Abstract

Interleaflet coupling—the influence of one leaflet on the properties of the opposing leaflet—is a fundamental plasma membrane organizational principle. This coupling is proposed to participate in maintaining steady-state biophysical properties of the plasma membrane, which in turn regulates some transmembrane signaling processes. A prominent example is antigen (Ag) stimulation of signaling by clustering transmembrane receptors for immunoglobulin E (IgE), FcεRI. This transmembrane signaling depends on the stabilization of ordered regions in the inner leaflet for sorting of intracellular signaling components. The resting inner leaflet has a lipid composition that is generally less ordered than the outer leaflet and that does not spontaneously phase separate in model membranes. We propose that interleaflet coupling can mediate ordering and disordering of the inner leaflet, which is poised in resting cells to reorganize upon stimulation. To test this in live cells, we first established a straightforward approach to evaluate induced changes in membrane order by measuring inner leaflet diffusion of lipid probes by imaging fluorescence correlation spectroscopy, by imaging fluorescence correlation spectroscopy (ImFCS), before and after methyl-α-cyclodexrin (mαCD)-catalyzed exchange of outer leaflet lipids (LEX) with exogenous order- or disorder-promoting phospholipids. We examined the functional impact of LEX by monitoring two Ag-stimulated responses: recruitment of cytoplasmic Syk kinase to the inner leaflet and exocytosis of secretory granules (degranulation). Based on the ImFCS data in resting cells, we observed global increase or decrease of inner leaflet order when outer leaflet is exchanged with order- or disorder-promoting lipids, respectively. We find that the degree of both stimulated Syk recruitment and degranulation correlates positively with LEX-mediated changes of inner leaflet order in resting cells. Overall, our results show that resting-state lipid ordering of the outer leaflet influences the ordering of the inner leaflet, likely via interleaflet coupling. This imposed lipid reorganization modulates transmembrane signaling stimulated by Ag clustering of IgE-FcεRI.

Significance

Coupling between plasma membrane leaflets, which are biochemically and biophysically asymmetric, results in a steady-state membrane organization that is thought to play fundamental roles in cellular homeostasis and stimulated responses. Here, we present a straightforward approach built around mαCD-catalyzed lipid exchange (LEX) and imaging fluorescence correlation spectroscopy (ImFCS) to quantitatively characterize a novel, lipid-driven, interleaflet coupling mechanism and its functional impact in live mast cells. We showed that elevation of outer leaflet lipid order induces ordering throughout the inner leaflet in resting cells. This ordering enhances protein-based reactions during Ag-stimulated FcεRI signaling and consequent cellular responses. Overall, we provide compelling evidence for functional relevance of organizational heterogeneity in plasma membranes driven by lipid-based interleaflet coupling.

Introduction

A collective of lipid-based and protein-based interactions simultaneously contribute to the steady-state biophysical properties of plasma membrane of living cells (1). For example, the outer leaflet of resting plasma membrane with a large abundance of saturated lipids is more ordered than the inner leaflet where the lipids generally have higher degree of unsaturation (2). This is also reflected in the capacity of phase separation into liquid ordered and disordered regions in model membranes mimicking lipid compositions corresponding to these leaflets. In model lipid membrane studies a minimal lipid composition mimicking the outer leaflet shows phase separation, while the same for the inner leaflet shows no phase separation (3). Interestingly, recent studies on live cells showed that phase-like separation into coexisting ordered and disordered regions in the inner leaflet is stabilized when some immunoreceptors are stimulated by extracellular cross-linking (4). This stabilization in turn plays a decisive role in functional transmembrane (TM) signaling mediated by these receptors. Examples include TM signaling through B cell receptors and the high affinity receptor for immunoglobulin E (IgE), FcεRI in mast cells (5,6,7). This means that the inner leaflet of live cell membranes may undergo phase-like organization in some conditions.

Inner leaflet lipid probes having saturated and unsaturated acyl chain anchors, namely enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP)-tagged palmitoyl/myristoyl (PM) lipid chain (PM-EGFP) and EGFP-tagged geranylgeranyl lipid chain (EGFP-GG), respectively, have proven valuable for examining heterogeneous lipid environments. These two plasma membrane probes showed modestly different (but statistically significant) average diffusion coefficients (Dav) (8) in resting rat basophilic leukemia (RBL) cells as measured by total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy (TIRFM)-based imaging fluorescence correlation spectroscopy (ImFCS) (9,10). A slightly faster Dav for EGFP-GG is consistent with the partitioning preferences of PM-EGFP and EGFP-GG (into the ordered and disordered regions, respectively) in phase-separated model membranes and suggests that the inner leaflet of resting cells has some phase-like behavior (11,12). Interestingly, the Dav value of PM-EGFP decreases by ∼7% and that of EGFP-GG increases by 10% when RBL cells are stimulated by antigen (Ag) cross-linking of IgE-bound FcεRI receptors (6). This contrasting diffusion behavior of the order- and disorder-preferring probes indicates the stabilization of phase-like organization in the inner leaflet after stimulation. Along the same line, Shelby et al. used super-resolution localization microscopy to show nanoscale colocalization between PM probe and Ag-clustered IgE-FcεRI, whereas the GG probe did not show any detectable colocalization under the same conditions (7). Overall, these consistent results from independent approaches show that the inner leaflet of the plasma membrane has the capacity to exhibit phase-like organization into ordered and disordered regions. Such organization is likely to be highly dynamic and transient in resting steady state, consistent with only marginal differences in the diffusion properties of the lipid probes of contrasting phase preference. This dynamism of phase-like organization in the resting steady state confers the capacity of the inner leaflet to rapidly reorganize into another dynamic steady state when responding to an external stimulus. In other words, the resting state of the plasma membrane inner leaflet is poised to undergo reorganization with modulated phase-like separation, which is shown to play decisive roles in biological functions.

Two biophysical models, which may not be mutually exclusive, underlying ordered/disordered phase-like separation in the inner leaflet of live cell plasma membranes have been recently proposed. First, the Mayor group proposed an interleaflet coupling mechanism formed by clustering of dynamic actin filaments and interdigitation of long-chain inner leaflet phosphatidylserine lipids with long-chain outer leaflet phospholipids leading to an ordered environment around this cluster (13). The second model is actin-independent interdigitation of lipid chains where the lipid distribution alone or clustering of lipids or lipid-anchored proteins in the outer leaflet changes and consequently induces inner leaflet phase separation (14,15,16).

Of particular interest is the series of recent experiments in lipid bilayers demonstrating that lipid compositional asymmetry, which is commonly maintained in live cells (17,18), may drive phase separation in the inner leaflet (19,20). Simply, ordered/disordered phase-like separation in outer leaflet lipids can induce phase-like separation in the inner leaflet. On the other hand, under some conditions, signal transduction is associated with a loss of lipid asymmetry (21), and a loss of lipid asymmetry may induce ordered domain formation in the inner leaflet, as shown in model lipid bilayers (22) and cell-derived giant plasma membrane vesicle (GPMV) (23) systems. While GPMVs are a very useful cell-derived model system to study membrane organization, they lack a cortical actin cytoskeleton and suffer from loss of compositional asymmetry to some degree (23). A systematic live cell study on this biophysical coupling between the leaflets and its physiological implications therefore remains highly desirable.

To evaluate the degree of interleaflet coupling resulting from lipid compositional asymmetry, we modify the outer leaflet lipid composition by methyl-α-cyclodextrin (mαCD)-catalyzed lipid exchange (LEX) (24,25) and monitor the corresponding changes of diffusion properties in the inner leaflet (Fig. 1). In this LEX process, a selected exogenous lipid (Lipidex) is complexed with a molar excess of mαCD in solution. This mixture is added to replace endogenous lipids which form complexes with the excess (uncomplexed) mαCD while the Lipidex (initially complexed with mαCD) is transferred to the outer leaflet. Further investigations (25) show that the Lipidex remains in the outer leaflet for a sufficiently long time (∼2 h) to allow biophysical and functional measurements. The efficiency of the LEX method has so far been characterized in several cell types (reviewed in (26)). It has been shown that ∼50–100% of endogenous phospholipids in the plasma membrane outer leaflet (and likely that of membrane compartments rapidly cycling to and from the plasma membrane (27)) may be exchanged by this method without significantly compromising cell health as judged from no change in cell morphology and membrane integrity (24,25). These results motivated us to use LEX to easily change outer leaflet lipid composition and test its interleaflet effects in live cells.

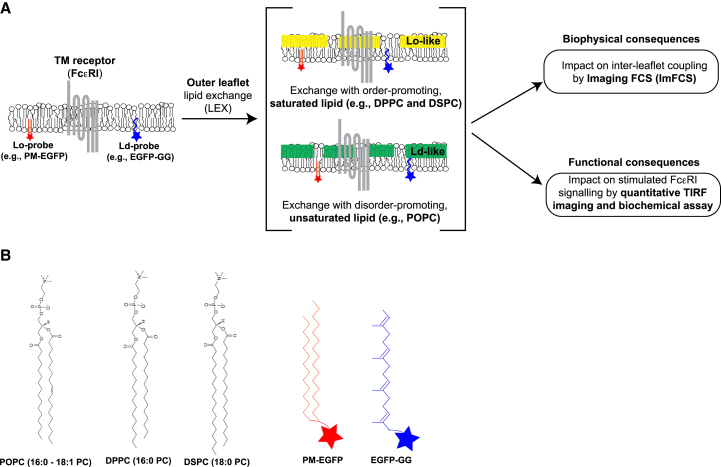

Figure 1.

