Abstract

Macrophages are integral part of the body's defense against pathogens and serve as vital regulators of inflammation. Adaptor molecules, featuring diverse domains, intricately orchestrate the recruitment and transmission of inflammatory responses through signaling cascades. Key domains involved in macrophage polarization include Toll-like receptors (TLRs), Src Homology2 (SH2) and other small domains, alongside receptor tyrosine kinases, crucial for pathway activation. This review aims to elucidate the enigmatic role of macrophage adaptor molecules in modulating macrophage activation, emphasizing their diverse roles and potential therapeutic and investigative avenues for further exploration.

Keywords: : adaptor proteins, biomarkers, cell signaling, cytokine production, immunomodulation, inflammation, macrophage, pathogen recognition, therapeutic targets, TLR

Plain Language Summary

In our manuscript, we explore the vital role of adaptor proteins regarding ways, our immune cells, specifically macrophages, detect and respond to threats. These proteins act as crucial messengers, helping macrophages recognize harmful invaders and initiate the body's defense mechanisms. Understanding this process not only sheds light on how our immune system works but also holds promise for developing new therapies to combat infections and inflammatory diseases. Our findings offer insight into the intricate world of immune response, potentially paving the way for improved treatments for a range of health conditions.

Plain language summary

Article highlights.

Introduction to adaptor proteins & macrophage signaling

Overview of TLRs in macrophages and their role in chronic inflammatory responses.

Importance of adaptor proteins in mediating TLR signaling pathways.

Functional dynamics of different adaptor molecules

Detailed inference on adaptor protein interactions with key inflammatory signaling proteins during TLR activation.

Analysis of inflammatory signaling pathways triggered by adaptor protein interactions with binding partners and their impact on inflammatory conditions.

Summary & conclusion

Future perspective

To uncover new adaptor proteins and their key role in chronic inflammatory pathways.

To develop techniques for detecting adaptor protein interactions in chronic inflammatory conditions.

1. Introduction

Macrophages are indispensable cells that serve dual functions of maintaining tissue homeostasis and regulating inflammation, while also providing vital protection against pathogens [1]. The functional versatility and differentiation of macrophages are essential elements of their lineage diversification and adaptability [2]. With tissue-specific roles that are critical to overall tissue health, macrophages play an essential role in promoting the organism's well-being [1]. Macrophages possess a crucial attribute of plasticity, enabling them to transition from a quiescent M0 state into diverse activated states in response to dynamic environmental conditions [2]. According to the changes in the tissue environment, macrophages (activated) are polarized into two different subtypes: M1 macrophage and M2 macrophage [3]. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) can stimulate classical activation of macrophages, while IL-4 can lead to alternative activation [4]. The foremost and extensively studied subtype is the classically activated macrophages, which function as effector cells in Th1 cellular immune responses [5]. Both M1 and M2 macrophages play pivotal roles in orchestrating inflammatory responses, with M1 macrophages primarily governing the pro-inflammatory response and M2 macrophages predominantly regulating the anti-inflammatory response [6].

Analogous to the color allotment of a chameleon, macrophage plasticity makes it difficult to assign a specific biochemical marker to each population or activity state [7]. Furthermore, the increasing body of evidence indicates that macrophage diversity may orchestrate tissue development and function, controlling organ functionality during development, homeostasis and ageing [8]. However, macrophage heterogeneity holds enormous potential for understanding diseases and can be leveraged as biomarkers or surrogate markers of protection after drug treatment or vaccination [7]. Two different classes of macrophages are speculated to have a similar set of genes required for protein synthesis, phagocytic activities, gene regulations and for basic macrophage functioning [9]. Anti-inflammatory reprogramming probably acts as a precursor in M1 to M2 macrophage transitions. M2 macrophages, being less harmful to microbes and vulnerable post-mitotic host cells like neurons, are commonly associated with anti-inflammatory or reparative roles [9]. The process of macrophage polarization is precisely regulated by critical signaling events [10,11]. Macrophages undergo classical activation in response to an injury or infection, which occurs due to microbial products or pro-inflammatory cytokines, including bacterial LPS, interferon-γ (IFN-γ), or tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) [12]. Studies have shown the prominent involvement of transcription factor such as NF-κB that leads to the activation of various markers of inflammation [13]. Considering the markers for inflammatory diseases, receptors such as TLRs have been observed to be associated with various diseases and infectious conditions [14]. M1 macrophages, primarily involved in tissue injury and microbicidal activity are associated with markers namely CD86, CD40, MHCII [15]. On the other hand, M2 macrophages involved in anti-inflammatory, wound healing is recognized by the presence of CD163, CD36, CD206, CD209 and so on [15,16]. For their peculiar functions and plasticity, macrophages play both protective and pathogenic roles in a wide range of autoimmune, inflammatory as well as cancer diseases [17].

Adaptor proteins typically possess a modular architecture characterized by the inclusion of one or more dedicated domains, which facilitate their interaction with various other proteins [18,19]. These domains play a significant role in facilitating interactions with phosphorylated tyrosine residues found on the target proteins [18]. Adaptor molecules assume a pivotal role in diverse receptor-mediated signaling pathways, functioning as vital linkages that connect receptors with other molecules, thereby facilitating essential cellular communication [18]. Macrophages undergo classical activation upon encountering two essential signals; the initial signal involves the mandatory cytokine IFN-γ, which primes macrophages for activation, but by itself, does not trigger their activation [20]. The second signal encompasses either TNF or a stimulus that induces TNF production [21]. Although exogenous TNF can fulfill the role of the second signal, the biologically significant second signal predominantly arises from the ligation of Toll-like receptors (TLRs), leading to endogenous TNF production by the macrophage itself [21]. TLR2 and TLR4 are key players in recognizing specific molecular patterns from invading pathogens via PRRs and regulate the balance between Th1 and Th2 response, essential for host survival against major infectious diseases like tuberculosis, trypanosomiasis, malaria and filariasis [22,23]. So far, in the efforts to prevent and treat inflammatory diseases, diverse TLR antagonists/inhibitors have proven effective, progressing from preclinical testing to clinical trials [24]. Immunogenetic variability significantly influences a host's susceptibility or resistance to infectious diseases. Principal polymorphic sites within TLRs, predominantly single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), include l602S (TLR1), R677W (TLR2), P554S (TLR3), D399G (TLR4), F616L (TLR5), S249P (TLR6), Q11L (TLR7), M1V (TLR8), G1174A (TLR9) and G1021T (TLR10) [25].

Studies demonstrate the anti-inflammatory potential of 3a-u, a synthesized compound from aryl 7-chloroquinolinyl hydrazone derivatives act as TLR4 antagonists on macrophage membranes, modulating the TLR4-NFkB pathway [26]. Consequently, the development of classically activated macrophages is triggered by the presence of IFN-γ and exposure to a microorganism or microbial component, such as LPS [27,28]. In the murine system, the distinct characteristic of classically activated macrophages is their prominent generation of nitric oxide (NO), enabling facile recognition [27]. Adaptor proteins are essential immunological molecules that do not possess inherent enzymatic and transcriptional activity [29]. The including cytokines, hormones and growth factors, involves the coordinated actions of multiple molecular components [29]. Notably, the activation of receptor tyrosine kinases, which plays a central role in these pathways, is triggered by ligand-induced oligomerization and subsequent autophosphorylation [29]. This event initiates a downstream signaling cascade that involves various kinases, transcription factors and adaptor molecules, leading to the regulation of diverse cellular processes and functions [29]. These mechanisms are well-documented in the scientific literature and are critical for understanding the complex interplay between extracellular signals and intracellular responses in health and disease [29]. A diverse range of origins and functions characterize macrophages, an immune cell population with significant heterogeneity [8,30]. Categorizing macrophages based on their activation state can be effectively accomplished through the concept of macrophage polarization [31].

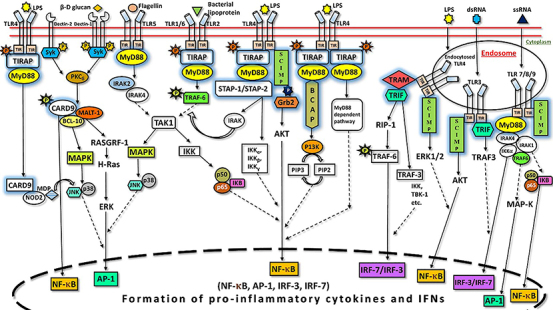

In this review, we have summarized the macrophage adaptor proteins which play an imperative role in orchestrating the immune response by activating the Toll-like receptors signaling pathway (Figure 1 & Table 1). The extensive list has been categorized into one major part which includes the adaptor molecules that facilitate the immune response along with the enigmatic role of some macrophage adaptors involved in both pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory roles in some cases, respectively. Adaptor proteins that act as facilitators mainly induce activation and stimulate the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines.

Figure 1.

Role of macrophage adaptor proteins in toll-like receptors signaling pathway.

