Abstract

Using ex vivo microscopy, virtual pathology can improve histological procedures by providing pathology images in near real-time without tissue destruction. Several emerging and promising approaches leverage fast-acting small-molecule fluorescent stains to replicate traditional pathology structural contrast, combined with rapid optical sectioning microscopes. However, several vital challenges must be addressed to translate virtual pathology into the clinical environment. One such challenge is selecting robust, reliable, and repeatable staining protocols that can be adopted across institutions. In this work, we addressed the effects of dye selection and staining protocol on image quality in rapid point-of-care imaging settings. For this purpose, we used structured illumination microscopy to evaluate fluorescent dyes currently used in the field of ex vivo virtual pathology, in particular, studying the effects of staining protocol and temporal and photostability on image quality. We observed that DRAQ5 and SYBR gold provide higher image quality than TO-PRO3 and RedDot1 in the nuclear channel and Eosin Y515 in the extracellular/cytoplasmic channel than Atto488. Further, we found that TO-PRO3 and Eosin Y515 are less photostable than other dyes. Finally, we identify the optimal staining protocol for each dye and demonstrate pan-species generalizability.

Subject terms: Biomedical engineering, Microscopy, Cancer imaging

Introduction

Histopathology uses formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue preparation as the gold standard in clinical cancer diagnosis. The histopathology procedure consists of four tissue preparation steps before microscope slides are ready for diagnostics. Those steps include gross processing, tissue fixation and hardening, physical sectioning, and tissue staining. Although this procedure is well established in clinical environments, those steps are time-consuming, and one sample preparation can take several hours to a few days. Recent technology developments allow two new pathology procedures—digital pathology (DP) and virtual pathology (VP). Digital pathology depends on the standard preparation processes of histopathology but uses specialized automated microscope scanners to acquire digital images of the resulting microscope slides. This technology allows pathologists to view slides on a computer screen instead of directly through the microscope oculars and enables more accessible data storage and sharing.

On the other hand, virtual pathology represents a potential revolutionary shift in the field. By directly imaging fresh, intact samples, it bypasses the need for processed tissue sections on slides, effectively eliminating the time-consuming steps of gross processing, tissue fixation, and tissue sectioning. Instead of relying on physical sectioning to obtain images of thin layers of tissue, some virtual pathology techniques employ optical sectioning. These techniques can utilize label-free or fluorescence-enhanced imaging, marking a significant departure from traditional methods. Label-free VP methods intended for use on fresh intact tissues use autofluorescence1, scattering or refractive index changes (e.g. optical coherence tomography2), photoacoustic absorption contrast3, quantitative phase contrast4, multiphoton microscopy (second harmonic5,6 and third harmonic7 generation) or Raman spectroscopy techniques (CARS8 and SERS9). On the other hand, fluorescence-enhanced VP techniques use the application of exogenous fluorescence dyes or stains to label DNA (nuclear dyes) and/or cellular and extracellular structures (cytoplasmic/extracellular matrix (ECM) dyes). There are several well-established techniques for fluorescence VP of fresh tissue such as confocal microscopy10, structured illumination microscopy11–17, light sheet microscopy18, nonlinear microscopy19–21 and microscopy with ultraviolet excitation (MUSE)22 that allows high quality pathologic imaging of thick samples. Structured illumination microscopy (SIM) achieves optical sectioning by illuminating the sample with a specially designed light pattern that can be precisely phase shifted, preferentially modulating the plane of focus and enabling computational retrieval of the modulated optical sections separate from the out-of-focus background23. The main advantages of SIM compared to other techniques are its large and readily scalable field-of-view, control over optical sectioning performance, and high imaging speed.

Histopathology and fluorescence VP both require dyes for labeling nuclear and ECM structures. Histopathology uses hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) for nuclear and ECM labeling. However, fluorescence virtual pathology cannot use hematoxylin because it does not fluoresce. Furthermore, fluorescence virtual pathology dye selection depends not only on the dye’s chemical properties (quantum yield, binding specificity) but also on the imaging system properties (illumination wavelength, acquisition sensor wavelength range). There is no agreement in the literature on which dyes should be used as hematoxylin and eosin equivalents in fluorescence VP. Some of the more popular ex vivo dyes in the literature24,25 are eosin11,26, Atto 65527, Atto 48828, rhodamine B29, sulforhodamine 10130 for ECM labeling, and DRAQ511, TO-PRO317,18, SYBR gold27, SYBR green28, Hoechst28, DAPI19, propidium iodide26, and RedDot131 for nuclear staining. In addition, some reports use dyes that label both nuclei and ECM, such as acridine orange12,14–16,32–34. Furthermore, in vivo VP uses dyes such as acriflavine35–39, proflavine40–42 and indocyanine green43 that are already accepted for in vivo use—however, the use of dyes in vivo until now has mainly focused on the use of single agents, rather than the dual-agent (nuclear + cytoplasm/ECM) approaches commonly used ex vivo.

Similarly, regarding dye selection, there is no broad agreement in the literature on the specific staining procedures to be used in fluorescence VP. The reported staining procedures vary in choice of fluorescence dyes, concentration, staining time, solvent type, necessity for rinsing, and choice of rinsing chemicals. However, only some studies explain in detail the guiding principles behind the selected staining procedure27. We found that the reported staining procedures can differ between studies even inside of the same research group, including ours, without a clear rationale10,11,18,19,21,26,27,44–48. For new groups entering the field of fluorescence VP, these procedure variations can make determining the most useful fluorescence VP staining protocol for one’s specific application difficult. Therefore, understanding the factors underlying reproducible staining procedures would be a significant step toward easier adoption in research settings and translation of fluorescence VP techniques to the clinic.

As a first step towards understanding the factors that contribute to successful fluorescence VP staining protocols, this paper presents a quantitative assessment of fluorescence dyes and staining protocols, based on SIM image analysis. We methodically analyze 585 different staining parameters on the same type of sample across four different commonly used fluorescence dyes. We assess the image signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and contrast dependence on fluorescence dye type, solvent, and staining and rinsing protocol, and evaluate their pan-species generalizability. Moreover, for the first time, we extend our characterization of fluorescence VP dyes to include temporal degradation and photobleaching effects on image quality over time in fresh tissues. In this work, we consider the context of using fluorescence VP for rapid imaging of fresh tissues soon after removal from the body, and thus limit our analysis to fast (i.e., no longer than 10 min) staining procedures on fresh, non-fixed and non-optically cleared samples.

Results and discussion

Nuclear dyes—DRAQ5, TO-PRO3, SYBR gold

For nuclear dye analysis, we first analyze the effects of solvent/rinsent, then concentration, on overall performance in terms of image quality metrics.