Interleaflet coupling of cellular plasma membrane can be evaluated by exchanging outer leaflet lipids and monitoring consequences. (A) Experimental strategy to perform mαCD-catalyzed outer leaflet lipid exchange (LEX) with exogenous lipid (Lipidex) and evaluate its biophysical and functional consequences. In this schematic, the size of the probes and receptors are not drawn to relative scale and their respective phase preference are not strictly considered. The schematic serves as a visual guide for the transmembrane (for FcεRI) and inner leaflet (PM-EGFP and EGFP-GG) localization of the membrane components. (B) Chemical structures of Lipidex and fluorescent inner leaflet lipid probes used in this study. The lipid structures are taken from the Avanti Polar Lipids web site. To see this figure in color, go online.

Modulation of phase-like organization in the inner leaflet due to the LEX-based perturbations in the outer leaflet can be evaluated from the corresponding changes in the diffusion of inner leaflet lipid probes. To detect subtle changes in phase-like organization in the plasma membrane, we recently developed a highly robust experimental strategy based around precise (standard error of mean < 1%) diffusion coefficient (D) measurements of passive (nonfunctional) lipid probes by ImFCS (6,8). ImFCS measures several thousands of D values from multiple cells under a set condition. The entire pool of D values is used to compare the difference of diffusion coefficients across experimental conditions (e.g., Ag-stimulated versus unstimulated conditions as in (6)), while the consistency of D values across cells is confirmed by bootstrapping (6). The statistical robustness of ImFCS data previously permitted us to detect subtle changes of D values of the lipid probes (PM-EGFP and EGFP-GG) due to various perturbations including Ag cross-linking of IgE-FcεRI complex (6), inhibition of actin polymerization (8), and antibody cross-linking of outer leaflet gangliosides (28) in live RBL mast cells.

Here, we use the same ImFCS strategy to investigate the modulation of phase-like organization in the inner leaflet due to LEX of outer leaflet lipids in resting RBL cells. We evaluate the diffusion properties of inner leaflet probes PM-EGFP and EGFP-GG when outer leaflet lipid composition is exchanged with order-promoting saturated Lipidex including 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DPPC) and 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DSPC), or disorder-promoting unsaturated Lipidex, 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-glycero-3-phosphocholine (POPC)(29). We observe that high concentrations of these order- and disorder-promoting Lipidex species in the outer leaflet, respectively, decrease and increase diffusion coefficients for both PM-EGFP and EGFP-GG. This correlation reveals that the two leaflets of the plasma membrane are biophysically coupled and the outer leaflet lipid substitution by LEX method induces global changes in the inner leaflet.

Since plasma membrane heterogeneity in the resting state of untreated cells is poised to respond to Ag stimulation, it is essential to test the effects of LEX in resting conditions on the functional consequences in stimulated FcεRI signaling. To accomplish phosphorylation of Ag-cross-linked FcεRI receptors above nonfunctional threshold, receptor phosphorylation by Lyn kinase, an inner leaflet, lipid-anchored protein, must outperform its dephosphorylation by TM phosphatases. When the Ag is presented as surface bound (such as embedded in a lipid bilayer), a kinetic segregation mechanism has been proposed (30). In this model, the TM phosphatases are excluded from the Ag-engaged receptors by the steric hindrance of closely opposed surfaces while Lyn kinase does not encounter such hindrance due to its localization in the inner leaflet. However, this type of kinetic segregation seems unlikely when soluble Ag is used to stimulate the receptor. As described above (and summarized in (6)), cross-linking of IgE-FcεRI by soluble Ag stabilizes ordered regions around the receptor clusters. This increases the probability of interactions between the cross-linked receptors and Lyn kinase, a cytoplasmic protein anchored to the plasma membrane by saturated PM acyl chains, which preferentially partitions into the ordered lipid regions. In contrast, TM phosphatases are excluded from the vicinity of the cross-linked TM receptors due in part to their preference for disordered regions (6). Thus, the net stabilization of ordered regions around Ag cross-linked receptors enhances the probability of Lyn/FcεRI interactions while suppressing phosphatase/FcεRI interactions, thereby tipping the receptor phosphorylation/dephosphorylation balance toward net phosphorylation. This spatial organization of the receptor, kinase, and phosphatase in stimulated steady state ensures the receptor phosphorylation level to be above the nonfunctional threshold as required to commence downstream signaling. Lyn-phosphorylated FcεRI recruits cytosolic Syk kinase to the plasma membrane (31). Syk phosphorylation of its substrates yields a cascade of downstream signaling reactions eventually leading to cellular degranulation, i.e., exocytosis of secretory granules containing β-hexosaminidase and other chemical mediators. To evaluate the functional consequences of LEX in resting cells and lipid-based interleaflet coupling we monitor modulation of stimulated Syk recruitment (early signaling event) and degranulation (ultimate cellular response). Although our results show global rather than local effects on ordering in the inner leaflet, there is a clear positive correlation between LEX-induced changes in the inner leaflet order in the resting state and these two stimulated functional events. Overall, this study provides novel evidence for interleaflet coupling in the plasma membranes of live cells with functional relevance.

Materials and methods

Reagents

Minimum essential medium (MEM), Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM), Opti-MEM, Trypsin-EDTA (0.01%), and gentamicin sulfate were purchased from Life Technologies (Carlsbad, CA). Fetal bovine serum was purchased from Atlanta Biologicals (Atlanta, GA). Alexa Fluor 488 (AF488) NHS ester (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA) was used to fluorescently label monoclonal anti-DNP (2,4-dinitrophenyl) IgE yielding AF488-IgE as described previously (27). The multivalent Ag, DNP-BSA, was prepared by conjugating DNP sulfonate (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) to bovine serum albumin (BSA) (32) yielding an average of 15 DNP molecules per BSA (7). mαCD was purchased from AraChem (Tilburg, the Netherlands). The stock solution of mαCD was prepared in Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline buffer and stored at 4°C. Phorbol 12,13-dibutyrate was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Stock solution of phorbol 12,13-dibutyrate was prepared in DMSO and stored at −80°C. All lipids were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL) in chloroform stock solution.

Cell culture, chemical transfection, sensitization, and stimulation

Both wild-type and Syk-negative RBL cells derived from the parental line (33) were grown and maintained in culture medium containing 80% MEM, 20% fetal bovine serum, and 10 mg/L gentamicin sulfate at 37°C and 5% (v/v) CO2 environment. Both cell lines were transfected using the FuGENE HD transfection kit (Promega, Madison, WI). The details of the transfection protocol are described elsewhere (6). The chemically transfected plasmids used in this study encode the following proteins: PM-EGFP (34), EGFP-GG (34), and YFP-Syk (35).

All ImFCS experiments were done in resting cells, while the functional assays (YFP-Syk recruitment and degranulation) were done on cells with and without stimulation. We describe the sensitization and stimulation conditions for the functional assays below.

For YFP-Syk recruitment assay, YFP-Syk-expressing cells were incubated overnight in a 35 mm glass-bottomed dish (MatTek, Ashland, MA) with 0.5 μg/mL anti-DNP IgE at 37°C and 5% (v/v) CO2 environment followed by LEX in room temperature for 1 h (details of the LEX protocol are given in the following sections). After LEX, these cells were stimulated with 0.5 μg/mL DNP-BSA at room temperature, and time-lapse TIRFM imaging (see below for the imaging setup) was done right after addition.

For degranulation experiments, cells were incubated in a 96-well plate. The conditions of IgE sensitization and LEX were same as above (for YFP-Syk recruitment assay). These cells were stimulated with 0.01 μg/mL DNP-BSA for 1 h at 37°C. Degranulation of the cells was then measured by UV-vis spectroscopy using a standard assay (36).

Preparation of LEX working solution

This protocol and LEX (next section) are adopted from previously published reports (24,25,37). Appropriate volume of lipid (in chloroform) in a 5 mL glass vial was first dried under a nitrogen gas stream, followed by high vacuum for 1 h. For stock solution, the dried lipid film was then hydrated in 40 mM mαCD solution at 70°C for 5 min followed by at 55°C for 30 min. The lipid-exchange solution thus prepared was kept overnight at room temperature. The working solution of mαCD (40 mM) is prepared by diluting a stock solution (concentration: 380–480 mM prepared in Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline buffer) in serum-free DMEM right before addition to the lipid film. The final concentration of the lipids used were 3 mM POPC, 1.5 mM DPPC, and 1.5 mM DSPC.

