Abstract

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is one of the most common neurodevelopmental disorders with significant individual and societal negative impacts of the disorder continuing into adulthood (Danielson et al. in Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, in press; Landes and London in Journal of Attention Disorders 25:3–13, 2021). Genetic and environmental risk (e.g., modifiable exposures such as prenatal tobacco exposure and child maltreatment) for ADHD is likely multifactorial (Faraone et al. in Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 128:789–818, 2021). However, the evidence for potentially modifiable contextual risks is spread across studies with different methodologies and ADHD criteria limiting understanding of the relationship between early risk factors and later childhood ADHD. Using common methodology across six meta-analyses (Bitsko et al. in Prevention Science, 2022; Claussen et al. in Prevention Science 1–23, 2022; Dimitrov et al. in Prevention Science, 2023; Maher et al. in Prevention Science, 2023; Robinson, Bitsko et al. in Prevention Science, 2022; So et al. in Prevention Science, 2022) examining 59 risk factors for childhood ADHD, the papers in this special issue use a public health approach to address prior gaps in the literature. This introductory paper provides examples of comprehensive public health approaches focusing on policy, systems, and environmental changes across socio-ecological contexts to improve health and wellbeing through prevention, early intervention, and support across development using findings from these meta-analyses. Together, the findings from these studies and a commentary by an author independent from the risk studies have the potential to minimize risk conditions, prioritize prevention efforts, and improve the long-term health and wellbeing of children and adults with ADHD.

Keywords: ADHD, Meta-analysis, Risk factors, Public health

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a neurodevelopmental condition which can have significant negative consequences for long-term physical and mental health, including mortality (Barbaresi et al., 2013; Barkley & Dawson, 2022; Faraone et al., 2021). Risk for ADHD is likely multifactorial—with genetics playing a large role but a range of environmental risk factors (e.g., prenatal tobacco exposure and child maltreatment) interacting to increase the risk of ADHD, as well as the presence and severity of its symptoms (Faraone et al., 2021). Public health professionals can identify and help address these modifiable risk factors or exposures to improve health and wellbeing of people with ADHD. However, the evidence for such risk factors is spread among many disparate studies, and the relationship between early risk factors and later childhood ADHD remained unclear.

The six meta-analyses in this issue integrate widespread pieces of evidence for early risk associated with later ADHD diagnosis and symptom severity. A uniform methodology is applied across all the meta-analyses, summarizing evidence for the 59 prenatal and postnatal risk factors into a comprehensive set. The articles in this special issue along with a commentary from an author independent to the meta-analyses can help advance our understanding of modifiable risk factors for ADHD by enabling comparisons of different factors, and the relative strengths of those relationships, to better inform public health interventions and prioritization of public health resources.

Public Health, Economic, and Societal Impacts of ADHD

The need to address the risks for ADHD is underscored by its significant negative impacts on individuals and society. ADHD is one of the most common neurodevelopmental disorders, affecting approximately 1 in 9 children and adolescents (Danielson et al., in press), and although data on the national prevalence of adult ADHD are limited (Landes & London, 2021), core ADHD symptoms persist and wax and wane across the lifespan (Sibley et al., 2022; Turgay et al., 2012). ADHD symptomatology exists across a spectrum (Koi, 2021; Sonuga-Barke et al., 2023); depending on symptom severity and level of impairment, ADHD may qualify as a disability as defined by federal programs such as school accommodations from the Individuals with Disabilities Act or economic supports through the Supplemental Security Income program.

Individuals with an ADHD diagnosis, especially when untreated, are more likely to experience poor health outcomes, a shorter life expectancy, and greater direct health care costs and indirect costs related to health, education, and lost productivity compared to their peers without ADHD. Adverse outcomes include increased motor vehicle accidents, substance use disorder, suicidality, chronic diseases, and lower earning potential (Barkley & Dawson, 2022; Faraone et al., 2021; Nigg, 2013; Pelham et al., 2020; Sciberras et al., 2022). As such, the estimated economic and social costs of ADHD are as high as 12.76 billion dollars, using 2018–2019 data (Sciberras et al., 2022). Treatment options for ADHD can be complicated by treatment access, the burden of which is not equitably shared (Harati et al., 2020; Slobodin & Masalha, 2020). A 2023 National Academies public workshop called “Adult ADHD: Diagnosis, Treatment, and Implications for Drug Development” highlighted the clinical, research, and lived experience perspectives of ADHD which all converged on the same theme that the individual and societal costs of ADHD are profound and far-reaching (National Academies, 2023).

However, some aspects of ADHD can be adaptive in certain contexts and sources of resilience and strength for individuals with ADHD (Charabin et al., 2023; Sedgwick et al., 2019; Sherman et al., 2006). Therefore, identifying which children may be at greatest risk for ADHD and in what contexts can inform earlier intervention to reduce the impact of ADHD on individuals, families, schools, communities, and society (Sonuga-Barke et al., 2023).

