Abstract

This study investigated the effect of low-voltage electrostatic field on the flavor quality changes and generation pathways of refrigerated sturgeon caviar. Research has found that after storage for 3–6 weeks, the physicochemical properties of caviar in the LVEF treatment group are better than those in the control group. The results of two-dimensional gas chromatography-time-of-flight mass spectrometry showed that the contents of hexanal, nonanal, (E,Z)-2,6-nonadienal, (E)-2-octenal and 1-octene-3-one related to the characteristic flavor of caviar (sweet, fruity and green) increased significantly. The lipidomics results indicated that the effects of LVEF on caviar mainly involve glycerophospholipid metabolism, linoleic acid metabolism, and α-Linolenic acid metabolism. Methanophosphatidylcholine (15:0/18:1), phosphatidylcholine (18:0/20:5), and phosphatidylcholine (18,1e/22:6) were significantly correlated with odor formation. Therefore, low-voltage electrostatic field treatment preserved the quality and enhanced the flavor of sturgeon caviar. This study provided a new theoretical basis for the preservation of sturgeon caviar.

Keywords: Caviar, Low-voltage electrostatic field technique, Preservation, Flavor

Highlights

-

•

Low-voltage electrostatic field (LVEF) could regular the flavor of caviar.

-

•

Aldehyde compounds were the main substance of caviar with LVEF treatment.

-

•

Fifteen lipids (phospholipid) were the markers during refrigerate in LVFE.

-

•

The formation of C6-C9 was related to the phospholipid metabolic pathway.

1. Introduction

Caviar (sturgeon eggs) is a highly nutritious food, rich in unsaturated fatty acids and essential amino acids, which leads to popularity due to the nutritional and excellent flavor properties. (Brambilla et al., 2020; Xu et al., 2022). Recently, the production and export of sturgeon caviar from China has been gradually increasing with the international market share steadily ranking first. However, the single preservation method of sturgeon caviar is prone to protein hydrolysis and fat oxidation, leading to a decrease in product flavor and quality (Li et al., 2017). A study reported an increase in the total volatile base nitrogen (TVB-N) content of caviar after 8 d of storage at 4 °C. The rancid odor was attributed to carbonyl derivatives from protein hydrolysis as off-odor precursors (Jiang et al., 2022). In another study, lipid oxidation of caviar after 28 d of storage at 0 °C deepened with increasing storage time, leading to the production of volatile aldehydes and ketones and flavor deterioration (Al-Dalali et al., 2022; Ayşe et al., 2018). Therefore, caviar can be severe during storage, which limits deterioration to the development of the industry.

Currently, the main non-thermal preservation technologies used for caviar include microwave, radio frequency and ultra-high pressure. Non-thermal technology can extend the shelf life of food products without destroying the original taste and flavor. Al-Holy et al. (2004) found that treatment of caviar using radiofrequency reduced Listeria monocytogenes and facilitated the preservation of caviar. Fioretto et al. (2005) utilized an ultrahigh-pressure technique for caviar treatment, which reduced the content of Staphylococcus aureus and Salmonella enteritidis, thereby inhibiting its spoilage. Therefore, the use of non-thermal preservation techniques for caviar preservation has unique advantages and potentials.

Low-voltage electrostatic field (LVEF) is a new non-thermal preservation method. Its preservation mechanism mainly involves ionization produced by ionized mist and ozone. Negativeions inhibit the activity of enzymes in food and inhibit various biochemical reactions and physiological activities in biological systems. Ozone affects the permeability of cell membranes, alters enzyme activity, and thus extending the shelf life of food (Albertos et al., 2017), which has the advantages of single input, long-term efficacy, and absence of pollution. It is mainly used for thawing, freezing, and preserving food and represents a new technology with good application prospects. Zhang et al. (2023) found that LVEF treatment inhibited the production of spoilage bacteria and extended the shelf life of rhubarb fish by 3d. Xu, Liu, et al. (2022)), Xu, Lu, et al. (2022)) and Xu, Zhang, et al. (2022)) found that LVEF treatment strawberries delayed cell wall degradation and improved reactive oxygen metabolism during storage, prolonging the shelf life of strawberries. Yun et al. (2023) found that Mongolian milk treated with LVEF reduced the number of viable bacteria and shortened the freezing time by 5.2%, effectively improving the quality of the curd. LVEF appeared to be an effective strategy that could successfully extend the shelf life of food products. However, the application of LVEF treatment in caviar storage has rarely been reported. Thus, it is necessary to investigate the effect and mechanism of action of LVEF treatment on the quality stability of caviar during storage.

The objectives of the present study were: (1) to investigate the differences in quality, microstructure and flavor between LVEF treated caviar and traditionally refrigerated caviar; (2) to identification of potential phospholipid markers in LVEF treated caviar; (3) to elucidate the mechanism of caviar quality changes using flavoromics and lipidomics, and to provide theoretical basis and technical support for LVEF treated stored caviar.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Sample preparation

The raw material used in the experiments was caviar from Russian sturgeon (Acipenser gueldenstaedtii). sturgeon caviar was provided by Hangzhou Qiandao Lake Squid Dragon Technology Co., Ltd. The products were vacuum canned (30 g/can), and the cans were placed on ice and transported to the laboratory. The canned sturgeon caviar was put in an ordinary refrigerator at −4 °C and in a low-pressure electrostatic refrigerator for storage. The cans were opened regularly at intervals of 1 week for 6 weeks. After the samples were freeze-dried, they were put in a refrigerator at −60 °C for testing.

2.2. Extraction of myofibrillar protein

20 mL of distilled water heated to 4 °C was added to a 1 g sample after it had been crushed. Before the material was centrifuged at 4 °C for 15 min at 10,000 rpm, it was shook for 30 min. The silt was then given a 20 mL addition of Tris-HCl buffer A. After being shaken for 30 min, it was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 15 min at 4 °C. The sediment was then given 20 mL of Tris-HCl buffer B, which was added after 30 min of shaking, and centrifuged for 15 min at 10,000 rpm at 4 °C. The upper clear layer was a solution of myofibrillar proteins.

2.3. Determination of carbonyl content of myofibrillar protein

Protein carbonyl content was determined using a kit (Solarbio Biotechnology, Beijing, China). Take 1 mL of sample with 2 mL of mixed solution and 2 mL of 20% TCA mixed centrifugation (10,000 r/min, 5 min), then add 2 mL, 10 mmol/L of 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine, let stand at 4 degrees Celsius for 1 h, centrifugation at 12,000 r/min for 15 min, discard the supernatant, and then add 3 mL, 6 mol/L of guanidine hydrochloride to the precipitate (pH = 8.7), held at 37 degrees Celsius for 15 min, absorbance at 370 nm was recorded.

2.4. Determination of thiol content of myofibrillar protein

Protein thiol content was determined using a kit (Solarbio Biotechnology, Beijing, China). Salt-soluble protein was diluted to a concentration of 1 mg/mL in high-salt buffer. Then, a 1 mL sample was taken, and 200 μL Ellman's reagent was added with 3 mL Tris glycine buffer. For 1 h, the sample was allowed to react at room temperature. The absorbance was measured at 412 nm, and the active thiol content was estimated.

