Abstract

Background

Self-compassion, individual's ability to treat oneself kindly, is important for mental well-being. The Self-Compassion Scale (SCS) is the most used instrument to measure self-compassion, but the short form does not have validity evidence in adolescents.

Methods

We examined the psychometric properties of the SCS-SF (12 items) in 955 Spanish adolescents (Mage = 13.95) using Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) and reliability tests. The life satisfaction, family satisfaction, and reactive-proactive aggression were used for convergent validity.

Results

Cronbach's alpha reliability value for the total scale was .723. CFA confirmed that the six-factor model showed good fit indices with three positive dimensions: self-kindness, common humanity, and mindfulness; and three negative components: self-judgment, isolation, and over-identification (χ2 = 114.730; CFI = .966; GFI = .98; RMSEA = .045). The bifactorial model also showed an adequate fit, although with weaker values than the six-factor (ꭓ2 = 247.108; CFI = .914; GFI = .95; RMSEA = .06). The unifactorial model showed an inadequate fit. Total SCS score correlated positively with family satisfaction (r = .43; p < .001) and life satisfaction (r = .48; p < .001) and negatively with reactive aggressiveness (r = −.27; p < .001) and with proactive aggressiveness (r = −.18; p < .001). Self-kindness, common humanity, and mindfulness were associated with higher family and life satisfaction (p < .001) Self-judgment, isolation, and over-identification were associated with lower family and life satisfaction (p < .001). Self-judgment and isolation positively correlated with both reactive and proactive aggression (p < .001), while mindfulness negatively correlated with both reactive and proactive aggression (p < .01).

Conclusion

The SCS-SF is a valid and reliable instrument for assessing self-compassion in Spanish adolescents. Results suggest the six-factor model in its first validation in an adolescent population with convergent validity. The findings of this study corroborate the significance of self-compassion for the mental health of adolescents, particularly in relation to their family and life satisfaction.

Keywords: Self-compassion, Adolescent, Spanish population, Validation, Mindfulness, psychometric

1. Introduction

Self-compassion refers to the way a person responds to suffering, how they understand it, and how they pay attention to the challenging situations in their own life [1]. People with high self-compassion scores tend to treat themselves kindly in difficult situations, understand suffering as part of the human experience, and face adverse situations in a balanced, mindful, and attentive manner. On the opposite end, individuals with low self-compassion tend to blame themselves, make critical judgments in difficult situations, consider it a situation that only happens to them, or overly identify with negative emotions [1]. Self-compassion has been widely linked to psychological well-being and as a protective factor against mental health issues [2,3]. In adolescence, self-compassion has been positively linked with life satisfaction [4,5], with the quality of family relationships [6,7], and with self-control [8]. Conversely, it has been negatively associated with aggression [9,10] and with depression, anxiety, and stress [4,6].

The most internationally used instrument for measuring self-compassion is the Self-Compassion Scale [11]. The first version (26 items) was validated with North American undergraduate students and confirmed a six-factor model with three positive components: self-kindness (the ability to treat oneself with respect and acceptance, distanced from negative critical judgments), mindfulness (the capacity for full attention and balanced awareness of one's emotions and situations without being consumed by suffering), and common humanity (the understanding of suffering as human inherent quality). The model also includes three negative components: self-judgment (when individuals disapprove of themselves and are particularly critical of themselves), isolation (referring to an egocentric perspective to understand suffering as something that only happens to the person experiencing it), and over-identification (pertaining to excessive attention and identification with negative emotions related to personal failure and viewing them as definitive) [11]. SCS has been extensively validated in various countries. Most studies identify the six-factor model as the most robust option with adequate fit [12,13]. However, the use of a total score for the SCS is controversial, with studies in favour [13] and studies against using this overall score [14,15]. The SCS has undergone various adaptations, such as the short 12-item version [16] or, more recently, the 17-item version for adolescents [17]. The 12-item version is the most internationally validated.

Raes et al. [16] developed the short English and German version of the scale (SCS-SF) with 12 items, which was validated in university students and adults. These authors confirmed the six-factor model and a general higher-order self-compassion. This short version has demonstrated validity evidence with various adult populations in countries such as the United Kingdom [18], China [19], Portugal [20], Canadá [21], and Slovenia [22]. In Spain, two studies of this version have been conducted [23,24]. Specifically, García-Campayo et al. conducted the translation process of the 12 items version and validated the scale with 283 doctors and nurses using Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) [23]. Additionally, they used dimensions of mindfulness, depression, anxiety, and perceived stress for the construct validity of self-compassion in an adult population [23]. In their validation with health service workers, the six-factor model showed good fit indices. Furthermore, the total score, with Cronbach's alpha values of .85, showed a negative association with depression, anxiety, and perceived stress, and a positive relationship with mindfulness [23] consistent with other validations of the 12-item version [20,22]. However, other psychometric studies confirm the adequate fit of the bifactorial model [21,24]. Specifically, Lluch-Sanz et al. replicated the psychometric study of the SCS-SF with 115 nurses in Spain using CFA [24]. They found better fit indices in the two-factor model: positive components of self-compassion (self-kindness, common humanity, and mindfulness) with a reliability of .806 and negative components (self-judgment, isolation, and over-identification) with a reliability of .841.

