high expression levels of RCC2, Rac1, and p53 in breast IDC suggest their potential role in tumor behavior. The association of RCC2 and Rac1 with poor prognostic parameters may serve as predictive indicators for aggressive tumors, thus implying that targeted therapy could be beneficial in the treatment of breast cancer.

Key Words: Breast neoplasms, Cell cycle proteins, Rac1 GTP-binding protein, Tumor suppressor protein p53

Introduction

Globally, breast cancer ranks as the most frequently diagnosed cancer in females and stands as the second leading cause of cancer-related mortality among women (1). In Egypt, breast cancer represents the predominant malignancy in women, comprising 32.4% of all cancers in this demographic (2). Infiltrating duct carcinoma (IDC) emerges as the prevailing form of breast cancer (3).

The regulator of chromosome condensation 2 (RCC2) has been implicated in breast cancer by fostering cell proliferation and migration (4). RAS-related C3 botulinum toxin substrate 1 (Rac1) is involved in regulating various aspects of the tumor cell cycle, apoptosis, proliferation, invasion, migration, and angiogenesis (5). Furthermore, it has been suggested to modulate tumor stem cells and facilitate tumor genesis (6), potentially influencing drug resistance and prognosis in cancer patients (7).

The p53 protein is known to regulate critical cellular processes such as the cell cycle, DNA repair, and apoptosis. It governs genes implicated in metastatic pathways, including cell adhesion, motility, and invasion (8). In normal cells, p53 exhibits transient expression and a very short half-life. However, mutation in the p53 gene results in protein stabilization within the cell nucleus, compromising its growth-suppressing function and fostering cellular proliferation and anti-apoptotic activities, particularly during cellular quiescence (9).

A previous study on colon cancer revealed that p53 activates RCC2 transcription by binding to its promoter. RCC2 deficiency induces alterations in cell morphology and activates Rac1, promoting cell migration. This underscores the potential involvement of the p53/RCC2/Rac1 signaling pathway in colon cancer metastasis regulation (10). Nevertheless, the correlation among p53/RCC2/Rac1 proteins in breast carcinoma remains unexplored. Thus, the objective of this study is to examine the immunohistochemical expression and correlation of RCC2, Rac1, and P53 in breast IDC and investigate their prognostic implications and associations with various clinicopathological parameters.

Material and Methods

This retrospective study comprised 120 specimens of breast infiltrating ductal carcinoma (IDC). Paraffin blocks were obtained from the archival material of the Department of Pathology at the Faculty of Medicine, Menoufia University Hospital, covering the period from January 2018 to December 2020. All selected cases represented IDC that had undergone either mastectomy or conservative breast surgery. Cases subjected to neo-adjuvant therapy were excluded from the study.

Ethical Considerations

The study received approval from the institutional ethics committee in compliance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975 (revised in 2000) (IRB: 7/2020 PATH17).

Clinicopathological Evaluation

Data were gathered from patients' files and through the re-evaluation of Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) stained sections. Grading followed the Elston/Nottingham modification of the Bloom/Richardson system (11, 12). Staging was determined according to the TNM staging system, based on the 8th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) (13). The Nottingham prognostic index (NPI) was calculated (14).

Using low power magnification (100x), the amount of stromal tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) was categorized as low, intermediate, or high (15). Lymphovascular invasion was assessed (16). Mitotic and apoptotic figures were tallied in ten randomly selected high-power fields (HPFs) (400x), corresponding to at least 1000 malignant cells (17, 18). Molecular classification was performed following staining of all cases with ER, PR, Her2neu, and Ki-67 (19-22).

Tissue Microarray Blocks

All mastectomy cases included in the study were utilized to construct 14 duplicate-core tissue microarray (TMA) blocks using a manual tissue microarrayer (Breecher instrument Manual Microarray, Wisconsin, USA).

Immunohistochemistry

The immunostaining technique employed utilized the streptavidin-biotin amplified system. The primary antibodies included ready-to-use IgG Rabbit monoclonal anti-RCC2 antibody (Chongqing Biospes Co., LTD, China, Catalog Number: YPA1680), anti-Rac1 antibody (Chongqing Biospes Co., LTD, China, Catalog Number: YPA2224), and anti-p53 antibody (Biocare Medical, USA, Catalog Number: IP 298 G10). Antigen retrieval was conducted by boiling the tissue sections in EDTA for all three antibodies. Human spleen, human prostatic tissue, and p53-positive breast cancer tissues were employed as positive control tissues for RCC2, Rac1, and p53, respectively. Sections stained without the primary antibody were used as negative controls.

Immunohistochemical Staining Interpretation

Positive expression of RCC2, Rac1, and p53 was identified through the presence of brownish nuclear staining (for RCC2 and p53) and cytoplasmic ± nuclear staining for Rac1 (23-25).

The percentage of stained invasive tumor cells was estimated, and staining intensity in tumor epithelial cells was categorized as mild, moderate, or strong. The H-Score was calculated using the formula:

H-Score = (1 × % of mildly stained cells) + (2 × % of moderately stained cells) + (3 × % of strongly stained cells) (23, 26).

Response to Treatment and Survival

Patients received treatment and follow-up care at the Clinical Oncology and Nuclear Medicine department, Faculty of Medicine, Menoufia University. Data collected from patient files included family history, comorbidities, metastatic sites, response to treatment, progression-free survival, and overall survival. Response to treatment was evaluated following the RECIST guideline, version 1.1 (27).

