Abstract

Although chromium trihalides are widely regarded as a promising class of two-dimensional magnets for next-generation devices, an accurate description of their electronic structure and magnetic interactions has proven challenging to achieve. Here, we quantify electronic excitations and spin interactions in CrX3 (X = Cl, Br, I) using embedded many-body wavefunction calculations and fully generalized spin Hamiltonians. We find that the three trihalides feature comparable d-shell excitations, consisting of a high-spin 4A2 ground state lying 1.5–1.7 eV below the first excited state 4T2 (). CrCl3 exhibits a single-ion anisotropy Asia = − 0.02 meV, while the Cr spin-3/2 moments are ferromagnetically coupled through bilinear and biquadratic exchange interactions of J1 = − 0.97 meV and J2 = − 0.05 meV, respectively. The corresponding values for CrBr3 and CrI3 increase to Asia = −0.08 meV and Asia= − 0.12 meV for the single-ion anisotropy, J1 = −1.21 meV, J2 = −0.05 meV and J1 = −1.38 meV, J2 = −0.06 meV for the exchange couplings, respectively. We find that the overall magnetic anisotropy is defined by the interplay between Asia and Adip due to magnetic dipole–dipole interaction that favors in-plane orientation of magnetic moments in ferromagnetic monolayers and bulk layered magnets. The competition between the two contributions sets CrCl3 and CrI3 as the easy-plane (Asia + Adip >0) and easy-axis (Asia + Adip <0) ferromagnets, respectively. The differences between the magnets trace back to the atomic radii of the halogen ligands and the magnitude of spin–orbit coupling. Our findings are in excellent agreement with recent experiments, thus providing reference values for the fundamental interactions in chromium trihalides.

Subject terms: Magnetic properties and materials, Two-dimensional materials

Introduction

The advent of two-dimensional (2D) magnets has created new opportunities to explore and manipulate spin interactions in the ultimate limit of atomic thickness, holding promise for an array of nanoscale applications ranging from magneto-optoelectronics to quantum information1–4. In these 2D magnets, the non-vanishing critical temperature originates from the magnetic anisotropy, which is key to preserving long-ranged magnetic order against thermal fluctuations, as explained by the theorems of Mermin–Wagner5 and Hohenberg6. Within the rapidly expanding class of ultrathin magnets, layered chromium trihalides of general formula CrX3 (X = Cl, Br, I)7 are among the most discussed members by virtue of their versatile magnetic properties that can be engineered via, e.g., atomic thickness8, stacking configuration9,10, electrostatic gating11,12, lattice deformations13–15, defects incorporation16,17, or light irradiation18. Such tunability is key for the construction of new energy-efficient spin-based devices.

In the recent years, a flurry of theoretical investigations on this family of materials established the important role played by t2g–eg interactions19, ligand p orbitals20,21 and stacking sequence22 in stabilizing the ferromagnetic order. The insulating chromium trihalides realize highly localized magnetic moments close to 3 μB, corresponding to an S = 3/2 system23, with short-range superexchange interactions, as well as local magnetic anisotropy. The latter allows this family of 2D materials to overcome the Mermin–Wagner theorem and to establish long-range magnetic order24. Inelastic neutron scattering experiments on CrI3 showed ≈4 meV gap opening between the two magnon branches25. Chen et al.25 argued that the gap originates from the Dzyaloshinskii–Moriya (DM) interaction26–28 and predicted an unusually large dominant DM interaction from the fitting of magnon spectra. However, the nearest-neighbor (NN) DM vector in CrI3 is not allowed by symmetry and only the next NN DM interaction is finite. Alternatively, such a gap was argued to result from significant Kitaev interactions (symmetric anisotropic exchange)29. The Kitaev term is allowed by symmetry, but similar to DM interaction, it also originates from spin–orbit coupling (SOC) and is usually quite small in 3d materials. The heavier ligands do contribute to SOC, but the presence of such dominant anisotropic interaction is still under debate as the magnetic interaction parameters reported from various experiments and theoretical calculations differ7,29–31. Further studies have also discussed higher-order interactions (biquadratic exchange) and lattice defects as the origin of the gap32,33.

Despite the rapidly growing interest in CrX3 magnets, an accurate description of magnetic interactions as well as electronic excitations is still needed. On the one hand, high-resolution measurements based on soft X-ray spectroscopies, which are instrumental to accessing electronic excitations, are challenging to accomplish and tedious to interpret34. On the other hand, recent experiments assessing spin interactions are mainly limited to isotropic Heisenberg exchange couplings, the strength of which remains debated since reported values differ by upto one order of magnitude7,29,35. From the theoretical point of view, earlier studies primarily resort to density-functional methods, which are inherently inadequate to cope with both excited and correlated electronic states. Such a drawback was shown to be particularly severe when dealing with chromium trihalides and other 2D magnets, where, depending on the adopted exchange-correlation approximation and computational scheme, the strength of the calculated magnetic interactions spreads over a wide energy window7,36,37. This calls for a rigorous and unambiguous account of electron-electron effects in order to achieve a detailed comprehension of CrX3 magnets.

In this work, we present a comparative investigation of electronic excitations and spin interactions in two-dimensional CrX3 (X = Cl, Br, I) using post-Hartree-Fock methods, namely the complete-active-space self-consistent-field (CASSCF) and multireference configuration interaction (MRCI) methodologies (see “Methods”), that are arguably the most accurate and rigorous approach to treat electronic correlations. First, we determine the d-shell multiplet structures, which allows us to offer an unambiguous interpretation to recent X-ray spectroscopic measurements. Next, we quantify the strength of dominant magnetic interactions, including single-ion anisotropy, g-factors, and exchange couplings, using a fully generalized spin Hamiltonian. Altogether, our findings establish a theoretical ground to recent spectroscopic observations, thus providing a quantitative understanding of the microscopic physics in chromium trihalides from a quantum chemical perspective.