Table 1.

Role of macrophage Adaptor proteins in Toll-Like Receptors signaling pathways.

| Name of the Adaptor Protein | Function | Domain | Signaling Pathways | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TIRAP | Acts as bridging protein to recruit MyD88 to TLR4/2 inflammatory signaling in MyD88 dependent pathway. | TIR | TLR1, TLR2, TLR4-9 | [31,32,34,35,38] |

| TRIF | Acts in a similar way to MyD88 in the MyD88 independent pathway. | TIR | TLR3-5, TLR7-9 | [36,40,43,44,50,51,172,180] |

| TRAM | Helps in the recruitment of TRIF to TLR4. | TIR | TLR4, TLR5, TLR7-9 | [36,40,44,51,58,172,180] |

| MyD88 | Acts as connecting proteins that receive signals from outside the cell to the proteins that relay signals inside the cell. | TIR | TLR1, TLR2, TLR4-9 | [29,32,77,78,84,86,173,181] |

| SCIMP | Promotes selective pro-inflammatory cytokine production by direct modulation of TLR4. | Non-TIR | TLR2-4, TLR9 | [95,100,101,103,108,109] |

| Grb2 | Plays a key role in MR-mediated signaling cascade in human macrophages. | SH2 + 2 SH3 | TLR4 | [107–109,115–117,174,182] |

| BCAP | Links TLR to P13K through the TIR domain. | TIR | TLR4 | [109,117,121,126,129,134] |

| STAP-1 | Binds to MyD88 and enhances the production of inflammatory cytokines. | SH2 + PH | TLR4 | [126,129,134,135,137,143] |

| STAP-2 | Binds to MyD88 and enhances the production of inflammatory cytokines. Also binds with TRAF1 and TRAF3 and upregulates the NF-KB signaling. | SH2 + PH | TLR4 | [143,151,175,183] |

| iba1 | It is a microglia/macrophage-specific calcium-binding protein. | – | – | [145,153] |

| CARD9 | Is in charge of mediating signals from PRRs to downstream transcription factor NF-κB. | CARD | TLR4, Dectin1, Dectin2 | [154,158,159,162,166,167] |

1.1. Toll-interleukin-1 receptor domain-containing adaptor protein

Toll-interleukin-1 receptor (TIR) domain-containing adaptor protein(TIRAP) has been found to function downstream of TLR4 signaling pathways [32,33]. TIRAP is a pivotal mediator of varied immune responses and functions as a key intracellular signaling molecule [34]. In relation to TLR-mediated innate immune signaling, TIRAP's function as an adaptor molecule has been extensively explored [35]. Since its discovery in 2001, early studies focused on TIRAP's role in coupling MyD88 with TLRs, which leads to the activation of MyD88-dependent TLR signaling [34,36]. Further studies revealed that TIRAP also transduces signaling events by interacting with non-TLR signaling mediators [34]. The broad range of intracellular signaling mediators with which TIRAP interacts underscores its central role in multiple immune responses [34,36]. Mice lacking TIRAP demonstrate normal responsiveness to TLR5, TLR7 and TLR9 ligands, as well as to IL-1 and IL-18 [37]. However, they exhibit deficiencies in cytokine production and activation of NF-κB and MAPKs in response to TLR4 ligand [37]. Additionally, these mice have impaired responses to ligands for TLR2, TLR1 and TLR6, suggesting that TIRAP plays a distinctive role in the signaling of various TLR members [37]. The specificity in downstream signaling pathways of individual TLRs is potentially due to the involvement of TIRAP [37].

Upon binding to their corresponding ligands (PAMP), TLRs prompt the recruitment of MyD88 to the intracellular domain of the receptor, apart from TLR2 and TLR4, for which MyD88 is indirectly recruited via TIRAP [38,39]. This recruitment process leads to the formation of a significant complex called the “myddosome” [26]. TIRAP is essential for recruiting MyD88 to TLR2 and TLR4 and is anchored to the membrane through a phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphoaphate-binding domain [40,41]. TIRAP's centralized role in profuse immunological responses can be elucidated by its interaction with numerous intracellular signaling mediators [34]. Several transcription factors such as NF-κB and AP-1 get activated as a result of downstream signaling events [38,42,43]. The pro-inflammatory cytokine production by immune cells and control of host cell survival mainly depends on TLR-mediated signaling pathway activation [34]. By undergoing this process, the cell is transformed into a state that aids in reducing the effects of infection [34]. While regulated activation of TLR is necessary for the host's defense mechanisms, excessive amplification of pro-inflammatory cytokines can have a harmful impact on the host's immune system [34,44].

Tyrosine phosphorylation of TIRAP in the TIR domain is pivotal for its activation [45,46]. In TLR 2/4 signaling, Y86, Y106 and Y159 and Y187 of TIRAP undergo phosphorylation by BTK and PKCδ, which are essential for activating downstream MAPKs [45]. The tyrosine phosphorylation at the Y86 site leads to conformational changes that draw TIRAP closer to the p38 MAPK kinase domain's active site and it also plays a vital role at the interface site [45,46]. The process gets reversed when the Y86 site is dephosphorylated [45]. The TIRAP intracellular signaling initiation is intricate and TIR domain is required for numerous protein-protein interactions [35]. Other interaction partners that have been reported for TIRAP include RAGE, PKCδ, CLIP170, Triad3A, SOCS1, c-JUN etc. [34,35]. The role of TIRAP of mediating inflammation has been reported in various studies. When Mal(-/-) mice (TIRAP KO) were infected with Bordetella pertussis, which causes infectious diseases of the respiratory system, exhibited higher bacterial load in the lungs and lower macrophage infiltration and survival. The pro-inflammatory cytokine production and bacterial killing ability of macrophages from Mal(-/-) mice was decreased [47]. Another study focusing on sepsis showed that blocking the interaction of TIRAP with PKCδ by dorzolamide in LPS-treated macrophages attenuates the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines, mediated via suppression of p38 MAPK activation [48]. Disruption of TIRAP interaction with c-Jun by gefitinib was proposed as a potential treatment of sepsis patients. TIRAP forms complexes with c-Jun upon macrophage treatment with LPS, leading to the activation of AP-1 and increased pro-inflammatory cytokines, an effect that was abolished by gefitinib [49].

1.2. Toll-interleukin-1-receptor-domain-containing adaptor-inducing interferon-β

Toll-interleukin-1-receptor (TIR)-domain-containing adapter-inducing interferon-β (TRIF) is the principle adaptor molecule to produce IFN-β in direct response to dsRNA along with its analog poly(I:C), which are both recognized by TLR3 [50]. TLR3 utilizes TRIF to activate IRF3 via TBK1 and it also participates in the activation of the NF-κB pathway by recruiting RIP1 [40]. Additionally, TRIF has been found to facilitate apoptosis through RIP1 [40]. TRIF, also known as TICAM-1, plays an essential role in the dimerization of transcription factor IRF-3, late NF-κB activation and LPS-induced phosphorylation, further leading to immune response activation and IFN-β production [51]. IRF-3 activation mainly depends on the phosphorylation of some specific serine residues by IKKs, IKK-ϵ and TBK [52–55]. TRIF activates NF-κB by direct binding to TRAF6 which further recruits IKK complex [56,57]. TRIF requires TRAM while interacting with TLR4 but TLR3 signaling via TRIF occurs independently of TRAM [58]. TRIF generally has three main domains in mammals; one highly conserved TIR domain and two proline-rich domains on the N- and C-terminal regions [59]. Signal transduction involves a unique contribution from each domain [56]. IRF3 activation heavily relies on the presence of a binding site TRAF proteins located in the N-terminal domain [56,59]. NF-κB activation and apoptosis depends on RIP1 interaction motif (RHIM) present on C-terminal domain [60–62]. In mammals, TLR4, TLR5, TLR1/TLR2 and TLR2/TLR6 rely on bridging adaptor TIRAP to facilitate recruitment of MyD88[40]. However, TLR9, TLR11, TLR13, TLR7/TLR8 and TLR2/TLR10 directly recruit MyD88 [40,63]. TLR3 is the only TLR that does not recruit MyD88 as a signaling adaptor [40,63]. TLR3 recruits TRIF directly, but TRIF is indirectly recruited to TLR4 through the bridging adaptor TRAM [40,63–65]. The TIR domain is inherent to TRIF and is tasked with the duty of engaging with the TIR domain present within TLR3, in addition to the TRAM adaptor that acts as a bridge for TLR4 [66,67]. TLR4 serves as an antecedent for both the TRIF and MyD88 dependent pathways, as it is the only receptor that utilizes TRIF, TRAM, MyD88 and TIRAP [37,53,68–70]. Direct interaction of TLR3 and TRIF involves two tyrosine residues in the cytoplasmic domain of TLR3 upon phosphorylation by epidermal growth factors ErbB1 and BTK [71,72]. Simultaneously, MyD88 and TRIF-dependent pathways distinctly constitute TLR signaling which are activated through the usage of the adaptor [73].