1.1. Current study

Various studies have underscored the importance of validating the SCS-SF across different cultures and countries [5,7,25]. It has been proposed that self-compassion may vary depending on whether an individual grows up in a society with collective aims, more individualistic societies, systems that promote beliefs based on self-kindness, or demanding systems on the individual [5]. Self-compassion has also been found to be a construct that predicts well-being and transcends various worldviews across different societies [5]. Furthermore, it is suggested that the SCS items function adequately regardless of the translated language [25]. However, it is necessary to assess the psychometric properties of the SCS-SF in each context to facilitate understanding of the construct, to make cross-cultural comparisons, and to address possible sociocultural differences [5]. Compared to other countries, Spain records one of the highest scores of self-compassion among the adult population [25], although there may be a potential data bias since the participants in Spanish studies are health service workers. Additionally, cultural studies of self-compassion have focused on the adult population, with adolescence being a developmental stage that is less analysed [25].

In conclusion, The SCS-SF (12 items) has been confirmed as an instrument with adequate psychometric properties for assessing self-compassion in spanish adult population [23,24]. However, the current state of the SCS-SF presents some gaps. For example, in the studies of the SCS-SF with Spanish adults, there is controversy over whether the use of the six-factor solution [23] or two-factor solution [24] is more appropriate. Additionally, these validations are restricted to a very specific population group: adults, doctors, and nurses, and therefore, with a high educational level which implies a bias in representativeness. Furthermore, there are few international studies on the SCS-SF in adolescents. Specifically, there is only preliminary evidence with adolescents in a Peruvian context [26]. This study was conducted with 365 Peruvian adolescents using CFA a nd supports the bifactorial model but does not conduct an analysis of convergent validity nor reports on the reliability of the total self-compassion score [26].

For these reasons, we aim to analyze the psychometric properties of the SCS-SF in Spanish adolescents through item analysis, reliability, confirmatory analysis (unifactorial, bifactorial and six-factor model), and convergent validity. Specifically, three models of the SCS-SF will be tested using the robust maximum likelihood method, reliability will be assessed using Cronbach's alpha coefficient, and convergent analysis with family satisfaction, life satisfaction, and aggression.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

The sample consisted of 955 Spanish adolescents (49.78 % females, 50.22 % males) aged between 11 and 18 years (M = 13.95; SD = 1.42). Regarding age, 43.45 % were in early adolescence (11–13 years), 42.41 % were in middle adolescence (14–15 years), and 14.14 % were in late adolescence (16–18 years). The family structure consisted of 69.07 % two-parent families, 13.91 % single-parent families, and 17.02 % reconstituted families. In terms of educational level, 97.23 % of the adolescents were enrolled in compulsory secondary education, while 2.77 % were pursuing an intermediate vocational training program.

2.2. Instruments

-

—

Background questionnaire. It includes sociodemographic characteristics such as sex, age, family structure and educational level.

-

—

Self-Compassion Scale Short Form (SCS-SF) [16,23]. The validated Spanish translation by the original authors was used [23]. It evaluates self-compassion through 12 items distributed into 6 dimensions: self-kindness (items 2 and 6), self-judgement (items 11 and 12), common humanity (items 5 and 10), isolation (items 4 and 8), mindfulness (items 3 and 7), and over-identification (items 1 and 9). To compute a total self-compassion score, items from self-judgment, isolation, and over-identification have to be reversed. It uses a Likert scale from 1 (almost never) to 5 (almost always). Higher scores indicate higher self-compassion. More information about this instrument has been provided in the introduction.

-

—

Family Satisfaction Scale (FSC) [27,28]. It evaluates the degree of family satisfaction through 10 items. It uses a Likert scale between 1 (Very dissatisfied) to 5 (Very satisfied). Higher scores indicate a higher degree of family satisfaction. In the present study, Cronbach's alpha value was .91.

-

—

The Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) [29,30]. It assesses the degree of life satisfaction using 5 items (that are answered on a Likert scale from 1 (Totally disagree) to 7 (Totally agree). Higher scores indicate a higher degree of life satisfaction. In the present study, Cronbach's alpha value was .79.

