Abstract

The Golgi compartment performs a number of crucial roles in the cell. However, the exact molecular mechanisms underlying these actions are not fully defined. Pathogenic mutations in genes encoding Golgi proteins may serve as an important source for expanding our knowledge. For instance, mutations in the gene encoding Transmembrane protein 165 (TMEM165) were discovered as a cause of a new type of congenital disorder of glycosylation (CDG). Comprehensive studies of TMEM165 in different model systems, including mammals, yeast, and fish uncovered the new realm of Mn2+ homeostasis regulation. TMEM165 was shown to act as a Ca2+/Mn2+:H+ antiporter in the medial- and trans-Golgi network, pumping the metal ions into the Golgi lumen and protons outside. Disruption of TMEM165 antiporter activity results in defects in N- and O-glycosylation of proteins and glycosylation of lipids. Impaired glycosylation of TMEM165-CDG arises from a lack of Mn2+ within the Golgi. Nevertheless, Mn2+ insufficiency in the Golgi is compensated by the activity of the ATPase SERCA2. TMEM165 turnover has also been found to be regulated by Mn2+ cytosolic concentration. Besides causing CDG, recent investigations have demonstrated the functional involvement of TMEM165 in several other pathologies including cancer and mental health disorders. This systematic review summarizes the available information on TMEM165 molecular structure, cellular function, and its roles in health and disease.

Keywords: CDG, glycosylation, Golgi, lysosomes, Mn2+, SERCA, SPCA1, TMEM

The Golgi apparatus, also known as the Golgi complex, Golgi body, or simply Golgi, is a cellular organelle present in almost all eukaryotic cells. Despite being one of the first organelles identified in the cell, more than 120 years ago (1, 2), the Golgi remains one of the less studied organelles. The most investigated role of Golgi is its involvement in the glycosylation of proteins and lipids, primarily because disruptions in these processes lead to congenital disorders of glycosylation (CDG) (3, 4, 5). However, the Golgi is responsible for various other tasks in the cell, including protein sorting, regulation of endosome/lysosome homeostasis, ATG7-independent macroautophagy, storage of metal ions (with Ca2+ being the most significant one), and compartmentalization of phospholipase signaling (6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14).

The exact regulation of Golgi functions has long been unclear, but in the past decade, attention has turned to a new protein that plays a pivotal role in Golgi homeostasis, namely, Transmembrane protein 165 (TMEM165). TMEM165 was initially identified as a new causative factor of CDG, but further research has revealed its unique role in regulating Ca2+ and Mn2+ homeostasis, pH regulation, and overall Golgi function. Additionally, its involvement in several diseases beyond CDGs has been proved, further highlighting the understudied role of the Golgi in cellular physiology and pathophysiology.

Evolution and structure of TMEM165

Structural insights

Transmembrane protein 165 (TMEM165) is a protein encoded by the human gene Tmem165, which belongs to the Ca2+:H+ Antiporter-2 (CaCA2) family (2.A.106. according to the Transporter Classification Database https://www.tcdb.org) (15). It was previously known as ‘Uncharacterized protein family 0016’ (UPF0016) (16, 17). In most eukaryotic organisms, only single members of this family are present per genome, whereas in plant species genomes multiple CaCA2 genes can be found (18, 19).

The CaCA2 family is part of the larger lysine exporter superfamily, which includes transporters specific for Ca2+, Mn2+, Ni/Co, Fe/Pb, amino acids, glycolipid peptides, tellurium, and transmembrane electron carriers (20). All these proteins share the same evolutionary history, originating from a duplication of an ancient ancestor gene that encoded 3 transmembrane domains (20). This feature is observed in all modern members of the CaCA2 family, which typically have 6 or 7 transmembrane domains and a total protein length between 200 and 350 amino acids (15). Six of these domains are highly conserved across different taxa. For example, comparisons of human, avian, fish, insect, and cyanobacterium orthologs of Tmem165 exhibited more than 60% homology in these domains (16). Similar results were obtained from comparisons of human Tmem165 with its orthologs in the nematode, yeast, cyanobacterium, and plants (e.g. Arabidopsis) (21). However, the seventh transmembrane domain varies considerably between species in terms of amino acid sequence and position (whether N-terminal or C-terminal) or may even be absent altogether. For instance, Gcr1-dependent translation factor 1 (Gdt1), the yeast ortholog of the human Tmem165 gene, contains 6 transmembrane domains. The heterologous expression of the full-length human Tmem165 gene, which encodes 7 transmembrane domains, did not restore viability in yeast lacking gdt1, whereas a truncated variant of the human Tmem165 gene lacking the seventh transmembrane domain fully rescued the phenotype (21, 22).

Consensus motif of TMEM165

Another feature of CaCA2 proteins is the highly conserved consensus pattern E-φ-G-D-(KR)-(TS) (where φ can be any hydrophobic residue) (23). Due to a duplication event in the evolutionary history of the CaCA2 family, each protein contains two such motifs. Computational modeling of the 3D conformation of the human TMEM165 protein revealed that these consensus motifs are located in the midpoint of transmembrane domains 2 and 5 (Fig. 1), forming a loop that faces the cytosolic side of the membrane (15). These motifs have been shown to be necessary for two main functions of TMEM165 discovered so far, i.e. Ca2+/Mn2+ transport and maintaining the Golgi's ability to implement glycosylation (24, 25). The 3D modeling of TMEM165 suggests that both copies of the consensus motifs together form an ion binding site in the form of an "acidic cage" (15), similar to structures shown to bind divalent cations in other proteins (26, 27, 28). Cytosolic loops connecting the transmembrane domains of TMEM165 contain two lysosomal targeting motifs. These motifs are recognized by adaptor proteins AP1–4, which can recruit clathrin to initiate the formation of coated vesicles (29).

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of TMEM165-CDG causing mutations and proposed mechanisms of TMEM165 deficiency. Human TMEM165 protein consists of 7 transmembrane domains (TMD). CaCA2 family signature consensus sequence E-φ-G-D-(KR)-(TS) is located in TMD2 and TMD5. This motif was demonstrated to be indispensable for the Ca2+/Mn2+:H+ antiporter activity of TMEM165. A lysosome targeting sequence YNRL is located at TMD3. Among patients with TMEM165-CDG 5 different disease-causing mutations were identified (marked in red on the figure). Point missense mutation [p.E108G] in TMD2 targets the CaCA2 family signature consensus motif disrupting the ability of TMEM165 to bind with Ca2+ and Mn2+. Two more-point missense mutations [p.R126H] and [p.R126C] are located in the lysosome targeting motif and plausibly hampers TMEM165 translocation to Golgi. Deletion mutation (c.792 + 182G > A) in TMD5 is causing the activation of a cryptic splice donor and the drastic decrease in mRNA expression of full-length TMEM165 protein. Finally, point missense mutation [p.G304R] in TMD7 indirectly affects the conformation of the Ca2+/Mn2+ binding site.

To date, no data are available on the transcriptional regulation of the Tmem165 gene nor on TMEM165 post-transcriptional modifications.

Alternative splicing variants of TMEM165

Evidence of an alternative splice variant of TMEM165 was found in human brain samples (30). One variant is 259 amino acids long and consists of 3 transmembrane domains, containing only one E-φ-G-D-(KR)-(TS) motif. The second splice variant is even shorter, with 129 amino acids and two domains, totally lacking the characteristic CaCA2 consensus motif (30). When overexpressed in HeLa cells, both splice variants show intracellular localization distinct from the canonical peptide. While the full-length TMEM165 resides in the Golgi (as discussed in detail below), both splice variants are localized in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). The expression of these splicing isoforms does not rescue the defect in glycosylation of Lysosome-Associated Membrane Protein 2 (LAMP2) in TMEM165 knockout cells, which is traditionally used to measure the severity of glycosylation deficiency. However, they partially ameliorated the glycosylation of Trans-Golgi network integral membrane protein 2 (TGOLN2, also known as TGN46) (30). No more data are available on the splicing variants of TMEM165, and their abundance and functional role remain quite obscure.