What We Know About Risks Associated with ADHD

Published literature on potentially modifiable risk factors associated with ADHD have included chemical exposures, congenital and acquired physical health conditions, and psychosocial risk factors (Chandramouli et al., 2009; Hadzic et al., 2017; Nolin & Ethier, 2007). However, many studies rely on cross-sectional designs, which can lack the ability to adequately determine temporality of the exposure and the ADHD symptoms. Published studies also frequently rely on different measures of ADHD (e.g., symptom counts versus diagnostic cutoffs) or the risk factor of interest (e.g., parent report of exposure versus biological trace). As a result, individual studies can produce seemingly contradictory results, with studies of similar risk factors revealing different patterns of association with ADHD; for example, Pineda and colleagues (2007) identified an increased risk of pregnancy complications and childhood ADHD overall using retrospective parent report of pregnancy-related factors, while Getahun and colleagues (2013) found no significant association based on an analysis of medical records.

Conducting Comprehensive Meta-Analysis to Learn More About ADHD Risks

Meta-analysis capitalizes on the whole of the literature, aggregating findings from studies of similar risk factors to provide more stable estimates of association. Previous ADHD meta-analyses have been conducted separately for perinatal factors, chemical exposures, traumatic brain injury, and media use. However, conclusions from those meta-analyses are limited by the analytic decisions within them, such as including both longitudinal and cross-sectional studies (Nikkelen et al., 2014), including only studies of diagnosed ADHD (Adeyemo et al., 2014; Bhutta et al., 2002; Curran et al., 2015; Zhu et al., 2016), aggregating effect sizes from studies of diagnosed ADHD and ADHD symptoms (Hemmi et al., 2011; Yoshimasu et al., 2014), or aggregating effect sizes from studies of ADHD with studies of other behavior disorders (Rodríguez-Barranco et al., 2013). Although each of those meta-analyses is informative, the analytic decisions in each inherently limit which conclusions can be drawn about risk factors for ADHD and the comparisons that can be made across risk factors. For example, reliance only on studies examining the diagnosis of ADHD limits the identification of risk factors that may increase the severity or number of hyperactivity, impulsivity, and inattention symptoms, potentially missing opportunities for earlier intervention and preventing subthreshold ADHD to progressing into a disorder. Many unanswered questions about the relationship between early health experiences and ADHD as well as contradictions across studies leave individuals, providers, and decisionmakers with incomplete or inaccurate information about potential threats and early intervention opportunities for children’s behavioral health and neurodevelopment (Sonuga-Barke et al., 2023).

Common methodology across the six systematic reviews and meta-analyses in this special issue addresses previous gaps in the literature by identifying potentially modifiable risk factors for ADHD, separately by ADHD symptoms and diagnosis, and makes them comparable across risk factor categories. As such, these meta-analyses (Bitsko et al., 2022; Claussen et al., 2022; Dimitrov et al., 2023; Maher et al., 2023; Robinson, Bitsko et al., 2022; So et al., 2022) can inform public health efforts and resource allocation to decrease the prevalence of ADHD symptoms, the severity of those symptoms, the meeting of diagnostic criteria for ADHD, and/or impairment associated with disability among individuals with ADHD.