Results

We begin our work by establishing the Cr3+ ground state and d-shell excitations in CrX3. In Table 1, we give the multiplet structure, as obtained at the CASSCF and MRCI levels using the one-site model shown in Fig. 1b. Additional details of our calculations are provided in Supplementary Note 1. According to the crystal-field theory, the octahedral environment encaging each Cr3+ ion lifts the energy degeneracy of the d-orbital manifold, giving rise to a lower-lying triply degenerate t2g and a higher-lying doubly degenerate eg group of levels. The ground state of the halides is the high-spin singlet state 4A2 dominated by the () configuration, in compliance with Hund’s rule of maximum multiplicity. The half-filled t2g subshell renders each Cr3+ ion a spin-3/2 center, in line with the magnetization saturation of 3 μB observed in SQUID magnetometry measurements8. The first excited state 4T2 consists of dominant contributions from the configuration that comprises a pair of electrons in the t2g orbitals and a single electron in the eg orbitals. In the case of CrCl3, this leads to a splitting between the t2g and eg orbitals as large as ~1.6 eV at CASSCF level, which slightly increases to ~1.7 eV at the MRCI level. Consistently with the order of the ligand strength subsumed in the spectrochemical series, such a splitting decreases in energy as the size of the ligand increases (that is, moving from CrCl3 to CrI3). In both CrBr3 and CrI3 the calculated splitting is ~1.5 eV at the MRCI level of theory. The reason for this traces back to the more extended electron density in the heavier halogen atom and the consequently longer transition metal-to-ligand distances. Indeed, the t2g–eg splitting is sensitive to structural deformations of the octahedral cage and increases (decreases) when the crystal is subjected to moderate tensile (compressive) in-plain lattice strain, as we show for the representative case of CrCl3 in Supplementary Table 1.

Table 1.

Relative energies of the 3d3 multiplet structure of Cr3+ ions in CrX3 (X = Cl, Br, I), as obtained from CASSCF and MRCI calculations

| CrCl3 | CrBr3 | CrI3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CASSCF | MRCI | CASSCF | MRCI | CASSCF | MRCI | |

| 4A2 () | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 4T2 () | 1.57, 1.58, 1.61 | 1.67, 1.68, 1.72 | 1.38, 1.59, 2.00 | 1.46, 1.66, 2.05 | 1.44, 1.56, 1.58 | 1.48, 1.59, 1.61 |

| 2E () | 2.36, 2.36 | 2.22, 2.22 | 1.92, 2.19 | 1.77, 2.10 | 2.32, 2.33 | 2.16, 2.17 |

| 4T1 () | 2.51, 2.53, 2.60 | 2.50, 2.52, 2.59 | 2.51, 2.59, 2.95 | 2.49, 2.62, 2.96 | 2.48, 2.50, 2.52 | 2.39, 2.49, 2.51 |

| 2T1 () | 2.45, 2.47, 2.48 | 2.31, 2.33, 2.34 | 2.36, 2.45, 2.49 | 2.22, 2.32, 2.37 | 2.39, 2.39, 2.42 | 2.26, 2.30, 2.31 |

| 2T1 () | 3.30, 3.31, 3.33 | 3.03, 3.05 | 3.32, 3.41, 3.45 | 3.23, 3.25, 3.26 | 3.23, 3.29, 3.31 | 2.95, 3.02, 3.02 |

| 2A1 () | 3.56 | 3.47 | 3.56 | 3.45 | 3.47 | 3.39 |

| 2T1 () | 3.83, 3.84, 3.85 | 3.76, 3.77, 3.78 | 4.06, 4.32, 4.80 | 3.94, 4.24, 4.73 | 3.68, 3.70, 3.71 | 3.59, 3.61, 3.63 |

| 4T1 () | 4.13, 4.15, 4.16 | 4.05, 4.07, 4.08 | 3.71, 3.85, 3.89 | 3.56, 3.74, 3.78 | 3.90, 4.01, 4.04 | 3.80, 4.10, 4.12 |

Energies are given in eV and referenced to the ground state. Occupations in parentheses indicate the dominant configuration.

Fig. 1. Crystal structure and embedding models of chromium trihalides.

a Crystal structure of monolayer CrX3 (X = Cl, Br, I). Blue and orange spheres represent chromium and halogen atoms, respectively. b Embedding model used in the determination of the multiplet structures and intra-site magnetic interactions. c Embedding model used in the determination of the inter-site magnetic interactions. In panels (b, c), dark (light) colors indicate the atoms that are treated with many-body (Hartree–Fock) wavefunctions. The models are embedded in an array of points charges (not shown) to reproduce the crystalline environment and ensure charge neutrality.