Outer leaflet LEX in RBL cells

RBL cells grown to 80–90% confluency on a 35 mm glass-bottomed dish (MatTek; for ImFCS and YFP-Syk recruitment assay) or a 96-well plate (for degranulation assay) were washed twice with buffered saline solution (BSS) (135 mM NaCl, 5.0 mM KCl, 1.8 mM CaCl2, 1.0 mM MgCl2, 5.6 mM glucose, and 20 mM HEPES [pH 7.4]) and then incubated at room temperature for 45 min in fresh BSS. After this, for cells in the glass-bottomed dish, BSS was removed from the dish and 100 μL of the LEX working solution containing selected Lipidex was added on the glass surface of the dish. In this step for the 96-well plate, BSS was removed and 100 μL of the LEX solution was added to each well. The dish or the 96-well plate were then incubated at room temperature for 1 h while being gently shaken. After this, the LEX solution was discarded, and the cells were washed twice with BSS buffer. The cells in the dish were then imaged in fresh BSS buffer. For the control (unexchanged) sample, the cells were subject to the same preparation steps as above except that 100 μL of serum-free DMEM was added instead of LEX working solution. All imaging experiments, unless otherwise indicated, were performed within 45 min after the LEX incubation. The degree of lipid exchange for various Lipidex was monitored by measuring relative reduction of sphingomyelin (SM) in whole-cell lysates by high-performance thin-layer chromatography (TLC) following the protocol described elsewhere (24,25).

TIRFM imaging and ImFCS measurements

The instrumental set up for time-lapse TIRFM imaging was described elsewhere (6,8,25). TIRFM images of IgE-sensitized, YFP-Syk-expressing cells were taken every 1 min after addition of DNP-BSA. The YFP-Syk puncta analysis (number of puncta per unit area of background-corrected cell images) was done using built-in functions in FIJI/ImageJ (38).

The details of ImFCS data acquisition, analysis, and synthesis of bootstrapped cumulative distribution functions (CDFs) of diffusion coefficients were described previously (6). The ImFCS data acquisition protocol was carried out based on the criteria described elsewhere (39,40). ImFCS analysis (41) to determine pixel-by-pixel D values was done using as FIJI/ImageJ plug-in (Imaging_FCS 1.491; available at http://www.dbs.nus.edu.sg/lab/BFL/imfcs_image_j_plugin.html). All imaging measurements were done at room temperature.

Generation of bootstrapped CDF of D values

ImFCS measurements were performed on 10 or more cells from independent sample preparations (at least three separate experiments with at least three cells each) for a given condition. In a typical ImFCS measurement on a given cell, a region of interest on the sample consisting of 625 square pixel units (length = 320 nm) is chosen and correspondingly 625 D values are obtained. After analyzing data from all cells, we pooled the D values (for example, a total of 6250 D values can be obtained from 10 cells with 625 values from each cell). We then performed bootstrapping of the pooled D values. In this process, 50% of the pooled D values (for example, 3125 values are chosen from a total of 6250 D values) were chosen without bias and a CDF of these subset of D values is generated. This process of bootstrapping and the synthesis of corresponding CDF are then repeated 30 times. The CDFs are then overlaid as presented in Figs. 2, A, C, and 3, A, C. This analysis is performed using Igor Pro 8 (WaveMetrics, Lake Oswego, OR). This process was described in great detail previously (6,28).

Figure 2.

Interleaflet coupling of LEX in outer leaflet are sensed by inner leaflet lipid probes. (A and B) Liquid ordered-preferring PM-EGFP and (C and D) liquid disordered-preferring EGFP-GG. (A and C) The modulation of probes’ diffusion due to LEX for the indicated types of exogeneous lipids is shown as bootstrapped CDFs of D at different control and LEX conditions. (B and D) The relative change of D is shown as the DLex/DCtrl ratio. The error bars in these plots depict the entire range of values of this parameter. To see this figure in color, go online.

Figure 3.

LEX-induced changes of outer leaflet order changes the diffusion coefficient correspondingly in this leaflet. (A) Bootstrapped cumulative distribution function (CDF) of diffusion coefficients (D) of FAST-DiO in control and LEX cells. (B) The ratio of average D in LEX cells to that in control cells (DLex/DCtrl) for FAST-DiO for the indicated LEX. (C and D) Bootstrapped CDFs of D and DLex/DCtrl of YFP-GL-GPI on LEX and control cells. The error bars in the DLex/DCtrl plots show the entire range of values of this parameter. To see this figure in color, go online.

Quasi-TIRFM imaging

The same TIRFM setup described above was used to do the quasi-TIRFM imaging (42,43,44). The incident angle was manually set at less than critical angle such that the excitation beam was not internally reflected but rather passed through a cross section of the sample. In this manner, a slice of the sample away from the surface is illuminated, which allows for imaging of intracellular components located away from the plasma membrane.

FRAP measurements

The instrumental setup as well as fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) data acquisition and fitting criteria were described elsewhere (6).

Results

The substitution of outer leaflet lipids by selected exogenous lipids (Lipidex) in complexes with mαCD (mαCD-Lipidex), dubbed LEX, is an efficient method to modify outer leaflet composition in a highly controlled manner (24). In this study we extend LEX, which has been primarily used to explore interleaflet coupling in model systems, to investigate the same coupling process in live cells and the accompanying effects on cellular signaling. We use RBL mast cells as a representative mammalian cell line for which a large body of biophysical, biochemical, and cell biological information is available. For example, phospholipid composition of RBL plasma membrane (45,46) and biophysical properties of live cell membranes (47,48), as well as RBL-derived GPMVs (11,49,50), have been reported. Likewise, the mast cell signaling cascade mediated by IgE-FcεRI and the importance of membrane biophysical properties in the earliest stage of this process are well established (6,7,51,52).

LEX efficiently replaces outer leaflet lipids of RBL plasma membrane

We first characterized the compatibility of LEX for RBL cells. For this, Lipidex (POPC [3 mM] or DPPC [1.5 mM] or DSPC [1.5 mM]) is complexed with an excess of mαCD (40 mM) such that free mαCD may extract lipids from the plasma membrane while the mαCD-Lipidex complex delivers the Lipidex to the plasma membrane (26). The choice of Lipidex content can be guided by previous reports (25).

The plasma membrane pool of SM, which is about 70% of whole cell SM content, is almost exclusively present in the outer leaflet (2). As shown previously for other cell types (25,26,37), the amount of SM remaining with the cells after LEX is a good indicator of the lipid exchange efficiency. We used high-performance TLC to determine the level of SM (normalized against total protein concentration) in whole cell lysates in unexchanged (control) and various LEX conditions on RBL cells. Results are shown in Fig. S1. We found that the SM content is reduced significantly under LEX conditions. Specifically, the amounts of residual SM are 23, 39, and 48% compared with control cells after exchange of POPC, DPPC, and DSPC, respectively, under our conditions. Correspondingly, the trend of LEX efficiency under our conditions is: POPC > DPPC > DSPC. The observed amounts of residual SM in RBL cells are comparable with those of Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells (37) for these Lipidex species. As a positive control, we used brain SM (1.5 mM) as Lipidex and observed a marked increase of total SM as expected (Fig. S1). Overall, LEX in RBL cells appears to be as efficient as for other cell types tested previously.

Diffusion in plasma membrane is perturbed by LEX and recovers over prolonged incubation

We started our investigations with ImFCS measurements on Alexa Fluor 488-labeled IgE-FcεRI complex (AF488-IgE-FcεRI) before (control) and after POPC-LEX (Fig. S2). RBL cells were labeled with AF488-IgE before LEX. The cells were washed after LEX with BSS, and diffusion of AF488-IgE-FcεRI was measured as a function of time. The Dav of this TM probe increases twofold after POPC-LEX (Dav = 0.30 ± 0.002 μm2/s; mean ± SE) cells compared with control unexchanged cells (Dav = 0.15 ± 0.001 μm2/s), and it remains steady until ∼45 min post LEX. Then, the Dav of this probe decreases monotonically over time suggesting recovery of original membrane viscosity. The Dav value is close to that of control cells after a recovery period of ∼2 h (Dav = 0.19 ± 0.001 μm2/s). Based on these observations, we decided to conduct all ImFCS experiments within 45 min after LEX to measure the effects of the perturbation of lipid composition before spontaneous recovery and restoration of normal membrane diffusion occur.

Changes in the inner leaflet diffusion correlate with ordering and disordering of the outer leaflet

After establishing the measurement criteria, we tested the effects of LEX on the diffusion properties of inner leaflet probes to quantitatively evaluate the degree of inner-leaflet coupling. We used Lipidex species that are either order promoting (DPPC and DSPC) or disorder promoting (POPC). To evaluate the interleaflet impact of these substantial outer leaflet changes (Fig. S1), we measure the diffusion of inner leaflet lipid probes PM-EGFP (order preferring) and EGFP-GG (disorder preferring) (34) by ImFCS. We used these probes previously to demonstrate local stabilization of ordering around Ag-clustered IgE-FcεRI (6,7,34).