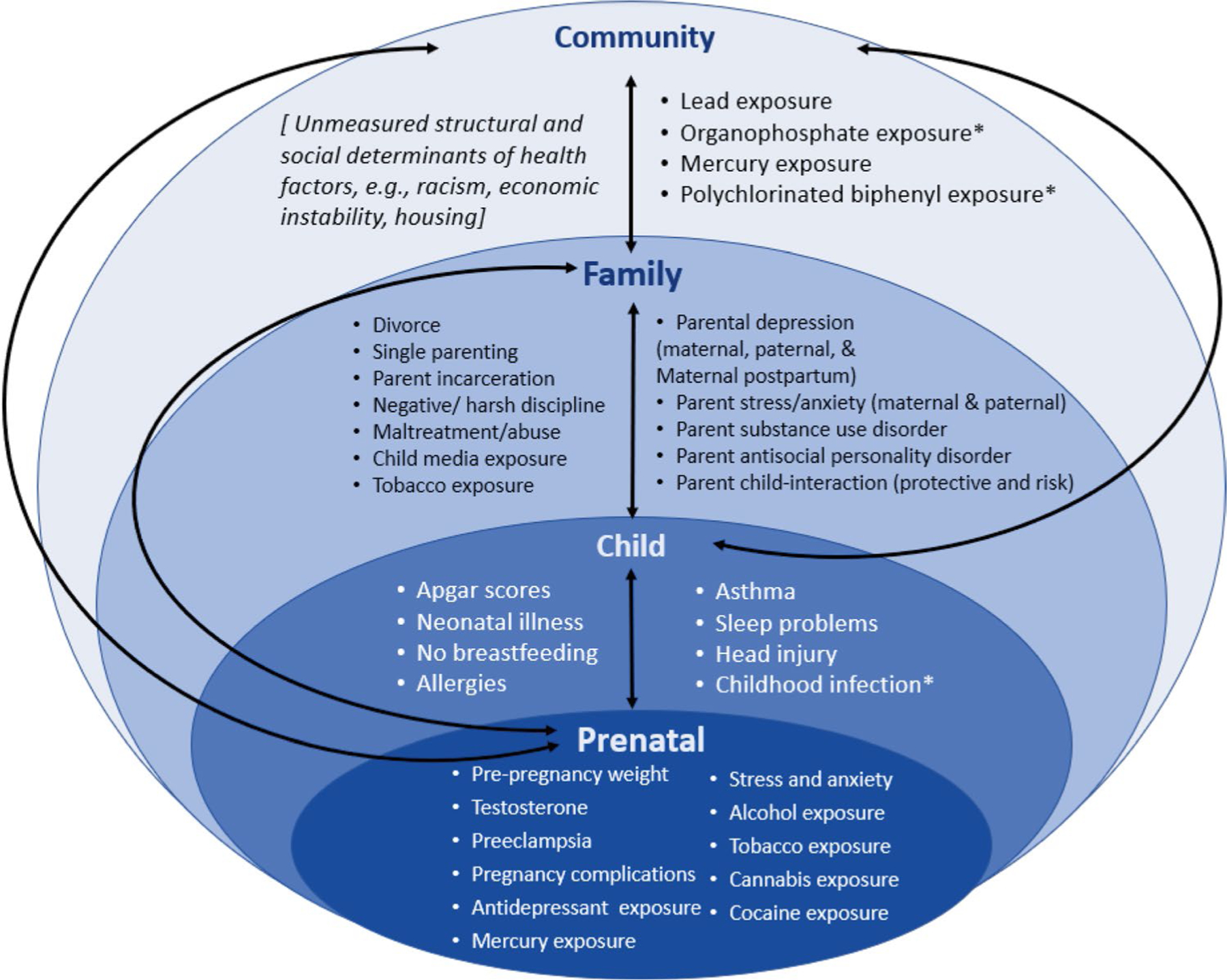

Collectively, these papers illustrate how ADHD may be affected by many different risk factors shared across socio-ecological contexts, without a single risk factor being determinative or the only important focus for prevention. Risk factors with significant associations with ADHD symptoms and/or diagnosis identified in these papers include exposures within the prenatal, child, family, and community ecological contexts, see Fig. 1 for all the significant risk factors for ADHD symptoms and/or diagnosis across the meta-analyses. Risk factors with the strongest effect sizes (e.g., odds ratios greater than 1.5 or correlation coefficients greater than 0.20) and/or significant associations across ADHD diagnosis and symptomatology measurement are prenatal exposures of maternal alcohol and tobacco use, maternal first trimester antidepressant use, and prenatal testosterone exposure (as measured by finger length ratio); child health factors such as the absence of breastfeeding, sleep problems, head injury, neonatal illness, and childhood infection (e.g., prenatally and postnatally, viral and bacterial); family factors that are associated with separation from a parent and may also be associated with family conflict or economic risk (e.g., divorce, single parenting, maltreatment, and physical abuse), media exposure, parental depression, parental stress and anxiety, parent substance use disorder, parent antisocial personality disorder; and community level exposures such as organophosphates and lead. The risks that rose to the top in these meta-analyses are factors that often overlap within and across socio-ecological contexts. A higher burden of many of these risk factors is often seen among Black, indigenous, people of color (BIPOC), and children in lower-income households (Evans et al., 2013; Le Menestrel & Duncan, 2019). Therefore, the role of social and structural determinants of health, such as racism, on the risks identified in this meta-analysis (e.g., parental incarceration and pregnancy complications) and the relevant strategies to address structural factors cannot be neglected (Malawa et al., 2021). The significant risk factors identified in these meta-analyses suggest varied mechanistic pathways of influence including inflammatory, neurobiological, and psychosocial interactional (Faraone & Larsson, 2019). While direct causal pathways are unknown, early contextual influences identified in these meta-analyses likely impact the genetic liability of ADHD, increasing symptom severity or crossing the impairment and symptom threshold to meet ADHD diagnostic criteria.

Fig. 1.

