Abstract

Background

Substantial evidence supports that glaucoma and dementia share pathological mechanisms and pathogenic risk factors. However, the association between glaucoma, cognitive decline and dementia has yet to be elucidated.

Objective

This study was aimed to assess whether glaucoma increase the risk of dementia or cognitive impairment.

Methods

PubMed, Cochrane Library, Web of Science, and EMBASE databases for cohort or case-control studies were searched from inception to March 10, 2024. The Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale (NOS) was used to the risk of bias. Heterogeneity was rigorously evaluated using the I2 test, while publication bias was assessed by visual inspection of the funnel plot and by Egger’ s regression asymmetry test. Subgroup analyses were applied to determine the sources of heterogeneity.

Results

Twenty-seven studies covering 9,061,675 individuals were included. Pooled analyses indicated that glaucoma increased the risk of all-cause dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, vascular dementia, and cognitive impairment. Subgroup analysis showed that the prevalence of dementia was 2.90 (95% CI: 1.45–5.77) in age ≥ 65 years and 2.07 (95% CI: 1.18–3.62) in age<65 years; the incidence rates in female glaucoma patients was 1.46 (95% CI: 1.06-2.00), respectively, which was no statistical significance in male patients. Among glaucoma types, POAG was more likely to develop dementia and cognitive impairment. There were also differences in regional distribution, with the highest prevalence in the Asia region, while glaucoma was not associated with dementia in Europe and North America regions.

Conclusion

Glaucoma increased the risk of subsequent cognitive impairment and dementia. The type of glaucoma, gender, age, and region composition of the study population may significantly affect the relationship between glaucoma and dementia.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40520-024-02811-w.

Keywords: Glaucoma, Dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, Cognitive impairment, Meta-analysis

Introduction

Dementia, a growing global public health problem, affects approximately 50 million people. As life expectancy rises, the number of dementia cases worldwide is expected to skyrocket to more than 131 million by 2050 [1]. As a neurodegenerative disease, the widespread prevalence of dementia places a significant strain on global healthcare systems. Due to the lack of effective treatments and preventive interventions, identifying potential risk factors for dementia is critical for dementia prevention. However, no disease-modifying treatments are currently available for adults with dementia; thus, an emphasis on risk factor reduction, particularly modifiable risk factors, is warranted. According to recent research, visual impairment is one of the first symptoms of dementia [2]. Visual deprivation caused by retinal ganglion cell (RGC) injury may result in decreased activation of central sensory pathways in the brain, resulting in decreased cognitive load and an increased risk of structural brain damage, accelerating the progression of dementia [3, 4].

Glaucoma is a group of diseases characterized by optic papillary atrophy and depression, as well as retinal ganglion cell (RGC) death and visual field defects, which is the most common cause of irreversible blindness worldwide. Clinically, it is classified as open-angle glaucoma or angle-closure glaucoma based on the status of the anterior chamber angle at the time of elevated intraocular pressure [5, 6]. Despite extensive multicenter and laboratory studies showing that pathological intraocular pressure (IOP) elevation is a significant risk factor for the development and progression of the disease, lowering IOP does not always stop the disease [7]. In glaucoma patients, progressive loss of visual function is associated with RGC degeneration, characterized by apoptosis of retinal somatic cells, axonal degeneration of the optic nerve, and synaptic loss of dendrites and synaptic loss of axon terminals. In addition, glaucoma-related neuronal damage extends to the lateral geniculate nucleus and visual cortex and is accompanied by astrocyte and retinal microglia changes [8–10]. Axonal transport defects have also been linked to several neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and other dementias. Although inconclusive, numerous research have been conducted to support the common pathophysiological features of dementia and glaucoma regarding age-related biological features and cell death mechanisms in the central nervous system [11].

Several cross-sectional studies have found that glaucoma is associated with deficits in a variety of cognitive functions, including attention, language, learning, and memory skills [12–15]. In a study of 1,168 elderly patients, Mandas et al. found a significant association between glaucoma and the prevalence of mixed dementia [16]. Furthermore, neuropathological studies have revealed hyperphosphorylated tau proteins, increased amyloid fragmentation, microglia activation, neurodegeneration, and apoptosis in the retinas of glaucoma patients. However, existing evidence does not explain the causal relationship between glaucoma and dementia or cognitive impairment, and findings are inconsistent [17–19]. For example, in a cross-sectional study in Denmark, Bach-Holm et al. followed 69 elderly patients with normal IOP glaucoma for 12 years and found no correlation between glaucoma and dementia [20]. Ong et al. followed 1179 older adults with age-related eye disease in Singapore and suggested no significant correlation [21]. The relationship between glaucoma and dementia or cognitive impairment remains controversial.

Growing evidence suggests that glaucoma and dementia share pathological mechanisms and pathogenic risk factors. Nevertheless, previous studies reported inconsistent results regarding the association between glaucoma and dementia or cognitive impairment [22]. Clarifying the effects of glaucoma on subsequent secondary cognitive impairment or dementia is critical for preventing and delaying the progression of these diseases. Therefore, we performed a systematic review and meta-analysis to assess the association of glaucoma with dementia or cognitive impairment.

Methods

This current systematic review conformed to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [23] and was registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/ PROSPERO (Registration number: CRD 42,023,408,202).

Search strategy

Both Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms and keywords were utilized to retrieve as many as possible in PubMed, Web of Science, EMBASE, and Cochrane Library for case-control or cohort studies exploring the relationship between glaucoma and dementia or cognitive impairment published from their inception to March 10, 2024. The main terms included “glaucoma,” “dementia,” “Alzheimer’s disease,” “vascular dementia,” “senile dementia,” “cognitive decline,” “cognitive impairment,” “cognitive dysfunction,” and “cognitive disorder.” A further gray literature search was conducted using Google Scholar to identify relevant articles not found through the database search. References and citations of relevant publications identified for inclusion and reviews on this topic were scrutinized. English and Chinese language publications were included. The detailed search strategy is presented in Supplementary Table 1.

Eligibility criteria

The included studies were required to meet the following criteria: (1) case-control or cohort study design; (2) exposure factors were glaucoma with incident dementia or cognitive impairment, and the control group included participants without glaucoma; (3) report risk estimates of dementia or cognitive decline as the outcome (i.e., at least all-cause dementia or Alzheimer’s disease as its most common subtype), expressed as an adjusted odds ratio (OR), risk ratio (RR), or hazard ratio (HR); (4) population-based study design; (5) English publication.

Exclusion criteria

The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) conference abstract, reviews, case reports, basic experiments and other non-clinical research; (2) duplicate publications; (3) studies with incomplete data or no relevant outcome.

Study selection and data extraction

All retrieved records were imported into an EndNote (Clarivate Analytics) library, and two researchers (WXR and CWJ) independently screened the literature, extracted data, and cross-checked. Discussions were cross-verified by a third researcher in the event of disagreement. When screening literature, first read the title and abstract, and after excluding irrelevant literature, further, read the full text to determine what is ultimately included. (1) Basic information: first author, publication year, country, study type; (2) Characteristics of included studies: sample size, gender, age, follow-up years, diagnostic criteria for glaucoma, dementia, or cognitive impairment, and adjusted covariates; (3) Key elements of risk of bias assessment; and (4) Effect sizes and their 95% confidence intervals (CI) after controlling for confounding factors.

Data synthesis

Following the PRIMA 2020 guidelines, the selection process was documented using a “flow diagram” showing the number of references excluded at each step. Reasons for study exclusion after full-text assessment are reported in detail. In addition, the extracted data were tabulated and summarized in text. Moreover, the results of the statistical analysis are presented in both tables and figures (detailed below).

