Abstract

G-Quadruplexes (G4s) are appealing targets for anticancer therapy because of their location in the genome and their role in regulating physiological and pathological processes. In this article, we report the characterization of the molecular interaction and selectivity of OAF89, a 9,10-disubstituted G4-binding anthracene derivative, with different DNA sequences. Advanced analytical methods, including mass spectrometry and nuclear magnetic resonance, were used to conduct the investigation, together with the use of in silico docking and molecular dynamics. Eventually, the compound was tested in vitro to assess its bioactivity against lung cancer cell lines.

Keywords: G-Quadruplex, NMR, ESI-MS, Molecular docking, Lung cancer

Lung cancer (LC) remains a leading cause of mortality worldwide, and new therapeutic strategies are urgently needed. Although precision medicine has made great strides, identifying resolutive targets remains an open challenge. Medicinal chemistry has long had the goal of searching for antitumor drugs capable of selectively hitting different types of structures, like alternative conformations of DNA.1

G-Quadruplexes (G4s) are four-stranded nucleic acid secondary structures formed by G-rich sequences. They are given by stacking of two or more square planar arrangements of guanines, also named tetrads, held together by Hoogsten hydrogen bonds and stabilized by central cations (mostly K+ or Na+).2 G4s can be intramolecular or intermolecular and can adopt distinct topologies including parallel, antiparallel, and hybrid, which, together with other features like composition of loops, sequence, and length allow a target-selective ligands research.3 Since G4s are involved in hallmarks of cancer like apoptosis resistance, replicative immortality, and angiogenesis, they have been addressed as attractive targets for cancer therapy.4 For this reason, progress in medicinal chemistry has shed light on the intriguing properties and potentials of G4-targeting compounds that could induce nucleic acid damage and alter gene expression in cancer cells.5

Most of these well-known G4 ligands share an aromatic core which allows π–π stacking interactions with tetrads, one or more positive moieties for the interaction with phosphate backbone in grooves and loops, and a steric bulk to prevent intercalation with double strand DNA (dsDNA).6 To date, more than 800 G4 ligands have been identified as possible interactors for G4s, but only few of them reached clinical trials.7−9 In fact, candidates should ideally be able to cross nuclear membranes and avoid off-target toxicity given mainly by intercalation with dsDNA.10 According to these criteria, molecules with these features are prevalently those belonging to classes of heteroaromatic compounds such as acridines, fluoroquinolones, and some natural derivatives like berberines, flavonoids, and anthraquinones. Quarfloxin and pidnarulex are known experimental G4-ligands that form a complex with G4s able to affect replication events in cancer cells.6,11−14 As anticipated, one of the suitable classes for G4s-targeting approach is anthracenes and their derivatives, since these compounds possess the correct geometry to stack in and between tetrads through their hydrophobic core, while the substituents provide the interaction with grooves.15,16

In this letter, we report the investigation of the small molecule of OAF89 with the aim of characterizing in more detail its interaction with G4s and dsDNA. Two telomeric sequences were used to unravel the G4-binding properties of OAF89 in more detail, namely, Tel23 and wtTel26. Both sequences, which fold into hybrid-2 topology, are characterized by the presence of the TTAGGG telomeric base repeat and are accepted as telomeric models, but wtTel26 possesses three additional bases. In addition, for both sequences, experimental 3D structures have been deposited, thus enabling computational studies. The study was carried out by using electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS), NMR experiments, and in silico techniques. Further, in vitro experiments were also performed to evaluate the effects on LC cells given the involvement of G4s in this disease.17,18

First, ESI-MS was used to study the binding of the compound with nucleic acid sequences, and the interaction efficiency was expressed in terms of binding affinity (BA) by measuring signal intensities of species in the gas phase in the mass spectra.19 Additionally, collision-induced dissociation (CID) experiments were used to investigate the stability of small molecule-DNA complexes (ECOM50%).20 This parameter is biologically relevant since G4 stabilization is one of the goals of ligands targeting such arrangements to influence downstream biological processes. In a previous study, we showed that the molecule interacts with Tel23 preferentially when compared to dsDNA (BA = 80.3 and 41.8, respectively). Accordingly, higher ECOM50% values were calculated for Tel23 (43.58 and 34.39 eV for 2:1 and 1:1 complexes, respectively) than for dsDNA (33.42 eV).21 Our new experiments carried out using wtTel26 in the ESI-MS screening under the same conditions showed that the compound binds this G4 structure with a BA of 48.1 (Figure S1), sensitively lower than that measured for Tel23. Despite both sequences being reported to fold in the hybrid-2 topology,22,23 it must be considered that the two 3D arrangements are structurally different, and lack of accessibility to the tetrad in wtTel26 could justify this behavior. Accordingly, an ECOM50% value of 31.62 eV, even lower of that previously calculated for dsDNA, was measured for the complex formed by the ligand with wtTel26 (Figures S2–S3). Thus, ESI-MS highlighted Tel23 as the preferential target for the oxidation of OAF89.