Fig. 2A shows bootstrapped CDFs of D values for PM-EGFP under various conditions, and extracted Dav values are listed in Table 1. The shifts in the CDFs provide easy visual distinction of diffusion changes between two conditions (6): a left shift means slower diffusion and vice versa. The diffusion of PM-EGFP in POPC-LEX cells is markedly faster than for control cells indicating strong interleaflet interaction (Fig. 2 A). The Dav values for PM-EGFP in control and POPC-LEX cells are 0.63 ± 0.004 and 0.90 ± 0.005 μm2/s, respectively (Fig. 2 A, top; Table 1). In contrast, the Dav of PM-EGFP is considerably slower in DPPC-LEX (Fig. 2 A, middle) and DSPC-LEX (Fig. 2 A, bottom) cells than in the control cells measured in the same experiment. The Dav values are 0.62 ± 0.002 and 0.39 ± 0.001 μm2/s, respectively, for corresponding control and DPPC-LEX cells. Likewise, the Dav values were 0.67 ± 0.003 and 0.29 ± 0.002 μm2/s, respectively, for corresponding control and DSPC-LEX cells. As seen in Table 1, measurements on the same control cells may vary a bit on different days. Therefore, we determined the ratio of Dav of LEX to control cells as the DLex/DCtrl parameter to make a more direct and objective comparison across different Lipidex (Fig. 2 B). This parameter is equal to, greater, or lesser than 1 for no change, increase, or decrease, respectively, in Dav due to LEX. The DLex/DCtrl values of PM-EGFP for POPC-, DPPC-, and DSPC-LEX are 1.43, 0.63, and 0.44, respectively (Fig. 2 B; Table 1).

Table 1.

Dav and DLex/DCtrl values for all probes in control and Lipidex-LEX-treated cells

| Probe | Condition | Dav (μm2/s)a | DLex/DCtrlb |

|---|---|---|---|

| PM-EGFP | control | 0.63 ± 0.004 | 1 |

| POPC-LEX | 0.90 ± 0.005 | 1.43 (1.36–1.50) | |

| control | 0.62 ± 0.002 | 1 | |

| DPPC-LEX | 0.39 ± 0.001 | 0.63 (0.61–0.65) | |

| control | 0.67 ± 0.003 | 1 | |

| DSPC-LEX | 0.29 ± 0.002 | 0.44 (0.42–0.46) | |

| EGFP-GG | control | 0.66 ± 0.005 | 1 |

| POPC-LEX | 0.88 ± 0.006 | 1.35 (1.27–1.42) | |

| control | 0.66 ± 0.003 | 1 | |

| DPPC-LEX | 0.45 ± 0.002 | 0.68 (0.66–0.71) | |

| control | 0.69 ± 0.003 | 1 | |

| DSPC-LEX | 0.31 ± 0.001 | 0.45 (0.43–0.47) | |

| FAST-DiO | control | 0.79 ± 0.006 | 1 |

| POPC-LEX | 0.78 ± 0.003 | 0.99 (0.94–1.03) | |

| DPPC-LEX | 0.33 ± 0.002 | 0.42 (0.40–0.45) | |

| DSPC-LEX | 0.22 ± 0.002 | 0.28 (0.26–0.30) | |

| YFP-GL-GPI | control | 0.38 ± 0.002 | 1 |

| POPC-LEX | N.D. | N.D. | |

| DPPC-LEX | 0.29 ± 0.002 | 0.77 (0.74–0.81) | |

| DSPC-LEX | 0.19 ± 0.001 | 0.49 (0.47–0.51) | |

| AF488-CTxB-GM1 | control | 0.15 ± 0.001 | 1 |

| POPC-LEX | 0.24 ± 0.001 | 1.60 (1.51–1.71) |

Dav values are given as mean ± SE.

Mean values of DLex/DCtrl are provided. The range of values of this parameter is given in the parentheses.

We conducted the same set of experiments for the disorder-preferring probe EGFP-GG. The CDFs of D values for this probe at various LEX conditions are shown in Fig. 2 C, with extracted values in Table 1. The trends of LEX-induced diffusion change of EGFP-GG are the same as those of PM-EGFP (Fig. 2 A): POPC-LEX increases diffusion of both probes while DPPC- and DSPC-LEX decrease their respective diffusion. This similarity in the trends of these two inner leaflet probes may be quantified and compared by their respective DLex/DCtrl values for each Lipidex (Fig. 2, B and D; Table 1). The DLex/DCtrl values of EGFP-GG are 1.35, 0.68, and 0.45 for POPC-, DPPC-, and DSPC-LEX, respectively, which are comparable with those of PM-EGFP. These results on the behavior of two probes having orthogonal phase preference are thus consistent with the view that exchange of outer leaflet lipids has interleaflet impact in which more disordered outer leaflet globally causes the inner leaflet to be more disordered and vice versa (see Discussion).

Diffusion of outer leaflet lipid probes is modulated by LEX

Fig. 2 and Table 1 show that LEX-mediated interleaflet coupling leads to global changes in the inner leaflet diffusion. This is an interesting difference from the effects of nanoscale clustering of IgE-FcεRI after Ag cross-linking where ordered regions are locally stabilized around the receptors making the distal regions more disordered. Such stabilization leads to an increase and decrease of the diffusion coefficients of EGFP-GG, and PM-EGFP, respectively (6). These contrasting effects of LEX and FcεRI nanoclustering led us to hypothesize that the order in the outer leaflet changes globally (i.e., on the entire leaflet as opposed to local nanoscopic regions) due to LEX.

To test this hypothesis, we first monitored the diffusion of FAST-DiO, a disorder-preferring lipid probe (53), in the outer leaflet under various Lipidex-LEX conditions. In control cells, the Dav of FAST-DiO is 0.79 ± 0.006 μm2/s (Table 1), close to the literature report of similar probes (53). We monitored the changes of the outer leaflet diffusion after DPPC- and DSPC-LEX. The Dav of FAST-DiO, similar to the inner leaflet probes, drops significantly under these conditions (Table 1), which is also reflected in the left-shift of the D CDFs (Fig. 3 A). The DLex/DCtrl values of FAST-DiO for DPPC- and DSPC-LEX are 0.42 and 0.28, respectively (Fig. 3 B; Table 1). It appears that incorporation of order-promoting lipids (DPPC or DSPC) makes the outer leaflet significantly more ordered.

This is further supported from the modulation of diffusion behavior of yellow fluorescent protein (YFP)-tagged glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) lipid anchor (YFP-GL-GPI (54)), an order-preferring outer leaflet lipid probe, in response to various LEX. The Dav of YFP-GL-GPI in control cells is 0.38 ± 0.002 μm2/s (Table 1), which is similar to the previously reported values in RBL and other cell lines (6,8,53,55). D values for YFP-GL-GPI are slower in both DPPC- and DSPC-LEX cells (Fig. 3 C). The Dav values for DPPC- and DSPC-LEX cells are 0.29 ± 0.001 and 0.19 ± 0.001 μm2/s, respectively, yielding corresponding DLex/DCtrl values of 0.77 and 0.49 (Fig. 3 D; Table 1). Interestingly, when we compare the DLex/DCtrl values from the same Lipidex, the effects of order-promoting lipids are more pronounced on the diffusion of FAST-DiO (disorder-preferring probe) than YFP-GL-GPI (order-preferring probe) (Table 1).

We confirmed that high concentrations of saturated lipids do not induce large gel-like domains in the outer leaflet, which, if formed, would be expected to result in large immobile fractions of order-preferring probes. We conducted FRAP on DSPC-LEX cells expressing YFP-GL-GPI (Fig. S4). While we observed slower florescence recovery (slower diffusion) than the control cells, we did not see any change in the immobile fraction. These results are consistent with the absence of large gel-like domains in DSPC-LEX cells. Together, our results on the diffusion behavior of selective outer leaflet probes show that LEX-induced changes of order in this leaflet correspond to whether Lipidex promotes membrane order or disorder.

It was more difficult to define the effects of POPC-LEX on the outer leaflet, and we could not use YFP-GL-GPI as a probe under these conditions. TIRFM imaging showed nonuniform fluorescence distribution of YFP-GL-GPI in POPC-LEX cells (Fig. S5, left panel). Quasi-TIRFM images further revealed that POPC-LEX depletes YFP-GL-GPI from the plasma membrane, redistributing to internal membranes. By contrast, no obvious depletion of plasma membrane expression or internal membrane expression of YFP-GL-GPI was observed after LEX with order-promoting lipids (DPPC or DSPC). Both quasi-TIRFM and TIRFM images of the inner leaflet probe, PM-EGFP, in POPC-LEX conditions does not show any obvious internalization of this probe (Fig. S5, right panel). This implies that POPC-LEX-induced internalization is likely to be restricted to only some outer leaflet components (see Discussion).

Measurements on outer leaflet diffusion after POPC-LEX could be made using FAST-DiO. As shown in Fig. 3 A, the Dav of this probe remains unchanged after POPC-LEX, resulting in a DLex/DCtrl value of 0.99 (Fig. 3 B; Table 1). This suggests that the physical properties of outer leaflet regions explored by FAST-DiO change little after POPC-LEX. However, when we measured the diffusion of Alexa Fluor 488-labeled cholera toxin B (AF488-CTxB) bound to GM1, another well-established outer leaflet marker that is order preferring (49), we found the Dav of AF488-CTxB-GM1 (0.15 ± 0.001 μm2/s in control cells) increases to 0.24 ± 0.001 μm2/s after POPC-LEX (DLex/DCtrl = 1.60, Fig. S3; Table 1). The origin of these behaviors is considered in the Discussion.