Molecular functions of TMEM165

TMEM165 as Ca2+ transporter

Evolutionary and computational predictions of TMEM165's function as a Ca2+ transporter were proven in experiments conducted both in yeast and mammalian cells. Saccharomyces cerevisiae (S. cerevisiae) deficient for Gdt1 (Tmem165 ortholog) exhibited a decreased viability in high Ca2+ conditions (21, 31). The effects of Gdt1 ablation were further exacerbated by the co-deficiency of the gene encoding plasma membrane ATPase-related 1 protein (pmr1) (yeast ortholog of the mammalian gene Ca2+-transporting ATPase type 2C member 1, Atp2c1) (21). Atp2c1 (also known as secretory pathway Ca2+-ATPase pump type 1, SPCA1) and Pmr1 encode a Golgi Ca2+/Mn2+ ATPase that pumps Ca2+ and Mn2+ into the Golgi lumen (32, 33). Thus, one may infer that both proteins play a similar role in Ca2+ clearance from the cytoplasm. Indeed, in yeast with double deficiency of Gdt1 and Pmr1, Ca2+ concentration in the cytoplasm was shown to be higher than in yeast lacking Pmr1 only (21). Additional confirmation came from experiments in which Gdt1 was expressed in the plasma membrane of the bacteria Lactococcus lactis (L. lactis). Direct measurement of intracellular Ca2+ demonstrated that GDT1 transports Ca2+ ions through the membrane (34). The heterologous expression of the human TMEM165 gene in S. cerevisiae was able to rescue the phenotype of double Gdt1/Pmr1 deficiency. Human TMEM165 protein expressed in L. lactis demonstrated the same ability to transport Ca2+ as GDT1 (22).

The ability of TMEM165 to clear Ca2+ from the cytoplasm has been also reported in mammalian cells; for instance, in HeLa cells overexpressing TMEM165, the increase in cytoplasmic Ca2+ upon treatment with thapsigargin (which releases Ca2+ from the ER) was lesser than in control cells (21). Targeted mutagenesis assays confirmed that the CaCA2 signature consensus motif E-φ-G-D-(KR)-(TS) plays an indispensable role in Ca2+ translocation through the membrane; in fact, the substitution of glutamate or aspartate in either of the two consensus motif sequences abrogates Ca2+ transport across the membrane (24).

TMEM165 as Mn2+ transporter

Some members of the CaCA2 family proteins possess Mn2+ translocation activity, including the TMEM165 orthologs manganese exporter A (MneA) and manganese oxidase (Mnx) in bacteria, and photosynthesis-affected mutant 71 (PAM71) and chloroplast manganese transporter 1 (CMT1) in plants (35, 36, 37, 38). TMEM165 also appears to translocate Mn2+.

Yeast strains deficient for the Golgi Ca2+/Mn2+ ATPase Pmr1 demonstrated reduced viability in high Mn2+ conditions, and Gdt1 co-deficiency exacerbated it (22, 39). Direct measurement of Mn2+ influx into L. lactis expressing GDT1 in the plasma membrane demonstrated the ability of the protein to translocate Mn2+ ions (39). However, the affinity of GDT1 for Ca2+ is 5 times higher than the one for Mn2+. The Km for Mn2+ is estimated to be 83.2 ± 9.8 μM, whereas for Ca2+ is 15.6 ± 2.6 μM (39). The heterologous expression of the human TMEM165 gene in S. cerevisiae was able to rescue high Mn2+-induced growth defect in yeast with co-deficiency of Gdt1/Pmr1, proving that human TMEM165 also possesses Mn2+ translocation activity (22). The heterologous expression of human TMEM165 in the membrane of L. lactis additionally confirmed this aspect (22). Importantly, targeted mutagenesis experiments demonstrated that the same amino acid in the consensus motif of the CaCA2 family was responsible for both Mn2+ and Ca2+ ion translocation (22).

The function of TMEM165 as a Mn2+ transporter was also documented in mammalian cells. In HeLa cells, TMEM165 knockout did not affect Mn2+ levels in the cytoplasm but significantly decreased Mn2+ concentrations in organelles, further proving the role of TMEM165 as a Mn2+ Golgi transporter. TMEM165 knockout also retarded Mn2+ clearance from cells subjected to long exposure to high Mn2+ concentration (40).

Indirect evidence for TMEM165 Ca2+/Mn2+ transporter activity in the Golgi has been provided by in vivo assays. The majority of Ca2+ and Mn2+ content in milk derive from secretory vesicles dispatched from the Golgi compartment (41, 42, 43); the targeted deletion of Tmem165 in murine mammary glands resulted in diminished concentrations of both Ca2+ and Mn2+ in milk with no changes in other divalent cations (44).

TMEM165 as Ca2+/Mn2+:H+ antiporter

TMEM165-mediated Ca2+ and Mn2+ translocation activity was discovered to be coupled with the translocation of H+ in the opposite direction, making TMEM165 a Ca2+/Mn2+:H+ exchanger. This feature of TMEM165 was extensively studied by Pierre Morsomme’s group (45). They expressed Gdt1 in the plasma membrane of L. lactis and measured pH, Ca2+, and Mn2+ concentrations. The rate of Ca2+ and Mn2+ translocation through the membrane appeared to be dependent on the pH level. The rate of cation transport increased together with the extracellular pH level. Conversely, the addition of extracellular Ca2+ or Mn2+ resulted in acidification of the extracellular media, showing that Ca2+ and Mn2+ translocation is inevitably coupled with H+ exchange (45). In yeast cells, deletion of Gdt1 under normal conditions did not affect either cytoplasmic or Golgi pH levels, seemingly because of the robust function of vacuolar membrane ATPase. However, during glucose deprivation, the cytoplasmic pH of S. cerevisiae was lower in Gdt1-deficient cells (45). A realistic explanation is that upon ATP depletion, the direction of ion transport by TMEM165 is reversed to maintain a physiological pH within the Golgi. This mechanism is supported by similar data obtained in another independent study (31).

Role of TMEM165 in cell function

Tissue specificity of TMEM165

According to the Human Protein Atlas project, the Tmem165 gene demonstrates ubiquitous expression throughout the organism with very low tissue specificity (46, 47). TMEM165 mRNA levels are relatively low, and on the protein level, no tissue specificity has been found for TMEM165 either. Among 30 different tissues tested by single-cell RNA sequencing by the Human Protein Atlas (48), a specificity for TMEM165 was only detected in the brain, where it was highly expressed in two clusters related to oligodendrocytes. In the other 29 tissues, TMEM165 showed no specificity for any cell type.

Cell compartmentalization of TMEM165

Several studies have shown that at the cellular level, TMEM165 localizes to the Golgi. The Golgi apparatus represents a series of flat membrane-enclosed disks known as cisternae, building up a stack. A stack is broken down into cis-, medial-, and the trans-Golgi network in which different steps of protein glycosylation are carried out (49). Testing the colocalization of Gdt1 with different Golgi enzymes revealed that the protein resides in the cis- and medial-Golgi, but not in the trans-Golgi (21). In human fibroblasts, TMEM165 colocalized with both markers of cis- and trans-Golgi (16). However, upon dispersion of the Golgi structure with the help of the microtubule polymerization inhibitor nocodazole, TMEM165 maintained colocalization only with beta-1,4-galactosyltransferase, a trans-Golgi enzyme (16). This finding could be explained by the better resolution of Golgi compartments after nocodazole treatment, or it may indicate that TMEM165's Golgi retention mechanism is based on its retrograde transport, possibly explaining the Golgi localization of TMEM165 despite the absence of the ER-targeting sequence KDEL/HDEL (50, 51). Several lines of evidence support the idea of a retrograde transport of TMEM165 through the Golgi network. TMEM165 contains the lysosomal-targeting sequence YNRL (belonging to the classical YXXØ lysosomal-targeting signal) (52). Au fait, TMEM165 displayed colocalization with lysosomes/late endosomes and the plasma membrane, although to a lesser extent than with the Golgi (52, 53, 54). Finally, several TMEM165-CDG-causing mutations have been proven to decrease TMEM165 accumulation in Golgi but increase TMEM165 abundance in lysosomes, inferring the disruption of lysosome-to-Golgi transport of TMEM165 (52).

Glycosylation defects caused by TMEM165-CDG

TMEM165 is necessary for accomplishing glycosylation in the Golgi. Mutations in the TMEM165 gene cause type II CDG. At the cellular level, TMEM165-CDG is characterized by defective N-glycosylation; a relative increase in undersialylated and undergalactosylated glycans has been reported, pointing to a defect in both sialylation and galactosylation (16, 55, 56). Sialylation is performed in the trans-Golgi and most often is attached to galactose, while galactosylation precedes sialylation and occurs in the medial-Golgi (57, 58). Taken together, these observations suggest that TMEM165 deficiency most likely impairs enzyme(s) of the medial- and trans-Golgi. TMEM165-CDG has also been associated with more abundant fucosylated and high-mannose type N-glycans, denoting a decrease in N-glycan maturation (59).