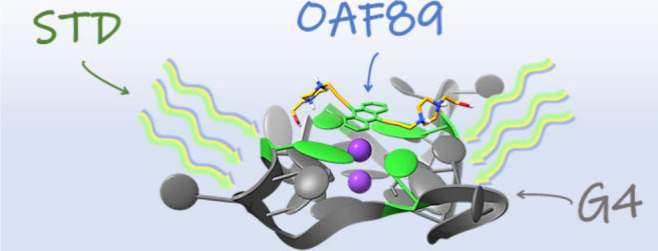

Then, Saturation Transfer Difference (STD) experiments were performed in order to better define the interaction pattern of OAF89 with Tel23, wtTel26, and dsDNA from a structural point of view. Nuclear Overhauser effect (NOE)-based experiments are one of the most attractive NMR techniques when it comes to performing ligand libraries screening against targets of interest and to characterize ligand-target interactions from a structural point of view. In this context, STD experiments have found recently successful application in the study of nucleic acids.24−26 In these experiments, macromolecules become saturated through the selective irradiation of a narrow spectral region of their signals. As a result, ligands that can interact significantly with the target of interest will be saturated as well due to the NOE effect; in contrast, ligands that do not interact will not be magnetized. Indeed, STD experiments can be used to figure out which portions of ligands come closest to the surface of the macromolecule, thus providing epitope mapping of the ligand itself and structural information about the key features of the pharmacophore.

In our study, DNA sequences were irradiated in imino (δ = 11.0 ppm), aromatic (δ = 9.5 ppm), and deoxyribose/backbone (δ = 5.8 ppm) regions with the aim of highlighting which moieties were more important in the ligand-target complex formation and stabilization (Figures S4–S6). In the case of the binding study with Tel23, relevant STD effects were observed only for the protons of the polycyclic aromatic core of OAF89, suggesting a possible interaction via π–π stacking with nucleobases. The involvement of the aromatic region was also confirmed with T1ρ NMR, an experiment that distinguishes bound and unbound ligands thanks to differences in relaxation time (Figure S7A).27,28 As a further confirmation, a water-Ligand Observed via gradient spectroscopy (wLOGSY) study was also performed. This experiment, which is based on the transfer of magnetization from the water to the macromolecule and then to the ligand,29 confirmed that OAF89 interacts with Tel23 (Figure S7B). The results of such studies are depicted in Figure 1, while full results of STD experiments are reported in the Supporting Information section and show that OAF89 also interacts with the other tested sequences. More in detail, a negligible STD effect was observed for Tel26, while STD signals were observed for the complex with dsDNA under the same experimental conditions (Figures S5–S6). Control experiments were carried out to support the observations: fructose was used as nonbinder in an STD experiment with Tel23 under the same conditions, and no interaction was observed, while the STD effect was also measured in a sample lacking the nucleic acid for reference (Figures S8–S9).

Figure 1.

Graphical representation resuming the results of the NMR experiments for OAF89 with Tel23.

Following the previously reported results, the binding mode of OAF89 to Tel23 was also studied using in silico techniques since the compound showed a preference for this sequence in both ESI-MS and NMR experiments. In particular, a 3D model of human telomeric DNA folded into a G4 arrangement was selected from the Protein Data Bank (PDB ID 7PNL). Importantly, this structure is based on the same sequence that was used for ESI-MS and NMR studies (Tel23). Molecular docking showed that OAF89 interacted by stacking with the upper tetrad composed by residues G4, 10, 16, 22 (−8.3 kcal/mol). The complex is characterized by three hydrogen bonds established by N+H belonging to OAF89 that interacted with T11 (2.06 and 2.72 Å, respectively) and with G22 (2.13 Å). Further, two π–π interactions occurred between G4 and with the anthracene scaffold (respectively, 4.22 and 3.53 Å), and another π–π interaction between anthracene scaffold and the pyrimidine component in G22 (4.00 Å) was detected (Figure 2A; in Figure S10, a comparison of the pose with the cognate ligand is reported). Moreover, to evaluate whether the interactions were stable, a molecular dynamics (MD) simulation was performed in a time span of 250 ns, and a structural stability of the complex was observed. Root-Mean-Square Deviation (RMSD) trajectory confirmed that OAF89 was able to maintain Tel23 stable during simulation time (Figure 2B, Figure S11).