-

—

Reactive-Proactive Aggression Questionnaire (RPQ) [31,32]. It evaluates reactive and proactive aggression in adolescents. It is composed of 23 items distributed into two dimensions: proactive-instrumental aggression and reactive-hostile dimension. It uses a frequency scale from 0 (never) to 2 (often). Higher scores indicate more reactive or proactive aggression. In the present study, Cronbach's alpha for the total scale was .89.

2.3. Procedure

Data collection was conducted within the scope of the project Incorporation of Evidence-Based Good Practices in the Preventive Program. This project is developed in Andalusia, the largest region in the south of Spain, with the purpose of evaluating a prevention program for problems in adolescence [33]. All scales incorporated into the project had previously been translated into Spanish and subjected to psychometric studies in Spanish adolescents [28,29,32], except for the SCS-SF. This scale is published in open access allowing unrestricted use [23]. In this validation, the translation made by Spanish authors for the adult population was respected, and no adaptations were made for the adolescent population [23].

In this psychometric study, a community sample of adolescents was initially selected through probabilistic sampling from the region of Andalusia by randomly selecting 50 % of the provinces, ensuring representation from the southwest, south-central, and southeast of Spain. Subsequently, intentional sampling was employed across these regions to select high schools. Twelve high schools were intentionally contacted as they had previously participated in research on adolescents. Eight high schools participated in the study. Within each school, data were gathered from students spanning all educational levels between the ages of 11 and 18. Before data collection, families were informed of the study's purpose via an informational sheet prepared by the research team that was sent by the teachers. Families also received a consent form which they had to complete and send back to the schools for their children to participate in the study. 8.5 % of the contacted families refused to participate. Likewise, the adolescents received an informational sheet about the study objectives at the time of data collection and agreed to participate. 2.1 % of the adolescents refused to participate in the study before filling out the questionnaires.

A project researcher oversaw the process to ensure adherence to appropriate data collection procedures. Students spent between 35 and 50 min completing the informed consent and questionnaires. Confidentiality and anonymity were assured. For this purpose, no identifying data appeared on the questionnaires. The adolescents generated an alphanumeric code at the beginning of the questionnaire to identify them in case they later wished their data to be destroyed. No adolescent refused to participate in the research once the questionnaires were completed.The research adhered to the guidelines of the Helsinki Declaration and received approval from the Research Ethics Committee of Loyola University.

2.4. Data analysis

First, we carried out the item analysis by obtaining for each item on the SCS-SF the values of means, standard deviations, skewness, and kurtosis. Second, validity evidence based on the internal structure of the scale was analysed by conducting a Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) to test the dimensionality of the SCS-SF. Validity evidence based on internal structure examines the manner in which the relationships between items underlying the test support the proposed interpretation of the scores. Three models were tested: a) original six-factors model [11], b) bifactorial model (1. self-kindness, common humanity, and mindfulness/2. self-judgement, isolation, and over-identification); and c) unidimensional model. The robust maximum likelihood method was used, and the following indices were considered: Chi-square (χ2), Comparative Fit Index (CFI) Goodness of Fit Index (GFI), and Adjusted Goodness-of-Fit Index (AGFI), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA)and Standardized Root Mean-Square Residual (SRMR). Based on Hu and Bentler [34] and McDonald and Ho [35], the criteria for the various model fit indices of CFA were as follows: acceptable fit when CFI, GFI, and AGFI >.90, and good fit when RMSEA <.06. Once the models were designed, we calculated the standardised estimates and observed each model fit summary in the output. Furthermore, validity evidence based on the correlation between related variables was analysed. This form of evidence of validity has been historically designated as criterion-related validity and it is adequate to evaluate the manner in which the test scores are anticipated to be associated with the external variables. To provide convergent validity, the Pearson's correlation analysis between SCS-SF and family satisfaction, life satisfaction, and reactive and proactive aggressiveness was performed. Finally, the internal consistency of the SCS-SF was analysed considering Cronbach's α coefficient, discrimination indices, and Cronbach's α value if the item was deleted. IBM SPSS Statistics and AMOS 23 software were used for the data analysis.

3. Results

3.1. Item analysis

Table 1 presents the item analysis of the SCS. The item with the highest mean was item 2 (3.35) while the lowest score was obtained for item 10 (2.64). The median of all the items on the scale was 3. Furthermore, all items were answered using the full range of the scale of values from 1 to 5. Skewness values ranged from −.35 to .18, and the kurtosis values were between −1.40 to −.73.

Table 1.

