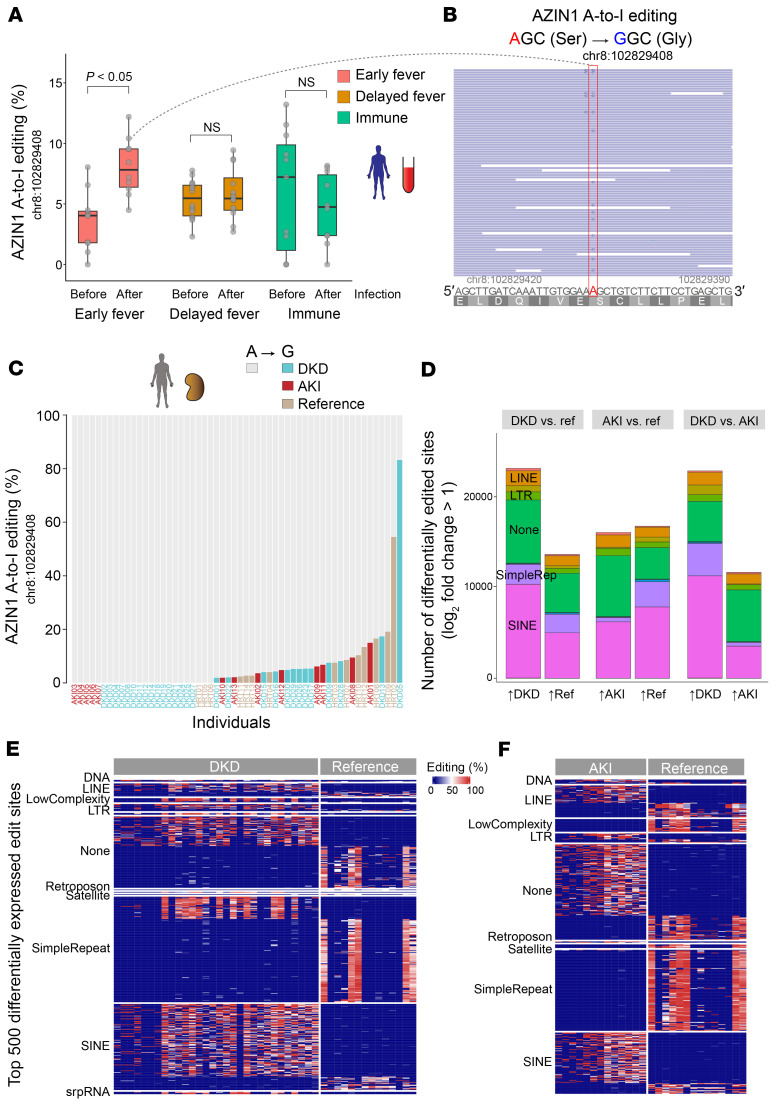

Figure 1. AZIN1 A-to-I editing status in non-cancerous diseases in humans.

(A) Distribution of AZIN1 A-to-I editing rates (percent of edited reads over total reads) in prospectively collected blood from male children aged 6–11 years, before and after Plasmodium falciparum malaria infection. Individuals were classified as early fever (symptomatic and first-time infection), delayed fever (asymptomatic and first-time infection, subsequently developing malarial symptoms), and immune (infected but never developing symptoms). (B) Representative read coverage near the AZIN1 editing site for one sample. Note that inosine is sequenced as guanosine. The human AZIN1 gene is encoded on the minus strand, hence the T-to-C mutation, not A-to-G, in the coverage track. Light-blue-colored reads (F2R1 paired-end orientation) indicate the proper directionality of reads mapped to the minus strand. (C) Distribution of AZIN1 A-to-I editing rates in kidney biopsies with a pathology diagnosis of diabetic kidney disease (DKD), acute kidney injury (AKI), or reference nephrectomy samples. Each column represents one sample. (D) Stacked bar chart summarizing total numbers of differentially expressed A-to-I editing sites genome-wide under the indicated conditions. For each comparison, editing sites are divided on the x axis based on the direction of fold change. For example, in the DKD versus reference comparison, approximately 20,000 sites are more edited in DKD, whereas approximately 10,000 sites are more edited in reference nephrectomy samples. (E) Heatmap displaying the top 500 differentially expressed A-to-I editing sites between diabetic nephropathy and reference nephrectomy samples. The differentially expressed sites are categorized based on repeat classes. (F) Comparison between AKI biopsies and reference nephrectomy samples.