Abstract

Objective:

To evaluate the association between urinary benzophenone-3 concentrations and measures of ovarian reserve (OR) among women in the Environment and Reproductive Health (EARTH) Study seeking fertility treatment at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts.

Design:

Prospective cohort study.

Methods:

Women from the EARTH cohort contributed spot urine samples before assessment of OR outcomes. Antral follicle count (AFC) and day-3 follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) levels were evaluated as part of standard infertility workups during unstimulated menstrual cycles. Quasi-Poisson and linear regression models were used to evaluate the association of specific gravity (SG)-adjusted urinary benzophenone-3 concentrations with AFC and FSH, respectively, with adjustment for age and physical activity. In secondary analyses, models were stratified by age. Sensitivity analyses assessed for confounding by season by restricting to women with exposure and outcome measured in the same season and stratifying by summer vs. non-summer months and for confounding by sunscreen use by restricting to women who filled out product questionnaires and adjusting for and stratifying by average sunscreen use score.

Results:

The study included 142 women (mean age ± SD, 36.1 ± 4.6; range, 22–45 years) enrolled between 2009 and 2017 with both urinary benzophenone-3 and AFC and 57 women with benzophenone-3 and FSH measurements. Most women were white (78%) and highly educated (49% with a graduate degree). Women contributed a mean of 2.7 urine samples (range, 1–10) with 37% contributing 2 or more samples. Benzophenone-3 was detected in 98% of samples. Geometric mean (GM) SG-corrected urinary benzophenone-3 concentration was 85.9 μg/L (geometric standard deviation 6.2). There were no associations of benzophenone-3 with AFC and day-3 FSH in the full cohort. In stratified models, a 1-unit increase in log GM benzophenone-3 was associated with AFC 0.91 (95% CI, 0.86, 0.97) times lower among women ≤35 years old and was associated with FSH 0.73 (95% CI, 0.12, 1.34) IU/L higher among women >35 years old. Effect estimates from models stratified by season and sunscreen use were null.

Conclusion:

In main models, urinary benzophenone-3 was not associated with OR. However, younger may be vulnerable to potential effects of benzophenone-3 on AFC. Further research is warranted.

Keywords: UV filters, benzophenone-3, ovarian reserve, infertility

Introduction

Endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs) have the potential to mimic endogenous hormones and impact hormone signaling, with downstream effects on reproductive health endpoints that rely on tightly regulated hormonal feedback loops. Ovarian function, critical for fertility, is sensitive to disruption of hormone signaling, steroidogenesis, follicular development, and metabolism (1–3). Ovarian reserve (OR) is a measurement of viable oocytes remaining in a female’s ovaries and is determined during folliculogenesis in utero, and by the rate at which oocytes are lost over a female’s reproductive lifespan (4). The gradual process of follicular atresia, reducing OR, may be modified by environmental factors inducing endocrine disrupting effects throughout reproductive years (3). Birth rates across the world have declined over the last several decades and while various factors play a role, exposure to environmental chemicals may contribute to the trend (5). The effect of modifiable exposures, such as EDCs, on OR is especially relevant for females struggling with infertility.

Chemical ultraviolet (UV) filters are used for sun protection in sunscreens and to prevent photodegradation in a variety of cosmetic and plastic products (6). Benzophenone derivatives are among the most toxic UV filters because of the presence of aromatic ketones and reactive oxygen species photodegradation products, which can affect endocrine, reproductive, and developmental systems (7, 8). One of the most widely used UV filters in cosmetics is benzophenone-3 (9, 10). Benzophenone-3 reaches peak plasma concentrations five hours after dermal exposure and is excreted in urine with an estimated terminal half-life of three days (11). Due to its prevalence in commonly used consumer products not marketed as sunscreens, benzophenone-3 is frequently detected even in populations with low sun exposure (12, 13). Studies on benzophenones and infertility-related outcomes are limited. In a mixtures analysis of EDCs and reproductive hormone levels in premenopausal women, the UV factor was associated with a decrease in estradiol, follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), and luteinizing hormone (14). Although studies have evaluated the effects of UV filters on sperm and male factor infertility (13, 15–17), few have studied endpoints related to female infertility. However, in vitro and in vivo experimental studies have linked benzophenone-3 to estrogenic and antiandrogenic activity as well as interference with the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis (9, 18, 19). Benzophenone-3 may act through alteration of receptor-binding activity of hormones and through increasing oxidative stress to disrupt ovarian function and follicle growth and accelerate the rate of oocyte loss (1, 10, 20). Furthermore, exposure to other phenolic chemicals with similar endocrine disrupting effects such as bisphenol A, triclosan, and parabens is associated with decreased OR in populations of women undergoing infertility treatments (21–24). Despite ubiquitous exposure, plausible mechanisms, and emerging concern about endocrine disrupting effects, benzophenone-3 has not been studied in relation to OR.

Clinical measures of OR provide an indication of potential fertility and have been validated against histological measurements of primordial follicle number (25). Antral follicle count (AFC) is a measure of follicles that have reached the tertiary stage of folliculogenesis and are visible on transvaginal ultrasound. Another common measure is FSH, a hormone that stimulates the growth of follicles (containing a developing egg) and is measured in relation to estradiol on day 3 of an unstimulated menstrual cycle. Here we aim to evaluate the association between urinary benzophenone-3 concentrations and OR in women in the Environment and Reproductive Health (EARTH) study cohort undergoing treatment for infertility.

Methods

Study population

Women included in this analysis were enrolled in the EARTH study, a prospective cohort designed to evaluate the effects of environmental and dietary exposures on reproductive health. Eligible women were aged 18 to 45 and undergoing infertility treatments at the Massachusetts General Hospital Fertility Center between 2004 and 2017 (benzophenone-3 was only included in assays after 2009). Women with previous physician-diagnosed polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) or with two polycystic ovaries observed in ultrasounds were excluded from analyses due to high antral follicle counts and different underlying mechanisms between endocrine disruption and PCOS vs. diminished OR (26). The study was approved by the Human Subject Committees of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Massachusetts General Hospital, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Ovarian reserve measures

Couples struggling to conceive received standard infertility workups that included evaluation of female OR at baseline and every six months to one year during infertility treatment depending on participant age. Day-3 serum FSH was measured at baseline using an automated electrochemiluminescence immunoassay at the Massachusetts General Hospital Core Laboratory using the Elecsys FSH reagent kit and the Roche Elecsys 1010/2010 immunoassay analyzer (Roche diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, USA), as described previously (27). AFC was determined through transvaginal ultrasound by a fertility physician on day 3 of an unstimulated cycle. Final AFC measurement (defined chronologically) during study participation was used to maximize prospective exposure data.