Defective O-glycosylation has been detected in patients with TMEM165-CDG: It is characterized by a decrease in the monosialo- and an increase in the asialo-forms of Apolipoprotein C-III (16). Another evidence of defective O-glycosylation is the shifted ratio between nT-antigen (Galβ1-3GalNAc-α-Ser/Thr) and ST-antigen (NeuAcα2-3Galβ1-3GalNAc-α-Ser/Thr) (55).

TMEM165 deficiency also affects the glycosylation of lipids. Whereas normal cells show complex patterns of different gangliosides, TMEM165 knockout cells lack almost all of them, containing only trace amounts of GM2 and GM3 (60).

TMEM165 mutations causing glycosylation defects

Mutations of the TMEM165 gene provide important insight into TMEM165 cell functions (Fig. 1). Hitherto, 6 patients with TMEM165-CDG were described bearing 5 different mutations. One mutation (c.792 + 182G > A) causes the activation of a cryptic splice donor and the production of both full-size and truncated proteins (16). However, mRNA expression of full-length TMEM165 is drastically decreased in patients with this mutation, resulting in almost undetectable levels of mature protein (16, 52), attesting that the presence of TMEM165 itself is essential for a normal Golgi function.

The other 4 mutations provide more clues on the connection between the molecular function of TMEM165 and Golgi function. All these alterations represent point missense mutations resulting in a substitution of amino acid residues: i) [p.Arg126His] ii) [p.Arg126Cys] iii) [p.Gly304Arg] iv) [p.Glu108Gly] (16, 61). These mutations result in lower TMEM165 protein content compared to healthy controls (16, 52). However, the severity of glycosylation defects in cells from patients with a moderate decrease in TMEM165 abundance does not seem to be significantly different from patients with a virtual loss of TMEM165 protein (16).

Of these point mutations, two (i, ii) affect the lysosome targeting motif, one (iii) is located in the transmembrane domain of TMEM165 and does not target the motif with an established functional role, and one (iv) targets the signature consensus motif of CaCA2 proteins. Mutations affecting the lysosome targeting motif result in the retention of TMEM165 in the lysosome. Upon expression of the normal TMEM165 gene in HeLa cells, approximately 50% of the protein colocalizes with lysosomes and 50% with the trans-Golgi. Expression of [p.Arg126His] and [p.Arg126Cys] TMEM165 shifts this ratio to 70 to 80% of TMEM165 located in the lysosomes and the rest in the trans-Golgi (52). Thus, functionally, the point mutations [p.Arg126His] and [p.Arg126Cys] exert similar effects as (c.792 + 182G > A): the latter deprives the Golgi of TMEM165 by a global decrease in its abundance, whereas the first two achieve the same goal by hampering protein transport. These data also show that the TMEM165-CDG phenotype is caused by TMEM165 deficiency disrupting Golgi function, and not other compartments.

The pathogenic mechanism of point mutations [p.Glu108Gly] and [p.Gly304Arg] is related to the direct disruption of TMEM165 molecular function and not to its abundance or localization. The expression of [p.Gly304Arg] TMEM165 in HeLa cells did not result in its retention in lysosomes; on the contrary, it even increased TMEM165 targeting to the trans-Golgi (52). Mutation [p.Glu108Gly] directly affects the consensus motif 108E-φ-G-D-(KR)-(TS)113, substituting the glutamic acid (E108) thereby disrupting the structure of the "acidic cage" ion binding site (15). Computational prediction of TMEM165 conformations demonstrated that the [p.Gly304Arg] mutation also affects the structure of the "acidic cage" formed by the 108E-φ-G-D-(KR)-(TS)113 motif. When glycine is located in position 304, it does not interact with the consensus motif. However, the long side chain of arginine spans between the transmembrane domains 2 and 7 and interferes with the conformation of the 108E-φ-G-D-(KR)-(TS)113 motif. Modeling studies predicted that histidine or lysine in position 304 would not affect the "acidic cage" structure; indeed, the expression of TMEM165 with [p.Gly304His] or [p.Gly304Lys] rescued glycosylation deficiency in TMEM165 knockout cells (15).

Role of Mn2+ homeostasis in glycosylation defects caused by TMEM165 deficiency

One of the most plausible mechanisms by which TMEM165 deficiency causes glycosylation defects is a scarcity of Mn2+ content within the Golgi. This hypothesis is corroborated by several layers of evidence.

The first insight comes from the fact that mutations targeting CaCA2 family consensus motif and disrupting “acidic cage” recognizing Mn2+ and Ca2+ ions cause glycosylation defects (15, 62). At the same time, these mutations do not preclude TMEM165 localization to the Golgi (52). Thus, the ability to implement Ca2+ or/and Mn2+ transport is indispensable for the function of glycosylation enzymes in the Golgi.

The second and most compelling evidence is the rescue of glycosylation deficiency caused by either a pathogenic mutation in TMEM165 or TMEM165 knockout by Mn2+ supplementation (34, 40, 53, 60, 63). Moreover, the effect is dose-dependent: higher concentrations of supplemented Mn2+ are associated with lower electrophoretic motility of glycosylated proteins (56, 63). MnSO4 is as effective in rescuing glycosylation in TMEM165 knockout cells as MnCl2, which was used in other studies (60). Importantly, Ca2+ supplementation in Gdt1/Pmr1 double-deficient yeast did not rescue the glycosylation effects (56). Disruption of the “acidic cage” structure impairs the ability of TMEM165 to transfer Ca2+ ions through the membrane as well as Mn2+ ions (22, 24); however, failure to rescue the glycosylation defect with Ca2+ supplementation strongly suggests that TMEM165-CDG is related to disturbed Mn2+ Golgi homeostasis.

The third argument in support of this hypothesis is that mutations in solute-carrier 39 A 8 (SLC39A8) are also known as a causative factor of CDG (64, 65). This gene encodes a plasma membrane transporter for bivalent ions, including Mn2+ (29, 66). Its deficiency reduces Mn2+ import into the cell, and may also result in depletion of Golgi Mn2+ content (67, 68). Finally, a number of enzymes involved in glycosylation use Mn2+ as a cofactor, mechanistically explaining why a decrease in Golgi Mn2+ disrupts glycosylation (69).

The knockout of another Golgi Mn2+ transporter, namely ATP2C1 (encoding SPCA1) did not abolish the effect of Mn2+ supplementation (70). Inhibition of endocytosis also had no effect, showing that retrograde flow of Mn2+ is not able to overcome the Mn2+ deficit caused by TMEM165 knockout (70). Surprisingly, the capacity of Mn2+ to rescue TMEM165 knockout-induced glycosylation defects has been shown to be dependent on sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase 2 (SERCA2, encoded by ATP2A2 gene). Its inhibition via thapsigargin totally abolishes Mn2+ effect, and ATP2A2 overexpression partially replicates the effect of Mn2+ supplementation (53, 70). These data imply that the rescue of TMEM165 knockout defect in glycosylation requires anterograde entrance of Mn2+ into Golgi, which could be mediated by SERCA2b; this pump possesses Mn2+ translocation activity but has much less affinity to Mn2+ compared to Ca2+ (71, 72, 73). An obstacle to this mechanistic explanation could be the fact that high Mn2+ concentrations inhibit SERCA2b (72). Nonetheless, the inhibition was observed with a concentration of Mn2+ that was ∼10 to 100 times higher than the concentrations of Mn2+ required for the rescue of the TMEM165 knockout phenotype.

Role of pH in glycosylation defects caused by TMEM165 deficiency

A competing explanation of the pathophysiology of TMEM165-CDG implies the disruption of Golgi pH due to TMEM165 deficiency. TMEM165 acts as a Ca2+/Mn2+:H+ antiporter, regulating both cell and Golgi pH (45); pH levels are decisive for determining the correct conformation of proteins, affecting the function of enzyme active centers and the availability of glycosylation sites in proteins that require modification. Additionally, different compartments of the Golgi have different acidity levels, which are needed for specific functions (74, 75, 76, 77). Mutations in genes encoding subunits of V-ATPase, the main protein regulating Golgi pH, are known to cause severe CDGs (78, 79, 80, 81). However, despite the possibility of alterations in Golgi pH in TMEM165-CDG, the ability of Mn2+ supplementation to rescue glycosylation defects in TMEM165 knockout cells (40, 53, 60, 63) makes the "Mn2+ hypothesis" more favorable than the "pH hypothesis".

