Abstract

Background

Peroneus longus (PL) graft harvest has gained popularity in recent years for a variety of ligament surgeries. One of the common apprehensions regarding its more widespread usage has been the risk of injury to the common peroneal nerve or the sural nerve during graft harvest. The purpose of the current study is to assess the rate of injury to the peroneal and sural nerve following PL harvest using our technique in a large cohort of patients.

Materials and Methods

A prospective cohort of 600 consecutive patients undergoing PLG harvest over a period from January 2022 to December 2022 at a single tertiary referral centre were included for analysis. Patients had baseline screening of nerve function prior to surgery and were regularly followed up at 3 weeks, 6 weeks, 3 months and 6 months post-harvest. Grouped variables for the sural and peroneal nerve were completed and analysis was carried out using Cochrane’s Q test and McNemar’s test.

Results

We found that only 0.01% of patients had any nerve complications at 6 months follow-up, and three times more patients had sural nerve complaints than peroneal nerve complaints at the end of the 6 months follow-up.

Conclusion

Peroneus longus harvest is a safe and reproducible technique with low complication rate. The rate of nerve complications post-harvest is grossly overestimated in the literature secondary to low-powered and low evidence studies. We believe that using our safe surgical technique for PL harvest with respect to surface landmarks allows for PL harvest with a low nerve complication rate.

Keywords: Peroneus longus graft, Sural nerve, Peroneal nerve, Nerve injury, Ligament surgeries

Introduction

Peroneus longus (PL) graft harvest is used for a variety of surgeries including primary anterior cruciate ligament (ACL), revision ACL and multi-ligament injuries. Low donor morbidity with preservation of ankle functional scores has been proved by our recently conducted systematic review on this topic [1]. One of the common apprehensions regarding its more widespread usage has been the risk of injury to the common peroneal nerve or the sural nerve during graft harvest which ranges from 4 to 16% [2]. The majority of these studies have examined the nerve injury in a small cohort of patients or isolated case reports of iatrogenic injury. The literature regarding nerve injury complications following PL harvest remains heavily skewed towards lower evidence studies and case reports exemplifying the complication of peroneal nerve palsy after graft harvest.

Our group has published a safe surgical technique for PL harvest [3]. Surgical landmarks for protection of both the peroneal nerve and sural nerve have been described. The purpose of the current study is to assess the rate of injury to the peroneal and sural nerve following PL harvest using our technique in a large cohort of patients. This high-powered prospective cohort study provides the largest cohort to date for assessment of this complication. This should aid surgeons in clinical decision making regarding PL harvest complications.

Materials and Methods

Patient Selection and Follow-Up

A prospective cohort of 600 consecutive patients undergoing PLG harvest over a period from January 2022 to December 2022 at a single tertiary referral centre for primary ACL reconstruction was included for analysis. All harvests were conducted by a single surgeon (MA) using our technique for PL harvest [3]. Patients had baseline screening of nerve function prior to surgery and were regularly followed up at 3 weeks, 6 weeks, 3 months and 6 months post-harvest. Gender and playing profession (player vs non-player) were assessed as independent variables.

Inclusion criteria were: all patients undergoing PL harvest for any type of ligament surgery, adults > 18 years of age, written informed consent and willing to participate in follow-ups. We excluded patients with pre-existing neurological disorders, including diabetic neuropathy, with previous foot drops, with previous complaints of paraesthesia to the foot or leg and any adults < 18 years of age or unwilling to participate. Any patients with previous history of foot and ankle tendon transfer surgery or tendon ruptures were also excluded.

All patients were screened prior to surgery by a single consultant (TS) for assessment of pre-existing nerve injury to the ipsilateral leg. Complete neurological examination of the lower extremities was performed and any patients with pre-existing symptomatic paraesthesia or neurogenic symptoms were excluded from the study (n = 1).

Study Power Calculation

Using a correlation coefficient of 0.03 for studying the null hypothesis, we found the expected sample study size should be 214 patients for a high power and reduced error rate. Using 600 patients, the alpha score is < 0.01.