Quantification of benzophenone-3 in urine

Participants provided spot urine samples upon study entry and at each treatment cycle at the fertility center. Urine samples were collected in sterile polypropylene specimen cups. Urine sample specific gravity (SG) was measured at room temperature using a handheld refractometer (National Instrument Company Inc, Baltimore, MD, USA) calibrated with deionized water prior to processing and freezing at −80°C. Samples were shipped overnight on dry ice to the CDC laboratory and stored at or below −40 °C until analysis. Urinary benzophenone-3 was quantified using online solid-phase extraction coupled with isotope dilution-high-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry as described previously (28, 29). Concentrations below the limit of detection (LOD) (0.4 μg/L) were assigned values of the LOD divided by the square root of two (30). Urinary concentrations were adjusted for SG to correct for urine dilution: C=M[(SGM–1)/SG-1], where C is the SG-adjusted benzophenone-3 concentration (μg/L), M is the measured benzophenone-3 concentration, and SGM is the median SG level in the study population (31). Average urinary benzophenone-3 concentration (μg/L) was calculated as the geometric mean (GM) of SG-adjusted benzophenone-3 concentration from all samples collected before and on the day of outcome assessment. Models for FSH included only one urinary measurement per participant due to limited prospective data.

Covariates

At study enrollment, participants self-reported covariate information including date of birth, race, smoking status, and physical activity (hours/week). Trained study staff measured weight and height; body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight in kilograms per height in meters squared.

Statistical analysis

Time trends were plotted for SG-adjusted log-concentration of benzophenone-3 over the study period. The distribution of benzophenone-3 was summarized using percentage of results below the LOD, GM, median, interquartile range (IQR), and maximum, for both crude and SG-adjusted concentrations. Intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) from generalized mixed models with random intercepts by participant were used to summarize consistency in benzophenone-3 concentration across multiple measurements. Demographic and baseline reproductive characteristics overall and by benzophenone-3 tertile are presented using mean (standard deviation (SD)) and median or counts (%).

Urinary benzophenone-3 was analyzed both as continuous and in tertiles, to assess for non-linearity, with the lowest tertile considered the reference group. Continuous benzophenone-3 was log-transformed to reduce skewness and lessen the influence of outliers. Multivariable generalized linear models with a Quasi-Poisson distribution and log link function were used to evaluate the association between urinary benzophenone-3 and AFC to account for overdispersion in calculation of standard errors. General linear models were used to evaluate the association between urinary benzophenone-3 and day-3 FSH. For models with categorical benzophenone-3, p-values for trend were calculated using the median of each urinary concentration tertile. In secondary analyses, we stratified models to assess for effect measure modification by age (>35 or ≤35 years), the strongest predictor of AFC, as the effect of endocrine disruption on OR may depend on rate of age-related decline in OR.

In sensitivity analyses, we restricted to participants who had a urine sample collected 60 days or fewer before the OR measurement to assess for confounding by season and outcome measurement. These analyses included a single urinary benzophenone-3 concentration for each participant. Season was assigned as summer or non-summer based on the average date of the urine and outcome measurement. In this sub-population we assessed for confounding by season by adding a season term to the model and restricting to only exposure-outcome pairs from non-summer months.

To address potential confounding by healthy behaviors associated with higher sunscreen use and slower ovarian aging, we conducted sensitivity analyses restricted to participants who filled out at least one product questionnaire at the time of urine sample collection. Sunscreen scores were calculated as the sum of self-reported use of face lotion with sunscreen (yes/no) and use of body lotion with sunscreen (yes/no) in the 24 hours prior to sample collection. We assessed for confounding by adding sunscreen scores as a covariate to AFC models and stratifying models by above vs. below median sunscreen score.

All analyses were adjusted for age due to known associations with fertility outcomes (32, 33). Models additionally included physical activity because of its known association with OR biomarkers and potential association with sunscreen use.

Results

A total of 160 women enrolled in the EARTH cohort between 2009 and 2017 and submitted at least one urine sample prior to AFC measurement. After excluding participants with PCOS (n=15), participants with missing date of outcome assessment (n=1) and participants with polycystic ovaries recorded in both ovaries at pelvic ultrasound (n=2), the final study population for AFC analysis was 142. Models for FSH included 57 participants who had prospective benzophenone-3 measurements and day-3 FSH. The median age of study participants was 37 years and median BMI was 23.2 kg/m2 (Table 1). Missing BMI (n=1) was set to the median value. Most women were white (78%) and never smokers (75%). Women in the cohort were highly educated (49% with a graduate degree) and physically active (median activity per week=5 hours). Women in the second and third tertile of urinary benzophenone-3 concentrations were more likely to have female factor infertility diagnoses, while those in the first tertile were more likely to have unexplained infertility. Women in the third tertile were more physically active than women with lower benzophenone-3 concentrations (Table 1). Median (IQR) AFC and day-3 FSH in the study population was 13(9) and 6.6(2.5) IU/L, respectively. Among participants with both measurements, the Spearman correlation coefficient between AFC and FSH was −0.31.

Table 1.