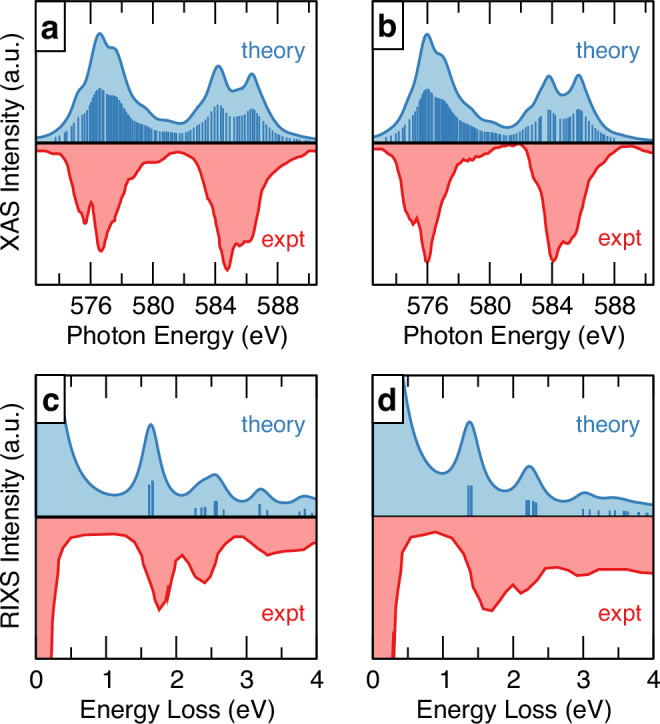

We gain theoretical insight into the recent X-ray spectroscopy experiments34 probing electronic excitations in CrX3. To that end, we simulate the Cr L3,2-edge X-ray absorption spectra (XAS) and L3-edge resonant inelastic X-ray scattering (RIXS) spectra of CrCl3 and CrI3 using CASSCF calculations, and the minimal finite-size model shown in Supplementary Fig. 1a. The resulting d-shell excitation energies of the Cr3+ ion are listed in Supplementary Tables 2 and 3. We consider the same scattering geometry used in recent experiments by Shao et al.34 and given in Supplementary Fig. 1b. Additional details of these calculations are given in Supplementary Note 2. We remark that similar computational schemes have been validated against experimental measurements for diverse magnetic compounds38–40. The simulated RIXS and XAS spectra of CrCl3 and CrI3 are shown in Fig. 2. The excellent agreement between the theoretical and experimental spectra allows us to assign the electronic excitations observed. In Fig. 2a, b, the L-edge absorption process involves a Cr 2p electron that is promoted to the empty 3d orbitals (2p → 3p), leading to the final 2p53d4 configuration (2p63d3 → 2p53d4). This transition results in the two main features in the XAS spectra located at incident photon energies of 574–580 eV and 582–588 eV, which correspond to the Cr L3- and L2-edges, respectively. These two features are separated by ~9 eV due to spin–orbit interactions in the presence of the 2p core-hole in the XAS final states41. On the other hand, spin–orbit interactions weakly affect the Cr 3d3 valence states; see Supplementary Tables 2 and 3.

Fig. 2. X-ray spectra of chromium trihalides.

Simulated and experimental X-ray absorption spectra (XAS) of a CrCl3 and b CrI3. Simulated and experimental resonant X-ray inelastic scattering (RIXS) spectra of c CrCl3 and d CrI3. Vertical lines in the simulated spectra mark the excitation energies. The experimental spectra are digitized from ref. 34. The simulated XAS spectra were shifted to match the position in energy of the highest intensity peak in the experimental spectra. Notice the different order of intensity between theory and experiment observed for the L3- and L2-edges is due to undesired self-absorption effects in experimental measurements.

Due to the core-hole broadening in L-edge XAS, the on-site d-d excitations are not well-resolved or determined by comparing our calculations with the experimental XAS spectra. We further simulate the L3-edge RIXS spectra to resolve the otherwise elusive d-shell excitations experimentally observed. This is accomplished by setting the incident energy, Ein, at the maximum intensity of L3-edge XAS, i.e., Ein = 576.6 eV for CrCl3 and Ein= 576.0 eV for CrI3, and determining the RIXS intensities of π-polarization at incident angle 50°, similarly to experiments. As we restrict ourselves to on-site d-shell excitations and neglect ligand-metal charge transfer states, we focus on energy losses lower than 4 eV. The simulated RIXS spectra are shown in Fig. 2c, d and, in analogy with experiments, exhibit three main features. For CrCl3, the first excitation peak at ~1.6 eV corresponds to the t2g−eg transitions associated with spin quartet states 4T2(). The second excitation peak occurring in the 2.2–2.7 eV energy range is dominated by the 4T1 () states, with a slight spectral weight contribution from the 2E () and 2T1 () excited states at 2.3–2.4 eV. The feature arising at ~3.2 eV is related to the 2T2 () states. The remaining higher energy loss feature from 3.5 to 4.0 eV is attributed to the t2g − eg transitions associated with spin doublet states (2A, 2T1, and 2T2). Similarly, for CrI3 the first excitation peak at ~1.5 eV is assigned to the t2g − eg transitions associated with spin quartet states 4T2 (). As compared to CrCl3, however, the first excitation peak shift to lower energy loss by ~0.2 eV, both in the simulated and experimental spectra. The second feature at ~2.3 eV is contributed by the 4T1 () and 2T1 () states. At energy losses larger than 2.5 eV, the feature becomes broad and the t2g–eg transitions associated with spin doublet states are dominated.

Next, we focus on magnetic interactions in CrX3 materials. We write the effective spin Hamiltonian as

| 1 |

where encodes the contribution of the interactions within sites of spin , while describes the coupling between the ith and jth nearest-neighbor sites bearing spins and , respectively. The intra-site contribution takes the form

| 2 |

where is the single-ion anisotropy tensor and is the g-tensor in the Zeeman term that emerges upon the application of an external magnetic field . The inter-site contribution reads

| 3 |

with J1 and J2 being the bilinear and biquadratic isotropic exchange couplings, respectively, and the symmetric anisotropic tensor. We remark that the nearest-neighbor Dzyaloshinskii–Moriya interaction vanishes due to the centrosymmetric crystal structure of CrX327. Assuming a local Kitaev frame where the z axis is perpendicular to the Cr2 X2 plaquette for each Cr–Cr bond42,43, can be expressed as

| 4 |

where K is the Kitaev interaction parameter.

We determine the intra-site interactions appearing in , i.e., the single-ion anisotropy and the g-tensor, relying on the one-site model shown in Fig. 1b. Further details of our calculations are given in Supplementary Note 1. Our results are presented in Table 2. The single-ion anisotropy quantifies the zero-field splitting of the ground state that stems from spin–orbit and crystal-field effects. To assess this quantity, we rely on the methodology developed in ref. 44 taking advantage of the multiplet structures listed in Table 1 and corresponding wavefunctions. In brief, the mixing of the low-lying 4A2 states with the higher-lying states is treated perturbatively and the spin–orbit wavefunctions related to the high-spin configuration are projected onto the space spanned by the states. The orthonormalized projections of the low-lying quartet wavefunctions and the corresponding eigenvalues Ek are used to construct the effective Hamiltonian . A one-to-one correspondence between and the model Hamiltonian leads to the tensor (listed in Supplementary Table 4), which is then diagonalized and the axial parameter Asia obtained as . At the MRCI level of theory, we find Asia = −0.03 meV for CrCl3, −0.08 meV for CrBr3 and −0.12 meV for CrI3. The negative sign of the axial parameter corresponds an easy axis of magnetization. In all the three cases, we find an easy axis pointing perpendicular to the honeycomb plane. The considerably large magnitude of the single-ion anisotropy in CrI3 compared to CrCl3 reflects the strong spin–orbit interactions inherent to the heavier ligands45.

Table 2.