Assessment of risk of bias

To determine the validity of the included studies, two independent investigators assessed the risk of bias (RoB) using the Newcastle-Ottawascale Scale (NOS) [24] and cross-checked the results. In the case of any disagreement, a third party was consulted to assist in the decision. The evaluation was conducted in three parts with eight items, with scores ranging from 0 to 4 indicating low quality, 5 to 6 indicating medium quality, and 7 to 9 indicating high quality. Each study was assigned a risk of bias rating - high, moderate, or low - based on responses to each question.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted by using RevMan 5.3 and State 17.0 software. The primary outcome indicators were the pooled odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence interval (95% CI) with adjusted confounders. We formally assessed between-study heterogeneity (chi-square test, α = 0.1) to determine the share of variation across studies due to heterogeneity rather than chance (Higgins’ I2 statistic) and interpreted heterogeneity as potentially insignificant (40%), moderate (30-60%), significant (50-90%), or considerable (75-100%), in line with Cochrane recommendations [25]. If P > 0.05 or I2 < 50%, there was no statistical heterogeneity between studies, and a fixed-effects model was selected. When clinical or statistical heterogeneity occurred, a random-effects meta-analysis was used. An α-level of 0.05 was used to determine statistical significance. We visually examined funnel plot asymmetry and performed Egger’s regression test to detect statistical publication bias (Lin et al., 2018). To confirm the robustness of the overall results, we performed a sensitivity analysis by rerunning the meta-analysis while omitting one study at a time, or by trim-and-fill method. Given that the study region, type of glaucoma, type of dementia, gender, age, sample size, and follow-up time could affect the findings of the study, we performed subgroup analyses to explore sources of heterogeneity.

Results

Literature search

In summary, the search retrieved 4,216 records from electronic databases. No additional articles were included based on reference screening and expert consultation. After removing duplicates, 3,467 publications were initially screened by reading the titles and abstracts of the literature. Using the above inclusion/exclusion criteria, the full texts of 54 articles were evaluated, and 27 studies were eventually included. There were twenty cohort studies [26–45] and seven case-control studies [46–52] involving 9,061,675 participants (Fig. 1). The detailed exclusion list is provided in Supplementary Table 2.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of the study selection process

Main characteristics of included studies

Across the included studies, there were 9,061,675 participants aged 18 years or older, with the proportion of male participants ranging from 35.01 to 54.66%. The study populations were from China (n = 8) [33, 34, 36, 40, 42, 48, 49, 51] the United States (n = 5) [31, 32, 38, 39, 46], Sweden (n = 5) [26, 30, 44, 45, 50], Korea (n = 3) [27, 28, 35], the United Kingdom (n = 2) [28, 37], Australia (n = 1) [52], France (n = 2) [43, 47], and Denmark (n = 1) [41]. These articles were published from 2007 to 2024, with sample sizes ranging from 509 to 2,623,130, and the mean follow-up time varied from 3 to 14 years.

Most of these studies used the International Classification of Diseases-9 (ICD-9) or International Classification of Diseases-10 (ICD-10) diagnosis codes as glaucoma and dementia diagnostic criteria. However, seven studies [30, 31, 43, 44, 45,, 51, 52] used ophthalmologic examinations to assess glaucoma, one [36] used self-administered questionnaires only to determine glaucoma, and four [32, 36, 51, 52] used MMSE/McOA scores to diagnose dementia and cognitive impairment. All studies examined the association between glaucoma and dementia or cognitive impairment as a dichotomous variable among the outcome indicators. In 24 studies [26–45, 47, 50], the outcome measures were dementia and cognitive impairment in three [46, 51, 52]. The main characteristics of the included studies are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Basic characteristics of the included studies

| Authors | Country | Study design | Sample size (exposed/ control) | Age (years) | Follow-up years | Diagnosis of glaucoma | Diagnosis of dementia /cognitive impairment | Glaucoma type | Outcome | Variables adjusted |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Crump et al. 2024 |

Sweden | Retrospective cohort study |

32,339/ 226,896 |

- | 22 | ICD−9/ICD−10 |

ICD-9/ ICD-10 |

POAG/ PACG |

All-cause dementia /AD/VD |

age, sex, birth country, education, income, hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, ischemic heart disease, and Charlson Comorbidity Index at index date |

| Kim et al. 2023 | Korea | Prospective cohort study |

875/ 3,500 |

≥ 55 | 8 | ICD-10 | ICD-10 |

POAG/ PACG |

All-cause dementia /AD |

age, gender, sex, residence, and household income |

| Park et al. 2023 | Korea | Retrospective cohort study | 788,961 | ≥ 45 | 10.9 ± 2.7 | ICD-10 | ICD-10 | Glaucoma |

All-cause dementia /AD/VD |

age, sex, and income level, diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, stroke, chronic heart disease, depression, smoking status, drinking habits, body mass index, diabetic retinopathy, age-related macular degeneration, and visual acuity |

| Shang et al. 2023 | UK | Retrospective cohort study |

6,386/ 87,602 |

63.4 ± 4.0/ 62.0 ± 4.0 |

10.7–11.7 | ICD-10 | ICD-10 | Glaucoma | All-cause dementia | age, gender, education, income, cooked vegetables intake, raw vegetables intake, fresh fruits intake, dried fruits intake, smoking, alcohol consumption, physical activity, BMI, cholesterol and glucose |

| Ekström et al. 2021 | Sweden | Retrospective cohort study |

264/ 1,269 |

65–74 | 13 | Perimetry | ICD-10 | POAG | AD | age, a time-dependent variable, and competing events |

| Belamkar et al.2021 | UAS | Retrospective cohort study | 509 | 67.5 | 10 | Eye examination with IOP | DSM-5 | POAG | AD | |

| Hwang et al. 2021 | USA | Retrospective cohort study |

601/ 571 |

75.2 ± 4.8/ 74.4 ± 4.9 |

6–8 | ICD-9 |

MRI/ MMSE |

Glaucoma |

All-cause dementia /AD/VD |

age, sex, race, education, cardiovascular and dementia risk factors, smoking status, alcohol intake, physical activity level, total cholesterol level, diabetes mellitus status, hypertension statue. and cardiovascular diseases |

|

Su et al. 2016 |

China | Retrospective cohort study |

6,509/ 26,036 |

59 | 10 | ICD-9-CM | ICD-9-CM |

POAG、 PACG |

All-cause dementia | age, gender, hypertension, diabetes, coronary heart disease, hyperglycaemia, and head injury |

| Chen et al. 2018 | China | Retrospective cohort study |

15,317/ 61,268 |

62.1 ± 12.5 | 4.92 ± 3.29 | ICD-9-CM | ICD-9 |

POAG (NTG) |

AD | age, gender, hypertension, diabetes, hyperglycaemia, coronary artery disease, and stroke |

|

Moon et al. 2018 |

Korea | Retrospective cohort study |

1,469/ 7,345 |

≥ 18 | 12 | KCD | KCD | POAG | AD | age, sex, residential area, income, Charleston comorbidity index, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hyperglycaemia and ischemic |

| Xiao et al. 2020 | China | Retrospective cohort study | 1,062 | 71.5 ± 7.4 | 5.2 | self-report questionnaire |

DSM-IV/ MMSE |

Glaucoma |

All-cause dementia /AD |

age, sex, education year, cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, BMI, depression, and heart |

| Keenan et al. 2014 | UK | Retrospective cohort study |

87,658/ 2,535,472 |

≥ 55 | 12 | ICD-10 | ICD-10 | POAG | AD/VD | |

| Lee et al. 2018 | USA | Prospective cohort study | 3,877 | ≥ 65 | 8 | ICD-9 |

NINCDS- ADRDA |

Glaucoma | AD | |

| Ou et al. 2012 | USA | Retrospective cohort study |

63,325/ 63,325 |

78.5 | 14 | ICD−9 | ICD-9 | POAG |

All-cause dementia /AD |

|

| Lin et al. 2014 | China | Retrospective cohort study |

3,979/ 15,916 |

71.3 ± 7.08/ 71.3 ± 7.41 |

8 | ICD−9-CM | ICD-9-CM | POAG | AD | age, sex, hypertension, diabetes, heart failure, stroke, insurance eligibility group, monthly income, urbanization level and Charleston commodities index |

|

Kessing et al. 2007 |

Denmark | Retrospective cohort study | 410,544 | 68.2 | 4.6 |

ICD-8 or ICD-10 |

ICD-8 or ICD-10 |

PACG |

All-cause dementia /AD/VD |

age, sex, time from discharge, and a diagnosis of substance use |

| Kuo et al. 2020 | China | Retrospective cohort study |

21,024/ 21,024 |

≥ 20 | 16 | ICD−9/ICD−10 |

ICD-9/ ICD-10 |

Glaucoma |

All-cause dementia /AD/VD |

age, sex, education, marry, hypertension, ischemic heart diseases, hyperglycaemia, congestive heart failure, peripheral vascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, and hemiplegia or paraplegia |