Significant potentially modifiable risk factors for childhood attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder within early development, across the six meta-analyses (Bitsko et al., 2022; Claussen et al., 2022; Dimitrov et al., 2023; Maher et al., 2023; Robinson, Bitsko et al., 2022; So et al., 2022) in this special issue

Note. *Some risk factors were significant only in combined or overall analyses which include both prenatal and postnatal measurement, in those cases they were placed in one socioecological context, if separate analyses for prenatal or postnatal measurement were significant, these risk factors were placed in each context they applied to.

Using Information About Risk to Inform Public Health Opportunities

A policy, systems, and environment (PSE) change approach focuses on changing the laws and policies, organizational rules, infrastructure, and physical and social contexts within which individuals live to support healthy behaviors (Eisenberg et al., 2021; Honeycutt et al., 2015). These approaches can address adversity and resilience across broader groups of populations, reducing social and structural barriers to individual behavior change for larger public health impacts (Frieden, 2010). The National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities’ Division of Human Development and Disability (DHDD) at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has embedded these PSE approaches in their strategic planning to support impactful interventions for people with disabilities and developmental concerns including ADHD. The significant risk factors identified by these meta-analyses suggest opportunities for a comprehensive public health approach focusing on PSE changes across socio-ecological contexts to improve health and wellbeing through prevention, early intervention, and support across development (Frieden, 2010). In the sections below, we highlight some examples of PSE approaches that address ADHD risks and support children and families.

PSE Opportunities for Integrated Perinatal Supports

We have long known that women’s health in the preconception and prenatal periods influences the health of their children. Bitsko et al. (2022), Maher et al. (2023), and Robinson, Bitsko et al. (2022) showed that many of the same risk factors associated with our maternal and infant mortality crisis (e.g., prenatal mental health, pregnancy complications, and maternal obesity) (Logue et al., 2022; Poston et al., 2016) may also increase the risk of ADHD among offspring. Strategies to support parenting by promoting parent’s physical and mental health, prenatally and postnatally, through integrated family health care approaches focusing on the health of the whole family unit can promote positive outcomes among children and families (Brundage & Shearer, 2019; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine, 2019). Many reasons exist to promote mental health and prevent or address substance use among women of reproductive age; possible ADHD risk reduction can also be added to the list. Moving upstream from the child, screening and intervention for adult ADHD at health care points of intervention (e.g., prenatal care, substance use intervention) may reduce other risk factors for ADHD, such as parental substance use and stress, and may also reduce future ADHD risk in children and influence intergenerational cycles (Crunelle et al., 2018; Jones et al., 2018).

PSE Opportunities for Child Health Promotion

Infant and child health exposures were also related to ADHD (e.g., neonatal illness, breastfeeding, head injury, childhood infection). Breastfeeding provides many well-documented health benefits for mom and baby, and interventions to improve breastfeeding rates may also be associated with reduced risk for ADHD symptoms and diagnosis (American Academy et al., 2012; Kramer & Kikuma, 2001). Healthcare systems approaches such as Baby Friendly Hospitals and Women Infants and Children (WIC) breastfeeding peer counseling as well as supportive policies in work and public places may improve breastfeeding rates, parent mental health, and the parent-child relationship (Robinson, Hutchins et al., 2022). Knowing that head injury may increase ADHD risk is another reason to promote car safety and educate parents, providers, and schools on concussion prevention through public health interventions such as CDC HEADS UP (Center for Disease Control & Prevention, 2022).

PSE Opportunities for Family Support

The papers by Claussen et al. (2022), Robinson, Hutchins et al. (2022), and Maher et al. (2023) found a number of parenting and family-level factors associated with ADHD such as parental mental health and stress, substance use, and maltreatment. If child-serving healthcare providers are aware of the relationship between these family-level factors and ADHD, they can better assess, monitor, and identify opportunities for targeted prevention. With continued work to better understand risk and resilience, providers can become familiar with risk factors identified in these papers and monitor developmental milestones through parent-engaged developmental surveillance using tools like ones from the Learn the Signs. Act Early. program (Center for Disease Control & Prevention, 2023) and screen for ADHD if concerns arise. Early intervention includes evidence-based behavioral parent training as the first-line treatment for young children with ADHD (Wolraich et al., 2019).

Prevention of risk is also important. For example, while access can be challenging, effective pharmacological and behavioral treatments exist for parents with mental health and substance use disorders, and the small literature examining the integration of parenting supports with substance abuse intervention shows promise (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine, 2019). Broader policy and systems level supports that intervene on social determinants of health can help to address family-level stressors and social and structural determinants of health such as income instability, housing instability, health care access, and food insecurity. Programs like Earned Income Tax Credits (Hamad & Rehkopf, 2016), family-friendly work policies (Robinson, Hutchins et al., 2022), and medical-legal partnerships (StreetCred, 2023) can promote child development by relieving parental stressors such as financial strain while expanding access to resources for basic health care and family needs. The above policy-level interventions have the potential to reduce the risk of child maltreatment and physical abuse, which were also strongly associated with ADHD risk in these meta-analyses and represent shared investments across multiple sectors and systems to support children and families (Forston et al., 2016).