Intra-site magnetic interactions in CrX3 (X = Cl, Br, I), i.e., single-ion anisotropy axial parameter Asia, along with the in-plane (gxx, gyy) and out-of-plane (gzz) components of the g-tensor, as obtained from CASSCF and MRCI calculations

| CrCl3 | CrBr3 | CrI3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CASSCF | MRCI | CASSCF | MRCI | CASSCF | MRCI | |

| Asia (meV) | −0.02 | −0.03 | −0.07 | −0.08 | −0.11 | −0.12 |

| gxx = gyy | 1.44 | 1.45 | 1.86 | 1.86 | 1.91 | 1.92 |

| gzz | 1.46 | 1.47 | 1.87 | 1.88 | 1.92 | 1.93 |

Another important contribution to the anisotropy originates from magnetic dipole–dipole interactions that are not accounted for in the electronic structure calculations46,47. This contribution, however, should not be neglected for monolayer as well as layered bulk magnetic materials as a result of magnetic shape anisotropy. The magnetic dipolar anisotropy for any given lattice can be determined as:

| 5 |

where is spin at site i(j) and is the vector connecting sites i and j. This expression can be rewritten in a form that is similar to Eq. (2):

| 6 |

where is a tensor. The matrix elements (α, β = x, y, z) are computed as

| 7 |

with being the unit vector at site i pointing along α = x, y, z. In order to avoid summing over an infinite number of pairs of spins we used the approach described in ref. 48, which is based on performing summation upto a certain cutoff distance between the spins and carefully evaluating the convergence of the matrix elements of with respect to this cutoff. Supplementary Fig. 2 presents the converged values of for the x, y, z orientation of magnetic moments in CrCl3, CrBr3 and CrI3. Similar to the single-ion anisotropy axial parameter, we obtain the axial parameter for the magnetic dipolar anisotropy . The Adip parameters for all three chromium trihalides are listed in Table 3. The magnitudes of Adip decrease along the series as a result of a slight increase of the in-plane lattice constants and are larger for monolayers as compared to bulk materials. Most importantly, these values are positive, which is consistent with the expectation of the demagnetization energy being lower for the in-plane magnetization in slab geometries, and are of magnitude comparable to that of single-ion anisotropy. This allows us to conclude that the overall magnetic anisotropy in chromium trihalides is dictated by the interplay between these two competing contributions. In the heavier CrI3 single-ion anisotropy dominates (Asia + Adip = −67 μeV) establishing as the (out-of-plane) easy-axis ferromagnet, while the opposite is true for CrCl3 (Asia + Adip = 54 μeV) that we conclude to be an easy-plane ferromagnet. The case of CrBr3 is borderline with the marginally larger contribution from single-ion anisotropy, which establishes this material as an easy-axis magnet with weak anisotropy. Our findings are in full agreement with recent experiments8,23,49,50.

Table 3.

Comparison of the dipolar anisotropy parameter Adip and the single-ion anisotropy parameter Asia obtained from MRCI calculations for bulk CrX3 (X = Cl, Br, I)

| CrCl3 | CrBr3 | CrI3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Asia (μeV) | −31.4 | −81.1 | −124.2 |

| Adip (μeV) | 85.2 | 75.5 | 57.3 |

The negative sign indicates that the out-of-plane spin moments are favored. The shape anisotropy parameter Adip for monolayer CrX3 (X = Cl, Br, I) approximately doubles in magnitude as compared to the bulk, and attains values of 144 μeV, 121 μeV, 94 μeV for chloride, bromide and iodide, respectively.

There is, however, one subtle point51. The transition from Eqs. (5) to (6) is rigorous only for homogeneous distribution of magnetization plus ellipsoidal shape of the sample47. The spin-wave spectrum for ferromagnets with an easy-plane anisotropy and for those with dipole–dipole interactions are essentially different, and for the latter the spin-wave energy tends to zero at zero wave vector much slower46,51. Also, due to the long-range character of dipole–dipole interactions the formal conditions of applicability of Mermin–Wagner–Hohenberg theorem are not fulfilled. Maleev suggested51 that in 2D ferromagnets with dipole–dipole interactions one has the true long-range order at low enough temperatures, contrary to the “almost broken symmetry” of Berezinskii–Kosterlitz–Thouless type52,53 for the easy-plane ferromagnets. Later this suggestion was confirmed within the framework of self-consistent spin-wave theory54. This means that for all three CrX3 (X = Cl, Br, I) ferromagnets, one can expect the true long-range ordered state below the Curie temperature.

Of crucial importance to understand the response of CrX3 to external magnetic fields is the g-tensor. We determine this quantity following the scheme devised in ref. 55. Many-body wavefunction calculations enable to extract the matrix elements of the total magnetic moment operator in the basis of the spin–orbit coupled eigenstates , where is the angular momentum operator, the spin operator, and ge the free-electron Landé factor for a given magnetic site. The Zeeman Hamiltonian in terms of total magnetic moment, , is then mapped onto the Zeeman contribution to given in Eq. (2). To obtain the g-factors, we use an active space that includes all five d orbitals of the Cr3+ ion averaged over five quartets and seven doublets. The g-factors at both CASSCF and MRCI level of theory are listed in Table 2. These values match those determined in recent electron spin resonance experiments18, that is 1.49 and 1.96 for CrCl3 and CrI3, respectively. The slight anisotropy (~1%) of the calculated g-tensors arises from the mild trigonal distortion of the octahedral cage occurring in CrX3 ferromagnets.

Finally, we determine the inter-site interactions appearing in the spin Hamiltonian , i.e., the bilinear and biquadratic isotropic exchange couplings J1 and J2, respectively, together with the symmetric anisotropic tensor . We rely on the two-site model shown in Fig. 1c and give further technicalities of our calculations in Supplementary Note 3. We map the resulting ab initio Hamiltonian onto the anisotropic biquadratic model Hamiltonian given in Eq. (3), which involves sixteen spin–orbit states corresponding to one septet, one quintet, one triplet, and a singlet. The mapping is accomplished according to the procedure described in ref. 56. The resulting magnetic interactions are listed in Table 4. Additional results obtained on a simpler isotropic bilinear Hamiltonian are provided in Supplementary Table 5.

