Abstract

Formative research is an important component of health communication campaign development. Rapid message testing approaches are useful for testing new messaging quickly and efficiently during public health emergencies, such as COVID-19, when guidance and recommendations are rapidly changing. Wiki surveys simultaneously collect quantitative message testing data and qualitative feedback on potential social media campaign messages. Philly CEAL used wiki surveys to test messages about COVID-19 vaccinations for dissemination on social media. A cross-sectional survey of Philadelphia residents (N = 199) was conducted between January and March 2023. Wiki surveys were used to assess the perceived effectiveness of messages promoting the updated COVID-19 booster and child vaccination. In each wiki survey, participants were presented with two messages and asked to select the one that they perceived as most effective. Participants could alternatively select “can’t decide” or submit their own message. A score estimating the probability of selection was calculated for each message. Participant-generated messages were routinely reviewed and incorporated into the message pool. Participants cast a total of 32,281 votes on messages seeded by the research team (n = 20) and participants (n = 43). The highest scoring messages were those that were generated by participants and spoke to getting your child vaccinated to protect them against serious illness and getting the booster to protect your health and that of your community. These messages were incorporated into social media posts disseminated by Philly CEAL’s social media accounts. Wiki surveys are a feasible and efficient method of rapid message testing for social media campaigns.

Keywords: COVID-19, Booster vaccination, Formative research, Health message testing, Wiki survey

Subject terms: Human behaviour, Risk factors

Introduction

Public health communication is a key strategy used throughout the COVID-19 pandemic to combat misinformation1, promote health behaviors2, and address inequities3. Health communication campaigns are more likely to be successful when formative research is conducted to understand the beliefs and behaviors of the intended audience and to pretest messages for appropriateness and effectiveness4. COVID-19 campaigns have used long-established formative research approaches such as observational surveys5,6, survey experiments7,8, individual interviews6, and focus groups5,9. While technology can accelerate formative research, many of these established methods can take months to develop research instruments, collect and analyze data, and disseminate final campaign materials.

Because of the formative research timeline and the rapidly changing environment of COVID-19 and other emergent outbreaks10,11, findings can become outdated before campaigns are activated. Conducting no formative research, however, can lead to ineffective or harmful messaging. Rapid and responsive message testing approaches are most promising to quickly develop effective campaigns, especially in the context of a pandemic such as COVID-1912. Multiple rapid message testing studies for COVID-19 utilized digital survey platforms12,13 and text ads14. These approaches hold promise for effectively eliciting relevant beliefs and disseminating messaging for clinical and healthcare topics12.

Wiki surveys are a rapid message testing approach that allow researchers to conduct quantitative testing similar to A/B testing, a user experience research methodology that consists of randomized experiments that compare the perceived effectiveness of two different messages12. A novel feature of wiki surveys is the integration of user-generated messages into the experimental design. In this way, users can rate existing messages and suggest new messages in the same platform through a seamless user experience. Then, future users give ratings for these user-generated messages as well as researcher-generated messages. Wiki surveys investigating message strength in the areas of the legalization of marijuana and sustainability and education policy found that user-generated messages were among the highest-rated15,16.

We used wiki surveys hosted on the All Our Ideas (allourideas.org) platform in January to March 2023 to rapidly test messages promoting pediatric COVID-19 vaccination and booster vaccinations for dissemination on Philly CEAL’s social media accounts. Philly CEAL, part of the National Institutes of Health’s (NIH) Community Engagement Alliance against COVID-19 Disparities (CEAL)17, is a community-wide alliance working to provide the Philadelphia community with resources to reduce COVID-19 disparities in testing, vaccination, and participation in clinical trials and to prevent the spread of misinformation. At the time of the study, CDC recommended the COVID-19 vaccine for all adults and children 6 months and older18 and the bivalent COVID-19 booster for immunized adults and children over 12 years old19. For the wiki surveys, adults who lived or worked in Philadelphia were randomly presented with one of two messages and asked to select the message they thought would be most effective for promoting pediatric or booster COVID-19 vaccinations. Each message received score quantifying the probability that the message would be perceived as more effective than a randomly selected alternative. This paper describes the results of the wiki surveys, how these results were translated into subsequent Philly CEAL’s social media messaging, and how wiki surveys were implemented to conduct rapid message testing.