Descriptive characteristics for women in the Environment and Reproductive Health Study cohort from 2009 to 2017 by urinary benzophenone-3 concentration tertile (N=142).

| Benzophenone-3 Tertile 1 (N=47) | Benzophenone-3 Tertile 2 (N=47) | Benzophenone-3 Tertile 3(N=48) | Overall (N=142) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Age (years) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 35.9 (4.89) | 37.0 (4.30) | 35.3 (4.45) | 36.1 (4.57) |

| Median [Min, Max] | 36.1 [22.0, 43.7] | 37.9 [27.3, 45.4] | 35.6 [24.1, 42.3] | 36.5 [22.0, 45.4] |

| Race, n(%) | ||||

| White | 35 (74.5%) | 38 (80.9%) | 37 (77.1%) | 110 (77.5%) |

| Black | 3 (6.4%) | 1 (2.1%) | 1 (2.1%) | 5 (3.5%) |

| Asian | 6 (12.8%) | 4 (8.5%) | 5 (10.4%) | 15 (10.6%) |

| Other | 3 (6.4%) | 4 (8.5%) | 5 (10.4%) | 12 (8.5%) |

| BMI (kg/m^2) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 23.9 (3.47) | 25.1 (6.26) | 24.5 (5.36) | 24.5 (5.15) |

| Median [Min, Max] | 23.9 [16.9, 30.1] | 22.9 [16.1, 53.7] | 23.0 [18.8, 45.8] | 23.2 [16.1, 53.7] |

| Smoking Status, n(%) | ||||

| Never Smoker | 32 (68.1%) | 37 (78.7%) | 38 (79.2%) | 107 (75.4%) |

| Ever Smoker | 15 (31.9%) | 10 (21.3%) | 10 (20.8%) | 35 (24.6%) |

| Education, n(%) | ||||

| < College Graduate | 4 (8.5%) | 4 (8.5%) | 2 (4.2%) | 10 (7.0%) |

| College Graduate | 12 (25.5%) | 11 (23.4%) | 21 (43.8%) | 44 (31.0%) |

| Graduate Degree | 22 (46.8%) | 24 (51.1%) | 24 (50.0%) | 70 (49.3%) |

| Missing | 9 (19.1%) | 8 (17.0%) | 1 (2.1%) | 18 (12.7%) |

| Infertility Diagnosis, n(%) | ||||

| Unexplained/Other | 22 (46.8%) | 16 (34.0%) | 15 (31.3%) | 53 (37.3%) |

| Male Factor | 13 (27.7%) | 9 (19.1%) | 11 (22.9%) | 33 (23.2%) |

| Female Factor | 12 (25.5%) | 22 (46.8%) | 22 (45.8%) | 56 (39.4%) |

| Total Physical Activity (hrs/wk) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 7.02 (9.63) | 5.42 (5.90) | 11.6 (14.9) | 8.03 (11.1) |

| Median [Min, Max] | 3.69 [0, 44.5] | 3.50 [0, 27.0] | 8.49 [0, 96.5] | 5.00 [0, 96.5] |

| Number of Urine Samples | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 2.70 (2.80) | 2.72 (2.51) | 2.69 (2.73) | 2.70 (2.66) |

| Median [Min, Max] | 1.00 [1.00, 10.0] | 1.00 [1.00, 9.00] | 1.00 [1.00, 10.0] | 1.00 [1.00, 10.0] |

| Day 3 FSH Levels (IU/L) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 6.47 (2.41) | 8.35 (2.74) | 6.94 (3.23) | 7.28 (2.87) |

| Median [Min, Max] | 6.60 [2.20, 13.4] | 7.95 [4.90, 14.4] | 6.40 [3.70, 16.1] | 6.60 [2.20, 16.1] |

| Missing, n(%) | 28 (60%) | 27 (57%) | 30 (63%) | 85 (60%) |

| Antral Follicle Count | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 14.6 (8.36) | 12.3 (6.31) | 13.8 (6.79) | 13.6 (7.22) |

| Median [Min, Max] | 13.0 [2.00, 30.0] | 11.0 [3.00, 30.0] | 13.5 [4.00, 30.0] | 13.0 [2.00, 30.0] |

| Log SG-Adjusted GM Benzophenone-3 Concentrations (log μg/L) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 2.48 (0.933) | 4.45 (0.323) | 6.49 (1.09) | 4.49 (1.85) |

| Median [Min, Max] | 2.61 [0.106, 3.68] | 4.48 [3.77, 4.99] | 6.12 [5.00, 9.43] | 4.48 [0.106, 9.43] |

BMI = body mass index; FSH = follicle stimulating hormone; SG = specific gravity; GM = geometric mean

Across the study period 384 urine samples were collected and analyzed for benzophenone-3; 98% of samples had detectable concentrations. The GM (geometric SD) of SG-adjusted benzophenone-3 concentration was 85.9(6.2) μg/L (Table 2). Fig. S1 illustrates a non-significant downward trend in concentrations over the study period (p-value for linear trend=0.21). The median (IQR) time between collection of the first urine sample and antral follicle scan was 97(316) days and the median (IQR) time between collection of first urine sample and FSH measurement was 7(22) days. The mean number of urine samples contributed per participant was 2.7; 53 participants (37%) contributed more than one sample. For participants who collected two or more samples, the median (IQR) time between collection of the first and last sample was 243(281) days. The ICC for urinary benzophenone-3 concentrations among those with two or more urine samples was 0.56.

Table 2.

Urinary benzophenone-3 summary statistics (μg/L) before and after specific gravity-adjustment for 384 urinary samples collected from 2009 to 2017 in the EARTH Study cohort.

| N | N < LODa (%) | GM (GSD) | Minimum | Median (25th, 75th percentile) | Maximum | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urinary Benzophenone-3 | 384 | 6 (2%) | 72.27 (7.62) | 0.14 | 64.80 (18.12, 253.95) | 29,500 |

| Specific Gravity-Adjusted Urinary Benzophenone-3 | 384 | 6 (2%) | 85.90 (6.24) | 0.18 | 81.89 (27.40, 288.10) | 12,418 |

LOD = limit of detection

LOD for benzophenone-3 was 0.4 μg/L.

