Graphical abstract

Keywords: Groenlandicine, Osteosarcoma, Cisplatin resistance, Apoptosis

Highlights

-

•

Groenlandicine suppresses osteosarcoma cell proliferation while promoting apoptosis.

-

•

Groenlandicine as an active ingredient in traditional Chinese medicine.

-

•

Overcome cisplatin resistance in osteosarcoma by modulating the Bcl2/BAX/Caspase-3/Caspase-9 pathway.

-

•

A potential agent for reversing cisplatin in osteosarcoma treatment.

Abstract

Groenlandicine is a protoberberine alkaloid isolated from Coptidis Rhizoma, a widely used traditional Chinese medicine known for its various biological activities. This study aims to validate groenlandicine’s effect on both cisplatin-sensitive and cisplatin-resistant osteosarcoma (OS) cells, along with exploring its potential molecular mechanism.

The ligand-based virtual screening (LBVS) method and molecular docking were employed to screen drugs. CCK-8 and FCM were used to measure the effect of groenlandicine on the OS cells transfected by lentivirus with over-expression or low-expression of TOP1. Cell scratch assay, CCK-8, FCM, and the EdU assay were utilized to evaluate the effect of groenlandicine on cisplatin-resistant cells. WB, immunofluorescence, and PCR were conducted to measure the levels of TOP1, Bcl-2, BAX, Caspase-9, and Caspase-3. Additionally, a subcutaneous tumor model was established in nude mice to verify the efficacy of groenlandicine.

Groenlandicine reduced the migration and proliferation while promoting apoptosis in OS cells, effectively damaging them. Meanwhile, groenlandicine exhibited weak cytotoxicity in 293T cells. Combination with cisplatin enhanced tumor-killing activity, markedly activating BAX, cleaved-Caspase-3, and cleaved-Caspase-9, while inhibiting the Bcl2 pathway in cisplatin-resistant OS cells. Moreover, the level of TOP1, elevated in cisplatin-resistant OS cells, was down-regulated by groenlandicine both in vitro and in vivo. Animal experiments confirmed that groenlandicine combined with cisplatin suppressed OS growth with lower nephrotoxicity.

Groenlandicine induces apoptosis and enhances the sensitivity of drug-resistant OS cells to cisplatin via the BAX/Bcl-2/Caspase-9/Caspase-3 pathway. Groenlandicine inhibits OS cells growth by down-regulating TOP1 level.Therefore, groenlandicine holds promise as a potential agent for reversing cisplatin resistance in OS treatment.

1. Introduction

Osteosarcoma (OS), a primary malignant bone tumor, predominantly afflicts children and young adults, often resulting in poor prognosis due to its high recurrence and metastasis rates [1], [2], [3]. Currently, the MAP adjuvant chemotherapy regimen, featuring cisplatin as a first-line chemotherapeutic agent, is widely recommended [4]. However, a significant portion of patients may have a relapse of OS due to tumor resistance to cisplatin, thereby limiting chemotherapy efficacy [5], [6].

DNA topoisomerases (TOP) are DNA uncouplers ubiquitously present in cells, playing pivotal roles in various biological processes [7]. Topoisomerase 1 (TOP1), as molecular targets for anti-cancer drugs [8], corrects DNA linkage number by cleaving the phosphodiester bond in one DNA strand, subsequently rewinding and sealing it. It has been shown that the expression of both TOP1 and TOP2A is significantly increased in osteosarcoma [9]. Our prior investigations revealed that hydroxycamptothecin, a natural plant alkaloid from Camptotheca acuminata [10], synergizes with cisplatin to inhibit proliferation and induce apoptosis in OS cells as a TOP1 inhibitor. Researches has shown that natural products not only enhanced the therapeutic efficiency of cisplatin but also attenuated its toxicity [11]. In this study, utilizing the LBVS method, we identified groenlandicine, an active ingredient in traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) structurally akin to hydroxycamptothecin. Despite its potential, there exists a dearth of literature regarding the application of groenlandicine in the treatment and management of cisplatin resistance in OS.

The key to the anti-tumor effects of platinum-based drugs lies in their ability to induce tumor cell death [12], [13]. When apoptosis of tumor cells is inhibited, conventional concentrations of platinum drugs fail to trigger apoptosis, rendering tumor cells drug-resistant [14]. Apoptosis-related proteins implicated in platinum drug resistance include tumor suppressor protein p53, anti-apoptotic protein XIAP, Bcl-2 family proteins, and mitogen-activated protein kinase intracellular signaling pathway proteins [15]. The Bcl-2 family, comprising both apoptosis-inhibiting proteins like Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL, as well as pro-apoptotic proteins like BAX, plays a crucial role in apoptosis regulation. Qi et al. demonstrated that a cisplatin-containing nano-formulation significantly up-regulated BAX and down-regulated Bcl-2, reversing drug resistance in non-small cell lung cancer [16]. Similarly, Alam et al. found that knockdown of Fra-2, in combination with other drugs, decreased Bcl-xL levels and induced cell death in cisplatin-resistant oral squamous cell carcinoma, highlighting the potential of inhibiting Bcl-xL or its upstream pathway to overcome cisplatin resistance [17].

Herein, we established cisplatin-resistant SJSA-1 (SJSA-1/R) and cisplatin-resistant MG63 (MG63/R) cell lines to investigate the effects of groenlandicine on the cisplatin-resistant OS cells, the relationship between groenlandicine-induced apoptosis and cisplatin resistance in OS cells, and elucidate potential molecular mechanisms.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. LBVS method and FP2 algorithm

The SwissSimilarity platform, employing the LBVS approach, was utilized for screening potential compounds. LBVS relies on the premise that molecules sharing structural similarity also exhibit similar biological activities, with molecular description serving as the basis for structural comparison(17–19). Chemical similarity was assessed using a 2-dimensional (2D) approach, which characterizes the properties of 2D chemical structures. Molecular fingerprints (FP) were employed to represent compound chemical characteristics as vectors. Hydroxycamptothecin served as the reference compound, and compounds with structurally similar features were screened from a library of active small molecules in TCM.

2.2. Computerized protein–ligand docking

AutodockVina v1.2.2 software was employed to assess the binding energy and interaction mode between groenlandicine and TOP1 proteins. Protein Data Bank (PDB) files containing structural information of Grandisin and TOP1 were obtained. These files were converted to PDBQT format, with polar hydrogen atoms added and water molecules removed. AutodockVina facilitated the final visualization of the docking process.