2.5. Determination of TVB-N content

Add 1 mL of boric acid solution and one drop of mixed indicator to the central hole of the diffusion dish. Take 1 mL of sample and add it to the outer well of the culture dish. The diffusion plate should be completely covered after adding 1 mL of saturated potassium carbonate solution. Place at 37 °C for two hours and titrate with standard hydrochloric acid titration solution (0.01 mol/L) until the solution turns purple red, which is the titration endpoint.

2.6. Determination of acid value

Firstly, a water bath at 90 °C was used to heat 100 mL of 95% ethanol and 1 mL of phenolphthalein indicator until the ethanol was just beginning to boil. Once a 1 mL sample had been added, it was vigorously shaken to create a suspension before being titrated with a standard potassium hydroxide solution (0.01 mol/L) until the solution became red, which served as the titration endpoint.

2.7. Determination of peroxide value

A 1 g sample was taken and mixed with 30 mL of a mixture of trichloromethane and glacial acetic acid (2:3, v/v). The sample was agitated, then 1 mL of a saturated potassium iodide solution was added. After 3 min of reaction time in the dark, 100 mL water and 1 mL starch indicator were added. The sample was titrated with a standard solution of sodium thiosulfate (0.01 mol/L) until the blue color disappeared, which marked the titration endpoint.

2.8. Determination of TBA value

Firstly, a 1 g crushed sample was allowed to react with a mixed solution of trichloroacetic acid and disodium ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (75:1, m/m) at 50 °C for 30 min. The solution was filtered, and the filtrate was allowed to react with an aqueous solution of TBA at 90 °C for 30 min and then cooled to room temperature. At 532 nm, the absorbance was measured.

2.9. Determination of fatty acid content

Measure using a slightly modified version of the Qiu et al. (2023) approach. Add 0.5 g to 25 mL of chloroform-methanol solution (2:1, v/v), shake for 20 min, react at 4 °C for 2 h, filter, add 10 mL of 0.9% NaCl solution, centrifuge at 4 °C and 4000 rpm for 10 min, blow with nitrogen at 65 °C, and saponify in a 60 °C water bath for 30 min. Add 3 mL of 0.125 mol/L KOH and methanol solution (7 g KOH + 1 L methanol) and cool to room temperature. Add 3 mL of 14% boron trifluoride and methanol solution and saponify for 30 min. Then add 2 mL of hexane and 1 mL of ultrapure water. The sample is blown to constant weight with nitrogen gas, and then diluted to 10 mL volume with n-hexane. Then pass the sample through 0.22 μm organic membrane filter.

The amount of fatty acids in the sample was determined using a gas chromatograph-mass spectrometer (QP2010-SE; Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). The gas chromatography (GC) working conditions were as follows: an HP-5 ms capillary chromatography column (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm; Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA); a sample inlet temperature of 250 °C; with helium serving as the carrier gas at a 1.5 mL/min flow rate. The temperature was maintained at 60 °C for 1 min, increased to 160 °C at 10 °C/min for 5 min, increased to 200 °C at 3 °C/min for 10 min, and then maintained at 280 °C at 6 °C/min for 5 min. The split ratio was 10:1, and the injection volume was 1 L. The following mass spectrometry (MS) operating parameters were used: an ion source temperature of 250 °C, an electron energy of 70 eV, and a mass scan range of 35–500 m/z. The time allotted for solvent removal was 2 min.

2.10. Determination of free amino acid content

A 0.5 g sample was taken, and 5 mL of 0.1 mol/L HCl was added. The material was homogenized for 30 min before being centrifuged at 4 °C for 10 min at 10,000 rpm. The above operation was repeated, and the supernatants were combined in a 10 mL volumetric flask. The volume was altered by adding ultrapure water. Then, 5 mL of a 10% (m/v) solution of trichloroacetic acid was added to 5 mL of the solution in a 50 mL centrifuge tube. The sample was allowed to stand for 1 h and centrifuged (10,000 rpm, 4 °C, 10 min). Then, a 15 mL volumetric flask was filled with the supernatant. The pH was adjusted to 2 with a 6 mol/L solution of NaOH, and the volume was adjusted. After passing the aforementioned solution through a 0.22 μm aqueous-phase membrane filter, the amount of amino acids was measured using an automatic amino acid analyser.

2.11. Sensory evaluation

The sensory assessment procedure was carried out according to Xu, Liu, et al. (2022)), Xu, Lu, et al. (2022)) and Xu, Zhang, et al. (2022)), with slight modifications. Fifteen healthy, non-smoking and experienced assessors (5 males and 10 females, aged 20–30) were recruited from doctoral and master students in the Laboratory of Aquatic Flavor Chemistry of Ocean University of China to form a sensory assessment team. They all participated in the evaluation based on GB/T 39625–2020 Chinese national standard “Sensory Analysis - Methods - General Rules for Establishing Sensory Profiles”. Panelists were trained to evaluate the following standard taste solutions: 1 mM quinine sulfate (bitter taste), 8 mM monosodium glutamate (MSG) (umami taste), 5 mM citric acid (sour taste), and 10 mM glutathione (kokumi taste). Each sensory attribute uses a 5-point scale (0, none; 1, weaker; 2, weak; 3, medium; 4, strong; 5, stronger) Score the main indicators of the sample such as gloss, fullness, odor, freshness and elasticity. Informed consent is recognized for all participants prior to this study and the rights and privacy of each participant are ensured.

Sensory analysis is performed in a separate booth at room temperature in daylight. The caviar samples with varying storage times were divided into seven portions, each consisting of 2 g of caviar placed in a plastic dish. Subsequently, three random digits were selected and marked for identification purposes. Evaluators were instructed to conduct an olfactory assessment on each sample for a minimum duration of 5 s, followed by chewing the sample in their mouth for no <3 s. Finally, they rinsed their mouths with 20 mL of purified water to ensure accurate results. Testing procedures follow sensory research protocols, including ISO 11136 standards.

2.12. Determination of microstructure

With a 20 kV acceleration voltage, a scanning electron microscope was used to analyze the surface morphology of sturgeon caviar. Gold was sprayed on the sturgeon caviar before imaging.

2.13. Analysis of volatiles based on GC × GC-time-of-flight-MS

According to the method described by Xu, Liu, et al. (2022)), Xu, Lu, et al. (2022)) and Xu, Zhang, et al. (2022)), a sample containing 10 μL n-alkanes was placed in a 20 mL headspace flask, incubated at 60 °C for 10 min, adsorbed for 30 min (Solid Phase Micro Extraction, Supelco, Millipore, America), and analyzed at 250 °C for 5 min. GC × GC-time-of-flight mass spectrometry (TOFMS) system consisted of an Agilent 8890A gas chromatograph and an Agilent 7200 time-of-flight mass spectrometer (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA). The GC conditions were as follows. The separation system consisted of a DB-HeavyWAX one-dimensional (1D) column (30 m × 250 μm × 0.5 μm; Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and an Rxi-5Sil MS two-dimensional (2D) column (2 m × 150 μm × 0.15 μm; Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). As the carrier gas, high-purity helium was used at a constant flow rate of 1.0 mL/min. The temperature was 40 °C for 3 min in the DB-HeavyWAX 1D column, ramped up to 250 °C at 5 °C/min, and then held for 5 min. The Rxi-5Sil MS 2D column had a higher temperature ramp than the 1D column. With a modulation time of 4 s, the modulator temperature was always 15 °C higher than the 2D column and the ramp-up temperature was 5 °C higher than the 1D column. The temperature of the injection port was 250 °C.