CD14, a GPI-anchored protein, governs the internalization of TLR4 induced by lipopolysaccharide (LPS, endotoxin) of Gram-negative bacteria and consequently activates the TRIF-dependent pathway through the engagement of TRAM and TRIF adaptor proteins in early-endosomes after receptor endocytosis [74]. The first signaling cascade involves TIRAP and MyD88 adaptor proteins and is induced in the plasma membrane [74]. Studies reveal that macrophages from TRIF-/- mice have diminished expression of IFN-β which is accordant with results observed in TLR-/- mice [75,76]. Research finding of another study showed that polyguanine treatment of LPS-induced macrophages downregulates the expression of TLR4 and TRIF, decreases the pro-inflammatory cytokine production and M1 polarization, while increases M2 macrophage polarization [77]. Moreover, macrophage stimulation with oxidized low-density lipoprotein (ox-LDL) induces the inflammatory response via TRIF pathway, which upregulates ERK and SOCS1-STAT3-NF-κB signaling pathways and elevates the levels of IL-6 and TNF-α. Silencing of TRIF rescued this phenotype [78].

1.3. TRIF-related adaptor molecule

Toll-interleukin-1-receptor(TIR)-domain-containing adapter-inducing interferon-β (TRIF)-related adaptor molecule (TRAM) is the fourth essential TIR-domain-containing adaptor protein which actively participates in Toll receptor signaling [58]. TRIF is recruited by TRAM which is myristoylated to membranes and regulated by PKCϵ [40]. Two different signaling pathways are elucidated by TLR4 administered by the TIRAP-MyD88 and TRIF-TRAM pairs of adaptor proteins, which further evoke the pro-inflammatory cytokines production along with type-I IFNs [79]. TRAM leads to activation of IRF-3, IRF-7 and NF-κB signaling similar to TRIF [58]. TLR3 and TLR4 lead to the activation of these pathways [58]. Studies reveal the downstream functioning of TRIF in both TLR3 (dsRNA) and TLR4 (LPS) signaling pathways, whereas TRAM is restricted to TLR4 [58]. During innate immune responses to LPS, MyD88-independent pathway regulation occurs by both TRIF and TRAM through LPS-TLR4 signaling [58]. Evolutionary divergence of TLR3 and TLR4 from other TLRs is mainly involved in the activation of gene expression and enhanced immune responses by combined activation of NF-κB and IRF-3 [58]. TRAM, also known as TICAM-2, acts as a bridging adaptor between TRIF and TLR4 [80] and plays an essential role in the dimerization of transcription factor IRF-3, late NF-κB activation and LPS-induced phosphorylation, further leading to immune response activation and IFN-β production [51]. TIRAP and TRAM show similar structural features, but TRAM exhibits greater sequence homology with TRIF in its TIR domain [68]. TRAM possesses a cysteine residue in contrast to other TLR adaptors, at position 117 instead of the conserved proline [81]. TRAM requires this cysteine residue to form homodimers and for TRIF heterodimerization [59,81]. The major function of the TRAM/TRIF pathway is to enhance the expression of innate interferons transcriptionally, while the TIRAP/MyD88 pathway is implicated in the escalation of inflammatory cytokines like TNF-α [82]. Despite that, signals that rely on TRAM and TRIF have been observed to contribute to the expression of LPS-induced TNF-α [53]. When macrophages are stimulated with LPS, a deficiency in either TRAM or TRIF leads to a significant reduction in the amount of TNF-α that is secreted [53,74]. The proposed mechanism of TLR4 activation involves the induction of MyD88-dependent signaling at the plasma membrane followed by its internalization, which subsequently stimulates early endosomal MyD88-independent (TRIF-TRAM) signaling [83].

1.4. Myeloid differentiating factor-88

Myeloid differentiating factor 88 (MyD88) is a characteristic cytosolic adaptor molecule central to signaling in both innate and adaptive immune responses [84,85]. It is known to carry the signals downstream from the membrane receptors such as TLRs and IL-1 receptor families [32]. MyD88 is composed of three distinct domains viz. death domain (DD), an intermediate segment domain (INT) and Toll/Interleukin-1 receptor domain (TIR). The intermediate domain forms a bridge between the death and TIR domains [86]. The N-terminal DD consists of 54 to 109 aa, the INT spans from 110 to 155 aa and the TIR is longest from 155 to 296 aa [87]. MyD88 utilizes its C-terminal TIR domain to interact with the upstream receptor's TIR domain [88]. Death domain located at N-terminal is crucial for interaction with IRAK4 and for downstream signaling [89]. Studies have reported that the absence of INT is strongly linked with the dampening of MyD88 transduced signaling [90]. MyD88 is recruited differentially under the influence of different types of TLRs. TLR1/2, TLR2/6, TLR4 and TLR5 require the adaptor protein TIRAP which facilitates MyD88 recruitment to the receptor [40,63], while it is directly recruited to TLR7, TLR8 and TLR9 respectively [40,63–65]. TLR3 is an exception that does not recruit MyD88 as a signaling adaptor [40,63–65]. MyD88 is also reported to influence the activation of the signaling cascades involving transcription factors such as NF-κB, AP-1, IRF1, IRF5 and IRF7 [40]. The activation of different transcription factors is responsible for the production of various pro-inflammatory mediators [32,91,92].

Since MyD88 is observed to be majorly involved in TLR-mediated signaling, various studies have shown that its absence helps in abrogating the development of chronic inflammatory conditions [93,94]. In two distinct studies, Muzio et al. and Wesche et al. found that MyD88 is a central adaptor molecule to IL-1R signaling transduction and showed to facilitate signaling switch from IL-1R to activate NF-κB transcription factor [93,94]. Another study by Sun and Ding showed the involvement of MyD88 in transducing the signals from IFN-γ in macrophages and reported that MyD88-/- condition decreased IFN-γ-inducible protein 10 (IP-10) and TNF-α production [95]. In MyD88-/- macrophages, it has been shown that LPS-induced NF-κB signaling is impaired, while this effect was not evident in TRIF-/- macrophages [80]. In the hippocampi of SE mice, it was observed that inhibition or gene knockout of MyD88 resulted in the reduction of M1 MG/MΦ and gliosis while causing an increase in M2 MG/MΦ [96]. In another research using infectious models in MyD88 and TRIF KO mice, treated with TLR agonists, it was demonstrated that MyD88 pathway is important to induce TLR-mediated trained immunity in macrophages [97]. Macrophage specific MyD88 KO mice were protected against high-fat diet (HFD)-induced hepatic injury, lipid accumulation and fibrosis. The protective effect against liver damage is associated with decreased infiltration of macrophages in liver tissues and decreased inflammatory responses [98]. Atherosclerosis is another macrophage-mediated inflammatory disease. Investigations reported that lnc-MRGPRF-6:1 is upregulated in M1 macrophages of coronary atherosclerotic disease (CAD) patients and positively correlates with the pro-inflammatory cytokine production via TLR4-MyD88-MAPK signaling pathway [99].

1.5. SLP adaptor & C-terminal Src kinase-interacting membrane protein

Src kinase-interacting membrane protein (SCIMP) belongs to the family of pTRAP. pTRAP are kinase recruits and modulate pro-inflammatory response [100]. SCIMPs are generally composed of 150 residues, which include an extracellular domain, transmembrane domain which contains palmitoylation site, and a proline-rich cytoplasmic tail for scaffolding several signaling factors such as Lyn kinase, Grb2, CSK, SLP65/76 [101]. SCIMP has multiple phosphorylation sites (Y58, Y96 and Y120) at its cytoplasmic tail region for the recruitment of different effectors (Grb2, CSK, SLP65/76 ) to produce downstream signaling under LPS stimulation in macrophages [102]. More recently, Syk recruitment by SCIMP has been discovered, showing that TLR4 dependent Syk activation is mediated by SCIMP [103]. SCIMPs are generally expressed in B-cells, dendritic cells and macrophages [104]. SCIMP plays an important role in antigen presentation on B cells via modulating MHC-II signaling [105–107]. SCIMP, an immune-specific transmembrane adaptor, engages with TLR4 employing a TIR-non-TIR association to generate a pro-inflammatory response in macrophages [108,109]. TLR4 phosphorylation through tyrosine is crucial in signal initiation which has been implicated by various tyrosine kinases namely the Src family of tyrosine kinases (Lyn) [110], BTK [111] and SYK [112]. SCIMP acts as a scaffold for the Src family kinase, Lyn, to promote phosphorylation and activation of TLR4 [103]. This allows SCIMP to selectively induce the generation of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, IL-12 etc. downstream of TLR4 [109]. Phosphorylation of TLR-4 leads to the recruitment of MAPK Erk1/2 to the plasma membrane ruffles and macro-pinosomes that activates c-Fos, NF-κB initiating TLR mediated pro-inflammatory responses [113]. In macrophages, knockout of SCIMP inhibits the signaling mediated by various TLRs namely TLR 2, 3, 4 and 9 [114]. Indeed, SCIMP has been proposed as a universal Toll-like receptor adaptor in macrophages [109].