PBS as a solvent/rinsent outperforms all other combinations

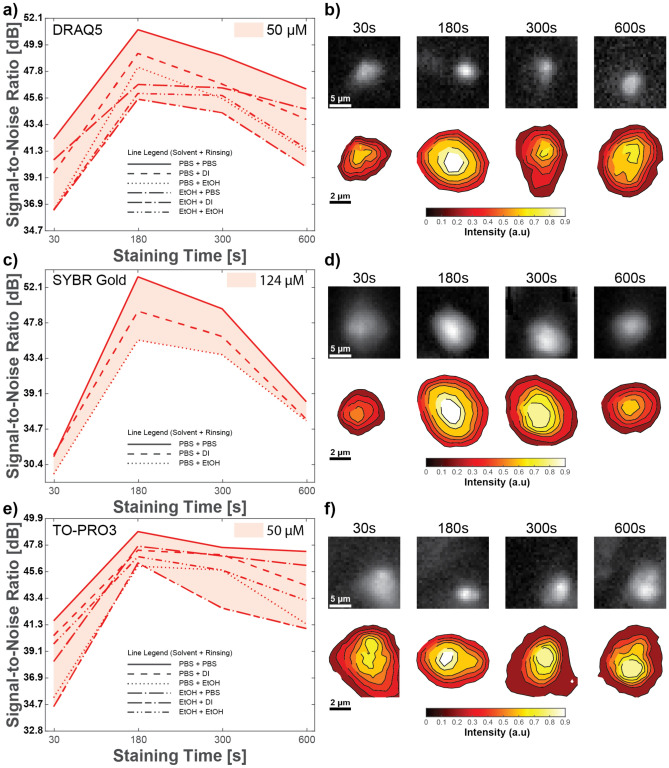

First, we analyzed the image quality dependency on the choice of solvent and rinsing solution (in future text, “rinsent”) for the nuclear dyes. To analyze these dependencies in Fig. 1, we plotted SNR for different solvents and rinsents over staining time while keeping fluorescence dye concentration constant for DRAQ5 (a), SYBR gold (c), and TO-PRO3 (e). From these plots, we can observe the following. First, overall trends of SNR dependency on solvent and rinsent for all three dyes are similar. Second, maximal SNR is achieved for all three dyes when PBS is used as the solvent and rinsent. Moreover, we saw that for DRAQ5, PBS as a solvent overperforms ethanol independently of the rinsent. In the TO-PRO3 cases, PBS/PBS overperforms any other combination of solvent/rinsent, followed by ethanol/PBS. This result aligns well with the manufacturer’s instruction to use PBS as the preferred solvent for DRAQ5, TO-PRO3, and SYBR gold. Conversely, a combination of ethanol/deionized water as a solvent and rinsent shows the worst image quality for DRAQ5 and TO-PRO3, and likewise PBS/ethanol in the case of SYBR gold. Finally, we observed that using the same solution for solvent and rinsent outperforms mixed combinations of solvent/rinsent, excluding the above-described TO-PRO3 case.

Fig. 1.

Image quality dependence on staining parameters for constant fluorescent dye concentration. (1) Image SNR dependency on solvent, rinsent, and staining time for a constant concentration of fluorescent dyes; (2) visualization of SNR dependency on staining time with PBS as solvent and rinsent, using images of nuclei and their surrounding neighborhoods; and (3) nuclear contour intensity plots, for 50 µM DRAQ5 (a,b), 124 µM SYBR Gold (c,d), and 50 µM TO -PRO3 (e,f).

Although we observed SNR variations depending on the combination of solvent and rinsent, these variations have a lower effect on fluorescence SNR than the dependence on staining time. To visualize SNR dependency on staining time at a constant concentration, we show images and contour plots of single representative nuclei with their surrounding neighborhoods in Fig. 1 for DRAQ5 (b), SYBR gold (d), and TO-PRO3 (f). All pixel intensities are normalized to the peak value for each dye separately. Images of individual nuclei at each timepoint are provided, as well as contour plots of the same nuclei to more easily compare relative brightness and contrast across the different timepoints. We can observe differences in intensity distribution within the nucleus for optimal timepoints. For example, for all dyes (Fig. 1d), we observe for peak SNR (180 s staining time at the concentrations used) that higher intensity contours occupy most of the nuclear area compared to other staining times. Second, lower-intensity contours are thinner in the peak SNR case (180 s staining time) than in other staining times, which helps for easier visualization of nuclei in the images. Finally, the transition between nucleus and background is sharper in the peak SNR case (180 s) than in others, which allows for easier nuclei visualization and should aid in more accurate segmentation. Interestingly, longer staining times can result in comparatively lower intensity nuclear staining, and therefore optimal staining times for nuclear dyes should be tested for a given concentration and solvent/rinsent pair.

Concentration and staining time influence SNR more than other staining parameters

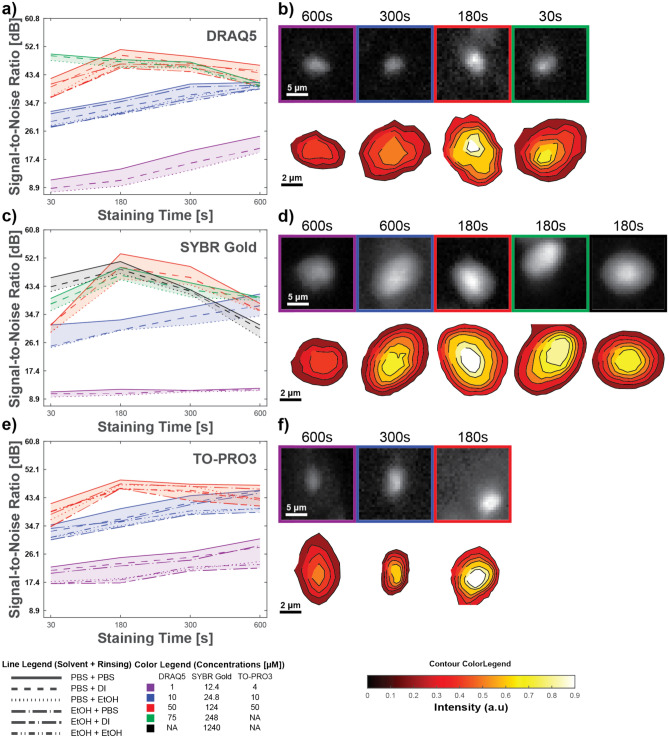

Whereas in the previous analysis, the dye concentration was held constant for each dye, we analyzed the effects of nuclear dye concentration on SNR. For this purpose, in Fig. 2, we provide SNR versus staining time for different concentrations of each dye and show images and contour plots of isolated nuclei as in the previous analysis. From Fig. 2, we can generalize our observation regarding the solvent/rinsent pairs and conclude that, independently of concentration, they similarly influence image SNR. Moreover, we observed that the solvent/rinsent pair of PBS provided the best SNR, independent of concentration.

Fig. 2.

Image quality dependence on fluorescence staining protocols for nuclear dyes. SNR dependency on fluorescent dye concentration and staining protocol, and visualization of SNR dependency on fluorescent dye concentration with PBS as solvent/rinsent and optimal staining time using an image of nuclei and its surrounding, and nuclei contour intensity plot for DRAQ5 (a,b), SYBR gold (c,d), TO -PRO3 (e,f).

We can group concentrations into three groups for each dye based on their behavior with increasing staining time. The first group includes fluorescent dye concentrations that show the trend of increasing SNR during the entire staining time. We observed this behavior for lower concentrations used in the experiment for each dye. The second group of concentrations has a clear peak at a staining time of 180 s. Finally, in the third group, we have only the highest concentration for DRAQ5, for which SNR decreases with staining time. Although we observed overall peak SNR for each dye using medium concentrations at 180 s staining time with PBS as the solvent and rinsent, it is possible that higher concentrations may exhibit maximal SNR for the staining times between 30 and 180 s (i.e., optimal results may be able to be obtained with high concentrations at intermediate staining times). However, we did not sample these times in our experiment. In any case, these results indicate that the choice of staining concentration and staining time are interdependent, that a combination of high staining concentration and longer staining time is not always the best, and that this should be tested for each nuclear dye to identify the optimal result.

We visualized the SNR dependency on dye concentration for each dye’s optimal staining time and solvent/rinsent combination. For this purpose, we used single nuclei with surrounding neighborhoods and contour plots of isolated nuclei, as shown in Fig. 2 for DRAQ5 (b), SYBR Gold (d), and TO-PRO3 (f). Again, all pixel intensities were normalized to the peak value for each dye separately. In nuclei images, we notice that, in general, changes in concentration influence nuclear signal intensity while the background stays the same. One exception is TO-PRO3, where we see increases in signal and background intensity with concentration increase. On the contour plots, we again observe that higher-intensity contours occupy most of the nuclei area for peak SNR, lower-intensity contours are thinner in the peak SNR case than in other cases, and the transition between nuclei and background is sharper in the peak SNR case than in others.

SYBR gold outperforms other dyes with high SNR and low cost

Finally, we can compare the SNR behavior across dyes using the optimal concentration and solvent/rinsent combination. For this purpose, in Fig. 3a, we plotted maximal SNR over staining time using PBS as a solvent and rinsent. DRAQ5 (black) and TO-PRO3 (cyan) achieved maximal SNR with a dye concentration of 50 µM and SYBR gold (red) with 124 µM. All three dyes achieved maximal SNR after 180 s of staining. From SNR measurements, we observed that SYBR gold has the highest SNR peak (~ 54.6 dB), followed by DRAQ5 (~ 51.3 dB) and TO-PRO3 (~ 49.3 dB). Furthermore, we observed that SNR measurements have a low standard deviation between ten ROIs for each dye, not exceeding ~ 3 dB for either dye or staining time. Interestingly, SYBR gold overperforms the other two dyes only for the 180 s staining time (i.e. it shows the highest sensitivity to staining time), with DRAQ5 and TO-PRO3 showing less overall sensitivity to staining time. For this comparison, we normalized nuclei image intensity (Fig. 3b) to the highest intensity across all nuclear dyes. From the images, we can see that the signal peak looks similar for all three dyes. However, we can now observe higher background levels in the close neighborhood of nuclei in both DRAQ5 and TO-PRO3.