PSE Opportunities for Community-Level Exposures

While identifying epidemiological associations between chemical exposures and health is challenging, the relationship between lead exposure and ADHD has been known for years (Advisory Committee for Childhood Lead Poisoning Prevention, 2012). No level of exposure to lead is safe, and even lower blood lead levels have been shown to increase attention-related behavioral problems; therefore, CDC describes blood lead levels of 3.5 μg/dL as the reference value (Binns et al., 2007; LEPAC, 2021). Lead exposure rates vary substantially across communities: however, BIPOC children and children in lower-income households remain at a greater risk (Teye et al., 2021). The proposed EPA Rule to remove lead-lined pipes in 10 years is promising (US Environmental Protection Agency, 2023). Housing Standards and Code Enforcement such as strengthening legal requirements related to lead hazards and healthy housing (Local Housing Solutions, n.d.) and creating a proactive rental inspection program (de Beaumont & Kaiser, 2022) may also help prevent lead exposures and subsequent child health risks.

Conclusion

ADHD is one of the most common neurodevelopmental disorders, affecting approximately 1 in 9 children and adolescents, and often continues into adulthood (Danielson et al., in press; Landes & London, 2021). ADHD is significantly impacted by genetic influences; ADHD traits are part of human diversity and may even be experienced as strengths depending on the individual and the social context (Koi, 2021; Sedgwick et al., 2019; Sherman et al., 2006). However, when symptoms are severe and cause impairment, and thus warrant a diagnosis of a disorder, public health is called to support individuals and families affected by ADHD, examine environmental factors that impact severity and impairment, reduce risks, and improve outcomes. While CDC’s DHDD continues to better measure and understand risk factors across the lifespan for individuals with ADHD, we are also implementing a PSE approach to promote the implementation of interventions that protect the brains of our children by limiting risk factors identified here along with maximizing protective influences. The identification of potentially modifiable ADHD risk factors can inform efforts to prevent the onset of, reduce the severity of, and mitigate the persistence of ADHD. Using the findings of the papers in this special issue, a public health socioecological approach leveraging PSE strategies has the potential to minimize risk conditions, target prevention efforts, and improve the long-term health and wellbeing of children and adults with ADHD.

Funding

The meta-analyses summarized here were completed through an Interagency agreement between the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the General Service Administration (13-FED-1303304). The work was completed under GSA Order Number ID04130157 to Gryphon Scientific, LLC, titled “Identifying Public Health Strategies with Potential for Reducing Risk for Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorder.”

Footnotes

The findings and conclusions in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Declarations

Ethics Approval Not applicable. This manuscript is a summary of data from six published meta-analyses.

Consent to Participate Not applicable.

Conflict of Interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Adeyemo BO, Biederman J, Zafonte R, Kagan E, Spencer TJ, Uchida M, Kenworthy T, Spencer AE, & Faraone SV (2014). Mild traumatic brain injury and ADHD: A systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis. Journal of Attention Disorders, 18(7), 576–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Advisory Committee for Childhood Lead Poisoning Prevention of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2012). Low level lead exposure harms children: A renewed call for primary prevention. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/147833 [Google Scholar]

- American Academy of P, Eidelman AI, Schanler RJ, Johnston M, Landers S, Noble L, Szucs K, & Viehmann L (2012). Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics, 129(3), e827–e841. 10.1542/peds.2011-3552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbaresi WJ, Colligan RC, Weaver AL, Voigt RG, Killian JM, & Katusic SK (2013). Mortality, ADHD, and psychosocial adversity in adults with childhood ADHD: A prospective study. Pediatrics, 131(4), 637–644. 10.1542/peds.2012-2354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkley RA, & Dawson G (2022). Higher risk of mortality for individuals diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder or attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder demands a public health prevention strategy. JAMA Pediatrics, 176(4), e216398. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.6398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhutta AT, Cleves MA, Casey PH, Cradock MM, & Anand KJS (2002). Cognitive and behavioral outcomes of school-aged children who were born preterm: A meta-analysis. JAMA, 288(6), 728–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binns HJ, Campbell C, Brown MJ, Advisory Committee, C. D. C., & on Childhood Lead Poisoning. (2007). Interpreting and managing blood lead levels of less than 10 μg/dL in children and reducing childhood exposure to lead: Recommendations of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Advisory Committee on Childhood Lead Poisoning Prevention. Pediatrics, 120(5), e1285–e1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitsko RH, Holbrook JR, O’Masta B, Maher B, Cerles A, Saadeh K, Mahmooth Z, MacMillan LM, Rush M, & Kaminski JW (2022). A systematic review and meta-analysis of prenatal, birth, and postnatal factors associated with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children. Prevention Science. 10.1007/s11121-022-01359-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brundage SC, & Shearer C (2019). Plan and provider opportunities to move toward integrated family health care. United Hospital Fund. https://uhfnyc.org/publications/publication/plan-and-provider-opportunities-move-toward-integrated-family-health/ [Google Scholar]