| Helmer et al. 2013 | France | Prospective cohort study | 8,12 | 79.7 ± 4.3 | 3 | Eye examination with IOP | DSM-IV | POAG | All-cause dementia | age, sex, education, hypertension, diabetes, history of cardiovascular ischemic disease, history of stroke, familial history of glaucoma, and apolipoprotein |

| Ekstrom and Kilander 2016 | Sweden | Retrospective cohort study | 1,533 | 65–74 | 30 | Eye examination | Medical chart evaluation | POAG | AD | age, gender, participating in the population survey, smoking habits, diabetes mellitus, systemic hypertension, ischemic heart disease |

| Ekström and Kilander 2014 | Sweden | Retrospective cohort study | 1,123 | 65–74 | 14.0 ± 6.4 | Eye examination with IOP | ICD-9 | POAG | AD | |

|

Umunakwe et al. 2020 |

USA | Case-control study |

24,892/ 1,484,790 |

58.9 ± 14.0/ 44.9 ± 14.1 |

4.7 | ICD-9/ICD-10 |

ICD-9/ ICD-10 |

POAG |

VD/AD/ cognitive impairment |

age, race, and gender |

|

Chamard et al. 2023 |

France | Case-control study |

4,810/ 24,050 |

≥ 60 | 7 | ICD-10 | ICD-10 | Glaucoma | All-cause dementia |

overweight or obesity, diabetes, antihypertensives, hypolipidemic drugs, chronic kidney disease, stroke, coronary heart disease, heart failure, heart rhythm disorders, heart conduction disorders, lower extremity arterial disease, depression or bipolar disorder, psychotic disorders, Diamox, benzodiazepines cDDD levels and anticholinergics cDDD levels. |

| Chung et al. 2015 | China | Case-control study |

264/ 15,276 |

76.8 ± 9.6 | 6 | ICD-9 | ICD-9 | POAG | All-cause dementia | urbanization level, monthly income, geographic region, hypertension, diabetes, hyperglycaemia, tobacco use disorder, and alcohol abuse, and the number of outpatient visits within 1 year prior to index date |

| Lai et al. 2017 | China | Case-control study | 6,680 |

78.0 ± 6.7/ 78.7 ± 6.6 |

11 | ICD-9 | ICD-9 | Glaucoma | AD | age |

| Wändell et al. 2022 | Sweden | Case-control study |

7,791/ 1,695,884 |

>18 | 6 | ICD-10 | ICD10 | POAG | AD | |

| Wang et al. 2021 | China | Case-control study | 116/2,959 | 69.42 ± 6.77 | - | Eye examination |

MMSE /MoCA |

Glaucoma | Cognitive impairment | |

|

Mullany et al. 2022 |

Australia | Case-control study | 144/146 | ≥ 65 | - | Eye examination with IOP | T- MoCA | POAG | Cognitive impairment |

Abbreviations POAG: primary open-angle glaucoma; PACG: primary angle-closure glaucoma; AD: Alzheimer’s disease; VD: vascular dementia; SD: senile dementia; ICD-8/9/10: International Classification of Diseases, version 8/9/10; MMSE: Mini-mental State Examination; MoCA: Montreal Cognitive Assessment; DSM-IV: Diagnostic Statistical Manual Mental Disorders IV; KCD: Korean Classification of Diseases; NINCDS-ADRDA: National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke–Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; IOP: Intra-ocular Pressure; BMI: Body Mass Index

Methodology quality assessment

The NOS scale was used to assess the quality of the included studies, and the results are presented in Tables 2 and 3. Twenty-one studies [26–36, 38–45, 48, 49] with a quality score ≥ 7 were classified as high quality, five [37, 47, 50–52] with a quality score of 6, and one [46] with a quality score of 5 was classified as moderate quality. In terms of study population selection, four cohort studies [32, 33,, 36, 41] had dementia at baseline selection, three case-control studies [49, 51, 52] did not specify the definition of the control group, and one case-control study [52] did not explicitly describe the selection of the control population. In terms of comparability, six cohort studies [28, 32, 36–38, 44] and five case-control studies [45, 48, 49, 51, 52] were at risk of bias due to incomplete adjustment for confounding factors. Regarding outcomes, two studies [42, 43] were at risk of bias due to insufficient follow-up time. The mean quality score of the 27 studies was 7.59, indicating overall high methodological quality (Table 3).

Table 2.

Methodological quality assessment results of the included cohort studies

| Author, year | NOS selection domain | NOS comparability domain |

NOS outcome domain | Total scores | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Representativeness of the exposed cohort | Selection of the non-exposed cohort | Ascertainment of exposure | Outcom not present at start | Comparability of cohorts on the basis of the design or analysis | Assessment of outcome |

follow-uplong enough for outcomes to occur (median ≥ 5 years) |

Adequacy of follow-up of cohorts | ||

|

Crump et al. 2024 |

☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | 9 |

| Kim et al. 2023 | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | 8 |

| Park et al. 2023 | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆☆ | ☆ | ☆ | 8 | |

|

Shang et al. 2023 |

☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | 9 |

|

Ekström et al. 2021 |

☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | 9 |

|

Belamkar et al.2021 |

☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | 7 | |

| Hwang et al. 2021 | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | 8 | |

| Su et al. 2016 | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆☆ | ☆ | ☆ | 8 | |

| Chen et al. 2018 | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆☆ | ☆ | ☆ | 8 | |

| Moon et al.2018 | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | 9 |

| Xiao et al. 2020 | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | 8 | |

|

Keenan et al. 2015 |

☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | 6 | ||

| Lee et al. 2018 | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | 7 | |

| Ou et al. 2012 | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | 8 |

| Lin et al. 2014 | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | 9 |

| Kuo et al. 2020 | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | 9 |

|

Helmer et al. 2013 |

☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆☆ | ☆ | ☆ | 8 | |

|

Kessing et al. 2007 |

☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆☆ | ☆ | 7 | ||

| Ekstrom and Kilander 2016 | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆☆ | ☆ | ☆ | 7 | ||

| Ekström and Kilander 2014 | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | 8 |

Table 3.

Methodological quality assessment results of the included case-control studies

| Author, year | Selection | Comparability | Exposure | Total scores | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case definition and diagnosis | Representativeness of cases | Selection of control | Definition of control | Comparability of case and control | Identification of exposure factors | Investigation methods of case and control | Non-response rate | ||

|

Umunakwe et al. 2020 |

☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | 5 | |||

|

Chamard et al. 2023 |

☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | 6 | ||

| Chung et al. 2015 | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆☆ | ☆ | ☆ | 8 | |

| Lai et al. 2017 | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | 7 | |

| Wändell et al. 2022 | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | 6 | ||

| Wang et al. 2021 | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | 6 | ||

| Mullany et al. 2022 | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | 6 | ||

