Abstract

The frequent relocation of professional football clubs is a phenomenon unique to Chinese professional football, which has long attracted extensive attention from policy makers and scholars. Using data on spatial geography and competitive levels between 1994 and 2021, this research explores the spatial distribution and migration characteristics of top professional football clubs in China, in which GIS spatial analysis and exploratory spatial data analysis (ESDA) were used to analyze the influence of the regional economic, demographic, and developmental levels of the sports industry and institutional supply on the distribution and migration of clubs. The results indicate the following: (1) the overall spatial distribution of professional football clubs in China shows the pattern of “more in the east and less in the west”, and the degree of club concentration gradually increases over time; (2) the migration frequency and downward migration of professional football clubs in China gradually decreased during the period of C League and CSL, and the overall situation tends to be stable; and (3) in the early stages of development of professional leagues, changes in ownership and local policy supply had a significant impact on the distribution and migration of professional clubs. As time progressed, the top-down design of institutional arrangements changed, and the regional economic, demographic, and developmental levels of the sports industry gradually became the essential determinants of the distribution and migration of professional football clubs. In the future, Chinese professional football clubs should focus on rationalizing the advantages of the regional economy, demography, and sports industry as well as reducing their reliance on short-term resources, such as corporate investment and policy benefits.

Subject terms: Environmental sciences, Environmental social sciences

Introduction

Professional sports clubs are an essential part of the modern sports industry. Their distribution and relocation involves club renaming1, the construction of an urban sports culture2, fan emotions and identification3, and the sustainable development of the professional sports industry4,5. For a long time, these aspects have been the focus of the attention of sports event managers and sports economists. In China, since the inception of the professional football league in 1994, a mere four newly established clubs have managed to avoid relocation. Conversely, 19 top-tier league clubs have experienced relocation and, ultimately, dissolution. Researchers in China have conducted various explorations around the country’s distribution and relocation of football clubs. Zhimei6 used the theory of spatial diffusion to study the diffusion of professional football clubs in different spatial ranges in China and summarized the distribution law. Bailin7 pointed out that the distribution changes in professional football clubs follow economic activity characteristics and are influenced by regional resource endowment differences, requiring market foundation and cultural atmosphere. Kunlun8 stated that the dynamics and mechanism of the spatial and temporal evolution of professional football clubs are the result of the joint action of social, economic, political, cultural, and other factors, while Bingshu et al.9 noted that the territorial layout of professional football clubs in China lacks planning and guidance, and rooting in the home field is conducive to club construction and regional development.

In terms of policy, the Central Leading Group for Comprehensively Deepening Reform passed the Overall Plan for the Reform and Development of Chinese Football, proposing that enterprises and cities should provide stable support for clubs and promote the medium- and long-term development of professional football. In 2016, the Chinese Football Association (CFA) Professional Football Club Transfer Regulations was issued, which once again restricts the transfer of clubs from one place to another and strictly prohibits inter-provincial transfers of clubs, and since then the long-distance relocation of professional football clubs has been improved to a certain extent. The distribution and relocation of professional football clubs affects the consolidation and cultivation of club fans, which is related to the sustainable development of professional football clubs. In 2020, the CFA continued to promulgate Several Measures on Further Promoting the Reform and Development of Football, emphasizing the cultivation of a stable club fan base and the promotion of the healthy development of professional leagues. And in 2024, the CFA issued the Provisions on the Change of Registered Member Associations and Equity Transfer of Professional Men’s Football Clubs of the Chinese Football Association (Trial Implementation) specifically around the phenomenon of relocation of professional football clubs, marking the fact that professional clubs can be transferred to other places under certain conditions. The introduction of a series of reform policies has provided policy support for this study, and is also conducive to the standardization and advancement of professional football and even sports in China.

Based on the above research and policies, this study analyzes the spatial and temporal distribution and migration characteristics of Chinese professional football clubs from 1994 to 2021 based on the spatial geographic data of Chinese professional football clubs since 1994. It adopts the knowledge and methods of cross-fertilization of sports studies with human geography, spatial economics and other disciplines to explore the relationship between these characteristics and factors such as regional economy, population, level of development of sports industry and the changes of club investment enterprises. The aim is to provide theoretical support for the scientific layout of Chinese professional football leagues and the sustainable development of the football business and industry.

Data sources and research methods

Indicator selection

For the research on regional heterogeneity, the research on industry and environment has developed perspectives such as economic, demographic, market, and regional relations10, of which economic and demographic are the two most important research categories, the first category defines regional heterogeneity from the perspective of the economic environment, and the second category fully considers the differences that exist in the region from the human environment11. As early as 1984, Bruce Walker12 analyzed the relationship between city size effects and league teams. Since population has an effect on league standings as well as attendance, teams in larger cities are more likely to be successful. Baade13, in his study, identified professional sports as a catalyst for metropolitan economic development. Cities have to provide incredible financial support to attract and retain a team and try to rationalize that support, but the increased revenue and job creation that professional sports provide to the city does not seem to rationalize those financial expenditures, which is extremely similar to the problems that Chinese professional football has encountered in its development.

In fact, the development of professional clubs is affected by various factors, including both their own management and the role of the external environment, and the perspective of regional differences is mainly to study the impact of the external environment on football clubs. Liping14 pointed out that economic factors are the most important factors affecting the development of professional clubs in China. With the development of China’s economy and the transformation of social structure, the level of urbanization is getting higher and higher, the consumption structure of the population has changed, the enhancement of cultural literacy and ideological concepts has made the situation improve, and the population has also become an important indicator for the development of professional clubs. The football industry as a tertiary industry, professional football clubs are its specific form of operation. The agglomeration effect of China’s modern service industry is positively correlated with the city size, and the non-productive modern service industry is greatly influenced by the city size15. The city size is divided according to the number of urban population, for example: in China urban areas with a permanent population of more than 5 million and less than 10 million are regarded as megacities.

Heng16 pointed out in his study of the relationship between regional economy and the development of professional clubs that the economy is the basis for the survival and development of sports, and the level of development of professional sports is greatly related to the supply and demand of the market, and the article examined the relationship between the number of regional clubs and the per capita GDP. With full consideration of accessibility, representativeness and scientificity, it considers the temporal and spatial evolution of professional football clubs in China from both economic and demographic perspectives, and the main indicators selected are the per capita GDP, the number of resident population and the gross domestic product of tertiary industry in each province. Also, since professional clubs, as a new type of tertiary industry, have a distinctly different business model from traditional enterprises, and athletes are their valuable assets, the level of competition (points) is taken as their most important output, reflecting the overall situation of football clubs in a particular province or city.

