Abstract

The Coat Protein I (COPI) complex forms vesicles from Golgi membrane for retrograde transport among the Golgi stacks, and also from the Golgi to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). We have been elucidating the mechanistic details of COPI vesicle formation through a reconstitution system that involves the incubation of Golgi membrane with purified components. This approach has enabled us recently to gain new insight into how certain lipids are critical for the fission stage of COPI vesicle formation. Lipid geometry has been proposed to act in the formation of transport carriers by promoting membrane curvature. However, evidence for this role has come from studies using simplified membranes, while confirmation in the more physiologic setting of native membranes has been challenging, as such membranes contain a complex composition of lipids and proteins. We have recently refined the COPI reconstitution system to overcome this experimental obstacle. This has led us to identify an unanticipated type of lipid geometry needed for COPI vesicle fission. This chapter describes the approach that we have developed to enable this discovery. The methodologies include: (i) preparation Golgi membrane from cells that are deficient in a particular lipid enzyme activity, and (ii) functional rescue of this deficiency by introducing the product of the lipid enzyme, with experiments being performed at the in vitro level to gain mechanistic clarity and at the in vivo level to confirm physiologic relevance.

Keywords: COPI, Golgi complex, Lipid geometry, Vesicle fission

1. Introduction

How proteins can bend membrane to drive carrier formation has been extensively characterized, but how lipids can also act in this manner has been less studied. Lipid geometry has been proposed to enable certain lipids to promote membrane deformation, which has been postulated to involve the relative space occupied by the headgroup versus that by the acyl chains of a lipid. When a greater space is occupied by the acyl chains, a cone geometry is promoted. When a greater space is occupied by the headgroup, an inverted-cone geometry is promoted. In the context of vesicle formation, inverted-cone geometry in the cytosolic leaflet is predicted to promote the budding stage, while cone geometry is predicted to promote the fission stage [1, 2]. Although this mechanistic paradigm has been supported by studies that use simplified membranes [3], validating this mechanism in the context of native membranes has been challenging, due to their complex composition that makes direct versus indirect effects difficult to distinguish.

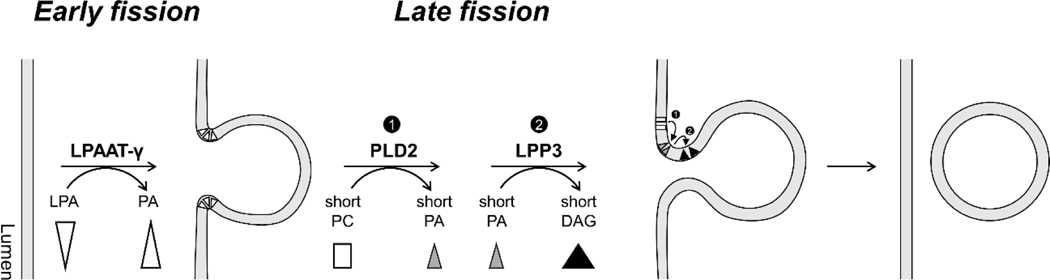

We have recently established an approach to overcome this experimental obstacle. A reconstitution system that involves the incubation of Golgi membrane with purified components, which when coupled with electron microscopy, has enabled COPI vesicle formation to be studied in mechanistic detail [4–9]. Advancing the understanding of how lipids can play a critical role in carrier formation, we have found in recent years that phosphatidic acid (PA) and diacylglycerol (DAG) are needed for the fission stage of COPI vesicle formation (Figure 1). For early fission, PA generated by lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) acyl transferase type gamma (LPAAT-γ, which converts LPA to PA) is needed [7]. For late fission, PA generated by phospholipase D type 2 (PLD2, which converts phosphatidylcholine to PA), followed by DAG generated by lipid phosphate phosphatase type 3 (LPP3, which converts PA to DAG) are needed [9]. To further elucidate how these lipids are needed, we have recently incorporated a functional lipid rescue approach to the COPI vesicle reconstitution system, which allows us to assess whether the geometry of these lipids affects their roles [9].

Figure 1. The role of different lipid geomentry in regulating COPI vesicle formtion.

Critical lipids needed for the fission stage of COPI vesicle formation.

Early fission requires lysophosphatidic acid acyltransferase type gamma (LPAAT-γ), which converts lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) to phosphatidic acid (PA). Lipid rescue experiments reveal that the geometry of PA is not critical for this stage. Late fission requires the sequential actions of two lipid enzymes: phospholipase D type 2 (PLD2) which converts phosphatidylcholine (PC) to PA, and lipid phosphate phosphatase type 3 (LPP3) which converts the PA to diacylglycerol (DAG). Lipid rescue experimens reveal that the critical roles of PA and DAG at this stage require these lipids having short acyl chains (less than 14 carbons on each chain).