Table 4.

Inter-site magnetic interactions in CrX3 (X = Cl, Br, I), i.e., bilinear (J1) and biquadratic (J2) exchange couplings, along with the off-diagonal (Γxy, Γyz, Γzx) and Kitaev (K) parameters comprised in the symmetric anisotropic tensors, as obtained from the CASSCF and MRCI calculations

| CrCl3 | CrBr3 | CrI3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CASSCF | MRCI | CASSCF | MRCI | CASSCF | MRCI | |

| J1 (meV) | −0.64 | −0.97 | −0.61 | −1.21 | −0.60 | −1.38 |

| J2 (meV) | −0.04 | −0.05 | −0.05 | −0.05 | −0.06 | −0.06 |

| Γxy (meV) | −1.2 × 10−4 | −2.1 × 10−4 | −6.9 × 10−4 | −0.8 × 10−3 | −1.2 × 10−3 | −4.2 × 10−4 |

| Γyz = − Γzx (meV) | −1.3 × 10−5 | −0.8 × 10−4 | −6.9 × 10−4 | −0.9 × 10−3 | −1.1 × 10−4 | −3.1 × 10−4 |

| K (meV) | −1.7 × 10−4 | −1.1 × 10−4 | −8.2 × 10−3 | −0.01 | −9.3 × 10−3 | −0.05 |

The dominant term among the inter-site interactions is the bilinear isotropic exchange coupling J1, the negative sign of which indicates a parallel spin interaction between the spin-3/2 centers. This is fully consistent with the observations of an intra-layer ferromagnetic order probed by the magneto-optical Kerr effect in CrI38 and temperature-dependence transport measurements in CrCl349. The strength of J1 is largely dependent on whether the CASSCF or MRCI level of theory is adopted due to the different types of exchange mechanisms involved in these approaches. At the CASSCF level, the main mechanism is the direct exchange between the transition metal atoms. As a result, J1 is slightly larger in CrCl3 and CrBr3 as compared to CrI3 as a consequence of the shorter distance between the Cr3+ ions in the former trihalides. At the MRCI level, however, the superexchange pathway through the non-magnetic ligands becomes operative, significantly strengthening J1 which attains the value of −0.97 meV in CrCl3, −1.21 meV in CrBr3 and −1.38 meV in CrI3. This increase in the magnitude of J1 quantifies the superexchange contribution to the bilinear exchange interaction, which is greater in CrI3 (0.78 meV) as compared to CrCl3 (0.33 meV) owing to the more extended p valence orbitals of the iodine atoms compared to the chlorine atoms. Hence, the sign of the bilinear exchange interaction can be qualitatively rationalized in terms of the rule devised by Goodenough57 and Kanamori58, which points to a ferromagnetic coupling when the Cr–X–Cr bond angle approaches 90o. The calculated values of the bilinear exchange interaction obtained at the MRCI level are in excellent agreement with certain recent experimental estimates, e.g., J1 = −0.92 meV for CrCl350 and −1.42 meV for CrI335, and their trend is consistent with the significantly lower critical temperature observed in the former magnet (~16 K50) than the latter (45 K8).

Importantly, we reveal a relatively sizable biquadratic exchange couplings J2, thus indicating that ferromagnetic two-electron hopping processes are active in chromium trihalides32,33,59. The strength of J2 appears to be weakly dependent on the nature of the halogen atom and on whether or not superexchange effects are described. This possibly suggests that, contrary to bilinear interactions, multispin interactions occur via the direct exchange between the Cr3+ ions. Both the isotropic bilinear and biquadratic exchange coupling largely exceed the anisotropic exchange interactions. Among the anisotropic exchange couplings , only the Kitaev interaction in CrI3 is non-vanishing (−0.05 meV), with all the off-diagonal terms being negligible. Irrespective of the nature of the halogen ligands, however, our results indicate a very small Kitaev-to-Heisenberg ratio, lending support to earlier findings on CrI330,45,60, and casting doubts on others29,61.

In particular, we find that the magnitudes of isotropic Heisenberg and Kitaev terms agree well with the couplings reported in ref. 62. At the same time, our results indicate a weaker quadratic exchange in all three chromium halides. A dominant isotropic and a weak anisotropic magnetic coupling is a common trend observed in various studies on 2D materials based on 3d transition metals62–64. In addition to the nearest-neighbor coupling, sizable second and third neighbor couplings have also been reported in chromium trihalides20,60. Also relevant are the interlayer exchange interactions in bulk halides, which are known to be ferromagnetic for CrI3 and CrBr3, but antiferromagnetic in the case of CrCl3. It has also been shown that the interlayer exchange is different for thin few layers as compared to bulk systems7,10,65. However, obtaining longer-range couplings from quantum chemistry calculations is not feasible at the moment due to very rapid growth of the computational cost with the cluster size.

Discussion

In conclusion, by using multiconfigurational and multireference wavefunctions, we have achieved a description of reference accuracy for the electronic excitations and the magnetic Hamiltonian parameters in chromium trihalides, as demonstrated by the excellent agreement with a variety of spectroscopy experiments. Our work serves as a reference for future computational studies of CrX3 and establishes many-body wavefunction-based calculations on embedded clusters as an effective approach to elucidating the nature of electronic and spin interactions in two-dimensional semiconducting magnets. Our calculations show that the magnetization direction which is determined by the interplay of out-of-plane magnetocrystalline anisotropy and magnetic dipole–dipole interaction favoring in-plane magnetization is clearly out-of-plane for CrI3 and in-plane for CrCl3 whereas for CrBr3 these two contributions almost exactly compensate one another, with a small out-of-plane resulting anisotropy. Note however that since out-of-plane direction in CrCl3 is provided by long-range dipole–dipole interactions Mermin–Wagner–Hohenberg theorem is not applicable in this case and one case expect true long-range order at low temperatures51,54.