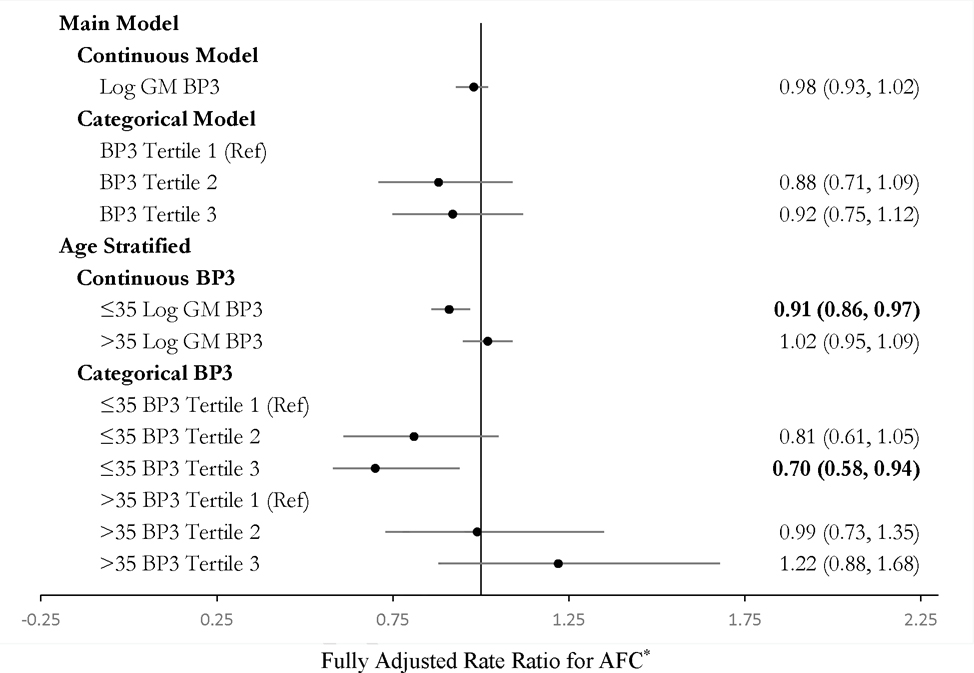

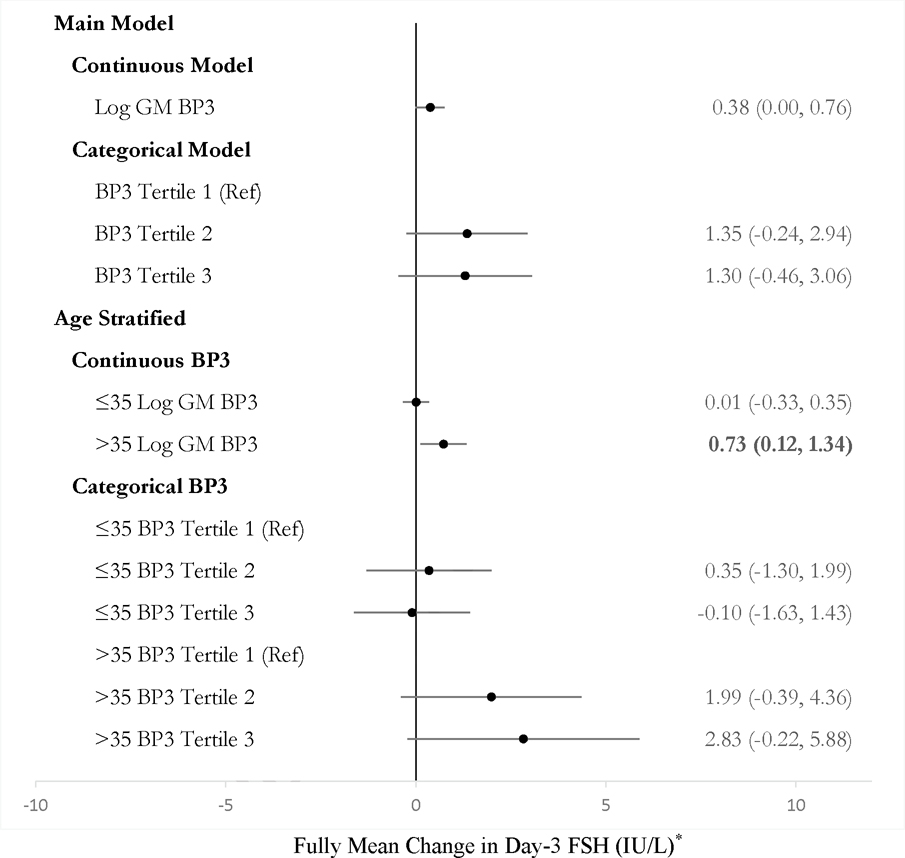

Urinary log GM benzophenone-3 was not associated with AFC in continuous or categorical models on the full study population (Figure 1). Adjustment for BMI did not change estimates. Stratified analyses suggested effect modification by age. Among women ≤35 years, being in the second and third tertile of benzophenone-3 concentrations was associated with a 19% decrease (95% CI, −39, +6%) and 30% decrease (95% CI, −46, −11%) in AFC as compared to being in the first tertile, respectively (Figure 1). Urinary benzophenone-3 was marginally associated with increased day-3 FSH among the 57 participants with FSH and prospective benzophenone-3 (Figure 2). In models restricted to age >35 years, a 1-unit increase in log GM benzophenone-3 concentrations was associated with FSH 0.73 (95% CI, 0.12, 1.34) IU/L higher.

Figure 1.

Effect estimates from Quasipoisson regression models for the association between specific gravity-adjusted urinary benzophenone-3 and antral follicle count (AFC) in women in the Environment and Reproductive Health (EARTH) study between 2009 and 2017 (N = 142).

*All estimates are adjusted for age and physical activity.

BP3 = Benzophenone-3

AFC = Antral follicle count

Effect estimates in bold for p < 0.05.

Unadjusted estimates and strata numbers are presented in Table S4.

Figure 2.

Estimated mean change in day-3 follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) (IU/L) by urinary benzophenone-3 concentration from linear regression models among women in the Environment and Reproductive Health (EARTH) study between 2009 and 2017 (N = 57).

*All estimates are adjusted for age and physical activity.

BP3 = Benzophenone-3

FSH = Follicle stimulating hormone

Effect estimates in bold for p < 0.05.

Unadjusted estimates and strata numbers are presented in Table S5.

The subset of participants with urinary benzophenone-3 measurements collected within 60 days preceding AFC measurement included 77 women. Of this subset, 64 women had benzophenone-3 and AFC measured in non-summer months. Effect estimates from analyses adjusted for season and excluding summer measurements were largely null and unstable (Table S2).