Figure 2.

Predicted interaction motif for OAF89 (orange) with Tel23 (A) and trajectories retrieved from MD simulation showing the RMSD of the OAF89/Tel23 complex over the simulation time (B). The plot for the heavy atoms of the ligand is depicted in orange (aligned with Tel23), while the plot for tetrads in Tel23 is depicted in green (upper panel). The trajectories for anthracene scaffold of OAF89 and for the interacting tetrad are depicted in orange and green, respectively, in the bottom panel (B).

Additionally, the prediction of physicochemical descriptors relevant for ADME properties of OAF89 was carried out. The molecule can be defined as “drug-like” in terms of size, polarity, lipophilicity, and degree of insaturation, except for one violation to Lipinski’s rule since ideal molecular weight should be <500 g/mol (MWOAF89 = 510.64 g/mol).30 Nevertheless, according to computed physicochemical descriptors, absorption through the gastrointestinal tract is presumed to be high, while the compound was not predicted to cross the blood-brain barrier by passive diffusion.

The results obtained from computational and experimental interaction studies prompted us to evaluate the activity of the compound in vitro. Given the interest recently dedicated to the involvement of G4s as targets for innovative therapeutic strategies in LC,17,18 the compound was tested against a panel of lung cancer cell lines consisting of adenocarcinoma human alveolar basal epithelial cells (A549), nonsmall cell lung carcinoma cells (PC-9), bronchioalveolar carcinoma epithelial-like cells (H358), large cell lung cancer cells (H460), nonsmoker nonsmall cell lung cancer cells (H1975), and smokers with stage 3B bronchoalveolar carcinoma cells (H1650). Normal human bronchial epithelium cells (BEAS-2B) were also included in the study as a control. The MTT assay demonstrated that the compound reduces viability of cancer cells in the tested cell lines in the low micromolar range, except for the case of H1650 for which an IC50 value >10 μM was detected. Nevertheless, the molecule lacks selectivity, as it was observed to be toxic in the same concentration range in BEAS-2B cells (Figure S12).

The in vitro data are indeed partially in line with the information obtained from mechanistic binding studies, as the compound was shown not to interact exclusively with G4 in the ESI-MS and NMR studies. Thus, at this stage, the candidate is not ideal from the point of view of sequence selectivity or of biological activity, suggesting that the preference observed for Tel23 is not sufficient for avoiding toxicity. Nevertheless, interestingly, experimental data showed that the compound shows the lowest affinity toward wtTel26, likely due to the hindrance of the tetrads in this arrangement. Most importantly, thanks to NMR experiments, we were able to define which parts of the molecule are involved more than others in the interaction with the nucleic acid structures. In particular, the findings regarding the interaction of OAF89 and Tel23 are supported and confirmed by the molecular dynamics experiment in which the anthracene scaffold was highlighted as pivotal in the stabilization of the complex.

Experimental observation combined with evidence from computational data could guide the synthesis of novel derivatives and pave the way for the development of sequence- or topology-selective molecules based on the anthracene scaffold with improved G4 over dsDNA recognition and lower toxicity.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Dr. Alberto Ongaro (University of Padova).

Glossary

Abbreviations

- BA:

binding affinity

- CID:

collision-induced dissociation

- dsDNA:

double strand DNA

- ESI-MS:

electrospray ionization mass spectrometry

- G4:

G-Quadruplex

- LC:

lung cancer

- NOE:

Nuclear Overhauser effect

- NMR:

nuclear magnetic resonance

- PDB:

Protein Data Bank

- RMSD:

Root-Mean-Square Deviation

- STD:

Saturation Transfer Difference

- wLOGSY:

water-Ligand Observed via Gradient SpectroscopY

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsmedchemlett.4c00340.

