Abstract

Content of bioactive constituents is one of the most important characteristics in Rheum palmatum complex. Increasing ingredient content through genetic breeding is an effective strategy to solve the contradiction between large market demand and resource depletion, but currently hampered by limited understanding of metabolite biosynthesis in rhubarb. In this study, deep transcriptome sequencing was performed to compare roots, stems, and leaves of two Rheum species (PL and ZK) that show different levels of anthraquinone contents. Approximately 0.52 billion clean reads were assembled into 58,782 unigenes, of which around 80% (46,550) were found to be functionally annotated in public databases. Expression patterns of differential unigenes between PL and ZK were thoroughly investigated in different tissues. This led to the identification of various differentially expressed genes (DEGs) involved in shikimate, MEP, MVA, and polyketide pathways, as well as those involved in catechin and gallic acid biosynthesis. Some structural enzyme genes were shown to be significantly up-regulated in roots of ZK with high anthraquinone content, implying potential central roles in anthraquinone synthesis. Taken together, our study provides insights for future functional studies to unravel the mechanisms underlying metabolite biosynthesis in rhubarb.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12298-024-01492-z.

Keywords: Anthraquinones biosynthesis, Differential gene expression, Quality difference, Rheum palmatum complex, RNA-seq

Introduction

Rhubarb (Da Huang) is one of the most famous traditional Chinese herbal medicines. Its source plants belong to genus Rheum within Polygonaceae, including R. palmatum L., R. tanguticum (Maxim. ex Regel) Maxim. ex Balf., and R. officinale Baill. The dried roots and rhizomes of these plants have effects of clearing body heat, detoxifying toxins, expelling blood stasis, removing dampness and abating jaundice, and have been widely used to treat various diseases for thousands of years (Lai et al. 2015; Chinese Pharmacopoeia Committee 2020). In recent years, the number of medicines with rhubarb as the main raw material has been increasing, as well as the related traditional Chinese medicine formula particles. However, current production of rhubarb faces multiple problems, such as wild resource depletion, long planting cycle, seed quality degradation, etc. (Li et al. 2014). This status has seriously affected the clinical use of rhubarb. As such, it is urgent to accelerate the breeding process of Rheum plants and carry out genetic breeding of excellent quality traits.

Anthraquinones are regarded as the major bioactive components in rhubarb, comprising aloe-emodin, chrysophanol, emodin, physcion, and rhein (Pandith and Khan 2022; Wu et al. 2014). The other popular active constituents in rhubarb are tannins, encompassing catechin, gallic acid, and their derivatives (Wang et al. 2011, 2017). The biosynthesis of anthraquinones in higher plants mainly consists of two metabolic pathways, polyketide pathway and a combination of shikimate and mevalonate/methyl-D-erythritol 4-phosphate pathways (Kang et al. 2020). After the formation of anthraquinone skeleton, it undergoes the modification process mediated by Cyt P450s (CYPs) and UDP-glycosyltransferases (UGTs), and finally results in the synthesis of anthraquinones (Rama Reddy et al. 2015). Catechins and gallic acids in plants are basically derived from shikimate, phenylpropanoid, and flavonoid biosynthesis pathways (Lu et al. 2018). At present, domestic and foreign scholars mainly focus on chemical constituents and pharmacodynamic effects (Sun et al. 2016; Xian et al. 2017), as well as the genetic variation of rhubarb populations (Wang et al. 2018). However, there is limited research on the molecular level of rhubarb, especially the characterization of metabolite synthesis using functional genomics.

Transcriptome sequencing (RNA-seq) of medicinal plants is a powerful tool to analyze functional genes and regulatory mechanisms underlying the biosynthesis pathways of secondary metabolites (Guo et al. 2021). It can monitor the overall transcriptional activity and provide insights into differentially expressed genes (Jia et al. 2015). Transcriptomics-assisted dissection has been widely applied in various medicinal plants to pinpoint candidate genes related to medicinal components, such as terpenoid, alkaloid, stilbene, anthraquinone, and flavonoid (Liu et al. 2023, 2022; Wang et al. 2021). Mala and his colleagues identified multiple genes associated with secondary metabolism in Rheum australe in response to cold stress using comparative transcriptome analysis (Mala et al. 2021). Similar work by Liu et al. (2020), who investigated the transcriptional dynamics of two Rheum species, pointed out 17 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) involved in the biosynthesis of anthraquinones and flavonoids. However, these studies using only single tissue for transcriptome sequencing, cannot often provide a full picture of genes related to metabolite synthesis in different tissues, due to the spatial limitations of transcriptome (Guo et al. 2021). As such, recent studies turned to focus on tissue-specific expression profiles of R. officinale and R. tanguticum, in order to investigate the transcript differences of secondary metabolites in diverse tissues (Hu et al. 2022; Zhou et al. 2022, 2021). Despite these achievements, our understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying the differences in bioactive constituents in different Rheum plants is still far from complete.

Our previous studies on the evolutionary relationships of three rhubarb source plants revealed that they formed the R. palmatum species complex (Wang et al. 2018). Two Rheum species showing contrasting levels of anthraquinones—one growing in genuine producing area (ZK), the other non-genuine producing area (PL), were compared with each other in this study. Comparative transcriptome analyses were performed in different tissues of PL and ZK. Transcriptional dynamics such as the variations in GO and KEGG enrichments were thoroughly clarified. Candidate genes potentially responsible for the differences in the biosynthesis of anthraquinones, gallic acids, and catechins were pointed out. This study enhances our understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying metabolite synthesis and lays a valid foundation for future functional studies of rhubarb.

Materials and methods

Plant materials

Rheum materials (PL and ZK) were collected in Pingli County, Shaanxi Province, China (32°01′N, 109°21′E) and Zeku County, Qinghai Province, China (35°15′N, 101°53′E), respectively. In order to ensure the similar growth states of two Rheum plant materials, the typical flowering stage was chosen for sampling. Roots, stems, and leaves were sampled from the same individual and the tissue sampling was conducted with three biological repetitions. This finally resulted in a total of 18 samples. All harvested samples were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80 ℃ for future use.

Determination of anthraquinone components

Roots, stems, and leaves of PL and ZK were ground at 30 Hz for 1.5 min using a mixer mill (MM 400) with a zirconia head. The whole protocols for anthraquinone extraction and determination used in this study are referred to Zhou et al. (2021) and Zhu et al. (2021). Basically, 500 mg powder of each sample was mixed with 25 mL absolute methanol solvent (v/v) in a conical flask and subsequently placed in boiling water bath for 60 min. After cooling to room temperature, the lost mass was made up with methanol followed by sufficient mixing, and the filtrate was used for the final determination of anthraquinone content. Experiment was performed with three biological repetitions to ensure data reproducibility.