Harvest Technique and Safe Surgical Landmarks

Our technique for PL harvest has been previously published [3]. Key points include taking an incision 2 cm proximal to the lateral malleolus to reduce sural nerve injury risk and ending the harvest 5 cm distal to the fibular head to reduce peroneal nerve injury risk. One artery forceps were placed deep to the peroneus longus tendon and another artery forceps deep to the peroneus brevis tendon and both were delivered out of the skin to facilitate suture passage (Fig. 1). Tenodesis of the PL and peroneus brevis tendons at the distal end of the skin incision is performed in every case. Running whipstitch using Ethibond suture through the peroneus longus tendon is done. This is started 1 cm proximal to the tenodesis suture (Fig. 2). Usually three to four throws are adequate to prevent pullout during harvest. PLG harvest was done with the help of a closed tendon stripper. Further details can be found in the technique paper. This is a reliable and reproducible harvest technique which we have been using at our centre over the last 4 years.

Fig. 1.

Intra-operative picture showing the a peroneus longus and b peroneus brevis

Fig. 2.

Intra-operative picture showing the running whipstitch using Ethibond suture through the peroneus longus tendon 1 cm proximal to the tenodesis suture

Nerve Analysis

At each follow-up visit, the same screening consultant (TS) assessed the sensory and motor function for the peroneal and sural nerves specifically using pinprick, light touch, vibratory sense, and motor grading according to the NHMRC scale.

Any patient found to have symptomatic subjective or objective symptoms of nerve injury was sent for EMG NCV analysis. Serial EMG NCV analysis was conducted at each follow-up visit and all symptomatic patients were started on pregabalin 75mg OD at night for a period of 6 weeks to reduce symptoms.

Statistical Analysis of Data

All data related to the study were maintained electronically by TS and entered at each visit. The data set was extracted at the end of the study and divided into variables for analysis. Grouped variables for the sural and peroneal nerves were completed and analysis was carried out using Cochrane’s Q test and McNemar’s test. Cochrane’s Q test was used to determine if there was a differences in the dichotomous variables between three or more related groups in a longitudinal study design. A p value < 0.05 was used to quote the statistical significance. McNemar’s test was used as a post hoc test dividing the groups into pairs and the final resultant analysis was also divided into pairs to elicit differences. In our series, the number of pairs we compare is six, so with a p value of 0.05 the alpha value becomes 0.05/6 (= 0.0083). Hence with this test, a p value < 0.0083 is used for assessment of significance.

Results

Demographic Variables

All 600 patients included in the analysis were followed up till the completion of 6 months with no dropouts. The cohort data are presented in Table 1 with respect to gender and playing profession. Males (90.3%) and players (86.7%) constitute the bulk of the study cohort.

Table 1.

Demographic frequency data of the cohort according to gender (male vs female) and playing profession (player vs non-player)

| Frequency | Percent | Valid percent | Cumulative percent | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Valid | ||||

| Female | 58 | 9.7 | 9.7 | 9.7 |

| Male | 542 | 90.3 | 90.3 | 100.0 |

| Total | 600 | 100.0 | 100.0 | |

| Valid | ||||

| Non-player | 80 | 13.3 | 13.3 | 13.3 |

| Player | 520 | 86.7 | 86.7 | 100.0 |

| Total | 600 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

Baseline Screening

No patient had any pre-existing symptomatic or asymptomatic objective finding of nerve injury. One patient with pre-existing foot drop secondary to a primary PLC surgery was excluded from the study.