The MS conditions were as follows: a transmission line temperature of 250 °C, an ion source temperature of 250 °C, an acquisition rate of 200 spectra/s, an electron bombardment energy of 70 eV, a detection voltage of 2022 V, and a mass scan range of 35–550 m/z. The ROAV acronym stands for the ratio of a volatile compound's concentration to its associated threshold, and a compound with an ROAV of >1 is considered to contribute to the overall odor of a sample.

2.14. Untargeted lipidomics analysis by ultrahigh-performance liquid chromatography–quadrupole Exactive Orbitrap MS

In a 2 mL centrifuge tube, add 280 μL of methanol-water solution (2:5, v/v) and 400 μL of methyl tert-butyl ether, and crush at 10 °C and 50 Hz for 6 min using a frozen tissue grinder. Ultrasound (5 °C, 40 kHz) for 30 min, refrigerated at −20 °C for 30 min. Take 350 μL of supernatant, centrifuge for 15 min (13,000g, 4 °C), place in an Eppendorf tube, dry with nitrogen, and dissolve in a 100 μL isopropanol-acetonitrile solution (1:1, v/v). After swirling for 30 s, the samples were subjected to ultrasound for 5 min in a 40 kHz ice bath, centrifugation for 10 min (13,000g, 4 °C), and analyzed using ultra-high performance liquid chromatography (UHPLC) in series with a Fourier transform MS system. Analysis of samples using the Vanquish Horizon UHPLC quadrupole detection system equipped with an Accucore C30 column (100 mm × 2.1 mm i.d., 2.6 μm; Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The mobile phases consisted of 10 mM ammonium acetate in acetonitrile: water (1:1, v/v) with 0.1% (v/v) formic acid (solvent A) and 2 mM ammonium acetate in acetonitrile: isopropyl alcohol: water (10:88:2, v/v/v) with 0.02% (v/v) formic acid (solvent B). The following were the standard sample injection parameters: a flow rate of 0.4 mL/min, a volume of 2 μL, a column temperature of 40 °C, and a total chromatographic separation time of 20 min. The solvent gradient was altered based on the following conditions: 0–4 min linear gradient from 35% to 60% B; 4–12 min linear gradient from 60% to 85% B; 12–15 minelinear gradient from 85% to 100% B; 15–17 min linear gradient from 100% to 35% B; 17–18 min linear gradient from 100% to 35% B; and then held at 35% B until the end of the separation process.

The sample's MS signal was acquired using positive-ion and negative-ion scanning modes, and the mass scan range was 200–2000 m/z. The ion source temperature was 370 °C, the sheath gas pressure was 413 kPa, the auxiliary heating gas pressure was 137 kPa, the positive-ion mode spray voltage was 3000 V, the negative-ion mode spray voltage was 3000 V, and the collision energy was cycled from 20 to 40 and 60 V. In data-dependent acquisition mode, data were gathered.

2.15. Data analysis

Statistical Product and Service Solutions software (version 25.0; SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used to analyze the data. The data were visualized using Origin 2021 (OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA, USA). Venn diagrams and heat maps were generated and principal component analysis (PCA) and related network analysis were carried out using the OmicShare tool.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Effect of LVEF treatment on degradation of protein in sturgeon caviar

The degree of oxidation of caviar was assessed for different storage times. The sulfhydryl content of the LVEF treated group was 1.213 times higher than that of the control group after 6 weeks of storage (Fig. 1A). This indicated that LVEF has a significant inhibitory effect on protein degradation as the storage period increases. The carbonyl content of the LVEF treated group was significantly lower than the control group after 4 weeks of storage, suggesting that the inhibitory effect of LVEF on protein carbonylation was enhanced (Fig. 1B). In the early stages of storage, under the stimulation of LVEF, sturgeon caviar produced ATP at a faster rate leading to changes in the spatial conformation of myofibrillar protein. The thiol groups buried inside the protein molecule were exposed and oxidized to form disulphide bonds, resulting in a somewhat lower initial thiol content in the LVEF treated group than in the control group. The exposure of protein side chains promoted the increase in carbonyl content, which led to a slightly higher carbonyl content in the initial stage of storage in the LVEF treatment group than in the control group (Jia et al., 2018). However, in the later stage of storage oxidative degradation of myofibrillar protein was the main reason for the differences in content. LVEF altered the myofilament arrangement of myofibrils and therefore results in lower oxidation of myofibrillar proteins, which was consistent with the findings of Xie et al. (2023). The TVB-N content in the LVEF treated group was significantly lower than the control group after 5 weeks of caviar storage at −4 °C (Fig. 1C). The ozone produced by the electrostatic field inhibits the activity of spoilage microorganisms and enzymes in the food, thus delaying the production of TVB-N (Papachristodoulou et al., 2018). The above results indicated that LVEF treatment could effectively delay the oxidative degradation of proteins during the storage of sturgeon caviar to a certain extent. The longer the storage time, the more obvious the inhibitory effect.

Fig. 1.

Effects of low-voltage electrostatic field on (A) thiol content, (B) carbonyl content, (C) total volatile basic nitrogen content, (D) acid value, (E) peroxide value, and (F) thiobarbituric acid value of myofibrillar protein. (G, H) Histograms showing the fatty acid content in the LVEF treatment group and the control group. A difference between letters means a significant difference (p < 0.05).

3.2. Effect of LVEF treatment on lipid oxidation in sturgeon caviar

With the increase in storage time, the acid values in the LVEF treated group were significantly lower than those in the control group (Fig. 1D). The results of peroxide value were similar to acid value (Fig. 1E). Electrostatic field can effectively eliminate free radicals and retard the generation of peroxides in sturgeon caviar (Liu, Xu, et al., 2023). The TBA values increased slowly in the LVEF treated group. The TBA values in the control group (3.731 ± 0.195 mg/kg) were 4.3 times higher than those in the LVEF treated group (0.869 ± 0.068 mg/kg) after 6 weeks of storage (Fig. 1F). Huang et al. (2020) measured the trends of changes in TBA value and TVB-N content during the storage of catfish fillets treated with the electrostatic field, which were consistent with the results of this study. The above results indicated that LVEF treatment can effectively reduce the rate of lipid oxidation in sturgeon caviar during storage.

3.3. Effect of LVEF treatment on fatty acid content of sturgeon caviar

The effect of LVEF treatment on the fatty acid content of sturgeon caviar during storage was shown in Fig. 1G and Fig. 1H. Overall, the fatty acid content of the LVEF treated group was lower than the control group. The α-linolenic acid content were consistently higher in the LVEF treated group than the control group after 2–6 weeks. The n-6 fatty acids are widely found in aquatic products, including linoleic acid (C18:2n6) and arachidonic acid (C20:4n6, cis-5,8,11,14), and linoleic acid plays an important role in lowering serum cholesterol levels (Bunga et al., 2023). Linoleic acid levels tended to increase and then decrease in the LVEF treatment group, reaching its highest value (18.156 ± 0.452 mg/g) at 2 weeks, while that in the control group continued to decrease and reached 11.546 ± 0.294 mg/g at 6 weeks. This was due to the electrostatic induction generated by LVEF charged the surface of the food, reducing the contact area between the surface and oxygen, thereby slowing down fat oxidation (Ko et al., 2016).

