Abstract

A 28 days pesticide degradation experiment was conducted for broccoli (Brassica oleracea L. var. italica Planch) and pakchoi (Brassica chinensis L.) with three pesticides (chlorantraniliprole (CAP), haloxyfop-etotyl (HPM), and indoxacarb (IXB)) to explore the effects of biochar on pesticide environmental fate and rhizosphere soil diversity. Rice straw biochar (RB) was applied to soil at a 25.00 t ha−1 dosage under greenhouse conditions, and its effects on the degradation of three pesticides in vegetables and in soil were investigated individually. Overall, RB application effectively facilitated CAP and HPM degradation in broccoli by 13.51–39.42% and in broccoli soil by 23.80–74.10%, respectively. RB application slowed the degradation of CAP, HPM and IXB in pakchoi by 0.00–57.17% and slowed the degradation of CAP in pakchoi by 37.32–43.40%. The results showed that the effect of RB application on pesticide degradation in crops and soil was related to biochar properties, pesticide solubility, plant growth status, and soil characteristics. Rhizosphere soil microorganisms were also investigated, and the results showed that biochar application may be valuable for altering bacterial richness and diversity. The effect of biochar application on pesticide residues in crops and soil was influenced by the vegetable variety first, and the second was pesticide characteristics. RB applied to soil at a 25.00 t ha−1 dosage under greenhouse conditions is recommended for broccoli production to ensure food safety. Our results suggested that biochar application in soil could reduce pesticide non-point source pollution, especially for highly soluble pesticides, and could affect soil microorganisms.

Keywords: Rice straw biochar (RB), Chlorantraniliprole (CAP), Haloxyfop-etotyl (HPM), Indoxacarb (IXB), Degradation, Soil microorganisms

Subject terms: Ecology, Environmental sciences

Introduction

Pesticides have posed soil non-point pollution and human health risks1. A global pesticide study for agricultural soils revealed 387 different pesticides, such as alachlor, which had the highest average concentration of 9.6 mg kg−1, and hexazinone, which had an average concentration of 8.3 mg kg−12. Pesticides can contaminate the soil environment through several routes, and ppt–ppm ranges of pesticide residues have been reported3. As the excessive quantity and long duration of pesticide application will remain in agricultural soil for a long time, it is necessary to develop effective non-point pollution control measures and ecofriendly remediation technologies for agricultural soils contaminated with pesticides.

Broccoli (Brassica oleracea L. var. italica Planch) and pakchoi (Brassica chinensis L.), two dominant vegetable species, are major foods of the Chinese diet, especially in Zhejiang Province. With increasingly high living quality and dietary diversity requirements, vegetable planting areas and consumption amounts have increased annually. Pesticides are necessary plant protection products in modern agriculture, and their application quantity is much greater in greenhouse-planted vegetable production. However, pesticides threaten the soil environment and human health due to their toxicity and improper use. Chlorantraniliprole (CAP), haloxyfop-etotyl (HPM), and indoxacarb (IXB) are three commonly used pesticides in broccoli and pakchoi production, with CAP and IXB being insecticides, and HPM being applied as a herbicide. Field studies have shown that CAP degrades slowly in soil, water, and sediment and poses a high risk of river and underwater contamination due to its high leaching potential4,5. HPM is highly toxic to aquatic organisms and may have long-term adverse effects on the water environment6,7. IXB is a new non-systemic insecticide belonging to the oxadiazine group and is metabolized by insect esterases8. Further studies are required to control the pollution caused by these three commonly used pesticides in broccoli and pakchoi production, and the effectiveness and efficiency of biochar amendments need to be verified.

Biochar, a multifunctional carbon-rich material, is derived from life activities and plant-derived agroforestry biomass waste. Previous studies have shown that due to its good absorption ability, biochar favorably affects pesticide environmental behavior, including pesticide migration control in soil, reduced agricultural safety caused by pesticides, and environmental safety problems linked to pesticide contamination9,10. Former studies have shown that biochars are potential sorbent for a variety of organic pollutants including pesticides because of their specific surface characteristics11–13. After entering environmental media, pesticides undergo degradation, migration, and other behaviors14,15. Pesticides environmental fate are determined by several factors, such as environmental conditions and physical, chemical, and biological degradation processes16,17. Biochar addition to soil will change soil characteristic including adsorption ability, pH value, soil bulk density, and thus will influence pesticide fate and transformation in environment18. Moreover, studies have reported that biochar addition to soil could shift the bacterial community and thus improve soil quality19, and influences the soil environment, including soil aggregation, pH, nutrient retention, and rhizosphere microorganism diversity and richness20. Field trials revealed that biochar application to soil could reduce the bioavailability and plant uptake of pesticides at the same time21,22. However, biochar amendments applied to soils do not always result in positive results, which could lead to greater pesticide accumulation because of their strong absorption ability or increased pesticide half-lives23,24. Factors, including soil properties, biochar types, pesticide characteristics, and crop types, may influence the bioavailability reduction degree of biochar application. Thus, the effects of biochar application on farmland differ greatly25–28.

Rice straw biochar (RB) originates from rice production and is produced from rice straw at temperatures of approximately 450 °C. Approximately 600–800 million tons of rice straw are produced annually in Asian countries29. Thus, RB is an appealing choice for pesticide non-point control during vegetable production because of its feasible large-scale production, cost-effective performance, and eco-friendly environmental impact. Studies have focused mainly on the ability of biochar to absorb pesticides, as well as the effects of biochar on pesticide degradation30–32. Systematic research on the effects of biochar application at the farmland scale is necessary to study pesticide residue dynamics, the effects on rhizosphere soil bacteria of typical crops, and the effects of biochar application on soil improvement mechanisms.

Therefore, we carried out a farm-scale trial to explore the effect of RB on three pesticides applied to broccoli, pakchoi and soil under greenhouse conditions. The effects of RB application on the degradation of pesticides and soil were studied individually, and its effects on soil bacterial communities under greenhouse conditions were investigated at the same time. Our aims were (1) to obtain quantitative data of the impact of RB application on the degradation rates of CAP, HPM, and IXB in broccoli, pakchoi (two typical crops), and its effect on these three pesticides degradation rates in soil; (2) to evaluate the impact of RB application on soil bacterial communities under greenhouse conditions with broccoli and pakchoi planting; and (3) to reveal the factors affecting the effectiveness of RB application on pesticide degradation.

Materials and methods

Biochar and pesticides

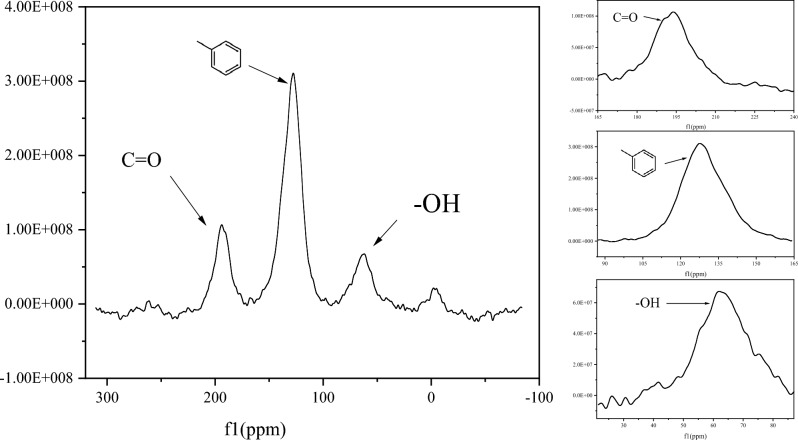

RB, which was heated at a rate of 5–10 °C min−1 and treated at 400–450 °C, was supplied by the Biomass Carbon Engineering Center of the Zhejiang Academy of Agricultural Sciences. Table 1 displays the physical and chemical characteristics of RB and the soil. RB had a pH of 6.78, a large amount of C (51.24%), and a large Brunauer–Emmet–Teller (BET) area (144.79 m2 g−1). The NMR characterization of RB are shown in Fig. 1. Figure 1 shows that there were three main regions of the spectrum information regarding the overall structure of the RB. The chemical shifts between 0 and 45 ppm were likely related to alkyl carbon. Aromatic carbon was present between 103 and 165 ppm, and carboayl carbon was present between165 and 220 ppm.