Follow-Up Screening

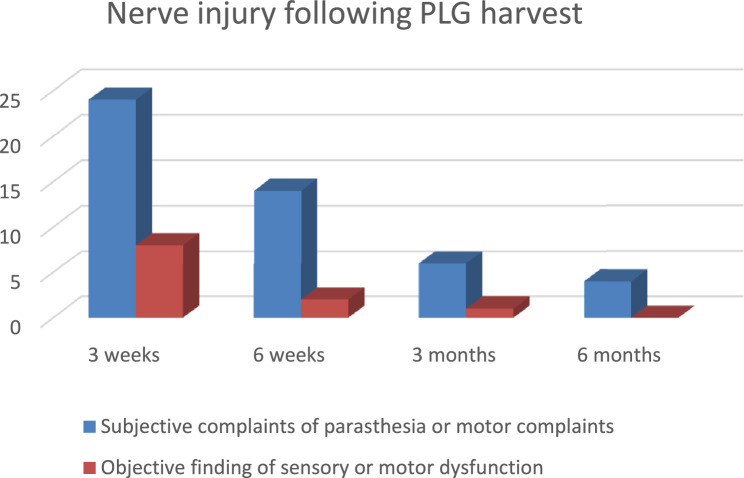

The follow-up screening data are presented in Table 2 and Fig. 3. At 3 weeks, 0.04% of patients had either subjective or subjective and objective complaints of nerve injury. This number reduced to 0.01% of the study cohort at 6 months follow-up. At each follow-up visit from 3 weeks onwards, there was a trend towards reduction in subjective or objective nerve complaints. No first metatarsal drop was reported in our study.

Table 2.

Frequency mapping of nerve complaints as percentage of the study cohort

| Follow-up interval | Subjective complaints of paraesthesia or motor complaints | Subjective + objective finding of sensory or motor dysfunction | Percentage of the total cohort (n = 600) (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3 weeks | 24 | 8 | 0.04 |

| 6 weeks | 14 | 2 | 0.03 |

| 3 months | 6 | 1 | 0.01 |

| 6 months | 4 | 0 | 0.01 |

Fig. 3.

Subjective and objective complaints of nerve injury by frequency

Peroneal Versus Sural Nerve Complaints

The proportions of nerve complaints according to peroneal or sural nerve involvement are presented in Table 3. At 3 weeks, 0.013% of the study population had peroneal nerve complaints which reduced at each follow-up to 0.002% at the end of the study duration. At 3 weeks, 0.027% of the study population had sural nerve complaints which also reduced at each follow-up to 0.005% at the end of the study duration. Three times more patients had sural nerve complaints than peroneal nerve complaints at the end of the 6 months follow-up.

Table 3.

Peroneal and sural nerve complaints as a percentage of the study cohort

| Peroneal nerve complaints (n) | Peroneal nerve complaints as % of the total cohort (%) | Sural nerve complaints | Sural nerve complaints as % of the total cohort (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 weeks (n = 24) | 8 | 0.013 | 16 | 0.027 |

| 6 weeks (n = 14) | 4 | 0.007 | 10 | 0.017 |

| 3 months (n = 6) | 1 | 0.002 | 5 | 0.008 |

| 6 months (n = 4) | 1 | 0.002 | 3 | 0.005 |

EMG-NCV and Manual Testing Findings at 3 Months and 6 Months for Residual Complaints

Objective study data are presented in Table 4. One patient had reduced nerve potentials on NCV analysis with no corresponding EMG effect at 3 months, which dissipated at the 6-month follow-up. This likely represents a recalcitrant neuropraxia type of injury (Grade 1) of the nerve and not a higher grade of injury. No other patient in the study had any objective complaints at either 3 months or 6 months follow-up.

Table 4.

Objective findings of patients at 3 months and 6 months of study duration

| Sensory loss (touch, proprioception OR vibration sense) | Motor loss (NHMRC grade < 5) | Sensory loss + motor loss | NCV reduced amplitudes | EMG reduced motor potentials | NCV reduced amplitudes + EMG reduced motor potentials | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 months (n = 1) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 months (n = 0) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Statistical Analysis of Data

Peroneal Nerve

Using McNemar’s test for statistical significance, we found a significant difference in peroneal nerve complaints between baseline and 3 weeks follow-up (Table 5), but no significant difference between baseline and any subsequent follow-ups. Further, there was no significant difference in the data set for any time period from 3 weeks or 6 weeks to each follow-up visit for the peroneal nerve groups with regard to subjective complaints.