2.3. Chemicals and biological reagents

Groenlandicine (purity: 99.87 %), Cisplatin (purity: 99.54 %), and SC79 (purity: 98.0 %) were purchased from MedChemExpress (MCE, USA). Annexin V–APC and propidium iodide (PI) were purchased from 4A BIOTECH. TOP1,TOP2A,B cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2), Bcl-2 − associated X protein (BAX),β-actin, caspase-3 (active/cleaved), and caspase-9 (active/cleaved) antibodies were purchased from Proteintech. Horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG and FITC conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) secondary antibodies were purchased from Proteintech. Lamin B1 Polyclonal Antibody was purchased from Bioss (China). Nuclear protein extraction kit was purchased from Beijing Solarbio Science and Technology (China).

2.4. Cell lines and cell culture

Human Embryonic Kidney 293 Cells (293T), SJSA-1, MG63 human OS cells were obtained from the American Tissue Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA). Cisplatin-resistant SJSA-1 cells (SJSA-1/R) and Cisplatin-resistant MG63 cells (MG63/R) were derived from the parental MG63 and SJSA-1 cell lines. These two cell lines were established by continuous treatment with progressively increasing concentrations of cisplatin (from 0.5 to 32 μM; throughout the passages for 9 months. Cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (Gibco) containing 10 % fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1 % penicillin–streptomycin (Gibco). Cells were cultured at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 5 % CO2.

2.5. Western blot analysis

Protein extracts were electrophoresed using 10 % sodium dodecyl sulphate − polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred onto nitrocellulose membrane (Millipore). Protein blots were incubated with the primary antibody against the protein of interest. HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG were used as secondary antibodies as previously described.

2.6. Quantitative real Time-Polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR)

According to the manufacturer’s instructions, total RNAs from cells were extracted using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen). Real-time PCR was performed using the SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (TianGen Biotech) and the PRISM 7500 real-time PCR detection system (ABI). The following human primers (Generay Bioteach Co. Ltd) were used in this study:

GAPDH F5́-CTACCTCATGAAGATCCTCACCGA-3́

GAPDH R5́-TTCTCCTTAATGTCACGCACGATT-3́

TOP1 F5́-AGAACAAGCAGCCCGAGGATG-3́

TOP1 R5́-CTGTAGCGTGATGGAGGCATTG-3́

TOP2A F 5́-TACCSCTGTCTTCAAGCCCTCCTG-3́

TOP2A R 5́-TGCTGCTGTCTTCTTCACTGTCAC-3́

2.7. Apoptosis assay

After incubation, cells were washed in cold PBS and resuspended in buffer containing annexin V–APC and PI according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The cell suspensions were analyzed by flow cytometry (FCM) (BD Biosciences).

2.8. CCK-8 assay

The Cell Counting Kit-8 was used to assess cell viability. Briefly, 1 × 105 cells were treated with various concentrations of the drug for 24 h in a 96-well plate in a total volume of 100 μL. During the last 4 h of cell culture,10 μL of CCK-8 was added into each well. The absorbance was measured using a microplate spectrophotometer (BioTek) at 450 nm. Cell viability under drug treatment was reported as a percentage of the control, and the 50 % inhibitory concentration value (IC50) was calculated using Prism 9 (GraphPad Software).

2.9. Lentivirus transfection

EGFP-, TOP1-EGFP- and TOP1-RNAi-EGFP-lentiviruses and transfection reagents were purchased from Genechem. Lentiviruses were transfected into SJSA-1, MG63 cells according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Transfection efficiency was determined as previously described.

2.10. EDU assay

EDU (5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine) is a nucleoside analog of thymidine that is doped into DNA during active DNA synthesis. Cells were cultured on slides in six-well or 96-well plates to reach the desired density and then processed for experiments. A 2-fold working solution of Edu (20 μM) was prepared using a 10 mM Edu solution, which was added to the medium containing the cells to give a final concentration of 10 μM. The 2-fold concentration of Edu solution pre-warmed to 37 °C was added in the same volume as the medium containing the cells to be tested to give a final concentration of 1-fold Edu in a 96-well plate. Incubate the cells under suitable conditions for 2 h. At the end of the incubation, the medium was removed and fixative (PBS solution containing 3.7 % formaldehyde) was added to each well and incubated for 15 min at room temperature. Afterwards, permeabilization was performed using PBS solution containing 0.5 % Triton X-100. The Click-iT reaction mixture was prepared by adding 100 μL of the reaction mixture to each slide and incubated for 30 min at room temperature away from light. Finally, cells were washed using PBS and subjected to nuclear staining or antibody labeling. Fluorescence microscopy was used to observe Red fluorescence.

2.11. Immunofluorescence (IF) and Immunohistochemical (IHC) staining

The subcellular localization of TOP1 and TOP2A was examined by immunofluorescence staining. The cells were first fixed with 4 % paraformaldehyde for 30 min at room temperature. After washing (three times) with phosphate buffered saline (PBS), cells were permeabilized with 1 % Triton X-100 for 10 min. After washing with PBS (three times), cells were blocked with blocking buffer (PBS containing 5 % BSA) for 30 min and then washed with PBS(three times).Next, cells were labeled with either rabbit anti-human TOP1 or rabbit anti-human TOP2A antibodies overnight, and then washed (three times) with PBS. After that, the cells were either labeled with FITC-conjugated secondary antibody or phalloidin-tetramethyl rhodamine for 45 min. DAPI stained nuclei (4–6-diamidino- 2-phenylindole). Fluorescence microscopy was used to image cells. The IHC tests were graded as described(20).

2.12. Xenografted tumor model and HE staining

BALB/c-nu mice were purchased from SPF Biotechnology Co., Ltd (Beijing, China). Stably transfected SJSA-1/R cells that were growing in the logarithmic phase were prepared. Cells were resuspended in PBS at a concentration of 5 × 106 cells/L and then subcutaneously injected into the 5-week-old mice. For in vivo multi-drug therapy, twelve mice were dived into four groups. After the xenografts reached 0.5 cm in diameter, one of the groups was treated saline two of the groups were treated with Cisplatin (1 mg/kg, every 3 days) or Groenlandicine (3 mg/kg, every 3 days) by intraperitoneal injection, the others were treated with Cisplatin (0.5 mg/kg, every 3 days) and Groenlandicine (1.5 mg/kg, every 3 days). Tumor growth was monitored by measurements of the length and width and the tumor volume was calculated using the equation (L×W2)/2. Animals were executed, tumors and kidneys were excised, weighed and paraffin embedded.