Table 1.

Properties of rice straw biochar (RB) and soil.

| Material | pH | N (%) | C (%) | H (%) | S (%) | O (%) | Density (g·cm−3) | BET (m2 g−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RB | 6.78 | 1.16 | 51.42 | 2.41 | 0.33 | 44.68 | 0.35 | 144.79 |

BET means Brunner − Emmet − Teller (BET) measurements for surface area.

Fig.1.

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) curve of the WSB characterization.

The chromatographic grade reagents were supplied by Aladdin Reagent Co., Ltd, Shanghai, China. Water of chromatographic grade was supplied by Wahaha Co., Ltd, Hangzhou, China. The CAP, HPM and IXB standard of 99% purity was supplied by Dr. Ehrenstorfer Co., Ltd, Germany. The trade name, active ingredient and the structures and physio-chemical properties of these three commercial pesticides is shown in Table 233,34. Commercial CAP, HPM and IXB were purchased from local farmers’ markets and were sprayed in October 2021 at low and high doses at the late growth stage of broccoli and pakchoi. The low dosage meant the commercial pesticides recommended dosage according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and the active ingredient of CAP, HPM and IXB were 41.25, 80.00 and 22.00 g a.i.ha−1, respectively. The high dosage meant the 1.5 times of the commercial pesticides recommended dosage, and the active ingredient of CAP, HPM and IXB were 61.87, 120.00 and 33.00 g a.i.ha−1, respectively. The dosages used are shown in Table 3.

Table 2.

Structures and physiochemical properties of three pesticides.

| Items | Chlorantraniliprole (CAP) | Haloxyfop-etotyl (HPM) | Indoxacarb (IXB) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structure |  |

|

|

| Trade name | Dupont company (America) | Sichuan Weikeqi Biotechnology Co., Ltd | Dupont company (America) |

| Active ingredient | 35% water dispersible granules (DF) | 30% emulsifiable concentrate (EC) | 15% emulsifiable concentrate (EC) |

| CAS registry no | 500008-45-7 | 69806-34-4 | 144171-61-9 |

| Molecular formula | C18H14BrCl2N5O2 | C15H11ClF3NO4 | C22H17ClF3N3O7 |

| Molecular weight (g mol−1) | 483.152 | 361.7 | 527.1 |

| Melting point (°C) | 208–210 | 107.5 | 139–141 |

| Vapor pressure (25 °C, Pa) | 2.1 × 10−8 | 1.33 × 10−3 | 2.13 × 10−4 |

| Solubility (mg L−1) | 1.023 | 43.3 | < 0.5 |

| Log Kow | 2.76 | 3.12 | 4.65 |

| Kd | 3.18 | – | 46.3 |

| Koc (mL g−1) | 304.1 | – | 4483 |

Table 3.

Dosages of the three pesticides used in different trials (g a.i.ha−1).

| Pesticides | Low dosage (recommended dosage) | High dosage (1.5 times the recommended dosage) |

|---|---|---|

| Chlorantraniliprole, CAP | 41.25 | 61.87 |

| Haloxyfop-r-methyl, HPM | 80.00 | 120.00 |

| Indoxacarb, IXB | 22.00 | 33.00 |

Greenhouse experimental design

The experiment was conducted under greenhouse conditions from May 2021 to November 2021 in Shaoxing (30° 04′ N, 120° 64′ E) city. The soil characteristics were as follows: 21.4 g kg−1 organic material content, 0.59 g kg−1 total K content (K2O), 0.43 g kg−1 total P content (P2O5), 1.28 g kg−1 total N content, and pH value of 6.62.

Three replicates of the experimental plots were used, and the five treatments were carried out as follows: (i) T1: Without RB and with low pesticide doses; (ii) T2: Without RB and with high pesticide doses; (iii) T3: With RB and low pesticide doses; (iv) T4: With RB and high pesticide doses; and (v) CK: Three plots without RB and pesticides applied (control). With three replicates of each treatment and three blank plots with a width of 1 m separating them, each plot had an area of 40 m2. Thus, there were 15 plots for broccoli and 15 plots for pakchoi, for a total of 30 plots. RB was applied to the field plots in April and August 2021 at a rate of 25 t ha−1 (5% v/v to rhizosphere soil 15 cm above), and the RB was mixed thoroughly with the root soil one month prior to the experiment.

Three pesticides were applied in October 2021, which was at the late growth stage of broccoli and pakchoi. During the pesticide application period in October 2021, the trial conditions in the greenhouse were: daily air temperature changed from 18 to 26 °C, and the relative humidity varied between 50 and 64%.

The ripe parts of broccoli flowers and pakchoi leaves, and soil samples were collected after pesticide application at the following intervals: 2 h, and 1, 3, 5, 7, 14, 21, and 28 days. Crop samples of 200 g, including broccoli and pakchoi, were collected from each experimental plot, homogenized and immediately stored at − 20 °C. Soil samples for pesticide residue detection and microorganism detection (200 g) were collected from rhizosphere soil 2 cm from the plant roots using the ‘five-point method’. For ‘five-point method’, we first determined the midpoint of the trial plot as the center sampling point, then selected four points on the diagonal that were equidistant from the center sample as the sample points, and there were five sample points in total. Soil samples from the five sample points were collected and mixed together as one experimental plot sample. The collected soil samples were sieved through 2 mm mesh on the sampling day, and then stored at − 20 °C for pesticide residue detection. For soil bacterial communities samples, the soil samples were put into sterile sampling bag and then stored at − 80 °C for further detection35,36.

Sample analysis

Pesticide residue analysis

The QuEChERS (Quick, Easy, Cheap, Effective, Rugged, and Safe) method was used for pesticide analysis in broccoli, pakchoi, and soil samples. The method utilized for pesticide analysis was liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC‒MS/MS)37,38. Table 4 lists the specific detection parameters for the three pesticides.

Table 4.

Detection parameters of the three pesticides.

| Pesticides | Retention time | m/z | LOD ( μg kg-1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CAP | 1.552 | 484.00 > 452.90 | 5.00 |

| HPM | 1.004 | 528.10 > 150.10 | 0.66 |

| IXB | 1.506 | 484.00 > 452.90 | 1.89 |

CAP chlorantraniliprole, HPM haloxyfop-etotyl, IXB indoxacarb, LOD limit of detection, m/z mass-to-charge ratio.

Soil DNA extraction and quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis

Microbial community genomic DNA was extracted from soil samples using the E.Z.N.A.® soil DNA Kit (Omega Bio-tek, Norcross, GA, U.S.) according to manufacturer’s instructions. TE buffer with 1 mM EDTA and 10 mM Tris–HCl, and a pH at 8.0, was used for soil DNA dilution and then stored at − 20 °C for further use39–41. TruSeqTM DNA Sample Prep Kit (OMEGA, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The primer pairs 338F (5′-ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCAG-3′) and 806R (5′-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3′) were used to amplify theV3–V4 regions of the bacterial 16S rRNA genes42,43. The PCR amplification of 16S rRNA gene was performed as follows: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 3 min, followed by 27 cycles of denaturing at 95 °C for 30 s, annealing at 55 °C for 30 s and extension at 72 °C for 45 s, and single extension at 72 °C for 10 min, and end at 4 °C. The PCR mixtures contain 5 × TransStart FastPfu buffer 4 μL, 2.5 mM dNTPs 2 μL, forward primer (5 μM) 0.8 μL, reverse primer (5 μM) 0.8 μL, TransStart FastPfu DNA Polymerase 0.4 μL, template DNA 10 ng, and finally ddH2O up to 20 μL.

Operational taxonomic units (OTUs) with 97% similarity cutoff were clustered using UPARSE version 7.1, and venn diagram of bacterial diversity analysis at the class level was performed44,45.