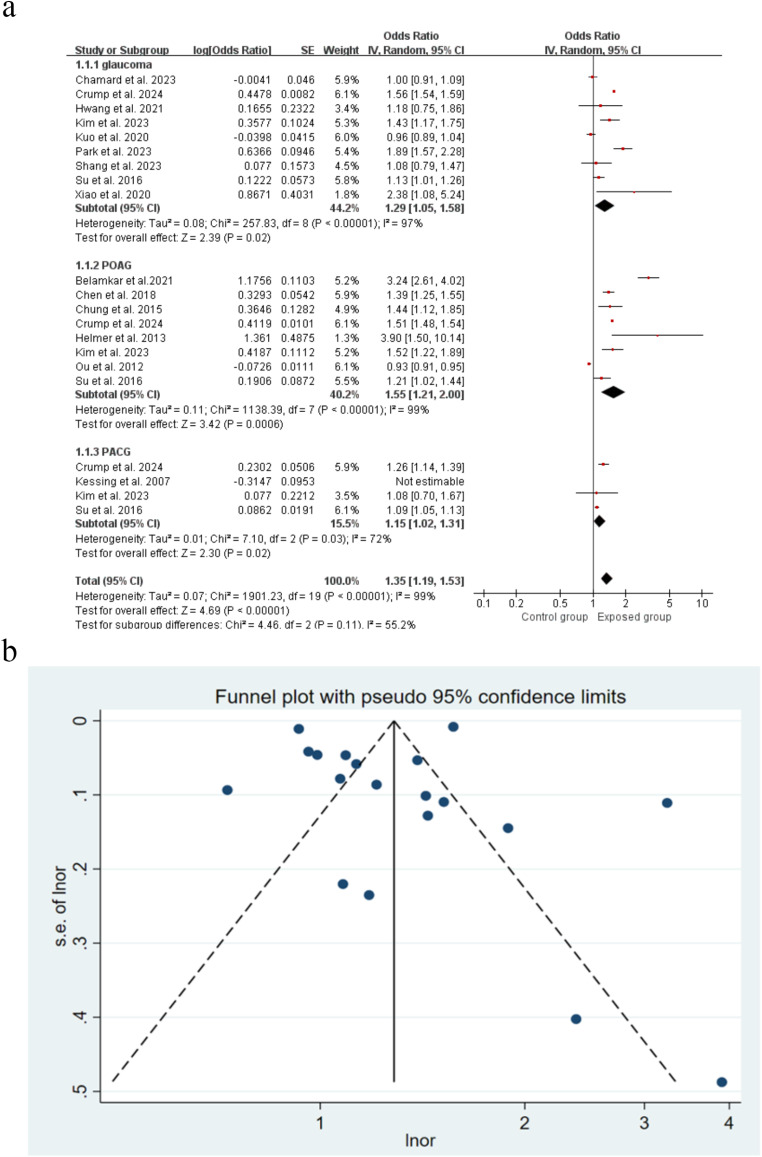

Association between glaucoma and risk of all-cause dementia

A total of 18 studies evaluated all-cause dementia as an outcome. Of these, 11 studies showed that glaucoma was associated with an increased risk of all-cause dementia, with effect estimates (OR) ranging from 1.09 (95% CI: 1.15˗1.13) to 3.90 (95% CI: 1.50˗10.14). In general, glaucoma was associated with an increased risk of all-cause dementia (OR = 1.31, 95% CI: 1.16˗1.48, P < 0.0001) (Fig. 2). Sensitivity analysis was performed by the trim-and-fill method, and the combined random-effects model resulted in a log OR = 0.259, 95% CI: 0.125˗0.393. After two iterations with the Linear method, the shear-complement method did not add to the study, indicating that the overall results were relatively robust (Supplementary Figure S1). Plotting funnel plots to test for publication bias showed that the distribution of studies was largely symmetrical (Fig. 2). Combining Egger’s test (P = 0.710) suggested a low likelihood of publication bias.

Fig. 2.

Forest plot and Funnel plot showing the effect of glaucoma on all-cause dementia

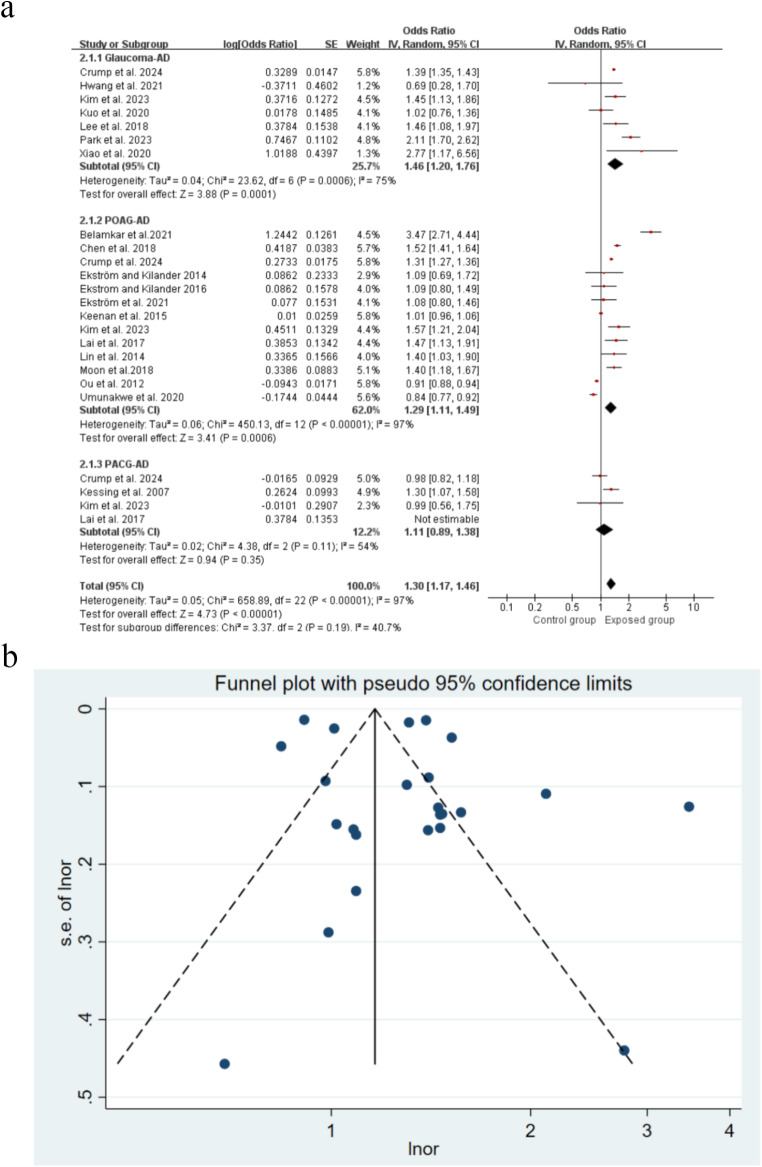

Association between glaucoma and risk of Alzheimer’s disease

There were 24 studies included, and the results revealed a strong link between glaucoma and an increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease (OR = 1.30, 95% CI: 1.17˗1.46, P<0.00001) (Fig. 3). For sensitivity analysis, using a study-by-study exclusion approach, the combined ORs ranged from 1.29 (1.13˗1.47) to 1.35 (1.15˗1.59) (Supplementary Figure S2). The funnel plot was roughly symmetrical (Fig. 3), and Egger’s test (P = 0.07) indicated that publication bias was unlikely.

Fig. 3.

Forest plot and Funnel plot showing the effect of glaucoma on Alzheimer’s disease

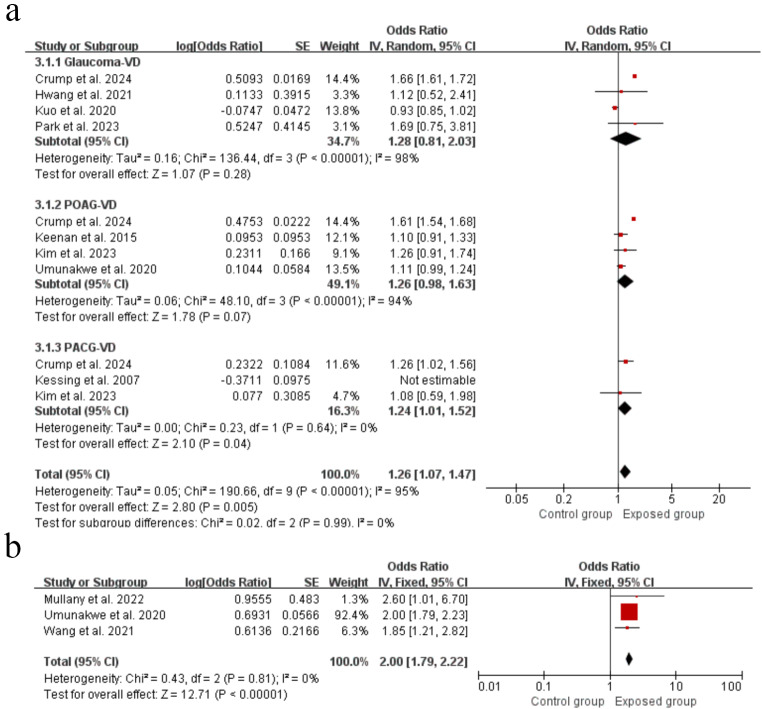

Association between glaucoma and risk of vascular dementia

There was significant link between glaucoma and the risk of vascular dementia (OR = 1.26, 95% CI: 1.07˗1.47, P = 0.005) (Fig. 4). Removing one study at a time did not have a statistically significant effect on the size of the aggregated results in the sensitivity analysis (Supplementary Figure S3). Regarding publication bias, Egger’s test (P = 0.436) also suggested no publication bias .