3.4. Effect of LVEF treatment on the taste activity value of free amino acids in sturgeon caviar

The TAVs of free amino acids during the storage of the two groups of sturgeon caviar were shown in Table 1. With regard to the freshening amino acids (Asp and Glu), the TAV values of Glu in the LVEF treated group were consistently higher than those in the control group from 0 to 5 weeks, and the total mean value was highest at 3 weeks (1.343 ± 0.004), suggesting that LVEF promoted the production of freshening amino acids in sturgeon caviar. During storage, although the TAVs of Asp was always <1, Asp was not only the main source of a meat aroma in aquatic products but also exerts a synergistic effect with Glu. This significantly improved the product's freshness (Manninen et al., 2018). The TAVs of Lys (bitter taste), in the two groups began to exceed 1 from 5 to 6 weeks. The content of Arg (bitter taste) was >1 at 3 weeks of storage in the LVEF treatment. Although Arg is a bitter amino acid, it could counteract the fishy odor in aquatic products at low concentrations and made a positive contribution to the odor of aquatic products (Yin et al., 2022). Free amino acid TAVs showed a general increasing trend during storage in both groups. However, after 3–6 weeks, the free amino acid TAVs of the LVEF treatment group were higher than the control group. This was due to the delayed Strecker reaction of free amino acids in sturgeon caviar caused by LVEF technology in the later stage, which degraded into volatile compounds.

Table 1.

Influence of low voltage electrostatic field on TAVs of sturgeon caviar.

| TOO(mg/100 g) | Group | 0w | 1w | 2w | 3w | 4w | 5w | 6w | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asp | 100 | Experimental | 0.166 ± 0.003g | 0.231 ± 0.005f | 0.273 ± 0.004e | 0.358 ± 0.001c | 0.348 ± 0.006d | 0.402 ± 0.003a | 0.372 ± 0.001b |

| Control | 0.166 ± 0.003g | 0.242 ± 0.002f | 0.309 ± 0.004d | 0.326 ± 0.001c | 0.254 ± 0.006e | 0.386 ± 0.002a | 0.380 ± 0.005b | ||

| Glu | 30 | Experimental | 0.880 ± 0.016g | 1.034 ± 0.036f | 1.073 ± 0.013e | 1.343 ± 0.004b | 1.273 ± 0.020d | 1.403 ± 0.007a | 1.305 ± 0.013c |

| Control | 0.880 ± 0.016g | 1.021 ± 0.049c | 1.185 ± 0.015b | 1.213 ± 0.001b | 0.925 ± 0.006d | 1.339 ± 0.005a | 1.321 ± 0.013a | ||

| Thr | 260 | Experimental | 0.044 ± 0.001f | 0.066 ± 0.001e | 0.081 ± 0.001d | 0.109 ± 0.001c | 0.109 ± 0.002c | 0.128 ± 0.001a | 0.120 ± 0.001b |

| Control | 0.044 ± 0.001f | 0.071 ± 0.002e | 0.093 ± 0.001c | 0.101 ± 0.001b | 0.080 ± 0.001d | 0.124 ± 0.001a | 0.122 ± 0.002a | ||

| Ser | 150 | Experimental | 0.055 ± 0.001g | 0.083 ± 0.002e | 0.104 ± 0.001d | 0.146 ± 0.001c | 0.147 ± 0.002c | 0.177 ± 0.001a | 0.169 ± 0.001b |

| Control | 0.055 ± 0.001g | 0.092 ± 0.003f | 0.125 ± 0.001d | 0.140 ± 0.001c | 0.113 ± 0.001e | 0.175 ± 0.001b | 0.177 ± 0.001a | ||

| Gly | 130 | Experimental | 0.037 ± 0.001d | 0.047 ± 0.001cd | 0.054 ± 0.001bc | 0.068 ± 0.009ab | 0.058 ± 0.011abc | 0.072 ± 0.006a | 0.063 ± 0.012ab |

| Control | 0.037 ± 0.001d | 0.044 ± 0.003cd | 0.048 ± 0.012bc | 0.049 ± 0.001bc | 0.049 ± 0.002bc | 0.072 ± 0.001a | 0.057 ± 0.001b | ||

| Ala | 60 | Experimental | 0.185 ± 0.006f | 0.307 ± 0.010e | 0.378 ± 0.014d | 0.571 ± 0.001c | 0.569 ± 0.008c | 0.653 ± 0.007a | 0.632 ± 0.001b |

| Control | 0.185 ± 0.006f | 0.335 ± 0.031e | 0.496 ± 0.005c | 0.540 ± 0.001b | 0.374 ± 0.003d | 0.640 ± 0.002a | 0.645 ± 0.005a | ||

| Met | 30 | Experimental | 0.169 ± 0.020e | 0.279 ± 0.015d | 0.411 ± 0.031c | 0.753 ± 0.036b | 0.731 ± 0.015b | 0.879 ± 0.025a | 0.848 ± 0.052a |

| Control | 0.169 ± 0.020e | 0.377 ± 0.098c | 0.567 ± 0.100ab | 0.704 ± 0.004a | 0.468 ± 0.088bc | 0.714 ± 0.127a | 0.716 ± 0.083a | ||

| Lys | 50 | Experimental | 0.287 ± 0.012f | 0.510 ± 0.011e | 0.661 ± 0.008d | 0.923 ± 0.006c | 0.929 ± 0.022c | 1.103 ± 0.019a | 1.056 ± 0.001b |

| Control | 0.287 ± 0.012f | 0.552 ± 0.006e | 0.770 ± 0.020c | 0.873 ± 0.004b | 0.686 ± 0.003d | 1.083 ± 0.004a | 1.091 ± 0.009a | ||

| Arg | 50 | Experimental | 0.301 ± 0.017f | 0.488 ± 0.023d | 0.693 ± 0.052c | 1.038 ± 0.006b | 1.014 ± 0.039b | 1.130 ± 0.062a | 1.173 ± 0.026a |

| Control | 0.301 ± 0.017f | 0.630 ± 0.012e | 0.867 ± 0.031c | 0.976 ± 0.016b | 0.745 ± 0.038d | 1.182 ± 0.018a | 1.169 ± 0.012a | ||

| Ile | 40 | Experimental | 0.272 ± 0.015f | 0.429 ± 0.098d | 0.606 ± 0.008c | 0.844 ± 0.003b | 0.839 ± 0.012b | 0.949 ± 0.040a | 0.846 ± 0.004b |

| Control | 0.272 ± 0.015f | 0.516 ± 0.011e | 0.699 ± 0.104c | 0.800 ± 0.019b | 0.627 ± 0.010d | 0.914 ± 0.031a | 0.939 ± 0.035a | ||

| Leu | 380 | Experimental | 0.086 ± 0.004f | 0.124 ± 0.004e | 0.158 ± 0.002d | 0.214 ± 0.005bc | 0.211 ± 0.014c | 0.236 ± 0.003a | 0.223 ± 0.009b |