Stimulated Syk recruitment is enhanced when more ordered plasma membrane is created in the resting state

Recruitment of Syk kinase to the plasma membrane is the next step after FcεRI phosphorylation by Lyn kinase in mast cell signaling. We evaluated this process by measuring recruitment kinetics and density distribution of YFP-Syk using quantitative TIRFM imaging. We sensitized the cells with unlabeled IgE and carried out LEX, for which diffusion measurements show modifies inner leaflet order. Cells were stimulated by Ag clustering of IgE-FcεRI.

We first imaged IgE-sensitized RBL cells transiently expressing YFP-Syk using TIRFM, which has an evanescent excitation wave that illuminates the surface-attached plasma membrane and a shallow membrane-proximal cytoplasmic plane. In this resting condition, we observed a featureless diffuse distribution of YFP-Syk in the cytoplasm (56,57) (Fig. 4 A, left panel). We then directly added Ag to the cells and imaged a representative cell in an imaging dish for each Lipidex-LEX sample tested at 1 image/min speed over 15 min after stimulation. The recruitment of YFP-Syk is clearly observed after 4–5 min as distinct punctate features against the cytoplasmic background (Video S1; Fig. 4 A). These membrane-localized features appearing after stimulation are similar to those reported previously (57). We also determined the density of YFP-Syk puncta (i.e., number of puncta/cell area) as a function of time. We found that the puncta density reaches a steady state by 15 min after stimulation (Fig. 4 B), and we proceeded to image many cells at this stimulated steady state to obtain a distribution of the density of plasma membrane-localized YFP-Syk puncta for each Lipidex-LEX (Fig. 4 C).

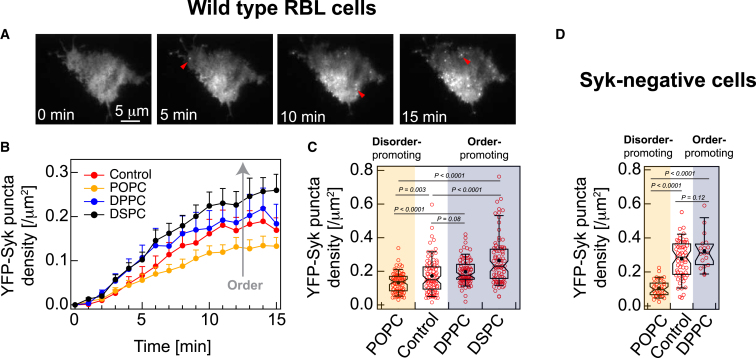

Figure 4.

Stimulated recruitment of YFP-Syk to the inner leaflet of the plasma membrane correlates with the resting-state order of this leaflet modulated by outer leaflet LEX. (A and B) Kinetics of YFP-Syk recruitment with different exchanged lipids and control conditions in wild-type RBL cells. (A) TIRFM snapshots of a representative control cell expressing YFP-Syk at various time points after the addition of antigen (Ag), DNP-BSA (see Video S1). (B) Compiled data from 12 to 18 cells for each data point. The error bars represent standard error of the mean (mean ± SE). (C) Boxplots of density of the recruited YFP-Syk punctas in stimulated steady state (15–30 min after stimulation). Number of cells >80 for each condition. (D) Boxplots of density of YFP-Syk punctas in Syk-negative cells (transiently expressing YFP-Syk) after 15 min stimulation. Number of cells >15 at each condition. Box height corresponds to the 25th to 75th percentile; error bars represent the 9th to 91st percentile of the entire data set; mean and median values are represented as solid circles and bars, respectively; notches signify 95% CI of the median. To see this figure in color, go online.

The movie is recorded at 1 min time resolution.

Fig. 4B shows the time course of stimulated YFP-Syk recruitment for control cells compared with those with more ordered (DPPC-LEX or DSPC-LEX) or disordered (POPC-LEX) outer leaflet compositions (and correspondingly more ordered or disordered inner leaflet due to interleaflet coupling) as established under resting conditions (Figs. 2 and 3). In the absence of Ag stimulation, we observed negligible YFP-Syk recruitment in control cells and with each Lipidex tested (Fig. 4 B, 0 time point). For stimulated cells, the rate of increase of YFP-Syk puncta density is similar for control and POPC-LEX cells and somewhat higher for DPPC- and DSPC-LEX cells (Fig. 4 B). The YFP-Syk puncta density at the stimulated steady state (15 min poststimulation) as measured in the time course is remarkably different across the Lipidex tested. YFP-Syk puncta density is significantly lower for POPC-LEX cells compared with control cells. We observed the reverse for cells exchanged with order-promoting lipids (DPPC-LEX and DSPC-LEX). Following the same trend as the interleaflet effects on diffusion (Fig. 2, B and D), we further observed that DSPC-LEX has greater impact than DPPC-LEX on stimulated YFP-Syk recruitment.

To gain more quantitative and statistically robust information, we imaged ∼100 cells expressing YFP-Syk in stimulated steady state for control cell and each Lipidex tested (Fig. 4 C). We found that ∼80% of cells show stimulated YFP-Syk puncta in all cases. However, the puncta density of LEX cells is statistically different from the control cells. Compared with control cells (median YFP-Syk density = 0.15/μm2), cells exchanged with order-promoting lipids, DPPC-LEX and DSPC-LEX show 18 and 54% higher median YFP-Syk density, respectively, at stimulated steady state, whereas cells exchanged with disorder-promoting lipid, POPC-LEX, show 8% lower median YFP-Syk density. Overall, the degree of stimulated Syk recruitment, a plasma membrane proximal signaling event, appears to correlate with the inner leaflet membrane order created in resting cells.

To consider the possibility that Syk endogenously expressed in RBL cells affects stimulated recruitment of transiently expressed YFP-Syk, we employed Syk-negative cells (33). This RBL variant cell line expresses no detectable Syk and correspondingly has an abrogated signaling cascade when stimulated by Ag. We transiently transfected YFP-Syk into Syk-negative cells and tested effects of POPC-LEX (disorder promoting) and DPPC-LEX (order promoting) compared with control cells. We found for control cells that the stimulated steady-state density of plasma membrane localized YFP-Syk puncta is generally higher in the Syk-negative cells compared with the wild-type RBL cells (median values are 0.29 and 0.15/μm2, respectively), as might be expected from eliminated competition with endogenous Syk. In Syk-negative cells, the steady-state levels of recruited YFP-Syk puncta are significantly lower for POPC-LEX compared with control cells, and DPPC-LEX are significantly higher than POPC-LEX (Fig. 4 D). We were unable to evaluate DSPC-LEX because the Syk-negative cells did not sufficiently survive this treatment. Overall, the trends of stimulated YFP-Syk recruitment are qualitatively similar for wild-type and Syk-negative RBL cells (Fig. 4, C and D): LEX to increase disorder-promoting lipids in the outer leaflet decreases stimulated Syk recruitment, while this signaling activity is enhanced by LEX to increase order-promoting lipids in the outer leaflet. These results are consistent with interleaflet coupling and participation of inner leaflet order in the process leading to Syk recruitment.

More ordered resting plasma membrane correlates with stronger stimulated degranulation

Stimulated Syk recruitment is a signaling event proximal to Ag clustering of IgE-FcεRI in the membrane. We also tested whether modulation of outer leaflet order correlates with the culminating step of the signaling cascade, which is exocytosis of secretory granules containing β-hexosaminidase and other chemical mediators. As shown in Fig. 5, we observed a similar trend for Ag-stimulated degranulation: POPC-LEX to increase disorder-promoting lipids in the outer leaflet decreases stimulated degranulation by almost 80% compared with control cells, whereas DPPC-LEX and DSPC-LEX to increase order-promoting lipids in the outer leaflet increase this response by 30 and 50%, respectively. Therefore, stimulated degranulation correlates with LEX-altered resting-state membrane order in a fashion analogous to stimulated Syk recruitment.

Figure 5.

Degree of stimulated degranulation correlates with resting-state plasma membrane order modulated by outer leaflet LEX. Relative degranulation for specified Lipidex-LEX conditions are shown. The error bars are standard error of mean (mean ± SE). To see this figure in color, go online.

Discussion

LEX is a useful approach for studying interleaflet coupling in live cells

Interleaflet coupling between compositionally distinct inner and outer leaflets is a key biophysical determinant of plasma membrane heterogeneity in each leaflet (21,58,59). Longitudinal coupling based on TM proteins may occur if the local membrane environment is influenced by protein components in one or the other (or both) leaflets. For example, some TM proteins that are palmitoylated in cytoplasmic segments tend to associate with ordered domains in the inner leaflet (60). Interleaflet coupling mediated by lipids is more challenging to explain without invoking associations with TM proteins or lipid interdigitation. Such coupling has been demonstrated, and reported to be governed by (transient) immobilization of long-chain lipids either by extracellular cross-linking (for example, gangliosides by multivalent toxins (14)) or by intracellular coupling with cortical actin machinery (13). These experimental strategies to demonstrate lipid-based interleaflet coupling chiefly depend on cross-linking or immobilizing a component in one leaflet and monitoring the effect on the opposing leaflet.