Statistical Analysis

The collected data underwent analysis using a personal computer equipped with the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 22 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA). Qualitative data were presented in numbers and percentages, while quantitative data were characterized using the range, median, interquartile range (IQR), mean, and standard deviation (SD). Employed statistical tests included the chi-square (χ2), Fisher's exact, Student's t-test, ANOVA, Mann-Whitney U, Kruskal-Wallis, McNemar, and marginal homogeneity test. Pearson's correlation coefficient was utilized to gauge the linear correlation between two continuous variables.

Progression-free survival (PFS) was calculated in months from the date of diagnosis to the time of disease progression (either local recurrence or distant metastasis). Overall survival (OS) was determined in months from the date of diagnosis to the last follow-up visit or death. Kaplan-Meier survival curves and Hazard function curves and their 95% confidence interval (CI) were constructed for survival analysis. A P-value less than 0.05 and 0.01 were considered statistically significant and highly significant, respectively (28).

Results

Clinicopathological Data of the Studied Cases

The clinical and pathologic data of studied cases are shown in Table 1

Table 1.

Clinicopathological data of the studied IDC cases (n = 120)

For statistical analysis, grades were categorized into low (grades 1 & and 2) and high (grade 3). Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) were grouped into low TILs (low and intermediate) and high TILs (high group). The Her2neu enriched subtype was excluded from statistical comparisons due to this group's small number of cases.

Expression of RCC2, Rac1 and P53 in the Studied Cases

The results of immunostaining for RCC2, Rac1, and p53, including expression (negative/positive), percentage, and intensity, are presented in Table 2 (Figures 1, 2, 3).

Table 2.

Expression of RCC2, Rac1 and P53 in the studied IDC cases

Fig. 1.

Infiltrating ductal carcinoma showing (A) strong nuclear expression of RCC2 (IHC x200), (B) moderate nuclear expression of RCC2 (IHC x200), (C) mild nuclear expression of RCC2 (IHC x200), (D) negative expression of RCC2 (IHC x200).

Fig. 2.

Infiltrating ductal carcinoma showing (A) strong nuclear ± cytoplasmic expression of Rac1 (IHC x40), (B) strong nuclear ± cytoplasmic expression of Rac1 (IHC x100), (C) moderate nuclear ± cytoplasmic expression of Rac1 (IHC x200), (D) mild nuclear ± cytoplasmic expression of Rac1 (IHC x200).

Fig. 3.

Infiltrating ductal carcinoma showing (A) strong nuclear expression of P53 (IHC x100), (B) moderate nuclear expression of P53 (IHC x100), (C) mild nuclear expression of P53 (IHC x100), (D) negative expression of P53 (IHC x200).

Given the widespread expression of RCC2 in nearly all studied cases (116/120), the cases were stratified into low and high-expression groups based on the median of the H-score expression.

The studied cases were categorized into low and high Rac1 expression groups according to the median of the H-score expression. Regarding p53 expression, the cases were grouped into mild (mild + moderate) versus strong intensity (strong) categories.

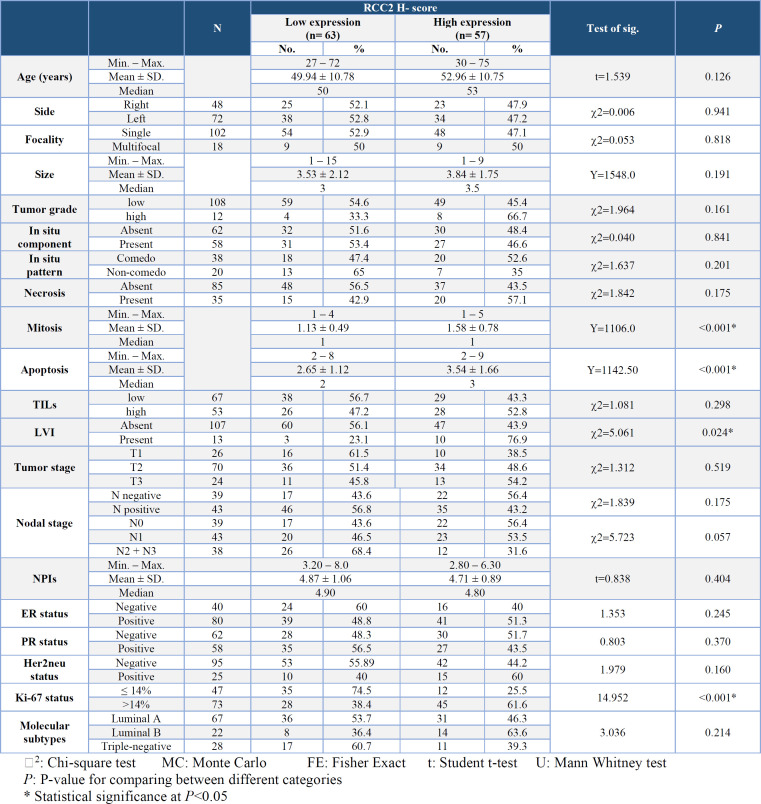

Association of RCC2 Expression with the Clinicopathological Parameters

A highly significant association was observed between high expression of RCC2 and frequent mitoses (P≤ 0.001), a high apoptotic count (P≤0.001), and a high Ki-67 status (P≤0.001). Additionally, a significant association was noted between the high expression of RCC2 and the presence of LVI (P=0.024) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Relation between RCC2 low/high expression and the clinicopathological parameters in all the studied breast IDC cases (n= 120)

Furthermore, a significant association was found between a higher percentage of RCC2 expression and positive Her2neu status (P=0.012) (Figure 4A). Molecular subtypes of IDC exhibited a significant association with RCC2 expression percentage (P= 0.012), with post hoc testing revealing that luminal B cases were associated with the highest median percentage of RCC2 expression (Figure 4B).