1.6. Growth factor receptor-bound protein 2

The adaptor protein growth factor receptor-bound protein 2 (Grb2) may recruit other proteins into the signaling pathways of macrophages [115]. Grb-2 has two SH3 domains and one SH2 domain, with the SH2 domain participating in tyrosine kinase pathways and the SH3 domain recognizing proline-rich signaling molecule sequences [115,116]. The SH3 domain of Grb2 can bind to BCAP which can inhibit TLR-mediated inflammatory signaling [117]. Grb2 exists in a monomeric-dimeric equilibrium. The monomeric Grb2 associates, via the N-terminal SH3 domain, with the mammalian homologue of the drosophila protein son-of-sevenless (SOS) and activates the MAPK signaling, while the dimeric inhibits this process. Phosphorylation of tyrosine 160 on Grb2 leads to dimer dissociation and this phosphorylated form is highly detected in various malignant types of cancer, pointing the role of monomeric-dimeric Grb2 in controlling MAPK pathway and tumour growth [118].

Grb2 has been shown to have a role in several disorders including the development of atherosclerotic lesions, since Grb2+/apoE/mice were found to be resistant to the disease [119]. Erbin interaction with Grb2 results in the activation of RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK and PI3K/AKT/FoxO3a pathways that reduce the proliferation of acute leukemia cells and increase acute myeloid leukemia cell differentiation [120]. Grb2 contribution to carcinogenesis appears to be associated with its regulatory capacity in controlling multiple miRNA synthesis and oncogene expression [121]. In the context of inflammatory driven diseases, after interacting with SAMSN1,Grb2 activates AMPKa2, preventing the LPS-induced acute lung damage [122]. In vitro studies showed that treatment of bone marrow derived macrophages (BMDMs) with ox-LDL induces MAPK activation and foam cell formation and this effect is mediated by Grb2 [119]. According to a meta-analysis, immune cell infiltration, which is crucial in the pathophysiology of CAVD, may be linked to Grb2 [123]. Consequently, it has undesirable as well as desirable functions in certain disorders [124]. Numerous studies have suggested that Grb2 plays a paradoxical role in macrophage polarization [124]. Knockdown of Grb2 reactivated alveolar macrophages to an alternative phenotype [124]. Contrary to this, HCMV IE2 alternatively activates macrophages through a Grb2/IL-4-relatedmechanism, enabling the virus's long-term survival in the host [125]. In another study in metastatic cancer, binding to Grb2 resulted in SOS1 expression, which in turn leads to CCL2-mediated alternatively activated macrophages [126]. Grb2 also plays role in monocyte/macrophage differentiation, activation and proliferation, by binding to phosphorylated CSF1R and regulating the activation of ERK signaling [127]. Therefore, Grb2 macrophage activation appears to be context-led and requires needs more study.

1.7. B-cell adaptor for P13K

B-cell adaptor for PI3K (BCAP) was initially discovered as an adaptor protein specifically expressed in B-cells. Ligation with B-cell receptor (BCR) resulted in tyrosine phosphorylation and downstream, recruitment of PI3K p85 and phosphorylation of AKT [117]. BCAP is known to possess various conserved domains that may potentially contribute in its interactions with different proteins and conduct signaling from both receptor and non-receptor tyrosine kinases [128]. Structurally the N-terminal TIR domain of BCAP is associated with a transcription factor-Ig (TIG) and 3-a-helix (3a) structural unit, armadillo repeats (ARM) and a C-terminal helical (a/a) that is common phospho-tyrosine site [129]. BCR-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of BCAP is regulated by activation of two kinases namely Btk and Syk in ITAM mediated manner and this plays a crucial role in B-cell survival and proliferation [130,131]. Recently, BCAP was shown to be a positive regulator of PI3K-AKT signaling in CD4+ T cells [132]. In macrophages, the gene pi3kap1 is known to encode BCAP [133]. Researchers found that a conserved sequence YxxM was responsible for PI3K p85 binding and therefore can act as a connecting link for the activation of PI3K via TLR signaling [134]. Another study reported that the absence of BCAP gave rise to identical colitis susceptibility induced by DSS in macrophages, similar to what was earlier demonstrated in full-body BCAP-deficient mice [129], thus highlighting that BCAP is critically important for the reduction of vulnerability to colonic inflammation and the associated diseases [135]. A significant increment in the upregulation of the reparative genes was observed in the WT BMDMs and, as expected, in BCAP-/- BMDMs did not show significant production of Arg1, Klf4 and Mmp9 after 24 and 48 h of LPS removal [135]. The TIR domain of BCAP was found to be similar to the TIR of adaptors of TLR-mediated signaling such as TIRAP and MyD88 [33,136] and that BCAP was actively involved in repressing the activation of NF-κB reporter that is present in the signaling pathway mediated by TLR4 (CD4/TLR4) [129].

1.8. Signal-transducing adaptor protein-1

The signal-transducing adaptor proteins (STAPs) have an important role in the inflammatory response and cancer progression through interaction with tyrosine phosphorylated proteins [137,138]. The STAP-1 and STAP-2 are the members of STAP adaptor proteins [137]. They are structurally homologous to pleckstrin homology domain at the N-terminal end and Src-homology 2 domain at the C-terminal [139]. However, in case of STAP-2 the C terminal also has a proline rich domain and YXXQ motif [140]. Based on yeast hybrid screening, STAP-1 was named as B cell antigen receptor downstream signaling 1 (BRDG1) [141]. Earlier STAP-1 was identified as a stem cell-specific adaptor protein and a substrate for c-kit [142]. The SH2 domain can bind with many tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins like c-kit and STAT5 [142]. Research studies of STAP-1 in macrophage activation are scarce [143]. Stoecker et al. demonstrated for the first time the expression of STAP-1 in activated macrophages and microglia [143]. Cells expressing STAP-1 were more cytotoxic and phagocytic with reduced migration, thereby elucidating the role of STAP-1 in pro-inflammatory activation of microglia [143]. Studies by Yang et al. supported the evidence of macrophage activation by alternative method [144]. In glioma, microglia and macrophages play an important role in the progression and invasiveness of cancer [145]. Increased expression of STAP-1 was found in glioma-associated microglia/macrophages (GAM), where it increases the expression of ARG-1 viaSTAT3/IL-6 pathway and inhibits phagocytosis, thus promoting alternative activation of microglia [144]. In uterine macrophages, higher expression ofCYP26A1 leads to the classically activated macrophage phenotype through STAP-1 and Slc7a2, thus producing inflammation-mediated embryo implantation, which is reduced upon CYP26A1 knock down [146]. However, the role of STAP-1 is enigmatic in macrophage polarization, as both anti-inflammatory and pro-inflammatory role has been described in microglia and macrophages respectively.

1.9. Signal-transducing adaptor protein

Signal-transducing adaptor protein (STAP-2) is structurally related to STAP-1 [140] and contains a unique C-terminal and N-terminal regions featuring combinations of PH (Pleckstrin homology) domain, SH2-like domains and proline-rich regions [147]. Being a member of the STAP family of adaptor proteins, it engages with molecules responsible for cellular signal transduction pathways, including signaling and transcriptional molecules [29]. Significantly, STAP-2 plays essential involvement in the control of both innate and adaptive immune responses [29]. STAP-2 functions as a connector molecule controlling multitude of cellular communications [148]. STAP-2 participates in cytokine signaling pathways by binding to STAT3 along with STAT5 [29].

STAP-2 exhibits the capacity to regulate multiple molecular events in the context of pathological inflammatory responses [149]. The potential of STAP-2 to bind and regulate different types of signaling and transcriptional molecules has been highlighted [150]. In TLR4 signaling, STAP-2 interacts with MyD88 and inhibitor (I)κB kinase α/β (IKK-α/β), leading to the upregulation of inflammatory cytokine production in macrophages [29]. The impairment of STAP-2 results in diminished cytokine synthesis and decreased NF-κB activation upon exposure to LPS/TLR4, indicating a potential functional role of STAP-2 in these processes [151]. On the other hand, the overexpression of STAP-2 augments these biological responses induced by LPS/TLR4 [151]. The SH2-like domain of STAP-2 is found to bind with MyD88 and IκB kinase (IKK)-αβ, but not with IL-1R-associated kinase 1 or TNFR-associated factor 6 [151]. As a result, a functional complex composed of MyD88-STAP-2-IKK-αβ is formed [151]. The augmentation of MyD88 and/or IKK-αβ-dependent signals via these interactions results in an increased NF-κB activity [151]. The protein STAP-2 was discovered to interact with c-fms, indicating a potential functional relationship between the two proteins [140]. Also, STAP-2 plays a role in the adaptive immune response, modulating TCR signaling after TCR engagement [152].