HPLC analysis was conducted on Agilent 1100 system. Sepax RP-C18 column (Amethyst C18-H, 250 mm × 4.6 mm, 5 μm) was used for chromatographic analysis (detection wavelength: 254 nm; injection volume: 10 μL; flow rate: 1 mL/min; column temperature: 30 ℃). The aqueous mobile phase was 15% methanol and 85% of 0.1% phosphoric acid in water. The standard graphs of aloe-emodin, rhein, emodin, chrysophanol, and physcion (mg/g) were used as references to determine the content of five free anthraquinone components. Student’s t-test was used to detect difference of five free anthraquinones in three different tissues between PL and ZK.

RNA isolation, cDNA library construction and sequencing

Total RNA was isolated using a RNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Concentration of each RNA sample was measured with a NanoDrop 2000c spectrophotometer. Library preparation and construction was performed following the description of Yang et al. (2018) and then sequenced on Illumina X Ten platform at Biomarker Technology Company (Beijing, China).

De novo assembly and comparative transcriptome analysis

Adapter sequence, ambiguous sequences, and low-quality reads were firstly filtered from raw reads using Trimmomatic v0.35 (Bolger et al. 2014). Clean reads were subjected to De novo assembly using Trinity v2.5.1 with default parameters (Grabherr et al. 2011). The assembled transcripts were further processed with CD-HIT v4.6 to remove redundancy using a sequence identity threshold of 0.95 (Fu et al. 2012), and the remaining unigenes were used for subsequent analyses. Clean reads of each sample were mapped to total non-redundant unigenes using Bowtie v2.4.4 (Langmead and Salzberg 2012). Gene expression levels were quantified by RSEM v1.3.1 as Fragments per Kilobase of transcript per Million mapped reads (FPKM) (Li and Dewey 2011). DESeq2 implemented in R was used to calculate expression differences, and genes meeting the thresholds of |log2(FoldChange)|> 1 and FDR < 0.05 were considered as DEGs (Love et al. 2014). Expression levels of DEGs were normalized by log-transformation, and finally visualized in a heatmap plot using Pheatmap package (https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/pheatmap/).

Functional annotation and enrichment analysis

Functional annotation of DEGs was performed by similarity search against public databases, including NCBI non-redundant (Nr), Swiss-Prot, Cluster of Orthologous Group (COG), euKaryotic Ortholog Group (KOG), and Translation of EMBL (TrEMBL) using BLASTX with an e-value cutoff of 10−5 (Altschul et al. 1997). GO enrichment and KEGG pathway analyses were conducted by clusterProfiler v3.14.0 (Yu et al. 2012), and the terms with a P-value < 0.05 were designated as significantly enriched.

Co-expression network analysis

Weighted gene co-expression network analysis was performed using WGCNA package in R (Langfelder and Horvath 2008). Unigenes were filtered with the total expression threshold of 10. Sample clustering was implemented to exclude outliers. A weighted scale-free network was constructed using a soft threshold power of 6 with R2 value > 0.85. Correlation relationships between different modules and traits were calculated to point out the highly correlated module. Gephi software was employed to visualize the selected module (Bastian et al. 2009), and the expression levels of unigenes were displayed in a heatmap plot.

Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) validation

Synthesis of cDNA from PL and ZK was conducted using a RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Thermo Fisher, Beijing, China). R. palmatum actin gene (c55882.graph_c0) was used as an internal reference to normalize gene expression levels using 2−△△Ct method (Livak and Schmittgen 2001). All qRT-PCR reactions were performed on a CFX Connect Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad, USA) using NovoStart® SYBR qPCR SuperMix Plus (Novoprotein, Shanghai, China). Relative expression levels are represented by average values ± standard deviation (SD) of three biological repetitions. Gene-specific primers were designed by web tool Primer3Plus and shown in Table S1.

Results

Two Rheum species show contrasting contents of anthraquinones

To evaluate the quality difference of PL and ZK, five free anthraquinones, including aloe-emodin, chrysophanol, emodin, physcion, and rhein, were determined in roots, stems, and leaves, respectively. As shown in Fig. 1, roots of PL and ZK exhibited largest difference in the content of free anthraquinones, of which each component was much more abundant in ZK, a Rheum species growing in genuine producing area. In contrast, a comparable pattern of anthraquinone content was observed in leaf tissue of PL and ZK, except for emodin and rhein displaying a slightly higher level in species PL from non-genuine producing area. We speculate that this may be caused by inaccurate measurements or insufficient replicates during experiments. As for tissue stems, the contents of chrysophanol and emodin in ZK were significantly higher than those in PL, while it was exactly vice-versa for aloe-emodin and physcion. In the level of different tissues, roots were undoubtedly found to contain the highest content of each free anthraquinone in both Rheum materials, except for emodin in PL, whereas the least anthraquinone content was mainly observed in stems (Fig. 1). This result is consistent with the distribution of anthraquinones in Rheum species reported in our previous study (Zhou et al. 2021).

Fig. 1.

Contents of five free anthraquinones in different tissues between PL and ZK. Asterisks represent significant difference according to Student’s t-test (***, P < 0.001; *, P < 0.05; NS, no significance)

Comparative transcriptome analyses of two Rheum species

To investigate transcriptional dynamics of Rheum complex, RNA-seq analysis was carried out on roots, stems, and leaves of PL and ZK, respectively. Each tissue encompassed three biological repetitions, leading to 18 libraries (Table S2). A total of 0.52 billion clean reads was obtained after filtering, with each library containing about 29 million reads. Based on data quality assessment, the 18 generated libraries were of high quality, with the Q30 value higher than 93% per sample. Besides, GC content of each sample was found to range from 48.61 to 50.72%. Detailed information on sequencing data is shown in Table S2. Clean reads were subsequently subjected to de novo assembly, resulting into a total of 338,135 and 257,942 unigenes in PL and ZK samples, with N50 lengths of 610 bp and 834 bp, respectively (Table 1). When performing re-assembly based on mixed reads of PL and ZK, the number of unigenes reduced to 58,782, and the N50 length increased considerably by 3–4 times to 2,613. More than 61% of these genes were longer than 1000 bp, while no gene shorter than 300 bp was detected (Table 1).

Table 1.