Methods

We perform many-body wavefunction calculations on electrostatically embedded finite-size models constructed from the experimental bulk crystal structures of CrX3 (X = Cl, Br, I) materials23,66,67. As shown in Fig. 1a, the crystal structure of CrX3 magnets consists of layers in which Cr atoms form a honeycomb network and are sixfold coordinated by halogen atoms. The finite-size models adopted in our calculations comprise a central unit hosting either one (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. 1a) or two (Fig. 1c) octahedra treated with multireference or multiconfigurational wavefunctions, surrounded by the nearest-neighbor octahedra. These latter octahedra account for the charge distribution in the vicinity of the central unit and are treated at the Hartree–Fock level. The crystalline environment is restored by embedding each model in an array of point charges fitted to recreate the long-range Madelung electrostatic potential68. Electron correlation effects in the central units are described at the complete-active-space self-consistent-field (CASSCF) and multireference configuration interaction (MRCI) levels of theory69, including spin–orbit interactions. Technical details of our ab initio calculations are discussed at length in Supplementary Notes 1–3. CASSCF approach is well suited to study systems involving degenerate or nearly degenerate configurations, where static correlation is important. In addition to static correlation, MRCI calculations also take into account dynamic correlation by considering single and double excitations from the 3d (t2g) valence shells of Cr3+ ions and the p valence shells of the bridging halogen ligands. Therefore, the MRCI level of theory is more accurate and should be used when comparing with the experimental results. We present both CASSCF and MRCI results only to assess the relative importance of the two types of correlation effects. We remark that embedded finite-size model approaches have proven effective to describe electronic excitations and magnetic interactions in a rich variety of strongly correlated insulators70,71, including d-electron lattices56,72–74, owing to their localized nature.

Supplementary information

Supplemental Material for the manuscript

Acknowledgements

R.Y. is supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation—Sinergia Network NanoSkyrmionics (Grant No. CRSII5-171003) and NCCR MARVEL. M.P. is supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF) through the Early Postdoc. Mobility program (Grant No. P2ELP2-191706). The work of M.I.K. was supported by the ERC Synergy Grant, Project No. 854843 FASTCORR. L.X. thanks U. Nitzsche for technical assistance. Calculations were performed at the facilities of the Scientific IT and Application Support Center of EPFL and the Swiss National Supercomputing Centre (CSCS) under project s1146.

Author contributions

R.Y., L.X., and M.P. performed the calculations and analyzed the data. J.v.d.B. and M.I.K. contributed in the form of discussions. O.V.Y. directed the project. All authors contributed to the manuscript writing.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study can be obtained from authors (R.Y. and O.V.Y.) upon reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41699-024-00494-5.