Fig. 4.

Forest plots showing the effect of glaucoma on vascular dementia (a) and cognitive impairment (b)

Association between glaucoma and risk of cognitive impairment

Three studies with a total of 1,513,047 patients were included, and the result revealed that glaucoma patients had twice the risk of cognitive impairment as the general population (OR = 2.00, 95% CI: 1.79˗2.22, P<0.00001) (Fig. 4). Egger’s test (P = 0.800) indicated that there was no significant publication bias.

Subgroup analysis

Subgroup analysis revealed that the type of glaucoma, gender, age and region of the study population significantly influenced the relationship between glaucoma and dementia. The pooled results showed that primary open-angle glaucoma increased the risk of all-cause dementia (OR = 1.55, 95% CI: 1.21˗2.00, P = 0.0006), Alzheimer’s disease (OR = 1.29, 95% CI: 1.11˗1.49, P = 0.0006), and cognitive impairment (OR = 2.00, 95% CI: 1.79˗2.22, P<0.0001), while angle-closure glaucoma increased the risk of vascular dementia (OR = 1.24, 95% CI: 1.01˗1.52, P = 0.04). Concerning gender, female glaucoma patients were more likely to develop Alzheimer’s disease (OR = 1.82, 95% CI: 1.47˗2.26, P<0.00001), whereas there was no significant link between male glaucoma patients and dementia. According to age subgroup analyses, glaucoma patients aged ≥ 65 or < 65 both had a significantly increased risk of all-cause dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. In addition, we found that the glaucoma patients in Asia had a 29% increased risk of all-cause dementia, and a 48% increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease compared to those without the visual condition. In Europe and North America, nevertheless, there was no correlation between glaucoma and dementia. The results from subgroup analyses by sample size and follow-up time showed no statistically significant differences regarding the impact of glaucoma on dementia in the subgroups, and they were not the source of heterogeneity (Table 4).

Table 4.

Subgroup analyses of the influence of glaucoma on dementia

| Variable | Number of studies | Heterogeneity | Effect model | Mate-analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pooled OR (95% CI) | P-value | |||||

| (Types of dementia) | ||||||

| All-cause dementia | 18 | P<0.00001; I2 = 99% | random-effects model | 1.35(1.19, 1.53) | <0.00001 | |

| Alzheimer’s disease | 24 | P<0.00001; I2 = 97% | random-effects model | 1.30(1.17, 1.46) | <0.00001 | |

| Vascular dementia | 11 | P<0.00001; I2 = 95% | random-effects model | 1.26(1.07, 1.47) | 0.005 | |

| Types of glaucoma | ||||||

| POAG | All-cause dementia | 8 | P<0.00001; I2 = 99% | random-effects model | 1.55(1.21, 2.00) | 0.0006 |

| Alzheimer’s disease | 13 | P<0.00001; I2 = 97% | random-effects model | 1.29(1.11, 1.49) | 0.0006 | |

| Vascular dementia | 4 | P<0.00001; I2 = 94% | random-effects model | 1.26(0.98, 1.63) | 0.07 | |

| PACG | All-cause dementia | 4 | P<0,001; I2 = 88% | random-effects model | 1.03(0.86, 1.48) | 0.74 |

| Alzheimer’s disease | 3 | P = 0.11; I2 = 54% | random-effects model | 1.11(0.89, 1.38) | 0.35 | |

| Vascular dementia | 3 | P = 0.64; I2 = 0% | fixed-effects model | 1.24(1.01, 1.52) | 0.04 | |

| Sex | ||||||

| Man | Overall | 11 | P<0.00001; I2 = 93% | random-effects model | 1.07(0.97, 1.19) | 0.17 |

| All-cause dementia | 6 | P<0.00001; I2 = 95% | random-effects model | 1.04(0.84, 1.27) | 0.74 | |

| Alzheimer’s disease | 5 | P<0.00001; I2 = 89% | random-effects model | 1.21(0.94, 1.57) | 0.14 | |

| Woman | Overall | 10 | P<0.00001; I2 = 98% | random-effects model | 1.46(1.06, 2.00) | 0.02 |

| All-cause dementia | 7 | P<0.00001; I2 = 98% | random-effects model | 1.34(0.91, 1.98) | 0.14 | |

| Alzheimer’s disease | 3 | P = 0.37; I2 = 0% | fixed-effects model | 1.82(1.47, 2.26) | <0.00001 | |

| Age | ||||||

| ≥ 65 years | Overall | 7 | P<0.00001; I2 = 99% | random-effects model | 2.90(1.45, 5.77) | 0.003 |

| All-cause dementia | 3 | P<0.00001; I2 = 93% | random-effects model | 1.26(1.13, 1.41) | <0.0001 | |

| Alzheimer’s disease | 4 | P<0.00001; I2 = 98% | random-effects model | 4.53(1.08, 19.04) | 0.04 | |

| <65 years | Overall | 6 | P<0.00001; I2 = 95% | random-effects model | 2.07(1.18, 3.62) | 0.01 |

| All-cause dementia | 3 | P = 0.74; I2 = 0% | fixed-effects model | 1.49(1.25, 1.77) | <0.00001 | |

| Alzheimer’s disease | 3 | P<0.00001; I2 = 97% | random-effects model | 3.01(1.11, 8.85) | 0.03 | |

| Sample size | ||||||

| ≥ 10,000 | All-cause dementia | 12 | P<0.00001; I2 = 99% | random-effects model | 1.16(0.97, 1.39) | 0.10 |

| Alzheimer’s disease | 9 | P<0.00001; I2 = 99% | random-effects model | 1.22(1.02, 1.45) | 0.03 | |

| Vascular dementia | 6 | P<0.00001; I2 = 98% | random-effects model | 1.10(0.80, 1.52) | 0.55 | |

| <10,000 | All-cause dementia | 7 | P<0.00001; I2 = 87% | random-effects model | 1.78(1.24, 2.54) | 0.002 |

| Alzheimer’s disease | 12 | P<0.00001; I2 = 82% | random-effects model | 1.43(1.15, 1.79) | 0.001 | |

| Vascular dementia | 3 | P = 0.89; I2 = 0% | fixed-effects model | 1.20(0.92, 1.58) | 0.17 | |

| Mean follow-up time | ||||||

| ≥ 10 years | All-cause dementia | 8 | P<0.00001; I2 = 97% | random-effects model | 1.28(1.11, 1.48) | 0.0008 |

| Alzheimer’s disease | 11 | P<0.00001; I2 = 95% | random-effects model | 1.35(1.13, 1.60) | 0.0007 | |

| Vascular dementia | 3 | P = 0.11; I2 = 55% | random-effects model | 1.02(0.85, 1.22) | 0.84 | |

| <10 years | All-cause dementia | 9 | P<0.00001; I2 = 84% | random-effects model | 1.33(1.07, 1.66) | 0.01 |

| Alzheimer’s disease | 10 | P<0.00001; I2 = 92% | random-effects model | 1.31(1.04, 1.65) | 0.02 | |

| Vascular dementia | 5 | P = 0.0006; I2 = 80% | random-effects model | 1.00(0.76, 1.33) | 0.99 | |

| Geographic location | ||||||

| Asia | All-cause dementia | 11 | P = 0.0006; I2 = 88% | random-effects model | 1.29(1.15, 1.45) | <0.0001 |

| Alzheimer’s disease | 11 | P = 0.02; I2 = 54% | random-effects model | 1.48(1.33, 1.65) | <0.00001 | |

| Vascular dementia | 4 | P = 0.16; I2 = 42% | fixed-effects model | 0.96(0.88, 1.05) | 0.34 | |

| Europe | All-cause dementia | 5 | P<0.00001; I2 = 96% | random-effects model | 1.18(0.83, 1.68) | 0.34 |

| Alzheimer’s disease | 6 | P<0.00001; I2 = 96% | random-effects model | 1.17(0.96, 1.41) | 0.12 | |

| Vascular dementia | 3 | P<0.00001; I2 = 98% | random-effects model | 1.09(0.63, 1.88) | 0.76 | |

| North America | All-cause dementia | 3 | P<0.00001; I2 = 98% | random-effects model | 0.94(0.92, 0.96) | <0.00001 |

| Alzheimer’s disease | 5 | P<0.00001; I2 = 97% | random-effects model | 1.28(0.93, 1.78) | 0.13 | |

| Vascular dementia | 2 | P = 0.98; I2 = 0% | fixed-effects model | 1.11(0.99, 1.24) | 0.07 | |

| MCI | ||||||

| POAG | 3 | P = 0.81; I2 = 0% | fixed-effects model | 2.00(1.79, 2.22) | <0.00001 | |