Results

Participant characteristics

Of the 544 people invited, 199 (36.6%) completed the survey and are included in the analysis. Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of our sample. The mean age was 37.4 years (SD = 11.3). Most participants identified as women (74%) and heterosexual or straight (73%). Most (60%) participants were White; 27% were Black or African American, 13% were Asian, and 3% were American Indian or Alaska Native. Almost 10% identified as Hispanic or Latino ethnicity. Three-quarters of participants had at least a Bachelor’s degree. Nearly all participants were fully vaccinated (94%), and among those fully vaccinated, about half had received two boosters (49%). Table 2 summarizes the vaccination status of the participants’ children. Approximately one-third (37%) of participants had at least one child under the age of 18. Most (62%) reported that all their children were fully vaccinated, and 16% reported not vaccinating any of their children.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics (N = 199).

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| 18–24 | 21 | (10.6) |

| 25–34 | 67 | (33.7) |

| 35–44 | 71 | (35.7) |

| 45–54 | 23 | (11.6) |

| 55–64 | 11 | (5.5) |

| 65+ | 6 | (3.0) |

| Gender | ||

| Woman | 147 | (73.9) |

| Man | 44 | (22.1) |

| Nonbinary | 7 | (3.5) |

| Other | 1 | (0.5) |

| Sexuality | ||

| Heterosexual or straight | 145 | (72.9) |

| Gay or lesbian | 19 | (9.5) |

| Bisexual | 29 | (14.6) |

| Other (open-ended responses including queer, pansexual, and asexual) | 6 | (3.0) |

| Race | ||

| White | 119 | (59.8) |

| Black or african american | 53 | (26.6) |

| American indian or alaska native | 6 | (3.0) |

| Asian | 25 | (12.6) |

| Other | 9 | (4.5) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic or latino | 19 | (9.5) |

| Education | ||

| High school diploma or GED | 10 | (5.0) |

| Some college, associate’s degree, or vocational training | 40 | (20.1) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 87 | (43.7) |

| Advanced degree | 62 | (31.2) |

| COVID-19 vaccination status | ||

| Fully vaccinated | 188 | (94.5) |

| Partially vaccinated | 9 | (4.5) |

| Not vaccinated | 2 | (1.0) |

| COVID-19 booster status | ||

| Three or more boosters | 24 | (12.8) |

| Two boosters | 93 | (49.5) |

| One booster | 50 | (26.6) |

| No boosters | 21 | (11.2) |

Table 2.

Top 10 booster messages by message score.

| Message | Source | Total votes | Vote results | Score | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Win | Loss | Can’t decide | ||||

| Don't gamble with your health. Stay up to date with your Covid-19 boosters | Participant | 1462 | 931 | 516 | 15 | 64.3 |

| Each reinfection increases chances of serious and long term COVID complications. Get the booster to protect yourself and your community | Participant | 1577 | 931 | 603 | 43 | 60.7 |

| COVID damage can be silent and stealthy. Protect your long-term health by boosting against new variants and curbing the spread | Participant | 1521 | 866 | 619 | 36 | 58.3 |

| You can get your COVID-19 and flu vaccine on the same day, during the same doctor's visit! Both vaccines are safe and effective | Seed | 1646 | 942 | 676 | 28 | 58.2 |

| COVID-19 vaccines protect against severe disease, hospitalization, and death, so it's essential to stay up to date with your booster dose! | Seed | 1616 | 879 | 692 | 45 | 55.9 |

| To protect yourself and your loved ones, get the COVID-19 booster to protect against variants that may threaten your community | Participant | 592 | 327 | 262 | 3 | 55.5 |

| The pandemic is not over, people are getting sick from COVID-19 variants daily. Protect your community by getting a booster dose! | Seed | 1648 | 903 | 724 | 21 | 55.5 |

| To protect yourself and your community, stay up to date with COVID-19 vaccinations | Participant | 1448 | 786 | 632 | 30 | 55.4 |

| Both COVID-19 and the flu are spreading this winter. To protect your community, get tested and stay up to date with vaccinations | Seed | 1650 | 887 | 723 | 40 | 55.1 |

| Help protect vulnerable people in your community by getting your free COVID-19 booster shot | Participant | 1505 | 807 | 662 | 36 | 54.9 |