1.10. Ionized calcium-binding adaptor molecule 1

Ionized calcium-binding adaptor molecule 1 (IBA1) is a calcium-binding protein that is mainly found in microglia and macrophages [153]. IBA1 has been determined by x-ray structures to be a small, single-domain protein with two EF-hand motifs [153]. It participates in the activation of Rac and controls the actin cytoskeleton's reorganization, which results in the production of lamellipodia and membrane ruffles [154]. IBA1 contributes to membrane ruffling, phagocytosis and actin-bundling in activated microglia [155]. In an SAE rat investigation, it was discovered that decreasing IBA1 expression in the mesenteric lymph nodes lowered the classical activation of macrophages [156]. In another study, the classical activation was discovered in the glioma microenvironment of the CD8/+ animals, where CD11b+ and IBA1+ monocytes and macrophages were abundant [157]. Neoplasm of monocytic/histiocytic and DC origin do express IBA1 in a highly specific manner [158]. Human psoriasis lesions were also found to be associated with an increase in macrophages with elevated IBA1 further to classical activation [159]. Also, in canine and feline inflammatory conditions, IBA1 is found to be a helpful marker of cells of the monocyte/macrophage lineage [160]. IBA1 is also utilized as a classically activated marker in a study on chronic brain hypoperfusion-induced Sprague Dawley (SD) rats, wherein microglial/macrophage classical polarization was measured by an increased ratio of (CD68+ and CD206+)/IBA-1 immunofluorescence [161].

1.11. Caspase-recruitment domain-containing adaptor protein

The caspase-recruitment domain-containing adaptor protein (CARD9), an inflammation-associated protein, is known to initiate the inflammatory signaling pathway of NF-κB and/or MAPK [162]. Playing an indispensable part in both innate and adaptive immunity, CARD9 is a signaling protein that contains a caspase recruitment domain [162]. CARD9 comprises of two essential parts: a carboxy-terminal coiled domain and an amino-terminal. It is closely related to well-distinguished CARMA1 [163]. CARD9 is expressed in various tissues, including spleen, liver, placenta, lungs, peripheral blood, brain, bone marrow and fetal liver [164]. Macrophage and dendritic cells express CARD9 at high levels, highlighting its crucial involvement in immune cell activation and inflammatory processes [164,165]. It has been proposed that CARD9 plays a crucial role in the activation of NF-κB through dectin-1-dependent signaling in innate immunity following a fungal infection [166]. Studies have demonstrated that CARD9 signaling can collaborate with TLR/MyD88 signaling, leading to increased activation of immune cells [167]. Genetic mutations in the human CARD9 gene can lead to alterations in protein structure, reduced expression, or loss of function [162]. These have been connected with inflammatory reactions, heightened vulnerability to fungal infections [168,169], ulcerative colitis [170,171], along with the intensity of pulmonary tuberculosis [172]. CARD9 polymorphism show a positive correlation with elevated susceptibility to fungal infection and autoimmune diseases [173].

The essential role of the CARD9 adaptor has been extensively demonstrated in facilitating PRRs to activate NF-κB and MAPK, which in turn initiates a downstream inflammatory cytokine cascade and provides robust protection against microbial invasions, particularly fungal infections [162] and is responsible for regulating the innate immune signaling cascades [166]. Studies have found that the TLR3 ligand polyinosinic-polycytidylic acid and the TLR7 ligand loxoribine significantly suppress the production of IL-6, IL-12 and TNF-α in macrophages lacking CARD9 (CARD9-/-) [166,174]. CARD9 was found to be indispensable for cytokine secretions through TLR3 and TLR7, but not TLR4, TLR2, TLR5 and TLR9 [163]. Moreover, the difference in the expression of other adaptors or enzymes that interact with CARD9 could partially explain the varying ability of TLRs to recruit CARD9 [163]. CARD9-NF-κB signaling pathway is involved in peritoneal macrophages in SAP and blocking the CARD9 expression downregulates transcription activity of NF-κB and reduces the production and release of cytokines, such as TNF-α and IL-6, thereby reducing inflammation [175,176]. According to studies, after establishment of an activated macrophage model, CARD9 shRNA was classically activated, which confirmed that CARD9 shRNA interfered with CARD9 expression, resulting in significant decreases in CD86+ expression on the surface of macrophages, phosphorylation of NF-κB and secretion of the pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α and IL-6 by macrophages [176]. These results confirmed that downregulation of CARD9-NF-κB signaling pathway inhibited classical activation of macrophages [176]. Althea et al. showed enhanced alternative activation in mice lacking CARD9 [177]. The recognition of pathogenic fungi is primarily attributed to the families of C-type lectin receptors (CLRs) and TLRs [178]. Many of the members in these families use CARD9 and MyD88 as signaling adapter proteins to trigger their functions and initiate a defensive response against fungal invasion [178]. While both CLRs and TLRs activate immune responses against fungi, the observed effects of human deficiencies in either of the shared signaling adaptors indicate that CARD9 has a distinct and superior function in controlling fungal diseases in humans compared with MyD88 [179]. Individuals with genetic CARD9 deficiencies display a primary immunodeficiency disorder (PID) that leads to a heightened susceptibility to fungal infections [179].

2. Conclusion

Inflammation is a tightly regulated process, and among the various immune cells, macrophages play a crucial and central role in the initiation, maintenance and termination of inflammation. They are activated by different stimuli via different receptors and trigger downstream signaling pathways that are facilitated by adaptor proteins. These adaptor proteins serve as mediators between membrane-bound receptors and effector signaling molecules and coordinate cellular responses to external and intrinsic signals, primarily through specific interactions between proteins and phospholipids. They act as a bridge between membrane-bound receptors and effector signaling molecules. Macrophage adaptor molecules play an indispensable role in various neoplasms and chronic inflammatory diseases such as asthma, neurological diseases, rheumatoid arthritis, type 1 diabetes, atherosclerosis, endometriosis and inflammatory bowel disease. The adaptor molecules compiled in this review mainly contain the TIR domain as well as SH2, SH3, PH and CARD and targeting these domains may open up new ways to combat the inflammatory response. Overall, this review provides a detailed insight into the involvement of adaptor proteins in macrophage activation. It represents a valuable resource for future research and may expand our understanding of macrophage biology.

3. Future perspective

In the next 5–10 years, the exploration of adaptor proteins in macrophage Toll-like receptor signaling pathways is poised to advance significantly. Future research endeavors may delve deeper into uncovering the intricate mechanisms by which these adaptor proteins regulate immune responses, potentially revealing novel therapeutic targets for infectious and inflammatory diseases. Additionally, the application of advanced imaging techniques and computational modeling may provide unprecedented insights into the spatiotemporal dynamics of adaptor protein interactions within macrophages. Moreover, the integration of omics approaches, such as proteomics and single-cell transcriptomics, holds promise for deciphering the complex signaling networks orchestrated by adaptor proteins. Overall, continued interdisciplinary efforts are warranted to unravel the full spectrum of functions and therapeutic implications of adaptor proteins in macrophage-mediated immune responses.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the Indian Institute of Technology Indore (IITI) for providing facilities and other support. Sandeep Kumar Srivastava (Manipal University, Jaipur) for his insightful suggestions and proofreading of the manuscript. Department of Biotechnology (DBT), Government of India for research grant to MSB (NNP-BT/PR40197/BTIS/137/68/2023).

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the Department of Biotechnology (DBT), Government of India sponsored National Network Project to MSB (NNP-BT/PR40197/BTIS/137/68/2023).

Author contributions

Conceptualization and supervision: MSB; Writing (Original Draft): AR, SB (Shreya Bharti), RS (Rajkumar Savai), SB (Spyridoula Barmpoutsi), AW, RA, FS, RS (Rahul Sharma), RK and NH; Reviewing and editing MSB, AR, SB (Shreya Bharti), RS (Rajkumar Savai), NH. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Financial disclosure

This work was supported by the Department of Biotechnology (DBT), Government of India sponsored National Network Project to MSB (NNP-BT/PR40197/BTIS/137/68/2023). The authors have no financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

Competing interests disclosure

The authors have no other competing interests or relevant affiliations with any organization or entity with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Writing disclosure

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as: • of interest

- 1.Ginhoux F, Guilliams M. Tissue-resident macrophage ontogeny and homeostasis. Immunity. 2016;44:439–449. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.02.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • We chose this paper because it helped us to find intricate details about macrophage.

- 2.Lawrence T, Natoli G. Transcriptional regulation of macrophage polarization: enabling diversity with identity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:750–761. doi: 10.1038/nri3088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • This paper helped us to study macrophage polarization in detail.

- 3.Martinez FO, Gordon S. The M1 and M2 paradigm of macrophage activation: time for reassessment. F1000Prime Rep. 2014;6:13. doi: 10.12703/P6-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • We incorporated this paper to delve into insights of macrophage activation, aligning with our aim to present a comprehensive view of current prospectives in macrophage biology.