Put the slices of kidneys tissue samples into the environmentally friendly dewaxing solution Ⅰ for 20 min − environmentally friendly dewaxing solution Ⅱ for 20 min − anhydrous ethanol Ⅰ for 5 min − anhydrous ethanol Ⅱ for 5 min − 75 % alcohol for 5 min, and then wash them with tap water. The slices are treated with high-definition constant dyeing pretreatment solution for 1 min. Sections were stained with hematoxylin staining solution for 5 min, washed with water, differentiated with differentiation solution, washed with water, returned to blue with blue return solution, and rinsed with running water. The slices were dehydrated in 95 % alcohol for 1 min, and then stained in eosin staining solution for 15 s. The slices were put into anhydrous ethanol I for 2 min − anhydrous ethanol II for 2 min − anhydrous ethanol III for 2 min − n-butanol I for 2 min − n-butanol II for 2 min − dimethyl Ⅰ for 2 min − xylene Ⅱ for 2 min for transparency, and then sealed with neutral gum. Microscopic examination, image acquisition and analysis. All experiments on mice were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Guizhou Medical University, China.

2.13. Statistical analysis

The GraphPad Prism 9 software was used for creating graphs and for statistical analysis. Normally distributed data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (x ± s), and a t-test was performed for the intergroup comparison; Paired sample t-test was used to compare the values of the same individual at different time points. A rank-sum test was used to compare the data that did not follow a normal distribution. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Groenlandicine, identified through the LBVS method, exhibited robust binding activity to TOP1

Groenlandicine, an active constituent of the TCM Coptidis Rhizoma, was identified based on the chemical structure similarity to hydroxycamptothecine using the FP2 algorithm (Fig. 1A). To assess the affinity of groenlandicine for the TOP1 protein target, molecular docking analysis was conducted using AutoDock Vina v1.2.2 software to elucidate binding poses and interactions between the two molecules, and to calculate the binding energies associated with each interaction (Fig. 1B). Results revealed that groenlandicine binds strongly to the active pocket of the TOP1 protein via robust electrostatic interactions, yielding a binding energy of −6.941 kcal/mol, indicative of a notably strong binding activity.

Fig. 1.

The screening process of groenlandicine. (A) Chemical structure of hydroxycamptothecin (left) and groenlandicine (right). (B) A relatively stable binding mode of groenlandicine with TOP1, visualized by AutoDock Vina v1.2.2 software, with a simulated binding energy of –6.941 kcal/mol.

3.2. Groenlandicine promoted apoptosis in OS cells by down-regulating the expression level of TOP1

The fluorescence image showed the transfected OS cells labeled with green fluorescent protein (GFP), and the lentiviral transfection rate was above 80 % (Fig. 2 A). lV-TOP1 denotes the group of OS cells overexpressing TOP1, and sh-TOP1 denotes the down-regulated TOP1 group. RT-PCR and WB analyses showed (Fig. 2C- E), TOP1 in both OS cells was significantly increased in the LV-TOP1 group compared to the empty vector (EV1, EV2) group (***p < 0.001), while TOP1 in the sh-TOP1 group was significantly decreased compared to the EV1, EV2 groups (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01).

Fig. 2.

(A) Fluorescence image after lentiviral transfection (B) RT-PCR analysis to identify the transfection effect of TOP1. (C–E) WB identification of TOP1 transfection effect in SJSA-1 and MG63 cell lines. (F, G) CCK-8 assay was used to measure the effect of groenlandicine (0, 0.05, 0.1, 0.25, 0.5, 1, and 2 μM, 24 h) on the OS cells transfected by lentivirus with over-expression(LV-TOP1) or low-expression(sh-TOP1) of TOP1. n = 3. (H) The effect of groenlandicine on the transfected OS cells showed by FCM. (I, J) Statistical analysis of FCM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001,n.s, differences were not statistically significant.

CCK-8 cytotoxicity assay indicated the effect of groenlandicine on OS cells. The half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of groenlandicine was compared between LV-TOP1, sh-TOP2 groups and their EV1, EV2 control groups under the same conditions in two OS cell lines. The results demonstrated that the up-regulation of TOP1 reduced the sensitivity of SJSA-1 and MG63 to groenlandicine (SJSA-1 LV-TOP1 group: IC50 = 111.3 μM, EV1 group: IC50 = 21.94 μM; MG63 LV-TOP1 group: IC50 = 181.3 μM, EV1 group: IC50 = 57.65 μM). Conversely, down-regulation of TOP1 enhanced the sensitivity of these two types of cells to groenlandicine (SJSA-1 sh-TOP1 group: IC50 = 8.918 μM, EV2 group: IC50 = 37.93 μM; MG63 sh-TOP1 group: IC50 = 11.47 μM, EV2 group: IC50 = 58.03 μM). There was no significant difference between the EV1 and EV2 groups (Fig. 2F, G). These results were re-validated by FCM. The lv-TOP1 group showed alleviative effect on the groendicine-induced apoptosis, whereas, the apoptosis of OS cells was markedly promoted in the sh-TOP1 group (Fig. 2H–J; ****p < 0.0001). These findings suggested that groenlandicine promoted apoptosis by inhibiting the TOP1 protein expression level in OS cells. Another CCK-8 assay indicated the effect of groenlandicine on 293T cells. The IC50 of groenlandicine in 293T was much higher than the IC50 in OS cells (Supplement1). The result showed that groenlandicine exhibited weak cytotoxicity in 293T cells.