| Control | 0.086 ± 0.004f | 0.137 ± 0.027e | 0.179 ± 0.026c | 0.193 ± 0.005b | 0.149 ± 0.015d | 0.224 ± 0.001a | 0.222 ± 0.002a | ||

| His | 20 | Experimental | 0.189 ± 0.006f | 0.211 ± 0.050d | 0.369 ± 0.005c | 0.481 ± 0.022b | 0.500 ± 0.011b | 0.578 ± 0.030a | 0.555 ± 0.010a |

| Control | 0.189 ± 0.006f | 0.312 ± 0.009e | 0.397 ± 0.020c | 0.452 ± 0.012b | 0.356 ± 0.005d | 0.562 ± 0.016a | 0.580 ± 0.006a | ||

| Tyr | 90 | Experimental | 0.088 ± 0.002f | 0.183 ± 0.005e | 0.247 ± 0.004d | 0.336 ± 0.009c | 0.366 ± 0.063bc | 0.416 ± 0.008a | 0.396 ± 0.001b |

| Control | 0.088 ± 0.002f | 0.200 ± 0.003e | 0.278 ± 0.006c | 0.314 ± 0.001b | 0.246 ± 0.002d | 0.393 ± 0.002a | 0.394 ± 0.003a | ||

| Phe | 90 | Experimental | 0.138 ± 0.013e | 0.289 ± 0.044d | 0.307 ± 0.065c | 0.520 ± 0.008b | 0.528 ± 0.004b | 0.602 ± 0.011a | 0.583 ± 0.008a |

| Control | 0.138 ± 0.013e | 0.305 ± 0.021c | 0.402 ± 0.039b | 0.474 ± 0.001a | 0.321 ± 0.001c | 0.486 ± 0.001a | 0.482 ± 0.004a | ||

| Val | 40 | Experimental | 0.195 ± 0.016f | 0.382 ± 0.044d | 0.507 ± 0.013c | 0.759 ± 0.008b | 0.771 ± 0.012b | 0.906 ± 0.013a | 0.873 ± 0.003a |

| Control | 0.195 ± 0.016f | 0.434 ± 0.026e | 0.643 ± 0.006c | 0.721 ± 0.001b | 0.543 ± 0.003d | 0.896 ± 0.006a | 0.899 ± 0.009a |

Note: Different superscript letters within the same row indicate significant differences among samples (p < 0.05); TOO: threshold of odor.

3.5. Effect of LVEF treatment on the sensory qualities of sturgeon caviar

The analysis results of the artificial sensory score changes of two groups of sturgeon caviar during storage were shown in Fig. 2A-F. The sensory scores of sturgeon caviar in both groups showed an overall decreasing trend with the extension of storage time. However, the sensory scores of the five indicators were higher in the LVEF treated group than the control group, indicating that LVEF was beneficial to increase the sensory attributes of sturgeon caviar. Elasticity was an extremely important indicator for consumers to evaluate the quality of sturgeon caviar (Chen et al., 2019). The elasticity score of sturgeon caviar in the LVEF treated group was the highest at 3 weeks of storage. The most significant change in elasticity was observed in LVEF treatment sturgeon caviar, which was 40.73% higher than the control after 6 weeks of storage. LVEF could effectively improve the quality and sensory properties of caviar. This was due to the autolysis of proteins by the action of enzymes (Sun et al., 2022), which increased the loss rate of sturgeon caviar sauce, continuously reduced surface water content, and significantly reduced glossiness. The LVEF could ionize oxygen in the air, increased the negative charge between myofibrils, and changed the amount of water in food, which stimulated the dissolution of myogenic fibers and the inability of some free water to move. This maintained to some extent the compactness and water-holding capacity of the structure of the sample and thus achieved the purpose of delaying the deterioration of the quality of sturgeon caviar (Hu et al., 2021).

Fig. 2.

Changes in (A) glossiness, (B) fullness, (C) odor, (D) umaminess, (E) elasticity, (F) total score and (G) microstructure of sturgeon caviar during storage under treatment by the low-voltage electrostatic field. Differences between letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05).

3.6. Effect of LVEF treatment on the micromorphology of sturgeon caviar

Changes in the microstructure of LVEF treated sturgeon caviar were observed by scanning electron microscopy as shown in Fig. 2G. Compared to the control group, the caviar LVEF treated group showed less fragmentation and lamellar layers after 3–4 weeks of storage, and did not show membrane rupture after 4–6 weeks of storage, suggesting that LVEF has an inhibitory effect on the rupture of cell membranes. The cell membrane of sturgeon caviar consists of a layer of collagen, which contained a high amount of insoluble collagen (Yoon et al., 2018). During storage, endogenous proteases promote hydrolysis of myogenic fibers and collagen, and intercellular cross-linking were weakened (Vilgis, 2020), leading to rupture of sturgeon caviar membranes and outflow of inclusions. This suggested that LVEF was beneficial in maintaining the tightness of collagen fibers and the structural integrity of sturgeon caviar.