- 4.Brown BN, Ratner BD, Goodman SB, et al. Macrophage polarization: an opportunity for improved outcomes in biomaterials and regenerative medicine. Biomaterials. 2012;33:3792–3802. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.02.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mosser DM. The many faces of macrophage activation. J Leukoc Biol. 2003;73:209–212. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0602325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yunna C, Mengru H, Lei W, Weidong C. Macrophage M1/M2 polarization. Eur J Pharmacol. 2020;877:173090. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2020.173090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • We included this paper to deepen our understanding of the intricate balance between M1 and M2 phenotypes in macrophage polarization, which is the central theme of our manuscript.

- 7.Mosser DM, Edwards JP. Exploring the full spectrum of macrophage activation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:958–969. doi: 10.1038/nri2448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mass E, Nimmerjahn F, Kierdorf K, Schlitzer A. Tissue-specific macrophages: how they develop and choreograph tissue biology. Nat Rev Immunol. 2023;23(9):563–579. doi: 10.1038/s41577-023-00848-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moreira AP, Hogaboam CM. Macrophages in allergic asthma: fine-tuning their pro- and anti-inflammatory actions for disease resolution. J Interf Cytokine Res. 2011;31:485–491. doi: 10.1089/jir.2011.0027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Classen A, Lloberas J, Celada A. Macrophage activation: classical vs. alternative. In: Reiner NE, editor. Macrophages and Dendritic Cells. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 2009. p. 29–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Srivastava M, Saqib U, Naim A, et al. The TLR4-NOS1-AP1 signaling axis regulates macrophage polarization. Inflamm Res. 2017;66:323–334. doi: 10.1007/s00011-016-1017-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Locati M, Curtale G, Mantovani A. Diversity, mechanisms, and significance of macrophage plasticity. Annu Rev Pathol. 2020;15:123–147. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathmechdis-012418-012718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mukherjee SU, Mukherjee SA, Bhattacharya S, Sinha Babu SP. Surface proteins of Setaria cervi induce inflammation in macrophage through Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR 4)-mediated signaling pathway. Parasite Immunol. 2017;39:e12389. doi: 10.1111/pim.12389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sabroe I, Read RC, Whyte MKB, et al. Toll-like receptors in health and disease: complex questions remain. J Immunol. 2003;171:1630–1635. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.4.1630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Atri C, Guerfali F, Laouini D. Role of human macrophage polarization in inflammation during infectious diseases. IJMS. 2018;19:1801. doi: 10.3390/ijms19061801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tarique AA, Logan J, Thomas E, et al. Phenotypic, functional, and plasticity features of classical and alternatively activated human macrophages. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2015;53:676–688. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2015-0012OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murray PJ, Wynn TA. Protective and pathogenic functions of macrophage subsets. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:723–737. doi: 10.1038/nri3073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Atre R, Sharma R, Vadim G, et al. The indispensability of macrophage adaptor proteins in chronic inflammatory diseases. Inter Immunopharmacol. 2023;119:110176. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2023.110176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • We selected the paper due to its insightful exploration of a crucial aspect relevant to our manuscript's discussion on chronic inflammation.

- 19.Baig MS, Barmpoutsi S, Bharti S, et al. Adaptor molecules mediate negative regulation of macrophage inflammatory pathways: a closer look. Front Immunol. 2024;15:1355012. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2024.1355012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nathan C. Mechanisms and modulation of macrophage activation. Behring Inst Mitt. 1991;(88):200–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hibbs JB Jr. Infection and Nitric Oxide. J Infect Dis. 2002;185:S9–S17. doi: 10.1086/338005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mukherjee S, Karmakar S, Babu SPS. TLR2 and TLR4 mediated host immune responses in major infectious diseases: a review. The Brazilian Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2016;20:193–204. doi: 10.1016/j.bjid.2015.10.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chakraborty P, Aravindhan V, Mukherjee S. Helminth-derived biomacromolecules as therapeutic agents for treating inflammatory and infectious diseases: what lessons do we get from recent findings? Inter J Biolog Macromol. 2023;241:124649. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.124649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mukherjee S, Patra R, Behzadi P, et al. Toll-like receptor-guided therapeutic intervention of human cancers: molecular and immunological perspectives. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1244345. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1244345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mukherjee S, Huda S, Sinha Babu SP. Toll-like receptor polymorphism in host immune response to infectious diseases: a review. Scand J Immunol. 2019;90:e12771. doi: 10.1111/sji.12771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Debnath U, Mukherjee S, Joardar N, et al. Aryl quinolinyl hydrazone derivatives as anti-inflammatory agents that inhibit TLR4 activation in the macrophages. European J Pharmaceut Sci. 2019;134:102–115. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2019.04.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.MacMicking J, Xie Q, Nathan C. Nitric oxide and macrophage function. Annu Rev Immunol. 1997;15:323–350. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.15.1.323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Srivastava M, Baig MS. NOS1 mediates AP1 nuclear translocation and inflammatory response. Biomed Pharmacother. 2018;102:839–847. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.03.069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sekine Y. Adaptor protein STAP-2 modulates cellular signaling in immune systems. Biolog Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 2014;37:185–194. doi: 10.1248/bpb.b13-00421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wynn TA, Chawla A, Pollard JW. Macrophage biology in development, homeostasis and disease. Nature. 2013;496:445–455. doi: 10.1038/nature12034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Murray PJ, Allen JE, Biswas SK, et al. Macrophage activation and polarization: nomenclature and experimental guidelines. Immunity. 2014;41:14–20. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.06.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fitzgerald KA, Palsson-McDermott EM, Bowie AG, et al. Mal (MyD88-adapter-like) is required for Toll-like receptor-4 signal transduction. Nature. 2001;413:78–83. doi: 10.1038/35092578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Horng T, Barton GM, Medzhitov R. TIRAP: an adapter molecule in the Toll signaling pathway. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:835–841. doi: 10.1038/ni0901-835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rajpoot S, Wary KK, Ibbott R, et al. TIRAP in the Mechanism of Inflammation. Front Immunol. 2021;12:697588. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.697588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • We chose the paper because it offers valuable insights into the role of TIRAP in inflammatory process, directly supporting the focus of our manuscript.

- 35.Lannoy V, Côté-Biron A, Asselin C, Rivard N. TIRAP, TRAM, and toll-like receptors: the untold story. Mediators Inflamm. 2023;2023:2899271. doi: 10.1155/2023/2899271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baig MS, Thurston TLM, Sharma R, et al. Editorial: targeting signaling pathways in inflammatory diseases. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1241440. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1241440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Horng T, Barton GM, Flavell RA, Medzhitov R. The adaptor molecule TIRAP provides signaling specificity for Toll-like receptors. Nature. 2002;420:329–333. doi: 10.1038/nature01180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bernard NJ, O'Neill LA. Mal, more than a bridge to MyD88: mal-more than a bridge to MyD88. IUBMB Life. 2013;65:777–786. doi: 10.1002/iub.1201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Balka KR, De Nardo D. Understanding early TLR signaling through the Myddosome. J Leukoc Biol. 2019;105:339–351. doi: 10.1002/JLB.MR0318-096R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.O'Neill LAJ, Bowie AG. The family of five: TIR-domain-containing adaptors in Toll-like receptor signaling. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:353–364. doi: 10.1038/nri2079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Baig MS, Liu D, Muthu K, et al. Heterotrimeric complex of p38 MAPK, PKCδ, and TIRAP is required for AP1 mediated inflammatory response. Inter Immunopharmacol. 2017;48:211–218. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2017.04.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Belhaouane I, Hoffmann E, Chamaillard M, et al. Paradoxical roles of the MAL/Tirap adaptor in pathologies. Front Immunol. 2020;11:569127. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.569127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lu Y-C, Yeh W-C, Ohashi PS. LPS/TLR4 signal transduction pathway. Cytokine. 2008;42:145–151. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2008.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Saqib U, Baig MS. Scaffolding role of TcpB in disrupting TLR4-Mal interactions: three to tango. J Cell Biochem. 2019;120:3455–3458. doi: 10.1002/jcb.27619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rajpoot S, Kumar A, Zhang KYJ, et al. TIRAP-mediated activation of p38 MAPK in inflammatory signaling. Sci Rep. 2022;12:5601. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-09528-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • We incorporated this paper in order to augment our understanding of the pivotal role played by TIRAP in activating the p38 MAPK pathway within inflammatory signaling mechanisms, complementing the focus of our manuscript.