Booster messages

Participants voted a total of 13,897 times on 9 seed and 10 participant-generated messages. Table 2 presents the voting results and the message scores for the top 10 booster messages. The three highest performing messages were participant-generated and focused on the health protection provided by the boosters and the importance of community protection (e.g., “Don’t gamble with your health. Stay up to date with your Covid-19 boosters” and “Each reinfection increases chances of serious and long term COVID complications. Get the booster to protect yourself and your community”). Results for all seed and participant-generated messages are available in Appendix 3. Seven of the 8 messages that had less than a 50% chance of being chosen over a randomly selected message were about COVID-19 variants (e.g., “Many COVID-19 variants are connected to Omicron, which the booster shot helps protect against!”).

Child vaccination messages

Participants cast a total of 18,384 votes on 11 seed and 33 participant-generated messages. Table 3 presents the results for the 10 child vaccination messages with the highest message ratings. Of the nine highest performing messages, 7 were participant-generated and all addressed child vaccine protection from serious illness (e.g., “Vaccination is the best way to protect your child from serious illness against COVID-19” and “Protect your children from serious health complications of COVID-19 by getting them vaccinated”). Message scores and voting results for all seed and participant-generated messages are available in Appendix 4. Messages that focused solely on eligibility for and availability of vaccinations had less than a 50% chance of being chosen over a randomly selected message (e.g., “On November 2, 2021, all Philadelphians 5–11 years became eligible for the vaccine. Thousands of children have since been vaccinated”).

Table 3.

Top 10 child vaccination messages by message score.

| Message | Source | Total votes | Vote results | Score | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Win | Loss | Can’t decide | ||||

| Vaccination is the best way to protect your child from serious illness against COVID-19 | Participant | 418 | 265 | 150 | 3 | 63.8 |

| The best way to protect your child from serious illness is to get them vaccinated | Participant | 1215 | 763 | 448 | 4 | 63.0 |

| Protect your children from serious health complications of COVID-19 by getting them vaccinated | Participant | 964 | 599 | 359 | 6 | 62.5 |

| Each reinfection increases the chance of serious long-term complications from COVID-19. Get yourself and your family vaccinated today! | Participant | 737 | 449 | 284 | 4 | 61.2 |

| COVID-19 vaccines are the best way to protect your child from serious illness requiring hospitalization | Seed | 1323 | 784 | 530 | 9 | 59.7 |

| Protect your child against serious illness by getting them vaccinated against COVID-19 | Participant | 430 | 253 | 174 | 3 | 59.2 |

| Vaccination is the best way to protect your child and those around them from serious illness related to COVID-19 | Participant | 333 | 194 | 135 | 4 | 58.9 |

| Covid-19 vaccines and boosters are the best way to prevent illness and long-term symptoms | Participant | 472 | 277 | 194 | 1 | 58.8 |

| COVID-19 vaccines prevent children in Philadelphia from getting seriously sick if they do get COVID-19 | Seed | 1297 | 743 | 542 | 12 | 57.8 |

| Getting COVID can lead to health complications later in life. Vaccines are the best preventive measure against them | Participant | 962 | 543 | 410 | 9 | 57.0 |

Discussion

We conducted wiki surveys in January-March 2023 to rapidly generate and test messages to promote COVID-19 boosters and child vaccinations among Philadelphia residents and incorporated highly rated messages into social media posts on Philly CEAL accounts. Notably, participant-generated messages were consistently perceived as more effective than investigator-generated seed messages in our study. This finding is consistent with results of previous wiki surveys15,16 and underscores the importance of obtaining qualitative feedback during rapid message testing. While some participant-generated messages were novel (e.g., “COVID damage can be silent and stealthy”), others reflected arguments from seed messages in participants’ own words. These messages usually outperformed the seed message. For example, the participant-generated message “Vaccination is the best way to protect your child from serious illness against COVID-19” was rated more highly than the seed message “COVID-19 vaccines prevent children in Philadelphia from getting seriously sick if they do get COVID-19.”