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022, February 25). Heads up. https://www.cdc.gov/headsup/index.html [Google Scholar]

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023, June 6). Learn the signs. Act early. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/actearly/index.html [Google Scholar]

- Chandramouli K, Steer CD, Ellis M, & Emond AM (2009). Effects of early childhood lead exposure on academic performance and behaviour of school age children. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 94(11), 844–848. 10.1136/adc.2008.149955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charabin E, Climie EA, Miller C, Jelinkova K, & Wilkins J (2023). “I’m doing okay”: Strengths and resilience of children with and without ADHD. Journal of Attention Disorders, 27(9), 1009–1019. 10.1177/10870547231167512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claussen AH, Holbrook JR, Hutchins HJ, Robinson LR, Bloomfield J, Meng L, Bitsko RH, O’Masta B, Cerles A, & Maher B (2022). All in the family? A systematic review and meta-analysis of parenting and family environment as risk factors for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in children. Prevention Science, 1–23. 10.1007/s11121-022-01358-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crunelle CL, van den Brink W, Moggi F, Konstenius M, Franck J, Levin FR, van de Glind G, Demetrovics Z, Coetzee C, Luderer M, Schellekens A, & Icasa consensus group, & Matthys F. (2018). International consensus statement on screening, diagnosis and treatment of substance use disorder patients with comorbid attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. European Addiction Research, 24(1), 43–51. 10.1159/000487767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran EA, O’Neill SM, Cryan JF, Kenny LC, Dinan TG, Khashan AS, & Kearney PM (2015). Research review: Birth by caesarean section and development of autism spectrum disorder and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 56(5), 500–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danielson M, Claussen AH, Bitsko RH, Katz S, Newsome K, Blumberg SJ, Kogan MD, & Ghandour R (in press). ADHD Prevalence among U.S. children and adolescents in 2022: Diagnosis, severity, co-occurring disorders, and treatment. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Beaumont F, & Kaiser P (2022). Addressing America’s housing crisis three local policy solutions to promote health and equity in housing (City Health, Issue). https://debeaumont.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/CityHealth-Report-Addressing-Americas-Housing-Crisis.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Dimitrov LV, Kaminski JW, Holbrook JR, Bitsko RH, Yeh M, Courtney JG, O’Masta B, Maher B, Cerles A, McGowan K, & Rush M (2023). A systematic review and meta-analysis of chemical exposures and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children. Prevention Science. 10.1007/s11121-023-01601-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg Y, Vanderbom KA, Harris K, Herman C, Hefelfinger J, & Rauworth A (2021). Evaluation of the reaching people with disabilities through healthy communities project. Disability and Health Journal, 14(3), 101061. 10.1016/j.dhjo.2021.101061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans GW, Li D, & Whipple SS (2013). Cumulative risk and child development. Psychological Bulletin, 139(6), 1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faraone SV, Banaschewski T, Coghill D, Zheng Y, Biederman J, Bellgrove MA, Newcorn JH, Gignac M, Al Saud NM, & Manor I (2021). The world federation of ADHD international consensus statement: 208 evidence-based conclusions about the disorder. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 128, 789–818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faraone SV, & Larsson H (2019). Genetics of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Molecular Psychiatry, 24(4), 562–575. 10.1038/s41380-018-0070-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forston BL, Klevens J, Merrick MT, Gilbert LK, & Alexander SP (2016). Child abuse and neglect prevention resource for action: A compilation of the best available evidence. CDC. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/38864 [Google Scholar]