Quality control and data analysis

The matrix effects on the soil, soil biochar, and vegetables (broccoli and pakchoi) were investigated during the pesticide detection period. Matrix effects were evaluated using the formula B/A × 100%, where A represents the slope of the solvent standard and B represents the matrix-matched calibration curve. A comparison of the matrix-matched calibration and solvent calibration results is presented in Table 5. The slope ratios of CAP, HPM, and IXB were within 10% of the slope ratio of 1.0 (106.69–83.16%). Therefore, the matrix effects of the three pesticides in soil, soil–biochar, broccoli, and pakchoi were negligible46.

Table 5.

Matrix effect of three pesticides under different trials.

| Pesticides | Matrix | Matrix effect (%) |

|---|---|---|

| CAP | Pakchoi | 83.16 ± 2.58 |

| Soil | 91.36 ± 3.26 | |

| Soil–biochar | 88.09 ± 4.35 | |

| Broccoli | 84.50 ± 4.08 | |

| HPM | Pakchoi | 89.39 ± 3.26 |

| Soil | 85.09 ± 4.38 | |

| Soil–biochar | 85.06 ± 3.68 | |

| Broccoli | 85.13 ± 2.68 | |

| IXB | Pakchoi | 85.95 ± 3.86 |

| Soil | 102.19 ± 5.23 | |

| Soil–biochar | 106.69 ± 3.65 | |

| Broccoli | 86.06 ± 6.23 |

CAP chlorantraniliprole, HPM haloxyfop-etotyl, IXB indoxacarb.

Pesticide degradation study

In the field trials, the pesticide dissipation process conformed to first-order kinetics. The degradation rate constant and half-lives can be calculated by the first-order rate equation Ct = C0−kt, where Ct represents the concentration of the pesticide residue at time t, C0 represents the initial concentration after application, and k is the degradation rate constant (days−1). The half-life (t1/2) is calculated by the equation t1/2 = ln2/k47,48.

A scatter plot and the degradation dynamics equation were visualized using Origin 2021.

The Ethics Committee of Zhejiang Academy of Agricultural Sciences approved the study, and Institute of Agro-product Safety and Nutrition organized the field experiment. The methods in the study were carried out in accordance with the ethical standards and guidelines of the Ethics Committee of Zhejiang Academy of Agricultural Sciences.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

All authors have read, understood, and complied as applicable with the statement on “Ethical responsibilities of Authors”, as found in the Instructions for Authors.

Results and discussion

Impact of biochar on the degradation rates of three pesticides in broccoli and soil

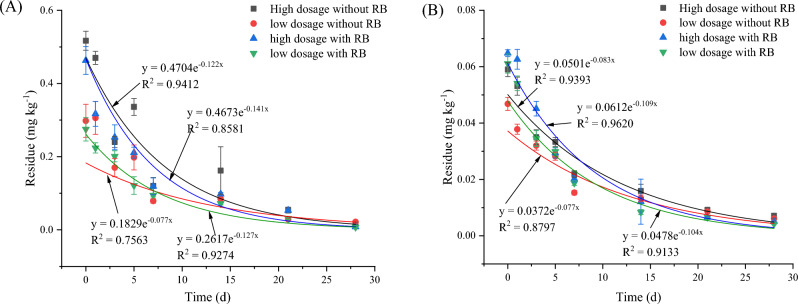

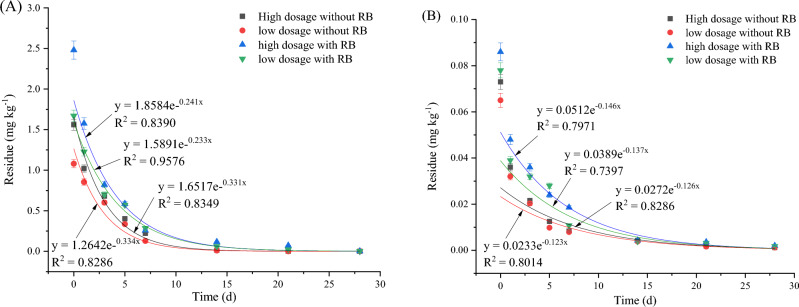

The dynamic residues of CAP in broccoli and soil are shown in Figs. 2 and S1. CAP degradation in broccoli and soil was fitted to a first-order equation. As shown in Fig. 1A, the half-lives of CAP on broccoli were 5.680–9.000 days without RB application and 4.915–5.456 days with RB application. As shown in Fig. 1B, the half-lives of CAP in soil were 8.349–9.000 days with RB application and 6.357–6.663 days without RB application. For CAP in broccoli and soil, 5% (v/v) RB amendment in soil significantly affected the CAP degradation rate. The results showed that RB application greatly changed the CAP degradation dynamics in broccoli and soil. RB application shortened the half-life by 13.46–39.37% in broccoli and 23.86–25.96% in soil. The results showed that RB application facilitated CAP degradation in broccoli and soil.

Fig. 2.

CAP degradation in broccoli (A) and soil (B). Note CAP means chlorantraniliprole, and RB means rice straw biochar.

The effects of the dynamic residue of HPM in broccoli and soil are shown in Figs. 3 and S2. HPM is a commonly used herbicide. As shown in Fig. 3A, when HPM was applied to broccoli, the half-lives of HPM were 5.588–6.187 days without RB application and 3.572–4.225 days with RB application. As shown in Fig. 3B, the half-lives of HPM in broccoli soil were 6.132–7.700 days without RB application and 1.997–3.667 days with RB application. The results showed that RB application greatly changed the HPM degradation dynamics in broccoli and soil. RB application shortened the half-life by 24.39–42.26% in broccoli and 40.19–74.06% in soil. The results showed that RB application facilitated HPM degradation in broccoli and soil.

Fig. 3.

HPM degradation in broccoli (A) and soil (B). Note HPM means haloxyfop-etotyl, and RB means rice straw biochar.

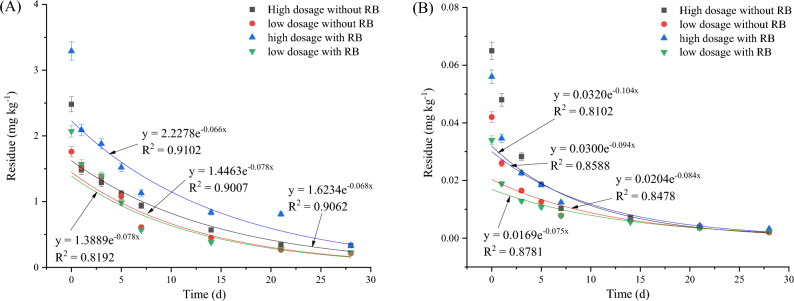

The effects of the dynamic residue of IXB on broccoli and soil are shown in Figs. 4 and S3. As shown in Fig. 4A, when IXB was applied to broccoli, its half-lives were 4.985–5.211 days without RB application and 3.850–5.634 days with RB application. The results showed that at a high IXB dosage, RB application accelerated IXB degradation in broccoli by 22.76% at high IXB dosage, while at low IXB dosage, RB application slowed IXB degradation in broccoli by 8.117%. As shown in Fig. 4B, the half-lives of IXB in broccoli soil were 9.118–13.32 days without RB application and 9.118–18.16 days with RB application. RB application slowed IXB degradation in broccoli soil by 46.08% at high IXB dosage, and accelerated IXB degradation in broccoli soil by 49.79%at low IXB dosage.

Fig. 4.

IXB degradation in broccoli (A) and soil (B). Note IXB means indoxacarb and RB means rice straw biochar.

Studies have shown that pesticide degradation is influenced by factors such as sunlight, rainfall, and wind, and it is worth noticing that soil microbial activity is also a key factor in pesticide degradation. Broccoli flowers at the late growth stage, but their leaves and stems are usually not eaten and make up 60–75% of the total plant biomass. We collected ripe broccoli flowers for pesticide analysis. Three applications occurred during the late growth stage of broccoli, and the biomass did not significantly change during this period. The major factors that led to these differences were pesticide characteristics. CAP and HPM had higher solubility than IXB, and RB addition accelerated broccoli growth and enhanced rhizosphere soil bacterial abundance, thus promoting CAP and HPM degradation in both broccoli and soil. As a reduced-risk broad-spectrum insecticide, IXB has strong permeability, and the effect of RB addition on its degradation rate was different from that of CAP and HPM49–51. Former studies have shown that as broccoli leaves and flowers had more developed wax layer on the cuticle, three pesticides applied on broccoli probably did not enter the plant tissue. RB addition improves soil organic matter (SOM) content, which is a dynamic soil component that can control the sorption and degradation of pesticides and improve broccoli growth52. Our results showed that, for these three pesticides applied in broccoli, RB application facilitated CAP and HPM degradation both in soil and broccoli. For IXB degradation, the effect of RB application was not stable both in soil and broccoli due to its strong permeability and low solubility.