Table 5.

Subjective complaints related to the peroneal and sural nerves between baseline and all follow-up visits and subjective complaints related to the sural nerve between follow-up intervals when compared to the 3-week and 6-week interval

| Baseline and peroneal subjective, 3 weeks | Baseline and peroneal subjective, 6 weeks | Baseline and peroneal subjective, 3 months | Baseline and peroneal subjective, 6 months | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subjective complaints related to the peroneal nerve between baseline and all follow-up visits | ||||

| N | 600 | 600 | 600 | 600 |

| Exact Sig. (2-tailed) | .008 | .125 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Baseline and sural subjective, 3 weeks | Baseline and sural subjective, 6 weeks | Baseline and sural subjective, 3 months | Baseline and sural subjective, 6 months | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subjective complaints related to the sural nerve between baseline and all follow-up visits | ||||

| N | 600 | 600 | 600 | 600 |

| Exact Sig. (2-tailed) | .000 | .016 | .063 | .250 |

| Sural subjective, 3 weeks and sural subjective, 6 weeks | Sural subjective, 3 weeks and sural subjective, 3 months | Sural subjective, 3 weeks and sural subjective, 6 months | Sural subjective, 6 weeks and sural subjective, 3 months | Sural subjective, 6 weeks and sural subjective, 6 months | Sural subjective, 3 months and sural subjective, 6 months | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subjective complaints related to the sural nerve between follow-up intervals when compared to the 3-week and 6-week interval | ||||||

| N | 600 | 600 | 600 | 600 | 600 | 600 |

| Exact Sig. (2-tailed) | .004 | .001 | .000 | .687 | .219 | .500 |

Sural Nerve

In the sural nerve group, a significant difference was observed between baseline and 3 weeks follow-up, but no difference was observed when comparing baseline to any subsequent follow-up. Further, when comparing the 3-week group to each subsequent follow-up, we found a significant difference at each interval; however, no such difference was observed when comparing the 6-week follow-up to either 3-month or 6-month follow-up (Table 5).

Subjective and Objective Complaints

When examining both subjective and objective complaints, there was a significant difference between the baseline group and the 3-week follow-up group, but no difference beyond the 3-week interval when compared to the baseline. Further, the 3-week group had a significant difference when compared to the 6-month group, but not to the 3-month group (Table 6).

Table 6.

Subjective and objective (s + o) complaints between follow-up intervals when compared to the baseline, 3-week and 6-week interval

| Baseline and s + o, 3 weeks | Baseline and s + o, 6 weeks | Baseline and s + o, 3 months | s + o, 3 weeks and s + o, 6 weeks | s + o, 3 weeks and s + o, 3 months | s + o, 3 weeks and s + o, 6 months | s + o, 6 weeks and s + o, 3 months | s + o, 6 weeks and s + o, 6 months | s + o, 3 months and s + o, 6 months | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 600 | 600 | 600 | 600 | 600 | 600 | 600 | 600 | 600 |

| Exact Sig. (2-tailed) | .008 | .500 | 1.000 | .031 | .016 | .008 | 1.000 | .500 | 1.000 |

Total Data Set Analysis

There was no significant changes when comparing the baseline data to the subjective, objective or subjective and objective data at 6 months follow-up for either the sural or the peroneal nerve groups (Table 7).

Table 7.

Total data set analysis when comparing baseline data to 6-month follow-up data

| Peroneal subjective: baseline versus 6 months | Peroneal objective: baseline versus 6 months | Peroneal subjective and objective: baseline versus 6 months | Sural subjective: baseline versus 6 monts | Sural objective: baseline versus 6 months | Sural subjective and objective: baseline versus 6 months | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 600 | 600 | 600 | 600 | 600 | 600 |

| Exact Sig. (2-tailed) | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

Sub-group Analysis of Gender and Playing Profession

There was no significant difference observed when comparing males versus females for either peroneal, sural or subjective and objective complaints with respect to baseline data. There was also no significant difference observed when comparing players and non-players for either peroneal, sural or subjective and objective complaints data with respect to baseline.