The major steps of this approach are as follows. We initially treat cells with siRNA against a particular lipid enzyme of interest (LPAAT-γ, PLD2, or LPP3). Golgi membranes are then collected from these cells. We then incubate the Golgi membrane deficient in a particular lipid enzyme with purified protein factors. The Golgi membrane is then examined by electron microscopy to discern the stage of vesicle formation that has been arrested. We then perform functional rescue of this arrest by introducing the product of the lipid enzyme. By introducing the product having various lipid geometries, we are able to identify the needed for lipids to adopt a specific geometry in supporting COPI vesicle formation.

Taking this approach, we have recently found that early fission in COPI vesicle formation is not particularly sensitive to the lipid geometry of PA, as PA having fully saturated acyl chains (which promotes an inverted-cone geometry of PA), having single cis-unsaturation in both acyl chains (which promotes a cone geometry of PA), or having shorter acyl chains can all rescue the block in early fission exerted by targeting against LPPAT-γ. In contrast, late fission is sensitive to the length of acyl chains. Specifically, blocking late fission by targeting against PLD2 activity is rescued by PA having short acyl chains, while blocking the subsequent stage of late fission by targeting against LPP3 is rescued by DAG having short acyl chains [9]. Thus, the late stage of COPI vesicle fission requires a type of lipid geometry that involves shorter acyl chains, rather than the cone geometry that had been predicted based on studies on simpler membranes (Figure 1).

Complementing these procedures, we also pursue two additional approaches. One approach examines whether a particular geometry of a lipid promotes the ability of a COPI protein factor to induce membrane fission. For this goal, we generate liposomes having a composition of major lipids mimicking those of the Golgi membrane, and also adding a lipid of interest (PA or DAG) in its various forms to achieve cone, inverted-cone, or shortened geometry. We then incubate the resulting liposome with COPI-related factors followed by EM examination to assess membrane fission. The results from these studies have provided a more detailed understanding of how the lipid geometry of PA/DAG cooperates with a particular protein factor to achieve COPI vesicle fission [9].

Another approach involves the cell-based COPI transport assay, which seeks to confirm the physiologic relevance of findings derived from the in vitro studies described above. This assay tracks the transport of a COPI cargo, a chimeric protein known as VSVG-KDELR, from the Golgi to the ER. Cells are treated with siRNA against a particular lipid enzyme of interest (LPAAT-γ, PLD2, or LPP3) to inhibit COPI transport. Functional rescue is then performed by feeding cells with the product of the lipid enzyme having been targeted by the siRNA treatment. This involves feeding the lipid product having varying geometries that include cone, inverted-cone, or shortened form, and then identifying those that can rescue the inhibition in transport [9].

The detailed methodologies of these approaches are described below.

2. Materials

2.1. Golgi membrane preparation

HeLa cells (ATCC).

Cell culture media: DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 20 mM HEPES, and 20 μg/ml gentamicin.

Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (Invitrogen, 13778075).

siRNA : LPAAT-γ (5’-GAGACCAAGCACCGCGUUA-3’), PLD2 (5’-GGACAACCAAGAAGAAAUA-3’), and LPP3 (5’-GGGACUGUCUCGCGUAUCA-3’)

ST buffer: dissolve 856 mg sucrose in 10 ml Tris-HCl, pH 7.4.

Sucrose gradient solutions: 62% (804.9 mg sucrose in 1 ml 10mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4), 35% (403 mg sucrose in 1 ml 10mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4), and 29% (325.4 mg sucrose in 1 ml 10mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4).

Refractometer (Bausch & Lomb).

30 ml syringe, 10 ml syringe.

Blunt tip needle (Sigma Aldrich, Z261394).

Ball-bearing homogenizer and 22 μm clearance ball (Isobiotech).

50 ml ultracentrifuge tubes for SW-28 rotor (Beckman).

2.2. In vitro COPI vesicle formation

Siliconized microcentrifuge tubes (Eppendorf, 022431081) and tips (Neptune, 2100), which reduce non-specific protein and membrane binding.

Traffic buffer: 25 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 50 mM KCl, 2.5 mM Mg(OAc)2, 1 mg/ml soybean trypsin inhibitor, 1 mg/ml BSA, and 200 mM sucrose.

3 M KCl washing solution: dissolve 224 mg KCl in 1ml traffic buffer.

Cushion buffer: dissolve 1.59 g sucrose in 10 ml traffic buffer.