Fig. 4.

Infiltrating ductal carcinoma with Her2neu positive status (A) and luminal B subtype (B) showing a significantly higher RCC2 expression. Large tumor size (C) shows a significant association with strong RCC2. Positive correlation between p53 percent and apoptosis (D) Significant relation between positive PR and low p53 expression (E) Strong p53 intensity is associated with N0 and N1 nodal stage (F)

Concerning RCC2 intensity of expression, a significant association was observed between larger tumor size and strong RCC2 intensity of expression (P=0.010) (Figure 4C).

Association of Rac1 Expression with the Clinicopathological Parameters

High Rac1 expression demonstrated a highly significant association with a high Ki-67 status (P≤0.001) and molecular subtypes (P=0.009). Post hoc analysis revealed that the luminal B IDC group was significantly associated with high Rac1 expression. Additionally, a significant association was observed between high expression of Rac1 and frequent apoptosis (P=0.019), the presence of LVI (P=0.021), positive ER (P=0.028), positive PR (P=0.030), and positive Her2neu (P=0.016) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Relationship between Rac1 as (low/high expression) and the clinicopathological parameters in the studied breast IDC cases (n=120)

Association of P53 Expression with the Clinicopathological Parameters

A highly significant association was observed between positive p53 expression and large tumor size (P=0.009), high TILs (P = 0.008), and high Ki-67 status (P=0.001) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Relationship between P53 expression and the clinicopathological parameters in all studied breast IDC cases (n= 120)

Furthermore, a significant positive linear correlation was identified between p53 percentage and apoptotic count (P=0.013). Conversely, a significant inverse association was noted between p53 percentage and PR status (P=0.041) (Figure 4D & E). Additionally, Figure 4F illustrates a highly significant association between mild p53 intensity and an advanced nodal stage (N2+N3) (P=0.009).

Relationship Between RCC2, Rac1 and P53

Regarding the association between RCC2, Rac1, and P53 in the studied cases, a highly significant direct correlation was evident between each immunohistochemical marker in this study and the other two markers (Figure 5).

Fig. 5.

A highly significant direct linear correlation between expression of (A) RCC2 and Rac1 (P<0.001, r=0.424), (B) RCC2 and p53 (P=<0.001, r=0.315), and (C) Rac1 and p53 (P=0.006, r=0.332).

Survival

Patients received treatment and follow-up care at the Clinical Oncology and Nuclear Medicine department, Faculty of Medicine, Menoufia University. Survival data collected from patient files were available for 82 cases in the study cohort.

Overall survival time, calculated from the date of diagnosis to the date of death or last follow-up, ranged between 11 and 52 months, with a mean ± SD of 34.93±10.60 and a median of 37 months. Seven cases (8.5%) deceased during the follow-up period, with a median of 37 weeks. Progression-free survival, calculated from the date of diagnosis to the date of progression, ranged between 6 and 52 months, with a mean ± SD of 31.87±13.37 and a median of 35 months.

Twenty-three cases (28%) had a positive family history of breast cancer. Thirteen cases (15.9%) showed metastasis to distant organs. Regarding comorbidities, thirteen cases (15.9%) had hypertension, seven (8.5%) had diabetes mellitus, six (7.3%) had hepatitis C infection, four (4.9%) had cardiac complications, and four (4.9%) had both diabetes mellitus and hypertension.

Monitoring the response to treatment revealed that 25 cases had gross disease during treatment. Among them, thirteen cases (52%) showed progressive disease (PD), nine (36%) showed partial response (PR), two (8%) showed stationary disease (SD), and one (4%) showed complete response (CR). For statistical purposes, cases were divided into PD and non-PD (PR+SD+CR) groups.

Association of Treatment Response with the Clinicopathological Parameters, Including Immunohistochemical Markers (n = 25)

Progressive disease response exhibited a highly significant association with the presence of a low number of TILs (P=0.009), advanced tumor stage (T3) (P=0.002), and metastasis to distant organs (P≤0.001). Additionally, there was a significant association between progressive disease response and larger tumor size (P =0.011). Results from Rcc2, Rac1, and p53 immunostaining indicated a non-significant association with the type of patients' response to treatment.

Association of the Metastatic Status and the Clinicopathological Parameters Including Immunohistochemical Markers (n= 82)

Patients with distant metastasis significantly exhibited larger tumor size (P=0.003), a higher Nottingham Prognostic Index (NPI) (P=0.007), positive Her2neu status (P=0.023), and progressive disease with therapy (P<0.001). Consequently, they experienced shorter progression-free survival (PFS), shorter overall survival (OS) (P<0.001), and higher mortality rates (P<0.001). Results from RCC2, Rac1, and p53 immunostaining showed a non-significant association with the metastatic status of the studied cases.