Discussion

Peroneus longus (PL) graft harvest is becoming an increasingly popular technique for ligament surgeries due to its ease of harvest, reproducible technique and graft diameters, and the low complication rates. However, apprehension of its more widespread usage persists due to the perceived impact on ankle function. Our group’s systematic review has shown that there is a negligible impact on ankle functional outcome scores post-PL harvest [1].

One of the main stigmas surrounding PL usage relates to the potential for nerve complications during harvest. The peroneal and sural nerves, by virtue of their anatomical course and relation to the peronei, are most at risk. The peroneal nerve passes around the biceps femoris muscle and runs in the peroneal tunnel between the peroneus longus muscle and its attachment to the fibular proximal portion [4, 5]. It is here that it is most vulnerable to damage due to excessive telescoping of the tendon stripper. A simple trick we use to minimize damage to the peroneal nerve during harvest is to mark a point 5 cm below the head of the fibula on the skin and ensure that our tendon stripper does not go beyond this point. If it reaches this point during harvest, a simple clockwise and anticlockwise manoeuvre of the tendon stripper can help release the muscle at this point along with a push–pull harvest technique rather than a plunge technique.

The sural nerve is a cutaneous sensory nerve which courses in the lateral retro-malleolar fat and is separated from the fibula by the peroneal tendons [6, 7]. It is here during the skin incision for peroneal harvest that the nerve is at the greatest risk for damage. Studies have shown that a point for skin incision marked starting 2cm proximal to the distal tip of the lateral malleolus and moving proximally places the nerve at a safe distance [2, 8]. In addition, a skin incision centred closer to the fibular posterior border and away from a direct incision over the peroneal tendon also minimizes risk. Both the techniques are used by us during harvest. In addition, we ensure that our stripping of the peroneal fascia is minimal and a simple knick is made in the fascia between the fibular and peroneal tendon to allow stripper passage [9].

The present prospective cohort study of 600 consecutive patients represents the largest sample size to date to assess nerve complications. Several important findings have emerged from this study. The overall nerve complication rate is extremely low. Only one in a thousand patients (or 0.01%) suffer any nerve complication, all subjective complaints, at 6 months duration. The low nerve complication rate in our study is much lower than the previous globally quoted rates for nerve complications following PLG harvest [2, 3]. Rates of as high as 15% have been reported in the global literature. We believe that our technique [3] using safe surgical landmarks for harvest while avoiding nerve complications and our high-volume PL harvest work may be the reasons. Most of the previous studies have relied on single case complications or have been done in a setup where PL harvest is not the preferred technique for the majority of surgeries. As such, the low user volume interface increases the risk of complications. Further, we believe that previously surgeons having suffered from catastrophic complications such as foot drop have chosen to highlight the complication skewing the literature in a negative direction. The weight of the present study with high power should be a significant addition to the present literature and provides a balanced approach to understanding nerve complications after PL harvest.

We found that the majority of nerve complications occur at 3 weeks post-operatively (0.04% of study cohort) which may be due to one of two reasons. Firstly, tendon stripper passage to the top of the fibular head may exert pressure symptoms on the peroneal nerve, which, being neuropraxic in nature, dissipate with time, or excessive retraction of the posterior retractor at the level of the skin incision may exert pressure on the sural nerve, which again being neuropraxic dissipates with time. The evidence to support these potential neuropraxic complaints is the lack of objective findings on EMG/NCV, specific tests or muscle testing of these patients in our study, and the significant decrease in the nerve complication cohort at each subsequent follow-up visit compared to the 3-week visit. There is no significant difference between the 6-week and 3-month or the 3-month and 6-month data, suggesting that the peak of complications occur in the first 3 weeks and by the 6th week the majority of these neuropraxic symptoms are gone. Only a single patient in our study cohort had a persisting subjective complaints without any evidence of objective neurological findings, suggesting there may be an underlying picture of malingering.