Overview of assembled transcripts and unigenes from R. palmatum complex

| Unigene length (bp) | PL | ZK | All |

|---|---|---|---|

| 200–300 | 176,962 (52.33%) | 126,959 (49.22%) | 0 (0%) |

| 300–500 | 85,523 (25.29%) | 65,125 (25.25%) | 9,483 (16.13%) |

| 500–1000 | 44,852 (13.26%) | 35,556 (13.78%) | 13,250 (22.54%) |

| 1000–2000 | 18,667 (5.52%) | 16,568 (6.42%) | 15,801 (26.88%) |

| 2000 + | 12,131 (3.59%) | 13,734 (5.32%) | 20,248 (34.45%) |

| Total number | 338,135 | 257,942 | 58,782 |

| Total length | 170,348,485 | 148,033,415 | 104,701,981 |

| N50 length | 610 | 834 | 2,613 |

| Mean length | 504 | 574 | 1,781 |

PL, Pingli, Shaanxi; ZK, Zeku, Qinghai

To obtain a comprehensive overview of transcriptome data, a principal component analysis (PCA), aiming to de-noise and reduce dimensionality, was carried out based on gene read counts of RNA-seq datasets (Fig. S1a). Three replicates per sample were basically clustered together in PC1/2, except that one replicate of each root sample was a bit far away from the other two replicates. Correlation analysis revealed that, except for replicate 02 of root tissue, the correlation coefficients between different replicates per sample were moderate (Fig. S1b). Similarly, the distribution of gene expression levels displayed a comparable tendency across diverse replicates, except replicate 02 of roots (Fig. S1c). This observation is expectable and reasonable, given the complexity of the environment in which Rheum plants grow under wild conditions. As such, we excluded replicate 02 of root tissue and employed the other 16 samples for subsequent analysis.

Identified unigenes were functionally annotated by performing similarity search against eight public databases, including COG, GO, KEGG, KOG, Pfam, Swiss-Prot, eggNOG, and Nr. Approximately 80% (46,550) of the unigenes were found to have at least one blast hit in these databases (Table 2, Table S3). The majority of these annotated unigenes (71.2%) were greater than 1000 bp in length, while less than 30% had a gene length between 300 and 1000. Furthermore, Nr annotation result showed that the species with the top three highest homology to R. palmatum complex were Beta vulgaris (3628, 8.25%), Chenopodium quinoa (3530, 8.03%), and Vitis vinifera (2303, 5.24%) (Fig. S2).

Table 2.

Functional annotation of assembled unigenes

| Database | Num | 300 ≤ length < 1000 | Length ≥ 1000 |

|---|---|---|---|

| COG | 17,528 | 3917 | 13,611 |

| GO | 27,454 | 7953 | 19,501 |

| KEGG | 19,860 | 5621 | 14,239 |

| KOG | 29,366 | 7567 | 21,799 |

| Pfam | 36,392 | 8671 | 27,721 |

| Swiss-Prot | 31,308 | 7607 | 23,701 |

| eggNOG | 44,149 | 11,911 | 32,238 |

| Nr | 44,036 | 12,351 | 31,685 |

| All | 46,550 | 13,396 | 33,154 |

Transcriptional dynamics of R. palmatum complex in different tissues

To explore the expression variation in PL and ZK with different contents of anthraquinones, we compared RNA-seq data of ZK with that of PL in the same tissue. This resulted in the comparison of three data pairs (PL_R vs. ZK_R, PL_S vs. ZK_S, and PL_L vs. ZK_L). DEGs were designated as genes differentially expressed in at least one comparison dataset. As such, 18,078 DEGs were identified in total (Table S4). The numbers of up-regulated/down-regulated DEGs were 3,919/3,162 in roots, 6,027/6,694 in stems, and 6,201/5,362 in leaves, respectively (Fig. 2a). Interestingly, more DEGs were up-regulated than down-regulated in ZK Rheum species at roots and leaves with higher anthraquinone content, whereas stems with least level of anthraquinones were found to have more down-regulated DEGs than up-regulated DEGs. This implies the gene expression levels are in line with the internal biological regulation in organisms. Spatial analysis of DEGs across different tissues revealed a strong overlap, in which around 70% of the DEGs per sample overlapped with the other one or two samples. A total of 3,984 (22.05%) DEGs were found to be commonly present in all comparison pairs (Fig. 2b). Further, DEGs grouped according to their fold changes (FC) showed an uneven distribution pattern among different samples, especially for stems and leaves, which had much more DEGs with absolute FC values higher than 16 (Fig. 2c).

Fig. 2.

Comparative analysis of DEGs between PL and ZK in three different tissues. a Numbers of up-regulated and down-regulated DEGs in roots, stems, and leaves. b Venn diagram representing numbers of DEGs specifically or commonly expressed in roots, stems, and leaves. c Fold change distribution of DEGs in roots, stems, and leaves

Functional enrichment of differentially expressed genes

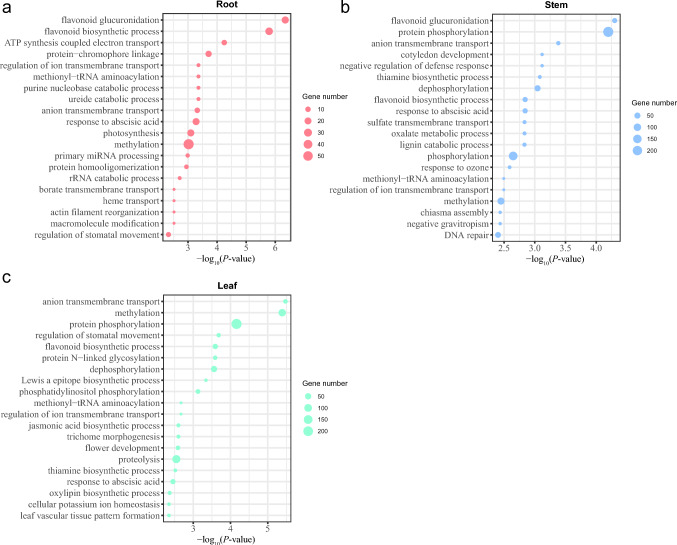

To functionally annotate the identified DEGs, the corresponding annotation information of unigenes were extracted using an in-house perl script (Table S4). These DEGs were further subjected to functional enrichment analysis using R package clusterProfiler (Yu et al. 2012). This resulted in the significant enrichment of 235, 191, and 351 GO terms over three functional categories in roots, stems, and leaves, respectively (Table S5). The majority of these GO terms were associated with biological process, such as methylation (GO:0032259), phosphorylation (GO:0016310, GO:0006468), DNA-templated transcription (GO:0006351), and proteolysis (GO:0006508). Remarkably, GO terms related to flavonoid synthesis (GO:0009813), methylation (GO:0032259), and anion transmembrane transport (GO:0098656) were commonly present in all samples, implying an important role in the biological activities of Rheum plants (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Bubble graphs showing the distribution of top 20 enriched GO terms (biological processes) of DEGs identified in roots (a), stems (b), and leaves (c). The horizontal and vertical axes of bubble graphs represent − log10(P-value) and GO terms, respectively. The bubble size indicates the number of enriched DEGs per term