Association of the Progression-free Survival and the Clinicopathological Parameters Including Immunostaining Results (n= 82)

A highly significant association was observed between the shorter progression-free survival (PFS) and advanced tumor stage (T3) (P=0.001), the presence of metastasis to distant organs (P<0.001), and progressive disease in response to therapy (P<0.001). Additionally, shorter PFS exhibited a significant association with positive Her2neu status (P=0.011) and the Luminal B molecular subtype (P=0.023) (Figure 6). Multivariate analysis revealed that the presence of metastasis to distant organs was the most independent factor affecting PFS (P=0.001) (Table 6). Results from RCC2, Rac1, and p53 immunostaining showed a non-significant association with PFS survival.

Fig. 6.

Short progression-free survival is associated with the advanced tumor stage (T3) (P=0.001) (A) presence of metastasis to distant organs (P<0.001) (B) progressive disease (P<0.001) (C) positive Her2neu status (P=0.011) (D) Luminal B cases (P=0.023) (E)

Table 6.

Multivariate COX regression analysis for the parameters affecting progression-free survival

| p | HR (LL – UL 95%C.I) | |

|---|---|---|

| Tumor stage (T3) | 0.203 | 0.308(0.050 – 1.892) |

| Her2neu status | 0.308 | 2.571(0.418 – 15.825) |

| Molecular subtypes(Luminal A+ B) | 0.724 | 0.714(0.110 – 4.631) |

| Metastatic status to distant organs | 0.001* | 49.866(4.653 – 534.421) |

| Response to treatment | – | – |

HR: Hazard ratio C.I: Confidence interval

LL: Lower limit UL: Upper Limit *Statistical significance at P≤ 0.05

Results of RCC2, Rac1, and p53 immunostaining showed a non-significant relationship to PFS survival.

Survival outcomes by the clinicopathological parameters including immunostaining results (n= 82)

Significantly shorter overall survival (OS) was observed in patients presenting with multifocal tumors (P=0.017), advanced tumor stage (T3) (P=0.010), and the Luminal B molecular subtype (P=0.015). Moreover, a highly significant shorter OS was noted in patients with progressive disease response to treatment (P=0.003), positive Her2neu status (P=0.008), and the presence of metastasis to distant organs (P<0.001) (Figure 7). However, Multivariate analysis revealed that none of the aforementioned factors could be considered as independent factors affecting overall survival (Table 7). Results from RCC2, Rac1, and p53 immunostaining showed a non-significant association with overall survival.

Fig. 7.

Shorter overall survival in the patients presented by (A) multifocal tumors (P=0.017), (B) advanced tumor stage (T3) (P=0.010), (C) Luminal B molecular subtype (P=0.015), (D) progressive disease response to treatment (P=0.003), (E) positive Her2neu status (P=0.008) and (F) presence of metastasis to distant organs (P<0.001).

Table 7.

Multivariate COX regression analysis for the parameters affecting overall survival

| p | HR (LL – UL 95% C.I) | |

|---|---|---|

| Focality | 0.172 | 5.353(0.483 – 59.367) |

| Tumor stage (T3) | 0.843 | 0.806(0.095 – 6.842) |

| Her2neu status | 0.634 | 1.871(0.142 – 24.607)1 |

| Luminal B | 0.442 | 0.268(0.009 – 7.733) |

| Metastatic status to distant organs | 0.953 | – |

| Response to treatment | – | – |

HR: Hazard ratio

C.I: Confidence interval LL: Lower limit UL: Upper Limit

*: Statistically significant at P≤ 0.05

Discussion

Metastasis often leads to unfavorable outcomes and poor prognoses in cancer patients. Molecular markers and adhesive proteins play crucial roles in regulating metastasis through intricate signaling networks within different cell types. Identifying markers that govern metastasis is paramount for understanding and controlling tumor behavior. In colon cancer, Song, et al. demonstrated the significance of p53 and RCC2 signaling in inhibiting random cell migration and metastasis (10). They elucidated that p53 suppresses metastasis by inducing RCC2-mediated inactivation of Rac1. In breast cancer, the expression and correlation of p53/RCC2/Rac1 proteins warrant attention.

In our study, RCC2 exhibited positive expression in 116 cases (96.7%), with Strong intensity detected in 52.6% of cases and high expression demonstrated in 47.5%. Chen, et al. reported increased RCC2 expression in breast cancer tissue (4). Additionally, Wang, et al. documented elevated RCC2 expression in ER-positive breast cancer (26). Elevated RCC2 expression has also been observed in other tumors such as colorectal cancer (29), gastric cancer (30), and lung cancer (31), suggesting an association between RCC2 and cancer, including breast cancer.

In our cohort, a strong and high RCC2 expression showed a significant association with the clinicopathological parameters of poor prognostic significance, including large tumor size, frequent mitoses, high Ki-67 status, presence of LVI, and positive Her2neu. Chen, et al. corroborated these findings in breast cancer, reporting a significant decrease in tumor size upon silencing of RCC2, which also inhibited tumor progression and metastatic potential. They suggested that RCC2 promotes the proliferation and migration of breast cancer cells (4). Additionally, studies on other cancers confirmed a poor prognostic significance of RCC2 expression and demonstrated its role in cell division, cell cycle progression, cell migration, metastasis, and cancer promotion (30, 31). Therefore, RCC2 could play a pivotal role in breast cancer behavior.

Rac1 showed positive expression in all 120 cases (100%) in our study, with 56 cases (46.7%) exhibiting high expression. Previous studies have confirmed Rac1 expression in breast cancer and suggested its involvement in the cancer progression (32, 33).