Wiki surveys have been previously used to generate ideas for New York City’s sustainability plan15 and to assess the strength of arguments for marijuana legalization16. To our knowledge, this is the first published study to use wiki surveys to rapidly evaluate perceived effectiveness of and generate messages for promoting COVID-19 vaccinations and disseminate highly rated messages through a social media campaign. Examples of the resulting posts on Philly CEAL’s social media accounts are shown in Appendix 5. The study establishes the feasibility and advantages of using wiki surveys for rapid message testing, especially when time and resources for formative research may be limited.

Using wiki surveys for rapid message testing has several advantages compared to other formative research approaches. First, community partners and residents were able to contribute messages and these messages were iteratively incorporated into the messaging testing pool. Second, other message testing surveys have a fixed set of items. Adding new items would increase the length of the survey, prevent comparisons over time, and require time for revisions and publishing of updated versions. Messages can be added to wiki surveys quickly and efficiently, and doing so does not add to participant burden because participants control how many votes they cast. Third, the message score statistically accounts for the fact that some participants would not have been able to vote on messages that were added to the pool after their votes were cast.

There are several important limitations to the wiki survey approach. The seed messages based on contemporaneous Philly CEAL and NIH CEAL social media posts may have constrained the range of arguments and themes that participants thought of when generating additional messages. Only brief messages that are less than 140 characters and include only text can be tested in the All Our Ideas platform’s current version. While this is acceptable for testing messages for social media, the wiki survey approach may not be feasible for other avenues of dissemination. Currently, the wiki survey data cannot be linked to survey platforms by passing embedded variables. We are therefore unable to compare how message ratings differed by participant characteristics or determine how many votes individual participants cast. Although the wiki survey platform reduces the burden of updating the message pool and analyzing data, resources are still required to stagger recruitment so that there is sufficient time for messages to be generated by participants, added to the pool, and voted on by subsequent participants. New messages also needed to be reviewed before being added to the pool for appropriateness and clarity.

In addition to the limitations of wiki surveys generally, our study has several limitations. The community partners and prior survey participants are not representative of all Philadelphia residents nor of our target audiences. Our sample was highly educated, with 44% having a college degree and 31% an advanced degree. More than 94% of our sample were fully vaccinated, so the wiki survey did not yield input from unvaccinated groups. Our messages aimed to reach Philadelphia residents who had not been boosted or had their children vaccinated, but only 11% of our sample had not received a booster, 16.2% of those with children under 18 had not had their children at least partially vaccinated, and all participants contributed to the child vaccination wiki survey even though 63% did not have children under 18. Due to the platform limitations, messages designed to resemble social media posts (i.e., images and captions) based on the wiki survey results could not be tested. Finally, our findings cannot be generalized to other time periods given the changing landscape of COVID-19 outbreaks and vaccine recommendations. As new vaccines become available and COVID-19 variants emerge, messages will need to be re-tested using formative research methods like wiki surveys to ensure that they are appropriate and effective in the current context.

Wiki surveys could be applied to other formative research aims. For example, they could be implemented over extended periods of time to examine shifts in messaging strategies that are perceived as effective and the evolution of preferred messages instead of using multiple cross-sectional surveys. This is important because the type of messages that would be effective at changing behavior may change as the pandemic progresses. For example, those who chose to delay receiving the COVID-19 vaccines during the first few months of vaccine availability may have different beliefs and motivations influencing their health behaviors when compared to individuals who have remained unvaccinated for several years. Wiki surveys could also be used to compare different geographic locations or groups if the same user-generated messages were added to both pools. To address the limitation of the maximum message length that could be tested, new tools on Qualtrics, OpinionX, and other survey platforms could also be used to do A/B testing with images.

Wiki surveys are a feasible and efficient method for rapidly testing and obtaining audience feedback on short messages for social media campaigns. This study demonstrated how Philly CEAL used wiki surveys to develop social media campaign messaging to promote COVID-19 boosters and child vaccinations among Philadelphia residents. Participant-generated messages were perceived as more effective than messages seeded by the research team. These messages were incorporated into social media posts and shared through Philly CEAL’s X (formerly Twitter) and Facebook accounts. Future research should test the comparative effectiveness of higher versus lower ranked messages and participant- versus researcher-generated messages at increasing uptake of COVID-19 boosters and child vaccinations.