Study area and data sources

Referring to the sample selection in similar studies by Hengran et al.17, this study limited the geographical area of professional football clubs to 31 provinces, municipalities, and autonomous regions in China, excluding the three regions of Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan. The primary data of professional football clubs used in the study included three categories: (1) Participating data of professional football clubs. This includes the number of times, tournament points, and championships of all clubs in the League A and the Chinese Super League between 1994 and 2021. The data mainly came from the official website of the Chinese Super League (https://www.csl-china.com/, https://www.thecfa.cn/zxb/), NetEase Sports (https://sports.163.com/), and the official websites of clubs (https://www.lnts.com.cn/, http://www.fcguoan.com/, https://www.shenhuafc.com.cn/, etc.). (2) Geographical data of professional football clubs. It was mainly obtained from the National Center for Fundamental Geographic Information, (https://www.ngcc.cn/) and the Gaode Open Platform (https://lbs.amap.com/tools/picker), which obtained a 1:4 million basic geographic data map of China and the geographical coordinates of clubs at different times, final processing and rendering is done by ArcGIS 10.2 (https://www.arcgis.com/). (3) Data on population, economy, and sports industry in professional football clubs’ territories. It comes from the “China Statistical Yearbook (https://www.stats.gov.cn/)” of 1994, 2004, and 2020, which were used to analyze the impact of population, economy, and other factors on the distribution and migration of clubs.

Methods

GIS spatial analysis method

Referring to Li et al.18, this study used the GIS spatial analysis method to calculate the area’s average center and geographic concentration index, reflecting the clubs’ spatial distribution status and agglomeration degree. The average center was obtained by the weighted averaging of the geographical coordinates, and the concentration index was calculated in the grid unit of 10 km × 10 km by using Arcgis10.2 to draw the distribution point fishnet diagram and then using the following formula:

| 1 |

According to Li et al., we used Formula (1) to calculate the geographical concentration index. In Formula (1), Xi represents the number of clubs in the ith unit and T represents the total number of professional football clubs over the years. G represents the geographical concentration index, with values ranging from 0 to 100, and a higher value indicating a higher degree of agglomeration.

Exploratory spatial data analysis

Exploratory spatial data analysis (ESDA) is a method for studying spatial de-pendence and heterogeneity. In order to analyze the distribution and correlation of the competitive level of Chinese professional football clubs and their influencing factors in geographical space, an ESDA analysis was conducted using GeoDa software, and the global Moran’s index of each element was calculated to describe the overall correlation degree using the formula from Stevens19:

| 2 |

where I represents Moran’s I, wij represents spatial weight, and n represents the total number of study units in the study area. zi (j) represents the difference between the attribute value on each spatial unit and the average value. S2 represents the variance of the number of clubs in the study area among n study units. The distribution of the global Moran’s index is between − 1 and 1. I < 0 indicates a negative correlation, where attributes with significant differences are clustered together, and I > 0 indicates a positive correlation, which means that similar attributes are clustered20. I = 0 indicates that the overall space is unrelated, but local correlations may still exist.

Spatial–temporal distribution characteristics of Chinese professional football clubs

Overall characteristics of the spatio-temporal distribution of clubs

Using the Gaode Open Platform to ingest the relevant coordinates and obtain the geographic data of administrative districts from the database of the National Center for Fundamental Geographic Information, the relevant content is from the open platform, the base map has not been modified, and specific websites have been provided in the “Data sources and research methods” section. And this study referred to the “two horizontal and three vertical” strategic pattern provided in the “14th Five-Year Plan for National Economic and Social Development and the Long-Term Goals for 2035” (hereinafter referred to as the “14th Five-Year Plan”). Because China has formed a strategic pattern of “Two Horizontal and Three Vertical”, and the “Two Horizontals” are along the land bridge corridor and the Yangtze River corridor, while the “Three Verticals” are along the eastern seaboard, the Beijing-Harbin-Guangzhou and the Baokun corridors. The formation of this pattern is conducive to narrowing the regional gap, complementary advantages to promote the high-quality development of the economy, in order to achieve regional ecological protection, transformation and upgrading of enterprises and other parties to coordinate. The study of the overall situation of the distribution of professional football clubs in China on this spatial pattern better reflects the distribution of professional football clubs in urban agglomerations and urban belts than a generalized division.

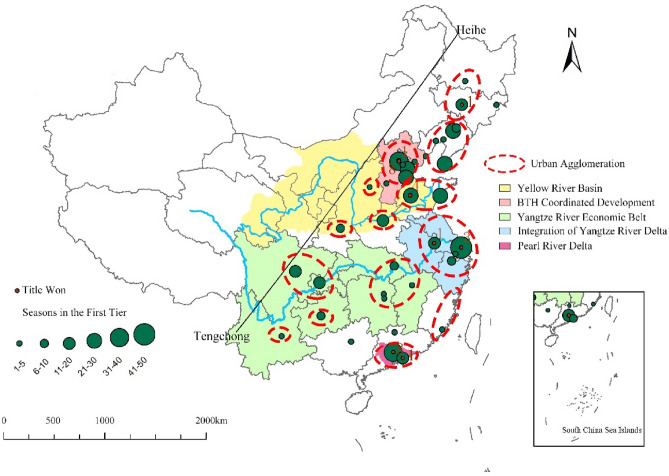

Then, ArcGis 10.2 software was used to map the information on the number of participations and the cumulative number of championships won by League A and Chinese Super League clubs during the period from 1994 to 2021, and the important geographic information on the provinces and cities where the clubs are located, city clusters, as well as the Yangtze River Economic Belt and the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei Synergistic Development Area were synthesized and illustrated in Fig. 1. From the overall distribution, Chinese professional football clubs are mainly concentrated in the 19 city clusters of the “two horizontal and three vertical” pattern. The clubs show regional distribution differences, with more clubs in the east than in the west. Champion teams are located mainly in the coastal city clusters in the east, with Dalian and Guangzhou each having nine championship records. China’s overall geographical features largely determine this overall distribution characteristic. The Eastern region of China has stable terrain and climate conditions, and both early economic development and most professional clubs settled in cities with developed transportation and infrastructure. In addition, the distribution of professional football clubs is to the southeast of the “Black River-Teng Chong” Chinese-population-dividing line, which fully illustrates the close relationship between the distribution of clubs and the number of people. A large population base will undoubtedly benefit the development of football talent and the cultivation of fan consumer groups. From the perspective of city clusters, the clubs in the Liaoning central–southern city cluster, Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei city cluster, Shandong Peninsula city cluster, Yangtze River Delta city cluster, and Pearl River Delta city cluster in the eastern coastal area have an absolute advantage in the number of match participation and often have multiple high-level clubs. Contrastingly, in urban clusters, such as the Tianshan North Urban Cluster, Hulunbuir–Baotou–Ordos Urban Cluster, Ningxia Along the Yellow River Urban Cluster, and Lanzhou–Xining Urban Cluster, there are not enough top-tier football clubs. Most of these urban clusters are in the northwest arid and semi-arid regions, with a terrain that includes primarily mountain and plateaus. Some urban clusters are even affected by the cold climate of the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau. These factors increased the difficulty of football infrastructure construction and outdoor football matches, additionally constraining the development of local professional clubs.