KEGG enrichment analysis was also performed to investigate pathways involved in these identified DEGs. In total, 22, 22, and 29 pathways were found to be significantly enriched in roots, stems, and leaves, respectively (Table S6, Fig. S3). Multiple pathways were commonly detected in all three tissues, such as hormone signal transduction, plant-pathogen interaction, base excision repair, circadian rhythmof plants, thiamine metabolism, biosynthesis of amino acids, pantothenate and CoA, C5-Branched dibasic acid metabolism. Pathways specifically enriched in roots were involved in ribosome biogenesis and ubiquitin mediated proteolysis. Pathways unique to stems were mainly related to metabolism, including carbon metabolism, starch and sucrose metabolism, amino sugar and nucleotide sugar metabolism. As for leaves, a multitude of pathways associated with fatty acids were uniquely enriched (Table S6, Fig. S3).

Co-expression network analysis identifies hub genes related to the synthesis of bioactive constituents

To identify potential hub genes associated with the synthesis of bioactive constituents, we performed a weighted gene co-expression network analysis using expression levels of filtered DEGs. A weighted scale-free network was constructed based on a soft threshold power of 6 with R2 value > 0.85, resulting into a total of 33 color-coded modules (Fig. S4a). Correlation analysis between different modules and traits showed that the lightgreen module is highly correlated with anthraquinone accumulation (ZK_R, r = 0.75, P = 9e-04, Fig. S4b). Besides, we also found that the unigenes within this module were not only related to their corresponding module, but also to their relevant trait (Fig. S4c). These results highlighted the importance of delving deep into the genes within the lightgreen module. A total of 130 unigenes were found to be differentially expressed in at least one of the three tissues, of which 15/34, 51/36 and 15/38 were down-regulated/up-regulated in roots, stems, and leaves, respectively (Fig. S4d, Table S7). Network visualization displayed strongly interconnected features of gene co-expression, pinpointing several metabolite-related hub genes—including several carbohydrate transport and metabolism proteins (Unigene_493822, 316566, 301570, 490007, 033269, 046425, 017462), the signal transduction proteins phosphatase 2C (Unigene_049727), PEPKR2 (Unigene_015432) and SERK2 (Unigene_022351), and the metabolite biosynthesis protein multicopper oxidase (Unigene_001977) (Fig. 4, Table S7).

Fig. 4.

Weighted gene co-expression network of the lightgreen module. Red and green nodes represent DEGs and non-DEGs, respectively. Red tagged nodes indicate DEGs in root tissue

Pathways related to the synthesis of bioactive constituents in R. palmatum complex

For a next step, we zoomed into the unigenes related to bioactive constituent synthesis. This led to the identification of multiple biological pathways, of which two are represented below.

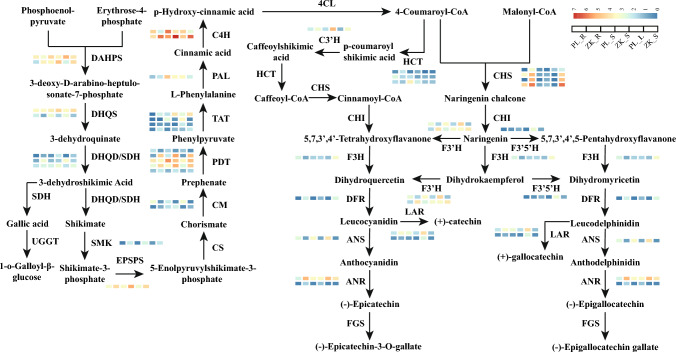

The biosynthesis of anthraquinones

A large proportion of structural enzyme unigenes was found to be differentially expressed in anthraquinone biosynthesis (Fig. 5, Table S8). Most upstream genes prior to isochorismate synthesis had high levels of expression in ZK, except one copy of DAHPS and DHQS. Strangely, several copies of MenE and MenB downstream of shikimate pathway were shown to be suppressed in expression at different tissues of ZK (Fig. 5). Only four genes involved in the start of MEP pathway were identified to exhibit variable expression patterns in one or more tissues, including three up-regulated DXS copies and one down-regulated DXR copy. In contrast, a multitude of DEGs were found in MVA pathway, covering each step up to the formation of dimethylally diphosphate. Most genes encoding HMGS and HMGR displayed lower transcript levels in stems of ZK, while no obvious difference was observed in roots. Similar to MenE and MenB, one copy of MVD and two copies of IPPS working at the end of MVA pathway were also down-regulated in most tissues. However, just three members of the PKS III family involved in secondary metabolite biosynthesis and environmental stress adaptation were detected with increased expression levels in partial tissues of ZK (Fig. 5, Table S8).

Fig. 5.

Representation of anthraquinone biosynthetic pathway in R. palmatum complex. Expression profiles of DEGs involved in anthraquinone biosynthesis are shown in heatmap plots. Color-coded blocks represent the variations of log10(FPKM+1). DAHPS, 3-Deoxy-7-phosphoheptulonate synthase; DHQS, 3-Dehydroquinate synthase; DHQD/SDH, 3-Dehydroquinate dehydratase/shikimate dehydrogenase; SMK, Shikimate kinase; EPSPS, 3-Phosphoshikimate 1-carboxyvinyltransferase; CS, Chorismate synthase; IS/MenF, Menaquinone-specific/Isochorismate synthase; MenE, o-Succinylbenzoate-CoA ligase; MenB, 1,4-Dihydroxy-2-naphthoyl-CoA synthase; DXS, 1-Deoxy-Dxylulose-5-phosphate synthase; DXR, 1-Deoxy-D-xylulose-5-phosphate reductoisomerase; MCT, 2-C-Methyl-D-erythritol 4-phosphate cytidylyltransferase; CMEK, 4-(cytidine 50-diphospho)-2-C-methyl-D-erythritol kinase; ISPF, 2-C-methyl-D-erythritol 2,4-cyclodiphosphate synthase; HDS, (E)-4-hydroxy-3-methylbut-2-enyl-diphosphate synthase; HDR, 4-hydroxy-3-methylbut-2-en-1-yl diphosphate reductase; AACT, Acetyl-CoA C-acetyltransferase; HMGS, Hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA synthase; HMGR, Hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA reductase; MK, Mevalonate kinase; PMK, Phosphomevalonate kinase; MVD, Diphosphomevalonate decarboxylase; IPPS, Isopentenyl-diphosphate Delta-isomerase; PKS III, Type III polyketide synthase; PKC, Polyketide cyclase/dehydratase; CYP, Cytochrome P450; UGT, UDP-Glucosyl Transferase