Fig. 3.

Image SNR comparison between nuclear dyes. (a) Peak SNR measurement for middle dye concentration for PBS as solvent and rinsent for SYBR gold (red), DRAQ5 (black), and TO-PRO3 (cyan). Error bars show the standard deviation in 10 ROIs for each dye. (b) Image of nuclei surrounding and nuclei contour plot for peak SNR measured at 180 s staining time for each dye. (c) Example of nuclei profile for peak SNR for each fluorescence dye. (d) Full width half maximum distribution for 40 nuclei for peak SNR experimental measurements, * denotes p < 0.002. (e) Observation of increased background and signal in TO-PRO3 with increased staining time compared to no visible increase in background for SYBR gold with increased staining time. Histograms showed the measured signal intensities. In blue, we see a histogram for 30 s staining time, which is narrow with one dominant and narrow peak for both dyes. The red histogram for 600 s staining time for SYBR gold keeps the same shape as for 30 s but is slightly shifted rightward to higher intensity values, whereas for TO-PRO3 the histogram is broadened with much smaller peak values. This widening of the histogram for TO-PRO3 corresponds to increased levels of diffuse, low-intensity background in the TO-PRO3 case.

Finally, we wanted to compare nuclei cross-sections for maximal SNR measurements. Figure 3c-d shows a comparison of nuclei shapes. Figure 3c shows a cross-section example for each nuclei dye. In this example, we can observe the following: SYBR gold cross-section reaches the highest intensity and has the broadest profile of all dyes; DRAQ5 and TO-PRO3 profiles have similar width and height, and both are smaller than SYBR gold. The main difference between the profiles of DRAQ5 and TO-PRO3 is the intensity level of the background signal. To evaluate this observation, we ran a t-test on the full-width half maximum (FWHM) of 40 nuclei of each dye. We chose only nuclei whose cross-section was perpendicular to the illumination beam, so they have a circular shape on the image. Figure 3d shows the box and whisker plot for all three dyes. The t-test showed a difference between all three FWHM distributions, which are statistically significant with p < 0.002. The slightest significance was between SYBR gold and TO-PRO3 (p = 0.0018), which are approximately equally different from DRAQ5. SYBR gold and TO-PRO3 were more similar than DRAQ5 (p = 0.0018). DRAQ5 and TO-PRO3 distribution were closer compared to SYBR gold. The high DNA binding specificity for DRAQ5 likely explains why the nuclear profile exhibits a narrower width than the other two dyes. Furthermore, TO-PRO3’s low binding specificity reflects higher intensities surrounding the nucleus (Fig. 3e). It may also contribute to its contribution to signal from non-biological debris on the tissue, for example, lab tissue paper fibers used to dry the fresh samples before imaging (see Supplementary Fig. S1b).

Extracellular matrix dye—Eosin Y 515

For cytoplasmic/ECM dye analysis, we followed the same analytical structure as the nuclear dyes, first analyzing the effects of solvent/rinsent, then concentration analysis, and finally comparing the best overall performance. However, we analyzed only one dye in this case, Eosin Y515. For the cytoplasmic/ECM dyes, we measured image contrast as the image quality parameter of interest rather than SNR.

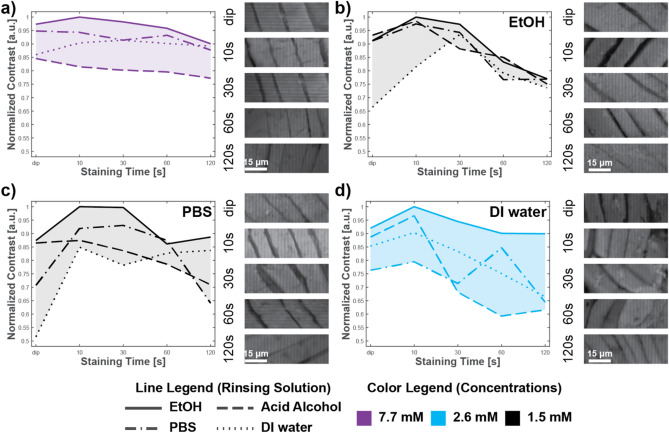

Figure 4 shows the effect of the rinsent type for each solvent type at the concentration at which image contrast reaches the maximal value. Image quality depended more on solvent/rinsent pair in ECM dyes than nuclear dyes. However, we can observe that ethanol as a rinsent provides the highest image contrast for each solvent and has the slightest variation with staining time. All other rinsents vary highly with other parameters (staining time, solvent) without making an observable trend. We also included images of skeletal muscle ROIs for the best rinsent and staining times for qualitative analysis.

Fig. 4.

Effects of rinsents on different Eosin Y 515 solvents. Effects of rinsent for each solvent in its peak image contrast intensity with skeletal muscle insets for different staining times for ethanol as a rinsent for following solvents of Eosin Y515 (a) none (stock solution), (b) ethanol, (c) PBS, and (d) deionized water.

Figure 5 shows the six different concentrations of EY that we used and the effects of solvent (color-coded) and rinsent (line-coded). For each concentration, we visualize one representative image of skeletal muscle for maximal image contrast for each solvent for qualitative comparison. Also, we normalized all contrasts to the highest measured image contrast in the experiment. In higher Eosin Y 515 concentrations (Fig. 5a–c), ethanol as solvent/rinsent slightly overperforms other solvents with ethanol as rinsent, and we observed maximal contrast. We never achieved maximal contrast for lower concentrations, but with increased staining time, all solvents improve performance, except DI water for 0.08 mM concentration. Moreover, we cannot determine the best solvent/rinsent pair for lower concentrations. We compare the best-performing solvents in Supplementary Fig. S2. In general, we find that solvent/rinsent pair and concentration have the largest effect on contrast, and care should be used in using high concentrations of eosin (which may contribute to overstaining that reduces contrast), and the choice of solvent used to dilute the eosin stock solution.

Fig. 5.

Measured image contrast for different Eosin Y 515 concentrations and staining protocols. Image contrast dependency on concentrations and staining times for ethanol (black), PBS (red), and DI water (blue) as a solvent and different rinsents. For each concentration, inlets with skeletal muscles image represent maximal image contrast for each solvent and concentration.

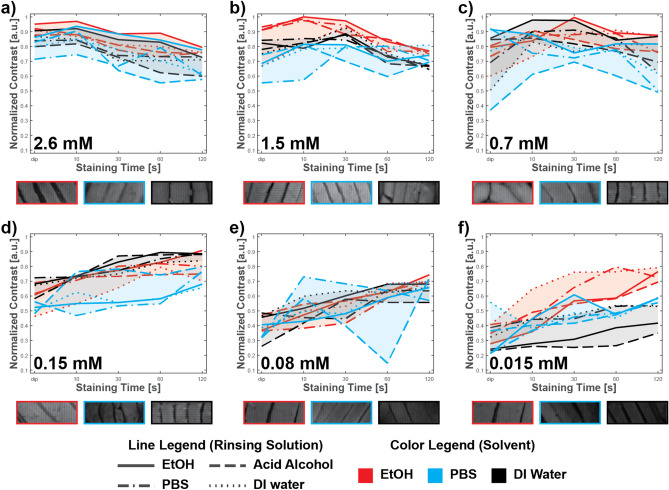

Temporal degradation and photobleaching

After determining the parameters for the staining procedure and fluorescent dye concentration that produces optimal image quality for each dye, we analyzed dyes in terms of temporal and photostability in fresh tissues after staining. To quantify the changes due to photobleaching, we measured the relative change of SNR for nuclear dyes, and contrast for ECM dye (Fig. 6a), during constant laser illumination. We observed high photostability of DRAQ5 and SYBR Gold (Fig. 6a,b,e), finding that image quality for both dyes loses less than 10% of its maximum, with DRAQ5 being the most stable overall. Upon closer inspection, both dyes demonstrate similar degradation until approximately 14 min of constant illumination. After that, the DRAQ5 signal continues to degrade almost linearly, whereas, for SYBR Gold, we see a sudden decrease in image quality starting at the 19th minute. Conversely, we can see that image intensity for TO-PRO3 drops more than 99% in the first 5 min of illumination. The total loss due to photobleaching for Eosin Y515 after 25 min of illumination is around 80% of the original image quality. For a visual representation of the changes in Fig. 6b, we show single nuclei for nuclei dyes and skeletal muscle images for ECM dyes at the beginning, middle, and end of the laser illumination. Qualitatively, in the case of photobleaching effects, visualization of the images acquired over time in Fig. 6e reflect the quantitative findings. We can show the relative effect of photobleaching on the images by comparing irradiated frames (upper left region of each image) with non-irradiated adjacent frames at the beginning and the end of experiment. The images demonstrate that SYBR Gold and DRAQ5 are very photostable over 25 min of constant laser illumination at typical imaging power levels, with very little difference in the images obtained between the beginning and end of the experiment, whereas TO-PRO3 is highly unstable, with most of the signal disappearing within 5 min of the experiment start point. The photobleaching performance of Eosin Y515 is between these cases, as we observe a significant drop in signal intensity after 25 min of imaging, but some signal remains at this point.