Figure 1.

Map of the distribution of Chinese professional football clubs, titles, and seasons.

Spatial–temporal distribution of club athletic levels

Based on the analysis of the spatial–temporal distribution characteristics of the clubs, this study further examined the distribution characteristics of the athletic levels. According to the development of professional football in China, the representative time points of 1994 (establishment of the professional league), 2004 (establishment of Chinese Super League), and 2020 (before the suspension of the league due to the COVID-19 epidemic) were selected. The league points index of each province’s clubs for the current season (i.e., the ratio of accumulated points to the highest points) was used as the leading indicator reflecting athletic level. Moran’s I spatial autocorrelation index was used to study the spatial relationships of the athletic level of the professional football clubs in various provinces and cities in China. According to the calculation results, the global Moran’s index of professional football athletic levels in various provinces and cities in China during the three important time nodes were − 0.158 (1994), − 0.230 (2004), and − 0.063 (2020). The changes in this index indicate differences in the distribution of athletic levels among professional football clubs in China. There are also significant differences in athletic levels among neighboring provinces and cities.

The spatial autocorrelation fluctuates but is always in the negative. This suggests that over the past two decades there has been significant geographic heterogeneity in the competitive level of professional clubs in China, and that these heterogeneous regions are geographically linked, but the differences improve significantly as the value declines in 2020. This phenomenon exists mainly due to the fact that the provinces at the junction of the second and third ladders have greater differences in the development of professional soccer, i.e. the sum of the number of provinces and municipalities in the second and fourth quadrants accounts for more than half of the total number of provinces and municipalities, which are susceptible to negative correlation. The reason for the lower global Moran Index in 2020 is due to the fact that some provinces and municipalities from the fourth quadrant have moved into the first quadrant.

Table 1 shows the specific evolution of the different quadrants at the three important time nodes. From the table, we can observe the following: (1) The number of provinces and cities in the first quadrant increased significantly in 2020, reflecting the trend of the increasing concentration of the distribution of professional football athletic levels in China, and the highest value of the “high–high” type aggregation usually appears in the Beijing area. (2) The number of provinces and cities in the second and third quadrants has always been relatively high. Among them, the development of professional football in the northeastern region is not optimistic. Except for Liaoning Province, which enters the first or fourth quadrant, Heilongjiang Province has been in the third quadrant for a long time, and Jilin was in the “high–high” type aggregation state in 1994, but then gradually entered the “low–high” and “low–low” type quadrants, reflecting the continuous decline in the level of football development in the province and surrounding areas. Other provinces, such as Xinjiang, Tibet, and Inner Mongolia, cannot change their professional football development status in the short term with ease due to factors such as the natural environment and economic development. (3) The number of provinces and cities in the fourth quadrant continues to decrease. Except for Guangdong Province, which has maintained a “high–low” type aggregation state for a long time, Liaoning, Shandong, Shanghai, and other provinces and cities that were in the fourth quadrant in 1994 and 2004 jumped to the first quadrant in 2020, moving from the “high–low” to “high–high” type aggregation. This change reflects the improvement in the professional football development level in the surrounding provinces and cities and also leads to the increase in the global Moran’s index in 2020.

Table 1.

Quadrant evolution of the Moran index of professional football at competitive levels in each province and municipality.

| Quadrant | 1994 | 2004 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|

| First quadrant HH | Jilin and Jiangsu (2) | Tianjin and Beijing (2) | Shandong, Liaoning, Hebei, Beijing, Jiangsu, and Shanghai (6) |

| Second quadrant LH | Inner Mongolia, Hebei, Fujian, Heilongjiang, Hainan, Guangxi, Hunan, Jiangxi, Henan, Tianjin, and Zhejiang (11) | Jilin, Hebei, Jiangsu, Hunan, Fujian, Hainan, and Guangxi (7) | Tianjin, Shanxi, Henan, Anhui, Zhejiang, Jiangxi, Fujian, Hunan, Guangxi, and Hainan (10) |

| Third quadrant LL | Xinjiang, Tibet, Qinghai, Gansu, Ningxia, Shaanxi, Hubei, Anhui, Chongqing, Yunnan, and Guizhou (11) | Xizang, Xinjiang, Inner Mongolia, Qinghai, Gansu, Ningxia, Shaanxi, Shanxi, Hubei, Henan, Anhui, Zhejiang, Yunnan, Guizhou, and Heilongjiang (15) | Heilongjiang, Shaanxi, Ningxia, Qinghai, Tibet, Guizhou, Yunnan, Sichuan, Jilin, Inner Mongolia, Gansu, and Xinjiang (12) |

| First quadrant HL | Beijing, Shanxi, Sichuan, Guangdong, Shanghai, Shandong, and Liaoning (7) | Shanghai, Guangdong, Liaoning, Shandong, Sichuan, and Chongqing (6) | Guangdong, Chongqing, and Hubei (3) |

The number in parentheses represents the total number of that category.

H represents a high level of development and L represents a low level. The HH quadrant represents a “high–high” agglomeration, with both the self-development level and the development indicators of the surrounding areas being high, and the spatial difference being small; the LL quadrant represents a “low–low” agglomeration, where both the self-development level and the development level of the surrounding areas are low, and the spatial difference is small; HL represents a “high–low” agglomeration, where the self-development level is higher than that of the surrounding areas, and the spatial difference is large; and LH is a “low–high” agglomeration, which is the opposite of the HL agglomeration.

Analysis of the characteristics of professional football club relocation in China

Types and characteristics of club relocation

According to the three-level division of China’s administrative regions (the first-level including municipalities, the second-level including provincial capital cities and sub-provincial cities, and the third-level including other cities) in the “Administrative Division Handbook of the People’s Republic of China” published by the Ministry of Civil Affairs, this study divided club relocation into the following three types: (1) downward relocation, which refers to the relocation of clubs from higher-level cities to lower-level cities; (2) upward relocation, which refers to the relocation of clubs from lower-level cities to higher-level cities; and (3) parallel relocation, which refers to the relocation of clubs between cities of the same level21. At the same time, we distinguished whether the three types of relocation involved cross-provincial relocation, and calculated the relocation distance to provide the specific relocation situation of China’s top-level professional football clubs (Table 2).