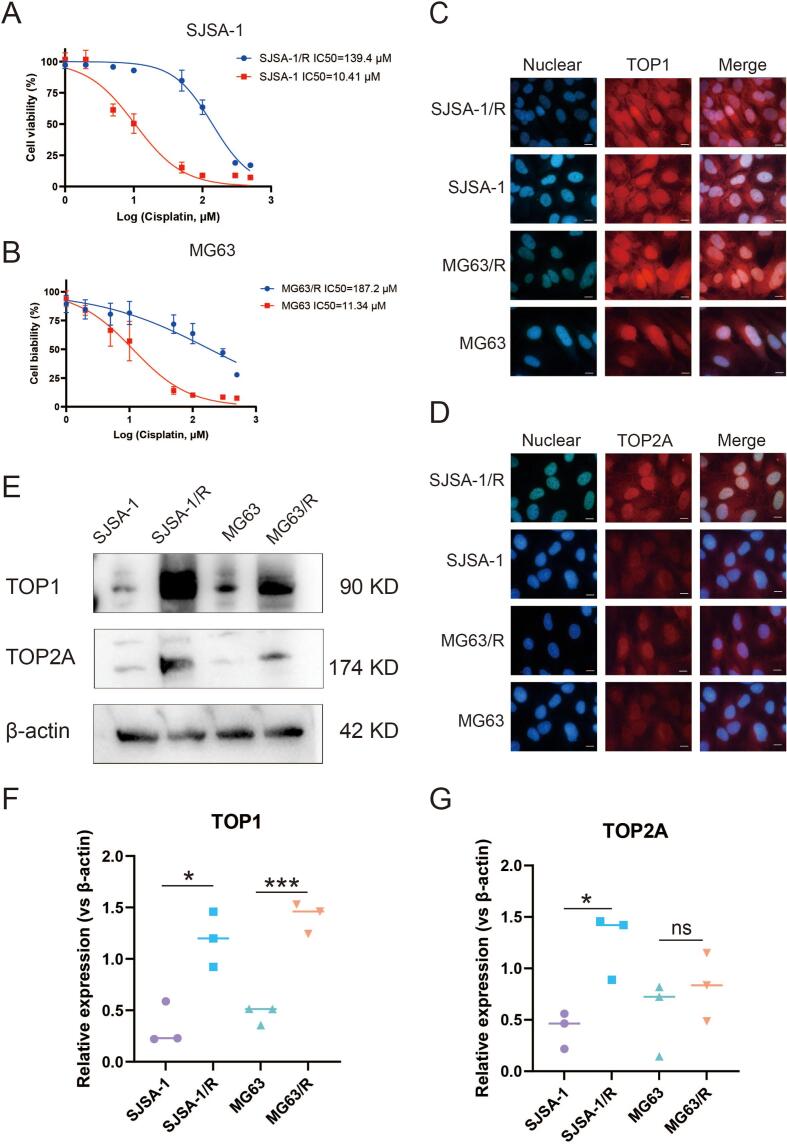

3.3. TOP1 level was increased in cisplatin-resistant OS cells

In the CCK-8 assay, the dose–response curve generated by GraphPad Prism v8 revealed that the IC50 of cisplatin for SJSA-1/R was 139.4 μM, exceeding 10 times that of 10.41 μM observed for SJSA-1. Similarly, the IC50 of cisplatin for MG63/R was 187.2 μM, surpassing 10 times the value of 11.34 μM observed for MG63. These results clearly indicate the development of robust cisplatin resistance in both SJSA-1/R and MG63/R cells (Fig. 3A–B), validating the successful establishment of cisplatin-resistant OS cells.

Fig. 3.

Different levels of TOP1 and TOP2A between cisplatin-sensitive (n = 3) and cisplatin-resistant (n = 3) osteosarcoma (OS) cells detected by immunofluorescence (IF) and western blot (WB). (A–B) CCK-8 assay dose–response curves depicting two cisplatin-resistant OS cell lines that were constructed. (C–D) Red fluorescence labeling positive cells. Cell nuclei labeled with blue fluorescence. Scale = 10 μm. TOP1 and TOP2A are predominantly localized in the nucleus. (E–G) WB demonstrating high levels of TOP1 in cisplatin-resistant cell lines of two OS cell types, whereas TOP2A was not. n = 3, *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Immunofluorescence (IF) assays were employed to observe the distribution of TOP1 and TOP2A proteins within subcellular structures in OS cells. The merged plots illustrated that TOP1 protein was present both inside and outside the nucleus, with a notably higher intranuclear level observed in parental and drug-resistant OS cells of both types (Fig. 3C–D). The nuclear and cytoplasmic proteins of OS cells and cisplatin-resistant OScells were separated, and the expression levels of TOP1 and TOP2 in the nucleus and cytoplasm were detected by Western blot. The results showed that the expression of TOP1 in the nucleus was higher in the drug-resistant group than in the other group, while the expression of TOP1 in the cytoplasm had no significant difference(Supplement 2A-C). In nucleus and cytoplasm, the expression of TOP2 had no significant difference between OS cells and cisplatin-resistant OS cells(Supplement 2D-E). Grayscale analysis of western blot (WB) results further confirmed that TOP1 protein level was significantly elevated in the drug-resistant groups compared to the drug-sensitive groups for both SJSA-1 and MG63 cells, whereas TOP2 level remained unchanged (Fig. 3E–G).

3.4. Groenlandicine reduced the migratory ability of cisplatin-resistant OS cells

In the wound-healing assay, it was noted that after 24 h, the scratch area was significantly reduced in the blank control group, indicating enhanced cell migration. Conversely, the scratch area was slightly reduced in the cisplatin (10 μM) group (p < 0.0001), and moderately reduced in htegrandiseptin (10 μM) groups (p < 0.01), while almost no reduction was observed in the two-drug combination group (5 μM groenlandicine + 5 μM cisplatin) (p < 0.05) (Fig. 4A–B).

Fig. 4.

Effect of groenlandicine and cisplatin on SJSA-1/R and MG63/R. (A–B) Wound healing rate at 24 h representing the level of cell migration. (C–D) CCK-8 assay depicting the effect of groenlandicine and cisplatin on cell viability. (E–H) Flow cytometry (FCM) illustrating the effect of groenlandicine and cisplatin on apoptosis. n = 3, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

3.5. Groenlandicine decreased the cell viability of cisplatin-resistant OS cells

Dose-response curves generated from the CCK-8 assay for SJSA-1/R and MG63/R cells demonstrated that both groenlandicine and cisplatin reduced cisplatin-resistant OS cell viability. Moreover, the combination of these two drugs exhibited a further inhibition of proliferation (Fig. 4C–D).

3.6. Groenlandicine promoted apoptosis in both cisplatin-sensitive and cisplatin-resistant OS cells

The analysis of groenlandicine's effect on apoptosis in cisplatin-resistant OS cells was conducted through flow cytometry (FCM). The results indicated that the apoptosis rate of cisplatin-resistant OS cells was lower compared to cisplatin-sensitive cells (Fig. 4E, G). However, treatment with 10 μM cisplatin (p < 0.0001) or 10 μM groenlandicine (p < 0.0001) resulted in an increase in the apoptosis rate of SJSA-1/R and MG63/R cells. Notably, a significant enhancement in apoptosis was observed with the combined treatment of 5 μM cisplatin and 5 μM groenlandicine (p < 0.0001) (Fig. 4F, H). These findings underscored the role of groenlandicine in promoting apoptosis in both cisplatin-sensitive and cisplatin-resistant OS cells.

3.7. Groenlandicine inhibited the proliferation of cisplatin-resistant OS cells

The EdU assay was employed to assess alterations in cell proliferation among cisplatin-resistant OS cells treated with groenlandicine. Orange fluorescence denoted proliferating cells, while blue fluorescence represented all cells. The results revealed a reduction in relative cell viability rates of SJSA-1/R and MG63/R cells following treatment with 10 μM cisplatin (p < 0.01) or 10 μM groenlandicine (p < 0.01). Notably, a significant decrease in cell viability was observed upon treatment with 5 μM cisplatin combined with 5 μM groenlandicine (p < 0.01) (Fig. 5A–C). These findings indicate that groenlandicine effectively inhibits the proliferation of cisplatin-resistant OS cells, enhancing the inhibition in combination with cisplatin.

