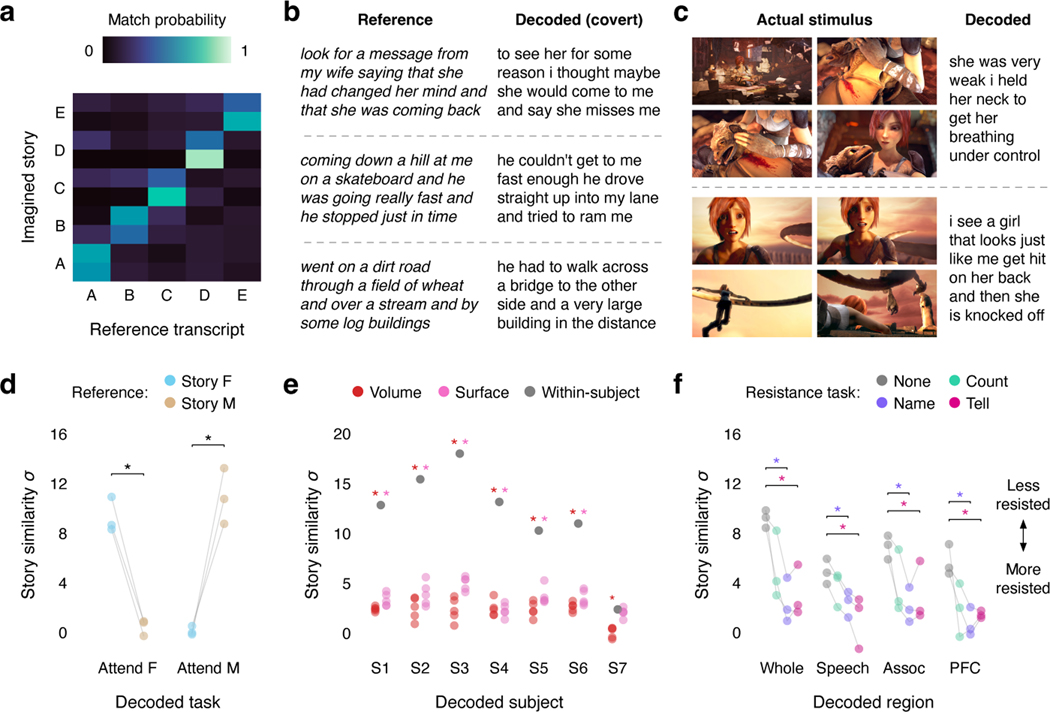

Fig. 3. Decoder applications and privacy implications.

(a) To test whether the language decoder can transfer to imagined speech, subjects were decoded while they imagined telling five 1-minute test stories twice. Decoder predictions were compared to reference transcripts that were separately recorded from the same subjects. Identification accuracy is shown for one subject. Each row corresponds to a scan, and the colors reflect the similarities between the decoder prediction and all five reference transcripts (100% identification accuracy). (b) Reference transcripts are shown alongside decoder predictions for three imagined stories for one subject. (c) To test whether the language decoder can transfer across modalities, subjects were decoded while they watched four silent short films. Decoder predictions were significantly related to the films (, one-sided nonparametric test). Frames from two scenes are shown alongside decoder predictions for one subject © copyright Blender Foundation | www.sintel.org48. (d) To test whether the decoder is modulated by attention, subjects attended to the female speaker or the male speaker in a multi-speaker stimulus. Decoder predictions were significantly more similar to the attended story than to the unattended story (* indicates across subjects, one-sided paired -test). Markers indicate individual subjects. (e) To test whether decoding can succeed without training data from a particular subject, decoders were trained on anatomically aligned brain responses from 5 sets of other subjects (indicated by markers). Cross-subject decoders performed barely above chance, and substantially worse than within-subject decoders (* indicates , two-sided -test), suggesting that within-subject training data is critical. (f) To test whether decoding can be consciously resisted, subjects silently performed three resistance tasks: counting, naming animals, and telling a different story. Decoding performance was compared to a passive listening task (* indicates across subjects, one-sided paired -test). Naming animals and telling a different story significantly lowered decoding performance in each cortical region, demonstrating that decoding can be resisted. Markers indicate individual subjects. Different experiments cannot be compared based on story decoding scores, which depend on stimulus length; see Extended Data Figure 5 for a comparison based on the fraction of significantly decoded time-points.