Fig. 6.

Temporal and photostability effects. Temporal stability of nuclei and ECM dye quality metrics for (a) photobleaching experiment (average ± one standard deviation of 10 ROI’s) with (b) nuclei and skeletal muscles images at start, middle, and end of constant illumination (note the end time of 5 min for TO-PRO3, compared to 25 min for the other dyes); (c) temporal degradation experiment (average ± one standard deviation of 10 ROI’s) with (d) nuclei and skeletal muscles images at 0, 12th, and 25th min of imaging; and (e) qualitative comparison of fluorescent dye signal of the photobleached frame (yellow dashed frame) and its adjacent non-irradiated frames immediately after staining and after 25 min of illumination for Eosin Y515, DRAQ5, and SYBR gold, and after 5 min for TO-PRO3. Light blue arrows show signal photobleaching in the close neighborhood of the illuminated frame due to the area of the illumination beam at the sample, which is larger than the camera field of view.

Whereas the photobleaching experiment tests dye stability for imaging protocols that require lengthy illumination of the same tissue area, the temporal degradation experiment tests the stability of the dye over time independent of illumination (for instance, due to environmental or tissue changes over time). For temporal degradation, we took 26 images intermittently over an experimental time of 25 min, but with a total laser illumination time of only 1.17 s (that is, we illuminated the tissue only during the intermittent imaging periods). In this experiment, we observed much smaller image quality degradation for all four dyes (Fig. 6c), with each dye retaining at least 92% of its initial image quality. In this experimental case, at the end of 25 min, we observed the lowest overall change for Eosin Y515 and the greatest for SYBR Gold. However, interestingly, SYBR gold shows the best stability (lowest rate of change) over shorter times, remaining the most stable and exceeding the others until approximately the 20th minute. TO-PRO3 shows the worst stability (highest rate of change) over time. Again, we observed slight variations in relative changes between ROIs. Figure 6d visualizes the image quality changes with temporal degradation when imaging starts, in the middle of the process, and at the process end. In general, users can expect the image quality of dyes to depreciate over time to greater or lesser degrees, and this should be taken into consideration when imaging times of fresh tissues are expected to be lengthy.

Comparing the photobleaching and temporal degradation measurements, we can see that the total photobleaching degradation of DRAQ5 and SYBR Gold is just a few percent larger than in the temporal degradation experiment, even though the exposure to laser illumination was 1282 times longer in the photobleaching experiment. These observations suggest that the signal degradation for these two dyes comes more from temporal changes (tissue changes in the ambient environment) rather than light exposure, further supporting the excellent photostability of these two dyes. On the other hand, Eosin Y515 and TO-PRO3 are more sensitive to total light exposure rather than changes over time. Furthermore, photobleaching results for DRAQ5 and TO-PRO3 aligns well with a previous study on live cells49.

Investigation of pan-species generalizability

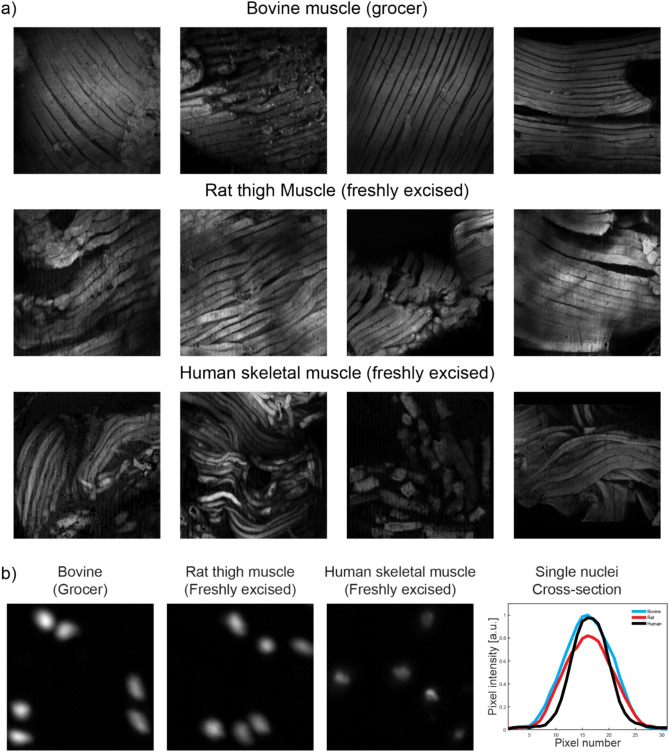

Fresh bovine muscle obtained from a grocer can be a good model for staining protocol studies as it is inexpensive, readily available, and contains a mix of skeletal muscle, adipose tissue, and connective tissue. However, the time between animal sacrifice and experimentation cannot be determined in this case, so the freshness of the tissue cannot be determined (although studies have shown high DNA stability in muscle tissue during food processing50,51, and we measured the pH of each sample used in our study which was consistent at 5.8 ± 0.3 over all samples). In addition, using one tissue type does not necessarily allow one to generalize to tissues from another animal species. To determine whether there would be any difference in the trends or conclusions drawn from the study performed on grocer bovine muscle with regards to freshness or species, we first obtained fresh rat thigh muscle tissue discarded from scheduled terminal experiments immediately after animal sacrifice, and tested a subset of the protocols for comparison of staining quality trends. We observed similar trends in both sample types, suggesting that the conclusions drawn for protocol optimization in bovine muscle obtained from a grocer would also apply to freshly excised rodent muscle tissues (Supplementary Fig. S3).

In addition, to further explore and demonstrate pan-species generalizability of our results, using our optimal protocol of SYBR Gold and Eosin as determined in this systematic study on bovine muscle, we imaged 45 surgically-resected prostates undergoing radical prostatectomy in a Tulane IRB-approved human study. In eight of those patient samples, skeletal muscles at the apex of the prostate appeared on the images, and we show examples of these in Fig. 7, along with examples of both skeletal muscle fibers and associated nuclei from grocer bovine muscle and freshly-excised rat thigh muscle for comparison. From the figure it is apparent that there is no observable difference in the quality of staining across species when comparing the same tissue type (i.e. skeletal muscle). In the human prostate samples, the measured contrast for eosin muscle fiber staining was 0.97 ± 0.1, and the measured SNR in the muscle cell nuclei was 122 ± 1.3 dB, which is exactly in line with our findings for optimal protocols in both grocer bovine muscle and fresh rat thigh muscle.

Fig. 7.

Pan-species comparison of optimal stain protocols on skeletal muscle images from grocer bovine tissue, freshly excised rat thigh muscle, and skeletal muscle at the apex of freshly excised human prostates, for (a) Eosin Y, and (b) SYBR gold.

Comparison of optimal staining parameters

In Table 1, we list the staining parameters, dye concentrations from which we observed peak image quality, and the US dollar price per milliliter of the final staining solution prepared using the optimal concentrations. The cheapest of all dyes is Eosin Y515. DRAQ5 is the most expensive dye we used in the experiment, but it is temporally stable and produces good-quality images, so is a good choice for small samples where high DNA specificity and stability is desired. The least expensive dye is SYBR Gold, which also showed high temporal stability and the highest image contrast in our study. However, this dye is excited in the visible blue spectrum and can be complex to combine with other fluorescent dyes in the same spectral space. Finally, TO-PRO3 is middle-priced but shows the worst image quality and temporal stability for fresh tissue imaging in this context. However, it has shown to be a valuable and robust marker in previous VP studies using fixed and/or cleared tissues, which were outside of the scope of the present study on fresh tissues.