A total of 91 women filled out at least one product questionnaire on the day of urine sample collection. These women had slightly higher AFC and lower day-3 FSH than women without product questionnaires, however the distribution of benzophenone-3 concentrations and covariates was otherwise similar. Among this subset, after adjustment for age, physical activity, and sunscreen score, a 1-unit increase in log GM benzophenone-3 concentration was associated with a 6% decrease (95% CI, −11, −1%) in AFC (Table S3). Models stratified by median sunscreen score in this subset were null.

Discussion

In this study of women undergoing treatment for infertility, we found urinary benzophenone-3 was marginally associated with day-3 FSH, but not AFC, in overall models. The study population was predominately white and highly educated and included women with relatively high urinary benzophenone-3 concentrations. Stratified models suggested an inverse association between urinary benzophenone-3 and AFC among participants aged ≤35 years, and a positive association between urinary benzophenone-3 and FSH among participants >35 years. Generally, estimates for the association between benzophenone-3 and FSH were in the opposite direction of estimates from AFC analyses, as expected because lower AFC and higher day-3 FSH signal decreased OR.

Although our study is the first to examine the association between benzophenone-3 and AFC, two prior studies evaluated female benzophenone-3 exposure and fecundity. A study examining a variety of UV filters in couples trying to conceive reported that female exposure to benzophenone-3 was not associated with time to pregnancy (34). However, a cross-sectional study using National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data from 2013–2016 found higher benzophenone-3 concentrations among women with self-reported infertility compared to fertile women and found a significant association between a mixture of benzophenone-3, triclosan, and bisphenol A and self-reported infertility (35). Research on benzophenone-3 and FSH is also limited. A small study on 17 postmenopausal females found topical exposure to benzophenone-3 was not associated with FSH or luteinizing hormone (36). In a mixtures analysis on a population of premenopausal women, the UV factor, which included both benzophenone-3 and benzophenone-1, the primary metabolite of benzophenone-3 in humans, was associated with a decrease in estradiol, FSH, and luteinizing hormone (14). We found marginal associations between benzophenone-3 and increased day-3 FSH, particularly among older women. Our study contributes to limited and conflicting existing epidemiological literature that supports the need for further research to clarify the potential association between benzophenone-3 and fertility-related outcomes.

Endocrine disruption and accelerated aging are two potential mechanisms for our observed findings. Benzophenone-3 may act through alteration of availability of hormones or alteration of receptor-binding activity of hormones, which in turn affects ovarian function and follicle growth and development (1). Benzophenone-3 has demonstrated agonist effects on both α and β human estrogen receptors in yeast cells and rats (37, 38). Benzophenone-3 has also exhibited antagonistic effects in vitro at human androgen receptors (38, 39), and human progesterone receptors (38). In addition to endocrine disruption, benzophenone-3 may act by increasing oxidative stress, a key biological process in ovarian aging and mechanism behind premature ovarian aging (20, 40, 41). Urinary benzophenone-3 was associated with markers of oxidative stress in two different cohorts of pregnant women (42, 43, 10). Although developmental windows are critical times for disruption, environmental exposures throughout adult reproductive years may continue to affect follicle development, growth, and recruitment and may accelerate follicle atresia through endocrine disruption and oxidative stress.

Overall, urinary benzophenone-3 concentrations in the EARTH cohort are high compared to average concentrations in reproductive-aged women in the U.S. population between 2009 and 2016 (GM in NHANES=39.4 μg/L; SG-adjusted GM in current study=85.9 μg/L) (44). The difference may be partially attributed to the over representation in our study of non-Hispanic white women, who may use more sunscreen and have higher benzophenone-3 concentrations than women of other races/ethnicities (6, 35). Urinary benzophenone-3 concentrations for U.S. women in NHANES between 1999 and 2014 were 63% lower for non-Hispanic Blacks, 40% lower for Mexican Americans, and 21% lower for other Hispanics as compared to non-Hispanic Whites (45). The high urinary benzophenone-3 concentrations in our cohort are consistent with a previous study that found higher benzophenone-3 concentrations in women who were more affluent, older, and had lower BMI (46). Within person correlation in urinary benzophenone-3 concentrations for women who collected multiple samples (ICC=0.56) was slightly lower compared to ICCs for benzophenone-3 previously reported in literature (0.62–0.81) (47–49), but high compared to ICCs for other short half-life chemicals. One explanation for the lower consistency is the relatively long time between first and last sample collection in our study compared to previous cohorts (median=243 days).

In stratified analyses, benzophenone-3 was negatively associated with AFC among women aged ≤35 years and positively associated with FSH among women >35 years. Although it is possible this split is observed by chance due to small sample size, the observation for AFC is consistent with previous analyses in EARTH that reported stronger inverse relationships between other EDCs, including phthalates and triclosan, and AFC among younger women (23, 50). Because younger females have higher AFC, they may be more susceptible to potential detrimental effects of EDCs. Alternatively, because age is the strongest predictor of OR and females >35 years old experience rapid ovarian aging, effects of benzophenone-3 on decreased OR in older females may be masked by the strong effect of age. Another potential explanation is that our study had more power to observe associations with AFC in the younger group (larger variance in AFC) and with FSH in the older group (larger variance in FSH).

Season of benzophenone-3 measurement and sunscreen use may play important roles in interpretation of our results. A previous analysis in EARTH found that urinary benzophenone-3 was positively associated with ovarian responses to hormone stimulation, fertilization, implantation, clinical pregnancy, and live birth, among those who reported moderate/heavy work outdoors (51). A second EARTH study found higher benzophenone-3 concentrations were associated with a decrease in blood glucose levels during pregnancy, with the strongest associations during summer months (44). In both cases, authors suggested that observed associations could be confounded by vitamin D exposure or lifestyle factors associated with benzophenone-3 use. Benzophenone-3 concentrations in the EARTH cohort were associated with self-reported sunscreen use, and overall concentrations were higher in summer than winter (51). These results suggest that benzophenone-3 concentrations are most strongly correlated with sunscreen use in the summer or among people who spend significant time outdoors. Because of correlation between sunscreen use and healthy exposures associated with higher AFC (i.e., vitamin D, time outdoors, physical activity) (52), it may be difficult to observe harmful effects of benzophenone-3 even if a true association exists because confounding would bias effect estimates towards the null. We adjusted for weekly self-reported physical activity, although it was not independently associated with OR measures. Effect estimates in sensitivity analyses did not change significantly after adjustment for average sunscreen use, among women with available product use data. Power to examine confounding by season was limited by the number of participants with urinary benzophenone-3 and outcomes measured in the same season, and effect estimates after restricting to women with both exposure and outcome assessments in non-summer months were largely null and unstable.