ESI-MS experimental procedure; Figure S1: ESI-MS interaction study: mass spectrum of the wtTel26/ligand binding experiment; Figure S2. CID fragmentation spectrum of the G-quadruplex/ligand complex; Figure S3. G-quadruplex/ligand CID complex dissociation studies; NMR experimental procedure; Figure S4: STD experiments of OAF89 with Tel23; Figure S5: STD experiments of OAF89 with wtTel26; Figure S6: STD experiments of OAF89 with dsDNA; Figure S7: T1ρ Other NMR studies; Figure S8: Analysis of the STD experiments of fructose with Tel23; Figure S9: Comparison of STD effect in presence and in absence of the nucleic acid; Computational studies experimental procedure; Figure S10: Pose of berberine derivative and comparison with OAF89; Figure S11: OAF89 2D structure and RMSF; In vitro experimental procedure; Figure S12: MTT cell viability assay (PDF)

Author Contributions

⊥ (M.A. and M.G.) These authors contributed equally. The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

This project was funded by Università di Brescia and Regione Lombardia.

Safety Statement. Throughout the experiments, no unexpected or unusually high safety hazards were encountered.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- De Magis A.; Manzo S. G.; Russo M.; et al. DNA damage and genome instability by G-quadruplex ligands are mediated by R loops in human cancer cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2019, 116 (3), 816–825. 10.1073/pnas.1810409116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson J. R.; Raghuraman M. K.; Cech T. R. Monovalent cation-induced structure of telomeric DNA: The G-quartet model. Cell. 1989, 59 (5), 871–880. 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90610-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guédin A.; Gros J.; Alberti P.; Mergny J. L. How long is too long? Effects of loop size on G-quadruplex stability. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010, 38 (21), 7858–7868. 10.1093/nar/gkq639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanahan D.; Weinberg R. A. Hallmarks of Cancer: The Next Generation. Cell. 2011, 144 (5), 646–674. 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakanishi C.; Seimiya H. G-quadruplex in cancer biology and drug discovery. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2020, 531 (1), 45–50. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2020.03.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Z. Y.; Wang X. N.; Cheng S. Q.; Su X. X.; Ou T. M. Developing Novel G-Quadruplex Ligands: From Interaction with Nucleic Acids to Interfering with Nucleic Acid–Protein Interaction. Molecules. 2019, 24 (3), 396. 10.3390/molecules24030396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q.; Xiang J. F.; Yang Q. F.; Sun H. X.; Guan A. J.; Tang Y. L. G4LDB: a database for discovering and studying G-quadruplex ligands. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41 (D1), D1115–D1123. 10.1093/nar/gks1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazemi M. E.; Onizuka K.; Kobayashi T.; Usami A.; Sato N.; Nagatsugi F. Vinyldiaminotriazine-acridine conjugate as G-quadruplex alkylating agent. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2018, 26 (12), 3551–3558. 10.1016/j.bmc.2018.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun D.; Thompson B.; Cathers B. E.; et al. Inhibition of Human Telomerase by a G-Quadruplex-Interactive Compound. J. Med. Chem. 1997, 40 (14), 2113–2116. 10.1021/jm970199z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueiredo J.; Mergny J. L.; Cruz C. G-quadruplex ligands in cancer therapy: Progress, challenges, and clinical perspectives. Life Sciences. 2024, 340, 122481 10.1016/j.lfs.2024.122481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tripathi S.; Barthwal R. NMR based structure reveals groove binding of mitoxantrone to two sites of [d-(TTAGGGT)]4 having human telomeric DNA sequence leading to thermal stabilization of G-quadruplex. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2018, 111, 326–341. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.12.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drygin D.; Siddiqui-Jain A.; O’Brien S.; et al. Anticancer Activity of CX-3543: A Direct Inhibitor of rRNA Biogenesis. Cancer Res. 2009, 69 (19), 7653–7661. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilton J.; Gelmon K.; Bedard P. L.; et al. Results of the phase I CCTG IND.231 trial of CX-5461 in patients with advanced solid tumors enriched for DNA-repair deficiencies. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13 (1), 3607. 10.1038/s41467-022-31199-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu H.; Hurley L. H. A first-in-class clinical G-quadruplex-targeting drug. The bench-to-bedside translation of the fluoroquinolone QQ58 to CX-5461 (Pidnarulex). Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2022, 77, 129016 10.1016/j.bmcl.2022.129016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha P.; Kumar Y. P.; Das T.; et al. G-Quadruplex-Specific Cell-Permeable Guanosine–Anthracene Conjugate Inhibits Telomere Elongation and Induces Apoptosis by Repressing the c-MYC Gene.. Bioconjugate Chem. 2019, 30 (12), 3038–3045. 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.9b00655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhuri R.; Bhattacharya S.; Dash J.; Bhattacharya S. Recent Update on Targeting c-MYC G-Quadruplexes by Small Molecules for Anticancer Therapeutics. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 64 (1), 42–70. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c01145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Martin V.; Lopez-Pujante C.; Soriano-Rodriguez M.; Garcia-Salcedo J. A. An Updated Focus on Quadruplex Structures as Potential Therapeutic Targets in Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21 (23), 8900. 10.3390/ijms21238900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueiredo J.; Djavaheri-Mergny M.; Ferret L.; Mergny J. L.; Cruz C. Harnessing G-quadruplex ligands for lung cancer treatment: A comprehensive overview. Drug Discov Today. 2023, 28 (12), 103808 10.1016/j.drudis.2023.103808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribaudo G.; Ongaro A.; Oselladore E.; Memo M.; Gianoncelli A. Combining Electrospray Mass Spectrometry (ESI-MS) and Computational Techniques in the Assessment of G-Quadruplex Ligands: A Hybrid Approach to Optimize Hit Discovery. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 64 (18), 13174–13190. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.1c00962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu N.; Yang H.; Cui M.; Song F.; Liu Z.; Liu S. Evaluation of alkaloids binding to the parallel quadruplex structure [d(TGGGGT)]4 by electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. Journal of Mass Spectrometry. 2012, 47 (6), 694–700. 10.1002/jms.2997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribaudo G.; Ongaro A.; Oselladore E.; Zagotto G.; Memo M.; Gianoncelli A. 9,10-Bis[(4-(2-hydroxyethyl)piperazine-1-yl)prop-2-yne-1-yl]anthracene: Synthesis and G-quadruplex Selectivity. Molbank. 2020, 2020 (2), M1138. 10.3390/M1138. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ongaro A.; Desiderati G.; Oselladore E.; et al. Amino-Acid-Anthraquinone Click Chemistry Conjugates Selectively Target Human Telomeric G-Quadruplexes. ChemMedChem. 2022, 17 (5), e202100665 10.1002/cmdc.202100665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai J.; Carver M.; Punchihewa C.; Jones R. A.; Yang D. Structure of the Hybrid-2 type intramolecular human telomeric G-quadruplex in K+ solution: insights into structure polymorphism of the human telomeric sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35 (15), 4927–4940. 10.1093/nar/gkm522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer M.; Meyer B. Characterization of Ligand Binding by Saturation Transfer Difference NMR Spectroscopy. Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 1999, 38 (12), 1784–1788. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Micco S.; Bassarello C.; Bifulco G.; Riccio R.; Gomez-Paloma L. Differential-Frequency Saturation Transfer Difference NMR Spectroscopy Allows the Detection of Different Ligand–DNA Binding Modes. Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 2006, 45 (2), 224–228. 10.1002/anie.200501344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martino L.; Virno A.; Pagano B.; et al. Structural and Thermodynamic Studies of the Interaction of Distamycin A with the Parallel Quadruplex Structure [d(TGGGGT)]4. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129 (51), 16048–16056. 10.1021/ja075710k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maity S.; Gundampati R. K.; Suresh Kumar T. K. NMR Methods to Characterize Protein-Ligand Interactions. Natural Product Communications. 2019, 14 (5), 1934578 × 1984929 10.1177/1934578X19849296. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese D. R., Connelly C. M., Schneekloth J. S.. Ligand-observed NMR techniques to probe RNA-small molecule interactions. In: Methods in Enzymology. Vol 623. Elsevier; 2019:131–149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raingeval C.; Cala O.; Brion B.; Le Borgne M.; Hubbard R. E.; Krimm I. 1D NMR WaterLOGSY as an efficient method for fragment-based lead discovery. Journal of Enzyme Inhibition and Medicinal Chemistry. 2019, 34 (1), 1218–1225. 10.1080/14756366.2019.1636235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daina A.; Michielin O.; Zoete V. SwissADME: a free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7 (1), 42717. 10.1038/srep42717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.