Impact of biochar on the degradation rates of three pesticides in pakchoi and soil

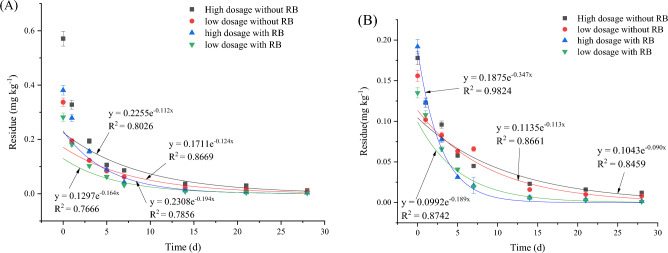

The effects of the dynamic residue of CAP on pakchoi and soil are shown in Figs. 5 and S4. As shown in Fig. 5A, when CAP was applied to pakchoi, the half-lives of CAP were 7.875–10.19 days without RB application and 10.50–12.37 days with RB application. As shown in Fig. 5B, the half-lives of CAP in pakchoi soil without RB application and with RB application were 4.846–5.456 days and 6.132–6.300 days, respectively. The results showed that for CAP in pakchoi and soil, amendment with 5% (v/v) RB slowed the degradation rate at both high and low doses. The degree of degradation was 3.042–57.07% in pakchoi and 15.46–26.53% in soil.

Fig. 5.

CAP degradation in pakchoi (A) and soil (B). Note CAP means chlorantraniliprole, and RB means rice straw biochar.

The effects of the dynamic residue of HPM on pakchoi and soil are shown in Figs. 6 and S5. As shown in Fig. 6A, when HPM was applied to pakchoi, the half-lives of HPM were 2.075–2.093 days without RB application and 2.875–2.974 days with RB application. As shown in Fig. 6B, the half-lives of HPM in pakchoi soil were 5.500–5.634 days without RB application and 4.746–5.058 days with RB application. For HPM in pakchoi and soil, amendment with 5% (v/v) RB slowed HPM degradation in pakchoi by 37.36–43.42% and accelerated HPM degradation in pakchoi soil by 10.22–13.71%.

Fig. 6.

HPM degradation in pakchoi (A) and soil (B). Note HPM means haloxyfop-etotyl, and RB means rice straw biochar.

The effects of the dynamic residue of IXB on pakchoi and soil are shown in Figs. 7 and S6. As shown in Fig. 6A, the half-lives of IXB in pakchoi were 8.884–10.19 days without RB application and 8.884–10.50 days with RB application. As shown in Fig. 6B, the half-lives of IXB in pakchoi soil were 6.663–8.250 days without RB application and 7.372–9.240 days with RB application. For IXB in pakchoi and soil, amendment with 5% (v/v) RB slowed the degradation rate of IXB in pakchoi by 0–3.04% and slowed IXB degradation in soil by 10.64–12.00%. Pakchoi is a leafy vegetable, and its biomass increases significantly at the later stage of growth. With the effect of pakchoi root exudation, these three pesticides exhibited reduced mobility after being adsorbed onto biochar53,54.

Fig. 7.

IXB degradation in pakchoi (A) and soil (B). Note IXB means indoxacarb, and RB means rice straw biochar.

For the three pesticides in pakchoi leaves, RB addition accelerated CAP degradation in pakchoi at a high dose and slowed CAP degradation at a low dose. RB addition slowed HPM degradation in pakchoi both at high dose and low dose. For the three pesticides in the soil, RB addition slowed the degradation of CAP and IXB at both high and low doses. Pakchoi belongs to leafty vegetable. Former study showed that the pesticide metabolites of the highest concentration and the largest variety were detected in the leaves and it was considered that leaves were the target organ of pesticide contact and biotransformation55. As pakchoi was planted under greenhouse conditions, and the result showed that pesticide metabolites were influenced by the harvest interval, and it was consistent with the former results56. Compared to the wax layer cuticle of broccoli leaves and flowers, the leaves of pakchoi were smooth and this made pesticide penetration easier to happen. Our results showed that, for these three pesticides applied in pakchoi, RB application only facilitated HPM degradation in soil, but slowed the degradation rate of CAP and IXB degradation in both soil and leaves. In comparison to broccoli, the biomass production of pakchoi was less in a 28-day pre-harvest interval (PHI) before late growth stage. On this occasion, the residue levels and pesticide metabolite decreased supposedly in relation to plant biomass and growing phase. Thus the impact of biochar on the degradation rate of pesticides was influenced by vegetable variety mostly.

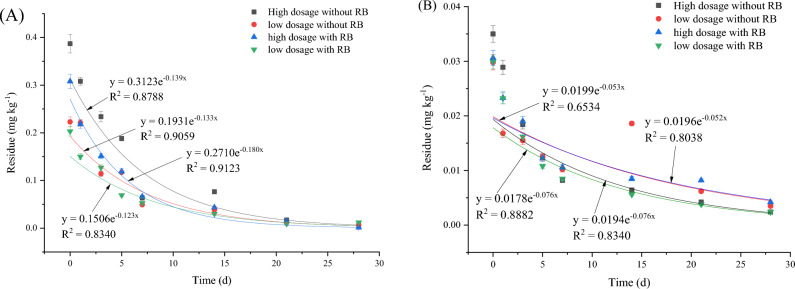

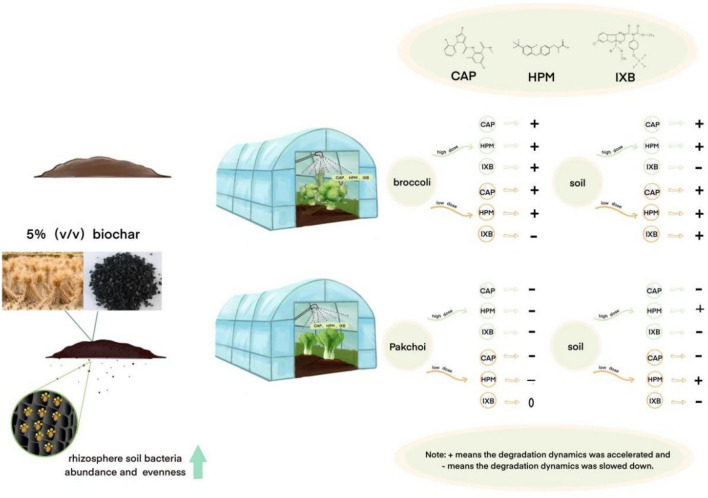

Summary of the effects of RB on complex pesticide degradation

The results showed that dissipation of the pesticides followed the first-order kinetics and the half-lives was consistent with previous studies57–59. This experiment was conducted under greenhouse field conditions with complex pesticides, including CAP, HPM, and IXB. Overall, with the addition of 5% (v/v) RB to the rhizosphere soil, the effects of RB on the three pesticides and soil are shown in Fig. 8 and Table 6.

Fig. 8.

Summary of the effects of RB on complex pesticide degradation.

Table 6.

Effect of rice straw biochar (RB) on pesticide degradation dynamics under different trials.

| CAP | HPM | IXB | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Broccoli | Broccoli | High dose | + | + | + |

| Low dose | + | + | − | ||

| Soil | High dose | + | + | − | |

| Low dose | + | + | + | ||

| Pakchoi | Pakchoi | High dose | − | − | − |

| Low dose | − | − | 0 | ||

| Soil | High dose | − | + | − | |

| Low dose | − | + | − | ||

“ + ” means that the degradation dynamics were accelerated, “ − ” means that the degradation dynamics were slowed, and “0” means that the degradation dynamics were not changed.