3.7. GC × GC-TOFMS determination of the effect of LVEF treatment on the flavor of sturgeon caviar

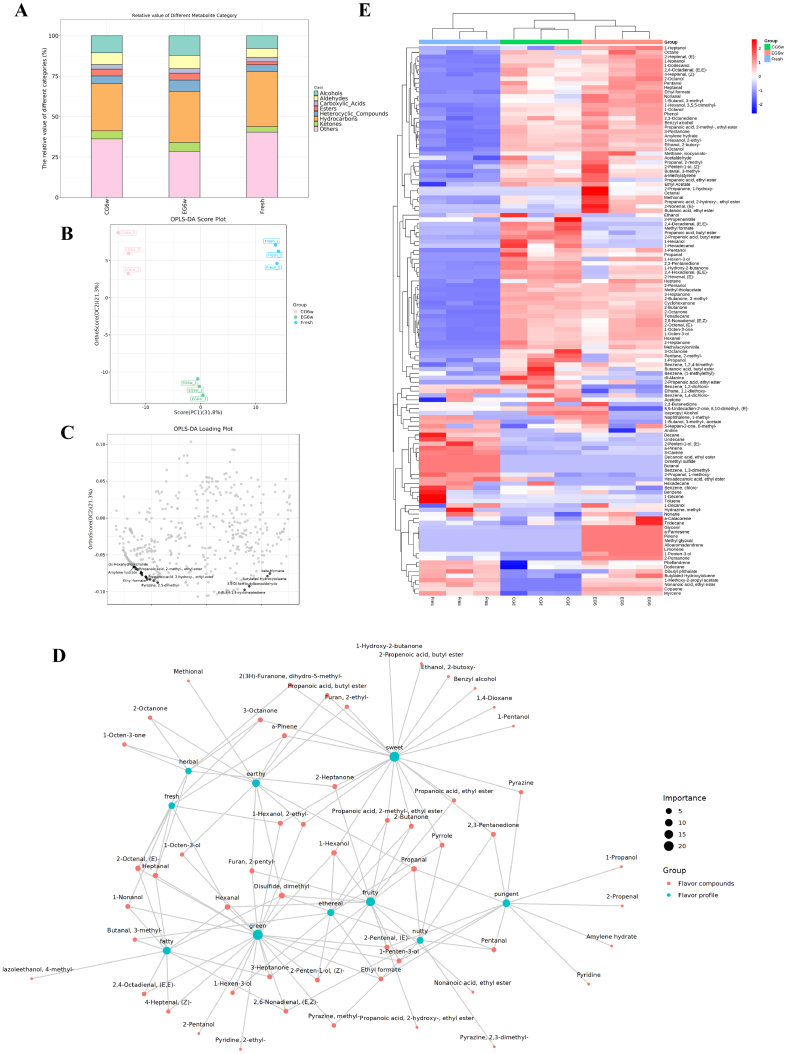

Three caviar samples had a total of 877 volatile chemicals, including 43 ketones, 25 aldehydes, 45 esters, 69 alcohols, 30 carboxylic acids, 264 hydrocarbons, 64 heterocyclic compounds, and 337 other compounds. Compared with fresh caviar, the types of ketones (1.73%), aldehydes (2.31%), esters (2.52%) and alcohols (3.45%) of volatile compounds in caviar preserved for 6 weeks were significantly increased (Fig. 3A). Fig. 3B shown an OPLS-DA score plot of volatile compounds. The first and second principal components (PC1 and PC2) explained 21.3% and 31.8%, respectively, of the cumulative contribution to the variance. This shown that PC1 and PC2 could effectively distinguish the three samples, and the volatile compounds were significantly different. The key volatile compounds in the various samples were screened using the variable importance in projection (VIP) approach, and compounds with VIP >1 were thought to be possible markers. The next seven volatile chemicals displayed the most notable changes and had the highest contribution rates: β-myrcene, tert-amyl alcohol, butylated hydroxytoluene, cis-hexahydrophthalide, ethyl formate, ethyl 2-hydroxypropionate, and ethyl 2-methylpropionate (Fig. 3C). As a result, these volatiles could be used as flavor markers to discriminate between different groups.

Fig. 3.

(A) Diagram of accumulation of volatile compounds in samples. (B) Results of orthogonal partial least squares discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA) of volatile compounds in samples. (C) OPLS-DA loading plot of volatile compounds in samples. (D) Network diagram of types of volatile compounds and flavor attributes of samples. (E) Heat map of volatile substances in different groups.

The main sensory properties of caviar were determined to be sweet, fruity, and green (Fig. 3D). The results indicated that the main aroma active compounds in caviar treated with LVEF (ROAVs >1) in caviar included aldehydes (E,Z)-2,6-nonadienal, (E)-2-octenal, heptanal, and nonanal) and ketones (1-octen-3-one and 2,3-butanedione). According to the heat map analysis of volatile compounds in samples from the three groups (Fig. 3E), heptanal (fatty, green) and nonanal (fatty, green, rose, fresh) exhibited the most significant changes in content after LVEF treated, and their contents increased by 16.725% and 15.845%, respectively. This was because the LVEF inhibited the activity of catalase in caviar and thus slowed down the secondary oxidation of unsaturated fatty acids (linolenic acid, linoleic acid, etc.) (Yang et al., 2023). The content of hexanal in the LVEF treatment group was 1.2 times that in the control group. Lee et al. (2014) used hexanal (fat, green, fruity) as an indicator of freshness. The higher the hexanal content, the better the freshness, and therefore the LVEF treatment caviar was fresher. The content of (E,Z)-2,6-nonadienal (herbaceous, fresh) and (E)-2-octenal (herbaceous, earthy) in LVEF treatment sturgeon caviar increased by 27% and 22%, respectively after 6 weeks of storage (Zhang et al., 2022). The content of 1-octen-3-one (soil, mushrooms) and 2,3-butanedione (cheese, nuts) in caviar treated with LVEF is the highest (Jia et al., 2023). 1-penten-3-ol (fruit, butter, green) was only detected in caviar treated with LVEF, providing new odor properties for caviar. This indicated that LVEF technology can increase the flavor characteristic properties of caviar. The LVEF affected the transmembrane potential of cell membranes and inhibited electron transfer during caviar lipid oxidation, leading to differences in the pathways and rates of flavor formation (Liu, Shen, et al., 2023; Liu, Xu, et al., 2023; Peng et al., 2023).

3.8. Effect of LVEF treatment on lipid composition of sturgeon caviar determined by untargeted lipidomics

A total of 1873 lipid metabolites were identified in caviar samples, including 1111 in positive-ion mode (Pos) and 762 in negative-ion mode (Neg). From the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) compound database, five classes of lipids were retrieved (Fig. 4A): glycerophospholipids (GP) (51.50%), glycerides (GL) (33.46%), sphingolipids (SP) (13.21%), sterols (ST) (0.92%), and fatty acids (FA) (0.92%). Glycerophospholipids had the largest concentrations of phosphatidylcholine (PC) and phosphatidylethanolamine (PE). The PCA analysis results were shown in Fig. 4B, where the two principal components (PC1 and PC2) account for 27.60% and 22.90% of the variance, respectively, with significant differences among different samples. The PLS-DA score chart (Fig. 4C) shown partial overlap between the LVEF treatment group at 6 weeks and the control group at 4 weeks, with small differences. This indicated that the lipid metabolism rate of caviar treated with LVEF is inhibited, and its freshness was higher.

Fig. 4.

(A) Distribution map of total types of lipid metabolites. (B) Principal component analysis score plot of samples. (C) Partial least squares discriminant analysis score plot of samples. Variable importance in projection heat maps of different groups: (D) Fresh after 0 weeks (Fresh0w) vs LVEF treatment group after 6 weeks (EG6w), (E) EG6w vs control group after 6 weeks (CG6w), (F) Fresh0w vs CG6w.

On the basis of the OPLS-DA model, lipids with a VIP >1 and p < 0.05 were regarded as differential lipids. A total of 151 differential lipids (Pos 42, Neg 109) were detected in the CG6w group vs the EG6w group, 306 differential lipids (Pos 175, Neg 131) were detected in the CG6w group vs the Fresh after Fresh0w group, and 251 differential lipids (Pos 137, Neg 114) were detected in the EG6w group vs the Fresh0w group. Among these, FA(20:5), PC(16:0/22:6), FA(22:6), FA(20:4), PC(18:0/20:5), dMePC(18:4/16:1), PE(16:0/20:5), PE(18:0/22:6), PC(18:1/18:2), PE(18:0/20:4), PC(18:1/18:1), PS(18:1/21:0), PC(18:1/22:6), PC(16:0/18:2), and PC(16:0/18:1) exhibited significant differences in abundance. Fig. 4D-F shown the changes in lipid composition of caviar after LVEF treatment. Among them, CerPE(d16:0/17:0), MGMG (16:0), and LPC(16:0) were the lipids with the highest VIP scores. This was because as the main component of the cell membrane of caviar, they had strong binding ability with water molecules and could form a network structure to maintain water. After being treated with LVEF, the binding state of water molecules and active enzymes in caviar was changed, resulting in resonance phenomenon, decreased enzyme activity, and slower lipid oxidation degradation (Peng et al., 2023).