Table 1.

Summary of staining parameters and dye concentration for measured highest image quality for each dye, including the US dollar per milliliter price for prepared solutions.

| Stain | Image quality | Staining parameters | PRICE [$/ml] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maximal contrast [a.u.] | Maximal SNR [dB] | Concentration [µM] | Staining time [s] | Solvent | Rinsing solution | ||

| Eosin Y515 | 0.98 | N/A | 1544 | 10 | EtOH | EtOH | 0.08 |

| DRAQ5 | N/A | 51.3 | 50 | 180 | PBS | PBS | 10 |

| TO-PRO3 | N/A | 49.3 | 50 | 180 | PBS | PBS | 4.3 |

| SYBR Gold | N/A | 54.6 | 124 | 180 | PBS | PBS | 0.9 |

Conclusion

In this paper, we quantitatively analyzed frequently used dyes in fluorescent virtual pathology by comparing image quality for varying staining protocols and their temporal and photo-stability. The goal was not to prescribe a perfect H&E analog, but to summarize how image quality depends on changing key parameters in tissue staining. For that purpose, we changed the dye concentration, solvent, rinsent, and illumination and imaging time and measured how they influenced image quality. We used SNR (for nuclear dyes) and intensity-normalized Michelson image contrast (for cytoplasmic/ECM dyes) as image quality measurements. We analyzed the four best-performing and most popular dyes in depth from a starting set of six dyes (two for ECM and four for nuclei).

First, we observed that the manufacturer-suggested solvent performed best across all dyes: ethanol for Eosin Y515 and PBS for the nuclear dyes. In addition, we found that using the manufacturer-suggested solvent as the rinsent was the best choice for image quality. Second, we observed that the solvent/rinsent combination effect on image SNR was independent of dye concentration in the nuclear channel but very influential in the ECM channel. Moreover, we used PBS and ethanol as both the solvent/rinsent, which provides the best image quality in nuclear and ECM channels, respectively. In other words, using the same chemical for dissolving and rinsing fluorescent dyes performs best because the rinsing process removes excess, unbound dye.

Dye concentrations and staining time are closely connected, and we observed a similar trend across dyes. The solutions with low dye concentrations showed rising imaging quality during the experiment without reaching the maximal value. For middle staining times, middle concentrations showed clear maximal image quality. The high dye concentration yields peak image quality during short staining times. We observed maximal image quality for nuclei dyes after 180 s of staining with 50 µM DRAQ5 and TOPRO-3 and 124 µM SYBR Gold, and after 10 s of staining with 1.5 mM of Eosin Y515.

Here, we should address a few limitations and aspects of our experimental setup. First, why did we set maximal staining times of 10 min, which resulted in not achieving maximal image quality for low dye concentrations? Second, why did the highest concentrations not perform the best? To answer the first limitation, we set our experiment to answer which concentration can provide value in a real-time imaging context, where staining times are limited, rather than when a specific concentration will reach the maximum. We did it that way because virtual pathology can replace histopathology in a point-of-care context only if it can provide real-time imaging, so tissue preparation must be quick. For the second question, there are two reasons why we do not measure the maximal peak for the highest concentration. First, staining time sampling at high concentrations may need to be more frequent than the times used in our study to measure the maximal peak. We can investigate this by adding more frequent imaging points during the staining procedure. Second, the diffusion gradients of binding of fluorescence dye to tissue molecules can vary between concentrations, which is out of the scope of this article. Finally, although VP can be performed with either continuous wave (CW) excitation or pulse wave (PW) excitation10,19,21,45,52–54, our results are produced using CW excitation and do not necessarily apply to short PW excitation (such as that used in multiphoton fluorescence) due to the different photophysics involved.

Although this work focused on dyes commonly used for dual-agent (nuclear + cytoplasm/ECM) staining to replicate H&E histopathology ex vivo, we recognize that other single-agent approaches (such as acriflavine and proflavine) can be potentially used ex vivo and in vivo. While we have used similar dyes (i.e. acridine orange) extensively in our prior work12–16, we chose to focus on dual-agent approaches in this work. We have found that acridine orange is a very stable, bright, inexpensive, and reliable single-channel agent, and prefer it when it is not necessary to isolate nuclear contrast from cytoplasmic/extracellular matrix contrast with high chemical specificity.

Temporal measurements are essential to identify the stability of the dyes during long-time imaging of large samples, such as surgical resections. For a temporal degradation study that depends more on environmental effects than on illumination time, which is the case in SIM virtual pathology of large specimens, we observed a relatively minor degradation of image quality over 25 min of imaging time. On the other hand, for photobleaching, we observed slight degradation in image quality of DRAQ5 and SYBR Gold, significant degradation in Eosin Y515 signal after 25 min of imaging, and total loss of signal with TO-PRO3 after five minutes of illumination. The 25 min upper limit studied here comes from a typical in-procedure timeframe for frozen section analysis or touch prep cytology, which are currently accepted forms of point-of-care pathology against which emerging VP methods will compete.

Finally, we saw that Eosin Y515 is the cheapest dye per milliliter, that DRAQ5 is ten times more expensive than SYBR Gold for similar SNR, and that TO-PRO3 lies between them. It is practical to consider dye price, performance, and experiment type before selecting a combination. In the example of DRAQ5 for the listed concentration in Table 1, if we image a small core needle biopsy sample for example, we would need a total volume of 200 µL, which makes the cost of one case $2. This is compared to, for example, imaging of an entire radical prostatectomy specimen as in our prior and current work, in which case for such large specimens we need a total volume of 50 mL, making the price per case of $500. Ultimately, the cost of the virtual pathology procedure, including the cost of staining agents, must be lower than or close to that of histopathology, if we want virtual pathology to become a viable replacement for histopathology. Our findings should inform users not only on technical aspects, but also economic aspects, of the choice and utilization of dyes for virtual pathology.

Methodology

Fluorescence dyes, staining protocol, and sample type

We designed a study to quantify image quality based on fluorescence dye choice and staining protocols. In this study, we analyzed two ECM and four nuclear fluorescence dyes. For ECM dyes we primarily focused on the frequently used Eosin Y515 (EY) (Leica). EY is a xanthene fluorescent dye that binds to compounds that contain positive charges and is the standard cytoplasmic/ECM dye in histology with quantum yield of 0.6755,56. In traditional brightfield histology, EY can differentiate cytoplasmic/ECM components based on variation in transmitted color and birefringence, and offers similar capabilities in VP based on emitted fluorescence intensity due to local concentration variations. Excitation and emission spectrum peaks for EY are 515 nm and 540 nm, respectively. We excited samples at 528 nm and used seven EY concentrations (Supplementary Table 1). We also tested Atto 488-NHS Ester (Sigma Aldrich) dissolved in PBS, a rhodamine based fluorescent dye with excellent water solubility which is frequently used in super-resolution microscopy, that exhibits a high fluorescence quantum yield (0.8)57. Excitation and emission peaks for Atto 488-NHS Ester are 488 nm and 523 nm, respectively. We used one concentration (Supplementary Table 1) and excited it with 470 nm laser light, but we did not continue with this dye due to low signal in our experimental setup.

For nuclear dyes, we used DRAQ5 (Biostatus, Ltd.), TO-PRO 3 (Biotium), SYBR Gold (Molecular Probes Inc.), and RedDot1 (Biotium). DRAQ5 and TO-PRO 3 are far-red fluorescent dyes that are easy to spectrally combine with other visible-range fluorophores. Their excitation and emission spectra are 647 nm/681 nm and 642 nm/661 nm, respectively. Even though TO-PRO3 has a higher quantum yield (~ 0.11)58 than DRAQ5 (~ 0.003–0.004)59, DRAQ5 binding to DNA is more specific, resulting in very high DNA labeling ratios for DRAQ5 which effectively increases signal during staining. RedDot1 is another far-red fluorescent dye for nuclear staining, with excitation and emission peaks at 662 nm and 694 nm, respectively. We excited all three dyes at 640 nm wavelength, and we used four concentrations for DRAQ5, three concentrations for TO-PRO3, and one concentration for RedDot1 (Supplementary Table 1). SYBR Gold is a green fluorescent dye that also labels DNA with a relatively high quantum yield (~ 0.660 or 0.761) and specific binding to DNA. Its excitation and emission peaks are 495 nm and 537 nm, respectively. We excited SYBR Gold with 470 nm light and used five different concentrations. We matched DRAQ5 and TO-PRO3 dilution concentration and kept same dilution ratio between DRAQ5 and SYBR Gold. SYBR Gold concentration was calculated based on recently reported stock concentrations (since the manufacturer provides the concentration as a dilution factor rather than a concentration)62.