For the role of pesticides adsorption onto RB and the degradation rate alteration, adsorption procedure is an important process that determines pesticide environmental fate in soil and thus influence their degradation in vegetables. Initially, pesticide molecules are retained on the surface of solid particles, and this procedure is mainly physico-chemical process through mechanisms including van der Waals forces, hydrogen bonding, ionic bonding and covalent bonding60. Pesticide molecules can also penetrate and be trapped within the pores of soil and biochar. The physical and chemical adsorption on biochar reduces the migration and transformation of pesticides. Biochar has many functional groups and thus will enhance the combination between pesticides and biochar61. Additionally, biochar displays high efficiency in improving sorption capacity of the soil to pesticides, and accelerates pesticides degradation62. In addition, biochar provides large amount of dissolved organic carbon and will facilitate plant growth, and in biochar-soil-root system, pesticide degradation will be changed63.

The effect of RB on pesticide degradation dynamics may be affected by compound factors, including biochar type, pesticide type, agricultural product type, and soil characteristics. The ability of organic matter to absorb biochar mostly involves physical adsorption, chemical adsorption, and microbial degradation. For example, studies have shown that biochar absorption decreases during the aging period because contaminants can be released into the soil and then taken up by plants. The characterization analysis of RB showed that there was a large amount of alkyl carbon, aromatic carbon and carboayl carbon. Previous studies have shown that the π–π electron donor acceptor interaction and π–H-bonding are the primary adsorption sites of RB adsorption64. Former studies showed that biochar was effective to the remediation of pesticides polluted soils such as chlorpyrifos65–67. However, for different types of biochars and pesticides, the amendment of soils with biochar did not always showed positive results, and it would also led to greater accumulation and made the pesticide less available to microbial degradation and increased their half-lives. There are also uncertainties of biochar application in the remediation of pesticide-contaminated soils68. Our results showed that effect of biochar addition on pesticide residues in crops and soil was influenced mainly by the growth status of crops, and the characteristics of pesticides were the second most important factor.

RB application increased rhizosphere soil bacterial abundance and evenness

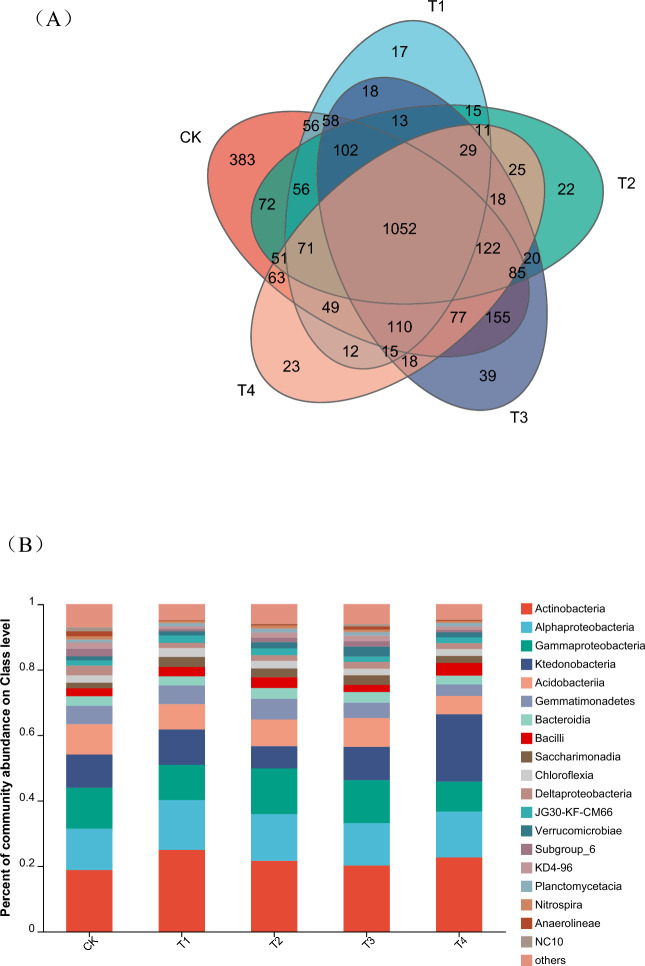

Rhizosphere soil was classified into four treatment groups as shown in the field experimental design (T1, T2, T3 and T4) and the CK group. Sequence readings and operational taxonomic units (OTUs) were grouped at the 97% similarity level, and the OTUs were clustered. A Venn diagram of the percentage abundance of rhizosphere soil bacteria at the class level and the richness and diversity indices of the soil bacterial community are shown in Fig. 9.

Fig. 9.

Venn diagram (A) and relative abundance of main soil fungal classes (B) (T1: treatment without RB and with low doses of pesticides; T2: treatment without RB and with high doses of pesticides; T3: treatment with RB and low doses of pesticides; T4: treatment with RB and high doses of pesticides.)

Venn diagram analysis of the OTUs at 97% sequence similarity revealed that all the samples shared 1052 OTUs, which accounted for 36.82% of the total OTUs observed (Fig. 8A). At the class level, these shared OTUs mostly consisted of sequences from Actinobacteria, Alphaproteobacteria, Gammaprotebacteria, Ktedonobacteria, Acidobacteria, and Gemmatiminatetes (Fig. 8B). Figure 8B showed that, compared with the control (CK) group, the T1 and T2 treatment groups with pesticide application exhibited increased relative abundances of Actinobacteria (with percentages of 0.0614 and 0.0282, respectively) and Alphaproteobacteria (with percentages of 0.0259 and 0.0166, respectively). The relative abundance of Gammaproteobacteria decreased by 0.0174 under the T1 treatment with low doses of pesticides and increased by 0.0144 under the T2 treatment with high doses of pesticides. The relative abundance of Ktedonobacteria increased under the T1 treatment with low doses of pesticides, with a percentage of 0.0063, and decreased under the T2 treatment with high doses of pesticides, with a percentage of 0.0338. The relative abundance of Acidobacteria tended to decrease in the T1 and T2 treatment groups, with percentages of 0.0152 and 0.0112, respectively. The relative abundance of Gemmatminatetes increased in the T1 and T2 treatment groups, with percentages of 0.0013 and 0.0074, respectively. Overall, pesticide application increased the relative abundances of Actinobacteria, Alphaproteobacteria, and Gemmatiminatetes and decreased the relative abundance of Acidobacteria.

Summary statistics of Illumina MiSeq sequencing are shown in Table 7. Species abundance and evenness are reflected by the Shannon index, while species richness is reflected by the Chao index69. As shown in Table 7, compared with the CK, the T1, T2, T3, and T4 treatments increased the Chao1 estimator by 7.20%, 5.45%, 19.21%, and 11.85%, respectively. Pesticide and RB applications increased species richness. The T1 and T2 treatments was without RB and with pesticide application, results showed that the Shannon index was decreased by 1.14% and 0.65%, respectively, and this showed that Pesticide application decreased the rhizosphere soil bacterial abundance and evenness. The T3 and T4 treatments was with RB and pesticide application at the same time, the Shannon index was increased by 3.75% and 5.39%, respectively, and this showed that, while pesticide and RB application combined increased the rhizosphere soil bacterial abundance and evenness. The result was in consisent with the former studies24.

Table 7.