Item analysis of the SCS-SF.

| M | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis | Discrimination index | Cronbach α if item deleted | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item 1 | 2.75 | 1.25 | .152 | −1.028 | .346 | .706 |

| Item 2 | 3.35 | 1.15 | −.249 | −.751 | .282 | .714 |

| Item 3 | 3.30 | 1.26 | −.292 | −.938 | .418 | .697 |

| Item 4 | 3.24 | 1.49 | −.206 | −1.400 | .404 | .698 |

| Item 5 | 3.16 | 1.31 | −.158 | −1.058 | .220 | .723 |

| Item 6 | 3.21 | 1.40 | −.217 | −1.224 | .499 | .684 |

| Item 7 | 3.34 | 1.21 | −.351 | −.737 | .377 | .703 |

| Item 8 | 3.08 | 1.38 | −.089 | −1.218 | .444 | .692 |

| Item 9 | 3.06 | 1.44 | −.048 | −1.365 | .503 | .683 |

| Item 10 | 2.64 | 1.21 | .181 | −.881 | .073 | .738 |

| Item 11 | 3.20 | 1.29 | −.137 | −1.033 | .284 | .714 |

| Item 12 | 3.29 | 1.29 | −.299 | −.966 | .396 | .700 |

Note: M = mean; SD = standard deviation.

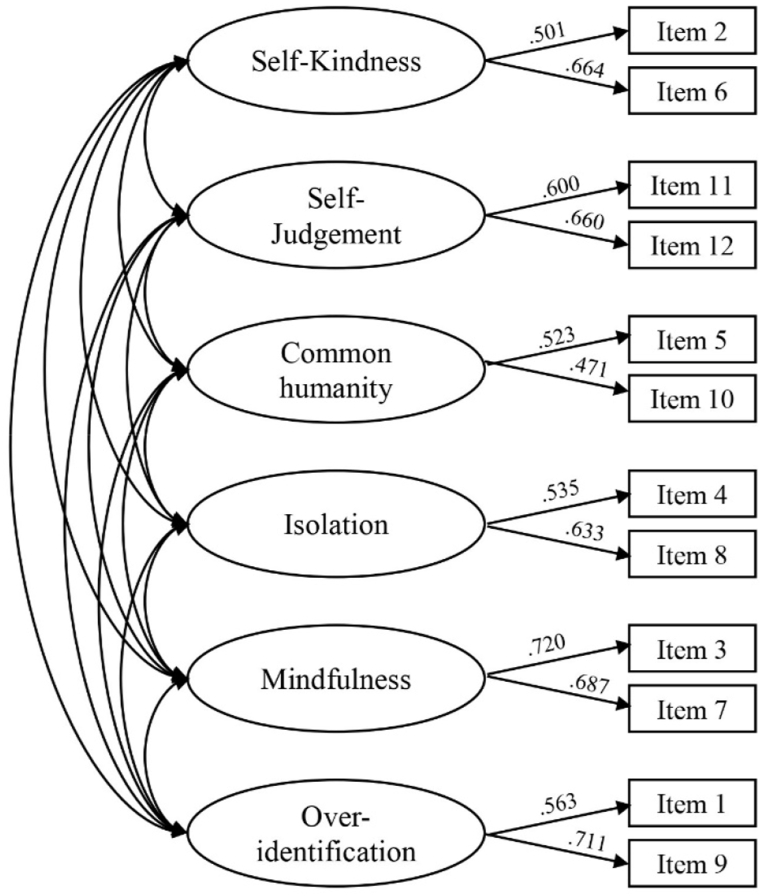

3.2. Validity evidence

The CFA showed that the original six-factor model of the SCS had a good fit for the studied population: χ2 = 114.730; CFI = .966; GFI = .98; AGFI = .96; SRMR = .04; RMSEA = .045 (.03–.05), providing validity evidence of the internal structure of the instrument (see Fig. 1). The bifactorial model also showed an adequate fit, although with weaker values than the six-factor (χ2 = 247.108; CFI = .914; GFI = .95; AGFI = .93; SRMR = .06; RMSEA = .062 (.054–.07). The unidimensional model did not show an adequate fit (χ2 = 970.662; CFI = .593; GFI = .801; AGFI = .713; SRMR = .125; RMSEA = .133 (.126–.141).

Fig. 1.

Path diagram of the six-factors model of the SCS-SF.

The six dimensions from the original model were mostly significantly correlated between them. The strongest association was found between isolation and overidentification (r = .63; p < .001), while the weakest was obtained between self-judgement and humanity (r = .07; p < .05). Only the associations between humanity and isolation and overidentification were not significant. Thus, these findings encourage the use of a total score of the SCS.