Galactose supplementation rescues glycosylation defects caused by TMEM165 deficiency

The elusive aspect of TMEM165-CDG phenotype may relate to the ability of D-galactose supplementation to rescue glycosylation defects (53, 60, 63). Other monosaccharides were found to be ineffective (53, 60). Importantly, unlike the Mn2+ treatment, D-galactose failed to rescue O-glycosylation and restore ganglioside levels, being effective only in restoring the normal pattern of N-glycosylation (53, 60). Even in N-glycosylation, galactose supplementation demonstrated a lower efficacy compared to Mn2+. This aspect was evident in both a lower ratio of under-glycosylated to fully-glycosylated forms of proteins and a longer time required to achieve a beneficial effect in vitro (53, 60). Remarkably, the combination of galactose and Mn2+ supplementations has a synergistic effect. Furthermore, the combination of galactose and Mn2+ allows overcoming the inhibitory effect of thapsigargin, denoting how the galactose-mediated rescue of N-glycosylation is dependent on Mn2+ but not on the entry of these cations via SERCA2b (53). D-galactose has been previously proposed as an effective therapeutic strategy in CDGs of different etiologies, rescuing glycosylation defects caused by both Mn2+ deficit (SLC39A8-CDG) and uridine diphosphate (UDP)-Galactose deficiency (PGM1-CDG and SLC35A2-CDG) (82, 83, 84). The fact that many galactosyltransferases require Mn2+ as a cofactor makes the beneficial effect of galactose supplementation in TMEM165-CDG and SLC39A8-CDG even more enthralling (67, 69, 85, 86).

TMEM165 degradation by Mn2+

The intimate connection between TMEM165 and Mn2+ involves not only the regulation of Mn2+ but also the control of TMEM165 levels by Mn2+ (Fig. 2). When cells are exposed to high Mn2+ levels, TMEM165 abundance decreases both in the whole cell lysate and in the Golgi compartment (62). Interestingly, the Mn2+ treatment does not seem to affect the expression levels of other Golgi proteins, showing a specific effect on TMEM165 (56, 62). Mn2+ supplementation causes TMEM165 to move to the lysosomes for degradation (62), such translocation to lysosomes and degradation of TMEM165 is observed when cells are treated with lysosome inhibitors, such as chloroquine and leupeptin (62).

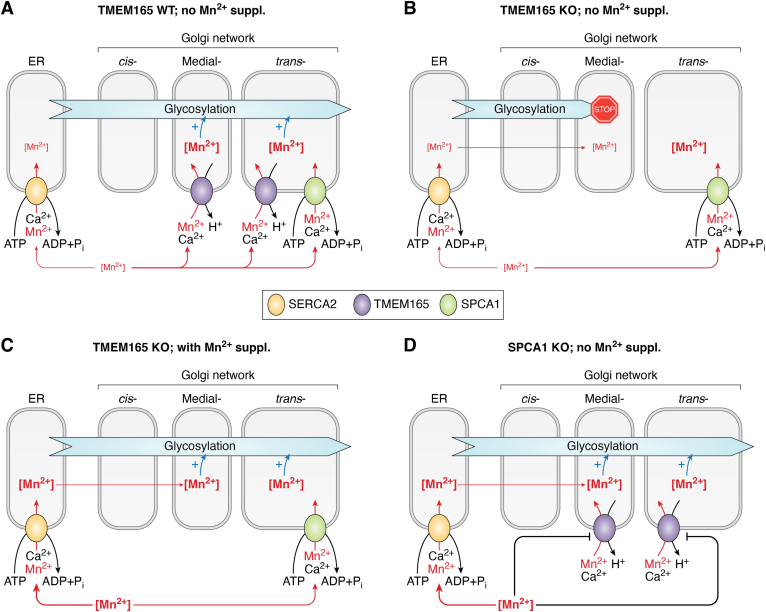

Figure 2.

Model of Golgi-ER regulation of Mn2+homeostasis.A, Under normal conditions, medial-Golgi is predominantly supplied with Mn2+ by TMEM165 and trans-Golgi by TMEM165 and SPCA1. Mn2+ import by SERCA2 is negligible. B, in the case of TMEM165 deficiency, medial-Golgi is deprived of Mn2+ halting the function of Mn2+-dependent glycosylation enzymes. This event is attributable to the low abundance of SPCA1 in medial-Golgi and the absence of retrograde Mn2+ flow from trans-Golgi to medial-Golgi. Most likely, the Mn2+ content in trans-Golgi is also decreased due to the absence of TMEM165 activity. Despite its ability to transport Mn2+, SERCA2 is not able to rescue the medial-Golgi Mn2+ insufficiency due to the low affinity to Mn2+; the high affinity of SPCA1 for Mn2+ eventually results in pumping all available Mn2+ into the trans-Golgi. C, with excessive Mn2+ supplementation, the SPCA1 Mn2+ translocation activity becomes saturated, giving the opportunity to SERCA2 to start pumping Mn2+ into the ER and potentially into the cis-Golgi. The anterograde flow of Mn2+ through the Golgi network supplies essential cofactors to the glycosylation enzymes and hence rescues the TMEM165-deficiency phenotype. D, SPCA1 deficiency results in massive Mn2+ accumulation in the cytosol. This phenomenon is firstly due to the loss of Mn2+ translocation into the Golgi lumen by SPCA1 per se. The increased concentration of cytoplasmic Mn2+ triggers TMEM165 degradation; thus, SPCA1 deficiency further augments the Mn2+ cytoplasmic level. A high concentration of Mn2+ allows SERCA2 to pump Mn2+ into the ER and subsequentially the Golgi, thereby preventing the disruption of the glycosylation processes.

The rate of TMEM165 clearance strictly depends on Mn2+ concentration, with higher Mn2+ concentrations leading to faster degradation (62). No other divalent cations, including Mg2+, Ca2+, Cu2+, Zn2+, Co2+, had the same effect, indicating the specificity of TMEM165 for Mn2+ (62). Various studies suggest that the degradation of TMEM165 requires specific recognition of Mn2+ by the CaCA2 family consensus motif E-φ-G-D-(KR)-(TS). Skin fibroblasts from TMEM165-CDG patients harboring the [p.Glu108Gly] mutation exhibited a modest TMEM165 clearance under high Mn2+ conditions; in contrast, cells from patients with [p.Arg126His/Cys] mutations displayed TMEM165 degradation, though still slower than healthy donor cells (62). As mentioned earlier, replacing Glu108 disrupts the "acidic cage" of the E-φ-G-D-(KR)-(TS) motif, which is critical for binding Mn2+ and Ca2+. On the other hand, substituting Arg126 reduces the retention of TMEM165 in the Golgi. Yet, when cells are treated with high concentrations of both Mn2+ and Ca2+, the degradation of TMEM165 is significantly slowed down (62). These observations also suggest that TMEM165 translocation from Golgi to lysosomes requires binding of Mn2+ to the CaCA2 signature motif, as this motif is also responsible for binding Ca2+ ions. Since TMEM165 has a higher affinity for Ca2+, the inhibitory effect of Ca2+ on Mn2+-induced degradation of the protein may be attributable to competition for the same active site.

Experimental data strongly suggest that TMEM165 degradation is triggered by Mn2+ binding to the protein from the cytoplasmic side, as deduced from the fact that ATP2C1 knockout or loss-of-function mutations in ATP2C1 induce TMEM165 degradation (40, 62, 87, 88). SPCA1 encoded by the ATP2C1 gene imports Mn2+ into the Golgi and its deficiency robustly augments Mn2+ concentration in the cytosol (40). Moreover, upon SPACA1 deficiency, downregulation of TMEM165 is also caused by its translocation to lysosomes, as in high Mn2+ treatment (87, 88). Additional support for this hypothesis may come from the fact that the overexpression of ATP2A2 partially rescues TMEM165 expression in SPCA1-deficient cells (87). If SERCA2b re-supplies the Golgi with Mn2+, then its overexpression should decrease cytoplasmic Mn2+ concentration in the absence of SPCA1.

Interestingly, the rescue of glycosylation deficit caused by TMEM165 ablation is achieved already at a concentration of 1 μM of MnCl2 (56), whereas a robust downregulation is observed at 25 μM (62). One might infer that a potential biological role of Mn2+-induced TMEM165 degradation is to preclude Golgi overload with Mn2+. However, in pathological conditions like Hailey-Hailey disease, caused by dysfunction of SPCA1, this mechanism becomes detrimental (32, 88).