In our work, high Rac1 expression showed a significant association with poor prognostic parameters such as high Ki-67 status, presence of LVI, and positive Her2neu. Yamaguchi, et al. found that Rac1 expression was associated with poor prognostic factors such as a high Ki-67 proliferation index (34). Moreover, significant associations of Rac1 with poor prognostic parameters were demonstrated in other types of cancers including renal cell carcinoma (35), gastric cancer (36), and hepatocellular carcinoma (37). The significant association between high Rac1 expression and hormone receptors including ER status and Her2neu status in our study has been previously investigated, suggesting that a Rac1 inhibitor may be a promising treatment in endocrine-resistant breast cancer (38, 39). Taken together, Rac1 might serve as a promising therapeutic target in breast cancer.

In our study, high RCC2 and Rac1 expression were significantly associated with frequent apoptosis. Previous findings indicated that increased RCC2 led to attenuation of apoptosis through blocking Rac1-initiated apoptosis. However, Rac1 was known to have a complex role in apoptosis—It may function as either a pro-apoptotic or anti-apoptotic protein, depending on the cellular context and inducers of apoptosis. Thus, the association between RCC2 and Rac1 concerning apoptosis depends on more complex factors that ultimately influence the response of tumor cells to drug-induced apoptosis (40).

P53 showed a positive expression in 33 cases (27.5%) in our study, with strong expression detected in 60.6% of positive cases. Since mutant p53 protein tends to accumulate and stabilize in the tumor cell nuclei, its detection by immunohistochemistry is interpreted to indicate the presence of a mutation (41). Despite the confirmed loss of function of p53 in breast carcinogenesis, mutations in the gene occur at a significantly lower frequency than in other common solid tumors. Several studies have detected mutant p53 protein overexpression in breast cancer at similar low percentages (16.3-30%) (42-44).

In our cases, there was a highly significant association between positive p53 expression and adverse prognostic factors such as large tumor size and high Ki-67 status. Additionally, p53 expression percent showed a significant positive linear correlation with frequent apoptosis, and mild p53 intensity showed a significant relation with advanced nodal stage (N2+N3). Previous studies have declared the association of p53 with poor prognostic parameters including high tumor grade, high Ki-67 proliferation index, Her2neu, and triple-negative expression (41, 45-47). However, it was reported that the p53 mutation did not impact the outcome of breast cancer (48). These contradictory results might be explained by the fact that p53 mutant subtypes differ and indicate a debated value of p53 protein overexpression in breast cancer prognosis. Dobes, et al. declared that the TP53 mutation type affected the prognostic significance of breast carcinoma, with nonsense mutations being the most important for determining breast cancer patients' outcomes (49). Thus, the role of the p53 protein in breast cancer is not established, and its clinical application is still debated.

There was a highly significant direct correlation between each immunohistochemical marker in this study and the other two markers. RCC2 percent positively correlated with Rac1 percent, suggesting that RCC2 might regulate Rac1 activity in breast IDC. Previous studies suggested that RCC2 acts as a Rac1 regulator, promoting mitosis and cell division (50). Inconsistent results regarding the mechanism of regulation were suggested (49, 50). RCC2 binds to the switch region, guanine-nucleotide-exchange factors (GEF), of Rac1 and controls its on/off activity (50). Additionally, RNA interference (RNAi)-mediated depletion of RCC2 promoted the activation of Rac1 (51), suggesting its inhibitory role. Another possible mechanism of regulation of RCC2 and Rac1 was that Coro1C might affect Rac1 localization by interaction with the RCC2–Rac1 complex and release Rac1 from RCC2 for activation. It was also considered that inhibition of Rac1 in RCC2-null cells inhibited cell metastasis (50).

In this study, a highly significant direct correlation between RCC2 percent and p53 percent was detected. In agreement with these results, Song et al. found that RCC2 was transcriptionally activated by P53 through activating the promoter of RCC2 in colon cancer, and P53 deficiency suppressed RCC2 expression (10). So, P53 could regulate RCC2 activity in breast IDC.

There was a significant positive correlation between P53 percent and Rac1 percent in the studied cases. Previous studies had conflicting results suggesting multiple pathways of interaction (10, 52, 53). This was confirmed when Rac1 was independently activated in P53-deficient B- and T-cell lines (53). Thus, the mechanism that accounts for P53-Rac1 interactions is still incompletely understood. In contrast to our results, Song et al. study on colorectal cancer found that RCC2 or p53 deficiency triggers Rac1 activation, and they also established that p53 and RCC2 deficiency promotes random cell migration and loss of RCC2 facilitated tumor metastasis in vivo. In addition, they concluded that the RCC2-P53-Rac1 signaling pathway was important for the suppression of tumor metastasis in colon cancer (10). Considering these conflicting results, the RCC2-P53-Rac1 signaling pathway might have a role in breast cancer; however, further investigations are required.

Survival analysis revealed that progressive disease response was significantly associated with the presence of a low number of TILs, larger tumor size, advanced tumor stage, and metastasis to distant organs. In addition, patients with distant metastasis significantly had large tumor size, higher NPI, positive Her2neu status, and progressive disease with therapy. Moreover, patients with shorter PFR and Shorter overall survival significantly experienced more metastasis to distant organs, positive Her2neu status, and Luminal B molecular subtype. Multivariate analysis revealed that the presence of metastasis to distant organs was the most independent factor affecting PFS. These expected prognostic variables were previously confirmed in other studies (54-56).