Taking a different strategy, we employed LEX, which manipulates the lipid composition of the membrane outer leaflet. For robust examination of inner leaflet effects, we measured diffusion of inner leaflet lipid probes with highly sensitive ImFCS. By performing LEX experiments on RBL mast cells we could also evaluate functional consequences by measuring early and late steps of mast cell signaling initiated by IgE-FcεRI. The exchange of outer leaflet lipids with exogenous lipid (Lipidex) by LEX offers a straightforward method to incorporate selected lipids. The mαCD-Lipidex complex acts as a lipid donor in concert with uncomplexed mαCD, which acts as a lipid acceptor that simultaneously removes endogenous outer leaflet lipids. Such donor-acceptor lipid exchange systems using various types of cyclodextrin have been widely used to create asymmetric artificial lipid membranes (58). This provides an excellent experimental platform to study interleaflet coupling in these model systems. Applications of mαCD has some advantages over other cyclodextrin species for experiments using living cells, including its incapacity to complex with cholesterol because of cavity size. Correspondingly, mαCD-catalyzed lipid exchange does not significantly change cellular cholesterol content, unlike methyl-β-cyclodextrin (61). Another favorable property of mαCD is its low specificity for the lipid structures allowing efficient extraction of various nonsterol lipids (e.g., PC and SM) from the outer leaflet (25).

Changes in diffusion properties of outer leaflet lipid probes after LEX show interesting trends. In the absence of LEX, slower diffusion of CTxB relative to FAST-DiO may reflect the complexation of CTxB with up to five copies of GM1 as well as localization of GM1 in domains of higher membrane order. If the outer leaflet has preexisting heterogeneity with both more ordered and more disordered domains, then addition of either an order- or disorder-promoting lipid, would likely cause the distribution to shift. We can reason simplistically in terms of ternary phase diagrams based on model membranes approximating outer leaflet lipids (62,63). Addition of disorder-promoting POPCex would be expected to cause a relative increase in the amount of disordered domains. We find little impact on Dav of disorder-preferring FAST-DiO after POPC-LEX (Fig. 3 A; Table 1), whereas Dav of order-preferring AF488-CTxB-GM1 increases (Fig. S3; Table 1). This is consistent with the view that FAST-DiO diffusion is not sensitive to these changes in disorder while AF488-CTxB-GM1 partitions with less preference into the looser ordered domains. On the other hand, because CTxB can induce ordered domain formation (16,64), another interpretation is that replacement of sphingolipids and other order-promoting lipids with POPC prevents formation of such domains. LEX with order-promoting DPPC and DSPC would be expected to cause a relative increase in the amount of ordered domains. The observed decrease of Dav for both disorder- and order-preferring probes (FAST-DiO and YFP-Gl-GPI) after DPPC- and DSPC-LEX (Fig. 3, A and C; Table 1) indicates that both probes have some sensitivity to this modulation in lipid distribution. The larger change for FAST-DiO (DLex/DCtrl > 0.3) compared with YFP-GL-GPI (DLex/DCtrl < 0.3) suggests that disordered regions of the plasma membrane may be substantially reduced under these conditions. Although a ternary phase diagram (62,63) may provide some useful insight, it is still far from describing the phase behavior of a living cell membrane, and initial positioning of our system on any phase diagram is unknown.

Previous studies established the robustness of LEX, which has been successfully applied to multiple cell types including RBC, CHO, HeLa, RBL, macrophages, and A549 (24,25,37,65). In addition to the phospholipids used as Lipidex in this study, sphingolipids can similarly be incorporated (25) (Fig. S1 A). The effect of LEX on plasma membrane-localized processes also can be tested. Examples include stimulated phosphorylation of insulin receptor in CHO cells (37), endocytosis of model nanoparticles in A549 cells (66), and stimulated Syk recruitment during mast cell signaling (Fig. 4). The approach has been proven to be versatile, but it should be noted that degree of Lipidex incorporation can depend on both the types of cells and on the particular Lipidex (26). Correspondingly, the degree of lipid exchange must be quantified, for example, by TLC (Fig. S1) or mass spectrometry (66), as part of interpreting the biophysical and functional consequences.

Another important factor that should be considered is whether LEX alters inner leaflet lipid composition. Cyclodextrins are very hydrophilic compounds (sugars) that should not have access to the inner leaflet, and numerous studies with artificial lipid vesicles with a very wide range of lipid compositions showed that exchange involves only outer leaflet lipids (15,19,67,68,69,70,71,72). Moreover, the composition of the phospholipids removed from the plasma membrane corresponds to the lipid composition of the outer leaflet (24). We previously found that lipids introduced into the outer leaflet remain accessible to back exchange with fresh cyclodextrin for some time, indicating that they remain in the outer leaflet (24,25). Homeostatic flippases and floppases should act to preserve asymmetry and not flip the exogenous lipids into the inner leaflet. Nevertheless, we cannot rule out a small amount of lipid flip to scramble lipids after LEX in resting cells. Lipid scrambling during cell responses to stimuli can occur, as detected by reversible loss of asymmetry (21). This appears to be mediated by increases in cytosolic Ca2+ causing activation of lipid scramblase proteins, and oscillations in elevated Ca2+ during Ag-stimulated mast cell activation has been characterized (73). Delineating how LEX followed by activation affects membrane leaflet composition and interleaflet coupling as related to functional outcomes is a goal of future studies.

Live cells, not surprisingly, respond to compensate for changes accompanying exchange with a substantial amount (>50%) of exogenous lipid. For example, the diffusion of AF488-IgE-FcεRI is restored over 2 h after POPC-LEX (Fig. S2). Cells may degrade or modify the introduced exogenous lipids (24,25,74), and replenish exchanged lipids by synthesizing new lipids or delivering preexisting lipids to the plasma membrane from internal sources. Therefore, experiments must be restricted to times in which LEX-induced composition is stable, which can depend on the choice of Lipidex (25). Some unintended indirect effects of LEX should be considered. For example, YFP-GL-GPI is depleted from the plasma membrane in POPC-LEX cells (Fig. S5), although this was not observed for DPPC- or DSPC-LEX cells. Investigation of the mechanisms underlying YFP-GL-GPI depletion is beyond the scope of this work, but one possibility is that POPC-LEX might trigger internalization of the outer leaflet components of ordered regions such as YFP-GL-GPI. For example, a high fraction of saturated lipids, a key component of ordered regions, exchanged with POPC may render relevant ordered regions in the outer leaflet sparse, less stable or both. This might affect constitutive endocytosis and recycling, both of which would halt when a step of membrane trafficking is blocked. Refaei et al. showed that the ordered regions of the plasma membrane strongly affect the recycling process in resting CHO cells (75). Another study showed that replacing order-stabilizing sterols with sterols that do not support ordered nanodomains slows membrane trafficking as judged by inhibition of endocytosis (27). In the current context, the loss of ordered regions in the POPC-exchanged plasma membrane may disrupt YFP-GL-GPI recycling, causing concentration in internal membranes or degrading lysosomes. We cannot rule out other indirect effects of LEX, including changes in cholesterol distribution within the plasma membrane or interactions with the actin cytoskeleton.

LEX induces global changes in the inner leaflet diffusion properties

Our recent high-resolution studies (6,7) showed that cross-linking of IgE-FcεRI by multivalent Ag stabilizes phase-like separation in the inner leaflet. Proximal to the clustered receptors is an ordered environment that is surrounded by a disordered region. In other words, the ordered and disordered regions become more distinctive in the stimulated steady state, as reflected in the diffusion behavior of order- and disorder-preferring lipid probes in the inner leaflet, PM-EGFP and EGFP-GG, respectively. Consistent with the probes spending more time in their preferred membrane regions, the D value of PM-EGFP decreases while that of EGFP-GG increases in Ag-stimulated relative to resting cells (6). We observed the same trend in the diffusion behavior of these two probes in resting cells after inhibition of actin polymerization by cytochalasin D (8), which is consistent with cytoskeletal regulation of phase-like properties (76).

In contrast, D values for both PM-EGFP and EGFP-GG in the inner leaflet of resting cells increase when the outer leaflet is exchanged with disorder-promoting POPC, and their D values both decrease when outer leaflet lipids are exchanged with order-promoting DPPC or DSPC (Fig. 2, A and C). Interestingly, the DLex/DCtrl values of both PM-EGFP and EGFP-GG are similar for each of these LEX conditions (Fig. 2, B and D; Table 1). This suggests that any preexisting ordered and disordered regions in the inner leaflet do not become more distinctive due to LEX-driven interleaflet interactions. Although we cannot call on a simple phase diagram to help interpret these observed changes, it appears that the inner leaflet becomes more disordered globally when a disorder-promoting lipid (POPC) is introduced in the outer leaflet. Conversely, when order-promoting lipids (DPPC or DSPC) are introduced in the outer leaflet, the inner leaflet appears to become globally more ordered. Notably, DSPC lipid vesicles having higher transition temperature than DPPC lipid vesicles (54 and 41°C, respectively) is likely to induce a stronger ordering effect than DPPC and, correspondingly, DLex/DCtrl of all probes tested here is smaller in DSPC-LEX cells than in DPPC-LEX cells (Table 1).