Signaling effects of TMEM165-deficiency

TMEM165 deficiency has been shown to affect signaling pathways mediated by Transforming growth factor beta (TGFβ) and Bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) (89). In the chondrogenic cell line ATDC5, Tmem165 deletion results in lower levels of phosphorylation of Mothers against decapentaplegic homolog (SMAD) 2 and higher levels of phosphorylation of SMAD1,5,9; similar alterations have been detected in fibroblasts isolated from patients with TMEM165-CDG (89). SMAD2 and SMAD1,5,9 are key mediators of TGFβ and BMP signaling, respectively (90). The expression of Tgfβ is drastically reduced in Tmem165−/− cells; the expression of the TGFβ target gene Serpine1 is also reduced, proving the loss of TGFβ signaling (89). In addition to reduced Tgfβ expression, Tmem165−/− cells also have reduced levels of TGFR2 and higher expression of Asporin, which blocks the interaction of TGFβ with its receptors. However, the downregulation of Tgfβ expression is most likely to be the main cause of TGFβ signaling loss, as Tmem165−/− cells are still able to respond to exogenous TGFβ stimulation (89).

Tmem165−/− cells display an increased expression of BMP and two of its receptors (namely BMPR1b and BMPR2); in addition, the expression of a negative regulator of BMP signaling – Noggin – is decreased (89). Treatment of control cells with MnCl2 has the same effects as Tmem165 ablation, i.e. stimulation of BMP signaling and downregulation of TGFβ signaling (89).

It is important to note that the loss of Ca2+ pumping activity due to TMEM165 deficiency most likely induces Ca2+-mediated signaling. The data on these phenomena are scarce; however, an increased phosphorylation of Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase type II (CaMKII) has been reported in Tmem165−/− cells (89).

Role of TMEM165 in lysosomal function

Intriguingly, in a recent study conducted on Caenorhabditis elegans, Zajac and collaborators identified a conserved gene, lci-1, which represents the worm counterpart of the human TMEM165, showing its involvement in enabling lysosomal Ca2+ entry in a pH-dependent manner (54). Through two-ion mapping and electrophysiology, TMEM165 was shown to function as a proton-activated lysosomal Ca2+ importer (54). These data were substantiated by the measurement of lysosome pH in fibroblasts from healthy donors and patients harboring mutations in TMEM165. The majority of the fibroblast batches, isolated from different TMEM165-CDG patients, had a lower lysosomal pH alongside an increased number of lysosomes (28). Moreover, silencing TMEM165 expression in HeLa cells resulted in acidification of the lysosomal compartment (28).

These findings are captivating, especially considering that, as discussed above, TMEM165 abundance in lysosomes is relatively low compared to its levels within the Golgi. Since defects in lysosomal Ca2+ channels are linked to several neurodegenerative diseases (91), understanding lysosomal Ca2+ importers could offer new insights into the physiology of Ca2+ channels.

Role of TMEM165 in health and disease

TMEM165 and lactation

TMEM165 plays a fundamental role in lactation by regulating the levels of Mn2+ and Ca2+ in milk. Its expression peaks during lactation (Tmem165 expression was found to be ∼25 times greater during peak lactation compared to early pregnancy) and declines rapidly after the lactation period ends (92). In mice lacking TMEM165, milk composition is altered, with lower levels of lactose and higher levels of calcium, iron, zinc, fat, and total protein (44). The effects of the quality of the milk were also observed in the pups of the lactating mice, where pups nursed by Tmem165 knockout mothers had significantly lower weights. Since TMEM165 acts as a Ca2+/Mn2+:H+ antiporter, its deficiency results in the accumulation of H+ ions, reducing lactose synthesis and osmosis-mediated dilution of milk. This study emphasizes the importance of TMEM165 in milk production and provides insights into its cellular functions.

Clinical manifestations of TMEM165-CDG

Glycosylation plays a vital role in the functioning and stability of proteins in various cellular processes. Defects in genes responsible for glycosylation lead to many pathological manifestations. Mutations in several genes cause CDGs, with mutations in the Phosphomannomutase 2 (PMM2) gene being the most prevalent (93). CDGs are classified as type I or type II, where type I is associated with a defect in the assembly or transfer to the peptide chain, and type II is associated with processing or remodeling. TMEM165 initially caught attention as a culprit in one of the CDGs (16, 52, 59). TMEM165-CDG falls into type II, accounting for approximately 8% of CDG-II patients, and is inherited in an autosomal recessive manner (16, 93).

Clinical manifestations of TMEM165-CDG vary across different systems in the body. Patients typically exhibit psychomotor and growth retardation, facial dysmorphism, skeletal anomalies, hepato-splenomegaly, muscular hypotrophy, feeding problems, and abnormal fat distributions (16, 59). Skeletal anomalies are prominent, possibly due to the role of glycosylation in extracellular matrix proteins and bone metabolism. TMEM165 deficiency may also affect chondrocyte maturation and hypertrophy, contributing to skeletal issues (59, 89). Other symptoms include strabismus, ptosis, white matter abnormalities, pituitary gland hypoplasia, fever episodes, transient epilepsy, cardiovascular defects, restrictive lung pathology, and renal failure (16, 59, 61).

Various therapeutic approaches for TMEM165-CDG have been explored. Mn2+ supplementation helps suppress glycosylation defects by restoring Golgi Mn2+ homeostasis (62). D-galactose supplementation has similar effects, improving glycan structures and patient well-being (60). Genetic therapies, including mutation-specific antisense therapy, hold promise for restoring normal TMEM165 protein levels (94).

Toward in vivo models of TMEM165-CDG

In order to understand TMEM165-CDG consequences, researchers have developed animal models with manipulated TMEM165 expression. For instance, Danio rerio (zebrafish) has been utilized to study the effects of TMEM165 deficiency on skeletal abnormalities and biochemical disturbances (95). Early research in yeast demonstrated abnormalities in the glycosylation processes due to a deficiency in a yeast ortholog of TMEM165 (56). Zebrafish, harboring a TMEM165 protein that is 79% identical to the human one, has been explored as a potential model. Injection of antisense morpholinos into zebrafish embryos inhibited Tmem165 expression. Similar to yeast, Tmem165-deficient zebrafish exhibited glycosylation defects with decreased N-linked glycan abundance (95). Additionally, morphant zebrafish displayed abnormal cartilage development with craniofacial defects and increased chondrocyte differentiation markers along with decreased osteoblast maturation factors (95). These findings mirrored results in mouse ATDC5 cells and human HEK293 cells, where TMEM165 knockout induced early chondrogenic differentiation and mineralization, somehow elucidating the skeletal abnormalities (89).

TMEM165 and cancer

In addition to CDGs, TMEM165 has been linked to other human diseases, particularly cancer. Overexpression of TMEM165 has been observed in various types of cancers. For example, breast cancer cells show higher TMEM165 levels compared to normal cells, and increased TMEM165 expression correlates with worse outcomes in breast cancer patients (96). Similarly, in hepatocellular carcinoma, TMEM165 is overexpressed in cancer cells, promoting invasive activity (97). These observations suggest that TMEM165 could serve as a biomarker and therapeutic target for breast cancer and hepatocellular carcinoma.

In murine models, TMEM165 overexpression was associated with increased invasive activity in certain types of cancer (97). To further investigate these phenomena, mouse xenograft models were used to test the effects of TMEM165 knockout in breast cancer tumors (96). Similar to the changes in N-glycosylation observed in zebrafish, mice injected with Tmem165 knockout cells exhibit reduced tumor growth and vascularization, alongside decreased vimentin and increased E-cadherin levels within the tumors. These findings indicate that TMEM165 may play a role in enhancing cancer invasion capabilities.

TMEM165 and other human diseases

Single-nucleotide polymorphisms in the Tmem165 gene have been associated with mood disorders. Specifically, a polymorphism in the TMEM165 gene, rs534654, has been linked to an increased risk of bipolar disorder type 1 (98). This polymorphism is located near the Circadian Locomotor Output Cycles Protein Kaput (Clock) gene, which is a circadian gene. Circadian genes have previously been associated with an increased risk of mood disorders, which may explain the connection between this Tmem165 polymorphism and bipolar disorder (98). On the other hand, there seems to be a negative correlation between Tmem165 and autistic spectrum disorder (ASD): serum extracellular vesicles (EVs) obtained from ASD children aged 3.5 years were found to express TMEM165 mRNA in significantly lower levels compared to controls (99); several other genes involved in the glycosylation process were also downregulated in ASD (99). Decreased levels of TMEM165 seem to be part of a general glycosylation disturbance in these patients, rather than being the causative factor.

Most recently, the overexpression of TMEM165 protein was also detected in the saliva of COVID-19 patients with an active infection, along with other molecular alterations. This finding sheds light on potential mechanisms by which the disease can disrupt cellular processes and metabolism (100).