Methods

Sampling and recruitment

Participants in the present study were primarily recruited from respondents who had completed a previous study conducted by Philly CEAL. The study recruited Philadelphia residents ages 13 and older to complete an online survey through online and community-based outreach between September 2021 and February 2022. Responses were validated using a multi-step fraud detection protocol to enhance data integrity.

For the present study, e-mail invitations were sent between January and March 2023 to a randomly selected subset of verified respondents to the previous survey who had agreed to be recontacted for future studies (N = 493), Philly CEAL community partner organization representatives (N = 27), and VaxUpPhillyFamilies Ambassadors (N = 24) who engaged with local parents and caregivers to promote vaccination for children on social media and at in-person events. To be eligible for the wiki survey study, participants needed to be at least 18 years of age and currently living or working in the city of Philadelphia. We randomly sampled verified respondents of the previous survey and sent follow-ups to previously invited participants until we reached 200 completes. Because participants in previous wiki surveys had cast an average of 55 and 43 votes16, we estimated that 200 participants would result in 8600 to 11,000 votes per wiki survey. Of the 544 individuals invited, 264 (48.5%) started the screener, 256 (47.1%) were eligible (seven participants were ineligible because they did not work or live in Philadelphia and one was ineligible because they were under 18), 252 (46.3%) provided informed consent, 200 (36.8%) responded to all Qualtrics survey items, and 199 (36.6%) were verified to have completed the wiki surveys and included in the analysis.

Procedure

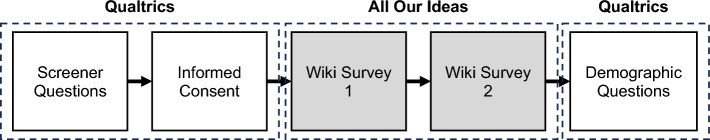

Figure 1 describes the protocol for this cross-sectional study and Appendix 1 includes the full questionnaire. Participants completed the screener and informed consent in Qualtrics, were directed to two wiki surveys hosted on All Our Ideas, and then returned to Qualtrics to complete demographic and COVID-19 vaccination status questions.

Fig. 1.

Survey workflow.

Email invitations included a unique link to a Qualtrics survey where participants first completed screener questions to assess eligibility (age, ZIP codes where they live and work). Eligible participants then provided informed consent and were randomized (using Qualtrics’ built-in randomizer function) to view either the booster or the child vaccination wiki survey first. For each wiki survey, participants were instructed to click a link that would open the appropriate wiki survey on the All Our Ideas website in a separate window, vote on messages for at least 3 min, and return to Qualtrics to continue the survey. Once the participant clicked the link, a three-minute countdown timer was displayed on the Qualtrics survey. Participants could not continue to the next screen until three minutes elapsed. To ensure that participants visited both wiki surveys, clicks on the wiki survey links were tracked using Qualtrics’ built-in click count variable and a JavaScript function that updated an embedded variable when the link was clicked on each instruction page.

On the All Our Ideas website, participants were presented with two messages randomly selected from a pool of messages and asked to rate the messages by selecting the message that they thought “would most encourage parents to get their child vaccinated against COVID-19” or “would most encourage someone to get the updated COVID-19 booster.” They could also select “can’t decide” or provide their own message (see Appendix 2). The initial pool included 11 messages for child vaccination and 9 messages for boosters based on the text obtained from Philly CEAL’s previous social media posts and contemporaneous social media toolkits from the NIH CEAL20. Three study team members (BZ, MK, GT) reviewed participant-submitted messages three times per week for appropriateness and grammar. Participant-submitted messages that were relevant to and not duplicative were added to the message rating pool. Recruitment was staggered so that there was approximately one week between each round of invitations to allow sufficient opportunity for participant-submitted messages to be added and voted on by subsequent participants.