We used the manufacturer-proposed solvent for all tested fluorescence dyes, namely ethanol or phosphate buffered saline (PBS). For EY, we also used deionized (DI) water as a solvent. Furthermore, EY is the only dye that we used in its manufacturer-provided stock concentration, since it is commonly provided in large-volume “ready-to-use” solutions for histopathology staining. We included rinsing steps in all staining procedures; referred to as “rinsent” in this text. We tested ethanol, PBS, and deionized water as the rinsent for all dyes except Atto 488-NHS Ester and RedDot1, for which we only used their solvent PBS. Further, we used acidic ethanol as a rinsent for EY only.

We used only one staining time for Atto and RedDot1, four staining times for the nuclear fluorescent dyes (DRAQ5, TO-PRO3, and SYBR Gold); and five staining times for EY (Supplementary Table 1). The staining procedure was cumulative to staining times to assess the effect of staining time on image quality. After selecting a concentration and solvent for a particular dye, we stained the sample for the shortest time listed in Supplementary Table 1, used a quick dip in rinsent to remove excess dye, and imaged it. After image capture, we continued the cumulative staining and imaging process by exposing the sample to dye for a time equal to the difference between the next staining time and the current time in the table, until we stained and imaged the tissue for the longest staining time in the table. At that point, we discarded the sample and prepared a fresh set of dyes. We did not observe a significant difference between our cumulative staining protocol with intermittent rinsing, and single staining and rinsing step per concentration and staining time (Supplementary Fig. S4).

We used only one concentration for Atto 488 and RedDot1 because the measured image quality was deficient compared to other dyes at the highest tested concentration (Supplementary Fig. S1). These dyes did not show improvement with longer staining times in our experimental setup. We concluded that more concentrated solutions would not perform well enough to justify additional resources.

In this systematic study, we used square tiles (1 × 1 × ~ 0.75 cm) of fresh bovine muscle obtained from a local grocer (sample pH value measured at the beginning of the experiment was 5.8 ± 0.3) as a sample. Bovine muscle represents a good model because it has both skeletal muscles and fat tissue and is readily available in fresh form. To standardize tile dimension and location between imaging sessions, we designed and 3D printed a slide holder, sample holder, a sample cutter (similar in concept to a biopsy punch) that cut the tissue in 1 × 1 cm tiles using blades, and a sample compressor (Supplementary Fig. S5a). To test the generalizability of the results, we performed a smaller scale protocol study in rat thigh muscle tissue obtained from four animals that were set to be discarded after sacrifice under an approved Tulane IACUC protocol (the animals were not sacrificed for the purposes of this study). Finally, we used the optimal SYBR gold and eosin protocols in fresh human prostates obtained immediately after surgical removal from patients providing informed consent under a Tulane approved Institutional Review Board protocol. All procedures were conducted in accordance with the guidelines and regulations set forth by the Tulane University IACUC and Biomedical IRB committees.

Imaging system and image acquisition and analysis

For data acquisition, we used a custom-built SIM system (Supplementary Fig. S5b). Light from a multi-wavelength laser diode light source (LDI 6, 89 North/Chroma) was collimated (Thorlabs), expanded (Thorlabs), and transmitted through a polarizing beam splitter (Moxtek). The polarized beam splitter is used to keep s-polarized light. The light beam was then reflected off of a liquid crystal on silicon spatial light modulator (SLM) (3DM.M249, Forth Dimension Displays), which was positioned in a conjugate plane to the sample. We implemented a square pattern on the SLM with a spatial frequency of 4 lp/mm. The illumination light was reflected by the same polarizing beam splitter, relayed through a tube lens and a custom multiband filter cube (ZET405/470/530/640rpc-UF1, Chroma). Excitation filter F1 and emission filter F2 are ZET405/470/530/640×, Chroma and ZET405/470/530/640×, Chroma, respectively, and then patterns were imaged onto the sample using an imaging objective lens (Plan Apo λ 10 × 0.45 NA, Nikon). Sample images were relayed to the camera through the objective lens and imaging tube lens (Nikon) and recorded using a 2048 × 2048 pixel sCMOS camera (Orca Flash 4.0 v2, Hamamatsu). Our system, with this objective lens, achieves a Nyquist-limited lateral resolution of 1.3 µm with a single-frame field of view of 1.3 mm × 1.3 mm. We used three laser lines from the multi-wavelength light source: 470 nm, 528 nm, and 640 nm. Supplementary Figure S6 provides power measurements at the sample in mW/cm2 for the full range of laser driver levels collected over multiple days (laser driver levels given as a percentage of maximum driver power).

Images were acquired using custom-built software (LabVIEW, National Instruments) and reconstructed using a custom-built application (MATLAB, Mathworks). Images were acquired in two modes, spatial and temporal. In spatial mode we imaged the whole sample area by serpentine scanning, taking 16 × 16 tiles (with each tile representing 2048 × 2048 pixels). After reconstruction, tiles were stitched using the ImageJ Grid/Collection stitching plugin (NIH)63. The spatial mode data were used for image quality analysis of the dyes and staining protocols. The temporal mode, where samples were imaged over time with varying illumination conditions, was used only for the photobleaching and temporal degradation studies. To quantify image quality, we used intensity-normalized Michelson image contrast for ECM dye and signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) for nuclear dyes. Furthermore, we used segmented nuclei from isoline contour plots of the nuclear images to emphasize intensity distribution across nuclei for different staining times. We imaged one sample for each dye concentration, solvent, and rinsent combination through every staining time. Those images were mutually registered using ImageJ (NIH), and ten regions of interest (ROI) were segmented from each tile. Each ROI was 1 × 1 mm square for ECM dye and 0.1 × 0.1 mm for nuclei dyes. We measured image contrast or SNR Eq. (1) in each ROI, and the final value for each tile was computed as the arithmetic means of image contrast or SNR in all 10 ROIs.

| 1 |

Photobleaching and temporal degradation

Fluorescent virtual pathology imaging of very large samples (e.g., tumor resection specimens)12,15 can take 20–30 min, and staining stability will be necessary. To test dye stability, we analyzed it in terms of both temporal degradation and photobleaching. The first experiment, temporal degradation, was designed to test the stability of the dye signal over time in the stained tissue without constant laser illumination. Conversely, the second experiment, photobleaching, was designed to explicitly test the dyes’ photostability in the stained tissue under constant laser illumination. Thus, photobleaching will be more influential in samples illuminated for extended periods or with high laser intensity, such as in 3D imaging (3D confocal imaging, LSM), compared to light-efficient large area 2D imaging (SIM), in which samples are exposed to short illumination times in any particular sample region but total imaging time is long, and therefore effects due to temporal degradation are expected to dominate. Photobleaching effects and temporal staining degradation were tested for every fluorescent dye except Atto 488 and RedDot1 in the experimental setup. Those two dyes were excluded due to low image quality performance in the experiment. We quantified photobleaching and temporal degradation for each dye's optimal combination of staining parameters, using fresh samples stained for this purpose only. In both experiments, we imaged one tile (2048 × 2048 pixels) every 60 s up to 25 min after staining.

Additionally, for the photobleaching experiment, we acquired three adjacent non-irradiated neighborhood tiles immediately after staining and after 25 min for qualitative analysis of photobleaching effects. We defined 25 min as an upper border as the maximal desirable time for imaging a sizeable fresh specimen at the point of care. The only difference between the two experiments is that in the case of the photobleaching experiment, we kept the laser light on during the whole experiment time (i.e., 25 min). However, in the temporal degradation experiment, we illuminated the sample only during image acquisition, which occurred every 60 s. We did not change laser power during experiments, and laser power was qualitatively adjusted between experiments to produce the best image quality immediately after staining. After image acquisition, we performed image analysis as explained above on five ROIs of 0.2 × 0.2 mm.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Carolyn Bayer, Allan Alencar, Lili Shi, and Kenneth Swan for assistance with the rat study. Financial support for this work was provided by a grant from the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health, number R01 CA222831. This content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Author contributions

I.B. designed the study, collected data, performed data analysis, and wrote and edited the manuscript; M.R.B prepared staining solutions; J.Q.B supervised the work, provided funding, and edited the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Data availability

Selected ROIs are available at https://osf.io/cn9ej/?view_only=1f458a37a0fb4dcb8eb055b217ce590a, raw data are available per request to contact author.