The biosynthesis of gallic acids and catechins

Gallic acid and catechin, as strong active antioxidants, are polyphenols with a variety of physiological functions (Li et al. 2020). Here, we also identified multiple structural enzyme unigenes differentially expressed in these two biosynthesis pathways (Fig. 6, Table S9). Gallic acid is synthesized mainly with 3-dehydroshikimic acid, an intermediate product of shikimate pathway, and seven DEGs were involved in this study. Except DHQS2 constitutionally down-regulated in each examined tissue of ZK, most other DEGs were up-regulated in roots. The biosynthesis of catechins begins with shikimate and phenylpropane pathways, in which a wide range of DEGs were identified in our transcriptome profiles. Genes encoding SMK, EPSPS, and most PDT were found to have high transcript levels in one or more samples of ZK. Relatively less DEGs were detected after the formation of 4-Coumaroyl-CoA, except for genes encoding the synthase CHS that were induced largely in roots and leaves. We also observed several HCT copies, of which two had relatively higher expression levels but proved to be down-regulated in roots and/or stems of ZK. In the downstream pathway of catechin synthesis, both DFR and ANR showed high transcript levels in roots and stems, whereas ANS and two LAR copies were mostly suppressed at aerial parts, implying a complex regulatory process in the formation of different types of catechins.

Fig. 6.

Representation of catechin and gallic acid biosynthetic pathways in R. palmatum complex. Expression profiles of DEGs involved in catechin and gallic acid biosynthesis are shown in heatmap plots. Color-coded blocks represent the variations of log10(FPKM+1). UGGT, 1-O-galloyl-β-D- glucosyltransferase; CS, Chorismate synthase; CM, Chorismate mutase; PDT, Prephenate dehydratase; TAT, Tyrosine transaminase; PAL, phenylalanine ammonia lyase; C4H, cinnamate 4-hydroxylase; 4CL, 4-coumarate-CoA ligases; HCT, hydroxycinnamoyl transferase; C3’H, p-coumarate 3-hydroxylase; CHS, chalcone synthase; CHI, chalcone isomerase; F3H, flavanone 3-hydroxylase; F3’H, flavonoid 3’-hydroxylase; F3′5’H, flavanoid 3’,5’-hydroxylase; DFR, dihydroflavonol 4-reductase; ANS, anthocyanin synthase; LAR, leucoanthocyanidin reductase; ANR, anthocyanidin reductase; FGS, flavan-3-ol gallate synthase

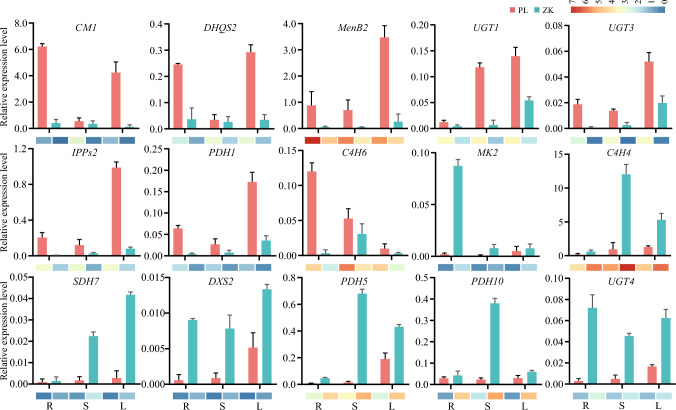

Validation of differentially expressed genes by qRT-PCR

To validate the RNA-seq data in this study, 15 representative DEGs related to the synthesis of bioactive constituents were subjected to qRT-PCR detection to examine their transcript levels. Expression levels of these DEGs were found to be in parallel with the patterns of their transcript profiles generated by RNA-seq analysis (Fig. 7). For example, by both qRT-PCR and RNA-seq, MenB2 and UGT3 were observed to be down-regulated in three different tissues of ZK, while DXS2 and UGT4 were highly induced. These results indicate the reliability and accuracy of our transcriptome data.

Fig. 7.

Validation of DEG expression patterns of PL and ZK in three different tissues using qRT-PCR. Differential expression patterns obtained by RNA-seq are displayed at the down margin. R, roots; S, stems; L, leaves. CM1, Unigene_316515; DHQS2, Unigene_045627; MenB2, Unigene_487779; UGT1, Unigene_022183; UGT3, Unigene_313286; IPPs2, Unigene_314337; PDH1, Unigene_315104; C4H6, Unigene_047667; MK2, Unigene_503449; C4H4, Unigene_495460; SDH7, Unigene_503899; DXS2, Unigene_500280; PDH5, Unigene_016136; PDH10, Unigene_412383; UGT4, Unigene_501856

Discussion

R. palmatum complex, as a traditional Chinese medicinal plant used worldwide, has attracted extensive attention from many scholars. The content of bioactive constituents is one of the most important characteristics in rhubarb. Although considerable efforts have been made to explore the chemical compositions and pharmaceutical properties of rhubarb (Sun et al. 2016; Xian et al. 2017), the achievements on molecular level, especially the understanding of its metabolite biosynthesis, are still very limited (Liu et al. 2020).

Thanks to the advancements in sequencing technologies and decreasing costs, studying about gene expression and regulation has become a lot easier today. As such, transcriptome sequencing has been widely utilized to investigate expression variations of transcripts in various plants (Guo et al. 2021). Insights into the transcriptional dynamics of active compound synthesis can help to identify functional genes and unravel regulatory mechanism of medicinal plants. To clarify the transcriptional activity of R. palmatum complex in bioactive constituent synthesis, we performed comparative transcriptome sequencing on three different tissues of PL and ZK with different levels of anthraquinone contents. Here, a total of 58,782 unigenes were assembled on a base of ~ 0.52 billion clean reads from 18 cDNA libraries (Table 1). This number was far lower than the number of genes assembled respectively from PL and ZK samples, but the value of N50 length was increased by 3–4 times to more than 2600 bp. The same does also hold true compared to similar work on the transcriptomes of Rheum seedlings, in which more unigenes with shorter N50 length were detected (Li et al. 2018; Hei et al. 2019). This result indicates the higher integrity of unigenes obtained by combined assembly in this study, providing a more reliable dataset for mining genes related to metabolite biosynthesis in rhubarb.