Table 2.

Migration of Chinese professional football clubs.

| Relocation type | Total number | Inter/intra-provincial migrations | Period | Average migration distance (km) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Downward relocation | 10 | 4/6 | Jia A | 565.9 |

| Upward relocation | 6 | 3/3 | Jia A | 470.9 |

| Parallel relocation | 8 | 7/1 | Jia A | 788.1 |

| Total | 24 | 24 | Jia A | 608.3 |

| Downward relocation | 6 | 4/2 | CSL | 932.2 |

| Upward relocation | 9 | 5/4 | CSL | 591 |

| Parallel relocation | 13 | 4/9 | CSL | 560.8 |

| Total | 28 | 28 | CSL | 694.7 |

Calculated using the ArcGIS 10.2 software.

According to the statistical results, the overall characteristics of the migration of professional football clubs in China are as follows: (1) In terms of the total number of migrations, during the period of the Chinese Football Association (CFA) League A, an average of about 2.4 club migrations occurred per year, indicating a higher frequency of migrations. However, during the Chinese Super League (CSL) period, an average of about 1.6 migrations occurred per year, indicating an improvement in league stability. (2) In terms of downward migration, there were a total of 10 downward migrations during the CFA League A period, accounting for 41.6% of the total number of migrations, while the number of downward migrations during the CSL period decreased to six times, accounting for only 21.5% of the total. Downward migration usually means clubs have relinquished cities with better locations and development advantages. Clubs often have to pay considerable migration costs and abandon long-term accumulated fans, which may have a negative impact on the development of clubs and the league. (3) Regarding parallel and upward migrations, the total number and proportion during the CSL period were significantly higher than those during the CFA League A period. Generally, parallel or upward migrations allow clubs to move to cities with similar or better economic conditions, infrastructure, and other conditions. Clubs are more likely to adapt to environmental changes before and after migration and usually receive a better support in terms of corporate investment and government subsidy policies. In addition, due to the recent restrictions on inter-provincial migration at the institutional level, the frequency of intra-provincial migrations of CSL clubs is significantly higher than that during the CFA League A period, accounting for 53.6% of the total number of migrations.

The mean center of the distribution of professional football clubs in China is basically in Anhui, Shandong, Jiangsu, and Henan, which is in contrast to the geometric center of China near Lanzhou (103° 50′ E, 36° N), where the mean center of clubs has been deviating from the southeast by about 700 to 1000 km, which suggests that the unevenness of the geographic distribution of professional football clubs in China is significant. During the period of CFA League A, the mean center of club distribution had a clear tendency to move to the southwest. In the first 2 years of CFA League A, the average center of clubs was in the relatively northeastern part of the country. Between 1995 and 1999, the repeated promotion and relegation of several teams in the Guangdong area led to a back-and-forth movement of the average center between Shandong and Henan, as well as between the northeastern and southwestern directions. During this period, the mean center of the participating clubs in the 1996 CFA League A shifted southward to Hubei for the first time, mainly due to the relegation of two northern teams in Shenyang and Qingdao, while two clubs in Guangdong Province succeeded in the “Super League”, and Bayi Football Team moved southward to Kunming, which was the southernmost point in the history of the mean center of the top league clubs in professional football. The center reached the southernmost part of China. In the later stages of the CFA League A, due to the emergence of top league clubs in cities in the central part of China such as Chengdu, Chongqing, Wuhan and Xi'an, the average center of the league as a whole showed a tendency to move to the southwest, and then, due to the abolition of the promotion and relegation of the league, the average center of the league remained relatively stable near Henan.

Changes in the center of average in the CSL period were more frequent and disorderly, with a small southward shift in the center of average relative to the CFA League A period, with three fewer clubs participating in the inaugural CSL in 2004 than in the final CFA League A, which were located in Chongqing, Xiangtan, and Xi’an, and coincided with the dissolution of Sichuan Quanxing Professional Football Club in 2006, which led to a more northeasterly center of average in the previous years, with no significant change in the distribution of the other clubs. In the absence of any significant change in the distribution of other clubs, this directly led to the average center of the Chinese Super League clubs being in the more northeastern part of the country in the first few years. Later, due to the participation of clubs from Hangzhou, Zhengzhou and Xi’an, the average center of professional football clubs shifted to the southwest during the 2008 and 2009 seasons. With the return of Liaozhu to the Chinese Super League after 10 years of silence, the center of distribution of clubs in the top league shifted eastward again. 2012 saw the dissolution of Dalian Shide Professional Football Club, 2016 saw the relocation of Harbin Yiteng Professional Football Club to Shaoxing, 2017 saw the relegation of Liaozhu to the Chinese Super League and its cancellation in 2020, and 2019 saw the announcement of the bankruptcy of Yanbian Fude Professional Football Club, which saw clubs in the northeast region suffer in comparison to their heydays. Clubs in the Northeast have suffered, with Dalian Ren and Changchun Yatai remaining in the Chinese Super League. Due to the steady development and progress of clubs in Chongqing, Zhengzhou and Wuhan, and the emergence of several top league clubs in eastern mega-cities such as Shanghai and Guangzhou, the average center of top league clubs is moving south again. All in all, the average center movement of clubs during the Super League period was more affected by performance, relocation, dissolution and rising stars, and there were more uncertainties, but there was no outstanding change in the overall dynamics of the distribution of clubs in the top league.

In fact, building stable “Century Clubs” has always been the vision of Chinese professional football, but the lack of their own competitive strength makes the clubs’ revenue capacity insufficient, thus relying on a large number of government and corporate support, which makes the distribution and relocation of clubs greatly affected by external factors. Specific additional analysis of the above phenomenon, taking the latest club migration in 2024 as an example, Shenzhen Peng City Football Club went from Chengdu to Shenzhen, and was subjected to a longer period of abuse on the Internet, with Shenzhen fans not feeling a sense of belonging, while Sichuan fans had a very bad attitude towards it. In fact, this is a professional football club migration due to the difference in government support and the change of investment enterprises in the two places. City Group entered the Chinese market as a foreign group, and is more open to investment in open coastal cities like Shenzhen.

Characteristics of club migration during the CFA League A and CSL periods

Since the establishment of the top-tier league in China, football clubs have migrated 52 times. Among them, there were 24 migrations during the CFA League A period and 28 during the CSL period. During the CFA League A period, there were more club migrations in the southern and northeastern regions. Among them, Guangdong Province in southern China had four participating teams in 1996. Later, due to changes in investment companies, only Shenzhen Jianlibao Club remained in Guangdong Province by the end of the CFA League A period. Among the eastern coastal regions, such as North China, East China, and South China, only the net migration of clubs in East China was positive. Compared with North and South China, clubs tended to move to southwestern provinces, such as Yunnan and Guangxi. The Bayi Club, Guangdong Hongyuan Club, and other teams successively moved to cities, such as Kunming and Nanning. In contrast, cities in the northwest region face challenges in creating and retaining high-level clubs. During the CFA League A period, only the Bayi club stayed in Shaanxi Province for one season.