Conclusion

Fine-tuning TMEM165 activity may contribute to maintaining cellular Ca2+ and Mn2+ homeostasis. While there have been some preclinical investigations on TMEM165 using experimental animal models, research in this area remains limited. Historically, studies of TMEM165 have focused on understanding TMEM165-CDG mechanisms and their role in glycosylation, primarily using in vitro approaches. However, recent findings on the involvement of TMEM165 in cancers and the association of specific polymorphisms with mental health disorders strongly suggest that alterations in TMEM165 expression could play significant, tissue-specific, roles in various pathologies. Another unexplored aspect is the post-translational modification of TMEM165.

Data availability

All data generated in this study are provided in the article and its supplementary materials.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests:

Dr Santulli is an Editorial Board Member for JBC and was not involved in the editorial review or the decision to publish this article. The other authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions

G. S. project administration; S. S. J., G. S., and J. G. conceptualization; F. V., J. G., and G. A. T. visualization; F. V., G. S., E. D. A., J. G., U. K., and G. A. T. validation; F. V. and S. S. J. investigation; S. S. J. and E. D. A. methodology; S. S. J., G. S., J. G., and U.K. data curation; S. S. J. writing–original draft; G. S. writing–review & editing; G. S. and U. K. resources; G. S. funding acquisition.

Funding and additional information

The Santulli’s Lab is currently supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (NIH): National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK: R01-DK123259, R01-DK033823), National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI: R01-HL164772, R01-HL159062, R01-HL146691, T32-HL144456, T32-HL172255), National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS: UL1-TR002556-06, UM1-TR004400) to G. S., by the American Heart Association (AHA, 24IPA1268813), by the Diabetes Action Research and Education Foundation (to G. S.), and by the Monique Weill-Caulier and Irma T. Hirschl Trusts (to G. S.). S. S. J. is supported in part by a postdoctoral fellowship of the AHA (21POST836407). F.V. is supported in part by the AHA (22POST915561 and 24POST1195524). U.K. is supported in part by a postdoctoral fellowship of the AHA (23POST1026190). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or the AHA.