Our study only assessed exposures during adult reproductive years. Because the process of oogenesis begins in utero, the adult reproductive-age exposure window may not be the most relevant for endocrine disruption. However, disruption in hormone production and function from environmental exposures throughout the life course may affect the rate of follicle atresia, and identifying modifiable exposures impacting OR during reproductive years is especially relevant for females attempting to conceive. Another limitation is that exposure measurement error may arise if a single spot urine sample does not accurately capture chronic exposure for chemicals with relatively short half-lives and for which exposures are episodic in nature. In our study, 37% of women had two or more samples and we took the average of multiple urinary benzophenone-3 concentrations thus reducing measurement error. Furthermore, our study and previous studies have found urinary benzophenone-3 concentrations to be relatively stable. Our study is subject to selection bias due to exclusion of participants without prospective urinary benzopheonen-3 measurements for FSH and AFC (Table S6 and S7), however we expect availability of prospective measurements to be primarily related to study scheduling and do not expect excluded participants to be systematically different than included participants. Finally, we were limited in available measures of OR. Day-3 FSH alone has a lower correlation with primordial OR than AFC (25) and is more informative when combined with day-3 estradiol measurements (53), which were not available in our study. However, our study included a robust sample of women with AFC, the most common measure for OR used in clinical and research settings.

Conclusions

Despite limitations, this is the first study to evaluate the associations of benzophenone-3 on OR. We found associations between increased urinary benzophenone-3 and lower AFC in younger women in the EARTH cohort. Although results from a cohort of women undergoing infertility treatments are not generalizable to all females, these women may be especially vulnerable to exposures related to diminishing OR. Benzophenone-3 remains a chemical of concern and future studies would benefit from examining effects on OR in larger populations, exploring exposure windows outside of adult reproductive years (i.e., prenatal, pubertal), and accounting for confounding effects by season and health-seeking behaviors.

Supplementary Material

Table S1. Effect estimates from Quasipoisson regression models for the association between specific gravity-adjusted urinary benzophenone-3 and antral follicle count (AFC) among women with exposure biomarker measurements within 2 months of outcome measurement (N = 77) additionally adjusted for season.†

Table S2. Effect estimates from Quasipoisson regression models for the association between specific gravity-adjusted urinary benzophenone-3 and antral follicle count (AFC) among women with exposure biomarker measurements within 2 months of outcome measurement and restricted to data collected in non-summer months (N = 64).†

Table S3. Effect estimates from Quasipoisson regression models for the association between specific gravity-adjusted urinary benzophenone-3 and antral follicle count (AFC) among women who filled out at least one product questionnaire on the day of urine sample collection (N = 91).

Table S4. Effect estimates from Quasipoisson regression models for the association between specific gravity-adjusted urinary benzophenone-3 and antral follicle count (AFC) in women in the Environment and Reproductive Health (EARTH) study between 2009 and 2017 (N = 142).

Table S5. Estimated mean change in day-3 follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) (IU/L) by urinary benzophenone-3 concentration from linear regression models among women in the Environment and Reproductive Health (EARTH) study between 2009 and 2017 (N = 57).

Table S6. Descriptive characteristics for all women in the Environment and Reproductive Health Study cohort from 2009 to 2017 stratified by inclusion criteria for benzophenone-3 and antral follicle count analysis

Table S7. Descriptive characteristics for women in the Environment and Reproductive Health Study cohort from 2009 to 2017 with urinary benzophenone-3 and antral follicle counts, stratified by inclusion in sub-cohort for FSH analysis (conditional on availability prospective urinary benzophenone-3 and day-3 follicle stimulating hormone measurements) (N=142).

Table S8. Descriptive characteristics for women in the Environment and Reproductive Health Study cohort from 2009 to 2017 by number of prospective urinary benzophenone-3 measurements (N=142).

Funding:

Supported by grants ES009718, ES022955, P30 ES000002 from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS).

Footnotes

Disclosure statement: The authors have no conflict of interests to disclose.

Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Use of trade name is for identification only and does not imply endorsement by the CDC, the Public Health Service, or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Craig ZR, Wang W, Flaws JA. Endocrine-disrupting chemicals in ovarian function: effects on steroidogenesis, metabolism and nuclear receptor signaling. Reproduction. 2011; 142:633–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prizant H, Gleicher N, Sen A. Androgen actions in the ovary: balance is key. Journal of Endocrinology. 2014; 222:R141–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Monteiro C de S, Xavier EB de S, Caetano JPJ, Marinho RM. A critical analysis of the impact of endocrine disruptors as a possible etiology of primary ovarian insufficiency. JBRA Assist Reprod. 2020; 24:324–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Richardson MC, Guo M, Fauser BCJM, Macklon NS. Environmental and developmental origins of ovarian reserve. Hum Reprod Update. 2014; 20:353–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Skakkebaek NE, Lindahl-Jacobsen R, Levine H, Andersson AM, Jorgensen N, Main KM, et al. Environmental factors in declining human fertility. Nature reviews Endocrinology. 2022; 18:139–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Calafat AM, Wong LY, Ye X, Reidy JA, Needham LL. Concentrations of the Sunscreen Agent Benzophenone-3 in Residents of the United States: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2003–2004. Environmental health perspectives. 2008; 116:893–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bonda CA, Lott D. Principles and Practice of Photoprotection [Internet]. [cited 2022]. Available from: https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-319-29382-0 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jesus A, Sousa E, Cruz MT, Cidade H, Lobo JMS, Almeida IF. UV Filters: Challenges and Prospects. Pharmaceuticals (Basel, Switzerland). 2022; 15:263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krause M, Klit A, Blomberg Jensen M, Søeborg T, Frederiksen H, Schlumpf M, et al. Sunscreens: are they beneficial for health? An overview of endocrine disrupting properties of UV-filters. International Journal of Andrology. 2012; 35:424–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mao JF, Li W, Ong CN, He Y, Jong MC, Gin KYH. Assessment of human exposure to benzophenone-type UV filters: A review. Environment International. 2022; 167:107405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matta MK, Florian J, Zusterzeel R, Pilli NR, Patel V, Volpe DA, et al. Effect of Sunscreen Application on Plasma Concentration of Sunscreen Active Ingredients: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2020; 323:256–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krause M, Andersson AM, Skakkebaek NE, Frederiksen H. Exposure to UV filters during summer and winter in Danish kindergarten children. Environ Int. 2017; 99:177–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frederiksen H, Krause M, Jorgensen N, Rehfeld A, Skakkebaek NE, Andersson AM. UV filters in matched seminal fluid-, urine-, and serum samples from young men. Journal of exposure science & environmental epidemiology. 2021; 31:345–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pollack AZ, Mumford SL, Krall JR, Carmichael AE, Sjaarda LA, Perkins NJ, et al. Exposure to bisphenol A, chlorophenols, benzophenones, and parabens in relation to reproductive hormones in healthy women: A chemical mixture approach. Environment International. 2018; 120:137–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen M, Tang R, Fu G, Xu B, Zhu P, Qiao S, et al. Association of exposure to phenols and idiopathic male infertility. J Hazard Mater. 2013; 250–251:115–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schiffer C, Müller A, Egeberg DL, Alvarez L, Brenker C, Rehfeld A, et al. Direct action of endocrine disrupting chemicals on human sperm. EMBO Rep. 2014; 15:758–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rehfeld A, Dissing S, Skakkebæk NE. Chemical UV Filters Mimic the Effect of Progesterone on Ca2+ Signaling in Human Sperm Cells. Endocrinology (Philadelphia). 2016; 157:4297–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang J, Pan L, Wu S, Lu L, Xu Y, Zhu Y, et al. Recent Advances on Endocrine Disrupting Effects of UV Filters. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016; 13:782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wnuk W, Michalska K, Krupa A, Pawlak K. Benzophenone-3, a chemical UV-filter in cosmetics: is it really safe for children and pregnant women? Advances in Dermatology and Allergology. 2022; 39:26–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li Q, Geng X, Zheng W, Tang J, Xu B, Shi Q. Current understanding of ovarian aging. Sci China Life Sci. 2012; 55:659–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith KW, Souter I, Dimitriadis I, Ehrlich S, Williams PL, Calafat AM, et al. Urinary Paraben Concentrations and Ovarian Aging among Women from a Fertility Center. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2013; 121:1299–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Souter I, Smith KW, Dimitriadis I, Ehrlich S, Williams PL, Calafat AM, et al. The association of bisphenol-A urinary concentrations with antral follicle counts and other measures of ovarian reserve in women undergoing infertility treatments. Reproductive Toxicology. 2013; 42:224–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mínguez-Alarcón L, Christou G, Messerlian C, Williams PL, Carignan CC, Souter I, et al. Urinary triclosan concentrations and diminished ovarian reserve among women undergoing treatment in a fertility clinic. Fertility and Sterility. 2017; 108:312–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Land KL, Miller FG, Fugate AC, Hannon PR. The effects of endocrine-disrupting chemicals on ovarian- and ovulation-related fertility outcomes. Molecular reproduction and development. 2022; 89:608–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hansen KR, Hodnett GM, Knowlton N, Craig LB. Correlation of ovarian reserve tests with histologically determined primordial follicle number. Fertility and Sterility. 2011; 95:170–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Crain DA, Janssen SJ, Edwards TM, Heindel J, Ho S mei, Hunt P, et al. Female reproductive disorders: the roles of endocrine-disrupting compounds and developmental timing. Fertility and Sterility. 2008; 90:911–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mok-Lin E, Ehrlich S, Williams PL, Petrozza J, Wright DL, Calafat AM, et al. Urinary bisphenol A concentrations and ovarian response among women undergoing IVF. Int J Androl. 2010; 33:385–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ye X, Kuklenyik Z, Needham LL, Calafat AM. Automated on-line column-switching HPLC-MS/MS method with peak focusing for the determination of nine environmental phenols in urine. Anal Chem. 2005; 77:5407–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Silva MJ, Jia T, Samandar E, Preau JL, Calafat AM. Environmental exposure to the plasticizer 1,2-cyclohexane dicarboxylic acid, diisononyl ester (DINCH) in U.S. adults (2000–2012). Environ Res. 2013; 126:159–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hornung RW, Reed LD. Estimation of Average Concentration in the Presence of Nondetectable Values. Applied Occupational and Environmental Hygiene. 1990; 5:46–51. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Duty SM, Ackerman RM, Calafat AM, Hauser R. Personal care product use predicts urinary concentrations of some phthalate monoesters. Environ Health Perspect. 2005; 113:1530–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sharma R, Biedenharn KR, Fedor JM, Agarwal A. Lifestyle factors and reproductive health: taking control of your fertility. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2013; 11:66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rooney KL, Domar AD. The impact of lifestyle behaviors on infertility treatment outcome. Current Opinion in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2014; 26:181–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Buck Louis GM, Kannan K, Sapra KJ, Maisog J, Sundaram R. Urinary Concentrations of Benzophenone-Type Ultraviolet Radiation Filters and Couples’ Fecundity. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2014; 180:1168–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arya S, Dwivedi AK, Alvarado L, Kupesic-Plavsic S. Exposure of U.S. population to endocrine disruptive chemicals (Parabens, Benzophenone-3, Bisphenol-A and Triclosan) and their associations with female infertility. Environmental pollution (1987). 2020; 265:114763–114763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Janjua NR, Mogensen B, Andersson AM, Petersen JH, Henriksen M, Skakkebæk NE, et al. Systemic Absorption of the Sunscreens Benzophenone-3, Octyl-Methoxycinnamate, and 3-(4-Methyl-Benzylidene) Camphor After Whole-Body Topical Application and Reproductive Hormone Levels in Humans. Journal of investigative dermatology. 2004; 123:57–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schreurs R, Lanser P, Seinen W, van der Burg B. Estrogenic activity of UV filters determined by an in vitro reporter gene assay and an in vivo transgenic zebrafish assay. Arch Toxicol. 2002; 76:257–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schreurs RHMM. Interaction of Polycyclic Musks and UV Filters with the Estrogen Receptor (ER), Androgen Receptor (AR), and Progesterone Receptor (PR) in Reporter Gene Bioassays. Toxicological Sciences. 2004; 83:264–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Molina-Molina JM, Escande A, Pillon A, Gomez E, Pakdel F, Cavaillès V, et al. Profiling of benzophenone derivatives using fish and human estrogen receptor-specific in vitro bioassays. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2008; 232:384–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Younis A, Clower C, Nelsen D, Butler W, Carvalho A, Hok E, et al. The relationship between pregnancy and oxidative stress markers on patients undergoing ovarian stimulations. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2012; 29:1083–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Woodard TL, Bolcun-Filas E. Prolonging Reproductive Life after Cancer: The Need for Fertoprotective Therapies. Trends Cancer. 2016; 2:222–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Watkins DJ, Ferguson KK, Anzalota Del Toro LV, Alshawabkeh AN, Cordero JF, Meeker JD. Associations between urinary phenol and paraben concentrations and markers of oxidative stress and inflammation among pregnant women in Puerto Rico. International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health. 2015; 218:212–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ferguson KK, Lan Z, Yu Y, Mukherjee B, McElrath TF, Meeker JD. Urinary concentrations of phenols in association with biomarkers of oxidative stress in pregnancy: Assessment of effects independent of phthalates. Environment International. 2019; 131:104903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang Z, Minguez-Alarcon L, Williams PL, Bellavia A, Ford JB, Keller M, et al. Perinatal urinary benzophenone-3 concentrations and glucose levels among women from a fertility clinic. Environmental health. 2020; 19:45–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nguyen VK, Kahana A, Heidt J, Polemi K, Kvasnicka J, Jolliet OJ, et al. A comprehensive analysis of racial disparities in chemical biomarker concentrations in United States women, 1999–2014. Environ Int. 2020; 137:105496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kunisue T, Chen Z, Buck Louis GM, Sundaram R, Hediger ML, Sun L, et al. Urinary Concentrations of Benzophenone-type UV Filters in US Women and Their Association with Endometriosis. Environ Sci Technol. 2012; 46:4624–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lassen TH, Frederiksen H, Jensen TK, Petersen JH, Main KM, Skakkebæk NE, et al. Temporal variability in urinary excretion of bisphenol A and seven other phenols in spot, morning, and 24-h urine samples. Environ Res. 2013; 126:164–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Meeker JD, Cantonwine DE, Rivera-González LO, Ferguson KK, Mukherjee B, Calafat AM, et al. Distribution, variability, and predictors of urinary concentrations of phenols and parabens among pregnant women in Puerto Rico. Environ Sci Technol. 2013; 47:3439–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Koch HM, Aylward LL, Hays SM, Smolders R, Moos RK, Cocker J, et al. Inter- and intra-individual variation in urinary biomarker concentrations over a 6-day sampling period. Part 2: Personal care product ingredients. Toxicology Letters. 2014; 231:261–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Messerlian C, Souter I, Gaskins AJ, Williams PL, Ford JB, Chiu YH, et al. Urinary phthalate metabolites and ovarian reserve among women seeking infertility care. Hum Reprod. 2016; 31:75–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mínguez-Alarcón L, Chiu YH, Nassan FL, Williams PL, Petrozza J, Ford JB, et al. Urinary concentrations of benzophenone-3 and reproductive outcomes among women undergoing infertility treatment with assisted reproductive technologies. Science of The Total Environment. 2019; 678:390–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bacanakgil BH, İlhan G, Ohanoğlu K. Effects of vitamin D supplementation on ovarian reserve markers in infertile women with diminished ovarian reserve. Medicine. 2022; 101:e28796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Smotrich DB, Widra EA, Gindoff PR, Levy MJ, Hall JL, Stillman RJ. Prognostic value of day 3 estradiol on in vitro fertilization outcome. Fertil Steril. 1995; 64:1136–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Effect estimates from Quasipoisson regression models for the association between specific gravity-adjusted urinary benzophenone-3 and antral follicle count (AFC) among women with exposure biomarker measurements within 2 months of outcome measurement (N = 77) additionally adjusted for season.†