Fig. 5.

Effect of groenlandicine and cisplatin on proliferation and mRNA levels in osteosarcoma (OS) cells. (A–C) Fluorescence images and statistical charts of EdU demonstrating the effect of groenlandicine and cisplatin on proliferation of SJSA-1 and SJSA-1/R. Scale = 100 μm. (D–E) Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) validation of mRNA levels of TOP1 and TOP2A in different groups. n = 3, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

3.8. Groenlandicine combined with cisplatin observably decreased the level of TOP1 in cisplatin-resistant OS cells

Following treatment with 10 μM groenlandicine or 10 μM cisplatin, or a combination of 5 μM groenlandicine and 5 μM cisplatin for 24h, the levels of TOP1 and TOP2A in two types of cisplatin-resistant OS cells were evaluated using reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction. The results indicated that groenlandicine effectively reduced the level of TOP1 in SJSA-1/R (p < 0.01) and MG63/R (p < 0.0001) (Fig. 5D–E), while TOP2 level remained unchanged in SJSA-1/R. The two-drugs group showed the lowest expression level of TOP1. The levels of TOP1 and TOP2A in two types of cisplatin-resistant OS cells were evaluated using WB. The result showed that groenlandicine decreased the level of TOP1 in SJSA-1/R (p < 0.001) and MG63/R (p < 0.001) (Fig. 6B–C), while TOP2 level remained unchanged in MG63/R (Fig. 6C).

Fig. 6.

Effect of groenlandicine and cisplatin on protein levels in OS cells. (A) Western blot (WB) analysis illustrating the effect of groenlandicine and cisplatin on the levels of TOP1, TOP2, Bcl-2, BAX, Caspase-9, and Caspase-3 in SJSA/R and MG63/R. (B–C) Quantification of protein levels through grayscale scanning. n = 3, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

3.9. Groenlandicine combined with cisplatin strongly activated BAX, cleaved-Caspase-3, and cleaved-Caspase-9, while inhibiting Bcl2 in cisplatin-resistant OS cells

In the various drug treatment groups of SJSA-1/R and MG63/R cells, the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl2 was significantly inhibited in the 10 μM groenlandicine group, with even more pronounced inhibition observed after treatment with the combination of 5 μM groenlandicine and 5 μM cisplatin (p < 0.0001) (Fig. 6A–C). The apoptotic protein BAX was significantly activated by 10 μM groenlandicine treatment, with the highest activation observed in the two-drug combination group (p < 0.0001). Additionally, cleaved-Caspase-9 and cleaved-Caspase-3, which were not significantly elevated in the single-drug groups, exhibited significant elevation in the two-drug combination group (p < 0.05), indicating activation of apoptotic protein activity for both cleaved-Caspase-9 and cleaved-Caspase-3 (Fig. 6B–C).

3.10. SC79 blocked the groenlandicine-induced expression reduction of Bcl2 and groenlandicine-induced activation of BAX, cleaved-Caspase-3, and cleaved-Caspase-9 in cisplatin-resistant OS cells

To examine whether groenlandicine enhanced the sensitivity of drug-resistant OS cells to cisplatin via the BAX/Bcl-2/Caspase-9/Caspase-3 pathway, SJSA-1/R and MG63/R cells were treated with 10 μM groenlandicine for 24 h in the presence or absence of 10 μM SC79, an AKT (also known as protein kinase B or PKB) activator which blocks BAX/Bcl-2/Caspase-9/Caspase-3. Western blot analysis showed that groenlandicine was no longer able to decreased the expression of Bcl2 in the presence of SC79, and that groenlandicine could no longer activated BAX, cleaved-Caspase3, and cleaved-Caspase9 in the presence of SC79 in two types of cisplatin-resistant OS cells (Figure 7A–C). These results suggested that SC79 blocked the groenlandicine-induced reduction of Bcl2 and groenlandicine-induced activation of BAX, cleaved-Caspase-3, and cleaved-Caspase-9 in cisplatin-resistant OS cells.

Fig. 7.

SC79 blocked the groenlandicine-induced expression reduction of Bcl2 and groenlandicine-induced activation of BAX, cleaved-Caspase-3, and cleaved-Caspase-9 in cisplatin-resistant OS cells. n = 3, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, n.s, no significance.

3.11. SC79 showed no effects on the groenlandicine-induced down-regulation of TOP1

WB essay exhibited that the TOP1 level of blank group remained unchanged with the treatment of SC79 in SJSA-1/R and MG63/R. Additionally, TOP1 level was significantly reduced in groenlandicine group, remaining unchanged with the combination of SC79(Figure 7B–C). The results above indicated that SC79 had no effects on the groenlandicine-induced down-regulation of TOP1.

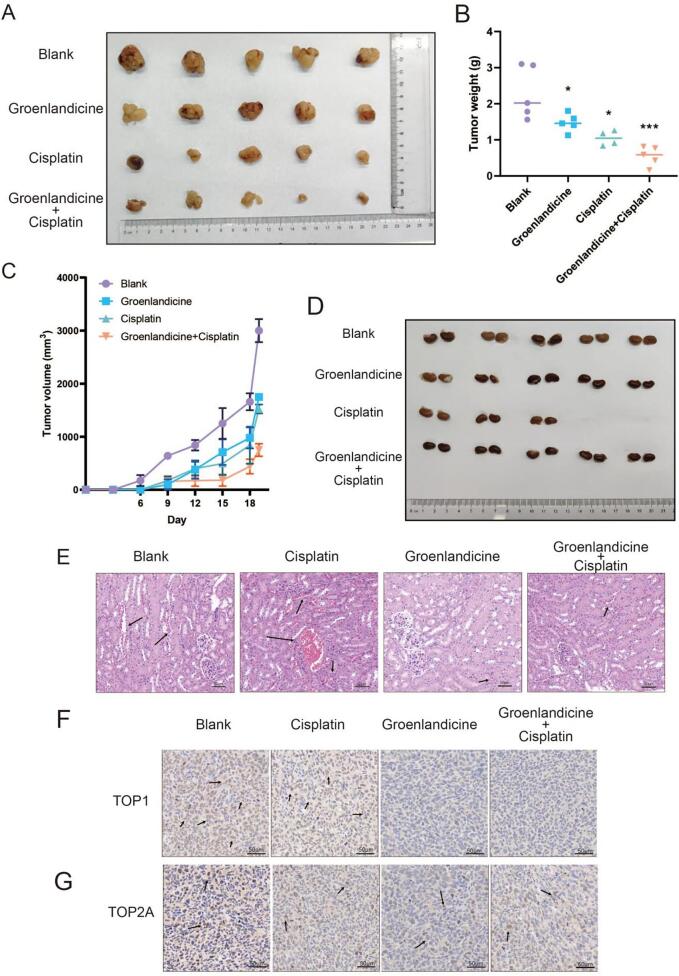

3.12. Groenlandicine effectively suppressed OS cell growth, while down-regulating the level of TOP1, without obvious renal toxicity, in an animal model