Regarding convergent validity analysis, the results showed significant associations between dimensions of SCS and relative variables. Tree positive dimensions of SCS (self-kindness, common humanity and mindfulness) directly and significantly correlated to family satisfaction and life satisfaction and three negative dimensions of SCS (self-judgment, isolation and over-identification) negatively and significantly correlated to family satisfaction and life satisfaction. Additionally, self-kindness and mindfulness negatively and significantly correlated to reactive and proactive aggressiveness. However, self-judgment and isolation directly and significantly correlated to reactive and proactive aggressiveness. Over-identification positively and significantly correlated with reactive aggression but not with proactive aggression (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Validity evidence based on correlations between SCS dimensions with related variables.

| FS | LS | RPQ-R | RPQ-P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCS - Self-kindness | .37*** | .42*** | −.09** | −.04 |

| SCS - Self-judgment | −.18*** | −.24*** | .20*** | .19*** |

| SCS - Common humanity | .22*** | .18*** | .00 | .06 |

| SCS - Isolation | −.29*** | −.33*** | .21*** | .18*** |

| SCS - Mindfulness | .28*** | .29*** | −.17*** | −.08* |

| SCS - Over-identification | −.21*** | −.26*** | .28*** | .17 |

Note. FS = family satisfaction; LS = life satisfaction; RPQ-R = reactive aggressiveness; RPQ-P = proactive aggressiveness. ***p < .001; **p < .01; *p < .05.

3.3. Reliability

The SCS showed an adequate Cronbach's alpha reliability value (α = .723) for the total sample of adolescents. Item 6 (.499) and item 9 (.503) showed the strongest correlations with the total scale. However, item 10 barely correlated with the total scale (.073). showing a low discrimination index that promotes its elimination. The correlations between the scale and the rest of the items were all optimal and greater than .20. indicating adequate discrimination indices of the items from the SCS. Regarding the analysis of Cronbach's alpha if the item is eliminated, results showed that only the elimination of item 10 would improve the reliability of the scale, increasing slightly to .738 (see Table 1).

4. Discussion

This psychometric study represents the first validity evidenceof the SCS-SF with adolescent population incorporating reliability, confirmatory analysis, and convergent validity. In terms of psychometric robustness, this is one of the international validations of the short form of SCS with the highest number of participants in the Spanish language, covering both adolescent and adult populations [23,24,26]. Moreover, in Spain, previous psychometric studies have been exclusively conducted with a distinct demographic: adults with advanced educational levels who are professionals such as doctors and nurses [23,24]. Therefore, this study constitutes the first evidence of validity in Spain of the SCS-SF in a broad community sample and confirms the instrument for measuring self-compassion in adolescence. Additionally, given the tendency for the SCS items to show good psychometric properties regardless of the translated language [25], this study confirms the short form as a valid scale for measuring self-compassion in adolescents, which could be translated and validated with adolescents from other countries. The convergent analyses that demonstrated the positive relationship of self-compassion with life and family satisfaction, and the negative relationship with aggression, support conceptualizing self-compassion as a dimension related to good mental health in adolescents, as has already been extensively reported with the adult population.

The results were consistent with the proposed six-factor model advocated by the original authors [11,13]. Thus, the six factors are confirmed in line with other validations of the short form in the adult population [20,22,23]: self-kindness, common humanity, and mindfulness (positive components) and self-judgment, isolation, and over-identification (negative components). According to other authors [21,24,26], the bifactorial model also demonstrated adequate fit, though it showed less psychometric robustness than the six-factor model. However, the unifactorial model did not achieve a good fit. In line with previous studies [14,15], the fact that half of the scale's items are reversed might hinder the validity of the unifactorial model.

The six-factor model aligns with the theoretical assumption of self-compassion that underpinned the scale's design [11]. The original authors already conceptualized that self-compassion can be understood through six related yet independent dimensions: self-kindness, common humanity, mindfulness, self-judgment, isolation, and over-identification [11]. Although the SCS has undergone multiple international psychometric studies, recently the authors have suggested that there is a growing tendency to recognize the six-factor solution as the most appropriate and with the best fit indices [2]. In adolescents, less studied than the adult population, similar results have been found in the validation of the long version with Portuguese adolescents in a sociocultural context similar to the Spanish [6]. That the six-factor solution achieves better fit indices than the bifactorial solution provides strong support for the distinct nature of each component in conceptualizing the construct of self-compassion in the adolescent population.

Regarding reliability, the Cronbach's alpha reached appropriate levels of over .70. This reliability is slightly lower than that found in previous studies with the Spanish adult population [23,24]. Although the removal of item 10 might enhance the overall scale reliability, we propose preserving the item given that the increase in overall reliability is not significant and this item has a significant loading in the common humanity subscale. However, in line with psychometric studies in adolescents [26,36], to increase reliability, small adaptations of the language for better comprehension by adolescents may be recommended, replacing abstract or general terms with words commonly used by youth. Specifically, for the SCS-SF, there is a preliminary version that adapts the adult language to adolescents in the Latin American population [26]. In this study, the translated version of the SCS-SF for Spanish adults was used, achieving an adequate reliability value, although small language adaptations may be recommended [26].