After completing both wiki surveys, participants returned to Qualtrics and completed questions assessing demographic characteristics, COVID-19 vaccination status, and availability of COVID-19 information in respondents’ preferred language(s). Participants received a $10 gift card for completing the survey. The study was reviewed and approved by the University’s Institutional Review Board (protocol no. 848650). The research protocol was performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Measures

Demographics. In addition to providing their age in the screener, participants were asked to indicate their gender identity, sexuality identity, race, ethnicity, education, and whether they worked with a community-based organization that partnered with Philly CEAL.

COVID-19 vaccination status. Participants’ COVID-19 vaccination status was assessed using two items. The first item asked if participants had received the COVID-19 vaccine. Response options included “Yes, I am fully vaccinated (one dose of Johnson and Johnson or two doses of Moderna or Pfizer)”, “I am partially vaccinated (i.e., one dose of Moderna or Pfizer)”, and “No, I am not vaccinated against COVID-19.” Participants who were fully vaccinated were then asked if they had received one, two, three or more, or no boosters. Participants were also asked to indicate the ages of each of their children and whether each of their children under the age of 18 were fully, partially, or not vaccinated against COVID-19, if applicable.

Data analysis

Participant characteristics. Participants who completed the demographic and COVID-19 vaccination status measures at the end of the survey and were verified to have completed both wiki surveys were included in the descriptive analyses of participant characteristics (N = 199). Descriptive statistics for demographic characteristics and COVID-19 vaccination status were generated.

Message score. The All Our Ideas website collects data on every vote cast, including a unique respondent ID, a session ID, the two contending messages, and the resulting vote. All Our Ideas also provides aggregated statistics for each message summarizing the total number of votes; how many times the message won, lost, or resulted in a ‘can’t decide’ vote; and a message score15 that estimates the probability that the message would be chosen over a randomly selected competing message by a randomly selected participant. Scores range from 0 (the message is always expected to lose) to 100 (the message is always expected to win). The All Our Ideas website generates a message score using a two-step process. In the first step, an opinion matrix is generated that uses Bayesian inference to estimate how much each respondent values each message. Message values are imputed for participants who did not encounter the given message either because they did not encounter the message while casting votes or they could not have seen the message because it was participant-generated or they cast their votes prior to the message being added to the pool. This approach assumes that the votes reflect participants’ relative preferences for messages and that preferences for each item follow a normal distribution across respondents. The opinion matrix is then summarized to generate a message-level score for each item that estimates the probability of a message being chosen over a randomly selected message by a randomly selected participant. Because we cannot link votes to individual participants, all votes from all participants are included in the message score analysis regardless of whether they completed the study.

Financial

No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institutes of Health/CEAL (grant number 10T2HL161568). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Author contributions

B.Z.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Data curation, Writing—Original draft, Writing—Review & editing, Visualization, Project administration. A.L.: Writing—Original draft, Writing—Review & editing. G.T.: Investigation, Writing—Review & editing, Project administration. M.K.: Investigation, Writing—Review & editing, Project administration. K.G.: Writing—Review & editing. A.V.: Writing—Review & editing, Funding acquisition. J.B.: Writing—Review & editing, Funding acquisition. T.L.: Writing—Review & editing, Funding acquisition. S.B.: Writing—Review & editing. U.O.: Writing—Review & editing, Project administration. A.T.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing—Review & editing, Supervision, Project administration.

Data availability

Data are not available in a repository. Because we did not specify in the online consent that the data could be used for secondary data analyses, we are not able to make the data public. All message score data are available in the appendices. A restricted dataset including voting data, demographic characteristics, and vaccination status data may be requested from Brittany Zulkiewicz (brittany.zulkiewicz@asc.upenn.edu) and should include a plan for its use. Data may be made available to qualified researchers after the main findings are published in a peer-reviewed journal. All data sharing will comply with local, state, and federal laws and regulations and may be subject to appropriate human subjects institutional review board approvals.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-70554-9.