The tumour volume in the group treated with 1.5 mg/kg groenlandicine combined with 0.5 mg/kg cisplatin remained consistently smaller throughout the duration of the experiment compared to all other treatment groups, which included the 3 mg/kg groenlandicine group and the 1 mg/kg cisplatin group (Fig. 8A, B). Notably, in the combination treatment group, the weight of tumors extracted from nude mice after 18 days was the lowest (Fig. 8C). Histological examination via hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining revealed connective tissue between urinary tubules, identified as renal interstitium, with multiple interstitial vascular bruises and a small number of tubular epithelial cells displaying hydropic degeneration in the cisplatin-treated group. However, renal damage appeared reduced when groenlandicine was administered in combination with cisplatin. Moreover, no obvious histological abnormalities were observed in the groenlandicine-treated group (Fig. 8D–E). Immunohistochemical staining of tumor specimens verified that groenlandicine led to the down-regulation of the TOP1 level. Additionally, the level of TOP1 was further reduced when combined with cisplatin (Fig. 8F), whereas TOP2 level remained unchanged (Fig. 8G). These findings collectively demonstrate that groenlandicine effectively suppresses OS cell growth, down-regulates TOP1 level in vivo, and mitigates the risk of renal toxicity.

Fig. 8.

Effect of groenlandicine and cisplatin on osteosarcoma (OS) cell growth, TOP1 levels, and renal protection in vivo. (A–D) Animal experiments validating the effect of groenlandicine and cisplatin on OS cells. (D–E) Morphological alterations of renal tissue demonstrated by hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining in different groups. Scale = 50 μm. (F) Immunohistochemical staining of tumor specimens confirming the effect of groenlandicine and cisplatin on the levels of TOP1 and TOP2. Scale = 50 μm. n = 5, *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001.

4. Discussion

Cisplatin exerts a direct toxic effect on tumor cells and plays an important role in tumor growth, invasion, and metastasis [18]. Consequently, it is extensively utilized as a first-line chemotherapeutic agent in treating OS [19]. However, the occurrence of cisplatin-resistant events is frequent during OS therapy, leading to suboptimal therapeutic outcomes [20]. Finding effective approaches to solve the problem of OS cells resistance to cisplatin remains a formidable challenge [21]. The inhibition of apoptosis is one mechanism through which OS develops cisplatin resistance [22], [23]. In this study, we investigated the impact of groenlandicine on cisplatin-resistant OS cells. We have demonstrated, for the first time, that groenlandicine are perfectly capable of killing OS cells, and that groenlandicien enhances the sensitivity of cisplatin-resistant OS cells to cisplatin and promotes apoptosis in cisplatin-resistant OS cells by activating Caspase-3, Caspase-9, BAX, and inhibiting the Bcl2 pathway. Moreover, groenlandicine down-regulates the level of TOP1 in OS cells, which is associated with the antineoplastic activity of groenlandicine.

In recent years, numerous TOP inhibitors have been utilized in the treatment of OS [24], [25], [26], [27]. For instance, the synthetic TOP2 inhibitor ICRF-193 has been shown to impede the binding of the transcription factor NF-KappaB to target gene sequences, thereby suppressing the transcription of downstream genes and mitigating the proliferation and metastasis of OS [28]. Similarly, the TOP1 inhibitor irinotecan has been shown to enhance the sensitivity of OS cells to cisplatin by inhibiting TOP1 activity [29]. In our earlier investigations, we discovered that hydroxycamptothecin (a TOP1 inhibitor), derived from the seeds of the Chinese medicinal plant Hibiscus sabdariffa, synergizes with cisplatin to inhibit OS cell proliferation and induce apoptosis. In this study, we screened one of Coptidis rhizoma extract, groenlandicine [30], using the LBVS method [31]. Groenlandicine shares a similar chemical structure with hydroxycamptothecin. The molecular docking analysis, a computational structure-based method widely used in drug discovery [32], predicted a notably strong binding activity between TOP1 and groendicine. Coptidis rhizoma extract has demonstrated anti-bacterial, anti-fungal, anti-viral, anti-amoebic, anti-inflammatory, anti-diarrheal, cardiovascular, anti-pyretic, hypoglycemic, and antioxidant effects [33], [34]. However, groendicine has been little investigated, and its anti-tumor effect has not been reported in the current literature. Our experiments on OS cells revealed that groenlandicine exhibits potent anti-tumor effects by suppressing OS cell migration and proliferation while promoting apoptosis. Upon treatment with groenlandicine (10 μM), we noted a reduction in TOP1 protein level in two types of OS cells. the effect of groenlandicine on the over-expressed TOP1 and down-regulated TOP1 OS cells transfected by lentivirus. After treating the OS cells transfected by lentivirus over-expressing or low-expressing TOP1 with groenlandicine, the result proved that groenlandicine promoted apoptosis in OS cells by down-regulating the expression level of TOP1. Additionally, the down-regulation of TOP1 and tumor growth-suppression effect induced by groenlandicine was validated through animal experiments. By developing a cisplatin-resistant strain of OS, we observed an elevation in TOP1 protein level in tumor cells post-drug resistance development. Hence, we deduce that groenlandicine down-regulates the level of TOP1 in OS cells, which led to the anti-OS activity of groenlandicine. Furthermore, TOP1 might play a role in the mechanism by which OS cells develop cisplatin resistance.

Blocking cisplatin-induced apoptosis could develop cisplatin resistance. In our study, we observed a significant enhancement in apoptosis with the combined treatment of 5 μM cisplatin and 5 μM groenlandicine compared with the single-drug (10 μM) group through FCM. In other words, the two-drugs group obtained better treatment effect with half of the concentration of single-drug group. These results critically proved that groendicine enhanced the cisplatin-sensitivity in cisplatin-resistant OS cells through promoting apoptosis.