Convergent validity confirms the strength of the SCS-SF to relate self-compassion dimensions with other variables. According to other studies [4,6,7], life and family satisfaction positively correlated with self-kindness, common humanity, and mindfulness, and negatively correlated with self-judgment, isolation, and over-identification. Specifically, the relationship between self-compassion and life satisfaction has also been reported in cross-cultural studies [5]. However, until now, there was no evidence of this among the Spanish population. Therefore, the convergent validity of self-compassion with life satisfaction is consistent with global evidence. This strong relationship between self-compassion and life satisfaction indicates the value of self-compassion in individuals' mental health. Furthermore, concerning family satisfaction and self-compassion, the results are in line with the study involving Portuguese adolescents, which reports greater self-compassion when warm family environments are perceived [6]. This association occurs in the expected direction in both the positive and negative components of self-compassion. Therefore, growing up in emotionally responsive systems with appropriate demands seems to promote an adolescent's emotional balance, kindness towards themselves, and the ability to understand situations of suffering as something possible for all individuals.

Additionally, although the relationship between aggression and self-compassion has been previously contested with some authors noting a negative correlation [9,10] and others observing no significant relationship [8], the data from this study supports a negative relationship between self-compassion and aggression. Moreover, the fact that not all components of self-compassion are related to reactive and proactive aggression indicates the independence among components and supports the pertinence of the six-factor model. It was noted that proactive aggression negatively correlates with mindfulness. This supports mindful self-compassion as an intervention to promote self-compassion through mindfulness with the goal of enhancing individual mental health [37]. Additionally, proactive aggression is negatively related to self-judgment and isolation. Thus, initiated aggression is associated with negative self-judgments by adolescents about themselves and with social elements like feeling isolated or feeling less happy than others. Neurocognitive studies have demonstrated that during adolescence, inhibitory mechanisms of impulse control are still developing, and thus, there is a greater emotional hyperactivation [38]. This may explain why adolescents who are more capable of maintaining their emotions in balance (mindfulness) exhibit less aggression, both proactive and reactive, compared to adolescents who tend to engage in negative self-judgments and socially compare and isolate themselves. In summary, the convergent validity provides evidence that relate self-compassion as a protective factor for adolescent adjustment [6,39].

The limitations of this study can be associated with the non-probabilistic, intentional sampling in the selection of high schools, despite achieving a high number of adolescents and a variety of institutions in the south of Spain. Thus, the generalizability of findings is limited by sampling bias. Likewise, no data is presented segmented by sex or age that might help understand the scale's invariance across different groups. As the six dimensions of the SCS contained only 2 items, it was impossible to analyze the reliability of each factor. Additionally, since participants were only evaluated once, it was not possible to conduct a test-retest analysis. The results of this study should be interpreted with caution. For future research, employing more rigorous sampling methods, evaluating diverse populations, and examining potential variables as mediators or moderators of the found relationships would be beneficial.

In terms of practical implications, interventions based on promoting self-compassion, such as mindful self-compassion [37] and compassion-focused therapy [40], are increasingly common to enhance mental health. Indeed, self-compassion is understood as a skill that can be trained, as reported in the results of a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of self-compassion interventions [2,41]. Therefore, having the SCS-SF available in the Spanish context can facilitate the assessment of the adolescent population and the study of the effectiveness of interventions that promote this construct. Specifically, in Spain, various interventions have been implemented that promote dimensions related to self-compassion to prevent behavioral problems [33,42]. Having valid measurement instruments could enhance the assessment of adolescents and the evaluation of the effectiveness of interventions that foster self-compassion. Additionally, the confirmation of the six-factor model can aid in the design of psychoeducational and psychotherapeutic interventions where each aspect of self-compassion is promoted. This six-factor model is valuable as it allows for a more complex understanding of self-compassion and enables its enhancement through the training of each component.

5. Conclusions

The SCS-SF, which has been widely validated in adults until now, is also confirmed as a useful instrument for measuring self-compassion in adolescents with good reliability indicators for the various subscales. The six-factor model is confirmed as the model with the best psychometric indices with three positive components: self-kindness, common humanity, and mindfulness, and three negative components: self-judgment, isolation, and over-identification. In convergent validity, the self-compassion components show a significant and direct relationship with life and family satisfaction in the expected direction. This relationship also exists with reactive aggression, except with common humanity. Finally, the strongly positive association of isolation and self-judgment with proactive aggression stands out. This study provides positive evidence for the use of the SCS-SF (12-item version) with six subscales to measure self-compassion in adolescents. The results support the robustness of the SCS-SF as a multidimensional measure of self-compassion in Spanish adolescents.

Ethics approval and consent to participate. The study was previously approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Loyola University. The research adhered to the guidelines of the Helsinki Declaration. Informed, written consent was obtained from all participants.