Approximately 80% of the unigenes were found to have at least one blast hit in public databases, while the remaining 12,232 unigenes cannot be functionally annotated. Ruling out the possibility of sequencing and assembly errors, we speculate that this may be due to the deficiency of relevant genomic or transcriptomic resources deposited in the current databases, or that these unannotated genes are new transcripts unique to Rheum plants. The species with highest homology to R. palmatum complex was Beta vulgaris by conducting blast against Nr database (Fig. S2), which was consistent with the annotation results in previous comparable work (Li et al. 2018; Hei et al. 2019). This reveals that the number of assembled unigenes in different studies has little effect on the annotation results of the close species of a target species.

Anthraquinone and its derivatives are considered to be the main constituents in rhubarb. Various studies have been conducted to measure the content of anthraquinones in different tissues of Rheum species using HPLC (Hu et al. 2022; Zhou et al. 2021). The results showed that the contents of five free anthraquinones were higher in roots than those in aerial parts, which was consistent with the finding in this study (Fig. 1). Here, PL and ZK with contrasting levels of anthraquinones were screened and subjected to transcriptome sequencing, in order to pinpoint genes underlying anthraquinone biosynthesis. Due to the dominant role of roots in the synthesis of anthraquinones, the difference of anthraquinone in roots played a leading role in the difference of total content between two Rheum materials, even though less variation could be observed in aerial parts (Fig. 1). A total of 20 DEGs related to anthraquinone biosynthesis was detected in roots, while 27 and 31 were identified in stems and leaves, respectively (Table S8). However, among these DEGs, most showed higher transcript levels in roots of ZK rich in anthraquinones, while more genes were down-regulated than up-regulated in stems with least bioactive constituents. Comparable numbers of induced- and suppressed-genes were identified in leaves of ZK, the former, however, showed larger variability with high FC values in expression levels (Table S8). These results are expectable and highly consistent with the differences of anthraquinone contents in these tissues. This reversed pattern of gene expression, which was also found in the transcriptome profiles of Xanthomonas resistance in rapeseed and cytoplasmic male sterility in cotton (Yang et al. 2018; 2022), may provide valuable clues related to target traits.

Our transcriptomic analysis revealed that multiple structural enzyme genes involved in anthraquinone biosynthesis were significantly up-regulated in roots of ZK (Table S8). This includes several genes encoding DAHPS4, SDH7, SDH8, SMK5, and PHYLLO2 that function in shikimate pathway. The enzyme DAHPS4 of Angelica sinensis was recently proven to play a role in phthalide accumulation by heterologous expression in E. coli (Feng et al. 2022). Transgenic plants with suppressed expression of SDH by RNAi were found to display reduced level of aromatic amino acids and downstream products in tobacco (Ding et al. 2007). Also, one phosphate synthase encoding gene responsible for the initial step of MEP pathway, i.e., DXS2, was identified to be constitutively up-regulated in all analyzed tissues. DXS is known to play key roles in a variety of biological processes, such as photosynthesis, hormone regulation, stress resistance, and plant-pathogen interaction (Tian et al. 2022; Zhang et al. 2020). MVA pathway is another important process contributing to the biosynthesis of anthraquinone. Here we detected several DEGs involved in almost every committed step of this pathway, including AACT9, HMGR9, MK2, and MVD2. Overexpression of EkAACT in Arabidopsis was shown to possess higher content of total triterpenoids and higher enzyme activities when exposed to the treatments of NaCl and PEG (Wang et al. 2022). We speculate that these genes could be the key factors for higher accumulation of anthraquinones in the roots of Rheum plants in Zeku County.

Conclusion

In this study, we conducted comparative transcriptome analyses on roots, stems, and leaves of PL and ZK with different anthraquinone contents, in order to pinpoint key genes and secondary metabolic pathways responsible for internal quality difference of Rheum species. Our results indicate that multiple structural enzyme genes involved in the biosynthesis of anthraquinones, gallic acids, and catechins, were shown variable expression patterns levels in different Rheum materials. These candidate genes may provide a valuable resource for future functional studies to inform breeding for high-quality rhubarb.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Quality evaluation of RNA-seq data in this study. a, PCA explaining the major component of variance. b, Heatmap of correlation matrix between different RNA-seq samples. c, Boxplot showing the expression levels of all genes across different samples (PDF 1555 KB)

Species distribution of non-redundant unigenes against NCBI nr database (PDF 419 KB)

Bubble graphs showing the distribution of enriched KEGG pathways of DEGs identified in roots (a), stems (b), and leaves (c). The horizontal and vertical axes of bubble graphs represent -log10(P-value) and KEGG pathways, respectively. The bubble size indicates the number of enriched DEGs per pathway (PDF 322 KB)

Network topology analysis. a, Topology and connectivity based on soft threshold powers. b, Correlations between modules and samples. c, Scatter plot showing correlation relationship between gene-lightgreen module and gene-trait. d, Expression heatmap of DEGs clustered in lightgreen module (PDF 757 KB)

Acknowledgements

This study was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 32370408) and Shaanxi Institute of Basic Sciences (Chemistry, Biology) Scientific Research Program Project (No. 22JHZ005).

Author contributions

XW, TZ, and DC designed research, supplied funding, and revised manuscript. LY performed research, analyzed data, and wrote draft manuscript. JS and TYZ performed experiments and assisted in data analysis. All authors have read and approved the final version of manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

Raw data used in this study have been deposited in NCBI database with BioProject numbers PRJNA735904 and PRJNA827652.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Tao Zhou, Email: zhoutao196@mail.xjtu.edu.cn.

Xumei Wang, Email: wangxumei@mail.xjtu.edu.cn.