BCL-2 is an essential protein involved in apoptosis regulation, often found to be overexpressed in various human tumor tissues and cells, and closely linked to tumorigenesis, progression, and drug resistance [35], [36]. Cho et al. revealed that upregulation of Bcl-2 contributed to the development of cisplatin-resistance in bladder cancer [37]. Michaud et al. found that high endogenous Bcl-2 expression was related to increased cisplatin resistance, and exogenetic overexpression of Bcl-2 promoted cisplatin resistance in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck [38]. Multiple pieces of evidence have indicated that the aberrantly activated Bcl2/BAX signaling pathway is intimately associated with cisplatin resistance development in tumor cells. We also observed no significant change in BAX level when treated with cisplatin (10 μM) alone, but it was significantly upregulated following treatment with groenlandicine (5 μM) in combination with cisplatin (5 μM). Furthermore, the combined treatment significantly promoted cleaved-Caspase-9 and Caspase-3 levels while significantly suppressing Bcl2 levels.

In addition, groenlandicine could no longer down-regulate Bcl2 or activate BAX, cleaved-Caspase-3, and cleaved-Caspase-9 after their upstream path was blocked by SC79 in cisplatin-resistant OS cells, while SC79 showed no effects on the groenlandicine-induced down-regulation of TOP1. The results verified that groenlandicine enchancing cisplatin sensibility in OS cells by regulating the Bcl2/BAX/Caspase-3/Caspase-9 pathway was independent of its down-regulation of TOP1.Therefore, we conclude that groenlandicine enhances the sensitivity of drug-resistant cells to cisplatin and induces apoptosis in cisplatin-resistant OS cells by activating BAX, Caspase-3, and Caspase-9, while inhibiting Bcl2.

In conclusion, our study marks the first demonstration of groenlandicine's ability to overcome cisplatin resistance in OS by modulating the Bcl2/BAX/Caspase-3/Caspase-9 pathway. Groenlandicine exhibits remarkable anti-OS effects with minimal nephrotoxicity. Therefore, groenlandicine holds promise as a potential agent for reversing cisplatin resistance in OS treatment.

Funding

The present study was supported by Runsang Pan [(2020) Zhuweijiankeji; grant. no. 018].

6. Ethics approval statement

All experiments on mice were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Guizhou Medical University, China.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Zihao Zhao: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Software, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Qihong Wu: Resources, Project administration, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Yangyang Xu: Resources, Project administration, Methodology. Yuhuan Qin: Resources. Runsang Pan: Funding acquisition. Qingqi Meng: Visualization, Validation, Supervision. Siming Li: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Supervision.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

The authors are so appreciated for the supports of Guizhou Medical University and Guangzhou Red Cross Hospital.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbo.2024.100631.

Contributor Information

Qingqi Meng, Email: mengqingqi@jnu.edu.cn.

Siming Li, Email: drsmli@163.com.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

Supplementary Fig. 1.

Supplementary Fig. 2.