Consent for publication. We confirm that all authors have approved the manuscript for submission and publication.

Availability of data and materials. The research data has been deposited in a repository. Link: 10.6084/m9.figshare.26403727.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Jesús Maya: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Investigation, Conceptualization. Ana Isabel Arcos-Romero: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Validation, Methodology, Formal analysis. Carmen R. Rodríguez-Carrasco: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Data curation. Victoria Hidalgo: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- 1.Neff K.D. The Self-Compassion Scale is a valid and theoretically coherent measure of self-compassion. Mindfulness. 2016;7:264–274. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neff K.D. Self-compassion: theory, method, research, and intervention. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2023;74:193–218. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-032420-031047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zessin U., Dickhäuser O., Garbade S. The relationship between Self-Compassion and well-being: a meta-analysis. Appl Psychol Health Well Being. 2015;7(3):340–364. doi: 10.1111/aphw.12051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bluth K., Blanton P.W. The influence of self-compassion on emotional well-being among early and older adolescent males and females. J. Posit. Psychol. 2015;10(3):219–230. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2014.936967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Neff K.D., Pisitsungkagarn K., Hsieh Y.P. Self-compassion and self-construal in the United States, Thailand, and taiwan. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 2008;39(3):267–285. doi: 10.1177/0022022108314544. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cunha M., Xavier A., Castilho P. Understanding self-compassion in adolescents: validation study of the Self-Compassion Scale. Pers and Individ Differ. 2016;93:56–62. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klingle K.E., Van Vliet K.J. Self-Compassion from the adolescent perspective: a qualitative study. J. Adolesc. Res. 2019;34(3):323–346. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dávila-Gómez M., Dávila-Pino J., Dávila-Pino R. Self-compassion and predictors of criminal conduct in adolescent offenders. J. Aggress. Maltreat. Trauma. 2020;29(8):1020–1033. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barry C.T., Loflin D.C., Doucette H. Adolescent self-compassion: associations with narcissism, self-esteem, aggression, and internalizing symptoms in at-risk males. Pers Individ Differ. 2015;77:118–123. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang Q.F., Xie R.B., Zhang R., Ding W. Harsh childhood discipline and developmental changes in adolescent aggressive behavior: the mediating role of self-compassion. Behav. Sci. 2023;13(9):725. doi: 10.3390/bs13090725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Neff K.D. The development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self Ident. 2003;2(3):223–250. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martínez-Ramos N., Cárdenas L., Aguirre-Acevedo D.C. Colombian adaptation of the self-compassion scale (SCS) Psicothema. 2022;34(4):621–630. doi: 10.7334/psicothema2022.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Neff K.D., Tóth-Király I., Yarnell L.M., Arimitsu K., Castilho P., Ghorbani N., et al. Examining the factor structure of the Self-Compassion Scale in 20 diverse samples: support for use of a total score and six subscale scores. Psychol. Assess. 2019;31(1):27–45. doi: 10.1037/pas0000629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Halamová J., Kanovský M., Petrocchi N., Moreira H., López A., Barnett M., et al. Factor structure of the self-compassion scale in 11 international samples. Meas Eval Couns Dev. 2021;54(1):1–23. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Muris P. A protective factor against mental health problems in youths? A critical note on the assessment of Self-Compassion. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2016;25:1461–1465. doi: 10.1007/s10826-015-0315-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Raes F., Pommier E., Neff K.D., Van Gucht D. Construction and factorial validation of a short form of the Self‐Compassion Scale. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2011;18(3):250–255. doi: 10.1002/cpp.702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Neff K.D., Bluth K., Tóth-Király I., Davidson O., Knox M.C., Williamson Z., et al. Development and validation of the self-compassion scale for youth. J. Pers. Assess. 2021;103(1):92–105. doi: 10.1080/00223891.2020.1729774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kotera Y., Sheffield D. Revisiting the Self-Compassion Scale-Short Form: stronger associations with self-inadequacy and resilience. SN Compr Clin Med. 2020;2(6):761–769. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meng R., Yu Y., Chai S., Luo X., Gong B., Liu B., et al. Examining psychometric properties and measurement invariance of a Chinese version of the Self-Compassion Scale-Short Form (SCS-SF) in nursing students and medical workers. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2019;12:793–809. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S216411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Castilho P., Pinto-Gouveia J., Duarte J. Evaluating the multifactor structure of the long and short versions of the self-compassion scale in a clinical sample. J. Clin. Psychol. 2015;71(9):856–870. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Babenko O., Guo Q. Measuring self-compassion in medical students: factorial validation of the Self-Compassion Scale-Short form (SCS-SF) Acad Psychiatry. 2019;43(6):590–594. doi: 10.1007/s40596-019-01095-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Uršič N., Kocjančič D., Žvelc G. Psychometric properties of the Slovenian long and short version of the Self-Compassion Scale. Psihologija. 2018;52(2):107–125. [Google Scholar]