During the Chinese Super League period, there were changes in the characteristics of club migration, with most of the club migrations occurring in the northeast, North China, and East China regions. Among them, the number of clubs migrating in and out of East China was as high as nine, with a final net migration of zero. Beijing and Shijiazhuang in North China attracted new club migrations. They became the only region with a positive net migration, while clubs in Hebei underwent many intra-provincial migrations between Shijiazhuang, Tangshan, Qinhuangdao, and Langfang. Although the northeast region has a strong football foundation, the number of clubs migrating out of it during the Chinese Super League period was more significant than the number migrating into it. The clubs that migrated out were mainly cross-province and south-ward, with intra-provincial migrations mainly coming from changes in Liaozu. In addition, the net migration in the northwest region was − 1, while there was no net migration in clubs in the southwest, South China, and Central China regions. Compared to the CFA League A period, the frequency of club migration during the Chinese Super League period dramatically decreased. Furthermore, due to the requirement in the “China Football Association Professional Football Club Transfer Regulations” in 2016, which strictly prohibits club transfers across provinces and cities, the number of intra-provincial migrations of clubs during the Chinese Super League period exceeded the number of cross-province migrations, and the overall concentration of club distribution gradually increased.

Influencing factors of the distribution and migration of Chinese football clubs

The development level of Chinese professional clubs is insufficient, they are not yet self-sustainable, not to mention that they cannot bring great economic value, and they are more dependent on investors and sponsors, especially when they are promoted and relegated, the problems of investment turnover and management are relatively prominent, and the relocation of professional football clubs is more frequent. The investor companies also lack long-term vision and are eager to enhance the popularity of the bureau, seizing the government’s temporary concessions and requesting the clubs to relocate. In addition, the ability and performance of the clubs have not yet reached the desired goals, and at the same time, they lack the sense of cooperation, and there is the phenomenon of avoiding the strongest teams in the same city and choosing to leave. In conclusion, the reasons why clubs blindly relocate and face relegation or even dissolution come from many aspects such as clubs, enterprises, policies, etc. There is a lack of understanding of the main position of professional football clubs themselves, as well as a lack of scientific thinking about regional economic development, fan support capacity, and the development of regional sports industry. Therefore, combining the actual distribution and migration phenomenon of professional football clubs in China, we should think about the influencing factors from the perspectives of regional heterogeneity and location advantages, in order to achieve the medium- and long-term stability of professional football clubs.

Classification of the influencing factors

Referring to the existing research by Honggang et al.22, this article focused on analyzing the three main factors that affect the distribution and migration of professional football clubs in China: regional economic and population levels, regional sports industry development, and club investment enterprises. Among them, (1) in terms of the regional economic and population levels, referring to the research by Heng et al.23 and Hongyan24, the per capita GDP, the total output value of the tertiary industry (referred to as “the third industry” below), and the number of permanent residents in each province and city were selected as the main indicators to explore the influence of economic and population factors on club distribution and migration. (2) In terms of the development level of the regional sports industry, referring to the research by Ping25 and Jiashu et al.26, the impact of the development level of the sports industry and the supply of sports-related institutional factors were mainly analyzed. (3) In terms of club investment enterprises, mainly by collecting and presenting the names, nature, and main business of the top league professional club investment enterprises over the years, the correlation between enterprise changes and club distribution and migration was analyzed.

Regional economy and population factors

Regional economic factors

According to the statistical results of this study, the global Moran’s I index values of the per capita GDP in China in 1994, 2004, and 2020 were 0.173, 0.265, and 0.108, respectively, and the provinces and the number of provinces in each quadrant were relatively stable27. The provinces and cities in the “high–high” quadrant are mainly located in the North China and East China regions, of which Shanghai, Guangdong, and other regions have long maintained a leading position in terms of the per capita GDP Moran’s I index. Regarding the tertiary industry, the Mo-ran’s I index values at the three important time nodes were − 0.048, 0.180, and − 0.007, respectively. The number of provinces and cities in the first and third quadrants ac-counts for the majority, reflecting the positive externalities and economies of scale of service industry agglomeration28. The main provinces and cities in the “high–high” and “high–low” quadrants are Shanghai, Beijing, Guangdong, and Sichuan.

Table 3 presents the economic indicators of the provinces and cities in the “high–high” and “high–low” agglomerations of competitiveness at the three important time nodes. From the data in the table, the following can be inferred: (1) In the 1994 season, among the 18 economic indicator data of the nine provinces and cities in the first and fourth quadrants of competitiveness, 12 were in the first and fourth quadrants. In 2020, among the economic indicator data of the nine provinces and cities, 14 were in the first and fourth quadrants, including 9 first-quadrant indicators. The impact of economic development level on the development level of professional football is increasingly prominent. (2) Except for Jilin Province at the early stage, the provinces and cities whose economic indicators did not enter the first and fourth quadrants in the later stage were mainly Liaoning and Chongqing. Among them, Liaoning Province belongs to a sports province with a foundation for training sports talents, while Chongqing has become an important region for the rapid development of professional football in recent years, relying on its advantages in the economy and trade, transportation, and other aspects29. Overall, as time progresses, the influence of regional economic development level on club distribution and migration continues to increase.

Table 3.

Quadrant distribution of economic indicators for the provinces and municipalities in quadrants 1 and 4.

| Time node | Competitive level (first quadrant) | Quadrant of per capita GDP and tertiary industry value | Proportion | Competitive level (fourth quadrant) | Quadrant of per capita GDP and tertiary industry value | Proportion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1994 | Jilin, Jiangsu (2) |

First Quadrant (2) Second Quadrant (1) Third Quadrant (1) |

1/2 | Beijing, Shanxi, etc. (7) |

First Quadrant (4) Second Quadrant (1) Third Quadrant (3) Fourth Quadrant (6) |

5/7 |

| 2004 | Tianjin, Beijing (2) | First Quadrant (3) Second Quadrant (1) | 3/4 | Shanghai, Guangdong, etc. (6) |

First Quadrant (3) Third Quadrant (3) Fourth Quadrant (6) |

3/4 |

| 2020 | Shandong, Hebei, etc. (6) |

First Quadrant (8) Second Quadrant (1) Third Quadrant (2) Fourth Quadrant (1) |

3/4 | Guangdong, Chongqing, etc. (3) |

First Quadrant (1) Second Quadrant (1) Fourth Quadrant (4) |

5/6 |

The number in parentheses represents the total number of that category.