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; NA, not applicable

*P < 0.05 for the Q-test or I2 > 50% indicated significant heterogeneity

Discussion

Main findings

The present study comprehensively investigated the association between glaucoma and the risk of incident dementia or cognitive decline and found that glaucoma was an independent risk factor for all-cause dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, vascular dementia and cognitive impairment. Our result is similar to the findings of a recently published systematic review. Xu et al. [53] quantified the association between glaucoma and cognitive impairment or dementia, proposing a prevalence of 7.7% for glaucoma patients with mild cognitive impairment; 3.9–77.8% for cognitive impairment and 2.5–3.3% for dementia in glaucoma patients.

Several meta-analyses have tried to pool the effects of the associations of glaucoma with dementia or cognitive decline. The meta-analysis by Zhao et al. [54]. included only eleven cohort studies published up to 2020 and revealed that glaucoma was not an independent risk factor for dementia. Similarly, Kuźma et al. [55] performed a meta-analysis of eight cross-sectional studies involving 175,357 individuals up to 2020 and found no association between glaucoma and dementia. On the contrary, our systematic review and meta-analysis is the comprehensive meta-analysis to confirm that glaucoma is linked to dementia, which may contribute to an accurate assessment of whether glaucoma patients are associated with an increased risk of dementia or cognitive impairment.

Notwithstanding these overall associations, there was a high heterogeneity of effects across all the studies and sensitivity analyses did not reduce the heterogeneity. Our subgroup analysis showed that glaucoma type, gender, age, and region (ethnicity) were influential factors in the association between glaucoma and the risk of dementia. In addition, the different confounders adjusted for each study may be another source of heterogeneity. However, there was a nonsignificant association between glaucoma and all-cause dementia in subgroups with follow-up years > 10, age 65and number of cases ≥ 10,000.

Angle-closure glaucoma only increases the occurrence of vascular dementia. Vascular imaging has shown evidence of microvascular dysfunction in both angle-closure glaucoma and dementia [56]. According to Cruz Hernández et al. [57], age-related decreased angiogenesis, lessened vascular vessel diameter, inefficient cell signaling, and impaired vasodilation result in reduced cerebral blood flow. Intermittent cerebral ischemia is linked to vascular dementia, and ischemia can cause oxidative stress, leading to the formation of reactive oxygen species and cellular damage [58]. The accumulation of neurotoxic factors causes cell death in Alzheimer’s disease, and it has been linked to retinal ganglion cell death in glaucoma. PACG patients have microvascular dysfunction and deficiencies in endothelial-dependent and non-endothelial-dependent vasodilatory responses [59, 60]. However, open-angle glaucoma was not associated with vascular dementia, possibly due to open-angle glaucoma being included in fewer observational studies, reducing statistical efficiency. More studies are needed to confirm the association between open-angle glaucoma and dementia.

The results of subgroup analyses revealed gender differences in the prevalence of dementia, with women with a higher risk of Alzheimer’s disease with glaucoma, which is consistent with epidemiological research on dementia. Furthermore, clinical evidence has shown that women have faster age-related neurological decline and more severe cognitive impairment than elderly men [61]. Currently, there are several major biological hypotheses regarding gender differences in Alzheimer’s disease, including age-related decreases in sex hormones (estrogen, progesterone, testosterone), various genetic risks (ApoE, Etc.), effects of risk for other diseases (diabetes, depression, cardiovascular disease), and gender differences in brain anatomy [62, 63]. Estradiol, for example, increases neurogenesis in different brain regions, such as the hippocampal dentate gyrus, and these newly generated neurons in the hippocampus contribute to region-specific learning and memory [64]. Women with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) had hippocampal atrophy, confirming estrogen’s critical role in cognitive function [65]. However, there is no link between brain estrogen levels and the onset of dementia in men [66], which may explain our results that there was no significant association between male glaucoma patients and the risk of dementia.

Age subgroup analysis proved that the coexistence of glaucoma and dementia became more pronounced with age. The risk of dementia was 2.9 times higher in glaucoma patients aged 65 years, and Alzheimer’s disease was 4.09 times higher, presumably due to the increased prevalence of glaucoma and dementia associated with advancing age. Furthermore, we discovered that the risk of glaucoma and all-cause dementia or Alzheimer’s disease differed geographically. In Asia, glaucoma significantly increased the risk of all-cause dementia and Alzheimer’s disease, whereas there was no correlation in Europe or North America. We speculate that it may be related to the large population base, accelerated population aging, and increased level of dementia diagnosis and dementia reporting in Asia, resulting in an overall high prevalence of dementia associated with rapid growth [67].

Strengths and limitations

Our study encompassed data from 27 population-based longitudinal studies, including 9,061,675 participants across 8 countries, with considerable sample size. Compared with previous meta-analyses, we attempted to include all forms of dementia by including all relevant studies, not only subgroup analysis of the type of glaucoma, the subtype of dementia, age, gender, sample size, geographic location, and follow-up time, but also a refined analysis of the association of each influencing factor with the subtype of dementia.

Nevertheless, the study still had a few potential limitations. First, there was considerable heterogeneity among the results of the included studies, lowering the quality of the evidence. Based on our findings, the type of glaucoma and geographic region of the study population may be a source of heterogeneity. Alternatively, different approaches to assessing glaucoma, dementia, and the variables used to characterize cognitive decline may provide other explanations for the discrepancy. Nevertheless, due to the limitations of the original data, more detailed subgroup analyses could not be performed, and the available results did not fully explain the sources of heterogeneity generation. None of the studies recruited participants immediately at the time of glaucoma diagnosis, which may have led to selection bias. Second, some did not fully adjust for confounding factors, such as BMI, smoking, and alcohol consumption, all risk factors for dementia or cognitive impairment. These factors may influence the association between glaucoma and dementia or cognitive impairment. Finally, the study subjects were from different regions, and differences between races may have impacted the results; the included studies were all cohort studies and case-control studies, with a higher risk of various types of bias, such as selection and recall bias.

Despite these limitations, our study has implications for public health, government officials, researchers, and the general public. The global population is growing and advances in health care and social welfare have prolonged life expectancy, meaning that older adults will represent a significant proportion of the population. As a result, age-related diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease will become more prevalent. More high-quality longitudinal studies are needed in the future to assess the association between glaucoma subtypes and dementia risk and to identify sources of heterogeneity in previously published studies. At the same time, the factors influencing the relationship between glaucoma and dementia or cognitive function should be further explored and fully adjusted to identify the underlying biological basis and reveal features of glaucoma that may increase the risk of dementia, and translational studies as well as clinical and population studies are necessary to determine the impact of different treatment strategies and the degree of glaucoma disease on cognitive function, and ultimately to identify targeted preventive interventions.

Conclusions

Overall, our review first demonstrated that glaucoma increased the risk of subsequent cognitive impairment and dementia, including all-cause dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, and vascular dementia, which updated the results of previous meta-analysis. These findings contribute to the further promotion of dementia awareness and glaucoma patients, and serve to develop global management strategies to reduce the occurrence of dementia in glaucoma.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank to all other authors for consulting and sorting out the relevant literature and the support of the above funds.

Author contributions

WX.R. wrote the main manuscript text and C.W.J. prepared Tables 1-3. Z.W.Xand M.M.S reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine -- Chief Scientist of Qi-Huang Project (2022-6); Major Public Welfare Projects in Henan Province [grant numbers 201300310100]; Joint Open Project of the State Administration of Chinese Medicine [grant numbers GZY-KJS-2022-040-1].