Preparation of myristoylated ARF1, BARS, ARFGAP1, and COPI has been described previously [4, 5].

1 ml ultracentrifuge tubes for TLA120.2 rotor (Beckman).

2.3. Liposome preparation

Lipids were from Avanti Polar Lipids: 2C18:1 PC (DOPC, 850375), 2C10:0 PA (830843), 2C18:0 PA (830865), 2C18:1 PA (840875), 2C18:1 PE (DOPE, 850725), 2C18:1 PI (850149), 2C18:1 PS (DOPS, 840035), 2C10:0 DAG (800810), 2C16:0 DAG (800816), 2C18:1 DAG (800811), 2C18:0–22:6 DAG (800819), Sphingomyelin (860061), and Cholesterol (700000).

Mini-extruder (Avanti Polar lipid, 610023).

1000 μl syringe (Avanti Polar lipids, 610017).

400 nm filter membrane (Whatman, 800282).

10 mm filter supports (Avanti Polar lipids, 610014).

Reaction buffer 1: 25 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 50 mM KCl, 2.5 mM Mg(OAc)2, and 250 mM sucrose.

Reaction buffer 2: 25 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 50 mM KCl, and 2.5 mM Mg(OAc)2.

2.4. Electron microscopy

Carbon Film supported Copper Grid, 200 mesh (Electron microscopy sciences, CF200-CU).

2.5% uranyl acetate staining solution, pH 3.5.

JEOL JEM-1011 Transmission Electron Microscope.

2.5. In vivo COPI transport assay

HeLa cells (ATCC).

Culture media: DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 20 mM HEPES, and 20 μg/ml gentamicin.

Transfection reagents: GenJet (Signagen Laboratories), and Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (Invitrogen).

VSVG-ts045-KDELR in pROSE [10].

BSA (Thermo scientific).

Fixation solution: 4% PFA in PBS.

Antibody against VSVG (BW8G65) and Giantin (Abcam, ab80864).

Blocking buffer: 10% FBS, 0.04% NaN3 in PBS.

Antibody incubation buffer: 10% FBS, 0.04% NaN3, 0.05% saponin in PBS.

0.45 um syringe filter (Sartorius, 16555-K).

3. Methods

3.1. Golgi membrane preparation

Seed HeLa cells in 20 × 150 mm cell culture plates.

Transfect siRNA to cells using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX according to manufacturer’s protocol.

Incubate cells for 72 hr at 37°C.

Collect the cells using trypsin treatment, and then centrifuge at 450 × g for 10 min.

Resuspend the pellet using cold ST buffer (1 ml pellet for 10 ml ST buffer).

Centrifuge at 450 × g 10 min.

Repeat step 5–6, 3 times.

Homogenize the cells using ball-bearing homogenizer with 22 μm ball for 8 passes (see Note 1).

Centrifuge lysate at 1,800 × g for 10 min.

Mix 12 ml of supernatant with 11 ml of 62% sucrose buffer (see Note 2).

Prepare sucrose gradient. Place 9 ml of 29% sucrose buffer at the bottom of ultracentrifuge tubes.

Place 15 ml of 35% sucrose buffer from the bottom of tubes using syringe with blunt tip needle.

Place 12 ml of 37% cell homogenate (step 10) at the bottom of tube.

Centrifuge at 110,000 × g for 2.5 h.

Collect Golgi membrane at the 29%/35% sucrose interface using syringe with 18G needle.

Measure protein concentration and then store at −80°C until use (see Note 3).

3.2. Reconstituting COPI vesicle formation at an arrested state

Dilute the frozen Golgi membrane (50 μg per experimental condition) by adding 1 ml of traffic buffer (see Note 4).

Centrifuge at 16,000 × g for 30 min in 4°C.

Discard the supernatant.

Resuspend the membrane by pipetting up and down using 200 μl of 3 M KCl buffer and leave on ice/water for 5 min.

Add 1ml of traffic buffer, and gently invert 2–3 times.

Centrifuge at 16,000 × g for 30 min, 4°C.

Discard the supernatant.

Resuspend the pellet using 100 ul of traffic buffer.

Add COPI (6 μg/ml), ARF1(6 μg/ml), GTP (2 mM), and make up to 300 μl with traffic buffer.

Incubate at 37°C for 30 min.

Stop the reaction on ice/water for 5 min.

Place 20 μl of cushion buffer at the bottom of the tube (see Note 5).

Centrifuge at 16,000 × g for 30 min, 4°C.

Gently discard the supernatant.

Resuspend the pellet using 50 μl of traffic buffer.