References

- Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schäffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ (1997) Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res 25(17):3389–3402. 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastian M, Heymann S, Jacomy M (2009) Gephi: an open source software for exploring and manipulating networks. Proc Int AAAI Conf Web Soc Media 3(1):361–362. 10.1609/icwsm.v3i1.13937 10.1609/icwsm.v3i1.13937 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B (2014) Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30(15):2114–2120. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinese Pharmacopoeia Committee (2020) Pharmacopoeia of the People’s Republic of China, part 1. China Medical Science Press, Beijing [Google Scholar]

- Ding L, Hofius D, Hajirezaei MR, Fernie AR, Börnke F, Sonnewald U (2007) Functional analysis of the essential bifunctional tobacco enzyme 3-dehydroquinate dehydratase/shikimate dehydrogenase in transgenic tobacco plants. J Exp Bot 58(8):2053–2067. 10.1093/jxb/erm059 10.1093/jxb/erm059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng WM, Liu P, Yan H, Yu G, Zhang S, Jiang S, Shang EX, Qian DW, Duan JA (2022) Investigation of enzymes in the phthalide biosynthetic pathway in Angelica sinensis using integrative metabolite profiles and transcriptome analysis. Front Plant Sci 13:928760. 10.3389/fpls.2022.928760 10.3389/fpls.2022.928760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu L, Niu B, Zhu Z, Wu S, Li W (2012) CD-HIT: accelerated for clustering the next-generation sequencing data. Bioinformatics 28(23):3150–3152. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts565 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabherr MG, Haas BJ, Yassour M, Levin JZ, Thompson DA, Amit I, Adiconis X, Fan L, Raychowdhury R, Zeng Q, Chen Z, Mauceli E, Hacohen N, Gnirke A, Rhind N, di Palma F, Birren BW, Nusbaum C, Lindblad-Toh K, Friedman N, Regev A (2011) Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nat Biotechnol 29(7):644–652. 10.1038/nbt.1883 10.1038/nbt.1883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo J, Huang Z, Sun J, Cui X, Liu Y (2021) Research progress and future development trends in medicinal plant transcriptomics. Front Plant Sci 12:691838. 10.3389/fpls.2021.691838 10.3389/fpls.2021.691838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hei X, Li H, Li Y, Wang G, Xu J, Peng L, Deng C, Yan Y, Guo S, Zhang G (2019) High-throughput transcriptomic sequencing of Rheum officinale Baill. seedlings and screening of genes in anthraquinone biosynthesis. Chin Pharm J 54(7):526–535. 10.11669/cpj.2019.07.003 10.11669/cpj.2019.07.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y, Zhang H, Sun J, Li W, Li Y (2022) Comparative transcriptome analysis of different tissues of Rheum tanguticum Maxim. ex Balf. (Polygonaceae) reveals putative genes involved in anthraquinone biosynthesis. Genet Mol Biol 45(3):e20210407. 10.1590/1678-4685-GMB-2021-0407 10.1590/1678-4685-GMB-2021-0407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia C, Zhang Y, Zhu L, Zhang R (2015) Application progress of transcriptome sequencing technology in biological sequencing. Mol Plant Breed 13(10):2388–2394 [Google Scholar]

- Kang SH, Pandey RP, Lee CM, Sim JS, Jeong JT, Choi BS, Jung M, Ginzburg D, Zhao K, Won SY et al (2020) Genome-enabled discovery of anthraquinone biosynthesis in Senna tora. Nat Commun 11(1):5875. 10.1038/s41467-020-19681-1 10.1038/s41467-020-19681-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai F, Zhang Y, Xie DP, Mai ST, Weng YN, Du JD, Wu GP, Zheng JX, Han Y (2015) A systematic review of rhubarb (a traditional Chinese medicine) used for the treatment of experimental sepsis. Evid Based Complement Altern Med 2015:131283. 10.1155/2015/131283 10.1155/2015/131283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langfelder P, Horvath S (2008) WGCNA: an R package for weighted correlation network analysis. BMC Bioinform 9:559. 10.1186/1471-2105-9-559 10.1186/1471-2105-9-559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmead B, Salzberg SL (2012) Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods 9(4):357–359. 10.1038/nmeth.1923 10.1038/nmeth.1923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B, Dewey CN (2011) RSEM: accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinform 12:323. 10.1186/1471-2105-12-323 10.1186/1471-2105-12-323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Liu K, Wei S, Cheng X, Liu J, Ren G, Wang W (2014) Resource situation investigation about Rheum tanguticum and its sustainable utilization analysis in main production area of China. China J Chin Mater Med 39(8):1407–1412 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Zhang N, Li Y, Hei X, Li Y, Deng C, Yan Y, Liu M, Zhang G (2018) High-throughput transcriptomic sequencing of Rheum palmatum L. seedlings and elucidation of genes in anthraquinone biosynthesis. Acta Pharm Sinica 53(11):1908–1917. 10.16438/J.0513-4870.2018-0547 10.16438/J.0513-4870.2018-0547 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Zhang S, Sun Y (2020) Measurement of catechin and gallic acid in tea wine with HPLC. Saudi J Biol Sci 27(1):214–221. 10.1016/j.sjbs.2019.08.011 10.1016/j.sjbs.2019.08.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Leng L, Liu Y, Gao H, Yang W, Chen S, Liu A (2020) Identification and quantification of target metabolites combined with transcriptome of two rheum species focused on anthraquinone and flavonoids biosynthesis. Sci Rep 10(1):20241. 10.1038/s41598-020-77356-9 10.1038/s41598-020-77356-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Tang N, Xu F, Chen Z, Zhang X, Ye J, Liao Y, Zhang W, Kim SU, Wu P, Cao Z (2022) SMRT and Illumina RNA sequencing reveal the complexity of terpenoid biosynthesis in Zanthoxylum armatum. Tree Physiol 42(3):664–683. 10.1093/treephys/tpab114 10.1093/treephys/tpab114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Han L, Li G, Zhang A, Liu X, Zhao M (2023) Transcriptome and metabolome profiling of the medicinal plant Veratrum mengtzeanum reveal key components of the alkaloid biosynthesis. Front Genet 14:1023433. 10.3389/fgene.2023.1023433 10.3389/fgene.2023.1023433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD (2001) Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 25(4):402–408 10.1006/meth.2001.1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Love MI, Huber W, Anders S (2014) Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol 15(12):550. 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu C, Mao S, Tong H, Ding Y (2018) Progress in the synthesis of catechin and its derivatives. Food Sci 39(11):316–326 [Google Scholar]

- Mala D, Awasthi S, Sharma NK, Swarnkar MK, Shankar R, Kumar S (2021) Comparative transcriptome analysis of Rheum australe, an endangered medicinal herb, growing in its natural habitat and those grown in controlled growth chambers. Sci Rep 11(1):3702. 10.1038/s41598-020-79020-8 10.1038/s41598-020-79020-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandith S, Khan I (2022) Genus Rheum (Polygonaceae): a global perspective. 1st Edition. CRC Press [Google Scholar]