References

- 1.Burch, K. S., Mandrus, D. & Park, J.-G. Magnetism in two-dimensional van der Waals materials. Nature563, 47–52 (2018). 10.1038/s41586-018-0631-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gibertini, M., Koperski, M., Morpurgo, A. F. & Novoselov, K. S. Magnetic 2D materials and heterostructures. Nat. Nanotechnol.14, 408–419 (2019). 10.1038/s41565-019-0438-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gong, C. & Zhang, X. Two-dimensional magnetic crystals and emergent heterostructure devices. Science363, eaav4450 (2019). 10.1126/science.aav4450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mak, K. F., Shan, J. & Ralph, D. C. Probing and controlling magnetic states in 2D layered magnetic materials. Nat. Rev. Phys.1, 646–661 (2019). 10.1038/s42254-019-0110-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mermin, N. D. & Wagner, H. Absence of ferromag-netism or antiferromagnetism in one- or two-dimensional isotropic Heisenberg models. Phys. Rev. Lett.17, 1133 (1966). 10.1103/PhysRevLett.17.1133 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hohenberg, P.C. Existence of long-range order in one and two dimensions. Phys. Rev.158, 383 (1967). 10.1103/PhysRev.158.383 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Soriano, D., Katsnelson, M. I. & Fernandez-Rossier, J. Magnetic two-dimensional chromium trihalides: a theoretical perspective. Nano Lett.20, 6225–6234 (2020). 10.1021/acs.nanolett.0c02381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang, B. et al. Layer-dependent ferromagnetism in a van der Waals crystal down to the monolayer limit. Nature546, 270–273 (2017). 10.1038/nature22391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sivadas, N., Okamoto, S., Xu, X., Fennie, C. J. & Xiao, D. Stacking-dependent magnetism in bilayer CrI3. Nano Lett.18, 7658–7664 (2018). 10.1021/acs.nanolett.8b03321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Song, T. et al. Switching 2D magnetic states via pressure tuning of layer stacking. Nat. Mater.18, 1298–1302 (2019). 10.1038/s41563-019-0505-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang, B. et al. Electrical control of 2D magnetism in bilayer CrI3. Nat. Nanotechnol.13, 544–548 (2018). 10.1038/s41565-018-0121-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jiang, S., Li, L., Wang, Z., Mak, K. F. & Shan, J. Controlling magnetism in 2D CrI33 by electrostatic doping. Nat. Nanotechnol.13, 549–553 (2018). 10.1038/s41565-018-0135-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tingxin, L. et al. Pressure-controlled inter-layer magnetism in atomically thin CrI3. Nat. Mater.18, 1303–1308 (2019). 10.1038/s41563-019-0506-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pizzochero, M. & Yazyev, O. V. Inducing magnetic phase transitions in monolayer CrI3 via lattice deformations. J. Phys. Chem. C124, 7585–7590 (2020). 10.1021/acs.jpcc.0c01873 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Webster, L. & Yan, J.-A. Strain-tunable magnetic anisotropy in monolayer CrCl3, CrBr3, and CrI3. Phys. Rev. B98, 144411 (2018). 10.1103/PhysRevB.98.144411 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang, R., Su, Y., Yang, G., Zhang, J. & Zhang, S. Bipolar doping by intrinsic defects and magnetic phase instability in monolayer CrI3. Chem. Mater.32, 1545–1552 (2020). 10.1021/acs.chemmater.9b04645 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pizzochero, M. Atomic-scale defects in the two-dimensional ferromagnet CrI3 from first principles. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys.53, 244003 (2020). 10.1088/1361-6463/ab7ca3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Singamaneni, S. R. et al. Light induced electron spin resonance properties of van der Waals CrX3 (X = Cl, I) crystals. Appl. Phys. Lett.117, 082406 (2020). 10.1063/5.0010888 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jang, S. W., Jeong, M. Y., Yoon, H., Ryee, S.-h. & Han, M. J. Microscopic understanding of magnetic interactions in bilayer CrI3. Phys. Rev. Mater.3, 031001 (2019). 10.1103/PhysRevMaterials.3.031001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Besbes, O., Nikolaev, S., Meskini, N. & Solovyev, I. Microscopic origin of ferromagnetism in the trihalides CrCl3 and CrI3. Phys. Rev. B99, 104432 (2019). 10.1103/PhysRevB.99.104432 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Soriano, D., Rudenko, A. N., Katsnelson, M. I. & Rosner, M. Environmental screening and ligand-field effects to magnetism in CrI3 monolayer. NPJ Comput. Mater.7, 162 (2021). 10.1038/s41524-021-00631-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang, D. & Sanyal, B. Systematic study of monolayer to trilayer CrI3: stacking sequence dependence of electronic structure and magnetism. J. Phys. Chem. C125, 18467–18473 (2021). 10.1021/acs.jpcc.1c04311 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McGuire, M. A. et al. Sales, magnetic behavior and spin-lattice coupling in cleavable van der Waals layered CrCl3 crystals. Phys. Rev. Mater.1, 014001 (2017). 10.1103/PhysRevMaterials.1.014001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Irkhin, V. Y., Katanin, A. A. & Katsnelson, M. I. Self-consistent spin-wave theory of layered Heisenberg magnets. Phys. Rev. B60, 1082–1099 (1999). 10.1103/PhysRevB.60.1082 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen, L. et al. Topological spin excitations in honeycomb ferromagnet CrI3. Phys. Rev. X8, 041028 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dzyaloshinsky, I. A thermodynamic theory of weak ferromagnetism of antiferromagnetics. J. Phys. Chem. Solids4, 241–255 (1958). 10.1016/0022-3697(58)90076-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moriya, T. Anisotropic superexchange interaction and weak ferromagnetism. Phys. Rev.120, 91 (1960). 10.1103/PhysRev.120.91 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang, H., Liang, J. & Cui, Q. First-principles calculations for Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction. Nat. Rev. Phys.5, 43–61 (2023). 10.1038/s42254-022-00529-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee, I. et al. Fundamental spin interactions underlying the magnetic anisotropy in the Kitaev ferromagnet CrI3. Phys. Rev. Lett.124, 017201 (2020). 10.1103/PhysRevLett.124.017201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kvashnin, Y. O., Bergman, A., Lichtenstein, A. I. & Katsnelson, M. I. Relativistic exchange interactions in CrX3 (X = Cl, Br, I) monolayers. Phys. Rev. B102, 115162 (2020). 10.1103/PhysRevB.102.115162 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ke, L. & Katsnelson, M. I. Electron correlation effects on exchange interactions and spin excitations in 2D van der Waals materials. NPJ Comput. Mater.7, 4 (2021). 10.1038/s41524-020-00469-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kartsev, A., Augustin, M., Evans, R. F. L., Novoselov, K. S. & Santos, E. J. G. Biquadratic exchange interactions in two-dimensional magnets. NPJ Comput. Mater.6, 150 (2020). 10.1038/s41524-020-00416-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wahab, D. A. et al. Quantum rescaling, domain metastability, and hybrid domain-walls in 2D CrI3 magnets. Adv. Mater.33, 2004138 (2021). 10.1002/adma.202004138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shao, Y. C. et al. Spectroscopic determination of key energy scales for the base Hamiltonian of chromium trihalides. J. Phys. Chem. Lett.12, 724–731 (2021). 10.1021/acs.jpclett.0c03476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cenker, J. et al. Direct observation of two-dimensional magnons in atomically thin CrI3. Nat. Phys.17, 20–25 (2021). 10.1038/s41567-020-0999-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pizzochero, M., Yadav, R. & Yazyev, O. V. Magnetic exchange interactions in monolayer CrI3 from many-body wavefunction calculations. 2D Mater.7, 035005 (2020). 10.1088/2053-1583/ab7cab [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Menichetti, G., Calandra, M. & Polini, M. Electronic structure and magnetic properties of few-layer CrGe2Te6: the key role of nonlocal electron-electron interaction effects. 2D Mater.6, 045042 (2019). 10.1088/2053-1583/ab2f06 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bogdanov, N. A. et al. Orbital breathing effects in the computation of X-ray d-ion spectra in solids by ab initio wave-function-based methods. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter29, 035502 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li, J. et al. Unraveling the orbital physics in a canonical orbital system KCuF3. Phys. Rev. Lett.126, 106401 (2021). 10.1103/PhysRevLett.126.106401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fabbris, G. et al. Doping dependence of collective spin and orbital excitations in the Spin-1 quantum antiferromagnet La2-xSrxNiO4 observed by X rays. Phys. Rev. Lett.118, 156402 (2017). 10.1103/PhysRevLett.118.156402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van der Laan, G. & Kirkman, I. The 2p absorption spectra of 3d transition metal compounds in tetrahedral and octahedral symmetry. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter4, 4189 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yadav, R. et al. Strong effect of hydrogen order on magnetic Kitaev interactions in H3LiIr2O6. Phys. Rev. Lett.121, 197203 (2018). 10.1103/PhysRevLett.121.197203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yadav, R. et al. Kitaev exchange and field-induced quantum spin-liquid states in honeycomb a-RuCl3. Sci. Rep.6, 37925 (2016). 10.1038/srep37925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maurice, R. et al. Universal theoretical approach to extract anisotropic spin Hamiltonians. J. Chem. Theory Comput.5, 2977–2984 (2009). 10.1021/ct900326e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lado, J. L. & Fernandez-Rossier, J. On the origin of magnetic anisotropy in two dimensional CrI3. 2D Mater.4, 035002 (2017). 10.1088/2053-1583/aa75ed [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Akhiezer, A. I., Bar'yakhtar, V. G. & Peletminskii, S. V. Spin Waves (North-Holland, Amsterdam, 1968).

- 47.Aharoni, A. Introduction to the Theory of Ferromagnetism (Clarendon Press, 2000).