3.9. Correlations between key flavor-active compounds and lipid molecules

According to the Pearson coefficient, aldehyde, ketone and lipid metabolites with significant changes in content after LVEF treatment were selected for correlation analysis (Fig. 5A). The results showed that methyl phosphatidylcholine (MePC) was significantly negatively correlated with hexanal, (E,Z)-2,6-nonadienal, (E)-2-octanal, nonanal, and heptanal (p < 0.05). MePC is a major component of cell membranes, which contain polyunsaturated fatty acids. Oleic and linoleic acids produces linear aldehydes such as hexanal, heptanal and nonanal (Wang et al., 2023). Hexanal, heptanal and nonanal typically produce fruity and fatty flavor that were characteristic of sturgeon caviar (Qiu et al., 2023). Therefore, the characteristic flavor of caviar could be enhanced by LVEF treatment. PC (18:0/20:5) showed a positive correlation with 3-methylbutanal and 2,3-octanedione (p < 0.05), and PC (18:1e/22:6) also showed a significant positive correlation with 3-methylbutanal (p < 0.05). 3-Methylbutyraldehyde had a putrid odor, mainly formed by Streker degradation of leucine through the Ehrlich reaction, and could be used as a quality indicator during the maturation process of caviar (Xu, Liu, et al., 2022; Xu, Lu, et al., 2022; Xu, Zhang, et al., 2022).

Fig. 5.

(A) Heat map of the relationships between the top 50 abundant lipids and the volatile aldehydes and ketones in the different groups. (B) Map of potential formation pathways of flavor-active compounds based on the comparison of Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes pathways (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001).

KEGG functional pathway analysis showed that the impact of LVEF on caviar mainly involved glycerol phospholipid metabolism, linoleic acid metabolism, and α-Linolenic acid metabolism. The metabolism of glycerol phospholipids was involved in PC, LPC, PS, and PE, and they could convert each other. Compared with the control group, the glycerol phospholipid metabolism pathway of caviar treated with LVEF increased the conversion pathway of PS (18:0/22:6) and PE (18:0/18:0), while the phospholipase D metabolism pathway increased the conversion pathway of DG (16:0/18:1). After LVEF treated, the cell membrane potential asymmetry shifts, increasing the point of action of phospholipase D, resulting in an increase in phospholipid content. The hydrolysis of PE (18:0/18:0) leaded to an increase in linoleic acid content, which in turn enhanced the characteristic flavor of caviar. Fig. 5B showed the pseudo pathway of lipid formation of caviar flavor substances. The formation of hydroperoxides represented the beginning of fat oxidation, where oleic acid in caviar could produce hydroperoxides such as 10-ROOH and 11-ROOH, degraded to produce octane and heptane, and then generated 1-octane and 1-heptanol through reductase (Yu et al., 2023). The oxidation of linolenic acid produced hexanal, (Z) -3-hexenol, and (E,Z)-2,6-nonadienal. In conclusion, LVEF treatment altered the sites of action of phospholipases in caviar and affected various phospholipid metabolic pathways and flavor formation pathways in caviar.

4. Conclusion

Based on the optimal parameters of various food preservation in LVEF, we applied them to sturgeon caviar storage for the first time. The results of this study showed that LVEF could delay the oxidative degradation of fat and protein, maintain the cell membrane structure of sturgeon caviar, and enhance the flavor characterizations. The advantages of LVEF gradually appeared in the late stage of sturgeon roe storage (3–6 weeks). Lipidomics and flavoromics analyses revealed that FA (20:5), PC (16:0/22:6), and PE (16:0/20:5) could be potential markers for LVEF treatment caviar. The glycerophospholipid oxidation pathway of LVEF treated caviar was changed, which increased the content and types of volatile compounds in sturgeon caviar. This study suggested that the LVEF technology offered a more promising strategy for the cold storage of sturgeon caviar compared to traditional methods. This provided a new theoretical basis for the development of novel equipment and the preservation of sturgeon caviar.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Xinyu Jiang: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Software, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation. Yihuan Liu: Writing – review & editing. Li Liu: Writing – review & editing. Fan Bai: Formal analysis. Jinlin Wang: Funding acquisition. He Xu: Formal analysis. Shiyuan Dong: Formal analysis. Xiaoming Jiang: Visualization, Validation, Investigation. Jihong Wu: Visualization, Validation, Investigation. Yuanhui Zhao: Supervision, Resources, Project administration, Funding acquisition. Xinxing Xu: Supervision, Resources, Project administration, Funding acquisition.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the financial support from Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province), National Natural Science Foundation of China (32102040), Key R & D Program of Hainan Province (ZDYF2022XDNY191), Science and Technology Support Program of North Jiangsu Province (SZ-LYG202120) and Key R & D Program of Shandong Province (2021SFGC0701).

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fochx.2024.101612.

Contributor Information

Fan Bai, Email: bf@kalugaqueen.com.

Shiyuan Dong, Email: dongshiyuan@ouc.edu.cn.

Xiaoming Jiang, Email: jxm@ouc.edu.cn.

Yuanhui Zhao, Email: zhaoyuanhui@ouc.edu.cn.

Xinxing Xu, Email: freshstar129@163.com, xxx@ouc.edu.cn.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary material

Data availability

No data was used for the research described in the article.