- 46.Rajpoot S, Srivastava G, Siddiqi MI, et al. Identification of novel inhibitors targeting TIRAP interactions with BTK and PKCδ in inflammation through an in silico approach. SAR and QSAR in Environmental Research. 2022;33:141–166. doi: 10.1080/1062936X.2022.2035817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bernard NJ, Finlay CM, Tannahill GM, et al. A critical role for the TLR signaling adapter Mal in alveolar macrophage-mediated protection against Bordetella pertussis. Mucosal Immunology. 2015;8:982–992. doi: 10.1038/mi.2014.125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rajpoot S, Kumar A, Gaponenko V, et al. Dorzolamide suppresses PKCδ-TIRAP-p38 MAPK signaling axis to dampen the inflammatory response. Future Medi Chem. 2023;15:533–554. doi: 10.4155/fmc-2022-0260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Srivastava M, Saqib U, Banerjee S, et al. Inhibition of the TIRAP-c-Jun interaction as a therapeutic strategy for AP1-mediated inflammatory responses. Inter Immunopharmacol. 2019;71:188–197. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2019.03.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Seya T, Matsumoto M, Ebihara T, Oshiumi H. Functional evolution of the TICAM-1 pathway for extrinsic RNA sensing. Immunol Rev. 2009;227:44–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00723.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tanimura N, Saitoh S, Matsumoto F, et al. Roles for LPS-dependent interaction and relocation of TLR4 and TRAM in TRIF-signaling. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;368:94–99. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.01.061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kawai T, Takeuchi O, Fujita T, et al. Lipopolysaccharide stimulates the MyD88-independent pathway and results in activation of IFN-regulatory factor 3 and the expression of a subset of lipopolysaccharide-inducible genes. J Immunol. 2001;167:5887–5894. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.10.5887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yamamoto M, Sato S, Hemmi H, et al. Role of adaptor TRIF in the MyD88-independent toll-like receptor signaling pathway. Science. 2003;301:640–643. doi: 10.1126/science.1087262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fitzgerald KA, McWhirter SM, Faia KL, et al. IKKepsilon and TBK1 are essential components of the IRF3 signaling pathway. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:491–496. doi: 10.1038/ni921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.McWhirter SM, Fitzgerald KA, Rosains J, et al. IFN-regulatory factor 3-dependent gene expression is defective in Tbk1-deficient mouse embryonic fibroblasts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:233–238. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2237236100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sato S, Sugiyama M, Yamamoto M, et al. Toll/IL-1 receptor domain-containing adaptor inducing IFN-beta (TRIF) associates with TNF receptor-associated factor 6 and TANK-binding kinase 1, and activates two distinct transcription factors, NF-κB and IFN-regulatory factor-3, in the Toll-like receptor signaling. J Immunol. 2003;171:4304–4310. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.8.4304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jiang Z, Mak TW, Sen G, Li X. Toll-like receptor 3-mediated activation of NF-κB and IRF3 diverges at Toll-IL-1 receptor domain-containing adapter inducing IFN-beta. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:3533–3538. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308496101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fitzgerald KA, Rowe DC, Barnes BJ, et al. LPS-TLR4 Signaling to IRF-3/7 and NF-κB Involves the Toll Adapters TRAM and TRIF. J Exp Med. 2003;198:1043–1055. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kusiak A, Brady G. Bifurcation of signalling in human innate immune pathways to NF-kB and IRF family activation. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2022;205:115246. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2022.115246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kaiser WJ, Offermann MK. Apoptosis induced by the toll-like receptor adaptor TRIF is dependent on its receptor interacting protein homotypic interaction motif. J Immunol. 2005;174:4942–4952. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.8.4942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Meylan E, Burns K, Hofmann K, et al. RIP1 is an essential mediator of Toll-like receptor 3-induced NF-κB activation. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:503–507. doi: 10.1038/ni1061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Han K-J, Su X, Xu L-G, et al. Mechanisms of the TRIF-induced interferon-stimulated response element and NF-κB activation and apoptosis pathways. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:15652–15661. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311629200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • We included this paper to enhance our manuscript by incorporating insights into the intricate mechanisms underlying TRIF-induced signaling, which closely aligns with our discussion of immune response activation.