Although we did not measure an order parameter of the inner leaflet directly, the D values of these lipid probes are likely to be inversely related to membrane order (56,57). Both PM-EGFP and EGFP-GG showed fastest diffusion in POPC-LEX cells and slowest diffusion in DSPC-LEX cells among the conditions tested here (Fig. 2; Table 1). This implies that the inner leaflet is most disordered in POPC-LEX cells and most ordered in DSPC-LEX cells. For the Lipidex we tested, the apparent inner leaflet order correlates with order preference: POPC < control < DPPC < DSPC.

Our observation of global changes in diffusion of both order- and disorder-preferring lipid probes after LEX resembles those we observed previously after antibody cross-linking and immobilization of CTxB-GM1 complexes (28). However, the degree of probe diffusion changes in these two treatments (LEX and GM1 cross-linking) are different. The Dav changes from PM-EGFP and EGFP-GG were ∼32 and 55% after DPPC- and DSPC-LEX (Fig. 3, D and H). In contrast, antibody cross-linking of GM1 with anti-CTxB antibody results in only ∼16% reduction of Dav of these probes (28). LEX appears to cause changes in the order of the entire outer leaflet. In contrast, cross-linking GM1 directly affects a single membrane component. Thus, this difference is likely due to relatively larger interleaflet coupling effects (as monitored by inner leaflet probe diffusion) by LEX than antibody cross-linking of GM1.

Overall, we have experimentally evaluated various modes of “outside-in” interleaflet interactions (this study and (6,28)) and found primarily two different outcomes as measured from precise diffusion measurements of these inner leaflet probes: either stabilization of phase-like separation (e.g., Ag clustering of IgE-FcεRI receptors (6) or global change of membrane order, LEX [this study] and antibody cross-linking of CTxB-GM1 (28)). This body of work establishes the power of our bootstrapping-based analysis of diffusion coefficients of lipid probes measured by ImFCS (6) to delineate subtle changes of membrane organization in live cells and thereby illuminate underlying biophysical principles.

LEX-mediated interleaflet coupling demonstrated here is fundamentally distinctive from other proposed “outside-in” mechanisms, which generally involve immobilization of membrane components. Two other groups reported that immobilization of outer leaflet GM1 or GPI-anchored protein by antibody cross-linking leads to the changes in the diffusion properties of inner leaflet probes (14,77). Likewise, the Mayor group has shown that cross-linking and immobilization of saturated, long-chain ceramides, but not their unsaturated counterpart, induces ordered regions in the inner leaflet (16). In contrast, LEX does not directly immobilize any membrane component. We therefore infer that lipid-mediated interleaflet interactions do not strictly require immobilization of a membrane component. Thus, the key effect of cross-linking may be local formation of a more ordered state rather than the immobilization that also accompanies cross-linking.

More ordered membrane in the poised resting state leads to stronger functional response

Ag-stimulated stabilization of ordered regions has been demonstrated to play a key role in facilitating receptor phosphorylation above a nonfunctional threshold in IgE-FcεRI-mediated cell signaling (78). Preferential partitioning of Lyn kinase with Ag-clustered FcεRI in the ordered regions facilitates net receptor phosphorylation, while dephosphorylation by TM phosphatases preferring the disordered regions is suppressed. Phosphorylated FcεRI then recruit Syk kinase to propagate intracellular signaling cascade leading to cellular degranulation. We monitored, for different Lipidex-LEX, Ag-stimulated recruitment of YFP-Syk kinase to the inner leaflet of the plasma membranes. Our time-lapse TIRFM imaging after LEX clearly demonstrates that the density of plasma membrane localized YFP-Syk in Ag-stimulated steady state correlates positively with the order preference of Lipidex and membrane order detected by inner leaflet diffusion probes (Fig. 4). We observed the same trend for Ag-stimulated degranulation (Fig. 5). The impact of altered Syk recruitment (an early signaling event) driven by changes in membrane order may simply propagate to the degree of degranulation (ultimate cellular response), although there are many signaling steps in between, and membrane fusion involved in exocytosis may also be affected by membrane order. We cannot rule out effects on cell vitality during the longer time period required for degranulation measurements. In general, we cannot predict the influence of membrane order on intermediate signaling processes, such as stimulated calcium mobilization.

Notably, we did not detect Syk recruitment in the absence of Ag stimulation even when the inner leaflet is more ordered after LEX with order-promoting lipids (DPPC or DSPC). This means that increasing membrane order does not by itself cause sufficiently strong coupling of Lyn kinase with FcεRI to initiate signaling. Our results therefore show that a more ordered resting membrane enhances stimulation-induced phosphorylation of FcεRI by Lyn and consequent Syk recruitment. Current data allow multiple possible explanations for this outcome. We cannot rule out, for example, that the tight clustering of FcεRI by Ag dramatically increases the efficacy of FcεRI phosphorylation by Lyn in an already ordered lipid environment. It is also possible that conformation of Ag-clustered FcεRI may be altered after LEX leading to Tyr residues in cytoplasmic segments becoming more (DPPC/DSPC) or less (POPC) accessible for phosphorylation and subsequent binding to Syk kinase. Such conformational changes depending on the lipid environment was recently proposed for ligand-stimulated insulin receptors (37). However, we think it most likely that the environment surrounding the Ag-clustered FcεRI becomes even more distinctively ordered in the stimulated steady state when this leaflet is initially (in unstimulated condition) more ordered. This would further enhance co-partitioning of Lyn and exclusion of TM phosphatases by virtue of their order preferences. As shown by Young et al., the specific activity of Lyn isolated from ordered regions is about five times higher than that isolated from disordered regions (79). In contrast, incorporation of highly unsaturated ω-3 fatty acids in the plasma membrane was shown to inhibit mast cell functions in vivo (80), and the authors suggested that this is related to inhibition of Lyn kinase activity. High amounts of ω-3 fatty acid, similar to LEX-POPC, would likely make the membrane inner leaflet more disordered, which may reduce the kinase activity of Lyn.

How the global disordering (POPC) or ordering (DPPC/DSPC) we measure in resting cells is modulated by Ag clustering of FcεRI can be investigated with diffusion measurements of inner leaflet probes after LEX in stimulated cells. If essentially the same global effects are maintained as for the resting cells, then the increased ordering surrounding Lyn- and Ag-clustered FcεRI would determine the degree of receptor phosphorylation leading to Syk recruitment. In that case diffusion of inner leaflet probes would be expected to shift in the same direction as for the resting cells. However, the distinctive phase-like separation proximal to the Ag-clustered FcεRI may be necessary for facilitating Lyn access while reducing TM phosphatase access for effective phosphorylation. In that case diffusion of order-preferring PM-EGFP would be expected to decrease while that of disorder-preferring EFGP-GG would be expected to increase (6). Thus, these future measurements are expected to shed additional light on both interleaflet coupling and the importance of phase separation for FcεRI-mediating signaling.

Conclusions

This study quantitatively evaluates interleaflet coupling in live cells by measuring diffusion changes of inner leaflet lipid probes resulting from the perturbation of outer leaflet lipid composition by LEX. Our results provide compelling evidence of a novel, lipid-based interleaflet coupling mechanism that does not necessarily involve interdigitation of long-chain (>20 carbon) lipids or immobilization of a membrane component. The effect appears to be global: increasing order-promoting lipids in the outer leaflet increases the order of the inner leaflet, and increasing the content of disorder-preferring lipids in the outer leaflet decreases the order of the inner leaflet. There are clear functional consequences of interleaflet coupling induced by LEX as demonstrated with Ag-stimulated, IgE-FcεRI-mediated mast cell signaling where membrane order has been shown to regulate protein interactions associated with TM signaling events. Overall, we developed an experimental platform combining LEX, ImFCS, and quantitative fluorescence imaging to evaluate functional, lipid-based interleaflet coupling of plasma membranes in live cells.

Author contributions

B.A.B., E.L., and N.B. conceived the project. G.-S.Y., A.W.-W., B.Y., P.S., and N.B. performed the experiments. All authors analyzed the data. B.A.B., E.L., and N.B. wrote the manuscript drafts with all authors critically contributing to the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Alex Batrouni and Prof. Jeremy Baskin (Cornell University) for assisting with the FRAP measurements, and Dr. David Holowka for helpful discussion. This work is supported by National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS) grant R01GM117552 to B.A.B. and R35GM122493 to E.L. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of NIGMS or NIH.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Editor: Jeanne Stachowiak.

Footnotes

Pavana Suresh’s present address is Program in Cellular and Molecular Medicine, Boston Children’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts.