In this study, RCC2, Rac1, and P53 showed a non-significant association with overall survival, Progression-free survival, and response to treatment. In contrast to these results, Overexpression of RCC2 has been associated with shorter overall survival, poor prognosis, and recurrence survival rates in breast carcinoma (4) and lung cancer (31). These inconsistent results could be due to different sample sizes and different tumor types. These results might suggest that RCC2 played different functions in different tumors which may need further exploration.

The prognostic significance of Rac1 in breast carcinoma was previously investigated and showed inconsistent results. Takagi et al. detected similar results (57) while Yamaguchi et al. found a significant correlation between Rac1-GTP status and increased recurrence and breast cancer-specific mortality. In addition, multivariate analyses considered Rac1-GTP as an independent worse prognostic factor for both disease-free and breast cancer-specific survival. Rac1-GTP correlated with a worse prognosis in the patients who had received adjuvant chemotherapy or endocrine therapy (34). Different inconsistent results were detected in other studies (23, 57). This could be explained by the fact that the expression of Rac1 either by immunohistochemistry or protein level did not indicate its activity, and this could be the cause for these inconsistent results.

Regarding p53, contrary to our results, it was found that the presence of mutant p53 was associated with both adverse breast cancer-specific and overall survival. However, it was specific for certain molecular types, such as HER2-enriched and luminal B (58). These disparities could be explained by the fact that the different p53 mutations have different consequences in breast cancer pathogenesis, and thus different impacts on patient outcome and response to therapy could be detected.

Conclusion

The high expression of RCC2, Rac1, and P53 in breast cancer might indicate their role in its behavior. The association of RCC2 and Rac1 with poor prognostic clinicopathological factors could help in the prediction of tumor progression, and thus targeted therapy could be helpful in the treatment of breast cancer. The RCC2-P53-Rac1 signaling pathway might have a role in breast cancer; however, further investigations on a larger scale are required.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Ethics Declarations

The study had been approved by the Menoufia University Faculty of Medicine Research Ethics Committee.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare no conflicting interests.