Reviewed by members of the JBC Editorial Board. Edited by George DeMartino

References

- 1.Golgi C. The impossible interview with the man of the hidden biological structures. Interview by Paolo Mazzarello. J. Hist. Neurosci. 2006;15:318–325. doi: 10.1080/09647040600653964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Golgi C. On the structure of nerve cells. 1898. J. Microsc. 1989;155:3–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2818.1989.tb04294.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilson M.P., Matthijs G. The evolving genetic landscape of congenital disorders of glycosylation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 2021;1865 doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2021.129976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chatham J.C., Zhang J., Wende A.R. Role of O-linked N-Acetylglucosamine protein modification in cellular (Patho)Physiology. Physiol. Rev. 2021;101:427–493. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00043.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Durin Z., Raynor A., Fenaille F., Cholet S., Vuillaumier-Barrot S., Alili J.M., et al. Efficacy of oral manganese and D-galactose therapy in a patient bearing a novel TMEM165 variant. Transl Res. 2024;266:57–67. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2023.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rohn W.M., Rouille Y., Waguri S., Hoflack B. Bi-directional trafficking between the trans-Golgi network and the endosomal/lysosomal system. J. Cell Sci. 2000;113:2093–2101. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.12.2093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Braulke T., Bonifacino J.S. Sorting of lysosomal proteins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2009;1793:605–614. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feng H., Wang N., Zhang N., Liao H.H. Alternative autophagy: mechanisms and roles in different diseases. Cell Commun. Signal. 2022;20:43. doi: 10.1186/s12964-022-00851-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saito T., Nah J., Oka S.I., Mukai R., Monden Y., Maejima Y., et al. An alternative mitophagy pathway mediated by Rab9 protects the heart against ischemia. J. Clin. Invest. 2019;129:802–819. doi: 10.1172/JCI122035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pinton P., Pozzan T., Rizzuto R. The Golgi apparatus is an inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate-sensitive Ca2+ store, with functional properties distinct from those of the endoplasmic reticulum. EMBO J. 1998;17:5298–5308. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.18.5298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li J., Wang Y. Golgi metal ion homeostasis in human health and diseases. Cells. 2022;11:289. doi: 10.3390/cells11020289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nash C.A., Brown L.M., Malik S., Cheng X., Smrcka A.V. Compartmentalized cyclic nucleotides have opposing effects on regulation of hypertrophic phospholipase Cepsilon signaling in cardiac myocytes. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 2018;121:51–59. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2018.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen J., Chen Z.J. PtdIns4P on dispersed trans-Golgi network mediates NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Nature. 2018;564:71–76. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0761-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nagashima S., Tabara L.C., Tilokani L., Paupe V., Anand H., Pogson J.H., et al. Golgi-derived PI(4)P-containing vesicles drive late steps of mitochondrial division. Science. 2020;367:1366–1371. doi: 10.1126/science.aax6089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Legrand D., Herbaut M., Durin Z., Brysbaert G., Bardor M., Lensink M.F., et al. New insights into the pathogenicity of TMEM165 variants using structural modeling based on AlphaFold 2 predictions. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2023;21:3424–3436. doi: 10.1016/j.csbj.2023.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Foulquier F., Amyere M., Jaeken J., Zeevaert R., Schollen E., Race V., et al. TMEM165 deficiency causes a congenital disorder of glycosylation. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2012;91:15–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thines L., Stribny J., Morsomme P. From the Uncharacterized Protein Family 0016 to the GDT1 family: molecular insights into a newly-characterized family of cation secondary transporters. Microb. Cell. 2020;7:202–214. doi: 10.15698/mic2020.08.725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoecker N., Leister D., Schneider A. Plants contain small families of UPF0016 proteins including the PHOTOSYNTHESIS AFFECTED MUTANT71 transporter. Plant Signal. Behav. 2017;12 doi: 10.1080/15592324.2016.1278101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Herrera-Quiterio G.A., Encarnacion-Guevara S. The transmembrane proteins (TMEM) and their role in cell proliferation, migration, invasion, and epithelial-mesenchymal transition in cancer. Front Oncol. 2023;13 doi: 10.3389/fonc.2023.1244740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tsu B.V., Saier M.H., Jr. The LysE superfamily of transport proteins involved in cell physiology and pathogenesis. PLoS One. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0137184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Demaegd D., Foulquier F., Colinet A.S., Gremillon L., Legrand D., Mariot P., et al. Newly characterized Golgi-localized family of proteins is involved in calcium and pH homeostasis in yeast and human cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2013;110:6859–6864. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1219871110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stribny J., Thines L., Deschamps A., Goffin P., Morsomme P. The human Golgi protein TMEM165 transports calcium and manganese in yeast and bacterial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2020;295:3865–3874. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA119.012249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Demaegd D., Colinet A.S., Deschamps A., Morsomme P. Molecular evolution of a novel family of putative calcium transporters. PLoS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0100851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Colinet A.S., Thines L., Deschamps A., Flemal G., Demaegd D., Morsomme P. Acidic and uncharged polar residues in the consensus motifs of the yeast Ca(2+) transporter Gdt1p are required for calcium transport. Cell Microbiol. 2017;19 doi: 10.1111/cmi.12729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lebredonchel E., Houdou M., Potelle S., de Bettignies G., Schulz C., Krzewinski Recchi M.A., et al. Dissection of TMEM165 function in Golgi glycosylation and its Mn(2+) sensitivity. Biochimie. 2019;165:123–130. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2019.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Permyakov S.E., Khokhlova T.I., Uversky V.N., Permyakov E.A. Analysis of Ca2+/Mg2+ selectivity in alpha-lactalbumin and Ca(2+)-binding lysozyme reveals a distinct Mg(2+)-specific site in lysozyme. Proteins. 2010;78:2609–2624. doi: 10.1002/prot.22776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dudev T., Lim C. Principles governing Mg, Ca, and Zn binding and selectivity in proteins. Chem. Rev. 2003;103:773–788. doi: 10.1021/cr020467n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Christianson D.W., Cox J.D. Catalysis by metal-activated hydroxide in zinc and manganese metalloenzymes. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1999;68:33–57. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.68.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Foulquier F., Legrand D. Biometals and glycosylation in humans: congenital disorders of glycosylation shed lights into the crucial role of Golgi manganese homeostasis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 2020;1864 doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2020.129674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krzewinski-Recchi M.A., Potelle S., Mir A.M., Vicogne D., Dulary E., Duvet S., et al. Evidence for splice transcript variants of TMEM165, a gene involved in CDG. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 2017;1861:737–748. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2017.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Snyder N.A., Stefan C.P., Soroudi C.T., Kim A., Evangelista C., Cunningham K.W. H(+) and Pi Byproducts of glycosylation affect Ca(2+) homeostasis and are retrieved from the Golgi complex by homologs of TMEM165 and XPR1. G3 (Bethesda) 2017;7:3913–3924. doi: 10.1534/g3.117.300339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Missiaen L., Raeymaekers L., Dode L., Vanoevelen J., Van Baelen K., Parys J.B., et al. SPCA1 pumps and Hailey-Hailey disease. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004;322:1204–1213. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.07.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rudolph H.K., Antebi A., Fink G.R., Buckley C.M., Dorman T.E., LeVitre J., et al. The yeast secretory pathway is perturbed by mutations in PMR1, a member of a Ca2+ ATPase family. Cell. 1989;58:133–145. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90410-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Colinet A.S., Sengottaiyan P., Deschamps A., Colsoul M.L., Thines L., Demaegd D., et al. Yeast Gdt1 is a Golgi-localized calcium transporter required for stress-induced calcium signaling and protein glycosylation. Sci. Rep. 2016;6 doi: 10.1038/srep24282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eisenhut M., Hoecker N., Schmidt S.B., Basgaran R.M., Flachbart S., Jahns P., et al. The plastid envelope CHLOROPLAST MANGANESE TRANSPORTER1 is essential for manganese homeostasis in arabidopsis. Mol. Plant. 2018;11:955–969. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2018.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zeinert R., Martinez E., Schmitz J., Senn K., Usman B., Anantharaman V., et al. Structure-function analysis of manganese exporter proteins across bacteria. J. Biol. Chem. 2018;293:5715–5730. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M117.790717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gandini C., Schmidt S.B., Husted S., Schneider A., Leister D. The transporter SynPAM71 is located in the plasma membrane and thylakoids, and mediates manganese tolerance in Synechocystis PCC6803. New Phytol. 2017;215:256–268. doi: 10.1111/nph.14526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brandenburg F., Schoffman H., Kurz S., Kramer U., Keren N., Weber A.P., et al. The synechocystis manganese exporter mnx is essential for manganese homeostasis in cyanobacteria. Plant Physiol. 2017;173:1798–1810. doi: 10.1104/pp.16.01895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thines L., Deschamps A., Sengottaiyan P., Savel O., Stribny J., Morsomme P. The yeast protein Gdt1p transports Mn(2+) ions and thereby regulates manganese homeostasis in the Golgi. J. Biol. Chem. 2018;293:8048–8055. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA118.002324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vicogne D., Beauval N., Durin Z., Allorge D., Kondratska K., Haustrate A., et al. Insights into the regulation of cellular Mn(2+) homeostasis via TMEM165. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2023;1869 doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2023.166717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Neville M.C. Calcium secretion into milk. J. Mammary Gland. Biol. Neoplasia. 2005;10:119–128. doi: 10.1007/s10911-005-5395-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Suzuki G. [Clonal anergy as a mechanism of transplantation tolerance] Nihon Rinsho. 1990;48:1929–1934. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dai W., White R., Liu J., Liu H. Organelles coordinate milk production and secretion during lactation: insights into mammary pathologies. Prog. Lipid Res. 2022;86 doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2022.101159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Snyder N.A., Palmer M.V., Reinhardt T.A., Cunningham K.W. Milk biosynthesis requires the Golgi cation exchanger TMEM165. J. Biol. Chem. 2019;294:3181–3191. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA118.006270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Deschamps A., Thines L., Colinet A.S., Stribny J., Morsomme P. The yeast Gdt1 protein mediates the exchange of H(+) for Ca(2+) and Mn(2+) influencing the Golgi pH. J. Biol. Chem. 2023;299 doi: 10.1016/j.jbc.2023.104628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Uhlen M., Fagerberg L., Hallstrom B.M., Lindskog C., Oksvold P., Mardinoglu A., et al. Proteomics. Tissue-based map of the human proteome. Science. 2015;347 doi: 10.1126/science.1260419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thul P.J., Akesson L., Wiking M., Mahdessian D., Geladaki A., Ait Blal H., et al. A subcellular map of the human proteome. Science. 2017;356 doi: 10.1126/science.aal3321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Karlsson M., Zhang C., Mear L., Zhong W., Digre A., Katona B., et al. A single-cell type transcriptomics map of human tissues. Sci. Adv. 2021;7 doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abh2169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gosavi P., Gleeson P.A. The function of the Golgi ribbon structure - an enduring mystery unfolds. Bioessays. 2017;39 doi: 10.1002/bies.201700063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gao C., Cai Y., Wang Y., Kang B.H., Aniento F., Robinson D.G., et al. Retention mechanisms for ER and Golgi membrane proteins. Trends Plant Sci. 2014;19:508–515. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2014.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dulary E., Potelle S., Legrand D., Foulquier F. TMEM165 deficiencies in Congenital Disorders of Glycosylation type II (CDG-II): clues and evidences for roles of the protein in Golgi functions and ion homeostasis. Tissue Cell. 2017;49:150–156. doi: 10.1016/j.tice.2016.