- Frieden TR (2010). A framework for public health action: The health impact pyramid. American Journal of Public Health, 100(4), 590–595. 10.2105/ajph.2009.185652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Getahun D, Rhoads GG, Demissie K, Lu S-E, Quinn VP, Fassett MJ, Wing DA, & Jacobsen SJ (2013). In utero exposure to ischemic-hypoxic conditions and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics, 131(1), e53–e61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadzic E, Sinanovic O, & Memisevic H (2017). Is bacterial meningitis a risk factor for developing attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Israel Journal of Psychiatry, 54(2), 54–57. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/29248907 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamad R, & Rehkopf DH (2016). Poverty and child development: A longitudinal study of the impact of the earned income tax credit. American Journal of Epidemiology, 183(9), 775–784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harati PM, Cummings JR, & Serban N (2020). Provider-level caseload of psychosocial services for medicaid-insured children. Public Health Reports, 135(5), 599–610. 10.1177/0033354920932658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemmi MH, Wolke D, & Schneider S (2011). Associations between problems with crying, sleeping and/or feeding in infancy and long-term behavioural outcomes in childhood: A meta-analysis. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 96(7):622–9. 10.1136/adc.2010.191312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honeycutt S, Leeman J, McCarthy WJ, Bastani R, Carter-Edwards L, Clark H, Garney W, Gustat J, Hites L, & Nothwehr F (2015). Peer reviewed: Evaluating policy, systems, and environmental change interventions: Lessons learned from CDC’s prevention research centers. Preventing Chronic Disease, 12,150281. 10.5888/pcd12.150281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones HA, Eddy LD, Rabinovitch AE, Snipes DJ, Wilson SA, Parks AM, Karjane NW, & Svikis DS (2018). Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptom clusters differentially predict prenatal health behaviors in pregnant women. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 74(4), 665–679. 10.1002/jclp.22538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koi P (2021). Genetics on the neurodiversity spectrum: Genetic, phenotypic and endophenotypic continua in autism and ADHD. Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part A, 89, 52–62. 10.1016/j.shpsa.2021.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer MS, & Kikuma R (2001). The optimal duration of exclusive breastfeeding: Report of an expert consultation. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2012(8), CD003517. 10.1002/14651858.CD003517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landes SD, & London AS (2021). Self-reported ADHD and adult health in the United States. Journal of Attention Disorders, 25(1), 3–13. 10.1177/1087054718757648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEPAC. (2021). Lead Exposure and Prevention Advisory Committee (LEPAC) Meeting – May 14, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/nceh/lead/advisory/lepac-meeting-5-14-21.html [Google Scholar]

- Local Housing Solutions. (n.d.). Housing and building codes. Abt Associates and NYU Furman Center. https://localhousingsolutions.org/housing-policy-library/housing-and-building-codes/ [Google Scholar]

- Logue TC, Wen T, Monk C, Guglielminotti J, Huang Y, Wright JD, D’Alton ME, & Friedman AM (2022). Trends in and complications associated with mental health condition diagnoses during delivery hospitalizations. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 226(3), 405.e401–405.e416. 10.1016/j.ajog.2021.09.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maher BS, Bitsko RH, Claussen AH, O’Masta B, Cerles A, Holbrook JR, Mahmooth Z, Chen-Bowers N, Rojo ALA, Kaminski JW, & Rush M (2023). Systematic review and meta-analysis of the relationship between exposure to parental substance use and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children. Prevention Science. 10.1007/s11121-023-01605-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malawa Z, Gaarde J, & Spellen S (2021). Racism as a root cause approach: A new framework. Pediatrics, 147(1). 10.1542/peds.2020-015602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Academies. (2023). Adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: Diagnosis, treatment, and implications for drug development - A workshop. [Google Scholar]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education; Board on Children, Youth, and Families; Committee on Fostering Healthy Mental, Emotional, and Behavioral Development Among Children and Youth. Fostering Healthy Mental, Emotional, and Behavioral Development in Children and Youth: A National Agenda. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2019. Sep 11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education; Committee on National Statistics; Board on Children, Youth, and Families; Committee on Building an Agenda to Reduce the Number of Children in Poverty by Half in 10 Years. A Roadmap to Reducing Child Poverty. Le Menestrel S, Duncan G, editors. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2019. Feb 28. Copy Download .nbib. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nigg J (2013). Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and adverse health outcomes [review]. Clinical Psychology Review, 33(2), 215–228. 10.1016/j.cpr.2012.11.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikkelen SWC, Valkenberg PM, Huizinga M, & Bushman BJ (2014) Media use and ADHD-related behaviors in children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. Developmental Psychology, 50(9), 2228–2241. 10.1037/a0037318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolin P, & Ethier L (2007). Using neuropsychological profiles to classify neglected children with or without physical abuse. Child Abuse & Neglect, 31(6), 631–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelham WEI, Page TF, Altszuler AR, Gnagy EM, Molina BSG, & Pelham WE Jr. (2020). The long-term financial outcome of children diagnosed with ADHD. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 88(2), 160–171. 10.1037/ccp0000461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pineda DA, Palacio LG, Puerta IC, Merchán V, Arango CP, Galvis AY, Gómez M, Aguirre DC, Lopera F, & Arcos-Burgos M (2007). Environmental influences that affect attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: Study of a genetic isolate. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 16, 337–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poston L, Caleyachetty R, Cnattingius S, Corvalán C, Uauy R, Herring S, & Gillman MW (2016). Preconceptional and maternal obesity: Epidemiology and health consequences. The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology, 4(12), 1025–1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson LR, Bitsko RH, O’Masta B, Holbrook JR, Ko J, Barry CM, Maher B, Cerles A, Saadeh K, MacMillan L, Mahmooth Z, Bloomfield J, Rush M, & Kaminski JW (2022). A systematic review and meta-analysis of parental depression, antidepressant usage, antisocial personality disorder, and stress and anxiety as risk factors for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in children. Prevention Science. 10.1007/s11121-022-01383-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson LR, Hutchins HJ, Hulkower R, Newsome K, Claussen AH, Bitsko RH, McCord R, & Kaminski JW (2022). Bolstering the bond: Policies and programs that support prenatal bonding and the transition to parenting. In M. AS Smith JM (Ed.), The Cambridge Handbook of Parenting Interdisciplinary Application and Research. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Barranco M, Lacasaña M, Aguilar-Garduño C, Alguacil J, Gil F, González-Alzaga B, & Rojas-García A (2013). Association of arsenic, cadmium and manganese exposure with neurodevelopment and behavioural disorders in children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Science of the Total Environment, 454–455, 562–577. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.03.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sciberras E, Streatfeild J, Ceccato T, Pezzullo L, Scott JG, Middeldorp CM, Hutchins P, Paterson R, Bellgrove MA, & Coghill D (2022). Social and economic costs of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder across the lifespan. Journal of Attention Disorders, 26(1), 72–87. 10.1177/1087054720961828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedgwick JA, Merwood A, & Asherson P (2019). The positive aspects of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: A qualitative investigation of successful adults with ADHD. ADHD Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorders, 11(3), 241–253. 10.1007/s12402-018-0277-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman J, Rasmussen C, & Baydala L (2006). Thinking positively: How some characteristics of ADHD can be adaptive and accepted in the classroom. Childhood Education, 82(4), 196–200. [Google Scholar]