References

- 1.Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209–49. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ibrahim AS, Khaled HM, Mikhail NN, Baraka H, Kamel H. Cancer incidence in Egypt: results of the national population-based cancer registry program. J Cancer Epidemiol. 2014:2014. doi: 10.1155/2014/437971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clark BZ, Onisko A, Assylbekova B, Li X, Bhargava R, Dabbs DJ. Breast cancer global tumor biomarkers: a quality assurance study of intratumoral heterogeneity. Mod Pathol. 2019;32(3):354–66. doi: 10.1038/s41379-018-0153-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen Z, Wu W, Huang Y, Xie L, Li Y, Chen H, Li W, Yin D, Hu K. RCC2 promotes breast cancer progression through regulation of Wnt signaling and inducing EMT. J Cancer. 2019;10(27) doi: 10.7150/jca.36430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liang J, Oyang L, Rao S, Han Y, Luo X, Yi P, Lin J, Xia L, Hu J, Tan S, Tang L. Rac1, a potential target for tumor therapy. Front Oncol. 2021 doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.674426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rao J, Zhou ZH, Yang J, Shi YU, Xu SL, Wang B, Ping YF, Chen LU, Cui YH, Zhang X, Wu F. Semaphorin-3F suppresses the stemness of colorectal cancer cells by inactivating Rac1. Cancer Lett. 2015;358(1):76–84. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2014.12.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cardama GA, Alonso DF, González N, Maggio J, Gomez DE, Rolfo C, Menna PL. Relevance of small GTPase Rac1 pathway in drug and radio-resistance mechanisms: Opportunities in cancer therapeutics. Crit Rev Oncol/Hematol. 2018;124:29–36. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2018.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Powell E, Piwnica-Worms D, Piwnica-Worms H. Contribution of p53 to Metastasis. Cancer Discovery. 2014;4(4):405–14. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-13-0136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mihara M, Erster S, Zaika A, Petrenko O, Chittenden T, Pancoska P, Moll UM. p53 has a direct apoptogenic role at the mitochondria. Mol Cell. 2003;11(3):577–90. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00050-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Song C, Liang L, Jin Y, Li Y, Liu Y, Guo L, Wu C, Yun CH, Yin Y. RCC2 is a novel p53 target in suppressing metastasis. Oncogene. 2018;37(1):8–17. doi: 10.1038/onc.2017.306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bloom HJ, Richardson W. Histological grading and prognosis in breast cancer: a study of 1409 cases of which 359 have been followed for 15 years. Br J Cancer. 1957;11(3):359. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1957.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elston CW, Ellis IO. Pathological prognostic factors in breast cancer I The value of histological grade in breast cancer: experience from a large study with long‐term follow‐up. Histopathology. 1991;19(5):403–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1991.tb00229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Giuliano AE, Edge SB, Hortobagyi GN. of the AJCC cancer staging manual: breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2018;25:1783–5. doi: 10.1245/s10434-018-6486-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fong Y, Evans J, Brook D, Kenkre J, Jarvis P, Gower-Thomas K. The Nottingham Prognostic Index: five-and ten-year data for all-cause survival within a screened population. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2015;97(2):137–9. doi: 10.1308/003588414X14055925060514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zgura A, Galesa L, Bratila E, Anghel R. Relationship between tumor infiltrating lymphocytes and progression in breast cancer. Maedica. 2018;13(4):317. doi: 10.26574/maedica.2018.13.4.317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rakha EA, Martin S, Lee AH, Morgan D, Pharoah PD, Hodi Z, MacMillan D, Ellis IO. The prognostic significance of lymphovascular invasion in invasive breast carcinoma. Cancer. 2012;118(15):3670–80. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Jong JS, van Diest PJ, Baak JP. Number of apoptotic cells as a prognostic marker in invasive breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2000;82(2):368–73. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.1999.0928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meyer JS, Cosatto E, Graf HP. Mitotic index of invasive breast carcinoma: achieving clinically meaningful precision and evaluating tertial cutoffs. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133(11):1826–33. doi: 10.5858/133.11.1826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hammond ME, Hayes DF, Dowsett M, Allred DC, Hagerty KL, Badve S, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists guideline recommendations for immunohistochemical testing of estrogen and progesterone receptors in breast cancer. Archives of pathology & laboratory medicine. 2010;134(6):907–22. doi: 10.5858/134.6.907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goldhirsch A, Wood WC, Coates AS, Gelber RD, Thürlimann B, Senn HJ. Strategies for subtypes--dealing with the diversity of breast cancer: highlights of the St. Gallen International Expert Consensus on the Primary Therapy of Early Breast Cancer. 2011;22(8):1736–47. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Suciu C, Muresan A, Cornea R, Suciu O, Dema A, Raica M. Semi-automated evaluation of Ki-67 index in invasive ductal carcinoma of the breast. Oncology letters. 2014;7(1):107–14. doi: 10.3892/ol.2013.1654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wolff AC, Hammond MEH, Allison KH, Harvey BE, Mangu PB, Bartlett JMS, et al. Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2 Testing in Breast Cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists Clinical Practice Guideline Focused Update. Archives of pathology & laboratory medicine. 2018;142(11):1364–82. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2018-0902-SA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu B, Xiong J, Liu G, Wu J, Wen L, Zhang Q, et al. High expression of Rac1 is correlated with partial reversed cell polarity and poor prognosis in invasive ductal carcinoma of the breast. Tumor Biology. 2017;39(7):1010428317710908. doi: 10.1177/1010428317710908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Melling N, Norrenbrock S, Kluth M, Simon R, HubeMagg C, Steurer S, et al. p53 overexpression is a prognosticator of poor outcome in esophageal cancer. Oncology letters. 2019;17(4):3826–34. doi: 10.3892/ol.2019.10020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yao X, Li L, Piao L, Zhang G, Huang X, Liang Z. Regulator of Chromosome Condensation 2 Expression Profile in Hepatocellular Carcinoma and Its Potential Link to Clinical Parameters. Int J Hum Genet. 2020;20(3):155–60. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang W, Xu B, Zhang Z, Fang K, Chang X. RCC2 expression stimulates ER-positive breast tumorigenesis. J Oncol. 2020:2020. doi: 10.1155/2020/5619462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R, Dancey J, Arbuck S, Gwyther S, Mooney M, Rubinstein L. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1 1) Eur J Cancer. 2009;45(2):228–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Siegel AF. Chapter 10—Hypothesis testing: Deciding between reality and coincidence. Practical business statistics; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bruun J, Kolberg M, Ahlquist TC, Røyrvik EC, Nome T, Leithe E, Lind GE, Merok MA, Rognum TO, Bjørkøy G, Johansen T. Regulator of chromosome condensation 2 identifies high-risk patients within both major phenotypes of colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21(16):3759–70. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-3294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li X, Kang K, Peng Y, Shen L, Shen L, Zhou Y. Comprehensive analysis of the expression profile and clinical implications of regulator of chromosome condensation 2 in pan-cancers. Aging (Albany NY) 2022;14(22):9221. doi: 10.18632/aging.204403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pang B, Wu N, Guan R, Pang L, Li X, Li S, Tang L, Guo Y, Chen J, Sun D, Sun H. Overexpression of RCC2 enhances cell motility and promotes tumor metastasis in lung adenocarcinoma by inducing epithelial–mesenchymal transition. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23(18):5598–610. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-2909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mira JP, Benard V, Groffen J, Sanders LC, Knaus UG. Endogenous, hyperactive Rac3 controls proliferation of breast cancer cells by a p21-activated kinase-dependent pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2000;97(1):185–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.1.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ma N, Xu E, Luo Q, Song G. Rac1: A Regulator of Cell Migration and a Potential Target for Cancer Therapy. Molecules. 2023;28(7):2976. doi: 10.3390/molecules28072976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yamaguchi M, Takagi K, Sato A, Miki Y, Miyashita M, Sasano H, Suzuki T. Rac1 activation in human breast carcinoma as a prognostic factor associated with therapeutic resistance. Breast Cancer. 2020;27:919–28. doi: 10.1007/s12282-020-01091-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shan G, Tang T, Qian H, Xia Y. Expression of Tiam1 and Rac1 proteins in renal cell carcinoma and its clinical-pathological features. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2017;10(11):11114. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wu YJ, Tang Y, Li ZF, Li Z, Zhao Y, Wu ZJ, Su Q. Expression and significance of R ac1, P ak1 and R ock1 in gastric carcinoma. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2014;10(2):e33–9. doi: 10.1111/ajco.12052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang W, Lv S, Liu X, Liu H, Yang W, Hu F. Up-regulation of Tiam1 and Rac1 correlates with poor prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2010;40(11):1053–9. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyq086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lin Y, Fu F, Lv J, Wang M, Li Y, Zhang J, Wang C. Identification of potential key genes for HER-2 positive breast cancer based on bioinformatics analysis. Medicine. 2020;99:1. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000018445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sun J, Gaidosh G, Xu Y, Mookhtiar A, Man N, Cingaram PR, Blumenthal E, Shiekhattar R, Goka ET, Nimer SD, Lippman ME. RAC1 plays an essential role in estrogen receptor alpha function in breast cancer cells. Oncogene. 2021;40(40):5950–62. doi: 10.1038/s41388-021-01985-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wu N, Ren D, Li S, Ma W, Hu S, Jin Y, Xiao S. RCC2 over-expression in tumor cells alters apoptosis and drug sensitivity by regulating Rac1 activation. BMC Cancer. 2018;18(1):1–1. doi: 10.1186/s12885-017-3908-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lipponen P, Ji H, Aaltomaa S, Syrjänen S, Syrjänen K. p53 protein expression in breast cancer as related to histopathological characteristics and prognosis. Int J Cancer Res. 1993;55(1):51–6. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910550110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Olivier M, Langer√∏ d A, Carrieri P, Bergh J, Klaar S, Eyfjord J, Theillet C, Rodriguez C, Lidereau R, Bi√® che I, Varley J. The clinical value of somatic TP53 gene mutations in 1,794 patients with breast cancer. Clinical cancer research: Am J Cancer Res. 2006;12(4):1157–67. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Petitjean A, Mathe E, Kato S, Ishioka C, Tavtigian SV, Hainaut P, Olivier M. Impact of mutant p53 functional properties on TP53 mutation patterns and tumor phenotype: lessons from recent developments in the IARC TP53 database. Hum Mutat. 2007;28(6):622–9. doi: 10.1002/humu.20495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Langerød A, Zhao H, Borgan Ø, Nesland JM, Bukholm IR, Ikdahl T, Kåresen R, Børresen-Dale AL, Jeffrey SS. TP53 mutation status and gene expression profiles are powerful prognostic markers of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2007;9:1–6. doi: 10.1186/bcr1675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Overgaard J. TP53 mutation is an independent prognostic marker for poor outcome in both node-negative and node-positive breast cancer. Acta Oncol. 2000;39(3):327–33. doi: 10.1080/028418600750013096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dookeran KA, Dignam JJ, Ferrer K, Sekosan M, McCaskill-Stevens W, Gehlert S. p53 as a marker of prognosis in African-American women with breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:1398–405. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0889-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rana MK, Rana AP, Khera U. Expression of p53 and p16 in Carcinoma Breast Tissue: Depicts Prognostic Significance or Coincidence. Cureus. 2021;13:11. doi: 10.7759/cureus.19395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Harris L, Fritsche H, Mennel R, Norton L, Ravdin P, Taube S, Somerfield MR, Hayes DF, Bast Jr RC. American Society of Clinical Oncology 2007 update of recommendations for the use of tumor markers in breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(33):5287–312. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.2364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dobes P, Podhorec J, Coufal O, Jureckova A, Petrakova K, Vojtesek B, Hrstka R. Influence of mutation type on prognostic and predictive values of TP53 status in primary breast cancer patients. Oncol Rep. 2014;32(4):1695–702. doi: 10.3892/or.2014.3346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Williamson RC, Cowell CA, Hammond CL, Bergen DJ, Roper JA, Feng Y, Rendall TC, Race PR, Bass MD. Coronin-1C and RCC2 guide mesenchymal migration by trafficking Rac1 and controlling GEF exposure. J Cell Sci. 2014;127(19):4292–307. doi: 10.1242/jcs.154864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Humphries JD, Byron A, Bass MD, Craig SE, Pinney JW, Knight D, Humphries MJ. Proteomic analysis of integrin-associated complexes identifies RCC2 as a dual regulator of Rac1 and Arf6. Sci Signal. 2009;2(87):ra51. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Guo F, Gao Y, Wang L, Zheng Y. p19Arf-p53 tumor suppressor pathway regulates cell motility by suppression of phosphoinositide 3-kinase and Rac1 GTPase activities. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(16):14414–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300341200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bosco EE, Ni W, Wang L, Guo F, Johnson JF, Zheng Y. Rac1 targeting suppresses p53 deficiency–mediated lymphomagenesis. Blood, J Am Soc Hematol. 2010;115(16):3320–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-02-202440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Toikkanen S, Helin H, Isola J, Joensuu H. Prognostic significance of HER-2 oncoprotein expression in breast cancer: a 30-year follow-up. J Clin Oncol. 1992;10(7):1044–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1992.10.7.1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fitzgibbons PL, Page DL, Weaver D, Thor AD, Allred DC, Clark GM, Ruby SG, O'Malley F, Simpson JF, Connolly JL, Hayes DF. Prognostic factors in breast cancer: College of American Pathologists consensus statement 1999. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2000;124(7):966–78. doi: 10.5858/2000-124-0966-PFIBC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tazhibi M, Fayaz M, Mokarian F. Detection of prognostic factors in metastatic breast cancer. J Res Med Sci. 2013;18(4):283. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Takagi K, Miki Y, Onodera Y, Ishida T, Watanabe M, Sasano H, et al. ARHGAP15 in Human Breast Carcinoma: A Potent Tumor Suppressor Regulated by Androgens. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(3):804. doi: 10.3390/ijms19030804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tian Y, Xu L, He Y, Xu X, Li K, Ma Y, Gao Y, Wei D, Wei L. Knockdown of RAC1 and VASP gene expression inhibits breast cancer cell migration. Oncol Lett. 2018;16(2):2151–60. doi: 10.3892/ol.2018.8930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]