Summary statistics of Illumina MiSeq sequencing.

| Sequences | Shannon | Simpson | Ace | Chao | Coverage | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CK | 30,958 ± 12 | 6.12 ± 0.24 | 0.0049 ± 0.0006 | 1950.34 ± 20.41 | 1933.17 ± 12.32 | 0.99 ± 0.12 |

| T1 | 30,945 ± 18 | 6.05 ± 0.36 | 0.0056 ± 0.0004 | 2104.14 ± 18.36 | 2072.43 ± 10.24 | 0.98 ± 0.06 |

| T2 | 30,950 ± 10 | 6.08 ± 0.23 | 0.0055 ± 0.0002 | 2199.98 ± 20.36 | 2038.66 ± 18.64 | 0.98 ± 0.06 |

| T3 | 30,928 ± 6 | 6.35 ± 0.64 | 0.0046 ± 0.0004 | 2324.03 ± 23.61 | 2304.55 ± 22.46 | 0.98 ± 0.04 |

| T4 | 30,896 ± 16 | 6.45 ± 0.36 | 0.0087 ± 0.0008 | 2144.11 ± 18.64 | 2162.32 ± 23.58 | 0.98 ± 0.03 |

Rhizosphere soil bacteria may affect nutrient transport between plants and soil and are irreplaceable. Therefore, bacteria affect crop growth and the accumulation of nutrient elements and thus affect pesticide degradation in both soil and crops70–72. Former studies showed that biochar addition in soil would shift bacterial communities and enhance microbial diversity, and the response of the soil microbial community to bichar was the key factors for pesticides environmental fate73,74. Our experimental soil was mostly composed of sequences belonging to Actinobacteria, Alphaproteobacteria, Gammaproteobacteria, Ktedonobacteria, Acidobacteria, and Gemmatimonadetes. Pesticide and RB application together increased the relative abundances of Actinobacteria, Alphaproteobacteria, Ktedonobacteria, and Gemmatimonadetes and decreased the relative abundances of Acidobacteria and Gemmatimonadetes. The Chao1 estimator was used to determine the abundance, and the Shannon index was used to determine the diversity of rhizosphere soil bacteria75. The results showed that pesticide and RB application affected soil bacterial ecological systems and the structure and abundance of microorganisms76,77. Our study highlighted RB application and its effect on three pesticides (CAP, HPM, and IXB) to explore the effects on pesticide environmental fate and rhizosphere soil diversity, and the soil bacteria activity and soil bacterial community in RB amended soils affected the biodegradation and the environmental fate of these three pesticides.

Conclusions

The effects of RB application on the degradation and environmental fate of pesticide residues in agricultural soil may be affected by factors such as biochar type, pesticide type, crop type, and soil characteristics. Our results demonstrated that the effect of biochar addition on pesticide residues in crops and soil was influenced mostly by the growth status of crops, and the characteristics of pesticides were the second most important factor.

For broccoli planted under greenhouse conditions, the biomass did not significantly change during the late growth stage or the pesticide application period. Compared with IXB, RB application accelerated CAP and HPM degradation with higher solubility and enhanced rhizosphere soil bacterial abundance, thus promoting CAP and HPM degradation in both broccoli and soil.

The biomass of pakchoi increased greatly at the late growth stage, and RB application did not obviously affect the degradation of the three pesticides. In the pakchoi soil, CAP and IXB exhibited reduced mobility after being absorbed by biochar HPM had the highest solubility and was easier to degrade with the addition of RB.

Moreover, RB application may be valuable for altering bacterial richness and diversity in rhizosphere soil. Pesticide and RB application affected rhizosphere soil bacterial diversity and thus affected soil bacterial ecological systems. RB applied to soil at a 25.00 t ha−1 dosage under greenhouse conditions is recommended for broccoli production to ensure food safety.

RB application is an effective measure for reducing nonpoint source pesticide pollution, especially for highly soluble pesticides such as CAP and HPM.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Professor Shengmao Yang (Biomass Carbon Engineering Center of the Zhejiang Academy of Agricultural Sciences) for providing the rice straw biochar sample.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. C.S. and Y.L. wrote original draft, and K.B., W.Z. and Q.W. did formal analysis. Q.W. reviewed and the whole article. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology of the People’s Republic of China for its invaluable support through the National Key R&D Program of China (2018YFF0213406 and 2018YFF0213505).

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article and its supplementary information files.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-70932-3.