The data in the “Proportion” column are the percentages of per capita GDP and the total output value of the tertiary industry in the first and fourth quadrants.

Population factors in different regions

According to the research and analysis results, the Moran’s index values of the resident population in each province of China were 0.043, 0.013, and − 0.086 in three stages, respectively. From the quadrant distribution, as a populous country, China’s provinces with a “high–high” type of agglomeration were mainly concentrated in the central and eastern regions. The provinces and cities in the fourth quadrant were fewer, mainly Sichuan in the southwest and Guangdong adjacent to Hainan. The population’s impact on professional football clubs mainly includes sports talent reserves and the number of fans. In terms of sports talent reserves, there are significant differences in the distribution of the residents’ health levels in China, roughly showing a symmetrical pattern of decreasing “T” shape30. Horizontally, it decreases from east to west, and vertically, it decreases from north to south. In Liaoning, Shandong, Hebei, and other provinces and cities in the first quadrant, the urban population is significant, and their physical fitness is good, suitable for cultivating sports talents. Similarly, in Guangdong, Shanghai, Zhejiang, and other places with good development in per capita health expenditure and urbanization level, athlete training is also advantageous. In terms of the number of fans, sufficient population resources contribute to the growth of the fan group, thereby stimulating consumer-generated fan benefits. In Beijing, Shanghai, Guangdong, Jiangsu, and other places, the high-level concentration of high-income individuals undoubtedly benefits the commercial development and tapping of local clubs31. In Henan, Sichuan, and other relatively economically backward provinces and cities, the population advantage also enables clubs to have many support groups, supporting the long-term development of local professional football clubs.

Overall, in the initial stage of professional football development, provinces and cities in the eastern and central regions of China achieved a leading position in the development of professional football based on their economic and population advantages. Although provinces, such as Sichuan, Shanxi, and Shaanxi, do not have advantages in terms of economic development, their population and/or service industry advantages can also support the development of professional football. After 2004, the “high–low” type of agglomeration of competitive football levels continued to decrease, and economically developed provinces and cities with a large population gradually formed an agglomeration of competitive levels. The development advantages of professional football in regions such as Beijing, Shandong, Shanghai, and Guangdong continued to increase. Chongqing and Hubei became the only remaining “high–low” agglomeration type in the central and western regions.

Factor analysis of the development level of the regional sports industry

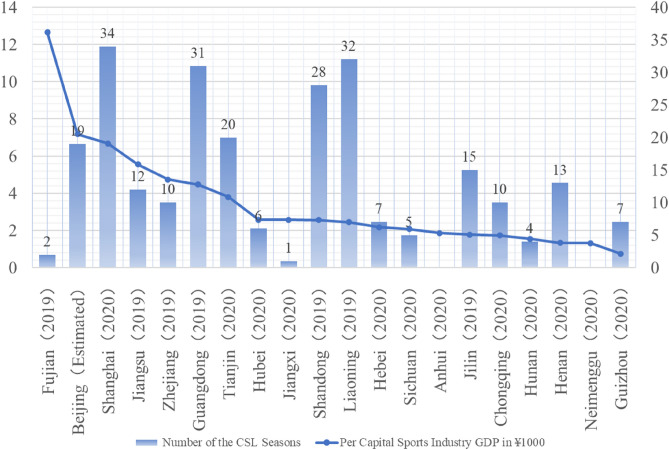

In addition to the overall economic and social development level of a region, the development level of the sports industry undoubtedly impacts the distribution of professional football clubs. Since the State Sports Commission issued the “Outline for the Development of the Sports Industry” in 1995, the development of the sports industry has gradually become an important driver for promoting high-quality economic development and achieving economic transformation in various provinces and cities. From 2015 to 2019, China’s sports industry’s total output and value added maintained a steady double-digit growth. In 2019, the total size (total output) of the national sports industry reached CNY 2.9483 trillion, with an added value of CNY 1.1248 trillion, and the added value of the sports industry accounted for 1.14% of the GDP32. Figure 2 shows the per capita sports industry GDP values of some provinces and cities in 2019 and 2020 and the total number of seasons in which their CSL clubs participated.

Figure 2.

GDP per capita of the sports industry and the number of CSL entries in selected provinces and municipalities.

From the data in the figure above, it can be seen that: (1) Among the seven provinces and cities with advantages in sports industry development and per capita sports industry GDP exceeding the “14th Five-Year Plan” development target, such as Guangdong, Shanghai, Beijing, and Tianjin, the number of seasons in which CSL clubs participated is significantly higher than that in other provinces and cities, while the participation status of clubs in provinces such as Fujian, Jiangsu, and Zhejiang is far behind their level of sports industry development. (2) Among the provinces and cities with a higher per capita sports industry GDP than the national average in 2019, the number of participating seasons of Shandong and Liaoning clubs surpasses that of other provinces and cities. (3) Among the provinces and cities with a lower per capita sports industry GDP than the national average, only the total number of seasons in which clubs in Jilin, Henan, and Chongqing participated reached 10 or more. Other provinces, such as Anhui and Inner Mongolia, never had CSL clubs. Overall, there is a close correlation between the distribution of CSL-club-participating seasons and the level of sports industry development. It is worth noting that the degree of importance that local governments attach to the development of the sports industry will also affect the migration of clubs. For example, the Guiyang city government welcomed the Guangzhou Songri team and Shaanxi Renhe team in 1999 and 2012, respectively, by providing supportive policies. In the process of the relocation of Shijiazhuang Yongchang Club to Cangzhou City in 2021, the Cangzhou city government also provided support in terms of venue and funding, and clearly stated the goal of cooperating with Yongchang Group and improving the development of the football industry in the “Cangzhou Municipal Government Work Report”.

Factors affecting the investment enterprises of football clubs

In addition to the region’s economy, population levels, and the level of sports industry development, the factors of investment enterprises undoubtedly also have an important impact on the distribution and migration of professional football clubs. Table 4 presents the main investment enterprises of China’s top-level league football clubs at three different time nodes.

Table 4.