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rosnoblet C., Legrand D., Demaegd D., Hacine-Gherbi H., de Bettignies G., Bammens R., et al. Impact of disease-causing mutations on TMEM165 subcellular localization, a recently identified protein involved in CDG-II. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2013;22:2914–2928. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Durin Z., Houdou M., Morelle W., Barre L., Layotte A., Legrand D., et al. Differential effects of D-galactose supplementation on Golgi glycosylation defects in TMEM165 deficiency. Front Cell Dev. Biol. 2022;10 doi: 10.3389/fcell.2022.903953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zajac M., Mukherjee S., Anees P., Oettinger D., Henn K., Srikumar J., et al. A mechanism of lysosomal calcium entry. Sci. Adv. 2024;10 doi: 10.1126/sciadv.adk2317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xia B., Zhang W., Li X., Jiang R., Harper T., Liu R., et al. Serum N-glycan and O-glycan analysis by mass spectrometry for diagnosis of congenital disorders of glycosylation. Anal. Biochem. 2013;442:178–185. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2013.07.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Potelle S., Morelle W., Dulary E., Duvet S., Vicogne D., Spriet C., et al. Glycosylation abnormalities in Gdt1p/TMEM165 deficient cells result from a defect in Golgi manganese homeostasis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2016;25:1489–1500. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddw026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dobie C., Skropeta D. Insights into the role of sialylation in cancer progression and metastasis. Br. J. Cancer. 2021;124:76–90. doi: 10.1038/s41416-020-01126-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Reily C., Stewart T.J., Renfrow M.B., Novak J. Glycosylation in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2019;15:346–366. doi: 10.1038/s41581-019-0129-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zeevaert R., de Zegher F., Sturiale L., Garozzo D., Smet M., Moens M., et al. Bone dysplasia as a key feature in three patients with a novel congenital disorder of glycosylation (CDG) type II due to a deep intronic splice mutation in TMEM165. JIMD Rep. 2013;8:145–152. doi: 10.1007/8904_2012_172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Morelle W., Potelle S., Witters P., Wong S., Climer L., Lupashin V., et al. Galactose supplementation in patients with TMEM165-CDG rescues the glycosylation defects. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2017;102:1375–1386. doi: 10.1210/jc.2016-3443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schulte Althoff S., Gruneberg M., Reunert J., Park J.H., Rust S., Muhlhausen C., et al. TMEM165 deficiency: Postnatal changes in glycosylation. JIMD Rep. 2016;26:21–29. doi: 10.1007/8904_2015_455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Potelle S., Dulary E., Climer L., Duvet S., Morelle W., Vicogne D., et al. Manganese-induced turnover of TMEM165. Biochem. J. 2017;474:1481–1493. doi: 10.1042/BCJ20160910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Vicogne D., Houdou M., Garat A., Climer L., Lupashin V., Morelle W., et al. Fetal bovine serum impacts the observed N-glycosylation defects in TMEM165 KO HEK cells. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2020;43:357–366. doi: 10.1002/jimd.12161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Park J.H. In: GeneReviews((R)) Adam M.P., Feldman J., Mirzaa G.M., Pagon R.A., Wallace S.E., Bean L.J.H., et al., editors. University of Washington; Seattle, WA: 1993. Slc39a8-Cdg. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bonaventura E., Barone R., Sturiale L., Pasquariello R., Alessandri M.G., Pinto A.M., et al. Clinical, molecular and glycophenotype insights in SLC39A8-CDG. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2021;16:307. doi: 10.1186/s13023-021-01941-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Liu Q., Barker S., Knutson M.D. Iron and manganese transport in mammalian systems. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Res. 2021;1868 doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2020.118890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lin W., Vann D.R., Doulias P.T., Wang T., Landesberg G., Li X., et al. Hepatic metal ion transporter ZIP8 regulates manganese homeostasis and manganese-dependent enzyme activity. J. Clin. Invest. 2017;127:2407–2417. doi: 10.1172/JCI90896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Choi E.K., Nguyen T.T., Gupta N., Iwase S., Seo Y.A. Functional analysis of SLC39A8 mutations and their implications for manganese deficiency and mitochondrial disorders. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:3163. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-21464-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lairson L.L., Henrissat B., Davies G.J., Withers S.G. Glycosyltransferases: structures, functions, and mechanisms. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2008;77:521–555. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.061005.092322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Houdou M., Lebredonchel E., Garat A., Duvet S., Legrand D., Decool V., et al. Involvement of thapsigargin- and cyclopiazonic acid-sensitive pumps in the rescue of TMEM165-associated glycosylation defects by Mn(2) FASEB J. 2019;33:2669–2679. doi: 10.1096/fj.201800387R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yonekura S., Toyoshima C. Mn(2+) transport by Ca(2+) -ATPase of sarcoplasmic reticulum. FEBS Lett. 2016;590:2086–2095. doi: 10.1002/1873-3468.12244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chiesi M., Inesi G. Mg2+ and Mn2+ modulation of Ca2+ transport and ATPase activity in sarcoplasmic reticulum vesicles. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1981;208:586–592. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(81)90547-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chiesi M., Inesi G. Adenosine 5′-triphosphate dependent fluxes of manganese and and hydrogen ions in sarcoplasmic reticulum vesicles. Biochemistry. 1980;19:2912–2918. doi: 10.1021/bi00554a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rivinoja A., Pujol F.M., Hassinen A., Kellokumpu S. Golgi pH, its regulation and roles in human disease. Ann. Med. 2012;44:542–554. doi: 10.3109/07853890.2011.579150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Maeda Y., Kinoshita T. The acidic environment of the Golgi is critical for glycosylation and transport. Methods Enzymol. 2010;480:495–510. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(10)80022-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Soonthornsit J., Yamaguchi Y., Tamura D., Ishida R., Nakakoji Y., Osako S., et al. Low cytoplasmic pH reduces ER-Golgi trafficking and induces disassembly of the Golgi apparatus. Exp. Cell Res. 2014;328:325–339. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2014.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Linders P.T.A., Peters E., Ter Beest M., Lefeber D.J., van den Bogaart G. Sugary logistics gone wrong: membrane trafficking and congenital disorders of glycosylation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21:4654. doi: 10.3390/ijms21134654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Van Damme T., Gardeitchik T., Mohamed M., Guerrero-Castillo S., Freisinger P., Guillemyn B., et al. Mutations in ATP6V1E1 or ATP6V1A cause autosomal-recessive cutis laxa. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2017;100:216–227. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Yang X., Lv Z.L., Tang Q., Chen X.Q., Huang L., Yang M.X., et al. Congenital disorder of glycosylation caused by mutation of ATP6AP1 gene (c.1036G>A) in a Chinese infant: a case report. World J. Clin. Cases. 2021;9:7876–7885. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i26.7876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Barua S., Berger S., Pereira E.M., Jobanputra V. Expanding the phenotype of ATP6AP1 deficiency. Cold Spring Harb Mol. Case Stud. 2022;8 doi: 10.1101/mcs.a006195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Guillard M., Dimopoulou A., Fischer B., Morava E., Lefeber D.J., Kornak U., et al. Vacuolar H+-ATPase meets glycosylation in patients with cutis laxa. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2009;1792:903–914. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2008.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Park J.H., Hogrebe M., Gruneberg M., DuChesne I., von der Heiden A.L., Reunert J., et al. SLC39A8 deficiency: a disorder of manganese transport and glycosylation. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2015;97:894–903. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2015.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Morava E. Galactose supplementation in phosphoglucomutase-1 deficiency; review and outlook for a novel treatable CDG. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2014;112:275–279. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2014.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Witters P., Tahata S., Barone R., Ounap K., Salvarinova R., Gronborg S., et al. Clinical and biochemical improvement with galactose supplementation in SLC35A2-CDG. Genet. Med. 2020;22:1102–1107. doi: 10.1038/s41436-020-0767-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sosicka P., Ng B.G., Freeze H.H. Therapeutic monosaccharides: looking back, moving forward. Biochemistry. 2020;59:3064–3077. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.9b00565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Verheijen J., Tahata S., Kozicz T., Witters P., Morava E. Therapeutic approaches in Congenital Disorders of Glycosylation (CDG) involving N-linked glycosylation: an update. Genet. Med. 2020;22:268–279. doi: 10.1038/s41436-019-0647-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lebredonchel E., Houdou M., Hoffmann H.H., Kondratska K., Krzewinski M.A., Vicogne D., et al. Investigating the functional link between TMEM165 and SPCA1. Biochem. J. 2019;476:3281–3293. doi: 10.1042/BCJ20190488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Roy A.S., Miskinyte S., Garat A., Hovnanian A., Krzewinski-Recchi M.A., Foulquier F. SPCA1 governs the stability of TMEM165 in Hailey-Hailey disease. Biochimie. 2020;174:159–170. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2020.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Khan S., Sbeity M., Foulquier F., Barre L., Ouzzine M. TMEM165 a new player in proteoglycan synthesis: loss of TMEM165 impairs elongation of chondroitin- and heparan-sulfate glycosaminoglycan chains of proteoglycans and triggers early chondrocyte differentiation and hypertrophy. Cell Death Dis. 2021;13:11. doi: 10.1038/s41419-021-04458-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Hanna A., Frangogiannis N.G. The role of the TGF-beta superfamily in myocardial infarction. Front Cardiovasc. Med. 2019;6:140. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2019.00140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Santulli G., Marks A.R. Essential roles of intracellular calcium release channels in muscle, brain, metabolism, and aging. Curr. Mol. Pharmacol. 2015;8:206–222. doi: 10.2174/1874467208666150507105105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Reinhardt T.A., Lippolis J.D., Sacco R.E. The Ca(2+)/H(+) antiporter TMEM165 expression, localization in the developing, lactating and involuting mammary gland parallels the secretory pathway Ca(2+) ATPase (SPCA1) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2014;445:417–421. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Peanne R., de Lonlay P., Foulquier F., Kornak U., Lefeber D.J., Morava E., et al. Congenital disorders of glycosylation (CDG): quo vadis? Eur. J. Med. Genet. 2018;61:643–663. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2017.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Yuste-Checa P., Medrano C., Gamez A., Desviat L.R., Matthijs G., Ugarte M., et al. Antisense-mediated therapeutic pseudoexon skipping in TMEM165-CDG. Clin. Genet. 2015;87:42–48. doi: 10.1111/cge.12402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Bammens R., Mehta N., Race V., Foulquier F., Jaeken J., Tiemeyer M., et al. Abnormal cartilage development and altered N-glycosylation in Tmem165-deficient zebrafish mirrors the phenotypes associated with TMEM165-CDG. Glycobiology. 2015;25:669–682. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwv009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Murali P., Johnson B.P., Lu Z., Climer L., Scott D.A., Foulquier F., et al. Novel role for the Golgi membrane protein TMEM165 in control of migration and invasion for breast carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2020;11:2747–2762. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.27668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Lee J.S., Kim M.Y., Park E.R., Shen Y.N., Jeon J.Y., Cho E.H., et al. TMEM165, a Golgi transmembrane protein, is a novel marker for hepatocellular carcinoma and its depletion impairs invasion activity. Oncol. Rep. 2018;40:1297–1306. doi: 10.3892/or.2018.6565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Amini A., Aghabozorg Afjeh S.S., Boshehri B., Hamednia S., Mashayekhi P., Omrani M.D. The relationship between rs534654 polymorphism in TMEM165 gene and increased risk of bipolar disorder type 1. Int. J. Mol. Cell Med. 2021;10:162–165. doi: 10.22088/IJMCM.BUMS.10.2.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Qin Y., Cao L., Zhang J., Zhang H., Cai S., Guo B., et al. Whole-transcriptome analysis of serum L1CAM-Captured extracellular vesicles reveals neural and glycosylation changes in autism spectrum disorder. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2022;72:1274–1292. doi: 10.1007/s12031-022-01994-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Esteves E., Mendes V.M., Manadas B., Lopes R., Bernardino L., Correia M.J., et al. COVID-19 salivary protein profile: unravelling molecular aspects of SARS-CoV-2 infection. J. Clin. Med. 2022;11:5571. doi: 10.3390/jcm11195571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated in this study are provided in the article and its supplementary materials.