Add ARFGAP1(6 μg/ml), BARS(3 μg/ml) and make up to 100 μl with traffic buffer.

Incubate at 37°C for 30 min.

Stop the reaction on ice/water for 5 min.

Place 20 μl of cushion buffer at the bottom of the tube.

Centrifuge at 16,000 × g for 30 min, 4°C.

Collect the supernatant containing reconstituted COPI vesicles.

Collect the pellet containing remaining Golgi membrane by resuspending with 100 μl of traffic buffer.

Examine reconstituted COPI vesicles by western blotting using anti-βCOP antibody.

3.3. Rescuing the arrest in COPI vesicle formation

Prepare pure liposomes using lipids (50:50 = DOPC:lipid of interest, molar ratio).

Dry the lipid mixture using nitrogen gas (see Note 6).

Resuspend the lipid films using 100 μl of reaction buffer 1 and hydrate at RT for 18 hr.

Dilute the mixture by adding 1 ml of reaction buffer 2.

Centrifuge at 16,000 x g for 15 min.

Discard the supernatant.

Resuspend the pellet using reaction buffer 2.

Extrude the liposome using 400 nm filter membrane in a mini-extruder (see Note 7).

Incubate the washed lipid enzyme depleted Golgi membrane (step 8 of section 3.2) with 200 μM lipids with desired liposomes for 10 min at 37°C. The purpose of this step is to provide short lipids to the Golgi membrane through the spontaneous fusion of liposomes with Golgi membrane.

Add 1 ml of traffic buffer and invert 2–3 times.

Centrifuge the mixture at 16,000 x g for 30 min at 4°C.

Discard the supernatant.

Resuspend the pellet using 100 μl of traffic buffer and follow step 9–23 of section 3.2.

3.4. Liposome deformation assay

Prepare 200 μg lipids in glass tube (see Table 1 for lipid composition).

Dry the lipid mixture using nitrogen gas.

Resuspend the lipids using 200 μl of traffic buffer.

Quick freeze and thaw 5 times using methanol/dry ice and 37°C water.

Hydrate liposome overnight at RT.

Extrude the liposome using 400 nm filter membrane in a mini-extruder (see Note 8).

Mix 20 μg of liposome with 1 μM COPI-related factors (ARF1, ARFGAP1, BARS, and/or COPI) in 100 μl of reaction buffer 2 (see Note 9).

Incubate the mixture at RT for 30 min.

Fix the sample using 4% PFA/water at RT for 10 min.

Take 20 μl of the mixture and load on the EM grid for 10 min.

Rinse the grid three times using 100 μl of ddw.

Stain the liposome using 2.5% uranyl staining solution for 1 min.

Examine the liposomes for tubulation and vesiculation using transmission EM (see Note 10).

Table 1.

Composition of lipids to prepare liposomes

| Liposome (w/w) | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Golgi composition | DOPC:DOPE:DOPS:DOPI:Cholesterol:SM:PA:DAG = 50:10:7:6:17:8:1:1 |

| Simplified liposome (w/w) | |

|

| |

| Saturated PA liposome | 2C18:0 PA:DOPC = 30:70 |

| Monounsaturated PA liposome | DOPA:DOPC = 30:70 |

| Polyunsaturated PA liposome | C18:0–22:6 PA:DOPC = 30:70 |

| Short PA liposome | 2C10:0 PA:DOPC = 30:70 |

| Saturated DAG liposome | 2C16:0 DAG:DOPC = 30:70 |

| Monounsaturated DAG liposome | DODAG:DOPC = 30:70 |

| Polyunsaturated DAG liposome | C18:0–22:6 DAG:DOPC = 30:70 |

| Short DAG liposome | 2C10:0 DAG:DOPC = 30:70 |

Polyunsaturated PA was synthesized in the group led by Dr. Minnaard.

Cell-based COPI transport assay

On day 1, seed 1×105 of cells on 6 well culture plate containing 5 cover glasses in each well.

On day 2, transfect siRNA against LPAAT-γ, PLD2, or LPP3 using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (Invitrogen).

On day 3, transfect VSVG(ts045)-KDELR using Genjet (Signagen Laboratories) for 24 hr.

Prepare 400 nm liposome (50:50 = DOPC:lipid with various forms, w/w) in a glass tube to achieve the final concentration of 125 μM as described in section 3.3.

Dry the lipid mixture using nitrogen gas.

Resuspend the lipids using 2 ml culture media containing 25 μM BSA.

Sonicate the mixture for 5 min.

Filter the mixture using 0.45 μm filter (Sartorius).