- Sibley MH, Arnold LE, Swanson JM, Hechtman LT, Kennedy TM, Owens E, Molina BSG, Jensen PS, Hinshaw SP, & Roy A (2022). Variable patterns of remission from ADHD in the multimodal treatment study of ADHD. American Journal of Psychiatry, 179(2), 142–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slobodin O, & Masalha R (2020). Challenges in ADHD care for ethnic minority children: A review of the current literature. Transcultural Psychiatry, 57(3), 468–483. 10.1177/1363461520902885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- So M, Dziuban EJ, Pedati CS, Holbrook JR, Claussen AH, O’Masta B, Maher B, Cerles AA, Mahmooth Z, MacMillan L, Kaminski JW, & Rush M (2022). Childhood physical health and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis of modifiable factors. Prevention Science. 10.1007/s11121-022-01398-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonuga-Barke EJS, Becker SP, Bölte S, Castellanos FX, Franke B, Newcorn JH, Nigg JT, Rohde LA, & Simonoff E (2023). Annual research review: Perspectives on progress in ADHD science – From characterization to cause. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 64(4), 506–532. 10.1111/jcpp.13696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- StreetCred. (2023). Integrating an economic bundle into pediatric primary care: An evidence-based approach to improving child health. Boston Medical Center Health System. https://www.mystreetcred.org/files/Economic-bundle-white-paper_FINALFINAL.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Turgay A, Goodman DW, Asherson P, Lasser RA, Babcock TF, Pucci ML, Barkley R, & Group ATPMW (2012). Lifespan persistence of ADHD: The life transition model and its application. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 73(2), 10337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teye SO, Yanosky JD, … & Cuffee Y (2021). Exploring persistent racial/ethnic disparities in lead exposure among American children aged 1–5 years: results from NHANES 1999–2016. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health, 94, 723–730. 10.1007/s00420-020-01616-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Environmental Protection Agency. (2023). National Primary Drinking Water Regulations for Lead and Copper: Improvements (LCRI), EPA-HQ-OW-2022-0801. Federal Register, 88, FR 84878, 84878–85090. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2023/12/06/2023-26148/national-primary-drinking-water-regulations-for-lead-and-copper-improvements-lcri [Google Scholar]

- Wolraich ML, Hagan JF, Allan C, Chan E, Davison D, Earls M, Evans SW, Flinn SK, Froehlich T, & Frost J (2019). Clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. Pediatrics, 144(4). 10.1542/peds.2019-2528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimasu K, Kiyohara C, Takemura S, & Nakai K (2014). A meta-analysis of the evidence on the impact of prenatal and early infancy exposures to mercury on autism and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder in the childhood. NeuroToxicology, 44, 121–131. 10.1016/j.neuro.2014.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu T, Gan J, Huang J, Li Y, Qu Y, & Mu D (2016). Association between perinatal hypoxic-ischemic conditions and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A meta-analysis. Journal of Child Neurology, 31(10), 1235–1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]