Competing interests

J.Q.B. is listed as an inventor on a patent related to the imaging system described in this paper, which has been licensed to Instapath, Inc. J.Q.B. is a co-founder of Instapath, Inc. and holds stock in the company. M.R.B and I.B do not have any competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-72213-5.

References

- 1.Rivenson, Y. et al. Virtual histological staining of unlabelled tissue-autofluorescence images via deep learning. Nat. Biomed. Eng.3, 466–477. 10.1038/s41551-019-0362-y (2019). 10.1038/s41551-019-0362-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nguyen, F. T. et al. Intraoperative evaluation of breast tumor margins with optical coherence tomography. Cancer Res.69, 8790–8796. 10.1158/0008-5472.Can-08-4340 (2009). 10.1158/0008-5472.Can-08-4340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cao, R. et al. Label-free intraoperative histology of bone tissue via deep-learning-assisted ultraviolet photoacoustic microscopy. Nat. Biomed. Eng.10.1038/s41551-022-00940-z (2022). 10.1038/s41551-022-00940-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abraham, T. M., Costa, P. C., Filan, C., Robles, F. & Levenson, R. Mode-mapping qOBM microscopy to virtual hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) histology via deep learning. In Unconventional Optical Imaging III 203–210 (SPIE, 2022). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Campagnola, P. J. & Loew, L. M. Second-harmonic imaging microscopy for visualizing biomolecular arrays in cells, tissues and organisms. Nat. Biotechnol.21, 1356–1360. 10.1038/nbt894 (2003). 10.1038/nbt894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stanciu, S. G. et al. Super-resolution re-scan second harmonic generation microscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.119, e2214662119. 10.1073/pnas.2214662119 (2022). 10.1073/pnas.2214662119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blokker, M., Hamer, P. C. D. W., Wesseling, P., Groot, M. L. & Veta, M. Fast intraoperative histology-based diagnosis of gliomas with third harmonic generation microscopy and deep learning. Sci. Rep.12, 11334. 10.1038/s41598-022-15423-z (2022). 10.1038/s41598-022-15423-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weinigel, M. et al. In vivo histology: optical biopsies with chemical contrast using clinical multiphoton/coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering tomography. Laser Phys. Lett.11, 055601. 10.1088/1612-2011/11/5/055601 (2014). 10.1088/1612-2011/11/5/055601 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu, Z. et al. Instant diagnosis of gastroscopic biopsy via deep-learned single-shot femtosecond stimulated Raman histology. Nat. Commun.13, 4050. 10.1038/s41467-022-31339-8 (2022). 10.1038/s41467-022-31339-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yoshitake, T. et al. Direct comparison between confocal and multiphoton microscopy for rapid histopathological evaluation of unfixed human breast tissue. J. Biomed. Opt.21, 126021–126021. 10.1117/1.JBO.21.12.126021 (2016). 10.1117/1.JBO.21.12.126021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elfer, K. N. et al. DRAQ5 and Eosin (‘D&E’) as an analog to hematoxylin and eosin for rapid fluorescence histology of fresh tissues. PLoS One11, e0165530. 10.1371/journal.pone.0165530 (2016). 10.1371/journal.pone.0165530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Luethy, S., Tulman, D. B. & Brown, J. Q. Automated gigapixel circumferential surface microscopy of the prostate. Sci. Rep.10, 131. 10.1038/s41598-019-56939-1 (2020). 10.1038/s41598-019-56939-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schlichenmeyer, T. C., Wang, M., Elfer, K. N. & Brown, J. Q. Video-rate structured illumination microscopy for high-throughput imaging of large tissue areas. Biomed. Opt. Express5, 366–377. 10.1364/BOE.5.000366 (2014). 10.1364/BOE.5.000366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang, M. et al. High-resolution rapid diagnostic imaging of whole prostate biopsies using video-rate fluorescence structured illumination microscopy. Cancer Res.75, 4032–4041. 10.1158/0008-5472.Can-14-3806 (2015). 10.1158/0008-5472.Can-14-3806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang, M. et al. Gigapixel surface imaging of radical prostatectomy specimens for comprehensive detection of cancer-positive surgical margins using structured illumination microscopy. Sci. Rep.6, 27419. 10.1038/srep27419 (2016). 10.1038/srep27419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang, M. et al. Partial nephrectomy margin imaging using structured illumination microscopy. J. Biophotonics11, e201600328. 10.1002/jbio.201600328 (2018). 10.1002/jbio.201600328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang, Y., Kang, L., Lo, C. T. K., Tsang, V. T. C. & Wong, T. T. W. Rapid slide-free and non-destructive histological imaging using wide-field optical-sectioning microscopy. Biomed. Opt. Express13, 2782–2796. 10.1364/BOE.454501 (2022). 10.1364/BOE.454501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reder, N. P. et al. Open-top light-sheet microscopy image atlas of prostate core needle biopsies. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med.143, 1069–1075. 10.5858/arpa.2018-0466-OA (2019). 10.5858/arpa.2018-0466-OA [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Giacomelli, M. G. et al. Multiscale nonlinear microscopy and widefield white light imaging enables rapid histological imaging of surgical specimen margins. Biomed. Opt. Express9, 2457–2475. 10.1364/BOE.9.002457 (2018). 10.1364/BOE.9.002457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Giacomelli, M. G. et al. Virtual hematoxylin and eosin transillumination microscopy using epi-fluorescence imaging. PLoS One11, e0159337. 10.1371/journal.pone.0159337 (2016). 10.1371/journal.pone.0159337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cahill, L. C. et al. Comparing histologic evaluation of prostate tissue using nonlinear microscopy and paraffin H&E: A pilot study. Mod. Pathol.32, 1158–1167. 10.1038/s41379-019-0250-8 (2019). 10.1038/s41379-019-0250-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fereidouni, F. et al. Microscopy with ultraviolet surface excitation for rapid slide-free histology. Nat. Biomed. Eng.1, 957–966. 10.1038/s41551-017-0165-y (2017). 10.1038/s41551-017-0165-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karadaglić, D. & Wilson, T. Image formation in structured illumination wide-field fluorescence microscopy. Micron39, 808–818. 10.1016/j.micron.2008.01.017 (2008). 10.1016/j.micron.2008.01.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jain, M., Rajadhyaksha, M. & Nehal, K. Implementation of fluorescence confocal mosaicking microscopy by “early adopter” Mohs surgeons and dermatologists: Recent progress. J. Biomed. Opt.22, 024002 (2017). 10.1117/1.JBO.22.2.024002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gareau, D. Feasibility of digitally stained multimodal confocal mosaics to simulate histopathology. J. Biomed. Opt.14, 034050 (2009). 10.1117/1.3149853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yoshitake, T. et al. Rapid histopathological imaging of skin and breast cancer surgical specimens using immersion microscopy with ultraviolet surface excitation. Sci. Rep.8, 4476. 10.1038/s41598-018-22264-2 (2018). 10.1038/s41598-018-22264-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen, Y. et al. Rapid pathology of lumpectomy margins with open-top light-sheet (OTLS) microscopy. Biomed. Opt. Express10, 1257–1272. 10.1364/BOE.10.001257 (2019). 10.1364/BOE.10.001257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee, M. Y. et al. Fluorescent labeling of abundant reactive entities (FLARE) for cleared-tissue and super-resolution microscopy. Nat. Protoc.17, 819–846. 10.1038/s41596-021-00667-2 (2022). 10.1038/s41596-021-00667-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Qorbani, A. et al. Microscopy with ultraviolet surface excitation (MUSE): A novel approach to real-time inexpensive slide-free dermatopathology. J. Cutan. Pathol.45, 498–503. 10.1111/cup.13255 (2018). 10.1111/cup.13255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ching-Roa, V. D., Huang, C. Z., Ibrahim, S. F., Smoller, B. R. & Giacomelli, M. G. Real-time analysis of skin biopsy specimens with 2-photon fluorescence microscopy. JAMA Dermatol.158, 1175–1182. 10.1001/jamadermatol.2022.3628 (2022). 10.1001/jamadermatol.2022.3628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Molnár, E. et al. Combination of small molecule microarray and confocal microscopy techniques for live cell staining fluorescent dye discovery. Molecules18, 9999–10013 (2013). 10.3390/molecules18089999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tanbakuchi, A. A., Udovich, J. A., Rouse, A. R., Hatch, K. D. & Gmitro, A. F. In vivo imaging of ovarian tissue using a novel confocal microlaparoscope. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol.202(90), e91-90.e99. 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.07.027 (2010). 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.07.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cordova, R. et al. Sub-millimeter endoscope demonstrates feasibility of in vivo reflectance imaging, fluorescence imaging, and cell collection in the fallopian tubes. J. Biomed. Opt.26, 076001 (2021). 10.1117/1.JBO.26.7.076001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Forcucci, A., Pawlowski, M. E., Majors, C., Richards-Kortum, R. & Tkaczyk, T. S. All-plastic, miniature, digital fluorescence microscope for three part white blood cell differential measurements at the point of care. Biomed. Opt. Express6, 4433–4446. 10.1364/BOE.6.004433 (2015). 10.1364/BOE.6.004433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fuchs, F. S. et al. Confocal laser endomicroscopy for diagnosing lung cancer in vivo. Eur. Respir. J.41, 1401–1408. 10.1183/09031936.00062512 (2013). 10.1183/09031936.00062512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kiesslich, R. et al. Confocal laser endoscopy for diagnosing intraepithelial neoplasias and colorectal cancer in vivo. Gastroenterology127, 706–713. 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.06.050 (2004). 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.06.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li, C. Q. et al. Effects on confocal laser endomicroscopy image quality by different acriflavine concentrations. J. Interv. Gastroenterol.1, 59–63. 10.4161/jig.1.2.16828 (2011). 10.4161/jig.1.2.16828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Polglase, A. L. et al. A fluorescence confocal endomicroscope for in vivo microscopy of the upper- and the lower-GI tract. Gastrointest. Endosc.62, 686–695. 10.1016/j.gie.2005.05.021 (2005). 10.1016/j.gie.2005.05.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leong, R. W. et al. In vivo confocal endomicroscopy in the diagnosis and evaluation of celiac disease. Gastroenterology135, 1870–1876. 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.08.054 (2008). 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.08.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grant, B. D. et al. High-resolution microendoscopy: A point-of-care diagnostic for cervical dysplasia in low-resource settings. Eur. J. Cancer Prev.26, 63–70. 10.1097/cej.0000000000000219 (2017). 10.1097/cej.0000000000000219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pierce, M. C. et al. Accuracy of in vivo multimodal optical imaging for detection of oral neoplasia. Cancer Prev. Res.5, 801–809. 10.1158/1940-6207.Capr-11-0555 (2012). 10.1158/1940-6207.Capr-11-0555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Protano, M. A. et al. Low-cost high-resolution microendoscopy for the detection of esophageal squamous cell neoplasia: An international trial. Gastroenterology149, 321–329. 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.04.055 (2015). 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.04.055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Martirosyan, N. L. et al. Use of in vivo near-infrared laser confocal endomicroscopy with indocyanine green to detect the boundary of infiltrative tumor: Laboratory investigation. J. Neurosurg.115, 1131–1138. 10.3171/2011.8.JNS11559 (2011). 10.3171/2011.8.JNS11559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Elfer, K., Sholl, A. & Brown, J. Q. Biomedical Optics 2016 (Optica Publishing Group, 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cahill, L. C. et al. Rapid virtual hematoxylin and eosin histology of breast tissue specimens using a compact fluorescence nonlinear microscope. Lab. Investig.98, 150–160. 10.1038/labinvest.2017.116 (2018). 10.1038/labinvest.2017.116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Barner, L. et al. Multiresolution nondestructive 3D pathology of whole lymph nodes for breast cancer staging. J. Biomed. Opt.27, 036501 (2022). 10.1117/1.JBO.27.3.036501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Glaser, A. K. et al. Multidirectional digital scanned light-sheet microscopy enables uniform fluorescence excitation and contrast-enhanced imaging. Sci. Rep.8, 13878. 10.1038/s41598-018-32367-5 (2018). 10.1038/s41598-018-32367-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Glaser, A. K. et al. Light-sheet microscopy for slide-free non-destructive pathology of large clinical specimens. Nat. Biomed. Eng.1, 0084. 10.1038/s41551-017-0084 (2017). 10.1038/s41551-017-0084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Martin, R. M., Leonhardt, H. & Cardoso, M. C. DNA labeling in living cells. Cytom. Part A67A, 45–52. 10.1002/cyto.a.20172 (2005). 10.1002/cyto.a.20172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Musto, M. DNA quality and integrity of nuclear and mitochondrial sequences from beef meat as affected by different cooking methods. Food Technol. Biotechnol.49, 523–528 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bahar, B. et al. Long-term stability of RNA in post-mortem bovine skeletal muscle, liver and subcutaneous adipose tissues. BMC Mol. Biol.8, 108. 10.1186/1471-2199-8-108 (2007). 10.1186/1471-2199-8-108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hristu, R. et al. Assessment of extramammary paget disease by two-photon microscopy. Front. Med.9, 839786. 10.3389/fmed.2022.839786 (2022). 10.3389/fmed.2022.839786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Olson, E., Levene, M. J. & Torres, R. Multiphoton microscopy with clearing for three dimensional histology of kidney biopsies. Biomed. Opt. Express7, 3089–3096. 10.1364/BOE.7.003089 (2016). 10.1364/BOE.7.003089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vesuna, S., Torres, R. & Levene, M. J. Multiphoton fluorescence, second harmonic generation, and fluorescence lifetime imaging of whole cleared mouse organs. J. Biomed. Opt.16, 106009. 10.1117/1.3641992 (2011). 10.1117/1.3641992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Penzkofer, A., Beidoun, A. & Daiber, M. Intersystem-crossing and excited-state absorption in eosin Y solutions determined by picosecond double pulse transient absorption measurements. J. Lumin.51, 297–314. 10.1016/0022-2313(92)90059-I (1992). 10.1016/0022-2313(92)90059-I [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Daly, S. et al. The gas-phase photophysics of eosin Y and its maleimide conjugate. J. Phys. Chem. A120, 3484–3490. 10.1021/acs.jpca.6b01075 (2016). 10.1021/acs.jpca.6b01075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.GmbH AT. https://www.atto-tec.com/fluorescence/determination-of-fluorescence-quantum-yield/?language=en Accessed on 24 August 2024.