- 63.O'Neill LAJ, Golenbock D, Bowie AG. The history of Toll-like receptors – redefining innate immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13:453–460. doi: 10.1038/nri3446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Choi YJ, Jung J, Chung HK, et al. PTEN regulates TLR5-induced intestinal inflammation by controlling Mal/TIRAP recruitment. FASEB J. 2013;27:243–254. doi: 10.1096/fj.12-217596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Guan Y, Ranoa DRE, Jiang S, et al. Human TLRs 10 and 1 share common mechanisms of innate immune sensing but not signaling. J Immunol. 2010;184:5094–5103. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Seya T, Oshiumi H, Sasai M, et al. TICAM-1 and TICAM-2: toll-like receptor adapters that participate in induction of type 1 interferons. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2005;37:524–529. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2004.07.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Oshiumi H, Matsumoto M, Funami K, et al. TICAM-1, an adaptor molecule that participates in Toll-like receptor 3-mediated interferon-beta induction. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:161–167. doi: 10.1038/ni886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yamamoto M, Sato S, Hemmi H, et al. TRAM is specifically involved in the Toll-like receptor 4-mediated MyD88-independent signaling pathway. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:1144–1150. doi: 10.1038/ni986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yamamoto M, Sato S, Hemmi H, et al. Essential role for TIRAP in activation of the signaling cascade shared by TLR2 and TLR4. Nature. 2002;420:324–329. doi: 10.1038/nature01182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hoebe K, Janssen EM, Kim SO, et al. Upregulation of costimulatory molecules induced by lipopolysaccharide and double-stranded RNA occurs by Trif-dependent and Trif-independent pathways. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:1223–1229. doi: 10.1038/ni1010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yamashita M, Chattopadhyay S, Fensterl V, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor is essential for toll-like receptor 3 signaling. Sci Signal. 2012;5(233):ra50. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2002581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lee K-G, Xu S, Kang Z-H, et al. Bruton's tyrosine kinase phosphorylates Toll-like receptor 3 to initiate antiviral response. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:5791–5796. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1119238109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kawai T, Kawai T. Toll-like receptor signaling pathways. Front Immunol. 2014;5:461. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ciesielska A, Matyjek M, Kwiatkowska K. TLR4 and CD14 trafficking and its influence on LPS-induced pro-inflammatory signaling. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2021;78:1233–1261. doi: 10.1007/s00018-020-03656-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Takeuchi O, Akira S. Pattern recognition receptors and inflammation. Cell. 2010;140:805–820. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Alexopoulou L, Holt AC, Medzhitov R, Flavell RA. Recognition of double-stranded RNA and activation of NF-κB by Toll-like receptor 3. Nature. 2001;413:732–738. doi: 10.1038/35099560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cai T, Xu L, Xia D, et al. Polyguanine alleviated autoimmune hepatitis through regulation of macrophage receptor with collagenous structure and TLR4-TRIF-NF-κB signaling. J Cellular Molecular Medi. 2022;26:5690–5701. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.17599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wu Y, Ye J, Guo R, et al. TRIF regulates BIC/miR-155 via the ERK signaling pathway to control the ox-LDL-induced macrophage inflammatory response. J Immunol Res. 2018;2018:1–11. doi: 10.1155/2018/6249085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kagan JC, Su T, Horng T, et al. TRAM couples endocytosis of Toll-like receptor 4 to the induction of interferon-β. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:361–368. doi: 10.1038/ni1569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lundberg AM, Ketelhuth DFJ, Johansson ME, et al. Toll-like receptor 3 and 4 signaling through the TRIF and TRAM adaptors in haematopoietic cells promotes atherosclerosis. Cardiovasc Res. 2013;99:364–373. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvt033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Oshiumi H, Sasai M, Shida K, et al. TIR-containing adapter molecule (TICAM)-2, a bridging adapter recruiting to toll-like receptor 4 TICAM-1 that induces interferon-beta. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:49751–49762. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305820200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wang L, Trebicka E, Fu Y, et al. Regulation of Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Translation of Tumor Necrosis Factor-Alpha by the Toll-Like Receptor 4 Adaptor Protein TRAM. J Innate Immun. 2011;3:437–446. doi: 10.1159/000324833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kirchhausen T, Macia E, Pelish HE. Use of Dynasore, the small molecule inhibitor of dynamin, in the regulation of endocytosis. In: Methods in Enzymology. Boston, Massachusetts: Elsevier; 2008. p. 77–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Warner N, Núñez G. MyD88: a critical adaptor protein in innate immunity signal transduction. J. Immunol. 2013;190:3–4. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1203103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Uzma S, Baig MS. Simultaneous targeting of MyD88 and Nur77 as an effective approach for the treatment of inflammatory diseases. Drug Design, Development and Therapy. 2016;10:1557–1572. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S103393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Medzhitov R, Preston-Hurlburt P, Kopp E, et al. MyD88 is an adaptor protein in the hToll/IL-1 receptor family signaling pathways. Mol Cell. 1998;2:253–258. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80136-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Saikh KU. MyD88 and beyond: a perspective on MyD88-targeted therapeutic approach for modulation of host immunity. Immunol Res. 2021;69:117–128. doi: 10.1007/s12026-021-09188-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hardiman G, Rock FL, Balasubramanian S, et al. Molecular characterization and modular analysis of human MyD88. Oncogene. 1996;13:2467–2475. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Burns K, Janssens S, Brissoni B, et al. Inhibition of interleukin 1 receptor/toll-like receptor signaling through the alternatively spliced, short form of MyD88 is due to its failure to recruit IRAK-4. J Exp Med. 2003;197:263–268. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Avbelj M, Horvat S, Jerala R. The role of intermediary domain of MyD88 in cell activation and therapeutic inhibition of TLRs. J Immunol. 2011;187:2394–2404. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.O'Neill LAJ, Fitzgerald KA, Bowie AG. The toll-IL-1 receptor adaptor family grows to five members. Trends Immunol. 2003;24:286–289. doi: 10.1016/S1471-4906(03)00115-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Dunne A, O'Neill LAJ. The interleukin-1 receptor/toll-like receptor superfamily: signal transduction during inflammation and host defense. Sci STKE. 2003;2003(171):re3. doi: 10.1126/stke.2003.171.re3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wesche H, Henzel WJ, Shillinglaw W, et al. MyD88: an adapter that recruits IRAK to the IL-1 receptor complex. Immunity. 1997;7:837–847. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(00)80402-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Muzio M, Ni J, Feng P, Dixit VM. IRAK (Pelle) family member IRAK-2 and MyD88 as proximal mediators of IL-1 signaling. Science. 1997;278:1612–1615. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5343.1612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Sun D, Ding A. MyD88-mediated stabilization of interferon-γ-induced cytokine and chemokine mRNA. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:375–381. doi: 10.1038/ni1308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Liu J-T, Wu S-X, Zhang H, Kuang F. Inhibition of MyD88 signaling skews microglia/macrophage polarization and attenuates neuronal apoptosis in the hippocampus after status epilepticus in mice. Neurotherapeutics. 2018;15:1093–1111. doi: 10.1007/s13311-018-0653-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Owen AM, Luan L, Burelbach KR, et al. MyD88-dependent signaling drives toll-like receptor-induced trained immunity in macrophages. Front Immunol. 2022;13:1044662. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.1044662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Yang B, Luo W, Wang M, et al. Macrophage-specific MyD88 deletion and pharmacological inhibition prevents liver damage in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease via reducing inflammatory response. Biochim et Biophys Acta (BBA). 2022;1868:166480. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2022.166480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Hu D, Wang Y, You Z, et al. lnc-MRGPRF-6:1 promotes M1 polarization of macrophage and inflammatory response through the TLR4-MyD88-MAPK pathway. Med Inflammat. 2022;2022:1–18. doi: 10.1155/2022/6979117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Curson JEB, Luo L, Sweet MJ, Stow JL. pTRAPs: transmembrane adaptors in innate immune signaling. J Leukoc. Biol. 2018;103:1011–1019. doi: 10.1002/JLB.2RI1117-474R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Luo L, Lucas RM, Liu L, Stow JL. signaling, sorting and scaffolding adaptors for Toll-like receptors. J Cell Sci. 2020;133:jcs239194. doi: 10.1242/jcs.239194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Luo L, Tong SJ, Wall AA, et al. Development of SH2 probes and pull-down assays to detect pathogen-induced, site-specific tyrosine phosphorylation of the TLR adaptor SCIMP. Immunol Cell Biol. 2017;95:564–570. doi: 10.1038/icb.2017.10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Liu L, Lucas RM, Nanson JD, et al. The transmembrane adapter SCIMP recruits tyrosine kinase Syk to phosphorylate Toll-like receptors to mediate selective inflammatory outputs. J Biol Chem. 2022;298:101857. doi: 10.1016/j.jbc.2022.101857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Kralova J, Fabisik M, Pokorna J, et al. The transmembrane adaptor protein SCIMP facilitates sustained dectin-1 signaling in dendritic cells. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:16530–16540. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.717157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Draber P, Vonkova I, Stepanek O, et al. SCIMP, a transmembrane adaptor protein involved in major histocompatibility complex class II signaling. Mol Cell Biol. 2011;31:4550–4562. doi: 10.1128/MCB.05817-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Yang X, Chatterjee V, Ma Y, et al. Protein palmitoylation in leukocyte signaling and function. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2020;8:600368. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2020.600368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Stepanek O, Draber P, Horejsi V. Palmitoylated transmembrane adaptor proteins in leukocyte signaling. Cell Signal. 2014;26:895–902. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2014.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Luo L, Bokil NJ, Wall AA, et al. SCIMP is a transmembrane non-TIR TLR adaptor that promotes proinflammatory cytokine production from macrophages. Nat Commun. 2017;8:14133. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Luo L, Curson JEB, Liu L, et al. SCIMP is a universal Toll-like receptor adaptor in macrophages. J Leukoc Biol. 2020;107:251–262. doi: 10.1002/JLB.2MA0819-138RR [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Smolinska MJ, Horwood NJ, Page TH, et al. Chemical inhibition of Src family kinases affects major LPS-activated pathways in primary human macrophages. Mol Immunol. 2008;45:990–1000. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2007.07.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Jefferies CA, Doyle S, Brunner C, et al. Bruton's tyrosine kinase is a toll/interleukin-1 receptor domain-binding protein that participates in nuclear factor κB activation by toll-like receptor 4. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:26258–26264. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301484200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Chaudhary A, Fresquez TM, Naranjo MJ. Tyrosine kinase Syk associates with toll-like receptor 4 and regulates signaling in human monocytic cells. Immunol Cell Biol. 2007;85:249–256. doi: 10.1038/sj.icb7100030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Lucas RM, Liu L, Curson JEB, et al. SCIMP is a spatiotemporal transmembrane scaffold for Erk1/2 to direct pro-inflammatory signaling in TLR-activated macrophages. Cell Reports. 2021;36:109662. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2021.109662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Lennartz M, Drake J. Molecular mechanisms of macrophage Toll-like receptor-Fc receptor synergy. F1000Res. 2018;7:21. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.12679.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Vidal M, Montiel J-L, Cussac D, et al. Differential interactions of the growth factor receptor-bound protein 2 N-SH3 domain with son of sevenless and dynamin. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:5343–5348. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.9.5343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Lowenstein EJ, Daly RJ, Batzer AG, et al. The SH2 and SH3 domain-containing protein GRB2 links receptor tyrosine kinases to ras signaling. Cell. 1992;70:431–442. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90167-B [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Lauenstein JU, Udgata A, Bartram A, et al. Phosphorylation of the multifunctional signal transducer B-cell adaptor protein (BCAP) promotes recruitment of multiple SH2/SH3 proteins including GRB2. J Biol Chem. 2019;294:19852–19861. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA119.009931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Ahmed Z, Timsah Z, Suen KM, et al. Grb2 monomer-dimer equilibrium determines normal versus oncogenic function. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7354. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Proctor BM, Ren J, Chen Z, et al. Grb2 Is required for atherosclerotic lesion formation. ATVB. 2007;27:1361–1367. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.106.134007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Zheng Z, Zheng X, Zhu Y, et al. miR-183-5p inhibits occurrence and progression of acute myeloid leukemia via targeting erbin. Mol Ther. 2019;27:542–558. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2019.01.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Stainthorp AK, Lin C-C, Wang D, et al. Regulation of microRNA expression by the adaptor protein GRB2. Sci Rep. 2023;13:9784. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-36996-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Jiang W, Ma C, Bai J, Du X. Macrophage SAMSN1 protects against sepsis-induced acute lung injury in mice. Redox Biology. 2022;56:102432. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2022.102432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 123.Wu L-D, Xiao F, Sun J-Y, et al. Integrated identification of key immune related genes and patterns of immune infiltration in calcified aortic valvular disease: a network based meta-analysis. Front Genet. 2022;13:971808. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2022.971808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Wang Q, Hong L, Chen M, et al. Targeting M2 macrophages alleviates airway inflammation and remodeling in asthmatic mice via miR-378a-3p/GRB2 pathway. Front Mol Biosci. 2021;8:717969. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2021.717969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Yang Y, Ren G, Wang Z, Wang B. Human cytomegalovirus IE2 protein regulates macrophage-mediated immune escape by upregulating GRB2 expression in UL122 genetically modified mice. BST. 2019;13:502–509. doi: 10.5582/bst.2019.01197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Xing F, Zhao D, Wu S-Y, et al. Epigenetic and posttranscriptional modulation of sos1 can promote breast cancer metastasis through obesity-activated c-met signaling in African-American women. Cancer Res. 2021;81:3008–3021. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-19-4031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Mun SH, Park PSU, Park-Min K-H. The M-CSF receptor in osteoclasts and beyond. Exp Mol Med. 2020;52:1239–1254. doi: 10.1038/s12276-020-0484-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Miao Y, Jiang M, Qi L, et al. BCAP regulates dendritic cell maturation through the dual-regulation of NF-κB and PI3K/AKT signaling during infection. Front Immunol. 2020;11:250. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]