- 48.Kim, T. Y. & Park, C.-H. Magnetic anisotropy and magnetic ordering of transition-metal phosphorus trisulfides. Nano Lett.21, 10114–10121 (2021). 10.1021/acs.nanolett.1c03992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cai, X. et al. Atomically thin CrCl3: an in-plane layered antiferromagnetic insulator. Nano Lett.19, 3993–3998 (2019). 10.1021/acs.nanolett.9b01317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kim, H. H. et al. Evolution of interlayer and intralayer magnetism in three atomically thin chromium trihalides. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA116, 11131–11136 (2019). 10.1073/pnas.1902100116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Maleev, S. V. Dipole forces in two-dimensional and layered ferromagnets. Sov. Phys. JETP43, 1240–1246 (1976). [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kleinert, H. Gauge Fields in Condensed Matter, Vol. 1. Superlow and Vortex Lines (World Scientific, Singapore, 1989).

- 53.Irkhin, V. Y. & Katanin, A. A. Kosterlitz-Thouless and magnetic transition temperatures in layered magnets with a weak easy-plane anisotropy. Phys. Rev. B60, 2990–2993 (1999). 10.1103/PhysRevB.60.2990 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Grechnev, A., Irkhin, V. Y., Katsnelson, M. I. & Eriksson, O. Thermodynamics of a two-dimensional Heisenberg ferromagnet with dipolar interaction. Phys. Rev. B71, 024427 (2005). 10.1103/PhysRevB.71.024427 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bolvin, H. An alternative approach to the g-matrix: theory and applications. Chem. Phys. Chem.7, 1575–1589 (2006). 10.1002/cphc.200600051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bogdanov, N. A., Maurice, R., Rousochatzakis, I., van den Brink, J. & Hozoi, L. Magnetic state of pyrochlore Cd2Os7O7 emerging from strong competition of ligand distortions and longer-range crystalline anisotropy. Phys. Rev. Lett.110, 127206 (2013). 10.1103/PhysRevLett.110.127206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Goodenough, J. B. An interpretation of the magnetic properties of the perovskite-type mixed crystals Lai_xSrxCoO3_λ. J. Phys. Chem. Solids6, 287–297 (1958). 10.1016/0022-3697(58)90107-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kanamori, J. Superexchange interaction and symmetry properties of electron orbitals. J. Phys. Chem. Solids10, 87–98 (1959). 10.1016/0022-3697(59)90061-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ni, J. Y. et al. Giant biquadratic exchange in 2d magnets and its role in stabilizing ferromagnetism of NiCl2 monolayers. Phys. Rev. Lett.127, 247204 (2021). 10.1103/PhysRevLett.127.247204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Torelli, D. & Olsen, T. Calculating critical temperatures for ferromagnetic order in two-dimensional materials. 2D Mater.6, 015028 (2018). 10.1088/2053-1583/aaf06d [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Xu, C., Feng, J., Xiang, Hongjun. & Bellaiche, Laurent. Interplay between Kitaev interaction and single ion anisotropy in ferromagnetic CrI3 and CrGeTe3 monolayers. NPJ Comput. Mater.4, 57 (2018). 10.1038/s41524-018-0115-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lu, X., Fei, R., Zhu, Linghan. & Yang, L. Meron-like topological spin defects in monolayer CrCl3. Nat. Commun.11, 4724 (2020). 10.1038/s41467-020-18573-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cui, Q. et al. Ferroelec-trically controlled topological magnetic phase in a Janus-magnet-based multiferroic heterostructure. Phys. Rev. Res.3, 043011 (2021). 10.1103/PhysRevResearch.3.043011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Liang, J. et al. Very large Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction in two-dimensional Janus manganese dichalcogenides and its application to realize skyrmion states. Phys. Rev. B101, 184401 (2020). 10.1103/PhysRevB.101.184401 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Serri, M. et al. Enhancement of the magnetic coupling in exfoliated CrCl3 crystals observed by low-temperature magnetic force microscopy and x-ray magnetic circular dichroism. Adv. Mater.32, 2000566 (2020). 10.1002/adma.202000566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Klinkova, L. A. & Bochkareva, V. A. Properties of bladed CrBr3 crystals. Inorg. Mater.16, 1207–1208 (1980). [Google Scholar]

- 67.McGuire, M. A., Dixit, H., Cooper, V. R. & Sales, B. C. Coupling of crystal structure and magnetism in the layered, ferromagnetic insulator CrI3. Chem. Mater.27, 612–620 (2015). 10.1021/cm504242t [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Klintenberg, M., Derenzo, S. E. & Weber, MJ. Accurate crystal fields for embedded cluster calculations. Computer Phys. Commun.131, 120–128 (2000). 10.1016/S0010-4655(00)00071-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Helgaker, T., Jorgensen, P. & Olsen, J. Molecular Electronic-Structure Theory (Wiley, 2000).

- 70.Iberio de Moreira, P. R. & Illas, F. A unified view of the theoretical description of magnetic coupling in molecular chemistry and solid state physics. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys.8, 1645–1659 (2006). 10.1039/b515732c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Malrieu, J. P., Caballol, R., Calzado, C. J., de Graaf, C. & Guihaery, N. Magnetic interactions in molecules and highly correlated materials: physical content, analytical derivation, and rigorous extraction of magnetic hamiltonians. Chem. Rev.114, 429–492 (2014). 10.1021/cr300500z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bogdanov, N. A., van den Brink, J. & Hozoi, L. Ab initio computation of d-d excitation energies in low-dimensional Ti and V oxychlorides. Phys. Rev. B84, 235146 (2011). 10.1103/PhysRevB.84.235146 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Katukuri, V. M., Stoll, H., van den Brink, J. & Hozoi, L. Ab initio determination of excitation energies and magnetic couplings in correlated quasi-two-dimensional iridates. Phys. Rev. B85, 220402 (2012). 10.1103/PhysRevB.85.220402 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.de P. R. Moreira, I. et al. Local character of magnetic coupling in ionic solids. Phys. Rev. B59, R6593 (1999). 10.1103/PhysRevB.59.R6593 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Material for the manuscript

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study can be obtained from authors (R.Y. and O.V.Y.) upon reasonable request.