References

- Albertos I., Diana A., Cullen P., Tiwari B., Ojha S., Bourke P., Álvarez C., Rico D. Effects of dielectric barrier discharge (DBD) generated plasma on microbial reduction and quality parameters of fresh mackerel (Scomber scombrus) fillets. Innovative Food Science & Emerging Technologies. 2017;44:117–122. doi: 10.1016/j.ifset.2017.07.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Dalali S., Li C., Xu B. Effect of frozen storage on the lipid oxidation, protein oxidation, and flavor profile of marinated raw beef meat. Food Chemistry. 2022;376 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.131881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Holy M., Ruiter J., Lin M., Kang D.H., Rasco B. Inactivation of Listeria innocua in nisin-treated salmon (Oncorhynchus keta) and sturgeon (Acipenser transmontanus) caviar heated by radio frequency. Journal of Food Protection. 2004;67(9):1848–1854. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-67.9.1848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayşe G., Özlem E., Emine Ö., Nermin K. Determination of lipid peroxidation and fatty acid compositions in the caviars of rainbow trout and carp. Journal of Aquatic Food Product Technology. 2018;27(7):803–810. doi: 10.1080/10498850.2018.1499688. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brambilla M., Buccheri M., Grassi M., Stellari A., Pazzaglia M., Romano E., Cattaneo T.M.P. The influence of the presence of borax and NaCl on water absorption pattern during sturgeon caviar (Acipenser transmontanus) storage. Sensors (Basel) 2020;20(24):71–74. doi: 10.3390/s20247174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunga S., Ahmmed M., Lawley B., Carne A., Bekhit A. Physicochemical, biochemical and microbiological changes of jeotgal-like fermented Chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) roe. Food Chemistry. 2023;398 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2022.133880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C., Takahashi K., Geonzon L., Okazaki E., Osako K. Texture enhancement of salted Alaska Pollock (Theragra chalcogramma) roe using microbial transglutaminase. Food Chemistry. 2019;290:196–200. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.03.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fioretto F., Cruz C., Largeteau A., Sarli T.A., Demazeau G., Moueffak A. Inactivation of Staphylococcus aureus and Salmonella enteritidis in tryptic soy broth and caviar samples by high pressure processing. Brazilian Journal of Medical and Biological Research. 2005;38:1259–1265. doi: 10.1590/S0100-879X2005000800015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu F., Qian S., Huang F., Han D., Li X., Zhang C. Combined impacts of low voltage electrostatic field and high humidity assisted-thawing on quality of pork steaks. Food Science and Technology. 2021;150 doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2021.111987. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H., Sun W., Xiong G., Shi L., Jiao C., Wu W., Li X., Qiao Y., Liao L., Ding A., Wang L. Effects of HVEF treatment on microbial communities and physicochemical properties of catfish fillets during chilled storage. Food Science and Technology. 2020;131 doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2020.109667. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jia G., Nirasawa S., Ji X., Luo Y., Liu H. Physicochemical changes in myofibrillar proteins extracted from pork tenderloin thawed by a high-voltage electrostatic field. Food Chemistry. 2018;240:910–916. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.07.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia J., Tian L., Song Q., Liu X., Rubert J., Li M., Duan X. Investigation on physicochemical properties, sensory quality and storage stability of mayonnaise prepared from lactic acid fermented egg yolk. Food Chemistry. 2023;415 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2023.135789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang C., Cai W., Shang S., Miao X., Dong X., Zhou D., Jiang P. Comparative analysis of the flavor profile and microbial diversity of high white salmon (coregonus peled) caviar at different storage temperatures. Food Science and Technology. 2022;169 doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2022.114068. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ko W., Yang S., Chang C., Hsieh C. Effects of adjustable parallel high voltage electrostatic field on the freshness of tilapia (Orechromis niloticus) during refrigeration. Food Science and Technology. 2016;66:151–157. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2015.10.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S., Cho H., Lee K. Volatile compounds as markers of tofu (Soybean curd) freshness during storage. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2014;62(3):772–779. doi: 10.1021/jf404847g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C., Huang L., Hwang C. Effect of temperature and salt on thermal inactivation of Listeria monocytogenes in salmon roe. Food Control. 2017;73:406–410. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2016.08.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F., Xu Y., Zeng M., Zhang Y., Pan L., Wang J., Huang S. A novel physical hurdle technology by combining low voltage electrostatic field and modified atmosphere packaging for long-term stored button mushrooms (Agaricus bisporus) Innovative Food Science & Emerging Technologies. 2023;90 doi: 10.1016/j.ifset.2023.103514. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu N., Shen S., Huang L., Deng G., Wei Y., Ning J., Wang Y. Revelation of volatile contributions in green teas with different aroma types by GC–MS and GC–IMS. Food Research International. 2023;169 doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2023.112845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manninen H., Rotola-Pukkila M., Aisala H., Hopia A., Laaksonen T. Free amino acids and 5′-nucleotides in Finnish forest mushrooms. Food Chemistry. 2018;247:23–28. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papachristodoulou M., Koukounaras A., Siomos A., Liakou A., Gerasopoulos D. The effects of ozonated water on the microbial counts and the shelf life attributes of fresh-cut spinach. Journal of Food Processing and Preservation. 2018;42(1) doi: 10.1111/jfpp.13404. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peng J., Liu C., Xing S., Bai K., Liu F. The application of electrostatic field technology for the preservation of perishable foods. Food Science and Technology. 2023;43 doi: 10.1590/fst.121722. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu D., Duan R., Wang Y., He Y., Li C., Shen X., Li Y. Effects of different drying temperatures on the profile and sources of flavor in semi-dried golden pompano (Trachinotus ovatus) Food Chemistry. 2023;401 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2022.134112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J., Zheng J., Wang Y., Yang S., Yang J. The exogenous autophagy inducement alleviated the sea cucumber (Stichopus japonicus) autolysis with exposure to stress stimuli of ultraviolet light. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. 2022;102(8):3416–3424. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.11689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilgis T. The physics of the mouthfeel of caviar and other fish roe. International Journal of Gastronomy and Food Science. 2020;19 doi: 10.1016/j.ijgfs.2019.100192. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Xiang X., Wei S., Li S. Multi-omics revealed the formation mechanism of flavor in salted egg yolk induced by the stages of lipid oxidation during salting. Food Chemistry. 2023;398 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2022.133794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Y., Zhou K., Chen B., Ma Y., Tang C., Li P., Wang Z., Xu F., Li C., Zhou H., Xu B. Mechanism of low-voltage electrostatic fields on the water-holding capacity in frozen beef steak: Insights from myofilament lattice arrays. Food Chemistry. 2023;428 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2023.136786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu C., Zhang X., Liang J., Fu Y., Wang J., Jiang M., Pan L. Cell wall and reactive oxygen metabolism responses of strawberry fruit during storage to low voltage electrostatic field treatment. Postharvest Biology and Technology. 2022;192 doi: 10.1016/j.postharvbio.2022.112017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu P., Liu L., Liu K., Wang J., Gao R., Zhao Y., Bai F., Li Y., Wu J., Zeng M., Xu X. Flavor formation analysis based on sensory profiles and lipidomics of unrinsed mixed sturgeon surimi gels. Food Chemistry: X. 2022;17 doi: 10.1016/j.fochx.2022.100534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X., Lu S., Li X., Bai F., Wang J., Zhou X., Gao R., Zeng M., Zhao Y. Effects of microbial diversity and phospholipids on flavor profile of caviar from hybrid sturgeon (Huso dauricus × Acipenser schrencki) Food Chemistry. 2022;377 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.131969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C., Wu G., Li Y., Zhang C., Liu C., Li X. Effect of low-voltage electrostatic field on oxidative denaturation of myofibrillar protein from lamb-subjected freeze–thaw cycles. Food and Bioprocess Technology. 2023;16(9):2070–2081. doi: 10.1007/s11947-023-03041-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yin M., Matsuoka R., Yanagisawa T., Xi Y., Zhang L., Wang X. Effect of different drying methods on free amino acid and flavor nucleotides of scallop (patinopecten yessoensis) adductor muscle. Food Chemistry. 2022;396 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2022.133620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon I., Lee G., Kang S., Park S., Lee J., Kim J., Heu M. Chemical composition and functional properties of roe concentrates from skipjack tuna (Katsuwonus pelamis) by cook-dried process. Food Science & Nutrition. 2018;6(5):1276–1286. doi: 10.1002/fsn3.676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Z., Ye L., He Y., Lu X., Chen L., Dong S., Xiang X. Study on the formation pathways of characteristic volatiles in preserved egg yolk caused by lipid species during pickling. Food Chemistry. 2023;424 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2023.136310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yun X., Zhang X., Sarula, Cheng P., Dong T. Change of the frozen storage quality of concentrated mongolian milk curd under the synergistic action of ultra-high pressure and electric field. Food Science and Technology. 2023;177 doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2023.114462. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J., Fei L., Cui P., Walayat N., Ji S., Chen Y., Lyu F., Ding Y. Effect of low voltage electrostatic field combined with partial freezing on the quality and microbial community of large yellow croaker. Food Research International. 2023;169 doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2023.112933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S., Fang X., Wu W., Tong C., Chen H., Yang H., Gao H. Effects of negative air ions treatment on the quality of fresh shiitake mushroom (Lentinus edodes) during storage. Food Chemistry. 2022;371 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.131200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material

Data Availability Statement

No data was used for the research described in the article.