The sural nerve is three times more likely to be involved than the peroneal nerve. We believe that its superficial course at the level of the incision site and overzealous retraction of the posterior tissues during harvest may be the reasons. Further, we take extreme care to prevent any damage to the peroneal nerve during telescoping of the tendon stripper and the 5 cm cutoff mark is a dictum for us which may also explain the lower peroneal nerve complication rate as compared to the sural nerve rate. Gender and playing profession have no impact on the rate of nerve complications, which is what we would expect as this is a technique-driven complication and not a patient factor-related complication.

The limitation of this study is we did not do EMG/NCV testing for the entire cohort of 600 patients, which may have missed some patients with objective damage to the nerve without any subjective complaints. Further the 6 months duration could have been extended to a longer follow-up; however we felt that as the focus of the paper is on nerve complications, any significant nerve injuries must manifest or dissipate by the 6-month interval.

Conclusion

Peroneus longus harvest is a safe and reproducible technique with a low complication rate. The rate of nerve complications post-harvest is grossly overestimated in the literature secondary to low-powered and low evidence studies. Our high-powered cohort study of 600 patients provides the largest sample size to date with a focus on nerve complications after PL harvest. The peak neurological complaints occur at 3 weeks follow-up with significant decrease at each subsequent follow-up representing a neuropraxic type of picture. The overall nerve complication rate at the end of 6 months duration is only 1 in 1000 patients or 0.01% which is extremely low and much lower compared to literature rates. The sural nerve is three times at risk of damage during harvest compared to the peroneal nerve. We believe that using our safe surgical technique for PL harvest with respect to surface landmarks allows for PL harvest with a low nerve complication rate.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethical Standard Statement

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by the any of the authors.

Informed Consent

For this type of study informed consent is not required.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Saoji, A., Arora, M., Jain, G., & Shukla, T. (2023). There is a minimal difference in ankle functional outcomes after peroneus longus harvest: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Indian Journal of Orthopaedics. 10.1007/s43465-023-00982-8 10.1007/s43465-023-00982-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bither, N. (2023). Peroneus longus graft harvest: A technique note. Indian Journal of Orthopaedics. 10.1007/s43465-023-00920-8 10.1007/s43465-023-00920-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arora, M., & Shukla, T. (2023). Peroneus longus graft harvest: A technique note. Indian Journal of Orthopaedics,57(4), 611–616. 10.1007/s43465-023-00847-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hardin, J. M., & Devendra, S. (2023). Anatomy, bony pelvis and lower limb: Calf common peroneal nerve (common fibular nerve). In StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532968/

- 5.Van den Bergh, F. R. A., Vanhoenacker, F. M., De Smet, E., Huysse, W., & Verstraete, K. L. (2013). Peroneal nerve: Normal anatomy and pathologic findings on routine MRI of the knee. Insights Into Imaging,4(3), 287–299. 10.1007/s13244-013-0255-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miniato, M. A., & Nedeff, N. (2023). Anatomy, bony pelvis and lower limb: Sural nerve. In StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK546638/ [PubMed]

- 7.Jackson, L. J., Serhal, M., Omar, I. M., Garg, A., Michalek, J., & Serhal, A. (2023). Sural nerve: Imaging anatomy and pathology. British Journal of Radiology,96(1141), 20220336. 10.1259/bjr.20220336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.He, J., Byrne, K., Ueki, H., Kanto, R., Linde, M. A., Smolinski, P., et al. (2022). Low to moderate risk of nerve damage during peroneus longus tendon autograft harvest. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy,30(1), 109–115. 10.1007/s00167-021-06698-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arora, M. (2023). Letter to the Editor: Importance of peroneal fascia closure in peroneal longus graft harvest. Indian Journal of Orthopaedics,57(12), 2095–2095. 10.1007/s43465-023-01043-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]