References

- 1.Abbasi, H. et al. Quantification of heavy metals and health risk assessment in processed fruits’ products. Arab. J. Chem.13(12), 8965–8978. 10.1016/j.arabjc.2020.10.020 (2020). 10.1016/j.arabjc.2020.10.020 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sabzevari, S. & Hofman, J. A worldwide review of currently used pesticides’ monitoring in agricultural soils. Sci. Total Environ.812, 152344. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.152344 (2022). 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.152344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Estévez, E., Cabrera, M. D., Molina-Díaz, A., Robles-Molina, J. & Palacios-Díaz, M. D. Screening of emerging contaminants and priority substances (2008/105/EC) in reclaimed water for irrigation and groundwater in a volcanic aquifer (Gran Canaria, Canary Islands, Spain). Sci. Total Environ.433, 538–546. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2012.06.031 (2012). 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2012.06.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hossain, M. Z., Bahar, M. M. & Sarkar, B. Biochar and its importance on nutrient dynamics in soil and plant. Biochar2(4), 379–420. 10.1007/s42773-020-00065-z (2020). 10.1007/s42773-020-00065-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Song, C. et al. Risk assessment of chlorantraniliprole pesticide use in rice-crab coculture systems in the basin of the lower reaches of the Yangtze River in China. Chemosphere230, 440–448. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.05.097(2019) (2019). 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.05.097(2019) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peng, J. et al. Development and application of a rapid screening and quantification method for multi-class herbicide residues in fishery products using UPLC-Q-Tof-MS/MS: Evidence for prometryn residues in shellfish. Food Control148, 109672. 10.1016/j.foodcont.2023.109672 (2023). 10.1016/j.foodcont.2023.109672 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Valera-Tarifa, N. M., Santiago-Valverde, R., Hernández-Torres, E., Martinez-Vidal, J. L. & Garrido-Frenich, A. Development and full validation of a multiresidue method for the analysis of a wide range of pesticides in processed fruit by UHPLC-MS/MS. Food Chem.315, 126304. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.126304 (2020). 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.126304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abas, K. et al. Effects of plants and biochar on the performance of treatment wetlands for removal of the pesticide chlorantraniliprole from agricultural runoff. Ecol. Eng.175, 106477. 10.1016/j.ecoleng.2021.106477 (2022). 10.1016/j.ecoleng.2021.106477 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Farha, W., Abd El-Aty, A. M., Rahman, M. M., Shin, H. C. & Shim, J. H. An overview on common aspects influencing the dissipation pattern of pesticides: A review. Environ. Monit. Assess.188(12), 693. 10.1007/s10661-016-5709-1 (2016). 10.1007/s10661-016-5709-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu, Y., Lonappan, L., Brar, S. K. & Yang, S. Impact of biochar amendment in agricultural soils on the sorption, desorption, and degradation of pesticides: A review. Sci. Total Environ.645, 60–70. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.07.099 (2018). 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.07.099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liang, L. P. et al. Review of organic and inorganic pollutants removal by biochar and biochar-based composites. Biochar3(3), 255–281. 10.1007/s42773-021-00101-6 (2021). 10.1007/s42773-021-00101-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Qiu, M. et al. Biochar for the removal of contaminants from soil and water: A review. Biochar4, 19. 10.1007/s42773-022-00146-1 (2022). 10.1007/s42773-022-00146-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shaheen, S. M. et al. Wood-based biochar for removal of potentially toxic elements in water and wastewater: A critical review. Int. Mater. Rev.64(4), 216–247. 10.1080/09506608.2018.1473096 (2019). 10.1080/09506608.2018.1473096 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chang, J. et al. Toxicological effects, environmental behaviors and remediation technologies of herbicide atrazine in soil and sediment: A comprehensive review. Chemosphere307, 136006. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2022.136006 (2022). 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2022.136006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang, H. H., Wang, X., Cui, Y. S., Xue, Z. C. & Ba, Y. X. Slow pyrolysis polygeneration of bamboo (Phyllostachys pubescens): Product yield prediction and biochar formation mechanism. Bioresour. Technol.263, 444–449. 10.1016/j.biortech.2018.05.040 (2018). 10.1016/j.biortech.2018.05.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aldas-Vargas, A., Poursat, B. A. J. & Sutton, N. B. Potential and limitations for monitoring of pesticide biodegradation at trace concentrations in water and soil. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol.38(12), 240. 10.1007/s11274-022-03426-x (2022). 10.1007/s11274-022-03426-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhou, X. H. et al. Preparation of iminodiacetic acid-modified magnetic biochar by carbonization, magnetization and functional modification for Cd (II) removal in water. Fuel233, 469–479. 10.1016/j.fuel.2018.06.075 (2018). 10.1016/j.fuel.2018.06.075 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dong, X. et al. Mechanisms of adsorption and functionalization of biochar for pesticides: A review. Ecotox. Environ. Safe.272, 116019. 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2024.116019 (2024). 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2024.116019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khalid, S. et al. A critical review of different factors governing the fate of pesticides in soil under biochar application. Sci. Total Environ.711, 134645. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.134645 (2020). 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.134645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kookana, R. S. The role of biochar in modifying the environmental fate, bioavailability, and efficacy of pesticides in soils: A review. Soil Res.48(6–7), 627–637. 10.1071/SR10007 (2010). 10.1071/SR10007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Deng, H. et al. Influence of biochar amendments to soil on the mobility of atrazine using sorption-desorption and soil thin-layer chromatography. Ecol. Eng.99, 381–390. 10.1016/j.ecoleng.2016.11.021 (2017). 10.1016/j.ecoleng.2016.11.021 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cederlund, H., Boerjesson, E. & Stenstroem, J. Effects of a wood-based biochar on the leaching of pesticides chlorpyrifos, diuron, glyphosate and MCPA. J. Environ. Manag.191, 28–34. 10.1016/j.jenvman.2017.01.004 (2017). 10.1016/j.jenvman.2017.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Su, X. X., Wang, Y. Y., He, Q., Hu, X. B. & Chen, Y. Biochar remediates denitrification process and N2O emission in pesticide chlorothalonil-polluted soil: Role of electron transport chain. Chem. Eng. J.370, 587–594. 10.1016/j.cej.2019.03.195 (2019). 10.1016/j.cej.2019.03.195 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang, T., Ding, T. D., Liu, D. H. & Li, J. Y. Degradation of carbendazim in soil: Effect of sewage sludge-derived biochars. J. Agric. Food Chem.68(12), 3703–3710. 10.1021/acs.jafc.9b07244 (2020). 10.1021/acs.jafc.9b07244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.You, X. W. et al. Biochar decreased enantioselective uptake of chiral pesticide metalaxyl by lettuce and shifted bacterial community in agricultural soil. J. Hazard. Mater.417, 126047. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.126047 (2021). 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.126047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bauer, A. et al. Identification and characterization of pesticide metabolites in Brassica species by liquid chromatography travelling wave ion mobility quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry (UPLC-TWIMS-QTOF-MS). Food Chem.244, 292–303. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.09.131 (2017). 10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.09.131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gong, W. W. et al. Application of biochar: An approach to attenuate the pollution of the chiral pesticide fipronil and its metabolites in leachate from activated sludge - ScienceDirect. Process. Saf. Environ.149, 936–945. 10.1016/j.psep.2021.03.044 (2021). 10.1016/j.psep.2021.03.044 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li, F. et al. Indoxacarb resistance-associated mutation of Liriomyza trifolii in Hainan, China. Pestic. Biochem. Phys.183, 105054. 10.1016/j.pestbp.2022.105054 (2022). 10.1016/j.pestbp.2022.105054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lehmann, J. A handful of carbon. Nature447, 143–144. 10.1038/447143a (2007). 10.1038/447143a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Emma, M. Putting the carbon back: Black is the new green. Nature442(7103), 624–626. 10.1038/442624a (2006). 10.1038/442624a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shi, W. et al. Wheat straw derived biochar with hierarchically porous structure for bisphenol a removal: Preparation, characterization, and adsorption properties. Sep. Purif. Technol.289, 120796–120805. 10.1016/j.seppur.2022.120796 (2022). 10.1016/j.seppur.2022.120796 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lou, L. P. et al. Mechanism of and relation between the sorption and desorption of nonylphenol on black carbon-inclusive sediment. Environ. Pollut.190, 101–108. 10.1016/j.envpol.2014.03.027 (2014). 10.1016/j.envpol.2014.03.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liang, Y., Wei, L. & Hu, J. Residues and dietary intake risk assessments of clomazone, fomesafen, haloxyfop-methyl and its metabolite haloxyfop in spring soybean field ecosystem. Food Chem.360, 129921. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.129921 (2021). 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.129921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim, J. Y. & Lee, M. G. Residue levels of chlorantraniliprole and ethaboxam in different parts of a head-type korean cabbage and reduction of residues in outer leaves by water washing and heat-treatment. Korean J. Pestic. Sci.18(4), 330–335. 10.7585/kjps.2014.18.4.330 (2014). 10.7585/kjps.2014.18.4.330 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Manikandan, R., Karthikeyan, G. & Raguchander, T. Soil proteomics for exploitation of microbial diversity in Fusarium wilt infected and healthy rhizosphere soils of tomato. Physiol. Mol. Plant. P.100, 185–193. 10.1016/j.pmpp.2017.10.001 (2017). 10.1016/j.pmpp.2017.10.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Martin, S. M., Kookana, R. S., Van Zwieten, L. & Krull, E. Marked changes in herbicide sorption-desorption upon ageing of biochars in soil. J. Hazard. Mater.231, 70–78. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2012.06.040 (2011). 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2012.06.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Qi, P. P. et al. Fabrication of poly-dopamine-modified magnetic nanomaterial and development of integrated QuEChERS method for 122 pesticides residue analysis in fruits. J. Chrom. A1708, 464336. 10.1016/j.chroma.2023.464336 (2023). 10.1016/j.chroma.2023.464336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhao, H. Y. et al. Development of rapid low temperature assistant modified QuEChERS method for simultaneous determination of 107 pesticides and relevant metabolites in animal lipid. Food Chem.395, 133606. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2022.133606 (2022). 