- 58.Lakowicz, J. R., Piszczek, G. & Kang, J. S. On the possibility of long-wavelength long-lifetime high-quantum-yield luminophores. Anal. Biochem.288, 62–75. 10.1006/abio.2000.4860 (2001). 10.1006/abio.2000.4860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Njoh, K. L. et al. Spectral analysis of the DNA targeting bisalkylaminoanthraquinone DRAQ5 in intact living cells. Cytom. Part A69A, 805–814. 10.1002/cyto.a.20308 (2006). 10.1002/cyto.a.20308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Invitrogen, SYBR® Gold Nucleic Acid Gel Stain. https://assets.thermofisher.com/TFS-Assets/LSG/manuals/mp11494.pdf Accessed on 24 August 2024.

- 61.Tuma, R. S. et al. Characterization of SYBR gold nucleic acid gel stain: A dye optimized for use with 300 nm ultraviolet transilluminators. Anal. Biochem.268, 278–288. 10.1006/abio.1998.3067 (1999). 10.1006/abio.1998.3067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kolbeck, P. J. et al. Molecular structure, DNA binding mode, photophysical properties and recommendations for use of SYBR gold. Nucleic Acids Res.49, 5143–5158. 10.1093/nar/gkab265 (2021). 10.1093/nar/gkab265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Preibisch, S., Saalfeld, S. & Tomancak, P. Globally optimal stitching of tiled 3D microscopic image acquisitions. Bioinformatics25, 1463–1465. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp184 (2009). 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Selected ROIs are available at https://osf.io/cn9ej/?view_only=1f458a37a0fb4dcb8eb055b217ce590a, raw data are available per request to contact author.