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Wenxia Zhao, Email: wwwzp2020@126.com.

Mingsan Miao, Email: miaomingsan@163.com.

References

- 1.Gale SA, Acar D, Daffner KR (2018) Dementia. Am J Med 131:1161–1169. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2018.01.022 10.1016/j.amjmed.2018.01.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Javaid FZ, Brenton J, Guo L et al (2016) Visual and ocular manifestations of Alzheimer’s Disease and their use as biomarkers for diagnosis and progression. Front Neurol 7:55. 10.3389/fneur.2016.00055 10.3389/fneur.2016.00055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rutherford BR, Brewster K, Golub JS et al (2018) Sensation and Psychiatry: linking Age-related hearing loss to late-life Depression and Cognitive decline. Am J Psychiatry 175:215–224. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2017.17040423 10.1176/appi.ajp.2017.17040423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Whitson HE, Cronin-Golomb A, Cruickshanks KJ et al (2018) American Geriatrics Society and National Institute on Aging Bench-to-Bedside Conference: Sensory Impairment and Cognitive Decline in Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 66: 2052–2058. 10.1111/jgs.15506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Jonas JB, Aung T, Bourne RR et al (2017) Glaucoma. Lancet 390:2183–2193. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31469-1 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31469-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weinreb RN, Aung T, Medeiros FA (2014) The pathophysiology and treatment of glaucoma: a review. JAMA 311:1901–1911. 10.1001/jama.2014.3192 10.1001/jama.2014.3192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nucci C, Martucci A, Cesareo M et al (2013) Brain involvement in glaucoma: advanced neuroimaging for understanding and monitoring a new target for therapy. Curr Opin Pharmacol 13:128–133. 10.1016/j.coph.2012.08.004 10.1016/j.coph.2012.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang EE, Goldberg JL (2012) Glaucoma 2.0: neuroprotection, neuroregeneration, neuroenhancement. Ophthalmology 119: 979–986. 10.1016/j.ophtha. 2011. 11.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Almasieh M, Wilson AM, Morquette B et al (2012) The molecular basis of retinal ganglion cell death in glaucoma. Prog Retin Eye Res 31:152–181. 10.1016/j.preteyeres2011.11.002 10.1016/j.preteyeres [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grieshaber MC, Orgul S, Schoetzau A et al (2007) Relationship between retinalglial cell activation in glaucoma and vascular dysregulation. J Glaucoma 16:215–219. 10.1097/IJG.0b013e31802d045a 10.1097/IJG.0b013e31802d045a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ban N, Siegfried CJ, Apte RS (2018) Monitoring neurodegeneration in Glaucoma: therapeutic implications. Trends Mol Med 24:7–17. 10.1016/j.molmed2017.11.004 10.1016/j.molmed [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fukuoka H, Nagaya M, Toba K (2015) The occurrence of visual and cognitive impairment, and eye diseases in the super-elderly in Japan: a cross-sectional single-center study. BMC Res Notes 8:619. 10.1186/s13104-015-1625-7 10.1186/s13104-015-1625-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maurano STP, da Silva DJ, Ávila MP et al (2018) Cognitive evaluation of patients with glaucoma and its comparison with individuals with Alzheimer’s disease. Int Ophthalmol 38:1839–1844. 10.1007/s10792-017-0658-4 10.1007/s10792-017-0658-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McCoskey M, Addis V, Goodyear K et al (2018) Association between Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma and cognitive impairment as measured by the Montreal Cognitive Assessment. Neurodegener Dis 18:315–322. 10.1159/000496233 10.1159/000496233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vidal KS, Suemoto CK, Moreno AB et al (2020) Association between cognitive performance and self-reported glaucoma in middle-aged and older adults: a cross-sectional analysis of ELSA-Brasil. Braz J Med Biol Res 53:e10347. 10.1590/1414-431X202010347 10.1590/1414-431X202010347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mandas A, Mereu RM, Catte O et al (2014) Cognitive impairment and age-related Vision disorders: their possible relationship and the evaluation of the use of aspirin and statins in a 65 years-and-over Sardinian Population. Front Aging Neurosci 6:309. 10.3389/fnagi.2014.00309 10.3389/fnagi.2014.00309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ohno-Matsui K (2011) Parallel findings in age-related macular degeneration and Alzheimer’s disease. Prog Retin Eye Res 30. 10.1016/j.preteyeres2011.02.004 217 – 38 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Ramirez AI, de Hoz R, Salobrar-Garcia E et al (2017) The role of Microglia in Retinal Neurodegeneration: Alzheimer’s Disease, Parkinson, and Glaucoma. Front Aging Neurosci 9:214. 10.3389/fnagi.2017.00214 10.3389/fnagi.2017.00214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bach-Holm D, Kessing SV, Mogensen U et al (2012) Normal tension glaucoma and Alzheimer disease: comorbidity? Acta Ophthalmol. 90:683–685. 10.1111/j.1755-3768.2011.02125.x [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Ong SY, Cheung CY, Li X et al (2012) Visual impairment, age-related eye diseases, and cognitive function: the Singapore malay Eye study. Arch Ophthalmol 130:895–900. 10.1001/archophthalmol.2012.152 10.1001/archophthalmol.2012.152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wostyn P, De Groot V, Van Dam D et al (2017) Alzheimer’s disease and glaucoma: can glymphatic system dysfunction underlie their comorbidity? Acta Ophthalmol 95:e244–e245. 10.1111/aos.13068 10.1111/aos.13068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sen S, Saxena R, Tripathi M et al (2020) Neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease and glaucoma: overlaps and missing links. Eye (Lond) 34:1546–1553. 10.1038/s41433-020-0836-x 10.1038/s41433-020-0836-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rethlefsen ML, Kirtley S, Waffenschmidt S et al (2021) PRISMA-S: an extension to the PRISMA Statement for reporting literature searches in systematic reviews. Syst Rev 10:39. 10.5195/jmla.2021.962 10.5195/jmla.2021.962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stang A (2010) Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol 25:603–605. 10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z 10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ et al (2003) Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 327:557–600. 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Crump C, Sundquist J, Sieh W et al (2024) Risk of Alzheimer’s Disease and related dementias in persons with Glaucoma: a National Cohort Study. Ophthalmology 131:302–309. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2023.10.014 10.1016/j.ophtha.2023.10.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim DK, Lee SY (2023) Could mid-to late-onset Glaucoma be Associated with an increased risk of Incident Dementia? A Nationwide Retrospective Cohort Study. J Pers Med 13:214. 10.3390/jpm13020214 10.3390/jpm13020214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Park DY, Kim M, Bae Y et al (2023) Risk of dementia in newly diagnosed glaucoma: a nationwide cohort study in Korea. Ophthalmology 130:684–691. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2023.02.017 10.1016/j.ophtha.2023.02.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shang X, Zhu Z, Huang Y et al (2023) Associations of ophthalmic and systemic conditions with incident dementia in the UK Biobank. Br J Ophthalmol 107:275–282. 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2021-319508 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2021-319508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ekström C, Puhto I, Kilander L (2021) Association between open-angle glaucoma and Alzheimer’s disease in Sweden: a long-term population-based follow-up study. Ups J Med Sci 21:126. 10.48101/ujms.v126.7819 10.48101/ujms.v126.7819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Belamkar AV, Mansukhani SA, Savica R et al (2021) Incidence of dementia in patients with Open-angle Glaucoma: a Population-based study. J Glaucoma 30:227–234. 10.1097/IJG.0000000000001774 10.1097/IJG.0000000000001774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hwang PH, Longstreth WT Jr, Thielke SM et al (2021) Ophthalmic conditions associated with dementia risk: the Cardiovascular Health Study. Alzheimers Dement 17:1442–1451. 10.1002/alz.12313 10.1002/alz.12313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Su CW, Lin CC, Kao CH et al (2016) Association between Glaucoma and the risk of Dementia. Med (Baltim) 95:e2833. 10.1097/MD0000000000002833 10.1097/MD.0000000000002833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen YY, Lai YJ, Yen YF et al (2018) Association between normal tension glaucoma and the risk of Alzheimer’s disease: a nationwide population-based cohort study in Taiwan. BMJ Open 8:e22987. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-022987 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-022987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moon JY, Kim HJ, Park YH et al (2018) Association between Open-Angle Glaucoma and the risks of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases in South Korea: a 10-year Nationwide Cohort Study. Sci Rep 8:11161. 10.1038/s41598-018-29557-6 10.1038/s41598-018-29557-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xiao Z, Wu W, Zhao Q et al (2020) Association of Glaucoma and cataract with Incident Dementia: a 5-Year Follow-Up in the Shanghai Aging Study. J Alzheimers Dis 76:529–537. 10.3233/JAD-200295 10.3233/JAD-200295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Keenan TD, Goldacre R, Goldacre MJ (2015) Associations between primary open angle glaucoma, Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia: record linkage study. Br J Ophthalmol 99:524–527. 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2014-305863 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2014-305863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee CS, Larson EB, Gibbons LE et al (2019) Associations between recent and established ophthalmic conditions and risk of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 15:34–41. 10.1016/j.jalz.2018.06.2856 10.1016/j.jalz.2018.06.2856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ou Y, Grossman DS, Lee PP et al (2021) Glaucoma, Alzheimer disease and other dementia: a longitudinal analysis. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 19:285–292. 10.3109/09286586.2011.649228 10.3109/09286586.2011.649228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lin IC, Wang YH, Wang TJ et al (2016) Glaucoma, Alzheimer’s disease, and Parkinson’s disease: an 8-year population-based follow-up study. PLoS ONE 11:e0150789. 10.1371/journal.pone.0108938 10.1371/journal.pone.0150789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kuo FH, Chung JF, Hsu MY et al (2020) Impact of the severities of Glaucoma on the incidence of subsequent dementia: a Population-based Cohort Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17:2426. 10.3390/ijerph17072426 10.3390/ijerph17072426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Helmer C, Malet F, Rougier MB et al (2013) Is there a link between open-angle glaucoma and dementia? The three-city-alienor cohort. Ann Neurol 74:171–179. 10.1002/ana.23926 10.1002/ana.23926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kessing LV, Lopez AG, Andersen PK et al (2007) No increased risk of developing Alzheimer disease in patients with glaucoma. J Glaucoma 16:47–51. 10.1097/IJG.0b013e31802b3527 10.1097/IJG.0b013e31802b3527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ekström C, Kilander L (2016) Open-angle glaucoma and Alzheimer’s disease: a population- based 30-year follow-up study. Acta Ophthalmol 95:e157–e158. 10.1111/aos.13243 10.1111/aos.13243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ekström C, Kilander L (2014) Pseudoexfoliation and Alzheimer’s disease: a population- based 30-year follow-up study. Acta Ophthalmol 92:355–358. 10.1111/aos.12184 10.1111/aos.12184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Umunakwe O, Gupta D, Tseng H (2020) Association of Open-Angle Glaucoma with Non-alzheimer’s dementia and cognitive impairment. Ophthalmol Glaucoma 3:460–465. 10.1016/j.ogla.2020.06.008 10.1016/j.ogla.2020.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chamard C, Alonso S, Carrière I et al (2024) Dementia and glaucoma: results from a Nationwide French Study between 2006 and 2018. Acta Ophthalmol. 21. 10.1111/aos.16624 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48.Chung SD, Ho JD, Chen CH et al (2015) Dementia is associated with open-angle glaucoma: a population-based study. Eye (Lond) 29: 1340–1346. 10.1038/eye. 2015. 120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.Lai SW, Lin CL, Liao KF (2017) Glaucoma may be a non-memory manifestation of Alzheimer’s disease in older people. Int Psychogeriatr 29:1–7. 10.1017/S1041610217000801 10.1017/S1041610217000801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wändell PE, Ljunggren G, Wahlström L et al (2022) Psychiatric diseases and dementia and their association with open-angle glaucoma in the total population of Stockholm. Ann Med 54:3349–3356. 10.1080/07853890.2022.2148735 10.1080/07853890.2022.2148735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang L, Song M, Zhao X et al (2021) Functional deficit of sense organs as a risk factor for cognitive functional disorder in Chinese community elderly people. Int J Clin Pract 75:e14905. 10.1111/ijcp.14905 10.1111/ijcp.14905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mullany S, Xiao L, Qassim A et al (2022) Normal-tension glaucoma is associated with cognitive impairment. Br J Ophthalmol 106:952–956. 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2020-317461 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2020-317461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Xu Y, Phu J, Aung HL, Hesam-Shariati N et al (2023) Frequency of coexistent eye diseases and cognitive impairment or dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eye (Lond) 37:3128–3136. 10.1038/s41433-023-02481-4 10.1038/s41433-023-02481-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhao W, Lv X, Wu G et al (2021) Glaucoma is not Associated with Alzheimer’s Disease or Dementia: a Meta-analysis of Cohort studies. Front Med (Lausanne) 8:688551. 10.3389/fmed.2021.688551 10.3389/fmed.2021.688551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kuźma E, Littlejohns TJ, Khawaja AP et al (2021) Visual impairment, Eye diseases, and dementia risk: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. J Alzheimers Dis 83:1073–1087. 10.3233/JAD-210250 10.3233/JAD-210250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mroczkowska S, Shokr H, Benavente-Pérez A et al (2022) Retinal microvascular dysfunction occurs early and similarly in mild Alzheimer’s Disease and Primary-Open Angle Glaucoma patients. J Clin Med Nov 11:6702. 10.3390/jcm11226702 10.3390/jcm11226702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cruz Hernández JC, Bracko O, Kersbergen CJ et al (2019) Neutrophil adhesion in brain capillaries reduces cortical blood flow and impairs memory function in Alzheimer’s disease mouse models. Nat Neurosci 22:413–420. 10.1038/s41593-018-0329-4 10.1038/s41593-018-0329-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jain S, Aref AA (2015) Senile dementia and Glaucoma: evidence for a common link. J Ophthalmic Vis Res 10:178–183. 10.4103/2008-322X.163766 10.4103/2008-322X.163766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mudassar Imran Bukhari S, Yew KK, Thambiraja R et al (2019) Microvascular endothelial function and primary open angle glaucoma. Ther Adv Ophthalmol 11:2515841419868100. 10.1177/2515841419868100 10.1177/2515841419868100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zabel P, Kaluzny JJ, Wilkosc-Debczynska M et al (2019) Comparison of retinal microvasculature in patients with Alzheimer’s Disease and Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma by Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 60:3447–3455. 10.1167/iovs.19-27028 10.1167/iovs.19-27028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Proust-Lima C, Amieva H, Letenneur L et al (2008) Gender and education impact on brain aging: a general cognitive factor approach. Psychol Aging 23:608–620. 10.1037/a0012838 10.1037/a0012838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Carter CL, Resnick EM, Mallampalli M et al (2012) Sex and gender differences in Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations for future research. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 21:1018–1023. 10.1089/jwh.2012.3789 10.1089/jwh.2012.3789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cui J, Shen Y, Li R (2013) Estrogen synthesis and signaling pathways during aging: from periphery to brain. Trends Mol Med 19:197–209. 10.1016/j.molmed.2012.12.007 10.1016/j.molmed.2012.12.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mahmoud R, Wainwright SR, Galea LA (2016) Sex hormones and adult hippocampal neurogenesis: regulation, implications, and potential mechanisms. Front Neuroendocrinol 41:129–152. 10.1016/j.yfrne.2016.03.002 10.1016/j.yfrne.2016.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fleisher A, Grundman M, Jack CR Jr et al (2005) Sex, apolipoprotein E epsilon 4 status, and hippocampal volume in mild cognitive impairment. Arch Neurol 62:953–957. 10.1001/archneur.62.6.953 10.1001/archneur.62.6.953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Vest RS, Pike CJ (2013) Gender, sex steroid hormones, and Alzheimer’s disease. Horm Behav 63:301–307. 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2012.04.006 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2012.04.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Venketasubramanian N, Sahadevan S, Kua EH et al (2010) Interethnic differences in dementia epidemiology: global and Asia-Pacific perspectives. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 30:492–498. 10.1159/000321675 10.1159/000321675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.