- Rama Reddy NR, Mehta RH, Soni PH, Makasana J, Gajbhiye NA, Ponnuchamy M, Kumar J (2015) Next generation sequencing and transcriptome analysis predicts biosynthetic pathway of sennosides from Senna (Cassia angustifolia Vahl.), a non-model plant with potent laxative properties. PLoS ONE 10(6):e0129422. 10.1371/journal.pone.0129422 10.1371/journal.pone.0129422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun H, Luo G, Chen D, Xiang Z (2016) A comprehensive and system review for the pharmacological mechanism of action of Rhein, an active anthraquinone ingredient. Front Pharmacol 7:247. 10.3389/fphar.2016.00247 10.3389/fphar.2016.00247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian S, Wang D, Yang L, Zhang Z, Liu Y (2022) A systematic review of 1-Deoxy-D-xylulose-5-phosphate synthase in terpenoid biosynthesis in plants. Plant Growth Regul 96:221–235. 10.1007/s10725-021-00784-8 10.1007/s10725-021-00784-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JB, Qin Y, Kong WJ, Wang ZW, Zeng LN, Fang F, Jin C, Yl Z, Xiao XH (2011) Identification of the antidiarrhoeal components in official rhubarb using liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry. Food Chem 129(4):1737–1743. 10.1016/J.FOODCHEM.2011.06.041 10.1016/J.FOODCHEM.2011.06.041 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Lu Z, Liu Y, Wang M, Fu S, Zhang Q, Zhao H, Zhang Z, Xie Z, Huang Z et al (2017) Rapid analysis on phenolic compounds in Rheum palmatum based on UPLC-Q-TOF/MSE combined with diagnostic ions filter. China J Chin Mater Med 42(10):1922–1931. 10.19540/j.cnki.cjcmm.20170317.001 10.19540/j.cnki.cjcmm.20170317.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Feng L, Zhou T, Ruhsam M, Huang L, Hou X, Sun X, Fan K, Huang M, Zhou Y, Song J (2018) Genetic and chemical differentiation characterizes top-geoherb and non-top-geoherb areas in the TCM herb rhubarb. Sci Rep 8(1):9424. 10.1038/s41598-018-27510-1 10.1038/s41598-018-27510-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Hu H, Wu Z, Fan H, Wang G, Chai T, Wang H (2021) Tissue-specific transcriptome analyses reveal candidate genes for stilbene, flavonoid and anthraquinone biosynthesis in the medicinal plant Polygonum cuspidatum. BMC Genom 22(1):353. 10.1186/s12864-021-07658-3 10.1186/s12864-021-07658-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M, Zheng Z, Tian Z, Zhang H, Zhu C, Yao X, Yang Y, Cai X (2022) Molecular cloning and analysis of an Acetyl-CoA C-acetyltransferase gene (EkAACT) from Euphorbia kansui Liou. Plants (basel) 11(12):1539. 10.3390/plants11121539 10.3390/plants11121539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu W, Yan R, Yao M, Zhan Y, Wang Y (2014) Pharmacokinetics of anthraquinones in rat plasma after oral administration of a rhubarb extract. Biomed Chromatogr 28(4):564–572. 10.1002/bmc.3070 10.1002/bmc.3070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xian J, Fu J, Cheng J, Zhang J, Jiao M, Wang S, Liu A (2017) Isolation and identification of chemical constituents from aerial parts of Rheum officinale. Chin J Exp Tradit Med Form 23(14):45–51. 10.13422/j.cnki.syfjx.2017140045 10.13422/j.cnki.syfjx.2017140045 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L, Wu Y, Zhang M, Zhang J, Stewart JM, Xing C, Wu J, Jin S (2018) Transcriptome, cytological and biochemical analysis of cytoplasmic male sterility and maintainer line in CMS-D8 cotton. Plant Mol Biol 97(6):537–551. 10.1007/s11103-018-0757-2 10.1007/s11103-018-0757-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L, Zhao C, Bai Z, Yang L, Schranz ME, Liu S, Bouwmeester K (2022) Comparative transcriptome analysis of compatible and incompatible Brassica napus—Xanthomonas campestris interactions. Front Plant Sci 13:960874. 10.3389/fpls.2022.960874 10.3389/fpls.2022.960874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu G, Wang LG, Han Y, He QY (2012) clusterProfiler: an R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. OMICS 16(5):284–287. 10.1089/omi.2011.0118 10.1089/omi.2011.0118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S, Ding G, He W, Liu K, Luo Y, Tang J, He N (2020) Functional characterization of the 1-Deoxy-D-Xylulose 5-Phosphate synthase genes in Morus notabilis. Front Plant Sci 11:1142. 10.3389/fpls.2020.01142 10.3389/fpls.2020.01142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou T, Zhang T, Sun J, Zhu H, Zhang M, Wang X (2021) Tissue-specific transcriptome for Rheum tanguticum reveals candidate genes related to the anthraquinones biosynthesis. Physiol Mol Biol Plants 27(11):2487–2501. 10.1007/s12298-021-01099-8 10.1007/s12298-021-01099-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L, Sun J, Zhang T, Tang Y, Liu J, Gao C, Zhai Y, Guo Y, Feng L, Zhang X, Zhou T, Wang X (2022) Comparative transcriptome analyses of different Rheum officinale tissues reveal differentially expressed genes associated with anthraquinone, catechin, and gallic acid biosynthesis. Genes (basel) 13(9):1592. 10.3390/genes13091592 10.3390/genes13091592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu H, Hou X, Zhang M, Zhou T, Feng L, Wang X (2021) Content determination of anthraquinone and quality evaluation of the population of source plants of rhubarb based on HPLC. Chin Tradit Herb Drugs 52(17):5295–5302 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Quality evaluation of RNA-seq data in this study. a, PCA explaining the major component of variance. b, Heatmap of correlation matrix between different RNA-seq samples. c, Boxplot showing the expression levels of all genes across different samples (PDF 1555 KB)

Species distribution of non-redundant unigenes against NCBI nr database (PDF 419 KB)

Bubble graphs showing the distribution of enriched KEGG pathways of DEGs identified in roots (a), stems (b), and leaves (c). The horizontal and vertical axes of bubble graphs represent -log10(P-value) and KEGG pathways, respectively. The bubble size indicates the number of enriched DEGs per pathway (PDF 322 KB)

Network topology analysis. a, Topology and connectivity based on soft threshold powers. b, Correlations between modules and samples. c, Scatter plot showing correlation relationship between gene-lightgreen module and gene-trait. d, Expression heatmap of DEGs clustered in lightgreen module (PDF 757 KB)

Data Availability Statement

Raw data used in this study have been deposited in NCBI database with BioProject numbers PRJNA735904 and PRJNA827652.