Supporting material can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpj.2023.07.027.

Supporting material

References

- 1.Sezgin E., Levental I., et al. Eggeling C. The mystery of membrane organization: composition, regulation and roles of lipid rafts. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2017;18:361–374. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2017.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lorent J.H., Levental K.R., et al. Levental I. Plasma membranes are asymmetric in lipid unsaturation, packing and protein shape. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2020;16:644–652. doi: 10.1038/s41589-020-0529-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang T.-Y., Silvius J.R. Cholesterol Does Not Induce Segregation of Liquid-Ordered Domains in Bilayers Modeling the Inner Leaflet of the Plasma Membrane. Biophys. J. 2001;81:2762–2773. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)75919-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dykstra M., Cherukuri A., et al. Pierce S.K. Location is everything: lipid rafts and immune cell signaling. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2003;21:457–481. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stone M.B., Shelby S.A., et al. Veatch S.L. Protein sorting by lipid phase-like domains supports emergent signaling function in B lymphocyte plasma membranes. Elife. 2017;6 doi: 10.7554/eLife.19891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bag N., Wagenknecht-Wiesner A., et al. Baird B.A. Lipid-based and protein-based interactions synergize transmembrane signaling stimulated by antigen clustering of IgE receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2021;118 doi: 10.1073/pnas.2026583118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shelby S.A., Veatch S.L., et al. Baird B.A. Functional nanoscale coupling of Lyn kinase with IgE-FcepsilonRI is restricted by the actin cytoskeleton in early antigen-stimulated signaling. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2016;27:3645–3658. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E16-06-0425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bag N., Holowka D.A., Baird B.A. Imaging FCS delineates subtle heterogeneity in plasma membranes of resting mast cells. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2020;31:709–723. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E19-10-0559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kannan B., Guo L., et al. Wohland T. Spatially resolved total internal reflection fluorescence correlation microscopy using an electron multiplying charge-coupled device camera. Anal. Chem. 2007;79:4463–4470. doi: 10.1021/ac0624546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krieger J.W., Singh A.P., et al. Wohland T. Imaging fluorescence (cross-) correlation spectroscopy in live cells and organisms. Nat. Protoc. 2015;10:1948–1974. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2015.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baumgart T., Hammond A.T., et al. Webb W.W. Large-scale fluid/fluid phase separation of proteins and lipids in giant plasma membrane vesicles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:3165–3170. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611357104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baumgart T., Hunt G., et al. Feigenson G.W. Fluorescence probe partitioning between Lo/Ld phases in lipid membranes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2007;1768:2182–2194. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Raghupathy R., Anilkumar A.A., et al. Mayor S. Transbilayer lipid interactions mediate nanoclustering of lipid-anchored proteins. Cell. 2015;161:581–594. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.03.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koyama-Honda I., Fujiwara T.K., et al. Kusumi A. High-speed single-molecule imaging reveals signal transduction by induced transbilayer raft phases. J. Cell Biol. 2020;219 doi: 10.1083/jcb.202006125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chiantia S., London E. Acyl chain length and saturation modulate interleaflet coupling in asymmetric bilayers: effects on dynamics and structural order. Biophys. J. 2012;103:2311–2319. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2012.10.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arumugam S., Schmieder S., et al. Johannes L. Ceramide structure dictates glycosphingolipid nanodomain assembly and function. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:3675. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-23961-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Meer G. Dynamic transbilayer lipid asymmetry. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect. Biol. 2011;3:a004671. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a004671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kobayashi T., Menon A.K. Transbilayer lipid asymmetry. Curr. Biol. 2018;28 doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2018.01.007. PR386-R391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin Q., London E. Ordered raft domains induced by outer leaflet sphingomyelin in cholesterol-rich asymmetric vesicles. Biophys. J. 2015;108:2212–2222. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2015.03.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Enoki T.A., Feigenson G.W. Improving our picture of the plasma membrane: Rafts induce ordered domains in a simplified model cytoplasmic leaflet. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 2022;1864 doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2022.183995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Doktorova M., Symons J.L., Levental I. Structural and functional consequences of reversible lipid asymmetry in living membranes. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2020;16:1321–1330. doi: 10.1038/s41589-020-00688-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.St Clair J.W., Kakuda S., London E. Induction of Ordered Lipid Raft Domain Formation by Loss of Lipid Asymmetry. Biophys. J. 2020;119:483–492. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2020.06.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kakuda S., Suresh P., et al. London E. Loss of plasma membrane lipid asymmetry can induce ordered domain (raft) formation. J. Lipid Res. 2022;63 doi: 10.1016/j.jlr.2021.100155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li G., Kim J., et al. London E. Efficient replacement of plasma membrane outer leaflet phospholipids and sphingolipids in cells with exogenous lipids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2016;113:14025–14030. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1610705113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li G., Kakuda S., et al. London E. Replacing plasma membrane outer leaflet lipids with exogenous lipid without damaging membrane integrity. PLoS One. 2019;14 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0223572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suresh P., London E. Using cyclodextrin-induced lipid substitution to study membrane lipid and ordered membrane domain (raft) function in cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 2022;1864 doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2021.183774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim J.H., Singh A., et al. London E. The effect of sterol structure upon clathrin-mediated and clathrin-independent endocytosis. J. Cell Sci. 2017;130:2682–2695. doi: 10.1242/jcs.201731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bag N., London E., et al. Baird B.A. Transbilayer Coupling of Lipids in Cells Investigated by Imaging Fluorescence Correlation Spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2022;126:2325–2336. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.2c00117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Veatch S.L., Keller S.L. A closer look at the canonical 'raft mixture' in model membrane studies. Biophys. J. 2003;84:725–726. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74891-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Felce J.H., Sezgin E., et al. Davis S.J. CD45 exclusion– and cross-linking–based receptor signaling together broaden FceRI reactivity. Sci. Signal. 2018;111 doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aat0756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rivera J., Gilfillan A. Molecular regulation of mast cell activation. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2006;117:1214–1225. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.04.015. quiz 1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hardy R.R. Blackwell Scientific; 1968. Handbook of Experimental Immunology. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang J., Berenstein E.H., et al. Siraganian R.P. Transfection of Syk protein tyrosine kinase reconstitutes high affinity IgE receptor-mediated degranulation in a Syk-negative variant of rat basophilic leukemia RBL-2H3 cells. J. Exp. Med. 1996;184:71–79. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.1.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pyenta P.S., Holowka D., Baird B. Cross-correlation analysis of inner-leaflet-anchored green fluorescent protein co-redistributed with IgE receptors and outer leaflet lipid raft components. Biophys. J. 2001;80:2120–2132. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)76185-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wakefield D.L., Holowka D., Baird B. The FcepsilonRI Signaling Cascade and Integrin Trafficking Converge at Patterned Ligand Surfaces. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2017;28:3383–3396. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E17-03-0208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Naal R.M.Z.G., Tabb J., et al. Baird B. In situ measurement of degranulation as a biosensor based on RBL-2H3 mast cells. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2004;20:791–796. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2004.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Suresh P., Miller W.T., London E. Phospholipid exchange shows insulin receptor activity is supported by both the propensity to form wide bilayers and ordered raft domains. J. Biol. Chem. 2021;297 doi: 10.1016/j.jbc.2021.101010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schindelin J., Arganda-Carreras I., et al. Cardona A. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods. 2012;9:676–682. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bag N., Sankaran J., et al. Wohland T. Calibration and limits of camera-based fluorescence correlation spectroscopy: a supported lipid bilayer study. ChemPhysChem. 2012;13:2784–2794. doi: 10.1002/cphc.201200032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sankaran J., Bag N., et al. Wohland T. Accuracy and precision in camera-based fluorescence correlation spectroscopy measurements. Anal. Chem. 2013;85:3948–3954. doi: 10.1021/ac303485t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sankaran J., Shi X., et al. Wohland T. ImFCS: a software for imaging FCS data analysis and visualization. Opt Express. 2010;18:25468–25481. doi: 10.1364/OE.18.025468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Konopka C.A., Bednarek S.Y. Variable-angle epifluorescence microscopy: a new way to look at protein dynamics in the plant cell cortex. Plant J. 2008;53:186–196. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tokunaga M., Imamoto N., Sakata-Sogawa K. Highly inclined thin illumination enables clear single-molecule imaging in cells. Nat. Methods. 2008;5:159–161. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lord S.J., Lee H.-L.D., Moerner W.E. Single molecule spectroscopy and imaging of biomoleculaes in living cells. Anal. Chem. 2010;82:2192–2203. doi: 10.1021/ac9024889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fridriksson E.K., Shipkova P.A., et al. McLafferty F.W. Quantitative analysis of phospholipids in functionally important membrane domains from RBL-2H3 mast cells using tandem high-resolution mass spectrometry. Biochemistry-Us. 1999;38:8056–8063. doi: 10.1021/bi9828324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gupta A., Muralidharan S., et al. Wohland T. Long acyl chain ceramides govern cholesterol and cytoskeleton dependence of membrane outer leaflet dynamics. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 2020;1862 doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2019.183153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]