References

- 1.Noar, S. M. & Austin, L. (Mis)communicating about COVID-19: Insights from health and crisis communication. Health Commun.35, 1735–1739 (2020). 10.1080/10410236.2020.1838093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nan, X., Iles, I. A., Yang, B. & Ma, Z. Public health messaging during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond: Lessons from communication science. Health Commun.37, 1–19 (2022). 10.1080/10410236.2021.1994910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Viswanath, K., Lee, E. W. J. & Pinnamaneni, R. We need the lens of equity in COVID-19 communication. Health Commun.35, 1743–1746 (2020). 10.1080/10410236.2020.1837445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Noar, S. M. A 10-year retrospective of research in health mass media campaigns: Where do we go from here?. J. Health Commun.11, 21–42 (2006). 10.1080/10810730500461059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ball, H., Wozniak, T. R. & Kuchenbecker, C. M. Shot Talk: Development and pilot test of a theory of planned behavior campaign to combat college student COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. J. Health Commun.28, 82–90 (2023). 10.1080/10810730.2023.2183438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seitz, H. H., Gardner, A. J. & Pylate, L. B. P. Formative research to inform college health communication campaigns about COVID-19 prevention behaviors. Health Promot. Pract.25, 105–126 (2024). 10.1177/15248399231160768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bokemper, S. E., Huber, G. A., James, E. K., Gerber, A. S. & Omer, S. B. Testing persuasive messaging to encourage COVID-19 risk reduction. PLoS ONE17, e0264782 (2022). 10.1371/journal.pone.0264782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bokemper, S. E., Gerber, A. S., Omer, S. B. & Huber, G. A. Persuading US white evangelicals to vaccinate for COVID-19: Testing message effectiveness in fall 2020 and spring 2021. PNAS118, e2114762118 (2021). 10.1073/pnas.2114762118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mackert, M. et al. Applying best practices from health communication to support a university’s response to COVID-19. Health Commun35, 1750–1753 (2020). 10.1080/10410236.2020.1839204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID-19: What’s new and updated. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/whats-new-all.html.

- 11.Food & Drug Administration. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). https://www.fda.gov/emergency-preparedness-and-response/counterterrorism-and-emerging-threats/coronavirus-disease-2019-covid-19#new (2023). [PubMed]

- 12.Gaysynsky, A., Heley, K. & Chou, W.-Y.S. An overview of innovative approaches to support timely and agile health communication research and practice. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health19, 15073 (2022). 10.3390/ijerph192215073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bartels, S. M. et al. Development and application of an interdisciplinary rapid message testing model for COVID-19 in North Carolina. Public Health Rep.136, 413–420 (2021). 10.1177/00333549211018676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pattison, A. B. et al. Finding the facts in an infodemic: Framing effective COVID-19 messages to connect people to authoritative content. BMJ Glob. Health7, e007582 (2022). 10.1136/bmjgh-2021-007582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Salganik, M. J. & Levy, K. E. C. Wiki surveys: Open and quantifiable social data collection. PLoS ONE10, e0123483 (2015). 10.1371/journal.pone.0123483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Niederdeppe, J., Gundersen, D. A., Tan, A. S. L., McGinty, E. E. & Barry, C. L. Embedding a wiki platform within a traditional survey: A novel approach to assess perceived argument strength in communication research. Int. J. Commun.13, 1863–1889 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mensah, G. A. et al. Community engagement alliance (CEAL): A National Institutes of Health program to advance health equity. Am. J. Public Health114, S12–S17 (2024). 10.2105/AJPH.2023.307476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC Expands Updated COVID-19 Vaccines to Include Children Ages 6 Months Through 5 Years. https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2022/s1209-covid-vaccine.html (2022).

- 19.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC Recommends the First Updated COVID-19 Booster. https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2022/s0901-covid-19-booster.html (2022).

- 20.National Institutes of Health. Booster Q&A Social Media Toolkit. https://covid19community.nih.gov/booster-QandA-social-media-toolkit (2023).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are not available in a repository. Because we did not specify in the online consent that the data could be used for secondary data analyses, we are not able to make the data public. All message score data are available in the appendices. A restricted dataset including voting data, demographic characteristics, and vaccination status data may be requested from Brittany Zulkiewicz (brittany.zulkiewicz@asc.upenn.edu) and should include a plan for its use. Data may be made available to qualified researchers after the main findings are published in a peer-reviewed journal. All data sharing will comply with local, state, and federal laws and regulations and may be subject to appropriate human subjects institutional review board approvals.