Warm culture media containing liposome at 32°C for 2 hr.

Aspirate off culture media of cells from step 3.

Fill up with 2 ml 32°C pre-warmed DMEM containing liposome/BSA as prepared in step 9.

Incubate cells in 32°C incubator for 3 hr.

After 3 hr incubation at 32°C, take a cover slip for 0 min time point.

Change the culture media with 40°C pre-warmed DMEM containing liposome/BSA.

Incubate cells in 40°C incubator.

Take a cover slip every 20 min for time course experiment.

Fix cells on a cover slip using 4% PFA/PBS at RT for 10 min.

Rinse cells twice using cold PBS.

Incubate cells in blocking buffer, overnight at 4°C.

Stain cells using antibody diluted with antibody incubation buffer (1:3 dilution for VSVG, and 1:500 dilution for Giantin).

Examine the colocalization of VSVG(ts045)-KDELR with Giantin using confocal microscopy, followed quantitation using Metamorph 7.7.

4. NOTES

Check the percent of homogenized cells using Trypan Blue staining. 10% cells are usually homogenized by 8 passes.

Check sucrose concentration of 37% using a refractometer.

The protein concentration is usually around 0.5 mg/ml.

Do not vortex or resuspend Golgi membrane to avoid disruption.

Cushion provides a better separation of the supernatant and pellet fractions after centrifugation, as the two fractions can be collected with less cross contamination.

Lipid mixture is dried by gently blowing N2 gas over the upper surface of the solution.

Extrusion involves 10 passes through 400 nm filter membrane in a mini extruder.

Increasing the percentage of short lipid and/or DAG prevents the liposome formation. Liposome morphology can be examined using TEM.

Protein concentration should not exceed 2 μM to avoid non-specific effects.

Vesicles with diameter of around 50 nm are considered as vesicles reconstituted from liposome having diameter of 400 nm.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work is funded by grants to SYP (National Research Foundation of Korea, NRF-2020R1C1C1008823, NRF-2017R1A5A1015366, and Korea Health Industry Development Institute, KHIDI-HR20C0025), and to VWH (National Institutes of Health, R37GM058615).

References

- [1].McMahon HT, Gallop JL, Membrane curvature and mechanisms of dynamic cell membrane remodelling, Nature 438(7068) (2005) 590–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Graham TR, Kozlov MM, Interplay of proteins and lipids in generating membrane curvature, Curr Opin Cell Biol 22(4) (2010) 430–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Janmey PA, Kinnunen PK, Biophysical properties of lipids and dynamic membranes, Trends Cell Biol 16(10) (2006) 538–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Yang JS, Lee SY, Gao M, Bourgoin S, Randazzo PA, Premont RT, Hsu VW, ARFGAP1 promotes the formation of COPI vesicles, suggesting function as a component of the coat, J Cell Biol 159(1) (2002) 69–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Yang JS, Lee SY, Spanò S, Gad H, Zhang L, Nie Z, Bonazzi M, Corda D, Luini A, Hsu VW, A role for BARS at the fission step of COPI vesicle formation from Golgi membrane, EMBO J 24 (2005) 4133–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Yang JS, Gad H, Lee SY, Mironov A, Zhang L, Beznoussenko GV, Valente C, Turacchio G, Bonsra AN, Du G, Baldanzi G, Graziani A, Bourgoin S, Frohman MA, Luini A, Hsu VW, A role for phosphatidic acid in COPI vesicle fission yields insights into Golgi maintenance, Nat Cell Biol 10(10) (2008) 1146–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Yang JS, Valente C, Polishchuk RS, Turacchio G, Layre E, Moody DB, Leslie CC, Gelb MH, Brown WJ, Corda D, Luini A, Hsu VW, COPI acts in both vesicular and tubular transport, Nat Cell Biol 13(8) (2011) 996–1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Park SY, Yang JS, Schmider AB, Soberman RJ, Hsu VW, Coordinated regulation of bidirectional COPI transport at the Golgi by CDC42, Nature 521(7553) (2015) 529–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Park SY, Yang JS, Li Z, Deng P, Zhu X, Young D, Ericsson M, Andringa RLH, Minnaard AJ, Zhu C, Sun F, Moody DB, Morris AJ, Fan J, Hsu VW, The late stage of COPI vesicle fission requires short forms of phosphatidic acid and diacylglcerol., Nature communications Jul 30; 10(1) (2019) 3409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Cole NB, Ellenberg J, Song J, DiEuliis D, Lippincott-Schwartz J, Retrograde transport of Golgi-localized proteins to the ER, J Cell Biol 140 (1998) 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]