Table S2. Effect estimates from Quasipoisson regression models for the association between specific gravity-adjusted urinary benzophenone-3 and antral follicle count (AFC) among women with exposure biomarker measurements within 2 months of outcome measurement and restricted to data collected in non-summer months (N = 64).†

Table S3. Effect estimates from Quasipoisson regression models for the association between specific gravity-adjusted urinary benzophenone-3 and antral follicle count (AFC) among women who filled out at least one product questionnaire on the day of urine sample collection (N = 91).

Table S4. Effect estimates from Quasipoisson regression models for the association between specific gravity-adjusted urinary benzophenone-3 and antral follicle count (AFC) in women in the Environment and Reproductive Health (EARTH) study between 2009 and 2017 (N = 142).

Table S5. Estimated mean change in day-3 follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) (IU/L) by urinary benzophenone-3 concentration from linear regression models among women in the Environment and Reproductive Health (EARTH) study between 2009 and 2017 (N = 57).

Table S6. Descriptive characteristics for all women in the Environment and Reproductive Health Study cohort from 2009 to 2017 stratified by inclusion criteria for benzophenone-3 and antral follicle count analysis

Table S7. Descriptive characteristics for women in the Environment and Reproductive Health Study cohort from 2009 to 2017 with urinary benzophenone-3 and antral follicle counts, stratified by inclusion in sub-cohort for FSH analysis (conditional on availability prospective urinary benzophenone-3 and day-3 follicle stimulating hormone measurements) (N=142).

Table S8. Descriptive characteristics for women in the Environment and Reproductive Health Study cohort from 2009 to 2017 by number of prospective urinary benzophenone-3 measurements (N=142).