References

- 1.Li S., Zhang H., Liu J., Shang G. Targeted therapy for osteosarcoma: a review. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2023;149(9):6785–6797. doi: 10.1007/s00432-023-04614-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Panez-Toro I., Muñoz-García J., Vargas-Franco J.W., Renodon-Cornière A., Heymann M.F., Lézot F., Heymann D. Advances in osteosarcoma. Curr. Osteoporos. Rep. 2023;21(4):330–343. doi: 10.1007/s11914-023-00803-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Twenhafel L., Moreno D., Punt T., Kinney M., Ryznar R. Epigenetic changes associated with osteosarcoma: a comprehensive review. Cells. 2023;12(12) doi: 10.3390/cells12121595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beird H.C., Bielack S.S., Flanagan A.M., Gill J., Heymann D., Janeway K.A., Livingston J.A., Roberts R.D., Strauss S.J., Gorlick R. Osteosarcoma. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 2022;8(1):77. doi: 10.1038/s41572-022-00409-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benjamin R.S. Adjuvant and neoadjuvant chemotherapy for osteosarcoma: a historical perspective. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2020;1257:1–10. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-43032-0_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eaton B.R., Schwarz R., Vatner R., Yeh B., Claude L., Indelicato D.J., Laack N. Osteosarcoma. Pediatr. Blood Cancer. 2021;68(Suppl 2):e28352. doi: 10.1002/pbc.28352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hanke A., Ziraldo R., Levene S.D. DNA-topology simplification by topoisomerases. Molecules. 2021;26(11) doi: 10.3390/molecules26113375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buzun K., Bielawska A., Bielawski K., Gornowicz A. DNA topoisomerases as molecular targets for anticancer drugs. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2020;35(1):1781–1799. doi: 10.1080/14756366.2020.1821676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nguyen A., Lasthaus C., Guerin E., Marcellin L., Pencreach E., Gaub M.P., Guenot D., Entz-Werle N. Role of topoisomerases in pediatric high grade osteosarcomas: TOP2A gene is one of the unique molecular biomarkers of chemoresponse. Cancers (basel) 2013;5(2):662–675. doi: 10.3390/cancers5020662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen Y., Wang Z., Wang X., Su M., Xu F., Yang L., Jia L., Zhang Z. Advances in antitumor nano-drug delivery systems of 10-hydroxycamptothecin. Int. J. Nanomed. 2022;17:4227–4259. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S377149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dasari S., Njiki S., Mbemi A., Yedjou C.G., Tchounwou P.B. Pharmacological effects of cisplatin combination with natural products in cancer chemotherapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022;23(3) doi: 10.3390/ijms23031532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ghosh S. Cisplatin: The first metal based anticancer drug. Bioorg. Chem. 2019;88 doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2019.102925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Romani A.M.P. Cisplatin in cancer treatment. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2022;206 doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2022.115323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sadiq Z., Varghese E., Büsselberg D. Cisplatin's dual-effect on the circadian clock triggers proliferation and apoptosis. Neurobiol. Sleep Circad. Rhythms. 2020;9 doi: 10.1016/j.nbscr.2020.100054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mirzaei S., Gholami M.H., Hashemi F., Zabolian A., Hushmandi K., Rahmanian V., Entezari M., Girish Y.R., Sharath Kumar K.S., Aref A.R., Makvandi P., Ashrafizadeh M., Zarrabi A., Khan H. Employing siRNA tool and its delivery platforms in suppressing cisplatin resistance: Approaching to a new era of cancer chemotherapy. Life Sci. 2021;277 doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2021.119430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Qi Y., Yang W., Liu S., Han F., Wang H., Zhao Y., Zhou Y., Zhou D. Cisplatin loaded multiwalled carbon nanotubes reverse drug resistance in NSCLC by inhibiting EMT. Cancer Cell Int. 2021;21(1):74. doi: 10.1186/s12935-021-01771-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alam M., Mishra R. Bcl-xL expression and regulation in the progression, recurrence, and cisplatin resistance of oral cancer. Life Sci. 2021;280 doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2021.119705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bian J., Liu Y., Zhao X., Meng C., Zhang Y., Duan Y., Wang G. Research progress in the mechanism and treatment of osteosarcoma. Chin. Med. J. (Engl) 2023;136(20):2412–2420. doi: 10.1097/CM9.0000000000002800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Du X., Wei H., Zhang B., Wang B., Li Z., Pang L.K., Zhao R., Yao W. Molecular mechanisms of osteosarcoma metastasis and possible treatment opportunities. Front. Oncol. 2023;13:1117867. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2023.1117867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moghbeli M. MicroRNAs as the pivotal regulators of cisplatin resistance in osteosarcoma. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2023;249 doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2023.154743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ferretti V.A., León I.E. Long non-coding RNAs in cisplatin resistance in osteosarcoma. Curr. Treat. Options Oncol. 2021;22(5):41. doi: 10.1007/s11864-021-00839-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hattinger C.M., Patrizio M.P., Fantoni L., Casotti C., Riganti C., Serra M. Drug resistance in osteosarcoma: emerging biomarkers, therapeutic targets and treatment strategies. Cancers (Basel) 2021;13(12) doi: 10.3390/cancers13122878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garcia-Ortega D.Y., Cabrera-Nieto S.A., Caro-Sánchez H.S., Cruz-Ramos M. An overview of resistance to chemotherapy in osteosarcoma and future perspectives. Cancer Drug Resist. 2022;5(3):762–793. doi: 10.20517/cdr.2022.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Higuchi T., Miyake K., Oshiro H., Sugisawa N., Yamamoto N., Hayashi K., Kimura H., Miwa S., Igarashi K., Chawla S.P., Bouvet M., Singh S.R., Tsuchiya H., Hoffman R.M. Trabectedin and irinotecan combination regresses a cisplatinum-resistant osteosarcoma in a patient-derived orthotopic xenograft nude-mouse model. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2019;513(2):326–331. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2019.03.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li Y., Qu J., Zhang P., Zhang Z. Reduction-responsive sulfur dioxide polymer prodrug nanoparticles loaded with irinotecan for combination osteosarcoma therapy. Nanotechnology. 2020;31(45) doi: 10.1088/1361-6528/aba783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meazza C., Asaftei S.D. State-of-the-art, approved therapeutics for the pharmacological management of osteosarcoma. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2021;22(15):1995–2006. doi: 10.1080/14656566.2021.1936499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Usman R.M., Razzaq F., Akbar A., Farooqui A.A., Iftikhar A., Latif A., Hassan H., Zhao J., Carew J.S., Nawrocki S.T., Anwer F. Role and mechanism of autophagy-regulating factors in tumorigenesis and drug resistance. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021;17(3):193–208. doi: 10.1111/ajco.13449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Campbell K.J., O'Shea J.M., Perkins N.D. Differential regulation of NF-kappaB activation and function by topoisomerase II inhibitors. BMC Cancer. 2006;6:101. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-6-101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Büyükkapu Bay S., Kebudi R., Görgün O., Zülfikar B., Darendeliler E., Çakır F.B. Vincristine, irinotecan, and temozolomide treatment for refractory/relapsed pediatric solid tumors: A single center experience. J. Oncol. Pharm. Pract. 2019;25(6):1343–1348. doi: 10.1177/1078155218790798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tan J.L., Xu Y.L., Fei Y.Q., Zheng G.H., Ding X.P. Simultaneous screening, identification, quantitation, and activity evaluation of six acetylcholinesterase (AChE) inhibitors in Coptidis Rhizoma by online UPLC-DAD coupled with AChE biochemical detection. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2022;219 doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2022.114897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oselusi S.O., Dube P., Odugbemi A.I., Akinyede K.A., Ilori T.L., Egieyeh E., Sibuyi N.R., Meyer M., Madiehe A.M., Wyckoff G.J., Egieyeh S.A. The role and potential of computer-aided drug discovery strategies in the discovery of novel antimicrobials. Comput. Biol. Med. 2024;169 doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2024.107927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pinzi L., Rastelli G. Molecular Docking: Shifting Paradigms in Drug Discovery. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019;20(18) doi: 10.3390/ijms20184331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang J., Wang L., Lou G.H., Zeng H.R., Hu J., Huang Q.W., Peng W., Yang X.B. Coptidis Rhizoma: a comprehensive review of its traditional uses, botany, phytochemistry, pharmacology and toxicology. Pharm. Biol. 2019;57(1):193–225. doi: 10.1080/13880209.2019.1577466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Han Y., Xiang Y., Shi Y., Tang X., Pan L., Gao J., Bi R., Lai X. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacological activities of berberine in diabetes mellitus treatment. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2021;2021:9987097. doi: 10.1155/2021/9987097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mohammad R.M., Muqbil I., Lowe L., Yedjou C., Hsu H.Y., Lin L.T., Siegelin M.D., Fimognari C., Kumar N.B., Dou Q.P., Yang H., Samadi A.K., Russo G.L., Spagnuolo C., Ray S.K., Chakrabarti M., Morre J.D., Coley H.M., Honoki K., Fujii H., Georgakilas A.G., Amedei A., Niccolai E., Amin A., Ashraf S.S., Helferich W.G., Yang X., Boosani C.S., Guha G., Bhakta D., Ciriolo M.R., Aquilano K., Chen S., Mohammed S.I., Keith W.N., Bilsland A., Halicka D., Nowsheen S., Azmi A.S. Broad targeting of resistance to apoptosis in cancer. Semin Cancer Biol. 2015;35 doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2015.03.001. S78-s103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pistritto G., Trisciuoglio D., Ceci C., Garufi A., D'Orazi G. Apoptosis as anticancer mechanism: function and dysfunction of its modulators and targeted therapeutic strategies. Aging (Albany NY) 2016;8(4):603–619. doi: 10.18632/aging.100934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cho H.J., Kim J.K., Kim K.D., Yoon H.K., Cho M.Y., Park Y.P., Jeon J.H., Lee E.S., Byun S.S., Lim H.M., Song E.Y., Lim J.S., Yoon D.Y., Lee H.G., Choe Y.K. Upregulation of Bcl-2 is associated with cisplatin-resistance via inhibition of Bax translocation in human bladder cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 2006;237(1):56–66. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2005.05.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Michaud W.A., Nichols A.C., Mroz E.A., Faquin W.C., Clark J.R., Begum S., Westra W.H., Wada H., Busse P.M., Ellisen L.W., Rocco J.W. Bcl-2 blocks cisplatin-induced apoptosis and predicts poor outcome following chemoradiation treatment in advanced oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2009;15(5):1645–1654. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]