- 23.García-Campayo J., Navarro-Gil M., Andrés E., Montero-Marin J., López-Artal L., Demarzo M.M.P. Validation of the Spanish versions of the long (26 items) and short (12 items) forms of the Self-Compassion Scale (SCS) Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2014;12(4):1–9. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-12-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lluch-Sanz C., Galiana L., Vidal-Blanco G., Sansó N. Psychometric properties of the Self-Compassion Scale-Short Form: study of its role as a protector of Spanish nurses professional quality of life and well-being during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Nurs Rep. 2022;12(1):65–76. doi: 10.3390/nursrep12010008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tóth-Király I., Neff K.D. Is self-compassion universal? Support for the measurement invariance of the Self-Compassion Scale across populations. Assessment. 2021;28(1):169–185. doi: 10.1177/1073191120926232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Travezaño-Cabrera A., Elguera-Cuba A. Preliminary evidence of validity and reliability of the Self-Compassion Scale-Short Form in Peruvian adolescents. Acad. (Asunción) 2022;9(2):209–216. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Olson D.H., Wilson D.M. In: Family Inventories Used in a National Survey of Families across the Family Life Cycle. Olson D.H., McCubbib H.I., Barnes H., Larsen A., Muxen M., Wilson M., editors. University of Minnesota; St. Paul, MN: 1982. Family satisfaction; pp. 78–92. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vielva I., Pantoja L., Abeijón A. Instituto Deusto de Drogodependencias, Universidad de Deusto; 2001. Las familias y sus adolescentes ante las drogas. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Atienza F.L., Pons D., Balaguer I., García-Merita M. Propiedades psicométricas de la Escala de Satisfacción con la Vida en adolescentes. Psicothema. 2000;12(2):314–319. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Diener E.D., Emmons R.A., Larsen R.J., Griffin S. The satisfaction with life scale. J. Pers. Assess. 1985;49(1):71–75. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Raine A., Dodge K., Loeber R., Gatzke-Kopp L., Lynam D., Reynolds C., et al. The reactive-proactive aggression questionnaire: differential correlates of reactive and proactive aggression in adolescent boys. Aggress. Behav. 2006;32(2):159–171. doi: 10.1002/ab.20115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rodríguez J.M.A., Fernández M.E.P., Ramírez J.M. Cuestionario de agresión reactiva y proactiva: un instrumento de medida de la agresión en adolescentes. Rev Psicopatol Psicol Clin. 2009;14(1):37–49. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hidalgo V., Hidalgo M.P., Lorence B., Sánchez A., Maya J., Quintero M.A., Rodríguez-Carrasco C.R. Sistematización del programa preventivo para menores en situación de conflictividad en el ámbito familiar en la comunidad de Andalucía: Programa NAYFA. Apunt. Psicol. 2022;40(3):151–162. doi: 10.55414/ap.v40i3.1417. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hu L.T., Bentler P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Modeling. 1999;6(1):1–55. [Google Scholar]

- 35.McDonald R.P., Ho M.H.R. Principles and practice in reporting structural equation analyses. Psychol. Methods. 2002;7(1):64–82. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maya J., Arcos-Romero A.I., Hidalgo V. Psychometric properties of the inventory of parents-peer attachment (IPPA) in adolescents with behavioural problems. Clin. Salud. 2023;34(3):131–137. doi: 10.5093/clysa2023a13. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Germer C.K., Neff K.D. Guilford Press; New York: 2019. Teaching the Mindful Self-Compassion Program: A Guide for Professionals. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Romer D. Adolescent risk taking, impulsivity, and brain development: implications for prevention. Dev. Psychobiol. 2010;52(3):263–276. doi: 10.1002/dev.20442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pullmer R., Chung J., Samson L., Balanji S., Zaitsoff S. A systematic review of the relation between self-compassion and depressive symptoms in adolescents. J. Adolesc. 2019;74:210–220. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2019.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gilbert P. Routledge; London: 2010. Compassion Focused Therapy: Distinctive Features. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ferrari M., Hunt C., Harrysunker A., Abbott M.J., Beath A.P., Einstein D.A. Self-compassion interventions and psychosocial outcomes: a meta-analysis of RCTs. Mindfulness. 2019;10(8):1455–1473. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Maya J., Hidalgo V., Jiménez L., Lorence B. Effectiveness of scene-based psychodramatic family therapy (SB-pft) in adolescents with behavioural problems. Health Soc. Care Community. 2020;28:555–567. doi: 10.1111/hsc.12888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]