Main investment enterprises of Chinese top-league clubs in different periods.

| Season | Enterprise type | Main business | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Private | State-owned/mixed ownership | Non-enterprise | ||

| 1994 | Wanda Group, Sun God Group, Far East Group, Hongyuan Group, Samsung Group, and Met Group | Shenhua Group, Quanxing Group, Northeast Six Drugs, and CITIC Group | Jinan Municipal Government and Central Military Commission Real | Estate (2), health products, household appliances, steel, liquor, electronics, pharmaceuticals (2), and finance |

| 2004 | Jianlibao Company, Sanlin Wanye, Zhongyu Group, Shide Group, Jinde Pipeline, Guancheng Group, and Lifan Industry | Shandong Electric Power, COSCO Group, Teda Group, CITIC Group, Shanghai Radio and Television, and Yizhong Industrial | – | Beverages, energy, real estate (3), transportation, automobiles (2), finance, building materials (2), media, and tobacco |

| 2022 | Evergrande Group, Alibaba, Zhonghe Land, Cordis Hotels, Fuli Real Estate, Jingyu Real Estate, Hongdao Investment, Yongchang Group, Zhuoer Group, Shangwen Real Estate, Greenland Group, and Yifang Group | Jinan Culture and Tourism, Shandong Electric Power, Shanghai SIPG Group, Jiarun Investment, Greenland Group, Cangzhou City Construction Investment, Guohong Management, Zhejiang Energy, and Xingcheng Group | – | Energy (2), port services, real estate (10), network technology, investment management (2), hotels, land development (2), and cultural tourism (2) |

The number in parentheses represents the total number of the business category before it.

Compiled based on, among others, the official websites of various clubs, the official website of the Chinese Football Association, and Baidu Baike.

During the period of the former Chinese Football Association CFA League, it was typical for private enterprises, state-owned enterprises (including mixed ownership), and non-enterprise sectors to invest in and manage clubs. At the same time, the main business of enterprises was also relatively diversified, and cases of companies from industries, such as liquor, tobacco, medicines, and home appliances, entering professional football were not uncommon.

In the early stages of the Chinese Super League, the main business of clubs’ investment enterprises began to change, and the number of enterprises in the real-estate-related industry increased, while companies from industries, such as liquor, tobacco, and medicines, gradually withdrew. The number of state-owned enterprises in the energy and transportation sectors tended to be stable.

After 2010, real estate companies investing in football became increasingly frequent. In the 2017 season, all 16 Chinese Super League clubs received investments from real estate companies, and 12 had real estate as their primary business. In the 2022 season, affected by various policies, such as neutral club names and salary caps, the number of state-owned enterprises participating in club investment significantly increased. There were more companies from other industries, such as energy, culture and tourism, and land development. Among the private enterprises, the number of real estate-related companies decreased compared to 2017, but it still surpasses the number of companies in other industries.

Changes in investment enterprises at different times have significantly impacted the distribution and migration of clubs. During the period of the former CFA League, frequent club downgrading and long-distance cross-provincial migration caused by changes in enterprises not only consumed considerable manpower, material, and financial resources, but also had a negative impact on the club’s rooting in the local area and the development of football industry and culture. In addition, the requirements for investment enterprise qualifications in the policy documents issued by managers during this period also impacted the distribution and migration of clubs. For example, since 2001, the Chinese Football Association has successively restricted situations where clubs and their shareholders invest in other clubs through relevant policies. Against this background, clubs such as Dalian Shide Longze, which had a mutual investment with other clubs, chose to move. In addition to changes in investment enterprises, clubs moving due to enterprise development needs are not uncommon. For example, in 2007, the Shenyang Jinde Group invested in building an industrial park in Changsha City to develop the southern market and agreed with the local government to move the club from Shenyang to Changsha as a whole. Although the company’s business development benefited from this, the migration severely affected the club’s development. Jinde’s home attendance rate in Changsha was far lower than that in Shenyang. In 2011, the club was moved to Shenzhen after being acquired and renamed Shenzhen Phoenix Club.

Conclusions

This paper used GIS spatial analysis and exploratory spatial analysis to study the spatial distribution and migration characteristics of Chinese professional football clubs and, combined with the spatial distribution of athletic ability, explored the correlation between regional economic and population, and sports industry development levels, investment enterprise changes, and club distribution and migration. The following conclusions were drawn: (1) In terms of club distribution, the spatial distribution of Chinese professional football clubs shows significant unevenness, and the “more in the east, less in the west” distribution pattern has relatively solidified over time, with professional clubs having formed a cluster centered on cities such as Guangzhou, Shanghai, and Beijing in the Eastern region. (2) In terms of club migration, from the CFA League to the Chinese Super League period, the migration frequency of Chinese professional football clubs gradually decreased. The long-distance cross-provincial and downward migration of clubs decreased, with the region with the most net inflow of clubs shifting from southwest to North China. The number of clubs owned by various provinces and cities gradually tended to stabilize. (3) Regarding the influencing factors, the distribution and migration of Chinese professional football clubs are mainly affected by regional economic and population, and sports industry development levels and in-vestment enterprise changes. Among them, investment enterprise changes directly affected the distribution and migration of clubs over a longer period, while the degree of influence of regional economic and population, and sports industry development levels and other factors on club distribution and migration gradually increased over time with the adjustment and improvement of top-level institutional arrangements.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Social Science Foundation of China (NO. 22BTY034).

Author contributions

Conceptualization, D.L., T.L.; methodology, D.L., M.C.; formal analysis, C.L., S.Y.; data curation, D.L.; writing—original draft preparation, D.L., T.L. and S.Y.; writing—review and editing, S.Y., T.L. and C.L.; visualization, D.L., M.C.; project administration, T. L.; funding acquisition, S.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data availability

The dataset used in this study is available from the corresponding author upon request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Tangyun Leng, Email: lengtangyun@126.com.

Shuo Yang, Email: yangshuo333499@163.com.