10.1016/j.foodchem.2022.133606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu, Y. C. et al. Effects of pH and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon pollution on thaumarchaeotal community in agricultural soils. J. Soil Sediment.16(7), 1960–1969. 10.1007/s11368-016-1390-9 (2016). 10.1007/s11368-016-1390-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang, T. T. et al. Effect of biochar amendment on the bioavailability of pesticide chlorantraniliprole in soil to earthworm. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf.83, 96–101. 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2012.06.012 (2012). 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2012.06.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen, J. et al. Pyrosequencing reveals bacterial communities and enzyme activities differences after application of novel chiral insecticide Paichongding in aerobic soils. Appl. Soil Ecol.112, 18–27. 10.1016/j.apsoil.2016.12.007 (2017). 10.1016/j.apsoil.2016.12.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stackebrandt, E. & Goebel, B. M. Taxonomic note: A place for DNA-DNA reassociation and 16S rRNA sequence analysis in the present species definition in bacteriology. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol.44, 846–849. 10.1099/00207713-44-4-846 (1994). 10.1099/00207713-44-4-846 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Miller, G. E. et al. Lower neighborhood socioeconomic status associated with reduced diversity of the colonic microbiota in healthy adults. PLoS One11(2), e0148952. 10.1371/journal.pone.0148952 (2016). 10.1371/journal.pone.0148952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fracchia, L., Dohrmann, A. B., Martinotti, M. G. & Tebbe, C. C. Bacterial diversityin a fifinished compost and vermicompost: Differences revealed by cultivation independent analyses of PCR-amplifified 16S rRNA genes. Appl. Microbiol. Biot.71, 942–952. 10.1007/s00253-005-0228-y (2006). 10.1007/s00253-005-0228-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu, J. J. et al. Diversity and distribution patterns of acidobacterial communities in the black soil zone of northeast China. Soil Biol. Biochem.95, 212–222. 10.1016/j.soilbio.2015.12.021 (2016). 10.1016/j.soilbio.2015.12.021 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Campos, P. et al. Chemical, physical and morphological properties of biochars produced from agricultural residues: Implications for their use as soil amendment. Waste Manag.105, 256–267. 10.1016/j.wasman.2020.02.013 (2020). 10.1016/j.wasman.2020.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Malhat, F., Badawy, H. M., Barakat, D. A. & Saber, A. N. Residues, dissipation and safety evaluation of chromafenozide on strawberry under open field conditions. Food Chem.152, 18–22. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.11.110 (2014). 10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.11.110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fang, S. H., Zhu, L. Y., Liu, L., Liu, Z. T. & Zhang, Y. H. Mutual impacts of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) and earthworms (Eisenia fetida) on the bioavailability of perfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) in soil. Environ. Pollut.184, 495–501. 10.1016/j.envpol.2013.09.032 (2014). 10.1016/j.envpol.2013.09.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Petkowicz, C. L. O. & Williams, P. A. Pectins from food waste: Characterization and functional properties of a pectin extracted from broccoli stalk. Food Hydrocoll.107, 105930. 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2020.105930 (2020). 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2020.105930 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mandal, A., Singh, N. & Purakayastha, T. J. Characterization of pesticide sorption behaviour of slow pyrolysis biochars as low cost adsorbent for atrazine and imidacloprid removal. Sci. Total Environ.577, 376–385. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.10.204 (2017). 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.10.204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shono, T., Zhang, L. & Scott, J. G. Indoxacarb resistance in the house fly, Musca domestica. Pest. Biochem. Physiol.80(2), 106–112. 10.1016/j.pestbp.2004.06.004 (2004). 10.1016/j.pestbp.2004.06.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mendes, K. F. et al. Cow bone char as a sorbent to increase sorption and decrease mobility of hexazinone, metribuzin, and quinclorac in soil. Geoderma343, 40–49. 10.1016/j.geoderma.2019.02.009 (2019). 10.1016/j.geoderma.2019.02.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang, D. et al. Deposition, dissipation, metabolism, and dietary risk assessment of chlorothalonil on pakchoi. J. Food Compos. Anal.134, 106521. 10.1016/j.jfca.2024.106521 (2024). 10.1016/j.jfca.2024.106521 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yu, Y. et al. Simultaneous determination of rimsulfuron and haloxyfop-P-methyl and its metabolite haloxyfop in tobacco leaf by LC-MS/MS. J. Aoac International102(5), 1632–1640. 10.1093/jaoac/102.5.1632 (2019). 10.1093/jaoac/102.5.1632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chaves, A., Shea, D. & Cope, W. G. Environmental fate of chlorothalonil in a Costa Rican banana plantation. Chemosphere69(7), 1166–1174. 10.1016/j.Chemosphere (2007). 10.1016/j.Chemosphere [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sandermann, H. Higher plant metabolism of xenobiotics: The ‘green liver’ concept. Pharmacogenet4(5), 225–241. 10.1097/00008571-199410000-00001 (1994). 10.1097/00008571-199410000-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Casida, J. E. Neonicotinoid metabolism: Compounds, substituents, pathways, enzymes, organisms, and relevance. J. Agric. Food Chem.59(7), 2923–2931. 10.1021/jf102438c (2011). 10.1021/jf102438c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Campos, R., Pinheiro, D. & Britto-Júnior, J. Quantification of 6-nitrodopamine inKrebs-Henseleit’s solution by LC-MS/MS for the assessment of its basal release from Chelonoidis carbonaria aortae in vitro. J. Chromatogr. B1173, 122668. 10.1016/j.jchromb.2021.122668 (2021). 10.1016/j.jchromb.2021.122668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Li, Y. et al. Effects of biochars on the fate of acetochlor in soil and on its uptake in maize seedling. Environ. Pollut.241, 710–719. 10.1016/j.envpol.2018.05.079 (2018). 10.1016/j.envpol.2018.05.079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jin, J. W. et al. Influence of pyrolysis temperature on properties and environmental safety of heavy metals in biochars derived from municipal sewage sludge. J. Hazard. Mater.320(15), 417–426. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2016.08.050 (2016). 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2016.08.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Li, H. et al. Machine learning assisted predicting and engineering specific surface area and total pore volume of biochar. Bioresour. Technol.369, 128417. 10.1016/j.biortech.2022.128417369 (2023). 10.1016/j.biortech.2022.128417369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wu, C. et al. Sorption, degradation and bioavailability of oxyfluorfen in biochar-amended soils. Sci. Total. Environ.658, 8–94. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.12.059 (2019). 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.12.059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cheng, F. & Li, X. W. Preparation and application of biochar-based catalysts for biofuel production. Catalysts8(9), 346. 10.3390/catal8090346 (2018). 10.3390/catal8090346 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wang, X. B., Zhou, W., Liang, G. Q., Song, D. L. & Zhang, X. Y. Characteristics of maize biochar with different pyrolysis temperatures and its effects on organic carbon, nitro gen and enzymatic activities after addition to fluvo-aquic soil. Sci. Total Environ.538, 137–144. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.02.053 (2015). 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.02.053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jablonowski, N. D. et al. Biochar-mediated 14C-atrazine mineralization in atrazine adapted soils from Belgium and Brazil. J. Agric. Food Chem.61, 512–516. 10.1021/jf303957a (2013). 10.1021/jf303957a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Leng, L. J. et al. An overview on engineering the surface area and porosity of biochar. Sci. Total. Environ.763, 144204. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.144204 (2021). 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.144204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tang, X. Y. et al. Use of Fe-impregnated biochar to efficiently sorb chlorpyrifos, reduce uptake by Allium fistulosum L., and enhance microbial community diversity. J. Agric. Food Chem.65(26), 5238–5243. 10.1021/acs.jafc.7b01300 (2017). 10.1021/acs.jafc.7b01300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yavari, S., Sapari, N. B., Malakahmad, A. & Yavari, S. Degradation of imazapic and imazapyr herbicides in the presence of optimized oil palm empty fruit bunch and rice husk biochars in soil. J. Hazard. Mater.366, 636–642. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2018.12.022 (2019). 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2018.12.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.You, X. et al. Effect of biochar on the enantioselective soil dissipation and lettuce uptake and translocation of the chiral pesticide metalaxyl in a contaminated soil. J. Agric. Food Chem.67(49), 13550–13557. 10.1021/acs.jafc.9b05559 (2019). 10.1021/acs.jafc.9b05559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Li, W. J. et al. Rhizosphere effect alters the soil microbiome composition and C, Ntransformation in an arid ecosystem. Appl. Soil Ecol.170, 104296. 10.1016/j.apsoil.2021.104296 (2022). 10.1016/j.apsoil.2021.104296 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Vendruscolo, E. G. G., Mesa, D. & Souza, E. M. D. Corn rhizosphere microbial community in different long term soil management systems. Appl. Soil Ecol.172, 104339. 10.1016/j.apsoil.2021.104339 (2022). 10.1016/j.apsoil.2021.104339 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.D’Orazio, V. & Nicola, S. Spectroscopic properties of humic acids isolated from the rhizosphere and bulk soil compartments and fractionated by size-exclusion chromatography. Soil Biol. Biochem.41(9), 1775–1781. 10.1016/j.soilbio.2008.02.001 (2009). 10.1016/j.soilbio.2008.02.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zhang, B. & Jiao, W. T. Biochar facilitated bacterial reduction of Cr (VI) by Shewanella Putrefaciens CN32: Pathways and surface characteristics. Environ. Res.214, 113971. 10.1016/j.envres.2022.113971 (2022). 10.1016/j.envres.2022.113971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Liu, J. W. et al. Preparation, environmental application and prospect of biochar-supported metal nanoparticles: A review. J. Hazard. Mater.388, 122026. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.122026 (2020). 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.122026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhu, X., Chen, B., Zhu, L. & Xing, B. Effects and mechanisms of biochar-microbe interactions in soil improvement and pollution remediation: A review. Environ. Pollut.227, 98–115. 10.1016/j.envPol.2017.04.032 (2017). 10.1016/j.envPol.2017.04.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Qin, K., Dong, X. J., Jifon, J. & Leskovar, D. I. Rhizosphere microbial biomass is affected by soil type, organic and water inputs in a bell pepper system. Appl. Soil Ecol.138, 80–87. 10.1016/j.apsoil.2019.02.024 (2019). 10.1016/j.apsoil.2019.02.024 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sun, S., Sidhu, V., Rong, Y. H. & Zheng, Y. Pesticide pollution in agricultural soils and sustainable remediation methods: A review. Curr. Pollut. Rep.4, 240–250. 10.1007/s40726-018-0092-x (2018). 10.1007/s40726-018-0092-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article and its supplementary information files.