References

- 1.Chen, Y., Zhong, B., Zheng, X., Chen, W. & Wang, B. Analysis on the features and problems of professional football club regional distribution in China. J. Chengdu Sport Univ.3, 54–61. 10.15942/j.jcsu.2017.03.009 (2017). 10.15942/j.jcsu.2017.03.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tim, E. & Steve, M. ‘This is our city’: Branding football and local embeddedness. Glob. Netw.2, 172–193. 10.1111/j.1471-0374.2008.00190 (2008). 10.1111/j.1471-0374.2008.00190 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Putra, L. R. D. ‘Your neighbours walk alone (YNWA)’: Urban regeneration and the predicament of being local fans in the commercialized English Football League. J. Sport Soc. Issues1, 44–68. 10.1177/0193723518800433 (2018). 10.1177/0193723518800433 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roșca, V. Sustainable development of a city by using a football club. Theor. Empir. Res. Urban Manag.16, 61–68 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gutoiu, G. I. The entangled scalarities of football clubs in a competitive metropolitan space: Investment, identity and international events. Geogr. Ann. Ser. B Hum. Geogr.1, 1–19. 10.1080/04353684.2021.1958359 (2021). 10.1080/04353684.2021.1958359 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tian, Z. A brief discussion on sports culture diffusion—Concurrently on the distribution of football clubs in China. Hum. Geogr.2, 102–106 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhao, B. Study on the Distributions and Changes of Chinese Occupation Football Club Under the Perspective of Regional Economy (Fujian Normal University, 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen, K., Tang, W., Li, J. & Ding, L. Spatial–temporal distribution of Chinese top professional football clubs (1994–2013): Driving forces and mechanism. J. Tianjin Univ. Sport2, 99–105. 10.13297/j.cnki.issn1005-0000.2016.02.002 (2016). 10.13297/j.cnki.issn1005-0000.2016.02.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhong, B., Zheng, X., Chen, W., Chen, Z. & Wang, B. Research on the theories and policies of the localization and non-enterprise naming of Chinese professional football clubs. J. Cap. Univ. Phys. Educ. Sport2, 99–105. 10.14036/j.cnki.cn11-4513.2017.05.002 (2017). 10.14036/j.cnki.cn11-4513.2017.05.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hongyan, L. Research on the impact of China’s residents’ quality of life on regional sports development. Sports Cult. Guide01, 37–39 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Honggang, T. & Xuehua, W. A study of regional heterogeneity in the economic effects of environmental regulation. Mod. Econ. Discuss.04, 71–79. 10.13891/j.cnki.mer.2019.04.010 (2019). 10.13891/j.cnki.mer.2019.04.010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Walker, B. The demand for professional league football and the success of football league teams: Some city size effects. Urban Stud.23(3), 209–219. 10.1080/00420988620080241 (1986). 10.1080/00420988620080241 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baade, R. A. Professional sports as catalysts for metropolitan economic development. J. Urban Affairs18(1), 1. 10.1111/j.1467-9906.1996.tb00361.x (2010). 10.1111/j.1467-9906.1996.tb00361.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li-Ping, Z., Liudong, L. & Pu-Phong, L. Sociological factors affecting the development of Chinese professional soccer clubs. J. Shandong Sports Inst.06, 33–36. 10.14104/j.cnki.1006-2076.2005.06.009 (2005). 10.14104/j.cnki.1006-2076.2005.06.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yibing, W. Measurement analysis of influential factors on the development of modern service industry clustering in China. Res. Bus. Econ.09, 173–175 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heng, L. & Jian, G. Analysis of the relationship between regional economic conditions and the development of sports professional clubs. J. Southwest Normal Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.)34, 122–126. 10.13718/j.cnki.xsxb.2009.03.042 (2009). 10.13718/j.cnki.xsxb.2009.03.042 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meng, H. Study on the Supporting Behavior of Football Fans in Shandong Professional Football League. Master’s Thesis, Shandong Institute of P.E. and Sports, Jinan, China, 2020. 10.27725/d.cnki.gsdty.2020.000031 (2020).

- 18.Wu, L., Li, X., Ma, L. & Shao, N. Regional differences and spatial polarization of competitive sports development in China. Econ. Geogr.1, 52–60. 10.15957/j.cnki.jjdl.2018.01.007 (2018). 10.15957/j.cnki.jjdl.2018.01.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stevens, D. L. & Olsen, A. R. Spatially balanced sampling of natural resources. J. Am. Stat. Assoc.99, 262–278. 10.1198/016214504000000250 (2004). 10.1198/016214504000000250 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pan, F., Xia, Y. & Liu, Z. The relocation of headquarters of public listed firms in China: A regional perspective study. Acta Geogr. Sin.4, 449–463 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pollard, R., Armatas, V. & Sani, S. H. Z. Home advantage in professional football in Iran—Differences between teams, levels of play and the effects of climate. Int. J. Sci. Cult. Sport5(4), 328–339. 10.14486/IntJSCS696 (2017). 10.14486/IntJSCS696 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tian, H. & Wu, X. A study of regional heterogeneity in the economic effects of environmental regulation. Mod. Econ. Res.4, 71–79. 10.13891/j.cnki.mer.2019.04.010 (2019). 10.13891/j.cnki.mer.2019.04.010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu, H. & Gong, J. Analysis of the relationship between the local economical condition and the development of the professional sports club. J. Southwest China Norm Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.)3, 122–126. 10.1718/j.cnki.xsxb.2009.03.042 (2009). 10.1718/j.cnki.xsxb.2009.03.042 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li, H. Research on the influence of the quality of life of Chinese residents on regional sports development. Sport Cult. Guide1, 37–39 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dai, P. Theoretical thinking and basic assumption of supply side reform in sports industry. J. Beijing Sport Univ.8, 21–26. 10.19582/j.cnki.11-3785/g8.2017.08.004 (2017). 10.19582/j.cnki.11-3785/g8.2017.08.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hu, J. & Huang, H. Characteristics, sources, and dynamics of the development potential for sports events industry. J. Phys. Educ.6, 59–66. 10.16237/j.cnki.cn44-1404/g8.2021.06.008 (2021). 10.16237/j.cnki.cn44-1404/g8.2021.06.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang, J. & Tang, G. Spatial–temporal migration characteristics and driving mechanism of manufacturing enterprises in Zhejiang: Based on county scale. Econ. Geogr.6, 118–126. 10.15957/j.cnki.jjdl.2019.06.013 (2019). 10.15957/j.cnki.jjdl.2019.06.013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang, M., Li, W. & Wu, Q. The impact of manufacturing and productive services agglomeration on urban economic efficiency. Res. Financ. Econ. Issues9, 36–44. 10.19654/j.cnki.cjwtyj.2021.09.005 (2021). 10.19654/j.cnki.cjwtyj.2021.09.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang, X., Chen, Y. & Liu, B. Exploratory spatial data analysis about the development level of the regional real estate economy in China—The research based on Global Moran’ I, Moran scatter plots and LISA cluster map. J. Appl. Stat. Manag.1, 59–71. 10.13860/j.cnki.sltj.2014.01.015 (2014). 10.13860/j.cnki.sltj.2014.01.015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhao, X., Wang, W. & Wan, W. Regional inequalities of residents’ health level in China: 2003–2013. Acta Geogr. Sin.4, 685–698 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhu, Y. & Zhang, B. The future trend of China’s consumption under the change of demographic structure—Analysis based on the data of the Seventh National Census. J. Shaanxi Norm Univ. (Philos. Soc. Sci. Ed.)4, 149–162. 10.15983/j.cnki.sxss.2021.0722 (2021). 10.15983/j.cnki.sxss.2021.0722 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fan, S. & Bai, Y. Research on the changes and optimization path of sports industry structure in China. J. Xi’an Inst. Phys. Educ.5, 533–540. 10.16063/j.cnki.issn1001-747x.2022.05.003 (2022). 10.16063/j.cnki.issn1001-747x.2022.05.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset used in this study is available from the corresponding author upon request.